Abstract

According to the World Health Organization’s statement, myocarditis is an inflammatory myocardium disease. Although an endometrial biopsy remains the diagnostic gold standard, it is an invasive procedure, and thus, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging has become more widely used and is called a non-invasive diagnostic gold standard. Myocarditis treatment is challenging, with primarily symptomatic therapies. An increasing number of studies are searching for novel diagnostic biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets. Microribonucleic acids (miRNAs) are small, non-coding RNA molecules that decrease gene expression by inhibiting the translation or promoting the degradation of complementary mRNAs. Their role in different fields of medicine has been recently extensively studied. This review discusses all relevant preclinical in vitro studies regarding microRNAs in myocarditis. We searched the PubMed database, and after excluding unsuitable studies and clinical and preclinical in vivo trials, we included and discussed 22 preclinical in vitro studies in this narrative review. Several microRNAs presented altered levels in myocarditis patients in comparison to healthy controls. Moreover, microRNAs influenced inflammation, cell apoptosis, and viral replication. Finally, microRNAs were also found to determine the level of myocardial damage. Further studies may show the vital role of microRNAs as novel therapeutic agents or diagnostic/prognostic biomarkers in myocarditis management.

1. Introduction

1.1. Myocarditis—Basic Information

The World Health Organization statement defines myocarditis as an inflammatory disease of the myocardium, diagnosed using histological, immunological, or immunohistochemical criteria [1]. According to the European Society of Cardiology’s statement, endomyocardial biopsy remains the gold standard for a definite diagnosis [2]; however, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging is increasingly recommended as the preferable non-invasive approach [3]. Various etiologies are listed among causes that may lead to developing myocarditis, headed by infections, mainly viral, and autoimmune conditions [4]. Notably, the most commonly affected group, in contrast to other well-known cardiac diseases, such as myocardial infarction or heart failure, are young adults, with a slight dominance of men [5]. Noteworthily, myocarditis was indicated as one of the leading causes of sudden cardiac death and dilated cardiomyopathy [6]. However, it is hard to estimate the prevalence worldwide due to the diverse clinical presentation. According to the reports, it varies between 0.12% and 12% [5].

Although much progress has been made in recent years in myocarditis diagnosis [7,8] with the development of novel non-invasive diagnostic tools [7], there remains a lack of treatment-focused studies [9]. Therefore, therapy remains mainly supportive and symptomatic, focusing on hemodynamic stabilization [10]. The long-term prognosis depends primarily on the cause of the disease [3,9]. Establishing a targeted therapy would allow us to provide patients with optimal management and lead to better long-term outcomes.

1.2. microRNAs—Small Regulators of Gene Expression

Microribonucleic acids (microRNAs, miRNAs, and miRs) are small, non-coding RNA molecules that regulate gene expression [11]. They consist of about 20–25 nucleotides [12] and fulfil their molecular role through binding to the complementary sequences of messenger RNAs (mRNAs), thus promoting mRNA degradation or inhibiting translation. In turn, protein synthesis is blocked [13]. MicroRNAs can be found and measured in different body fluids, such as blood, urine, or cerebrospinal fluid.

Briefly, miRNA biosynthesis starts in the nucleus and continues in the cytoplasm, where Drosha and Dicer, two RNase III proteins, process premature molecules [14,15]. In the final step, the guide strand remains and represents mature miRNA, while a passenger strand is discarded [16]. This is the canonical way and results in the formation of the 5′ miRNA involved in regulating gene expression. Most miRNAs are produced likewise; nevertheless, the different pathways independent of Drosha and Dicer are also known [17]. In turn, the 3′ miRNA can also be formed to bind with complementary mRNAs. This review includes information about the miRNA’s end whenever the authors clearly state it.

MiRNAs have been thoroughly studied in recent years. Their putative role in multiple diseases in diverse fields of medicine was described, including cardiology [18,19], oncology [20,21], neurology [22], and autoimmune diseases [23]. Researchers often investigated the involvement of miRNAs in the pathogenesis of the disease, trying to find cause-and-effect relationships. Nevertheless, in some cases, they solely explored miRNAs as potential disease biomarkers without searching for an underlying cause of uncovered miRNA deregulation.

1.3. Suggested Value of MicroRNAs in Myocarditis

MiRNAs are altered in several cardiological conditions, including myocarditis. A recent study showed that not only circulating but also exosome-derived miRNAs may play a vital role in the mechanisms of myocarditis [24]. Regarding usually uncertain diagnoses [22] and mainly symptomatic treatment without targeted therapy options [25], microRNAs are considered a chance to facilitate myocarditis management. Several clinical and preclinical studies analyzed miRNAs’ potential role in myocarditis, drawing promising conclusions. We aimed to discuss all of these studies comprehensively.

In previous reviews, we have already summarized clinical trials and in vivo preclinical trials [26,27]. In this review, the last one from the series about microRNAs in myocarditis, we aimed to analyze preclinical in vitro studies thoroughly. Apart from the diagnostic utilities of microRNAs, we also aimed to focus on the possibilities that miRNAs bring to myocarditis therapy.

2. Methodology

The role of miRNAs in myocarditis has been investigated in multiple studies. Therefore, only preclinical in vitro trials have been included in this narrative review to narrow the list of suitable research items and allow for a more accurate and solid discussion. Commentaries, letters to the editors, case reports, reviews, and clinical and preclinical in vivo studies were excluded. Articles written in languages other than English were not included.

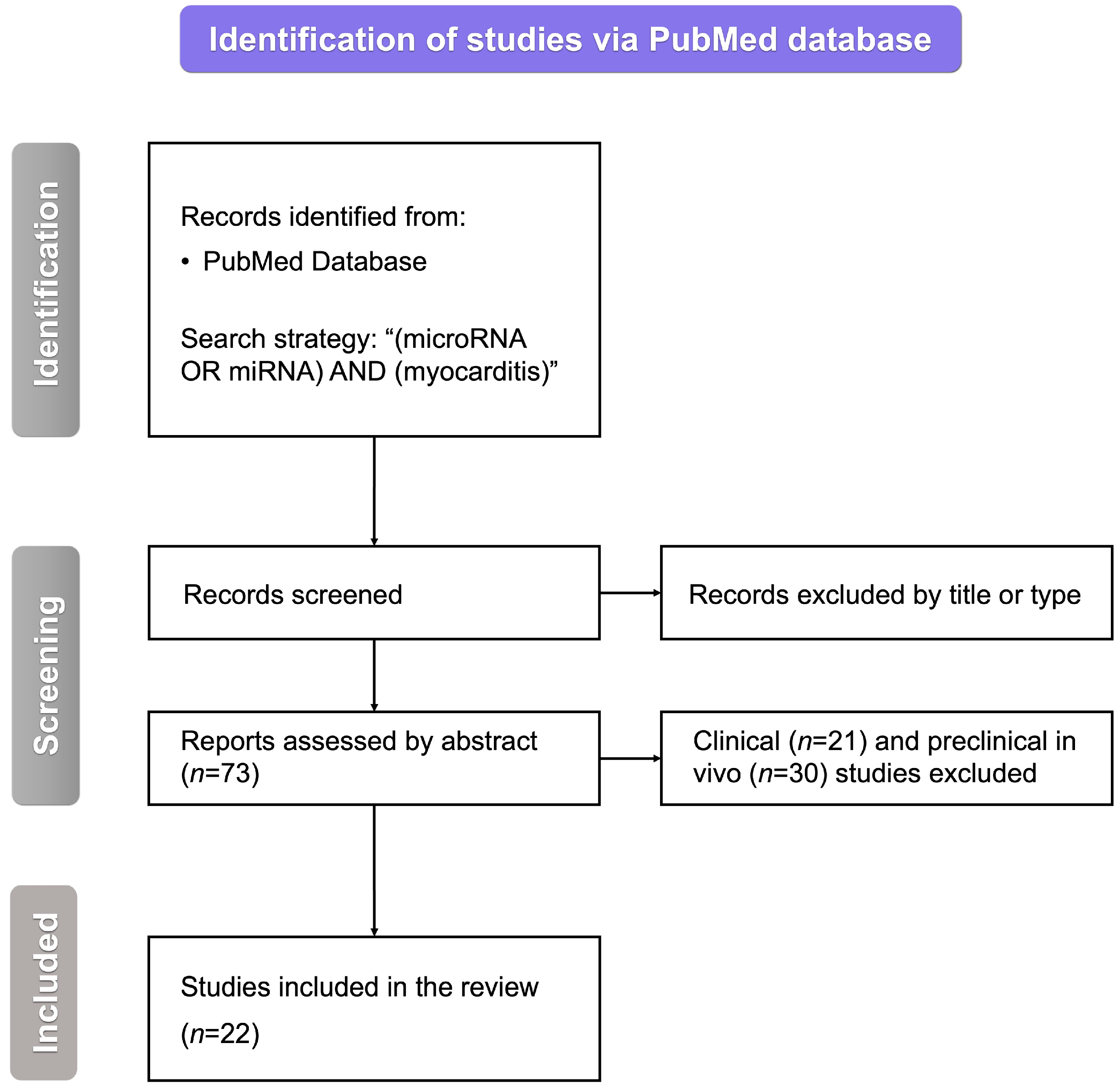

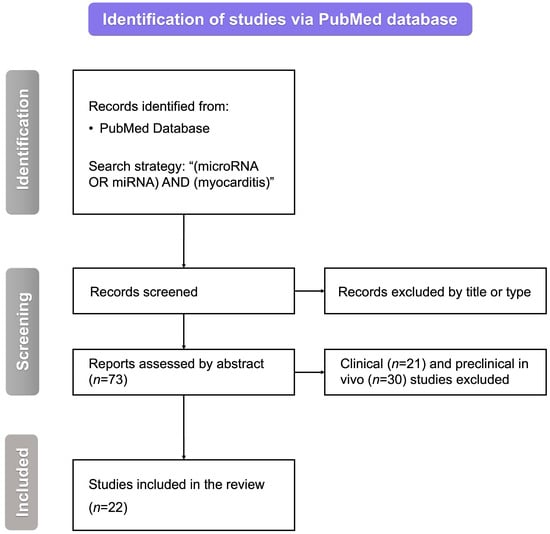

We searched the PubMed database with the following query: “(miRNA OR microRNA) AND (myocarditis)”. After removing inappropriate studies by title, type, or abstract, we were left with 73 articles regarding the role of miRNAs in myocarditis. Excluding all of the papers other than those of original preclinical in vitro studies yielded 22 papers to be included in this review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The flowchart for the selection process. miRNA—microRNA, n—the number of studies, and RNA—ribonucleic acid.

All included studies were divided into five paragraphs: (i) microRNA alterations in myocarditis, (ii) microRNA influence on myocardial inflammation, (iii) viral replication dependence on microRNAs, (iv) microRNA impact on cell apoptosis, and (v) in vitro models presenting the role of microRNAs in cardiac dysfunction.

3. MicroRNAs in an In Vitro Model of Myocarditis

3.1. microRNA Alterations in Myocarditis

Some in vitro studies presented clearly that miRNAs are altered significantly in the myocarditis model. Yao et al. [28] conducted a study investigating HeLa cells infected with CVB3 (Coxsackievirus B3) and compared them to non-infected cells. It was shown that the miR-107 level was elevated in the study group in comparison to the control group. The higher expression of miR-107 was related to CVB3 infection and associated with viral replication. Liu et al. [29] carried out a study consisting of an in vivo and in vitro part. In this review, we focused on the latter. It was shown that CVB3-infected HeLa cells demonstrated higher levels of miR-324-3p than non-infected cells. Lin et al. [30] studied CVB3-infected HL-1 cells. It was demonstrated that these cells presented increased levels of miR-19b compared to mock-infected HL-1 cells. All studies mentioned in this paragraph, with some additional information, are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

A summary of studies focusing on microRNA alterations in myocarditis.

3.2. microRNA Influence on Myocardial Inflammation

Several studies focused on miRNA impact on cardiac inflammation, the pathogenic base of myocarditis. Pan et al. [31] analyzed human cardiomyocytes that had been exposed to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to induce myocarditis. Researchers measured the levels of interleukin 1β (IL-1β) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) to assess pyroptosis and cardiac inflammation. The levels of inflammatory factors were reduced in cells treated with miR-223-3p encapsulated in extracellular vesicles compared to the control group without any intervention. Zhu et al. [32], similar to the previous researchers, studied LPS-induced cardiomyocytes in which SOX2 overlapping transcript (SOX2OT), which substantially contributes to heart damage, was silenced. An miR-215-5p inhibitor was transfected into the cells to abolish the suppressive role of SOX2OT-knockdown on IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) production. This intervention restored the elevated levels of these inflammatory factors in cells primarily caused by induction with LPS. After all, miR-215-5p was shown to play an anti-inflammatory role. Another study in which human cardiomyocytes were treated with LPS to imitate viral myocarditis was performed by Wang et al. [33]. Due to this intervention, the level of miR-16 was profoundly downregulated. These cells were then transfected with miR-16 mimic and compared to (i) normal cells, (ii) LPS-induced cells, and (iii) LPS-induced cells treated with an miR-16 inhibitor. Cardiomyocytes treated with LPS presented considerably higher levels of inflammatory factors—IL-6, interleukin 8 (IL-8), and TNF-α. However, it was repressed by miR-16 mimic administration.

Fei et al. [34] showed that the miR-146a level was elevated in CVB3-infected HeLa cells in comparison to non-infected ones. Moreover, it was proved that adding an miR-146a mimic exerted an anti-inflammatory effect on CVB3-infected cells. The group treated with this miR mimic showed decreased levels of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and TNF-α) compared to cells treated with the miR-146a antagonist. Toll-like receptor 3 (detecting viral RNA) was identified as a main target for miR-146a. Fan et al. [35] also conducted research using the HeLa cells model. It was shown that CVB3-infected cells presented elevated levels of miR-181d and miR-30a compared to control cells. Treating infected cells with miR-181d or miR-30a mimics caused an increase in the level of IL-6, while transfecting cells with inhibitors of these miRNAs caused a decrease in IL-6 levels. Chen et al. [36] compared the levels of inflammatory cytokines in CVB3-infected HeLa cells treated with either a mimic or an antagonist of miR-214. Transfection with miR-214 mimic was shown to increase the levels of TNF-α and IL-6. MiR-214 inhibition might be a possible strategy in myocarditis treatment.

A slightly different study was conducted by Chen et al. [37]. Apart from the in vivo part of their study, the researchers also isolated B-cells from the hearts of mice with myocarditis. Wild B-cells with normal miR-98 expression were compared to miR-98-deficient ones. LPS alone and LPS with TNF-α were added to both cultures. It was demonstrated that in LPS-treated cultures, the level of IL-10 was increased. The presence of TNF-α abolished this effect but only in wild B-cells. In B-cells presenting reduced levels of miR-98, the presence of TNF-α did not impact the IL-10 increase caused by LPS. Overall, miR-98 was shown to play a protective role in myocarditis. As concluded by the authors, miR-98 might be considered a potential therapeutic target in the treatment of myocarditis. All studies mentioned in this paragraph, with some additional information, are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

A summary of studies regarding the influence of microRNAs on inflammation.

3.3. Viral Replication Dependence on microRNAs

Germano et al. [38] studied the role of miR-590-5p in promoting viral infection. It was presented that cardiomyocytes exposed to CVB had significantly higher levels of miR-590-5p than normal cells. However, the injection of antagomiR-590-5p was shown to decrease viral load and replication. Another microRNA promoting viral replication was explored by Ye et al. [39], who also conducted a study on CVB3-infected HeLa cells. To analyze the role of miR-126 in viral myocarditis, the cells were treated with a mimic, an inhibitor, or a negative control of miR-126. Administration of an miR-126 mimic caused an increase in viral replication. Accordingly, the injection of an miR-126 inhibitor decreased the viral load. Overall, it was shown that miR-126 promoted CVB3 myocarditis.

Similarly, He et al. [40] conducted a study with HeLa cells infected with CVB3. It appeared that the viral replication was suppressed after miR-21 injection as compared to non-mammal miR. Liu et al. [29] modified CVB3-infected HeLa cells to overexpress miR-343-3p or to knockdown this miR expression. Cells overexpressing miR-343-3p had lower levels of viral capsid protein 1, a marker of viral replication, than miRNA-silenced ones. He et al. [41] engineered CVB3 to contain target sequences for miRNAs important in suppressing viral myocarditis (miR-133 and miR-206). Afterward, these modified viruses were injected into HeLa cells. As a result, viral replication was lowered, and cell viability was increased compared to the controls treated with either CVB3 containing negative control miRNA target sequences or non-modified CVB3. Considering the above, CVB3 containing target sequences for miR-133 or miR-206 is a promising candidate for CVB3 vaccines. Finally, Corsten et al. [42] investigated neonatal rat cardiomyocytes infected with CVB3. The cells were then treated with an inhibitor, a mimic, and a scrambled control of the miR-221/-222 cluster. After inhibitor addition, the viral replication was elevated. Consistently, transfection with the mimic of the miR-221/-222 cluster caused a decrease in viral load. All studies mentioned in this paragraph, with some additional information, are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

A summary of studies showing the effect of administrating microRNA mimics or antagonists on viral replication.

3.4. microRNA Impact on Cell Apoptosis

Several studies explored not only the influence on inflammatory response or viral load but also how microRNAs affect apoptosis. Zhang et al. [43] analyzed human cardiomyocytes overexpressing miR-8055 and compared them to the miR-8055-silenced cardiomyocytes. Cells with miR-8055 overexpression presented decreased levels of inflammatory factors, myocardial injury biomarkers, and apoptotic cell ratio. Similarly, Xiang et al. [44] showed that H9c2 cells exposed to LPS and subsequently treated with an miR-27a mimic had ameliorated cell viability; thus, the apoptotic cell ratio was decreased (control cells were injected with an miR-27a inhibitor). Overall, it was proved that miR-27a was protective in LPS-damaged H9c2 cells. Li et al. [45] explored the influence of an miR-203 inhibitor and mimic on H9c2 cells exposed to LPS. The downregulation of miR-203 promoted cell survival, lowered apoptotic rate, and decreased levels of inflammatory cytokines. On the other hand, miR-203 overexpression exacerbated cell apoptosis and contributed to an increased inflammatory response. As suggested by the authors, miR-203 plays its role by inhibiting the expression of a nuclear factor interleukine-3 (NFIL3), a survival mediator in the heart.

Tong et al. [46] studied the role of miR-15 in CVB3-infected H9c2 cells. The miR-15 inhibitor was added to these cells and compared to three other groups: (i) normal H9c2 cells, (ii) CVB3-infected H9c2 cells, and (iii) CVB3-infected cells treated with the negative control miR. It was demonstrated that the group receiving the miR-15 inhibitor presented lower levels of inflammatory factors—IL-1β, IL-6, and interleukin 18 (IL-18). Moreover, miR-15 inhibition promoted the viability of CVB3-infected cells. Xia et al. [47] also conducted the in vitro part of their study on CVB3-infected H9c2 cells. They demonstrated that both miR-217 and miR-543 inhibitors caused a reduction in cell apoptosis and mitigation of inflammatory response (measured as IL-1β and IL-6 levels). Li et al. [48] presented that CVB3-infected H9c2 cells showed restrained expression levels of miR-16 compared to non-infected cells. Furthermore, the levels of inflammatory factors (IL-6 and TNF-α) and cell apoptosis decreased in the viral myocarditis cell model after transfection with an miR-16 mimic.

Zhang et al. [49] performed the preclinical part of their study on human cardiomyocytes. They showed that treating these cells with an miR-98 mimic caused a decrease in the expression of FAS and FASL genes. Furthermore, the apoptotic cell ratio was decreased in cells overexpressing miR-98. All studies discussed in this paragraph, with some additional information, are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

A summary of studies presenting the influence of microRNAs on apoptosis.

3.5. In Vitro Models Presenting the Role of microRNAs in Cardiac Dysfunction

Xu et al. [50] investigated cardiomyocytes derived from neonatal rats, aiming to assess the influence of overexpressed miR-1 on the level of connexin 43 (Cx43)—an important transmembrane protein. It was observed that the upregulation of miR-1 decreased Cx43 expression. The decrease in Cx43 may lead to interference with cardiac function in myocarditis. In the previously mentioned study [30], researchers transfected human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSCs-CMs) with the miR-19b mimic since it was shown to be upregulated in the VMC model. Irregular beats and decreased beating rates were observed as a result of this intervention. Gap junction protein α1, responsible for the electrical synchrony of cardiomyocytes, was indicated as a target for miR-19b. Thus, the dysregulation of miR-19b might explain arrhythmia occurrence in viral myocarditis patients. Both studies mentioned in this paragraph, with additional information, are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

A summary of studies showing the role of microRNAs in cardiac dysfunction.

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

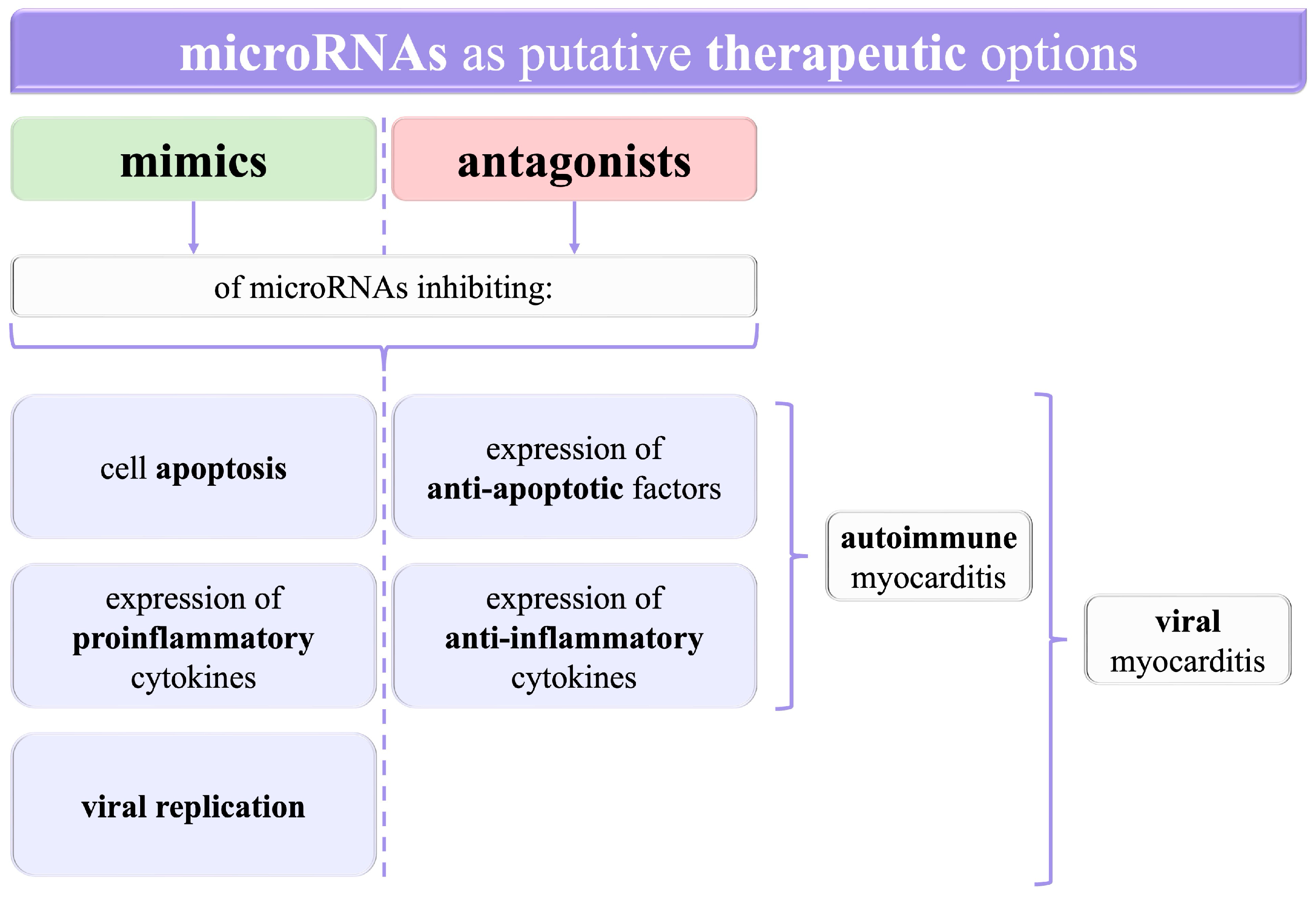

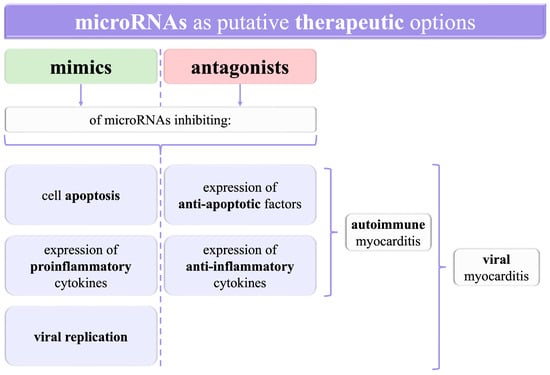

MiRNAs are being increasingly investigated in many diseases in various fields of medicine, thus creating novel opportunities for their better management. Amongst them, myocarditis has also been thoroughly researched. Here, we have presented different perspectives from preclinical in vitro trials on the value of miRNAs in myocarditis. MiRNAs influence mechanisms in myocarditis, such as inflammation, apoptosis, and viral replication. Moreover, particular miRNAs are observed to have different levels in the groups of patients and healthy controls. It is crucial not only for myocarditis diagnostic options but also for targeted therapies using either mimics or antagonists of miRNAs (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A graphical summary of the opportunities to use microRNAs as potential targets for therapeutic agents. RNA—ribonucleic acid.

Since microRNAs have been shown to influence the levels of diverse proteins, such as inflammatory factors, further investigations into myocarditis should bring new insights into the molecular bases of the disease. Since the treatment remains mainly symptomatic in both viral and autoimmune myocarditis, with attempts to administer antiviral drugs in the former and immunosuppressives in the latter, a better understanding of the pathogenesis may increase the role of targeted therapy. For instance, mimics of miRNAs decreasing the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, as well as antagonists of miRNAs exerting an anti-inflammatory effect, can presumably alleviate inflammation directly in the myocardium. This could enable the avoidance of harmful systemic adverse reactions of immunosuppressive drugs.

Some miRNAs may be crucial in terms of viral replication. Administrating inhibitors of those miRNAs that were shown to increase viral load might be a potential treatment for viral myocarditis. Similarly, inducing overexpression of microRNAs which are related to decreased viral replication is another putative therapy option. Finally, medications based on microRNAs may be used to reduce cell apoptosis and therefore halt the deterioration of the myocardium and prevent impaired heart function after recovery from myocarditis.

Few in vitro studies focused on the correlation between miRNAs and cardiac function; nevertheless, they cannot be missed. Myocarditis, in some cases, leads to permanent impairment of cardiac function, for instance, cardiomyopathies, especially dilated cardiomyopathy, or potentially life-threatening arrhythmias. Therefore, finding a valuable prognostic biomarker would help assess the patient’s prognosis and identify those patients who need a more comprehensive approach. As discussed, arrhythmia occurrence in viral myocarditis patients may be partially explained by the dysregulation of miR-19b, and thus, it emerges as another potential therapeutic target.

In conclusion, miRNAs can also be useful as prognostic biomarkers or in targeted therapy, in addition to their role in myocarditis diagnosis. However, more studies exploring this issue are needed. Investigations of the effects of mimics or antagonists of particular microRNAs in myocarditis models may bring us closer to better management of myocarditis with more specific approaches.

5. Limitations

First, we searched only the PubMed database, which might have led to omitting some studies in the field. Nevertheless, it should not cause any statistical or reasoning bias since we performed solely a literature overview in a narrative style. The lack of statistical analysis of discussed data is another limitation. The narrative nature of our review can also explain this. Due to the same reasons, we evaded the risk of bias analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.G. and G.P.; methodology, O.G.; writing—original draft preparation, O.G.; writing—review and editing, G.P.; visualization, O.G.; supervision, M.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by grant no. 12/TJ_2/2023 to O.G., and grant no. 85/TJ_2/2023 to G.P. Both grants are funded within “Talenty Jutra” by “Fundacja Empiria i Wiedza”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Richardson, P.; McKenna, W.; Bristow, M.; Maisch, B.; Mautner, B.; O’Connell, J.; Olsen, E.; Thiene, G.; Goodwin, J.; Gyarfas, I.; et al. Report of the 1995 World Health Organization/International Society and Federation of Cardiology Task Force on the Definition and Classification of cardiomyopathies. Circulation 1996, 93, 841–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caforio, A.L.; Pankuweit, S.; Arbustini, E.; Basso, C.; Gimeno-Blanes, J.; Felix, S.B.; Fu, M.; Heliö, T.; Heymans, S.; Jahns, R.; et al. Current state of knowledge on aetiology, diagnosis, management, and therapy of myocarditis: A position statement of the European Society of Cardiology Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 2636–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagar, S.; Liu, P.P.; Cooper, L.T., Jr. Myocarditis. Lancet 2012, 379, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampejo, T.; Durkin, S.M.; Bhatt, N.; Guttmann, O. Acute myocarditis: Aetiology, diagnosis and management. Clin. Med. 2021, 21, e505–e510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blauwet, L.A.; Cooper, L.T. Myocarditis. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2010, 52, 274–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali-Ahmed, F.; Dalgaard, F.; Al-Khatib, S.M. Sudden cardiac death in patients with myocarditis: Evaluation, risk stratification, and management. Am. Heart J. 2020, 220, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeserich, M.; Konstantinides, S.; Pavlik, G.; Bode, C.; Geibel, A. Non-invasive imaging in the diagnosis of acute viral myocarditis. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2009, 98, 753–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccirillo, F.; Nusca, A.; Di Sciascio, G. Incidence, diagnosis, and prognosis of myocarditis: Does gender matter? Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2022, 132, 16246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammirati, E.; Frigerio, M.; Adler, E.D.; Basso, C.; Birnie, D.H.; Brambatti, M.; Friedrich, M.G.; Klingel, K.; Lehtonen, J.; Moslehi, J.J.; et al. Management of Acute Myocarditis and Chronic Inflammatory Cardiomyopathy: An Expert Consensus Document. Circ. Heart Fail. 2020, 13, e007405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, M.A.; Koyfman, A.; Foran, M. Myocarditis. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2014, 30, 832–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P.T.B.; Clark, I.M.; Le, L.T.T. MicroRNA-Based Diagnosis and Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kara, G.; Arun, B.; Calin, G.A.; Ozpolat, B. miRacle of microRNA-Driven Cancer Nanotherapeutics. Cancers 2022, 14, 3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalanotto, C.; Cogoni, C.; Zardo, G. MicroRNA in Control of Gene Expression: An Overview of Nuclear Functions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, M.; Kim, V.N. Regulation of microRNA biogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 509–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafin, R.N.; Khusnutdinova, E. Perspective for Studying the Relationship of miRNAs with Transposable Elements. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 3122–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Gregory, R.I. MicroRNA biogenesis pathways in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, S.M. An overview of microRNAs. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2015, 87, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krauze, A.; Procyk, G.; Gąsecka, A.; Garstka-Pacak, I.; Wrzosek, M. The Role of MicroRNAs in Aortic Stenosis-Lessons from Recent Clinical Research Studies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procyk, G.; Klimczak-Tomaniak, D.; Sygitowicz, G.; Tomaniak, M. Circulating and Platelet MicroRNAs in Cardiovascular Risk Assessment and Antiplatelet Therapy Monitoring. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussen, B.M.; Hidayat, H.J.; Salihi, A.; Sabir, D.K.; Taheri, M.; Ghafouri-Fard, S. MicroRNA: A signature for cancer progression. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 138, 111528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziechciowska, I.; Dąbrowska, M.; Mizielska, A.; Pyra, N.; Lisiak, N.; Kopczyński, P.; Jankowska-Wajda, M.; Rubiś, B. miRNA Expression Profiling in Human Breast Cancer Diagnostics and Therapy. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2023, 45, 9500–9525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grodzka, O.; Słyk, S.; Domitrz, I. The Role of MicroRNA in Migraine: A Systemic Literature Review. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 43, 3315–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirzaei, R.; Zamani, F.; Hajibaba, M.; Rasouli-Saravani, A.; Noroozbeygi, M.; Gorgani, M.; Hosseini-Fard, S.R.; Jalalifar, S.; Ajdarkosh, H.; Abedi, S.H.; et al. The pathogenic, therapeutic and diagnostic role of exosomal microRNA in the autoimmune diseases. J. Neuroimmunol. 2021, 358, 577640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Huang, C.; Chen, R.; Li, D.; Zhang, G.; Yu, H.; Li, Y.; Song, B.; Zhang, N.; Li, B.; et al. Transcriptional and functional analysis of plasma exosomal microRNAs in acute viral myocarditis. Genomics 2024, 116, 110775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyaw, T.; Drummond, G.; Bobik, A.; Peter, K. Myocarditis: Causes, mechanisms, and evolving therapies. Expert. Opin. Ther. Targets 2023, 27, 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grodzka, O.; Procyk, G.; Gąsecka, A. The Role of MicroRNAs in Myocarditis-What Can We Learn from Clinical Trials? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procyk, G.; Grodzka, O.; Procyk, M.; Gąsecka, A.; Głuszek, K.; Wrzosek, M. MicroRNAs in Myocarditis-Review of the Preclinical In Vivo Trials. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, M.; Xu, C.; Shen, H.; Liu, T.; Wang, X.; Shao, C.; Shao, S. The regulatory role of miR-107 in Coxsackie B3 virus replication. Aging 2020, 12, 14467–14479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Tong, J.; Shao, C.; Qu, J.; Wang, H.; Shi, Y.; Lin, Y.; Liu, Y.; Shao, S.; Shen, H. MicroRNA-324-3p Plays A Protective Role Against Coxsackievirus B3-Induced Viral Myocarditis. Virol. Sin. 2021, 36, 1585–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Xue, A.; Li, L.; Li, B.; Li, Y.; Shen, Y.; Sun, N.; Chen, R.; Xu, H.; Zhao, Z. MicroRNA-19b Downregulates Gap Junction Protein Alpha1 and Synergizes with MicroRNA-1 in Viral Myocarditis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Yan, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, P.; Jing, Y.; Yu, J.; Hui, J.; Lu, Q. Mesenchymal stem cells-derived extracellular vesicles-shuttled microRNA-223-3p suppress lipopolysaccharide-induced cardiac inflammation, pyroptosis, and dysfunction. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 110, 108910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Peng, F.; Cui, X.; Li, J.; Sun, C. LncRNA SOX2OT facilitates LPS-induced inflammatory injury by regulating intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1) via sponging miR-215-5p. Clin. Immunol. 2022, 238, 109006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, G.; Ma, Y.; Zuo, H.; Tian, X. miR-16 exhibits protective function in LPS-treated cardiomyocytes by targeting DOCK2 to repress cell apoptosis and exert anti-inflammatory effect. Cell Biol. Int. 2020, 44, 1760–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fei, Y.; Chaulagain, A.; Wang, T.; Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Yi, M.; Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Lin, L.; Chen, S.; et al. MiR-146a down-regulates inflammatory response by targeting TLR3 and TRAF6 in Coxsackievirus B infection. RNA 2020, 26, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, K.L.; Li, M.F.; Cui, F.; Feng, F.; Kong, L.; Zhang, F.H.; Hao, H.; Yin, M.X.; Liu, Y. Altered exosomal miR-181d and miR-30a related to the pathogenesis of CVB3 induced myocarditis by targeting SOCS3. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 2208–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.G.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.B.; Zhang, S.L.; Zhao, L.H.; Liang, W.Q. Upregulated microRNA-214 enhances cardiac injury by targeting ITCH during coxsackievirus infection. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 1258–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Dong, S.; Zhang, N.; Chen, L.; Li, M.G.; Yang, P.C.; Song, J. MicroRNA-98 plays a critical role in experimental myocarditis. Int. J. Cardiol. 2017, 229, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germano, J.F.; Sawaged, S.; Saadaeijahromi, H.; Andres, A.M.; Feuer, R.; Gottlieb, R.A.; Sin, J. Coxsackievirus B infection induces the extracellular release of miR-590-5p, a proviral microRNA. Virology 2019, 529, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Hemida, M.G.; Qiu, Y.; Hanson, P.J.; Zhang, H.M.; Yang, D. MiR-126 promotes coxsackievirus replication by mediating cross-talk of ERK1/2 and Wnt/β-catenin signal pathways. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2013, 70, 4631–4644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Xiao, Z.; Yao, H.; Li, S.; Feng, M.; Wang, W.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J. The protective role of microRNA-21 against coxsackievirus B3 infection through targeting the MAP2K3/P38 MAPK signaling pathway. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Yao, H.; Wang, J.; Xiao, Z.; Xin, L.; Liu, Z.; Ma, X.; Sun, J.; Jin, Q.; Liu, Z. Coxsackievirus B3 engineered to contain microRNA targets for muscle-specific microRNAs displays attenuated cardiotropic virulence in mice. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 908–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsten, M.F.; Heggermont, W.; Papageorgiou, A.P.; Deckx, S.; Tijsma, A.; Verhesen, W.; van Leeuwen, R.; Carai, P.; Thibaut, H.J.; Custers, K.; et al. The microRNA-221/-222 cluster balances the antiviral and inflammatory response in viral myocarditis. Eur. Heart J. 2015, 36, 2909–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Han, B.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Feng, X.; Sun, W.; Cai, D.; Jia, H.; Jiang, D. Circular RNA circACSL1 aggravated myocardial inflammation and myocardial injury by sponging miR-8055 and regulating MAPK14 expression. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.F.; Yu, J.C.; Zhu, J.Y. Up-regulation of miR-27 extenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced injury in H9c2 cells via modulating ICAM1 expression. Genes Genom. 2019, 41, 1467–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Du, A.; Zhu, X.; Yu, B. miR-203 accelerates apoptosis and inflammation induced by LPS via targeting NFIL3 in cardiomyocytes. J. Cell Biochem. 2019, 120, 6605–6613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, R.; Jia, T.; Shi, R.; Yan, F. Inhibition of microRNA-15 protects H9c2 cells against CVB3-induced myocardial injury by targeting NLRX1 to regulate the NLRP3 inflammasome. Cell Mol. Biol. Lett. 2020, 25, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, K.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, D. miR-217 and miR-543 downregulation mitigates inflammatory response and myocardial injury in children with viral myocarditis by regulating the SIRT1/AMPK/NF-κB signaling pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2020, 45, 634–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.Q.; Xi, J.; Li, B.Q.; Li, N. MiR-16, as a potential NF-κB-related miRNA, exerts anti-inflammatory effects on LPS-induced myocarditis via mediating CD40 expression: A preliminary study. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2020, 34, e22426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.Y.; Zhao, Z.; Jin, Z. Expression of miR-98 in myocarditis and its influence on transcription of the FAS/FASL gene pair. Genet. Mol. Res. 2016, 15, mr.15027627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.F.; Ding, Y.J.; Shen, Y.W.; Xue, A.M.; Xu, H.M.; Luo, C.L.; Li, B.X.; Liu, Y.L.; Zhao, Z.Q. MicroRNA- 1 represses Cx43 expression in viral myocarditis. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2012, 362, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).