Modulation of Moisturizing and Barrier Related Molecular Markers by Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Leuconostoc mesenteroides DB-21 Isolated from Camellia japonica Flower

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Incubation of Leuconostoc mesenteroides DB-21

2.2. Isolation of LEVs

2.3. Characterization and Morphology of LEVs

2.4. Preparation of LEVs Samples for Protein Identification

2.5. LC–MS/MS Conditions for Proteomics Analysis

2.6. Protein Identification via Database Search

2.7. Cytotoxicity Assessment of LEVs by WST-1 Assay

2.8. Analysis of LEVs on Skin Barrier Regulation via Real-Time PCR and ELISA

2.9. Total RNA Extraction and mRNA Expression Analysis with Real-Time PCR

2.10. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

2.11. 3D Culture Model for Skin Barrier Improvement by LEVs

2.12. Immunofluorescence Staining

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

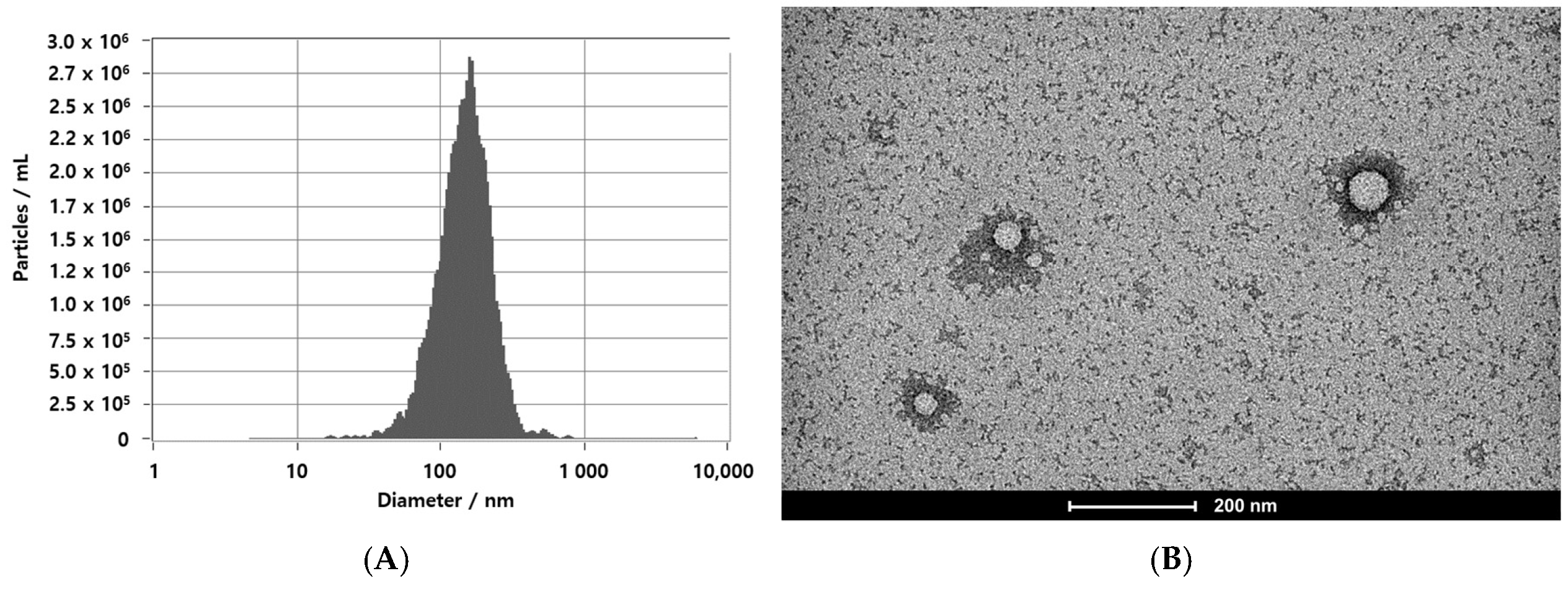

3.1. EVs Secretion by Leuconostoc mesenteroides

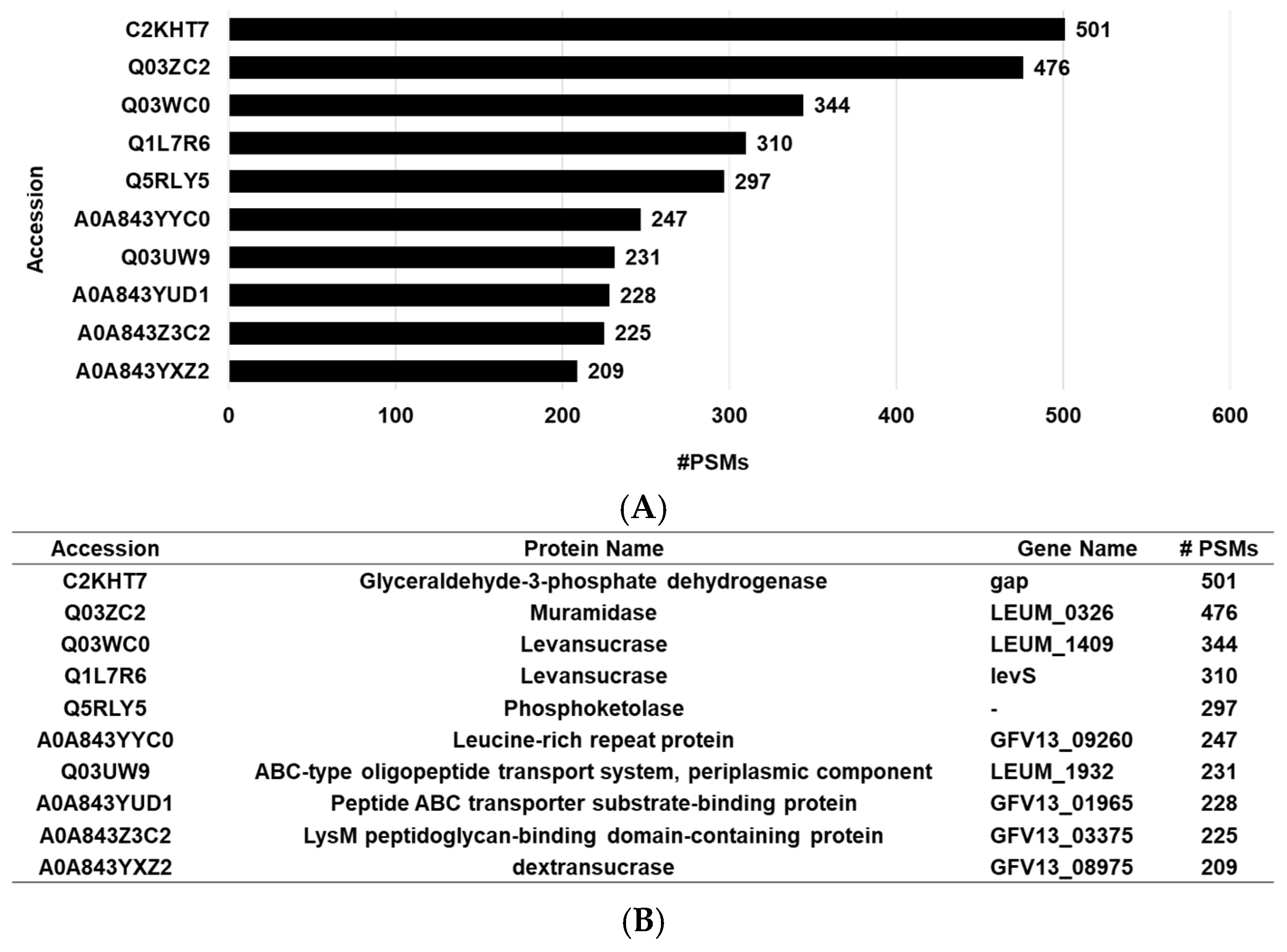

3.2. Proteomic Analysis of LEVs

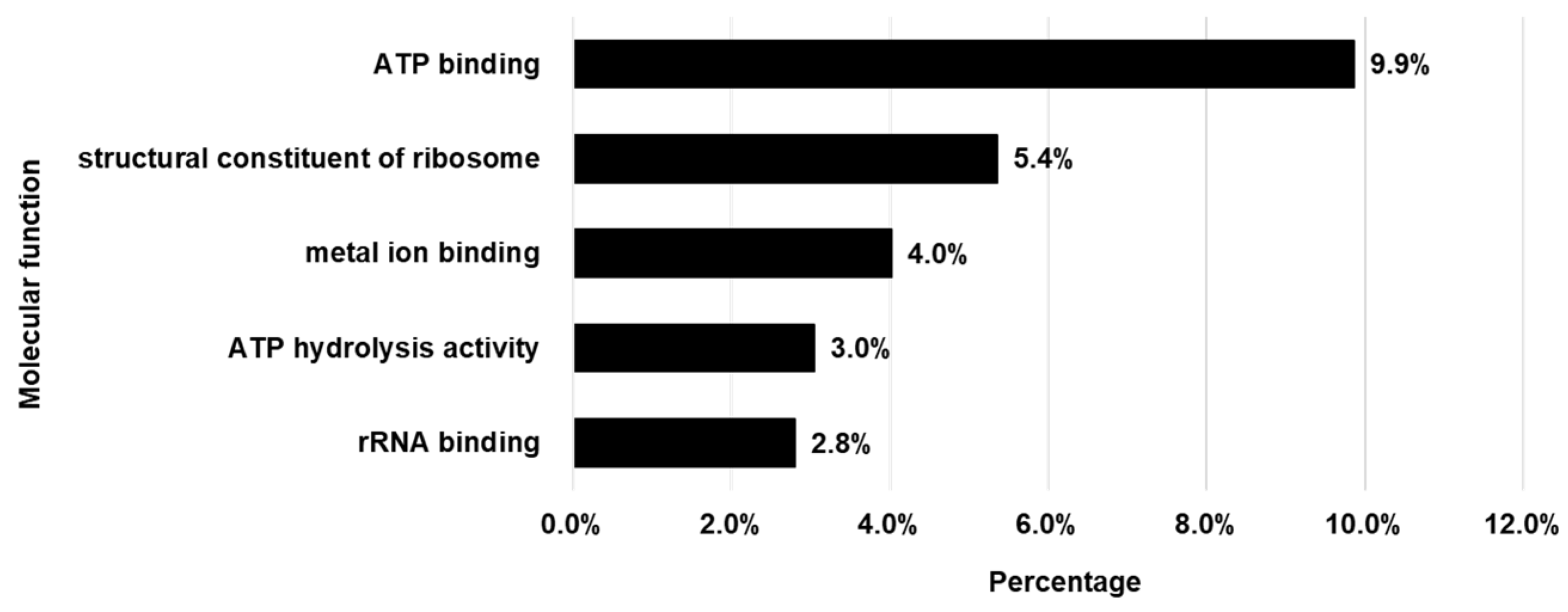

3.3. Gene Ontology (GO) Analysis of Proteins in LEVs

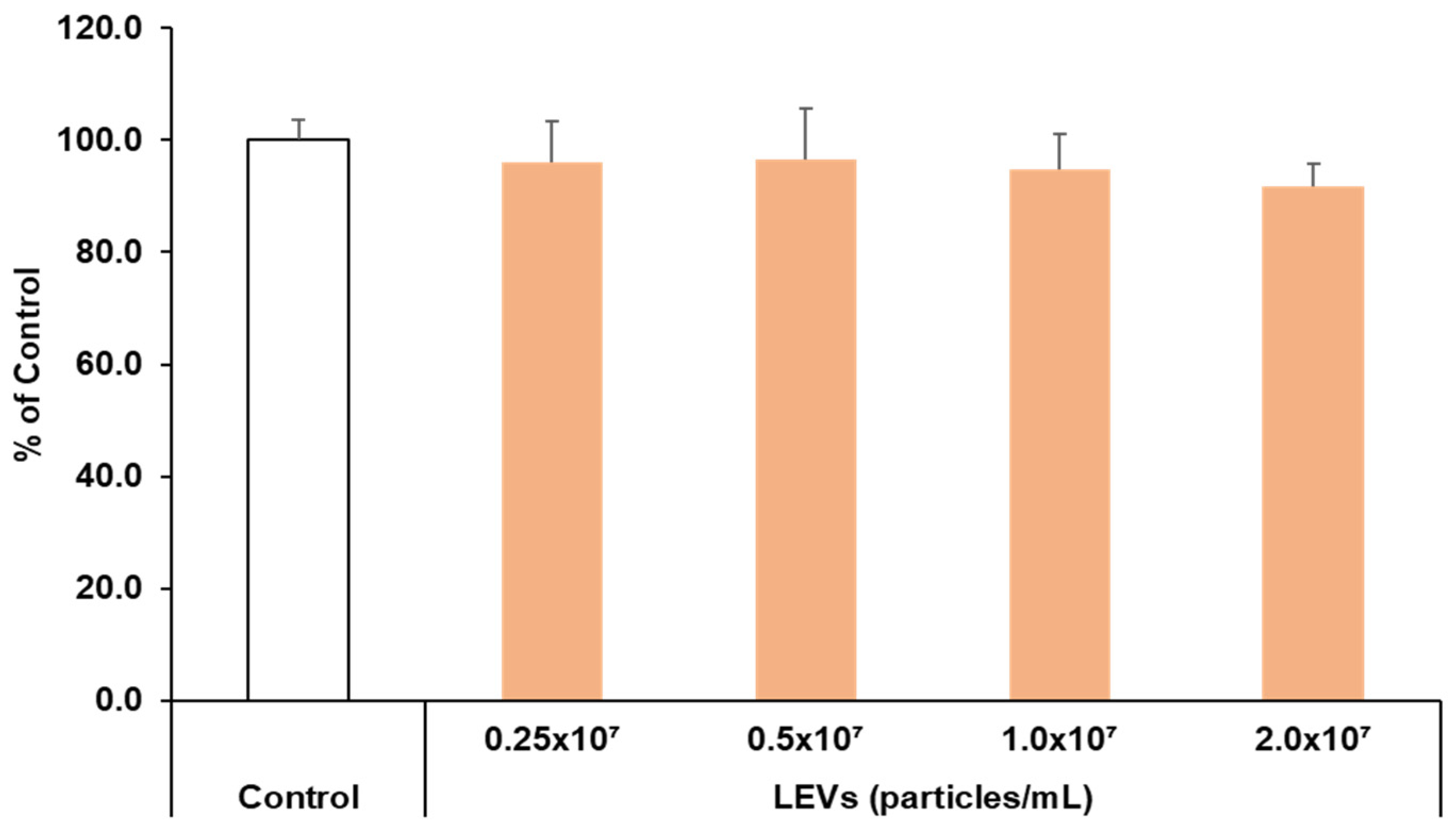

3.4. Cell Viability

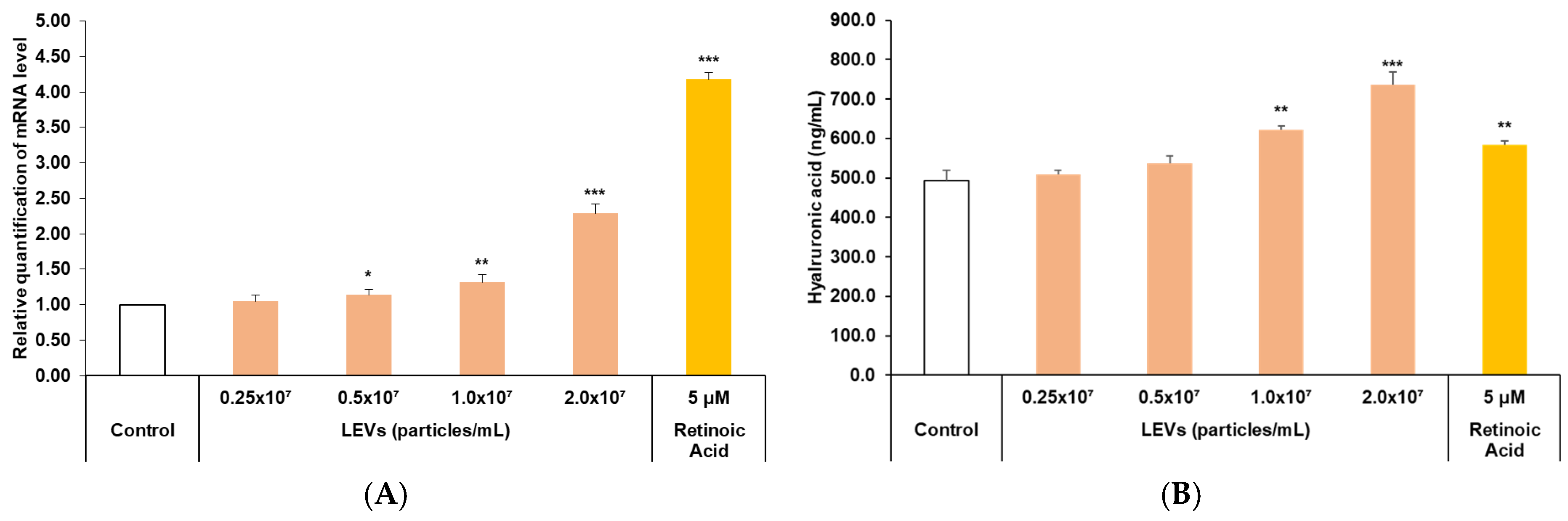

3.5. Skin Barrier Moisturizing Factor Analysis

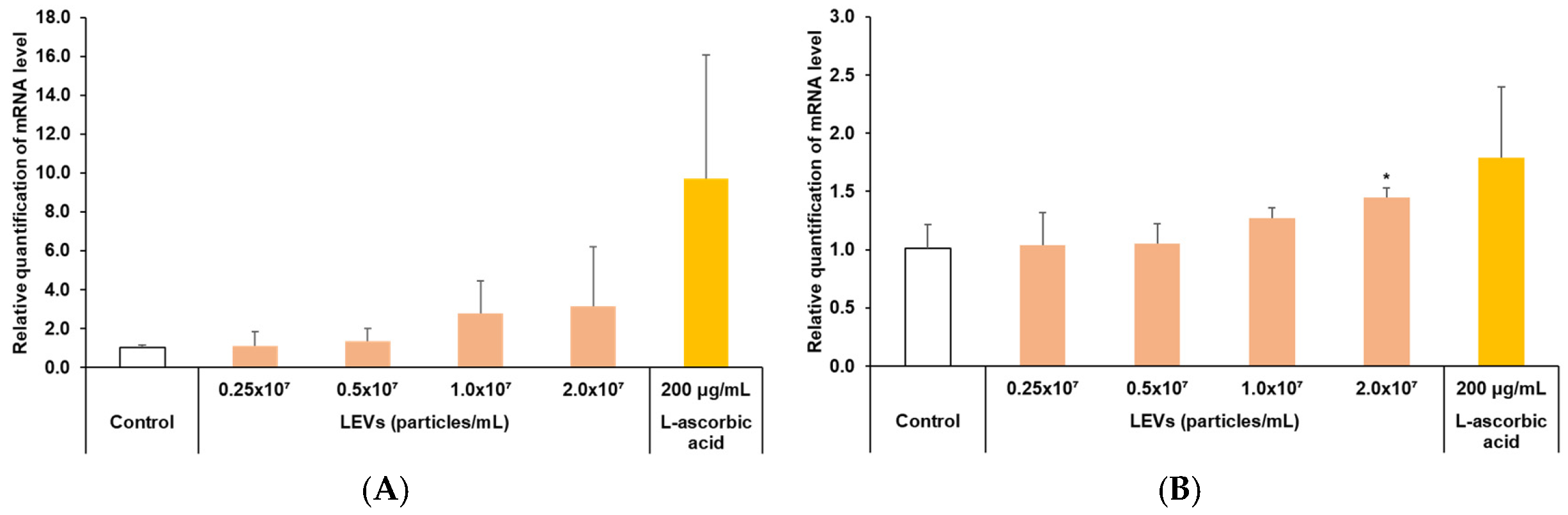

3.6. Improvement of Skin Barrier Function

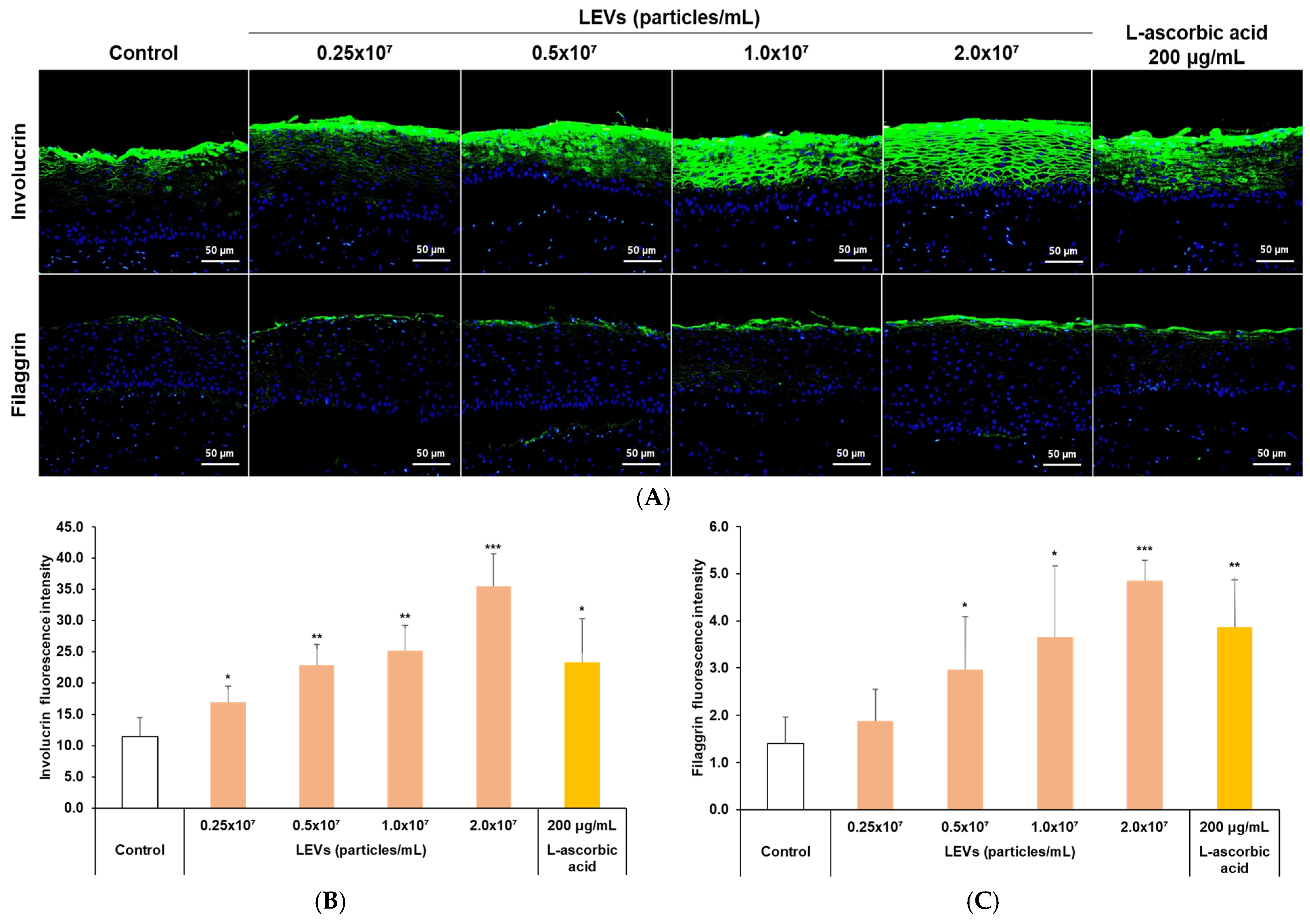

3.7. Expression of Skin Barrier Factors in a 3D Skin Model

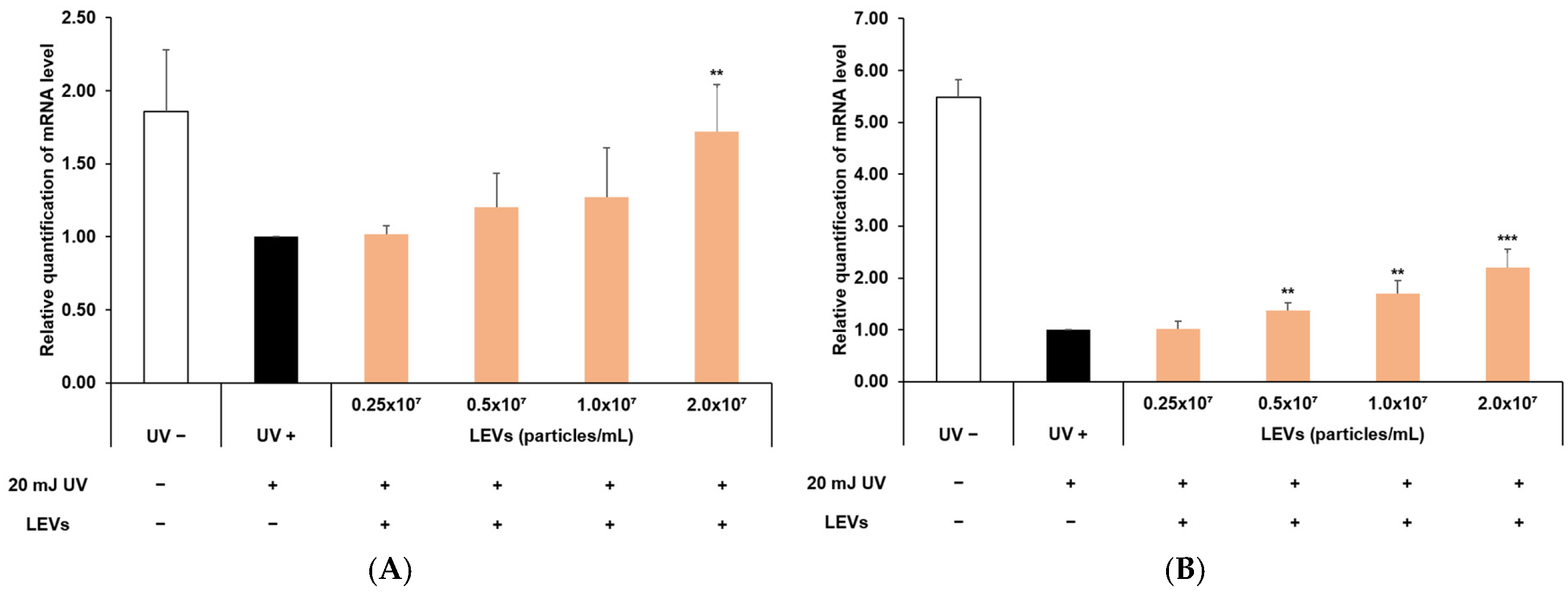

3.8. Protection of Skin Barrier Function

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Skotland, T.; Hessvik, N.P.; Sandvig, K.; Llorente, A. Exosomal lipid composition and the role of ether lipids and phosphoinositides in exosome biology. J. Lipid Res. 2019, 60, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, D.K.; Fenix, A.M.; Franklin, J.L.; Higginbotham, J.N.; Zhang, Q.; Zimmerman, L.J.; Liebler, D.C.; Ping, J.; Liu, Q.; Evans, R.; et al. Reassessment of Exosome Composition. Cell 2019, 177, 428–445 e418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trams, E.G.; Lauter, C.J.; Salem, N., Jr.; Heine, U. Exfoliation of membrane ecto-enzymes in the form of micro-vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1981, 645, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.T.; Johnstone, R.M. Fate of the transferrin receptor during maturation of sheep reticulocytes in vitro: Selective externalization of the receptor. Cell 1983, 33, 967–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, B.T.; Teng, K.; Wu, C.; Adam, M.; Johnstone, R.M. Electron microscopic evidence for externalization of the transferrin receptor in vesicular form in sheep reticulocytes. J. Cell Biol. 1985, 101, 942–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnstone, R.M.; Adam, M.; Hammond, J.R.; Orr, L.; Turbide, C. Vesicle formation during reticulocyte maturation. Association of plasma membrane activities with released vesicles (exosomes). J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262, 9412–9420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D.G.; Work, E. An extracellular glycolipid produced by Escherichia coli grown under lysine-limiting conditions. Biochem. J. 1965, 96, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knox, K.W.; Vesk, M.; Work, E. Relation between excreted lipopolysaccharide complexes and surface structures of a lysine-limited culture of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1966, 92, 1206–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Work, E.; Knox, K.W.; Vesk, M. The chemistry and electron microscopy of an extracellular lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia coli. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1966, 133, 438–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwechheimer, C.; Kuehn, M.J. Outer-membrane vesicles from Gram-negative bacteria: Biogenesis and functions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.Y.; Choi, D.Y.; Kim, D.K.; Kim, J.W.; Park, J.O.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.H.; Desiderio, D.M.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, K.P.; et al. Gram-positive bacteria produce membrane vesicles: Proteomics-based characterization of Staphylococcus aureus-derived membrane vesicles. Proteomics 2009, 9, 5425–5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costerton, J.W.; Ingram, J.M.; Cheng, K.J. Structure and function of the cell envelope of gram-negative bacteria. Bacteriol. Rev. 1974, 38, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, P.M.; Steinhoff, M. “Outside-to-inside” (and now back to “outside”) pathogenic mechanisms in atopic dermatitis. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2008, 128, 1067–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolarsick, P.A.J.; Kolarsick, M.A.; Goodwin, C. Anatomy and Physiology of the Skin. J. Dermatol. Nurses’ Assoc. 2011, 3, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proksch, E.; Brandner, J.M.; Jensen, J.M. The skin: An indispensable barrier. Exp. Dermatol. 2008, 17, 1063–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, G.J.; Kang, S.; Varani, J.; Bata-Csorgo, Z.; Wan, Y.; Datta, S.; Voorhees, J.J. Mechanisms of photoaging and chronological skin aging. Arch. Dermatol. 2002, 138, 1462–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, T.; Qin, Z.; Xia, W.; Shao, Y.; Voorhees, J.J.; Fisher, G.J. Matrix-degrading metalloproteinases in photoaging. J. Investig. Dermatol. Symp. Proc. 2009, 14, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, M.R. Ultraviolet radiation and skin cancer: Molecular mechanisms. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2005, 32, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karadeniz, F.; Oh, J.H.; Kim, H.R.; Ko, J.; Kong, C.S. Camellioside A, isolated from Camellia japonica flowers, attenuates UVA-induced production of MMP-1 in HaCaT keratinocytes via suppression of MAPK activation. Exp. Ther. Med. 2021, 21, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, S.Y.; Jung, J.Y.; Yang, J.K. Camellia japonica Essential Oil Inhibits alpha-MSH-Induced Melanin Production and Tyrosinase Activity in B16F10 Melanoma Cells. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 6328767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Choi, J.H.; Cui, L.; Li, Y.; Yang, J.M.; Yun, J.J.; Jung, J.E.; Choi, W.; Yoon, K.C. Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidative Effects of Camellia japonica on Human Corneal Epithelial Cells and Experimental Dry Eye: In Vivo and In Vitro Study. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2017, 58, 1196–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, C.; Rahman, M.H.; Pham, T.T.; Kim, C.S.; Bajgai, J.; Lee, K.J. Protective Effect of Camellia japonica Extract on 2,4-Dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB)-Induced Atopic Dermatitis in an SKH-1 Mouse Model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, A.; Baek, J.; Seo, M.; Kim, K.Y.; Kim, S.; Kwak, W.; Lee, J.; Kwak, J.; Yoon, W.J.; Kim, W.; et al. Atopic dermatitis-alleviating effects of lactiplantibacillus plantarum LRCC5195 paraprobiotics through microbiome modulation and safety assessment via genomic characterization and in vitro analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 30545, Erratum in Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 33713. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Han, S.Y.; Lee, J.; Kim, N.R.; Lee, B.R.; Kim, H.; Kwon, M.; Ahn, K.; Noh, Y.; Kim, S.J.; et al. Bifidobacterium longum and Galactooligosaccharide Improve Skin Barrier Dysfunction and Atopic Dermatitis-like Skin. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2022, 14, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bi, J.; Huang, J.; Tang, Y.; Du, S.; Li, P. Exosome: A Review of Its Classification, Isolation Techniques, Storage, Diagnostic and Targeted Therapy Applications. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 6917–6934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, Y.H.; Kim, J.W.; Kim, N.; Kim, H.S.; Jang, J.H.; Bae, J.T.; Kim, W. Lactobacillus brevis-Derived Exosomes Enhance Skin Barrier Integrity by Upregulating Key Barrier-Related Proteins. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2025, 18, 1151–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandi, J.; Cheri, S.; Manfredi, M.; Di Carlo, C.; Vita Vanella, V.; Federici, F.; Bombiero, E.; Bazaj, A.; Rizzi, E.; Manna, L.; et al. Exploring the wound healing, anti-inflammatory, anti-pathogenic and proteomic effects of lactic acid bacteria on keratinocytes. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367, eaau6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Park, J.Y. Potential of gamma-Aminobutyric Acid-Producing Leuconostoc mesenteroides Strains Isolated from Kimchi as a Starter for High-gamma-Aminobutyric Acid Kimchi Fermentation. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2023, 28, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruppitsch, W.; Nisic, A.; Hyden, P.; Cabal, A.; Sucher, J.; Stoger, A.; Allerberger, F.; Martinovic, A. Genetic Diversity of Leuconostoc mesenteroides Isolates from Traditional Montenegrin Brine Cheese. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schifano, E.; Tomassini, A.; Preziosi, A.; Montes, J.; Aureli, W.; Mancini, P.; Miccheli, A.; Uccelletti, D. Leuconostoc mesenteroides Strains Isolated from Carrots Show Probiotic Features. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.M.; Park, T.J.; Lee, H.H.; Hong, H.; Chi, W.J.; Kim, S.Y. Inhibition of Melanin Synthesis and Inflammation by Exosomes Derived from Leuconostoc mesenteroides DB-14 Isolated from Camellia japonica Flower. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 35, e2411080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Shin, T.S.; Kim, J.S.; Jee, Y.K.; Kim, Y.K. A new horizon of precision medicine: Combination of the microbiome and extracellular vesicles. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 466–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corso, G.; Mager, I.; Lee, Y.; Gorgens, A.; Bultema, J.; Giebel, B.; Wood, M.J.A.; Nordin, J.Z.; Andaloussi, S.E. Reproducible and scalable purification of extracellular vesicles using combined bind-elute and size exclusion chromatography. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngamwongsatit, P.; Banada, P.P.; Panbangred, W.; Bhunia, A.K. WST-1-based cell cytotoxicity assay as a substitute for MTT-based assay for rapid detection of toxigenic Bacillus species using CHO cell line. J. Microbiol. Methods 2008, 73, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, K.; Mareninov, S.; Diaz, M.F.P.; Yong, W.H. An Introduction to Performing Immunofluorescence Staining. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1897, 299–311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kurata, A.; Kiyohara, S.; Imai, T.; Yamasaki-Yashiki, S.; Zaima, N.; Moriyama, T.; Kishimoto, N.; Uegaki, K. Characterization of extracellular vesicles from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Zhao, A.; He, D.; Wu, X.; Yan, H.; Zhu, L. Isolation and Proteomic Analysis of Extracellular Vesicles from Lactobacillus salivarius SNK-6. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 34, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Mao, B.; Tang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Chen, W.; Cui, S. Lactic acid bacteria derived extracellular vesicles: Emerging bioactive nanoparticles in modulating host health. Gut Microbes 2024, 16, 2427311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, T.; Li, M.; Liu, Q.; Yu, A.; Cheng, K.; Ma, J.; Murphy, S.; McNutt, P.M.; Zhang, Y. Insights into optimizing exosome therapies for acute skin wound healing and other tissue repair. Front. Med. 2024, 18, 258–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Zhang, B.; Wang, W.; Bu, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhang, P.; Zeng, L. Plant-Derived Exosome-Like Nanovesicles in Chronic Wound Healing. Int. J. Nanomed. 2024, 19, 11293–11303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Choi, S.J.; Choi, H.I.; Choi, J.P.; Park, H.K.; Kim, E.K.; Kim, M.J.; Moon, B.S.; Min, T.K.; Rho, M.; et al. Lactobacillus plantarum-derived Extracellular Vesicles Protect Atopic Dermatitis Induced by Staphylococcus aureus-derived Extracellular Vesicles. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2018, 10, 516–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, C.S.; Myung, C.H.; Yoon, Y.C.; Ahn, B.H.; Min, J.W.; Seo, W.S.; Lee, D.H.; Kang, H.C.; Heo, Y.H.; Choi, H.; et al. The Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum Extracellular Vesicles from Korean Women in Their 20s on Skin Aging. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 526–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sirover, M.A. On the functional diversity of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase: Biochemical mechanisms and regulatory control. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1810, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Szalay, S.; Wertz, P.W. Protective Barriers Provided by the Epidermis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dror, B.; Savidor, A.; Salam Bolaji, B.; Sela, N.; Lampert, Y.; Teper-Bamnolker, P.; Daus, A.; Carmeli, S.; Sela, S.; Eshel, D. High Levels of CO2 Induce Spoilage by Leuconostoc mesenteroides by Upregulating Dextran Synthesis Genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 85, e00473-00418. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, R.T.d.; Bersaneti, G.T.; Bigotto, B.G.; Silveira, V.A.I.; Lonni, A.A.S.G.; Borsato, D.; Celligoi, M.A.P.C. Development of a facial biocosmetic containing levan, almond and cinnamon oils with antioxidant and moisturizing properties. Acta Sci. Biol. Sci. 2022, 44, e58869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, R.; Sakaguchi, K.; Matsuzaki, C.; Katoh, T.; Ishida, N.; Yamamoto, K.; Hisa, K. Levansucrase from Leuconostoc mesenteroides NTM048 produces a levan exopolysaccharide with immunomodulating activity. Biotechnol. Lett. 2016, 38, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marko, L.; Paragh, G.; Ugocsai, P.; Boettcher, A.; Vogt, T.; Schling, P.; Balogh, A.; Tarabin, V.; Orso, E.; Wikonkal, N.; et al. Keratinocyte ATP binding cassette transporter expression is regulated by ultraviolet light. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2012, 116, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.W.; Jung, Y.; Kim, H.D.; Kim, J. Ribosomal protein S3-derived repair domain peptides regulate UV-induced matrix metalloproteinase-1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 530, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.; Rego, L.; Martins, M.S.; Ferreira, M.S.; Cruz, M.T.; Sousa, E.; Almeida, I.F. How to Promote Skin Repair? In-Depth Look at Pharmaceutical and Cosmetic Strategies. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biniek, K.; Levi, K.; Dauskardt, R.H. Solar UV radiation reduces the barrier function of human skin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 17111–17116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| (A) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Setting | ||

| Analytical Column | EASY-Spray PepMap RSLC C18 (50 cm × 75 μm, 2 μm; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) | ||

| Mobile phase | A: 0.1% Formic acid in water B: 0.1% Formic acid in Acetonitrile | ||

| Flow rate | 300 mL/min | ||

| Injection Volume | 1 μL (1 μg peptide) | ||

| Column Temperature | 50.0 °C | ||

| Autosampler Temperature | 4.0 °C | ||

| Elution condition (Gradient) | Time (min) | A (%) | B (%) |

| 0 | 95 | 5 | |

| 45 | 50 | 50 | |

| 48 | 5 | 95 | |

| 52 | 5 | 95 | |

| 55 | 95 | 5 | |

| 70 | 95 | 5 | |

| (B) | |||

| Parameter | Setting | ||

| Equipment | Q Exactive Plus Hybrid Quadrupole-Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) | ||

| Ion Mode | ESI | ||

| Full MS condition | |||

| Resolution | 70,000 | ||

| Scan Range | 350–2000 m/z | ||

| Maximum IT | 120 ms | ||

| Polarity Volume | Positive | ||

| MS/MS condition (DDA: Data Dependent Acquisition) | |||

| Resolution | 17,500 | ||

| AGC | 5.00 × 105 | ||

| Isolation width | 1.2 m/z | ||

| Top N | 20 | ||

| NCE | 25% | ||

| Maximum IT | 80 ms | ||

| Dynamic Exclusion | 30 s | ||

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Precursor mass tolerance | 10 ppm |

| Fragment mass tolerance | 0.02 Da |

| Enzyme | Trypsin |

| Miss cleavage | 2 |

| Static modification | Carbamidomethyl (C) |

| 1st Antibody | 2nd Antibody | |

|---|---|---|

| Marker | Host | |

| Filaggrin | Rabbit | FITC–anti rabbit |

| Involucrin | Rabbit | FITC–anti rabbit |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baek, J.; Cho, S.; Lee, G.; Ki, H.; Kim, S.Y.; Choi, G.-m.; Kim, J.H.; Kim, J.-W.; Park, C.-M.; Kim, S.-Y.; et al. Modulation of Moisturizing and Barrier Related Molecular Markers by Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Leuconostoc mesenteroides DB-21 Isolated from Camellia japonica Flower. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 1022. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121022

Baek J, Cho S, Lee G, Ki H, Kim SY, Choi G-m, Kim JH, Kim J-W, Park C-M, Kim S-Y, et al. Modulation of Moisturizing and Barrier Related Molecular Markers by Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Leuconostoc mesenteroides DB-21 Isolated from Camellia japonica Flower. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2025; 47(12):1022. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121022

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaek, Junseok, Seongguk Cho, Gibok Lee, Hosam Ki, Su Young Kim, Gyu-min Choi, Jae Hong Kim, Ji-Woong Kim, Chang-Min Park, Seung-Young Kim, and et al. 2025. "Modulation of Moisturizing and Barrier Related Molecular Markers by Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Leuconostoc mesenteroides DB-21 Isolated from Camellia japonica Flower" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 47, no. 12: 1022. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121022

APA StyleBaek, J., Cho, S., Lee, G., Ki, H., Kim, S. Y., Choi, G.-m., Kim, J. H., Kim, J.-W., Park, C.-M., Kim, S.-Y., Choi, B.-M., & Choi, Y. G. (2025). Modulation of Moisturizing and Barrier Related Molecular Markers by Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Leuconostoc mesenteroides DB-21 Isolated from Camellia japonica Flower. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 47(12), 1022. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121022