Abstract

Optical gas sensors play an increasingly important role in many applications. Sensing techniques based on mid-infrared absorption spectroscopy offer excellent stability, selectivity and sensitivity, for numerous possibilities expected for sensors integrated into mobile and wearable devices. Here we review recent progress towards the miniaturization and integration of optical gas sensors, with a focus on low-cost and low-power consumption devices.

1. Introduction

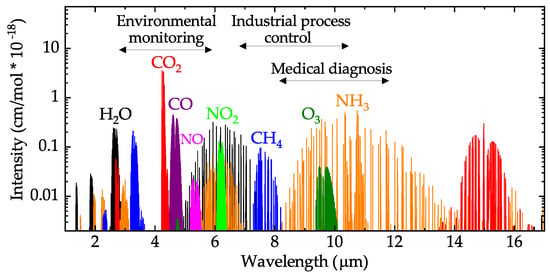

Gas sensors are used in a variety of scientific, industrial and commercial applications [1]. Among various sensing techniques [2], sensors based on the interaction of light with gas molecules [3], can offer high sensitivity [4,5], and long-term operation stability [5]. In addition, they have longer lifetimes and shorter response times [3,6], compared to other techniques [2], making them suitable for real-time [7], and in situ [8] detection. Most optical gas sensors rely on absorption spectroscopy [3], where a gas is detected by measuring the light absorbed (due to its interaction with the gas) as a function of wavelength [9]. Many important organic and inorganic molecules [9] have characteristic absorption lines in the mid-infrared (MIR) spectral region ( 2–20 m) (Figure 1) [10], corresponding to fundamental vibrational and rotational energy transitions [9]. The MIR fundamental transitions have stronger line strengths than their overtones, typically used in the visible and near-IR regions [9,10]. In addition, spectra are less congested, allowing selective spectroscopic detection of many molecules [9,10]. This molecular “fingerprinting” capability makes MIR gas sensors highly desirable for an increasing number of applications involving chemical analysis, such as industrial process control [11,12,13], environmental monitoring [14,15], and medical diagnosis [16].

Figure 1.

Mid-infrared absorption spectra of selected molecules with their relative intensities. HO: water; CO: carbon dioxide; CO: carbon monoxide; NO: nitric oxide; NO; nitrogen dioxide; CH: methane; O: oxygen; NH: ammonia. Source: HITRAN [10].

With the emerging trend in miniaturization of optical devices based on integration on-chip [17], numerous possibilities are expected for optical gas sensors integrated into smartphones, tablets, wearable and medical devices [18]. Applications such as breath analysis [16,19,20], body tissue and fluid analysis [21], food quality control [22,23,24], identification of impurities or counterfeits [25], or measurement of surfaces, detection of contaminants or identification of solids [26,27] are expected to increase rapidly. Such markets can only be addressed with low-cost, highly reliable and sensitive, and highly compact and stable sensors. In addition, ultra-low power consumption is needed, e.g., to operate such sensors in mobile devices [28,29] or wireless networks [30], power levels below 1 mW are required, at suitably low-costs, less than $2 [18,30,31]. These requirements can be met in integrated optical systems [17,32], by combining miniaturized optical components [33] and waveguides [34] into highly condensed devices. Integration technologies based on complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) processes have clear advantages in size, and power [31,35,36], with the possibility of cost reduction leveraging standard high-volume manufacturing for applications such as integration with consumer electronics [31], or sensor networks for the internet of things (IoT) [15,30].

The core of an optical gas sensor is a light source with emission in the range of interest [3]. In addition, dedicated filtering and detection mechanisms are needed [3]. Development of new light sources (e.g., quantum cascade lasers (QCLs) [37,38], light emitting diodes (LEDs) [39,40], and micro-electro-mechanical systems (MEMS)-based thermal emitters [41,42,43]), and detection techniques (e.g., optical [3], and acoustic [44]) have changed the outlook of optical gas sensors over the past two decades. These advancements, in particular the realization of new MIR sources [45], combined with the increasing needs to develop new innovative technologies for healthcare, digital services and other innovation [46], are driving optical gas sensors towards low-cost, mainstream applications [15,19]. Gas sensors based on optical detectors, have been demonstrated for various applications (e.g., breath analysis [19,47], indoor air quality (IAQ) [48], or pollution control [49]). Photoacoustic sensors, using highly-sensitive MEMS microphones, have also emerged as compact, low-cost sensors with high sensitivity and stable operation [44,50,51]. Nevertheless, current optical gas sensing technologies still suffer from drawbacks, e.g., QCLs are expensive complex heterostructures [37,38], LEDs have limited emission for > 5 m [39], and MEMS micro-heaters suffer from poor emissivity [52]. In addition, long (∼cm [3]) optical interaction pathlengths are required to increase the sensor signal response. These limitations motivate research on new materials, novel designs and technologies. Here, we review recent developments towards the miniaturization and integration of optical gas sensors, with a focus on low-cost and low-power consumption devices.

2. Optical Gas Sensor Topologies

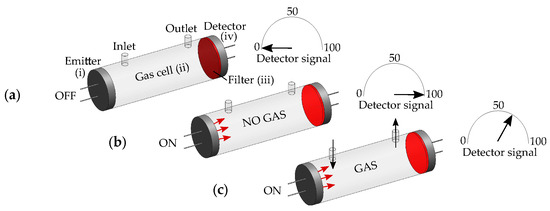

Most optical gas sensors rely on the Beer-Lambert’s law [9], where a gas is detected according to the relation : where and [W/m] are the detected and emitted optical intensities at the wavelength , respectively; [L/gm] is the gas absorption coefficient; c [g/L] is the gas concentration; and l [m] is the light-gas interaction pathlength. A typical sensor (depicted in Figure 2), is comprised of: (i) an emitter to generate , (ii) an optical path, l (gas cell), to guide light to interact with the gas, (iii) an optical filter to select the range of wavelengths () characteristic to the gas target, and (iv) a detector to detect the absorbed light, . A common technique relies on nondispersive sensing, where unfiltered light is used to interact with the gas [3,6]. Nondispersive gas sensors allow selective detection (with ), by filtering the detected light based on the characteristic absorption spectra, , of the molecular species [9]. Sensors configured with IR emitters and detectors, are traditionally known as nondispersive IR (NDIR) sensors [3], although variations for other spectral regions, or for configurations with acoustic instead of optical detectors [3], share the same operating principle based on the Beer–Lambert’s law [9].

Figure 2.

Optical gas sensor based on the Beer–Lambert’s law. (a) No signal detected when the emitter is off. (b) The detected signal is at a maximum when the emitter is on and no gas is present, and is decreasing (c) with the gas concentration, c, when the gas is present.

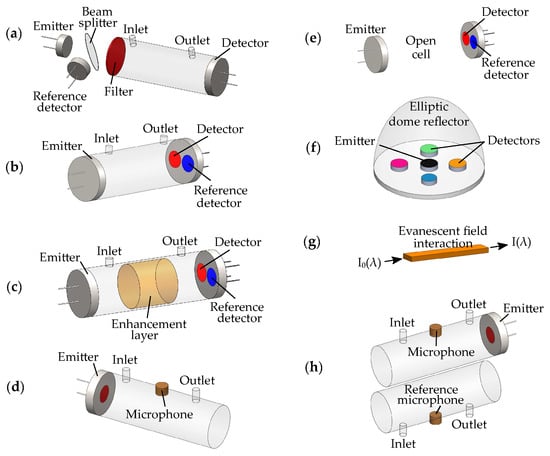

Various topologies have been implemented to fabricate optical gas sensors (Figure 3), with the most commonly used based on gas cells formed between face-to-face configured emitters and optical detectors [48,53,54] (Figure 3a–c,e). Strategies to miniaturize the gas cell include: the use of enhancement layers, such as photonic crystals [55], optical cavities [56], multi-pass cells [57], or gas enrichment layers [58], to increase the light-gas interaction (Figure 3c); planar configurations of emitters and detectors [44,59] (Figure 3f); or use of waveguides for evanescent-field interaction [60,61,62] (Figure 3g). The absorbed light, , is typically detected via an optical detector such as a photodiode [47], thermopile [63], or pyroelectric [64], or an acoustic detector such as a microphone [44]. The sensor response signal, , is typically extracted by means of a lock-in detection technique, from a known frequency used to modulate the emitter [19,65]. A reference detector is often used to compensate for changes in the emitted light [40,48,53,54,58,59,64]. Additional sensors can be used to compensate for environmental parameters such as temperature, pressure or humidity [44,51,59,63,66]. In this section, we review the performance of current topologies with a focus on miniaturized devices, based on both acoustic and optical detection.

Figure 3.

Optical gas sensors topologies. Most commonly used sensors rely on gas cells formed between face-to-face configured emitters and detectors. (a) Light can be filtered prior interaction with the gas. An external reference detector can be used to compensate for changes in the emitted light [53]. (b) Dual detector configuration, with [48,58] or without [54] filters. (c) The gas cell can be reduced by increasing the light-gas interaction, e.g., by using photonic crystals [55], optical cavities [56], multi-pass cells [57], or gas enrichment layers [58]. (d) Photoacoustic cell. Acoustic waves created by light-gas interaction are detected by a microphone. It can be resonant [67] or non-resonant [68]. (e) Open cell configuration, using either dual optical detection [64] or microphones sealed with target gases [69]. (f) Cell with emitter and detector in planar configuration. Multiple optical detectors with filters in the range of interest can be used [59], or microphones sealed with target gases [44]. (g) Waveguide sensors based on evanescent field interaction [60,61,62] require optical coupling with both emitters and detectors. (h) Dual photoacoustic cell with reference microphone [70,71,72].

2.1. Optical Detection

Gas sensors using optical detectors, to measure , have been successfully implemented for a variety of gases: acetone (CHO) [63], ammonia (NH) [63], carbon dioxide (CO) [19,40,43,47,54,58,59,61,64,73], formaldehyde (CHO) [48], nitric oxide (NO) [53], carbon monoxide (CO) [59,64,74], methane (CH) [56,59,60,62,64,75,76], or methanol (CHOH) [77]. Various strategies have been implemented to fabricate gas sensors based on optical detection, Table 1 (Figure 3a–c,e–g). These include designs based on tube-like gas cells formed between face-to-face configured emitters and detectors [19,43,48,53,54,58,63,75,76,77] (Figure 3a–c,e), dome-like gas cells with planar configured emitters and detectors [47,59] (Figure 3f), open cells [40,64,73] (Figure 3e), cavity-enhanced cells [56], or waveguides based on evanescent-field interaction [60,61,62] (Figure 3g). Different light sources have been used such as MEMS heaters [19,43,54,63,64,73,77], LEDs [40,47,48,53,76], distributed feedback lasers (DFBs) [62,75], or QCLs [61], and detectors such as photodiodes [47,48,53,62,76], thermopiles [19,43,54,63], pyroelectric detectors [59,64,77], or photoconductive detectors [56,60,61]. Thus far the most popular configuration is based on face-to-face configured tube-like cells for CO detection [19,56,60]. The performance of gas sensors based on optical detection has steadily improved. Table 1 summarizes representative output performances. For example, sensitivities down to tens ppm [19,47,56,63,73] with power consumption possibly below 10 mW [47,73] or even less are now possible in compact low-cost formats [19,47]. Although at the expense of a Helium–Neon (HeNe) laser, ref. [56] presents a remarkably ∼25 m small MEMS optical cavity for CH detection. Note that sensors based on waveguides [60,61,62,78], require external light sources and detectors and suffer from relatively low sensitivities compared to other topologies.

Table 1.

Gas sensors based on optical detection. : operating wavelength; l: optical path; MEMS: micro-electro-mechanical systems; FF: face-to-face; //: unreported; LED: light emitting diode; DFB: distributed feedback laser; QCL: quantum cascade laser; MCT: mercury cadmium telluride; WG: waveguide; CHO: acetone; NH: ammonia; CO: carbon dioxide; CHO: formaldehyde; NO: nitric oxide; CO: carbon monoxide; CH: methane; CHO: methyl formate; CHOH: methanol.

2.2. Acoustic Detection

Photoacoustic (PA) gas sensors are also based on the Beer–Lambert’s law [9], where the gas sample is excited by a light source, however, unlike sensors based on optical detection, the response signal (proportional to a pressure wave created by the light-gas interaction), is captured by means of acoustic detection [3,79]. Because of their simplicity, and highly reliable performance, PA gas sensors are widely used. They have been implemented for a variety of gases, including: CO [15,51,68,69,80,81], CH [44,68,69,70,71,81], acetylene (CH) [68,82], ethane (CH) [68], CO [68,83], ethylene (CH) [68], CHO [67] sulfur dioxide (SO) [67], NO [84], hexane (CH) [7], oxygen (O) [72], water (HO) [81], and nitrogen dioxide (NO) [66]. Sensitive methods down to few ppb trace gas detection have been reported [7,66]. Various designs have been proposed, based on both resonant (R) (i.e., by tuning the emitter modulation frequency to an acoustic resonance of the cell, thus amplifying the sound signal) [7,66,67,70,71,72,81], and non-resonant (NR) cells [15,44,50,51,69,80,82,84], with light sources including LEDs [15,44,50,67,72], MEMS heaters [51,69,80], QCLs [84], interband cascade lasers (ICLs) [7,71], or DFBs [81,83]. Various strategies have been used to implement the acoustic detector, Table 2. These include designs based on gas-filled [15,44,50,51,69,80,85], or unfilled MEMS microphones [66,67,71,72], optical microphones based on Fabry–Pérot interferometers (FPIs) [68,82], or quartz tuning forks (QTFs) [83,84]. Table 2 summarizes representative operation performances. For example, sensors based on FPIs [68,82] or QTFs [84] feature higher sensitivities. However, these also require more expensive light sources [84], and have larger form factors [68,82,84]. Reference [68] presents a sensor based on a thermal emitter able to detect 6 different gases (CH, CH, CH, CH, CO and CO) in the ∼3 to 10 m range, with remarkably small (sub-ppm) detection limits.

Table 2.

Gas sensors based on acoustic detection. F-MEMS: gas filled-MEMS; FPI: Fabry–Pérot interferometer; ICLED: interband cascade light emitting device; QTF: quartz tuning fork; ICL: interband cascade laser; NR: non-resonant; R: resonant; //: unreported; CO: carbon dioxide; CH: methane; CH: acetylene; CH: ethane; CO: carbon monoxide; CH: ethylene; CHO: acetone; SO: sulfur dioxide; NO: nitric oxide; CH: hexane; O: oxygen; HO: water; NO: nitrogen dioxide.

3. Path to Miniaturization and Integration

Optical gas sensors provide excellent stability, selectivity, and sensitivity [3,6], being among the most reliable methods for measuring CO levels in exhale human breath [16,19,20], and therefore are well suited for next generation medical and consumer electronics end-use applications. However, integration technologies that are efficient, are low-cost and can enable low-power consumption, remain the central challenges of applied modern MIR technologies [45,86]. Although significant effort is being dedicated towards the miniaturization of MIR devices [15,47], progress towards chip-scale, low-cost formats, most needed in a variety of applications, is still in its infancy [17,32]. In this section, we review current progress towards the miniaturization and integration of optical gas sensors, and discuss current major challenges.

3.1. MIR Emitters

The high-cost and limited tuning range as well as high-power consumption of current MIR sources [45] (the core of an optical gas sensor), make the use of optical gas sensors with low-cost, battery-operated systems an ongoing problem, and even more so with wireless systems [15,30]. For example, despite the success of QCLs in the MIR [37,38], their high-cost (∼$1000) and high-power consumption have limited their application to consumer electronics. MIR LEDs can offer lower power consumption with overall high efficiencies [39,40], however, their operation above ∼5 m is challenging [45] and comes at significantly increased costs (∼$100). Nevertheless, renewed scientific interest in the miniaturization of low-cost optical gas sensors [43,54,63], is being fueled by advances in silicon micromachining [36,87]. Recently, membrane microhotplates based on MEMS technology [88,89,90] (Figure 4), came up as compact, integrated thermal light sources [42,43,91]. MEMS heaters are proven to be energy efficient [90], allow for rapid modulation owing to their low thermal mass [19,90], and are compatible with standard CMOS foundry processes [19,90]. They are typically used with CMOS compatible thermal detectors (e.g., thermopiles [19,43,54,63,92], bolometers [73], or pyroelectric detectors [59,64,77]), as they allow broadband MIR detection at room temperature [93] with minimum manufacturing costs [36]. However, standard CMOS materials exhibit inherently low MIR emissivity/absorptivity, especially for wavelengths <8 m, which makes additional post-CMOS/MEMS blackening layers and filter elements necessary [36], often needed to fulfil applications such as spectroscopy.

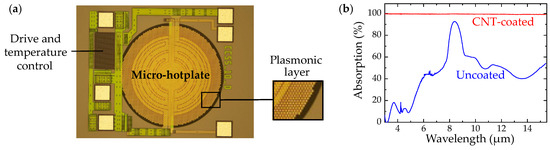

Figure 4.

(a) Complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) integrated plasmonic microhotplate with drive and temperature control. (b) Mid-infrared spectra of carbon nanotubes (CNT)-coated and uncoated devices [94].

We have developed various CMOS microhotplates based on tungsten metallization, as well as several thermal engineering techniques to enhance and tailor their MIR proprieties, Figure 4. Tungsten is an interconnect metal found in high temperature CMOS processes, and can enable stable MIR emitters [90] with excellent device reproducibility and the possibility of a wide range of on-chip circuitry, at very low cost [36]. We have engineered highly efficient plasmonic metal structures to enhance the microhotplate MIR emission via excitation of surface plasmon resonances [43], which can be broadly tuned by varying the structure unit cell geometry. CMOS integrated MIR emitters, with drive and temperature control, can feature membrane diameters as small as 600 m, and have ∼50 mW DC power consumption (∼1 mW optical output power), when operated at 550 C, with good emission for > 8 m (Figure 4a). We have also showed that the radiation properties of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) can significantly enhance both emissivity [95] and absorptivity [94] of MIR devices, due to their blackbody-like behaviour (nearly unity) (Figure 4b).

3.2. Spectroscopy

One of the most important area of research in MIR technologies is to develop compact and affordable spectroscopic devices [17,45]. This would give immediate access to a broad range of applications while at the same time supporting developments in new areas [18]. Currently, on-line, real-time spectroscopic gas sensors, are used for the detection of single analytes at trace levels, or two to three species at most at the same time [59,63,64,77]. Main limitations include the high-cost and limited tuning ranges of MIR sources [45]. Proposed solutions for miniaturization of MIR spectrometers include linear variable optical filters [96], interferometer arrays [97], Fabry–Pérot interferometers (FPIs) [77,98], or MEMS Fourier transform IR (FTIR)-based spectrometers [99]. However, these require high-power lasers [96,97], have limited tuning ranges [77,96,97,99], or moving parts [77,99] and have relatively high costs [77]. Nondispersive gas sensors relax the requirements on the MIR light sources and detectors [3,19,73], hence exploiting standard CMOS processes is an attractive route towards the fabrication of low-cost integrated thermal emitters and detectors [36]. For this reason, membrane MEMS devices emerged as MIR light sources [36,89,90,91] and detectors [92,100,101], with various thermal engineering techniques, e.g., based on: photonic crystals [55], multi-quantum well structures [102], resonant-cavities [103], carbon nanoparticle adlayers [94,95], and plasmonic metamaterials [42,43]. Among these, the overall broadband emission enhancement (almost unity) offered by carbon-based nanomaterial adlayers [94,95], are of particular interest for spectroscopy. Plasmonic/metamaterial concepts [42,43] can be successfully applied to nondispersive sensors [54], based on both MEMS thermal emitters [43,63] and detectors [54], to enable wavelength tailored single- and multi-band [104], as well as polarization- and angle-independent [105] operation. In absence of these optical engineering approaches, CMOS MIR thermal devices have shown poor/non-optimal spectral performance exclusively defined by the used material proprieties [92,94,95].

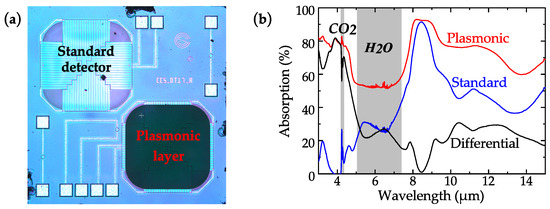

We have developed a filter-free technique for the detection of CO based on CMOS plasmonic emitters and detectors [54] (Figure 5), that could be applied for spectroscopic detection across the entire MIR spectrum. The detector signal is computed differentially between the plasmonic and non-plasmonic cells as shown in Figure 5b. Note that except for the plasmonic layer, the two integrated detector cells are identical. The differential signal has a peak around 4.26 m in the CO detection range and low absorptivity at other wavelengths. More recently, arrays of wavelength-dependent detectors, based on similar plasmonic/metamaterial thermal engineering concepts have been proposed [106,107,108], to enable spectroscopic detection across various bands in the MIR.

Figure 5.

(a) Differential filter-free detection, and (b) spectral response. Adapted from ref. [54].

3.3. Acoustic vs. Optic Detection

Compared to traditional nondispersive gas sensors, PA gas sensors present several advantages. They do not require optical detectors and are wavelength independent. The absorbed light, , is measured directly (i.e., not relative to a background), meaning PA is highly accurate, with very little instability [3,79]. Other advantages include smaller (sub-cm [51,69,80]) optical pathlengths, l, and more robust setups [3,44]. Among these, non-resonant PA gas sensors are more stable, feature lower modulating frequencies and require smaller volumes and pathlengths, hence are less susceptible to noise [15,44,50,51,69,80,82,84]. Resonant PA sensors can, however, offer higher sensitivities, but their stability is affected by environmental parameters, such as temperature and pressure [7,66,67,70,71,72,81]. Despite these benefits, only recently efforts towards non-resonant PA gas sensor miniaturization have been reported, e.g., based on thermal emitters [51,69,80], and LEDs [15,44,50] in combination with microphones, or LEDs and QTFs [109]. Among these, sensors based on highly-sensitive MEMS microphones (employed to detect pressure pulses modulated at audio frequencies) are easy to integrate [110], and offer sensitivities down to ∼tens ppm [15,67,80], with overall small power consumption [50], and form factor [44,50]. PA is unique since it is a direct monitor of a sample nonradiative relaxation channels and, hence, complements absorption spectroscopic techniques [9]. Although PA spectra can be recorded by measuring the sound at different wavelengths of light [79], it requires tunable or multiple MIR sources centred at specific wavelengths, which are not available at low-cost and/or low-power consumption [45]. On the other hand, spectroscopic detection techniques based on arrays of plasmonic detectors [54,106,107,108] can be achieved at very low cost and minimum power consumption.

3.4. Electronics and Signal Processing

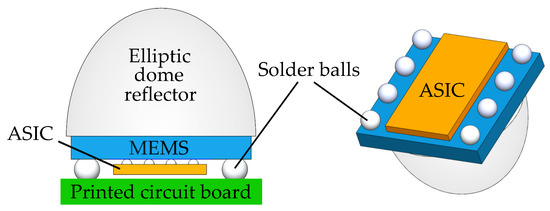

Optical gas sensors require signal amplification and processing techniques to increase their signal-to-noise ratio. A common technique relies on lock-in amplification [19,65], where the sensor response signal is recovered from noise by extracting it at a specific reference frequency, typically used to modulate the emitter (e.g., light pulses). Bench-top lock-in amplifiers are widely used in optical gas sensor setups [60,61,66,68,70,71,81,82,84], however, they are not suitable for use with portable sensing devices, and even less so with integrated circuits (ICs). Miniaturized, IC-based lock-in amplifiers can be used to implement optical gas sensors, with relatively good performance [19]. Other techniques include the use of digital signal processors (DSPs) based on microcontrollers (MCUs) [43,75,80] or field programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) [7]. MCU-implemented digital lock-in amplifiers [43,75,80], or fast Fourier transform (FFT)-based techniques [44,69], are increasingly used. An integrated optical gas sensor concept is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Integrated optical gas sensor concept. Planar integration of emitters and detectors within the same micro-electro-mechanical systems (MEMS) chip, facing an optimized multi-reflection elliptic mirror (gas cell). The sensor signal can be enhanced with an on-chip amplifier and have the first analogue processing level done on-chip with more complex signal processing done externally through the use of an application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC). The MEMS and ASIC chips are attached via face-to-face flip-chip bonding.

4. Outlook

Optical gas sensors based on MIR absorption spectroscopy offer excellent stability, selectivity, and sensitivity for a growing number of potential applications. Experimental setups that combine low-cost and low-power consumption emitters and detectors, are attractive prospects for battery-operated mobile devices and networks. CMOS-based technologies increase device fabrication flexibility, in addition to having economic advantages. Among various configurations, sensors based on dome-like gas cells [44,47,50,59], allow for planar integration of emitters and detectors, and could be used to further reduce their size. The main challenge is the relatively small pathlengths, l, which can be addressed by further device optimization, e.g., based on multi-pass designs [57,74,111], or use of photonic crystals [55,112] or optical cavities [56] for enhanced absorption. More recently, photoacoustic gas sensors, based on low-cost commercially available MEMS microphones have emerged as simple, compact, and highly reliable devices [15,50].

Most current MIR light sources are expensive and suffer from high-power consumption [45]. MEMS microhotplates have clear advantages in terms of costs, and could potentially (given their full CMOS compatibility) enable sensors with costs below $1. In addition, they have been demonstrated at various wavelengths in the MIR [43,54], with power-consumption possibly below 1 mW. In principle, optical gas sensors based on plasmonic microhotplates could operate across the entire MIR range with relatively high performance [68]. The integration of nanostructures and nanomaterials in MEMS silicon technology could, in principle, produce novel broadband MIR tunable sources. The recent demonstration of a filter-free gas sensor shows the possibility of using this approach for a broad spectral range [54]. These integration technologies could be applied to various gas sensor designs, based on both optical and acoustic detection.

Author Contributions

The authors contributed equally.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Potyrailo, R.A. Multivariable Sensors for Ubiquitous Monitoring of Gases in the Era of Internet of Things and Industrial Internet. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 11877–11923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Cheng, S.; Liu, H.; Hu, S.; Zhang, D.; Ning, H. A Survey on Gas Sensing Technology. Sensors 2012, 12, 9635–9665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson, J.; Tatam, R.P. Optical gas sensing: A review. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2013, 24, 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, I.; Bartalini, S.; Borri, S.; Cancio, P.; Mazzotti, D.; De Natale, P.; Giusfredi, G. Molecular Gas Sensing Below Parts Per Trillion: Radiocarbon-Dioxide Optical Detection. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 270802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomberg, T.; Vainio, M.; Hieta, T.; Halonen, L. Sub-parts-per-trillion level sensitivity in trace gas detection by cantilever-enhanced photo-acoustic spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinh, T.V.; Choi, I.Y.; Son, Y.S.; Kim, J.C. A review on non-dispersive infrared gas sensors: Improvement of sensor detection limit and interference correction. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 231, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, J.C.; Balslev-Harder, D.; Pelevic, N.; Brusch, A.; Persijn, S.; Lassen, M. Flow immune photoacoustic sensor for real-time and fast sampling of trace gases. In Proceedings of the Photonic Instrumentation Engineering V, San Francisco, CA, USA, 27 January–1 February 2018; Volume 10539, p. 105390G. [Google Scholar]

- Dooly, G.; Clifford, J.; Leen, G.; Lewis, E. Mid-infrared point sensor for in situ monitoring of CO2 emissions from large-scale engines. Appl. Opt. 2012, 51, 7636–7642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernath, P.F. Spectra of Atoms and Molecules, 3rd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016; p. 465. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, I.; Rothman, L.; Hill, C.; Kochanov, R.; Tan, Y.; Bernath, P.; Birk, M.; Boudon, V.; Campargue, A.; Chance, K.; et al. The HITRAN2016 molecular spectroscopic database. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2017, 203, 3–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, T. Photoacoustic spectroscopy for process analysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006, 384, 1071–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldenstein, C.S.; Spearrin, R.M.; Jeffries, J.B.; Hanson, R.K. Infrared laser-absorption sensing for combustion gases. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2017, 60, 132–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willer, U.; Saraji, M.; Khorsandi, A.; Geiser, P.; Schade, W. Near- and mid-infrared laser monitoring of industrial processes, environment and security applications. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2006, 44, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schieweck, A.; Uhde, E.; Salthammer, T.; Salthammer, L.C.; Morawska, L.; Mazaheri, M.; Kumar, P. Smart homes and the control of indoor air quality. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 94, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz Perez, A.; Bierer, B.; Scholz, L.; Wöllenstein, J.; Palzer, S. A Wireless Gas Sensor Network to Monitor Indoor Environmental Quality in Schools. Sensors 2018, 18, 4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metsälä, M. Optical techniques for breath analysis: From single to multi-species detection. J. Breath Res. 2018, 12, 027104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieger, M.; Mizaikoff, B. Toward On-Chip Mid-Infrared Sensors. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 5562–5573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogue, R. Recent developments in MEMS sensors: A review of applications, markets and technologies. Sens. Rev. 2013, 33, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, T.A.; Gardner, J.W. A low cost MEMS based NDIR system for the monitoring of carbon dioxide in breath analysis at ppm levels. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 236, 954–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, B.; Khodabakhsh, A.; Metsälä, M.; Ventrillard, I.; Schmidt, F.M.; Romanini, D.; Ritchie, G.A.D.; te Lintel Hekkert, S.; Briot, R.; Risby, T.; et al. Laser spectroscopy for breath analysis: Towards clinical implementation. Appl. Phys. B 2018, 124, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takamura, A.; Watanabe, K.; Akutsu, T.; Ozawa, T. Soft and Robust Identification of Body Fluid Using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy and Chemometric Strategies for Forensic Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 8459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loutfi, A.; Coradeschi, S.; Mani, G.K.; Shankar, P.; Rayappan, J.B.B. Electronic noses for food quality: A review. J. Food Eng. 2015, 144, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clara, D.; Pezzei, C.K.; Schönbichler, S.A.; Popp, M.; Krolitzek, J.; Bonn, G.K.; Huck, C.W. Comparison of near-infrared diffuse reflectance (NIR) and attenuated-total-reflectance mid-infrared (ATR-IR) spectroscopic determination of the antioxidant capacity of Sambuci flos with classic wet chemical methods (assays). Anal. Methods 2016, 8, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.H.; Tapp, H.S. Mid-infrared spectroscopy for food analysis: Recent new applications and relevant developments in sample presentation methods. Trends Anal. Chem. 1999, 18, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, G.; Ogwu, J.; Tanna, S. Quantitative screening of the pharmaceutical ingredient for the rapid identification of substandard and falsified medicines using reflectance infrared spectroscopy. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutengs, C.; Ludwig, B.; Jung, A.; Eisele, A.; Vohland, M. Comparison of Portable and Bench-Top Spectrometers for Mid-Infrared Diffuse Reflectance Measurements of Soils. Sensors 2018, 18, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soriano-Disla, J.M.; Janik, L.J.; Viscarra Rossel, R.A.; Macdonald, L.M.; McLaughlin, M.J. The Performance of Visible, Near-, and Mid-Infrared Reflectance Spectroscopy for Prediction of Soil Physical, Chemical, and Biological Properties. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2014, 49, 139–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.; Heiser, G. An Analysis of Power Consumption in a Smartphone. In Proceedings of the 2010 USENIX Conference on USENIX Annual Technical Conference, USENIXATC’10, Boston, MA, USA, 23–25 June 2010; USENIX Association: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2010; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Y.; You, C.; Zhang, J.; Huang, K.; Letaief, K.B. A Survey on Mobile Edge Computing: The Communication Perspective. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2017, 19, 2322–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palattella, M.R.; Dohler, M.; Grieco, A.; Rizzo, G.; Torsner, J.; Engel, T.; Ladid, L. Internet of Things in the 5G Era: Enablers, Architecture, and Business Models. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2016, 34, 510–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, J.W.; Guha, P.K.; Udrea, F.; Covington, J.A. CMOS Interfacing for Integrated Gas Sensors: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2010, 10, 1833–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kita, D.M.; Lin, H.; Agarwal, A.; Richardson, K.; Luzinov, I.; Gu, T.; Hu, J. On-Chip Infrared Spectroscopic Sensing: Redefining the Benefits of Scaling. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2017, 23, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Lin, P.T.; Patel, N.; Lin, H.; Li, L.; Zou, Y.; Deng, F.; Ni, C.; Hu, J.; Giammarco, J.; et al. Mid-infrared materials and devices on a Si platform for optical sensing. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2014, 15, 014603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, G.; Persichetti, G.; Bernini, R. Hollow-Core-Integrated Optical Waveguides for Mid-IR Sensors. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2018, 24, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltes, H.; Brand, O. CMOS-based microsensors and packaging. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2001, 92, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udrea, F.; Luca, A.D. CMOS technology platform for ubiquitous microsensors. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Semiconductor Conference (CAS), Sinaia, Romania, 11–14 October 2017; pp. 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitiello, M.S.; Scalari, G.; Williams, B.; Natale, P.D. Quantum cascade lasers: 20 years of challenges. Opt. Express 2015, 23, 5167–5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razeghi, M.; Lu, Q.Y.; Bandyopadhyay, N.; Zhou, W.; Heydari, D.; Bai, Y.; Slivken, S. Quantum cascade lasers: From tool to product. Opt. Express 2015, 23, 8462–8475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, H.; Ueno, K.; Morohara, O.; Camargo, E.; Geka, H.; Shibata, Y.; Kuze, N. AlInSb Mid-Infrared LEDs of High Luminous Efficiency for Gas Sensors. Phys. Status Solidi (a) 2018, 215, 1700449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, E.G.; Goda, Y.; Morohara, O.; Fujita, H.; Geka, H.; Ueno, K.; Shibata, Y.; Kuze, N. NDIR gas sensing using high performance AlInSb mid-infrared LEDs as light source. In Proceedings of the SPIE, Infrared Sensors, Devices, and Applications VII, San Diego, CA, USA, 6–10 August 2017; Volume 10404, p. 104040R. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, A.D.; Ali, S.Z.; Udrea, F. On the reproducibility of CMOS plasmonic mid-IR thermal emitters. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Semiconductor Conference (CAS), Sinaia, Romania, 11–14 October 2017; pp. 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochbaum, A.; Fedoryshyn, Y.; Dorodnyy, A.; Koch, U.; Hafner, C.; Leuthold, J. On-Chip Narrowband Thermal Emitter for Mid-IR Optical Gas Sensing. ACS Photonics 2017, 4, 1371–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusch, A.; De Luca, A.; Oh, S.S.; Wuestner, S.; Roschuk, T.; Chen, Y.; Boual, S.; Ali, Z.; Phillips, C.C.; Hong, M.; et al. A highly efficient CMOS nanoplasmonic crystal enhanced slow-wave thermal emitter improves infrared gas-sensing devices. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittstock, V.; Scholz, L.; Bierer, B.; Perez, A.O.; Wöllenstein, J.; Palzer, S. Design of a LED-based sensor for monitoring the lower explosion limit of methane. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 247, 930–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.; Bank, S.; Lee, M.L.; Wasserman, D. Next-generation mid-infrared sources. J. Opt. 2017, 19, 123001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schork, N.J. Personalized medicine: Time for one-person trials. Nature 2015, 520, 609–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, L.; Gibson, D.; Song, S.; Li, C.; Reid, S. Reducing N2O induced cross-talk in a NDIR CO2 gas sensor for breath analysis using multilayer thin film optical interference coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2018, 336, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, J.J.; Hodgkinson, J.; Saffell, J.R.; Tatam, R.P. Non-Dispersive Ultra-Violet Spectroscopic Detection of Formaldehyde Gas for Indoor Environments. IEEE Sens. J. 2018, 18, 2218–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanchenko, S.; Baranov, A.; Savkin, A.; Sleptsov, V. LED-based NDIR natural gas analyzer. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 108, 012036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, L.; Perez, A.O.; Bierer, B.; Eaksen, P.; Wöllenstein, J.; Palzer, S. Miniature Low-Cost Carbon Dioxide Sensor for Mobile Devices. IEEE Sens. J. 2017, 17, 2889–2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, J.; Weber, C.; Eberhardt, A.; Wöllenstein, J. Photoacoustic CO2-Sensor for Automotive Applications. Procedia Eng. 2016, 168, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tyler, T.; Starr, T.; Starr, A.F.; Jokerst, N.M.; Padilla, W.J. Taming the Blackbody with Infrared Metamaterials as Selective Thermal Emitters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011, 107, 045901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehnke, F.; Guttmann, M.; Enslin, J.; Kuhn, C.; Reich, C.; Jordan, J.; Kapanke, S.; Knauer, A.; Lapeyrade, M.; Zeimer, U.; et al. Gas Sensing of Nitrogen Oxide Utilizing Spectrally Pure Deep UV LEDs. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2017, 23, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, A.D.; Ali, S.Z.; Hopper, R.; Boual, S.; Gardner, J.W.; Udrea, F. Filterless non-dispersive infra-red gas detection: A proof of concept. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 30th International Conference on Micro Electro MechanicalSystems (MEMS), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 22–26 January 2017; pp. 1220–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraeh, C.; Martinez-Hurtado, J.L.; Popescu, A.; Hedler, H.; Finley, J.J. Slow light enhanced gas sensing in photonic crystals. Opt. Mater. 2018, 76, 106–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayerden, N.P.; de Graaf, G.; Enoksson, P.; Wolffenbuttel, R.F. A highly miniaturized NDIR methane sensor. In Proceedings of the SPIE, Micro-Optics, Brussels, Belgium, 3–7 April 2016; Volume 9888, p. 98880D. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhang, B.; Liu, S.; Jin, F.; Guo, M.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Q. Highly sensitive photoacoustic gas sensor based on multiple reflections on the cell wall. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2019, 290, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moumen, S.; Raible, I.; Krauß, A.; Wöllenstein, J. Infrared investigation of CO2 sorption by amine based materials for the development of a NDIR CO2 sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 236, 1083–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Tang, L.; Yang, M.; Xue, C.; Zhang, W.; Liu, J.; Xiong, J. Three-gas detection system with IR optical sensor based on NDIR technology. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2015, 74, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; Han, Z.; Kita, D.; Becla, P.; Lin, H.; Deckoff-Jones, S.; Richardson, K.; Kimerling, L.C.; Hu, J.; Agarwal, A. Monolithic on-chip mid-IR methane gas sensor with waveguide-integrated detector. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2019, 114, 051103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranacher, C.; Consani, C.; Tortschanoff, A.; Jannesari, R.; Bergmeister, M.; Grille, T.; Jakoby, B. Mid-infrared absorption gas sensing using a silicon strip waveguide. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2018, 277, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombez, L.; Zhang, E.J.; Orcutt, J.S.; Kamlapurkar, S.; Green, W.M.J. Methane absorption spectroscopy on a silicon photonic chip. Optica 2017, 4, 1322–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Urasinska-Wojcik, B.; Gardner, J.W. Plasmonic enhanced CMOS non-dispersive infrared gas sensor for acetone and ammonia detection. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Instrumentation and Measurement Technology Conference (I2MTC), Houston, TX, USA, 14–17 May 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Zheng, C.; Miao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Du, Q.; Wang, Y.; Tittel, F.K. Development and Measurements of a Mid-Infrared Multi-Gas Sensor System for CO, CO2 and CH4 Detection. Sensors 2017, 17, 2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklorz, A.; Janßen, S.; Lang, W. Detection limit improvement for NDIR ethylene gas detectors using passive approaches. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2012, 175, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rück, T.; Bierl, R.; Matysik, F.M. Low-cost photoacoustic NO2 trace gas monitoring at the pptV-level. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2017, 263, 501–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Safoury, M.; Weber, C.; Schmitt, K.; Pernau, H.; Willing, B.; Woellenstein, J. Photoacoustic gas detector for the monitoring of sulfur dioxide content in ship emissions. In Proceedings of the 19th ITG/GMA-Symposium Sensors and Measuring Systems, Nuremberg, Germany, 26–27 June 2018; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Z.; Chen, K.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Yu, Q. Photoacoustic spectroscopy based multi-gas detection using high-sensitivity fiber-optic low-frequency acoustic sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018, 260, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobelspies, S.; Bierer, B.; Ortiz Perez, A.; Wöllenstein, J.; Kneer, J.; Palzer, S. Low-cost gas sensing system for the reliable and precise measurement of methane, carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfide in natural gas and biomethane. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2016, 236, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Lou, M.; Dong, L.; Wu, H.; Ye, W.; Yin, X.; Kim, C.S.; Kim, M.; Bewley, W.W.; Merritt, C.D.; et al. Compact photoacoustic module for methane detection incorporating interband cascade light emitting device. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 16761–16770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rouxel, J.; Coutard, J.G.; Gidon, S.; Lartigue, O.; Nicoletti, S.; Parvitte, B.; Vallon, R.; Zéninari, V.; Glière, A. Development of a Miniaturized Differential Photoacoustic Gas Sensor. Procedia Eng. 2015, 120, 396–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avramescu, V.; Gologanu, M. Oxygen sensor based on photo acoustic effect. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Semiconductor Conference (CAS), Sinaia, Romania, 11–14 October 2017; pp. 97–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barritault, P.; Brun, M.; Lartigue, O.; Willemin, J.; Ouvrier-Buffet, J.L.; Pocas, S.; Nicoletti, S. Low power CO2 NDIR sensing using a micro-bolometer detector and a micro-hotplate IR-source. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2013, 182, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, R.; Schmidt, F.M. ICL-based TDLAS sensor for real-time breath gas analysis of carbon monoxide isotopes. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 12743–12752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.T.; Huang, J.Q.; Ye, W.L.; Lv, M.; Dang, J.M.; Cao, T.S.; Chen, C.; Wang, Y.D. Demonstration of a portable near-infrared CH4 detection sensor based on tunable diode laser absorption spectroscopy. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2013, 61, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massie, C.; Stewart, G.; McGregor, G.; Gilchrist, J.R. Design of a portable optical sensor for methane gas detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2006, 113, 830–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genner, A.; Gasser, C.; Moser, H.; Ofner, J.; Schreiber, J.; Lendl, B. On-line monitoring of methanol and methyl formate in the exhaust gas of an industrial formaldehyde production plant by a mid-IR gas sensor based on tunable Fabry-Pérot filter technology. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017, 409, 753–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Lin, P.; Singh, V.; Kimerling, L.; Hu, J.; Richardson, K.; Agarwal, A.; Tan, D.T.H. On-chip mid-infrared gas detection using chalcogenide glass waveguide. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 108, 141106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozóki, Z.; Pogány, A.; Szabó, G. Photoacoustic Instruments for Practical Applications: Present, Potentials, and Future Challenges. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2011, 46, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambs, A.; Huber, J.; Wöllenstein, J. Compact Photoacoustic Gas Measuring System for Carbon Dioxide Indoor Monitoring Applications. In Proceedings of the AMA Conferences, Nuremberg, Germany, 19–21 May 2015; pp. 918–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Mei, J.; Zhang, W.; Chen, W.; Gao, X. Multi-resonator photoacoustic spectroscopy. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2017, 251, 632–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Slaman, M.; Iannuzzi, D. Demonstration of a highly sensitive photoacoustic spectrometer based on a miniaturized all-optical detecting sensor. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 17541–17548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Ma, Y.; Tong, Y.; Yu, X.; Tittel, F.K. A portable gas sensor for sensitive CO detection based on quartz-enhanced photoacoustic spectroscopy. Opt. Laser Technol. 2019, 115, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtas, J.; Gluszek, A.; Hudzikowski, A.; Tittel, F. Mid-Infrared Trace Gas Sensor Technology Based on Intracavity Quartz-Enhanced Photoacoustic Spectroscopy. Sensors 2017, 17, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholz, L.; Palzer, S. Photoacoustic-based detector for infrared laser spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 109, 041102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soref, R. Mid-infrared photonics in silicon and germanium. Nat. Photonics 2010, 4, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lammel, G. The future of MEMS sensors in our connected world. In Proceedings of the 2015 28th IEEE International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS), Estoril, Portugal, 18–22 January 2015; pp. 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udrea, F.; Gardner, J.W.; Setiadi, D.; Covington, J.A.; Dogaru, T.; Lu, C.C.; Milne, W.I. Design and simulations of SOI CMOS micro-hotplate gas sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2001, 78, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barritault, P.; Brun, M.; Gidon, S.; Nicoletti, S. Mid-IR source based on a free-standing microhotplate for autonomous CO2 sensing in indoor applications. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2011, 172, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.Z.; De Luca, A.; Hopper, R.; Boual, S.; Gardner, J.; Udrea, F. A Low-Power, Low-Cost Infra-Red Emitter in CMOS Technology. IEEE Sens. J. 2015, 15, 6775–6782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pühringer, G.; Jakoby, B. Efficient Vertical-Cavity Mid-IR Thermal Radiation to Silicon-Slab Waveguide Coupling Using a Shallow Blazed Grating. Proceedings 2017, 1, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, R.; Ali, S.; Chowdhury, M.; Boual, S.; De Luca, A.; Gardner, J.W.; Udrea, F. A CMOS-MEMS Thermopile with an Integrated Temperature Sensing Diode for Mid-IR Thermometry. Procedia Eng. 2014, 87, 1127–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillner, U.; Kessler, E.; Meyer, H.G. Figures of merit of thermoelectric and bolometric thermal radiation sensors. J. Sens. Sens. Syst. 2013, 2, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, A.; Cole, M.T.; Hopper, R.H.; Boual, S.; Warner, J.H.; Robertson, A.R.; Ali, S.Z.; Udrea, F.; Gardner, J.W.; Milne, W.I. Enhanced spectroscopic gas sensors using in-situ grown carbon nanotubes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 106, 194101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luca, A.D.; Cole, M.T.; Fasoli, A.; Ali, S.Z.; Udrea, F.; Milne, W.I. Enhanced infra-red emission from sub-millimeter microelectromechanical systems micro hotplates via inkjet deposited carbon nanoparticles and fullerenes. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 113, 214907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayerden, N.P.; Wolffenbuttel, R.F. The Miniaturization of an Optical Absorption Spectrometer for Smart Sensing of Natural Gas. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 9666–9674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podmore, H.; Scott, A.; Cheben, P.; Velasco, A.V.; Schmid, J.H.; Vachon, M.; Lee, R. Demonstration of a compressive-sensing Fourier-transform on-chip spectrometer. Opt. Lett. 2017, 42, 1440–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stark, T.; Imboden, M.; Kaya, S.; Mertiri, A.; Chang, J.; Erramilli, S.; Bishop, D. MEMS Tunable Mid-Infrared Plasmonic Spectrometer. ACS Photonics 2016, 3, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazen, E.; Yasser, M.S.; Mohammad, S.; Bassem, M.; Mostafa, M.; Diaa, K. On-Chip Micro– Electro–Mechanical System Fourier Transform Infrared (MEMS FT-IR) Spectrometer-Based Gas Sensing. Appl. Spectrosc. 2016, 70, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, R.; Ali, S.Z.; Boual, S.; Luca, A.D.; Dai, Y.; Popa, D.; Udrea, F. A CMOS-Based Thermopile Array Fabricated on a Single SiO2 Membrane. Proceedings 2018, 2, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varpula, A.; Timofeev, A.V.; Shchepetov, A.; Grigoras, K.; Hassel, J.; Ahopelto, J.; Ylilammi, M.; Prunnila, M. Thermoelectric thermal detectors based on ultra-thin heavily doped single-crystal silicon membranes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2017, 110, 262101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Zoysa, M.D.; Asano, T.; Noda, S. Realization of dynamic thermal emission control. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 928–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sollradl, T.; Ranacher, C.; Consani, C.; Puhringer, G.; Lodha, S.; Jakoby, B.; Grille, T. Characterisation of a resonant-cavity enhanced thermal emitter for the mid-infrared. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE SENSORS, Glasgow, UK, 29 October–1 November 2017; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Adato, R.; Altug, H. Dual-Band Perfect Absorber for Multispectral Plasmon-Enhanced Infrared Spectroscopy. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 7998–8006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Mesch, M.; Weiss, T.; Hentschel, M.; Giessen, H. Infrared Perfect Absorber and Its Application As Plasmonic Sensor. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 2342–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.; Li, J.; Yang, A.; Liu, H.; Yi, F. Narrowband plasmonic metamaterial absorber integrated pyroelectric detectors towards infrared gas sensing. In Proceedings of the SPIE, Smart Photonic and Optoelectronic Integrated Circuits XX, San Francisco, CA, USA, 27 January–1 February 2018; Volume 10536, p. 105361H. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, M.; Shahmarvandi, E.K.; Wolffenbuttel, R.F. CMOS-compatible mid-IR metamaterial absorbers for out-of-band suppression in optical MEMS. Opt. Mater. Express 2018, 8, 1696–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suen, J.Y.; Fan, K.; Montoya, J.; Bingham, C.; Stenger, V.; Sriram, S.; Padilla, W.J. Multifunctional metamaterial pyroelectric infrared detectors. Optica 2017, 4, 276–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhring, M.; Böttger, S.; Willer, U.; Schade, W. LED-Absorption-QEPAS Sensor for Biogas Plants. Sensors 2015, 15, 12092–12102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malcovati, P.; Baschirotto, A. The Evolution of Integrated Interfaces for MEMS Microphones. Micromachines 2018, 9, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fohrmann, L.S.; Sommer, G.; Pitruzzello, G.; Krauss, T.F.; Petrov, A.Y.; Eich, M. 2D integrating cell waveguide platform employing ultra-long optical path lengths. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 14th International Conference on Group IV Photonics (GFP), Berlin, Germany, 23–25 August 2017; pp. 131–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gervais, A.; Jean, P.; Shi, W.; LaRochelle, S. Design of Slow-Light Subwavelength Grating Waveguides for Enhanced On-Chip Methane Sensing by Absorption Spectroscopy. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2019, 25, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).