Effects of Nanomaterials on Crops

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Relevant Sections

2.1. Effects of NPs on the Growth and Development of Crops

2.1.1. The Effect on the Stage of Seed Germination

2.1.2. The Effect on the Vegetative Stage of Growth

2.1.3. Effect on Plant Reproductive Growth Stage

2.2. Nanomaterials to Plants: Transport, Oxidative Stress, and Photosynthesis

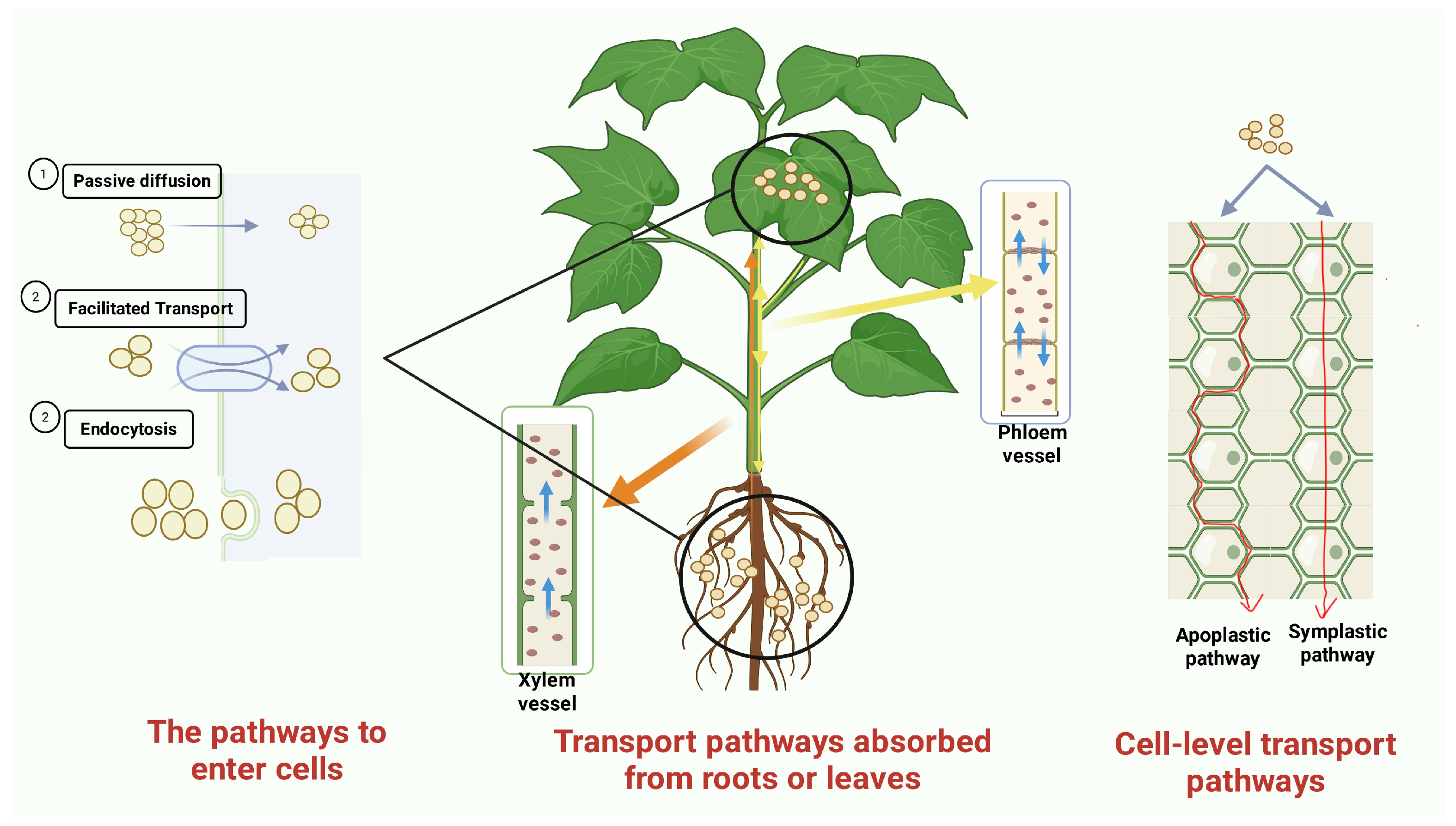

2.2.1. Transport of NPs in Plants

2.2.2. Effects of NP Delivery Route on Plant Response

2.2.3. Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant System Response

2.2.4. Photosynthesis

3. Potential Risks of NPs in Applications

3.1. Effects on the Soil Ecosystem

3.2. Transmission and Accumulation in the Food Chain

3.3. Potential Threats to Human Health

4. Conclusions

5. Future Directions

5.1. Mechanism Exploration: From Phenomenon to Essence

5.2. Problem-Oriented Approach: From Understanding to Control

5.3. Application Expansion: From Basic Research to Systemic Solutions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- David, A. How far will global population rise? Researchers can’t agree. Nature 2021, 597, 462–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvi, H.U.A.; Kabir, M.H.; Khatun, A.; Majumdar, B.C.; Islam, M.Z.; Jahan, N.; Binte Altaf, F.; Akter, A.; Gain, D.; Rahman, M.M. Rice and food security: Climate change implications and future prospects for nutritional security. Food Energy Secur. 2023, 12, e430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Danook, S.H.; Al-bonsrulah, H.A.Z.; Veeman, D.; Wang, F. A Recent and Systematic Review on Water Extraction from the Atmosphere for Arid Zones. Energies 2022, 15, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, D.L.; Hajek, O.L.; Smith, M.D.; Wilkins, K.; Slette, I.J.; Knapp, A.K. Compound hydroclimatic extremes in a semi-arid grassland: Drought, deluge, and the carbon cycle. Global Change Biol. 2022, 28, 2611–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, A.; Ahamed, T. Development of an autonomous navigation system for orchard spraying robots integrating a thermal camera and LiDAR using a deep learning algorithm under low- and no-light conditions. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 235, 110359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Hasan, M.K.; Ahammed, G.J.; Li, M.; Yin, H.; Zhou, J. Applications of Nanotechnology in Plant Growth and Crop Protection: A Review. Molecules 2019, 24, 2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-C.; Fei, D.; Min, L.; Min, Z.; Huan, Z.; Holger, H.; Zhou, D.-M. Effects of exposure pathways on the accumulation and phytotoxicity of silver nanoparticles in soybean and rice. Nanotoxicology 2017, 11, 699–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanpour, M.; Mohammadi, H.; Kariman, K. Nanosilicon-based recovery of barley (Hordeum vulgare) plants subjected to drought stress. Environ. Sci. Nano 2020, 7, 443–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hezaveh, T.A.; Pourakbar, L.; Rahmani, F.; Alipour, H. Interactive Effects of Salinity and ZnO Nanoparticles on Physiological and Molecular Parameters of Rapeseed (Brassica napus L.). Commun. Soil. Sci. Plant Anal. 2019, 50, 698–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koce, J.D.; Drobne, D.; Klančnik, K.; Makovec, D.; Novak, S.; Hočevar, M. Oxidative potential of ultraviolet-A irradiated or nonirradiated suspensions of titanium dioxide or silicon dioxide nanoparticles on Allium cepa roots. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2014, 33, 858–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, P.; Jayaprakasha, G.A.-O.; Crosby, K.M.; Jifon, J.L.; Patil, B.A.-O. Nanoparticle-Mediated Seed Priming Improves Germination, Growth, Yield, and Quality of Watermelons (Citrullus lanatus) at multi-locations in Texas. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, T.; Irfan, F.; Afsheen, S.; Zafar, M.; Naeem, S.; Raza, A. Synthesis and characterization of Ag–TiO2 nano-composites to study their effect on seed germination. Appl. Nanosci. 2021, 11, 2043–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, M.; Ali, S.; Ali, B.; Adrees, M.; Arshad, M.; Hussain, A.; Zia ur Rehman, M.; Waris, A.A. Zinc and iron oxide nanoparticles improved the plant growth and reduced the oxidative stress and cadmium concentration in wheat. Chemosphere 2019, 214, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannaujia, R.; Srivastava, C.M.; Prasad, V.; Singh, B.N.; Pandey, V. Phyllanthus emblica fruit extract stabilized biogenic silver nanoparticles as a growth promoter of wheat varieties by reducing ROS toxicity. PPB 2019, 142, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; He, J.; Xie, H.; Wang, W.; Bose, S.K.; Sun, Y.; Hu, J.; Yin, H. Effects of chitosan nanoparticles on seed germination and seedling growth of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 126, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijai Anand, K.; Anugraga, A.R.; Kannan, M.; Singaravelu, G.; Govindaraju, K. Bio-engineered magnesium oxide nanoparticles as nano-priming agent for enhancing seed germination and seedling vigour of green gram (Vigna radiata L.). Mater. Lett. 2020, 271, 127792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.; Meng, X.; Akram, N.A.; Zhu, F.; Hu, J.; Zhang, Z. Seed Priming with Fullerol Improves Seed Germination, Seedling Growth and Antioxidant Enzyme System of Two Winter Wheat Cultivars Under Drought Stress. Plants 2023, 12, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, D.D.; Anh, H.T.L.; Tam, L.T.; Show, P.L.; Leong, H.Y. Effects of nanoscale zerovalent cobalt on growth and photosynthetic parameters of soybean Glycine max (L.) Merr. DT26 at different stages. BMC Energy 2019, 1, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohatsu, M.Y.; Lange, C.N.; Pelegrino, M.T.; Pieretti, J.C.; Tortella, G.; Rubilar, O.; Batista, B.L.; Seabra, A.B.; de Jesus, T.A. Foliar spraying of biogenic CuO nanoparticles protects the defence system and photosynthetic pigments of lettuce (Lactuca sativa). J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 324, 129264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.; Cheng, L.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Deng, C.; Wang, Y.; Pan, J.; Shohag, M.J.I.; Xin, X.; He, Z.; et al. Bespoke ZnO NPs Synthesis Platform to Optimize Their Performance for Improving the Grain Yield, Zinc Biofortification, and Cd Mitigation in Wheat. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 716–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.; Feng, Y.; Ma, C.; Wang, C.; Chen, F.; Cao, X.; Wang, J.; White, J.C.; Wang, Z.; Xing, B. Molecular Mechanisms of Early Flowering in Tomatoes Induced by Manganese Ferrite (MnFe2O4) Nanomaterials. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 5636–5646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, F.; Cao, X.; Wang, J.; Yue, L.; Wang, Z. Cerium oxide nanomaterials improve cucumber flowering, fruit yield and quality: The rhizosphere effect. Environ. Sci. Nano 2023, 10, 2010–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.X.; Wang, C.X.; Cao, X.S.; Yue, L.; Chen, F.R.; Liu, X.F.; Wang, Z.; Xing, B. Selenium nanomaterials induce flower enlargement and improve the nutritional quality of cherry tomatoes: Pot and field experiments. Environ. Sci. Nano 2022, 9, 4190–4200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, M.K.Y.; Amin, M.A.-A.; Nowwar, A.I.; Hendy, M.H.; Salem, S.S. Green Synthesis of Selenium Nanoparticles from Cassia javanica Flowers Extract and Their Medical and Agricultural Applications. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.-J.; Liu, G.-Y.; Lin, Z.-H.; Sheng, B.; Chen, G.; Xu, X.-M.; Wang, J.-W.; Xu, D.-H. Research Progress on Nanoregulation of Vegetable Seed Germination and Its Mechanism. Biotechnol. Bull. 2025, 41, 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.; Zahoor, M.; Sher Khan, R.; Ikram, M.; Islam, N.U. The impact of silver nanoparticles on the growth of plants: The agriculture applications. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahakham, W.; Sarmah, A.K.; Maensiri, S.; Theerakulpisut, P. Nanopriming Technology for Enhancing Germination and Starch Metabolism of Aged Rice Seeds Using Phytosynthesized Silver Nanoparticles. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hojjat, S.S. The Effect of silver nanoparticle on lentil Seed Germination under drought stress. Agric. Food Sci. 2016, 5, 208–212. [Google Scholar]

- Almutairi, Z.M. Influence of Silver Nano-Particles on the Salt Resistance of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) During Germination. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2016, 18, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amritha, M.S.; Sridharan, K.; Puthur, J.T.; Dhankher, O.P. Priming with Nanoscale Materials for Boosting Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Crop Plants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 10017–10035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, D.; Afzal, S.; Singh, N.K. Nanopriming with Phytosynthesized Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles for Promoting Germination and Starch Metabolism in Rice Seeds. J. Biotechnol. 2021, 336, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, T.; Yadav, S.K.; Choudhary, R.; Rao, D.; Sushma, M.K.; Mandal, A.; Hussain, Z.; Minkina, T.; Rajput, V.D.; Yadav, S. Effect of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticle Based Seed Priming for Enhancing Seed Vigour and Physio-Biochemical Quality of Tomato Seedlings Under Salinity Stress. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 2024, 71, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagarcia, H.; Dervishi, E.; de Silva, K.; Biris, A.S.; Khodakovskaya, M.V. Surface Chemistry of Carbon Nanotubes Impacts the Growth and Expression of Water Channel Protein in Tomato Plants. Small 2012, 8, 2328–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.-L.; Li, J.; Wang, H.-C.; Zhang, C.-L.; Naeem, M.S. Fullerol Improves Seed Germination, Biomass Accumulation, Photosynthesis and Antioxidant System in Brassica napus L. Under Water Stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 129, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Pei, P.; Wang, C.; Sun, T.; Chang, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, S.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, X.; Huang, Q.; et al. Silver Nanoparticles Amplify Mercury Toxicity in Rice: Impacts on Germination, Growth, and Cellular Integrity. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 229, 110493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Tang, Y.; Hu, L.; Xu, J.; Zhang, X.; Dou, X.; Zhang, S.; Huang, L.; Wang, X. Growth and Physiology Effects of Seed Priming and Foliar Application of Zno Nanoparticles on Hibiscus syriacus L. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Hashmi, S.S.; Palma, J.M.; Corpas, F.J. Influence of Metallic, Metallic Oxide, and Organic Nanoparticles on Plant Physiology. Chemosphere 2022, 290, 133329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Vargas, E.R.; González-García, Y.; Pérez-Álvarez, M.; Cadenas-Pliego, G.; González-Morales, S.; Benavides-Mendoza, A.; Cabrera, R.I.; Juárez-Maldonado, A. Seed Priming with Carbon Nanomaterials to Modify the Germination, Growth, and Antioxidant Status of Tomato Seedlings. Agronomy 2020, 10, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, P.; Ikhtiari, R.; Fugetsu, B. Graphene phytotoxicity in the seedling stage of cabbage, tomato, red spinach, and lettuce. Carbon 2011, 49, 3907–3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calleja-Cabrera, J.; Boter, M.; Oate-Sánchez, L.; Pernas, M. Root Growth Adaptation to Climate Change in Crops. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Qi, J.; Liu, X.; Guo, L.; Zhang, H. Research on the Mechanisms of Phytohormone Signaling in Regulating Root Development. Plants 2024, 13, 3051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Chen, F.; Li, X.; Wang, C.; Cao, X.; Jiao, L.; Yue, L.; Wang, Z. Rhizosphere regulation with cerium oxide nanomaterials promoted carrot taproot thickening. Environ. Sci. Nano 2024, 11, 3359–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zou, Y.; Li, P.; Yuan, X. Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles Promote Root Growth by Interfering with Auxin Pathways in Arabidopsis thaliana. Phyton-Int. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 89, 883–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servin, A.D.; Castillo-Michel, H.; Hernandez-Viezcas, J.A.; Diaz, B.C.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. Synchrotron Micro-XRF and Micro-XANES Confirmation of the Uptake and Translocation of TiO2 Nanoparticles in Cucumber (Cucumis sativus) Plants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 7637–7643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Noguchi, K.; Ono, N.; Inoue, S.-I.; Terashima, I.; Kinoshita, T. Overexpression of plasma membrane H+-ATPase in guard cells promotes light-induced stomatal opening and enhances plant growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, S.; Trujillo-Reyes, J.; Hernandez-Viezcas, J.A.; White, J.C.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. Cerium Biomagnification in a Terrestrial Food Chain: Influence of Particle Size and Growth Stage. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 6782–6792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Xiao, H.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Hu, J. Uptake, transportation, and accumulation of C60 fullerene and heavy metal ions (Cd, Cu, and Pb) in rice plants grown in an agricultural soil. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 235, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzajani, F.; Askari, H.; Hamzelou, S.; Farzaneh, M.; Ghassempour, A. Effect of silver nanoparticles on Oryza sativa L. and its rhizosphere bacteria. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2013, 88, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hu, J.; Ma, C.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C.; Huang, J.; Xing, B. Uptake, translocation and physiological effects of magnetic iron oxide (γ-Fe2O3) nanoparticles in corn (Zea mays L.). Chemosphere 2016, 159, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamez, C.; Morelius, E.W.; Hernandez-Viezcas, J.A.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Gardea-Torresdey, J. Biochemical and physiological effects of copper compounds/nanoparticles on sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum). Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 649, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreslavski, V.D.; Shmarev, A.N.; Ivanov, A.A.; Zharmukhamedov, S.K.; Strokina, V.; Kosobryukhov, A.; Yu, M.; Allakhverdiev, S.I.; Shabala, S. Effects of iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4) and salinity on growth, photosynthesis, antioxidant activity and distribution of mineral elements in wheat (Triticum aestivum). Funct. Plant Biol. 2023, 50, 932–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Kang, Y.G.; Chang, Y.S.; Kim, J.H. Effects of Zerovalent Iron Nanoparticles on Photosynthesis and Biochemical Adaptation of Soil-Grown Arabidopsis thaliana. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, S.; Malik, A.; Khan, S.T. ZnO nanoparticles in combination with Zn biofertilizer improve wheat plant growth and grain Zn content without significantly changing the rhizospheric microbiome. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2023, 213, 105446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahani, S.; Saadatmand, S.; Mahmoodzadeh, H.; Khavari-Nejad, R.A. Effect of foliar application of cerium oxide nanoparticles on growth, photosynthetic pigments, electrolyte leakage, compatible osmolytes and antioxidant enzymes activities of Calendula officinalis L. Biologia 2019, 74, 1063–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landa, P. Positive effects of metallic nanoparticles on plants: Overview of involved mechanisms. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2021, 161, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Hu, S.; Huang, P.; Song, H.; Wang, K.; Ruan, J.; He, R.; Cui, D. Single Walled Carbon Nanotubes Exhibit Dual-Phase Regulation to Exposed Arabidopsis Mesophyll Cells. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2010, 6, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.-Y.; Lin, X.-J.; Liang, H.-M.; Wang, F.-F.; Chen, L.-Y. The Long Journey of Pollen Tube in the Pistil. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, H.; Wang, T.; Ren, H.; Zhang, Y. AtFH5-labeled secretory vesicles-dependent calcium oscillation drives exocytosis and stepwise bulge during pollen germination. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 113319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshihara, S.; Hirata, S.; Yamamoto, K.; Nakajima, Y.; Kurahashi, K.; Tokumoto, H. ZnO nanoparticles effect on pollen grain germination and pollen tube elongation. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2021, 145, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candotto Carniel, F.; Gorelli, D.; Flahaut, E.; Fortuna, L.; Del Casino, C.; Cai, G.; Nepi, M.; Prato, M.; Tretiach, M. Graphene oxide impairs the pollen performance of Nicotiana tabacum and Corylus avellana suggesting potential negative effects on the sexual reproduction of seed plants. Environ. Sci. Nano 2018, 5, 1608–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosa, W.F.A.; El-Shehawi, A.M.; Mackled, M.I.; Salem, M.Z.M.; Ghareeb, R.Y.; Hafez, E.E.; Behiry, S.I.; Abdelsalam, N.R. Productivity performance of peach trees, insecticidal and antibacterial bioactivities of leaf extracts as affected by nanofertilizers foliar application. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kole, C.; Kole, P.; Randunu, K.M.; Choudhary, P.; Podila, R.; Ke, P.C.; Rao, A.M.; Marcus, R.K. Nanobiotechnology can boost crop production and quality: First evidence from increased plant biomass, fruit yield and phytomedicine content in bitter melon (Momordica charantia). BMC Biotechnol. 2013, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, K.; Mu, J.; Tian, H.; Gao, D.; Zhou, H.; Guo, L.; Shao, X.; Geng, Y.; Zhang, Q. Zinc regulation of chlorophyll fluorescence and carbohydrate metabolism in saline-sodic stressed rice seedlings. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, R.; Chen, Z.; Cui, P.; Lu, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H. The Effect of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles for Enhancing Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Yield and Quality. Agriculture 2021, 11, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakić, I.; Radović, A.; Živković, B.; Radović, I.; Simin, N.; Živanović, N.; Čolić, S. Effect of nanocalcium foliar application on the growth, yield, and fruit quality of strawberry cv ‘Alba’. J. Plant Nutr. 2025, 48, 1695–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Choudhary, P.; Kumar, S.; Daima, H.K. Mechanistic approaches for crosstalk between nanomaterials and plants: Plant immunomodulation, defense mechanisms, stress resilience, toxicity, and perspectives. Environ. Sci. Nano 2024, 11, 2324–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nile, S.H.; Thiruvengadam, M.; Wang, Y.; Samynathan, R.; Shariati, M.A.; Rebezov, M.; Nile, A.; Sun, M.; Venkidasamy, B.; Xiao, J.; et al. Nano-priming as emerging seed priming technology for sustainable agriculture—Recent developments and future perspectives. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nongbet, A.; Mishra, A.K.; Mohanta, Y.K.; Mahanta, S.; Ray, M.K.; Khan, M.; Baek, K.-H.; Chakrabartty, I. Nanofertilizers: A Smart and Sustainable Attribute to Modern Agriculture. Plants 2022, 11, 2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Mehmood, A.; Khan, N. Uptake, Translocation, and Consequences of Nanomaterials on Plant Growth and Stress Adaptation. J. Nanomater. 2021, 2021, 6677616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraz, M.; Arif, Y.; Imtiaz, H.; Azam, A.; Alam, P.; Hayat, S. Cerium oxide nanoparticles: Biogenic synthesis, characterization, and effects of foliar application on photosynthetic and antioxidant performance on Brassica juncea L. Protoplasma 2025, 262, 1229–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fincheira, P.; Tortella, G.; Duran, N.; Seabra, A.B.; Rubilar, O. Current applications of nanotechnology to develop plant growth inducer agents as an innovation strategy. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2020, 40, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, T.; Chen, T.; Tan, H.; Zhang, S.; Wei, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, W.; Wang, L.; Wang, G. Endocytosis efficiency and targeting ability by the cooperation of nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 18553–18569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Angelis, G.; Badiali, C.; Chronopoulou, L.; Palocci, C.; Pasqua, G. Confocal Microscopy Investigations of Biopolymeric PLGA Nanoparticle Uptake in Arabidopsis thaliana L. Cultured Cells and Plantlet Roots. Plants 2023, 12, 2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Awan, S.A.; Rizwan, M.; Hassan, Z.U.; Akram, M.A.; Tariq, R.; Brestic, M.; Xie, W. Nanoparticle’s uptake and translocation mechanisms in plants via seed priming, foliar treatment, and root exposure: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 89823–89833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-de-Luque, A. Interaction of Nanomaterials with Plants: What Do We Need for Real Applications in Agriculture? Front. Environ. Sci. 2017, 5, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.R.; Adam, V.; Rizvi, T.F.; Zhang, B.; Ahamad, F.; Josko, I.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, M.; Mao, C. Nanoparticle-Plant Interactions: Two-Way Traffic. Small 2019, 15, 1901794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.T.; Christie, P.; Zhang, S.Z. Uptake, translocation, and transformation of metal-based nanoparticles in plants: Recent advances and methodological challenges. Environ. Sci. Nano 2019, 6, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Viezcas, J.A.; Castillo-Michel, H.; Andrews, J.C.; Cotte, M.; Rico, C.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Ge, Y.; Priester, J.H.; Holden, P.A.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. In Situ Synchrotron X-ray Fluorescence Mapping and Speciation of CeO2 and ZnO Nanoparticles in Soil Cultivated Soybean (Glycine max). ACS Nano 2013, 7, 1415–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.J.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Ren, M.H.; Varela-Ramirez, A.; Li, C.Q.; Hernandez-Viezcas, J.A.; Aguilera, R.J.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. Transport of Zn in a sandy loam soil treated with ZnO NPs and uptake by corn plants: Electron microprobe and confocal microscopy studies. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 184, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranjc, E.; Drobne, D. Nanomaterials in Plants: A Review of Hazard and Applications in the Agri-Food Sector. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butova, V.V.; Bauer, T.V.; Polyakov, V.A.; Minkina, T.M. Advances in nanoparticle and organic formulations for prolonged controlled release of auxins. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 201, 107808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Ashworth, V.; Kim, C.; Adeleye, A.S.; Rolshausen, P.; Roper, C.; White, J.; Jassby, D. Delivery, uptake, fate, and transport of engineered nanoparticles in plants: A critical review and data analysis. Environ. Sci. Nano 2019, 6, 2311–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhao, L.; Ma, H.; Zhang, H.; Guo, L.-H. Quantitative Analysis of Reactive Oxygen Species Photogenerated on Metal Oxide Nanoparticles and Their Bacteria Toxicity: The Role of Superoxide Radicals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 10137–10145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Niu, J.; Chen, Y. Mechanism of Photogenerated Reactive Oxygen Species and Correlation with the Antibacterial Properties of Engineered Metal-Oxide Nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 5164–5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarraf, M.; Vishwakarma, K.; Kumar, V.; Arif, N.; Das, S.; Johnson, R.; Janeeshma, E.; Puthur, J.T.; Aliniaeifard, S.; Chauhan, D.K.; et al. Metal/Metalloid-Based Nanomaterials for Plant Abiotic Stress Tolerance: An Overview of the Mechanisms. Plants 2022, 11, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marslin, G.; Sheeba, C.J.; Franklin, G. Nanoparticles Alter Secondary Metabolism in Plants via ROS Burst. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, S.; Jha, A.B.; Dubey, R.S.; Sharma, P. Nanowonders in agriculture: Unveiling the potential of nanoparticles to boost crop resilience to salinity stress. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 925, 171433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Xing, Y.; Luo, X.; Li, F.; Ren, M.; Liang, Y. Reactive Oxygen Species: A Crosslink Between Plant and Human Eukaryotic Cell Systems. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, A.; Mai, V.C.; Sadowska, K.; Labudda, M.; Jeandet, P.; Morkunas, I. Application of silver and selenium nanoparticles to enhance plant-defense response against biotic stressors. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2025, 47, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhaithloul, H.A.S.; Ali, B.; Alghanem, S.M.S.; Zulfiqar, F.; Al-Robai, S.A.; Ercisli, S.; Yong, J.W.H.; Moosa, A.; Irfan, E.; Ali, Q.; et al. Effect of green-synthesized copper oxide nanoparticles on growth, physiology, nutrient uptake, and cadmium accumulation in Triticum aestivum (L.). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 268, 115701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.M.; Jha, A.B.; Dubey, R.S.; Sharma, P. Nanoparticle-mediated mitigation of salt stress-induced oxidative damage in plants: Insights into signaling, gene expression, and antioxidant mechanisms. Environ. Sci. Nano 2025, 12, 2983–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Huang, T.; Zhou, C.; Wan, X.; He, X.; Miao, P.; Cheng, H.; Wang, X.; Yu, H.; Hu, M.; et al. Nano-priming with selenium nanoparticles reprograms seed germination, antioxidant defense, and phenylpropanoid metabolism to enhance Fusarium graminearum resistance in maize seedlings. J. Adv. Res. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Ghorbanpour, M.; Kariman, K. Manganese oxide nanoparticle-induced changes in growth, redox reactions and elicitation of antioxidant metabolites in deadly nightshade (Atropa belladonna L.). Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 126, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, H.; Wang, Y.; Ye, W.; Kong, X.; Yin, Z. Small particles, big effects: How nanoparticles can enhance plant growth in favorable and harsh conditions. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2024, 66, 1274–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maity, D.; Gupta, U.; Saha, S. Biosynthesized metal oxide nanoparticles for sustainable agriculture: Next-generation nanotechnology for crop production, protection and management. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 13950–13989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Riaz, S.; Davey, P.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, Y.; Dykes, G.F.; Zhou, F.; Hartwell, J.; Lawson, T.; Nixon, P.J. Producing fast and active Rubisco in tobacco to enhance photosynthesis. Plant Cell 2022, 35, 795–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshenour, K.; Hotto, A.; Michel, E.J.S.; Oh, Z.G.; Stern, D.B. Transgenic expression of Rubisco accumulation factor2 and Rubisco subunits increases photosynthesis and growth in maize. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 4024–4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ghanizadeh, H.; Han, Z.; Wang, Q.; Li, F.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, A. Metabolic profile and physiological mechanisms underlying the promoting effects of TiO2NPs on the photosynthesis and growth of tomato. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 322, 112394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, N.; Periole, X.; Roy, L.M.; Bot, Y.; Marrink, S.J.; Croce, R. The Role of Protein Conformational Changes in Tuning the Fluorescence State of Light-Harvesting Complexes. Biophys. J. 2016, 110, 313a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldo, J.P.; Wu, H.; Newkirk, G.M.; Kruss, S. Nanobiotechnology approaches for engineering smart plant sensors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Wang, X.; Hu, H.; Yang, Y.; Yu, X.; Chao, W.X.; Yu, M.; Ding, J.; Lin, Y.; Zhao, W.; et al. Closed-loop enhancement of plant photosynthesis via biomass-derived carbon dots in biohybrids. Commun. Mater. 2025, 6, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wu, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhuang, J.; Hu, C.; Liu, Y.; Lei, B.; Ma, L.; Wang, X. Enhanced Biological Photosynthetic Efficiency Using Light-Harvesting Engineering with Dual-Emissive Carbon Dots. Adv. Funct. 2018, 28, 1804004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mamun, M.R.; Hasan, M.R.; Ahommed, M.S.; Bacchu, M.S.; Ali, M.R.; Khan, M.Z.H. Nanofertilizers towards sustainable agriculture and environment. Environ. Technol. Inn. 2021, 23, 101658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahive, E.; Matzke, M.; Svendsen, C.; Spurgeon, D.J.; Pouran, H.; Zhang, H.; Lawlor, A.; Glória Pereira, M.; Lofts, S. Soil properties influence the toxicity and availability of Zn from ZnO nanoparticles to earthworms. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 319, 120907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, T.; Phogat, D.; Jakhar, N.; Shukla, V. Effectiveness of copper oxychloride coated with iron nanoparticles against earthworms. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyanka, K.P.; Kurian, A.; Balakrishna, K.M.; Varghese, T. Toxicological impact of TiO2 nanoparticles on Eudrilus euginiae. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2018, 12, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañas, J.E.; Qi, B.; Li, S.; Maul, J.D.; Cox, S.B.; Das, S.; Green, M.J. Acute and reproductive toxicity of nano-sized metal oxides (ZnO and TiO2) to earthworms (Eisenia fetida). J. Environ. Monit. 2011, 13, 3351–3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, M.L.; Oliveira Filho, L.C.I.d.; Nogueira, P.; Ogliari, A.J.; Fiori, M.A.; Baretta, D.; Baretta, C.R.D.M. Influence of ZnO Nanoparticles and a Non-Nano ZnO on Survival and Reproduction of Earthworm and Springtail in Tropical Natural Soil. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo 2019, 43, e0180133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duo, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, S. Individual and histopathological responses of the earthworm (Eisenia fetida) to graphene oxide exposure. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 229, 113076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoults-Wilson, W.A.; Reinsch, B.C.; Tsyusko, O.V.; Bertsch, P.M.; Lowry, G.V.; Unrine, J.M. Role of Particle Size and Soil Type in Toxicity of Silver Nanoparticles to Earthworms. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2011, 75, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, M.; Skiba, E.; Wolf, W.M. Root-Applied Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles and Their Specific Effects on Plants: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahle, J.T.; Arai, Y. Environmental Geochemistry of Cerium: Applications and Toxicology of Cerium Oxide Nanoparticles. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 1253–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Hu, J.; Yang, J. Light-induced ZnO/Ag/rGO bactericidal photocatalyst with synergistic effect of sustained release of silver ions and enhanced reactive oxygen species. Chin. J. Catal. 2019, 40, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köser, J.; Engelke, M.; Hoppe, M.; Nogowski, A.; Filser, J.; Thöming, J. Predictability of silver nanoparticle speciation and toxicity in ecotoxicological media. Environ. Sci. Nano 2017, 4, 1470–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundschuh, M.; Seitz, F.; Rosenfeldt, R.R.; Schulz, R. Effects of nanoparticles in fresh waters: Risks, mechanisms and interactions. Freshw. Biol. 2016, 61, 2185–2196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Z.; Niu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Crittenden, J.C. Enhanced bioaccumulation of cadmium in carp in the presence of titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Chemosphere 2007, 67, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwab, F.; Bucheli, T.D.; Camenzuli, L.; Magrez, A.; Knauer, K.; Sigg, L.; Nowack, B. Diuron Sorbed to Carbon Nanotubes Exhibits Enhanced Toxicity to Chlorella vulgaris. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 7012–7019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brausch, K.A.; Anderson, T.A.; Smith, P.N.; Maul, J.D. Effects of functionalized fullerenes on bifenthrin and tribufos toxicity to Daphnia magna: Survival, reproduction, and growth rate. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010, 29, 2600–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundschuh, M.; Filser, J.; Lüderwald, S.; McKee, M.S.; Metreveli, G.; Schaumann, G.E.; Schulz, R.; Wagner, S. Nanoparticles in the environment: Where do we come from, where do we go to? Environ. Sci. Eur. 2018, 30, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiede, K.; Hanssen, S.F.; Westerhoff, P.; Fern, G.J.; Hankin, S.M.; Aitken, R.J.; Chaudhry, Q.; Boxall, A.B.A. How important is drinking water exposure for the risks of engineered nanoparticles to consumers? Nanotoxicology 2016, 10, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judy, J.D.; Unrine, J.M.; Bertsch, P.M. Evidence for Biomagnification of Gold Nanoparticles within a Terrestrial Food Chain. Environ. Sci. Chno. 2011, 45, 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Feng, S.; Zhang, X.X.; Xi, Y.L.; Xiang, X.L. Bioaccumulation and biomagnification effects of nano-TiO2 in the aquatic food chain. Ecotoxicology 2022, 31, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.X.; He, E.; Peijnenburg, W.; Jiang, X.F.; Qiu, H. Differential Leaf-to-Root Movement, Trophic Transfer, and Tissue-Specific Biodistribution of Metal-Based and Polymer-Based Nanoparticles When Present Singly and in Mixture. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 21025–21036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, F.; Yuan, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xing, B. Trophic transfer of nanomaterials and their effects on high-trophic-level predators. NanoImpact 2023, 32, 100489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-L.; Lee, Y.-H.; Chiu, I.J.; Lin, Y.-F.; Chiu, H.-W. Potent Impact of Plastic Nanomaterials and Micromaterials on the Food Chain and Human Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, M.; Bandyopadhyay, M.; Mukherjee, A. Genotoxicity of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles at two trophic levels: Plant and human lymphocytes. Chemosphere 2010, 81, 1253–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lojk, J.; Repas, J.; Veranič, P.; Bregar, V.B.; Pavlin, M. Toxicity mechanisms of selected engineered nanoparticles on human neural cells in vitro. Toxicology 2020, 432, 152364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerin, H.; Nagaraj, K.; Kamalesu, S. Review on aquatic toxicity of metal oxide nanoparticles. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nanomaterial | Concentration | Size (nm) | Target Plant Species | Treatment Methods | Action Period | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag NPs | 10 mg/L, 80 mg/L, | 28.32; 29 | Watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) | soaking treatment | seed germination stage | Improve the seed germination rate and soluble sugar content of seedlings | Acharya et al. (2020); [11] |

| Ag NPs; Ti NPs | 5 mg/mL; 100 mL; 10 mg/100 mL; 15 mg/100 mL | 39 21 | Corn (Zea mays); Rice (Oryza sativa) | soaking treatment | seed germination stage | Significantly increased the germination rate of rice and corn seeds. | Iqbal et al. (2021); [12] |

| ZnO NPs; Fe NPs | 20–30 | Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) | soaking treatment | vegetative stage | Increasing plant height and dry weight had a positive effect on the photosynthesis of wheat. | Rizwan et al. (2019); [13] | |

| Ag NPS | 10 mg/L | 10–35 | Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) | vegetative stage | The early growth of seedlings was effectively promoted by reducing ROS toxicity. | Kannaujia et al. (2019); [14] | |

| CSNPs | 5 μg/ml | 80–200 | Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) | irrigation treatment | vegetative stage | Promote the increase in IAA concentration in wheat buds and roots, thereby promoting the growth of wheat seedlings. | Li et et al. (2019); [15] |

| MgO NPs | 100 mg/L | 12 | green gram (Vigna radiata L.) | soaking treatment | seed germination stage | Improve seed germination rate and seedling vigor. | Anand et al. (2020); [16] |

| Fullerol | 50 mg/L | Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) | soaking treatment | seed germination stage | Improving seed germination under drought stress. | Kong et al. (2023); [17] | |

| Nanoscale zero-valentcobalt (NZVC) | 0.17 mg/kg | 40–60 | Soybean (Glycine max L.) | soaking treatment | vegetative stage | Improve growth parameters such as plant height, leaf area, and stem and leaf dry weight; it has a positive effect on the growth of plants in the vegetative growth period. | Hong et al. (2019); [18] |

| CuO NPs | 20 mg per plant | Lettuce (Lactuca sativa) | foliage spray | vegetative stage | Enhance non-enzymatic antioxidant activity, improve plant stress tolerance, and increase plant photosynthetic pigment content. | Kohatsu et al. (2021); [19] | |

| ZnO NPs | 100 mg/L | Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) | foliage spray | reproduction stage | Increase wheat grain, increase yield, and significantly increase the nutrient content of wheat seeds. | Lian et al. (2024); [20] | |

| MnFe2O4 NMs | 10 mg/L | Tomato (Solanum tuberosum) | foliage spray | reproduction stage | It increased pollen activity and egg size, and improved plant seed setting rate. | Yue et al. (2022); [21] | |

| CeO2 NMs | 10 mg/kg | Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) | irrigation | reproduction stage | It can induce early flowering and improve fruit yield and quality. | Feng et al. (2023); [22] | |

| Se Engineered Nanomaterials (ENMs) | 75 μg/kg | Cherry tomato (Solanum lycopersicum var. cerasiforme) | reproduction stage | Improve the yield and quality of tomatoes | Cheng et al. (2022); [23] | ||

| Se NPs | 50, 100 and 200 mg/mL | Faba Bean (Vicia faba) | soaking treatment | reproduction stage | The dry weight per bean, the number of seeds per plant, and the number of pods per plant increased. | Soliman et al. (2024); [24] |

| Nanomaterial | Concentration | Plant Species | Effect on Pollen/Pollen Tube | Effect on Reproduction | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO NPs | 10–100 mg/L | Lily (Lilium spp.) | Inhibited pollen germination and tube elongation; no effect on pollen viability. | Potential negative impact on fertilization. | Yoshihara et al., 2021; [59] |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) | 50–200 mg/L | Nicotiana tabacum, Corylus avellana | Significant inhibition of pollen germination and tube growth; abnormal tube morphology. | Impaired sexual reproduction. | Candotto Carniel et al., 2018; [60] |

| Ag NPs | 10–50 mg/L (foliar spray) | Peach (Prunus persica) | Increased pollen grain number and viability; no malformation. | Enhanced pollination and fertilization efficiency. | Mosa et al., 2021; [61] |

| MnFe2O4 NMs | 10 mg/L (foliar spray) | Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) | Increased pollen activity. | Improved seed setting rate. | Yue et al., 2022; [21] |

| CeO2 NPs | 10 mg/kg (soil) | Cucumber (Cucumis sativus) | – | Induced early flowering and improved fruit yield and quality. | Feng et al., 2023; [22] |

| Se ENM | 75 μg/kg (soil) | Cherry tomato (Solanum lycopersicum var. cerasiforme) | – | Increased flower size, improved fruit yield and nutritional quality. | Cheng et al., 2022; [23] |

| Fullerol (C60(OH)20) | 50 mg/L (seed priming) | Bitter melon (Momordica charantia) | – | Increased fruit number (59%), individual fruit weight (70%), total yield (128%), and bioactive compounds. | Kole et al., 2013; [62] |

| Nanomaterial | Concentration | Earthworm Species | Exposure Duration | Key Effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnO NPs | 100–1000 mg/kg | Eisenia fetida | 28 days | Reproductive toxicity; damaged gonadal tissues; abnormal gene expression | Cañas et al. (2011); [17] |

| TiO2 NPs | 1000–2000 mg/kg | Eudrilus euginiae | 14 days | Reduced survival; growth inhibition; oxidative stress | Priyanka et al. (2018); [106] |

| CNTs | 500–1000 mg/kg | Eisenia fetida | 28 days | Impaired reproduction; histopathological damage to body wall | Duo et al. (2022); [109] |

| Graphene Oxide | 100–500 mg/kg | Eisenia fetida | 14 days | Reduced reproductive output; oxidative damage; inflammation response | Duo et al. (2022); [109] |

| Ag NPs | 10–100 mg/kg | Eisenia fetida | 14 days | Mortality at high doses; reduced growth and reproduction | Shoults-Wilson et al. (2011); [110] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, X.; Xu, H.; Li, W.; Chang, X.; Jiang, X.; Liu, X.; Kong, M. Effects of Nanomaterials on Crops. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 1024. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121024

Yang X, Xu H, Li W, Chang X, Jiang X, Liu X, Kong M. Effects of Nanomaterials on Crops. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2025; 47(12):1024. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121024

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Xiaofang, Huilian Xu, Wenrui Li, Xianchao Chang, Xiaohan Jiang, Xiaoyong Liu, and Mengmeng Kong. 2025. "Effects of Nanomaterials on Crops" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 47, no. 12: 1024. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121024

APA StyleYang, X., Xu, H., Li, W., Chang, X., Jiang, X., Liu, X., & Kong, M. (2025). Effects of Nanomaterials on Crops. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 47(12), 1024. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121024