Abstract

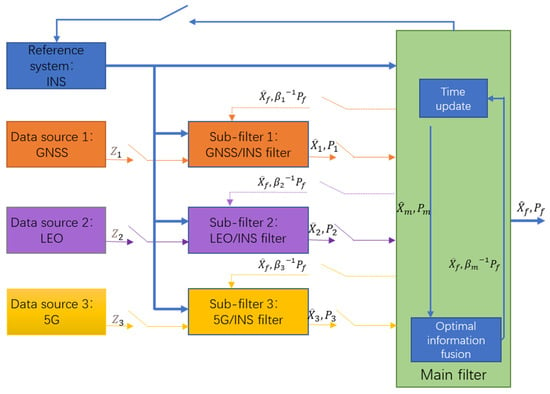

This article examines the positioning effect of integrated navigation after adding an LEO constellation signal source and a 5G ranging signal source in the context of China’s new infrastructure construction. The tightly coupled Kalman federal filters are used as the algorithm framework. Each signal source required for integrated navigation is simulated in this article. At the same time, by limiting the range of the azimuth angle and visible height angle, different experimental scenes are simulated to verify the contribution of the new signal source to the traditional satellite navigation, and the positioning results are analyzed. Finally, the article compares the distribution of different federal filtering information factors and reveals the method of assigning information factors when combining navigation with sensors with different precision. The experimental results show that the addition of LEO constellation and 5G ranging signals improves the positioning accuracy of the original INS/GNSS by an order of magnitude and ensures a high degree of positioning continuity. Moreover, the experiment shows that the federated filtering algorithm can adapt to the combined navigation mode in different scenarios by combining different precision sensors for navigation positioning.

Keywords:

integrated navigation; federated filtering algorithm; GNSS; INS; LEO; 5G; tightly coupled; simulation experiment; NPI 1. Introduction

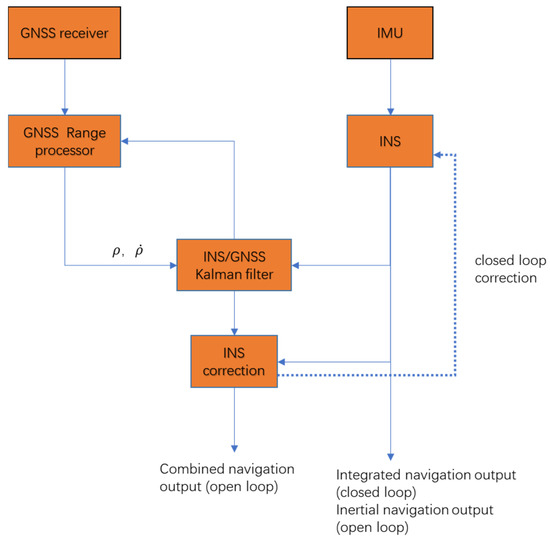

Compared with early navigation methods, modern navigation has entered the information age centered on integrated navigation systems. The integrated navigation system is also called multi-sensor information fusion. According to different task scenarios, using multiple sensors for integrated navigation and optimally fusing multiple types of information according to a certain optimal fusion criterion can be expected to improve positioning accuracy. Commonly used single-sensor navigation methods today include the Inertial Navigation System (Inertial Navigation System, INS), which has autonomous navigation capabilities, but INS positioning error drifts greatly over time [1]. The other one is the Satellite Navigation System (Global Navigation Satellite System, GNSS), which has all-weather, high-precision positioning ability. However, GNSS has the shortcomings of insufficient satellite signal reception and an instantaneous increase in positioning error when the signal is blocked [2]. Integrated navigation is designed based on the complementary performance of a single navigation system; that is, the combination of GNSS/INS can achieve autonomous and high-precision navigation and positioning to a certain extent [3,4]. This combination method has been studied in academia and has been applied in industry. However, in areas such as tall buildings, or tunnels and mines, GNSS signals cannot be received for a long time, and at the same time, the INS positioning error drifts greatly. For example, under the mine, there is no GNSS signal, and it needs to rely on INS for a long time. However, the positioning error of tactical IMU will drift to about 10 m within one minute [5]. In this context, this article proposes to use Low Earth Orbit constellation enhancement and 5G signals as new sensor signal sources for integrated navigation simulation experiments to solve the positioning failure caused by the lack of GNSS signals in specific areas.

Since 2020, the discussion of “new infrastructure” in China has heated up dramatically. As can be seen from relevant research reports [6,7], in the new infrastructure, both satellite internet and 5G infrastructure construction can be used as a National Positioning Infrastructure (NPI).

Satellite internet projects such as Telesat, OneWeb, and Starlink are mainly distributed in the orbit altitude range of 400 km to 1400 km. In China, constellations represented by “Hongyan Constellation”, “Hongyun Project”, “Xingyun Project”, “Celestial Constellations”, and “Milky Way 5G” were designed with heights ranging from 500 km to 1200 km. The above satellite constellations can all be called Low Earth Orbit Satellite Systems (LEO). Nowadays, the accuracy of low-orbit satellite orbit calculation can reach the centimeter-level [8,9,10]. The satellite launch and networking technologies have become more mature so that the number of available satellites has greatly increased, and some technical problems of low-orbit satellite navigation algorithms have been solved. Combining satellite load and application requirements, designing a low-orbit constellation that can be used for navigation, and forming a low-orbit constellation with integrated communication and navigation is an inevitable trend of constellation development [11,12,13]. At the same time, the research of combining LEO and INS for navigation is in the ascendant. Existing research shows that when there is no GNSS signal, the accuracy of integrated navigation using LEO constellation signal and INS is obviously higher than that using INS alone. This proves that using LEO/INS is feasible [14]. Taking advantage of the fast speed of LEO satellite, Doppler frequency shift measurement and positioning technology can be used in LEO satellite. The effect of tight coupling between this technology and INS is also very good, when GNSS is unavailable for 30 s, the final error is reduced from 31.7 m to 8.9 m [15,16,17,18].

As another main component of the new infrastructure, the 5th-generation mobile communication system (5th-generation, 5G) is widely regarded as the foundation of the new generation of the internet. The Internet of Things and Industrial Internet based on 5G have also received widespread attention [19]. The international standards organization 3GPP (3rd Generation Partnership Project), which is leading the 5G communication system protocol standard, has formally defined the commercial application scenarios of 5G positioning requirements in the TR22.872 standard [20]. The use of 5G communication systems for indoor and outdoor positioning is a current research hotspot. Indoor and outdoor positioning algorithms based on the characteristics of 5G millimeter-wave signals have also been extensively studied, and the existing algorithms have reached sub-meter positioning accuracy [21,22,23]. Hybrid positioning schemes based on the fusion of 5G cellular, GNSS/INS are to be studied and developed towards a universal solution for robust positioning of aerial or ground vehicles in urban, rural, and indoor scenarios [24]. Studies have also shown that positioning 5G base stations on both sides of the expressway can improve the robustness and accuracy of the car navigation system on the road [25]. The research of indoor and outdoor joint positioning using 5G shows that when there is no GNSS signal, it is a good choice to use 5G signal instead. Although there have studies use federated filtering, INS is not used as a reference system [26,27]. These studies show that integrated navigation using new sensors needs to be more comprehensive.

In the above context, this article finds that algorithm research and technical application of combined GNSS/INS/LEO/5G navigation and positioning are ascendant in the existing research. Therefore, based on the new sensors included in the new infrastructure, this article proposes implementing a GNSS/INS/LEO/5G integrated navigation simulation experiment by using a federated filtering algorithm to verify the feasibility and positioning accuracy of different integrated navigation positioning schemes.

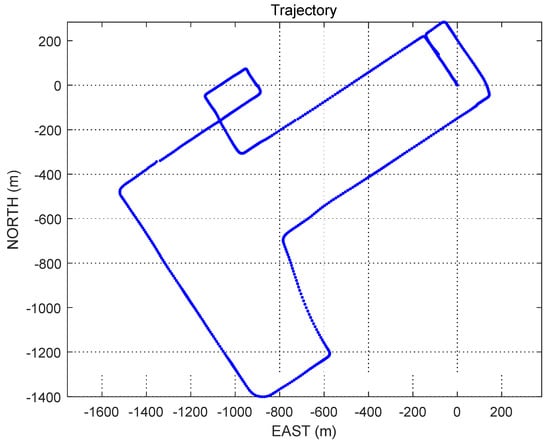

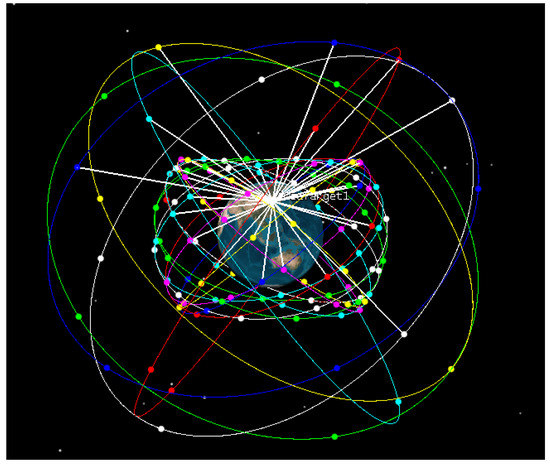

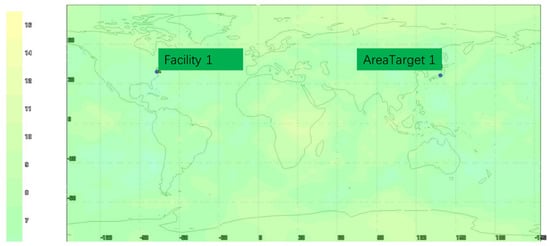

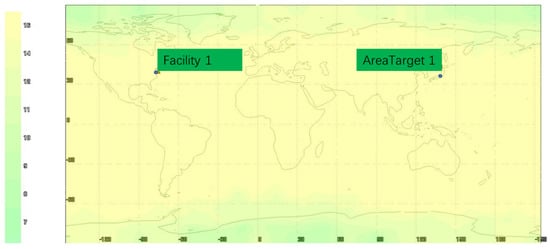

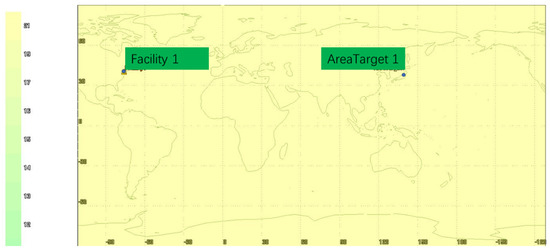

The integrated navigation simulation verification scheme in this article uses GNSS and LEO satellite constellations simulations to derive the satellite position and speed in the simulation time, which is used as the data source for the integrated navigation satellite positioning. The IMU error model is used to build IMU output specific force and angular velocity models, which are used for integrated navigation, as the INS’s data sources. The 5G ranging signal is simulated by adding random noise based on the given theoretical coordinates of the base station and receiver, based on the 5G ranging signal error model, to provide the ranging value of the 5G signal. Through the implementation of a federated filtering algorithm, the combined navigation and positioning results of the above multi-source signals are output and compared with the true value to verify the navigation and positioning accuracy.

The structure of this article is as follows. The first section is the introduction; the second section introduces the algorithm model used in this article, including algorithm structure frame, simulation scene construction, and simulation method of each signal source; in the third section, the experimental results are compared and explained; finally, in the fourth section, the author puts forward the summary and conclusions of this article. The potential innovations of this article are as follows: simulation verifies the advantages of new integrated navigation using LEO constellation and 5G over traditional integrated navigation; the applicability of the new integrated navigation proposed in this article is presented for the positioning effect in different scenarios. A proposal of information factor allocation using a federated filtering algorithm is proposed when different precision sensors are used.

3. Experimental Results

3.1. Comparison of Location Results in Different Scenarios

After setting parameters in different scenarios, the results of the simulation experiment are as follows. Note that FNR mode is adopted for federated filtering in this section.

3.1.1. Open Scene

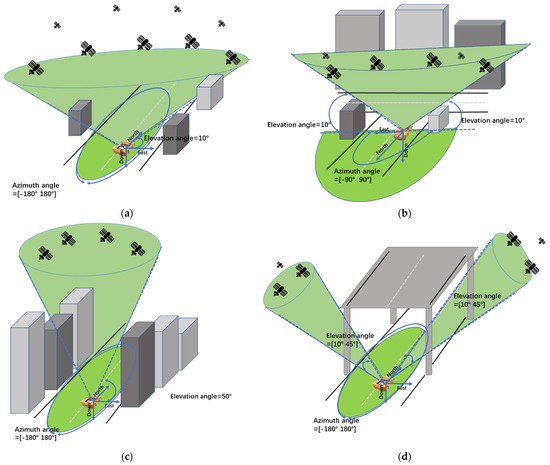

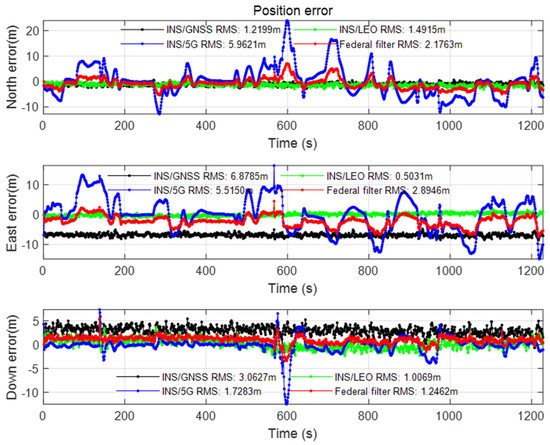

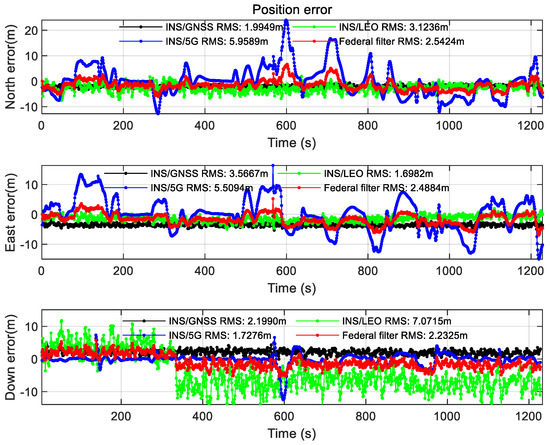

The positioning result after setting the azimuth angle and mask angle of the open scene in Section 2.2 is shown in the figures below.

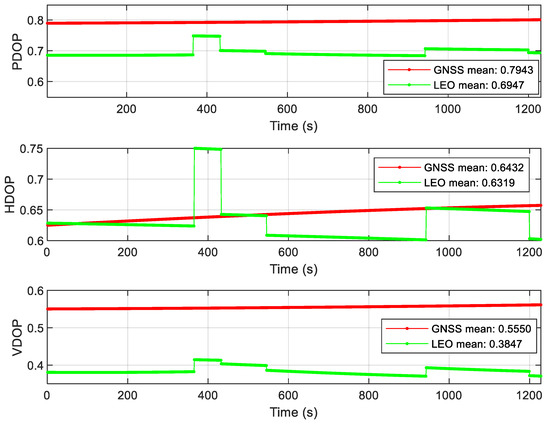

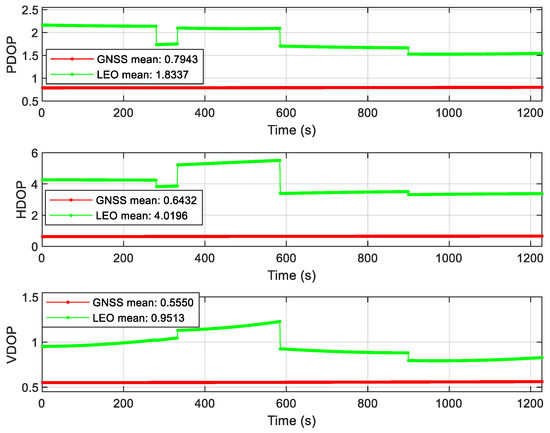

As can be seen from Figure 9, after the LEO constellation was introduced in the open scene, the LEO/INS position accuracy increased by an order of magnitude to sub-meter in the east direction compared with GNSS/INS position accuracy. Affected by the poor accuracy of 5G/INS position, the overall federated filtering accuracy is in meter level, but it is higher than the accuracy of single 5G/INS position, and the positioning error is more stable than 5G/INS, the positioning convergence speed is faster, and the positioning continuity is more guaranteed. According to the DOP value analysis of GNSS and LEO constellations in Figure 10, it can be seen that the geometric distribution of the LEO constellation is significantly improved compared with that of the GNSS constellation. The results of velocity error and attitude error of the Open scene can be seen from Figure A1 and Figure A2 in Appendix A. The error values after using the federated filtering algorithm in this article both are relatively stable.

Figure 9.

Position error of the Open scene.

Figure 10.

DOP value of the Open scene.

3.1.2. Semi-Occluded Scene

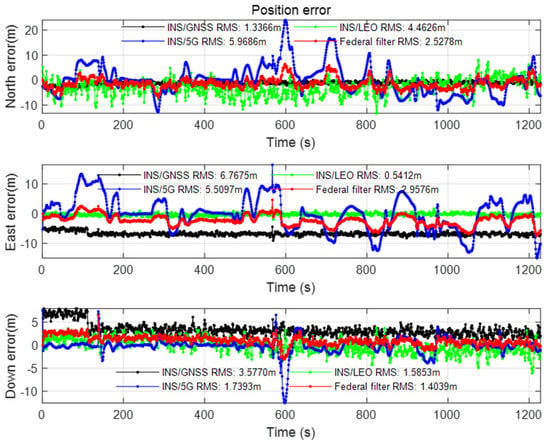

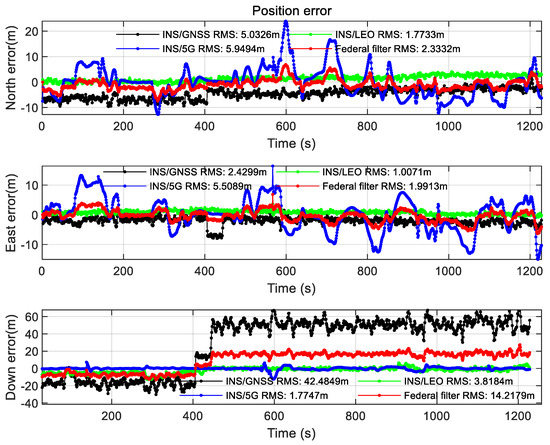

The positioning result after setting the azimuth angle and mask angle of the semi-occlusion scene in Section 2.2 is shown in the figure below.

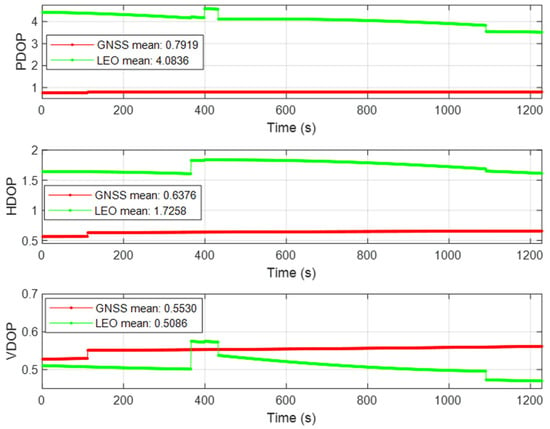

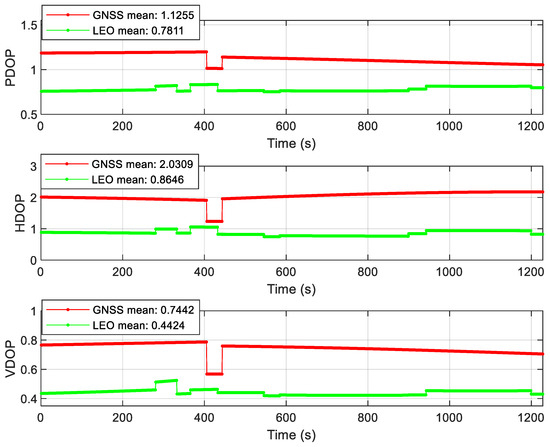

It can be seen from Figure 11 that in the Semi-occluded scene, because the azimuth range is reduced by half compared with the Open scene, the positioning accuracy of LEO/INS has obvious influence, and the position error in the north direction is significantly larger than that of GNSS/INS. It can be seen from Figure 12 that the geometric configuration of the LEO constellation in the Semi-occluded scene is obviously worse than that of GNSS in three-dimensional position and horizontal position, which further affects the positioning accuracy of LEO. Due to the influence of high orbit height, the positioning accuracy in the semi-occluded scene has little influence on the GNSS constellation. Due to the better fault tolerance of the federated filtering algorithm and the visible feature of the 5G base station, the 5G ranging data used in this paper is not occluded, so 5G/INS positioning is used as a supplement, which makes the positioning accuracy of the whole federated filtering about 2 m. The results of velocity error and attitude error of the Semi-occluded scene can be seen from Figure A3 and Figure A4 in Appendix A. The fluctuation of velocity error and attitude error of the Semi-occluded is larger than the value in the Open scene.

Figure 11.

Position error of the Semi-occluded scene.

Figure 12.

DOP value of the Semi-occluded scene.

3.1.3. Surrounding Occluded Scene

The positioning results are shown in the figure below after setting the azimuth and mask angle of the Surrounding occluded scene in Section 2.2.

As can be seen from Figure 13, under the influence of the increase of mask angle, the LEO/INS positioning accuracy becomes worse, but the accuracy after GNSS/INS filtering is improved. The overall accuracy after federated filtering is about 2 m. As can be seen in Figure 14, in the Semi-occlusion scenario, the geometric configuration of the LEO constellation is greatly limited due to the high mask angle limit. The results of velocity error and attitude error of the Surrounding occluded scene can be seen from Figure A5 and Figure A6 in Appendix A. The error value of the sub-filter will be reduced after using federated filtering.

Figure 13.

Position error of the Surrounding occluded scene.

Figure 14.

DOP value of the Surrounding occluded scene.

3.1.4. Headspace Occluded Scene

The positioning result after setting the azimuth angle and mask angle of the headspace occluded scene in Section 2.2 is shown in the figure below.

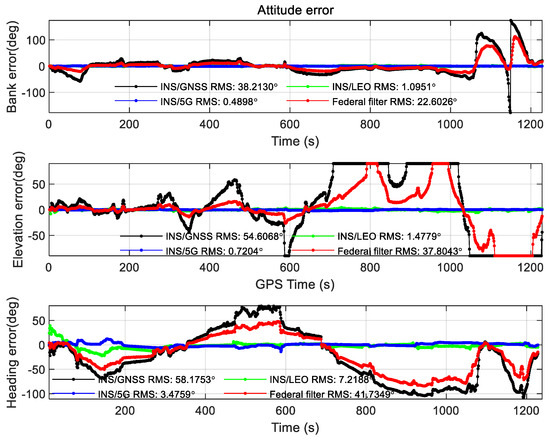

As can be seen from Figure 15, under the Headspace occluded scenario, the GNSS constellation is limited by the range of mask angle, so the GNSS/INS positioning error increases by one order of magnitude in the celestial direction. The LEO constellation geometry has an obvious advantage in this scene, so the positioning error is not affected. Due to the geometric configuration advantage of the LEO constellation, the positioning accuracy of the federated filter is higher than that of GNSS/INS in this scene. As can be seen from Figure 16, the DOP value of the GNSS constellation in the Headspace occlusion scenario is significantly higher than that of the LEO constellation. The results of velocity error of the Headspace occluded scene can be seen from Figure A7 in Appendix A. The velocity error of INS/GNSS positioning has obvious fluctuation, and the fluctuation of attitude error has exceeded the acceptable range. The attitude angle error increases by one order of magnitude which can be seen from Figure A8 in Appendix A.

Figure 15.

Position error of the Headspace occluded scene.

Figure 16.

DOP value of the Headspace occluded scene.

It can be seen from the positioning results in Section 3.1, the positioning errors and constellation DOP values are quite different in different scenarios. The positioning results of the federated filtering algorithm in FNR mode are compared in the following table.

In Table 6, this subsection compares the positioning results of four scenes. Experiments show that GNSS/INS, LEO/INS, and 5G/INS alone have poor positioning accuracy in a certain scene. However, by using the federated filtering algorithm, the positioning accuracy can be stabilized. At the same time, by comparing the positioning results in different scenarios, it can be found that the convergence effect of the federated filtering positioning results after the introduction of LEO constellation and 5G signals is more stable and faster than GNSS/INS. Plus, the positioning continuity is better guaranteed. In particular, the LEO/INS positioning effect is better in the Headspace occlusion scene.

Table 6.

Positioning results.

3.2. Comparison of Different Information Factor Allocation and Location Results of Different Modes for Federated Filtering

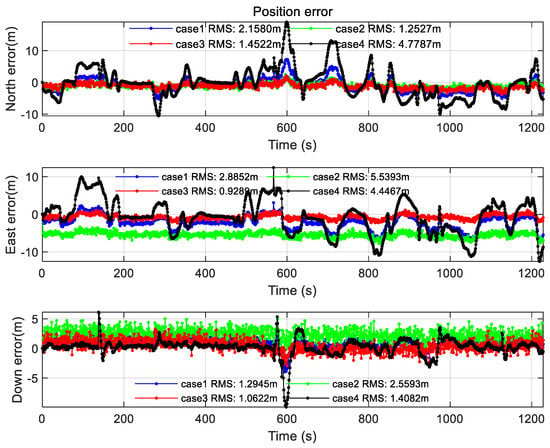

After comparing the positioning accuracy of integrated navigation in different scenes according to the different performance of positioning accuracy of GNSS, LEO, and 5G signals, we conclude that different sensors can be set with different information factors. So, the next experimental comparison can be made to verify the influence of information factor allocation of federated filtering in the same mode on positioning accuracy. Therefore, in the Open scene, the experimental results of different information factors under the FZR mode of federated filtering are compared, as shown in the following figures.

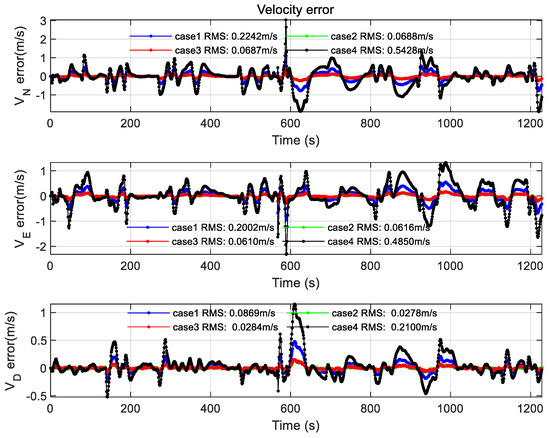

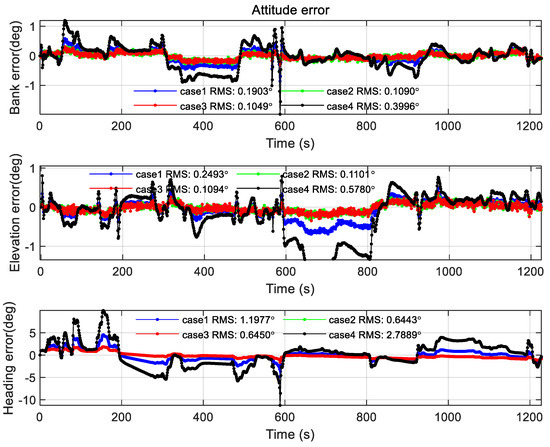

In Figure 17, the position error of different information factors is shown. The velocity error and attitude error can be seen from Figure A9 and Figure A10 in Appendix A. The values of different information factors can be seen in the following table.

Figure 17.

Federated filtering position errors of different information factors.

As shown in Table 7, if a sub-filter positioning accuracy is higher than several orders of magnitude than another sub-filter, the information factor ratio of this sub-filter needs to be close to 1. The above conclusion can be seen from the compared simulation results. In this way, the positioning results of federated filter can be significantly improved. It can be seen from Figure 17, since the LEO/INS positioning accuracy is higher than GNSS/INS and 5G/INS, Case3 can improve the overall positioning accuracy by increasing the proportion of the LEO/INS information factor to 80%.

Table 7.

GNSS/INS, LEO/INS, and 5G/INS sub-filter information factor ratio.

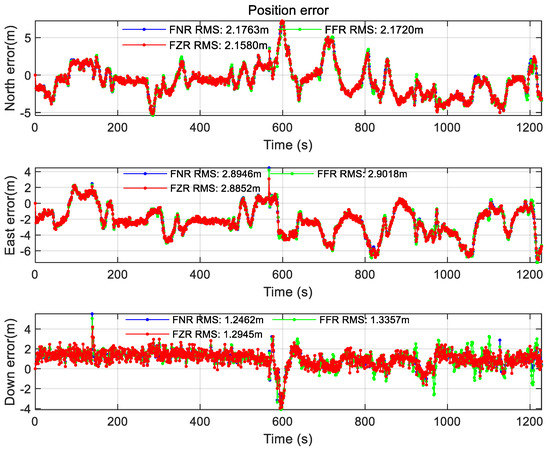

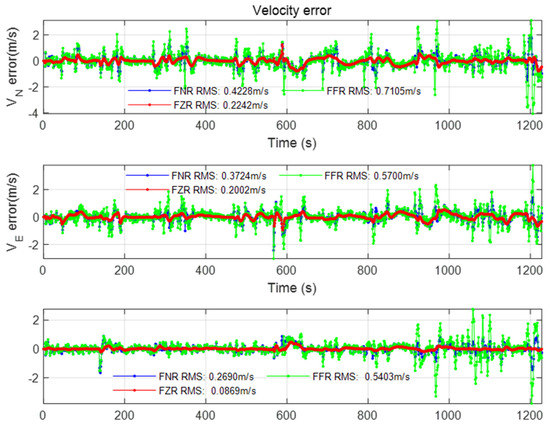

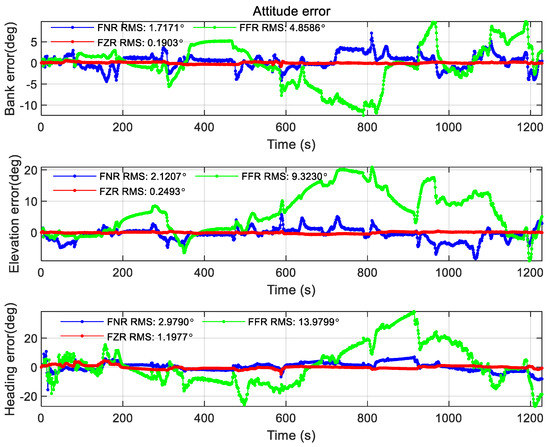

At the same time, this paper also compares the federated filtering positioning accuracy of different modes under the same scale factor (using the percentage in Case1), as shown in the figure below.

From the comparison of Figure 18, Figure 19 and Figure 20, it is found that the federated filter under different modes has no obvious difference in position error. However, the FFR mode performs poorly in speed error and attitude angle error, which is reflected in the large error fluctuations, and the attitude angle error reaches 10° in magnitude. After analysis, it is considered that the filter in this paper adopts the error state vector model, and different modes have different ways to deal with the covariance matrix. The covariance matrix of FFR mode feedback leads to the instability of the sub-filter, which leads to the speed error increasing to the level of 1 m/s after 100 s and the attitude angle error increasing to the level of 10° after 200 s. FNR mode does not affect the sub-filter, so the positioning result has no influence. The velocity error in FNR mode is less than 0.5 m/s, and the attitude angle error is less than 2.5°. The FZR mode resets the covariance matrix of the sub-filter, so the error of velocity and attitude angle does not change much. The velocity error is less than 0.3 m/s and the attitude angle error is less than 1.2° in the FZR mode.

Figure 18.

Position error of different mode federated filtering.

Figure 19.

Velocity error of different mode federated filtering.

Figure 20.

Attitude error of different mode federated filtering.

In this subsection, the positioning results under different federated filtering modes are compared, and it is found in the experiment that FZR mode and FNR mode have less influence on the sub-filter covariance matrix than FFR mode, and the positioning accuracy is better.

In Section 3, by comparing positioning results in different scenarios, positioning results in different information factors, and positioning results in different federated filtering modes, it is found that higher information factors should be set for sensors with higher accuracy according to different application scenarios. If the error state vector modeling is adopted, the FNR and FZR mode positioning results of federated filtering are better.

4. Conclusions

In this work, INS, GNSS, LEO, and 5G signal sources were simulated, and integrated navigation simulation experiments were carried out using tightly coupled and federated filtering algorithms. By setting the azimuth angle and the satellite visible altitude angle, the positioning results in four occlusion scenes, namely, Open scene, Semi-occluded scene, Surrounding occluded scene, and Headspace occluded scene, are compared. The main conclusions that the paper can support are as follows: (1) the experimental results show that, after adding the LEO constellation, the geometric configuration of the LEO constellation can significantly improve the accuracy factor, which provides strong support for the positioning effect of the Headspace occlusion scene, and improve the positioning accuracy of the original INS/GNSS by an order of magnitude; (2) after the addition of the 5G ranging signal, due to the uninterrupted characteristics of the 5G ranging signal, the overall positioning continuity of federated filtering was greatly improved; (3) by allocating different scale factors, the experiments show that the federated filtering algorithm can combine sensors with different precision for navigation and positioning, to adapt to the integrated navigation modes in different scenes, and open up a new idea for new sensor integrated navigation.

The future improvement of this paper lies in that this paper only tests the single point positioning mode with new LEO and 5G sensors based on INS/GNSS. In the future, we can study higher-precision positioning algorithms, including but not limited to RTK positioning and PPP positioning. The data used in LEO navigation and positioning in this paper is the satellite position and velocity obtained by simulating the satellite constellation, and there is no measured data source for verification. The simulation of 5G ranging signal only adopts pseudo-range measurement simulation with noise added based on theoretical value. There is no contrast experiment with the way of positioning by specifying positioning protocol in communication standard. The difference of positioning accuracy between the two ways has not been specified yet.

Author Contributions

Y.W. carried out the experiment and contributed to writing the manuscript. K.L. helped to simulate satellite constellations. W.Z. helped to carry out the experiments. B.Z. created the idea. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

In order to avoid reading difficulties caused by too many figures, this article puts the results of velocity error and attitude error in Appendix A.

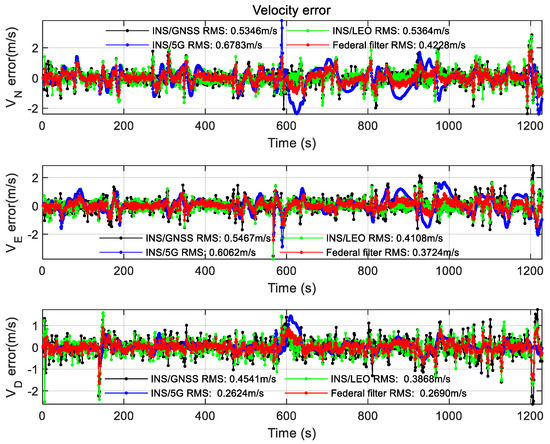

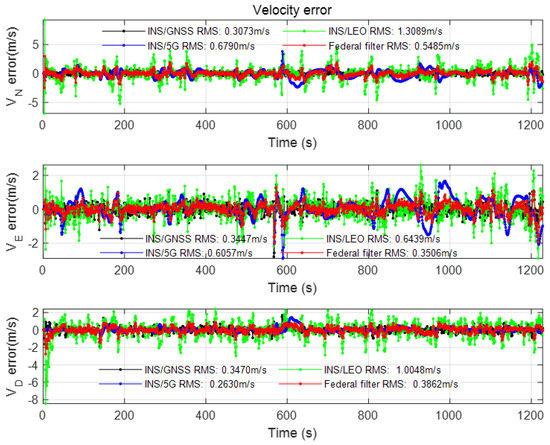

As can be seen from Figure A1 and Figure A2, the velocity error and attitude error of the Open scene is shown. The error values after using the federated filtering algorithm in this article both are relatively stable.

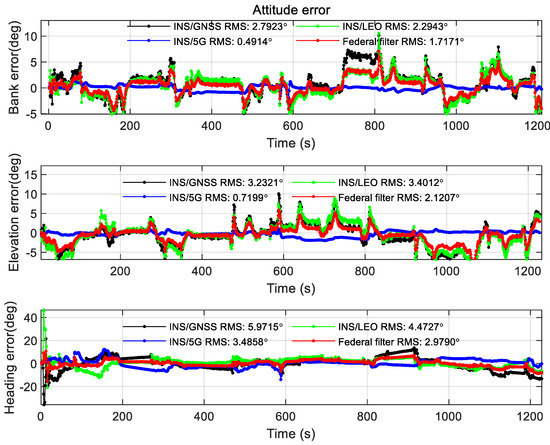

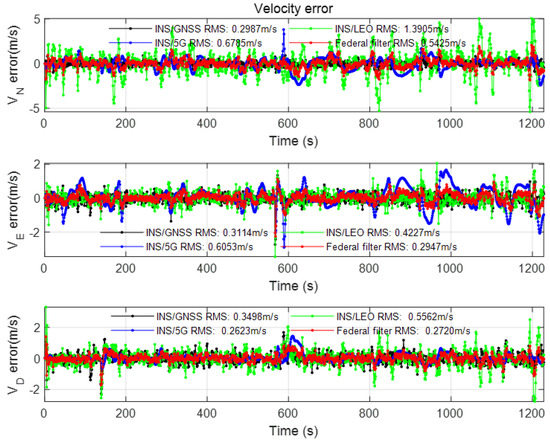

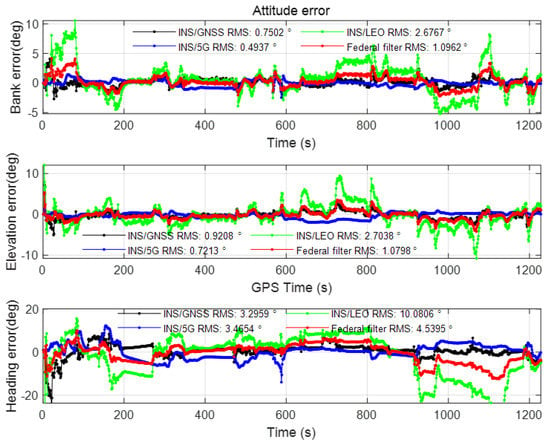

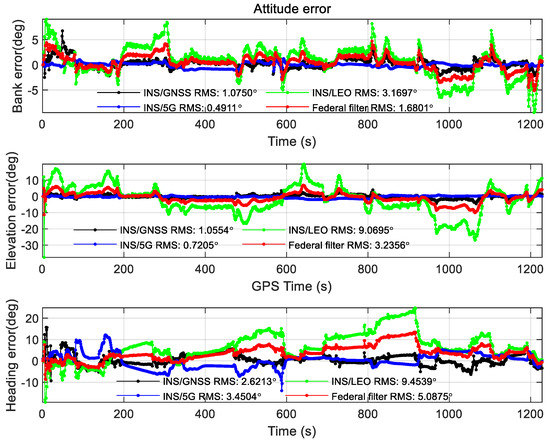

It can be seen from Figure A3 and Figure A4, the fluctuation of velocity error and attitude error of the Semi-occluded is larger than the value in the Open scene, which shows that the influence of simulation scene block on velocity and attitude error begins to play a role.

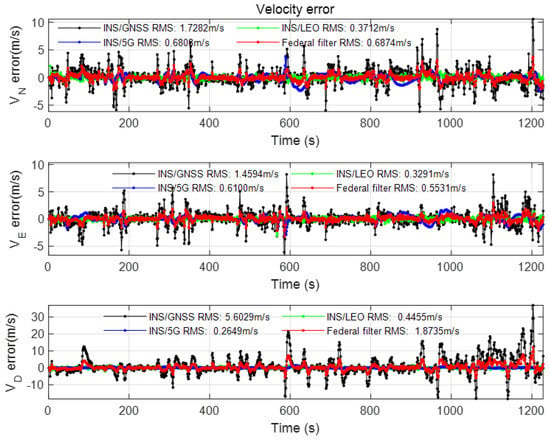

As can be seen from Figure A5 and Figure A6, in the Surrounding occluded scene, LEO constellation is obviously limited, and the error of velocity and attitude is large. However, the error value of the sub-filter will be reduced after using federated filtering.

It can be seen from Figure A7 and Figure A8, with the decrease of visibility of GNSS constellation, the velocity error of INS/GNSS positioning has obvious fluctuation, and the fluctuation of attitude error has exceeded the acceptable range.

It can be seen from Figure A9 and Figure A10, different information factors have different effects on the velocity error and attitude error. The information factor values in different case can be seen from Table 7.

Figure A1.

Velocity error of the Open scene.

Figure A2.

Attitude error of the Open scene.

Figure A3.

Velocity error of the Semi-occluded scene.

Figure A4.

Attitude error of the Semi-occluded scene.

Figure A5.

Velocity error of the Surrounding occluded scene.

Figure A6.

Attitude error of the Surrounding occluded scene.

Figure A7.

Velocity error of the Headspace occluded scene.

Figure A8.

Attitude error of the Headspace occluded scene.

Figure A9.

Federated filtering velocity errors of different information factors.

Figure A10.

Federated filtering attitude errors of different information factors.

References

- Yan, P.; Jiang, J.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Xie, D.; Wu, J.; Liu, J.; Liu, J. Dynamic Adaptive Low Power Adjustment Scheme for Single-Frequency GNSS/MEMS-IMU/Odometer Integrated Navigation in the Complex Urban Environment. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabove, P.; Di Pietra, V. Single-Baseline RTK Positioning Using Dual-Frequency GNSS Receivers Inside Smartphones. Sensors 2019, 19, 4302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Noureldin, A.; Karamat, T.B.; Georgy, J. Fundamentals of Inertial Navigation, Satellite-Based Positioning and Their Integration; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rashed, M.A.; Abosekeen, A.; Ragab, H.; Noureldin, A.; Korenberg, M.J. Leveraging FMCW-Radar for Autonomous Positioning Systems: Methodology and Application in Downtown Toronto. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of The Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS+ 2019), Miami, FL, USA, 16–20 September 2019; pp. 2659–2669. [Google Scholar]

- Groves, P.D. Principles of GNSS, inertial, and multisensor integrated navigation systems, [Book review]. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 2015, 30, 26–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Fan, J.; Zhang, X. “New Infrastructure” in China: Research on Investment Multiplier and Its Effect. Nanjing J. Soc. Sci. 2020, 4, 20–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J. New Infrastructure Construction in China: Both Urgent and Long-Term Support. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2020, 7, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jérôme, L. The Use of GPS/GNSS on Earth and in Space; Montreal Space Symposium: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Montenbruck, O.; Hackel, S.; Jäggi, A. Precise orbit determination of the Sentinel-3A altimetry satellite using ambiguity-fixed GPS carrier phase observations. J. Geod. 2018, 92, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, X.; Zhang, K.; Meng, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Li, X. Precise Orbit Determination for the FY-3C Satellite Using Onboard BDS and GPS Observations from 2013, 2015, and 2017. Engineering 2019, 6, 904–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ma, F.; Li, X.; Lv, H.; Bian, L.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, X. LEO constellation-augmented multi-GNSS for rapid PPP convergence. J. Geod. 2019, 93, 749–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, K.; Ma, F.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, H.; Meng, Y.; Bian, L. Integrated Precise Orbit Determination of Multi-GNSS and Large LEO Constellations. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Su, M.; Su, X.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, J.; Bei, D. Augmented Navigation from Low Earth Orbit Satellites. Sensors 2019, 19, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ardito, C.T.; Morales, J.J.; Khalife, J.; Abdallah, A.A.; Kassas, Z.M. Performance Evaluation of Navigation Using LEO Satellite Signals with Periodically Transmitted Satellite Positions. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Technical Meeting of the Institute of Navigation, Reston, VA, USA, 28–31 January 2019; pp. 306–318. [Google Scholar]

- Farhangian, F.; Benzerrouk, H.; Landry, R. Opportunistic In-Flight INS Alignment Using LEO Satellites and a Rotatory IMU Platform. Aerospace 2021, 8, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, J.; Khalife, J.; Kassas, Z.M. Simultaneous Tracking of Orbcomm LEO Satellites and Inertial Navigation System Aiding Using Doppler Measurements. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 89th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2019-Spring), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 28 April–1 May 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhangian, F.; Landry, J.R. Multi-Constellation Software-Defined Receiver for Doppler Positioning with LEO Satellites. Sensors 2020, 20, 5866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLemore, B.; Psiaki, M.L. Navigation Using Doppler Shift from LEO Constellations and INS Data. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of The Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS+ 2020), Online, 22–25 September 2020; pp. 3071–3086. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Gao, K.; Guo, W.; Cui, J.; Guo, C. Role, path, and vision of “5G + BDS/GNSS”. Satell. Navig. 2020, 1, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3GPP. Available online: http://www.3gpp.org (accessed on 14 August 2013).

- Del Peral-Rosado, J.A.; Saloranta, J.; Destino, G.; López-Salcedo, J.A.; Seco-Granados, G. Methodology for Simulating 5G and GNSS High-Accuracy Positioning. Sensors 2018, 18, 3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, B.; Tan, B.; Wang, W.; Lohan, E. A Comparative Study of 3D UE Positioning in 5G New Radio with a Single Station. Sensors 2021, 21, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Zheng, X.; Wang, H.; Fu, X.; Yin, L.; Liu, W. A Novel Time Delay Estimation Algorithm for 5G Vehicle Positioning in Urban Canyon Environments. Sensors 2020, 20, 5190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Koivisto, M.; Talvitie, J.; Rastorgueva-Foi, E.; Levanen, T.; Lohan, E.S.; Valkama, M. Joint Positioning and Tracking via NR Sidelink in 5G-Empowered Industrial IoT: Releasing the Potential of V2X Technology. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2101.06003. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafavi, S.S. Vehicular Positioning Using 5G and Sensor Fusion. Dissertation 2019, 672, 69. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, W.; Zou, D.; Han, T.; Zhang, X.; Shen, P.; Lu, X.; Wang, P.; Yin, T. A New Type of 5G-Oriented Integrated BDS/SON High-Precision Positioning. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuldt, C.; Shoushtari, H.; Hellweg, N.; Sternberg, H. L5IN: Overview of an Indoor Navigation Pilot Project. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, N.A. Federated square root filter for decentralized parallel processors. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 1990, 26, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, N.A.; Berarducci, M.P. Federated Kalman Filter Simulation Results. Navigation 1994, 41, 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Github. Available online: https://github.com/weisongwen/UrbanNavDataset (accessed on 14 September 2021).

- Walker, J.G. Satellite constellations. J. Br. Interplanet. Soc. 1984, 38, 559–571. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, M.; Xu, T.; Gao, F.; Nie, W.; Yang, H. Optimal Walker Constellation Design of LEO-Based Global Navigation and Augmentation System. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).