Abstract

C2H2-type zinc-finger transcription factors (ZFPs) play essential roles in plant stress signaling and development; however, their putative functions in safflower have not been systematically characterized. Leveraging the reference genome of the safflower cultivar ‘Jihong-1’ (Carthamus tinctorius L.), we investigated the C2H2 family and identified 62 CtC2H2 genes. Comparative phylogeny with Arabidopsis revealed six subfamilies characterized by shared features such as exon–intron organization and conserved QALGGH motif. Promoter analysis identified multiple light- and hormone-responsive cis-elements (e.g., G-box, Box 4, GT1-motif, ABRE, CGTCA/TGACG), suggesting potential multi-layered regulation. RNA-seq and qRT-PCR analysis identified tissue-specific candidate genes, with CtC2H2-22 emerging as the most petal-specific (6-fold upregulation), alongside CtC2H2-02, CtC2H2-23, and CtC2H2-24 in seeds (~3-fold), and CtC2H2-21 in roots (3-fold). Under abiotic stresses, CtC2H2 genes also demonstrated rapid and dynamic responses. Under cold stress, CtC2H2 genes showed a rapid temporal pattern of expression, with early increase for genes like CtC2H2-45 (>4-fold at 3–6 h) and a delayed increase for CtC2H2-23 at 9 h. A majority of CtC2H2 genes (8/12) were upregulated by ABA treatment, with CtC2H2-47 suggesting 3.5-fold induction. ABA treatment also led to a significant increase (2.5-fold) in total leaf flavonoid content at 24h, which is associated with the significant upregulation of flavonoid pathway genes CtANS (5-fold) and CtCHS (3.3-fold). Simultaneously, UV-B radiation induced two distinct expression patterns: a significant suppression of four genes (CtC2H2-23 decreased to 30% of control) and a complex fluctuating pattern, with CtC2H2-02 upregulated at 48 h (2.8-fold). MeJA elicitation revealed four complex expression profiles, from transient induction (CtC2H2-02, 2.5-fold at 3 h) to multi-phasic oscillations, demonstrating the functional diversity of CtC2H2-ZFPs in jasmonate signaling. Together, these results suggest stress and hormone-responsive expression modules of C2H2 ZFPs for future functional studies aimed at improving stress adaptation and modulating specialized metabolism in safflower.

1. Introduction

Safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.) is a widely cultivated member of the Asteraceae family valued in traditional Chinese medicine and as an oilseed crop, is reported to exhibit hypolipidemic [1], hypoglycemic [2], anti-inflammatory [3], antitumor [4,5], antithrombotic and neuroprotective activities [6]. Major metabolites include flavonoids, phenolic acids, and quinones. Among these, Flavonoids are multifunctional secondary metabolites, which have important functions in resistance to various stresses [5,7], mainly as antioxidants and regulators of plant polar growth hormone transport (PAT) [8]. Flavonoids are able to accumulate at the level of epidermal cell layers as protective UV radiation absorbers during UV-B stress [9,10], as well as acting as food repellents in the face of herbivores [11]. Flavonoids tend to increase antioxidant activity, promote photosynthesis, influence stomatal activity and regulate root growth, thereby enhancing plant resistance to abiotic stress [5,12,13]. When plants are exposed to cold stress, they are able to accumulate flavonoids in large quantities to increase their cold resistance and reduce cold damage [14].

Zinc-finger proteins (ZFPs) constitute a large transcription factor family in plants and are associated with growth, hormone signaling, and responses to environmental stress. ZFPs were first identified in Xenopus laevis oocytes [15] and contain a canonical Cys2/His2 motif (X_2C-X_2–4C-X_12H-X_2–8H) [16]. The tetrahedral “zinc finger” is formed when two Cys and two His residues chelate a zinc ion, stabilizing a β-hairpin/α-helix structure. ZFPs are classified by the number and spacing of these residues, including C2H2 (TFIIIA), C3HC4 (RING), C4 (GATA-type), and others [17]. The C2H2 subgroup constitutes one of the largest transcription-factor families in plants and is intimately linked to growth regulation. These genes are closely associated with plant development, hormonal signaling, and tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses. Their proteins typically harbor a QALGGH DNA-binding motif, an EAR repression motif, a nuclear-localization B-box, a DLN transcriptional-regulation box, and a leucine-rich L-box [18]. Prior studies indicate that C2H2 transcription factors contribute to stress tolerance (e.g., salinity and cold responses) and developmental processes, including trichome formation and flowering-time regulation [19,20,21]. Genome-wide studies now span numerous crops, including Arabidopsis [22], alfalfa [23], tomato [24], apple [25], rice [26], pepper [27], cucumis [28], potato [29], ginseng [30], lotus [31], and sweet potato [32]. Recent functional studies further show that overexpressing C2H2-ZFPs improves drought resilience in poplar [33], enhances root growth under osmotic stress in wheat [34], and modulates apple drought responses [35], highlighting their importance in biotechnological applications. However, the specific members of the CtC2H2 family involved, their response to hormonal and environmental cues, and their direct regulatory influence on the flavonoid pathway in safflower remain largely unexplored.

Despite extensive work in model and crop species, the C2H2 gene family has not been systematically characterized in safflower. Here, we provide the first genome-wide identification and systematic characterization of the CtC2H2 TF family. We identify 62 CtC2H2 genes in safflower and conduct a comprehensive analysis of their sequence features, phylogeny, and expression patterns under abiotic stresses and hormonal treatments, with a particular focus on flavonoid-related ABA responses. The primary objectives of this study were to classify the CtC2H2 family through phylogeny and motif analysis, to investigate their spatio-temporal and stress-responsive expression patterns, and to unravel the potential coordination between CtC2H2 TFs, ABA signaling, and the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway. By establishing this foundational framework, our work pinpoints key candidate CtC2H2 genes for future molecular breeding aimed at developing stress-resilient safflower cultivars with enhanced flavonoid content.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Abiotic-Stress Treatments

The Jihong No.1 safflower cultivar was germinated in moist trays and grown under controlled conditions (25 °C, 40% relative humidity, 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod) in a growth chamber. After 3 days of germination, the plants were cultured for 4 weeks, and uniformly sized seedlings were selected for several stress assays, including ultraviolet-B irradiation (UV-B irradiation (W/m−2), abscisic acid (ABA, 200 μM), methyl jasmonate (MeJA, 200 μM), and low temperature exposure (4 °C) [36]. MeJA and ABA were both prepared as stock solutions in anhydrous ethanol and diluted to 0.1% ethanol solutions for use. During spraying, plant leaves were thoroughly wet but not dripping. The control group received an equal volume of 0.1% ethanol solution and was cultivated under the same growth conditions. Seedlings were sprayed with the respective treatment solutions or sterile water (control) and maintained under the same growth conditions. For UV-B, samples were harvested at 0, 6, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h; for the other stresses at 0, 3, 6, 9, 12 and 24 h. True leaves from four-week-old safflowers were selected as samples. For each time point, three biological replicates were rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for subsequent RNA extraction and metabolite analysis.

2.2. Identification of C2H2 Genes in Carthamus Tinctorius

Protein sequences of Arabidopsis thaliana C2H2-ZFPs were downloaded from TAIR (https://www.arabidopsis.org/ (accessed on 18 July 2024)) and used as queries in a bidirectional BLASTP search against the “Jihong-1” safflower genome [37], implemented in TBtools II (Version 2.0). To obtain a comprehensive candidate list, we first screened plant C2H2-type zinc-finger proteins reported in the literature and then retrieved the Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profile for the C2H2 domain (PF00096) from Pfam 33.1 (https://pfam.xfam.org/ (accessed on 1 August 2024)). The PF00096 HMM was used in HMMER3 (v3.3) [38] to search the safflower proteome, complementing the BLASTP approach and ensuring recovery of highly divergent members. Putative proteins were analyzed using the NCBI Conserved Domain Search to confirm the presence of the canonical Cys2-His2 domain prior to classification as CtC2H2 family members. Physicochemical parameters, including molecular weight (MW), theoretical isoelectric point (pI) and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY) were calculated with ProtParam (http://web.expasy.org/protparam/ (accessed on 29 August 2024)). Sub-cellular localization was predicted in WoLF PSORT (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/ (accessed on 30 July 2024)). Finally, redundant isoforms were removed, and domain-validated proteins were cataloged as CtC2H2 family members for downstream analyses.

2.3. Conserved Motifs and Gene Structure Organization of the CtC2H2-ZFPs

Conserved motifs were identified with MEME Suite v5.5.3 (https://meme-suite.org/ (accessed on 15 September 2024)) [39]) using a maximum of 15 motifs (width = 6–60 aa). The MEME suite (Version 5.5.8) was used under the following key parameters: the motif distribution was set to “Zoops” and low-complexity filtering was enabled. Sequence logos were rendered in WebLogo 3 [40]. Coding sequences were aligned to their genomic loci, and exon–intron arrangements were extracted in TBtools v2.315 [41]. Motif and gene-structure diagrams were integrated side-by-side in TBtools for comparative visualization.

2.4. Phylogenetic Analysis of CtC2H2s Family

In order to perform comparative phylogenetic analysis, Protein sequences of Arabidopsis thaliana C2H2-ZFPs were included as reference taxa. Multiple-sequence alignment and neighbor-joining phylogeny were generated in MEGA 11 [42]. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Jones-Taylor-Thornton (JTT) model, with pairwise deletion applied to gaps and missing data. The reliability of the tree was assessed with 1000 bootstrap replications. The phylogenetic tree was edited and color-coded in EvolView v2 (https://www.evolgenius.info/evolview-v2/ (accessed on 1 October 2024)) [43] to further improve the quality of the tree.

2.5. Cis-Regulatory Elements Analysis in CtC2H2 Promoters

Based on the nucleotide sequences 2000 bp upstream of the transcription start site (TSS) of the 62 CtC2H2 genes downloaded from the safflower Genome Database. Promoter regions (2000 bp upstream of the transcription start site) were analyzed using PlantCARE (Plant Cis-Acting Regulatory Element) [44] (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/ (accessed on 15 October 2024)) to identify cis-acting regulatory elements. The identified regulatory elements were categorized based on their functional roles, including light responsiveness, hormone regulation, and stress-related motifs [45]. The results and organization of cis-acting elements were visualized using TBtools [41].

2.6. Functional Annotation Analysis of CtC2H2 Genes

Gene Ontology (GO) annotations were assigned using Blast2GO using an E-value significance threshold of 1.0E-3 [46], categorizing CtC2H2 genes into biological process, cellular component, and molecular function terms. The Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was conducted to categorize the genes based on their functional roles, including but not limited to transcriptional regulation, zinc ion binding, and response to abiotic stress [47]. The enrichment was calculated using Fisher’s Exact Test, with a False Discovery Rate (FDR) significance threshold of <0.05. The data were processed, and the corresponding graphs, including bar plots and scatter plots representing GO term distributions, were plotted using R 4.3.0 [48] with the ggplot2 package 3.4.0. [49].

2.7. RNA Extraction and Real-Time Quantitative PCR

During the expression validation phase, we screened these genes and selected 12 candidate genes that were rich in elements responsive to cold, light, methyl jasmonate and abscisic acid. Gene-specific primers were designed using Primer3Plus [50] and synthesized by Bioengineering (Changchun) Co., Ltd. (Changchun, China) (primers listed in Supplementary Table S2). Total RNA was extracted from samples using RNAiso Plus reagent (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA quality and concentration were verified using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA; Software version 3.8.0) and agarose gel electrophoresis. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using ToloScript All-in-one RT EasyMix for qPCR (TOLOBIO, Shanghai, China), with oligo (dT) primers in a 20 μL reaction volume.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed on a QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) using 2 × Q5 SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Universal) (TOLOBIO Biotech, Shanghai, China). Each reaction mixture (20 μL total volume) contained: 2 × Q5 SYBR qPCR Master Mix (10 μL); Gene-specific forward and reverse primers (0.4 μL each, 10 μM); cDNA template (1 μL); Nuclease-free dH2O (8.2 μL). The qRT-PCR analysis was performed using standard cycling conditions (95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 30 s). Melting-curve analysis was used to verify amplicon specificity [51]. All reactions were performed in technical triplicates, along with no-template controls (NTCs) for each primer pair. The expression data were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt method [52], with Ct60S (KJ634810) employed as the internal reference gene for normalization [53]. Relative gene expression levels were calculated and presented as fold-changes compared to control samples.

2.8. Tissue-Specific CtC2H2 Gene Expression and Validation

To examine the spatial and temporal expression patterns of the CtC2H2 gene family, we analyzed the transcriptome data of safflower across multiple developmental stages [54]. The expression profiles (FPKM values) of CtC2H2 genes were examined in various tissues including root, stem, leaf, bud, primordial, full bloom, decline, 10-day seedlings, 20-day seedlings, and 30-day seedlings. Hierarchical clustering analysis was performed, and heat maps were plotted to visualize expression patterns using TBtools II (Version 2.0) software [41], with a red to blue color gradient indicating relative transcript abundance high to low levels, respectively. This visualization approach effectively revealed tissue-specific and developmentally regulated expression patterns among CtC2H2 family members [55]. For experimental validation, twelve CtC2H2 genes containing cis-acting regulatory elements associated with hormone-responsive pathways were selected for quantitative real-time PCR analysis according to the previously discussed method [51].

2.9. Determination of Total Flavonoid Content and Detection of Key Flavonoid-Biosynthetic Genes

A 0.10 g aliquot of freeze-dried leaf tissue was finely ground and extracted with 2 mL of HPLC-grade methanol. The suspension was sonicated (40 kHz) at 50 °C for 1 h, cooled on ice, and centrifuged at 12,000× g for 10 min. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.22 µm PTFE syringe filter (Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and stored at −20 °C until analysis. Chromatographic separation and quantification were performed on an Agilent 1200 HPLC (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a ZORBAX 300SB-C18 column (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) (5 µm, 4 m × 5 m). The isocratic mobile phase consisted of methanol: 0.4% (v/v) formic-acid water = 1:1 at 1 mL min−1. The detection was set at 360 nm and 25 °C. Rutin (Solarbio, Beijing, China) served as the external standard which was eluted at a retention time of 5.22 min with a symmetric peak shape and clear baseline separation from potential impurities. A five-point calibration curve (0.01–0.20 mg mL−1; R2 > 0.999) was used to express results as mg rutin g−1 DW [56]. Three biological replicates and three technical injections were analyzed for each treatment. Expression of key flavonoid-biosynthetic genes (CtCHS, CtCHI, CtF3H, CtF3′H, CtFLS, CtDFR, CtANS) was quantified by qRT-PCR exactly as described in 2.8; primer sequences are provided in Table S1. Relative transcript levels were normalized to Ct60S and calculated with the 2−ΔΔCt method [52].

2.10. Statistical Analysis

The qRT-PCR fold changes were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method [52]. For each experimental treatment, three independent biological replicates were analyzed, with each replicate measured in three technical repetitions. The data from the technical replicates were averaged to represent a single biological replicate. All numerical values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of these three biological replicates. Data processing and graph generation were performed using GraphPad Prism v8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc test, with significance levels denoted as * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001. For datasets that violated the assumption of homogeneity of variances, we have replaced the analysis with the more robust Welch’s ANOVA followed by the Games–Howell post hoc test.

3. Results

3.1. Identification of CtC2H2 Genes and Analysis of Physicochemical Properties

A total of 62 C2H2-type zinc-finger transcription factors were retrieved from the safflower genome by BLASTP screening and subsequent verification with the NCBI’s Batch CD-Search software (accessed on 1 August 2024; with the default parameters (E-value threshold 0.01, CDD database version 3.20) to confirm the presence of the canonical Cys2/His2 domain. These genes were designated CtC2H2-01-62 (Table S2). Protein lengths span 134–1191 aa, with calculated molecular weights of 15.57–132.76 kDa and theoretical pI values of 4.84–10.91. Instability indices vary from 31.1 to 85.9; only CtC2H2-17, -19, -53, and -57 fall below the empirical stability threshold (II < 40). Aliphatic indices range between 47.64 and 79.93, whereas all CtC2H2 proteins exhibited negative grand average hydropathicity (GRAVY) scores ranging from −1.137 to −0.305, indicating hydrophilic properties. The WoLF PSORT webtool classified every CtC2H2 protein as nuclear, which may reflect their function as transcription factors [57]. The CtC2H2 complement (n = 62) is close to the 58-member C2H2 set recently documented in apple [25] yet significantly smaller than the 99 genes identified in tomato [24], highlighting lineage-specific expansion among dicotyledons.

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

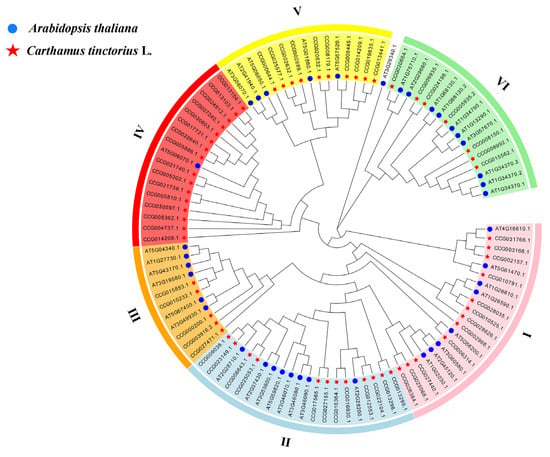

To clarify the evolutionary relationship between safflower and Arabidopsis C2H2-type zinc-finger proteins, we constructed a phylogenetic tree from 62 CtC2H2 proteins and 39 Arabidopsis C2H2 members using MEGA 11 (neighbor-joining algorithm, 1000 bootstrap replications) [42]. A total of six phylogenetic subfamilies (Ⅰ–Ⅵ) were identified based on conserved domain architecture and sequence similarity (Figure 1). These classifications were mainly consistent with the clades distribution reported for tomato [24] and apple [25]. Subfamily counts were as follows: I, 12 genes; II, 12 genes; III, 5 genes; IV, 16 genes; V, 10 genes; and VI, 7 genes, together accounting for all 62 CtC2H2 members. This pattern suggests lineage-specific gene expansion, particularly in subfamily IV, which harbors > 25% of the total family and may reflect adaptive diversification in safflower.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree of C2H2 proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana and Carthamus tinctorius. The C2H2 protein sequences of the two species were aligned by MEGA X and the tree was built with the NJ method. The tree was further categorized into six distinct subfamilies in different colors. Proteins were grouped into six subfamilies (Ⅰ–Ⅵ) based on conserved domain composition and sequence similarity. Each subfamily is color-coded: I (pink), II (light blue), III (orang), IV (red), V (yellow), and VI (green).

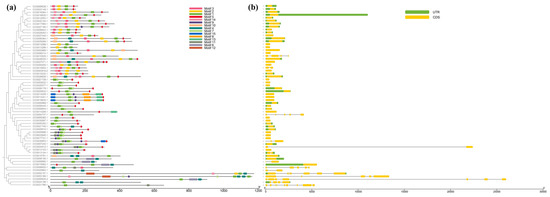

3.3. Conserved Motifs and Gene Structural Features of the CtC2H2-ZFPs

In order to reveal the diversity of the CtC2H2 family, 15 conserved motifs in its full-length protein sequence were analyzed according to the phylogenetic tree using MEME and TBtools, and the 15 motifs analyzed were named motif 1–15 (Figure 2). Among them, motif 1 is present in 62 CtC2H2 proteins, suggesting that it is highly conserved and potentially important in the CtC2H2 family. In addition, other motifs have inter-family similarities. For example, subfamilies I, II, and III all contain motif 1 and motif 2, and subfamilies IV and V all contain motif 1 and motif 7. motif 1 and motif 2 both contain the QALGGH sequence, a core sequence, and motif 5 contains the DLNL sequence, an EAR motif that has been shown to play an important role in transcriptional repression and abiotic stress response (Figure S1). Similarly, motif 3 contains EXEXXAXCLXXL (L-box), a leucine-rich region thought to play an important role in protein–protein interactions. Among the C2H2-ZFPs identified, four of the 12 members of subfamily I are intron-deficient; there are no introns in subfamilies II and V; among the five members of subfamily III, one intron is missing; among the 16 members of subfamily IV, four are intron-deficient; and among the seven members of subfamily VI, five are intron-deficient. Among them, subfamily IV has the highest proportion of intron-deficient genes (71.4%).

Figure 2.

Structural features of the CtC2H2 zinc finger gene family in safflower. (a) Conserved motif composition of CtC2H2 proteins identified using MEME suite. Colored boxes represent distinct conserved motifs, and their relative positions and arrangements indicate potential functional divergence among CtC2H2 members. (b) Gene structure organization of CtC2H2 family members, showing the distribution of exons, introns, and untranslated regions (UTRs). Exons are represented by colored boxes, introns by black lines, and UTRs by gray boxes. The comparison of motif distribution and gene structure highlights evolutionary conservation and structural diversity within the CtC2H2 family.

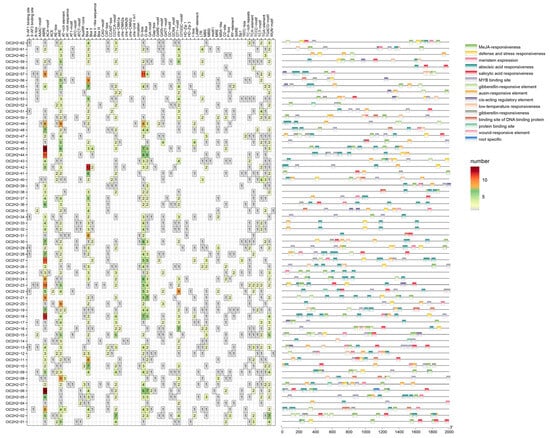

3.4. Analysis of Cis-Acting Elements of CtC2H2 Genes Promoters

The promoter regions of 62 CtC2H2 genes upstream of the 2000 bp fragment in safflower were analyzed, and the results showed that the cis-acting elements of the safflower C2H2 promoter region could be classified into three major categories: growth and developmental elements, hormone-responsive elements, and biotic and abiotic stress elements (Figure 3). Most of the safflower C2H2 was enriched with light-responsive elements, such as G-box, Box 4, and GT1-motif, suggesting that safflower C2H2 may be involved in the regulation of light signaling pathways that affect plant photomorphogenesis. Most CtC2H2 promoters contain hormone responsive elements, such as ABRE (abscisic acid responsive element), CGTCA-motif (methyl jasmonate responsive element), TGACG-motif (methyl jasmonate responsive element). In addition, the promoter sequences of CtC2H2 genes contained elements related to biotic and abiotic stress response such as drought, flooding, and cold responsive elements. Several CtC2H2 members also contained multiple MYB binding sites, suggesting regulatory potential of safflower C2H2 genes related to growth and development and may play important roles in stress response.

Figure 3.

Analysis of cis-acting elements of the safflower C2H2-type zinc finger protein family promoter. The cis-acting elements were predicted in the promoter sequences of the CtC2H2 genes. Rectangular boxes of distinct colored boxes represent the different types of cis-acting elements.

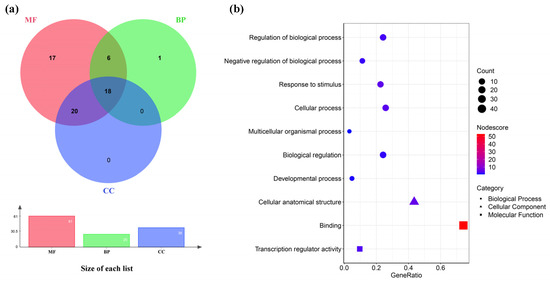

3.5. Functional Categorization and Annotation Enrichment of CtC2H2 Gene Family

To further understand the functional relationships among the CtC2H2s gene family members, the CtC2H2 gene family was analyzed by GO functional annotation for functional annotation (Figure 4). Among the 62 transcripts, 62 genes were annotated to at least one of the three major functions: 27 were annotated to biological process (BP), 38 to cellular component (CC), and 61 to molecular function (MF). Eighteen of these transcripts were annotated for only one function, 26 transcripts were annotated with two major functions, and 18 transcripts were annotated with three major functions. At Level 2 (Figure 4b), seven sub-levels were enriched in BP: regulation of biological process (GO:0050789), negative regulation of biological process (GO:0048519), response to stimulus (GO:0050896), cellular process (GO:0009987), multicellular organismal process (GO:0032501), biological regulation (GO:006500), developmental process (GO:0032502); one sub-level was enriched as a cellular anatomical structure (GO:0110165) in CC; and two sub-levels were enriched in MF sub-levels for binding (GO:0005488), transcription regulator activity (GO:0140110). GO functional classification and enrichment suggested diverse transcriptional regulation and stress responsiveness, indicating potential regulatory functions.

Figure 4.

Functional categorization and annotation enrichment analysis of the CtC2H2 genes. (a) A Venn network of the CtC2H2 genes were among the biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular function (MF) functional categories; (b) The CtC2H2 gene was categorized into ten Gene Ontology (GO) functional categories: seven biological process (BP) categories (circles), one cellular component (CC) category (triangles), and two molecular function (MF) categories (squares).

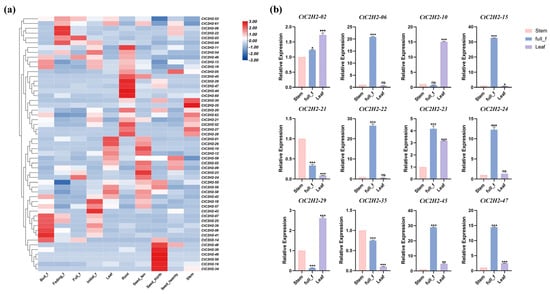

3.6. Tissue-Specific Expression Analysis of C2H2 Family Genes in Safflower

In order to study the expression pattern of the C2H2 zinc finger protein family genes in safflower, the transcriptome data of safflower cultivar “Jihong No.1” were analyzed at the root, stem, leaf, flower and seed stages. As shown in Figure 5a, the transcriptome data revealed distinct tissue-specific expression profiles. Notably, CtC2H2-02, CtC2H2-23, and CtC2H2-24 were highly expressed in seeds, with CtC2H2-02 showing approximately 3-fold increased expression compared to other tissues. Similarly, CtC2H2-06 and CtC2H2-22 were highly specific to petals during the fading stage, exhibiting peak expressions of 3-4-fold and 6-fold greater than in leaves, respectively. In contrast, CtC2H2-10 was markedly upregulated in leaves (2-fold), while CtC2H2-21, CtC2H2-29, and CtC2H2-47 showed strong root-specific expression, with CtC2H2-21 reaching 3-fold enrichment in roots. Finally, CtC2H2-35 demonstrated its highest expression in stems, at 2-fold higher than in other tissues. Based on the presence of stress and hormone-responsive cis-acting elements, twelve CtC2H2 genes were selected for experimental validation via qRT-PCR (Figure 5b). The trends of these 12 genes in stems, leaves, and flowers were consistent with the transcriptome data, proving the accuracy of the transcriptome data.

Figure 5.

Gene expression analysis of the CtC2H2-ZFPs. (a) Expression profiles of the safflower CtC2H2 gene family in different tissues; (b) qRT-PCR Validation of Expression Patterns of 12 CtC2H2 Genes in Roots, Stems, and Petals at Bloom Stage (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001; ns = non significant).

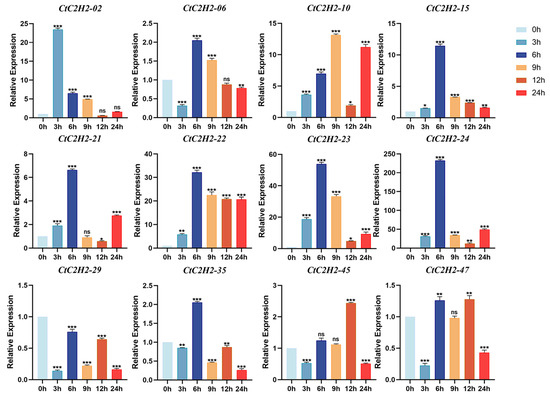

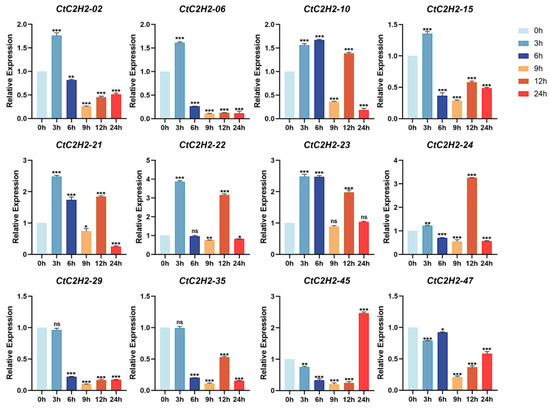

3.7. Cold Stress Triggers Differential and Dynamic Regulation of CtC2H2-ZFPs

The gene expression analysis was carried out in the leaves of safflower seedlings treated with cold stress (4 °C) at different time points (3, 6, 9, 12, 24 h), and normalized expression was demonstrated using normothermic treatment (25 °C) as the 0 h control. As shown in Figure 6, the five genes CtC2H2-02, -06, -15, -22, and -45 exhibited a transient expression pattern, peaking at different time points. These five genes reached the peak expression after 3, 6 or 12 h of cold treatment, and decreased thereafter. Similarly, a subset of seven CtC2H2 genes exhibited a diverse pattern, reaching maximum expression at 6–9 h before undergoing a secondary upregulation phase at 12–24 h. However, the expression trend of CtC2H2-29 gene exhibited transient induction followed by partial downregulation over time, although its overall expression was lower than that of the control group. The dissociation curve analysis for qRT- PCR primer specificity validation are given in (Figure S2). Together, these findings suggested that CtC2H2 genes responded differently to cold treatments, indicating diverse regulatory roles in cold-stress responses.

Figure 6.

Expression patterns of CtC2H2-ZFP genes in safflower under cold stress. Relative transcript levels of selected CtC2H2-ZFP genes were analyzed at 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h following treatment with 4 °C. Expression values were quantified by qRT-PCR and normalized against the internal control gene. Error bars represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared with the 0 h control (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001; ns = non significant), revealing distinct temporal expression patterns of CtC2H2-ZFPs in response to cold stress.

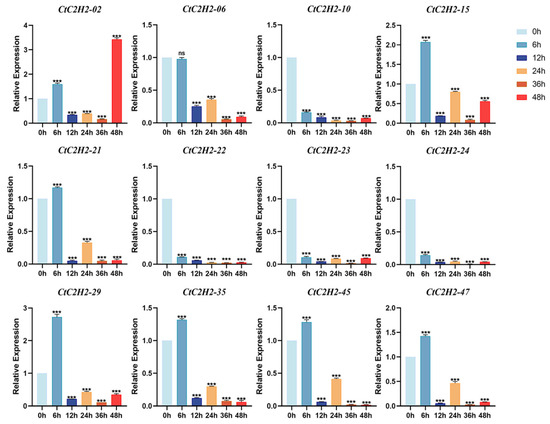

3.8. CtC2H2-ZFPs Exhibit Distinct Induced and Repressed Expression Profiles Under UV-B Exposure

We further investigated the expression profile of CtC2H2 genes in the leaves of safflower seedlings exposed to UV-B stress at multiple time points 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h. The results showed that CtC2H2 genes showed distinct induced and repressed expression patterns under the exposure of UV-B stress at variable time periods. For example, the expression level of four genes such as CtC2H2-10, CtC2H2-22, CtC2H2-23 and CtC2H2-24 were significantly suppressed at a consistent pattern when treated with UV-B stress at almost every time point. In contrast, a more complex and dynamic expression pattern was observed for the remaining CtC2H2 genes. For instance, the expression pattern of CtC2H2-15, CtC2H2-21, CtC2H2-29, CtC2H2-35, and CtC2H2-45, showed upregulation at 6 h when compared to the control group, suggesting the immediate response of these genes to UV-B perception (Figure 7). However, the expression of CtC2H2-02 showed maximum increase at a further 48 h timepoint than the control. Together, the diverse induction of CtC2H2 genes suggested their specialized role in the short longer-term adaptive or repair processes, which is potentially involved in the restoration of cellular homeostasis after UV-B stress.

Figure 7.

Expression patterns of CtC2H2-ZFP genes in safflower under UV-B stress. Relative expression levels of selected CtC2H2-ZFP genes were measured at 0, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h following UV-B radiation treatment. Transcript abundance was quantified by qRT-PCR and normalized against the internal reference gene. Error bars represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three biological replicates. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences compared with the 0 h control (*** p < 0.001; ns = non significant), illustrating time-dependent transcriptional responses of CtC2H2-ZFPs to UV-B-induced stress.

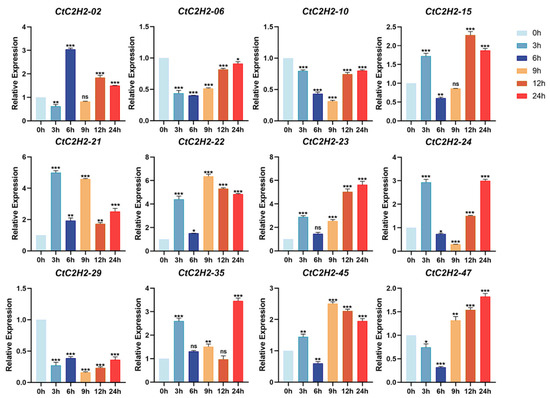

3.9. Differential Expression Responses of CtC2H2-ZFP Genes Under ABA Treatments

To investigate the role of CtC2H2 genes under hormonal treatment, we investigated their expression following treatment with 200 μM ABA at different time periods (0, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h). As shown in Figure 8, ABA treatment significantly induced the expression of several CtC2H2 genes, suggesting their potential involvement in ABA-responsive pathways. For instance, a group of eight CtC2H2 genes (CtC2H2-02, -15, -21, -22, -23, -24, -35, -45) displayed a consistent pattern: their expression first increased at 3 or 6 h, then decreased, and finally increased again at 9 or 12 h after ABA treatment. On the other hand, the expression level of three genes (CtC2H2-06, -10, -47) decreased to a minimum at 6–9 h timepoint and then recovered (Figure 8). However, the expression peaks of CtC2H2-06 and -10 never rose above control levels, whereas CtC2H2-47 showed a significant peak higher than the control. Together, these results suggested both induced and repressed CtC2H2 members and define their specific temporal expression profiles, providing a foundation for understanding their specialized functions in ABA signaling.

Figure 8.

Induced and repressed expression pattern of CtC2H2-ZFP genes in safflower under ABA treatment. Relative transcript levels of selected CtC2H2-ZFP genes were analyzed at 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h following treatment with 200 μmol·L−1 abscisic acid (ABA). Expression values were quantified by qRT-PCR and normalized against the internal control gene. Error bars represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared with the 0 h control (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001; ns = non significant), revealing distinct temporal expression patterns of CtC2H2-ZFPs in response to ABA-induced stress.

3.10. Distinct and Complex Expression Profiles of CtC2H2-ZFPs Under MeJA Stress

To further extend the investigation of CtC2H2 genes expression in the leaves of safflower seedlings under hormonal treatment, we carried out their expression profiling MeJA treatment at different time periods (0, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h). The results showed that genes like CtC2H2-02 and CtC2H2-47 demonstrated a rapid initial upregulation at 3–6 h, and a subsequent decline to at 9 h (Figure 9). In addition, CtC2H2-06 and CtC2H2-29 exhibited a single, transient wave of expression suggesting increased and/or stable expression at 3 h, followed by a significant and continuous decrease from 6 h onwards. On the contrary, most of CtC2H2 genes including CtC2H2-10, -15, -21, -22, -23, -24, and -35, showed periodic enhanced expression at 3 h, 6 h, and 12 h (Figure 9). While CtC2H2-45 exhibited a unique pattern of steady decrease after MeJA treatment, only reaching its peak expression at 24 h. These results suggest the MeJA treatment induced expression of a subset of CtC2H2 genes in a time-dependent manner.

Figure 9.

Expression dynamics of CtC2H2-ZFP genes in safflower under MeJA treatment. Relative transcript levels of selected CtC2H2-ZFP genes were determined at 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h following treatment with 200 μmol·L−1 methyl jasmonate (MeJA). Gene expression was quantified by qRT-PCR and normalized against the internal control gene. Error bars represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate statistically significant differences compared with the 0 h control (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001; ns = non significant), highlighting the transcriptional responses of CtC2H2-ZFPs to MeJA-induced signaling.

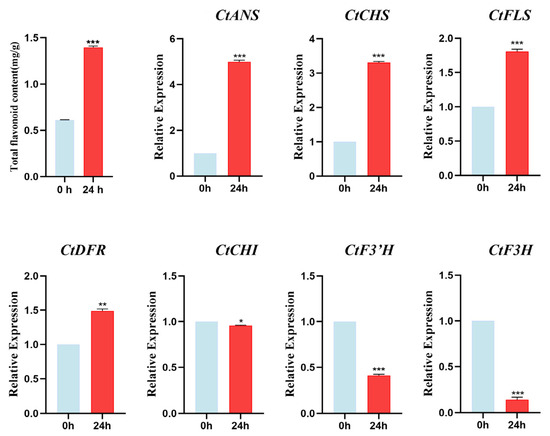

3.11. Changes in Total Flavonoids Content and Key Genes of the Flavonoid Pathway Under ABA Treatment

As shown in Figure 7 above, the expression of most safflower CtC2H2-ZFPs increased significantly at 24 h timepoint under 200 μmol/L ABA treatment. Therefore, we tend to extract the total flavonoids content from untreated (0 h) versus ABA-treated 24 h safflower leaves. As demonstrated in Figure 10, following a 24 h exogenous ABA treatment, a substantial and highly significant accumulation (paired t-test, p < 0.001) of total flavonoid content was observed in safflower, with a notable increase from 0.56 mg/g DW to 1.39 mg/g DW, representing an approximate 2.5-fold enhancement. In line with this observation, the expression levels of multiple pivotal genes within the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway underwent substantial alterations. Among them, the expression of CtANS and CtCHS was most significantly increased, with 5.0-fold and 3.3-fold increases, respectively (both p < 0.001). Furthermore, CtFLS and CtDFR expression levels increased significantly by 1.8-fold (p = 0.001) and 1.5-fold (p < 0.01), respectively. In contrast, the expression of CtF3H and CtF3′H was found to be significantly repressed, with levels decreasing to 14% and 41% of the control levels, respectively (p < 0.001 for both). These findings suggest that ABA effectively promotes flavonoid synthesis and accumulation in safflower by synergistically enhancing the expression of CtCHS, CtFLS, CtDFR, and CtANS genes, while concurrently suppressing the expression of CtF3H and CtF3′H genes. These correlations suggest that CtC2H2 genes may influence flavonoid biosynthesis, potentially through ABA signaling pathways.

Figure 10.

Total flavonoid content and expression profiles of key flavonoid biosynthetic genes under ABA treatment. The upper panel shows the total flavonoid content in safflower was determined at 0 h and 24 h following treatment with 200 μmol·L−1 abscisic acid (ABA). Data represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three biological replicates. The lower panel shows relative expression levels of key enzyme genes involved in the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway were analyzed by qRT-PCR at 0 h and 24 h under the same ABA treatment conditions. Transcript levels were normalized against the internal reference gene. Statistical significance determined by paired Student’s t-test compared with the 0 h control is indicated (* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001), revealing ABA-induced modulation of flavonoid accumulation and associated biosynthetic gene expression.

4. Discussion

C2H2-type zinc-finger proteins (ZFPs) represent one of the important families of transcriptional factors in plants. This largest but poorly explored transcription factors are known to mediate responses to developmental cues and environmental stresses in plants [33,34,35]. Studies have shown that members of C2H2 demonstrated reduced sensitivity to ABA in apple, and improves developmental cues in Arabidopsis under drought stress [35]. Similarly, C2H2-type ZFPs in tobacco and soybean showed enhanced cold tolerance responses by regulating the ABA-induced expression of cold-responsive genes [58]. Prior studies also suggested the potential role of C2H2-type ZFPs in regulating ABA and MeJA mediated abiotic stress response in a variety of plant species [59,60,61]. The current study presents the genome-wide identification CtC2H2 in safflower and elucidates their distinct expression bias under abiotic stress (cold and UV-B) and hormonal treatment (ABA and MeJA).

4.1. C2H2-Type ZFPs Expression Bias Under Cold Stress

The investigation of our expression analysis revealed distinct temporal patterns among CtC2H2 genes under cold stress, with individual genes exhibiting peak expression at different time intervals (Figure 6). This dynamic expression suggests a tightly regulated transcriptional network activated in response to cold stress. Such observations are consistent with earlier studies emphasizing the pivotal role of C2H2 genes in orchestrating cold-responsive expression [62,63,64]. The transient expression profiles observed in our study further support the notion that multiple transcription factors function in a coordinated manner to regulate plant cold tolerance. As reported in several prior studies, C2H2-type ZFPs are widely recognized as central regulators of cold stress responses, primarily through ABA-mediated signaling cascades [65,66]. Plant species including Arabidopsis [67], soybean [36], and rice [65] demonstrated that the overexpression of key C2H2 ZFPs led to cold-responsive (COR) genes via ABA-responsive promoter elements, promoted osmolyte biosynthesis, and improved ion homeostasis. For instance, SCOF-1 and members of the AZF/STZ family enhance cold tolerance by strengthening ABA-regulated transcriptional pathways, while ZFPs such as GmZF1 and ZFP182 elevate COR gene expression, proline accumulation, and other protective metabolites that mitigate cellular damage [67]. In line with these findings, CtC2H2 genes in safflower highlight the conserved role of this transcription factor family in cold acclimation across plant species (Figure 6). It is well established that ABA accumulates rapidly upon exposure to cold, subsequently activating downstream genes enriched in ABA-responsive cis-elements [68]. The regulation imparted by CtC2H2 genes likely contributes to this adaptive cascade by fine-tuning stress-responsive transcription, thereby facilitating essential physiological adjustments such as osmotic balance, membrane stabilization, and oxidative stress mitigation. Collectively, our results suggest that safflower employs a complex regulatory framework involving temporally dynamic CtC2H2 gene activation to enhance cold acclimation.

4.2. Regulation of C2H2-Type ZFPs Expression Under UV-B Stress

The differential expression patterns of CtC2H2 genes under UV-B exposure also led us towards understanding the complexity of transcriptional regulation activated during UV-induced stress (Figure 7). Our findings revealed that while several CtC2H2 genes were consistently repressed across all time points, a substantial subset of genes showed dynamic and time-dependent induction (Figure 7). This divergence suggests that C2H2-type ZFPs function in distinct regulatory modules that collectively contribute to UV-B perception, signaling, and downstream acclimation responses. For instance, the continuous suppression of CtC2H2-10, CtC2H2-22, CtC2H2-23, and CtC2H2-24 suggested that these genes may act as negative modulators of UV-B stress-responsive pathways or participate in growth-associated processes that are downregulated under UV-B stress to conserve energy and minimize damage. On the contrary, genes such as CtC2H2-15, CtC2H2-21, CtC2H2-29, CtC2H2-35, and CtC2H2-45 exhibited rapid induction at the 6 h time point, indicating an early activation phase potentially linked to UV-B signal transduction, ROS scavenging, or initiation of protective mechanisms. The strong late induction of CtC2H2-02 at 48 h further reflects a distinct role in long-term adaptive or repair responses, possibly associated with DNA damage recovery, membrane stabilization, or restoration of cellular homeostasis.

Comparable temporal expression biases of CtC2H2 and other classes of transcription factors families have been reported in other plant species, which mainly contribute to UV-B tolerance by modulating antioxidant pathways, DNA repair mechanisms, and flavonoid biosynthesis [69,70,71]. The varied responses observed in safflower suggested that CtC2H2 genes participate at multiple stages of the UV-B stress response, from early perception to late acclimation, indicating their functional diversity within this regulatory landscape (Figure 7). Collectively, the induction–repression module suggests that safflower employs a finely tuned transcriptional network of C2H2-ZFPs to mitigate UV-B-induced damage and maintain physiological stability under elevated radiation.

4.3. Hormonal-Induced Regulatory Modules of CtC2H2-ZFPs

The diverse expression patterns of CtC2H2 genes following ABA and MeJA treatments highlight the multifaceted regulatory roles of C2H2-type ZFPs in hormone-mediated stress responses. We also observed that ABA treatments induced notable transcriptional adjustments and coordination with flavonoid biosynthesis across multiple CtC2H2 members, reflecting their potential roles in ABA-dependent signaling pathways. For example, under ABA treatment, a distinct cluster of genes including CtC2H2-02, -15, -21, -22, -23, -24, -35, and -45, demonstrated early induction at 3–6 h, a decline at mid-points, and a subsequent secondary increase at 9–12 h. This dual-peak profile suggests a possible involvement in both early ABA perception and later downstream regulatory events, potentially mediating transcriptional reprogramming associated with stress adaptation, stomatal regulation, or osmotic adjustment. Conversely, CtC2H2-06, -10, and -47 were initially downregulated, reaching minimum expression at 6–9 h; however, only CtC2H2-47 significantly regained its expression level above control levels. Such contrasting responses imply functional specialization, where certain C2H2-ZFPs may act as positive regulators of ABA-responsive pathways while others serve as negative modulators, fine-tuning ABA signal amplitude to prevent excessive or prolonged responses. This distinct regulatory pattern of expression aligns with findings in Arabidopsis [67], rice [65], and soybean [67], where C2H2-type ZFPs are known to modulate ABA-triggered processes such as osmolyte biosynthesis, ROS detoxification, and transcriptional activation of stress-responsive genes.

In comparison, MeJA treatment also triggered more heterogeneous and transient expression patterns across the CtC2H2 gene family. Early peaks observed in CtC2H2-02 and CtC2H2-47, along with the single-wave responses of CtC2H2-06 and -29, suggest rapid JA-mediated activation followed by attenuation, possibly reflecting their involvement in defense-related signaling or early JA perception. Additionally, most genes including CtC2H2-10, -15, -21, -22, -23, -24, and -35, exhibited periodic induction at multiple time points, suggesting repeated engagement in JA-regulated transcriptional cycles. The distinctive late-stage peak of CtC2H2-45 further suggests roles in prolonged or secondary MeJA responses, potentially linked to longer-term defense or stress recovery mechanisms. Consistent with our findings, previous studies have shown that the expression of ZPT2-3 is activated through JA-dependent signaling pathways but ethylene-independent mechanisms, highlighting the sensitivity of C2H2-ZFPs to JA-mediated regulatory cues [72,73]. Moreover, JA can function together with ethylene through integrators such as ERF1, further contributing to the modulation of stress-responsive transcriptional networks [74]. These observations support the diverse and time-dependent induction patterns of CtC2H2 genes under MeJA treatment in our study, indicating that select CtC2H2-ZFPs may act as important components of JA-driven defense and stress adaptation pathways in safflower.

Although MeJA influenced a broad subset of CtC2H2 genes, the ABA-induced transcriptional shifts were more prominent, structured, and consistent across family members. This emphasizes the centrality of ABA signaling in orchestrating C2H2-ZFP-mediated responses in safflower. The presence of early-response spikes, mid-phase suppression, and late-response surges under ABA treatment strongly suggests that CtC2H2 genes integrate temporal ABA signals to mediate finely tuned regulatory programs. Such coordinated transcriptional dynamics may reflect the involvement of C2H2-ZFPs in ABA-regulated processes such as drought and cold tolerance, stomatal behavior, metabolic adjustment, and ABA-responsive gene activation via ABRE-containing promoters. Collectively, the combined hormone-responsive expression landscape underscores the functional diversity of CtC2H2 genes, with ABA emerging as the dominant hormonal regulator. These insights highlight the potential of specific CtC2H2 members as key molecular nodes for enhancing ABA-mediated stress resilience and provide a foundation for future functional characterization and breeding strategies aimed at improving hormone-responsive stress tolerance in safflower.

4.4. ABA-Induced Flavonoid Accumulation and Potential Regulatory Roles of CtC2H2-ZFPs

In this study, the observed increase in total flavonoid content following ABA treatment provides compelling evidence that ABA-induced regulation of CtC2H2 functions as a key positive regulator of flavonoid biosynthesis in safflower. The ~2.5-fold increase in total flavonoids after 24 h of exogenous ABA application indicates a strong metabolic reprogramming toward enhanced secondary metabolite production. This response aligns with well-established findings in other plant species, where ABA acts as a central signaling molecule that modulates stress-responsive metabolic pathways, including those associated with antioxidant and protective compounds such as flavonoids [75,76]. The transcriptional upregulation of major biosynthetic genes including CtCHS, CtFLS, CtDFR, and CtANS, further reinforces the notion that ABA promotes flux through the flavonoid pathway induced by CtC2H2 expression as observed in other plant species [77,78]. The marked increases in CtANS and CtCHS expression suggest an activation of early and late biosynthetic steps, ultimately contributing to higher flavonoid accumulation. Importantly, the strong induction of CtC2H2-ZFPs observed at 24 h under ABA treatment suggests that these transcription factors may act upstream or in parallel with flavonoid biosynthesis genes [79]. C2H2-type ZFPs are known to participate in ABA-mediated transcriptional cascades, often influencing genes involved in metabolic adjustment and stress adaptation [80,81]. The temporal correlation between CtC2H2 upregulation and enhanced flavonoid biosynthesis implies that certain members of this family may modulate the expression of key enzymes in the flavonoid pathway, either directly through promoter binding or indirectly via ABA-responsive regulatory circuits. Such interactions would be consistent with the broader roles of C2H2-ZFPs in stress signaling, ROS management, and secondary metabolism reported in other plant species. Collectively, these findings highlight a coordinated ABA-driven mechanism in safflower, wherein CtC2H2-ZFPs and flavonoid biosynthetic genes jointly contribute to elevated flavonoid accumulation. Such dynamic responses emphasize the need for further investigation into these regulatory networks, especially considering their implications for metabolic engineering aimed at enhancing stress resilience in crops.

5. Conclusions

This study presents the first comprehensive genome-wide identification of C2H2 zinc-finger transcription factor family in safflower. The structural conservation and expression bias of candidate CtC2H2 genes uncovered distinct and tissue-specific expression modules under basal, abiotic stresses (cold, UV-B) and hormonal treatments (ABA, MeJA). The coordinated upregulation of specific CtC2H2 genes with key flavonoid pathway genes under ABA treatment suggests their potential role in regulating specialized metabolism. Collectively, these findings highlight the functional diversity of CtC2H2-ZFPs and provide valuable candidate genes for future functional studies aimed at enhancing stress resilience and modulating the production of valuable metabolites in safflower.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/cimb47121023/s1, Table S1: C2H2 Analysis of physicochemical properties; Table S2: Primer sequences; Figure S1: Conserved motif 1-15. 62 conserved motifs of the CtC2H2 gene, comprising 15 motifs (Motif 1 to Motif 15); Figure S2: Dissociation curve analysis for qRT- PCR primer specificity validation.The presence of a single, sharp peak for each primer pair indicates specific amplification of a single PCR product. The analysis was performed with three technical replicates for each primer set; one representative replicate is shown for clarity.

Author Contributions

Investigation, Writing—original draft and Visualization Y.C., A.W.U., and M.M., Conceptualization, N.A. and X.L.; Writing—review and editing, A.W.U. and N.A.; Formal analysis, Y.Z.; Funding acquisition and Supervision, X.L. and N.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by grants from the Science and Technology Development Project of Jilin Province (No. 20220204058YY).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are included in the article and its supplementary files (e.g., Table S1 for gene lists and primers). Materials and any additional datasets (such as raw qRT-PCR Ct values and representative HPLC chromatograms) are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The safflower genome sequence was deposited at NCBI under the bioproject accession number: PRJNA399628 and the transcriptome data are publicly available at NCBI under accession number: PRJNA909037.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the institutional support provided by Jilin Agricultural University and by the affiliated institutes of all co-authors. We are grateful for administrative and technical assistance that facilitated the experiments and data analyses. This work was supported by the funding sources listed in the Funding section.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alshareef, N.S.; AlSedairy, S.A.; Al-Harbi, L.N.; Alshammari, G.M.; Yahya, M.A. Carthamus tinctorius L. (Safflower) Flower Extract Attenuates Hepatic Injury and Steatosis in a Rat Model of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus via Nrf2-Dependent Hypoglycemic, Antioxidant, and Hypolipidemic Effects. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, C.; Fang, R.; Xu, Y.; Li, K.; Ai, T.; Wan, J.; Qin, Y.; Lyu, X.; Liu, H.; Qin, R.; et al. Safflower petal water-extract consumption reduces blood glucose via modulating hepatic gluconeogenesis and gut microbiota. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 123, 106615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchetti, T.; Morresi, C.; Bellachioma, L.; Ferretti, G. Antioxidant and Pro-Oxidant Properties of Carthamus tinctorius, Hydroxy Safflor Yellow A, and Safflor Yellow A. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Si, N.; Ma, Y.; Ge, D.; Yu, X.; Fan, A.; Wang, X.; Hu, J.; Wei, P.; Ma, L.; et al. Hydroxysafflor-Yellow A Induces Human Gastric Carcinoma BGC-823 Cell Apoptosis by Activating Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma (PPARγ). Med. Sci. Monit. 2018, 24, 803–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, N.; Liu, J.; Xu, T.; Noman, M.; Jameel, A.; Yao, N.; Dong, Y.; Wang, N.; Li, X.; Wang, F.; et al. Overexpression of a novel cytochrome P450 promotes flavonoid biosynthesis and osmotic stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Genes 2019, 10, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xian, B.; Wang, R.; Jiang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, J.; Huang, X.; Chen, J.; Wu, Q.; Chen, C.; Xi, Z.; et al. Comprehensive review of two groups of flavonoids in Carthamus tinctorius L. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 153, 113462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Xue, Y.-C. The Research Progress of Flavonoids in Plants. China Biotechnol. 2016, 36, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Lv, S.; Zhao, L.; Gao, T.; Yu, C.; Hu, J.; Ma, F. Advances in the study of the function and mechanism of the action of flavonoids in plants under environmental stresses. Planta 2023, 257, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agati, G.; Brunetti, C.; Di Ferdinando, M.; Ferrini, F.; Pollastri, S.; Tattini, M. Functional roles of flavonoids in photoprotection: New evidence, lessons from the past. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013, 72, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ahmad, N.; Chi, J.; Yu, L.; Hou, Y.; Wang, N.; Zhang, M.; Jin, L.; Yao, N.; Liu, X. CtDREB52 transcription factor regulates UV-B-induced flavonoid biosynthesis by transactivating CtMYB and CtF3′ H in Safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.). Plant Stress. 2024, 11, 100384. [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto, M.; Kumeda, S.; Komai, K. Insect antifeedant flavonoids from Gnaphalium affine D. Don. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 1888–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jan, R.; Khan, M.-A.; Asaf, S.; Lubna; Waqas, M.; Park, J.-R.; Asif, S.; Kim, N.; Lee, I.-J.; Kim, K.-M. Drought and UV Radiation Stress Tolerance in Rice Is Improved by Overaccumulation of Non-Enzymatic Antioxidant Flavonoids. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Ahmad, N.; Wang, N.; Jin, L.; Yao, N.; Liu, X. A Cinnamate 4-HYDROXYLASE1 from Safflower Promotes Flavonoids Accumulation and Stimulates Antioxidant Defense System in Arabidopsis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, H.; Yuan, L.; Luo, Y.; Jing, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhu, G. A freezing responsive UDP-glycosyltransferase improves potato freezing tolerance via modifying flavonoid metabolism. Hortic. Plant J. 2025, 11, 1595–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.; McLachlan, A.D.; Klug, A. Repetitive zinc-binding domains in the protein transcription factor IIIA from Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J. 1985, 4, 1609–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kielbowicz-Matuk, A. Involvement of plant C2H2-type zinc finger transcription factors in stress responses. Plant Sci. 2012, 185, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.M.; Shi, Y. The galvanization of biology: A growing appreciation for the roles of zinc. Science 1996, 271, 1081–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takatsuji, H. Zinc-finger proteins: The classical zinc finger emerges in contemporary plant science. Plant Mol. Biol. 1999, 39, 1073–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciftci-Yilmaz, S.; Morsy, M.R.; Song, L.; Coutu, A.; Krizek, B.A.; Lewis, M.W.; Warren, D.; Cushman, J.; Connolly, E.L.; Mittler, R. The EAR-motif of the Cys2/His2-type zinc finger protein Zat7 plays a key role in the defense response of Arabidopsis to salinity stress. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 9260–9268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittler, R.; Kim, Y.; Song, L.; Coutu, J.; Coutu, A.; Ciftci-Yilmaz, S.; Lee, H.; Stevenson, B.; Zhu, J.K. Gain- and loss-of-function mutations in Zat10 enhance the tolerance of plants to abiotic stress. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 6537–6542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, T.; Cao, J. Cys2/His2 Zinc-Finger Proteins in Transcriptional Regulation of Flower Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riechmann, J.L.; Heard, J.; Martin, G.; Reuber, L.; Jiang, C.; Keddie, J.; Adam, L.; Pineda, O.; Ratcliffe, O.J.; Samaha, R.R.; et al. Arabidopsis transcription factors: Genome-wide comparative analysis among eukaryotes. Science 2000, 290, 2105–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pu, J.; Li, M.; Mao, P.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, W.; Liu, Z. Genome-Wide Identification of the Q-type C2H2 Transcription Factor Family in Alfalfa (Medicago sativa) and Expression Analysis under Different Abiotic Stresses. Genes 2021, 12, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, L.; Li, N.; Zhang, X.; Pan, Y. Genome-wide identification of C2H2 zinc-finger genes and their expression patterns under heat stress in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). PeerJ 2019, 7, e7929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Hou, Q.; Yu, R.; Deng, H.; Shen, L.; Wang, Q.; Wen, X. Genome-wide analysis of C2H2 zinc finger family and their response to abiotic stresses in apple. Gene 2024, 904, 148164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Arora, R.; Ray, S.; Singh, A.K.; Singh, V.P.; Takatsuji, H.; Kapoor, S.; Tyagi, A.K. Genome-wide identification of C2H2 zinc-finger gene family in rice and their phylogeny and expression analysis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2007, 65, 467–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Mahanty, B.; Mishra, R.; Joshi, R.K. Genome wide identification and expression analysis of pepper C2H2 zinc finger transcription factors in response to anthracnose pathogen Colletotrichum truncatum. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Wang, L.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Huang, R.; Jiang, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, X.; He, Y.; He, Y.; et al. Genome-wide characterization of the C2H2 zinc-finger genes in Cucumis sativus and functional analyses of four CsZFPs in response to stresses. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Coulter, J.A.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Meng, J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the Q-type C2H2 gene family in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 153, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Liu, L.; Pan, Z.; Zhao, M.; Zhu, L.; Han, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, K.; Liu, S.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of the C2H2 zinc finger protein gene family and its response to salt stress in ginseng, Panax ginseng Meyer. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, F.; Zeng, L.; Xu, Y.; Jin, Q.; Wang, Y. Genome-wide identification of the Q-type C2H2 zinc finger protein gene family and expression analysis under abiotic stress in lotus (Nelumbo nucifera G.). BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, T.; Zhou, Y.; Qin, Z.; Li, A.; Wang, Q.; Li, Z.; Hou, F.; Zhang, L. Genome-wide identification of the C2H2 zinc finger gene family and expression analysis under salt stress in sweetpotato. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1301848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Q.; Niu, Z.; Chen, Q.; Gao, C.; Zhu, M.; Bai, J.; Liu, M.; He, L.; Liu, J.; Jiang, Y.; et al. The C2H2-type zinc finger transcription factor OSIC1 positively regulates stomatal closure under osmotic stress in poplar. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 943–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Wang, R.; Hu, X.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Xue, R.; Wu, M.; Li, H. Overexpression of wheat C2H2 zinc finger protein transcription factor TaZAT8-5B enhances drought tolerance and root growth in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta 2024, 260, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Li, C.Y.; An, J.P.; Wang, D.R.; Wang, X.; Wang, C.K.; You, C.X. The C2H2-type zinc finger transcription factor MdZAT10 negatively regulates drought tolerance in apple. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 167, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Lu, C.; Guo, J.; Qiao, Z.; Sui, N.; Qiu, N.; Wang, B. C2H2 Zinc Finger Proteins: Master Regulators of Abiotic Stress Responses in Plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 115, Correction in Front. Plant. Sci. 2020, 11, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Wang, X.; Ahmad, N.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Yao, N.; Jing, Y.; Du, L.; Li, X. The Carthamus tinctorius L. genome sequence provides insights into synthesis of unsaturated fatty acids. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eddy, S.R. Accelerated Profile HMM Searches. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2011, 7, e1002195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Johnson, J.; Grant, C.E.; Noble, W.S. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W39–W49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, G.E.; Hon, G.; Chandonia, J.M.; Brenner, S.E. WebLogo: A sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004, 14, 1188–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, B.; Gao, S.; Lercher, M.J.; Hu, S.; Chen, W.H. Evolview v3: A webserver for visualization, annotation, and management of phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W270–W275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K.; Shinozaki, K. Organization of cis-acting regulatory elements in osmotic- and cold-stress-responsive promoters. Trends Plant Sci. 2005, 10, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götz, S.; García-Gómez, J.M.; Terol, J.; Williams, T.D.; Nagaraj, S.H.; Nueda, M.J.; Robles, M.; Talon, M.; Dopazo, J.; Conesa, A. High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 3420–3435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; et al. Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ripley, B.D. The R project in statistical computing. Newsl. LTSN Maths Stats OR Netw. 2001, 1, 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ginestet, C. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A-Stat. Soc. 2011, 174, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Untergasser, A.; Cutcutache, I.; Koressaar, T.; Ye, J.; Faircloth, B.C.; Remm, M.; Rozen, S.G. Primer3—New capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustin, S.A.; Benes, V.; Garson, J.A.; Hellemans, J.; Huggett, J.; Kubista, M.; Mueller, R.; Nolan, T.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Shipley, G.L.; et al. The MIQE guidelines: Minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time PCR experiments. Clin. Chem. 2009, 55, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandesompele, J.; De Preter, K.; Pattyn, F.; Poppe, B.; Van Roy, N.; De Paepe, A.; Speleman, F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002, 3, Research0034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ge, H.; Ahmad, N.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, W.; Li, X.; Wang, N.; Wang, F. Genome-Wide Identification of MADS-box Family Genes in Safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.) and Functional Analysis of CtMADS24 during Flowering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortazavi, A.; Williams, B.A.; McCue, K.; Schaeffer, L.; Wold, B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat. Methods 2008, 5, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Paje, L.A.; Kim, M.J.; Jang, S.H.; Kim, J.T.; Lee, S. Validation of an optimized HPLC–UV method for the quantification of formononetin and biochanin A in Trifolium pratense extract. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2021, 64, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, P.; Park, K.J.; Obayashi, T.; Fujita, N.; Harada, H.; Adams-Collier, C.J.; Nakai, K. WoLF PSORT: Protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, W585–W587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.C.; Lee, S.H.; Cheong, Y.H.; Yoo, C.M.; Lee, S.I.; Chun, H.J.; Yun, D.J.; Hong, J.C.; Lee, S.Y.; Lim, C.O. A novel cold-inducible zinc finger protein from soybean, SCOF-1, enhances cold tolerance in transgenic plants. Plant J. 2001, 25, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, H.; Maruyama, K.; Sakuma, Y.; Meshi, T.; Iwabuchi, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Arabidopsis Cys2/His2-type zinc-finger proteins function as transcription repressors under drought, cold, and high-salinity stress conditions. Plant Physiol. 2004, 136, 2734–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.-C.; Liao, P.-M.; Kuo, W.-W.; Lin, T.-P. The Arabidopsis Ethylene Response Factor1 regulates abiotic stress-responsive gene expression by binding to different cis-acting elements in response to different stress signals. Plant Physiol. 2013, 162, 1566–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Liu, Z.; Li, S.; Qanmber, G.; Liu, L.; Guo, M.; Lu, L.; Ma, S.; Li, F.; Yang, Z. Genome-wide analysis of ZAT gene family revealed GhZAT6 regulates salt stress tolerance in G. hirsutum. Plant Sci. 2021, 312, 111055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Yang, S. ABA regulation of the cold stress response in plants. In Abscisic Acid: Metabolism, Transport and Signaling; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 337–363. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, S.N.A.; Azzeme, A.M.; Yousefi, K. Fine-tuning cold stress response through regulated cellular abundance and mechanistic actions of transcription factors. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 850216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Li, Y.; Cai, Q.; Li, X.; Sun, Y.; Yu, T.; Yang, J.; Zhang, J. Analysis of the C2H2 gene family in maize (Zea mays L.) under cold stress: Identification and expression. Life 2022, 13, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Ding, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Li, L.; Liu, L.; Zhou, H.; Yu, J.; Zheng, C.; Wu, H. A C2H2 zinc finger protein, OsZOS2-19, modulates ABA sensitivity and cold response in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 2025, 66, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; Fu, C.; Luo, X.; Wang, J.; Wan, X.; Huang, K.; Zhou, H.; Xie, G. Genome-wide analysis of the C2H2-type zinc finger protein family in rice (Oryza sativa) and the role of OsC2H2.35 in cold stress response. Plant Stress. 2025, 15, 100772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.-H.; Jiang, L.-L.; Ma, X.-F.; Xu, Z.-S.; Liu, M.-M.; Shan, S.-G.; Cheng, X.-G. A soybean C2H2-type zinc finger gene GmZF1 enhanced cold tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e109399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Sun, J.; Gong, D.; Kong, Y. The roles of Arabidopsis C1-2i subclass of C2H2-type zinc-finger transcription factors. Genes 2019, 10, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Ma, X.; Dai, M.; Chang, Y.; Wang, N.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; Yao, N.; Umar, A.W.; Liu, X. Unraveling Teosinte Branched1/Cycloidea/Proliferating Cell Factor Transcription Factors in Safflower: A Blueprint for Stress Resilience and Metabolic Regulation. Molecules 2025, 30, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favory, J.J.; Stec, A.; Gruber, H.; Rizzini, L.; Oravecz, A.; Funk, M.; Albert, A.; Cloix, C.; Jenkins, G.I.; Oakeley, E.J. Interaction of COP1 and UVR8 regulates UV-B-induced photomorphogenesis and stress acclimation in Arabidopsis. EMBO J. 2009, 28, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, D. BaZFP1, a C2H2 subfamily gene in desiccation-tolerant moss Bryum argenteum, positively regulates growth and development in Arabidopsis and mosses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugano, S.; Kaminaka, H.; Rybka, Z.; Catala, R.; Salinas, J.; Matsui, K.; Ohme-Takagi, M.; Takatsuji, H. Stress-responsive zinc finger gene ZPT2-3 plays a role in drought tolerance in petunia. Plant J. 2003, 36, 830–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieterse, C.M.; Van Pelt, J.A.; Van Wees, S.C.; Ton, J.; Léon-Kloosterziel, K.M.; Keurentjes, J.J.; Verhagen, B.W.; Knoester, M.; Van der Sluis, I.; Bakker, P.A. Rhizobacteria-mediated induced systemic resistance: Triggering, signalling and expression. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2001, 107, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicka, B.; Barbaś, P.; Bienia, B.; Skiba, D.; Pszczółkowski, P.; Krochmal-Marczak, B. Toward Enhanced Plant Immunity: Unveiling the Role of Brassinosteroids in Abiotic and Biotic Stress Response. Preprint 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Sun, D.; Wang, C.; Li, Y.; Guo, T. Expression of flavonoid biosynthesis genes and accumulation of flavonoid in wheat leaves in response to drought stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 80, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, C.; Sebastiani, F.; Tattini, M. ABA, flavonols, and the evolvability of land plants. Plant Sci. 2019, 280, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Tong, W.; Zhu, H.; Kong, W.; Peng, R.; Liu, Q.; Yao, Q. A novel Cys2/His2 zinc finger protein gene from sweetpotato, IbZFP1, is involved in salt and drought tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Planta 2016, 243, 783–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, I.; Batool, K.; Cui, D.-L.; Yang, Y.-Q.; Lu, Y.-H. Comprehensive genomic survey, structural classification and expression analysis of C2H2 zinc finger protein gene family in Brassica rapa L. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0216071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkins, R.D.; Tavva, V.S.; Palli, S.R.; Collins, G.B. Mutant and overexpression analysis of a C2H2 single zinc finger gene of Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 30, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, K.E.; Nishimura, N.; Hitomi, K.; Getzoff, E.D.; Schroeder, J.I. Early abscisic acid signal transduction mechanisms: Newly discovered components and newly emerging questions. Genes Dev. 2010, 24, 1695–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, T.; Liu, W.; Hu, Z.; Xiang, X.; Liu, T.; Xiong, X.; Cao, J. Molecular characterization and expression analysis reveal the roles of Cys2/His2 zinc-finger transcription factors during flower development of Brassica rapa subsp. chinensis. Plant Mol. Biol. 2020, 102, 123–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).