Prediction of Suitable Habitats for Tibetan Medicinal Gentiana Plants of Jieji- and Bangjian-Type Gentianas Based on the MaxEnt Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

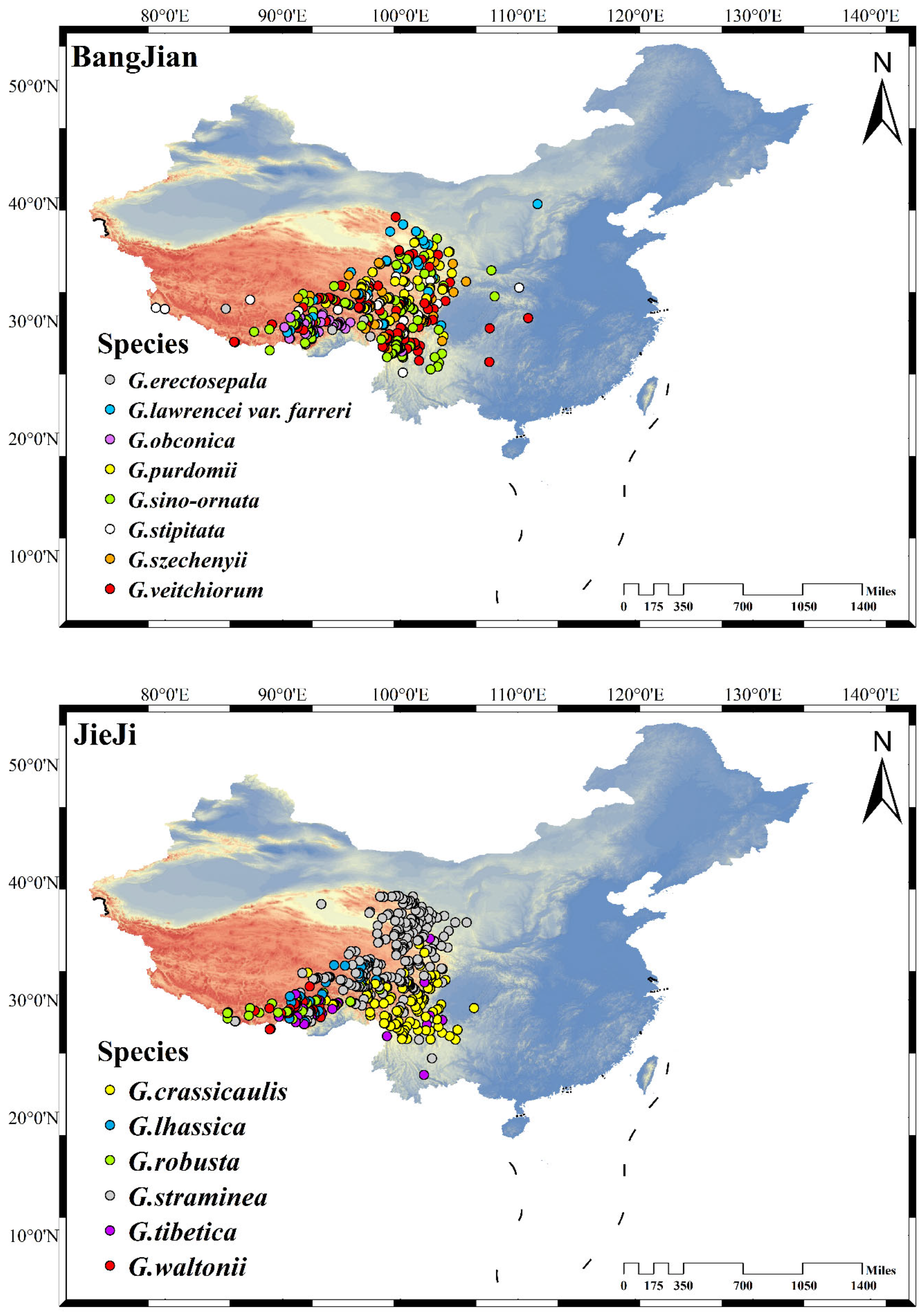

2.1. Biological Characteristics of the Main Source Species of “Jieji” and “Bangjian” Types

2.2. Distribution Data Acquisition and Filtering

2.3. Acquisition and Selection of Environmental Variables

2.4. Model Parameter Optimization

2.5. Data Processing

3. Results

3.1. Model Optimization and Evaluation Results

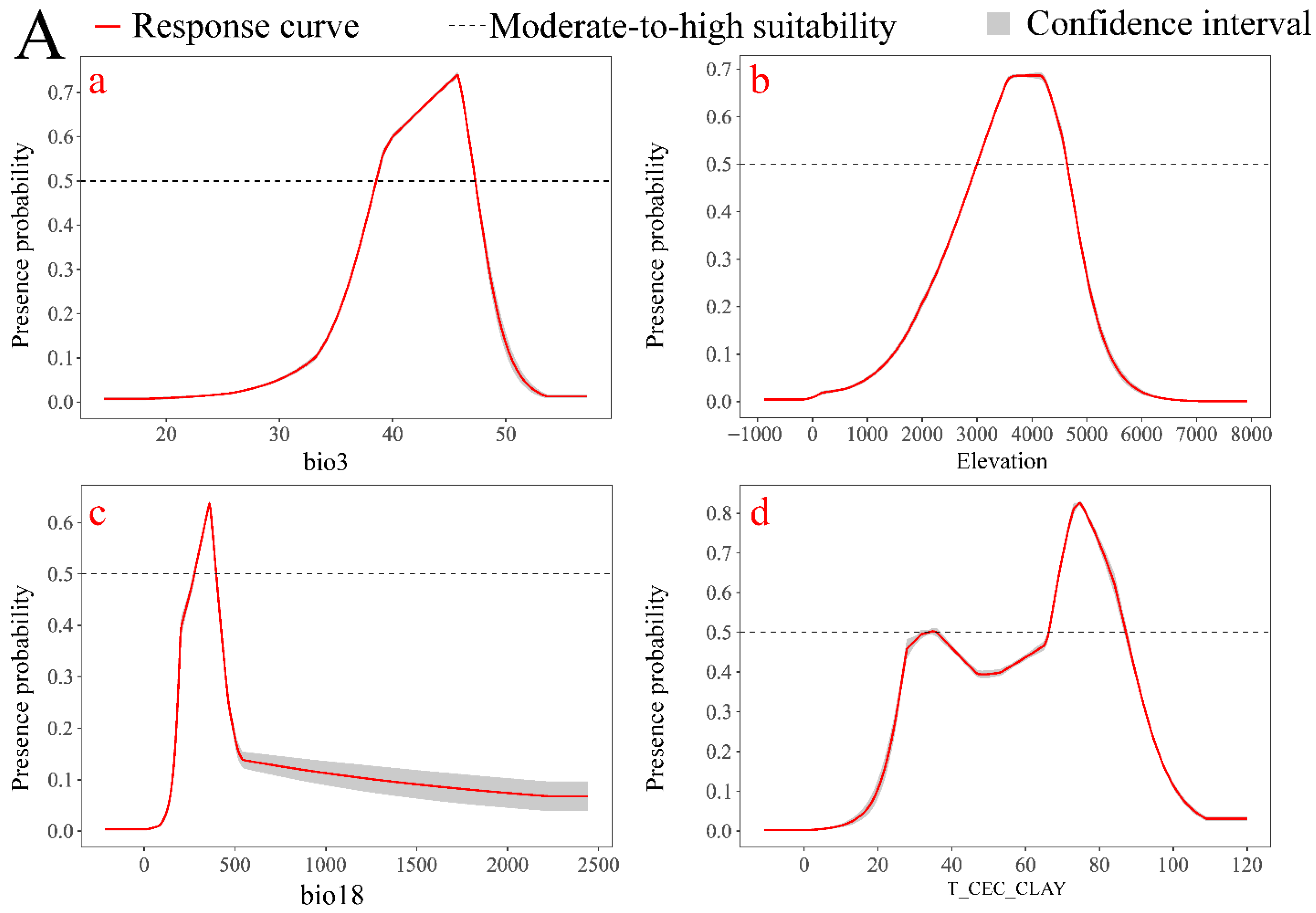

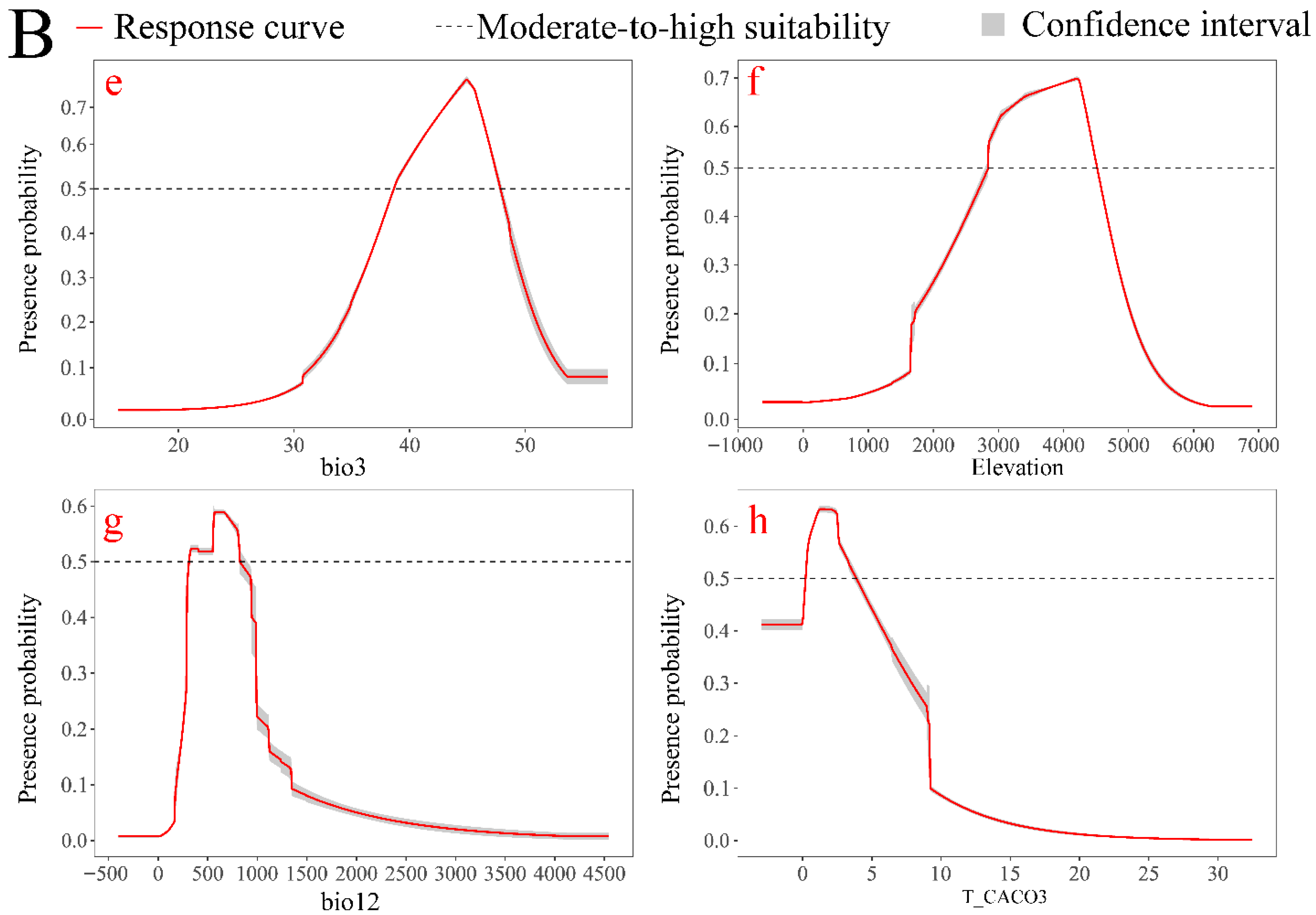

3.2. Environmental Variables and Response Curves

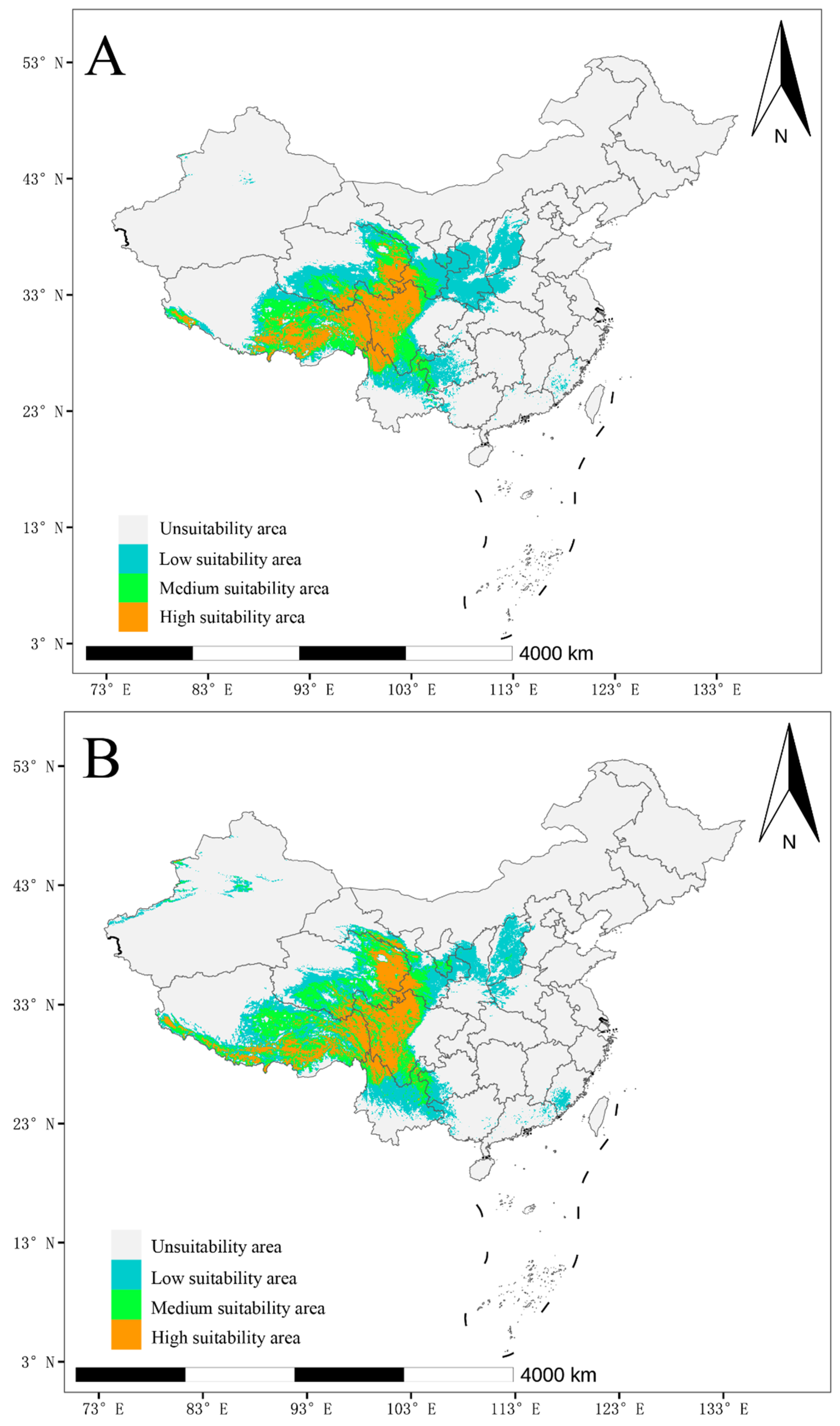

3.3. Suitable Habitat Area

3.4. Dynamic Changes in Suitable Areas Under Different Climate Scenarios

3.5. Center of Mass Migration

4. Discussion

4.1. Model Performance and Factor Analysis

4.2. Dominant Environmental Drivers

4.3. Climate Change Impacts and Habitat Dynamics

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

4.5. Conservation Implications

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Utilizing the Maximum Entropy (MaxEnt) model with twelve selected environmental factors, this study found that altitude, temperature, and precipitation are the primary dominant factors determining the distribution of the Tibetan medicinal herbs Bangjian and Jieji.

- (2)

- Under current climatic conditions, the total suitable habitat for Bangjian and Jieji was estimated to be 208.86 × 104 km2 and 211.70 × 104 km2, respectively. The highly suitable areas for both are primarily concentrated in the southeastern part of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau.

- (3)

- Under future climate scenarios, the suitable habitat for Jieji is projected to contract, showing a moderate expansion trend towards Central China only under the SSP126 scenario. In contrast, the suitable habitat for Bangjian is generally expected to expand, except under the SSP585 scenario. The centroid of suitable habitats for both types is projected to shift eastward.

- (4)

- Based on future climate projections, JieJi-class Tibetan medicines exhibit higher climate sensitivity compared to BangJian-class varieties, warranting prioritized conservation measures such as the establishment of seed banks and nature reserves.

- (5)

- These findings establish a scientific basis for understanding the potential impacts of climate change on the distribution of Gentiana-based Tibetan medicinal resources and offer critical insights to inform ecological conservation strategies and future research.

- (6)

- Future research should aim to integrate anthropogenic factors and develop species-specific distribution models for individual medicinal plants.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mi, X.; Feng, G.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L.; Corlett, R.T.; Hughes, A.C.; Pimm, S.; Schmid, B.; Shi, S.; et al. The global significance of biodiversity science in China: An overview. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2021, 8, nwab032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, D.; Zhou, B.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Su, Q.; Yan, X. MaxEnt Modeling of the Impacts of Human Activities and Climate Change on the Potential Distribution of Plantago in China. Biology 2025, 14, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zu, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, X.; Lenoir, J.; Shrestha, N.; Lyu, T.; Luo, A.; Li, Y.; Ji, C.; Peng, S.; et al. Upward shift and elevational range contractions of subtropical mountain plants in response to climate change. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 783, 146896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Ruiz, E.P.; Lacher, T.E., Jr. Climate change, range shifts, and the disruption of a pollinator-plant complex. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, X.; Shen, M.; Wu, C.; Peñuelas, J.; Ciais, P.; Zhang, J.; Freeman, C.; Palmer, P.I.; Liu, B.; Henderson, M.; et al. Critical role of water conditions in the responses of autumn phenology of marsh wetlands to climate change on the Tibetan Plateau. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inouye, D.W. Effects of climate change on alpine plants and their pollinators. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2020, 1469, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, X.; Zhang, F.; Gao, Q.; Xing, R.; Chen, S. A Review on the Ethnomedicinal Usage, Phytochemistry, and Pharmacological Properties of Gentianeae (Gentianaceae) in Tibetan Medicine. Plants 2021, 10, 2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Editorial Committee of Flora of China. Chinese Academy of Sciences. Flora of China; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Favre, A.; Michalak, I.; Chen, C.H.; Wang, J.C.; Pringle, J.S.; Matuszak, S.; Sun, H.; Yuan, Y.M.; Struwe, L.; Muellner-Riehl, A.N. Out-of-Tibet: The spatio-temporal evolution of Gentiana (Gentianaceae). J. Biogeogr. 2016, 43, 1967–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Northwest Institute of Plateau Biology; Chinese Academy of Sciences. Tibetan Medicine Records; Qinghai People’s Publishing House: Xining, China, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, D.S. Chinese Tibetan Materia Medica; Nationalities Publishing House: Beijing, China, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, D. Xin Xiu Jing Zhu Ben Cao; Sichuan Science and Technology Press: Chengdu, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, L.; Zou, X.; He, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, G.; Gu, R.; Jiang, G. Varieties Textual Research of Tibetan Medicine “Jijie”. Mod. Tradit. Chin. Med. Mater. Medica-World Sci. Technol. 2022, 24, 3718–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Gu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zeweng, Y.; Jiangyong, S.; Zhang, J. Varieties textual research on “Bangjian”: Traditional Tibetan medicine including blue, black and variegated flowers. China J. Chin. Mater. Medica 2018, 43, 3404–3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Fan, J.; Zhong, S.; Gu, R. Tibetan medicine Bang Jian: A comprehensive review on botanical characterization, traditional use, phytochemistry, and pharmacology. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1295789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Zhang, D.; Yang, J.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, W. Analysis and Comparison of Suitable Areas of Cypripedium tibeticum and Cypripedium flavumin China under Climate Change Scenario. Acta Agrestia Sin. 2025, 33, 3372–3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Jiang, H.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yan, W.; Dang, H.; Cao, K.; Yang, N. Prediction of Potential Suitable Habitats for Ulmus Species in Inner Mongolia under Climate Change. For. Grassl. Resour. Res. 2025, 01, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, S.J.; Anderson, R.P.; Schapire, R.E. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distribution. Ecol. Model. Ecol. Model. 2013, 190, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J. Correlation Analysis Between Ophiocordyceps Sinensis Population Metabolomics and Environmental Fact; Xizang University: Xizang, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Wang, J.; Lv, S.; Zhang, X. Simulation of the potential distribution patterns of Picea crassifolia in climate change scenarios based on the maximum entropy (Maxent) model. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2019, 39, 5232–5240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, P.; Wang, L.; Qiu, D.; Liang, W.; Cheng, J.; Wang, H.; Guo, F.; Chen, Y. Evaluation of the environmental factors influencing the quality of Astragalus membranaceus var. mongholicus based on HPLC and the Maxent model. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBIF.org. GBIF Occurrence Download. Available online: https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/download/0006209-250525065834625 (accessed on 29 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- Fu, P.; Ya, H.; Liu, Q.; Cai, H.; Chen, S. Out of Refugia: Population Genetic Structure and Evolutionary History of the Alpine Medicinal Plant Gentiana lawrencei var. farreri (Gentianaceae). Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, P.; Sun, S.; Khan, G.; Dong, X.; Tan, J.; Favre, A.; Zhang, F.; Chen, S. Population subdivision and hybridization in a species complex of Gentiana in the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Ann. Bot. 2020, 125, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Peng, H.; Bi, H.; Lu, Z.; Wan, D.; Wang, Q.; Mao, K. Genetic homogenization of the nuclear ITS loci across two morphologically distinct gentians in their overlapping distributions in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 34244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, A.C.P.; Cavalcante, A.M.B. Accurate species distribution models: Minimum required number of specimen records in the Caatinga biome. An. Acad. Bras. Ciências 2023, 95, e20201421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Long, Z.; Lu, X.; Song, Z.; Miao, Q. Habitat suitability of Corydalis based on the optimized MaxEnt model in China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 43, 10345–10362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Yao, J.; Wu, T.; Wu, F.; Li, J. Improved simulation of Antarctic sea ice by parameterized thickness of new ice in a coupled climate model. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2024, 51, e2024GL110166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kon, W.; Li, X.; Zou, H. Optimizing MaxEnt model in the prediction of species distribution. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2019, 30, 2116–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Shi, N.; Zhu, Z.; Shi, R.; Li, Y.; Xu, X. Prediction of the potential geographical distribution of three Limonium plants in China under climate change based on MaxEnt and ArcGIS models. J. Gansu Agric. Univ. 2025, 60, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, G.; Du, S. Predicting the influence of future climate change on the suitable distribution areas of Elaeagnus angustifolia. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 29, 3213–3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Cui, Q.; Wang, Z.; Li, T.; Qi, W.; Ye, X.; Fang, B. Prediction of suitable habitat of Ziziphus jujuba var. spinosa in China under Context of Climate Change. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2021, 57, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaynes, E.T. Information theory and statistical mechanics. Phys. Rev. 1957, 106, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elith, J.; Phillips, S.J.; Hastie, T.; Dudík, M.; Chee, Y.E.; Yates, C.J. A statistical explanation of MaxEnt for ecologists: Statistical explanation of MaxEnt. Divers. Distrib. 2011, 17, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjitkar, S.; Xu, J.; Shrestha, K.K.; Kindt, R. Ensemble forecast of climate suitability for the Trans-Himalayan Nyctaginaceae species. Ecol. Model. 2014, 282, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Zhu, P.; Li, H.; Tan, B.; Xu, Z.; You, C. Prediction of potential suitable distribution of Quercus serrata Thunb. var. brevipetiolata (A.DC.) Nakai in China under climate change scenarios. Chin. J. Appl. Environ. 2025, 31, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Huo, H.; Tian, L.; Dong, X.; Qi, D.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Cao, Y. Potential geographical distribution of Pyrus calleryana under different climate change scenarios based on the MaxEnt model. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2018, 29, 3696–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Q.; Chen, C.; Zengtai, Y.; Longzhu, D.; Miao, Q.; Sun, F.; Gairang, L.; Cheng, X.; Suonan, J. Evaluation of Habitat Suitability of Important Medicinal Plants Gentianaceae in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Based on the Optimized Maximum Entropy Model. Acta Agrestia Sin. 2025, 33, 3024–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B. Research on the Response of Vegetation to Climate Change and Human Activities on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau; Nanjing Forestry University: Nanjing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xie, W.; Shen, Q.; Cheng, J.; Shen, W.; Dang, M.; Wang, Z. Optimizing and Predicting the Potential Suitable Habitat of Stellera chamaejasme L. in Xizang Under Climate Change Using MaxEnt Model. Acta Agrestia Sin. 2025, 33, 2603–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Ma, X.; Su, R.; Ni, L. Research on Prediction of Potential Distribution Area of Rhododendron anthopogonoides Maxim. in Gansu and Qinghai Provinces under the Background of Climate Change. Chin. J. Inf. Tradit. 2025, 32, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.L.; Liu, Y.; Su, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, P.; Qu, R.; Jin, J.; Yang, Q.; Yu, M.; Song, C. Prediction of the Potential Distribution Area of Saussurea medusa(Asteraceae) an Endemic Medicinal Plant from the Qinghai-Xizang Plateau under the Background of Climate Changes. Acta Agrestia Sin. 2025, 33, 910–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Q.; Kamusi, A.L.M.J.; Bao, A.; Wang, J.; Shi, H.; Zhao, J. The Prediction of Suitable Area and Analysis of Influencing Factors of Saussurea involucrata Based on the MaxEnt Model. Acta Agrestia Sin. 2025, 33, 1544–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Xu, H.; Fen, Z.; Yan, P. Study on Gentianaceae in the Karakorum Mountains in China. Arid. Zone Res. 2011, 28, 638–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Wen, X.; Yan, J. Categorization and Ecogeographical Distribution of Gentianaceae Plant Resources in the Semi-humid Plateau Region of Tibet. Xizang Sci. Technol. 2013, 239, 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Mao, Y.; Wang, F. Prediction of Potential Suitable Habitats and Study of Influencing Factors for Gentiana veitchiorum Based on MaxEnt Model. J. Plateau Agric. 2025, 9, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yujing, Y.; Yi, L.; Wang, W.; He, J.; Yang, R.; Wu, H.; Wang, X.; Lei, J.; Tang, Z.; Yao, Y. Range shifts in response to climate change of Ophiocordyceps sinensis, a fungus endemic to the Tibetan Plateau. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 206, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Chen, K.; Wang, B.; Gao, Y.; Zhou, G. Geospatial Pattern and Potential Distribution Prediction of Endemic Plant Przewalskia tangutica on the Tibetan Plateau. J. Northwest For. Univ. 2025, 40, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Xu, X.; Mao, K.; Wang, M.; Wang, K.; Xi, Z.; Liu, J. Shifts in plant distributions in response to climate warming in a biodiversity hotspot, the Hengduan Mountains. J. Biogeogr. 2018, 45, 1334–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavender-bares, J.; Holbrook, N.M. Hydraulic properties and freezing-induced cavitation in sympatric evergreen and deciduous oaks with, contrasting habitats. Plant Cell Environ. 2001, 24, 1243–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Jiang, Z.; Li, T. Climate projection over China under global warming of 1.5 and 2 °C considering model performance and independence. Trans. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 47, 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Su, X.; Wang, D.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Sun, C. Prediction of the Geographical Distribution Pattern of Rhodiola tangutica (Crassulaceae) under the Background of Climate Change, an Endemic Species from the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Bull. Bot. Res. 2024, 44, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Chu, T.; Liu, Q.; Qin, L.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Q.; Niu, L.; Zhao, L.; Dong, J.; Dong, S. Research advances in flowering phenology for grassland on the Tibet Plateau and responses to hydrothermal changes. Grassl. Turf 2023, 43, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skal, S.G. Response Characteristics of Flowering Phenology of Different Plants to Climate Change and Grazing Utilization in Alpine Grasslands; Xizang University: Lhasa, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Xia, J.; Zeng, S.; Liu, X.; Fan, D. Evaluation of the Performance of CMIP6 Models and Future Changes Over the Yangtze River Basin. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2023, 32, 137–150. https://yangtzebasin.whlib.ac.cn/CN/Y2023/V32/I1/137.

- Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, T.; Li, F.; Zhao, T. Characteristics of Dry and Wet Variations in the Northwest China and Their Future Predictions. Clim. Environ. Res. 2024, 29, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yao, L.; Meng, J.; Tao, J. Maxent modeling for predicting the potential geographical distribution of two peony species under climate change. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 634, 1326–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Svenning, J.; Chen, G.; Zhang, M.; Huang, J.; Chen, B.; Ordonez, A.; Ma, K.P. Human activities have opposing effects on distributions of narrow-ranged and widespread plant species in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 26674–26681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishy, M.N.; Shemonty, N.A.; Fatema, S.I.; Mahbub, S.; Mim, E.L.; Raisa, M.B.H.; Anik, A.H. Unravelling the effects of climate change on the soil-plant-atmosphere interactions: A critical review. Soil Environ. Health 2025, 3, 100130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Abbreviation | Bio-Climatic Variables | Bangjian | Jieji | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent Contribution | Permutation Importance | Percent Contribution | Permutation Importance | ||

| Elevation | Elevation | 44.5 | 5.9 | 34 | 5.7 |

| bio3 | Isothermality | 12.1 | 22.1 | 30.9 | 50.9 |

| bio12 | Annual Precipitation | NA | NA | 20.6 | 28.6 |

| bio11 | Mean Temperature of Coldest Quarter | 7 | 7.6 | 5.2 | 5 |

| bio4 | Temperature Seasonality | 3.3 | 16.9 | 4.3 | 8.5 |

| bio18 | Precipitation of Warmest Quarter | 29.1 | 43.9 | NA | NA |

| T_CACO3 | Carbonate or lime content | NA | NA | 3.2 | 0.8 |

| T_BS | Basic Saturation | NA | NA | 1.8 | 0.5 |

| T_ESP | Exchangeable sodium salt | NA | NA | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| T_CEC_CLAY | Cation Exchange Capacity of Clayey Soils | 2.9 | 3 | NA | NA |

| T_SILT | Silt content | 0.8 | 0.3 | NA | NA |

| T_PH_H2O | pH level | 0.3 | 0.2 | NA | NA |

| Category | Unsuitability Area | Low Suitability Area | Medium Suitability Area | High Suitability Area |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BangJian | 0–0.068 | 0.068–0.2501 | 0.2501–0.4881 | 0.4881–0.8424 |

| JieJi | 0–0.0707 | 0.0707–0.2423 | 0.2423–0.4828 | 0.4828–0.8280 |

| Category | Scenarios | Period | Stable Area (×104 km2) | Expansion Area (×104 km2) | Contraction Area (×104 km2) | Expansion/Contraction (×104 km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BangJian | SSP126 | 2021–2040 | 195.7 | 7 | 8.73 | −1.73 |

| 2041–2060 | 197.38 | 13.65 | 7.05 | +6.60 | ||

| 2061–2080 | 197.6 | 9.27 | 6.84 | +2.43 | ||

| 2081–2100 | 198.99 | 11.34 | 5.45 | +5.89 | ||

| SSP245 | 2021–2040 | 196.09 | 8.17 | 8.34 | −0.17 | |

| 2041–2060 | 199.05 | 12.8 | 5.39 | +7.41 | ||

| 2061–2080 | 196.66 | 14.32 | 7.78 | +6.54 | ||

| 2081–2100 | 198.46 | 17.66 | 5.98 | +11.68 | ||

| SSP585 | 2021–2040 | 196.47 | 6.72 | 7.97 | −1.25 | |

| 2041–2060 | 194.00 | 7.4 | 10.44 | −3.04 | ||

| 2061–2080 | 195.32 | 10.63 | 9.11 | +1.52 | ||

| 2081–2100 | 189.95 | 13.1 | 14.49 | −1.39 | ||

| JieJi | SSP126 | 2021–2040 | 202.9 | 9.05 | 8.79 | +0.26 |

| 2041–2060 | 202.15 | 14.97 | 9.53 | +5.44 | ||

| 2061–2080 | 203.65 | 12.82 | 8.04 | +4.78 | ||

| 2081–2100 | 200.02 | 11.11 | 11.66 | −0.55 | ||

| SSP245 | 2021–2040 | 197.53 | 8.06 | 14.16 | −6.10 | |

| 2041–2060 | 200.23 | 11.16 | 11.45 | −0.29 | ||

| 2061–2080 | 197.62 | 10.81 | 14.06 | −3.25 | ||

| 2081–2100 | 199.7 | 19.74 | 11.98 | +7.76 | ||

| SSP585 | 2021–2040 | 202.03 | 12.19 | 9.66 | +2.53 | |

| 2041–2060 | 198.71 | 9.28 | 12.97 | −3.69 | ||

| 2061–2080 | 195.4 | 13.06 | 16.29 | −3.23 | ||

| 2081–2100 | 191.17 | 14.76 | 20.51 | −5.75 |

| Category | Scenarios | Period | x | y | Distance Traveled (km) | Movement Direction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BangJian | Current | Current | 98.36893 | 31.43862 | NA | NA |

| SSP126 | 2021–2040 | 98.52969 | 31.43957 | 15.28 | Southeast | |

| 2041–2060 | 98.60251 | 31.41696 | 7.36 | Southeast | ||

| 2061–2080 | 98.61697 | 31.40196 | 2.16 | Southeast | ||

| 2081–2100 | 98.55979 | 31.41960 | 5.78 | Northwest | ||

| SSP245 | 2021–2040 | 98.30506 | 31.36603 | 10.08 | Southwest | |

| 2041–2060 | 98.65236 | 31.50243 | 36.32 | Northeast | ||

| 2061–2080 | 98.48660 | 31.36849 | 21.65 | Southwest | ||

| 2081–2100 | 98.70730 | 31.38498 | 21.07 | Northeast | ||

| SSP585 | 2021–2040 | 98.47880 | 31.38354 | 12.10 | Southeast | |

| 2041–2060 | 98.56786 | 31.51658 | 17.01 | Northeast | ||

| 2061–2080 | 98.50874 | 31.31119 | 23.46 | Southwest | ||

| 2081–2100 | 98.36138 | 31.22926 | 16.72 | Southwest | ||

| JieJi | Current | Current | 97.95395 | 31.82757 | NA | NA |

| SSP126 | 2021–2040 | 98.10669 | 31.70489 | 19.86 | Southeast | |

| 2041–2060 | 98.19166 | 31.92941 | 26.16 | Northeast | ||

| 2061–2080 | 98.14829 | 31.73734 | 21.69 | Southwest | ||

| 2081–2100 | 98.03728 | 31.80957 | 13.22 | Northwest | ||

| SSP245 | 2021–2040 | 97.82800 | 31.74566 | 14.99 | Southwest | |

| 2041–2060 | 98.04208 | 31.83611 | 22.62 | Northeast | ||

| 2061–2080 | 98.13273 | 31.82252 | 8.71 | Southeast | ||

| 2081–2100 | 98.22418 | 31.91097 | 13.08 | Northeast | ||

| SSP585 | 2021–2040 | 98.30971 | 31.77338 | 34.22 | Southeast | |

| 2041–2060 | 98.01053 | 31.77206 | 28.34 | West | ||

| 2061–2080 | 98.23209 | 31.71159 | 22.04 | Southeast | ||

| 2081–2100 | 97.97321 | 31.64626 | 25.59 | Southwest |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Su, H.; Qiang, B.; Zhang, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Zhang, K.; De, J. Prediction of Suitable Habitats for Tibetan Medicinal Gentiana Plants of Jieji- and Bangjian-Type Gentianas Based on the MaxEnt Model. Diversity 2025, 17, 857. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120857

Su H, Qiang B, Zhang S, Wang S, Wang S, Zhang K, De J. Prediction of Suitable Habitats for Tibetan Medicinal Gentiana Plants of Jieji- and Bangjian-Type Gentianas Based on the MaxEnt Model. Diversity. 2025; 17(12):857. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120857

Chicago/Turabian StyleSu, Hao, Ba Qiang, Shengnan Zhang, Sujuan Wang, Shiyan Wang, Ke Zhang, and Ji De. 2025. "Prediction of Suitable Habitats for Tibetan Medicinal Gentiana Plants of Jieji- and Bangjian-Type Gentianas Based on the MaxEnt Model" Diversity 17, no. 12: 857. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120857

APA StyleSu, H., Qiang, B., Zhang, S., Wang, S., Wang, S., Zhang, K., & De, J. (2025). Prediction of Suitable Habitats for Tibetan Medicinal Gentiana Plants of Jieji- and Bangjian-Type Gentianas Based on the MaxEnt Model. Diversity, 17(12), 857. https://doi.org/10.3390/d17120857