Abstract

The systematics of the polychaete family Ampharetidae in Korean waters have been marked by long-standing confusion and potential misidentifications of key species. This study presents a critical systematics re-assessment of Korean ampharetids, based on newly collected material and historical voucher specimens from the National Marine Biodiversity Institute of Korea (MABIK). We used detailed morphological examinations, complemented by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) for the uncini structure and methyl green staining patterns (MGSPs) to reveal cryptic diagnostic characters. We provide the first records of four species from Korea: Amphicteis chinensis, Anobothrus nataliae, Auchenoplax worsfoldi, and Phyllocomus chinensis. Our re-examination of voucher specimens, including provisionally labeled MABIK material, corrects significant historical misidentifications. Notably, specimens previously identified as Ampharete arctica are shown to be Anobothrus nataliae, and historical records of Amphicteis gunneri are identified as a complex of other species, including A. chinensis. Furthermore, the detailed MGSPs for all four species are described for the first time, proving to be a valuable auxiliary diagnostic tool, especially for identifying cryptic structures like the thoracic ridges in A. nataliae. This research demonstrates that ampharetid diversity in Korea is significantly underestimated and establishes that a modern morphological framework, integrating the combined use of MGSP and SEM, is essential for the systematics of the family.

1. Introduction

The family Ampharetidae Malmgren, 1866, comprises tube-dwelling, surface-deposit-feeding polychaetes, primarily characterized by a distinct prostomium, numerous buccal tentacles, and typically four pairs of branchiae on the anterior segments [1,2]. They are inhabitants of various marine sediments, from coastal mudflats to the deep sea [1]. The family currently includes approximately 55 genera, of which 28 are monotypic, often requiring expert knowledge for accurate generic identification [1,3,4].

The systematic knowledge of Ampharetidae in Korean waters has recently undergone significant revision. Historically, based on foundational work [5,6] and subsequent records [7], the Korean fauna was thought to consist of six species: Amage auricula Malmgren, 1866; Ampharete finmarchica (M. Sars, 1865); Amphicteis gunneri (Sars, 1835); Amphisamytha japonica (McIntosh, 1885); Melinna elisabethae McIntosh, 1885; and Paramphicteis weberi (Caullery, 1944) [8]. However, this list requires critical updates based on recent systematic revisions. Firstly, the subfamily Melinninae Chamberlin, 1919, including Melinna, has been elevated to the family level (Melinnidae) based on molecular data [9,10], although it is still listed as Ampharetidae in the national species inventory [8]. Secondly, recent systematic studies by Kim et al. [11], utilizing integrative methods, and corroborated by the first author’s own preliminary research, revealed that previous Korean records of Ampharete finmarchica and A. auricula were misidentifications of two new species, Ampharete koreana Kim, Kim and Jeong, 2025, and Ampharete namhaensis Kim, Kim and Jeong, 2025, respectively. Kim et al. [11] also reported Amphicteis aff. glabra. Consequently, the current confirmed Korean Ampharetidae fauna comprises six species in four genera: Ampharete, Amphicteis, Amphisamytha, and Paramphicteis [8,11].

Despite this recent progress, significant knowledge gaps and ambiguities remain. Notably, the Korean records of Amphicteis gunneri and Amphisamytha japonica, first reported by Paik in the 1980s [6], have not undergone any re-examination. The identity of A. gunneri in Korea is particularly questionable. This species is frequently reported in local ecological surveys, yet its type locality is in the North Atlantic (Norway), and recent systematic consensus suggests its distribution is restricted to the Arctic, North Atlantic, and European waters [12,13,14]. The original description by Paik [6] is insufficient, lacking crucial diagnostic details of paleae, chaetigers, and abdominal uncini, which are essential for species-level identification and have been detailed in modern redescriptions of the A. gunneri holotype [12,13,14]. Furthermore, a recent examination by the first author of East China Sea specimens, previously identified as Ampharete arctica, revealed the dominant occurrence of Anobothrus spp. (unpublished data) [15]. As the genus Anobothrus has not been officially recorded from Korea to date, it is highly plausible that local researchers have misidentified it as Ampharete, which shares the common feature of a trilobate prostomium. A preliminary review of voucher specimens (MABIK) labeled as A. arctica confirmed the presence of Anobothrus in Korean waters.

This confusion underscores the necessity of re-examining historical records and current collections using detailed morphological analyses, especially when molecular data is unavailable. Techniques such as methyl green staining, which reveals species-specific patterns by selectively highlighting the distribution of epidermal glandular tissues [11,16], and scanning electron microscopy (SEM), which clarifies features like thoracic and abdominal uncini, provide crucial information. These methods are essential for accurately identifying taxa previously confounded by brief or incomplete descriptions [12,13].

The aims of this study are (1) to conduct a systematic re-assessment of Ampharetidae collected from Korean waters, utilizing both newly obtained material and historical voucher specimens deposited at the National Marine Biodiversity Institute of Korea (MABIK); (2) to report four Ampharetidae species as new records for the Korean fauna; (3) to provide detailed morphological descriptions; and (4) to clarify the status of problematic historical records and contribute to an updated inventory of the Korean polychaete fauna.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Specimen Collection and Deposition

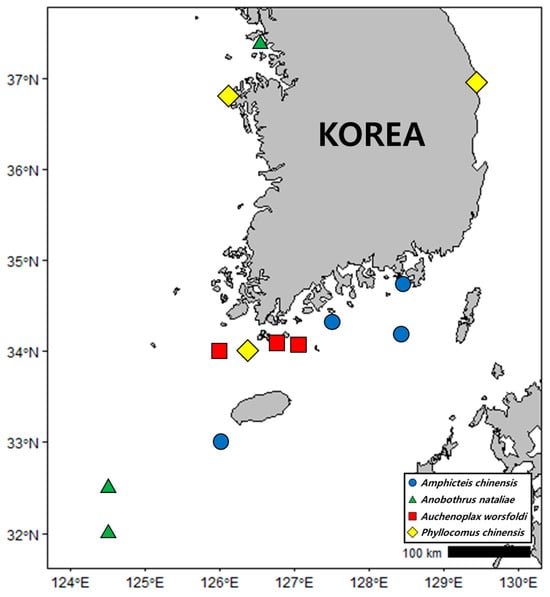

Specimens were newly collected from 20 sublittoral stations in semi-enclosed bays along the southern coasts of Korea and from the East China Sea near the Korean Peninsula (Figure 1). Samples were obtained using a 0.05 m2 Van Veen grab. Sediments were sieved through a 0.5 mm mesh, and the retained fractions were relaxed in 7% MgCl2. Relaxed specimens were fixed in 10% buffered seawater–formalin and subsequently preserved in 80% ethanol.

Figure 1.

Map of Korea showing collection sites and ampharetids newly reported at each site.

For systematics re-assessment, additional voucher specimens were borrowed from the National Marine Biodiversity Institute of Korea (MABIK). This material included 5 unidentified Amphicteis sp. (MABIK NA00121915, MABIK NA00122110, MABIK NA00122134, MABIK NA00122169, MABIK NA00155451), 3 unidentified Phyllocomus sp. (MABIK NA00124555, MABIK NA00124556, MABIK NA00125036), 20 Amphicteis gunneri (MABIK NA00104192, MABIK NA00104196, MABIK NA00105022, MABIK NA00105023, MABIK NA00105214, MABIK NA00105246, MABIK NA00110733, MABIK NA00110734, MABIK NA00110738–NA00110741, MABIK NA00123172, MABIK NA00123275, MABIK NA00123276, MABIK NA00123893, MABIK NA00124129, MABIK NA00124455, MABIK NA00150439, MABIK NA00153029), 6 Amphicteis hwanghaiensis (MABIK NA00156693, MABIK NA00156698–NA00156702), 19 Auchenoplax crinita (MABIK NA00124594–NA00124599, MABIK NA00124620–NA00124624, MABIK NA00124662–NA00124664, MABIK NA00124947, MABIK NA00124965, MABIK NA00125000, MABIK NA00125032, MABIK NA00125046), and 4 Phyllocomus hiltoni (MABIK NA00115874, MABIK NA00136471–NA00136473). All examined specimens, including newly collected material, are deposited at MABIK.

2.2. Morphological Observations and Staining Procedures

Morphological characters were examined using a stereomicroscope (Stemi 305; ZEISS, Oberkochen, Germany) for low-magnification observations and a compound microscope (Eclipse Ci-L; Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) for high-magnification details. Morphological features were documented exclusively through digital photographs (micrographs) taken with cameras attached to both microscopes. Digital photographs and measurements were processed using OSUN 2.0 software (Osun Hightech, Goyang-si, Republic of Korea).

2.3. Staining Procedures

Two staining methods were employed to visualize different morphological features. To observe the species-specific patterns of glandular tissues, specimens were stained with a methyl green [11,16]. Specimens were briefly immersed in the staining solution (approx. 60 s) until a distinct color pattern emerged, then rinsed in 80% ethanol for differentiation. Separately, Shirlastain A solution (SDLATLAS, Rock Hill, SC, USA) was used to enhance the overall contrast of morphological structures and facilitate observation. Specimens were immersed for a short period (approx. 30 s) and subsequently rinsed. Staining results from both methods were documented through photography [17].

2.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Some characteristics were obtained via scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Tissues were dehydrated through a graded ethanol series (80% to absolute ethanol). The samples were then critical-point dried, mounted on aluminum stubs, and coated with gold–palladium. Micrographs were taken using a Scanning Electron Microscope Axia ChemiSEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Brno, Czech Republic) at the Center for Research Facilities (Yeosu Campus), Chonnam National University.

2.5. Morphological Terminology

The terminology used in descriptions and systematic accounts follows established major works on Ampharetidae, such as Holthe (1986), Jirkov (2001), and Kim et al. (2025) [11,18,19]. In all species, the first chaetiger bearing notopodia (segment 3) is counted as TC1.

3. Results

3.1. Systematics

Family Ampharetidae Malmgren, 1866 [1].

3.2. Genus Amphicteis Grube, 1850 [20]

3.2.1. Amphicteis chinensis Sui & Li, 2017 [21] (Figure 2 and Figure 3)

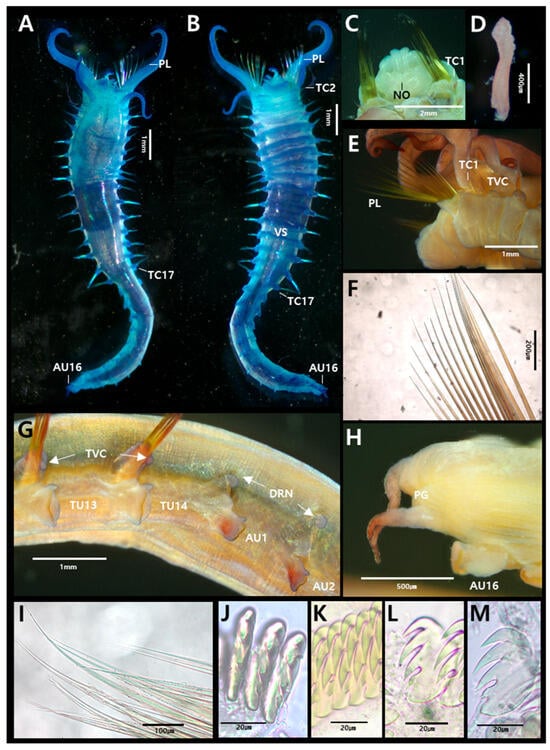

Figure 2.

Amphicteis chinensis Sui & Li, 2017 (specimen JUMA_20250819_001): (A) entire body, dorsal view; (B) entire body, ventral view; (C) prostomium, dorsal view; (D) buccal tentacle; (E) anterior end, lateral view; (F) paleae; (G) thorax–abdomen junction, lateral view (last two thoracic and first two abdominal segments); (H) pygidium; (I) limbated capillary chaetae from TC4; (J) uncini from TU5, frontal view; (K) uncini from TU5, lateral view; (L) uncini from AU1, lateral view; (M) uncini from AU6, lateral view. Abbreviations: AU, abdominal unciniger; DRN, digitiform rudimentary notopodia; NO, nuchal organs PG, pygidium; PL, paleae; TC, thoracic chaetiger; TU, thoracic unciniger; TVC, tuberculate ventral cirri; VS, ventral shields.

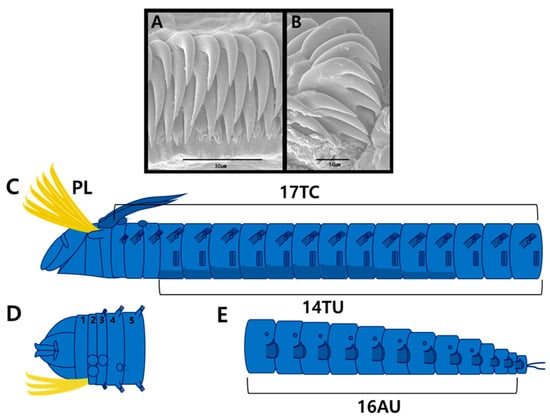

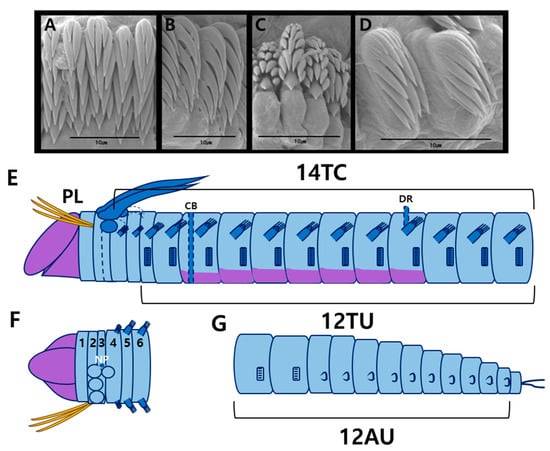

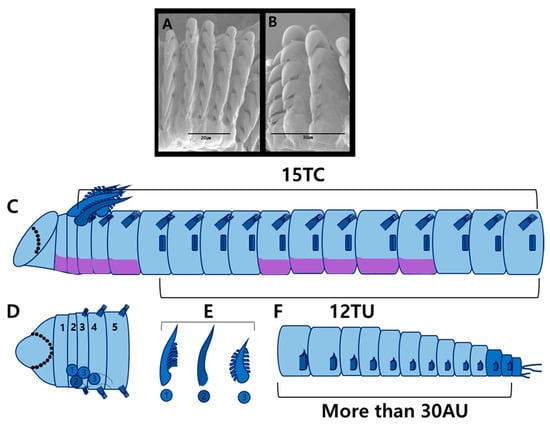

Figure 3.

Amphicteis chinensis Sui & Li, 2017 (specimen JUMA_20250819_001). scanning electron micrographs and methyl green staining patterns: (A) uncini from TU1, frontal view; (B) uncini from AU1, lateral view; (C) MGSP schematic of thorax, lateral view; (D) anterior end, dorsal view (numbers 1–5 indicate segment numbers); (E) abdomen, lateral view. Abbreviations: AU, abdominal unciniger; PL, paleae; TC, thoracic chaetiger; TU, thoracic unciniger.

3.2.2. Material Examined

One specimen (MABIK NA00121915): Gyeongsangnam-do, Republic of Korea, 34°12′11.9988″ N, 128°25′48″ E, 74 m depth, 1 October 2008, collected by grab. One specimen (MABIK NA00122110): Gyeongsangnam-do, Republic of Korea, 34°15′0″ N, 128°33′0″ E, 70 m depth, 1 December 2008, collected by grab. One specimen (MABIK NA00122134): Gyeongsangnam-do, Republic of Korea, 34°10′12″ N, 128°18′45″ E, 127 m depth, 1 December 2008, collected by grab. One specimen (MABIK NA00123172): Gyeongsangnam-do, Republic of Korea, 34°44′34.91″ N, 128°27′11.82″ E, 2 m depth, 1 May 2010, collected by grab. One specimen (JUMA_20250804_004): Geomun-do, Republic of Korea, 34°19′54.41″ N, 127°28′43.7″ E, 14 m depth, 1 April 2025, collected by Smith–McIntyre grab. One specimen (JUMA_20250819_001): Station EC05, Republic of Korea, 33°0′0″ N, 126°00′0″ E, 85 m depth, 24 August 2024, collected by Smith–McIntyre grab.

3.2.3. Description

Description based on complete specimen (JUMA_20250819_001). Body 11.5 mm long, 1.6 mm wide at thorax (Figure 2A,B).

Prostomium trilobed; paired longitudinal glandular ridges straight, no gap between them. Paired nuchal organs arranged in V, gap absent (Figure 2C). Eyespots absent. Buccal tentacles smooth, approximately 40 (Figure 2D). SG2 with 15–16 pairs of long, slender, yellow paleae; paleae about three times as thick and long as regular notochaetae (Figure 2F). A large, distinct lobe present posterior to each paleal row (Figure 2E). Four pairs of smooth branchiae present, arranged in three rows (2 + 1 + 1) on TC1–3. The pair from TC4 separated from the anterior three pairs. Posterior-most branchiae approximately 1/5 the length of the thoracic region. Two branchial groups separated by a median gap about half a branchia wide; branchiophores not fused (Figure 2A,C).

Thorax longer and wider than abdomen (Figure 2A,B). Seventeen thoracic chaetigers (TCs). Notopodia first present from TC1 to TC17. Notopodia of TC1–3 strongly reduced; TC1 appearing as a small papilla. Subsequent notopodia (TC4–TC17) well-developed, up to twice as long as wide. Notochaetae spinulose limbate capillaries, tapering to slender tips (Figure 2I). Tuberculate ventral cirri present (Figure 2E). Nephridial papillae not observed. Ventral shields well-developed until TU11, weakly developed on TU12, absent from TU13 (Figure 2B). Thoracic uncinigers (TUs) starting from TC4, thus 14 thoracic uncinigers (TU1–TU14) present. Thoracic uncini with four teeth (3 large + 1 small basal) arranged in vertical row above rostrum, and fourth, much smaller, basally located tooth; true subrostral process absent (Figure 2J,K and Figure 3A).

Abdomen shorter and narrower thinner than thorax, with sixteen uncinigers (AU1–AU16). Anterior twelve abdominal uncinigers with digitiform rudimentary notopodia (Figure 2G). Abdominal uncinigers with enlarged neuropodial pinnules and dorsal cirri (Figure 2G). Abdominal uncini similar in shape to thoracic uncini, with four teeth (Figure 2L,M and Figure 3B). Pygidium with one pair of lateral cirri (Figure 2H).

3.2.4. Methyl Green Staining Patterns

Longitudinal glandular ridges and paired nuchal ridges of the prostomium stained blue (Figure 3C,D). Branchiae stained a darker blue (Figure 3C). Ventral shields darker blue; thoracic notopodia, neuropodia, and tuberculate ventral cirri stained a darker blue than surrounding areas (Figure 3C). Abdominal region became progressively darker blue toward the posterior end; neuropodia stained dark blue (Figure 3E).

3.2.5. Remarks

The Korean specimens correspond well with the original description of Amphicteis chinensis, in possessing the most critical and unusual diagnostic features: (1) a large, distinct lobe projecting posteriorly behind the paleae (Figure 2E), and (2) four pairs of branchiae arranged in three rows (2 + 1 + 1).

A slight discrepancy was noted in the thoracic uncini. The original description by Sui and Li [21] described them as having “a single row of three teeth”. However, their accompanying line drawings (e.g., Figure 3A in [21]) clearly illustrated an additional small, basal projection, which was not mentioned in their text. Our light microscopy and SEM observations analysis of the Korean specimens confirmed this structure, revealing three large teeth in a vertical row with a fourth, much smaller, basally located tooth (Figure 2J–M and Figure 3A,B). We consider this fourth small tooth to be homologous to the basal projection depicted, but not described, in the original illustrations. Therefore, we attribute this discrepancy to an omission in the original text rather than an error in interpretation, likely due to the limitations of observing this minute structure without high-resolution light microscopy and SEM. Given the perfect congruence of the other highly unusual diagnostic characters (i.e., the post-paleal lobe and branchial arrangement), we consider this a difference in observational detail rather than a species-level difference.

The Korean specimens also match the segment counts (18 TC, 16 AU) mentioned by the original authors. The MGSP of A. chinensis is reported here for the first time. This species is now known from the East China Sea, the South China Sea, and the southern coast of Korea at depths ranging from 2 to 130 m.

3.3. Genus Anobothrus Levinsen, 1884 [22]

3.3.1. Anobothrus nataliae Jirkov, 2008 [23] (Figure 4 and Figure 5)

Anobothrus nataliae Jirkov, 2008: 126–127, Figure 12. Anobothrus nataliae—Sui, 2013: 633–635, Figure 2 [24].

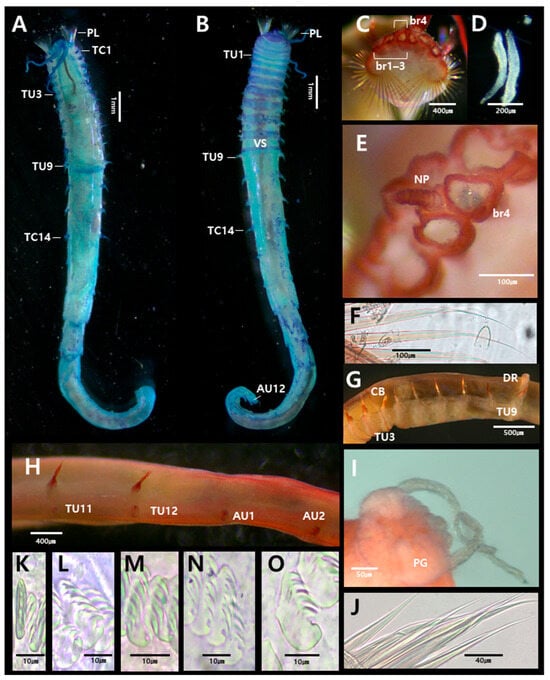

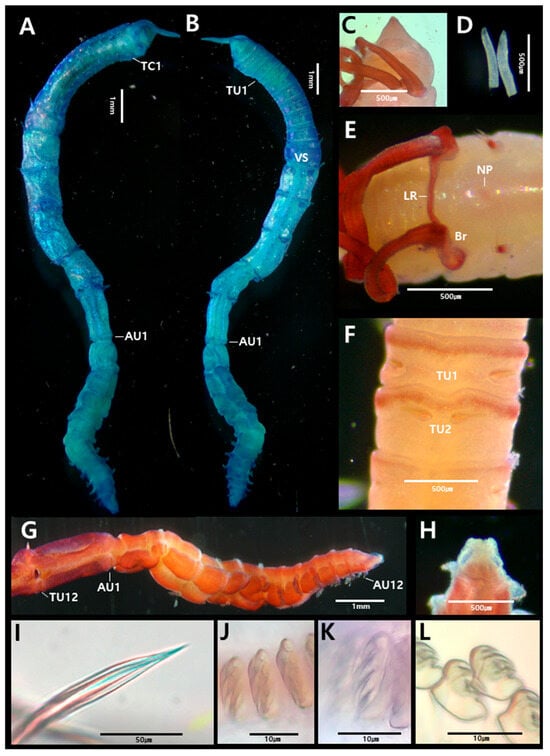

Figure 4.

Anobothrus nataliae Jirkov, 2008 (specimen JUMA_20250804_003): (A) entire body, dorsal view; (B) entire body, ventral view; (C) prostomium, frontal view; (D) buccal tentacle; (E) branchia, dorsal view; (F) paleae; (G) thoracic uncinigers 1–9; (H) thorax–abdomen junction, lateral view (last two thoracic and first two abdominal segments); (I) pygidium; (J) bilimbate capillary chaetae from TC7; (K) uncini from TU9, frontal view; (L) uncini from TU1, lateral view; (M) uncini from TU9, lateral view; (N) uncini from AU1, lateral view; (O) uncini from AU8, lateral view. Abbreviations: AU, abdominal unciniger; Br, branchia; CB, circular band; DR, dorsal ridge; NP, nephridial papillae; PG, pygidium; PL, paleae; TC, thoracic chaetiger; TU, thoracic unciniger; VS, ventral shields.

Figure 5.

Anobothrus nataliae Jirkov, 2008 (specimen JUMA_20250804_003) scanning electron micrographs and methyl green staining patterns: (A) uncini from TU5, frontal view; (B) uncini from TU10, lateral view; (C) uncini from AU4, frontal view; (D) uncini from AU5, lateral view; (E) MGSP schematic of thorax, lateral view; (F) anterior end, dorsal view (numbers 1–6 indicate segment numbers); (G) abdomen, lateral view. Abbreviations: AU, abdominal unciniger; CB, circular band; DR, dorsal ridge; NP, nephridial papillae; PL, paleae; TC, thoracic chaetiger; TU, thoracic unciniger.

3.3.2. Material Examined

One specimen (MABIK NA00106182): West Sea, Republic of Korea, 37°23′38.14″ N, 126°33′43.11″ E, 14 m depth, 8 October 2011, collected by grab. Two specimens (MABIK NA00106183–84): West Sea, Republic of Korea, 37°29′5.65″ N, 126°35′29″ E, depth not recorded, 8 June 2012, collected by grab. Fourteen specimens (JUMA_20250804_002): Station EC18, 32°0′0″ N, 124°30′0″ E, 73 m depth, 22 August 2024, collected by Smith-McIntyre grab. Fourteen specimens (JUMA_20250804_003): Station YE17, 32°30′0″ N, 124°30′0″ E, 71 m depth, 3 July 2025, collected by Smith-McIntyre grab.

3.3.3. Description

Description based on complete specimen (JUMA_20250804_003), 23 mm long, 1.1 mm wide at thorax (Figure 4A,B).

Prostomium trilobed (Ampharete-type); paired glandular ridges and nuchal ridges absent (Figure 4C). Eyespots absent. Buccal tentacles smooth, approximately 70 (Figure 4D). SG2 with 22–27 pairs of paleae; longer than prostomium, about three times as thick and long as regular notochaetae, with slender caudate tips (Figure 4F). Four pairs of smooth branchiae present, arranged in two transverse rows (3 + 1) on SG2–5. Pair from SG5 located posterior to innermost pair of anterior ones (Figure 5F). All branchial groups completely fused at base; a single nephridial papilla present between groups (Figure 4E).

Thorax longer and wider than abdomen (Figure 4A,B). Fourteen thoracic chaetigers (TCs). Notopodia present from TC1 to TC14. Notopodia of TC1–2 reduced. Subsequent notopodia (TC3–TC14) well-developed, about as long as wide. Notochaetae simple, spinulose bilimbate capillaries, tapering to slender tips (Figure 4J). Tuberculate ventral cirri absent. Thoracic neuropodia (uncinigers) starting from TC3, thus 12 thoracic uncinigers (TU1–TU12). Faint circular band (ridge) present on anterior part of TU3; a conspicuous dorsal ridge on TU9 (Figure 4G). Ventral shields well-developed until TU9, absent from TU10 (Figure 4B). Thoracic uncini with six teeth arranged in two vertical rows above a single large main tooth (rostrum) (Figure 4K–M and Figure 5A,B).

Abdomen shorter and narrower than thorax, with twelve uncinigers (AU1–AU12). First two uncinigers (AU1–AU2) with tori, subsequent uncinigers (AU3–AU12) with pinnules. Neuropodial dorsal cirri or papillae absent (Figure 4H). Digitiform rudimentary notopodia absent (Figure 4H). Abdominal uncini with 4–5 teeth arranged in 3–4 vertical rows above a rostrum (Figure 4N,O and Figure 5C,D). Pygidium with one pair of lateral cirri (Figure 4I).

3.3.4. Methyl Green Staining Patterns

Prostomium stained pale violet (Figure 5E,F). Base of the branchiae stained light blue, while branchiae stained darker blue (Figure 5E). Thoracic notopodia stained dark blue (Figure 5E,F). Circular band of anterior TU3 stained a darker blue than the surrounding area. Dorsal ridge of TU9 stained blue (Figure 5E). Ventral shields violet up to TU9 (Figure 5E). Abdominal region and neuropodia stained light blue (Figure 5G).

3.3.5. Remarks

The Korean specimens are identical to Anobothrus nataliae, characterized by all branchial groups being completely fused at the base and the presence of faint circular band on TU3 and conspicuous dorsal ridge on TU9.

The presence of this species in Korean waters clarifies previous systematic confusion. Several ecological studies from Korea reported Ampharete arctica as a dominant species in coastal waters near Jeju Island [15]. However, our recent surveys (2024–2025) revealed that A. nataliae was the dominant species in these areas, while Ampharete arctica (or A. koreana [11]) was not found. Given that Anobothrus and Ampharete share a similar trilobed prostomium, and the fact that Anobothrus was not previously known from Korean waters, it is highly likely that previous records of A. arctica from this region were misidentifications of A. nataliae (see details in Discussion). The MGSP of A. nataliae is reported here for the first time, providing new diagnostic characters (e.g., stained thoracic ridges) for the species. This species has a wide distribution, previously reported from Chile–Galera, Kaiser Wilhelm-II-Land, the southern Yellow Sea, and the East China Sea, and is now confirmed in Korean waters at depths of 14–73 m.

3.4. Genus Auchenoplax Ehlers, 1887 [25]

3.4.1. Auchenoplax worsfoldi Jirkov & Leontovich, 2013 [26] (Figure 6 and Figure 7)

Auchenoplax worsfoldi Jirkov & Leontovich, 2013: 229–230, Figure 2A–D. Auchenoplax worsfoldi—Sui, 2018: 145–147, Figure 1 and Figure 2 [27].

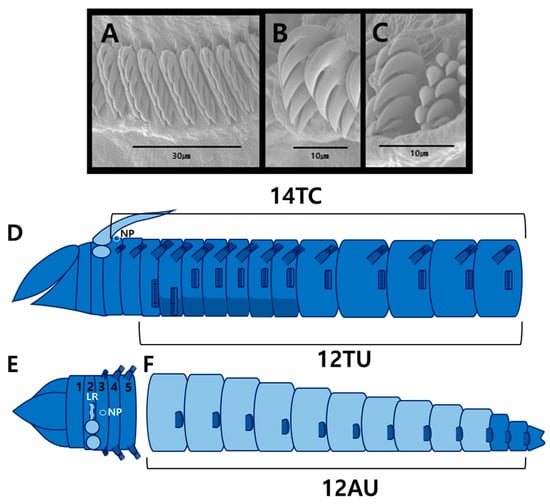

Figure 6.

Auchenoplax worsfoldi Jirkov & Leontovich, 2013 (specimen MABIK NA00124663): (A) entire body, dorsal view; (B) entire body, ventral view; (C) prostomium, dorsal view; (D) buccal tentacle; (E) branchia, dorsal view; (F) thoracic uncinigers 1–3, ventral view; (G) thorax–abdomen junction, lateral view (last thoracic and first abdominal segments); (H) pygidium; (I) bilimbate capillary chaetae from TC5; (J) uncini from TU7, frontal view; (K) uncini from TU8, lateral view; (L) uncini from AU5, lateral view. Abbreviations: AU, abdominal unciniger; Br, branchia; LR, low ridge; NP, nephridial papillae; TC, thoracic chaetiger; TU, thoracic unciniger; VS, ventral shields.

Figure 7.

Auchenoplax worsfoldi Jirkov & Leontovich, 2013 (specimen MABIK NA00124663) scanning electron micrographs and methyl green staining patterns: (A) uncini from TU1, frontal view; (B) uncini from TU2, lateral view; (C) uncini from AU2, lateral view; (D) MGSP schematic of thorax, lateral view; (E) anterior end, dorsal view (numbers 1–5 indicate segment numbers); (F) abdomen, lateral view. Abbreviations: AU, abdominal unciniger; LR, low ridge; NP, nephridial papillae; TC, thoracic chaetiger; TU, thoracic unciniger.

3.4.2. Material Examined

Six specimens (MABIK NA00124594–99): Jeollanam-do, Republic of Korea, 34°4′58.03″ N, 127°2′54.6″ E, 49 m depth, 1 November 2009, collected by grab. Seven specimens (MABIK NA00124620–24, NA00124662–64): Jeollanam-do, Republic of Korea, 34°4′58.02–04″ N, 127°2′54.57–61″ E, 49 m depth, 1 February 2010, collected by grab. Two specimens (MABIK NA00124947, NA00124965): Jeollanam-do, Republic of Korea, 34°4′49.22″ N, 126°54′47.48″ E, 48 m depth, 1 February 2010, collected by grab. One specimen (MABIK NA00125000): Jeollanam-do, Republic of Korea, 34°5′16.29″ N, 126°44′18.2″ E, 47 m depth, 1 November 2009, collected by grab. Two specimens (MABIK NA00125032, NA00125046): Jeollanam-do, Republic of Korea, 34°5′16.28–29″ N, 126°44′18.2″ E, 47 m depth, 1 February 2010, collected by grab. One specimen (JUMA_20250804_001): Station YE05, 34°0′0″ N, 126°00′0″ E, 73 m depth, 28 June 2024, collected by Smith-McIntyre grab.

3.4.3. Description

Description based on complete specimen (MABIK NA00124663), 18.4 mm long, 0.9 mm wide at thorax (Figure 6A).

Prostomium unilobed, triangular; paired glandular ridges and nuchal ridges absent (Figure 6C). Eyespots absent. Buccal tentacles smooth, with vertical grooves (Figure 6D). Paleae absent; thus TC1 starting from segment 3 (Figure 6A–C,E). Two pairs of smooth branchiae on SG2. Branchiae approximately 3–4 times as long as prostomium. Branchial groups connected by low ridge; branchiophores not fused at base (Figure 6E). Two pairs of branchial groups spaced apart by more than twice width of branchia (Figure 6E).

Thorax longer than abdomen and of similar width (Figure 6A). Thoracic segments sharply subdivided into two regions; anterior segments (TC1–TC10) twice as short as posterior (Figure 6A,B). Fourteen thoracic chaetigers (TCs). Notopodia present on TC1–TC14. Notopodia of TC1–TC2 reduced (Figure 7D,E). Subsequent notopodia (TC3–TC14) well developed. Notochaetae simple, spinulose bilimbate capillaries, tapering to slender tips (Figure 6I). Tuberculate ventral cirri absent. Single nephridial papilla present between first pair of notopodia (Figure 6E). Thoracic uncinigers (TUs) starting from TC3, thus 12 thoracic uncinigers (TU1–TU12). Anterior two neuropodia (TU1, TU2) modified, approximately twice the size of other neuropodia; TU2 displaced toward ventral midline (Figure 6F). Ventral shields well-developed until TU7, weakly developed on TU8, absent from TU9 (Figure 6B). Thoracic uncini with four to six teeth arranged in two rows (Figure 6J,K and Figure 7A,B).

Abdomen shorter, with twelve uncinigers (AU1–AU12). First two uncinigers (AU1–AU2) with tori; subsequent uncinigers (AU3–AU12) with pinnules. Neuropodial dorsal cirri and papillae absent (Figure 6G). Abdominal uncini with four to five teeth arranged in two vertical rows (Figure 6L and Figure 7C). Pygidium papillated; paired lobes or cirri absent (Figure 6H).

3.4.4. Methyl Green Staining Patterns

Thoracic region stained more intensely than abdominal region overall (Figure 7D). Base of branchiae darkest blue, while surrounding tissue and branchiae light blue (Figure 7D,E). Thoracic notopodia dark blue, and ventral shields of TU2–TU7 also dark blue (Figure 7D). Abdominal neuropodia darker blue than adjacent regions (Figure 7F). Pygidium and posterior end of abdomen blue (Figure 7F).

3.4.5. Remarks

The Korean specimens, including those previously labeled Auchenoplax crinita in the MABIK collection, correspond to Auchenoplax worsfoldi. The identification is confirmed based on the triangular prostomium, a single nephridial papilla located dorsally on chaetiger 1 (TC1), the modified first two thoracic uncinigers, and twelve abdominal segments (AU1–AU12).

The MGSP of A. worsfoldi is reported here for the first time, providing new diagnostic information (e.g., intense staining of the thoracic dorsum and branchial bases). This species was originally described from the Bay of Biscay and is now known to occur in the East China Sea and the southern coast of Korea at depths of 47–73 m.

3.5. Genus Phyllocomus Grube, 1877 [28]

3.5.1. Phyllocomus chinensis Sui & Li, 2017 (Figure 8 and Figure 9) [29]

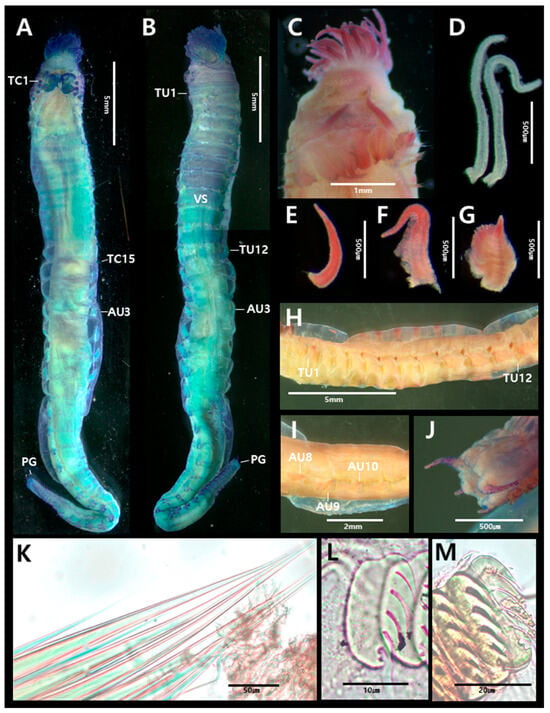

Figure 8.

Phyllocomus chinensis Sui & Li, 2017 (specimen MABIK NA00125036): (A) entire body, dorsal view; (B) entire body, ventral view; (C) prostomium, dorsal view; (D) buccal tentacle; (E) smooth branchiae from segment 3; (F) one low lamellae branchiae from segment 2; (G) two rows lamellae branchiae from segment 4 and 5, (H) thoracic uncinigers 1–12, lateral view; (I) abdominal uncinigers, lateral view; (J) pygidium; (K) bilimbate capillary chaetae from TC13; (L) uncini from TU13, lateral view; (M) uncini from AU3, lateral view. Abbreviations: AU, abdominal unciniger; TC, thoracic chaetiger; TU, thoracic unciniger; VS, ventral shields.

Figure 9.

Phyllocomus chinensis Sui & Li, 2017 (specimen MABIK NA00125036) scanning electron micrographs and methyl green staining patterns: (A) uncini from TU1, frontal view; (B) uncini from AU1, lateral view; (C) MGSP schematic of thorax, lateral view; (D) anterior end, dorsal view (numbers 1–5 indicate segment numbers); (E) branchiae of three morphological types; (F) abdomen, lateral view. Abbreviations: AU, abdominal unciniger; TC, thoracic chaetiger; TU, thoracic unciniger.

3.5.2. Material Examined

Two specimens (MABIK NA00155388): Jeju-si Chuja-myeon, Jeju Special Self-Governing Province, Republic of Korea, 33°56′38.5″ N, 126°19′39.7″ E, 8 m depth, 27 November 2012, gear not recorded. Two specimens (MABIK NA00124555–56): Jeollanam-do, Republic of Korea, 34°4′14.98–14.99″ N, 126°23′19.24″ E, 48 m depth, 1 November 2009, collected by grab. One specimen (MABIK NA00125036): Jeollanam-do, Republic of Korea, 34°5′16.29″ N, 126°44′18.2″ E, 47 m depth, 1 February 2010, collected by grab. One specimen (MABIK NA00115874): Geunnam-myeon, Uljin-gun, Gyeongsangbuk-do, Republic of Korea, 36°56′56.84″ N, 129°25′18.73″ E, depth not recorded, 12 August 2011, collected by grab. Three specimens (MABIK NA00136471–73): Sowon-myeon, Taean-gun, Chungcheongnam-do, Republic of Korea, 36°46′53.42″ N, 126°7′13.39–41″ E, depth not recorded, 7 July 2013, collected by grab.

3.5.3. Description

Description based on complete specimen (MABIK NA00125036), 33 mm long, 2.7 mm wide at thorax (Figure 8A).

Prostomium unilobed, rounded; glandular ridges or nuchal ridges absent (Figure 8C). Eyespots present but not easily observed. Buccal tentacles smooth (Figure 8D). Paleae absent; thus TC1 starting from segment 3 (Figure 8A–C). Four pairs of branchiae on SG2–4 (Figure 9D). Branchiae of three forms: pair from SG2 with one row of lamellae (Figure 8F); pair from SG3 smooth (Figure 8E); and two pairs from SG4–5 with two rows of lamellae (Figure 8G).

Thorax shorter than abdomen and of similar width (Figure 8A). Fifteen thoracic chaetigers (TCs). Notopodia of TC1–TC3 reduced. Subsequent notopodia (TC4–TC15) well developed, up to twice as long as wide. Notochaetae simple, spinulose bilimbate capillaries, tapering to slender tips (Figure 8K). Tuberculate ventral cirri absent (Figure 8H). Thoracic neuropodia (uncinigers) present from TC4 to TC15, thus 12 thoracic uncinigers (TU1–TU12). Neuropodial tori gradually decrease in size toward posterior thorax. Ventral shields well developed until TU9, weakly developed on TU11, absent from TU12 (Figure 8B). Thoracic uncini with five teeth arranged in one row (Figure 8L and Figure 9A,B).

Abdomen longer than thorax, with 31 uncinigers (AU1–AU31). Abdominal uncinigers with pinnules and papillary dorsal cirri (Figure 8I). Digitiform rudimentary notopodia absent. Abdominal uncini with five teeth arranged in one vertical row above rostrum (Figure 8M and Figure 9B). Pygidium papillated, with two pairs of lateral cirri; dorsal pair long, ventral pair short (Figure 8J).

3.5.4. Methyl Green Staining Patterns

Thoracic region stained slightly more intensely than abdomen overall, with some areas appearing purple (Figure 9C). Prostomium stained light blue. Among branchiae, the smooth pair from SG 3 stained the darkest blue, whereas lamellate branchiae stained blue (Figure 9C–E). Thoracic notopodia stained dark blue (Figure 9C), and parts of the ventral shields stained violet (Figure 9C). Abdomen stained light blue (Figure 9F). Abdominal neuropodia stained dark blue, but areas around uncini stained light blue; abdominal neuropodia of posterior end and pygidium stained dark blue (Figure 9F).

3.5.5. Remarks

The Korean specimens, including those previously labeled Phyllocomus hiltoni in the MABIK collection, correspond well to Phyllocomus chinensis. The identification is confirmed by the unilobed prostomium, four pairs of branchiae of three distinct types (three lamellate, one smooth), and the presence of dorsal papillae on the abdominal neuropodia.

The Korean specimens agree with P. chinensis, exhibiting only minor variation: Korean specimens possess 30–33 abdominal segments, slightly fewer than the 34 segments reported for the Chinese-type material. The MGSP of P. chinensis is reported here for the first time, providing new diagnostic characteristics (e.g., differential staining of the smooth vs. lamellate branchiae). This species was previously known from the Yellow Sea near China and is now confirmed along the Korean coast at depths of 8–48 m.

4. Discussion

4.1. Systematic Re-Assessment and Clarification of the Korean Ampharetidae Fauna

This study provides the first records of four ampharetid species from Korean waters: Amphicteis chinensis Sui & Li, 2017, Anobothrus nataliae Jirkov, 2009, Auchenoplax worsfoldi Jirkov & Leontovich, 2013, and Phyllocomus chinensis Sui & Li, 2017. More significantly, this research serves as a critical systematic re-assessment of specimens deposited in the National Marine Biodiversity Institute of Korea (MABIK). Our findings reveal that the diversity of Korean Ampharetidae has been significantly underestimated due to long-standing misidentifications, a challenge compounded by reliance on traditional keys and difficulties in observing key morphological features.

The most prominent case of this confusion involves Ampharete arctica Malmgren, 1866, which has long been reported as a dominant species in ecological surveys around Jeju Island and the East China Sea. This study confirms, through the re-examination of both historical voucher specimens and newly collected field material, that these records are highly likely misidentifications of Anobothrus nataliae. The primary cause for this error appears to be a reliance on the shared trilobed prostomium structure, a problem likely exacerbated by the damage or loss of other diagnostic features during collection, sieving, or fixation. Furthermore, as the genus Anobothrus had not been officially recorded from Korea, it was likely unrecognized by local ecological researchers among the many ampharetid genera. This lack of prior records, combined with crucial diagnostic features of A. nataliae (such as the faint thoracic bands on TU3 and TU9) that are extremely difficult to observe without staining, led researchers to default to the better-known Ampharete. This finding corrects our understanding of the dominant ampharetid fauna in this region.

A similar systematic clarification was applied to other MABIK specimens. Specimens that had been provisionally labeled as Auchenoplax crinita Ehlers, 1887, a species not yet formally recorded from Korea, were conclusively identified by this study as Auchenoplax worsfoldi. While generic identification based on modified TU1 and TU2 was correct, subtle but critical species-level differences were overlooked—specifically, differences in prostomial shape and the count of abdominal uncinigers (12 vs. 14). Likewise, all four examined specimens labeled Phyllocomus hiltoni (Chamberlin, 1919) (also not yet formally recorded from Korea) were confirmed to be P. chinensis, distinguished by a subtle species-level character of their abdominal dorsal cirri (papillae vs. long cirri).

The re-examination of 32 specimens, which had been labeled as Amphicteis gunneri (M. Sars, 1835), Amphicteis hwanghaiensis Wang, Sui, Li, Hutchings & Nogueira, 2020, Amphicteis sp., or unidentified Ampharetidae, further highlights this complexity. Not a single specimen matched the modern redescription of A. gunneri [19]. Instead, the material was found to be a complex of other species, including Paramphicteis weberi (Caullery, 1944) [7], Amphicteis aff. glabra Moore, 1906 [11], and the newly recorded Amphicteis chinensis. This confirms that historical records of A. gunneri in Korea require re-evaluation. Such widespread historical misidentification is likely attributable to two factors: (1) the past reliance on an overly broad, ‘cosmopolitan’ definition of A. gunneri before its modern revision [19], and (2) the inherent difficulty in separating damaged specimens of Paramphicteis from Amphicteis. These two genera share a highly similar body plan, including 18 thoracic chaetigers (14 uncinigers) and 4 pairs of branchiae. However, they are separated by fundamental generic-level characteristics: Paramphicteis possesses pinnate buccal tentacles and foliose branchiae [7], whereas Amphicteis has smooth tentacles and cirriform branchiae [11,19]. These diagnostic features—especially the branchiae—are notoriously prone to damage or loss during sample collection. With these critical generic-level diagnostics missing, past Korean researchers likely relied only on the remaining, ambiguous features (e.g., presence of paleae, segment counts), leading to the erroneous identification of Paramphicteis weberi as the then-only-reported Amphicteis gunneri. Furthermore, distinguishing congeneric species within Amphicteis is inherently difficult. Misidentifications likely arose from failing to observe critical species-level characteristics that are often subtle or easily obscured, such as the exact branchial arrangement (which is difficult to discern in damaged or contracted specimens), subtle paleal characteristics (e.g., exact count, relative length, or the presence of basal lobes), or the presence/absence of easily missed eyespots. It is the overlooking of these subtle, species-specific characteristics [11] that likely led to the historical misidentification of this entire species complex as A. gunneri in Korean waters.

4.2. The Value of MGSP and SEM as Essential Tools for Ampharetid Systematics

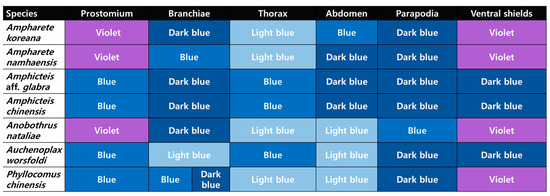

This study’s ability to resolve these complex misidentifications stems from the application of precise morphological techniques that are often overlooked: methyl green staining patterns (MGSPs) and scanning electron microscopy. The MGSP analysis, reported here for the first time for all four species, proved to be an invaluable diagnostic tool. We identified consistent inter-generic or specific differences among the Korean specimens, particularly in the staining patterns of the prostomium and ventral shields (e.g., Ampharete/Anobothrus stained purple; Amphicteis/Auchenoplax stained blue; Phyllocomus showed a mixed pattern with a blue prostomium and purple ventral shields). In addition, distinct species-level differences in MGSP by body part were also confirmed among the studied taxa (Figure 10), with the exception of the two Amphicteis species (which were similar). This utility of the MGSP for species-level diagnostics is, in fact, well-documented across numerous other polychaete families, such as Capitellidae, Magelonidae, Spionidae, and Terebellidae [16,30,31,32,33]. Furthermore, the MGSP illuminates cryptic structures essential for identification; for instance, the diagnostic ridges on TU3 and TU9 of Anobothrus nataliae and the nephridial papillae of Auchenoplax worsfoldi were stained distinctly. This demonstrates that the MGSP can serve as a rapid, cost-effective auxiliary key for genus- or species-level identification, especially for specimens with damaged or missing key features (such as branchiae).

Figure 10.

Simplified MGSP patterns of seven Ampharetidae species from Korea.

Similarly, SEM observations were critical for resolving systematic ambiguities unresolved by light microscopy. While the uncini of three species (1–2 rows of teeth) were relatively clear, the complex structure of Anobothrus nataliae uncini (3–4 rows in the abdomen) was impossible to accurately interpret without SEM. SEM revealed the true arrangement and tooth count, which are fundamental diagnostic characteristics. This methodological limitation likely contributed to past systematic confusion, as light microscopy observation alone is often insufficient or misleading for these features.

4.3. Conclusions

This research demonstrates that the diversity of Korean Ampharetidae is greater than previously known and rectifies significant historical misidentifications within national collections. It confirms that a reliance on traditional keys or singular morphological traits (like prostomium shape) is insufficient for this family. We strongly advocate that a modern morphological framework, one that integrates detailed analyses of the MGSP and SEM uncini ultrastructure, is essential for the accurate assessment of ampharetid diversity.

A revised key to the Ampharetidae species from Korea.

| 1. Prostomium unilobed. Paleae absent. Four pairs of branchiae, including 3–4 lamellate pairs.................................................................................... Phyllocomus chinensis Sui & Li, 2017 |

| – Prostomium trilobed. Branchiae cirriform............................................................................. 2 |

| 2. Prostomium without longitudinal glandular ridges or nuchal organs............................. 3 |

| – Prostomium with distinct longitudinal glandular ridges and nuchal organs.................. 7 |

| 3. Anterior two thoracic uncinigers modified or transverse dorsal ridges.......................... 4 |

| – Thorax without modified uncinigers or dorsal ridges......................................................... 5 |

| 4. Anterior two thoracic uncinigers modified, enlarged, and ventrally shifted; 12 abdominal uncinigers .................................... Auchenoplax worsfoldi Jirkov & Leontovich, 2013 |

| – Thorax with transverse dorsal ridges (faint on TU3, conspicuous on TU9); all branchiae fused at base ............................................................................. Anobothrus nataliae Jirkov, 2008 |

| 5. Thorax with 14 chaetigers........................................................................................... 6 |

| – Thorax with 17 chaetigers..................................... Amphisamytha japonica Hessle, 1917 |

| 6. Paleae present; 12 abdominal uncinigers; pygidium with eyespots........................... |

| ..................................................................... Ampharete koreana Kim, Kim & Jeong, 2025 |

| – Paleae absent; 16 abdominal uncinigers .............................................................. ......................................................... Ampharete namhaensis Kim, Kim & Jeong, 2025 |

| 7. Buccal tentacles pinnate; branchiae foliose.............. Paramphicteis weberi (Caullery, 1944) |

| – Buccal tentacles smooth; branchiae cirriform...................................................................... 8 |

| 8. A large, distinct lobe present posterior to paleae; 16 abdominal uncinigers............... .........................................................................Amphicteis chinensis Sui & Li, 2017 |

| – No distinct lobe posterior to paleae; 15 abdominal uncinigers; fewer than 10 pairs of paleae .................................................................................. Amphicteis aff. glabra Moore, 1906 |

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.R.K. and M.-K.J.; methodology: S.K. and M.-K.J.; formal analysis: J.R.K.; investigation: Y.B.H., S.K. and J.R.K.; visualization: Y.B.H., J.R.K. and M.-K.J.; resources: M.-K.J.; supervision: M.-K.J.; writing—original draft preparation: J.R.K.; writing—review and editing: M.-K.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the management of the Marine Fishery Bio-resources Center (2025) funded by the National Marine Biodiversity Institute of Korea (MABIK), and by the project titled “Aquaculture habitat suitability for climate change adaptation”, funded by the National Institute of Fisheries Science, Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, South Korea (grant number R2026047).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous reviewers and the editor, who made constructive and invaluable suggestions and comments. We also thank the captains and crews of Chonnam National University’s training ship “Sae Dong Baek” and the research vessel “Cheonggyeong” for their support at sea.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| MABIK | National Marine Biodiversity Institute of Korea |

| AU | abdominal unciniger |

| Br | branchia |

| CB | circular band |

| DR | dorsal ridge |

| DRN | digitiform rudimentary notopodia |

| JUMA | Chonnam National University Specimen Collection |

| LM | light microscopy |

| LR | low ridge |

| MGSP | methyl green staining pattern |

| NO | nuchal organs |

| NP | nephridial papillae |

| PG | pygidium |

| PL | paleae |

| SEM | scanning electron microscopy |

| SG | segment |

| TC | thoracic chaetiger |

| TU | thoracic unciniger |

| TVC | tuberculate ventral cirri |

| VS | ventral shields |

References

- Read, G.; Fauchald, K. (Eds.) World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS): Ampharete Malmgren, 1866. Available online: https://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=981 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Day, J.H. A Review of the Family Ampharetidae (Polychaeta); South African Museum: Cape Town, South Africa, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Jirkov, I.A. Discussion of taxonomic characters and classification of Ampharetidae (Polychaeta). Ital. J. Zool. 2011, 78, 78–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Vallejo, S.I.; Hutchings, P. A review of characters useful in delineating ampharetid genera (Polychaeta). Zootaxa 2012, 3402, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, E. Taxonomic studies on polychaetous annelids in Korea. Res. Bull. Hyosung Women’s Univ. 1982, 24, 745–913. [Google Scholar]

- Paik, E. Illustrated encyclopedia of fauna and flora of Korea. Polychaeta 1989, 764, 102. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, G.H.; Yoon, S.M.; Min, G.S. A New Record of Paramphicteis weberi (Polychaeta: Terebellida: Ampharetidae) in Korean Fauna. Anim. Syst. Evol. Divers. 2021, 37, 165–170. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Fisheries Science. 2025 National List of Marine Species; Report No. NIFS-2025-SpeciesList; National Institute of Fisheries Science: Busan, Republic of Korea, 2025.

- Gunton, L.M.; Kupriyanova, E.; Alvestad, T. Two new deep-water species of Ampharetidae (Annelida: Polychaeta) from the eastern Australian continental margin. Rec. Aust. Mus. 2020, 72, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunton, L.M.; Kupriyanova, E.K.; Alvestad, T.; Avery, L.; Blake, J.A.; Biriukova, O.; Böggemann, M.; Borisova, P.; Budaeva, N.; Burghardt, I. Annelids of the eastern Australian abyss collected by the 2017 RV ‘Investigator’voyage. ZooKeys 2021, 1020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-R.; Kim, D.-H.; Jeong, M.-K. First Report of Three Ampharetinae Malmgren, 1866 Species from Korean Subtidal Waters, Including Genetic Features of Histone H3 and Descriptions of Two New Species. Diversity 2025, 17, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, J.P. The re-establishment of Amphicteis midas (Gosse, 1855) and redescription of the type material of A. gunneri (M. Sars, 1835) (Polychaeta: Ampharetidae). Sarsia 2011, 70, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parapar, J.; Helgason, G.V.; Jirkov, I.; Moreira, J. Taxonomy and distribution of the genus Amphicteis (Polychaeta: Ampharetidae) collected by the BIOICE project in Icelandic waters. J. Nat. Hist. 2011, 45, 1477–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiaparelli, S.; Jirkov, I.A. A reassessment of the genus Amphicteis Grube, 1850 (Polychaeta: Amphaetidae) with the description of Amphicteis teresae sp. nov. from Terra Nova Bay (Ross Sea, Antarctica). Ital. J. Zool. 2016, 83, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.Y.; Kim, G.; Soh, H.Y.; Shin, H.C. Community Structure of Macrobenthic Polychaetes and its Health Status (Assessed by Two Biotic Indices) on the Adjacent Continental Shelf of Jeju Island, in Summer of 2020. Ocean Polar Res. 2022, 44, 113–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.-H.; Kwon, I.-Y.; Soh, H.-Y.; Jeong, M.-K. First Report on Three Lesser-Known Magelona Species from Korean Waters: Details of All Thoracic Chaetigers and Methyl Green Staining Patterns. Diversity 2024, 16, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winsnes, I.M. The use of methyl green as an aid in species discrimination in Onuphidae (Annelida, Polychaeta). Zool. Scr. 1985, 14, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holthe, T. Evolution, Systematics, and Distribution of the Polychaeta Terebellomorpha, with a Catalogue of the Taxa and a Bibliography; NTNU Vitenskapsmuseet: Trondheim, Norway, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Jirkov, I.A. (Ed.) Polychaeta of the North Polar Basin; Yanus-K: Moscow, Russia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Grube, A.E. Die Familien der Anneliden: Mit Angabe ihrer Gattungen und Arten; Nicolaischen Buchhandlung: Berlin, Germany, 1850. [Google Scholar]

- Sui, J.; Li, X. A new species of the genus Amphicteis (Polychaeta: Ampharetidae) from China. Chin. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2017, 35, 821–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinsen, G.M.R. Systematisk-Geografisk Oversigt over den Nordiske Annulata, Gephyrea, Chætognathi og Balanoglossi; B. Lunos Kgl. Hof-bogtrykkeri: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1884. [Google Scholar]

- Jirkov, I. Revision of Ampharetidae (Polychaeta) with modified thoracic notopodia. Invertebr. Zool. 2009, 5, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, J.; Li, X. Review of Anobothrus (Polychaeta: Ampharetidae) from China. Chin. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2013, 31, 632–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, E.H. Anneliden—Ausbeute S.M.S. Gazelle; Printed for the Museum of Comparative Zoology; Harvard College: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1887. [Google Scholar]

- Jirkov, I.A.; Leontovich, M.K. Identification keys for Terebellomorpha (Polychaeta) of the eastern Atlantic and the North Polar Basin. Invertebr. Zool. 2013, 10, 217–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, J.; Li, X. A new record of Auchenoplax Ehlers, 1887 (Polychaeta: Ampharetidae) from the East China Sea. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2018, 37, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grube, A.E. Anneliden—Ausbeute S.M.S. Gazelle; Monatsbericht der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 1877; pp. 509–554. [Google Scholar]

- Sui, J.; Li, X. A new species of Phyllocomus Grube, 1878 from the Yellow Sea, China (Annelida, Ampharetidae). Zookeys 2017, 676, 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jeong, M.-K.; Soh, H.Y.; Suh, H.-L. Three new species of Heteromastus (Annelida, Capitellidae) from Korean waters, with genetic evidence based on two gene markers. ZooKeys 2019, 869, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-E.; Lee, G.H.; Min, G.-S. First Record of Magelona parochilis (Annelida: Magelonidae) in South Korea. Anim. Syst. Evol. Divers. 2022, 38, 149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, G.H.; Yoon, S.M.; Min, G.-S. First record of two Pseudopolydora (Annelida: Spionidae) species in Korea. Anim. Syst. Evol. Divers. 2022, 38, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Jirkov, I. Review of the European Amphitrite (Polychaeta: Terebellidae) with description of two new species. Invertebr. Zool. 2020, 17, 311–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).