A Secondary Analysis of Invasion Risk in the Context of an Altered Thermal Regime in the Great Lakes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Vector Subcriterion: A transport vector currently exists that could move the species into the Great Lakes. The species is likely to tolerate/survive transport (including in resting stages) in the identified vector. The species has a probability of being introduced multiple times or in large numbers.

- Reproduction and Overwintering Subcriterion: In addition, based on known tolerances or climate matching, the species is likely to be able to successfully reproduce and overwinter in the Great Lakes.

- Impact Subcriterion: In addition, the species has been known to impact other systems which it has invaded or is assessed as likely to impact the Great Lakes system.

- Alternatively, the species has been officially listed as a potential invasive species of concern by federal, state or provincial authorities with jurisdiction in the Great Lakes basin.

- Alternatively, the species was previously established (evidence of overwintering and reproduction below the ordinary high water mark) but the population subsequently failed.

| Parameter | Scenario | Superior | Michigan | Huron | Erie | Ontario | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Average Water Temperature | 2025 | 15.1 | 19.7 | 19.7 | 23.3 | 21.6 | [38] |

| 2050 | 18.6 | 21.8 | 21.8 | 24.8 | 24.0 | [38] | |

| Maximum Extreme Water Temperature | 2025 | 18.1 | 22.7 | 22.7 | 23.3 | 24.6 | [38] |

| 2050 | 21.6 | 24.8 | 24.8 | 27.8 | 27.0 | [38,40] | |

| Days above 10 °C Water Temperature | 2025 | 85 | 134 | 134 | 184 | 149 | [38] |

| 2050 | 131 | 168 | 168 | 217 | 189 | [38] | |

| Ice Cover (Ice Days) | 2025 | 189 | 182 | 182 | 168 | 175 | [44] |

| 2050 | 159 | 165 | 157 | 148 | 161 | [19,44,45] | |

| Minimum Average Air Temperature | 2025 | −16.2 | −8.4 | −8.4 | −5.8 | −9.7 | [46] |

| 2050 | −12.2 | −4.9 | −4.9 | −2.3 | −6.2 | [39,46] | |

| Max Average Air Temperature | 2025 | 22.6 | 27.2 | 27.2 | 26.4 | 25.2 | [46] |

| 2050 | 25.9 | 30.5 | 30.5 | 29.7 | 28.5 | [39,46] | |

| Days above 32.2 °C Air Temperature | 2025 | 2.15 | 8.2 | 8.2 | 7.5 | 3.4 | [46] |

| 2050 | 12–32 | 18–58 | 28–48 | 28–58 | 23–43 | [42] | |

| Frost-free Season (days) | 2025 | 112–161 | 133–192 | 112–192 | 143–212 | 122–192 | [47] |

| 2050 | 132–181 | 153–212 | 132–212 | 163–232 | 153–212 | [42,48] |

| Parameter | Yes | Probably | Possibly | Unlikely | No |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature Maximum | Species’ water temperature range falls fully within predicted extreme maximum water temperatures. | Species’ water temperature range is not known in full, but mostly falls within predicted average high water temperatures, or the species is known to inhabit colder water below the summer thermocline. | Insufficient data, but range indicates a possibility of survival in expected high average water temperatures. | Data is limited, but suggests a low tolerance for expected water temperature maximums; species may engage in adaptive behaviors to avoid high-temperature regions. | None of the lakes are expected to have cool enough surface temperatures for this species’ survival, and they are unlikely to inhabit colder water below the summer thermocline. |

| Optimal Temperature | Species’ optimal temperature range or temperature required for reproduction falls within −6 °C or +2 °C of expected maximum average temperatures. | Conflicting information exists on species’ optimal temperature range, but conditions described by at least one set of data are available. | A lake meets one of the previous qualifications under the “Yes” condition, but not verifiably both. | No lake is likely to consistently meet the species’ optimal temperature conditions, but they may be temporarily present, or exist in small and specific areas of a lake. | None of the lakes are reasonably expected to meet the species’ optimal temperature conditions. |

| Winter Conditions | The species is known to overwinter in equivalent to or harsher conditions than expected winter conditions. | The species adapts behaviorally to winter conditions and/or is known to overwinter under ice cover conditions that are not as extreme as those expected in the lakes. | Data may be limited, but does not contraindicate an ability to overwinter, and/or specific habitat conditions are preferred for successful overwintering. | Data is limited, but suggests a low tolerance for winter conditions. | Data indicates species will not be able to tolerate expected winter conditions. |

| Air Temperature Extremes * | The species’ existing range and/or recorded tolerances fully include the expected climatic conditions. | The species’ recorded tolerances mostly include the expected climatic conditions such that local variation is likely to provide appropriate habitat. | Data may be limited, but does not contraindicate the potential of climatically appropriate available habitat. | Data suggests an overall inability to tolerate expected climate conditions in any lake, but species may find habitat in a few specific locations due to variability. | The species is definitively unable to tolerate expected extreme air temperature conditions in the region of any lake. |

| Optimal Climate * | The species’ optimal air temperature range, thermal conditions required for growth/reproduction, or necessary frost-free season is consistently present within the area/shoreline. | The species’ optimal climate conditions are likely to be present within the region | The species’ optimal climate conditions have the potential to be present, but are not expected to be consistently present over multiple years. | No lake region is likely to consistently meet the species’ optimal climate conditions, but they may be temporarily present in some years, or exist variably in small pockets of the region. | No lake region is expected to meet the species’ optimal climate conditions. |

- Increased Risk—Based on an increase in overlap over time between lake conditions and species temperature parameters, temperature effects expected as a result of 2050 climate change will make the Great Lakes more hospitable to this species than previously.

- Neutral—The species is equally as likely to establish in 2050 climate conditions as it is currently/historically.

- Decreased Risk—The effects of 2050 climate change will decrease the amount of viable thermal habitat for this species.

- Insufficient information—Data is insufficient to make a judgment.

- High—An individual lake was identified as consistently containing viable thermal habitat across parameters for a species.

- Medium—The individual lake was identified as only partially fulfilling a species’ thermal habitat requirements in at least one parameter, or doing so inconsistently.

- Low—The individual lake fell entirely outside at least one thermal parameter for a species.

3. Results

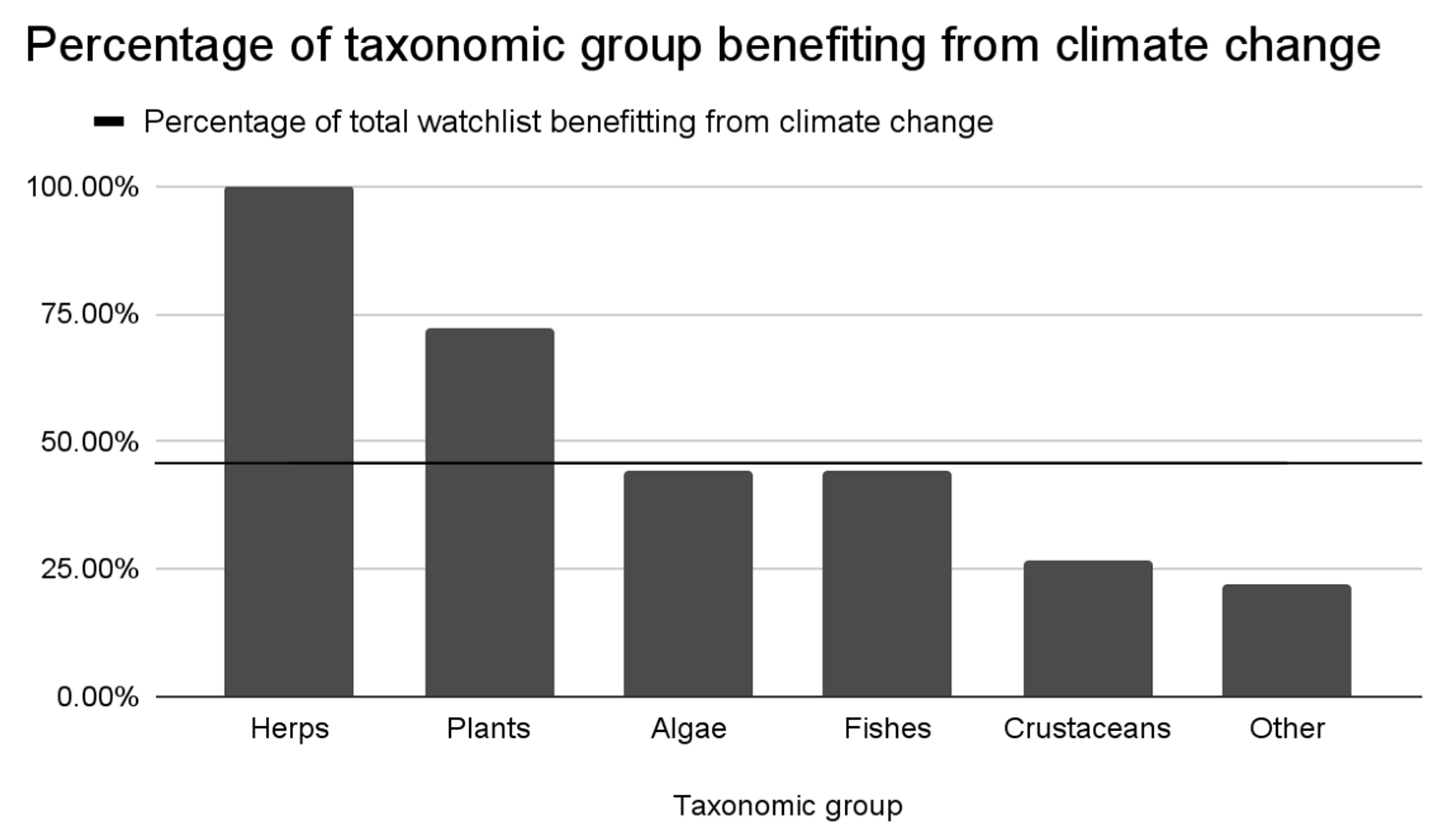

3.1. Impact of Lake Warming on the Establishment Risk for Watchlist Species

| Taxonomic Group | Watchlist Species | Current Establishment Risk | Increased Risk | Neutral Risk | Decreased Risk | Insufficient Information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algae | Chaetoceros muelleri | Failed | x | |||

| (n = 9) | Hymenomonas roseola | Failed | x | |||

| Pleurosira laevis | Failed | x | ||||

| Prymnesium parvum | Moderate | x | ||||

| Sphacelaria fluviatilis | Failed | x | ||||

| Sphacelaria lacustris | Failed | x | ||||

| Thalassiosira bramaputrae | Failed | x | ||||

| Ulva intestinalis | Failed | x | ||||

| Ulva prolifera | Failed | x | ||||

| Plants | Alternanthera philoxeroides | Moderate | x | |||

| (n = 18) | Arundo donax | High | x | |||

| Crassula helmsii | Moderate | x | ||||

| Egeria densa | Moderate | x | ||||

| Egeria najas | Moderate | x | ||||

| Eichhornia crassipes | Moderate | x | ||||

| Hottonia palustris | Moderate | x | ||||

| Hygrophila polysperma | Moderate | x | ||||

| Impatiens balfourii | Moderate | x | ||||

| Ludwigia grandiflora | High | x | ||||

| Lysimachia punctata | Moderate | x | ||||

| Myriophyllum aquaticum | Moderate | x | ||||

| Lagarosiphon major | Moderate | x | ||||

| Nelumbo nucifera | High | x | ||||

| Oenanthe javanica | Moderate | x | ||||

| Pistia stratiotes | Moderate | x | ||||

| Sparganium erectum | Moderate | x | ||||

| Typha laxmannii | Moderate | x | ||||

| Herps | Kinosternon subrubrum | Moderate | x | |||

| (n = 5) | Pseudemys concinna | Moderate | x | |||

| Macrochelys temminckii | Low | x | ||||

| Trachemys scripta scripta | Moderate | x | ||||

| Xenopus laevis | High | x | ||||

| Fishes | Alburnus alburnus | High | x | |||

| (n = 25) | Alosa chrysochloris | Moderate | x | |||

| Babka gymnotrachelus | High | x | ||||

| Carassius carassius | Moderate | x | ||||

| Channa argus | Moderate | x | ||||

| Clupeonella cultriventris | Moderate | x | ||||

| Cyprinella lutrensis | High | x | ||||

| Cyprinella whipplei | Moderate | x | ||||

| Hypophthalmichthys molitrix | Moderate | x | ||||

| Hypophthalmichthys nobilis | Moderate | x | ||||

| Ictalurus furcatus | Moderate | x | ||||

| Knipowitschia caucasica | Moderate | x | ||||

| Lepomis auritus | Moderate | x | ||||

| Leuciscus idus | Moderate | x | ||||

| Leuciscus leuciscus | Moderate | x | ||||

| Mylopharyngodon piceus | Moderate | x | ||||

| Neogobius fluviatilis | High | x | ||||

| Osmerus eperlanus | Moderate | x | ||||

| Perca fluviatilis | High | x | ||||

| Percottus glenii | High | x | ||||

| Phoxinus phoxinus | Moderate | x | ||||

| Rutilus rutilius | Moderate | x | ||||

| Sander lucioperca | Moderate | x | ||||

| Syngnathus abaster | Moderate | x | ||||

| Tinca tinca | Moderate | x | ||||

| Crustaceans | Apocorophium lacustre | Moderate | x | |||

| (n = 28) | Astacus astacus | Low | x | |||

| Calanipeda aquaedulcis | Moderate | x | ||||

| Chelicorophium curvispinum | Moderate | x | ||||

| Cherax destructor | Moderate | x | ||||

| Cornigerius maeoticus | Moderate | x | ||||

| Cyclops kolensis | Moderate | x | ||||

| Daphnia cristata | High | x | ||||

| Dikerogammarus haemobaphes | High | x | ||||

| Dikerogammarus villosus | High | x | ||||

| Echinogammarus warpachowskyi | Moderate | x | ||||

| Faxonius limosus | Moderate | x | ||||

| Heterocope appendiculata | Moderate | x | ||||

| Heterocope caspia | Moderate | x | ||||

| Limnomysis benedeni | High | x | ||||

| Obesogammarus crassus | High | x | ||||

| Obesogammarus obesus | High | x | ||||

| Pacifastacus leniusculus | High | x | ||||

| Paraleptastacus spinicaudus | Moderate | x | ||||

| Paraleptastacus wilsoni | Moderate | x | ||||

| Paramysis intermedia | Moderate | x | ||||

| Paramysis lacustris | Moderate | x | ||||

| Pontogammarus robustoides | Moderate | x | ||||

| Procambarus virginalis | High | x | ||||

| Pseudorasbora parva | Moderate | x | ||||

| Rhithropanopaeus harrisii | High | x | ||||

| Silurus glanis | High | x | ||||

| Sinelobus stanfordi | Moderate | x | ||||

| Other—Annelid (n = 1) | Hypania invalida | Moderate | x | |||

| Other—Bryozoan (n = 1) | Fredericella sultana | Moderate | x | |||

| Other—Mollusks | Hypanis colorata | Moderate | x | |||

| (n = 3) | Limnoperna fortunei | Moderate | x | |||

| Lithoglyphus naticoides | Moderate | x | ||||

| Other—Platyhelminthes (n = 1) | Leyogonimus polyoon | Moderate | x | |||

| Other—Rotifers | Brachionus leydigii | Moderate | x | |||

| (n = 3) | Filinia cornuta | Moderate | x | |||

| Filinia passa | Moderate | x |

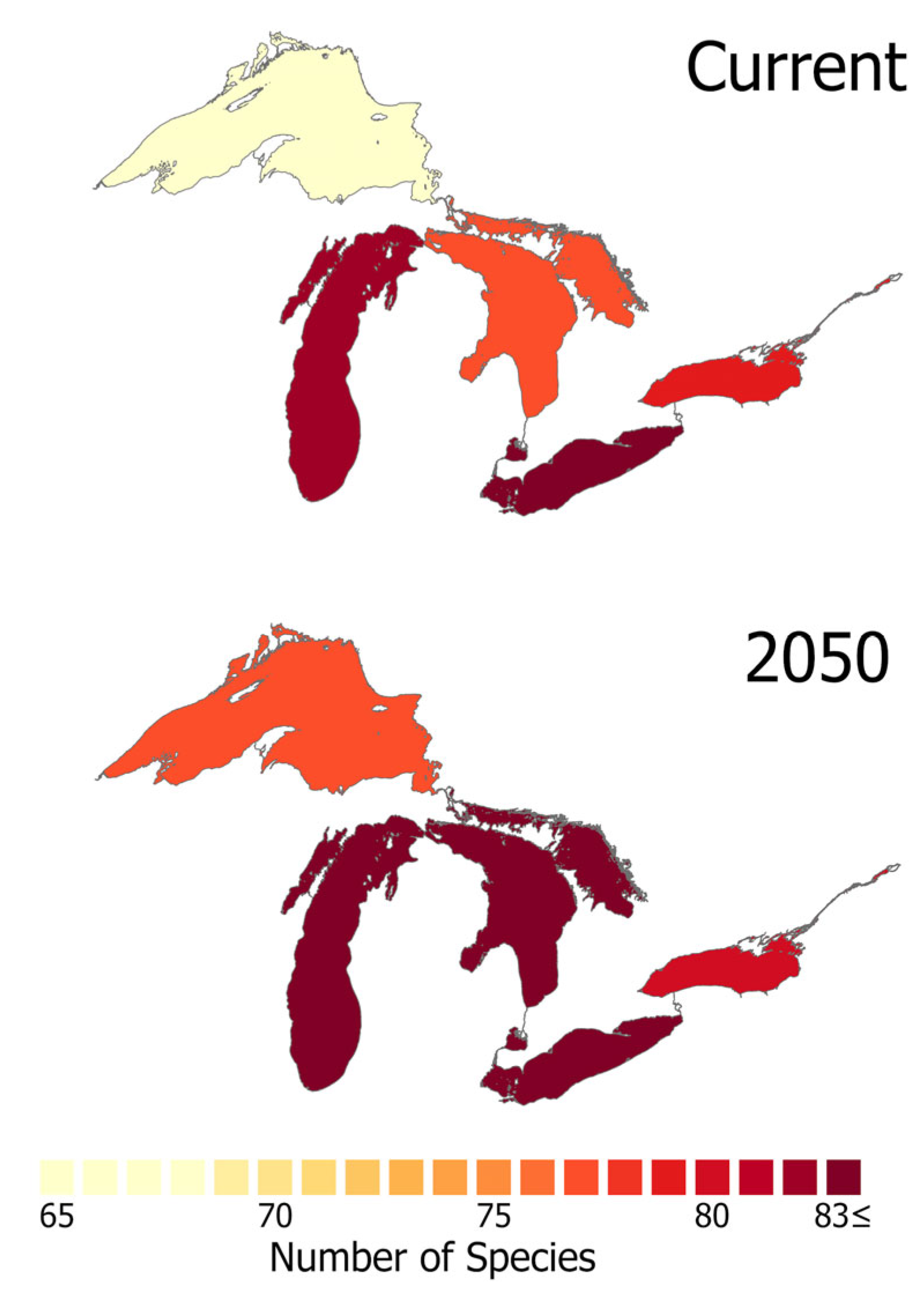

3.2. Geographic Differences in Risk

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GLANSIS | Great Lakes Aquatic Nonindigenous Species Information System |

| NOAA | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration |

| GLERL | Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory |

| USGS | United States Geological Survey |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

| GLAHF | Great Lakes Aquatic Habitat Framework |

| GLISA | Great Lakes Integrated Sciences and Assessments Center |

| NAD | North American Datum |

| NGS | National Geodetic Survey |

| WGS | World Geodetic System |

References

- Strayer, D.L. Alien species in fresh waters: Ecological effects, interactions with other stressors, and prospects for the future. Freshw. Biol. 2010, 55, 152–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simberloff, D.; Martin, J.L.; Genovesi, P.; Maris, V.; Wardle, D.A.; Aronson, J.; Curchamp, F.; Galil, B.; García-Bertou, E.; Pascal, M.; et al. Impacts of biological invasions: What’s what and the way forward. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2013, 28, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polce, C.; Cardosa, A.; Deriu, I.; Gervasini, E.; Tsiamis, K.; Vigiak, O.; Zilian, G.; Maes, J. Invasive alien species of policy concerns show widespread patterns of invasion and potential pressure across European ecosystems. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haubrock, P.; Cuthbert, R.; Ricciardi, A.; Diagne, C.; Courchanp, F. Economic costs of invasive bivalves in freshwater ecosystems. Divers. Distrib. 2022, 28, 1010–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolpagni, R. Towards global dominance of invasive alien plants in freshwater ecosystems: The dawn of the Exocene? Hydrobiologia 2021, 848, 2259–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, J. Contemporary perspectives on the ecological impacts of invasive freshwater fishes. J. Fish Biol. 2023, 103, 752–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolway, R.; Sharma, S.; Smol, J. Lakes in Hot Water: The Impacts of a Changing Climate in Aquatic Ecosystems. BioScience 2022, 72, 1050–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, K.; Bierwagen, B.; Bridgham, S.; Carlisle, D.; Hawkins, C.; Poff, N.; Read, J.; Rohr, J.; Saros, J.; Williamson, C. Indicators of the effects of climate change on freshwater ecosystems. Clim. Change 2023, 173, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capon, S.; Stewart-Koster, B.; Bunn, S. Future of freshwater ecosystems in a 1.5 °C Warmer World. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 784642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundzewicz, Z.; Mata, L.; Arnell, N.; Doll, P.; Jimenez, B.; Miller, K.; Oki, T.; Şen, Z.; Shiklomanov, I. The implications of projected climate change for freshwater resources and their management. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2008, 53, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, P.; Zhang, J. Impact of climate change on freshwater ecosystems: A global-scale analysis of ecologically relevant river flow alterations. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2010, 14, 783–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poesch, M.; Chavarie, L.; Chu, C.; Pandit, S.; Tonn, W. Climate Change Impacts on Freshwater Fishes: A Canadian Perspective. Fisheries 2016, 41, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellmann, J.; Byers, J.; Bierwagen, B.; Duk, J. Five Potential Consequences of Climate Change for Invasive Species. Conserv. Biol. 2008, 22, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kernan, M. Climate change and the impact of invasive species on aquatic ecosystems. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 2015, 18, 321–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Great Lakes Restoration Initiative (GLRI) Task Force. GLRI Action Plan FY2010-FY2014; U.S. EPA Great Lakes National Program Office: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, E.L.; Leach, J.H.; Carlton, J.T.; Secor, C.L. Exotic species in the Great Lakes: A history of biotic crises and anthropogenic introductions. J. Great Lakes Res. 1993, 19, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciardi, A. Patterns of invasion in the Laurentian Great Lakes in relation to changes in vector activity. Divers. Distrib. 2006, 12, 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturtevant, R.; Mason, D.; Rutherford, E.; Elgin, A.; Lower, E.; Martinez, F. Recent history of nonindigenous species in the Laurentian Great Lakes; An update to Mills et al., 1993 (25 years later). J. Great Lakes Res. 2019, 45, 1011–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, P.; Ye, X.; Pal, J.; Chu, P.; Kayastha, M.; Huang, C. Climate projections over the Great Lakes Region: Using two-way coupling of a regional climate model with a 3-D lake model. Geosci. Model Dev. 2022, 15, 4425–4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolway, R.; Jennings, E.; Shatwell, T.; Golub, M.; Pierson, D.; Maberly, S. Lake heatwaves under climate change. Nature 2021, 589, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, D.; Zhang, H.; Levison, J. Impacts of climate change on groundwater in the Great Lakes Basin: A review. J. Great Lakes Res. 2021, 47, 1613–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayastha, M.; Ye, X.; Huang, C.; Xue, P. Future rise of the Great Lakes water levels under climate change. J. Hydrol. 2022, 612 Pt B, 128205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolway, R.; Sharma, S.; Weyhenmeyer, G.; Debolskiy, A.; Golub, M.; Mercado-Bettin, D.; Perroud, M.; Stepanenko, V.; Tan, Z.; Grant, L.; et al. Phenological shifts in lake stratification under climate change. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozersky, T.; Bramberger, A.; Elgen, A.; Vanderploeg, H.; Wang, J.; Austin, J.; Carrick, H.; Chavarie, L.; Depew, D.; Fisk, A.; et al. The changing face of winter: Lessons and questions for the Laurentian Great Lakes. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2021, 126, e2021JG006247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theuerkauf, T.; Braun, K. Rapid water level rise drives unprecedented coastal habitat loss along the Great Lakes of North America. J. Great Lakes Res. 2021, 47, 945–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S.; Hubbard, J.; Mandrak, N. Changing community dynamics and climate alter invasion risk of freshwater fishes historically found in invasion pathways of the Laurentian Great Lakes. Divers. Distrib. 2022, 28, 1620–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindree, M. Elucidating the Interactive Effects of Climate Change and Invasive Species Using a Lotic Fish Species Pair. Ph.D. Thesis, Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, J.; Hunt, L.; Rodgers, J.; Drake, A.; Johnson, T. Assessing the Vulnerability of Ontario’s Great Lakes and Inland Lakes to Aquatic Invasive Species Under Climate Change and Human Population Change; Science and Research Branch, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiano, N.; Perry, T. Conducting secondary analysis of qualitative data: Should we, can we, and how? Qual. Soc Work 2019, 18, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevitch, J.; Curtis, P.; Jones, M. Meta-analysis in ecology. Adv. Ecol. Res. 2001, 32, 199–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA. Great Lakes Aquatic Nonindigenous Species Information System (GLANSIS). Available online: https://www.glerl.noaa.gov/glansis/ (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Fusaro, A.; Baker, E.; Conard, W.; Davidson, A.; Dettloff, K.; Li, J.; Núñez-Mir, G.; Sturtevant, R.; Rutherford, E. A Risk Assessment of Potential Great Lakes Aquatic Invaders; NOAA Technical Memorandum GLERL-169; United States Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; 1640p. [Google Scholar]

- Lower, E.; Boucher, N.; Alsip, P.; Davidson, A.; Sturtevant, R. 2018 Update to “A Risk Assessment of Potential Great Lakes Aquatic Invaders.”; NOAA Technical Memorandum GLERL-169b; United States Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; 266p. [Google Scholar]

- Lower, E.; Boucher, N.; Davidson, A.; Elgin, A.; Sturtevant, R. 2019 Update to “A Risk Assessment of Potential Great Lakes Aquatic Invaders.”; NOAA Technical Memorandum GLERL-169c; United States Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; 179p. [Google Scholar]

- Lower, E.; Bartos, A.; Sturtevant, R.; Elgin, A. 2020 Update to “A Risk Assessment of Potential Great Lakes Lakes Aqautic Invaders.”; NOAA Technical Memorandum GLERL-169d; United States Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; 152p. [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant, R.; Lower, E.; Bartos, A.; Johnson, A.; Cameron, C.; Rose, D.; Redinger, J.; Shelly, C.; Van Zeghbroek, J.; Mason, D.; et al. 2021–2023 Updates to GLANSIS Assessments; NOAA Technical Memorandum GLERL-180; United States Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; 79p. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, A.; Fusaro, A.; Sturtevant, R.; Kashian, D. Development of a risk assessment framework to predict invasive species establishment for multiple taxonomic groups and vectors of introduction. Manag. Biol. Invasions 2017, 8, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumpickas, J.; Shuter, B.J.; Minns, C.K. Forecasting impacts of climate changes on Great Lakes surface water temperatures. J. Great Lakes Res. 2009, 35, 454–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayhoe, K.; VanDorn, J.; Corley, T., II; Schlegel, N.; Wuebbles, D. Regional climate change projections for Chicago and the US Great Lakes. J. Great Lakes Res. 2010, 36, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumpickas, J.; Shuter, B.; Minns, C.; Cyr, H. Characterizing patterns of nearshore water temperature variation in the North American Great Lakes and assessing sensitivities to climate change. J. Great Lakes Res. 2015, 41, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, K.; Tokos, K.; Rippke, J. Climate projection of Lake Superior under a future warming scenario. J. Limnol. 2019, 78, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuebbles, D.; Fahey, D.; Hibbard, K.; Dokken, D.; Stewart, B.; Maycock, T. Climate Science Special Report: Fourth National Climate Assessment; U.S. Global Change Research Program: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Toffolon, M.; Piccolroaz, S.; Calamita, E. On the use of averaged indicators to assess lakes’ thermal response to changes in climatic conditions. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 034060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Bai, X.; Hu, H.; Clites, A.; Colton, M.; Lofgren, B. Temporal and spatial variability of Great Lakes ice cover, 1973–2010. J. Clim. 2012, 25, 1318–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, L.A.; Riseng, C.; Gronewold, A.; Rutherford, E.; Wang, J.; Clites, A.; Smith, S.; McIntyre, P. Fine-scale spatial variation in ice cover and surface temperature trends across the surface of the Laurentian Great Lakes. Clim. Change 2016, 138, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Hein-Griggs, D.; Barr, L.; Ciborowski, J. Projected extreme temperature and precipitation of the Laurentian Great Lakes basin. Glob. Planet. Change 2019, 172, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northern IN National Weather Service. Fall Frost and Freeze Information for the Northern Indiana Forecast Area; US Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA; NOAA: Washington, DC, USA; National Weather Service: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hayhoe, K.; Sheridan, S.; Kalkstein, L.; Greene, S. Climate change, heat waves and mortality projections for Chicago. J. Great Lakes Res. 2010, 36, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturtevant, R.; Lower, E.; Boucher, N.; Bartos, A.; Mason, D.; Rutherford, E.; Martinez, F.; Elgin, A. A Gap Analysis of the State of Knowledge of Great Lakes Nonindigenous Species; NOAA Technical Memorandum GLERL-176; United States Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.glerl.noaa.gov/pubs/tech_reports/glerl-176/tm-176.pdf (accessed on 20 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Daloğlu, I.; Kyung, C.H.; Scavia, D. Evaluating causes of trends in long-term dissolved reactive phosphorus loads to Lake Erie. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 10660–10666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hanson, E.; Shelly, C.; Sturtevant, R. A Secondary Analysis of Invasion Risk in the Context of an Altered Thermal Regime in the Great Lakes. Diversity 2025, 17, 861. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120861

Hanson E, Shelly C, Sturtevant R. A Secondary Analysis of Invasion Risk in the Context of an Altered Thermal Regime in the Great Lakes. Diversity. 2025; 17(12):861. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120861

Chicago/Turabian StyleHanson, Elias, Connor Shelly, and Rochelle Sturtevant. 2025. "A Secondary Analysis of Invasion Risk in the Context of an Altered Thermal Regime in the Great Lakes" Diversity 17, no. 12: 861. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120861

APA StyleHanson, E., Shelly, C., & Sturtevant, R. (2025). A Secondary Analysis of Invasion Risk in the Context of an Altered Thermal Regime in the Great Lakes. Diversity, 17(12), 861. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120861