Abstract

The reproductive biology of the whale shark (Rhincodon typus), the world’s largest fish, remains poorly understood, in large part due to the rarity of observations of neonates and of breeding behaviours. Although several regions in Indonesia, including Saleh Bay (West Nusa Tenggara Province), have been identified as aggregation and sighting sites for juvenile whale sharks (2–7 m total length, TL), smaller individuals from these potential nursery areas have not been previously documented. In August 2024, fishermen operating lift-net fishing vessels (bagans) in eastern Saleh Bay reported five separate sightings of a small whale shark estimated at 1.2–1.5 m TL and approximately four months old. Subsequently, on 6 September 2024, a male neonate measuring approximately 135–145 cm TL, estimated to be around four months old, was incidentally caught inside a bagan lift-net. These observations represent the first records of neonatal whale sharks in Indonesia and among the smallest free-swimming individuals ever documented globally, and suggest that Saleh Bay may serve as a pupping and early nursery area for whale sharks. These findings highlight the ecological significance of Saleh Bay for the early life stages of whale sharks and underscore the importance of collaborative monitoring and citizen science involving bagan fishermen in advancing the research and conservation of this endangered species.

The whale shark (Rhincodon typus) is listed as Endangered (EN) on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, primarily due to significant population declines across its range in the Indo-Pacific and Atlantic Oceans [1]. Despite increasing research efforts focused on understanding this species, particularly its population dynamics and movement ecology (e.g., [2,3]), the whale shark remains a biological enigma. Its reproductive biology is still poorly understood, including aspects related to breeding behavior and reproductive cycles [4]. Furthermore, the duration of gestation and the specific locations where mating and birthing occur remain unknown. To date, only a single pregnant female, captured off Taiwan, has been scientifically examined; that female contained within her uterus approximately 300 embryos in various stages of development [4].

Identifying and protecting nursery and reproductive habitats is crucial for supporting species conservation and management efforts [5]. Unfortunately, not a single whale shark pupping or nursery ground has yet been identified globally [4], and observations of neonatal whale sharks are exceedingly rare [6,7,8]. To date, only 33 sightings of individuals measuring less than 1.5 m TL have been reported worldwide [7]. These individuals were recorded as bycatch, landed specimens, stomach contents, or free-swimming individuals. Such occurrences have been documented across the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans, suggesting a broad distribution range for neonates. The smallest free-swimming neonatal whale shark reported measured 59 cm TL [9]. Similarly, small juveniles measuring between 1.5 and 3.0 m TL are also infrequently observed, and the habitats of individuals within this size class remain largely unknown [10].

To place these observations in context, we applied standard size-class definitions for whale sharks as follows. Whale sharks were categorized by size as neonates (<1.5 m TL), small juveniles (1.5–3.0 m TL), and medium to large juveniles (3–8 m TL) following Rowat and Brooks [11], Norman and Stevens [12], and Dove and Pierce [13]. Neonates are distinguished by a proportionally larger upper caudal fin lobe relative to the lower lobe, a feature not seen in older individuals [13]. Juveniles, particularly males, were identified by the presence of short claspers that do not extend beyond the pelvic fins and show no signs of abrasion [12].

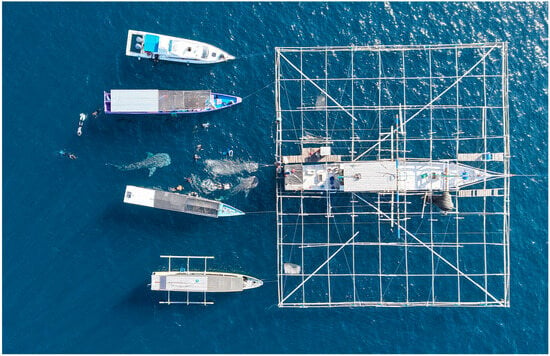

Several regions in Indonesia, including Cenderawasih Bay, Kaimana, Gorontalo, Talisayan, Probolinggo, and Saleh Bay, have been identified as important habitats for juvenile whale sharks [14,15,16,17,18,19]. However, most individuals documented in these areas are juvenile males ranging from 3 to 7 m TL, while smaller individuals (<3 m TL) have rarely been recorded. The smallest individual yet reported from Indonesian waters is a 2.0 m TL female recorded from a seamount off the coast of Fakfak, West Papua [14]. In many of these regions, whale sharks are closely associated with bagans—traditional lift-net fishing platforms that originated from Sulawesi and are now widely used across Indonesia (Figure 1). A bagan typically consists of an extended wooden framework equipped with bright lights to attract small fish, crustaceans and squid at night, and employs a large lift-net to capture small pelagic species including anchovies, scads, and mackerels [20].

Figure 1.

A bagan in Saleh Bay, where whale shark watching tourism activities are commonly conducted (©Edy Setyawan).

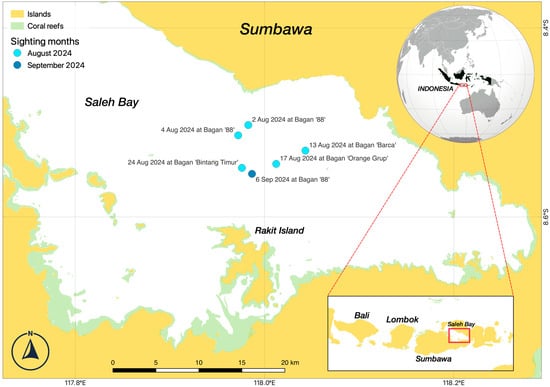

In August 2024, fishermen operating in different locations across Saleh Bay reported five sightings of a small whale shark, each estimated to measure between 1.2 and 1.5 m TL, in the eastern part of the bay (Figure 2). All five sightings occurred either at night (around 11:00 p.m.) or in the early morning (around 04:30 a.m.), typically while fishermen were hauling their nets. In each reported sighting, a single whale shark was seen foraging around the bagans, with fishermen estimating that the shark(s) remained near the platforms for approximately one hour at night and three to four hours in the early morning. The sightings were independent, with only one small-sized whale shark observed at a time near any given bagan; without identifying photos it is impossible to state if all sightings were of the same individual or perhaps of multiple neonate whale sharks.

Figure 2.

Locations of five sightings of a neonatal whale shark (Rhincodon typus) in August 2024 (light blue dots) and one individual captured on 6 September 2024 (dark blue dot) in Saleh Bay, West Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia. Inset: Location of Saleh Bay on Sumbawa Island, east of Bali and Lombok.

Building on the long-standing collaboration between local bagan fishermen and our research team, in which regular communication and knowledge exchange had already been established, the bagan fishermen were encouraged to report whale shark encounters whenever they occurred. Following the reports of a small whale shark sighted around bagans and recognizing the rarity of such observations, fishermen were subsequently advised to document any future encounters in greater detail, including determining the sex and measuring the TL of any individuals that might enter their bagans. Prior to this, our research team have conducted basic trainings to the bagan fishermen on species identification, photo-documentation, and reporting procedures. They submitted observations through WhatsApp to our research team along with dates, locations, and photographs/videos when available. All reports were subsequently verified by the research team through the photographs/videos or, when these photographs/videos were absent, by evaluating report consistency and the fishermen’s prior experience.

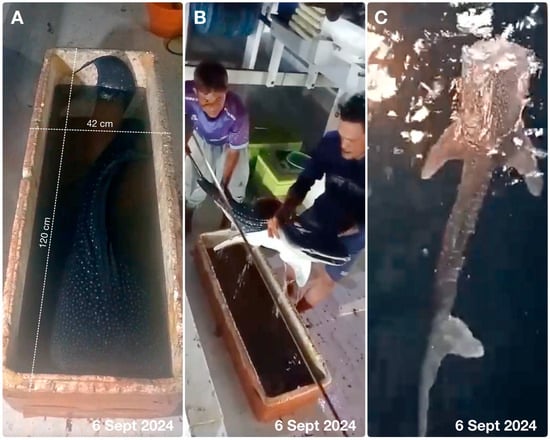

At 04:38 a.m. on 6 September 2024, fishermen operating at Bagan “88” reported that a small whale shark had become trapped inside the lift-net. Instead of releasing the animal immediately, the fishermen temporarily retained it for closer examination. The whale shark was carefully transferred into a large styrofoam cooler box filled with seawater to keep it submerged and calm during containment. The fishermen identified the individual as a male based on the presence of claspers visible on the ventral side. No systematic examination was conducted to assess vitelline scars or other biological characteristics, as the fishers’ knowledge was limited to basic identification, primarily concerning sex and approximate size. The individual’s TL was estimated to be 135–145 cm, based on the outer dimensions of the styrofoam cooler box (120 cm × 42 cm × 32 cm) used to contain the shark (Figure 3A). Six minutes after the transfer, the whale shark was released back into the water (Figure 3B,C; Videos S1 and S2). The fishermen subsequently reported the incident and shared the photographic and video documentation with the research team.

Figure 3.

(A) A neonate whale shark accidentally caught inside the lift-net of a bagan and temporarily placed in a styrofoam cooler box sized 120 × 42 × 32 cm; (B) Bagan fishermen carefully transferring the neonate whale shark from the cooler box back into the water; (C) the neonate whale shark observed free-swimming around the bagan after release (©Hamzah Daeng Ambo).

The size(s) of the small whale shark(s) observed and captured in this study are consistent with previous reports of neonatal whale sharks recorded globally, which range between 46 and 148 cm TL [5,7,9,10,21]. The individual caught in the bagan and estimated at 135–145 cm TL was likely around four months old, based on growth data from a neonate maintained in captivity in Taiwan, which grew rapidly from 60 to 139 cm TL after 120 days [22]. Using this growth rate as a reference, the five observations of small whale sharks around the Saleh Bay bagans in August 2024, each estimated at 1.2–1.5 m TL, were likely of an individual (or individuals) approximately four months old as well. Given the nature of these visual size estimates by fishermen, we cannot state with certainty if these observations might not have been of the same individual that was eventually captured on 6 September 2024.

These findings highlight the importance of Saleh Bay as a habitat not only for juvenile whale sharks [15,18] but also for neonates (<1.5 m TL) [13], which may utilize the area for shelter and foraging to support early growth and survival. Since 2017, a total of 113 individual whale sharks have been photo-identified from 518 sightings in Saleh Bay through a combination of systematic monitoring and citizen science efforts [15].

Importantly, Womersley et al. [7] found that locations of neonatal whale shark encounters often coincide with permanent oxygen minimum zones, characterized by high surface chlorophyll-a concentrations and low oxygen levels at depth. They hypothesized that mature female whale sharks may employ an adaptive pupping strategy, giving birth in such regions to provide neonates with refuge from predators and access to rich foraging grounds—conditions that are likely present in Saleh Bay [23]. However, no studies have yet characterized dissolved oxygen levels at depth within Saleh Bay, and further research is needed to determine whether similar oceanographic features occur there.

Saleh Bay exhibits distinct oceanographic characteristics as a semi-enclosed body of water with restricted circulation but high nutrient availability. Nutrient enrichment is enhanced by inputs from surrounding ecosystems, including mangrove forests, seagrass beds, and coral reefs, which contribute to the bay’s ecological productivity. Agrichemical runoff from the sugarcane fields on the northern coastline of the bay likely enhance this productivity. Geologically, the bay forms a deep basin that facilitates the accumulation of organic matter and sustains high water productivity [23]. Extensive mangrove forests around the bay supply organic material and provide habitat for a range of prey species consumed by whale sharks, including small baitfish such as anchovies (Engraulidae), silversides (Atherinidae), herrings and sprats (Clupeidae), and small sergestid shrimps (Acetes intermedius, locally known as rebon), particularly during their early life stages [14,15,24].

The abundance of rebon shrimp in Saleh Bay has been a key driver in the proliferation of bagans. The interaction between high plankton biomass, the presence of rebon, and bagan fishing activities creates a distinctive linkage between marine ecological processes and coastal livelihoods, positioning Saleh Bay as a region of exceptional ecological and socio-economic value [25]. In other parts of Indonesia, such as Cenderawasih Bay and Kaimana in Papua, bagans have also been utilized as platforms for whale shark tourism and scientific research on whale shark populations [14]. Additionally, they serve as valuable sites for opportunistic observations of cetaceans associated with fishing activities, such as those reported in Kaimana [26].

Our observations of neonatal whale sharks in Saleh Bay further underscore the value of citizen science as a collaborative approach for collecting crucial data on populations of globally endangered species. By engaging local communities, citizen science fosters stewardship and enhances environmental awareness while generating valuable scientific insights. This effort builds on a long-term partnership between local bagan fishermen and our research team, who have worked together for many years to document whale shark occurrence and promote conservation in the region. In this case, bagan fishermen—through their routine interactions with whale sharks—have played a vital role in supporting whale shark research and conservation initiatives in Saleh Bay. Citizen science has contributed substantially to studies of other charismatic megafauna, including manta rays [27], sharks [28], and cetaceans [29].

In conclusion, this study reports the first confirmed records of neonatal whale shark(s) in Indonesia, with the single captured individual being amongst the smallest free-swimming whale sharks documented globally [7]. Furthermore, Saleh Bay in West Nusa Tenggara represents a significant habitat for early life stages of whale sharks, providing a rare opportunity to observe neonates in the wild. The concentration of young whale sharks in this area [15] suggests that it may function as a critical nursery ground, offering abundant food resources and likely to offer refuge from predators—key factors for the survival and growth of juvenile whale sharks [7]. Applying the nursery-ground framework of Heupel et al. [30,31], our observation of a single neonate whale shark in the productive, semi-enclosed waters of Saleh Bay provides preliminary evidence that the area may satisfy the first criterion for identifying potential nursery habitats that neonates or young-of-the-year individuals occur more frequently here than in surrounding areas. Although the confirmed detection of only one neonate limits our ability to confirm this criterion, the bay’s high prey availability and sheltered conditions are consistent with characteristics expected to support early-life survival. However, evidence of repeated or long-term use by neonates is currently lacking, underscoring the need for continued monitoring before Saleh Bay can be formally considered a nursery ground.

Our findings provide the first preliminary evidence that Saleh Bay may serve as a pupping ground for whale sharks, although additional evidence is required to confirm this. Furthermore, our findings highlight the importance of fishermen (citizen scientists) in collecting crucial conservation information. Collectively, these results underscore the ecological importance of Saleh Bay as a potential hotspot for whale shark conservation and highlight the need for further research to elucidate the spatial and temporal dynamics of neonate and young juvenile whale shark occurrence in the region.

Future research should focus on establishing long-term monitoring programs to document temporal patterns in neonate occurrence, abundance, and environmental parameters. Additionally, expanding collaboration with local fishermen and community members to incorporate their observations into a structured data collection framework would greatly strengthen the evidence regarding Saleh Bay’s potential role as a whale shark pupping or nursery habitat.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d17120839/s1, Video S1: A caught neonate placed in a cooler box at bagan.mp4; Video S2: Releasing a neonate back into the water.mp4.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.S. and E.S.; methodology, I.S.; validation, I.S., E.S. and M.E.; investigation, I.S. data curation, I.S. and E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, I.S. and E.S.; writing—review and editing, I.S., Y.Y., M.I.H.P., M.E., M.P.P. and E.S.; visualization, E.S. and I.S.; supervision, M.P.P. and E.S.; funding acquisition, M.I.H.P. and M.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Indonesia National Research and Innovation Agency—BRIN (protocol code 199/KE.02/SK/10/2023 and 30 October 2023).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the captain and crew of Bagan “88” for providing whale shark footage and the captains and crews of the Bagans “Barca”, “Orange Grup”, and “Bintang Timur” for providing information about whale shark occurrences around the bagans. The first author thanks MAC3 Impact Philanthropies for providing a scholarship to pursue a master’s degree at the University of Indonesia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pierce, S.J.; Rohner, C.A.; Perry, C.T.; Jabado, R.W.; Norman, B.; Reynolds, S.; Womersley, F.; Robinson, D.; Graham, R.; Araujo, G. Rhincodon typus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2025: E.T19488A126673248. 2025. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/19488/126673248 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Macena, B.C.L.; Hazin, F.H.V. Whale shark (Rhincodon typus) seasonal occurrence, abundance and demographic structure in the mid-Equatorial Atlantic Ocean. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyminski, J.P.; de la Parra-Venegas, R.; González Cano, J.; Hueter, R.E. Vertical movements and patterns in diving behavior of whale sharks as revealed by pop-up satellite tags in the eastern Gulf of Mexico. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joung, S.-J.; Chen, C.-T.; Clark, E.; Uchida, S.; Huang, W.Y.P. The whale shark, Rhincodon typus, is a livebearer: 300 embryos found in one ‘megamamma’ supreme. Environ. Biol. Fishes 1996, 46, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aca, E.Q.; Schmidt, J.V. Revised size limit for viability in the wild: Neonatal and young of the year whale sharks identified in the Philippines. Asia Life Sci. 2011, 20, 361–367. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, J.; Chen, C.; Sheikh, S.; Meekan, M.; Norman, B.; Joung, S. Paternity analysis in a litter of whale shark embryos. Endanger. Species Res. 2010, 12, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Womersley, F.C.; Waller, M.J.; Sims, D.W. Do whale sharks select for specific environments to give birth? Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e70930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.A. A review of behavioural ecology of whale sharks (Rhincodon typus). Whale Sharks Sci. Conserv. Manag. 2007, 84, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukuyev, E. The new finds in recently born individuals of the whale shark Rhiniodon typus (Rhiniodontidae) in the Atlantic Ocean. J. Ichthyol. 1996, 36, 203. [Google Scholar]

- Rowat, D.; Gore, M.A.; Baloch, B.B.; Islam, Z.; Ahmad, E.; Ali, Q.M.; Culloch, R.M.; Hameed, S.; Hasnain, S.A.; Hussain, B.; et al. New records of neonatal and juvenile whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) from the Indian Ocean. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2008, 82, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowat, D.; Brooks, K.S. A review of the biology, fisheries and conservation of the whale shark Rhincodon typus. J. Fish Biol. 2012, 80, 1019–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, B.M.; Stevens, J.D. Size and maturity status of the whale shark (Rhincodon typus) at Ningaloo Reef in Western Australia. Whale Sharks Sci. Conserv. Manag. 2007, 84, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dove, A.D.M.; Pierce, S.J. (Eds.) Whale Sharks: Biology, Ecology, and Conservation, 1st ed.; CRC marine biology series; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-1-032-04940-3. [Google Scholar]

- Setyawan, E.; Hasan, A.W.; Malaiholo, Y.; Sianipar, A.B.; Mambrasar, R.; Meekan, M.; Gillanders, B.M.; D’Antonio, B.; Putra, M.I.; Erdmann, M.V. Insights into the population demographics and residency patterns of photo-identified whale sharks Rhincodon typus in the Bird’s Head Seascape, Indonesia. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 12, 1607027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, M.I.H.; Syakurachman, I.; Hasan, A.W.; Prasetio, H.; Sanjaya, I.; Setyawan, E.; Prasetiamartati, B. Kajian Awal: Potret Populasi, Habitat, dan Nilai Ekonomi Hiu Paus untuk Pengembangan Kawasan Konservasi di Teluk Saleh, Provinsi Nusa Tenggara Barat; Konservasi Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yasir, M.; Hartati, R.; Indrayanti, E.; Amar, F.; Tarigan, A.I. Seasonal Constellation of Juvenile Whale Sharks in Gorontalo Bay Coastal Park. ILMU Kelaut. Indones. J. Mar. Sci. 2024, 29, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himawan, M.R.; Tania, C.; Yusma, A.M.I.; Noor, B.A.; Subhan, B.; Madduppa, H. Comparison of Sex and Size Range of Whale Sharks and Their Sighting Behaviour in Relation to Fishing Lift Nets in Borneo and Papua, Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 4th International Whale Shark Conference, Doha, Qatar, 16–18 May 2016; Volume 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, M.F.; Hariyadi, S.; Kamal, M.M.; Susanto, H.A. Evidence of residential area of whale sharks in Saleh Bay, West Nusa Tenggara. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 744, 012018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M.M.; Wardiatno, Y.; Noviyanti, N.S. Habitat conditions and potential food items during the appearance of whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) in Probolinggo waters, Madura Strait, Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 4th International Whale Shark Conference, Doha, Qatar, 16–18 May 2016; Volume 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, S.; Sulaiman, M.; Alam, S.; Anwar, A.; Syarifuddin, S. Proses penangkapan dan tingkah laku ikan bagan petepete menggunakan lampu LED. J. Teknol. Perikan. Dan Kelaut. 2016, 6, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhilesh, K.; Shanis, C.; White, W.; Manjebrayakath, H.; Bineesh, K.; Ganga, U.; Abdussamad, E.; Gopalakrishnan, A.; Pillai, N. Landings of whale sharks Rhincodon typus Smith, 1828 in Indian waters since protection in 2001 through the Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2013, 96, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.-B.; Leu, M.-Y.; Fang, L.-S. Embryos of the whale shark, Rhincodon typus: Early growth and size distribution. Copeia 1997, 1997, 444–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusumawati, E.; Susilo, S.B.; Agus, S.B.; Taslim, A.; Yulius, Y. Analisis penentuan sebaran konsentrasi Klorofil-A dan produktivitas primer di perairan Teluk Saleh menggunakan citra satelit Landsat OLI 8. J. Pengelolaan Sumberd. Alam Dan Lingkung. J. Nat. Resour. Environ. Manag. 2019, 9, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renita, O.; Karnan, K.; Ilhamdi, M.L. The Abundance of Rebon Shrimp in Labuan Sangoro Sumbawa District as Supplement Material for Learning Invertebrate Zoology. J. Biol. Trop. 2024, 24, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djunaidi, A.; Jompa, J.; Kadir, N.N.; Bahar, A.; Tilahunga, S.D.; Lilienfeld, D.; Hani, M.S. Analysis of two whale shark watching destinations in Indonesia: Status and ecotourism potential. Biodivers. J. Biol. Divers. 2020, 21, 4911–4923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, M.I.H.; Malaiholo, Y.; Sahri, A.; Setyawan, E.; Herandarudewi, S.M.C.; Hasan, A.W.; Prasetio, H.; Hidayat, N.I.; Erdmann, M.V. Insights into cetacean sightings, abundance, and feeding associations: Observations from the boat lift net fishery in the Kaimana important marine mammal area, Indonesia. Front. Mar. Sci. 2025, 11, 1431209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setyawan, E.; Erdmann, M.V.; Lewis, S.A.; Mambrasar, R.; Hasan, A.W.; Templeton, S.; Beale, C.S.; Sianipar, A.B.; Shidqi, R.; Heuschkel, H.; et al. Natural history of manta rays in the Bird’s Head Seascape, Indonesia, with an analysis of the demography and spatial ecology of Mobula alfredi (Elasmobranchii: Mobulidae). J. Ocean Sci. Found. 2020, 36, 49–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohler, J.; Gore, M.; Ormond, R.; Austin, T.; Olynik, J. The Sharklogger Network—Monitoring Cayman Islands shark populations through an innovative citizen science program. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0319637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvey, G.K.; Nelson, T.A.; Paquet, P.C.; Ferster, C.J.; Fox, C.H. Comparing citizen science reports and systematic surveys of marine mammal distributions and densities. Biol. Conserv. 2018, 226, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heupel, M.R.; Carlson, J.K.; Simpfendorfer, C.A. Shark Nursery Areas: Concepts, Definition, Characterization and Assumptions. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2007, 337, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heupel, M.R.; Kanno, S.; Martins, A.P.; Simpfendorfer, C.A. Advances in Understanding the Roles and Benefits of Nursery Areas for Elasmobranch Populations. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2019, 70, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).