Abstract

This cross-sectional study evaluated the perception of individuals with prediabetes/diabetes about their living conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic to identify the facilitators, barriers, and reasons to remain physically active at home and adhere to recommended exercise. It included individuals with prediabetes/diabetes who had completed an exercise intervention, which started on-site and moved to a remote home-based regime due to the COVID-19 pandemic and were advised to keep exercising at home. The outcomes were assessed by a bespoke questionnaire that was developed by the research team, the Brazilian Portuguese adapted version of the Exercise Adherence Rating scale, and the Motives for Physical Activity Measure-Revised scale. Of 15 participants (8 female, 58 ± 11 years), most reported positive perceptions about their living conditions and few difficulties maintaining some physical activity at home. However, only 53.8% of them adhered to the recommended exercise. Time flexibility, no need for commuting, and a sense of autonomy were the main facilitators of home exercise, while a lack of adequate space was the main barrier. The descending order of median scores that were obtained in each reason for physical activity was fitness, enjoyment, competence, social, and appearance. Individuals with prediabetes/diabetes maintained some physical activity during the pandemic, mainly motivated by health concerns.

1. Introduction

As a chronic disease that requires continuous care for glycemic control and the prevention of its complications, diabetes care demands different approaches [1], including routine physical activity [2]. Physical exercise contributes to glycemic control, weight loss, positive self-perception of health status, improved cardiorespiratory fitness, well-being, and quality of life in individuals living with diabetes [2,3,4]. Additionally, physical activity promotes Type 2 diabetes prevention in individuals with prediabetes [3,5]. Supervised and structured exercise programs promote these benefits more efficiently than non-supervised ones [6]. However, studies have shown a progressive decrease in exercise adherence after the completion of these programs [3,7]. This reduction in exercise adherence is possibly caused by barriers such as a lack of understanding of exercise instructions that are provided by health professionals; difficulty fitting exercise into a daily routine; hypoglycemia concern during exercise, especially in people with Type 1 diabetes [8,9]; and a lack of pleasure and motivation to exercise [7].

The COVID-19 pandemic [8] imposed significant social changes that affected people’s lifestyles and behaviors [9,10]. During the lockdown, people with Type 2 diabetes increased sitting time and decreased minutes of walking or other moderate physical activity per week [11]. At the same time, healthcare systems (e.g., NHS) [12], medical societies [13], and researchers [14] recommended home-based exercises to maintain population physical activity levels and to address the physical and mental health problems that were caused or worsened by the pandemic [15,16].

Indeed, there is evidence that home-based exercises can improve muscle strength, functional capacity, and quality of life in patients with autoimmune [17] and chronic diseases [18]. A recent systematic review demonstrated that home-based exercises are a safe and effective alternative to health management for people living with diabetes and prediabetes [19]. However, adherence to home-based exercise is usually low [20], evidencing that exercise maintenance is complex, as it does not depend only on guidance and encouragement from healthcare professionals.

This study aims to assess individuals with prediabetes and diabetes that had to move from a structured and on-site to a remote home-exercise intervention because of the COVID-19 pandemic to (a) evaluate their perception of their living conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic; (b) identify facilitators, barriers, and motives to remain physically active at home during the pandemic; and (c) investigate their adherence to exercise as recommended when completed the exercise intervention.

2. Materials and Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital of Federal University of Juiz de Fora (CAAE: 36267420.3.0000.5133) and involved a convenience sample of participants who completed the exercise intervention of the pilot study of Diabetes College Brazil trial (NCT03914924). In that pilot study, individuals with prediabetes and diabetes participated in a 12-week exercise intervention lasting. The inclusion criteria were as follows: age ≥ 18 years, clinical diagnosis of prediabetes (fasting glucose ≥ 100 and <126 mg/dL or glycated hemoglobin ≥ 5.7 e < 6.5%) [21] or diabetes (fasting glucose >126 mg/dL or glycated hemoglobin > 6.5%) [21]; no cognitive limitation (i.e., six-item screener score ≥ 4) [22]; no confirmed diagnosis of unstable coronary artery disease or heart failure; no pacemaker and/or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; no intermittent claudication; no recent cardiovascular event or cardiac surgery (≤6 months); and not enrolled currently in a structured physical exercise program that follows diabetes guidelines. The exclusion criteria were: clinical decompensation that contraindicated physical exercising, physical and/or mental limitations that prevented the participant from physical exercise and/or understanding educational content, and complex ventricular arrhythmias. Due to the social restrictions that were imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, it was impossible to carry out all the supervised on-site exercise sessions as planned. Therefore, the intervention was adapted to be delivered remotely through weekly phone calls and a video with home-based exercises recorded by the research team [23]. All the individuals who completed participation in the pilot study were instructed to maintain at least 150 min of moderate- or vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity and 2 to 3 sessions/week of resistance exercise, as recommended by the diabetes guidelines [1,21,24], and were invited to participate in the present study.

The data collection started in August 2020, three months after completing the exercise intervention. The individuals were contacted over a maximum of three phone call attempts to receive the invitation to participate in the present study. The study details were presented, and the individuals who agreed to participate received, via WhatsApp®, a Google® form containing the study consent form and the three questionnaires that are described below. All the participants signed the online consent form before being included in the study. Their sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were obtained from previously collected data in the Diabetes College Brazil trial pilot baseline (submitted data).

The perceptions about living conditions during the pandemic and the facilitators and barriers to maintaining physical activity at home were assessed by a bespoke 8-item questionnaire that was developed exclusively for this purpose by the research team (Appendix A). Perceptions regarding living conditions during the pandemic were evaluated based on the responses to items 1 to 5 of this questionnaire, and facilitators and barriers to exercising at home were assessed based on items 6 to 8 responses.

The motives for remaining physically active were evaluated by the Motives for Physical Activity Measure-Revised scale (MPAM-R) [25,26]. This scale is a self-administered questionnaire that contains twenty-six items that encompass five general motives: enjoyment (seven items), competence (four items), appearance (six items), fitness (four items), and social (five items). Each item should be responded to on a 7-point Likert scale (1—“not at all true for me” to 7—“very true for me”). This questionnaire is based on the Self-Determination Theory [27], which has been used to understand the motivation for physical activity in different populations [28]. Among the motives for physical activity that were assessed by the MPAM-R scale, enjoyment and competence are related to intrinsic motivation, and the others refer to extrinsic motivation.

Exercise adherence, as recommended, was evaluated by the Brazilian Portuguese version of the Exercise Adherence Rating scale (EARS-Br) [29,30]. This scale is a self-administered questionnaire that contains six items that are scored by an ordinal answer range (0 = strongly agree to 4 = totally disagree) ranging from 0 to 24, and a score of seventeen points is a cut-off point that demarks adequate adherence to the recommended exercise [30].

Categorical data were analyzed by calculating simple frequencies and percentiles. The normal distribution of numerical data was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test, adopting a significance level of 5%. Variables with normal distribution were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, while those with non-normal distribution were expressed as the median and interquartile range. IBM SPSS Statistics, v. 26, software was used for data analysis.

3. Results

A total of 33 individuals were eligible to participate in the study, of which 16 answered the research team phone call, and 15 agreed to participate. All the participants completed the three questionnaires online. The clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant’s sociodemographic and clinical characteristics.

Most participants reported dealing well with the fact that COVID-19 disease is highly prevalent in individuals with diabetes and that it is associated with increased incidence of disease severity and mortality. Regarding other aspects of living conditions during the pandemic, the higher response rate was in options that express positive perceptions, as described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Response rate to each answer option of questions that were related to the living condition perceptions during the pandemic.

A total of 13 participants (87%) reported having managed to maintain physical activity during the pandemic (item 6 of Appendix A). The affirmatives presenting exercise barriers (item 7 of Appendix A) had an agreement response rate lower than 50%. The lack of adequate space was the most significant barrier (40%) to maintaining physical activity at home. The affirmatives presenting exercise facilitators (item 7 of Appendix A) had an agreement response rate that was higher than 50%, and the flexibility of time, no need for commuting, and the sense of autonomy were pointed out as the main facilitators, as described in Table 3. Most participants (73%, n = 11) reported that they would choose supervised on-site exercise sessions if they had this possibility (item 8 of Appendix A).

Table 3.

Barriers and facilitators that were perceived by the participants to maintain exercising at home (n = 15).

3.1. Motives for Physical Activity Maintenance

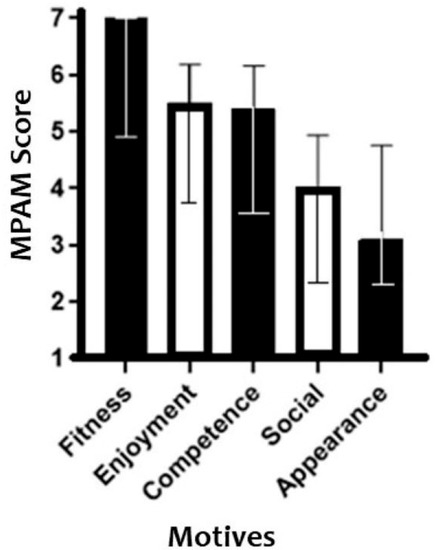

Among the five motives for physical activity that were evaluated by the MPAM-R, fitness achieved the highest score while appearance had the lowest, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Scores to each MPAM-R item. Values are expressed as the median and interquartile ranges.

3.2. Exercise Adherence

The median (interquartile range) of the EARS-Br total score was 17 (13–23), consequently revealing that 53.3% (n = 8) of the participants adhered, and 46.7% (n = 7) did not comply with the exercise according to recommendations that were received. Table 4 describes the response rate that was obtained for each EARS-Br scale response option.

Table 4.

Percentages of participants’ responses to each of the response options in the EARS-Br. (n = 15).

4. Discussion

This study observed that the individuals with prediabetes and diabetes moving from an on-site supervised to a remote home-based exercise intervention because of the COVID-19 pandemic maintained some physical activity at home three months after this intervention, motivated by health concerns. Additionally, most participants had positive perceptions about their living conditions during the pandemic. Over half of them adhered to aerobic physical activity and resistance exercise as recommended at the end of the exercise intervention.

Most participants reported positive perceptions about their living conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sociodemographic characteristics, such as household income and an educational level that was higher than observed in most of the Brazilian population (average household income: 2 minimum wages received monthly; educational level: 41% highschool concluded or higher) [31], may have positively influenced the participants’ perception of their living conditions in the present study. In addition, most participants were married, did not live alone, and were employed or retired, which possibly provided social, emotional, and financial support during the pandemic. The period in which the data were collected may also help to explain the positive perceptions since there were reduced social restrictions that were imposed by the pandemic in the city where the study was conducted at the data collection time [32]. In fact, a previous study [33] revealed that lifting the social restrictions that were imposed by the pandemic contributed to improving the quality of life of individuals with diabetes. Another possible explanation for the positive perceptions during the pandemic was maintaining some level of physical activity, which has been associated with positive psychological well-being [34]. Indeed, most participants reported physical activity maintenance during the pandemic. The main facilitators of home-based exercise were time flexibility, no need for commuting, and a sense of autonomy.

The results from exercise adherence revealed that only 53.3% of the participants fully complied with the exercise as recommended after an exercise intervention. The lack of exercise adherence that was scored by 46.7% of the participants may have been influenced by the lack of adequate space and insecurity to perform them without supervision, considering that these statements had a higher percentage of agreement than the other barriers to exercising at home. In addition, the age of the participants may have contributed to this finding since there is a decrease in willingness to exercise with aging as exercise self-efficacy is negatively correlated with age [35]. Approximately three-quarters of the study participants had Type 2 diabetes or pre-diabetes, conditions that are more prevalent in the older age group [21,36]. Even if some participants did not fully comply with exercise as recommended by the diabetes guidelines [1,21,24], it is important to recognize that they managed to maintain some level of physical activity. This finding corroborates the recent view that was portrayed by current Physical Activity Guidelines [37], which considers that “Every Move Counts” and “doing some physical activity is better than doing nothing”.

Fitness was pointed out as the primary motive for maintaining physical activity at home during the pandemic. Fitness is considered an extrinsic motivation since the individual’s behavior is stimulated by the appreciation of the results and benefits of participation in a given activity, disease prevention, and treatment or physical condition improvement [28]. This finding disagrees with studies [34,38] that were also carried out during the pandemic, which found intrinsic factors such as pleasure as the main motive for continued exercise. However, these studies were carried out with healthy adults, possibly explaining why they did not find “fitness” as their primary motive for exercising. On the other hand, another study [39] showed mental health, another extrinsic motivation, as being both a barrier and a motivator for physical exercise at the same time. During stressful periods such as the pandemic, people are primarily motivated to be physically active to manage stress levels and anxiety and improve sleep [39]. However, they may also be too anxious or depressed to start and maintain physical exercise [39]. The “social” motive is an extrinsic motivation that has been pointed out in other studies [40] as an important motivating factor to maintain physical activity as the presence of other people working at a similar activity not only creates a sense of shared identity but is also a source of healthy competition and hence motivation. The few barriers that were perceived by the participants to home-based physical activity engagement possibly contributed to the “social” motive being poorly scored in this study. On the other hand, this motive could be indirectly related to the preference of most participants for supervised and on-site exercise sessions.

This is the first study to investigate the psychosocial aspects and living conditions, facilitators, and barriers to home-based physical activity; motives for physical activity; and adherence to aerobic physical activity and resistance exercise as recommended by diabetes guidelines [1,21,24] in individuals with prediabetes and diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic. These behavioral and emotional factors interfere with blood glucose levels [40] and adhesion to exercise [41]; therefore, the understanding of factors can support health professionals to adapt the recommendations individually to achieve better exercise adherence.

The study limitations are the small number of participants and the fact that they have experienced an exercise intervention. As such, it is not possible to generalize the results to the population with prediabetes and diabetes who did not have this previous experience. In addition, the comparison with studies outside the pandemic context is limited, and, as it is a cross-sectional study, it is not possible to assume a causal relationship from its results. Despite these limitations, the study indicates perceptions that are related to the maintenance of physical exercises at home that can be considered in future research as well as in prescribing home-based exercise to this population.

5. Conclusions

Most participants in this study dealt well with their health condition during the pandemic and reported few difficulties maintaining their physical activity at home, mainly motivated by healthcare concerns. The lack of adequate space was the most significant barrier to home-based exercising. Time flexibility, no need for commuting, and a sense of autonomy were the main facilitators of physical activity maintenance.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study design. I.C.P. collected the data. I.C.P., R.R.B. and L.P.d.S. analyzed the data. I.C.P. and L.P.d.S. wrote the manuscript. M.B.S., T.P., A.L.P., P.F.T. and R.R.B. reviewed/edited the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding, and the APC was funded by the Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora (UFJF).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital of Federal University of Juiz de Fora (CAAE: 36267420.3.0000; date: 2 September 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge that this study was partly financed by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES)—Finance Code 001, the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), and the Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora (UFJF), Brazil. The authors also thank all the participants for their time, the Diabetes College Brazil research team for supporting this work, and the undergraduate student Angélica Jesus de Assis for recruiting the participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Questionnaire to assess the living condition perceptions during the pandemic and facilitators and barriers to maintaining home-based exercise

- (1)

- In general, what have been your most predominant feelings in this period of social distancing? Note: It was possible to choose more than one answer option.( ) Happy, confident, excited, energetic, active, enthusiastic( ) Calm, well, peaceful, patient, animated, hopeful( ) Depressed, worried, tired, impatient, inactive( ) Unhappy, scared, afraid, incapable, alone( ) Upset, angry, agitated, exhausted

- (2)

- Knowing that COVID-19 is highly prevalent in patients with diabetes and associated with increased incidence of disease severity and mortality, did you handle this situation well? ( ) Yes ( ) No

- (3)

- Choose the alternative that you most identify as concerning being a person with prediabetes or diabetes going through the COVID-19 pandemic:( ) I have been coping well and have continued following main preventive measures (ex.: washing hands and masking)( ) I have been coping well, but I am worried, have isolated myself as much as possible from people, and have interrupted some activities.( ) I am afraid of getting the virus. So, I isolated myself from my family and interrupted my activities, staying at home. I am feeling well this way( ) I am afraid of getting the virus. So, I isolated myself from my family and suspended my activities, staying at home. I am feeling depressed this way( ) I am petrified and apprehensive about getting the virus and worsening my health. I feel lonely, sad, and hopeless

- (4)

- In general, what is the impact of the COVID 19 pandemic on the following aspects of your life? Note: It was possible to choose more than one answer option.Psychological aspects( ) I was not affected much because my routine hadn’t changed( ) It has been a good time to review and reorganize life, and overall, I have been coping well and enjoying this time( ) In the beginning, it affected me a lot, but now I have adapted, and I can take control of my feelings( ) It has been difficult and affected my mood and my feelings a lot… I am depressed most of the time( ) It negatively affected the psychological a lot, and I don’t know how to deal with my feelings. I had crises of anxiety, depression, feelings of fear, loneliness…( ) Other: ________Family life aspectsDo you live alone? ( ) Yes ( ) No( ) I was not affected much because my family life remained as it was before( ) It has been a good time of union, good family life, and greater empathy( ) It has not been easy living together with family and having to accommodate housework and working at home at the same time( ) It has been difficult due to the children or elderly or sick family members that I have to take care of.( ) I am afraid of getting the virus from some family member or putting my family at risk, so I isolated myself from them( ) Other: _______Financial aspects( ) There was no change regarding my finances( ) My income decreased, but I am handling it well, and I am still employed( ) I lost my job, but I am handling it well( ) I lost my job, and I am not handling it well and needed financial support from others( ) It’s been challenging financially( ) Other: _______Health condition aspects( ) My health condition remained as it was before( ) My health condition improved. If you have marked this item, please, describe what improvement(s) you have noticed in your health condition: _____________( ) Some things have changed, such as I have been having problems sleeping at night, I haven’t been able to eat well and take my medication as prescribed( ) My health condition worsened; I had uncontrolled blood glucose and difficulties accessing the doctor and medicines.( ) My health condition and my blood glucose control worsened a lot, and, additionally, I had other complications imposing immediate medical care( ) Other: _______

- (5)

- Would you like to express something more about your perception of how you have felt in this period of social distancing? ____________________________________________

- (6)

- In general, have you managed to maintain the practice of physical exercise in this period of the COVID-19 pandemic? ( ) Yes ( ) No

- (7)

- Mark the option that reflects your perception of facilities and difficulties regarding the maintenance of physical exercise:

Table A1.

Affirmatives concerning the facilities and difficulties for physical exercise maintenance.

Table A1.

Affirmatives concerning the facilities and difficulties for physical exercise maintenance.

| Totally Agree | Agree | Disagree | Totally Disagree | Not Know | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| It was easier to exercise due to time flexibility, as I managed to organize my schedule better | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| It was easier because I did not have to go on-site | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I felt more autonomy and independence in exercising | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| My family was more involved with my exercise practicing, making it easier | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| It was easier because I had more exercise options besides walking | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| It was difficult to keep up with the exercises because there was a lack of adequate space | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| It was difficult to maintain exercise because I was afraid or insecure about doing them by myself | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I had problems related to my health that prevented me from performing the exercise | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I had personal problems that prevented me from performing the exercises | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| I did not keep up with the exercises due to a lack of time | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

| The video I received with exercise options to replace walking was not explanatory enough | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ | ○ |

(8)If you could choose between performing supervised on-site exercises or home-based exercises, what would you choose?

( ) Supervised on-site exercises

( ) Home-based exercises

Why is that? _____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________

You have reached the end of this questionnaire! Thank you for your participation!

References

- American Diabetes Association. 5. Facilitating behavior change and well-being to improve health outcomes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes 2022. Diabetes Care 2022, 45 (Suppl. S1), S60–S82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colberg, S.R.; Sigal, R.J.; Yardley, J.E.; Riddell, M.C.; Dunstan, D.W.; Dempsey, P.C.; Horton, E.S.; Castorino, K.; Tate, D.F. Physical Activity/Exercise and Diabetes: A Position Statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2016, 39, 2065–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Booth, J.E.; Benham, J.L.; Schinbein, L.E.; McGinley, S.K.; Rabi, D.M.; Sigal, R.J. Long-Term Physical Activity Levels After the End of a Structured Exercise Intervention in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes and Prediabetes: A Systematic Review. Can. J. Diabetes 2020, 44, 680–687.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra-Sánchez, J.; Moreno-Jiménez, M.; Nicola, C.M.; Nocua-Rodriguez, I.I.; Ameglo-Parejo, M.R.; del Carmen-Peña, M.; Cordero-Prieto, C.; Gajardo-Barrena, M.J. Evaluation of a supervised physical exercise program in sedentary patients over 65 years with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Aten. Primaria 2015, 47, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- American Diabetes Association. 3. Prevention or Delay of Type 2 Diabetes and Associated Comorbidities: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes 2022. Diabetes Care 2022, 45 (Suppl. S1), S39–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soja, A.M.; Zwisler, A.D.; Frederiksen, M.; Melchior, T.; Hommel, E.; Torp-Pedersen, C.; Madsen, M. Use of intensified comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation to improve risk factor control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus or impaired glucose tolerance—The randomized DANish StUdy of impaired glucose metabolism in the settings of cardiac rehabilitation (DANSUK) study. Am. Heart J. 2007, 153, 621–628. [Google Scholar]

- Casey, D.; De Civita, M.; Dasgupta, K. Understanding physical activity facilitators and barriers during and following a supervised exercise programme in Type 2 diabetes: A qualitative study. Diabet. Med. 2010, 27, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization. WHO Now Says COVID-19 Is Confirmed as a Pandemic. Available online: https://www.paho.org/pt/news/11-3-2020-who-characterizes-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Yen-Hao Chu, I.; Alam, P.; Larson, H.J.; Lin, L. Social consequences of mass quarantine during epidemics: A systematic review with implications for the COVID-19 response. J. Travel Med. 2020, 27, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ammar, A.; Chtourou, H.; Boukhris, O.; Trabelsi, K.; Masmoudi, L.; Brach, M.; Bouaziz, B.; Bentlage, E.; How, D.; Ahmed, M.; et al. COVID-19 Home Confinement Negatively Impacts Social Participation and Life Satisfaction: A Worldwide Multicenter Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Roso, M.B.; Knott-Torcal, C.; Matilla-Escalante, D.C.; Garcimartín, A.; Sampedro-Nuñez, M.A.; Dávalos, A.; Marazuela, M. COVID-19 Lockdown and Changes of the Dietary Pattern and Physical Activity Habits in a Cohort of Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Health Service—NHS. Physical Activity Guidelines for Adults Aged 19 to 64. Available online: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/exercise (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- American College of Sports Medicine—ACMS. Staying Active during the Coronavirus Pandemic. Available online: https://www.acsm.org/news-detail/2020/03/16/staying-physically-active-during-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Peçanha, T.; Goessler, K.F.; Roschel, H.; Gualano, B. Social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic can increase physical inactivity and the global burden of cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2020, 318, H1441–H1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghram, A.; Briki, W.; Mansoor, H.; Al-Mohannadi, A.S.; Lavie, C.J.; Chamari, K. Home-based exercise can be beneficial for counteracting sedentary behavior and physical inactivity during the COVID-19 pandemic in older adults. Postgrad. Med. 2020, 133, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwendinger, F.; Pocecco, E. Counteracting Physical Inactivity during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Evidence-Based Recommendations for Home-Based Exercise. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieczkowskaa, S.M.; Smairaa, F.I.; Mazzolania, B.C.; Gualanoa, B.; Hamilton Roschela, H.; Pecanha, T. Efficacy of home-based physical activity interventions in patients with autoimmune rheumatic diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2021, 51, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Billany, R.E.; Vadaszy, N.; Lightfoot, C.J.; Graham-Brown, M.P.; Smith, A.C.; Wilkinson, T.J. Characteristics of effective home-based resistance training in patients with noncommunicable chronic diseases: A systematic scoping review of randomized controlled trials. J. Sports Sci. 2021, 39, 1174–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marçal, I.R.; Fernandes, B.; Viana, A.A.; Ciolac, E.G. The Urgent Need for Recommending Physical Activity for the Management of Diabetes During and Beyond COVID-19 Outbreak. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 584642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, J.C.; Dean, S.; Siegert, R.; Howe, T.; Goodwin, V.A.; Nepogodiev, D.; Chapman, S.J.; Glasbey, J.C.D.; Kelly, M.; Khatri, C.; et al. A systematic review of measures of self-reported adherence to unsupervised home-based rehabilitation exercise programmes, and their psychometric properties. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e005044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.P.; Seixas, M.B.; Batalha, A.P.D.B.; Ponciano, I.C.; Oh, P.; Ghisi, G.L.D.M. Multi-level barriers faced and lessons learned to conduct a randomized controlled trial in patients with diabetes and prediabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. Cardiorespir. Physiother. Crit. Care Rehabil. 2021, 1, e42516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazilian Society of Diabetes. Diretrizes da Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes 2019–2020. Clannad. 2019; 419p. Available online: http://www.saude.ba.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Diretrizes-Sociedade-Brasileira-de-Diabetes-2019-2020.pdfhttps://portaldeboaspraticas.iff.fiocruz.br/ (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Callahan, C.M.; Unverzagt, F.W.; Hui, S.L.; Perkins, A.J.; Hendrie, H.C. Six-Item Screener to Identify Cognitive Impairment Among Potential Subjects for Clinical Research. Med. Care 2002, 40, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaley, J.A.; Colberg, S.R.; Corcoran, M.H.; Malin, S.K.; Rodriguez, N.R.; Crespo, C.J.; Kirwan, J.P.; Zierath, J.R. Exercise/Physical Activity in Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes: A Consensus Statement from the American College of Sports Medicine. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2022, 54, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Frederick, C.M.; Lepes, D.; Rubio, N.; Sheldon, K.M. Intrinsic Motivation and Exercise Adherence. Int. J. Sport Psychol. 1997, 28, 335–354. [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque, M.R.; Lopes, M.C.; de Paula, J.J.; Faria, L.O.; Pereira, E.T.; da Costa, V.T. Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Validation of the MPAM-R to Brazilian Portuguese and Proposal of a New Method to Calculate Factor Scores. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory and the Facilitation of Intrinsic Motivation, Social Development, and Well-Being Self-Determination Theory. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, M.P.; Alchieri, J.C. Motivation to practicing physical activities: A study with non-athletes. Psico-USF 2010, 15, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman-Beinart, N.A.; Norton, S.; Dowling, D.; Gavriloff, D.; Vari, C.; Weinman, J.A.; Godfrey, E.L. The development and initial psychometric evaluation of a measure assessing adherence to prescribed exercise: The Exercise Adherence Rating Scale (EARS). Physiotherapy 2016, 103, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Lira, M.R.; De Oliveira, A.S.; França, R.A.; Pereira, A.C.; Godfrey, E.L.; Chaves, T.C. The Brazilian Portuguese version of the Exercise Adherence Rating Scale (EARS-Br) showed acceptable reliability, validity and responsiveness in chronic low back pain. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2020, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Síntese de Indicadores Sociais: Uma Análise das Condições de vida da População Brasileira; Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística—IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2020; pp. 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Portal Prefeitura de Juiz de Fora. Contra a COVID-19—Onda Amarela Começa a Valer Neste Sábado em JF. Available online: https://www.pjf.mg.gov.br/noticias/view.php?modo=link2&idnoticia2=68611 (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Madsen, K.P.; Willaing, I.; Rod, N.H.; Varga, T.V.; Joensen, L.E. Psychosocial health in people with diabetes during the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic in Denmark. J. Diabetes Its Complicat. 2021, 35, 107858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, M.; Mackenzie, S.H.; Hodge, K.; Hargreaves, E.A.; Calverley, J.R.; Lee, C. Physical Activity and Psychological Well-Being During the COVID-19 Lockdown: Relationships with Motivational Quality and Nature Contexts. Front. Sports Act. Living 2021, 3, 637576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuley, E.; Blissmer, B. Self-efficacy determinants and consequences of physical activity. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2000, 28, 85–88. [Google Scholar]

- Echouffo-Tcheugui, J.B.; Selvin, E. Prediabetes and What It Means: The Epidemiological Evidence. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour: At a Glance. 2020. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/337001 (accessed on 29 August 2021).

- Leyton-Román, M.; de la Vega, R.; Jiménez-Castuera, R. Motivation and Commitment to Sports Practice During the Lock-down Caused by COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2021, 1, 622595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marashi, Y.M.; Nicholson, E.; Ogrodnik, M.; Fenesi, B.; Heisz, J.J. A mental health paradox: Mental health was both a motivator and barrier to physical activity during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0239244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, H.; Singh, T.; Arya, Y.K.; Mittal, S. Physical Fitness and Exercise During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Enquiry. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 590172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regeer, H.; Nieuwenhuijse, E.A.; Vos, R.C.; Jong, J.C.K.; van Empelen, P.; de Koning, E.J.P.; Bilo, H.J.G.; Huisman, S.D. Psychological factors associated with changes in physical activity in Dutch people with type 2 diabetes under societal lockdown: A cross-sectional study. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. 2021, 4, e00249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).