Abstract

The article presents an overview of knowledge in the field of energy microgrids as smart structures enabling energy self-sufficiency, with particular emphasis on decarbonisation. Based on a review of the literature and technical solutions, the characteristics have been classified and, emphasising the potential for integrating different technologies within microgrid structures, the role that microgrids and their users can play in the functioning of the energy system has been defined. Energy microgrids can be the pillar on which smart energy structures and smart grids, including energy systems using multiple energy carriers, will be based. Microgrids can guarantee energy self-sufficiency within their area of operation and support the entire energy system in this respect. Sensors that respond to both electrical and non-electrical quantities must play a special role in such structures, as they form the technical basis for the functioning of the smart energy sector.

1. Introduction

Microgrids are currently regarded as an element of modern, transforming energy systems. They are associated with concepts such as microgeneration, distributed generation, renewable energy sources, energy storage, energy management, demand response, and above all, smart grids.

The history of energy microgrids dates back to the beginning of the history of electrical power engineering. The first structure supplying electricity using DC systems, built by T. Edison in 1882, was in fact a microgrid [1,2].

Small systems were also the starting point for the energy industry in other parts of the world. In Europe, in 1882, De Bolltes supplied 1.5 kW generated by a steam engine at the Miesbach coal mine to an area 57 km away via a direct current line at a voltage that today would be classified as medium voltage [3]. In 1897, the Sidrapong hydroelectric power station in India was commissioned to serve local loads [4]. Small systems were gradually connected into a larger network, creating more complex power systems operating synchronously and now covering entire continents. The modern network operating within the power system is one of the greatest achievements of modern engineering, a huge, man-made machine on an intercontinental scale with thousands of generators and millions of customers [5].

After the famous blackout in the USA in 2003 and later after Hurricane Sandy in 2012, installations with diesel generators as a backup power source began to gain popularity, enabling effective power supply to facilities for a longer period of time without the need to draw energy from the grid [1,6].

Such structures can be considered microgrids. History thus comes full circle. Interest in the concept of microgrids and its clear development came after the first decade of the 21st century. This development was driven by advances in renewable energy technologies, small-scale generation, energy storage systems and power electronics [7,8]. The result of the growing popularity and development of the microgrid concept during this period is a non-linear increase in the number of scientific publications in the field of energy containing the keyword ‘microgrid’ (Figure 1).

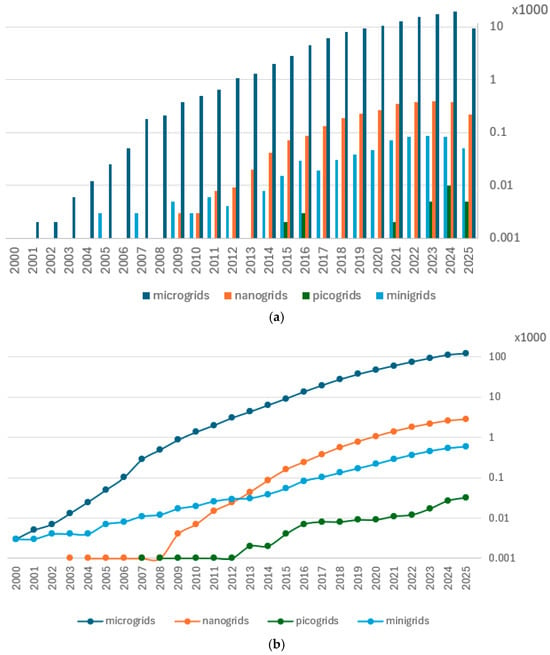

Figure 1.

Number of articles (in thousands, logarithmic scale) in the Scopus database in the field of energy (SUBJAREA(ENER)) concerning ‘microgrids’ (or ‘microgrid’); ‘nanogrids’ (or ‘nanogrid’); picogrids (or ‘picogrid’), published in subsequent years—annual increases (a), cumulative values (b) as of 27 July 2025.

The scale of scientific interest in the area of distributed energy systems is clearly focused on microgrids, which are seen as the most versatile and scalable solution. The number of publications using the concept of microgrids is by far the largest, with more than 123,000 papers in 2025. Since 2008, we have seen an exponential increase in interest in this issue. Nanogrids and minigrids are gaining attention as solutions for specific contexts, and although the number of publications using these concepts is steadily increasing (reaching around 3000 and 60 entries, respectively, in 2025), it is orders of magnitude smaller compared to publications on microgrids. Picogrids remain in the realm of conceptual considerations and do not have a significant impact on mainstream energy research (approximately 30 publications by 2025)—Figure 1.

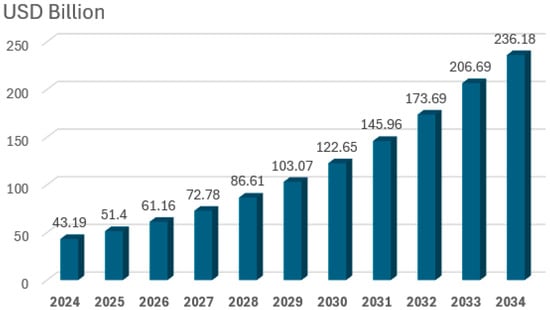

Due to the individual and distributed character of projects, the small size of a single investment, the lack of mandatory reporting and, in addition, the lack of a universal definition and thus the lack of a uniform methodology, detailed and up-to-date global statistics on microgrid deployments are not widely available. In 2019, they were estimated to number more than 4500 [9]. There are also discrepancies in estimates of the size of the global microgrid market. According to [10] the global microgrid market was valued at USD 22.9 billion in 2024. The market is expected to grow from USD 28.9 billion in 2025 to USD 140.7 billion in 2034, at a CAGR of 19.2%. According to [11], the global Microgrid market size is USD 42.6 billion in 2024 and will expand at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 21.6% from 2024 to 2031. According to [12] experts predict the global microgrid market will expand significantly, from $43.19 billion in 2024 (share of North America: 41%, Europe: 28%, Azja Pacific: 23%) to approximately $236.18 billion by 2034 (Figure 2). This growth represents a CAGR of 18.52% over the decade, which demonstrates the growing importance of microgrids in the global energy sector. Such developments are driven by, among other things, the growing demand for renewable energy sources, the need to increase the resilience of energy infrastructure and the development of energy storage technologies and grid management systems.

Figure 2.

Number Microgrid global market size to 2034 (according to [12]).

It is worth noting that the rate of growth accelerates in the second half of the decade under review, with the market growing by more than USD 30 billion per year after 2030. This may indicate accelerated global microgrid adoption and increased investment in the energy sector (Figure 2).

Microgrids are becoming a key element in the global energy transition, with their number and installed capacity growing at an impressive rate. The increase in the number and installed capacity of microgrids reflects the growing demand for local, flexible energy solutions.

The aim of this article is to present and analyse knowledge about specific structures, namely energy microgrids, in the context of the energy sector’s transition towards solutions based on zero-emission generation, with particular emphasis on the role of various sensors in the implementation of smart grid solutions. The review methodology consisted of searching scientific databases and conference materials. From these searches, the most relevant and recent items on the functioning and management of microgrids were selected. The search focused on the basic components of microgrids, with particular emphasis on new trends in energy management, enabling energy self-sufficiency, taking into account the issue of decarbonisation.

A narrative literature review methodology was chosen. This approach seems to us to be more appropriate for this topic, given the multifaceted nature that has grown up around the issue of the development of microgrid structures. The criteria for inclusion of publications in this review consisted of two conjunctive conditions, namely: (1) must refer to the concept of microgrids; (2) must come from reliable sources (scientific literature and grey literature, but in the form of industry organisation reports, articles from recognised industry portals, government documents and standards); (3) must address the issue of finding an efficient form of energy distribution and use with a view to ensuring energy sufficiency. In terms of condition (3), more detailed criteria were formulated for the content on an alternative operator basis, namely concerning: (a) the history of the development of energy structures; (b) the definition of concepts; (c) systematics and structure types; (d) structure construction and components; (e) energy management; (f) sensors; (g) decarbonisation and energy transition; (h) energy technology integration; (i) energy self-sufficiency. A departure from direct reference to the concept of microgrids in the cited publications occurred in the part of the article discussing examples of sensor applications to illustrate existing solutions that could potentially also be used in microgrid structures.

Using a Boolean search strategy, the search terms used to select items are (microgrid*) AND (power OR energy) AND (histor* OR definition* OR systematic* OR topolog* OR example* OR component* OR structure* OR formation* OR management* OR sensor* OR decarboniation* OR “energy transformation” OR integration OR self-sufficeincy). A literature search was conducted in the Scopus database. The selection of publications was limited to items no older than 2004 due to the significant increase in popularity of the idea of microgrids that has occurred in the last 20 years.

The selection process involved restricting the items to English language, energy area and open access, yielding almost 33,000 items. From this database of items, using the tool available in Scopus “Refine search”, further keywords related to the themes discussed in the paper were entered, yielding a few to several dozen publications each time, from which titles and abstracts were searched, followed by full texts. In situations where publications referred to other works or documents, the content was confronted with grey literature or other works. Based on the collected materials, an analysis of the situation and the expected role of microgrid-based structures was carried out.

Of the many issues covered, microgrid review papers tend to focus mainly on issues of schemes, mechanisms and control strategies for microgrids ([8,13,14,15,16]), energy management in microgrids ([17,18,19,20]) microgrid architectures ([17,21,22]), economic and market considerations ([13,19,21]) the specifics and need for microgrid interoperability with energy storage systems ([15,16,18,23]) RES generation technology issues in microgrids ([14,15,17,19,20]) equipment, security and/or communication methods in microgrids ([15,16,18,21,22]). The works cited do not address the use of sensors in microgrids more extensively. An example of the few review articles comprehensively addressing the use of sensors in the energy management process in microgrids is the paper [24], which does not address the role and importance of microgrids, nor does its scope include a discussion of microgrid functionality. No publications have been encountered in the literature that critically address the definition and classification of structures commonly referred to as microgrids. This article, in contrast to the aforementioned ones, seeks to present and complete the current picture of the key components of the microgrid category as a modern, intelligent and self-sufficient energy structure, a structure adapted to the challenges of the energy transition. The comprehensiveness of this review relates to the level of potential frameworks for energy self-sufficiency of microgrids based on the use of a variety of sensors.

The article is structured as follows: after the introduction (Section 1), the problem of defining the concept of microgrids is analysed (Section 2), followed by a discussion of possible classifications of microgrids (Section 3). Section 4 analyses the basic components that make up the structure of a microgrid. Section 5 is dedicated to the issue of using sensors in microgrids. Section 6 analyses the functioning of microgrids in the context of the challenges associated with the energy transition, with particular emphasis on decarbonisation. Section 7, based on the information presented in the previous sections, discusses the expected role that microgrids and their users may play in a smart power system with signalling of research directions. The whole is concluded by Section 8 with summary conclusions.

2. Definition of a Microgrid

In addition to microgrids, structures comprising smaller installations and energy networks are also referred to as nanogrids, picogrids [25] and minigrids. Picogrids, nanogrids, and microgrids are types of electrical grids typically associated with individual households, buildings, and neighbourhoods, respectively, and are ultimately connected to the main power distribution grid or to another microgrid [21].

A picogrid is a small-scale energy network that distributes power at the device level, utilising devices with storage capabilities as decentralised energy storage units. One key advantage of picogrids is their ability to supply power specifically suited to the requirements of individual appliances [26,27].

Nanogrid refers to a single small power system with features such as: residential, small industrial or commercial site; small in size (<50 kW); behind a single meter; includes the generating source, in-house distribution, and energy storage functions (thermal/electric), also obtained with electric vehicles [28].

The energy distribution system for a single house/building can be called a ‘nanogrid’, while the distribution system for multiple houses/buildings can be called a ‘microgrid’, consisting of interconnected nanogrids [29]. A nanogrid is a compact version of a microgrid, usually designed to supply power to a single building or individual load. Whereas microgrids function as foundational components of a smart grid, nanogrids act as the cell units within a microgrid [30]. Minigrids are small-scale power generation systems that supply electricity to a limited group of users. Their generation capacity typically ranges between 50 kW and 1 MW. They offer an effective solution for providing electricity in rural areas [30].

However, there is currently no consensus on the precise terminology and categorisation of concepts, especially in terms of the installed capacity of structures assigned to pico-, nano-, micro- and milli-grids [21]. The most popular concept in this context is microgrid, and attempts are being made to fully define and standardise it. Microgrids are the subject of dedicated standards (e.g., IEC TS 62898 series). Although there is still no consensus on a strict definition of microgrids in terms of control, operation, and energy/power management [31].

The IEC defines a microgrid as ‘‘group of interconnected loads and distributed energy resources (DER) with clearly defined electrical boundaries that acts as a single controllable entity with respect to the grid and can connect and disconnect from the grid to enable it to operate in both grid-connected or island mode.” [32].

CIGRÉ C6.22 Working Group’s Microgrid Evolution Roadmap, IEEE standard 2030.7 [33] and U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) all define microgrid in similar terms—loads, distributed energy resources (generation, storage and load control), and the concept of operating with or without a grid [34,35,36,37].

The IEEE 2030.7-2017 standard reduces the complexity of microgrids to two fixed operating modes (Steady State Grid Connected and Stable Island) and four types of transitions (Transition from Grid Connected to Steady State Island—Planned; Grid Connected to Steady State Island—Unplanned; Steady State Island reconnect to Grid; Black Start into Steady State Island). These definitions do not mention a control unit for facilitating the system’s features (e.g., seamless transfer and working as a supplementary power supply) [38]. None of the sector definitions specifies the minimum time for which a microgrid should be able to operate efficiently without being connected to the power grid. Nor do the definitions say anything about the size of the distributed energy resources used or the types of technology that may be implemented.

It can be concluded that microgrids are distributed energy resources that can operate autonomously. Microgrids are defined by their function, not by their size. The size of a microgrid depends basically on the peak power required by the loads [39]. Microgrids are anticipated to include all the fundamental elements of a conventional power system on a smaller scale, excluding certain non-essential components like transmission lines and substations. The primary concept behind a microgrid is to integrate a limited number of distributed generation units and manage them efficiently without forming a complicated network. Key elements of a microgrid include a hierarchical control structure, a point of common coupling (PCC), distributed control based on local data, and a defined area that facilitates the organised integration of distributed generation units to ensure the system operates reliably [38].

A microgrid is a possible future energy system paradigm formed by the interconnection of small, modular generation units, storage devices and controllable loads in distribution systems [40]. Microgrids offer an effective platform for energy harvesting and load-side energy management, contributing to energy savings [41].

In view of the above definitions, a microgrid should be treated as a structure enabling the distribution of energy within a specific limited area, which may include various carriers and forms of useful energy, at least partly originating from its own generation sources classified as distributed generation or microgeneration technologies. A microgrid can be equated with a small, physically connected, fully functional, self-controlling and autonomously operating energy system, which may or may not have an active connection to the external national power system. The term ‘small’ system is vague, and in the absence of criteria currently agreed upon by energy experts (regarding the range of installed capacity), the criterion of the voltage used in the network should be considered, namely, within a range not higher than that corresponding to medium voltages. Any connection to the national power system should therefore be at the level of the power distribution network (low voltage, seldom medium voltage). If a microgrid is to operate in island mode in the long term, it must meet high requirements in terms of having sufficient energy storage capacity or relying on high flexibility of internal energy demand. Consumers are open to participating in demand side response (DSR) programmes, offering their own energy usage flexibility in exchange for specific bonuses [42].

It should be noted that a microgrid itself cannot be considered part of the public distribution network. A microgrid does not exchange energy with the external network in a disorderly manner, like an inflexible prosumer, but in a properly controlled manner. From the network operator’s point of view, an intelligently managed microgrid can be treated as a flexumer [43]. Aggregator models that disregard the physical locations of generators and loads (e.g., virtual power plants) are not microgrids [44].

Microgrids can be hierarchically composed of smaller networks or installations with characteristics of autonomous management and, at least partial, self-balancing, and can also be combined into larger structures [45] (sharing energy, e.g., within a community [16]).

A microgrid operator is more than just an aggregator of small generators, a network service provider, a load controller or an emissions regulator—it performs all these functions and serves multiple economic, technical and environmental objectives. One of the main advantages of the microgrid concept over other ‘smart’ solutions is its ability to deal with the conflicting interests of different stakeholders in order to achieve a globally optimal operational decision for all players involved.

Microgrids are increasingly recognised as a game-changing solution to today’s energy challenges, driven by the need for efficient, resilient and sustainable energy systems. It is considered that the smart grid is an advanced form of the microgrid, enhanced by information and communication technology (ICT) to improve grid operations and customer service [15,46].

3. Types of Microgrids

Due to the lack of a universally recognised classification and their lesser popularity, ‘picogrid’, ‘nanogrid’, ‘minigrid’ and ‘miligrid’ will not be distinguished in the rest of this article, and all structures with the above-mentioned characteristics will be referred to as ‘microgrids’.

As technical facilities, energy microgrids can be categorised according to various criteria characterising their structure and resulting from their functionality, so there is a wide variety and multitude of practical solutions. Microgrids are used in various sectors, including residential areas, shopping centres, industrial facilities, and even transport hubs such as airports and ports [47] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Examples of classification criteria for microgrids.

One of the distinguishing features of a microgrid is its connection to the external power grid. A microgrid may comprise a single installation or a conglomerate of multiple facilities belonging to different entities (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Examples of microgrid implementation.

Among the various types of microgrids, certain configurations demonstrate a significantly higher predisposition toward achieving energy self-sufficiency. The most prominent are off-grid (islanded) systems, which by design must ensure continuous, independent energy supply, often in the absence of any connection to the public grid. Such systems are commonly deployed in remote or inaccessible locations, including isolated settlements, research stations, or military installations, where autonomy is a necessity rather than a choice. Similarly, microgrids based on renewable energy sources (such as solar, wind, hydro or biomass), when supported by sufficient storage capacity and effective energy management, are inherently well-suited for self-sufficient operation. High levels of autonomy are also characteristic of mobile or temporary microgrids, which are intended to function independently in field conditions, for instance during emergency response operations or military deployments. Furthermore, distributed control architectures increase the resilience and local decision-making capability of microgrids, making them more robust against external disruptions and more conducive to autonomous operation. In contrast, grid-connected microgrids, particularly those operating in urban or industrial settings, generally prioritise energy efficiency, reliability, and cost optimisation over full independence, although many retain the capability to operate in island mode temporarily. Consequently, the degree of energy self-sufficiency is closely related to the microgrid’s operational mode, location, and strategic purpose.

4. Microgrid Components

Microgrids, as platforms integrating energy supply units (microgeneration), consumption units (controlled loads) and energy storage units within their own local distribution network, must have a structure management system in order to intelligently utilise the opportunities offered by the interaction of these components and achieve energy self-sufficiency for users. In modern civilisation, the most popular and useful form of energy is electricity, so a microgrid should primarily include electricity conversion and distribution systems. The basic components that make up an energy microgrid are discussed below.

4.1. Management System

Microgrids in the field of electricity distribution can use hybrid AC/DC networks to integrate multiple energy sources and energy storage systems. At the heart of this integration are energy management systems (EMS), which support control, energy management and the reliability of such an integrated system [55].

The management system does not operate in an isolated environment and cannot ignore a number of factors, which can be divided into [18,19,56,57,58].

- Internal, resulting from the technical conditions for the correct operation of the microgrid:

- ○

- Energy level in storage facilities (e.g., batteries, heat storage tanks);

- ○

- Quality requirements for the energy supplied;

- ○

- Rules for operating the microgrid (e.g., voltage conditions, load limits on power lines, possibilities for regulating flows and reactive power, permissible parameters for the storage and transmission of other energy carriers).

- External, resulting from the environment in which the microgrid operates:

- ○

- Availability of carriers, supply of primary energy resources (including weather conditions);

- ○

- Requirements of the external distribution network operator (in the case of cooperation with the national power system).

- Resulting from the specific nature of the activity served by the microgrid:

- ○

- Instantaneous power demand of consumers;

- ○

- Optimisation of operating costs.

User requirements depend on the expected functionality of the facilities (e.g., resulting from production processes—for industrial microgrids, municipal and residential needs—for microgrids in buildings).

A comprehensive energy management solution incorporates process data from control and data acquisition systems, network monitoring, inverters, system automation, and other components. Additionally, the remote cards are designed as plug-and-play devices, allowing for fast and easy installation of the management system [53].

A microgrid requires an effective EMS to oversee the operation of its intricate network of electrical, thermal, and mechanical components. This system should deliver both short-term results—by adjusting to fluctuations in demand and production—and long-term benefits—by extending the lifespan of the most expensive and sensitive microgrid elements. Ultimately, this leads to lower system costs and greater overall benefits [59].

The technical and mechanical aspects of EMS must be carefully maintained to improve system reliability by effectively managing both user and utility sites. An optimisation technique is essential for EMS to regulate the actions of consumers, stakeholders, and utilities concerning production, consumption, market demand, and cost [15].

Microgrid optimisation aims to maximise the instantaneous power output of generators, extend the lifetime of the energy storage system (ESS), and minimise environmental impact and operating costs. To achieve this, it is necessary to define constraints and objective functions that address the microgrid’s operating costs.

A broader approach to decision-making by EMS includes, in addition to model-based methods (such as distributed optimisation based on consensus algorithms, game theory, and MPC (model predictive control) algorithms, data-driven methods whose main feature is the lack of a model of the system to perform energy management (e.g., stochastic, robust, distributionally robust optimisation algorithms, deep neural networks, reinforcement learning) [45].

For such a management system to work efficiently, it must be based on new technologies that enable multi-criteria optimisation in changing conditions, taking into account multiple parameters in real time. Methods and techniques based on AI, technologies using Blockchain and IoT (under the collective name BIoT) are used here. Various optimisation techniques are used [20,59]—Table 3:

Table 3.

Modern methods, techniques and instruments for energy management in microgrids.

The system has three main control models, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. Distributed control may be a good compromise, providing satisfactory quasi-optimal solutions at reasonable computational costs and communication layer complexity (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Types of control within the microgrid management system.

Centralised control is often used in scenarios where a high level of coordination is required, such as in grid-connected microgrids where the central controller can manage power flow and ensure stability [63,64]. Decentralised approach is suitable for islanded microgrids or scenarios where reliability and fault tolerance are critical, such as in remote or off-grid locations [65,66,67].

Distributed control is suitable for complex microgrid configurations, including networked microgrids and hybrid AC/DC microgrids, where coordination among multiple distributed energy resources (DERs) is necessary [68,69]. The distributed control scheme allows for a combination of centralised and decentralised control to a certain extent. In this approach, each local controller gathers information such as voltage and frequency from nearby units. This local data exchange, facilitated through two-way communication links, supports the central controller in achieving a global solution [62].

In simple terms, it can be said that centralised control is effective for small-scale microgrids, while decentralised control is better suited for large-scale microgrids. [16]. However, the choice of control strategy in microgrids depends on the specific application scenario, desired reliability, and system complexity. Centralised control is suitable for highly coordinated tasks, decentralised control excels in reliability and fault tolerance, and distributed control offers a balanced approach for complex and scalable systems.

An example of a central microgrid controller project, integrating metering, monitoring and energy management, is presented in [70]; it cooperates with, among other things, an energy demand forecasting module and an energy storage system. The paper [71] presents experience with the design and implementation of a microgrid in a commercial building, based on a centralised hierarchical control strategy to optimise its functionality. The implementation of the microgrid significantly reduced the electricity costs for connected loads in the building by 19.5%. Case studies comparison table for decentralised and distributed control strategies for microgrids can be found in [69].

Energy management objectives and strategies in a microgrid are shaped by user preferences. Because microgrids are modular and highly customizable, each one has distinct goals influenced by factors like geographic location, the types of installed equipment and loads, energy tariff structures, government policies, and the available energy storage and generation options within the microgrid [20].

An additional issue is emergency management strategies, which should be anticipated by the microgrid management system. These strategies are designed to increase the reliability of the microgrid in the event of potential random events, such as N-1 events, N-2 events, overloads, excessive generation, and short circuits. Emergency management strategies can be divided into preventive measures, protection against failures, and management of power outages [72].

4.2. Energy Sources

Another group of mandatory components of a microgrid structure are its own energy generation units, whereby a microgrid can be a multi-energy structure, i.e., in addition to electricity sources, it can also include sources of other forms of energy [73]. These sources are characterised by belonging to distributed generation sources with a single source capacity of less than 100 MW. The diversity of technologies promotes diversification, with zero-emission technologies being desirable, and modular SMR (Small Modular Reactors) are also being considered for use in microgrids [74].

Technologies used in a microgrid encompass both emerging and established solutions. These include innovative concepts like combined heat and power (CHP), micro wind turbines (MWTs), photovoltaic (PV) systems, microturbines, and fuel cells, alongside well-established technologies such as synchronous generators powered by DC engines, single-phase and three-phase induction generators, and small-scale hydroelectric systems. Dedicated chapters are devoted to the use of renewable sources in energy generation for microgrids, e.g., [75,76].

A special form of zero-emission energy generation in microgrids, which distributes heat in addition to electricity, is the recovery of thermal energy [77,78,79]. Heat recovery is an increasingly popular method in industry for reducing energy costs and minimising environmental impact. Heat recovery involves capturing and reusing heat generated during industrial processes, thereby reducing the amount of energy that would otherwise be wasted (Table 5).

Table 5.

Waste heat recovery technologies.

4.3. Energy Storage

Energy storage systems are tools that facilitate the self-balancing of microgrids. The energy storage system is crucial in regions with unpredictable weather conditions because of its ability to store energy and maintain a balance between energy supply and demand [59].

Technologies enabling effective storage in the short term (between times of day or a maximum of several days) and in the longer term (between seasons) are used. Storage can take the form of electricity (electrochemical, electromagnetic field), heat or fuel (including hydrogen)—Table 6.

Table 6.

Energy storage technologies.

4.4. Controllable and Categorised Loads

The microgrid has to manage the loads by accomplishing the following tasks [91]:

- Load monitoring, analytics, and prediction.

- Load balancing and demand response.

- Load shedding for non-crucial loads to fulfil the net import or export power in on-grid mode.

- Stabilise the voltage and frequency in the islanded mode.

- Enhance the power quality and reliability of critical loads.

- Load scheduling and resource planning for the resilient operation.

Loads can be categorised into four types: noncontrollable, shiftable, controllable comfort-based, and controllable energy-based loads. Controllable loads, often referred to as smart loads, combine noncritical loads—capable of tolerating short-term voltage or frequency fluctuations—with a power electronic interface that electrically isolates the load from the power source [59].

The simplest classification of loads divides them into two categories: critical loads, which must operate to ensure the safety of microgrid users, and other (non-critical) loads—Table 7.

Table 7.

Basic classification of loads in microgrid.

4.5. Microgrid Equipment to Support the Achievement of Energy Self-Sufficiency

Achieving energy self-sufficiency through a microgrid requires not only the presence of basic components such as energy sources, storage systems and management systems, but also their proper integration and ability to operate autonomously in dynamically changing conditions. It is crucial to equip microgrids with technologies that enable:

- independence from external energy suppliers

- full control of the local energy balance,

- flexible supply and demand management,

- dynamic adaptation to environmental conditions,

- use of locally available energy resources,

- response to emergency and crisis situations.

Self-sufficiency begins at the level of local, low-emission energy sources, whose operation is supported by systems that enable them to adapt flexibly to changing weather conditions. To this end, microgrids are equipped with AC/DC converters and multi-channel inverters, including grid-forming inverters, which allow different energy sources to interact in a hybrid AC/DC structure [92]. In addition, optimising production involves the use of control systems such as solar tracking systems and MPP (Maximum Power Point) controllers for PV systems, which enable real-time maximisation of solar panel efficiency [93], or automatic control systems for the direction and angle of microturbine blades.

Energy storage in a self-sustaining microgrid acts not only as a time buffer, but also as an element to stabilise grid parameters. For this purpose, it can be used [94,95,96]:

- Integrated Multi-Modal Storage Systems, combining, e.g., Li-Ion batteries with Thermal Energy Storage (TES) and hydrogen storage, so that energy can be balanced in different forms,

- Energy storage management systems (BMS/ESS Controller) interfacing with the EMS, allowing intelligent charging, discharging and reserving of resources depending on demand forecasts and scenarios,

- Inertial stabilisation resources (e.g., flywheels or supercapacitors) to provide rapid responses to voltage or frequency spikes, critical in islanding mode.

At the heart of the self-sustaining microgrid is the decision-making system, supported by an extensive measurement and control infrastructure. Key elements include:

- A network of energy sensors monitoring real-time generation, consumption, energy quality and equipment condition parameters

- Demand and production forecasting systems (e.g., based on machine learning), taking into account weather factors, equipment operating schedules and historical data,

- Local automation systems (PLC, HMI, SCADA), enabling instantaneous responses to system changes and control of resources without human intervention,

- Cybersecurity systems to protect user data and guarantee the integrity of EMS decisions.

Self-sufficiency requires not only ensuring energy supply, but also optimising consumption, coordinating the management of different types of energy resources in a given community to minimise energy costs [97]. To this end, the microgrid should be equipped with:

- Dynamic load management (DR/DSM) systems, allowing demand shifting and critical consumption reduction (load shedding),

- Managed loads with adaptive comfort functions—e.g., HVAC systems or lighting systems that react to occupant presence or energy availability,

- Intelligent terminal devices to communicate with the EMS and control energy consumption according to an optimisation algorithm,

A fundamental aspect of microgrid self-sufficiency is the ability to operate in island mode. This requires:

- Automation to separate the microgrid from the host network, while maintaining the stability of network parameters

- Mechanisms to automatically re-establish the connection (re-synchronisation) with the power system, while ensuring the technical conditions for synchronisation,

- Backup control logic and emergency systems, operating independently of the external network.

5. Sensors in Microgrids

5.1. Overview

Intelligent sensors are key to real-time monitoring and control of microgrid components, ensuring efficient and reliable operation [24,98]. Sensors enable coordinated and automated responses to changes in energy demand and supply [98,99]. They are used to collect and store data on energy production, consumption and storage, which is essential for predictive maintenance and optimisation of energy resources [98,100]. Thanks to the integration of smart sensors and advanced control systems, microgrids can significantly improve energy efficiency and reduce operating costs [101]. However, the huge amount of data generated by sensors requires robust data management and analytics to optimise energy management [100,102].

Various types of voltage and current sensors are installed in the smart grid to detect and identify system or line faults. With the support of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) and the Internet of Things (IoT), these sensors enable automatic fault recovery actions to be initiated promptly [15].

To maintain the reliability and safety of power transmission and distribution systems, various sensors are utilised. Current and voltage sensors are crucial for detecting faults, evaluating the performance of relays, and protecting the electrical grid. For example, non-contact inductive current sensors identify faults by detecting changes in current flow. Additionally, when high current loads cause transmission line temperatures to rise, surface acoustic temperature sensors [103] are used to monitor these increases, helping to prevent overcurrent issues.

Furthermore, issues like short circuits, wiring errors, or lightning strikes can cause power quality problems, leading to voltage and current fluctuations that could harm consumer devices. To address this, online sensors such as power quality monitors control the quality of the power supply, thereby contributing to reductions in power outages and load shedding. Fibre-optic sensors offer comprehensive monitoring of overhead transmission lines, tracking parameters like stress, strain, tension, magnetic fields, acceleration, and temperature. Finally, smart continuity grid sensors are employed to optimise electricity usage and enhance overall availability.

Smart Meters are equipped for real-time data collection, directly measuring key electrical parameters such as voltage, current, frequency, and phase angle. Thanks to their bidirectional communication, this recorded data is then securely and continuously transmitted to both the service provider and the customer. A crucial feature of Smart Meters is their ability to remotely manage the power supply-to-demand balance; they can connect or disconnect loads and control end-user power usage to help decrease overall consumption.

Current transformers and voltage transformers act as essential connections between measurement equipment—such as data acquisition systems and phasor measurement units—and the power system. However, harsh weather and challenging operating conditions can speed up transformer ageing, raising the likelihood of saturation. If transformer saturation is not properly managed, it can negatively impact the online monitoring, control, and protection mechanisms of microgrids [104,105].

Intelligent resource management involves responding to the effects of changing factors. Appropriately selected sensors are used to monitor these factors. The following types of sensors are used in microgrids, listed in order of popularity [24]: temperature, current, voltage, power, humidity, gas, frequency, pressure, vibration, and light. Examples of different types of sensors that can be used in smart microgrids are listed in Table 8.

Table 8.

Sensors and their use in microgrids.

Sensors play a crucial role in the operation and management of energy microgrids, contributing to their efficiency, reliability, and sustainability. Sensors enable the collection of real-time data on power characteristics, such as voltage, current, frequency, and power generation. This data is essential for monitoring and controlling the microgrid’s operations [174,175,176]. Advanced sensors, such as Waveform Measurement Units (WMUs), are used to detect disturbances and faults within the microgrid. These sensors provide GPS-synchronised measurements that help in quickly identifying and locating faults [177,178].

Sensors that monitor the condition of equipment, including partial discharge, infrared and vibration sensors, play a key role in maintaining the reliability and efficiency of microgrids. These sensors, combined with advanced communication and control systems, enable real-time monitoring and proactive maintenance, ensuring stable and secure microgrid operation.

Partial discharge (PD) measurement is a widely accepted method for assessing the health of electrical equipment, particularly for insulation systems in power components like generators, transformers, and switchgear [179,180]. PD sensors such as high-frequency E-field (D-dot) sensors, Rogowski coils, and loop antennas are effective due to their high signal-to-noise ratio and accuracy [179]. Low-cost RF detectors for PD monitoring provide a scalable solution for wide-scale deployment without extensive wiring, making them suitable for microgrids [181]. Infrared photoelectric sensors are used to detect temperature changes in electrical equipment, which can indicate insulation faults or excessive temperature rise [182]. Vibration sensors are crucial for monitoring mechanical conditions in microgrids. Sensors with AC outputs are preferred for detailed analysis using FFT (Fast Fourier Transform) to assess vibration amplitude and nature, while DC output sensors are used for machine protection, providing velocity or acceleration data [183]. Various sensors, including piezoelectric, electrodynamic, and magnetic sensors, are employed for vibration monitoring, each suited to specific applications and environmental conditions [184]. Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA) systems are integrated into microgrids for centralised monitoring and control, using wired and wireless sensor networks to track vital parameters and operational status [185,186].

An energy management model for microgrids involves data acquisition systems, supervised control, human–machine interface (HMI), and monitoring and analysis of meteorological variable data [18]. Sensors facilitate the optimisation of energy resources by providing accurate data for energy management systems (EMS). This helps in balancing the energy supply and demand, ensuring stable and efficient operation [62,187]. The data collected by sensors can be logged and analysed to predict future energy needs and costs, allowing for better planning and utilisation of renewable energy sources [174]. A closed-loop mechanism in EMS involves continuous data collection, analysis, and feedback to optimise energy management. Sensor networks play a pivotal role by providing real-time data on energy consumption and production [188]. The intricate design of a microgrid system necessitates the use of various sensors and monitoring devices, which generate diverse types of data—including structured data from traditional power systems, semi-structured data such as images from cameras, and unstructured data from sources like weather information, network configurations, and maps [62].

The connection of a large number of small and technically diverse energy sources in a microgrid can lead to voltage regulation problems, which poses a challenge for EMS. The article [189] proposes several sensor selection schemes that aim to improve voltage measurement efficiency in microgrids, extend the service life of sensor networks, and ensure real-time communication between distributed sensors and an intelligent control centre.

The EMS, thanks to a system of wireless sensors designed to monitor various variables from renewable sources, can effectively conduct balance energy demand and production and support the efficient use of energy resources [24,190]. Modern EMS leverage big data and predictive analytics to enable real-time system control and actionable insights [191]. The integration of data from diverse sources, such as smart meters and wireless sensors, enhances the management of decentralised energy systems, including electrical storage and renewable energy generation [192].

A review of applied sensor, communication and monitoring technologies for microgrids with case studies, to demonstrate the importance of mutual knowledge awareness between the power grid domain and the communication network was made in [193].

Sensors are integral in managing distributed energy resources (DERs) such as solar panels and wind turbines. They help in monitoring the generation patterns and optimising the use of renewable energy [99,194,195]. The integration of Internet of Things (IoT) technologies with sensors enhances the real-time monitoring and control of renewable energy systems, improving the overall efficiency of the microgrid [196,197].

Wireless Sensor Networks enable the deployment of sensors without existing infrastructure, facilitating the efficient and reliable transport of data. This is crucial for the continuous monitoring and control of microgrid operations [198]. Sensors combined with cloud computing can handle large volumes of data, providing a scalable solution for data processing and control in microgrids [199]. Dedicated solar sources can also be used to power wireless sensor networks for intelligent monitoring of isolated microgrids for energy scheduling using simultaneous wireless transmission of information and energy, but the problem of optimising scheduling and optimising the placement of photovoltaic cells needs to be solved here [200].

By optimising the use of renewable energy and improving the efficiency of energy management, sensors help in reducing operational costs and electricity bills [187,201]. Effective sensor-based monitoring and control systems contribute to minimising carbon emissions by ensuring the optimal use of renewable energy sources [201].

Developing fault-tolerant control strategies for sensors is essential to maintain robust performance and enhance the stability of microgrids [178]. Continuous advancements in sensor technologies, such as self-powered sensors and multi-parameter sensors, are expected to further improve the efficiency and reliability of microgrids [202].

In the context of future sensor technology solutions dedicated to microgrids, it is worth taking a look at the latest technologies that are currently being considered. One example is quantum sensors, which can provide unmatched levels of sensitivity, precision and durability. Their use is being considered in areas of urban infrastructure, including energy [203], and therefore they have potential applications in microgrids. In turn, microgrids in which energy use is linked, for example, to the presence of users or specific facilities, can utilise modern flexible sensor technology [204,205]. The growing number of sensors also increases the demand for energy to power them, which will increase the load on the microgrid itself. However, there is a solution here too, namely the noteworthy technology of self-powered sensors [206,207].

5.2. Fundamental Value of Sensor Technology in Improving Microgrid Efficiency

Microgrids need to be able to collect, process and respond to real-time data in order to maintain stable, reliable and cost-effective operations. Sensors provide the necessary data-driven information to enable intelligent decision-making in several operational aspects, from power generation to demand management. The value of sensor technology in enhancing microgrid performance manifests itself in the following aspects:

- Real-time monitoring and control—sensors can detect voltage or frequency fluctuations, providing early warning signals for control systems that can react proactively to avoid disruptions; by monitoring energy distributions, they help the management system optimise decisions regarding energy distribution and storage; monitoring environmental variables (e.g., humidity, temperature), ensures that equipment performance is maintained within optimum ranges, preventing overheating or degradation of the stability and efficiency of equipment components.

- Predictive maintenance and fault detection—by continuously tracking parameters such as system temperature, vibration and electrical anomalies, sensors can identify early signs of wear or malfunction in electro-environmental equipment (distribution, storage, generation and transformation of energy carriers); this data can be analysed using advanced machine learning algorithms to predict failures before they occur, enabling pre-emptive action rather than reactive repair, reducing downtime and extending the life of assets, resulting in cost savings and increased overall system efficiency.

- Demand response and load optimisation—in microgrids, managing energy consumption and matching it to supply is key to maintaining self-sufficiency and ensuring that resources are not over- or under-utilised; sensors in smart meters and IoT-enabled devices (sensors of energy parameters and parameters affecting energy consumption) allow demand management by providing real-time data on the energy consumption of homes or businesses and transmitting it to a smart energy management system (EMS) to optimise energy allocation and avoid overloading the microgrid, also reducing consumption during peak hours or shifting the load to periods with excess renewable energy.

- Renewable energy integration and forecasting—the predictive capability of sensor systems helps improve the integration of different energy resources. Sensors track weather patterns and environmental factors, providing accurate predictions of renewable energy generation. By integrating this data with energy management systems, microgrids can better predict the availability of renewable energy and adjust storage or consumption accordingly. Advanced algorithms, using sensor data, can further predict the output of renewable energy sources and adjust storage management strategies, increasing microgrid efficiency.

- Fault tolerance and grid resilience—sensor information enables rapid fault detection and self-repair of the microgrid; sensors can quickly identify the location of a fault and contribute to isolating it; sensors in the control system can provide signals to regulate network voltage and frequency in response to external disturbances or load changes. With a high-density sensor network across the microgrid, the system can automatically reconfigure itself to bypass faulty areas or sources of failure, thereby improving both resilience and performance, even under extreme conditions.

5.3. The Role of Sensors in Achieving Energy Self-Sufficiency in Microgrids

The use of sensor technology in microgrids not only improves their operational efficiency, but is also a key factor in achieving energy self-sufficiency. This involves the appropriate integration of various sensors into the smart grid structure in order to create intelligent security strategies capable of processing and analysing large amounts of data, which facilitates real-time decision-making and precise fault detection [208]. Sensors form the basis of this capability through the following mechanisms:

- Balancing local energy production and consumption—sensors enable microgrids to continuously measure in real time both supply (from PV systems, wind turbines, CHP, etc.) and energy demand (homes, industrial facilities, critical infrastructure) [209]. This data allows dynamic adjustment of microgrid operation and ensures that the energy produced is used locally with minimal losses.

- Real-time energy management—by integrating sensor data with EMS and SCADA systems [210], microgrids can automatically adjust the operation of energy sources, energy storage and loads, using the potential of users/flexumers.

- Efficient use of energy storage resources—sensors monitoring voltage levels and other operating parameters enable intelligent management of the charging and discharging cycles. Maintaining storage units in optimum operating conditions extends their lifespan and allows them to efficiently collect surplus energy from RES. [211].

- Autonomous response to disturbances—voltage, current, frequency and power quality sensors enable rapid fault detection and initiation of corrective action without the need for external intervention. In this way, the microgrid can autonomously maintain stable operation under fault conditions or disconnection from the master network. Synchronised sensor technologies help solve the event location identification problem, for different types of steady-state and transient events [212].

- Autonomous monitoring of microgrid operating parameters—measurement of electrical quantities (e.g., as part of smart metering) at selected locations, enabling estimation of operating conditions, maintenance of reliability and safety of energy use, minimisation of losses and location of faults [213].

6. Microgrids in a Transforming Energy Sector

6.1. Decarbonisation

Decarbonisation of the economy is a global trend, especially in developed countries, due to the inclusion of carbon footprints in economic calculations and the possibility of gaining a competitive advantage in ‘green’ investments. Full decarbonisation is possible, but difficult in terms of full technical and organisational implementation. In this respect, microgrids can be a tool for decarbonisation, as a place for the application of zero-emission technologies, the electrification of various branches of the economy and means of production. Optimisation in microgrids through EMS promotes energy efficiency by reducing the demand for energy from non-renewable sources, leveraging energy storage and load management.

In the context of the ongoing development of microgrids and their anticipated role in future power grids, the plan for developing new solutions can be divided into three closely related areas: (1) integration of energy storage systems (EES) in microgrids and power plants, (2) active demand management, and (3) improvement of microgrid control and monitoring capabilities [126]. All these tasks can be carried out in such a way that energy based on microgrid structures does not depend on fossil fuels.

Microgrids play a positive role in the decarbonisation of the energy sector, enabling greater penetration of renewable energy sources and reducing dependence on fossil fuels [214]. The use of renewable energy sources in microgrids contributes to the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and supports global sustainable development goals [215]. For example, the microgrid project for KENTECH in South Korea aims to achieve up to 100% self-sufficiency and a 60% reduction in CO2 emissions [216]. Simulations of microgrid operation confirm the effectiveness of such a structure as a tool for reducing CO2 emissions [217,218].

Advanced energy storage solutions help capture and utilise energy during peak production periods, ensuring a reliable power supply even when renewable energy sources are unstable [219].

Microgrids are composed of different distributed energy resources, which are operated differently from individual sources. Studies presented in the literature, e.g., [220] shows the theoretical maximum benefits of microgrids (with own renewable energy sources) in energy efficiency improvement and GHG emissions reduction compared to conventional energy supply systems.

Support for decarbonisation through electrification within an industrial microgrid may consist, in particular, of:

- Using heat pumps instead of fossil fuels to produce low- and medium-temperature indirect heat.

- Using electrolysers to produce hydrogen from water electrolysis instead of natural gas.

- Electrification of transport within the area covered by the microgrid.

Another goal of decarbonisation is related to sustainable development and improving competitiveness. Here, too, EMS tools come into play. This involves intelligent management of zero-emission resources, optimisation to improve energy efficiency, and the use of price arbitrage to reduce energy costs. Own generation near consumption points means independence from energy supplies from the power system and external commodity markets, as well as reduced energy transmission losses. All this contributes to lower operating costs and thus improves competitiveness. In addition, thanks to the flexibility of energy resources integrated into microgrids, it is possible to provide additional services to the power grid and generate income (Table 9).

Table 9.

Decarbonisation objectives affecting sustainability that can be pursued by the microgrid.

In the context of energy transition, it is worth noting the characteristics of a hybrid microgrid, namely that thanks to control systems and EMS, such a structure does not operate chaotically, but thanks to adapted inverters, especially GFM (Grid Forming Inverter) type, which simulate the operation of a physical synchronous machine and, in cooperation with energy storage, can become a reservoir of artificial inertia for the power system.

Furthermore, generators used in microgrids, operating in cogeneration and biogas systems, are usually synchronous machines, i.e., they provide inertia [221]. These systems are also sources of short-circuit power, which translates into grid resilience. Therefore, a properly constructed and managed microgrid has the potential to support the power system in its normal operation and in emergency situations. Inertia resources are particularly desirable in systems with high RES generation (mainly PV), where traditional units based on synchronous generators, connected directly to the grid, are being replaced by units connected to the grid via inverter systems.

This issue is related to the problem of changing the operating paradigm of electricity network operators, both distribution and transmission. In a structure consisting of autonomous microgrids connected by distribution lines, the operator will be a neutral, physical aggregator of these microgrids, maintaining system traffic within a given area. The operator will manage the energy exchange platform between prosumers or microgrids [222]. One of the major advantages interconnected microgrids offer is the distributed structure, which improves the reliability of the distribution network [223].

6.2. Integration of Different Energy Technologies

6.2.1. Overview

A microgrid can combine different energy technologies and can be considered at various stages of energy transformation—from generation through distribution to the obvious end use of energy. In terms of electricity, both AC and DC distribution technologies can be used within it. Integration can also involve combining different energy carriers, including within polygeneration.

The integration of different energy technologies in microgrids refers to the structured incorporation of multiple technologies into a single, coordinated system that can operate both in connection with the main grid and independently. Despite its limited size, the structure can combine multiple technical and organisational solutions. Technology integration can take place at the level of energy generation, storage, distribution and conversion, as well as billing for usage [224]. These technologies are coordinated to optimise the efficiency, reliability and sustainability of the local energy supply system. This integration is facilitated by advanced power converters and energy storage devices, which increase the efficiency and reliability of microgrids [225,226]. In a microgrid that interconnects various power generation systems utilising different technologies and power capacities, it is essential to adopt a hierarchical control framework aimed at reducing operational costs while enhancing efficiency, reliability, and controllability [126].

Microgrids facilitate the integration of renewable energy sources such as solar, wind and biomass, which are essential for reducing carbon dioxide emissions and achieving sustainable development goals [47,76]. For example, a typical microgrid may use photovoltaics and wind turbines for primary renewable energy generation, diesel generators for backup, batteries for energy smoothing and peak load reduction [227], and Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) systems to handle bidirectional energy flows as an additional form of storage [228]. In addition to battery management, hydrogen fuel cells are used as long-term, clean, backup power sources. Batteries and hydrogen storage facilities help manage the instability of renewable energy supplies and ensure a stable power supply [229,230]. The aim is to ensure stable, resilient and low-carbon local energy systems that can adapt to changing load requirements and generation profiles [1,88,231].

Active cooperation with the network or island operation requires flexibility in both generation units and consumption. Such a structure requires intelligent management; hence, the microgrid management system is a crucial component [53]. Hybrid AC/DC architectures enable simultaneous operation of AC and DC systems, facilitating the effective integration of a wider range of technologies [55]. Networked or clustered microgrids enable energy sharing between multiple microgrids, further increasing reliability and enabling greater participation of renewable energy sources [232].

Intelligent management of an extensive microgrid, collecting data from multiple sensors, and the operation of a management system that maintains energy balance in conditions of variable consumption and generation from renewable energy sources requires real-time data analysis. Edge computing, i.e., a model of local data processing on end devices, network gateways or microservers, can be used here, which significantly reduces delays [233]. Edge computing assists in real-time energy management, load balancing, and proactive maintenance of renewable energy sources like solar panels and wind turbines [234]. In [235], a microgrid-oriented architecture was proposed, including edge-cloud collaboration for data processing, network communication, and security mechanisms, demonstrated in a rural community in Central China.

The development of advanced control strategies, including artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML), is crucial for optimising the operation of microgrids. These technologies enable real-time monitoring, predictive maintenance and adaptive control, thereby improving the stability and resilience of the network [236]. The increasing digitisation of building management and the transition to smart grids are improving the assessment and optimisation of energy efficiency in real time in microgrids [237,238]. New technologies such as artificial intelligence and quantum computers are expected to further optimise energy management and increase the capabilities of microgrids [239]. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are increasingly being used for energy management, improving the efficiency and reliability of microgrids by predicting energy demand and optimising resource allocation [240]. Modern microgrids use smart grid technologies, peer-to-peer energy markets, and advanced energy management systems to optimise efficiency and effectively integrate different energy sources [47,241].

An analysis of the operation of microgrids using artificial intelligence, including an analysis of bottlenecks and trends in the development of artificial intelligence, together with a proposal for an artificial intelligence application system enabling the smart microgrids, the main element of which is a digital twin, is presented in [242].

AI-based control strategies, such as adaptive learning and distributed control architectures, increase the resilience and sustainability of microgrids. These strategies support predictive energy management and intelligent decision-making processes. A review of recent research [243] highlights the effectiveness of artificial intelligence in overcoming key challenges related to the operation and management of microgrids. These include distributed control strategies, intelligent decision-making processes supported by advanced algorithms, and communication frameworks. The current state of AI use in microgrid management, based on an analysis of 187 relevant articles in the Scopus database, indicated that India, China and the United States have made the greatest contribution to research in this area [244]. Adaptive systems and optimisation algorithms are key research topics in this field.

An example of the implementation of a proactive energy management system in a microgrid in tribal settlements in India, with IoT components providing real-time data on energy production and consumption and using AI techniques, to forecast weather conditions, is described in [245]. The AI-machine learning-based management system controls resources between solar and biodiesel systems, with surplus energy stored through hydrogen production by electrolysis. The design has enabled a reduction in CO2 emissions of 11,680 kg and savings of 46 tonnes of carbon per year.

Based on a review of 200 scientific papers, research and a review of solutions for the implementation and optimisation of microgrid energy management systems (EMS) using artificial intelligence (AI) were presented in [246]. The research highlights the importance of hybrid systems, demand management and energy storage in addressing the instability of renewable energy sources, which will improve the sustainability of microgrids. The importance of deep learning methods for load forecasting and reinforcement learning for control optimisation has been emphasised.

The authors of the paper [247] analyse the role of AI in various areas of microgrids, such as design, where the emphasis is on optimal scaling; control, where a hierarchical structure is used; and maintenance, including condition monitoring, diagnostics and forecasting. The article also highlights the integration of the Internet of Things (IoT) to improve connectivity and data exchange, and blockchain technology to enhance cybersecurity.

The concept of blockchain in the energy sector is gaining popularity, offering new opportunities for secure and efficient energy transactions, including within microgrids [248,249,250,251]. The development of renewable distributed sources and microgrids requires a secure and transparent transaction system in which blockchain technology enables real-time peer-to-peer (P2P) exchanges between users without intermediaries. However, this carries the risk of attacks (so-called 51% attacks), in which a single entity can gain majority control over the network and manipulate transactions, energy production and consumption data, and even lead to instability in energy supply at the community level [252]. The paper [253] proposes the integration of a hybrid Proof of Work_Proof of Stake (PoW/PoS) consensus mechanism with a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model to detect anomalies in blockchain-based microgrids in order to address issues in blockchain systems such as 51% attacks, double spending and high energy consumption, by optimising energy consumption and increasing security.

In the context of applying blockchain technology to peer-to-peer energy trading within microgrids, the article [254] discusses the necessary actions and implementation efforts in the areas of pricing mechanisms, privacy constraints, scalability, and the requirements of an overarching energy management system. The feasibility of the market mechanism and settlement process for direct electricity transactions between distributed generation units and consumers based on blockchain technology in the specific case of microgrids was presented in [255]. The issue of generation distribution and prosumption is linked to the problem of effective financial settlements between users within cooperating structures such as microgrids. Dedicated cryptocurrencies linked to renewable energy flows may prove to be an innovative solution [224].

Practical challenges related to the integration of technology within microgrids include [13]:

- Power quality, voltage, and frequency must be maintained within defined thresholds.

- Intermittent DERs may not provide consistent output, requiring more energy storage devices, which in turn demand additional space and frequent maintenance.

- Reconnecting and coordinating the microgrid with the main grid after a fault is a significant technical hurdle.

- Developing a reliable protection system poses a major engineering challenge.

- Microgrid performance can be negatively affected by net metering and idle costs.

- Appropriate standards for interconnection need to be developed.

Depending on the degree of development of the microgrid, various telecommunications technologies related to the transmission of measurement data and control signals can be used and integrated within its structure. The selection of communication technologies for microgrids in remote, residential, and rural regions is primarily determined by deployment costs and data transmission rates. Technologies such as WiFi, Bluetooth, Z-Wave, and Zigbee are commonly employed in these settings. Additionally, passive optical networks, along with 4G or 5G technologies, are utilised in microgrids serving public utilities [20].

The sensor nodes can utilise short-range wireless communication for information transmission. A Zigbee self-network is capable of performing data acquisition, storage, and communication in complex environments. The GPRS network facilitates data transmission between the aggregation node and the data monitoring centre. The microgrids monitoring centre is equipped with a database and microprocessor to store all collected data, analyse it, process the information, and support decision-making [256].

6.2.2. Analytical Perspectives

In the context of microgrid applications, the integration of sensor technologies, optimisation algorithms, and energy storage systems (ESS) is crucial for ensuring efficiency, resilience, and sustainability. To achieve these objectives, it is essential to employ analytical perspectives that focus on monitoring, controlling, and optimising the interactions between these components in real-time.

Contemporary sensor portfolios span tightly time-synchronised phasor measurements (μPMUs), high-resolution inverter telemetry, smart meters and breaker/relay status, and an array of asset-level sensors that monitor cell voltage, temperature, and other health indicators. Exogenous sensing—irradiance, wind, ambient temperature, EV arrival events, and market signals—completes the picture required for predictive control.

Classical topology-aware placement techniques should be augmented with control-aware value-of-information: sensors placed not merely to minimise state estimator variance, but to maximise expected closed-loop performance (reduced constraint violation probability, lower energy cost, or reduced battery ageing). Time synchronisation, streaming quality checks, and compression/error-bounded transport protocols are essential to preserve the information content that advanced state estimators and controllers expect. Sensors should be placed where closed-loop performance sensitivity is highest. For example, installing μPMUs at nodes whose voltage or phase angle uncertainty has the largest effect on constraint violations or reserve activation accuracy maximises the operational return on sensing investment.

At the algorithmic level, state and parameter estimation must fuse heterogeneous streams under nontrivial physics. Anomaly classification—distinguishing sags, transients, cyber intrusions, and equipment faults—benefits from waveform analytics and model-based residuals that can be used to switch control modes (for instance, invoking conservative reserves or islanding) when trust in telemetry drops.

Real-time twins calibrated with live telemetry enable rapid validation of control policies, including injection of sensor faults and cyberattacks to test graceful degradation strategies. Twins also allow surrogate model validation and derivation of trust regions where lower-order models are acceptable.

The energy storage systems (ESS) portfolio for microgrids is diverse: Li-ion variants (LFP, NMC, LTO) offer high power density and fast response; flow batteries and hydrogen enable long-duration storage; supercapacitors and flywheels address sub-second stabilisation. Inverters can operate in grid-forming or grid-following modes, and ESS play roles ranging from synthetic inertia and fast frequency response to arbitrage and black-start capability. Hybrid ESS (HESS)—combining fast, low-energy devices (supercaps) with slower, high-energy batteries—is an effective architectural pattern. Optimal power/energy splitting between components is framed within joint model predictive control formulations that explicitly minimise a weighted sum of operational cost, service shortfall risk, and degradation. Co-sizing problems, solved in planning stages, are multi-objective: capex, life-cycle cost, and emissions must all be balanced.

Optimisation for resilience is mixed integer in nature (sequence scheduling, feeder energisation order) but can be relaxed into tractable approximations or solved offline to produce fast, precomputed plans for emergency use. Rigorous evaluation must report operational, economic, asset, and cyber-physical key performance indicators (KPIs): energy not supplied, frequency/voltage violation rates, reserve activation accuracy, total cost (including degradation), battery life consumption, thermal excursions, and detection delays/false positive rates for sensor anomalies. Comparative ablations—with and without μPMUs, with centralised versus distributed optimisation, with and without degradation-aware dispatch—reveal the true value of the integration. Hardware-in-the-loop tests and digital-twin stress scenarios (sensor dropout, spoofing, high-renewable ramps) should be standard practice prior to field rollout.

High-quality, time-synchronised sensing unlocks the observability required for advanced estimators; those estimators enable model predictive and robust optimisation that properly account for uncertainty and asset degradation; and these optimisation decisions realise the operational value of ESS while preserving their life. The engineering objective is therefore holistic co-design: place and secure the measurements that matter, choose models and algorithms with the right fidelity for each time scale, and embed degradation and resilience explicitly in dispatch.

6.3. The Question of Energy Self-Sufficiency Through Microgrids

6.3.1. Comprehensive Framework

Microgrids play a key role in achieving energy self-sufficiency, increasing resilience and promoting environmental sustainability. By utilising local renewable energy sources and advanced energy management systems, microgrids can provide reliable and cost-effective energy solutions tailored to the specific needs of areas and regions [52,216,219]. These features together provide microgrid users with reliable and efficient energy supplies, making them virtually self-sufficient in terms of energy [59,257,258].

The issue of energy self-sufficiency through microgrids can be considered on two levels: systemic and local-individual. The individual level is related to the supply of energy to consumers within the microgrid’s area of operation from its own local sources and energy storage facilities. The system level is related to the possibility of utilising the potential of intelligently controlled microgrids in terms of their flexibility and generation from various sources to support the functioning of the system to which the microgrid is connected.

The main advantage of microgrids is their ability to generate and consume energy locally, which reduces the need for long-distance electricity transmission and increases energy efficiency [257,259]. This local generation capacity is crucial for maintaining a high level of self-sufficiency, especially in remote or isolated areas [258,260]. By generating and storing energy locally, microgrids can reduce energy costs and provide economic benefits to communities and businesses [52,261,262].