Abstract

The paper assesses brown seaweed diversity following the catastrophic events of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil spill in offshore deep bank habitats at 45–90 m depth in the northwestern Gulf of Mexico, and their potential regeneration and recovery in the region. Innovative approaches to expeditionary and exploratory research resulted in the discovery, identification, and classification of brown seaweed diversity associated with rhodoliths (free-living carbonate nodules predominantly accreted by crustose coralline algae). Whereas the rhodoliths collected in situ at our research sites pre-DWH were teeming with brown algae growing on their surface, post-DWH they looked dead, bare, and bleached. These post-DWH impacts appear long-lasting, with little macroalgal growth recovery in the field. However, these apparent “dead” rhodoliths collected post-DWH at banks offshore Louisiana showed macroalgal regeneration starting within three weeks when placed in microcosms in the laboratory, with 19 brown algal species emerging from the bare rhodoliths’ surface. Some taxa corresponded to new records for the GMx (genus Cutleria and Dictyota cymatophila). Padina vickersiae is resurrected from synonymy with P. gymnospora. Reproductive sori evidence is presented for Lobophora declerckii. A detailed nomenclatural list, morphological plates, and phylogenetic/barcoding trees of brown seaweed that emerged from rhodoliths’ surfaces in laboratory microcosms are provided. These findings provide key molecular and morphological insights that reinforce species boundaries and highlight the significance of mesophotic rhodolith beds as previously overlooked reservoirs of cryptic brown algal diversity.

Keywords:

DNA barcodes; brown seaweeds; Gulf of Mexico; macroalgae; marine diversity; mesophotic; microcosms; rhodoliths; taxonomy 1. Introduction

Rhodoliths are free-living marine benthic algal nodules of various sizes that are predominantly accreted by crustose (non-geniculate) coralline red algae precipitating CaCO3 [1,2,3,4]. They are the main hard substrata for the attachment of benthic phototrophs in the mesophotic (low-light) northwestern Gulf of Mexico (NWGMx) deep bank rubble (rhodolith bed) habitats on the continental shelf at 45–90 (120) m depth [5,6,7,8,9]. These hard banks are associated with salt domes in the vicinity of areas of intensive oil and gas exploration [10,11,12]. The hard banks surmount salt dome (diapir) slopes where strata trap hydrocarbons, and the salt domes are almost 100% pure salt with tiny amounts of CaSO4. If underground water dissolves the salt away, the remaining CaSO4 forms a somewhat insoluble barrier that is then acted upon by anaerobic SO4-reducing bacteria converting CaSO4 to CaCO3. These bacteria obtain the C necessary to reduce CaSO4 to limestone from petroleum hydrocarbons accumulating in pockets along salt dome banks edge [5]. It is the banks’ caprock slopes and peaks that are covered by calcifying rhodolith beds [10,13]. Many rhodoliths in these mesophotic habitats are also covered by fleshy and other crust-forming red, green, and brown seaweeds [4,13,14].

There are two major categories of rhodoliths: (1) biogenic rhodoliths that are formed by the non-geniculate coralline red algae themselves [15,16,17,18], and (2) autogenic rhodoliths that are derived from calcium carbonate rubble established by differential erosion processes of diapir salt [14,15,16,17,18,19], with the calcified rubble becoming secondarily covered by a suite of encrusting algae. These autogenic rhodoliths with a non-coralline algal core become secondarily settled by red, green, and brown macroalgae, and are a specific type of nucleated rhodoliths (sensu [20]) in which the core derives from calcium carbonate rubble as opposed to other materials.

Following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill (DWH) on 20 April 2010, which released approximately 200 million gallons of crude oil in proximity to the studied salt dome-associated banks, the ecological relevance of rhodolith beds for sustaining mesophotic algal biodiversity in the northwestern Gulf of Mexico became particularly evident. Marked post-DWH reductions in macroalgal biomass on rhodoliths provided the impetus for a comprehensive examination of their floristic composition, potential resilience, and ecological roles. Prior to the Macondo well failure (28°44′12.01″ N, 88°23′13.78″ W) and the resulting DWH [19,21,22], rhodoliths were richly covered by macroalgal growth at various hard bank habitats, such as Ewing Bank, a bank that was intensely explored by the UL laboratory since 1997 [13,14,19]. Ewing Bank, one of the northwestern Gulf of Mexico’s most diversity-rich sites that harbored lush assemblages of fleshy seaweeds pre-DWH, e.g., [23,24,25,26], looked like a “graveyard” when we first revisited the site in December 2010 [14,15,16,17,18,19], and during each of our subsequent post-DWH sampling cruises.

The present study reports on different post-DWH oil spill sampling expeditions to Ewing Bank that each lasted 4–5 days and indicated that seaweed/decapod crustacean/molluscan diversity was either significantly depressed or all together absent relative to pre-spill sampling at the same site [14,15,16,17,18,19]. These post-DWH impacts appear long-lasting, with little macroalgal growth recovery in the field as of September 2019, the most recent expedition date. The full extent, reasons, and ecological consequences of the disappearance of healthy rhodoliths and associated macroalgae on the deep banks post-DWH, and the potential link of this decline to consumers is currently unknown.

Bare, denuded, and apparently “dead” rhodoliths collected post-DWH at Ewing Bank and Sackett Bank offshore Louisiana have shown macroalgal regeneration starting within three weeks when placed in 75 L holding tanks (microcosms) in the Seaweeds Laboratory at UL Lafayette. Submerging these bare rhodoliths in situ-collected seawater and augmented with sterilized seawater, triggered the germination of red (Rhodophyta), green (Chlorophyta), and brown (Phaeophyceae) algal germlings from the surface of autogenic rhodoliths, with many growing to adult size and reproducing in the microcosm tanks [14,25]. This study reports on barcoding the brown algal species that grew from the surface of the initially bare autogenic rhodolith samples, specifically from Ewing and Sackett Banks offshore Louisiana, and also from the vicinity of the Dry Tortugas in the southeastern Gulf of Mexico (SEGMx) when placed in laboratory microcosms post-DWH. In addition, some samples of brown algae associated with rhodoliths collected pre-DWH from Campeche Banks (SWGMx) and Florida Middle Grounds (NEGMx) were analyzed to extend the species delimitation and distribution range of taxa in the Gulf of Mexico.

The focus of this paper is the brown seaweeds. A monographic treatment of the brown algae of the eastern Gulf of Mexico was produced by Earle [27] on the basis of comparative morphology. The present study, besides providing new morphological identification and nomenclature data, also focuses on the first molecular exploration of brown macroalgae associated with rhodoliths that emerged post-DWH in laboratory microcosms. The taxonomy of these emergent brown seaweed taxa in laboratory microcosms was critically assessed on the basis of newly produced rbcL, cox3, and UPA sequences from taxa from the Gulf of Mexico and worldwide, and from sequences from GenBank, to facilitate their identification.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Sample Collection

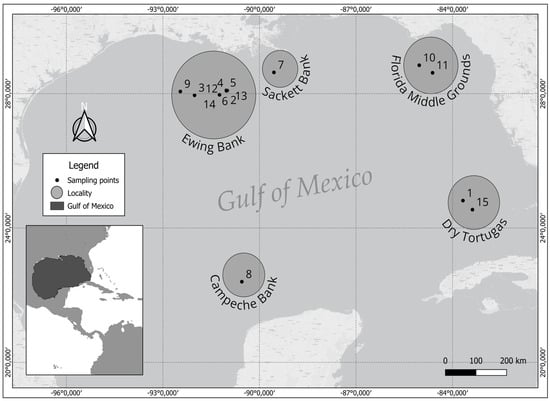

Rhodoliths and associated brown algae were collected in different expeditions between 2000 and 2014 in the northwestern Gulf of Mexico (NWGMx), principally in the vicinity of Ewing Bank, offshore Louisiana, located within the area impacted by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Other expeditions were also carried out in Sackett Bank (NWGMx), the vicinity of the Florida Middle Grounds (NEGMx), the Dry Tortugas (SEGMx), and the Campeche Banks (SWGMx) (Figure 1). Around these five localities, fifteen sampling points were assessed: four pre-DHW (8, 9, 10, 11) and eleven post-DWH (1–7, 12–15). In this study, the only location visited both pre-DWH (9) and post-DWH (2–6, 12–14) was Ewing Bank (see Figure 1; Supplementary Material Table S1). Ewing Bank and Sackett Bank (NWGMx) were sites greatly affected by the DWH. All field trips were conducted aboard the R/V Pelican, equipped with an hourglass-design box dredge [28], sampled on rubble substrata using minimum tow periods (10 min or less) at depths ranging from 55 to 90 m.

Figure 1.

Study area in the Gulf of Mexico. Numbers 1−15 represent the sampling points across different dates and 5 localities (or rhodolith banks). Localities: Ewing Bank, Sackett Bank, Campeche Banks, Florida Middle Grounds and Dry Tortugas. Sampling sites: Pre−DHW (8, 9, 10, 11) and post-DWH (1−7, 12−15). (see Supplementary Material Table S1).

2.2. Microcosm Establishment

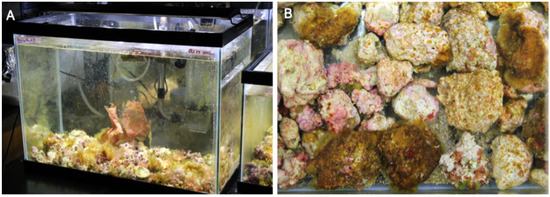

Bare, denuded rhodoliths and those partly encrusted with crustose corallines (and a few representatives of the brown seaweeds Lobophora delicata and Cutleria sp., see Figure 2B) collected after the April 2010 DWH oil spill at Ewing Bank and Sackett Bank, and in the vicinity of the Dry Tortugas, were first separately stored at the collection site in 20 L plastic containers filled with seawater obtained at the same depth and location as the rhodoliths, using the onboard CTD water sampling rosette. Samples were kept aerated under controlled conditions onboard the research vessel for the duration of the 4–5-day survey. Once on land, rhodoliths were transferred to 75 L closed microcosm glass tanks, separated by site and filled with in situ-collected seawater and maintained at the Seaweed Laboratory at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette (Figure 2). Microcosms from the vicinity of the Dry Tortugas area were established from mixed pieces of rubble and rhodoliths. Collected seawater was sterilized with an ultraviolet filter (Aquanetics Systems, San Diego, California). Microcosm systems were kept at approximately 10 h light/14 h dark cycle at 24 °C, the same temperature measured in the field at 55 m depth in late summer (for microcosms establishment and maintenance) [14,17].

Figure 2.

Microcosms of 75 L closed glass tanks separated by site and maintained at the Seaweed Laboratory at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. (A) Tank from Ewing Bank after two months of establishment (rhodoliths collected on 19 October 2013). (B) Rhodoliths placed inside the microcosm from Ewing Bank at the beginning of the study, 22 October 2013).

2.3. Morphological Examination

Brown macroalgae that subsequently emerged from the surface of rhodoliths collected at Ewing Bank, Sackett Bank, and the vicinity of Dry Tortugas microcosms, as well as taxa visible during previous pre-DWH collection of rhodoliths in the GMx (Supplementary Material Table S1), were preserved in silica gel and as dried herbarium specimens, and in 5% formalin/seawater for subsequent molecular morphological analysis, respectively. Brown macroalgae emerging from the surface of the rhodoliths in laboratory microcosms were monitored and bi-weekly photographed (with a Canon EOS Rebel T2i, Canon Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Brown algae were morphologically identified using pertinent literature, e.g., [27,29,30,31,32,33,34]. To rehydrate dried tissues from herbarium specimens, fragments were placed in a vegetable glycerin/water solution (70/30) for 24 h. Cross sections through vegetative structures were obtained manually using a stainless-steel razor blade.

2.4. DNA Processing and Barcoding Analyses

DNA was extracted using a DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The molecular markers selected for this study were the plastid genes rbcL and UPA (23S), and mitochondrial cox3, because of their use in barcoding and phylogenetic studies in brown algae, and their feasibility for amplification and sequencing [32,33,34,35,36,37]. RbcL fragments were amplified with the primers F15-R916 [34] for the first part of the gene and F543-R1393 [35] for the second part. Cox3 was amplified using primers and sequencing conditions according to [36], and UPA according to [38]. Resulting sequences were blasted in the online NIH BLAST library (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi, Access Date: 15 October 2025) to identify the closest taxa sorted by percent identity. Alignments were performed in Mega 12.0.11. The model of evolution GTR + I + G was applied for rbcL and cox3, and GTR + G for UPA as indicated by Partitionfinder [39]. Maximum Likelihood (ML) analyses were conducted using the fast-scaling algorithm with 10,000 bootstrap pseudoreplicates (BPs) in IQ-TREE [40].

3. Results

Brown Algal Barcoding and Diversity in the Gulf of México

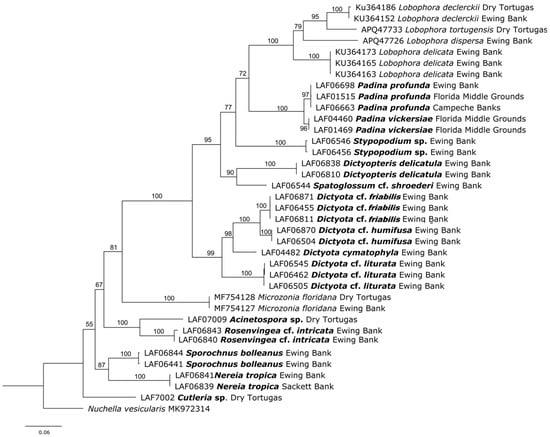

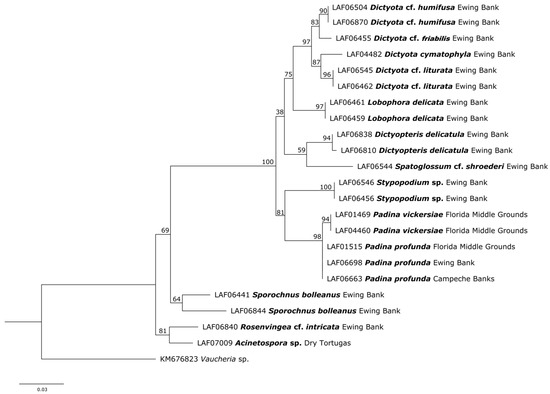

The newly generated sequences of rbcL (27), cox3 (10), and UPA (23), along with the morphological analyses, enabled an accurate assessment of brown algal diversity in the GMx. A total of 19 taxa were identified. The most conspicuous family of brown algae that emerged from the upper surface of rhodoliths in laboratory microcosms was the Dictyotaceae (Dictyotales), encompassing four genera: Lobophora with four species, Dictyota with four species, Stypopodium with one species, and Dictyopteris with one species. Other genera appearing from the rhodoliths surfaces belong to three families in the Ectocarpales sensu lato, i.e., Acinetosporaceae: Acinetospora sp.; Sporochnaceae: Sporochnus and Nereia with one species each; and Scytosiphonaceae: Rosenvingea. In addition, the family Syringodermataceae (Syringodermatales) was represented by Microzonia floridana [41]. Additional studied taxa from the Gulf of Mexico that were not found growing on the surface of rhodoliths placed in laboratory microcosms were as follows: Cutleria sp. (family Cutleriaceae) and Padina profunda, P. vickersiae, and Spatoglossum shroederi (family Dictyotaceae) (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Some of the brown algal entities emerging from the surface of the rhodoliths represented new taxa (i.e., three Lobophora species [42] and Stypopodium sp.); others corresponded to new records for the GMx (genus Cutleria and Dictyota cymatophila), and Padina vickersiae is here proposed to be resurrected from synonymy with P. gymnospora.

Figure 3.

Maximum Likelihood tree based on rbcL barcode analysis of brown taxa from the Gulf of Mexico. Newly sequenced taxa are presented in bold, followed by their locality in the Gulf of Mexico.

Figure 4.

Maximum Likelihood tree based on UPA barcode analysis of brown taxa from the Gulf of Mexico. Newly sequenced taxa are presented in bold, followed by their locality in the Gulf of Mexico.

The brown algal diversity growing from deepwater rhodoliths collected in the Gulf of Mexico include the following:

- I. ORDER DICTYOTALES Bory

- Fam. Dictyotaceae J.V.Lamouroux 1809: 332, pl. 6, Figure 2B [43]

- Dictyopteris J.V.Lamouroux 1809 [43]

- Dictyopteris delicatula J.V.Lamouroux 1809: 332 [43]

- Homotypic synonyms: Neurocarpus delicatulus (J.V.Lamouroux) Kuntze 1891 [44]

- Haliseris delicatula (J.V.Lamouroux) C.Agardh 1820 [45]

- Heterotypic synonyms: Neurocarpus hauckianus (Möbius) Kuntze 1891 [44]

- Polyzonia divaricata P.Crouan & H.Crouan in Schramm & Mazé 1865 [46]

- Dictyopteris hauckiana Möbius 1889 [47]

- Haliseris hauckiana (Möbius) De Toni & Okamura 1895 [48]

Type locality: Antilles, West Indies.

Gulf of Mexico specimens examined: Supplementary Material Table S1, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5A and Figure 6D.

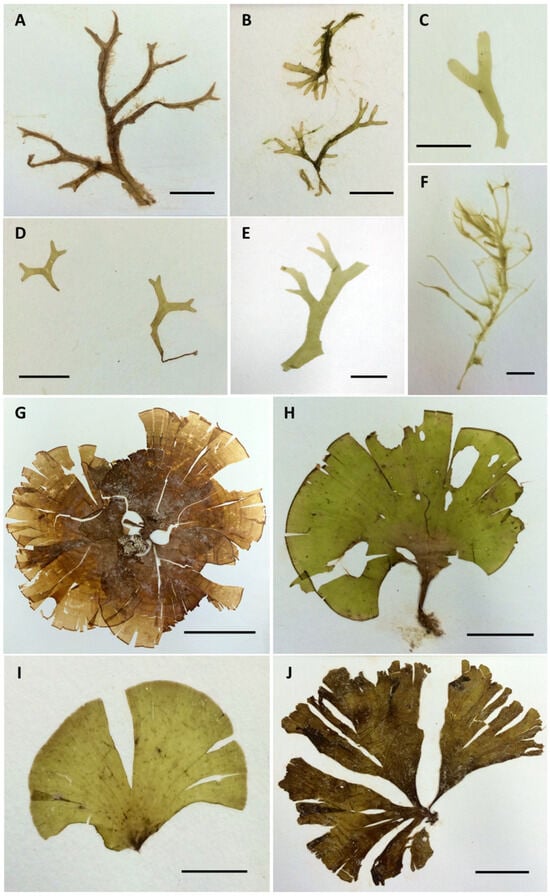

Figure 5.

Herbarium specimens. (A) Dictyopteris delicatula (LAF06810), old specimen, scale bar = 1 cm. (B) Dictyota cf. humifusa (LAF6870), scale bar = 1 cm. (C) Dictyota cf. friabilis (LAF06455), scale bar = 1 cm. (D) Dictyota cymatophila (LAF04482), scale bar = 1 cm. (E) Dictyota cf. liturata (LAF06506), scale bar = 1 cm. (F) Nereia tropica (LAF06841), scale bar = 5 mm. (G) Padina vickersiae (LAF04460), scale bar = 6 cm. (H) Padina profunda (LAF06698), scale bar = 2 cm. (I) Stypopodium sp. (LAF06456, young specimen), scale bar = 1 cm. (J) Stypopodium sp. (LAF06699, mature specimen), scale bar = 1 cm.

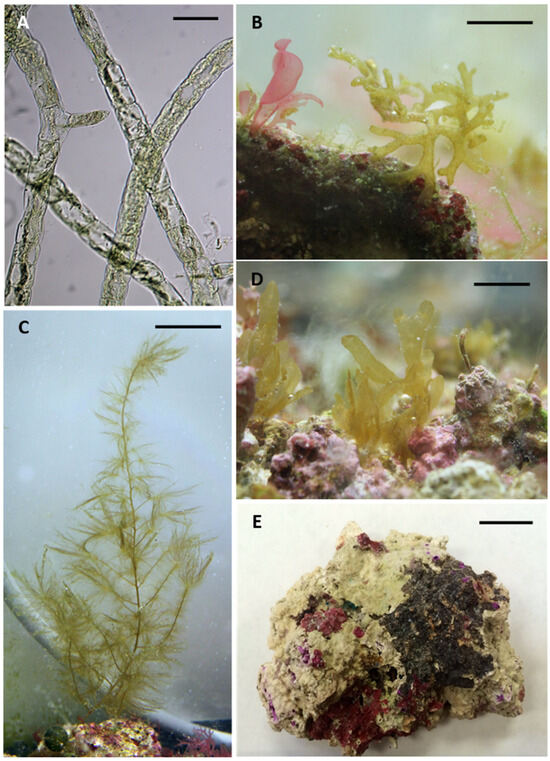

Figure 6.

Habit of species emerging in laboratory microcosms. (A) Acinetospora sp. (LAF0 7009), scale bar= 60 µm. (B) Rosenvingea cf. intricata (LAF06843), scale bar = 1 cm. (C) Sporochnus bolleanus (LAF06844), scale bar = 4 cm. (D) Dictyopteris delicatula (LAF06810), scale bar = 1 cm. (E) Cutleria sp. (Aglaozonia stage) (LAF07002), scale bar = 1 cm.

Habit: Thalli erect or prostrate, to 8 cm tall, light brown, with flat, tangled branches up to 5 mm broad, with a pronounced midrib through the entire thallus, and rounded apices. Branching is dichotomous (young) or alternate to irregular (mature). Hairs are abundant on one side (Figure 5A).

Barcoding analysis: The cox3 sequences’ closest match for a Dictyopteris species (LAF06810, LAF06838) that emerged in separate Ewing Bank microcosms (Supplementary Material Table S1) was 92.50% to a Dictyopteris delicatula/repens complex sp. (MW223427) from São Paulo, Brazil (HV2796, [49]). The rcbL sequences’ closest match of LAF06810 and LAF06838 was 98.99% to Dictyopteris sp. (MW511047) from Madagascar [50], followed by a 98.18% match to D. delicatula (EU579943, [35] from New Caledonia. However, D. delicatula was described from the “Antilles”, West Indies, and its morphological and anatomical description, e.g., [27,29,31,35] fits that of the Ewing Bank specimens. The UPA sequences matched 97.55% to D. polypodioides (KF367772) from North Carolina, USA, and 95.80% to D. divaricata (NC_036804) complete chloroplast genome [51].

Comments: Dictyopteris delicatula is distinguished from D. plagiogramma (Montagne) Vickers by lacking pinnate veinlets [27]. D. delicatula is reported from the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. It is rare in Onslow Bay, North Carolina, on rock outcrops at 34–40 m depth. The species has been reported from a range of unconfirmed worldwide distributions [52].

- Dictyota Lamouroux 1809 [43]

- Dictyota cymatophila Tronholm, M.Sanson & Afonso-Carrillo in Tronholm et al. 2010b: 1080–1083, Figure 6 and Figure 7 [33]

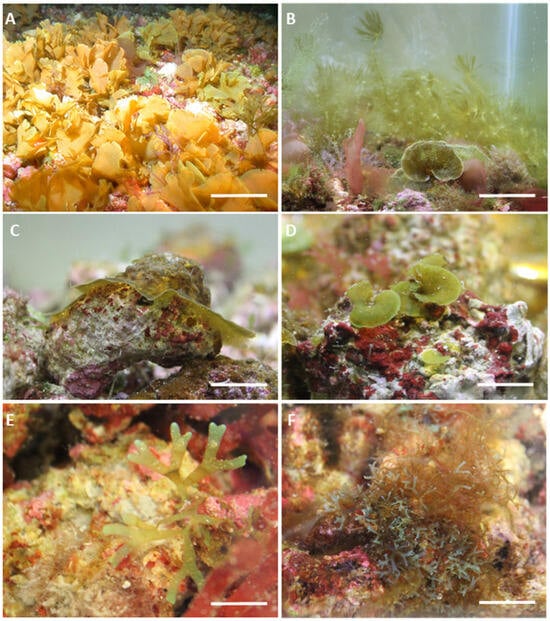

Figure 7. Living brown algal from the Gulf of Mexico. (A) Padina profunda (LAF06698), habit in an Ewing Bank rhodolith bed at 55 m depth (photo courtesy: FGBNMS), scale bar = 10 cm, from microcosm. (B) Lobophora dispersa, Sporochnus bolleanus, and red and green algae growing from the surface of Ewing Bank rhodoliths placed in microcosms post-DWH at UL Lafayette, scale bar = 10 cm. (C) Lobophora delicata (LAF06459) covering a rhodolith with visible rhizoids on its ventral side, scale bar = 1 cm. (D) young Stypopodium sp. (LAF06546), scale bar = 1 cm. (E) Dictyota cf. friabilis (LAF06455), scale bar = 1 cm. (F) Dictyota cf. humifusa (LAF06504), scale bar = 3 cm.

Figure 7. Living brown algal from the Gulf of Mexico. (A) Padina profunda (LAF06698), habit in an Ewing Bank rhodolith bed at 55 m depth (photo courtesy: FGBNMS), scale bar = 10 cm, from microcosm. (B) Lobophora dispersa, Sporochnus bolleanus, and red and green algae growing from the surface of Ewing Bank rhodoliths placed in microcosms post-DWH at UL Lafayette, scale bar = 10 cm. (C) Lobophora delicata (LAF06459) covering a rhodolith with visible rhizoids on its ventral side, scale bar = 1 cm. (D) young Stypopodium sp. (LAF06546), scale bar = 1 cm. (E) Dictyota cf. friabilis (LAF06455), scale bar = 1 cm. (F) Dictyota cf. humifusa (LAF06504), scale bar = 3 cm.

Type locality: Holotype locality: Punta del Hidalgo (28°35′ N, 16°20′ W), northern Tenerife, Canary Islands, Spain (Tronholm et al. 2010b: 1082 in [33]). Holotype (male gametophyte): A. Tronholm; 30 August 2007; exposed lower eulittoral. TFC Phyc 14267, D403 (Tronholm et al. 2010b: 1082 in [33]). Notes: Isotypes: TFC Phyc 14268 to 14271 (sporophytes), 14272 to 14274 (male gametophytes), and 14275 to 14277 (female gametophytes). Isotypes in GENT and L.

Gulf of Mexico specimen examined: Supplementary Material Table S1. Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5D.

Habit: Thalli erect, up to 2 cm tall, growing from multiple basal stolons. Branching wide-angled, dichotomous. Branches are flat, 1–2 mm wide, with smooth margins and acute tips (Figure 5D).

Barcoding analysis: The rbcL sequence LAF04482 clusters (99.55%) with D. cymatophila from the Canary Islands (GQ425111) [33]. The cox3 LAF04482 sequence matched 98.83% to D. cymatophila (MW223456) from the same voucher specimen as in rbcL, D397 [32]. The UPA LAF04482 sequence matched 98.92% to D. sandvicensis (EF426585) [50].

Comments: This is the first report of D. cymatophila for the Gulf of Mexico, and the first report for a region outside Spain and the Canary Islands. While reproductive structures are lacking, the species otherwise fits the description of D. cymatophila.

- Dictyota cf. humifusa Hörnig, Schnetter & Coppejans 1992: 57 [53]

Type locality: Punta Chengue, Santa Marta, Departamento del Magdalena, Colombia; (Hörnig & al. 1992: 57) [52] [Holotype: COL; A-4287 (De Clerck 2003: 17 in [54]).

Gulf of Mexico specimens examined: Supplementary Material Table S1, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5B and Figure 7F.

Habit: Thalli erect, entangled or not, light brown or purple-green iridescent (Figure 7F), up to 10 cm tall, with dichotomous to irregular branching. Blades are strap-shaped, sometimes twisted, slender, 0.3–1.5 mm wide. Internodes are 1.5–4 cm long with pointed to rounded tips (Figure 5B).

Barcoding analysis: The rbcL sequences from LAF06504 and LAF06870 specimens that emerged in microcosm tanks matched 99.04% a sequence named D. humifusa (MW223225) from the Netherlands Antilles [50], and 98.73% to D. humifusa (JQ061126) from Indonesia [55]. The cox3 sequences matched 98.33% to D. humifusa (LN831812) from Madagascar [56]. The UPA sequences matched 97.33% to D. falklandica (BK070409) complete chloroplast genome [57].

Comments: The Indonesian report of D. humifusa most certainly is misidentified, since the species was described from Santa Marta, Colombia [53]. This taxon, along with D. pfaffii, needs special taxonomic review.

- Dictyota cf. friabilis Setchell 1926: 91 [58]

Type locality: Tafaa Point, Tahiti [Society Islands, French Polynesia]; (Silva et al. 1996: 593, [59]). Holotype: UC 261252 (De Clerck 2003: 170 [54]).

Gulf of Mexico specimens: Supplementary Material Table S1, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5C and Figure 7E.

Habit: Thalli in microcosms usually erect, brown-green in color (Figure 7E), up to 5 cm tall. Branches are flat, thin, 1–2.5 mm wide. Branching dichotomous. Margins smooth, and tips acute to rounded (Figure 5C).

Barcoding analysis: The rbcL sequences LAF06455 and LAF06811 emerging from Ewing Bank microcosms matched 99.92% to a sequence named as D. cf. pfaffii (MW223251) from the Canary Islands [50], followed 97.19% to D. humifusa (MW223225) from the Netherlands Antilles [50], and 96.70% match to D. canaliculata (GQ425108) from Indonesia [55]. More distantly, LAF06455 and LAF06811 matched 93.52% to a sequence named Dictyota cf. friabilis voucher ODC1492 from the Philippines [50]. The closest match of the LAF6811 cox3 sequence was 99.84% to D. cf. pfaffii (MW223482) from the Canary Islands [50], followed by 89.98% similarity to D. humifusa (LN831812) from Madagascar [56]. The closest match of the UPA sequences of LAF06455 and LAF06811 (97.44%) was D. falklandica (BK070409) complete chloroplast genome [57], followed by (97.44%) D. sandvicensis (EF426585) [38].

Comments: Dictyota pfaffii is currently regarded as a synonym of D. friabilis, displaying a broad global distribution [52]. This taxon, along with D. humifusa, needs special taxonomic review.

- Dictyota cf. liturata J.Agardh 1848: 95 [60]

- Heterotypic synonym: Dictyota pappeana Kützing 1849 [61]

Type locality: Cape of Good Hope, South Africa [62]. Lectotype: Pappe; LD 49099 (De Clerck 2003: 172, 173, in [54]).

Gulf of Mexico specimen examined: Supplementary Material Table S1, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5E.

Habit: Thalli erect, up to 10 cm tall. Branching is subdichotomous to alternate. Branches flat, up to 5 mm wide, with smooth margins and acute tips (Figure 5E).

Barcoding analysis: The rbcL sequences LAF06462, LAF06505, and LAF06545 representing specimens emerging from Ewing Bank microcosms matched 99.67% with a specimen referred to as D. liturata J. Agardh [61] (GQ425113) from Isla de Margarita, Venezuela [32,33], and in 99.5% to D. liturata from Portugal [50]. However, these sequences also showed 100% molecular identity to D. menstrualis from Brazil [62]. The cox3 sequence LAF06545 closest match (91.54%) was Dictyota sp. (MW223463) from Victoria, Australia [55], followed by (91.44%) Dictyota dichotoma (MK516769) from Victoria, Australia [63]. The UPA sequences of LAF06462 and LAF06545 closest match (98.19%) was Dictyota acutiloba (EF426587) [38], followed by (97.67%) D. sandvicensis (EF426585) [38], both probably from Hawaii.

Comments: This is the first report of this species (D. liturata) for the Gulf of Mexico. However, a taxonomic and nomenclatural review of this clade or group of Dictyota is needed. The species is also reported from Atlantic islands, Madagascar, and South Africa (Indian Ocean) [52].

- Lobophora J. Agardh 1894 [64]

- Lobophora delicata O.Camacho & Fredericq 2019: 618 in [42]

Type locality: USA, NW Gulf of Mexico, Ewing Bank; (Camacho et al. 2019: 618) Holotype: S. Fredericq & O. Camacho; 26.viii.2011; rhodoliths at 60–90 m; LAF06459 [42]).

Gulf of Mexico specimen examined: Supplementary Material Table S1, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 7C. See [42].

Habit: see [42].

Barcoding and phylogenetic analyses: see [42].

- Lobophora declerckii N.E.Schultz, C.W.Schneider & L.LeGall 2015: 493 [65]

Type locality: Tombant de Port-Louis, Guadeloupe, Antilles, Caribbean Sea, western Atlantic Ocean (16°23′44.34″ N, 61°32′4.318″ W); (Schultz et al. 2015: 493 in [65]). Holotype: L. Le Gall/Y. Buske et al. FRA1676; 15 May 2012; 29 m; PC; 0143238 (Schultz et al. 2015: 493 in [65]). Notes: GenBank KR260267, KR260319. Isotypes FRA1677 [PC0143249], FRA1678 [PC0143250].

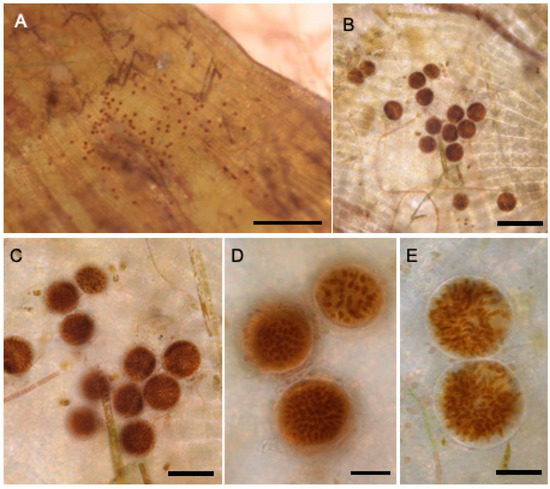

Figure 8.

Reproductive sori in Lobophora declerckii (LAF04483), (A–E) sorus on the surface of the blade. Scale bars: (A) = 1 cm; (B) = 200 µm; (C) = 100 µm; (D,E) = 50 µm.

Habit: Thallus light brown, decumbent. Blades composed of a single cell-layered medulla surrounded by two or three layers of cortical cells on both ventral and dorsal sides. Reproductive sori observed (Figure 8).

Barcoding analysis: The cox3 sequence LAF07103 matched 99.29% to L. declerckii (MN240090) from Curaçao.

Comments: So far, this species has been reported for the tropical western Atlantic [52]. In the Gulf of Mexico, it was found in Ewing Bank and Dry Tortugas from 55 to 80 m. The Ewing Bank specimen LAF0443 growing from rhodoliths in lab microosms, exhibited reproductive sori (Figure 8).

- Lobophora dispersa O.Camacho, Freshwater & Fredericq 2019: 619 in [42].

Type locality: USA, North Carolina, Onslow Bay (Camacho et al. 2019: 619, in [42]); Holotype: D.W. Freshwater & A. Alder; 29.x.2013; on hard bottom, 23 m; WNC33550 (Camacho et al. 2019: 619 in [42]).

Gulf of Mexico specimen examined: Supplementary Material Table S1, Figure 3 and Figure 7B. See [42].

Habit: see [42].

Barcoding and phylogenetic analyses: see [42].

- Lobophora tortugensis O.Camacho & Fredericq 2019: 620 in [42]

Type locality: USA, SE Gulf of Mexico, northwest of Dry Tortugas; (Camacho et al. 2019: 620 in [42]), Holotype: S. Fredericq; 10.ix.2014; on rhodoliths, 65 m; LAF06999 (Camacho et al. 2019: 620 [42]) Notes: Isotype: LAF07102.

Habit: see [42].

Barcoding and phylogenetic analyses: see [42].

- Padina Adanson 1763 [66]

- Padina profunda Earle 1969: 167, Figures 62–68 in [27]

Gulf of Mexico specimens examined: Supplementary Material Table S1, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5H and Figure 7A.

Type locality: Loggerhead Key, Dry Tortugas (Earle 1969) [27].

Habit: Thallus fan-shaped, 8 cm tall and 7 cm wide, blades entire (or split) (Figure 5H), only slightly calcified at the stipe and basal portion of the blade.

Barcoding analysis: The three rbcL sequences representing Padina profunda from the Florida Middle Grounds (LAF01515), Ewing Bank (LAF06698), and Campeche Banks (LAF06663) are conspecific, and sister to the lightly calcified Padina vickersiae from the Florida Middle Grounds (Figure 3 and Figure 4). The rcbL LAF01515 and LAF06698 sequences matched 96.43% to a sequence named P. imbricata (LC487946) from Japan [67]. The UPA sequences LAF01515 and LAF06698 matched 97.33% to P. gymnospora (OR961489) from Portugal (DLG2007040, [34]).

Comments: This species did not emerge in post-DWH microcosms, but field-collected specimens were sequenced for the assessment of their general placement in the Dictyotaceae. Although the habit of P. profunda resembles that of P. glabra [68] described from Dakar, Senegal, P. profunda has some calcification at the base, whereas P. glabra is completely uncalcified. The specimens referred to as P. glabra from Florida [69] and Texas [70] are in all likelihood misidentified. P. profunda is a rare deepwater species occurring in the Dry Tortugas [27], West Florida [31], Campeche Banks [71], and offshore rock outcroppings near the continental shelf edge in Onslow Bay, North Carolina [35,72].

- Padina vickersiae Hoyt in Britton & Millspaugh 1920: 595 [73]

Type locality: Beaufort, North Carolina, USA.

Habit: Fan-shaped thalli, 15 cm tall by 30 cm wide, 4 cell layers throughout, including the margin, and 6–8 cell layers at the base, lightly calcified, with enrolled apical margins and short stalk attached by rhizoidal mat (Figure 5G).

Barcoding analysis: The rbcL sequence LAF01469 and LAF04460 matched 95.89% to P. imbricata (LC487946) from Japan [67]. The UPA sequences matched 97.33% to P. gymnospora (OR961489) from Portugal [34]. In the rbcL tree, Padina vickersiae from the Florida Middle Grounds (LAF04460, LAF01469) is sister to Padina profunda from the Gulf of Mexico (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Comments: This species did not emerge from microcosms but was sequenced to assess its placement among fan-shaped members of the Dictyotaceae. Padina vickersiae was placed in synonymy with Padina gymnospora (Küzing) Sonder 1871 [74], described from St. Thomas, Virgin Islands. However, the specimens from the Gulf match the description of P. vickersiae [29] in having 4 cell layers throughout, including the margin, and 6–8 cell layers at the base, unlike P. gymnospora which has 3 cell layers at the margins and in the middle and 4 cell layers near the stipe. Padina vickersiae is here proposed to be resurrected from synonymy with P. gymnospora.

- Spatoglossum Kützing 1843 [75]

- Spatoglossum cf. schroederi (C. Agardh) Kützing 1859: 2 in [76]

- Basionym: Zonaria schroederi C.Agardh 1824 (‘schröderi’) [77]

- Homotypic Synonyms: Dictyota schroederi (C.Agardh) Greville 1830 [78]

- Taonia schroederi (C.Agardh) J.Agardh 1848 [60]

- Heterotypic Synonym: Spatoglossum areschougii J.Agardh 1894 [64]

Type locality: Brazil [59].

Habit: Minuscule fragment, 0.5–1 cm tall.

Barcoding analysis: The rbcL sequence from the minuscule fragment from the Ewing Bank microcosm (LAF06544) should correspond to Spatoglossum schroederi, the only species reported for the Gulf of Mexico and western Atlantic. It matches 99.75% with S. asperum (EU579964, [35]) from Guadeloupe, French West Indies, which is misidentified and should be referred to as S. schroederi. S. schroederi is sister to true S. asperum (EU579963, [35]) from New Caledonia. The type locality of S. asperum J. Agardh [79] is Ceylon [Sri Lanka]. The UPA LAF06544 sequence closest match (96.48%) was Dictyopteris polypodioides (KF367772) from Onslow Bay, North Carolina.

Comments: Spatoglossum schroederi has been reported from the eastern Gulf of Mexico [27], Campeche Banks [71]), North Carolina, Bermuda, Atlantic Florida, Bahamas, and south to Brazil [52].

- Stypopodium Kützing 1843 [75]

- Stypopodium sp.

Gulf of Mexico specimens examined: Supplementary Material Table S1, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5I,J and Figure 7D.

Habit: Erect, fan-shaped blades, up to 12 cm high, tending to split when old. Concentric rows of hairs are lacking on the thallus surface.

Barcoding analysis: The rcbL sequences indicate that the two specimens that emerged from the Ewing Bank microcosms (LAF06456, LAF06546) matched 95.92% to a Stypopodium sp. sequence (AB096914) from Japan [79], followed by 94.42% to Stypopodium schimperi (PQ099226) from Croatia [80]. The cox3 sequences matched 88.21% to S. schimperi (MW223642) from South Africa [50]. UPA sequences matched 95.35% to Padina gymnospora (OR961489) from Azores, Portugal [34].

Comments: This appears to be an undescribed species of Stypopodium and represents the first report for the Gulf of Mexico. Reproductive material is lacking. The species is distinct from S. zonale in lacking concentric rows of hairs on the thallus surface. Stypopodium zonale (J.V.Lamouroux) Papenfuss [81] is described from the Dominican Republic and is a common shallow water species in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico.

- II. ORDER ECTOCARPALES Bessey

- Fam. Acinetosporaceae G.Hamel ex Feldmann

- Acinetospora sp.

Gulf of Mexico specimens examined: Supplementary Material Table S1, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 6A.

Habit: The species consists of erect, barely branched, uniseriate filaments with irregularly cylindrical cells, 25–38 µm wide, 12.5–38 (75) µm long. Lateral rhizoids are not seen (Figure 6A).

Barcoding analysis: The rcbL sequence of an Ectocarpus-like filament (LAF07009) emerging from Dry Tortugas microcosm nested inside the Acinetosporaceae, a family that includes the genera Acinetospora, Feldmannia, Geminocarpus, Herponema, Hincksia, and Pylaliella. The Dry Tortugas specimen matched 96.49% to rbcL sequences in Acinetospora filamentosa from Japan [82], 96.08% to A. crinita (AF207795) described from Scotland [83], and 94.99% to Feldmannia chitonicola (MN092346) from South Korea [84]. The UPA Dry Tortugas specimen (LAF07009) clustered 97.64% with Pylaiella littoralis (X61179).

Comments: Acinetospora crinita, described from Scotland [85,86] and reported for the Gulf of Mexico [27], should be an erroneous species record for the NWGMx. Microcosm specimen cell sizes are smaller than reported by [27]. The Acinetosporaceae family requires taxonomic attention.

- Fam. Scytosiphonaceae Farlow

- Rosenvingea Børgesen 1914 [87]

- Rosenvingea cf. intricata (J. Agardh) Børgesen 1914: 26 [87]

- Basionym: Asperococcus intricatus J.Agardh

- Heterotypic Synonym: Asperococcus schrammii P.Crouan & H.Crouan

Type locality: Veracruz, Gulf of Mexico, Mexico. Type: Liebmann; LD (presumably) Lipkin & Silva 2002: 4 in [88].

Gulf of Mexico specimens examined: Supplementary Material Table S1, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 6B.

Habit: Erect thalli, light brown, reaching up to 5 cm tall, hollow, with tridimensional-pseudo-dichotomous branching, mostly terete, 1–2 mm wide. Attached by a basal disk (Figure 6B).

Barcoding analysis: The rbcL sequences from specimens (LAF06843, LAF06840) emerging from the Ewing Bank microcosms nested in the Scytosiphonaceae, a family that includes the genera Rosenvingea, Chnoospora, Colpomenia, Hydroclathrus, and Scytosiphon. The rbcL sequences of both specimens matched 95.95% with R. intricata complete genome from Okinawa Pref. Southern Japan (AB022232, [89]) and 95.95% to R. polynesiensis from Tahiti. The specimen labeled R. intricata from New Caledonia (GQ368323, [90]) corresponds to a clade and is misidentified at the species level. The cox3 LAF06843 sequence matched in the sequence KF700319 of R. intricata from GenBank. However, the reference KF799319 listed in GenBank is not included in the cited publication [91]. Although the locality of that taxon is unknown, its cox3 sequence is clearly a different species from a separate, misidentified clade referred to as R. intricata from Central America (unknown, KM587012), Pacific Panama (Isla Canal de Afuera, Veraguas, KM587018), Vietnam (Nha Trang, KM587013, KM587016), and Baja California del Sur, Mexico (La Paz, KM587011). The UPA LAF06840 from the Gulf of Mexico sequence matched 99.4% to Colpomenia sinuosa form Hawaii [38], but this could be an missidentification; no Rosenvignea UPA sequences are available in GenBank.

Comments: This species is reported for the Gulf of Mexico, Okinawa, Japan, and the Caribbean Sea. Reports from other locations are doubtful and likely refer to separate species. A same biogeographic distribution pattern between Ewing Bank in the NWGMx and Okinawa, Japan, was also found in metabarcoding studies of rhodoliths by Sauvage et al. [92]. Rosenvingea Børgesen is a tropical to subtropical genus that includes seven currently accepted species [89,91,93]. Rosenvingea specimens from the microcosm corresponds to the description (and Figure 111) of Rosenvingea intricata from the Gulf of Mexico [27].

- III. ORDER SPOROCHNALES Sauvageau

- Fam. Sporochnaceae R.K.Greville

- Sporochnus C. Agardh 1817 [94]

- Sporochnus bolleanus Montagne 1856: 393 1856 in [95]

Type locality: Isleta de Lobos, Canary Islands (Montagne 1856: 393). Type: Bolle; PC.

Gulf of Mexico specimen examined: Supplementary Material Table S1, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 6C and Figure 7B.

Habit: Thalli dark brown, filiform main axes, coarse, up to 30 cm tall, 0.3–0.5 mm in diameter. Branches are 5–10 cm long, cylindrical, not swollen, with deciduous tufts of filaments that are light brown, 10–15 mm long, and more prominent at the tips (Figure 6C and Figure 7B).

Barcoding analysis: The rbcL LAF06844 and LAF06441 sequences matched 98.2% to Sporochnus bolleanus from South Korea and 97.55% to S. radiciformis from the Canary Islands. This species is distinct from the species referred to as S. bolleanus from Australia (AB776781) which is conspecific with S. moorei Harvey (1858) [96] described from N.S.W., Australia. The UPA sequence LAF06441 matched 99.72% to Sporochnus bolleanus from Spain (NC_085311).

Comments: Specimens conform to the concept of S. bolleanus, e.g., [27,29,31]. The species is present in Campeche Banks [71], offshore Onslow Bay, NC, to 45 m depth, Atlantic Islands [52], and the tropical and subtropical western Atlantic [97]. According to [27], this species is abundant in the northeastern GMx, growing on seagrasses, shells, and limestone at depths of 1–8 m. Taylor [29] reported it growing at 90 m depth in the western Atlantic.

- Nereia Zanardini 1846 [98]

- Nereia tropica (W.R.Taylor) W.R.Taylor 1955: 74, pl. 5 [99]

- Basionym: Stilophora tropica W.R.Taylor 1928 [100]

Type locality: Dry Tortugas, FL, USA.

Gulf of Mexico specimens examined: Supplementary Material Table S1, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5F.

Habit: Main axes up to 20 cm tall. Secondary branches irregularly branched, up to 15 cm long. Pedicels of ultimate branchlets 1(−2) mm long, 0.5 mm diam., with terminal tufts of golden-brown hairs to 4 mm long (Figure 5F).

Barcoding analysis: Nereia tropica growing in the Sackett Bank (LAF06839) and Ewing Bank (LAF06841) microcosms are nested inside the Sporochnaceae, Ectocarpales. The rbcL sequences from the Gulf matched 93.03% to Nereia sp. from Norfolk Island (NSW482874, [101]). The UPA LAF06841 sequence matched 96.05% to Cutteria multifida from France (NC_085298) and 95.79% to Sargassum horneri (MT795188) from Asia. The Sporochnaceae algae need a global molecular effort [102].

Comments: Nereia differs from Sporochnus by its indistinct axis and lateral tufts of sessile filaments [31,101]. Nereia tropica is reported from Dry Tortugas, Bermuda [27]; Campeche Banks [71]; western Florida [31]; and tropical and subtropical western Atlantic [29,97].

- IV. ORDER TILOPTERIDALES C.E. Bessey

- Fam. Cutleriaceae J.W.Griffith & A.Henfrey

- Cutleria Greville 1830 [78]

- Cutleria sp.

Habit: Thallus prostrate to crustose, dark brown, tightly adhering to rhodolith surfaces (Figure 6E).

Barcoding analysis: The rbcL sequence from Dry Tortugas LAF07702 matched 96.95% to Cutleria adspersa (AB545967 [103]) reported from Kagoshima, Japan. The cox3 sequence LAF07702 matched 88.84% to Cutleria adspersa (AB682740, [102]) from Kagoshima, Japan. However, C. adspersa may be misidentified since its type locality is Cadiz, Spain.

Comments: This is the first report of the genus Cutleria in the Gulf of Mexico. The specimen was growing in Dry Tortugas at 65 m depth (Supplementary Material Table S1). Currently, there are 11 accepted species of Cutleria reported worldwide [52]. The life cycle of the genus is diplohaplontic and heteromorphic. Gametophytes or ‘Aglaozonia stage’ are relatively uniform in morphology, mostly filaments, discoidal-postrated (microtalli), whereas the sporophytes form compressed or cylindrically branched forms to fan-shaped types (macrotalli) [103,104]. The Dry Tortugas specimen may have been a prostrate, crustose thallus of Aglaozonia stage and may represent a possible new species of Cutleria.

- V. ORDER SYRINGODERMATALES E.C. Henry

- Fam. Syringodermataceae

- Microzonia J. Agardh 1894 [64]

- Microzonia floridana (Agardh) comb. nov.

Habit: see [41].

Barcoding and phylogenetic analyses: see [41].

4. Discussion/Conclusions

We learned that a great environmental tragedy (oil spill) can open up new and exciting research avenues and approaches for studying (brown) algal biodiversity. This study shows the importance of studying culturing samples and collection specimens to assess shifts in communities over time, and the effects of oil spills on calcifying organisms (rhodoliths) and their associated seaweeds.

Even though many macroalgal thalli are not currently found in the westernmost offshore banks of Louisiana, their cryptic, microscopic stages may persist within rhodoliths [4,13,14,17,18,92,105], providing potential for regeneration in both field and laboratory conditions. This idea aligns with the original framework proposed by [106], who conceptualized calcareous substrata as being true “banks of microscopic forms” capable of harboring dormant reproductive or minute stages of macroalgae. Our results support this hypothesis, as rhodoliths that appeared barren upon collection from deep banks (45–90 m) in the GMx produced a surprisingly diverse assemblage of brown macroalgae once placed under suitable ex situ conditions [14,17]. This demonstrates that microscopic algal phases can survive within rhodoliths, regenerate, and continue their life cycle when environmental constraints are dismissed ([13,14], this study). There is currently renewed interest [13,107] in understanding how these cryptic banks contribute to community persistence, recolonization dynamics, and ecosystem resilience. Taken together, our findings strengthen the idea that rhodoliths act as reservoirs of hidden macroalgal diversity and highlight the importance of incorporating microscopic stages into assessments of biodiversity and recovery potential in macroalgal-dominated systems.

The magnitude, drivers, and ecological implications of the decline in healthy rhodoliths beds and their associated macroalgal assemblages on the deep banks following the 2010 oil spill event in the NWGMx remain unclear [14,19]. What is clear, however, is that when rhodoliths were collected from the deep banks and placed in laboratory microcosms, the hidden microscopic brown algal stages inside the rhodoliths emerged from the surface and were able to regenerate and grow into mature thalli. This resilient response of rhodoliths in controlled conditions suggests that the oil spill may have exerted a substantial impact on these deep banks, for example, through long-term accumulation of hydrocarbons within the substratum or by altering key environmental and chemical processes in the habitat [5]. Such changes may have inhibited the ability of microscopic stages to resume and complete their life cycles in situ. This also reinforces the idea of rhodoliths beds as microscopic algal banks contributing to maintaining community resilience after adverse events. To mitigate the risk of rhodolith bed decline and potential loss of this biome, new conservation and protection initiatives now exist worldwide [108,109]. However, to fully comprehend these initiatives, more research is urgently needed, for example, assessing the effects of chemical changes in seawater due to climate change on the analysis of associated bacteria and small eukaryotes [13]. It is also important to investigate the life cycle and reproductive phases of rhodolith-forming corallines and their associated algae.

The present study reports, for the first time, reproductive structures (sori) on L. declerckii. Reproductive traits in Lobophora have been poorly documented. Previously, [110] described sporangial sori for L. ‘variegata’ from Australia, and more recently, [111] reported them in different Lobophora species (L. nigrescens, L. obscura, and L pachyventera) from eastern Asia and southeastern Australia. Lobophora declerckii is the most prevalent and widespread Lobophora species in the Greater Caribbean, where it forms large shelf-like blades exposed to light that can cover large areas on coral reefs [49]. This species was reported [65] growing at 36 m depth in Guadeloupe Is. (French West Indies). Documenting reproductive structures in L. declerckii is particularly significant because it suggests the species’ ability to complete its life cycle within mesophotic habitats, an essential criterion for establishing local self-sustaining populations [106,112]. Mesophotic ecosystems have been considered biodiversity reservoirs or refugia for shallow species affected by direct and indirect anthropogenic events [13], reinforcing the importance of investigating the 2010 oil spill effects on the deep rhodolith beds of the GMx. Evidence of reproductive structures also enlightens population resilience, as taxa capable of continuous sexual or asexual recruitment typically show greater capacity to recover after disturbance and maintain long-term population stability [113,114]. Furthermore, the presence of sori suggests potential dispersal among mesophotic reefs, contributing to demographic and genetic connectivity across depth gradients [4,115].

Some previous studies have reported brown macroalgae associated with rhodolith beds; for example, 24 brown species were reported in Bay of Islands, northeastern North Island [116]. In Espírito Santo State (Brazil), 26 brown algae were found on rhodoliths between 4 and 18 m depth [117]. Our study represents the first characterization of seaweeds in association with rhodoliths collected at considerable depths (65–90 m) in the Gulf of Mexico. Rhodolith beds have been documented worldwide across a range of depths and habitats, exhibiting notable structural differences. Intertidal to shallow subtidal beds are described from tidal platforms, reef areas, seagrasses, and bays exposed to daily tidal currents and seasonal storm conditions. However, rhodolith beds have also been reported in deeper areas, such as in the Mediterranean Sea [118], where they are most commonly found between 30 and 75 m, but can extend to depths of up to 150 m on seamounts in the Balearic Sea [119]. These depth-related variations in habitat conditions result in differences in light availability, hydrodynamics, and overall environmental regimes among rhodolith banks, which can ultimately shape their ecological roles and influence associated biodiversity.

This study provides new insights and opportunities for advancing research on algal developmental processes, taxonomy, and ecology. Some taxa found may represent undescribed entities (Stypopodium sp.) and others corresponded to new records for the GMx (genus Cutleria, Dictyota cymatophila, D. cf. humifusa, D. cf. friabilis, and D. cf. liturata), greatly extending their documented geographic and ecological distributions. Dictyota species and Stypopodium sp. were observed emerging exclusively in microcosm post-DWH event from Ewing Bank, whereas Cutleria sp. and Lobophora tortugensis were the only taxa found living on rhodoliths in the field at the Dry Tortugas post-DWH. Ewing Bank was a site heavily impacted by the DWH and was the only GMx location examined in this study both before and after the event (see Figure 1; Supplementary Material Table S1). Despite the absence of a detailed floristic survey of brown algae at this site prior to the oil spill, Padina profunda was found during the 2008 expedition, but it was not observed growing post-DWH, even at Dry Tortugas, a more distant location from the DWH. Dictyopteris delicatula, Spatoglossum cf. schroederi, Nereia tropica, Sporochnus bolleanus, and Rosenvingea cf. intricata were previously reported for the GMx [27] and were also observed growing post-DWH in mesocosms at Ewing Bank.

These findings offer robust molecular and morphological evidence that refine species delimitation, clarify long-standing taxonomic uncertainties within the Phaeophyceae, and highlight mesophotic rhodolith beds as previously unrecognized reservoirs of cryptic brown algal diversity. Given their ecological significance and role as deepwater biodiversity hotspots, our results underscore the urgent need to incorporate mesophotic rhodolith habitats into conservation priorities [108,109]. Current conservation frameworks and international efforts related to rhodolith preservation further support the necessity for targeted protection of these habitats in the Gulf of Mexico, reinforcing their value as essential reservoirs of cryptic brown algal diversity and overall marine biodiversity.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d17120860/s1, Table S1: Collection information for samples from which new sequences were generated for this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization O.C. and S.F.; methodology O.C. and S.F.; formal analysis O.C., data curation O.C.; resources S.F. and O.C.; writing—original draft O.C.; writing—review and editing O.C. and S.F.; funding acquisition S.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by NSF grants DEB-0315995, DEB-1045690, DEB-1456674, and DEB-1754504.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All DNA sequences are being submitted to Genbank during the review of this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the crew of R/V Pelican for their help with sampling protocols aboard ship, and their close research collaborators William Schmidt, Thomas Sauvage, Sherry Krayesky-Self, Joseph Richards, Natalia Arakaki, James Norris, Emma Hickerson, and Darryl Felder. The authors also thank two anonymous evaluators for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Foster, M.S. Rhodoliths: Between rocks and soft places—Minireview. J. Phycol. 2001, 37, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riosmena-Rodríguez, R.; Nelson, W.; Aguirre, J. (Eds.) Rhodolith/Maërl Beds: A Global Perspective; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Amado-Filho, G.M.; Moura, R.L.; Bastos, A.C.; Salgado, L.T.; Sumida, P.Y.; Guth, A.Z.; Francini-Filho, R.B.; Pereira-Filho, G.H.; Abrantes, D.P.; Brasileiro, P.S.; et al. Rhodolith beds are major CaCO3 biofactories in the tropical South West Atlantic. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e35171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spalding, H.L.; Amado-Filho, G.M.; Bahia, R.G.; Ballantine, D.L.; Fredericq, S.; Leichter, J.J.; Nelson, W.A.; Slattery, M.; Tsuda, R.T. Macroalgae. In Mesophotic Coral Ecosystems; Coral Reefs of the World, Volume 12; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 507–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezak, R.; Bright, T.J.; McGrail, D.W. Reefs and Banks of the Northwestern Gulf of Mexico: Their Geological, Biological, and Physical Dynamics; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1985; 259p. [Google Scholar]

- Felder, D.L.; Camp, D.K. (Eds.) Gulf of Mexico Origin, Waters and Biota, Biodiversity; A & M University Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2009; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Minnery, G.A.; Rezak, R.; Bright, T.J. Chapter 18: Depth zonation and growth form of crustose coralline algae: Flower Garden Banks, northwestern Gulf of Mexico. In Paleoalgology: Contemporary Research and Applications; Toomey, D.F., Nitecki, M.H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 238–246. [Google Scholar]

- Minnery, G.A. Crustose coralline algae from the Flower Garden Banks, Northwestern Gulf of Mexico—Controls on distribution and growth-morphology. J. Sedim. Petrol. 1990, 60, 992–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Hickerson, E.L.; Schmahl, G.P.; Robart, M.; Precht, W.E.; Caldow, C. The State of Coral Reef Ecosystems of the Flower Garden Banks, Stetson Bank, and Other Banks in the Northwestern Gulf of Mexico. In The State of Coral Reef Ecosystems of Flower Garden Banks; 2008; pp. 190–218. [Google Scholar]

- Gore, R.H. The Gulf of Mexico; Pineapple Press: Sarasota, FL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Slowey, N.; Holcombe, T.; Betts, M.; Bryant, W. Habitat islands along the shelf edge of the northwestern Gulf of Mexico. In A Scientific Forum on the Gulf of Mexico: The Islands in the Stream Concept; Ritchie, K.B., Keller, B., Eds.; Marine Sanctuaries Conservation Series; NOAA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2008; pp. 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon, K.M.; Ackerman, S.D.; Rozycki, E. Texture, Carbonate Content, and Preliminary Maps of Surficial Sediments, Flower Garden Banks Area, Northwest Gulf of Mexico Outer Shelf; U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 03-002; USGS: Reston, VA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fredericq, S.; Krayesky-Self, S.; Sauvage, T.; Richards, J.; Kittle, R.; Arakaki, N.; Hickerson, E.; Schmidt, W.E. The critical importance of rhodoliths in the life cycle completion of both macro- and microalgae, and as holobionts for the establishment and maintenance of biodiversity. Front. Mar. Sci.-Mar. Ecosyst. Ecol. 2019, 5, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredericq, S.; Arakaki, N.; Camacho, O.; Gabriel, D.; Krayesky, D.; Self-Krayesky, S.; Rees, G.; Richards, J.; Sauvage, T.; Venera-Ponton, D.; et al. A dynamic Approach to the study of rhodoliths: A case study for the northwestern Gulf of Mexico. Cryptogam. Algol. 2014, 35, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.L.; Gabrielson, P.W.; Fredericq, S. New insights into the genus Lithophyllum (Lithophylloideae, Corallinaceae, Corallinales) from offshore the NW Gulf of Mexico. Phytotaxa 2014, 190, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.L.; Vieira-Pinto, T.; Schmidt, W.E.; Sauvage, T.; Gabrielson, P.W.; Oliveira, M.C.; Fredericq, S. Molecular and morphological diversity of Lithothamnion spp. (Hapalidiaceae, Hapalidiales) from deepwater rhodolith beds in the northwestern Gulf of Mexico. Phytotaxa 2016, 278, 81–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krayesky-Self, S.; Schmidt, W.E.; Phung, D.; Henry, C.; Sauvage, T.; Camacho, O.; Felgenhauer, B.E.; Fredericq, S. Eukaryotic life inhabits rhodolith-forming coralline algae (Hapalidiales, Rhodophyta), remarkable marine benthic microhabitats. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krayesky-Self, S.; Richards, J.L.; Rahmatian, M.; Fredericq, S. Aragonite infill in overgrown conceptacles of coralline Lithothamnion spp. (Hapalidiaceae, Hapalidiales, Rhodophyta): New insights in biomineralization and phylomineralogy. J. Phycol. 2016, 52, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felder, D.L.; Thoma, B.P.; Schmidt, W.E.; Sauvage, T.; Self-Krayesky, S.; Chistoserdov, A.; Bracken-Grissom, H.; Fredericq, S. Seaweeds and decapod crustaceans on Gulf deep banks after the Macondo Oil Spill. BioScience 2014, 64, 808–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freiwald, A.; Henrich, R. Reefal coralline algal build-ups within the Arctic Circle: Morphology and sedimentary dynamics under extreme environmental seasonality. Sediment 1994, 41, 963–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, C.B.; Hénaff, M.L.; Aman, Z.M.; Subramaniam, A.; Helgers, J.; Wang, D.P.; Kourafalou, V.H.; Srinivasan, A. Evolution of the Macondo well blowout: Simulating the effects of the circulation and synthetic dispersants on the subsea oil transport. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 13293–13302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabalais, N. Assessing early looks at biological responses to the Macondo Event. BioScience 2014, 4, 757–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gavio, B.; Hickerson, E.; Fredericq, S. Platoma chrysymenioides sp. nov. (Schizymeniaceae), and Sebdenia integra sp. nov. (Sebdeniaceae), two new red algal species from the northwestern Gulf of Mexico, with a phylogenetic assessment of the Cryptonemiales complex (Rhodophyta). Gulf Mexico Sci. 2005, 23, 38–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavio, B.; Fredericq, S. New species and new records of offshore members of the Rhodymeniales (Rhodophyta) in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Gulf Mexico Sci. 2005, 23, 58–83. [Google Scholar]

- Arakaki, N.; Suzuki, M.; Fredericq, S. Halarachnion (Furcellariaceae, Rhodophyta), a newly reported genus for the Gulf of Mexico, with the description of H. louisianensis sp. nov. Phycol. Res. 2014, 62, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredericq, S.; Cho, T.O.; Earle, S.A.; Gurgel, C.F.; Krayesky, D.M.; Mateo Cid, L.E.; Mendoza Gonzáles, A.C.; Norris, J.N.; Suárez, A.M. Seaweeds of the Gulf of Mexico. In Gulf of Mexico: Its Origins, Waters, and Biota. I. Biodiversity; Felder, D.L., Camp, D.K., Eds.; Texas A&M Univ. Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2009; pp. 187–259. [Google Scholar]

- Earle, S.A. Phaeophyta of the Eastern Gulf of Mexico. Phycologia 1969, 7, 71–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, E.A.; Williams, J.O. Rationale and pertinent data. Mem. Hourglass Cruises 1969, 1, 11–50. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, W.R. Marine Algae of the Eastern Tropical and Subtropical Coasts of the America; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1960; pp. 1–870. [Google Scholar]

- Win, N.N.; Hanyuda, T.; Draisma, S.G.A.; Verheij, E.; van Reine, W.F.P.; Lim, P.-E.; Phang, S.-M.; Kawai, H. Morphological and molecular evidence for two new species of Padina (Dictyotales, Phaeophyceae), P. sulcata and P. calcarea, from the central Indo-Pacific region. Phycologia 2012, 51, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, C.J.; Mathieson, A. The Seaweeds of Florida; University Press of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2008; pp. 1–591. [Google Scholar]

- Tronholm, A.; Steen, F.; Tyberghein, L.; Leliaert, F.; Verbruggen, H.; Sigua, M.A.R.; De Clerck, O. Species delimitation, taxonomy, and biogeography of Dictyota in Europe (Dictyotales, Phaeophyceae). J. Phycol. 2010, 46, 1301–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tronholm, A.; Sansón, M.; Afonso-Carrillo, J.; Verbruggen, H.; De Clerck, O. Niche partitioning and the coexistence of two cryptic Dictyota (Dictyotales, Phaeophyceae) species from the Canary Islands. J. Phycol. 2010, 46, 1075–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, D.; Schmidt, W.E.; Micael, J.; Moura, M.; Fredericq, S. DNA Barcode-assisted inventory of the marine macroalgae from the Azores, including new records. Phycology 2024, 4, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, L.; Payri, C.; Couloux, A.; Cruaud, C.; De Reviers, B.; Rousseau, F. Molecular phylogeny of the Dictyotales and their position within the Phaeophyceae, based on nuclear, plastid and mitochondrial DNA sequence data. Mol. Phylogenetics Evol. 2008, 49, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Win, N.N.; Hanyuda, T.; Arai, S.; Uchimura, M.; Prathep, A.; Draisma, S.G.A.; Phang, S.M.; Abbott, I.A.; Millar, A.J.K.; Kawai, H. A taxonomic study of the genus Padina (Dictyotales, Phaeophyceae) including the descriptions of four new species from Japan, Hawaii, and the Andaman Sea. J. Phycol. 2011, 47, 1193–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattio, L.; Payri, C. Assessment of five markers as potential barcodes for identifying Sargassum subgenus Sargassum species (Phaeophyceae, Fucales). Cryptogam. Algol. 2010, 31, 467–485. [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood, A.R.; Presting, G.G. Universal primers amplify a 23s RNA plastid marker in eukaryotic algae and cyanobacteria. J. Phycol. 2007, 43, 605–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanfear, R.; Calcott, B.; Ho, S.; Guindon, S. PartitionFinder: Combined selection of partitioning schemes and substitution model for phylogenetic analyses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2012, 29, 1695–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifinopoulos, J.; Nguyen, L.T.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. W-IQ-TREE: A fast online phylogenetic tool for maximum likelihood analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, O.; Sauvage, T.; Fredericq, S. Taxonomic transfer of Syrigoderma to Microzonia (Syringodermataceae, Syrigodermatales) including the new record of M. floridana comb. nov. for the Gulf of Mexico. Phycologia 2018, 57, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, O.; Fernández-García, C.; Vieira, V.; Gurgel, C.F.D.; Norris, J.N.; Freshwater, D.W.; Fredericq, S. The systematics of Lobophora (Dictyotales, Phaeophyceae) in the Western Atlantic and Eastern Pacific Oceans: Eight new species. J. Phycol. 2019, 55, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamouroux, J.V.F. Exposition des caractères du genre Dictyota, et tableau des espèces qu’il renferme. J. Bot. 1809, 2, 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntze, O. Revisio generum plantarum… Leipzig, 1891–1898, 1, 2, 1–1011.

- Agardh, C.A. Species algarum rite cognitae…Lundae [Lund]: Ex officina Berlingiana 1820 ‘1821’, 1, 1–168.

- Schramm, A.; Mazé, H. Essai de Classification des Algues de la Guadeloupe; Hachette Livre BNF: Basse Terre, France, 1865; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Möbius, M. Bearbeitung der von H. Schenk in Brasilien gesammelten ALgen. Hedwigia 1889, 28, 309–347. [Google Scholar]

- De Toni, G.B.; Okamura, K. Neue meeresalgen aus Japan. Berichte Dtsch. Bot. Ges. 1895, 12, 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, C.; Henriques, F.; D’hondt, S.; Neto, A.I.; Almada, C.H.; Kaufmann, M.; Sansón, M.; Sangil, C.; De Clerck, O. Lobophora (Dictyotales) species richness, ecology and biogeography across the North-eastern Atlantic archipelagos and description of two new species. J. Phycol. 2020, 56, 346–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, C.; Steen, F.; D’hondt, S.; Bafort, Q.; Tyberghein, L.; Fernandez-Garcia, C.; Wysor, B.; Tronholm, A.; Mattio, L.; Payri, C.; et al. Global biogeography and diversification of a group of brown seaweeds (Phaeophyceae) driven by clade-specific evolutionary processes. J. Biogeogr. 2021, 48, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Jin, Z.; Wamg, Y.; Bi, Y.; Melton, J.T., III. Plastid genome of Dictyopteris divaricata (Dictyotales, Phaeophyceae): Understanding the evolution of plastid genomes in brown algae. Mar. Biotechnol. 2017, 6, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guiry, M.D.; Guiry, G.M. AlgaeBase. World-Wide Electronic Publication, University of Galway. Available online: https://www.algaebase.org (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Hörnig, I.; Schnetter, R.; Prud’homme van Reine, W.F.; Coppejans, E.; Achenbach-Wege, K.; Over, J.M. The genus Dictyota (Phaeophyceae) in the North Atlantic. I. A new generic concept and new species. Nova Hedwig. 1992, 54, 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- De Clerck, O. The genus Dictyota in the Indian Ocean. Opera Bot. Belg. 2003, 13, 1–205. [Google Scholar]

- Tronholm, A.; Leliaert, F.; Sansón, M.; Afonso-Carrillo, J.; Tyberghein, L.; Verbruggen, H.; De Clerck, O. Contrasting geographical distributions as a result of thermal tolerance and long-distance dispersal in two allegedly widespread tropical brown algae. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, F.; Vieira, C.; Leliaert, F.; Payri, C.; De Clerck, O. Biogeographic affinities of Dictyotales from Madagascar: A phylogenetic approach. Cryptogam. Algol. 2015, 36, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.A.; Motomura, T.; Choi, S.-W.; Loiseaux De-Goër, S.; Miller, S.K.A.; Karsten, U.; Yoon, H.S.; Lim, P.E.; Nagasato, C. Light and electron microscopy, molecular phylogeny and mannitol content of Dictyotopsis propagulifera (Dictyotales, Heterokontophyta) isolated from mangrove mud in Perak, Malaysia. Phycol. Res. 2025, 3, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setchell, W.A. Tahitian algae collected by W.A. Setchell, C.B. Setchell and H.E. Parks. Univ. Calif. Publ. Bot. 1926, 12, 61–142. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, P.C.; Basson, P.W.; Moe, R.L. Catalogue of the benthic marine algae of the Indian Ocean. Univ. Calif. Publ. Bot. 1996, 79, 1–1259. [Google Scholar]

- Agardh, J.G. Species genera et ordines algarum, … Vol. I. Algas fucoideas complectens. Lundae [Lund]: C.W.K. Gleerup 1848, 1–363.

- Kützing, F.T. Species Algarum... F.A. Brockhaus, 1849, 1–922. Lipsiae [Leipzig].

- Pereira Lopes-Filho, E.A.; Salgueiro, F.; Mattos Nascimento, S.; Gauna, M.C.; Parodi, E.R.; Campos De Paula, J. Molecular evidence of the presence of Dictyota dichotoma (Dictyotales: Phaeophyceae) in Argentina based on sequences from mtDNA and cpDNA and a discussion of its possible origin. N. Z. J. Bot. 2017, 55, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küpper, R.C.; Peters, A.F.; Kytinou, E.; Asensi, A.O.; Vieira, C.; Macaya, E.C.; De Clerck, O. Dictyota falklandica sp. nov. (Dictyotales, Phaeophyceae) from the Falkland Islands and southernmost South America. Phycologia 2019, 58, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agardh, J.G. Analecta algologica… Contin. I. Lunds Univ. Års-Skrift, Kongl. Fysiogr. Sällsk. i Lund Handl. 1894, 29(9), 1–144, 2 pl.

- Schultz, N.E.; Lane, C.E.; Le Gall, L.; Gey, D.; Bigney, A.R.; De Reviers, B.; Rousseau, F.; Schneider, C.W. A barcode analysis of the genus Lobophora (Dictyotales, Phaeophyceae) in the western Atlantic Ocean with four novel species and the epitypification of L. variegata (J.V. Lamouroux) E.C. Oliveira. Eur. J. Phycol. 2015, 50, 482–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adanson, M. Familles des Plantes; Imprimeur-Librarie: Paris, France, 1763; pp. 2–640. [Google Scholar]

- Win, N.N.; Hanyuda, T.; Kato, A.; Shimabukuro, H.; Uchimura, M.; Kawai, H.; Tokeshi, M. Global diversity and geographic distributions of Padina species (Dictyotales, Phaeophyceae): Insights based on molecular and morphological analyses. J. Phycol. 2021, 57, 454–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaillard, J. Un Padina nouveau des côtes d’Afrique: Padina glabra sp. nova. Phycologia 1966, 5, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynne, M.J.; De Clerck, O. First reports of Padina antillarum and P. glabra (Phaeophyta-Dictyotaceae) from Florida, with a key to the western Atlantic species of the genus. Caribb. J. Sci. 1999, 35, 286–295. [Google Scholar]

- Wynne, M.J. First report of the brown algal Padina glabra (Ochrophyta: Dictyotales) from the coast of Texas and the Gulf of Mexico. Texas J. Sci. 2008, 60, 227–232. [Google Scholar]

- Mateo-Cid, L.E.; Mendoza-González, A.C.; Fredericq, S. A checklist of subtidal seaweeds from Campeche Banks, Mexico. Acta Bot. Venezuel. 2013, 36, 92–108. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, C.W.; Searles, R.B. North Carolina marine algae. II. New records and observations of the benthic offshore flora. Phycologia 1973, 12, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, N.L.; Millspaugh, C.F. The Bahama Flora. New York 1920, i-viili + 1695.

- Sonder, O.G. Die Algen des tropischen Australiens. Abhandlungen aus dem Gebiete der Naturwissenschaften herausgegeben von dem Naturwissenschaftlichen Verein in Hamburg 1871, 5(2), 33–74, pls I–VI.

- Kützing, F.T. Phycologia generalis …Leipzig: F.A. Brockhaus, 1843, 1, [i]-xxxii, 1–142, [part 2:] 143–458, 1, err.], pls 1–80.

- Kützing, F.T. Tabulae Phycologicae; Nordhausen, 1859, 9, 1–42, 100 pls.

- Agardh, C.A. Systema Algarum; Literis Berlingianis [Berling]: Lund, Sweden, 1824; pp. 1–312. [Google Scholar]

- Greville, R.K. Algae Britannicae; McLachlan & Stewart: Edinburgh, UK; Baldwin & Cradock: London, UK; Edinburgh, UK, 1830; pp. 1–218. [Google Scholar]

- Hoshina, R.; Hasegawa, K.; Tanaka, J.; Hara, Y. Molecular phylogeny of the Dictyotaceae (Phaeophyceae) with emphasis on their morphology and its taxonomic implication. Jpn. J. Phycol. 2004, 52, 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Jelić, L.P.; Cvitković, I.; Nejašmić, J.; Cvjetan, S.; Despalatović, M.; Mucko, M.; Kvesić Ivanković, M.; Žuljević, A. Rapid invasion of the non-indigenous brown alga Stypopodium schimperi in the Adriatic Sea. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 2025, 26, 657–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papenfuss, G.F. Notes on South African marine algae. I. Bot. Notiser 1940, 1940, 200–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaegashi, K.; Yamagishi, Y.; Uwai, S.; Abe, T.; Santiañez, W.J.E.; Kogame, K. Two species of the genus Acinetospora (Ectocarpales, Phaeophyceae) from Japan: A. filamentosa comb. nov. and A. asiatica sp. nov. Bot. Mar. 2015, 58, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvageau, C. Les Acinetospora et la sexualité des Tiloptéridacées. J. Bot. Morot. 1899, 13, 107–127. [Google Scholar]

- Avila-Peltroche, J.; Oteng’o, A.O.; Jeong, S.Y.; Won, B.Y.; Cho, T.O. A new record of Feldmannia chitonicola from Korea based on laboratory culture and molecular data. Hangug Hwangyeong Saengmul Haghoeji 2019, 37, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberfeld, T.; Racalt, M.-F.L.P.; Fletcher, R.L.; Couloux, A.; Rousseau, F.; De Reviers, B. Systematics and evolutionary history of pyrenoid-bearing taxa in brown algae (Phaeophyceae). Eur. J. Phycol. 2011, 46, 361–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, A.F.; Couceiro, L.; Tsiamis, K.; Küpper, F.; Valero, M. Barcoding of cryptic stages of brown algae isolated from incubated substratum reveals high diversity in Acinetosporaceae (Ectocarpales, Phaeophyceae). Cryptogam. Algol. 2015, 36, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Børgesen, F. The marine algae of the Danish West Indies. Part 2. Phaeophyceae. Dansk Bot. Arkiv 1914, 2, 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lipkin, Y.; Silva, P.C. Marine algae and seagrasses of the Dahlak Archipelago, southern Red Sea. Nova Hedwig. 2002, 75, 1–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogame, K.; Horiguchi, T.; Masuda, M. Phylogeny of the order Scytosiphonales (Phaeophyceae) based on DNA sequences of rbcL, partial rbcS, and partial LSU nrDNA. Phycologia 1999, 38, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silberfeld, T.; Leigh, J.W.; Verbruggen, H.; Cruaud, C.; de Reviers, B.; Rousseau, F.A. Multi-locus time-calibrated phylogeny of the brown algae (Heterokonta, Ochrophyta, Phaeophyceae): Investigating the evolutionary nature of the ‘brown algal crown radiation. J. Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 2010, 56, 659–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M.; Hong, D.D.; Boo, S.M. Phylogenetic relationships of Rosenvingea (Scytosiphonaceae, Phaeophyceae) from Vietnam based on cox3 and psaA sequences. Algae 2014, 29, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauvage, T.; Schmidt, W.E.; Suda, S.; Fredericq, S. A metabarcoding framework for facilitated survey of coral reef and rhodolith endolithic communities with tufA. BMC Ecol. 2016, 16, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynne, M.J. Rosenvingea antillarum (P. Crouan & H. Crouan) comb. nov. to replace R. floridana (W.R. Taylor) W.R. Taylor (Scytosiphonales, Phaeophyta). Cryptogam. Algol. 1997, 18, 331–336. [Google Scholar]

- Agardh, C.A. Synopsis algarum Scandinaviae… Lundae [Lund]: Ex officina Berlin-giana 1817, 1–135.

- Montagne, C. Sylloge generum specierumque cryptogamarum …. 1856, 1–498. Parisiis [Paris] & Londini [London]: Sumptibus J.-B. Baillière…; H. Baillière….

- Harvey, W.H. Phycologia Australica; Lovell Reeve & Co.: London, UK, 1858; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Wynne, M.J. The benthic marine algae of the tropical and subtropical Western Atlantic: Changes in our understanding in the last half century. Algae 2011, 26, 109–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanardini, G. Memoria sulla Desmarestia filiformis di Giacobbe Agardh et sulle Chordariee in generale. Atti Del Settima Congr. Degli Sci. Italani Napoli 1846, 2, 899–900. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, W.R. Notes on algae from the tropical Atlantic Ocean. IV. Pap. Mich. Acad Sci. Arts Lett. 1955, 40, 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, W.R. The Marine Algae of Florida with Special Reference to the Dry Tortugas; Publ. Carnegie Inst.: Washington, DC, USA, 1928; Volume 379, pp. 1–219. [Google Scholar]

- Yee, N.R.; Millar, A.J.K.; Huisman, J.M. Sporochnales. In Algae of Australia: Marine Benthic Algae of North-Western Australia. 1. Green and Brown Algae; Huisman, J.M., Ed.; ABRS & CSIRO Publishing: Canberra, Australia; Melbourne, Australia, 2015; pp. 237–242. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.W.; Graf, L.; Peters, A.F.; Cock, J.M.; Nishitsuji, K.; Arimoto, A.; Shoguchi, E.; Nagasato, C.; Choi, C.G.; Yoon, H.S. Organelle inheritance and genome architecture variation in isogamous brown algae. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, H.; Kogishi, K.; Hanyuda, T.; Kitayama, T. Taxonomic revision of the genus Cutleria proposing a new genus Mutimo to accommodate M. cylindricus (Cutleriaceae, Phaeophyceae). Phycol. Res. 2012, 60, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allender, B.M.; Kraft, G.T. The marine algae of Lord Howe Island (New South Wales): The Dictyotales and Cutleriales (Phaeophyta). Brunonia 1983, 6, 73–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krayesky-Self, S.; Phung, D.; Schmidt, W.E.; Henry, C.; Sauvage, T.; Butler, L.; Fredericq, S. First report of an endolithic species of Rhodosorus Geitler (Rhodophyta) growing inside Lithothamnion rhodoliths offshore Louisiana, northwestern Gulf of Mexico. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, A.; Santelices, B. Banks of algal microscopic forms: Hypotheses on their functioning and comparisons with seed banks. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1991, 79, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenrock, K.M.; McHugh, T.A.; Krueger-Hadfield, S.A. Revisiting the ‘bank of microscopic forms’ in macroalgal-dominated ecosystems. J. Phycol. 2021, 57, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, A.D.d.; Dolbeth, M.; Christoffersen, M.L.; Zúñiga-Upegui, P.T.; Venâncio, M.; Lucena, R.F.P. An Overview of Rhodoliths: Ecological Importance and Conservation Emergency. Life 2023, 13, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, N.; Magris, R.A.; Berchez, F.; Bernardino, A.F.; Ferreira, C.E.L.; Francini-Filho, R.B.; Gaspar, T.L.; Pereira-Filho, G.H.; Rossi, S.; Silva, J.; et al. Rhodolith beds in Brazil: A natural heritage in need of conservation. Divers. Distrib. 2025, 31, e13960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.A.; Clayton, M.N.; Harvey, A.S. Comparative studies on sporangial distribution and structure in species of Zonaria, Lobophora and Homoeostrichus (Dictyotales, Phaeophyceae) from Australia. Eur. J. Phycol. 1994, 29, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Hanyuda, T.; Lim, P.E.; Tanaka, J.; Gurgel, C.F.D.; Kawai, H. Taxonomic revision of the genus Lobophora (Dictyotales, Phaeophyceae) based on morphological evidence and analyses rbcL and cox3 gene sequences. Phycologia 2012, 51, 500–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahng, S.E.; Copus, J.M.; Wagner, D. Mesophotic Coral Ecosystems. In Marine Animal Forests; Loya, Y., Puglise, K.A., Bridge, T.C.L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayton, P.K. Ecology of kelp communities. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1985, 16, 215–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, T.P.; Baird, A.H.; Bellwood, D.R.; Card, M.; Connolly, S.R.; Folke, C.; Grosberg, R.; Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Jackson, J.B.; Kleypas, J.; et al. Climate change, human impacts, and the resilience of coral reefs. Science 2003, 301, 929–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, G.; Kregting, L.; Beatty, G.E.; Cole, C.; Elsäßer, B.; Savidge, G.; Provan, J. Understanding macroalgal dispersal in a complex hydrodynamic environment: A combined population genetic and physical modelling approach. J. R. Soc. Interface 2014, 11, 20140197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, W.; D’Archino, R.; Neill, K.; Farr, T. Macroalgal diversity associated with rhodolith beds in northern New Zealand. Cryptogam. Algol. 2014, 35, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado-Filho, G.M.; Maneveldt, G.W.; Pereira-Filho, G.H.; Manso, R.C.C.; Bahia, R.G.; Barros-Barreto, M.B.; Guimarães, S.M.P.B. Seaweed diversity associated with a Brazilian tropical rhodolith bed. Cienc. Mar. 2010, 36, 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, D.; Babbini, L.; Ramos-Esplá, A.A.; Salomidi, M. Mediterranean Rhodoliths Beds. In Rhodolith/Maërl Beds: A Global Perspective; Riosmena-Rodriguez, R., Nelson, W., Auirre, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, R.; Pastor, X.; de la Torriente, A.; García, S. Deep-sea coralligenous beds observed with ROV on four seamounts in the Western Mediterranean Sea. In UNEP—MAP—RAC/SPA, Proceedings of the 1st Medit Symp on the Coralligenous and Other Calcareous Concretions, Tabarka, 15–16 January 2009; Pergent_Martini, C., Brichet, M., Eds.; CAR/ASP Publishing: Tabarka, Tunisia, 2009; pp. 148–150. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).