Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Identifies three core technological pillars in smart furniture—data collection (sensors), transmission/processing (IoT), and actuation—with health monitoring as the dominant application.

- Reveals a pre-commercial gap; 37% of prototypes were validated only in laboratory settings, 20% exclusively through user testing, and just 23% underwent both types of validation. Only one study achieved TRL 9 and is already commercialised.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Urges participatory design: Highlights the need for co-creation with end-users to bridge the gap between prototypes and market-ready solutions.

- Calls for standardisation: Emphasises ethical data governance and interoperable frameworks to enable scalable, context-aware smart furniture systems.

Abstract

Smart furniture represents a growing field that integrates Internet of Things (IoT), embedded systems and assistive technologies, yet lacks a comprehensive synthesis of its components and applications. This PRISMA-guided systematic review analysed 35 studies published between 2014 and 2024, sourced from PubMed, Web of Science and Scopus. The included studies presented prototypes of smart furniture that used IoT, sensors or automation. The focus was on extracting data related to technological configurations, functional uses, validation methods, maturity levels and commercialisation. Three technological pillars emerged, data collection (n = 31 studies), transmission/processing (n = 30), and actuation (n = 22), often combined into multifunctional systems (n = 14). Health monitoring was the dominant application (n = 15), followed by environmental control (n = 8) and assistive functions for older adults (n = 8). Validation methods varied; 37% relied solely on laboratory testing, while 20% only involved end-users. Only one solution surpassed Technology Readiness Level (TRL) 7 and is currently on the market. Current research remains pre-commercial, with gaps in AI integration, long-term validation, and participatory design. Smart furniture shows promise for healthcare and independent living, but requires standardised evaluation, ethical data practices, and co-creation to achieve market readiness.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, technology has revolutionised the way of life and the range of choices, especially with the emergence of autonomous and semi-intelligent devices [1]. Therefore, furniture needs to keep pace with changes in user expectations, becoming smarter and more interactive to suit our modern spaces [1,2]. The combination of the Internet of Things (IoT), environmental intelligence and Human-Centred design (HCD) is transforming furniture from simple objects into dynamic and interactive systems.

With the advent of Industry 4.0, advanced digital technologies such as the IoT are being integrated into manufacturing, creating environments where devices, appliances and users can communicate effortlessly [3]. These innovations are becoming a staple in smart homes, where everyday items are equipped with sensors, remote controls and intelligent systems. In this perspective, smart furniture is defined as “furniture designed and networked, equipped with an intelligent system or controlled by the user’s data and energy sources” [4]. This type of furniture utilises sensors and actuators to interact with users and anticipate their needs, all to improve quality of life in a connected and intelligent world [5,6].

The ageing of the global population is also an important factor driving the development of smart furniture [7]. As people age, they often face physical and cognitive challenges that can make everyday tasks more difficult and increase the risk of injury, especially falls [8]. Smart furniture can play a crucial role in helping older people maintain their independence, improve their quality of life and encourage active and healthy ageing by addressing some of the challenges that accompany this demographic shift [7]. Instead of relying on specialised or stigmatising products aimed solely at older people, it is possible to incorporate assistive features into ordinary furniture following universal design principles. This approach enhances everyday usability without drawing attention to age-related limitations.

Smart furniture can be effectively leveraged to support active and healthy ageing not only in domestic environments, but also in professional and public contexts. Several studies [9] have demonstrated that ICT solutions, such as sensors, actuators, reminders, and activity tracking systems, integrated into furniture can enhance autonomy, well-being, and participation among older adults. These systems are most effective when designed with the user’s specific needs and contexts in mind. In both home and workplace settings, smart furniture has demonstrated utility in promoting cognitive stimulation, improving postural health, and reducing risks related to physical inactivity or falls. This underscores the importance of developing adaptable, context-aware solutions that respond to the realities of ageing populations across different life domains, moving beyond the home and into the broader ecosystem of daily life.

Although there is growing interest in technology-enhanced furniture that makes everyday life easier, development in this area faces some difficult challenges. A major obstacle is the lack of standardised methods to guide the process from design to implementation, which leads to fragmented solutions that often lack consistent usability, safety, and interoperability [4]. Although approaches such as HCD are suggested, their use in industrial contexts is still quite limited and slow to be adopted [10]. Furthermore, the addition of data-driven functionalities raises important questions about privacy and cybersecurity, especially when untrustworthy stakeholders are part of the development process.

As interest in smart furniture continues to grow, there is still a notable gap in comprehensive analyses that thoroughly examine the technologies, functionalities, and applications of these innovations. This systematic review aims to fill that gap by addressing the following questions: What types of integrated technologies were applied to smart furniture prototypes between 2014 and 2024, and what were their functions? How were they evaluated in terms of development maturity, validation and commercialisation? The review compiles the current state of research on smart furniture, providing insights into this evolving field by mapping existing technologies and their uses. In doing so, it hopes to serve as a valuable resource for researchers, designers, and industry professionals.

In this review, “technology” refers to embedded physical components or digital systems integrated into furniture, designed to (1) collect data (e.g., sensors); (2) process/transmit information (e.g., microcontrollers, networks); or (3) execute physical/digital actions (e.g., actuators, robotics). Software algorithms or non-electronic materials are excluded unless directly implemented in hardware.

This review makes key contributions to the field of smart furniture and sensor-based systems. First, it offers a comprehensive synthesis of technological configurations across 35 prototypes, identifying three core pillars, data collection, transmission/processing, and actuation, and mapping their integration into multifunctional systems. Second, it introduces an assessment of TRLs, highlighting the pre-commercial status of most solutions and the methodological gaps that hinder scalability. Third, it draws attention to the lack of participatory design, underscoring the need for inclusive and standardised development frameworks. By bridging technical analysis with implementation challenges, this review provides a valuable resource for researchers, designers, and industry stakeholders aiming to advance smart furniture from concept to market.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This systematic review followed the model proposed by the Joanna Briggs Institute, PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) strategy for systematic literature reviews [11]. Researchers first defined the scope of the study and established the eligibility criteria, with a focus on integrating technologies in smart furniture. While not prospectively registered in PROSPERO, the full protocol (including search strings and data extraction forms) is available in Appendix A.

2.2. Data Sources and Search Strategy

A comprehensive search was conducted in PubMed, Web of Science (WoS), and Scopus covering the period from January 2014 to December 2024. The search string included terms such as “smart furniture”, “IoT”, “Ambient Assisted Living”, and “health monitoring”, combined with Boolean operators. The search strategy for each database is provided in Appendix A.1 (Table A1).

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

The eligibility criteria for this systematic review were established to include studies specifically focused on the integration of technologies into smart furniture. The aim was to identify the types of technologies employed, their functional roles, and their level of technological maturity. Studies were selected based on their relevance to the development and validation of smart furniture prototypes, with particular attention to applications in health, well-being, and ambient assisted living. The exclusion of non-English articles was defined a priori to ensure consistency in data extraction and avoid potential translation bias. To enhance transparency and reproducibility, the inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Eligibility Criteria for Study Inclusion and Exclusion.

Studies published between 2014 and 2024 were prioritised due to the technological maturity of IoT and the relevance of application contexts (e.g., smart cities and homes). Conference papers were included to ensure the representation of practical, albeit preliminary, solutions, thereby complementing more in-depth analyses from journal articles.

2.4. Article Search and Selection

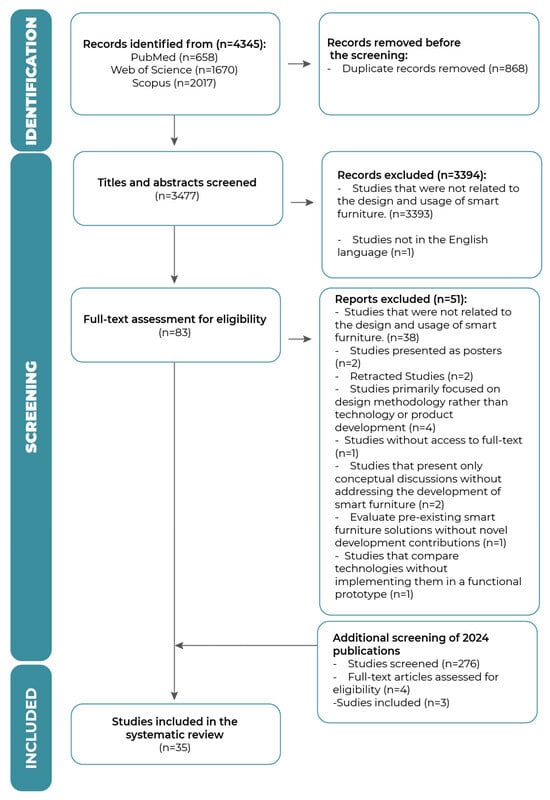

After searching the databases, the articles found were exported to the Rayyan software [12], where duplicates were removed. The articles were then analysed (Rayyan AI was used in blind screening mode) by titles, abstracts, and full text by two reviewers, IM and MB, who applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by a third reviewer, EC. The entire selection process is illustrated in a PRISMA flowchart (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the study inclusion and exclusion process.

2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data were extracted using a standardised form, which included the following categories: Type of publication (e.g., journal article, conference paper); Year; Region/Country where the study was conducted; Technology Used; Technology Function; Furniture Typology; Smart Furniture Functions; Type of Data Collected; Validation Process; Technology Readiness Levels (TRL); Information about Commercialisation. Furthermore, additional data related to technologies or creation processes were also analysed and integrated into the discussions. A narrative synthesis was performed to summarise the findings, focusing on trends, patterns, and gaps in the literature. Where applicable, quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics, and results were presented in tables and figures to facilitate comparison across studies.

2.6. Validity Assessment

To control the reliability and validity of the 35 [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47] selected studies, the technological level of each solution was analysed using the TRL scale (NASA/EC standards). As this is applied research on smart furniture, the studies included were evaluated based on their stage of development, rigour of validation and applicability in the real world. For each study, the degree of maturity was classified using the following levels: TRL Level 7–9 (High Maturity): Systems that have been validated in an operational (industrial) environment/tested by end users themselves (large-scale prototypes, demonstrators). TRL 4–6 (Moderate Maturity): Prototypes tested in laboratories or other controlled environments and some field tests (e.g., user studies, some field trials). TRL 1–3 (Low Maturity): Conceptual designs, calculations, or proof of concept in the laboratory. To avoid the risk of bias, two authors (IM and MB) individually assigned a TRL for inclusion in the high TRL forecast, based on how the validation had been reported (experimentally, user testing, or scalability). Differences were discussed with a third author (LA) using the methods and results of the original study.

2.7. Use of Generative Artificial Intelligence

During the preparation of this manuscript, we employed generative AI tools (ChatGPT-4 and DeepSeek-V3.2) to assist with three key aspects of our research: initial text generation for certain sections, refining our study design through iterative questioning about potential improvements, and exploring data correlations in the systematic review. Importantly, all AI-generated suggestions underwent rigorous human evaluation and were substantially reworked by the authors to ensure accuracy and alignment with our standards. The final manuscript represents our original academic work, with AI serving solely as a supplemental tool for ideation and analysis refinement.

3. Results

In the selection process, a total of 4621 records were found in the Web of Science, PubMed, and Scopus databases, covering the years 2014 to 2024. This period was chosen to ensure that both the most recent advances and previous contributions in the field could be captured. Following the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews, two researchers (IM and MB) independently carried out the screening process. In the second phase, 87 full articles were evaluated for eligibility. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 52 studies were excluded, resulting in a final selection of 35 articles for data extraction and synthesis (see Table A2, Appendix A.2).

3.1. Study Characteristics

The studies analysed came primarily from conference papers (n = 21) [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44], while a smaller number were journal articles (n = 14) [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,31,32,45,46,47]. These papers were published between 2014 and 2024, with a notable spike in activity in 2020 when (n = 7) [14,18,29,30,31,32,33] studies were published.

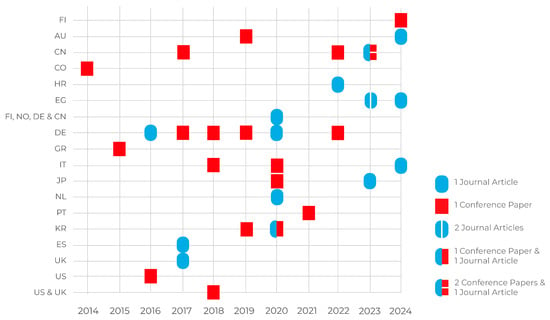

Geographically, the research was conducted primarily in Germany (n = 6) [16,18,26,35,40,42], followed by China (n = 5) [19,23,24,27,38], the Republic of Korea (n = 3) [30,31,37], Italy (n = 3) [20,33,39], Egypt (n = 3) [21,46,47], Japan (n = 2) [13,29], Australia (n = 2) [34,45], and a few other countries that contributed one study each, Colombia [43], Croatia [25], Greece [44], the Netherlands [14], Portugal [28], Spain [17], the United Kingdom [15], and the United States. We also found two international collaborations: one between researchers from the UK and the US [36], and another involving teams from Finland, Norway, Germany, and China [32], as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Study characteristics: year, country and type of publication.

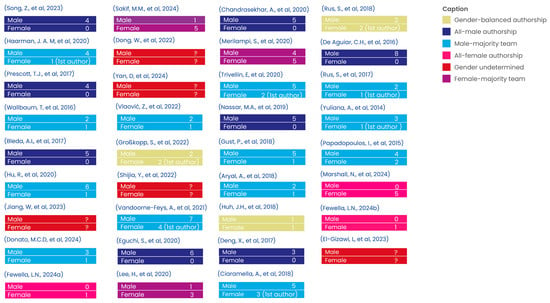

When analysed closely, the authorship patterns across the 35 studies revealed some significant gender imbalances in who was contributing to smart furniture research. As observed in Figure 3., the majority of authorship teams were male-dominated (n = 21) [13,14,15,16,17,18,20,25,28,29,31,33,34,35,37,38,40,41,42,43], with eight studies [13,15,17,29,31,33,37,40] written entirely by men. On the other hand, gender-balanced teams (n = 3) [26,36,39] and those with a majority of female authors (n = 3) [22,30,32] were quite rare. Only two studies [21,46] had a female independent author. There was only one study [45] in which the group of authors consisted exclusively of women. This trend continued when we examined first authors, where male first authors (n = 18) [13,15,16,17,18,20,22,25,29,30,31,32,34,35,36,38,41,44] outnumbered female first authors (n = 12) [14,21,24,26,28,33,39,40,42,43,45,46] by almost two to one. In five cases [19,23,24,27,47], we were unable to determine the gender of all the authors due to unclear names or missing information.

Figure 3.

Study characteristics: Gender and authorship [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47].

3.2. Technologies Identified in Smart Furniture

The review of the 35 studies included in this analysis revealed a diverse range of technological components that are part of smart furniture systems, listed here by frequency of occurrence. The most commonly used were Arduino microcontrollers and Raspberry Pi single-board computers, closely followed by load cells, RFID/NFC systems, and Bluetooth modules. A variety of environmental sensors were also prevalent, covering aspects such as temperature, humidity, air quality, light, and moisture levels.

Furthermore, various types of force and pressure sensors (such as FSR, capacitive sensors, and load cells), along with motion and proximity sensors (including ultrasonic, PIR, infrared, and radar), were frequently mentioned. Other common components included Zigbee and WiFi wireless modules, electrocardiogram (ECG) sensors, photoplethysmographic (PPG) sensors, thermistors, and optical fibre sensors.

Actuation and feedback technologies were also part of the mix, featuring servo motors, linear actuators, LED matrices, LCD displays, and voice recognition modules (like Baidu Voice Assistant and the LD3320 chip). Additionally, some studies integrated Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning elements, such as convolutional neural networks, decision trees, random forests, support vector machines (SVM), and Naive Bayes algorithms. Cloud computing platforms and robotic components—like mobile bases and robotic arms—were also utilised.

On a less frequent note, some studies made use of triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs), Leap Motion controllers, Xbee RF modules, and programmable logic controllers (PLCs). A handful of technologies were only mentioned in single studies, including April tags, Kinect motion sensors (Microsoft Corporation, WA, USA), thermal cameras, reactive-ion etching (RIE) systems, Hetai HT66F2390 microcontrollers (Holtek Semiconductor Inc., Hsinchu, Taiwan), ATK-AS608 fingerprint modules, HC-SR501 human body sensors, M38 Bluetooth audio receivers, 5W power amplifier modules, and specialised deep learning chips for voice recognition.

To provide a clearer overview of the technological configurations and their application domains, Table 2 presents a structured summary of the furniture types, integrated technologies, and their functional roles across the selected studies.

Table 2.

Reference, Type of Furniture, Type of Technology, Application.

3.3. Technological Roles

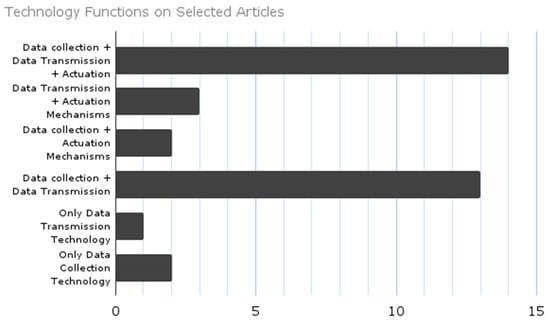

The analysis revealed three key categories of technological components that were integrated across the studies: sensor systems for gathering data (n = 31) [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,21,22,23,24,25,26,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47] technologies for data transmission and processing (n = 30) [14,16,17,18,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,45,46,47], and actuation mechanisms that handle physical and/or digital outputs (n = 22) [14,15,16,17,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,35,36,37,43,44,45,46,47]. When it comes to how these components were put together, the studies showed a variety of configurations. Specifically, we discovered: Studies that utilised only data collection technologies (n = 2) [13,19]; Studies that focused solely on data transmission/processing technologies (n = 1) [20]; Studies that combined data collection with transmission/processing technologies (n = 13) [15,18,21,32,33,34,38,39,40,42,45,46,47]; Studies that merged data collection with actuation mechanisms (n = 2) [35,44]; Studies that integrated transmission/processing technologies with actuation mechanisms (n = 3) [27,28,29]; Studies featuring fully integrated systems that included all three categories of technologies (n = 14) [14,16,17,22,23,24,25,26,30,31,36,37,41,43] (see Figure 4). This classification not only underscores the popularity of sensor-based approaches but also points to a growing trend towards multifunctional, interconnected smart furniture systems.

Figure 4.

Distribution of technology functions across selected articles. Three core categories of technology functions were assessed: sensor systems for data collection, data transmission and processing technologies, and actuation mechanisms enabling physical and/or digital outputs.

3.4. Furniture Types and Application Domains

The studies analysed showed a variety of furniture types that have been adapted for smart functionalities. This included a range of items such as tables (n = 7) [14,15,16,22,26,43,47] sofas (n = 5) [19,23,24,40,42] chairs (n = 3) [29,33,43], mirrors (n = 4) [21,32,38,46], desks (n = 3) [28,31,36], outdoor furniture (n = 4) [33,34,39,45], bedside tables (n = 2) [17,27], beds (n = 2) [17,18], office chairs (n = 2) [25,35], and cabinets (n = 2) [30,37]. There were also unique pieces like armchairs (n = 1) [17], kitchen cabinets and dining furniture (n = 2) [18,41], drawer units (n = 2) [21,46], and main entrance pieces (n = 1) [44]. On top of that, two studies [13,20] introduced modular technologies that can be added to existing furniture, allowing it to gain smart features without needing entirely new smart furniture. Throughout these studies, the smart furniture systems were crafted to fulfil six main functional roles through their built-in technologies. The most prevalent application was health and well-being monitoring (n = 15) [14,17,18,19,21,22,23,24,25,32,35,36,40,42,47], which included features like posture correction and tracking physiological parameters. Environmental monitoring, which covers activities such as tracking ambient conditions and detecting earthquakes, was noted in (n = 8) studies [13,19,20,33,34,38,39,45]. Functions aimed at assisting specific age groups, such as anticipating dangerous situations or encouraging physical activity, also appeared in (n = 8) studies [15,17,18,22,24,32,41,47]. Enhancing social interaction, especially through non-verbal communication, was another focus in (n = 7) studies [14,16,21,22,23,26,45]. Workspace adaptability, such as desks with reconfigurable height, was highlighted in (n = 5) systems [25,28,35,36,38]. Lastly, tools for improving efficiency and managing daily life, including organisational support, were integrated into (n = 11) smart furniture solutions [15,27,29,30,31,37,38,41,43,44,46].

3.5. Technology Validation

The studies showed quite a bit of variation in how they validated their findings, and we can break them down into three main categories. The most popular method was experimental testing, with (n = 13) studies relying solely on this method [13,14,19,20,22,28,29,31,34,35,39,46,47], which usually took place in labs. These studies focused on validating prototypes by checking their structural integrity, conducting load tests, and evaluating technical performance, like how accurate the sensors were and how responsive the systems were under controlled conditions.

Only seven studies (n = 7) [24,26,32,40,41,42,45] relied solely on user validation, conducting pilot studies with end-users, Wizard-of-Oz (WOZ) techniques, scenario-based focus groups, and post-deployment surveys to gauge usability and relevance in real-life situations. Interestingly, (n = 8) studies [16,17,21,25,27,30,33,36] used a hybrid validation framework, blending the thoroughness of technical testing with user-focused assessments. This combination allowed for a more rounded evaluation by merging lab-based analyses with feedback from current users. However, there was a significant gap, (n = 7) [15,18,23,37,38,43,44] studies did not clearly outline their validation processes, which makes it harder to assess the transparency and reproducibility of their results.

3.6. Technology Maturity Assessment

The assessment of the TRL of the studies considered in this systematic review showed an interesting picture of the development phase of the smart furniture solutions investigated. The distribution of TRLs illustrated that most technologies (85,7%) are at intermediate TRL levels (TRL 4–6)—functional prototypes tested in controlled or laboratory environments, without having been extensively tested in real applications. Two studies [18,20] reached TRL 7, proving to be in the pre-commercial phase, having established industrial collaborations. No studies were conducted at TRL 8, and only one study [45] reached TRL 9, highlighting a significant communication gap between the bench scale and the product on the market. The analysis of application categories revealed that those related to health and well-being, especially for older adults, show greater technological maturity (average TRL 6). On the other hand, more innovative applications, such as emotional smart furniture and future home automation, show lower maturity (average TRL 4). It is also interesting that most of the projects with higher TRL (≥6) have important methodological aspects in common: (1) iterative design; (2) validation with end users; and (3) integration with existing technological platforms (e.g., IoT, digital health systems). All these factors seem to contribute strongly to accelerating the maturity of the solutions.

Table 3 summarises the publication type, country of origin, validation method, TRL classification, and commercialisation status of each study, offering a comparative view of technological maturity and implementation potential.

Table 3.

Reference, Publication Type, Country, Year, Validation, TRL, Commercialisation.

3.7. Commercialisation

The systematic review revealed that the vast majority of studies (n = 34) focused exclusively on prototypes or developments in the conceptual phase. Only one study [45] evaluated a commercially available product. Although a small subset of studies (n = 5) [18,20,21,38,39] mentioned possible commercialisation pathways (registered patents or discussed business plans), these provided insufficient detail on actual market implementation, regulatory approvals, or production scaling. This pattern suggests that the field remains predominantly in the transition phase from research to commercialisation, with limited evidence of real-world implementation.

4. Discussion

This systematic review brings together a full decade of research on smart furniture, highlighting that the field is still in its experimental phase. This can be seen in the fact that there are more conference papers (20 of 35) than journal articles (15 of 35), a trend often observed in rapidly changing technology fields [4,48]. While conference proceedings do not always have the same level of methodological rigour, they allow for the rapid sharing of ideas in areas where technology can quickly become obsolete. Many of the studies focus on prototype innovations, but only a few make it past the proof-of-concept phase—often referred to as the “valley of death” in innovation [49].

The peak in publications occurred in 2020 (n = 7), probably influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic, which changed research priorities and intensified the production of manuscripts in several areas [50]. However, it is not yet known whether the pandemic changed the focus or depth of these studies. When the geographic distribution is examined, it is clear that high-income regions dominate the area—Europe (n = 17) and Asia (n = 10) lead, while only a few studies came from South America (Colombia), Africa (Egypt), Oceania (Australia) or North America (USA). This disparity likely points to differences in funding and infrastructure for technology research [51,52]. Expanding the scope of the databases or including grey literature could help improve representation.

Our analysis revealed a significant gender imbalance in authorship, with male-dominated teams contributing to the majority of studies (n = 21). This disparity aligns with broader trends in STEM fields [53] but has specific implications for smart furniture research. A lack of gender diversity in design teams can inadvertently lead to biased technological development, where products may not adequately address the needs or preferences of all end-users. For instance, solutions aimed at older adults, a demographic with a high proportion of women, may overlook key ergonomic, aesthetic, or usability concerns if female perspectives are underrepresented in the design process. Furthermore, our reliance on inferred gender data due to the absence of self-reporting highlights a need for more transparent demographic reporting in academic publications. Moving forward, fostering inclusive and participatory design practices is not only an ethical imperative but also a crucial step towards creating smart furniture that is truly adaptable and responsive to a diverse user base [54]. These findings are not merely descriptive; they highlight structural gaps in research practices that may influence the inclusivity, relevance, and scalability of smart furniture solutions. By examining geographic and gender-related patterns, this review aims to promote more equitable innovation and encourage future studies to adopt inclusive design frameworks that reflect diverse user needs and contexts.

4.1. Trends and Technological Priorities

The field relies on three key technological components: sensor systems (n = 31) [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,21,22,23,24,25,26,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47], data transmission and processing (n = 30) [14,16,17,18,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,45,46,47] and actuation mechanisms (n = 22) [14,15,16,17,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,35,36,37,43,44,45,46,47]. Many studies are combining these elements, indicating a shift away from autonomous technologies toward more interconnected systems. Sensor systems gather environmental and biometric data, while transmission components facilitate real-time decision-making, and actuators enable responsive interactions. This integration of technologies can enhance interoperability but also risks premature standardisation, which may hinder disruptive innovation [53].

When it comes to data collection, the focus has been on environmental factors (such as temperature and light), biometric information (such as heart rate and posture), and interaction inputs (such as gestures and voice). This supports applications in health monitoring (n = 15) [14,17,18,19,21,22,23,24,25,32,35,36,40,42,47], efficiency management (n = 11) [14,17,18,19,21,22,23,24,25,32,35,36,40,42,47], and environmental control (n = 8) studies [13,19,20,33,34,38,39,45]. However, there is a notable lack of applications targeting social interaction or age-specific needs (both n = 8) studies [15,17,18,22,24,32,41,47], pointing to a bias towards individual performance over collective or assistive use cases [55,56].

While continuous biometric data collection is highly dependent, most studies overlook key issues such as privacy, security, and regulatory standards (like General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA)), raising concerns about data governance and the reliability of these technologies as medical devices [57]. Another significant observation is the trend towards retrofitting: smart features are often added to traditional furniture rather than inspiring entirely new designs. This approach can limit innovation and lead to ergonomic issues (such as increased bulk due to embedded sensors), missing opportunities for more integrated, human-centric solutions like those seen in wearables [58].

4.2. Design, Use Cases, and Contextual Integration

Smart furniture is moving from being just basic structures to becoming interactive elements, both inside our homes (think adaptive chairs) and in public areas (such as solar-powered benches). Unfortunately, the lack of standardised evaluation methods results in a lot of variability between different studies, making comparisons and replication of results difficult [59].

None of the studies has mentioned co-creation or participatory design. In cases where users have been included, their involvement occurs at later stages of development, thereby limiting the potential impact of their contributions. The use of participatory approaches is particularly relevant in contexts involving older people, where usability, accessibility, and user needs must be prioritised from the outset [60,61]. Such approaches can also help prevent the development of unnecessary technologies, which are often driven more by technical feasibility or commercial interests than by clearly defined social or health needs [62]. Furthermore, none of the reviewed studies targeting older adults, a demographic with specific health and usability needs, explicitly reference global policy frameworks such as the WHO’s call for inclusive technology to support healthy ageing [63]. This omission suggests a disconnect between technological development and internationally recognised guidelines, potentially limiting the relevance, scalability, and ethical robustness of these solutions.

Furthermore, the concentration of studies in Europe assumes that technological infrastructures (such as broadband and reliable electricity) are available everywhere, which is not the case. Solutions that rely on constant connectivity or cloud-based AI are unlikely to work well in resource-poor environments [64]. Future research should focus on how to adapt to different contexts, including the use of edge computing and modular designs that can be globally relevant.

4.3. Gaps in Validation and Path to Market

The analysis of validation methods across studies reveals a disjointed methodological approach, shaped primarily by three main trends. First, laboratory testing alone dominates (n = 13) [13,14,19,20,22,28,29,31,34,35,39,46,47], with most studies confined to controlled experiments. Second, human-centred validation remains surprisingly scarce: seven studies [24,26,32,40,41,42,45] rely exclusively on user testing, while eight others [16,17,21,25,27,30,33,36] combine user and experimental testing, yet often overlook critical factors like ergonomic fit and accessibility. Finally, empirical validation is alarmingly limited (n = 7) [15,18,23,37,38,43,44], undermining both reproducibility and real-world applicability. These shortcomings are closely linked to Technology Readiness Level assessments: 5.7% of solutions don’t surpass TRL1–3 (low maturity), 85.7% of solutions stagnate at TRL 4–6 (moderate maturity), while only 8.6% advance to TRL 7–9 (high maturity). Importantly, the limited presence of TRL 9 solutions is not due to selection bias in our review process, but rather reflects the current state of the field. In response to the research question, it is noteworthy that the studies with higher TRLs did not employ mixed-method validation approaches. Rather, they relied solely on either user testing or experimental procedures. This observation suggests that as smart furniture solutions advance in maturity, validation practices may become more streamlined or one-dimensional [65,66]. These findings highlight a notable gap in the validation frameworks applied to smart furniture, indicating a lack of consistency or comprehensiveness in how such technologies are assessed across studies.

This highlights a persistent tendency to focus on technical feasibility, often to the detriment of human factors, which echoes criticisms found in the smart furniture literature [67]. Such an imbalance risks creating systems that do not align with real user needs, even if they perform well in lab environments [68]. For example, healthcare applications designed for older people users reached TRL between 4–6, but hit a roadblock in the pre-commercial stages (TRL 7) due to unresolved issues with scalability and regulatory compliance. Notably, the review found only one commercially available product among 35 studies, despite two patent applications, highlighting a widespread “valley of death” between prototypes and market-ready solutions—a gap compounded by insufficient validation [49]. It is also important to acknowledge that some studies may report only a portion of the validation process, omitting prior stages or contextual details. Such omissions can weaken the reader’s understanding of the overall evaluation framework and obscure the continuity between development and validation phases.

The limited commercial success in this field appears closely linked to these research practices. Broader adoption challenges, including high costs, privacy concerns, and usability hurdles for non-technical users [69], are further complicated by the lack of focus on real-world constraints. On the other hand, the transition from research to commercialisation faces a structural barrier: the disconnect between SMEs and research centres [70,71]. While prototypes achieve TRL 6–7 in controlled environments, their scalability depends heavily on innovation hubs that translate academic solutions into market-ready products.

4.4. Challenges and Future Directions

This review highlights significant challenges faced when in developing and implementing smart furniture, especially for health and wellness applications. Key issues include concerns about data privacy and security, particularly in health monitoring scenarios; the need to integrate technology without compromising aesthetics, which has not yet been sufficiently explored; and the limited involvement of end users in many studies, which may hinder adoption and real-world relevance. To address these challenges, future research should: (1) Adopt participatory design frameworks that involve end users throughout the development process, ensuring that smart furniture genuinely meets their needs, preferences, and ethical standards. (2) Conduct longitudinal validation studies to assess the reliability, durability, and accuracy of sensors over time and across various usage conditions. (3) Investigate culturally adaptable and accessible interaction methods to foster inclusion across different age groups, cognitive abilities, and physical capabilities. (4) Establish clearer reporting standards for technology validation and user evaluation processes. (5) Develop sustainable business models that support the scalability and long-term maintenance of smart furniture systems. (6) Address ethical issues more directly, especially concerning data ownership, informed consent, and surveillance in data-sensitive applications. Thus, highlighting the importance of embedding participatory design approaches throughout the development of smart furniture solutions, particularly when targeting older adults or vulnerable users. Co-creation processes involving end-users can surface privacy concerns early and improve emotional acceptance, usability, and trust in technology. Evidence shows that when older adults are engaged in iterative design cycles, their perceived usefulness and willingness to adopt smart solutions increases substantially. Therefore, participatory methodologies should be considered a foundational element in future developments, ensuring that ethical principles are upheld not only in data management but in the very architecture of smart environments.

By tackling these gaps, future research can help develop smart furniture solutions that are ethically sound, contextually appropriate, and widely adopted [72].

4.5. Limitations of the Review

The inclusion of conference proceedings allowed us to capture emerging innovations and cutting-edge prototypes. However, this may have introduced some variability in the quality of methodologies and depth of reporting, which could impact the overall reliability of certain findings. Despite this limitation, we considered it crucial to include these sources to accurately map the current landscape of this rapidly evolving field. This review did not include patents to maintain methodological integrity. Patent documents often miss the mark when it comes to providing solid empirical data on usability, validation, or human-centric outcomes [73]. While they can shed light on early-stage technological innovations, they often promote unverified commercial claims that can distort systematic synthesis. Looking ahead, future scoping reviews or additional analyses could truly benefit from using patent databases to track innovation trends that go beyond the peer-reviewed literature.

5. Conclusions

This systematic review took a close look at 35 studies published between 2014 and 2024, providing a thorough analysis of the technologies, functionalities, and applications found in smart furniture. The findings show that this field is rapidly evolving, fuelled by technological advancements and a growing responsiveness to user needs, especially in areas related to health and well-being. On the tech side, sensor-based systems were commonly used for tasks like environmental monitoring, biometric data collection and user interaction. Embedded computing platforms are also widely used, with Arduino and Raspberry Pi standing out as popular options. However, despite these advancements, the limited use of artificial intelligence indicates that the field has not fully tapped into predictive and adaptive capabilities, focusing more on data collection than on intelligent responses. The review also points out some exciting applications for ageing populations, such as fall-detection systems and posture-monitoring chairs. Yet, it notes that only seven studies have clear paths to commercialisation, highlighting a significant gap between academic innovation and practical implementation. Geographically, the concentration of studies in Europe raises some concerns about how well these findings can be applied to other regions with different infrastructures and cultural contexts. Methodologically, the fact that 60% of the studies come from conference proceedings reflects the experimental and emerging nature of this field, but it also signals a need for more rigorous, peer-reviewed validation. From this review, three key priorities stand out: 1. Long-term, real-world testing is crucial for moving from lab prototypes to commercially viable products. 2. The need to standardise evaluation frameworks to ensure that solutions can be compared, replicated, and refined based on solid evidence. 3. Human-centred, cross-disciplinary design should steer development by weaving together insights from engineering, design, health sciences, and urbanism. This approach ensures that everything created is not only functional and aesthetically pleasing but also ethically sound.

For smart furniture to grow sustainably, it needs to adopt universal design principles, encourage interoperability among IoT systems, and explore open-source or patent-free models, thereby fostering ecological and inclusive innovation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.M., M.B.-P. and L.A.; methodology, I.M., M.B.-P. and L.A.; investigation, I.M., M.B.-P., L.A. and M.I.M.; writing—original draft preparation, I.M., M.B.-P., L.A. and M.I.M.; writing—review and editing, I.M., M.B.-P., L.A., M.I.M., G.M., I.S., F.J.M.M., J.L. and E.C.; visualisation, I.M.; supervision, E.C.; project administration, E.C.; funding acquisition, E.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was performed in the framework of FITT-NESS, a project financed by the European Union through the Interregional Innovation Investments (Ref. 101180300). This study was also suported by FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia under the grants attributed to Inês Mimoso (2025.01709.BD) and to Maria Inês Morgado (2025.04122.BDANA).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used ChatGPT and DeepSeek for the purposes of generating text, assisting in study design and analysis of results. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

Inês Saavedra and Juliana Louceiro are employed by SHINE2Europe. The remaining authors are affiliated with organisations without commercial or financial interests. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| TRL | Technology Readiness Level |

| HCD | Human-centred Design |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| WoS | Web Of Science |

| AAL | Ambient Assisted Living |

| ECG | Electrocardiogram |

| PPG | Photoplethysmography |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TENG | Triboelectric Nanogenerators |

| PLCs | Programmable Logic Controllers |

| RIE | Reactive-ion etching |

| WOZ | Wizard of Oz |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Search strings and database yields used in the systematic review. Boolean operators (OR/AND) were applied to combine terms across PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus (total initial results: n = 4621).

Table A1.

Search strings and database yields used in the systematic review. Boolean operators (OR/AND) were applied to combine terms across PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus (total initial results: n = 4621).

| Database (Results) | Search String |

|---|---|

| PubMed | (“Smart furniture”[TIAB] OR (IoT[TIAB] AND furniture[TIAB]) OR (“Ambient assisted living”[TIAB] AND furniture[TIAB]) OR (Domotics[TIAB] AND furniture[TIAB]) OR (“Smart Homes”[TIAB] AND furniture[TIAB]) OR (technology[TIAB] AND furniture[TIAB]) OR (“Assistive technology”[TIAB] AND furniture[TIAB]) OR (Ergonomic[TIAB] AND furniture[TIAB] AND technology[TIAB]) OR (furniture[TIAB] AND “health monitoring”[TIAB]) OR (“Ambient intelligence”[TIAB] AND furniture[TIAB])) |

| Web of Science | “Smart furniture” OR (IoT AND furniture) OR (“Ambient assisted living” AND furniture) OR (Domotics AND furniture) OR (“Smart Homes” AND furniture) OR (technology AND furniture) OR (“Assistive technology” AND furniture) OR (Ergonomic AND furniture AND technology) OR (Furniture AND “health monitoring”) OR (“Ambient intelligence” AND furniture) |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Smart furniture” OR (“IoT” AND furniture) OR (“Ambient assisted living” AND furniture) OR (domotics AND furniture) OR (“Smart Home” AND furniture) OR (technology AND furniture) OR (“Assistive technology” AND furniture) OR (ergonomic AND furniture AND technology) OR (furniture AND “health monitoring”) OR (“Ambient intelligence” AND furniture) |

| Total | n = 4621 |

Appendix A.2

Table A2.

Characteristics of the 32 included studies, categorised by type of publication, evidence level, country of publication, technology used, furniture typology (sensors, data transmission, actuation), functional application, data collection, validation method and commercialisation.

Table A2.

Characteristics of the 32 included studies, categorised by type of publication, evidence level, country of publication, technology used, furniture typology (sensors, data transmission, actuation), functional application, data collection, validation method and commercialisation.

| Reference | Year | Type of Pub. | Region/Country | Integrated Technology | Technology Role | Furniture Typology | Smart Furniture Functions | Notes on Smart Furniture Functions | Type of Data Collected | Validation Process | Technology Readiness Levels (TRL) | Info. About Commercialization? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [13] | 2019 | Journal Article | Japan | Ultrahigh-frequency-band radiofrequency identification (RFID) | Data collection | Can be built into existing furniture such as desk, etc | Environment monitoring | Monitoring eathquakes | Observational vibration results from a long-term monitoring earthquakes | Describes the process to validate the system’s functionalities: vibrations from earthquakes (experimental testing) | 6—Tested in controlled environment, but with real data | No |

| [14] | 2019 | Journal Article | Netherlands | Load cell HX711 24-Bit Analogue-to-Digital Converter (ADC) LED | Data collection, Process/transmit information, Execute physical/digital actions | Table | Social interaction and communication, Health and well-being | Sensory Interactive Table that allows to study the eating behaviours and social interaction of people in a social setting | Eating Behaviour Detection: Amount of food consumed by individuals. Monitors water intake. Identifies which foods are eaten first or left untouched. Detects the arrangement of dining items (plates, glasses, pots) on the dining table. Behavioural analysis during meals. Monitoring food and water consumption patterns. | Describes the process to validate the system’s functionalities: Load cells to measures pressure. (experimental testing) | 5—Validated in the laboratory with feeding behaviour tests. | No |

| [15] | 2024 | Journal Article | United Kingdom | APRIL tags Robotic components | Data collection, Execute physical/digital actions | Table | Targeted to older people, Efficiency and Daily Life Management | Cantilever table able to move around by itself, or under user control. | Movement validation metrics Orientation data Relative spatial coordinates | No | 4—Prototype without testing in real scenarios. | No |

| [16] | 2014 | Journal Article | Germany | Raspberry Pi LED Arduino Mega RFID-tags proximity sensor | Data collection, Process/transmit information, Execute physical/digital actions | Table | Social interaction and communication | Table that promotes non-verbal communication between people living over a distance. | User Identification Data Event-Driven Interaction Data | Laboratory observation with usability tasks and questionnaires. lab study in a controlled environment. (experimental testing and user testing) | 5—Tested in a controlled environment with users. | No |

| [17] | 2022 | Journal Article | Spain | Wireless Sensor Networks (WSN) Zigbee modules Microcontrollers Wireless node (AT86RF230) Load cells (LAA-W1) 3-axis accelerometers—ADXL345BCCZ-RL Moisture sensor Magnetic contact sensor Infrared temperature sensors (MLX90614)—temperature sensor Infrared distance sensors (GP2Y0A21YK0F) Passive infra-red (PIR) sensors- presence sensor Light sensor (APDS-9007-020) LED Thermistor (NTCLE100E3103JB0)—temperature sensor Motor actuators | Data collection, Process/transmit information, Execute physical/digital actions | Bed, an armchair and a bedside table | Targeted to older people, Health and well-being | Smart Sensory Furniture that anticipates human needs, inferring a potentially dangerous action of an elderly person living alone at home. | Motion and Presence Detection Monitor user proximity, detect fever anomalies, and infer presence. Detect liquid spills (e.g., urine, water) for hygiene alerts. Measure weight distribution; detect user presence/activity (e.g., falls). Detect furniture tilt/impact (fall detection), monitor bed positioning. Monitor room activity; trigger assistive lighting. Adjust ambient lighting automatically (e.g., nighttime safety). Enable real-time data transmission between nodes and base station. | Two stages process validation: Off-Furniture Tests (Lab Testing); In-Furniture Tests (Real-World Testing) (experimental testing and user testing) | 6—Tested in real environment, but on a small scale | No |

| [18] | 2020 | Journal Article | Germany | Electrocardiogram (ECG) sensors Pressure-sensing mattresses Kinect motion sensors thermal cameras. Cloud-based platform AI-based predictive analytics. Internet of Things (IoT) | Data collection, Process/transmit information | interactive kitchen & dining furniture bed | Health and well-being, Targeted to older people | Furniture that encourages activity and customised healthcare in the context of an ageing society. Monitors health, cognitive and physical activation. | ECG signals, respiration rate, temperature, pressure data Gesture tracking, stand-up counting, Room conditions, light levels, and object positioning | 7—Pilot phase with industrial partners (pre-commercialisation). | Future iterations aim for market deployment through European industries and healthcare providers | |

| [19] | 2020 | Journal Article | China | Optical fibre sensor | Data collection | Sofa | Environment monitoring, Health and well-being | A multifunctional embedded optical fibre system for furniture, enabling light guidance and environmental or user interaction monitoring | Temperature, humidity, and carbon dioxide levels. Detection of sitting duration and stress on the furniture. Monitoring of structural integrity and stress on the 3D-printed components. | Several experiments: Temperature Sensing Experiment; Structural Strength Experiment (experimental testing) | 4—Validated only in the laboratory. | No |

| [20] | 2017 | Journal Article | Italy | Internet of Things (IoT) LoRa, FSK, UWB cloud computing | Process/transmit information | Can be built into existing furniture such as desk, etc | Environment monitoring | Detects earthquakes, signals the presence of individuals and supports rescue operations | Presence detection, environmental monitoring, acceleration data for earthquake detection. | Validated through prototype testing, laboratory experiments, simulations, and UAV-assisted localization tests. (experimental testing) | 7—In operational implementation phase | Ongoing implementation in the VITALITY project; aims for TRL 7 (real operational environment) and future commercialization. |

| [21] | 2018 | Journal Article | Egypt | Motion Sensors: Ultrasonic sensors Microcontroller: Arduino | Data collection, Process/transmit information | Wall-mounted mirror and a drawer unit | Social interaction and communication, Health and well-being | The technologies were chosen to create an interactive piece of furniture that promotes family integration, especially for children with ADHD | User Presence and Height, Behavioural Responses interacted with the furniture and how the lighting responses influenced their behaviour, and user feedback | Prototype Testing using technical testing; User Testing (experimental testing and user testing) | 5—Tested with users (ADHD), but not on a large scale. | Is in the process of being patented, with potential for commercialization in the Egyptian market and beyond. |

| [22] | 2024 | Conference Paper | Finland | IFTTT (If This Then That) Cloud-Based Web Interface, NFC tags | Data collection, Process/transmit information, Execute physical/digital actions | Table | Targeted to older people, Social interaction and communication, Health and well-being | Accessible smart mobile devices available for people with motor or cognitive difficulties (older people, patients with dementia, etc.). They can be used in home or assisted living environments to promote autonomy and simple interaction. | User Interaction, system performance and environmental Data. | The system was validated through functionality testing and practical evaluation. (experimental testing) | 4—Functional prototype, without large-scale testing. | No |

| [23] | 2023 | Conference Paper | China | Artificial Intelligence (AI), Internet of Things (IoT), Bluetooth, Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) algorithm, temperature and sound sensors | Data collection, Process/transmit information, Execute physical/digital actions | Sofa | Social interaction and communication, Health and well-being | Light adjustment, wireless charging, Bluetooth connectivity, mood-based lighting, temperature and sound sensing, entertainment integration integrated in a smart sofa for young people living alone. | User mood, behaviour, sound, temperature, and lighting preferences | No | 3—Without physical prototype or validation | No |

| [24] | 2020 | Conference Paper | China | Deep Learning, Chip for Voice Recognition (LD3320) and sensors for blood pressure, heart rate, body temperature, and blood oxygen monitoring. GPRS Communication, Mechanical Actuators for Electric Motors and Heating Elements | Data collection, Process/transmit information, Execute physical/digital actions | Sofa | Health and well-being, Targeted to older people | Health Monitoring, Voice Control, Massage Function, Heating Function, Childcare Function, Stand-Up Assistance and Autonomous Learning. Integrated into a cognitive smart sofa that uses advanced technologies for autonomous interaction with the user. | Blood pressure, heart rate, body temperature, and blood oxygen levels are collected and stored in the cloud. User Preferences, voice Data for authentication and control purposes, sitting patterns and usage frequency. Assistance with sitting and standing up and massages | The smart sofa was validated through user testing. (user testing) | 4—Limited user testing (no real environment). | No |

| [25] | 2019 | Journal Article | Croatia | Force-sensitive resistors (FSR), capacitive sensors, photoplethysmographic (PPG) electrocardiographic (ECG), radar sensors, and flex sensors connected to IoT, Microcontrollers, Arduino, Raspberry Pi, and ESPino32. | Data collection, Process/transmit information, Execute physical/digital actions | Office chairs | Health and well-being, Work/office spaces | Posture Monitoring Health Monitoring. Activity Recognition Posture Correction Assistive Functions Occupancy Detection. Smart chairs combine sensors, IoT and machine learning to promote occupational health in the workplace. | Monitor sitting posture and pressure distribution—provides feedback for correction; heart rate, respiration rate, blood pressure, and blood oxygen levels, user activities based on pressure and movement data. | Validated through user testing and machine learning validation processes. (experimental testing and user testing) | 6—Tested in real environment (office). | No |

| [26] | 2017 | Conference Paper | Germany | Projector; Camera and Object Recognition; Smartphone Integration, LED Matrix, recorder | Data collection, Process/transmit information, Execute physical/digital actions | Table | Social interaction and communication | Social Interaction Enhancement Media Sharing Object Recognition Remote Communication Recording and Replaying. An interactive table designed to strengthen social connections in smart homes. | Images and other digital media shared by users; information about physical objects placed on the table and their interactions with the system. User Interaction Data, and health Data like heart rate or speed from mobile devices is displayed. | The Prototype was validated through a field study in three households. (user testing) | 5—Tested in 3 homes (real scenario, but small sample). | No |

| [27] | 2020 | Conference Paper | China | Hetai HT66F2390 microcontroller LCD12864 LCD Display Fingerprint module adopts ATK-AS608 fingerprint recognition module HC-SR501 human body sensing module Bluetooth audio receiver module M38 5 W power amplifier module | Process/transmit information, Execute physical/digital actions | Bedside Table | Efficiency and Daily Life Management | Night light and brightness adjustment refrigeration function heating and insulation device fingerprint unlocking LED light LCD screen. A smart bedside table with multiple integrated functionalities, to optimise space in the bedroom and improve the user experience. | Temperature humidity fingerprint data user interaction data | Used processes to validate the system’s functionalities such as dark environments (to test the nightlight) and with user interactions (such as using the fingerprint module). (experimental testing and user testing) | 4—Basic functionalities validated in the laboratory. | No |

| [28] | 2016 | Conference Paper | Portugal | Lifting mechanisms (electric, crank, pin slide) LED light sensor Arduino Relay | Process/transmit information, Execute physical/digital actions | Desk | Work/office spaces | Reconfigurable and ergonomic three-level desk | The article does not give attention to data collection, only mentions light intensity data (for automatic lamp activation) | A prototype was built to test the ergonomics and functionality of the table (experimental testing) | 6—Ergonomics tests on prototype | Considerations have been made such as: marketing plan, product cost, target market and use of sustainable materials, but it is not yet commercialised |

| [29] | 2023 | Conference Paper | Japan | Six-axis sensor (MPU9250) and an ultrasonic sensor (HC-SR04) | Process/transmit information, Execute physical/digital actions | Chair | Efficiency and Daily Life Management | Allows four different ways of sitting, adapting to different user needs and behaviours. | Posture data Load/weight data | Sensor tests (experimental testing) | 4—Without testing in real use | No |

| [30] | 2020 | Conference Paper | Republic of Korea | Infrared communication sensors and servo motors. Arduino UNO Voice commands | Data collection, Process/transmit information, Execute physical/digital actions | Storage Cabinets | Efficiency and Daily Life Management | Assist users’ organising and finding behaviour | User interaction data: Voice commands User feedback: Perceived usefulness, ease of use, perceived intelligence, product evaluation (via questionnaires). | User testing WOZ technique: Simulated robotic behaviour. Quantitative measurements: Questionnaires (experimental testing and user testing) | 5—Tested with users (WOZ technique). | No |

| [31] | 2021 | Journal Article | Republic of Korea | Triboelectric Nanogenerator (TENG) Arduino Uno Reactive-Ion Etching (RIE). | Data collection, Process/transmit information, Execute physical/digital actions | Desk | Efficiency and Daily Life Management | Smart desk that triggers an alarm if an intruder accesses it | Electrical output data generated by TENG. Intrusion detection data: Signals triggered by contact with the table. | Electrical performance testing Stability testing Real-time application testing Finite element simulation: COMSOL Multiphysics to validate the working mechanism. (experimental testing) | 5—Validated in laboratory and simulations (without external testing). | No |

| [32] | 2016 | Journal Article | Finland, Norway, Germany and China | force plates—FP3 infrared sensors camera and facial recognition module Bluetooth pressure sensors | Data collection, Process/transmit information | 2 Chairs 1 Mirror | Health and well-being, Targeted to older people | Fall detection and monitoring Older person monitoring and check-in | chairs: quantitative data on physical function (user’s position) mirror: facial data | usability studies with older adults interviews (user testing) | 6—Tested in usability studies. | No |

| [33] | 2023 | Conference Paper | Italy | Cloud platform Sensors: temperature, humidity, air quality (PM10, PM2.5, PM1, CO, CH4, VOC), atmospheric pressure, brightness, and soil moisture. | Data collection, Process/transmit information | Outdoor furniture (e.g., benches, vases, fountains, street furniture) | Environment monitoring | Monitors and controls garden parameters. Provides automated garden management via IoT. Enhances user experience through interaction with an app. | Air quality, temperature, humidity, pollution levels. Soil moisture, irrigation status. App usage and system control. | Rapid prototyping; Testing of 3D-printed models and manual/digital modifications. Scenario-based design: Application scenarios defined through focus groups and iterative revisions. (experimental testing and user testing) | 4—Tested in simulated scenarios. | No |

| [34] | 2023 | Conference Paper | Australia | Wireless sensor nodes (Arduino Uno R3, ESP-13 WiFi shield) ultrasonic sensors temperature sensors | Data collection, Process/transmit information | Outdoor furniture—bins, seats, bus shelters | Environment monitoring | Environmental monitoring (temperature, humidity, garbage level, air quality), crowd measurement (via WiFi-enabled devices), and real-time data communication. | Environmental data (temperature, humidity, garbage level, air quality), WiFi probe requests (MAC addresses, signal strengths). | Experiments conducted with five bins deployed, comparing static and dynamic communication models (experimental testing) | 5—Tested in an urban environment (small scale). | No |

| [35] | 2024 | Conference Paper | Germany | capacitive sensors microcontrollers Bluetooth actuators | Data collection, Execute physical/digital actions | Office chairs | Health and well-being, Work/office spaces | Promotes dynamic sitting posture, reduces muscular tension, and supports active health through haptic feedback. | Sitting posture, pressure distribution, duration in specific positions, and force-displacement measurements. | Experiments with 12 test subjects, force-displacement measurements, FEM optimisation, and sensor testing. (experimental testing) | 6—Tested with 12 users (empirical data). | No |

| [36] | 2020 | Conference Paper | USA and UK | IoT sensors (temperature, humidity, CO2, volatile organic compounds VOC, PM, illuminance, motion, sound level, distance) Raspberry Pi RFID tag PoE (Power over Ethernet)—only in version 1 prototype Machine learning algorithms motorised sit-stand feature | Data collection, Process/transmit information, Execute physical/digital actions | Desk | Health and well-being, Work/office spaces | Personalises indoor environmental conditions (thermal, visual, and acoustic comfort), reduces sedentary time, and improves posture and ergonomics. | Thermal comfort data (temperature, humidity), visual comfort data (illuminance, correlated colour temperature), air quality data (CO2, VOC, PM), occupancy state, power consumption, and user preferences. | Ongoing development with iterative versions of the desk (Version 1, 2, and 3), incorporating user feedback and sensor data to refine functionality. (experimental testing and user testing) | 6—Iterative development (versions 1–3 with user feedback). | No |

| [37] | 2018 | Conference Paper | Republic of Korea | Raspberry Pi Arduino UNO Pressure sensors Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) IoT x-y floater and motor Deep Learning (AI) | Data collection, Process/transmit information, Execute physical/digital actions | shoe cabinet | Efficiency and Daily Life Management | Automatic shoe storage, shoe type and colour classification, and shoe recommendation based on user input (clothing and destination). | Shoe images (type and colour), user input (clothing type and destination), and shoe storage status. | No, only prototyped | 3—Conceptual prototype without validation. | No |

| [38] | 2020 | Conference Paper | China | Raspberry Pi TFT LCD display infrared frame Baidu Voice Assistant | Data collection, Process/transmit information | Mirror | Environment monitoring, Efficiency and Daily Life Management, Social interaction and communication | Acts as a smart home centre platform, controlling home appliances, displaying real-time information (weather, news, time), monitoring home environments, and enabling remote interaction. | Real-time home environment data, user interaction data (touch, voice), and monitoring data (images, security alerts). | No, only prototyped | 4—Patent pending (no large-scale testing). | The project is pending patent applications, but no explicit commercialisation details are provided in the text. |

| [39] | 2017 | Conference Paper | Italy | Sensors (environmental, acoustic, presence) RFID WiFi NFC | Data collection, Process/transmit information | Smart urban furnishings (benches, worktops, digital islands) | Environment monitoring | Provides innovative services to citizens, monitors urban environments, and enhances public services through data collection and processing. | Environmental data (pollution, emissions, noise levels), urban dynamics, and user interaction data. | Prototype development and testing (collaboration between academia and industry partners) (experimental testing) | 5—Tested in academia-industry collaboration. | The project aims to define a sustainable business plan, but no explicit commercialisation details are provided in the text. |

| [40] | 2018 | Conference Paper | Germany | Capacitive proximity sensors machine learning algorithms (C4.5 Decision Tree, kNN, SVM, Naive Bayes, Random Forest). | Data collection, Process/transmit information | Sofa | Health and well-being | Detects proximity and motion of the human body to recognise emotional states (e.g., anxiety, interest, relaxation). | proximity, motion, posture, and movement data. | Study with 15 participants, using both elicited and acted emotions, and machine learning evaluation with leave-one-subject-out cross-validation. (user testing) | 5—Tested with 15 participants. | No |

| [41] | 2022 | Conference Paper | USA | ultrasonic sensors Xbee 802.15.4 PRO RF Modules Leap Motion controller Arduino stepper motors linear actuators LED | Execute physical/digital actions, Data collection, Process/transmit information | Robotic furniture suite (chair, side table, and screen). | Targeted to older people, Efficiency and Daily Life Management | Assists elderly users with mobility and daily activities, enabling ageing in place. | User gestures, chair occupancy, and table/screen positioning data. | Initial experiments with senior citizens, focusing on usability and functionality. (user testing) | 4—Initial usability testing. | No |

| [42] | 2017 | Conference Paper | Germany | Textile capacitive sensing electrodes OpenCapSense board (microcontroller) | Data collection, Process/transmit information | Sofa | Health and well-being | Posture detection and recognition | Capacitive sensor data for posture recognition (e.g., sitting upright, leaning back, lying down) | Leave-one-subject-out cross-validation with 15 test persons and 14 postures (user testing) | 5—Validated with 15 users (cross-validation). | No |

| [43] | 2015 | Conference Paper | Colombia | Proximity and distance sensors ultrasonic sensors Raspberry Pi Zigbee wireless communication traction mechanisms | Data collection, Process/transmit information, Execute physical/digital actions | Chairs and tables | Efficiency and Daily Life Management | Automated spatial configuration of work environments. The furniture pieces move around to adapt to the needs of the occasion. | Distance measurements, spatial positioning data, and user input for configuration settings | No | 4—Prototype without testing in a real environment. | No |

| [44] | 2022 | Conference Paper | Greece | Weight Sensors PLC (Programmable Logic Controller) | Data collection, Execute physical/digital actions | Main entrance furniture piece | Efficiency and Daily Life Management | Face recognition, reminders, information display, storage for small objects | Face recognition data, user interaction data (e.g., reminders, clothing suggestions), and sensor data for object detection | No | 5—Market plan, but without implementation. | The product is intended for both the Greek and European markets, with a profit-loss analysis suggesting potential profitability if launched in both markets. Prices are competitive for high-value furniture, but no specific commercialization details are provided. |

| [45] | 2024 | Journal Article | Australia | Sensors Wi-Fi IoT | Data collection, Process/transmit information, Execute physical/digital actions | Hub: Street Furniture | Environment monitoring Social interaction and communication | Create flexible places to meet, work, and play. combat rising urban temperatures. Capture local environmental conditions | Number of users; Environmental Data; Resource Consumption Data: Power usage, water usage; Performance and status of the public furnishings | surveys with both users and non-users to evaluate public perception and usage (user testing) | 9—Actual system proven in operational environment | Product already commercialised |

| [46] | 2024 | Journal Article | Egypt | IoT, Sensors | Data collection, Process/transmit information, Execute physical/digital actions | Mirror and Drawer | Efficiency and Daily Life Management | Monitor environmental conditions; Collect real-time data on space usage | Real-time user behaviour, environmental conditions, space usage patterns | Conceptual framework; proposed validation via simulation and pilot deployments (experimental testing) | 4—Prototype without testing in real scenarios. | No (theoretical framework only) |

| [47] | 2024 | Journal Article | Egypt | IoT, Sensors, Arduino, User interfaces, LED | Data collection, Process/transmit information Execute physical/digital actions | Table | Targeted at old people Health and well-being | Surface colour changes to warn users (children, deaf and older people) of hot components that could harm Them. | Surface temperature, presence of thermal objects, and thermal risk level | Lab Testing (experimental testing) | 4—Prototype without testing in real scenarios. | No |

References

- Xu, L. Research on Design Trends and User Experience of Smart Home Furniture. Appl. Math. Nonlinear Sci. 2024, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samancioglu, N.; Väänänen, K.; Castaño-Rosa, R. Aligning smart home technology attributes with users’ preferences: A literature review. Intell. Build. Int. 2024, 16, 129–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aheleroff, S.; Xu, X.; Lu, Y.; Aristizabal, M.; Pablo Velásquez, J.; Joa, B.; Valencia, Y. IoT-enabled smart appliances under industry 4.0: A case study. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2020, 43, 101043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcar, O.; Maresova, P.; Selamat, A.; Melero, F.J.; Barakovic, S.; Husic, J.B.; Herrera-Viedma, E.; Frischer, R.; Kuca, K. Smart furniture as a component of a smart city—Definition based on key technologies specification. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 94822–94839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejcar, O.; Maresova, P.; Brida, P.; Barakovic, S.; Husic, J.B.; Kuca, K.; Selamat, A. Technology Analysis of Global Smart Furniture Development Using Patent Data. In Proceedings of the 2020 ELEKTRO, Taormina, Italy, 25–28 May 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Maulana, F.I.; Kurniawan, B.K.; Pramono, A.; Purnomo, A.; Abdulah, M.E.B.Z.; Mohamed, M. Internet of Things for Smart Furniture: A Systematic Review. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on ICT for Smart Society (ICISS), Yogyakart, Indonesia, 4–5 September 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, M.; Han, S.; Ghorbany, S.; Zhang, K. Healthy Aging in Place with the Aid of Smart Technologies: A Systematic Review. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 1918–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Guerra-Santin, O.; Mohammadi, M. Smart home modification design strategies for ageing in place: A systematic review. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2022, 37, 625–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, F.J.M. Soluciones TIC para Envejecimiento Activo y Saludable en el Hogar, en el Puesto de Trabajo y en la Sociedad. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Politécnica de Cartagena, Cartagena, Spain, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dangkua, N.Y.; Nandito, M.A.; Jamil, F.H.P.; Rahayu, M. Implementing Human-Centric Design in Developing a Multifunctional Chair and Storage Solution for Children. J. Sist. Tek. Ind. 2024, 26, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Rahmadya, B.; Sun, R.; Takeda, S. A Feasibility Study on Monitoring Earthquake-Caused Furniture Vibrations Using Radiofrequency Identification Sensor Tags. Sensors 2023, 23, 3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haarman, J.A.M.; de Vries, R.A.J.; Harmsen, E.C.; Hermens, H.J.; Heylen, D.K.J. Sensory Interactive Table (SIT)-Development of a Measurement Instrument to Support Healthy Eating in a Social Dining Setting. Sensors 2020, 20, 2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescott, T.J.; Conran, S.; Mitchinson, B.; Cudd, P. IntelliTable: Inclusively-Designed Furniture with Robotic Capabilities. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2017, 242, 565–572. [Google Scholar]

- Wallbaum, T.; Heuten, W.; Boll, S. RemoTable: Sharing Daily Activities and Moods Using Smart Furniture. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2016, 229, 345–354. [Google Scholar]

- Bleda, A.L.; Fernandez-Luque, F.J.; Rosa, A.; Zapata, J.; Maestre, R. Smart Sensory Furniture Based on WSN for Ambient Assisted Living. IEEE Sens. J. 2017, 17, 5626–5636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, R.; Linner, T.; Trummer, J.; Guettler, J.; Kabouteh, A.; Langosch, K.; Bock, T. Developing a Smart Home Solution Based on Personalized Intelligent Interior Units to Promote Activity and Customized Healthcare for Aging Society. J. Popul. Ageing 2020, 13, 257–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Lu, D.; Zhao, N. A New Design Approach: Applying Optical Fiber Sensing to 3D-Printed Structures to Make Furniture Intelligent. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donato, M.C.D.; Corradini, F.; Fornari, F.; Re, B. SAFE: An ICT platform for supporting monitoring, localization and rescue operations in case of earthquake. Internet Things 2024, 27, 101273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fewella, L.N. The behavioral smart furniture and its relevance to family emotional dynamics. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 103030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]