Abstract

Octacnemid ascidians inhabit the deep-sea and have evolved traits that facilitate the consumption of large prey (macrophagy). The deep ocean is difficult to sample, but with the combined efforts of several research cruises, supplemented by submersibles, a series of octacnemid specimens were acquired and appropriately subsampled for molecular and morphological analyses. Ascidian molecular phylogenies to date have included only a single species from the family Megalodicopia hians. This study presents the first molecular phylogenetic analyses within Octacnemidae, with 13 species represented, as well as attempts to resolve its position within Phlebobranchia. Previous phylogenies suggested a sister-group relationship between Octacnemidae and Corellidae. Our results further support their close relationship, though they were found to be non-monophyletic. One new genus and seven new species of Octacnemidae are formally described here, supported by molecular and morphological evidence. The new species are from deep sea, off California, Chile, and Western Australia.

1. Introduction

Tunicata (Urochordata) is part of Chordata and forms the sister group to Vertebrata [1]. Tunicates have both pelagic and benthic representatives and inhabit most latitudes and depths of the world’s oceans [2,3]. Pelagic tunicates include the tadpole-like Appendicularia and the Thaliacea (salps, doliolids, and pyrosomes). The benthic Ascidiacea, colloquially termed “sea squirts”, have an unclear phylogenetic status, with the most recent consensus being that they are paraphyletic [4,5], but the taxon name will be used here. Tunicates are the only animals that can synthesize cellulose to form a superficial protective layer: the tunic [6].

Most tunicates, including ascidians, employ a suspension feeding strategy. This feeding strategy is possible due to the following several key structures among the ascidians: a sieve-like branchial sac (pharyngeal basket), ciliated stigmata that generate a water current, and an endostyle that produces a mucus net. Ascidians generate a water current with their ciliary beating. This ciliary motion at low Reynolds numbers draws water into their oral siphon filling the branchial sac. The branchial sac’s interior is lined with mucus produced by the endostyle, facilitating capture of planktic organisms. The captured food is ultimately brought down to their gut and expelled as waste from a separate atrial siphon [7].

The World Register of Marine Species currently accepts 2993 valid species of ascidians [8]. Most of these live by filtering the plankton in the photic zone, with its relatively high amount of planktic biomass. Planktic density and biomass change dramatically with depth. Some records indicate that at a depth of 1000 m, there is 1% of the planktic biomass compared to the surface waters. At even greater depths of 5000 m, this biomass is around 0.1% [9], thus presenting a challenge for filter-feeding organisms to live at such depths.

Ascidians are classically organized in the following two different ways: gonad placement or branchial sac structure. Gonad location is used for the superorders Enterogona and Pleurogona, with the gonads located in/below the gut loop or on the body wall, respectively. The branchial sac organization is used for the suborders Stolidobranchia, Aplousobranchia, and Phlebobranchia. Phlebobranchia (part of Enterogona) have unfolded branchial sacs with longitudinal vessels and include both colonial and solitary forms [10,11]. Phlebobranchia include some of the most extensively studied tunicates, such as Ciona intestinalis Linnaeus, 1767, a model organism for chordate evo-devo studies [12,13,14], as well as Phallusia mammillata and other species that accumulate and store high concentrations of vanadium in their blood cells, an ability that distinguishes them from the Stolidobranchia and some Aplousobranchia [15,16]. Phlebobranchia also include some of the lesser studied tunicates, including Octacnemidae Herdman, 1888, which have remained elusive owing to the difficulties of sampling these fragile gelatinous animals from the deep sea.

Members of Octacnemidae are characterized by anatomical features that facilitate a macrophagous feeding strategy. Octacnemidae show a range of specialization of their oral siphons, which are often hypertrophied, aiding the capture of large prey (e.g., polychaetes and crustaceans). There are large variations in the reduction in the branchial sac and unciliated stigmata, modifications that suggest the taxa differ in their dependence of macrophagy. This morphological diversity has been divided into three informal groups by Sanamyan [17]. Group one octacnemids include the type genus Octacnemus Moseley, 1876, and the colonial Polyoctacnemus Ihle, 1935 [17,18], and are distinguished by their eight enlarged oral siphon lobes. Group two octacnemids include Megalodicopia Oka, 1918, Dicopia Sluiter, 1905, Kaikoja Monniot C., 1998, Situla Vinogradova, 1969, and Benthascidia Ritter, 1907 [17]. These octacnemids are often pedunculate with enlarged oral siphons typically arranged as “lips”. Muscular development among these oral siphons varies, with Kaikoja and Benthascdia lacking radial muscles [19,20]. Pronounced anterior development of the oral siphon from the pericoronal band is found in Megalodicopia and Dicopia [17]. Group two octacnemids inhabit a large depth range, with Megalodicopia having the most shallow octacnemid (M. hians 365 m) and Situla with the deepest octacnemid (S. pelliculosa ~8400 m) [21,22]. Group three octacnemids–Myopegma Monniot & Monniot, 2011, Cryptia Monniot & Monniot 1985, and Cibacapsa Monniot & Monniot, 1983–have reduced or absent branchial sacs and are also lacking an endostyle [17,23,24,25]. It should be noted that reductions in stigmata are not exclusive to Octacnemidae. Xenobranchion Ärnbäck, 1950, and Clatripes Monniot & Monniot, 1976, of the phlebobranch family Corellidae Lahille, 1888, have irregular stigmata and absent stigmata, respectively [17,26,27]. Previous phylogenetic inferences have placed octacnemids as a sister group to Corellidae [28,29,30].

For this study, submersibles have facilitated the acquisition of largely undamaged octacnemid specimens from the Indian Ocean, Southern Ocean, and eastern Pacific Ocean. Furthermore, these specimens had tissues subsampled in ethanol allowing for subsequent DNA sequencing and phylogenetic inference. To improve our understanding of Octacnemidae and its relationship to Corellidae, we present the first molecular phylogeny focused on Octacnemidae. This phylogeny is used as molecular evidence in conjunction with morphological and geographical evidence to describe one new genus and seven new species of Octacnemidae.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimen Collection

Octacnemid specimens from the Cape Range Canyon, Western Australia, were collected via the ROV SuBastian and the R/V Falkor on cruise FK200308 (2020). A specimen from Costa Rica was collected via the ROV SuBastian and the R/V Falkor on cruise FK190106 (2019). Specimens from California, USA, were collected by ROV Tiburon and R/V Western Flyer (2007), ROV Doc Ricketts and R/V Western Flyer (2010), ROV Hercules and E/V Nautilus on cruise NA213 (2020), ROV Hercules, and E/V Nautilus on cruise NA213 (2020), and by ROV SuBastian and R/V Falkor on cruise FK210726 (2021). A specimen from Discovery Bank, Antarctica, was collected by R/V Nathaniel Palmer via Blake trawl on cruise NBP11-05 (2011). Specimens from Chile were collected by ROV SuBastian and R/V Falkor(too) on cruises FKt240108, FKt240708 and FKt241011 (2024).

2.2. Specimen Fates and Morphology

Most specimens were placed in cold sea water and relaxed with 7% magnesium chloride and photographed live with a digital camera (Canon). Tissue subsamples were primarily dissected from gonads and, occasionally, body tissue in anticipation of molecular work and were preserved in 95% ethanol. Whole specimens were either stored in 75% (Cape Range Canyon specimens) or 95% ethanol, while morphology voucher specimens were preserved in 10% formalin in seawater. Microscopy photographs were taken on a stereomicroscope (Leica MZ9.5 or MZ12.5, Wetzlar, Germany) with a digital camera (Canon EOS M6, Rebel T6i or Rebel T7i, Tokyo, Japan). Specimens were post-stained with either ShirlastainA© (SDL Atlas sdlatlas.com, Rock Hill, SC, USA) or hematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Gut contents were viewed on Leica DMR interference contrast microscope and photographed with a Canon EOS Rebel T6i camera. Specimen locality and location of voucher and type material is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

GenBank or BOLD (some Corellidae) accession numbers and catalog numbers of specimens used for the phylogeny in Figure 1. New data are in bold. Other new sequence numbers are listed under the relevant taxonomic description. Specimens used in this study are deposited in Scripps Institution of Oceanography, Benthic Invertebrate Collection (SIO-BIC), La Jolla, CA, USA; Universidad de Costa Rica (MZUCR), San Jose, Costa Rica; Museo Nacional de Historia Natural Chile (MNHNC); Sala de Colecciones Biológicas Universidad Católica del Norte (SCBUCN); and Western Australia Museum (WAM), Perth, Australia. Abbreviations for other institutions listed below are Florida Museum National History (FMNH), Museum national d’Histoire naturelle (MNHN), University Museum of Bergen (ZMBN).

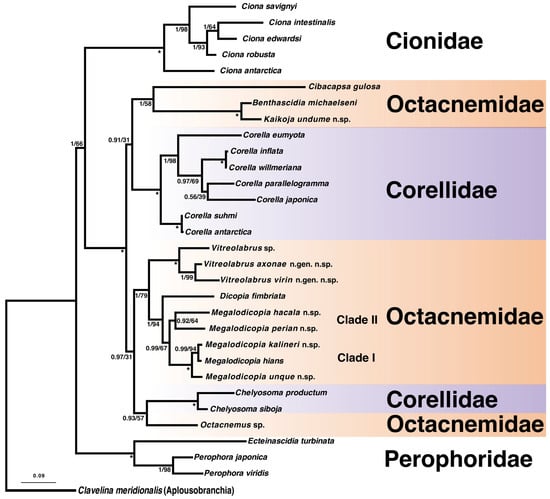

Figure 1.

Maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree inferred from the concatenated dataset of mitochondrial (COI) and nuclear (18S and H3) genes. The Bayesian analysis produced the same topology. New sequences are in bold. Posterior probabilities are indicated first at nodes, followed by bootstrap scores. Scores of 1/100 are represented by an asterisk.

2.3. Molecular Data

Tissue subsample DNA were extracted with the Zymo Research DNA-Tissue Mini- and Microprep kit following the manufacturer’s protocol. Mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit I (COI) was sequenced first for identification and species delimitation. Nuclear 18S rRNA (18S) and Histone H3 (H3) were sequenced to provide loci for better phylogenetic inference. DNA was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with 12.5 µL Apex 2.0× Taq DNA Polymerase, 1 µL each of the forward and reverse primers for each gene, 8.5 µL of water, and 2 µL of DNA. COI primers LCO1490 and HCO2198 were primarily used for COI amplification [43]. COI primers AscCOI-F and AscCOI-R were used on one older specimen with very fragmented DNA [44]. H3 primers H3F and H3R were used for amplification [45]. 18S was amplified with the following three pairs of overlapping primers: 18S1F and 18S5R, 18S3F and 18SBi, and 18SA2 and 18S9R [46]. Agarose gel electrophoresis in conjunction with ethidium bromide was used as a preliminary assessment of successful PCR amplification. Excess primers and deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs) were removed from the PCR product with ExoSAP-IT [47]. Cleaned PCR products were sent to Eurofins Genomics (Louisville, KY, USA) for Sanger sequencing. Identifying and resolving sequence ambiguities and sequence trimming was performed in Geneious Prime 2023.0.4 [48]. The GenBank or BOLD accession numbers used for the phylogenetic analysis can be found in Table 1, with additional newly generated sequences listed in relevant material examined sections for the new species.

2.4. Molecular Data Analysis

GenBank sequences of Clavelina meridionalis (Table 1) were used as an outgroup representing Aplousobranchia based upon the inferred relationship between Aplousobranchia and Phlebobranchia in previous literature [5,30,34]. To assist in assessing the monophyly and placement of Octacnemidae, we also included other taxa from Phlebobranchia with available data (Corellidae, Cionidae, and Perophoridae). Previous phylogenetic inference have placed Corellidae and Octacnemidae as sister groups, albeit with limited sampling [28]. Historically, certain genera within Octacnemidae (group two) were argued to be closest to Cionidae or Corellidae based on morphological taxonomy [21,49,50,51]. Sequences were input into Mesquite v.3.81 [52] and aligned using MAFTT G-INS-i [53]. COI uncorrected pairwise distances were calculated in Mesquite. Loci (COI, H3, 18S) were aligned separately. Aligned gene partitions were analyzed using RaxML-NG v.1.2.2 [54,55] after concatenation using RAxML GUI v2.0.10 [56]. Optimal models were selected for each partition using ModelTest-NG v.0.1.7 [57], with TVM + I + G applied to CO., TN93 + G for H3, and TN93 + I + G for 18S. The maximum likelihood (ML) tree was inferred with 100 separate runs, and node support was evaluated by 1000 bootstrap replications. Visualizing and editing the phylogeny was conducted using FigTree 1.4.4 [58]. Haplotype networks of COI were made using PopArt v.1.7 [59] and the TCS algorithm [60]. A Bayesian phylogenetic analysis was also performed on the concatenated data using MrBayes v.3.2.7a [61]. Since this program uses a smaller set of models that RAxML the settings for ModelTest-NG were adjusted to find the appropriate model for each partition. These were GTR + I + G for COI and 18S and GTR + G for H3. Four Markov chair Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains were run for 50 million generations run twice with sampling every thousand generation. The likelihood scores of the combined runs were assessed with Tracer v.1.7.1 [62] for convergence and to allow for burn-in, which was set at 10%. A majority rule consensus tree was then made from the remaining trees.

3. Results

3.1. Phylogeny

Both phylogenetic analyses recovered the same topologies, with the Bayesian support values consistently higher than the maximum likelihood bootstrap scores with posterior probabilities above 0.9 for all key nodes. The maximum likelihood result is shown in Figure 1. Octacnemidae and Corellidae formed a well-supported clade with posterior probability (PP) of 1 and bootstrap (BS) of 100; however, each taxon was not monophyletic. Perophoridae and Cionidae were each recovered as monophyletic with strong support (PP = 1, BS = 100), with Cionidae as the sister group to the Octacnemidae/Corellidae clade.

Octacnemidae was recovered in three different clades. Octacnemus sp., part of type genus of Octacnemidae, was recovered closest to the corellid genus Chelyosoma, though with varying support (PP = 1, BS = 57). Four new Megalodicopia species are described here, and they formed a clade with the type species M. hians (PP = 0.99, BS = 67). Within Megalodicopia, we show two main clades in Figure 1. Clade I was strongly supported (PP = 1, BS = 100) and includes M. hians and two of the new species. Clade II, with the other two new species–Megalodicopia perian n. sp. and Megalodicopia hacala n. sp.–had weaker support (PP = 0.92 BS = 64). Megalodicopia and Dicopia were recovered as sister taxa with high support (PP = 1, BS = 94). Megalodicopia, Dicopia, and Vitreolabrus n. gen. formed a clade with good support (PP = 1, BS = 79). Vitreolabrus n. gen. was monophyletic with strong support (PP = 1, BS = 100), including two newly described species–Vitreolabrus axonae n. gen. n. sp. and Vitreolabrus virin n. gen. n. sp.–and one undescribed species. Cibacapsa and Benthascidia formed a clade along with the newly described Kaikoja undume n. sp. (PP = 1, BS = 58), and this octacnemid clade was the sister group to most of the Corellidae terminals included here (Figure 1). Benthascidia and Kaikoja were recovered as sister taxa with strong support (PP = 1, BS = 100).

3.2. Haplotype Networks

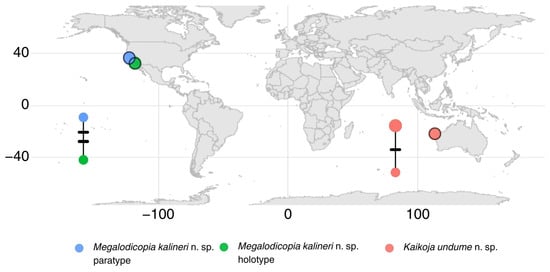

The Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. holotype and one paratype, from San Clemente Escarpment, USA, and Monterey, USA, respectively, showed haplotypes differentiated by two base pairs over a short segment of COI (Figure 2), representing a pairwise distance of just over 1%. The Kaikoja undume n. sp. holotype and two paratypes, both from Cape Range Canyon, Australia, showed haplotypes differentiated by a single base pair (Figure 2). The haplotype network is positioned over a world map with the sampled localities of specimens indicated by colored circles.

Figure 2.

TCS haplotype network for COI from three Kaikoja undume n. sp. and two Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. placed on a world map showing the sampling localities for each specimen.

3.3. COI Distances

The minimum uncorrected pairwise distances for COI in Megalodicopia are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The minimum uncorrected pairwise distances for COI in Megalodicopia, excluding Megalodicopia rineharti, for which there are no data.

Clade II members Megalodicopia hacala n. sp. and Megalodicopia perian n. sp. showed a distance ranging from 16.29% to 19.96% from Clade I members. Within Clade II, Megalodicopia hacala n. sp. and Megalodicopia perian n. sp. had a similar distance from each other at 18.38%. Distances within Clade I were shorter, ranging from 4.69% to 10.08%. The closest distance can be observed between the type species Megalodicopia hians and Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. at 4.69% which are geographically distant from the Sea of Japan, northwest Pacific Ocean, to off California, northeast Pacific Ocean, respectively. Megalodicopia hians and Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. also differ in recorded depths at 365 m and 1771–2893 m, respectively. The minimum uncorrected pairwise distances for COI in Vitreolabrus n. gen. are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

The minimum uncorrected pairwise distances for COI in Vitreolabrus n. gen. including one undescribed specimen, Vitreolabrus n. gen. sp., from Costa Rica.

The Vitreolabrus n. gen. clade (Figure 1) showed similar COI distances as seen in Megalodicopia (Table 2). The two newly described Vitreolabrus axonae n. gen. n. sp. and Vitreolabrus virin n. gen. n. sp. showed a 14.18% COI divergence while geographically distant at Cape Range Canyon, Indian Ocean to Canyon de Magallanes, eastern Pacific Ocean, respectively. Vitreolabrus n. gen. sp. from Seamount 5.5, eastern Pacific, Costa Rica, is most divergent from its congeneric members, ranging from 21.22–23.28% (Figure 1).

3.4. Taxonomy

- Family OCTACNEMIDAE Herdman 1888

- Diagnosis (from Monniot 1972 [49])

All the genera have in common the following: a tunic that is generally very thin and very soft, sometimes showing nodular thickenings; a branchial sac lacking recognizable longitudinal and transverse sinuses, with stigmata that are not elongated and lack ciliation; a massive digestive tube forming a closed loop, located on the ventral side of the body; unbranched gonads situated within the intestinal loop; a mantle that is often thick but very fragile and vacuolated, and difficult to distinguish from the tunic; a reduction in the cloacal cavity; finally, a tendency toward a considerable development of the oral siphon—more precisely, of the space, very narrow in other ascidians, located between the limit of the reflected tunic and the pericoronal groove.

- Remarks

The above is the most recent diagnosis of Octacnemidae, dating back to 1972 [49] and will need to be updated once the delineation of Octacnemidae is resolved. As Figure 1 shows the family is currently not monophyletic and may be restricted or expanded in membership with more taxon sampling and a more robust phylogenetic result (see Section 4 in Discussion).

3.4.1. Megalodicopia

- Type species: Megalodicopia hians Oka, 1918

- Diagnosis (emended)

Gelatinous tunic, smooth or wrinkled, translucent. Oral siphon bi-lobed (dorsal and ventral), anteriorly developed from pericoronal band, variable dorsal development, circular and radial muscles present. Atrial siphon reduced, simple or six lobes, dorsal position, circular and radial muscles present. Peduncle variable length, anterior longitudinal muscles extend dorsal, bifurcate near endostyle, limited transition into trunk, rhizoids absent. Oral tentacles proximally thin, distally wide, flat, variable size and shape, larger tentacles concentrated ventral and dorsal, ampullae uncommon. Branchial sac posterior, shallow bowl, stigmata concentrated anterior to gut–gonad complex. Stigmata unciliated, irregular, oval to polygonal, often clustered. Dorsal ganglion white, tear-drop shaped; undulating white nerves radiate. Endostyle conspicuous white/cream groove, anteriorly tapered, bisects ventral third of branchial sac, projects posteriorly through branchial tissue in branchial pit, does not reach esophagus. Retropharyngeal groove similar color to branchial sac, bisects branchial sac between branchial pit and esophagus. U-shaped gut loop posterior to branchial sac. Esophagus general disc shape, asymmetric right side (larger), dorsal and right in branchial sac, translucent funnel projects posterior and ventral to stomach, tentacles absent. Stomach ovoid, orange in life, variable size, wider than intestines, right side, extends ventral then leftward to intestines. Intestines flattened tube, orange/red in life, left side, extends dorsally and medially, terminating at anus. Anus variable lobes, variable projection. Gonads nested within gut loop, bright white, ovaries dorsal with spherical eggs, acinar testes ventral and posteriorly attached to ovaries, gonoducts short. Heart posterior and right of gut–gonad complex, dorso-ventral direction, thin transparent pericardium, translucent helical myocardium.

- Remarks

Until this study Megalodicopia contained two accepted species, the type species M. hians and M. rineharti Monniot C. & Monniot F. 1989. The original description of M. hians did not include a diagnosis for the genus [22]. Subsequent redescriptions or descriptions were specific to M. hians and M. rineharti and not pertaining to the genus as a whole [63,64]. Megalodicopia has been compared to other genera (often Dicopia, Situla, and Benthascidia) in previous literature remarks. These comparisons summarized features of the genus, though not in a formal diagnosis [17,19,49,51,65,66]. The phylogenetic results here show two clades of Megalodicopia that also differ morphologically in their exterior morphology and size (Figure 1). The emended diagnosis for Megalodicopia accounts for the reported variations in both Clade I and Clade II. The general external morphological differences between Clade I and Clade II Megalodicopia are summarized in Table 4. Sequence data are missing for M. rineharti, which shows features of Clade I and II, but on balance seems to be part of Clade II (see Section 4).

Table 4.

External morphological features and depth, distinguishing the two Megalodicopia clades in Figure 1.

3.4.2. Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp.

- Material examined

Holotype. SIO-BIC BI1656, USA, off California, San Clemente Escarpment, Pacific Ocean (32.6745 N; −118.1312 W), 4 November 2020, 1771 m, coll. G. Rouse & K. Pearson, E/V Nautilus/ROV Hercules, dive H1846, fixed in 10% formalin, 100% ethanol subsample, attached to rock. GenBank COI sequence PX138915, 18S sequence PX241556, and H3 sequence PX577540.

Paratype. SIO-BIC As382, USA, off California, Monterey canyon system, Pacific Ocean (36.613213, −122.43575), 28 October 2010, 2893 m, coll. G. Rouse, F. Pleijel, B. Vrijenhoek, R/V Western Flyer & ROV Doc Ricketts dive 208, fixed in 2% formalin in seawater and preserved in 50% ethanol, 100% ethanol subsample, GenBank COI sequence PX658852, and H3 sequence PX577551.

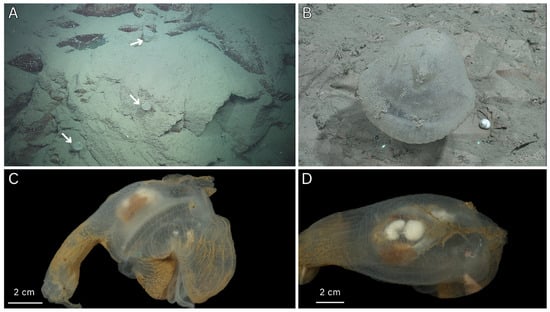

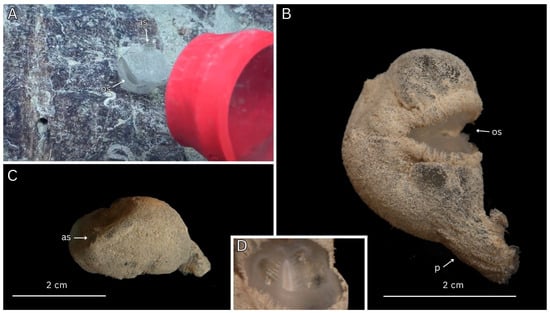

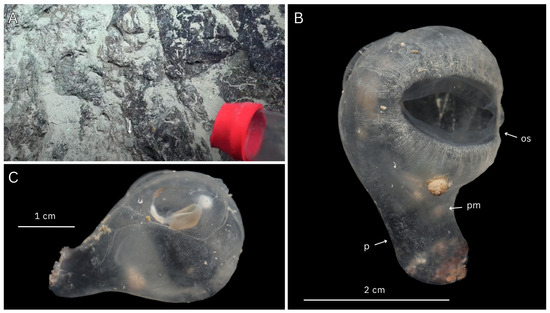

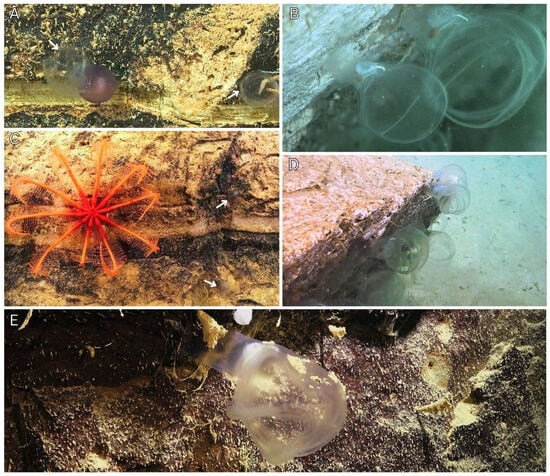

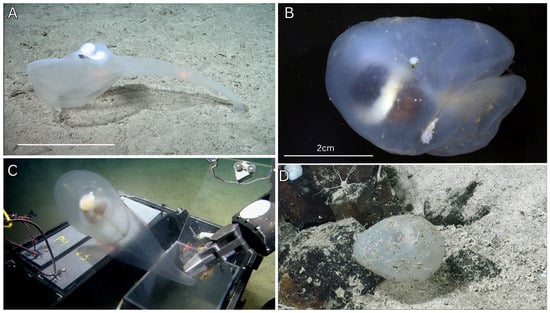

Figure 3.

ROV images of Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. in situ: (A) holotype (SIO-BIC BI1656) left view of live specimen on rocky substrate (arrow), San Clemente Escarpment, California, USA, depth 1778 m; (B) holotype, posterior view; (C) Paratype (SIO-BIC As382) right posterior view of live specimen on rocky substrate, Monterey Canyon, California, USA, depth 2893 m. (A,B) Courtesy of Ocean Exploration Trust; (C) courtesy of Monterey Bay Aquarium and Research Institute.

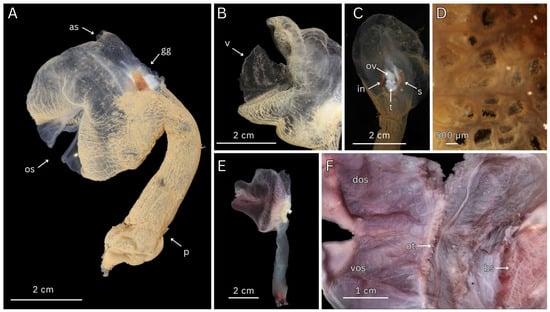

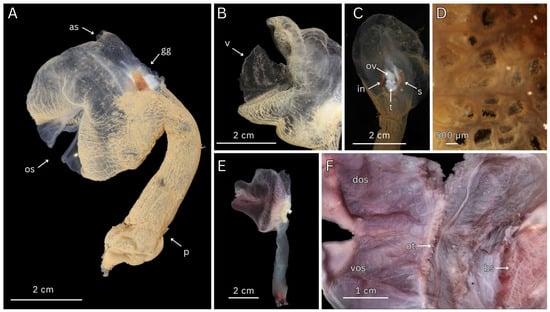

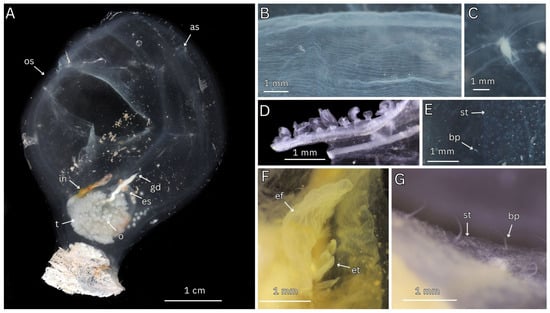

Figure 4.

Fresh and preserved photos of Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. holotype (SIO-BIC BI1656) and paratype (SIO-BIC As382). (A) Holotype, fresh whole animal, left side. (B) Holotype, preserved, oral siphon and ventral tunic velum, left side. (C) Holotype, fresh, gut–gonad complex, posterior view. (D) Paratype, preserved, branchial tissue and stigmata. (E) Holotype preserved and tunic removed, ShirlastainA applied, left view with peduncle muscles visible. (F) Paratype, midsagittal dissection of trunk showing internal regions of the oral cavity and branchial sac (right side), from left (anterior) to right (posterior) are the oral siphon margins with fringed texture, thick wrinkled oral cavity, oral tentacles, peripharyngeal band, branchial sac. Labels: os—oral siphon, as—atrial siphon, gg—gut–gonad complex, p—peduncle, v—velum, ov—ovaries, s—stomach, in—intestines, t—testes, dos—dorsal oral siphon lobe, vos—ventral oral siphon lobe, ot—oral tentacles, bs—branchial sac.

- Diagnosis (italicized text indicates unique, possibly apomorphic, features)

Tunic soft, gelatinous, transparent. Oral siphon with radial wrinkles; peduncle with longitudinal wrinkles. Ventral oral lobe with tunic velum. Oral siphon visceral tissue reflex, fringed anteriorly; oral cavity smooth. Atrial siphon with six superior lobes; fine circular muscles present, few radial muscles on lower half. Peduncle cylindrical, rhizoids absent; anterior longitudinal muscles present on upper half. Peduncle muscles bifurcate near endostyle, anastomose. Oral tentacles proximally thin, distally wide, flat, foliaceous; ampullae absent; largest and most concentrated ventral and dorsal, forming line proximal to peripharyngeal band. Endostyle prominent groove; whitish cream transitioning to translucent at branchial sac; transitions posteriorly to ventral stomach. Esophagus translucent, disc-shaped, mid-dorsal; thick on right side, tentacles absent. Branchial sac posterior, thin shallow bowl, perforated zone superimposed over gut–gonad complex; several prominent longitudinal vessels. Stigmata irregular, large, individually polygonal; usually in quadruplet polygonal clusters divided by branchial tissue; cilia absent. Anus lobes absent, reflexive. Gonoducts not obvious. Ovaries nested in gut loop; testes concentrated ventral-posterior to ovarian surface.

- Description

Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. is a pedunculate octacnemid with two hypertrophied oral siphon lobes resembling ‘lips’, belonging to Megalodicopia Clade I (Figure 1). The tunic is soft, gelatinous and mostly transparent, with radial wrinkles on the oral siphon lip margins and longitudinal wrinkles on the peduncle (Figure 4A). Most of the visceral body is transparent, with a more translucent opacity in the oral siphon margin and peduncle tissue, conspicuous features are the white endostyle, whitish branchial sac, bright white gonads, and orange gut–loop (Figure 4A,C,E).

Holotype length, measured from the peduncle base to the atrial siphon tip, is 8.4 cm. The peduncle projects ventrally, slightly longer than the body. The visceral peduncle forms a column or cord within the wider peduncle tunic, with a longitudinal muscle band on the anterior upper half (Figure 4E). The peduncle muscles continue dorsally into the body, bifurcating near the anterior tip of the endostyle toward the left and right, then anastomosing shortly (Figure 4E). No rhizoids are present at its base (Figure 4A).

The oral siphon develops anteriorly from the peripharyngeal muscle band, with well-developed musculature consisting of both circular and radial muscles (Figure 4E,F). The more prominent circular muscles increase in density at the anterior end of the oral siphon (Figure 4E). Both radial and circular muscles converge posterior to the lip corners. The ventral (lower) lip bears a fragile, thin, transparent velum projecting from the tunic, large enough to obstruct the oral cavity and fringed at its border (Figure 4B). The oral siphon margin is more translucent, resembling a beak, and consists of visceral tissue that reflexes back (Figure 4A,E,F). The translucent visceral lip margin is not covered by the tunic (Figure 4A). Internally, this margin has a fringed appearance, with a rougher texture beginning at the reflexed tissue (Figure 4E). Posterior to this region, the large oral cavity is smooth, with several radial shallow furrows (Figure 4F).

The six-lobed atrial siphon is positioned dorso-posteriorly at the top of the body (Figure 4A). It is considerably less developed than the oral siphon but possesses both circular and radial muscles (Figure 4E). The circular muscles increase in density at the distal end, while sparse radial muscles are restricted to the proximal half (Figure 4E). Anterior to the atrial siphon and posterior to the peripharyngeal muscle band lies the white, tear-drop-shaped neural ganglion. The neural ganglion is widest anteriorly, with white undulating nerves radiating outward, the most prominent originating from the left and right anterior ends. Inconspicuous neural duct and dorsal tubercle.

The oral cavity constricts at the peripharyngeal muscle band, which lies superficial to the oral tentacle line, forming a complete circle that divides the body between the muscular oral siphons and the branchial sac (Figure 4F). Oral tentacles are more developed and concentrated at the ventral and dorsal sides. Two sizes (~1 mm and ~1.6 mm), proximally thin and widening distally while remaining equally thin throughout, overlap. They are foliaceous or fan-like in appearance and lack proximal ampullae. The oral tentacle line is positioned anteriorly, closest to the peripharyngeal band at the left and right sides (Figure 4F).

The peripharyngeal band is raised, smooth, forming a complete circle with no dorsal lamina, meeting the endostyle ventrally (Figure 4F). The peripharyngeal band is furthest from the oral tentacle line dorsally. The whitish cream endostyle tapers anteriorly, beginning near the ventral oral tentacles and continuing dorso-posteriorly bisecting the branchial sac before transitioning posteriorly through the branchial sac towards the stomach, forming a pit. Dorsal to this pit, the retropharyngeal groove continues bisecting the branchial sac, terminating at the esophagus. The esophagus is a translucent disc, centrally located in the branchial sac’s perforated zone, skewed to the right, lacking tentacles.

The branchial sac forms a posterior shallow bowl, with a non-perforated zone transitioning quickly into the perforated zone, which is concentrated anteriorly (superimposed) over the gut–gonad complex (Figure 4D,F). The unciliated stigmata are irregular, large, and polygonal, often rectangular (Figure 4E). Stigmata are commonly arranged in quadruplets, bordered by polygonal branchial tissue and vessels, with these borders being translucent and visible externally (Figure 4D,E). The stigmata quadruplets are concentrated anterior to the gut–gonad complex and ventral, with sparse, non-quadruplet stigmata continuing dorsally. Branchial sac has several prominent longitudinal vessels.

The gut–gonad complex is typical of Megalodicopia, with the esophagus leading into a right-sided stomach, which forms a U-shaped gut loop posterior to the branchial sac (Figure 4C). The stomach descends ventrally, transitions left into the intestines, and ascends dorsally, terminating at the anus, which lacks lobes and is slightly reflexive (Figure 4C). The stomach is wider than the intestines and may have internal plications (Figure 4C). In life, both the stomach and intestines were reddish-orange (food content?), with intestines brighter orange due to a more transparent membrane (Figure 4A). Bright white gonads nested within the gut loop (Figure 4A,C). The larger ovaries form a compact mass on the dorsal half of the gut loop, while the testes form a less compact acinar network attached to the ventral side of the ovaries (Figure 4C). Gonoducts are not obvious.

- Variation

The paratype was sampled from greater depth of 2893 m than the 1771 m for the holotype and differed by two bases in the overlapping region of COI that was obtained (only 150 bases = 1.33%) (Figure 2). Both specimens were in a contracted state when sampled and photographed fresh. The peduncle of the paratype is wider in both the tunic and viscera than the holotype. The peduncle, relative to the rest of the body (described as ‘trunk’ by Oka, 1918), is shorter than in the holotype. The peduncle’s longitudinal muscle band extends most of the length unlike the holotype’s muscle band which is restricted to the upper half of the peduncle. The trunk is also larger and projects anteriorly further than the length of the peduncle, unlike the holotype, whose peduncle is longer than the trunk’s anterior length. The fresh (pre-preservation) paratype tapered anteriorly compared to the more even spherical trunk of the holotype. In the preserved state, the oral siphon does not taper anteriorly but widens at the more developed peripharyngeal muscle band which presents as a constriction point in the trunk compared to the holotype whose oral siphon tapers anteriorly from its less developed peripharyngeal muscle band. A tunic velum is not present; this structure can is very thin and fragile in the holotype. The anterior fringes on the oral siphon lobes are more prominent in the paratype. The oral cavity posterior to the “beak” and anterior to the peripharyngeal band constriction (anterior to the branchial sac) is smooth with shallow radial furrows in the holotype, these radial furrows present in the paratype divided by swollen transparent tissue, potential artefact of prolonged preservation in formalin. The atrial siphon projects considerably further superiorly (dorsal) and is equipped with more prominent musculature. Stigmata and longitudinal vessels of the branchial sac are more pronounced.

- Etymology

This species is named in recognition of David Kaliner who provided a generous donation in support of marine biodiversity research and the Scripps Collections.

- Remarks

In comparison to all the represented Megalodicopia in the concatenated phylogeny (Figure 1), Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. is closest to Megalodicopia hians. Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. has a COI sequence divergence 4.69% from Megalodicopia hians (Table 2). Geographic differences are considerable between M. hians and Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. The type locality for M. hians is near Sado Island off the western coast of Japan in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, where it was sampled from a depth of 365 m [22], though the published sequences [26] are from much deeper. Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. type locality is the San Clemente Escarpment off the southern California coast, northeastern Pacific Ocean at a depth of 1771 m. The Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. paratype was sampled further north in the Monterey canyon system at an even greater depth of 2893 m. The distance between type localities of Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. and M. hians is 8852 km. This is a considerable distance, especially for sessile ascidians which are only motile for a short duration in their larval stage. Megalodicopia sp. sampled from the Monterey canyon system were studied in an aquarium noting a larval stage lasting between 3 days to 12 weeks [67]. The most notable geographical difference between the two is depth. Megalodicopia hians is one of the most shallow octacnemids based on its type locality depth of 365 m and reported depths near Toyama Bay, Japan between 643–841 m [22,28,68]. Gut content analysis of M. hians indicates an emphasis in microphagy via suspension feeding and occasional opportunistic macrophagy via their specialized oral siphons [68]. Greater ocean depths correlate with decreased planktic biomass so it is possible that there would be a shift towards macrophagy in deeper species like Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. [9]. Gut contents were analyzed via microscopy and evidence of macrophagous prey was found (Mandre pers. obs.). In-depth gut content analysis for microphagous prey was not conducted.

Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. is a medium-sized Clade I Megalodicopia and is morphologically more like Megalodicopia hians than to Megalodicopia rineharti with its longer peduncle, complete circle of peripharyngeal muscle fibers, oral tentacles lacking ampullae, irregular polygonal stigmata shape, and six lobed atrial siphon. Megalodicopia hians was described with a peduncle base that is widened like a disc, a feature not observed in our specimens in situ (Figure 3A–C) [22]. Megalodicopia hians differs from Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. with its ciliated S-shaped groove proximal to the dorsal tubercle [22]. Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. differs morphologically from other congeners by the presence of a fragile, thin and transparent velum found on the anterior end of the ventral lip (Figure 4B). The term “velum” is being used in the sense that it is a thin membrane forming a partial border that can regulate the flow of water. The edge of the velum is not smooth but fringed and is curved back towards the oral siphon (Figure 3B). This fringed border does not appear to be tentacles. The velum is large enough to obstruct the oral cavity, possibly aiding in the capture of macrophagous prey, regulating water flow, or both. The velum separated when the tunic was dissected so it is unclear if it is tunic or visceral in origin. The presence of a velum has not been recorded in Megalodicopia before but there are some Situla and Dicopia species described as having a “velum”. Situla galeata is described as having a velum bordered with papillae near the mantle [66]. Situla lanosa is described with a velum that can cover the branchial sac, also emitted from the mantle and found on the ventral lip near the peripharyngeal band before it connects to the endostyle [69]. In Dicopia antirrhinum a non-muscularized velum with tentacles is described as more developed on the ventral side [49]. These three descriptions of a velum coincide with their placement near the coronal ring and the oral tentacles, part of a secondary sensory system in tunicates. In Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. the velum is displaced anteriorly far from the oral tentacle line separated by the large oral cavity and, therefore, might be a different structure altogether.

The musculature of the oral siphon includes both radial and circular muscles converged posterior to the lip corners unlike Megalodicopia rineharti and Megalodicopia perian n. sp., which lack circular muscles in this region [65]. The peripharyngeal muscle band is a continuous circle in Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. differing from the horseshoe shape described in M. rineharti where it separates near the endostyle [65]. This peripharyngeal band lies superficial to the oral tentacle line in all Megalodicopia. Oral tentacles in Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. are larger and more numerous on both the ventral and dorsal sides where in M. rineharti the oral tentacles are more developed only on the ventral side [65]. Oral tentacles are in two sizes (0.5 and 1 mm) and overlap. Unlike M. rineharti, there are no ampullae on the oral tentacles [65]. The dorsal lamina is completely reduced like M. hians [22].

Unlike M. rineharti, the non-perforated zone of the branchial sac between the peripharyngeal band and stigmata, is smooth and void of papillae [65]. Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. stigmata are more similar to M. hians in their polygonal shape and clustering, with both quite different from the oval stigmata of M. rineharti which often form pairs and sometimes quadruplets [65]. The endostyle may at first appear to bisect most of the branchial sac before terminating at the esophagus. This is not the case, as the endostyle bisects the ventral third of the branchial sac before it forms a branchial pit where it projects posteriorly through the branchial tissue, terminating near the base of the stomach. Dorsal to this branchial pit, the retropharyngeal groove continues in the same direction as the endostyle, running dorsally to the esophagus. The endostyle can be distinguished by its more ventral position, deeper groove, and cream border. The retropharyngeal groove is a shallower translucent groove situated between the endostyle and esophagus. The initial description of M. hians likely misinterpreted the endostyle and retropharyngeal groove as only one continuous endostyle, stating the endostyle reaches the esophagus. This organization is notably different from M. rineharti which is described with a short endostyle ending far from the esophagus [22,65].

Megalodicopia hians has a bi-lobed anus whereas M. rineharti has a simple anus [22,65]. In Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. the anus is simple but the end folds back exteriorly. Gonoducts are described in both M. hians and M. rineharti, but they remain elusive in Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. where they are likely much more reduced in size. Two unknown endobionts with the same morphology were observed in the holotype, one in the dorsal branchial sac near the esophagus and one posterior to the stomach, the latter could be misinterpreted as a gonoduct due to its elongated shape and proximity to the gonads however it is not connected to either testis or ovaries.

3.4.3. Megalodicopia unque n. sp.

- Material examined

Holotype. MNHNCL TUN-15014, Biobío Canyon, Eastern Pacific Ocean, Chile (−36.658 S −73.837 W), 29 October 2024, 2049.14 m, dive S0743 (slurp), coll. G. Rouse, R/V Falkor(too)/ROV SuBastian, fixed in 10% formalin, 100% ethanol subsample, attached to rocky canyon wall. GenBank COI sequence PX138916.

Paratype. MNHNCL TUN-15015, Biobío Canyon, Eastern Pacific Ocean, Chile (−36.658 S −73.837 W), 29 October 2024, 2050.39 m, dive S0743 (slurp), coll. G. Rouse, R/V Falkor(too)/ROV SuBastian, fixed in 10% formalin, 100% ethanol subsample, attached to rocky canyon wall. GenBank COI sequence PX658856.

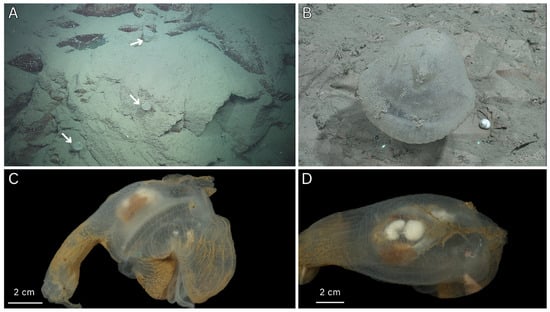

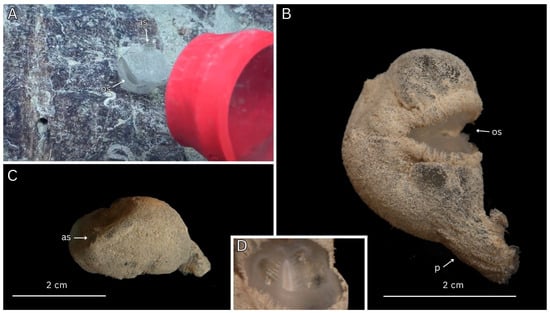

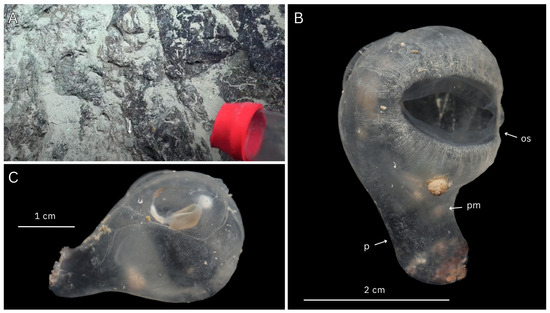

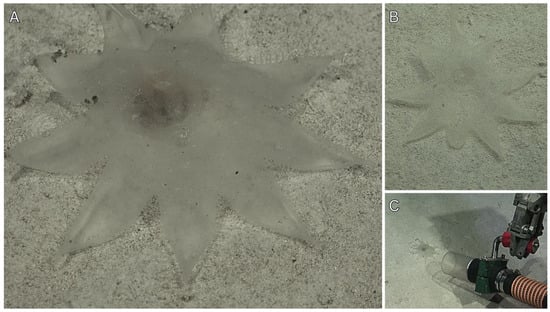

Figure 5.

In situ ROV imagery and fresh sample photos of Megalodicopia unque n. sp. (A) Three individuals (arrows) on rocky substrate in the Biobío Canyon, eastern Pacific Ocean, Chile at 2003 m. (B) Holotype (MNHNCL TUN-15014), dorsal view of live animal in situ at 2049 m, green ROV lasers are 10 cm apart. (C) Holotype, right side of whole animal, fresh. (D) Holotype, posterior view, fresh. A, B, courtesy of Schmidt Ocean Institute.

- Diagnosis (italicized text indicates unique features)

Tunic translucent, smooth in situ, wrinkled ex situ, prominent oral siphon radial furrows, thick posterior atrial siphon, thick superficial to endostyle anterior. Oral siphon bi-lobed, anteriorly developed, exposed anterior visceral tissue, well-developed dorsal lobe. Peduncle cylindrical, rhizoids absent, unclear musculature. Atrial siphon postero-dorsal, six lobes, unclear musculature. Endostyle typical anterior, unclear posterior. Stomach, orange, ovoid, right side, descends ventrally, leftward. Intestines, orange, flattened tube, left side, ascend dorsally, terminating at anus. Gonads within gut–loop, separate, spherical dorsal, reniform ventral, gonoducts unclear.

- Description

Large-sized Clade I Megalodicopia (Figure 1 and Figure 5A,B). Holotype 14 cm long, measured from base of peduncle to atrial siphon tip. Body with distinct peduncle and anteriorly developed bi-lobed oral siphon. In life, the tunic appears translucent and mostly smooth except for the dorsal oral siphon lobe’s radial furrows (Figure 5B). Ex situ and in the contracted state, the tunic appears more transparent and wrinkled throughout (Figure 5C,D). The tunic is noticeably thickened over the endostyle’s anterior and posterior to the atrial siphon (Figure 5C). The oral siphon is asymmetric with more development in the protruding dorsal lobe (Figure 5C). The visceral oral siphon is exposed and not covered by the tunic, consistent with its congenerics (Figure 5C). The peduncle is a column that quickly transitions into the trunk without taper, it is slightly shorter than the trunk (Figure 5C). The six-lobed atrial siphon is reduced, positioned dorsally at the superior (dorsal) trunk like a ‘crown’, projecting dorsally in line with the peduncle (Figure 5B,C). The endostyle’s anterior portion is visible as a white band on the ventral oral siphon lobe’s posterior, it projects posteriorly as a wide inverted arc with its apex pointed ventral, unknown position and length within the branchial sac (Figure 5C). The branchial sac is a translucent shallow bowl, posteriorly placed in the trunk where its center lies superimposed over (anterior) to the gut–gonad complex (Figure 5C). From the posterior, the esophagus is visible as a translucent funnel that originates dorsally central and slightly right of midline where it extends ventral and right towards the stomach (Figure 5D). The stomach is ovoid, colored burnt-orange in life likely due to prey contents and displaced to the right where it continues ventral looping leftward to the intestines (Figure 5D). The intestines are a flattened tube with a tan-orange gradient from ventral to dorsal. The intestines begin at the midline or bottom (ventral) of the U-shaped gut loop, extending leftward and dorsal around central gonads and terminating at the anus (Figure 5D). The anus is left of the esophagus and slightly more dorsal, unclear lobe structure (Figure 5D). The bright white gonads are nested within the gut–loop, presenting as a spherical dorsal lobe and a reniform ventral lobe connected by a narrow section of tissue (Figure 5D). Internal organization and features are unclear.

- Variation

Paratype (MNHNCL TUN-15015) mostly agrees with holotype’s exterior morphology. In situ images depict a slightly smoother tunic. The COI sequence was the same as the holotype.

- Etymology

“Unquë” is the Quenya (Tolkien’s elvish) noun for hollow, cavity, mouth. Megalodicopia unque n. sp. is characterized by a larger oral siphon, particularly the dorsal lobe, which resembles a mouth. The name is used as a noun in apposition.

- Remarks

Megalodicopia unque n. sp. is described here in a “turbo taxonomy” form [70], and is a bathybenthic, wrinkled, and dorsally developed Megalodicopia with separated gonads. It formed a well-supported clade with M. kalineri n. sp. and M. hians (Figure 1). Megalodicopia unque n. sp. COI differed by 8.82% from Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. and was most divergent from Megalodicopia hacala n. sp. at 19.96% (Table 2). Megalodicopia unque n. sp. was found from the eastern Pacific Ocean like all other Megalodicopia except for Megalodicopia hians [20]. This is the most southern species recorded of Clade I Megalodicopia. Megalodicopia unque n. sp. were observed and sampled from a rocky substrate in a submarine canyon (Biobío Canyon), the same bathymetric environment where Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. are recorded. Megalodicopia hians are reported to live in “colonies” along the slopes in Toyama Bay suggesting that this genus prefers a certain degree of slope gradient for their feeding strategy [52,55]. The four Clade I Megalodicopia inhabit two depth zones, the mesobenthic and bathybenthic. Megalodicopia unque n. sp. reside at a depth around 2000 m making them one of two bathybenthic Clade I Megalodicopia, including Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. It is reasonable to expect the presence of a less-developed branchial sac (thin, lower stigmata density) similar to Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. (Figure 4D) in contrast to the more developed branchial sac (thicker, higher stigmata density) in Megalodicopia hians [20]. The circular, rather than polygonal, stigmata of Megalodicopia rineharti distinguishes it from its congenerics [47].

Distinguishing Megalodicopia unque n. sp. from other Megalodicopia is easier in a contracted state when the oral siphon is closed and from a dorsal view the characteristic radial furrows of the oral siphon can be seen at the anterior end (Figure 5B). The most prominent in situ feature is the larger size, especially lateral width, of the contracted trunk (Figure 5B) compared to the smaller spherical trunk and longer peduncle of Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. (Figure 4B,C).

Closer inspection ex situ allows for the comparison of the tunic which is covered in distinct deep wrinkles (Figure 5C,D) unlike the lightly wrinkled tunic of Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. (Figure 4A,B) and Megalodicopia hians [20]. The tunic is uniquely thick in two regions: the ventral trunk near the perpendicular endostyle resembling a “chin” when viewed laterally, and posterior just below the atrial siphon (Figure 5C).

Megalodicopia unque n. sp. has a large protruding dorsal oral siphon lobe (Figure 5C), this asymmetry distinguishes it from the more symmetric oral siphon lobes of Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp. (Figure 4A,B), and Megalodicopia hians [20]. It is unclear how thick the tunic is over this region and if the visceral tissue reflects the perceived level of dorsal development. Megalodicopia gonads are typically compact within the gut–loop where the testes are attached to the posterior ventral surface of the ovaries (Figure 4C). Megalodicopia unque n. sp. differs from this arrangement with separated testes and ovaries connected by a strand of tissue (Figure 5D).

3.4.4. Megalodicopia perian n. sp.

- Material examined

Holotype. SIO-BIC BI1675, USA, off California, Patton Escarpment, Pacific Ocean (32.4019 N, −120.1464 W), 29 July 2021, 1797 m, coll. G. Rouse, N. Mongiardino Koch, R/V Falkor/ROV SuBastian, dive S0444 (slurp), fixed in 10% formalin, 100% ethanol subsample, attached to rock. GenBank COI sequence PX138914, 18S sequence PX241557.

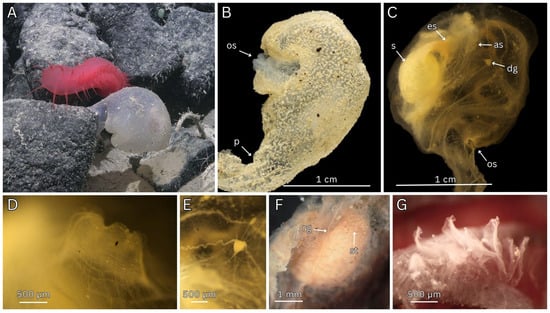

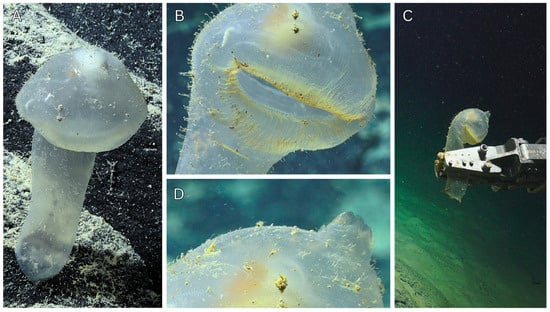

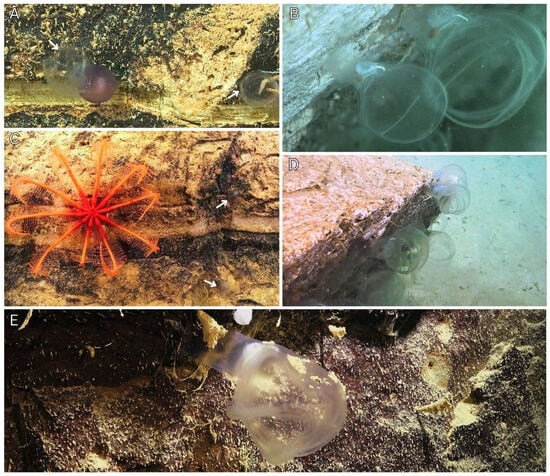

Figure 6.

In situ ROV imagery, fresh and preserved dissection photos of Megalodicopia perian n. sp. Holotype (SIO-BIC BI1675). (A) In situ, right side, whole animal on rocky substrate. (B) Fresh, left side. (C) Preserved, tunic removed, dorsal right view. (D) Light microscopy of atrial siphon, tunic removed. (E) Light microscopy of neural ganglion, tunic removed. (F) Anterior view of branchial sac. (G) Light microscopy of oral tentacles. Key: os—oral siphon, p—peduncle, s—stomach, es—esophagus, as—atrial siphon, dg—dorsal ganglion, rg—retropharyngeal groove, st—stigmata. (A) Courtesy of Schmidt Ocean Institute.

- Diagnosis (italicized text indicates unique, possibly apomorphic, features)

Tunic smooth, soft, gelatinous, and translucent with subtle radial wrinkles on oral siphon. Peduncle short, gradually tapered from body, no rhizoids, unclear musculature. Oral siphon circular and radial muscles present, limited muscles at lip corners. Atrial siphon postero-dorsal, six lobes, densely packed circular and radial muscles present. Prominent peripharyngeal muscle band, complete circle, anteriorly concentrated, laterally dense near oral tentacle line. Oral tentacle line laterally close to peripharyngeal band, furthest ventral and dorsal, individually large, angled almost perpendicular in line, flat, distal cleft, ampullae absent. Neural ganglion relatively large, tear drop shape, anterior end wide, prominent lateral undulating nerves radiate left and right, smaller anterior and posterior undulating nerves. Dorsal tubercle conical bump. Anterior endostyle unclear. Retropharyngeal groove bisects branchial sac, terminating at esophagus. Esophagus central and dorsally displaced in branchial sac, irregular disc shape. Branchial sac posterior, short imperforate region anterior near peripharyngeal band, large irregular unciliated stigmata not clustered together, branchial vessels concentrated dorsal to esophagus. Large esophageal funnel feeds into dorsal end of stomach. Stomach relatively large, ovoid. Gonoducts unclear. Gonads nested within gut loop, unclear organization and shape.

- Description

Small-bodied Clade II Megalodicopia (Figure 6A–C). Holotype incomplete measuring 2.5 cm from base of peduncle to dorsal trunk. Tunic is translucent and smooth, with fine inconspicuous wrinkles on the bi-lobed oral siphon (Figure 6A). Tunic texture is soft and gelatinous, ex situ the tunic appears fouled (Figure 6B). Trunk gradually tapers to a short peduncle anchored to rocky substrate without rhizoids, visceral tissue extends into peduncle although musculature is unclear (Figure 6A,B). Oral siphon is hypertrophied, bi-lobed forming two lips: a ventral (lower) and a larger dorsal (upper) which project anteriorly from the peripharyngeal band, lip margins are not covered by the tunic (Figure 6B,C). The lips contain both circular and radial muscles concentrated at the anterior end, muscles converge at lip corners with a space lacking muscles posterior to the lip corners (Figure 6C). The reduced atrial siphon is dorsal and posterior, the six lobes slightly project from the body, containing small densely packed circular and radial muscle fibers (Figure 6C,D). Atrial siphon circular muscles are more numerous than the radial muscles, they are restricted to the siphon (Figure 6D). Atrial siphon radial muscles are fewer and more prominent, extending slightly onto the body (Figure 6D). The peripharyngeal muscles present as large prominent circular muscles that encircle the body anterior to the peripharyngeal band and surround the oral tentacle line (Figure 6C). The individual muscle fibers concentrate in parallel at the lateral sides near the lip corner and diverge from each other on the ventral and dorsal sides (Figure 6C). The oral tentacle line follows the directional trend of the peripharyngeal muscle fibers, parallel to the muscle fibers and proximal to the peripharyngeal band laterally, diverging anteriorly from the peripharyngeal band dorsally (Figure 6C). The body tissue is quite transparent allowing the peripharyngeal muscle bands, oral tentacle line, and peripharyngeal band to be readily seen (Figure 6C). The oral tentacles form a single line, with each individual tentacle angled almost perpendicular to the line (Figure 6G). The translucent oral tentacles are slightly narrow at their attachment, widening out into a flat irregular shape often with a cleft on the distal end, considerably larger tentacles are concentrated on the ventral side (Figure 6G). The neural ganglion is relatively large, conspicuous as a cream-colored tear drop (Figure 6E). The neural ganglion is widest at the anterior with prominent undulating nerves extending to the left and right (Figure 6E). These large nerves angle anteriorly, crossing the peripharyngeal band at the lateral sides continuing anteriorly into the ventral lip (Figure 6C). Smaller nerves project mostly anteriorly, fewer posterior in direction (Figure 6E). The dorsal tubercle is a conical bump inside the branchial cavity, anterior to the dorsal ganglion and immediately posterior and proximal to the peripharyngeal band. The anterior section of the endostyle is unclear due damage suffered during sampling (slurp gun). The retropharyngeal groove presents as an elevated ridge sharing similar translucency to the branchial tissue (Figure 6F). This structure is laterally compressed, obscuring the presence of the internal groove which bisects the branchial sac gaining height and width dorsally before turning sharply right, terminating at the esophagus (Figure 6F). The esophagus is a general disc shape, somewhat irregular and without an obvious border. The esophagus is positioned on the dorsal right side of the branchial sac forming a wide posterior funnel into the large stomach (Figure 6C). The branchial sac is posterior, forming a shallow bowl that lies directly anterior to the gut–gonad complex (Figure 6F). Immediately posterior to the peripharyngeal band lies a small imperforate region. The branchial sac is perforated by large irregularly shaped stigmata, lacking cilia (Figure 6F). The stigmata are not clustered in groups (Figure 6F). Branchial vessels are visible dorsal to the esophagus and near the dorsal ganglion, with most generally transverse in their direction albeit irregular by continuing in a circular direction dorsally around the esophagus. The ovoid stomach is relatively large compared to the entire body, positioned on the right side it extends downward ventrally and then leftward, transitioning into the intestines (Figure 6C). The intestines are positioned on the left side, ascending dorsally and terminating at the anus (Figure 6C). The ovaries and testes are compact and nested within the gut loop. The testes are not obvious. The ovaries are visible due to the cream eggs spaced throughout the inside of the gut loop, variable in size. Gonoducts unclear. Heart unknown.

- Etymology

“Perian” is the Quenya (Tolkien’s elvish) noun for Hobbit, who are shorter in stature than the other free folk of Middle-Earth. Megalodicopia perian n. sp. is smaller than most other Megalodicopia and boasts a relatively large stomach almost as if they enjoyed a breakfast, second breakfast, elevenses, and perhaps an afternoon tea. The name is used as a noun in apposition.

- Remarks

Megalodicopia perian n. sp. was recovered as sister taxon to Megalodicopia hacala n. sp. (Figure 1). These species form Megalodicopia Clade II (Figure 1). COI sequences for Megalodicopia perian n. sp. differs by 16–18% from all other Megalodicopia, including its sister, Megalodicopia hacala n. sp. (Table 2). Clade II Megalodicopia exclusively inhabit the bathybenthic zone. Megalodicopia perian n. sp. was sampled from the Patton Escarpment in the NE Pacific Ocean, a steep ridge that is part of the larger Southern California Borderland, at a depth of 1797 m where it was attached to a rocky substrate. Megalodicopia are typically found on rocky substrates, often on canyon walls and slopes [68,71]. Megalodicopia are attached to rocky substrate by a peduncle of variable development, with a base that lacks rhizoids. In contrast, peduncle rhizoids are common in Benthascidia, Dicopia, and Situla, where they likely help anchor the body into sandy or loose sediment [20,21,31,49,51,72].

Clade II Megalodicopia are shorter than Clade I. Clade II holotypes average a length of 2.4 cm which is considerably smaller than the Clade I holotype average length of 10.5 cm (over four times the size). Megalodicopia perian n. sp. and its sister Megalodicopia hacala n. sp. differ from Clade I with a reduced peduncle that gradually tapers into the trunk without clear demarcation between the two. Clade I includes M. hians (Figure 1) which is originally described as also having no clear demarcation between the trunk and peduncle [22]. This is an example of the inherent subjectivity when describing a species based solely on morphology. The original illustration of M. hians [22] depicts a body that in our opinion has a distinct peduncle and trunk, and a less gradual transition between the two regions, contradicting the written description. The original M. hians illustration agrees more with Clade I morphology while the written description agrees with Clade II morphology. Megalodicopia hians is positioned within Clade I based on the available DNA sequences (Figure 1), which is why we place an emphasis on the illustration as a more accurate depiction of M. hians general shape. Furthermore, M. hians sampled near the type locality resemble the original illustration rather than the written description [68].

Megalodicopia exhibit varying degrees in their dorsal development, including the atrial siphon. The overall body shape in Clade II, with tunic intact, exhibits dorsal development of the oral siphon in conjunction with a ventral reduction in both the oral siphon and peduncle (Figure 6B and Figure 7B). The level of ventral reduction is unclear in the visceral body owing to previously mentioned damage during sampling which tore the ventral lip, trunk, and entire peduncle of Megalodicopia perian n. sp. holotype. Equally uncertain is the degree of reduction in the ventral viscera of Megalodicopia hacala n. sp. whose morphology is described from only in situ and fresh ex situ photographs of the whole intact animal. Despite this lack of information, muscular peduncles are also found in Situla and Vitreolabrus n. gen. and therefore should not be a defining feature for only Megalodicopia [22,65,72].

The tunic of Megalodicopia perian n. sp. is relatively less wrinkled than Megalodicopia hians, Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp., and Megalodicopia unque n. sp. Megalodicopia tunics are typically soft, gelatinous, translucent in varying degrees with conspicuous radial wrinkles on their oral siphon lips [22,65]. Megalodicopia perian n. sp. presents with a smoother unwrinkled tunic in situ (Figure 6A). Sediment and detritus can accumulate on the tunic of other Megalodicopia, which can help accentuate the wrinkles and furrows of the tunic (Figure 5C,D). Megalodicopia perian n. sp. when freshly sampled and in the preserved state presents with a fouled tunic with sediment or detritus covering the exterior uniformly due to the lack of wrinkles/furrows (Figure 6B).

The atrial siphon has six lobes (Figure 6D) like most Megalodicopia, with Megalodicopia rineharti being the exception with its simple hole [65]. The atrial siphon in Megalodicopia perian n. sp. is similarly muscular with both circular and radial muscles but does not project as far dorsally like in Megalodicopia hians, Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp., and Megalodicopia unque n. sp. where the atrial siphon projects noticeably upward, presenting as a “crown” most noticeable in situ when the siphons are relaxed (Figure 3B,C).

After dissecting the tunic, it is more apparent that the body arrangement of Megalodicopia perian n. sp. resembles the typical arrangement in Megalodicopia. The visceral tissue is more transparent than the tunic allowing many structures to stand out. The oral siphon lobes are equipped with both radial and circular muscles which form a grid. The oral siphon lobes are developed anteriorly from the peripharyngeal band, one of the main defining features of both Megalodicopia and Dicopia. Anterior to the peripharyngeal band and posterior to the oral tentacle line are the large peripharyngeal muscles which form a complete circle around the body. Megalodicopia have very pronounced peripharyngeal muscles which can either form complete circles or a ‘horseshoe’ around the body, often constricting the body slightly at this position [65]. In Megalodicopia perian n. sp. the peripharyngeal muscles are condensed laterally where the oral tentacle line and peripharyngeal band are closest. Ventral and dorsal, these muscle fibers spread out more, bending slightly to the anterior (Figure 6C).

The oral tentacles form a single line where they are closest to the peripharyngeal band laterally and extend anteriorly on the ventral and dorsal sides. In all other Megalodicopia, the individual oral tentacles have their flat sides running parallel with the oral tentacle line. Megalodicopia perian n. sp. is distinct with the individual oral tentacles angled almost perpendicular to the oral tentacle line (Figure 6G). Like other Megalodicopia, the oral tentacles are flat, thinnest at their attachment and widening distally. Megalodicopia perian n. sp. oral tentacles are different in their irregular shape and distal cleft compared to the often “foliaceous” or “fan” shape in other Megalodicopia (Figure 6G). There are no ampullae at their attachment which is found in Megalodicopia rineharti [65]. Megalodicopia perian n. sp. has the typical organization of the branchial sac and gut–gonad complex. The branchial sac is posterior within the trunk, with the perforated zone forming a shallow bowl (Figure 6C,F). The branchial sac lies immediately anterior to the gut–gonad complex (Figure 6C,F).

Megalodicopia endostyle are positioned in the ventral body with the anterior end near the peripharyngeal band continuing posterior bisecting the branchial sac surface towards the esophagus. As discussed in Megalodicopia kalineri n. sp., the endostyle bisects the branchial sac shortly before it continues posteriorly through the branchial sac terminating near the bottom of the gut loop. This posterior projection of the endostyle through the brachial sac presents as a pit. Dorsal to this pit, the retropharyngeal groove almost seamlessly continues bisecting the branchial sac all the way up to the esophagus. Although the endostyle is unclear in Megalodicopia perian n. sp., the retropharyngeal groove is present. The retropharyngeal groove appears to be a raised ridge. However, at its dorsal end at the esophagus, the ridge rises and widens, unveiling a groove within. A groove is most likely throughout the whole structure with the lateral ridges compressed tightly together hiding the interior groove. It is unclear if this is natural or an artefact from formalin.

Megalodicopia perian n. sp. has large irregular unciliated stigmata that are not clustered together by branchial vessel borders. Branchial vessels are most prominent on the dorsal side of the esophagus where they run generally transverse but continue in a circular direction ventrally diminishing in prominence. This dorsal region of the branchial sac has fewer and less prominent stigmata. This arrangement of dorsal branchial vessels is similar as described in Megalodicopia rineharti [65].

The stomach is relatively large in Megalodicopia perian n. sp. where it occupies a relatively large volume for a 2.5 cm tall ascidian. The stomach appears as a distended oval. The gut–gonad complex is organized in the typical Megalodicopia fashion where the esophagus empties posteriorly into a right-sided stomach. The stomach continues ventrally downward where it transitions into the flat intestines on the left side of the U-shaped loop, ascending dorsally into the anus. The gonads are nested somewhat in the gut loop, posterior and skewed to the right on the posterior surface of the stomach. It is unclear where the testes are, they remain inconspicuous. The ovaries are visible with their cream eggs. Gonoducts are unclear due to the compacted nature of the gut–gonad complex and size of Megalodicopia perian n. sp.

3.4.5. Megalodicopia hacala n. sp.

- Material examined

Holotype. MNHNCL TUN-15016 (Voucher) SIO-BIC W14659 (subsample), Chile, Canyon de Magallanes, Pacific Ocean (−53.192705 N −75.924264 W), 2 December 2024, 3262.72 m, coll. D. Betz, R/V Falkor(too)/ROV SuBastian dive S0765 (slurp), fixed in 10% formalin, 95% ethanol subsample, attached to rock. GenBank COI sequence PX138917.

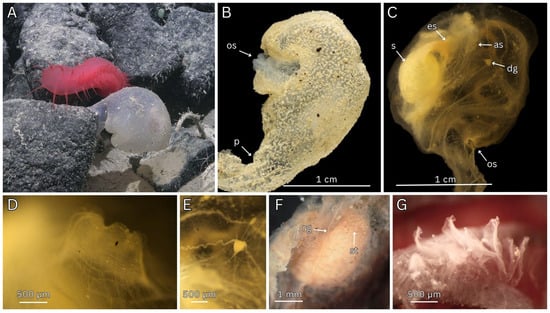

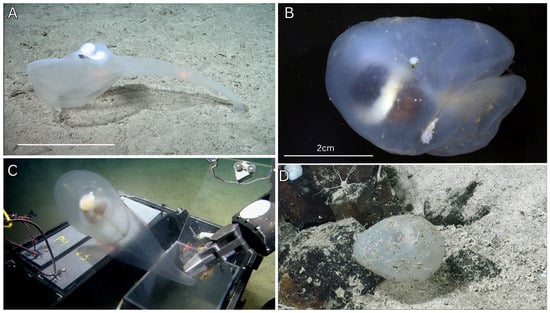

Figure 7.

In situ ROV imagery and fresh sample photos of Megalodicopia hacala n. sp. Holotype (MNHNCL TUN-15016). (A) In situ, anterior view of holotype on rocky substrate, prior to slurp sampling. (B) Fresh whole animal, right side. (C) Fresh whole animal, posterior view. (D) Anterior view of oral siphon and symbiont polynoid polychaete. Key: os—oral siphon, as—atrial siphon, p—peduncle. (A) Courtesy of Schmidt Ocean Institute.

- Diagnosis (italicized text indicates unique, possibly apomorphic, features)

Tunic translucent, uniformly fouled. Peduncle short, gradually tapered, no clear demarcation between body and peduncle; rhizoids absent. Oral siphon bi-lobed, dorsal lobe anteriorly enlarged & bulbous. Atrial siphon, reduced, dorsal.

- Description

Small Clade II Megalodicopia, measuring 2.2 cm (base of peduncle to dorsal trunk). The tunic is translucent, relatively opaque, and uniformly fouled in situ and noticeably more ex situ (translucent to tan), obscuring internal structures (Figure 7A–C). The peduncle is reduced and smaller than the trunk (Figure 7B). The peduncle gradually transitions into the trunk with no clear demarcation (Figure 7B). The base of the peduncle lacks rhizoids (Figure 7B). The oral siphon appears typical in situ and asymmetric ex situ where it is dorsally developed into a dorso-anterior bulge (Figure 7A,B). Typical oral siphon margin (Figure 7B,D). The atrial siphon is typical in position and size, unclear lobe count and musculature (Figure 7A,C).

- Etymology

“Hácala” is Quenya (Tolkien’s elvish) for yawning. Tolkien’s Markiya poem includes the phrase “undumë hácala” or abyss yawning, a great description for many group two octacnemids which are found yawning in the dark depths of the abyss. The name is used as a noun in apposition.

- Remarks

Megalodicopia hacala n. sp. is described with important information, though in a ‘turbo taxonomy’ method [70]. Megalodicopia hacala n. sp. is positioned sister to Megalodicopia perian n. sp., both of which form Clade II within Megalodicopia (Figure 1). In COI, Megalodicopia hacala n. sp. has the largest divergence, ranging from 18–20% (Table 2).

Megalodicopia hacala n. sp. was observed on a rocky substrate in a submarine canyon, typical of Megalodicopia. The recorded depth at 3262 m makes Megalodicopia hacala n. sp. the deepest described Megalodicopia, though a Megalodicopia identified as M. rineharti was redescribed from a specimen found at greater depths (3700–3970 m) off the Antarctic Peninsula [64]. However, that specimen differs dramatically from the M. rineharti holotype, which was found near the Galapagos Islands in the eastern Pacific Ocean at 695–790 m depth [65]. Key differences of the redescribed specimen include the larger peduncle, ventrally developed oral siphon, and peripharyngeal muscles forming a complete circle around the trunk [64]. Neither specimen have molecular data available and so genetic assessment is not possible, but they are likely not the same species. We agree with the authors decision to place M. rineharti in Megalodicopia rather than Situla, but this inclusion is based on the holotype, not their redescribed specimen [64]. Their Antarctic specimen could be a new Megalodicopia that is unique with its ventral development of the oral siphon. Unlike other Megalodicopia, the tunic was described as glossy, rigid, and cartilaginous and the peduncle muscles are different in their dorsal development, forming a posterior wall in the ventral half of the branchial sac [64]. The last two features are found within Vitreolabrus n. gen. (see below Section 3.4.6), a genus with many similarities to Megalodicopia. Overall, their Antarctic specimen has features indicative of both Megalodicopia and Vitreolabrus n. gen. Proper diagnosis will be difficult based solely on morphology. Megalodicopia hacala n. sp. can be distinguished from the similar Megalodicopia perian n. sp. by its bulbous dorsal oral siphon lobe and shorter peduncle (Figure 7B). A polynoid worm found within the oral cavity (Figure 7D) is member of genus Macellicephala (Polynoidae) (G. Rouse pers. obs.), a group that commonly associates with benthic megafauna and was likely a symbiont rather than prey.

3.4.6. Vitreolabrus n. gen.

Type species. Vitreolabrus axonae n. gen. n. sp.

- Diagnosis (italicized text indicates unique, possibly apomorphic, features)

Solitary pedunculate octacnemid. Tunic transparent, hyaline, smooth. Visceral tissue transparent. Oral siphon bi-lobed; symmetric; fine shallow radially wrinkled tunic; radial muscles present throughout, circular muscles restricted to anterior; lobes not anteriorly developed. Atrial siphon reduced, dorsally positioned, six lobes; radial and circular muscles present. Peduncle variable length, anterior longitudinal muscles extend postero-dorsally near endostyle, forming posterior muscle wall on ventral half of body, viscera flat, rhizoids absent. Branchial sac shallow bowl, posterior. Stigmata large, elliptical, unciliated, often paired. Gut U-shaped loop, posterior; large stomach on right side, descending ventrally, transitioning leftward to intestines, ascending dorsally, terminating at anus. Gonads nested within gut loop; ovaries central and dorsal, large spherical eggs; testes on ventral ovaries, acinar.

- Description

Solitary, pedunculate octacnemid. Tunic transparent and smooth, radially wrinkled on the two oral siphon lobes (lips). Oral siphon with two lip-like lobes: a ventral lower lip and a dorsal upper lip, both with radial and circular muscles; not anteriorly developed from the peripharyngeal band. Portion of oral siphon viscera exposed from tunic. Atrial siphon reduced, with six lobes, positioned dorsally or dorso-posteriorly, with radial and circular muscles. Peduncle variable in development, projecting ventrally to the substrate; no rhizoids at base. Anterior longitudinal muscle band on peduncle extends postero-dorsally near endostyle, forming a posterior muscle wall on the ventral half of the body. Posterior branchial sac with perforated zone restricted to center, superimposed over gut–gonad complex. Perforated zone consists of large, elliptical, unciliated stigmata, often in pairs. Imperforate zone forms an anterior ring around central and posterior perforated zones. Smooth branchial tissue between stigmata forms a network of vessels in a generally flat layer. Endostyle a subtle, sometimes transparent, shallow groove bisecting the branchial sac and terminating posteriorly at the esophagus. Esophagus positioned dorso-posteriorly in the branchial sac, slightly on the right; forms a large, white or translucent disc extending ventrally and posteriorly into a right-sided stomach. Gut forms an orange U-shaped loop posterior to the branchial sac. Stomach descends ventrally, transitions left into intestines, and ascends dorsally, terminating at the anus; stomach considerably larger than intestines. Gonads situated within gut loop.

- Etymology

Vitreolabrus is the combination of the Latin vitreum (meaning resembling glass in its transparency) with the Latin word labri (meaning lips). This name highlights the incredible transparency of this ascidian while emphasizing the oral siphons form “lips”.

- Remarks

Vitreolabrus n. gen. comprise two new species, Vitreolabrus axonae n. sp. (3.4.7), Vitreolabrus virin n. sp. (3.4.8) and an undescribed Vitreolabrus sp. (3.4.11). Both the newly described species are represented by their respective holotypes, with Vitreolabrus axonae n. sp. dissected for in-depth morphological analysis. The Vitreolabrus virin n. sp. holotype was not available for dissection. Vitreolabrus n. gen. formed a well-supported clade (Figure 1, bootstrap = 100) sister to Megalodicopia and Dicopia.

Vitreolabrus n. gen. and Megalodicopia appear similar based on traits such as the presence of a muscular peduncle, two oral siphon lobes forming lips, transparent tunic, a branchial sac forming a shallow bowl, and a posteriorly placed gut–gonad complex. In Vitreolabrus n. gen. the tunic is hyaline, flexible and supportive, with a smooth surface except for subtle radial wrinkles restricted to the oral siphon margin. These wrinkles are less pronounced than those in Megalodicopia, whose softer, gelatinous tunic has a more irregular, wrinkled/furrowed appearance, often accumulating sediment or detritus (Figure 4A, Figure 5C,D, Figure 6B and Figure 7B,C).

The peduncle can vary in development (length) in both Vitreolabrus n. gen. and Megalodicopia. Vitreolabrus n. gen., Megalodicopia and Situla macdonaldi have a muscular peduncle [22,65,72]. The base of the peduncle lacks rhizoids as for to Megalodicopia, distinguishing them both from several Situla, Benthascidia, and Dicopia [20,21,49,51,72,73]. Both Vitreolabrus n. gen. and Megalodicopia possess an anteriorly positioned muscular band running longitudinally from the peduncle into the body. However, Vitreolabrus n. gen. is distinguished by the continuation of this peduncle muscle band into the body, where it transitions from an anterior to a posterior orientation, forming a muscular wall concentrated in the ventral half of the body. In contrast, Megalodicopia lacks this dorsal muscular development; instead, the band bifurcates around the endostyle into two (left and right) fans that quickly anastomose. Situla macdonaldi is the only species in its genus described with a muscular peduncle, with muscles extending deep into the body and entering both the upper and lower baskets [72]. In Vitreolabrus n. gen., the peduncle musculature is restricted to the ventral half of the body, lacking such extensive development.

The oral siphon varies greatly across Octacnemidae. Oral siphon lobes range from simple, to bi-lobed, to eight-lobed, and they differ in their degree of hypertrophy. Musculature also varies; well-developed musculature (presence of both radial and circular muscles) enables the typically large oral cavity to open and close, facilitating predation on macrophagous prey. Vitreolabrus n. gen. possesses an oral siphon with two lobes—one ventral (lower) and one dorsal (upper)—which resemble “lips”. This morphology is shared with some Situla and Kaikoja species, as well as all Megalodicopia and Dicopia [19,20,21,49,51,72,73]. However, the oral siphon of Vitreolabrus n. gen. differs from Megalodicopia and Dicopia in that it is not anteriorly developed from the pericoronal ridge. In Dicopia and Megalodicopia, considerable anterior development of the oral siphon from the peripharyngeal band/oral tentacle line is a characteristic trait [65]. Instead, the lack of anterior development in Vitreolabrus n. gen. aligns more closely with Situla and Kaikoja despite phylogenetic divergence (Figure 1). The oral siphon musculature in Vitreolabrus n. gen. is well developed, forming a grid network of radial and circular muscles, like Megalodicopia and Dicopia but differing with their circular muscles restricted to the anterior. The atrial siphon is reduced and positioned dorsally, resembling that of Megalodicopia. Vitreolabrus n. gen. has six atrial siphon lobes, whereas Megalodicopia exhibits variation in lobe number, with M. rineharti uniquely possessing a simple design [65].

3.4.7. Vitreolabrus axonae n. gen.

- Material examined

Holotype. WAM Z100643, Western Australia, Cape Range Canyon, Indian Ocean (−21.8841 S; 113.0142 E), 15 March 2020, 2505 m, coll. N.G. Wilson, G. Rouse, J. Ritchie, RV Falkor/ROV SuBastian dive 336, fixed in 75% ethanol, 100% ethanol subsample, attached to rock. GenBank COI sequence PX658857, 18S sequence PX624315, and H3 sequence PX577545.

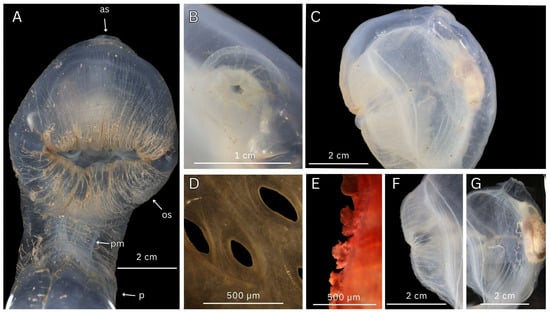

Figure 8.

In situ ROV imagery of Vitreolabrus axonae n. sp. n. gen. Holotype (WAM Z100643): (A) anterior view of the whole animal on a rocky substrate; (B) anterior view of oral siphon; (C) right view of whole animal in ROV claw; (D) anterior view of atrial siphon. (A–D) Courtesy of Schmidt Ocean Institute.

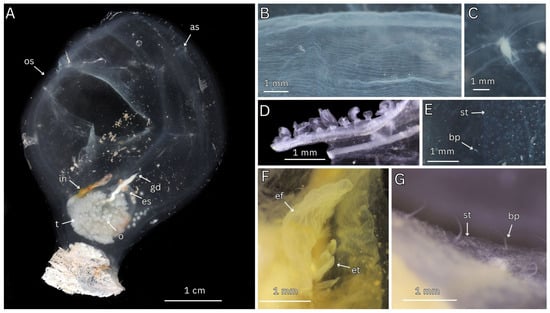

Figure 9.

Fresh and preserved dissection photos of Vitreolabrus axonae n. sp. n. gen. (WAM Z100643) (A) Anterior view of oral siphon and peduncle, fresh. (B) Dorsal view of atrial siphon, preserved. (C) Left side of trunk, preserved. (D) Light microscopy of stigmata. (E) Light microscopy of oral tentacles stained with haemotoxylin. (F) Left side of oral siphon, tunic removed. (G) Left side of posterior trunk, tunic removed. Key: as—atrial siphon, os—oral siphon, p—peduncle, pm—peduncle muscles.

- Diagnosis (italicized text indicates unique, possibly apomorphic, features)