Disproportionality Analysis of Adverse Events Associated with IL-1 Inhibitors in the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

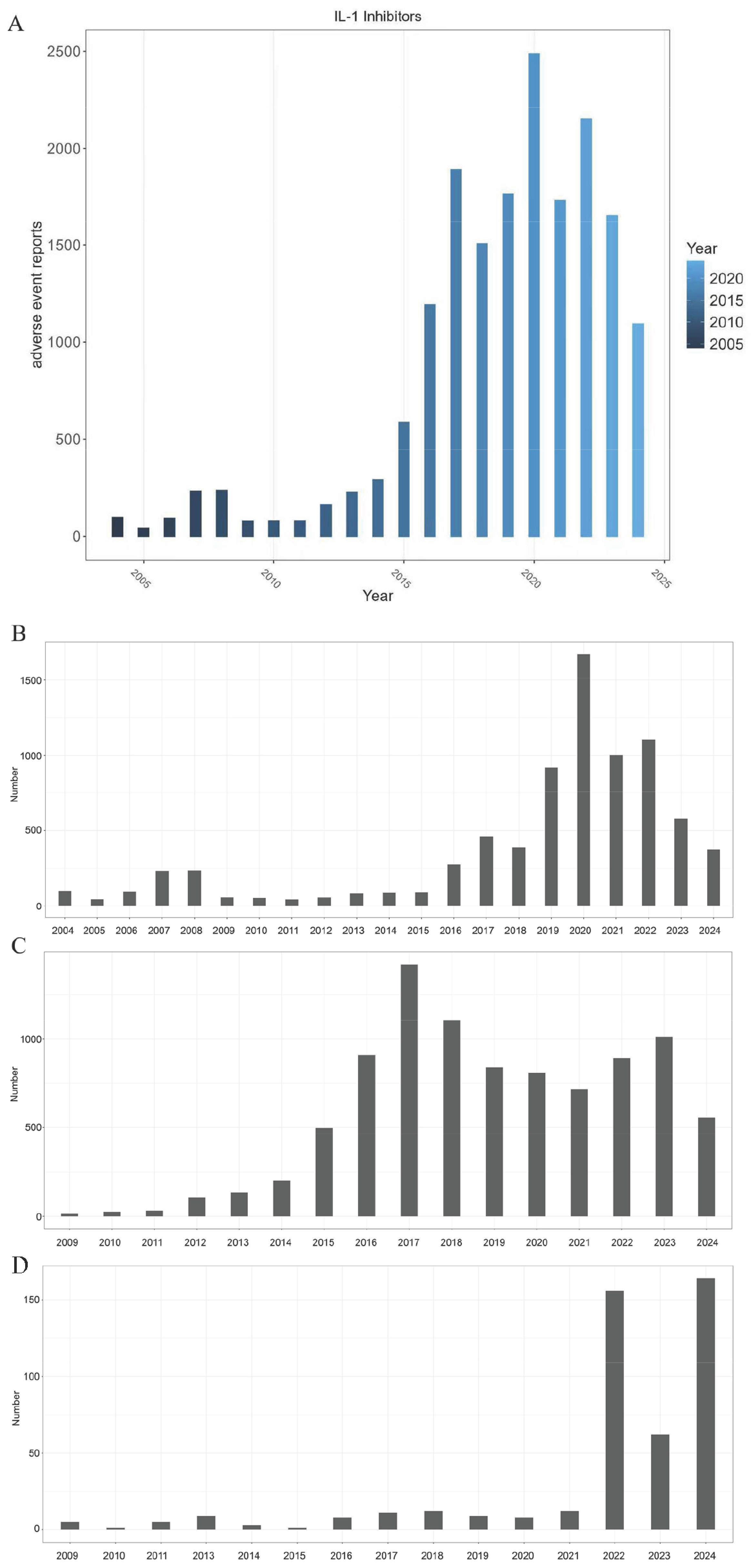

2.1. Basic Information of AEs

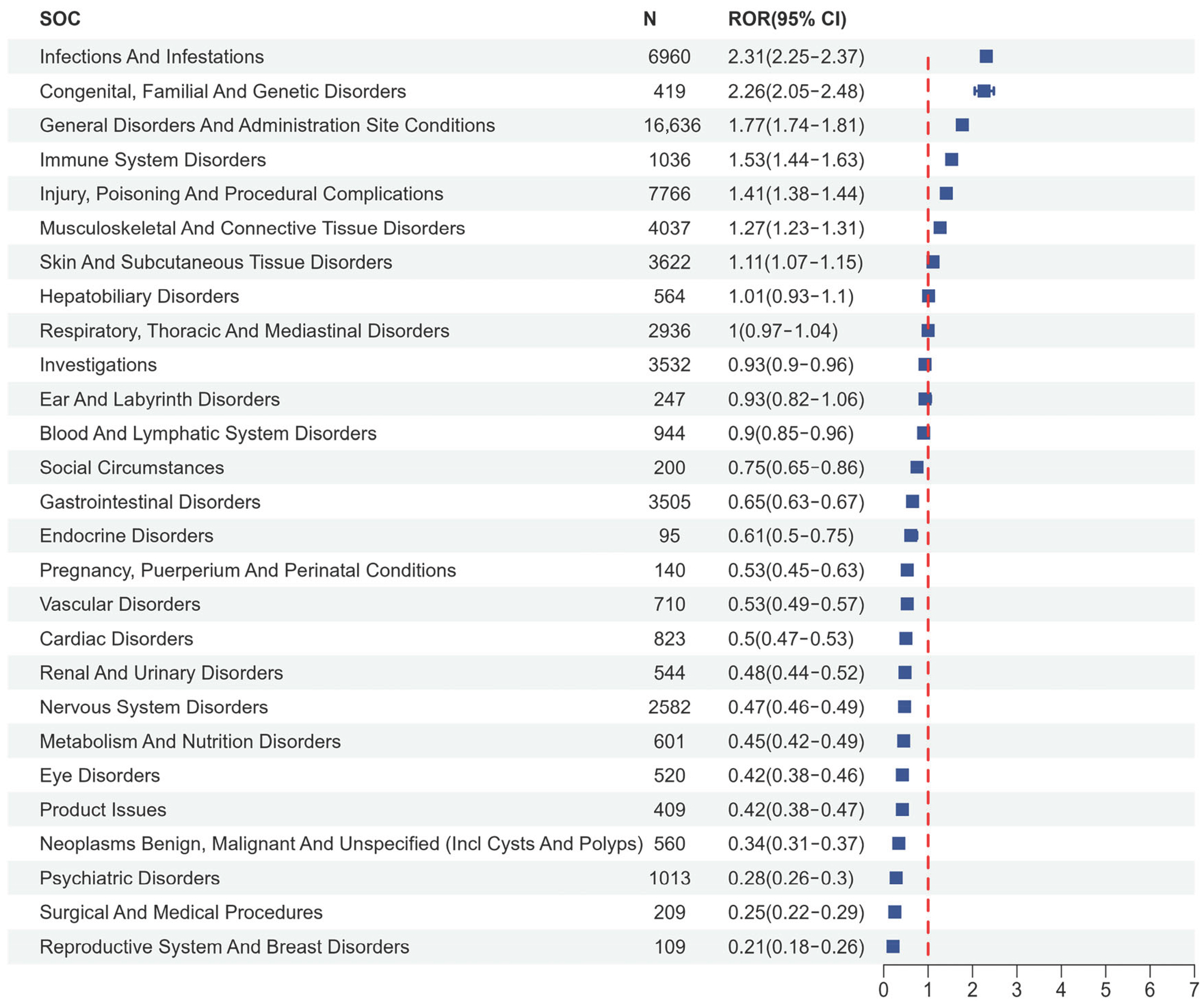

2.2. Disproportionality Analysis

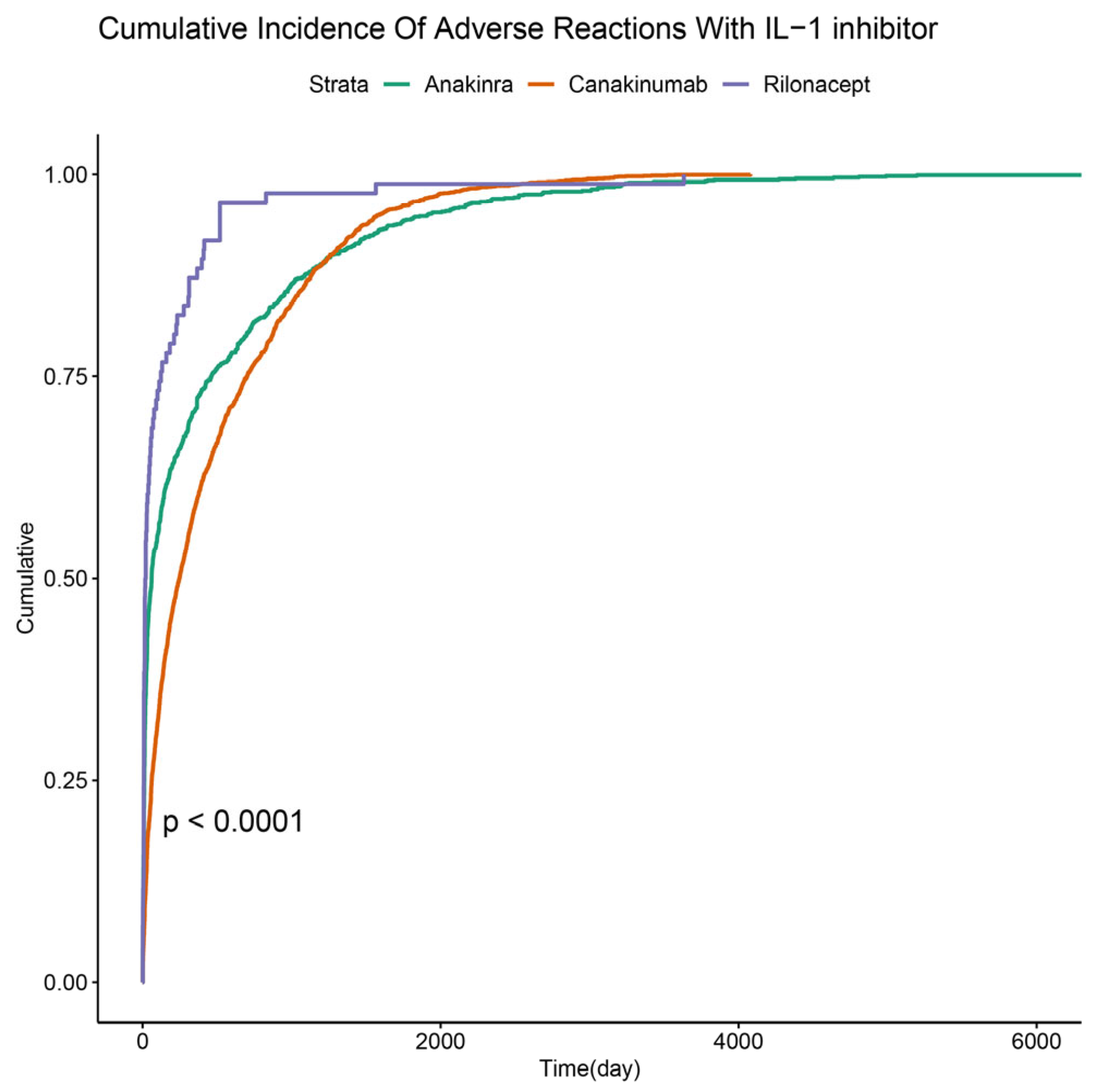

2.3. Time to Onset of IL-1 Inhibitor-Related AEs

3. Discussion

3.1. Reporting Trends in the Context of Drug Lifecycles

3.2. Mechanistic Correlates of Signal Disproportionality of IL-1 Inhibitors: Risk of Infection

3.3. Limitations and Future Directions

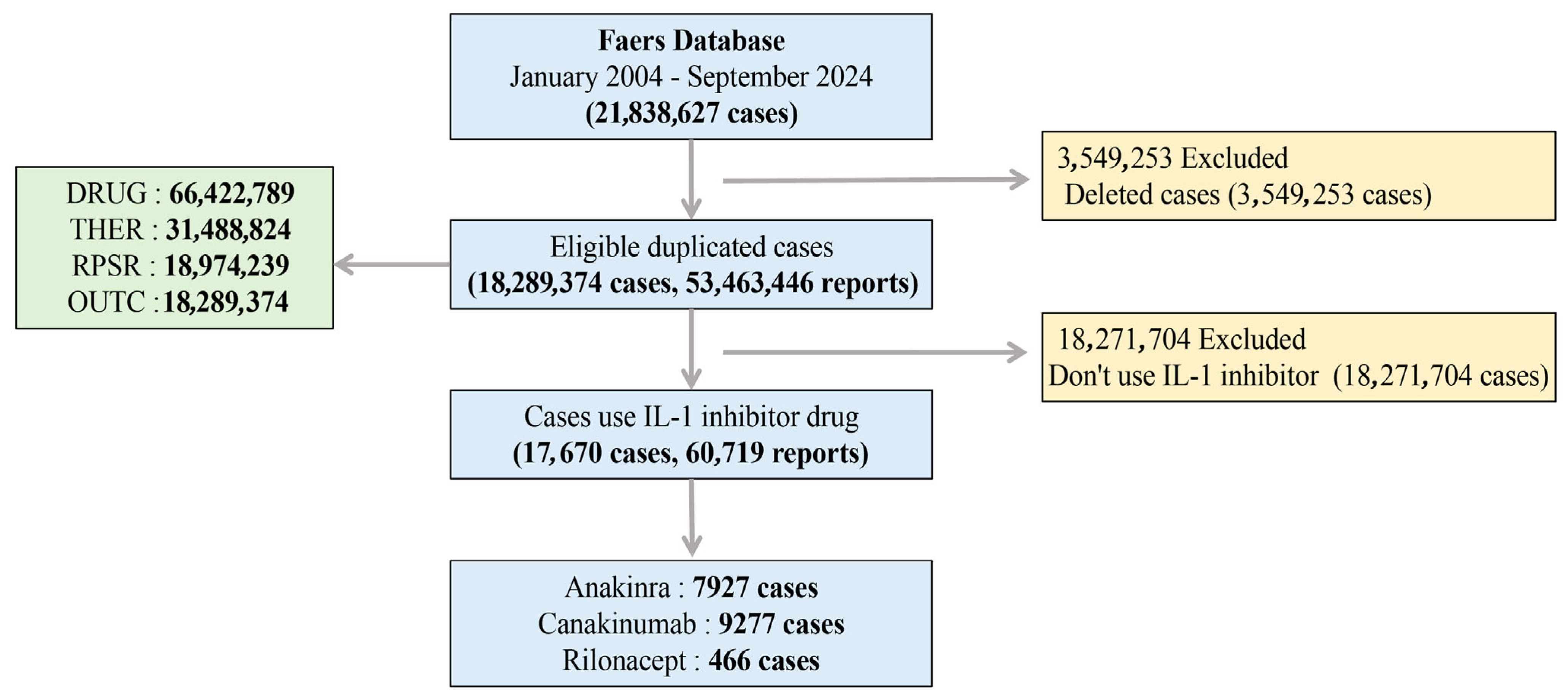

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Data Sources

4.2. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AEs | Adverse Events |

| BCPNN | Bayesian Confidence Propagation Neural Network |

| CAPS | Cryopyrin-Associated Periodic Syndromes |

| DEMO | Demographic and Administrative Information |

| DRUG | Drug Information |

| FAERS | FDA Adverse Event Reporting System |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| IL-1 | Interleukin-1 |

| IL-1R1 | IL-1 Receptor Type 1 |

| INDI | Indications for Drug Administration |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| MedDRA | Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities |

| MGPS | Multi-item Gamma Poisson Shrinker |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor-Kappa B |

| OUCT | Patient Outcomes Information |

| PRR | Proportional Reporting Ratio |

| PS | Primary Suspected |

| PT | Preferred Term |

| RA | Rheumatoid Arthritis |

| REAC | Adverse Drug Reaction Information |

| ROR | Reporting Odds Ratio |

| RPSR | Reported Sources |

| SOCs | System Organ Classes |

| sJIA | Systemic Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis |

| THER | Drug Therapy Start Dates and End Dates |

| TRAPS | Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor-Associated Periodic Syndrome |

References

- Dinarello, C.A. Interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis and treatment of inflammatory diseases. Blood 2011, 117, 3720–3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.E.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, W.U. Cytokines, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factors, and PlGF in Autoimmunity: Insights From Rheumatoid Arthritis to Multiple Sclerosis. Immune Netw. 2024, 24, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, V.; Allantaz, F.; Arce, E.; Punaro, M.; Banchereau, J. Role of interleukin-1 (IL-1) in the pathogenesis of systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis and clinical response to IL-1 blockade. J. Exp. Med. 2005, 201, 1479–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Fan, J.; Huang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Weng, R.; Luo, Y.; Yang, J.; He, T. Effectiveness and safety of canakinumab in cryopyrin-associated periodic syndrome: A retrospective study in China. Pediatr. Rheumatol. Online J. 2024, 22, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleischmann, R.M.; Schechtman, J.; Bennett, R.; Handel, M.L.; Burmester, G.R.; Tesser, J.; Modafferi, D.; Poulakos, J.; Sun, G. Anakinra, a recombinant human interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (r-metHuIL-1ra), in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A large, international, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003, 48, 927–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.L.; Imazio, M.; Cremer, P.; Brucato, A.; Abbate, A.; Fang, F.; Insalaco, A.; LeWinter, M.; Lewis, B.S.; Lin, D.; et al. Phase 3 Trial of Interleukin-1 Trap Rilonacept in Recurrent Pericarditis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridker, P.M.; Everett, B.M.; Thuren, T.; MacFadyen, J.G.; Chang, W.H.; Ballantyne, C.; Fonseca, F.; Nicolau, J.; Koenig, W.; Anker, S.D.; et al. Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 1119–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.M.; Kim, W.U. Targeted Immunotherapy for Autoimmune Disease. Immune Netw. 2022, 22, e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imazio, M.; Lazaros, G.; Gattorno, M.; LeWinter, M.; Abbate, A.; Brucato, A.; Klein, A. Anti-interleukin-1 agents for pericarditis: A primer for cardiologists. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 2946–2957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, X.; Chen, L.; Gai, D.; He, S.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, N. Adverse Event Profiles of PARP Inhibitors: Analysis of Spontaneous Reports Submitted to FAERS. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 851246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawelec, G. Working together for robust immune responses in the elderly. Nat. Immunol. 2000, 1, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chi, Z.; Zhang, Z. Real-world data and Mendelian randomization analysis in assessing adverse reactions of rilonacept. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2025, 47, 1365–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Yan, W.; Li, J.; Yan, D.; Luo, D. Post-marketing safety of anakinra and canakinumab: A real-world pharmacovigilance study based on FDA adverse event reporting system. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1483669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, J.; Wang, F.; Huang, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y. Perspectives on anti-IL-1 inhibitors as potential therapeutic interventions for severe COVID-19. Cytokine 2021, 143, 155544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conti, P.; Caraffa, A.; Gallenga, C.E.; Ross, R.; Kritas, S.K.; Frydas, I.; Younes, A.; Ronconi, G. Coronavirus-19 (SARS-CoV-2) induces acute severe lung inflammation via IL-1 causing cytokine storm in COVID-19: A promising inhibitory strategy. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2020, 34, 1971–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradian, N.; Gouravani, M.; Salehi, M.A.; Heidari, A.; Shafeghat, M.; Hamblin, M.R.; Rezaei, N. Cytokine release syndrome: Inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines as a solution for reducing COVID-19 mortality. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 2020, 31, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizk, J.G.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Mehra, M.R.; Lavie, C.J.; Rizk, Y.; Forthal, D.N. Pharmaco-Immunomodulatory Therapy in COVID-19. Drugs 2020, 80, 1267–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachakis, P.K.; Theofilis, P.; Soulaidopoulos, S.; Lazarou, E.; Tsioufis, K.; Lazaros, G. Clinical Utility of Rilonacept for the Treatment of Recurrent Pericarditis: Design, Development, and Place in Therapy. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2024, 18, 3939–3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toki, T.; Ono, S. Spontaneous Reporting on Adverse Events by Consumers in the United States: An Analysis of the Food and Drug Administration Adverse Event Reporting System Database. Drugs Real World Outcomes 2018, 5, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Hernandez, G.; Krallinger, M.; Muñoz, M.; Rodriguez-Esteban, R.; Uzuner, Ö.; Hirschman, L. Challenges and opportunities for mining adverse drug reactions: Perspectives from pharma, regulatory agencies, healthcare providers and consumers. Database 2022, 2022, baac071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitisopee, T.; Assanee, J.; Sorofman, B.A.; Watcharadmrongkun, S. Consumers’ adverse drug event reporting via community pharmacists: Three stakeholder perception. J. Pharm. Policy Pract. 2022, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spahn, C.; Toda, N.; Groat, B.; Aimer, O.; Rogers, S.; Oni-Orisan, A.; Monte, A.; Hakooz, N.; on behalf of the Pharmacogenomics Global Research Network (PGRN) Publications Committee. Transforming Pharmacovigilance With Pharmacogenomics: Toward Personalized Risk Management. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 118, 1286–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, N.; Kurata, M.; Yamamoto, T.; Morikawa, S.; Masumoto, J. The role of interleukin-1 in general pathology. Inflamm. Regen. 2019, 39, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broderick, L.; Hoffman, H.M. IL-1 and autoinflammatory disease: Biology, pathogenesis and therapeutic targeting. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2022, 18, 448–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaRock, C.N.; Todd, J.; LaRock, D.L.; Olson, J.; O’Donoghue, A.J.; Robertson, A.A.; Cooper, M.A.; Hoffman, H.M.; Nizet, V. IL-1β is an innate immune sensor of microbial proteolysis. Sci. Immunol. 2016, 1, eaah3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, K.; Crother, T.R.; Karlin, J.; Chen, S.; Chiba, N.; Ramanujan, V.K.; Vergnes, L.; Ojcius, D.M.; Arditi, M. Caspase-1 dependent IL-1β secretion is critical for host defense in a mouse model of Chlamydia pneumoniae lung infection. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eddens, T.; Kolls, J.K. Host defenses against bacterial lower respiratory tract infection. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2012, 24, 424–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Q.; Wang, X.; Huang, E.; Wang, Q.; Wen, C.; Yang, G.; Lu, L.; Cui, D. Inflammasome and Its Therapeutic Targeting in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 816839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galozzi, P.; Baggio, C.; Bindoli, S.; Oliviero, F.; Sfriso, P. Development and Role in Therapy of Canakinumab in Adult-Onset Still’s Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salliot, C.; Dougados, M.; Gossec, L. Risk of serious infections during rituximab, abatacept and anakinra treatments for rheumatoid arthritis: Meta-analyses of randomised placebo-controlled trials. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2009, 68, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, H.M.; Wanderer, A.A. Inflammasome and IL-1beta-mediated disorders. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2010, 10, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgel, P. Crosstalk between Interleukin-1β and Type I Interferons Signaling in Autoinflammatory Diseases. Cells 2021, 10, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorowski, A. Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: Clinical presentation, aetiology and management. J. Intern. Med. 2019, 285, 352–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voelkel, N.F.; Tuder, R.M.; Bridges, J.; Arend, W.P. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist treatment reduces pulmonary hypertension generated in rats by monocrotaline. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 1994, 11, 664–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trankle, C.R.; Canada, J.M.; Kadariya, D.; Markley, R.; De Chazal, H.M.; Pinson, J.; Fox, A.; Van Tassell, B.W.; Abbate, A.; Grinnan, D. IL-1 Blockade Reduces Inflammation in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension and Right Ventricular Failure: A Single-Arm, Open-Label, Phase IB/II Pilot Study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 199, 381–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zefferino, R.; Di Gioia, S.; Conese, M. Molecular links between endocrine, nervous and immune system during chronic stress. Brain Behav. 2021, 11, e01960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, J.W.; Duman, R.S. IL-1beta is an essential mediator of the antineurogenic and anhedonic effects of stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herman, A.P.; Bochenek, J.; Król, K.; Krawczyńska, A.; Antushevich, H.; Pawlina, B.; Herman, A.; Romanowicz, K.; Tomaszewska-Zaremba, D. Central Interleukin-1β Suppresses the Nocturnal Secretion of Melatonin. Mediat. Inflamm. 2016, 2016, 2589483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrka, A.R.; Parade, S.H.; Valentine, T.R.; Eslinger, N.M.; Seifer, R. Adversity in preschool-aged children: Effects on salivary interleukin-1β. Dev. Psychopathol. 2015, 27, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, L.H.; Lenz, K.M. The immune system as a novel regulator of sex differences in brain and behavioral development. J. Neurosci. Res. 2017, 95, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferri, S.L.; Abel, T.; Brodkin, E.S. Sex Differences in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2018, 20, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Nasir, H.; Moatasim, A.; Khalil, F. Renal Amyloidosis: A Clinicopathological Study From a Tertiary Care Hospital in Pakistan. Cureus 2022, 14, e21122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden, R.A.; Bijzet, J.; Meijers, W.C.; Yakala, G.K.; Kleemann, R.; Nguyen, T.Q.; de Boer, R.A.; Schalkwijk, C.G.; Hazenberg, B.P.; Tietge, U.J.; et al. Obesity-induced chronic inflammation in high fat diet challenged C57BL/6J mice is associated with acceleration of age-dependent renal amyloidosis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, X.; Jia, X.; Zhong, Y. A disproportionality analysis of CDK4/6 inhibitors in the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 2025, 24, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardella, M.; Lungu, C. Evaluation of quantitative signal detection in EudraVigilance for orphan drugs: Possible risk of false negatives. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2019, 10, 2042098619882819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potter, E.; Reyes, M.; Naples, J.; Dal Pan, G. FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) Essentials: A Guide to Understanding, Applying, and Interpreting Adverse Event Data Reported to FAERS. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2025, 118, 567–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Weng, R.; Huang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Yang, J.; He, T. Canakinumab in the treatment of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis: A retrospective single center study in China. Front. Pediatr. 2024, 12, 1349907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Dai, Z.; Song, H.; Zhang, J.; Li, T. Disproportionality analysis of oesophageal toxicity associated with oral bisphosphonates using the FAERS database (2004–2023). Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1473756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Ji, Y.; Zhu, H. Safety assessment of Brexpiprazole: Real-world adverse event analysis from the FAERS database. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 346, 223–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yao, Y.; Wang, M.; Xue, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, F. A real-world drug safety surveillance study from the FAERS database of hepatocellular carcinoma patients receiving durvalumab in combination with tremelimumab. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1657398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Variable | IL-1 Inhibitors | Anakinra | Canakinumab | Rilonacept |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | (N = 17,670) | (N = 7927) | (N = 9277) | (N = 466) | |

| Gender | Female | 10,189 (57.7%) | 5100 (64.3%) | 4815 (51.9%) | 274 (58.8%) |

| Male | 6210 (35.1%) | 2628 (33.2%) | 3461 (37.3%) | 121 (26.0%) | |

| Missing | 1271 (7.2%) | 199 (2.5%) | 1001 (10.8%) | 71 (15.2%) | |

| Age | <18 | 3153 (17.8%) | 1009 (12.7%) | 2133 (23.0%) | 11 (2.4%) |

| 18–65 | 4341 (24.6%) | 2415 (30.5%) | 1720 (18.5%) | 206 (44.2%) | |

| >65 | 1401 (8%) | 766 (9.6%) | 561 (6.1%) | 74 (15.9%) | |

| Missing | 8775 (49.7%) | 3737 (47.1%) | 4863 (52.4%) | 175 (37.6%) | |

| Reporter’s occupation | Consumer (CN) | 9841 (55.7%) | 5243 (66.1%) | 4510 (48.6%) | 88 (18.9%) |

| Health-professional (HP) | 2302 (13.0%) | 426 (5.4%) | 1556 (16.8%) | 320 (68.7%) | |

| Lawyer (LW) | 2 (0.0%) | 2 (0.0%) | |||

| Physician (MD) | 3535 (20.0%) | 1269 (16.0%) | 2226 (24.0%) | 40 (8.6%) | |

| Other health professional (OT) | 1251 (7.1%) | 435 (5.5%) | 811 (8.7%) | 5 (1.1%) | |

| Pharmacist (PH) | 299 (1.7%) | 186 (2.3%) | 104 (1.1%) | 9 (1.9%) | |

| Registered Nurse (RN) | 12 (0.1%) | 8 (0.1%) | 3 (0.0%) | 1 (0.2%) | |

| Missing | 428 (2.4%) | 358 (4.5%) | 67 (0.7%) | 3 (0.6%) |

| Name | SOC Name | PT | n | ROR | PRR | EBGM (EBGM05) | IC (IC025) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (95% Cl) | |||||||

| IL-1 inhibitors | General Disorders and Administration Site Conditions | Pyrexia | 1812 | 5.27 (5.03–5.53) | 5.14 (6050.1) | 5.12 (4.92) | 2.36 (2.29) |

| Condition Aggravated | 1098 | 3.84 (3.61–4.07) | 3.78 (2250.95) | 3.77 (3.59) | 1.92 (1.83) | ||

| Injection Site Pain | 1080 | 3.8 (3.58–4.04) | 3.75 (2183.13) | 3.74 (3.56) | 1.9 (1.82) | ||

| Injection Site Erythema | 744 | 6.09 (5.67–6.55) | 6.03 (3108.52) | 6 (5.64) | 2.58 (2.48) | ||

| Injection Site Pruritus | 542 | 8.31 (7.63–9.04) | 8.24 (3420.51) | 8.17 (7.61) | 3.03 (2.91) | ||

| Injection Site Reaction | 486 | 7.19 (6.57–7.86) | 7.14 (2548.11) | 7.09 (6.58) | 2.83 (2.69) | ||

| Illness | 423 | 5.32 (4.83–5.86) | 5.29 (1465.15) | 5.27 (4.86) | 2.4 (2.26) | ||

| Injection Site Swelling | 346 | 4.75 (4.28–5.28) | 4.73 (1014.18) | 4.71 (4.31) | 2.24 (2.08) | ||

| Injection Site Rash | 340 | 11.93 (10.72–13.28) | 11.87 (3340.06) | 11.72 (10.72) | 3.55 (3.39) | ||

| Injection Site Urticaria | 329 | 14.43 (12.94–16.1) | 14.36 (4025.36) | 14.15 (12.91) | 3.82 (3.66) | ||

| Injection Site Bruising | 316 | 4.16 (3.72–4.64) | 4.14 (749.98) | 4.13 (3.76) | 2.04 (1.88) | ||

| Infections and Infestations | COVID-19 | 698 | 3.92 (3.64–4.23) | 3.89 (1495.24) | 3.88 (3.64) | 1.95 (1.84) | |

| Infection | 462 | 3.29 (3–3.6) | 3.27 (726.81) | 3.26 (3.02) | 1.71 (1.57) | ||

| Nasopharyngitis | 419 | 2.31 (2.1–2.54) | 2.3 (307.88) | 2.3 (2.12) | 1.2 (1.06) | ||

| Influenza | 318 | 3 (2.69–3.35) | 2.99 (420.33) | 2.98 (2.72) | 1.58 (1.41) | ||

| Injury, Poisoning, and Procedural Complications | Off-Label Use | 2793 | 3.56 (3.43–3.7) | 3.44 (4892.7) | 3.44 (3.33) | 1.78 (1.72) | |

| Product Dose Omission Issue | 1028 | 4.66 (4.38–4.95) | 4.6 (2887.51) | 4.58 (4.35) | 2.19 (2.1) | ||

| Inappropriate Schedule of Product Administration | 941 | 6.22 (5.83–6.64) | 6.14 (4030.46) | 6.1 (5.78) | 2.61 (2.51) | ||

| Incorrect Dose Administered | 523 | 2.6 (2.38–2.83) | 2.58 (508.05) | 2.58 (2.4) | 1.37 (1.24) | ||

| Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue Disorders | Urticaria | 406 | 2.51 (2.28–2.77) | 2.5 (365.06) | 2.49 (2.3) | 1.32 (1.18) | |

| anakinra | General Disorders and Administration Site Conditions | Injection Site Pain | 928 | 6.47 (6.06–6.91) | 6.31 (4151.35) | 6.29 (5.96) | 2.65 (2.56) |

| Injection Site Erythema | 641 | 10.36 (9.58–11.2) | 10.16 (5275.45) | 10.11 (9.47) | 3.34 (3.22) | ||

| Pyrexia | 503 | 2.81 (2.58–3.07) | 2.78 (577.24) | 2.78 (2.58) | 1.48 (1.35) | ||

| Injection Site Pruritus | 493 | 14.88 (13.61–16.27) | 14.66 (6229.43) | 14.55 (13.5) | 3.86 (3.73) | ||

| Condition Aggravated | 440 | 2.99 (2.72–3.28) | 2.96 (573.22) | 2.96 (2.73) | 1.56 (1.43) | ||

| Injection Site Reaction | 421 | 12.25 (11.12–13.49) | 12.09 (4258.69) | 12.02 (11.08) | 3.59 (3.44) | ||

| Injection Site Urticaria | 307 | 26.45 (23.62–29.63) | 26.2 (7332.53) | 25.82 (23.49) | 4.69 (4.52) | ||

| Injection Site Swelling | 295 | 7.96 (7.09–8.93) | 7.89 (1769.21) | 7.86 (7.14) | 2.97 (2.81) | ||

| Injection Site Rash | 293 | 20.16 (17.96–22.64) | 19.98 (5224.76) | 19.76 (17.94) | 4.3 (4.13) | ||

| Injection Site Bruising | 283 | 7.31 (6.5–8.22) | 7.25 (1521.31) | 7.23 (6.55) | 2.85 (2.68) | ||

| Illness | 172 | 4.21 (3.63–4.9) | 4.2 (418.25) | 4.19 (3.69) | 2.07 (1.85) | ||

| Infections and Infestations | COVID-19 | 420 | 4.62 (4.2–5.09) | 4.57 (1172.18) | 4.56 (4.21) | 2.19 (2.05) | |

| Infection | 286 | 3.98 (3.55–4.48) | 3.96 (631.74) | 3.95 (3.58) | 1.98 (1.81) | ||

| Sinusitis | 159 | 3 (2.57–3.51) | 2.99 (211.05) | 2.99 (2.62) | 1.58 (1.35) | ||

| Injury, Poisoning and Procedural Complications | Off-Label Use | 2586 | 6.72 (6.45–6.99) | 6.24 (11,494.83) | 6.22 (6.02) | 2.64 (2.58) | |

| Product Dose Omission Issue | 835 | 7.47 (6.98–8.01) | 7.3 (4536.79) | 7.27 (6.87) | 2.86 (2.76) | ||

| Intentional Product Misuse | 239 | 5.37 (4.73–6.1) | 5.34 (840.56) | 5.32 (4.78) | 2.41 (2.22) | ||

| Contusion | 150 | 3.03 (2.58–3.56) | 3.02 (203.25) | 3.02 (2.64) | 1.6 (1.36) | ||

| Musculoskeletal and Connective Tissue Disorders | Rheumatoid Arthritis | 176 | 3.06 (2.64–3.55) | 3.05 (241.99) | 3.04 (2.69) | 1.61 (1.39) | |

| Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue Disorders | Urticaria | 229 | 2.77 (2.43–3.15) | 2.76 (256.44) | 2.75 (2.47) | 1.46 (1.27) | |

| canakinumab | Gastrointestinal Disorders | Abdominal Pain | 253 | 2.35 (2.08–2.66) | 2.34 (194.39) | 2.34 (2.11) | 1.22 (1.04) |

| General Disorders and Administration Site Conditions | Pyrexia | 1291 | 8.26 (7.81–8.73) | 7.92 (7821.15) | 7.89 (7.53) | 2.98 (2.9) | |

| Malaise | 694 | 3.37 (3.13–3.64) | 3.32 (1128.56) | 3.31 (3.11) | 1.73 (1.62) | ||

| Condition Aggravated | 647 | 4.91 (4.54–5.31) | 4.82 (1963.02) | 4.81 (4.51) | 2.27 (2.15) | ||

| Illness | 243 | 6.61 (5.83–7.5) | 6.56 (1143.5) | 6.54 (5.89) | 2.71 (2.52) | ||

| Infections and Infestations | Pneumonia | 339 | 2.3 (2.07–2.56) | 2.29 (245.99) | 2.28 (2.09) | 1.19 (1.03) | |

| COVID-19 | 259 | 3.13 (2.77–3.54) | 3.11 (372.35) | 3.11 (2.81) | 1.64 (1.46) | ||

| Nasopharyngitis | 232 | 2.77 (2.43–3.15) | 2.75 (259.46) | 2.75 (2.47) | 1.46 (1.27) | ||

| Influenza | 187 | 3.82 (3.31–4.41) | 3.8 (385.8) | 3.79 (3.36) | 1.92 (1.71) | ||

| Infection | 166 | 2.55 (2.19–2.97) | 2.54 (154.75) | 2.54 (2.23) | 1.34 (1.12) | ||

| Injury, Poisoning, and Procedural Complications | Inappropriate Schedule of Product Administration | 904 | 13.16 (12.31–14.06) | 12.77 (9761.68) | 12.69 (12) | 3.67 (3.57) | |

| Incorrect Dose Administered | 491 | 5.33 (4.87–5.82) | 5.25 (1690.72) | 5.24 (4.86) | 2.39 (2.26) | ||

| Product Use in Unapproved Indication | 234 | 2.3 (2.02–2.62) | 2.29 (170.84) | 2.29 (2.06) | 1.2 (1.01) | ||

| Musculoskeletal and Connective Tissue Disorders | Arthralgia | 502 | 2.66 (2.43–2.9) | 2.63 (508.46) | 2.62 (2.44) | 1.39 (1.26) | |

| Joint Swelling | 144 | 2.6 (2.21–3.07) | 2.59 (141.1) | 2.59 (2.26) | 1.37 (1.13) | ||

| Respiratory, Thoracic, and Mediastinal Disorders | Cough | 304 | 2.38 (2.13–2.67) | 2.37 (240.56) | 2.36 (2.15) | 1.24 (1.08) | |

| Oropharyngeal Pain | 147 | 3.42 (2.91–4.03) | 3.41 (250.45) | 3.41 (2.97) | 1.77 (1.53) | ||

| Rhinorrhea | 137 | 4.68 (3.96–5.54) | 4.66 (393.85) | 4.66 (4.04) | 2.22 (1.97) | ||

| Skin and Subcutaneous Tissue Disorders | Rash | 454 | 2.33 (2.12–2.55) | 2.3 (337.37) | 2.3 (2.13) | 1.2 (1.07) | |

| rilonacept | General Disorders and Administration Site Conditions | Injection Site Erythema | 67 | 21.13 (16.54–26.99) | 20.29 (1230.81) | 20.28 (16.53) | 4.34 (3.98) |

| Injection Site Pain | 44 | 5.86 (4.34–7.9) | 5.73 (172.41) | 5.73 (4.46) | 2.52 (2.08) | ||

| Chest Pain | 42 | 8.44 (6.21–11.46) | 8.24 (268.11) | 8.24 (6.38) | 3.04 (2.6) | ||

| Injection Site Reaction | 34 | 19.01 (13.54–26.71) | 18.64 (567.75) | 18.63 (14.02) | 4.22 (3.73) | ||

| Injection Site Rash | 29 | 38.26 (26.49–55.24) | 37.59 (1032.11) | 37.55 (27.61) | 5.23 (4.7) | ||

| Injection Site Pruritus | 25 | 14.37 (9.68–21.34) | 14.16 (306.07) | 14.16 (10.17) | 3.82 (3.25) | ||

| Injection Site Mass | 22 | 23.03 (15.12–35.08) | 22.73 (456.92) | 22.71 (15.97) | 4.51 (3.9) | ||

| Chest Discomfort | 20 | 7.47 (4.81–11.61) | 7.39 (110.68) | 7.39 (5.11) | 2.89 (2.25) | ||

| Injection Site Hemorrhage | 15 | 7.25 (4.36–12.06) | 7.19 (80.08) | 7.19 (4.7) | 2.85 (2.12) | ||

| Injection Site Swelling | 14 | 7.21 (4.26–12.21) | 7.16 (74.28) | 7.16 (4.61) | 2.84 (2.09) | ||

| Injection Site Bruising | 12 | 5.92 (3.35–10.45) | 5.88 (48.69) | 5.88 (3.66) | 2.56 (1.75) | ||

| Chills | 12 | 3.77 (2.14–6.65) | 3.75 (24.21) | 3.75 (2.33) | 1.91 (1.1) | ||

| Injection Site Warmth | 12 | 21.01 (11.9–37.07) | 20.86 (226.81) | 20.85 (12.96) | 4.38 (3.58) | ||

| Illness | 8 | 3.75 (1.87–7.52) | 3.74 (16.08) | 3.74 (2.09) | 1.9 (0.94) | ||

| Injection Site Urticaria | 8 | 12.98 (6.48–26) | 12.92 (87.99) | 12.92 (7.22) | 3.69 (2.73) | ||

| Infections and Infestations | COVID-19 | 19 | 4 (2.54–6.28) | 3.96 (42.19) | 3.96 (2.71) | 1.99 (1.34) | |

| Injury, Poisoning, and Procedural Complications | Product Dose Omission Issue | 55 | 9.49 (7.25–12.41) | 9.2 (403.2) | 9.19 (7.34) | 3.2 (2.81) | |

| Nervous System Disorders | Hypoaesthesia | 15 | 3.69 (2.22–6.13) | 3.66 (29.07) | 3.66 (2.39) | 1.87 (1.15) | |

| Product Issues | Product Complaint | 9 | 15.3 (7.94–29.46) | 15.22 (119.56) | 15.21 (8.79) | 3.93 (3.01) |

| Target Adverse Drug Event | Other Adverse Drug Event | Sums | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1 inhibitors (anakinra, canakinumab, rilonacept) | a | b | a + b |

| Other drugs | c | d | c + d |

| Sums | a + c | b + d | a + b + c + d |

| Method | Equation | Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| ROR | ROR = ROR 95%CI = eln(ROR) ± 1.96 | lower limit of 95% CI > 1, N ≥ 3 |

| PRR | PRR = PRR 95%CI = eln(PRR) ± 1.96 χ2 = [(ad − bc)^2](a + b + c + d)/[(a + b)(c + d)(a + c)(b + d)] | lower limit of 95% CI > 1, N ≥ 3 |

| BCPNN | IC = log2 IC025 = eln(IC) − 1.96 | IC025 > 0 |

| MGPS | EBGM = EBGM05 = eln(EBGM) ± 1.96 | EBGM05 > 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lei, J.; Lou, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Cui, Y.; Li, S.; Hu, J.; Jing, Y.; Yang, J. Disproportionality Analysis of Adverse Events Associated with IL-1 Inhibitors in the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1827. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121827

Lei J, Lou Z, Jiang Y, Cui Y, Li S, Hu J, Jing Y, Yang J. Disproportionality Analysis of Adverse Events Associated with IL-1 Inhibitors in the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(12):1827. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121827

Chicago/Turabian StyleLei, Jingjing, Zhuoran Lou, Yuhua Jiang, Yue Cui, Sha Li, Jinhao Hu, Yeteng Jing, and Jinsheng Yang. 2025. "Disproportionality Analysis of Adverse Events Associated with IL-1 Inhibitors in the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS)" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 12: 1827. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121827

APA StyleLei, J., Lou, Z., Jiang, Y., Cui, Y., Li, S., Hu, J., Jing, Y., & Yang, J. (2025). Disproportionality Analysis of Adverse Events Associated with IL-1 Inhibitors in the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS). Pharmaceuticals, 18(12), 1827. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18121827