Abstract

This study investigates hydroid species distribution across the western Atlantic coastline, focusing on biogeographic patterns, comparing them with Caribbean assemblages, and assess the influence of environmental variables—including salinity, temperature, primary productivity, ocean currents, and chlorophyll—on biogeographic structure. We analyzed 375 species from to 9259 records (1946–2022), spanning the western Atlantic from the Caribbean to southern Argentina (28° N–53° S). Cluster analyses using UPGMA and ordination via nMDS, based on Sorensen-transformed occurrence data. Taxonomic distinctness was assessed with Average Taxonomic Distinctness (Delta+) and Lambda+ variation. UPGMA clustering revealed two main groups: one in the Caribbean and Brazil, and another in southern Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina. The Amazon River mouth acted as a semi-permeable barrier, with 21.4% species overlap between Caribbean and Brazil. Southeastern Brazil had the highest species richness, likely due to environmental synergy and biodiversity hotspot. Assemblages followed known biogeographic gradients, with lower diversity offshore and on islands. The Río de la Plata showed a distinct, salinity-driven composition. Salinity, chlorophyll, and currents were key distribution drivers.

1. Introduction

The coastline of Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina spans about 13,000 km and encompasses diverse climates and habitats [1]. This Southwestern Atlantic Ocean (SWAO) region is shaped by the South Equatorial Current (SEC), the Brazil Current (BC), and the Malvinas/Falkland Current (FC) [2] regulate nutrient fluxes, heat distribution, and organism dispersal [3]. The BC transports warm, nutrient-poor waters such as SEC, while the FC carries cold, nutrient-rich waters northward from the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, and their convergence generates gradients and eddies that strongly influence ecosystems [4]. In addition, major river plumes, such as the Amazon [5,6] and Río de La Plata [1,7,8], modify coastal conditions.

Despite the environmental complexity, faunal knowledge in the SWAO remains limited [9], especially in northern and northeastern Brazil, due to historical biases and uneven sampling [1,10,11]. While frameworks like the Marine Ecoregions of the World [12] and regional subdivisions based on OBIS (Ocean Biodiversity Information System) data [1], provide valuable baselines but lack taxonomic and spatial detail. More recent syntheses emphasize the importance of phylogenetic turnover and beta diversity, while also identifying major data gaps in the Western Atlantic [13,14]. In terms of biogeographic knowledge, the fauna of various areas of the SWAO remains insufficiently characterized (cf. [9]). In addition to the lack of knowledge related to inadequate sampling, there is also the historical focus of marine biogeographic studies on economically important taxa, while many other groups remain overlooked [1,15]. This knowledge gap is accentuated by the neglect of studies conducted on the northern and northeastern coasts of Brazil [10,11,16], making it clear the need to expand basic taxonomic and faunistic studies in these regions.

Several biogeographic classification systems have been proposed for marine environments, but two are particularly relevant when considering sessile organisms. According to Spalding et al. [12], the Marine Ecoregions of the World (MEOW) framework integrates geographical, political boundaries to organize coastal and continental shelf regions worldwide. This system is structured in three hierarchical levels: (1) realms, which represent unique habitats with distinct evolutionary histories and high levels of endemism, defined by the presence of characteristic taxa; (2) provinces, which encompass biomes that share evolutionary cohesion and a certain degree of endemism; and (3) ecoregions, which correspond to smaller spatial units with relatively homogeneous species assemblages. Complementarily, Miloslavich et al. [1] proposed a regional biogeographic division specifically for the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of South America. This classification was derived from approximately 300,000 occurrence records of 7000 species, compiled from the OBIS and open-access literature. Unlike MEOW, this framework emphasizes oceanographic and ecological drivers, and it identified six major subdivisions: Tropical Eastern Pacific, Humboldt Current System, Tropical Western Atlantic (Guyanas), Caribbean, Brazilian Shelf, and Patagonian Shelf (Uruguay–Argentina). These subdivisions were defined based on the interaction of ocean currents, species distribution patterns, and primary productivity, providing an integrative perspective on marine biodiversity across the region.

Recent integrative regionalization efforts have refined the understanding of marine biogeographic boundaries in the Western Atlantic, emphasizing the role of phylogenetic turnover and beta diversity in delineating assemblages, including hydrozoan taxa [13]. However, spatial and taxonomic biases in sampling—especially pronounced along the northern and northeastern Brazilian coasts—have been shown to significantly influence estimates of species richness and endemism [14]. This reinforces the need for systematic syntheses based on verified records, such as the one presented here.

In recent years, biogeographic research in the SWAO has increasingly adopted hydroids as a model group [17,18,19,20,21]. In this study, the term “hydroid” is used in its traditional, faunistic sense to refer to the benthic, polypoid stage (either solitary or colonial) of a non-monophyletic assemblage within the class Hydrozoa. This usage predominantly encompasses species from the orders “Anthoathecata” (now recognized as non-monophyletic) and Leptothecata, which constitute the majority of sessile, colony-forming hydrozoans (e.g., [21,22]). These organisms are recognized as pioneer colonizers of hard-bottom marine substrates [23], displaying rapid clonal expansion via asexual reproduction and remarkable phenotypic diversity [24,25]. Their distribution spans from intertidal habitats to abyssal depths and extends across virtually all latitudes [9,26,27,28]. Ecologically, hydroids play a pivotal role in the formation of zoobenthic forests [29], often providing structural complexity and ecological niches for a variety of associated taxa [29]. Their ability to colonize a wide range of natural and artificial substrates further underscores their potential as bioinvasive organisms [30]. Despite their ubiquity and ecological relevance, hydroids remain underrepresented in large-scale biodiversity syntheses, a gap that has been repeatedly emphasized in the context of Western Atlantic marine biogeography [13,14]. Consequently, focused analyses of Hydrozoa are essential for improving taxon-specific resolution in regionalization frameworks for the Western Atlantic, directly addressing critical data deficiencies identified in recent integrative biogeographic efforts [13,14].

The main objective of this study was to analyze the distribution patterns of hydroid species, using as a primary source the records along the latitudinal gradient of the coasts of Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina and their adjacent areas derived from online databases, museum collections, and published literature. The distribution patterns of the species were inferred in relation to the flow rates of the main rivers in the region, and to five environmental variables (salinity, temperature, primary productivity, currents, and chlorophyll). Finally, the patterns observed in the SWAO region are compared to hydroid records from the Caribbean, allowing a comparison between Caribbean and Brazilian hydroid assemblages.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Sources

The data used in this study were obtained from three different sources, namely, from collection materials deposited in different institutions, from online repositories, and from bibliographic sources.

The collection material derives from samples obtained in different oceanographic campaigns, namely (i) PIATAM Oceano (Potenciais Impactos Ambientais do Transporte de Petróleo e Derivados na Zona Costeira Amazônica—2008); (ii) Projeto de Caracterização da Bacia Potiguar—2011; (iii) Campanha Geomar Norte e Nordeste, executed between the 1960s–1980s; (iv) Campanha Revizee Score Nordeste, carried out between the end of the 1990s and the beginning of the 2000s; (v) material from the State of Paraíba; and (vi) Campanha Oceanográfica Comissão Recife, which also dates from the end of the 1960s. The specimens studied are deposited in the collections of (i) Museu de Oceanografia Prof. Petrônio Alves Coelho da Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (MOUFPE); (ii) Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo (MZUSP); (iii) Cnidaria Collection of the Marine Evolution Laboratory, Instituto de Biociências da Universidade de São Paulo (IBUSP); (iv) Cnidaria Collection of the Curitiba Campus, Universidade Federal do Paraná (UFPR); and (v) Cnidaria Collection of the Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata deposited at Estación Costera J.J. Nagera, UNMdP.

The online repositories used were (i) Specieslink; (ii) Extant Specimen; (iii) Ocean Biodiversity Information System (OBIS); (iv) Registros do Sistema de Informação do Programa Biota/Fapesp (SinBiota); (v) Smithsonian Collections Database; (vi) Cnidaria Collection of the Museu de Zoologia da Universidade Estadual de Campinas (UNICAMP); and (vii) Laboratório de Zooplâncton da Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo (LabZoo-UFES).

Finally, the bibliographic sources consisted of those references published between 1946 and 2016 and compiled in the dataset of South American Medusozoa species [31], and of papers retrieved from the Clarivaret Web of Science platform from 2016 to 2022, using the terms “Hydroids” + “Brasil”; “Hydroids” + “Brazil”; “Hidroides” + “Brasil”; “Hydroids” + “Uruguay”; “Hydroids” + “Argentina”; “Hidrozoos” + “Uruguay”; “Hidrozoos” + “Argentina.” Records with incomplete or missing geographic coordinates, as well as those with dubious material provenance, were excluded. The Worms database [32] was used exclusively to check and standardize the taxonomic status of the species compiled from the original literature and collections. It was not used to infer phylogenetic relationships.

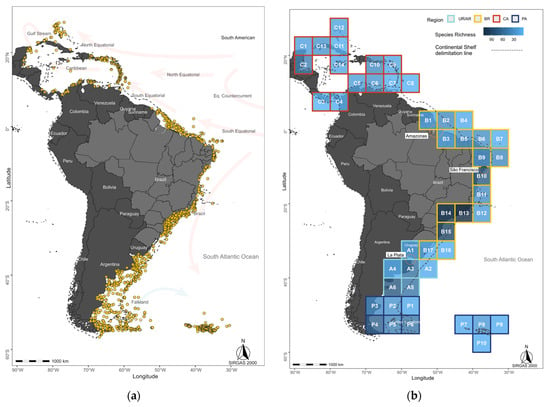

With the compiled data, summary maps were developed in R software v. 4.4.0. The information indexing system of our study focused on the use of geographic coordinates, with political boundaries disregarded for analyses and distribution pattern testing. Taxonomic determinations retained at “cf.” (=‘confer’ or ‘conferatur’), or at the family or genus level, were also excluded. Considering these restrictions, the initial 13,920 records were filtered to 9259 records considered suitable for analysis, totaling 375 species, of which 72 belong to “Anthoathecata” and 303 to Leptothecata. In total, 1454 records with real coordinates were catalogued, sampled between 28° N and 53° S, of which 898 were concentrated along the Brazilian coast and 377 between Uruguay and Argentina. Since hydroid records along the Guyanas are scarce, as also reported for other biological groups [1], we further incorporated data from 163 points in the Caribbean region (Figure 1) to compare Caribbean and Brazilian hydroid assemblages.

Figure 1.

(a) Hydroid records (yellow dots) in the Caribbean and on the east coast of South America. Main ocean currents represented on the map as cold (in light blue) and warm (in light red). (b) Species richness across 47 geographic grid cells, ranging from lowest (light blue) to highest (dark blue). The grid cells were grouped into four regions: CA, Caribbean (red frame); BR, Northern and Southeastern Brazil (yellow frame); UR/AR, Uruguay–Argentina, Buenos Aires Province (light blue frame); and PA, Patagonian regions (dark blue frame). Orange circles indicate the estuarine areas of the main rivers discussed. The dashed line delimits the edges of the continental shelves.

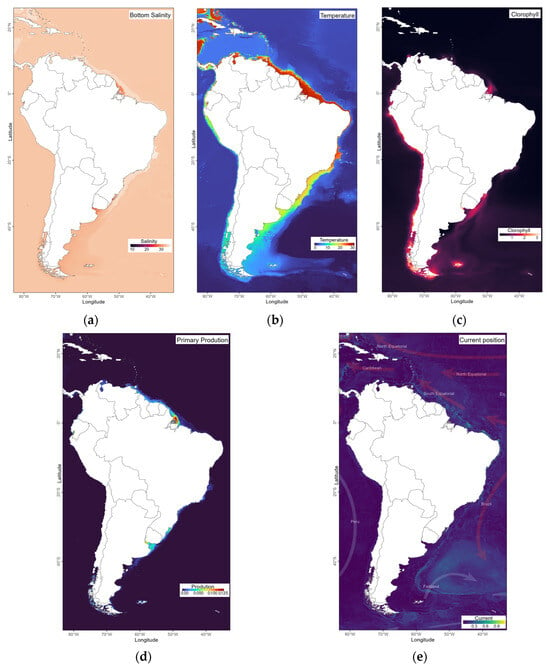

The five selected variables from Bio-Oracle [33], except currents [2] used for analysis were chosen for their potential to influence the marine species distribution. Salinity and temperature gradients influence latitudinal distribution and horizontal stratification [24,34] and together act as important osmoregulators in aquatic species. Chlorophyll and primary production data, as well as current dynamics, are related to water circulation and nutrient distribution, key factors in determining hydroid species distribution. For each sampling point, bottom mean values were extracted from the Bio-Oracle raster layers. In grid-based analyses, environmental averages were calculated by aggregating the mean values of all sampling points within each grid cell.

2.2. Data Analysis

The analyses were performed using R v. 4.4.0 (R Core Team 2024), Primer v. 7 (Plymouth Routines in Multivariate Ecological Research), and SAM v. 4.0 (Spatial Analysis in Macroecology) [35]. The 1454 sampled points were plotted on grid cells (5 × 5°), resulting in 47 geographic grid cells subdivided into four regions (Figure 1b). For the biogeographic cluster analysis of hydroids, we used MEOW [12]. This hierarchical framework categorizes coastal and shelf regions into realms, provinces, and ecoregions based on biodiversity distribution, endemic species, historical evolutionary processes, and significant oceanographic phenomena. In the MEOW context, we identified four biogeographic units for studies. Adhering to this structure and aligning with the biogeographic boundaries established by [36,37,38], we categorized our grid cells into four primary regions: Namely (i) Caribbean Region (CA) between 5° N and 30° N influenced by the Atlantic Ocean; (ii) the grid cells comprising the Brazilian Coast (BR) between 5° N and 35° S; (iii) the region encompassing the coast of Uruguay–Argentina (Buenos Aires Province, AR), between 35°S and 45°S; and (iv) the grid cells covering the Patagonian regions (PA) between 45° S and 60° S.

Hierarchical clustering (UPGMA, Unweighted Pair-Group Method using Arithmetic Averages) was conducted using a Sørensen similarity matrix based on species presence/absence data. Grid cells with fewer than five species records were excluded to avoid clustering artifacts resulting from artificial similarity and zero-inflation [39]. Non-metric multidimensional scaling (nMDS) was also applied to evaluate gradual faunal changes among assemblages. We used ANOSIM (Analysis of Similarities), with a Sørensen similarity matrix, to test similarities among the four groups. ANOSIM, a non-parametric test, was applied to determine whether variation among groups was significantly greater than variation within groups, thus supporting the adequacy of the regional divisions. This test was conducted equivalently for all four groups analyzed [40].

Differences in the taxonomic structure of assemblages were assessed using the Average Taxonomic Distinctness (AVTD) and Variation in Taxonomic Distinctness (VarTD) indices. The combined use of these indices allows comparisons of species assemblages based on taxonomic lists. They are not affected by heterogeneous sampling efforts, are independent of sample size, and can be applied to binary presence/absence data [40,41,42].

Redundancy analysis (RDA) was adopted to relate variation in species or community data to environmental variables [43], while distance-based redundancy analysis (dbRDA) was employed as a distance-based approach to redundancy analysis [44]. Distance-based multivariate multiple regression (DistLM [45]) was used to calculate correlations between community composition and environmental factors. Complemented by dbRDA that was used to visualize the multivariate structure and to examine the correlations between environmental variables and the major ordination axes, highlighting the environmental gradients most strongly associated with community variation. Mean values of the environmental variables (Figure 2) were obtained for each coordinate (Figure 1) through data interpolation.

Figure 2.

Interpolation of values of environmental variables in South America and the Caribbean for the period 2000–2014: (a) salinity (ppm), (b) temperature (°C), (c) chlorophyll (mg·m−3), (d) primary production (mg·m−3), (e) currents (mg·m−3).

3. Results

3.1. Geographical Distribution

The 375 recorded species are distributed across the 1454 geographic points analyzed (Figure 1), grouped into 47 grid cells within four regions of the western Atlantic (Caribbean, Brazil, Uruguay–Argentina, and Patagonia), spanning from 28° N to 53° S (Figure 1b, Table 1a). Among the four regions analyzed, Brazil exhibited the highest richness (909 sites), followed by the Patagonia (195 sites), Uruguay–Argentina (187 sites) and Caribbean 163 sites (Table 1a). Combined, Brazil and Uruguay–Argentina account for records of 320 out of the 375 species in the dataset, comprising 61 “Anthoathecata” and 259 Leptothecata.

Table 1.

Summary of taxon and site number by region. (a) Summary of the number of hydroid families, genera, and species, as well as the number of Leptothecata and “Anthoathecata” species. (b) Summary percentage of shared species (above the diagonal) and shared number of species (below the diagonal) between pairs of regions. Study regions: CA, Caribbean region; BR, comprising the Northern and Southeastern regions of Brazil; UR/AR, Uruguay–Argentina (Buenos Aires Province); and PA, Patagonian regions of Argentina. Differences in richness may reflect heterogeneous sampling effort, particularly the intense research activity historically concentrated in Southeastern Brazil. The “Total” column shows the count of individual species, genera and families, without duplicates.

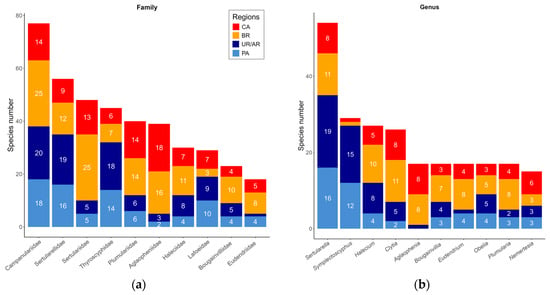

In terms of species richness per family, the highest values were observed in Campanulariidae (77), followed by Sertularellidae (56), Sertulariidae (48), Thyroscyphidae (45), Plumulariidae (39), and Aglaopheniidae (39) (Figure 3a). At the genus level, Sertularella (53), Symplectoscyphus (29), Halecium (27), Clytia (26), Aglaophenia (17), and Bougainvillia (17) were the most frequent (Figure 3b; see complete totals in Supplementary Materials). The greatest species overlap occurred between Uruguay–Argentina and Patagonia (29.5%), followed by the Brazil and Caribbean (21.4%), the Brazil and Uruguay–Argentina (15.1%), Brazil and Patagonia (9.3%), Uruguay–Argentina and Caribbean (7.6%), from all species used in the research (Table 1b), between the total number of species observed for each combination of regions.

Figure 3.

Absolute representation of the ten families (a) and ten genera (b) with the highest richness among the four analyzed regions, namely, Caribbean (CA, red), Brazil (BR, yellow), Uruguay–Argentina (Buenos Aires Province; UA, light blue), and Patagonian regions (PA, dark blue). Values equal to 1 are shown in the graph, but they currently appear without labels to avoid overlapping. Bars represent the absolute number of species in each family (a) or genus (b).

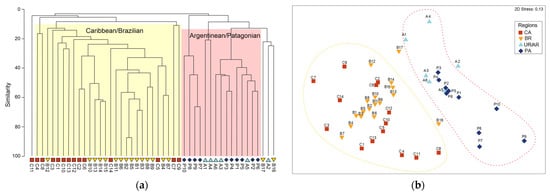

The UPGMA and nMDS analyses consistently revealed two major biogeographic assemblages along the Western Atlantic: a Caribbean/Brazilian group (CB) and a Uruguay–Argentina/Patagonian group (UP), including northern and southern Argentina) (Figure 4a,b). Within the Brazilian grid cells, two groups showed particularly high similarity in the reef area off the Amazon coast, B2 + B5 and B1 + B3. Indeed B2 + B5 exhibited the highest similarity of the entire analysis, with the grid cells sharing 28 of the 38 species they have in common (77.8%). This group corresponds to the reef system area influenced by the Amazon River plume, extending from Maranhão to Amapá [16]. The B4 and B7 branch, in turn, represent the more oceanic portions of the northern region, bordering the continental shelf edge, along the equatorial current path (Figure 1a,b). The richest assemblage was identified in southeastern Brazil including B13–B15, comprising 166 species and consistently recovered in both analyses.

Figure 4.

(a) UPGMA clustering based on a Sørensen similarity matrix (cophenetic correlation = 0.89568). The two clusters formed are highlighted in the figures, namely, Caribbean–Brazilian grid cells (yellow) and Argentinean–Patagonian (salmon). (b) Non-metric multidimensional scaling (nMDS), stress = 0.13. The geographic grid cells were divided into four regions, namely, C, Caribbean region (red); B, comprising the Northern and Southeastern regions of Brazil (yellow); A, Uruguay–Argentina (light blue); and P, corresponding to the Patagonian regions (dark blue). Yellow and red dashed lines in the nMDS represent clusters defined by the hierarchical analysis (a) and are shown only as a visual reference.

The Uruguay–Argentina grid cell A2 was grouped with southernmost Brazilian grid cells B16 + B17, together they carry more than 20% internal similarity, and correspond to nearby biogeographic regions. The branch A1 + A4 encompasses the mouth of the La Plata River and the estuarine region of Bahía Blanca, which are geographically non-contiguous but share 11.8% of the 17 recorded species. Group P7, P8, P9, together with grid cell P10, corresponds to the South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands, and is clearly distinct from the remaining Patagonian and northern Argentine grid cells. Collectively, branch A1 + A4 shares 5 (20%) of the 25 species. Figure 5b also highlights the high variation in taxonomic distinctness within (P7, P8, P9), although this variability is concentrated specifically in grid cell P8.

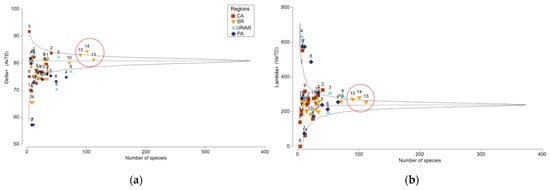

Figure 5.

Funnel plots for (a) Average Taxonomic Distinctness (Delta+) (AvTD) and (b) Variation in Taxonomic Distinctness (Lambda+) (VarTD). Solid black lines indicate the 95% probability interval for simulated AvTD and VarTD. The geographic grid cells were divided into four regions: CA, Caribbean region (red); BR, comprising the Northern and Southeastern regions of Brazil (yellow); UR/AR, Uruguay–Argentina (light blue); and PA, corresponding to the Patagonian regions of Argentina (dark blue). Grids highlighted in red indicate areas with highest sampling effort. Complete data available at Table S3.

Pairwise ANOSIM test indicated statistically significant differences in species composition (Table 2). The regions BR–PA (R = 0.738, p = 0.01) followed by CA–PA (R = 0.635, p = 0.01) presented strong dissimilarities, demonstrating a clear separation of Patagonian assemblages from both Brazilian and Caribbean regions. Regarding the geographic distances among these regions, such results were predictable. Uruguayan-Argentinean assemblages also differed significantly from BR and CA (R = 0.648, p = 0.02; R = 0.593, p = 0.03, respectively), although with slightly lower R values. Overall, the similarity of AR–PA and BR–CA was not significant (p > 0.05), corroborating our previous findings from the cluster and nMDS analyses.

Table 2.

Pairwise ANOSIM comparisons returned significance levels ranging from 0.01% to 20% (equivalent to p = 0.0001 to 0.20) among the four predefined regions: CA, Caribbean region; BR, comprising the Northern and Southeastern regions of Brazil; UR/AR, Uruguay–Argentina; and PA, corresponding to the Patagonian regions.

3.2. Taxonomic Distinctness and Redundancy Analyses

Average Taxonomic Distinctness (AvTD) and Variation in Taxonomic Distinctness (VarTD) indicated that most of the analyzed grid cells fell within the expected confidence interval (Figure 5a,b). However, 2% of the grid cells showed AvTD values above the confidence interval, whereas 29.7% were below, suggesting a lower taxonomic complexity in these regions. For VarTD, 21.2% of the grid cells displayed values above the expected range and 4.2% below (Figure 5a,b). Notably, grid cells P7 and P9, located near South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, exhibited low AvTD and high VarTD values, indicating a faunal composition characterized by closely related lineages but with considerable variation among the species present. Conversely, null VarTD values were observed in the Caribbean region, such as in cell C8 (Figure 4b), indicating a faunal composition with taxa that are very closely related or a lack of significant taxonomic diversity.

Interestingly, the branch B13–B15, well delimited in the clustering analyses and evident in the nMDS (Figure 4b), showed AvTD and VarTD indices consistent with possible stabilization or saturation of the community. This trend, an increase in species number accompanied by a decrease in taxonomic variation, suggests that the local community may be in ecological and taxonomic equilibrium, maintaining diversity even with the addition of new species.

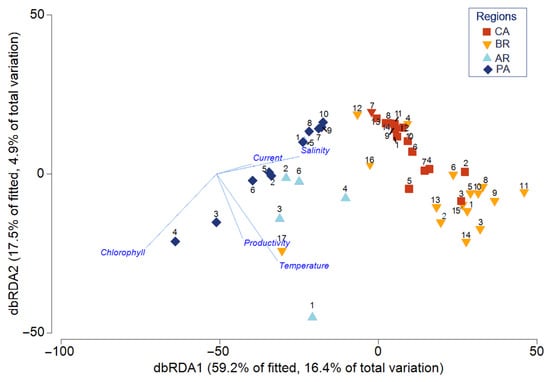

According to the marginal DistLM results, salinity (13%) and temperature (11%) were the variables that explained the largest proportion of variation in hydroid assemblage composition (Table 3). In contrast, the dbRDA ordination, salinity and current velocity showed the strongest correlations with the first axis, indicating that they structure the main environmental gradient, whereas productivity and temperature exhibited moderate correlations with this axis. These results are not contradictory, as DistLM quantifies explanatory power, while dbRDA reflects the correlation of predictors with multivariate axes [45]. Together, the teo analyses reveal both the variables that significantly influence community composition and the environmental gradients that structure spatial patterns. In Argentinean Patagonia, particularly in grid cells associated with the Falkland/Malvinas, South Georgia, and South Sandwich Islands (PA7 to PA10), salinity, chlorophyll, and ocean currents stood out as the main environmental drivers associated with faunal composition.

Table 3.

Distance-based multivariate multiple regression (DistLM), indicating the proportion of variation in the distribution and composition of hydroid assemblages explained independently by each tested variable.

The dbRDA ordination (Figure 6) indicates a strong environmental structuring of hydroid assemblages. The first axis (dbRDA1) separates CA/BR from AR/PA assemblages along gradients of salinity and current velocity, the two most significant predictors identified by DistLM, and accounts for 59.2% of the fitted variation. Secondary gradients influenced by sea surface temperature and productivity are reflected in the second axis (dbRDA2), which accounts for 17.5% of the fitted variation. Chlorophyll-a is strongly associated with AR/PA sites, consistent with the sediment and nutrient discharge from the Amazon plume. Overall, the dbRDA analysis shows that the transition from oceanic, high-salinity waters (CA/BR) to plume-dominated, low-salinity environments (AR/PA) significantly shapes hydroid communities.

Figure 6.

Distance-based redundancy analysis (dbRDA) of biological communities across different regions in relation to five environmental variables, namely, salinity, productivity, temperature, chlorophyll, and currents. Regions: CA, Caribbean region (red); BR, comprising the Northern, Northeastern, and Southeastern regions of Brazil (yellow); UR/AR, Uruguay–Argentina (light blue); and PA, corresponding to the Patagonian regions (dark blue).

4. Discussion

There are hypotheses in the literature suggesting that the Amazon River plume acts as a barrier to the interchange of marine organism assemblages between the Caribbean and Brazilian regions, especially for taxa with reduced dispersal capability [46]. This pattern, however, was not corroborated in a broader study conducted with hydroids from the region (cf. [16]). In fact, under a more permissive scenario, this region could function as an ecological corridor, facilitating species exchange, since the freshwater plume is displaced by the South Equatorial Current toward the Guyanas and the Caribbean [47]. In our study, the 21.4% overlap in species between Brazil and the Caribbean (70 of 327 species) reinforces the hypothesis of faunal exchange [46]. When considering the total species counts within each region, the proportion of shared species statistically declines to 13.1% for the Caribbean and Brazilian regions. It is noteworthy that the Uruguay–Argentinean and Patagonian regions show rates of shared species comparable to those observed between Brazil and the Caribbean. Applying the same reasoning, distant regions exhibit a significantly lower overlap in species composition. Such trends are consistent with our hypothesis of faunal variance across regions and with the biogeographical connection between Caribbean and Brazilian assemblages. It is also important to note that this comparison is based on the total richness of each region; if we consider pairwise relationships among individual grid cells, more localized distribution and similarity are expected, as seen in the UPGMA analysis.

Physically, the depth of the Amazon plume (5 to 25 m throughout the year [6]) is shallower than the bathymetric records of hydroids in the Amazon reef system (down to 240 m), as well as those in other regions (down to 3888 m [11]). This context would explain the reduced effect of the plume as an effective barrier, since populations could “bypass” it through deeper areas. This pattern is in fact consistent with the proposed semi-permeability of large river mouths, as previously observed for sea anemones in the Amazon-Orinoco and La Plata systems [15], for marine invertebrates and other taxa between Amazon-Orinoco and the Caribbean regions [38,46], and for more mobile reef fishes [48]. Carneiro et al. [49] also highlight the existence of a corridor of interconnected reef habitats that facilitates biogeographic connectivity between South American and Caribbean species assemblages.

Despite their presumed limited mobility in the sessile stage, hydroids exhibit a remarkable dispersal capacity, associated with the passive advection of colonies [50,51] and the alternation between polyp and medusa stages [51]. On the one hand, their ability to colonize a wide variety of natural and artificial substrates makes them ecologically prone to wide passive dispersal, including rafting, via attachment to mobile substrates such as floating algae, ship hulls, marine animals, or even plastic debris. Species with free-swimming medusae in their life cycles may remain in the water column for weeks, thereby extending their dispersal range [52,53,54]. In both contexts, ocean currents play a central role [52], in shaping the distribution of hydroid species.

In the Southwestern Atlantic Ocean (SWAO), hydroid distribution is directly influenced by the South Equatorial Current, which bifurcates and gives rise to the warm, oligotrophic Brazil Current flowing southward. The second branch flows north of the Guyanas, still called the South Equatorial Current, where it meets the mouths of Amazon and Orinoco rivers. The Brazil Current meets the cold, nutrient-rich Falkland/Malvinas Current farther south along South America [1]. Beyond this frontal encounter near the Argentinean coast, some areas along Brazil’s coast also experience Falkland/Malvinas Current upwelling zones [1]. These seasonal dynamics strongly influence the dispersal and consequent distribution of species. In winter, the southward Falkland/Malvinas Current transports waters from the La Plata River estuary northward to southeastern Brazil; in summer, the Brazil Current predominates, extending its influence farther south of the La Plata River estuary [55]. Such processes help explain the regional patterns observed in our analyses. For example, chlorophyll, influenced by the Falkland/Malvinas Current, emerged as a key variable in Argentinean Patagonia. Salinity and temperature, on the other hand, stood out on the coasts of Brazil and Uruguay–Argentina, respectively. Finally, the Caribbean showed high connectivity and potential species accumulation via rafting and passive transport from northern Brazil.

The richness analysis revealed that southeastern Brazil (grid cells 13–15) is the most species-rich area, hosting 90 species, 51 of which (45.9%) are shared with other regions. This peak, equivalent to 45% of the total species recorded in the country, can be attributed both to sampling effort and specialist presence [14,56], as well as ecological factors such as high productivity in upwelling areas and the mixed, heterogeneous influence of coastal currents. The high richness of the Southeastern Brazilian region corroborates several previous studies that had already identified this area as biologically rich for groups such as prosobranch mollusks, scleractinian cnidarians, sea anemones, and reef fishes [48,57,58,59]. Indeed, this is a biogeographic transition zone, where tropical and subtropical elements coexist [60], favoring greater diversity in line with global patterns of enrichment near the tropics [61]. Despite this richness, it is important to emphasize that the region is also under intense anthropogenic pressure, reinforcing its characterization as a true marine biodiversity hotspot cf. [62,63] for related studies.

Taxonomic distinctness indices (AvTD and VarTD) confirmed that most grid cells maintain taxonomic diversity proportional to species richness. Even with high richness, grid cells 13–15 fell within the 95% confidence interval, suggesting taxonomic balance. In contrast, Patagonian grid cells (P7 and P9) showed low AvTD and high VarTD, indicating communities composed of few, distantly related groups, as also observed in sub-Antarctic regions [20]. Meanwhile, oceanic grid cells off northeastern Brazil (B4 and B7) exhibited low values for both indices, possibly due to low productivity and reduced connectivity with the continent [64].

Frameworks such as ecoregions [12] and marine regionalization [1] help synthesize data and contextualize broader patterns, but constant updates are needed. Regarding the organization of assemblages, the Brazilian and Uruguay–Argentina regions largely conform to the biogeographic proposal of Spalding et al. [12], except for the grid cell at the River de la Plata estuary. Although considered a distinct ecoregion and traditionally included in the warm temperate SW Atlantic province, the River de la Plata estuary shows low similarity with the South Brazil ecoregion cf. [12] for additional details. This variation can be explained by the salinity gradient driven by river discharge, along with anthropogenic and abiotic pressures typical of highly urbanized estuarine zones, including metropolitan regions, national capitals, and intense navigation activity. On the other hand, species distribution aligns more closely with the model proposed by Miloslavich et al. (2011) [1], particularly in what concerns Argentina and Uruguay. Indeed, it shares 9.3% of its species with Bahía Blanca, a low-salinity Pleistocene estuary farther south [65]. Despite environmental differences, these estuaries are under significant anthropogenic pressure and therefore exhibit faunal convergences, as indicated in our redundancy analyses (dbRDA).

On the other hand, some patterns proposed in previous frameworks are corroborated by our biogeographical inferences. For example, the SWAO marine regionalization and its division into Large Marine Ecosystems [1]. It shows congruence with our results, such as the characterization of the Brazilian Shelf (BR), a region of warm, low-productivity waters; the Patagonian Shelf (PA), cold and nutrient-rich; and the Caribbean (CA), an area of high connectivity but apparently highly vulnerable to bioinvasions [66]. The corroboration of these patterns suggests that variables such as currents, bathymetry, and productivity can be identified as key factors structuring hydroid communities.

Our study, therefore, provides a comprehensive synthesis of hydroid distribution in the Southwestern Atlantic Ocean, highlighting clear patterns of both diversity and regionalization. Although the temporal scope of the data hinders the detection of recent bioinvasion events, the results certainly fill historical gaps for northern and northeastern Brazil, regions of increasing economic interest, especially for oil and gas exploitation [67,68] However, the persistent lack of more up-to-date data may compromise estimates of richness and endemism, limiting conservation efforts. Furthermore, there is a recurrent absence of precise geographic coordinates and environmental data in publications addressing hydroid fauna. This limitation reduces the resolution of spatial and interregional analyses, particularly in under-sampled areas. Thus, we recommend that future collection and publication efforts systematically incorporate georeferenced and environmental data, thereby strengthening the use of such information in biogeography, conservation, and coastal and marine management.

5. Conclusions

This study offers a comprehensive synthesis of hydroid distribution along a latitudinal gradient in the Southwest Atlantic. Although the temporal scope of the data does not yet allow for the detection of recent bioinvasion events, it reveals clear patterns of diversity and regionalization. It also helps to fill historical knowledge gaps for the North and Northeast of Brazil, regions of growing economic interest, especially due to oil exploration. However, the absence of updated data in these regions may compromise richness estimates, endemism patterns, and conservation efforts. Thus, the need for continuous monitoring and the incorporation of functional and phylogenetic data in coastal and marine management is reinforced. In addition to taxonomic and geographic gaps, a recurring problem in the literature on hydroids stands out: the absence of precise geographic coordinates and contextualized environmental data in publications. Although several studies on hydroids have contributed significantly to the advancement of taxonomic and faunistic knowledge of the region, it is observed that the absence or imprecision of precise geographic coordinates in part of the literature can represent an additional challenge to carrying out spatial analyses and inter-regional comparisons. The non-existence or imprecision of such data can limit the resolution of inferences about distribution patterns, diversity, and endemism, especially in under sampled regions.

It is found that the separation between the species assemblages of the Caribbean and Brazil is not absolute, evidenced by the 21.4% overlap of species compiled in this study. This pattern suggests that, in the most restrictive scenario, the Amazon River mouth acts as a semi-permeable filter for hydroid dispersal. In the more permissive scenario, this region could function as an ecological corridor, facilitating species exchange, since the South Atlantic Equatorial Current towards the Guyanas displaces the freshwater plume. The cells further from the coast showed lower values for the AvTD and VarTD indices, indicating a reduction in taxonomic diversity. This pattern can be attributed to their location in areas with narrower continental shelves and low productivity, resulting in lower species richness. This finding is consistent with previous studies indicating that regions far from the coast and oceanic islands tend to harbor fewer species (e.g., [64]). The dbRDA analysis (Figure 6) revealed that marine currents and salinity are the environmental variables that most influence species distribution in the Argentinean and Patagonian regions. On the other hand, in the Brazilian and Caribbean regions, salinity stands out as the main environmental factor associated with the composition of assemblages. Low productivity and the influence of cold currents characterize the Patagonian region, while the Brazilian and Caribbean regions are influenced by warm currents and higher productivity. These findings highlight the complex interplay of oceanographic and environmental factors in shaping the biogeographic patterns of hydroids in the Southwestern Atlantic.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d17120840/s1, Table S1. Species presence data by genus across the sampled locations. Genera belonging to the order “Anthoathecata” are highlighted in bold. Species occurrences were grouped into grid cells and then assigned to four regions: UR/AR, Uruguay–Argentina; BR, Brazil; CA, Caribbean; PA, Patagonia. Table S2. Species presence data by family across the sampled locations. Families belonging to the order “Anthoathecata” are highlighted in bold. Species occurrences were grouped into grid cells and then assigned to four regions: UR/AR, Uruguay–Argentina; BR, Brazil; CA, Caribbean; PA, Patagonia. Table S3. AvTD (Average Taxonomic Distinction) and VarTD (Variation in Taxonomic Distinction) values for each sampled plot.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.F.C., A.C.M. and C.D.P.; data curation, A.C.d.M.; formal analysis, A.C.d.M. and M.L.B.-C.; funding acquisition, C.D.P.; investigation, A.C.d.M.; methodology, A.C.M. and C.D.P.; project administration, C.D.P.; supervision, F.F.C. and C.D.P.; validation, F.F.C. and A.C.M.; writing—original draft, A.C.d.M.; writing—review and editing, F.F.C., M.L.B.-C., A.C.M. and C.D.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundação de Amparo à Ciência e Tecnologia de Pernambuco (FACEPE). The authors thank the institutions listed below for providing the collection data utilized in this study. The oceanographic campaigns were funded by Petrobras—the Brazilian company responsible for the exploration, processing, and transportation of oil and its derivatives—and by the Geomar Project, a program of the Brazilian Navy aimed at advancing geological and geophysical knowledge to support the exploration of the continental shelf in selected states of the North and Northeast regions. This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brazil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001; National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for Carlos D. Pérez: 315253/2023-1 and Antonio C. Marques: 316095/2021-4; and São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) for Antonio C. Marques, Proc. 2011/50242-5, 2023/17191-5.

Data Availability Statement

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://github.com/cmouraandreza/Biogeography-Diversity-paper-supplementary.git, accessed on 2 December 2025. On the public GitHub folder, you will locate the genera and families list, their distribution across the four regions examined, and the outcomes of the AvTD and VarTD tests, referred to as “Supplementary Material—Appendix A. docx”. The file “Supplementary-data-species. xlsx” includes all species information, all references, and the raw data, with the exact locality.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of Maria Angélica Haddad for kindly welcoming us into her laboratory. We thank Marcelo Veronesi Fukuda for hosting us at the Zoology Museum of USP. We also thank Gabriel Nestor Genzano, for providing access to specimens from his collection from the Estación Costera J.J. Nagera (UNMdP), and to Laura Schejter, for kindly welcoming me to the benthic ecology lab at INIDEP (Argentina).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BC | Brazil Current |

| CA | Caribbean region |

| CF | confer or conferatur |

| dbRDA | Distance-Based Redundancy Analysis |

| DistLM | Distance-Based Multivariate Multiple Regression |

| FC | Malvinas/Falkland Current |

| OBIS | Ocean Biodiversity Information System |

| RDA | Redundancy analysis |

| BR | Brazilian Coast |

| UR-/AR | Uruguay–Argentina |

| PA | Patagonian Coast |

| UPGMA | Unweighted Pair-Group Method using Arithmetic Averages |

| nMDS | Non-metric multidimensional scaling |

| ANOSIM | Analysis of Similarities |

| AVTD | Average Taxonomic Distinctness |

| SAM | Spatial Analysis in Macroecology |

| SEC | South Equatorial Current |

| SWAO | Southwestern Atlantic Ocean |

| VarTD | Variation in Taxonomic Distinctness |

References

- Miloslavich, P.; Klein, E.; Díaz, J.M.; Hernández, C.E.; Bigatti, G.; Campos, L.; Artigas, F.; Castillo, J.; Penchaszadeh, P.E.; Neill, P.E.; et al. Marine Biodiversity in the Atlantic and Pacific Coasts of South America: Knowledge and Gaps. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e14631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S. Currents.mxd, Ocean Currents Data and Map; Harvard Dataverse Dataset: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hays, G.C. Ocean Currents and Marine Life. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R470–R473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piola, A.R.; Falabella, V. El Mar Patagónico: Especies y Espacios. In Atlas of the Patagonian Sea; Falabella, V., Campagna, C., Croxall, J.P., Eds.; Wildlife Conservation Society, BirdLife International: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2009; pp. 54–75. ISBN 9789872522506. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, A.C.; de Lourdes Souza Santos, M.; Araujo, M.C.; Bourlès, B. Observações Hidrológicas e Resultados de Modelagem No Espalhamento Sazonal e Espacial Da Pluma de Água Amazônica. Acta Amaz. 2009, 39, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, R.L.; Amado-Filho, G.M.; Moraes, F.C.; Brasileiro, P.S.; Salomon, P.S.; Mahiques, M.M.; Bastos, A.C.; Almeida, M.G.; Silva, J.M.; Araujo, B.F.; et al. An Extensive Reef System at the Amazon River Mouth. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1501252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mianzan, H.; Lasta, C.; Acha, E.; Guerrero, R.; Macchi, G.; Bremec, C. The Río de La Plata Estuary, Argentina-Uruguay. In Coastal Marine Ecosystems of Latin America; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 185–204. [Google Scholar]

- Acha, E.M.; Mianzan, H.W.; Iribarne, O.; Gagliardini, D.A.; Lasta, C.; Daleo, P. The Role of the Río de La Plata Bottom Salinity Front in Accumulating Debris. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2003, 46, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M.O.; Marques, A.C. Combining Bathymetry, Latitude, and Phylogeny to Understand the Distribution of Deep Atlantic Hydroids (Cnidaria). Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2018, 133, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moura, A.C.; Campos, F.F.; Pérez, C.D. Rediscovery and Redescription of Callicarpa chazaliei Versluys, 1899 (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa) in the Southwestern Atlantic Ocean. Zootaxa 2022, 5120, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moura, A.C.; Campos, F.F.; de Oliveira, U.D.R.; Marques, A.C.; Pérez, C.D. Hydroids (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa) from the Northern and North-Eastern Coast of Brazil: Addressing Knowledge Gaps in Neglected Regions. Mar. Biodivers. 2023, 53, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalding, M.D.; Fox, H.E.; Allen, G.R.; Davidson, N.; Ferdaña, Z.A.; Finlayson, M.; Halpern, B.S.; Jorge, M.A.; Lombana, A.; Lourie, S.A.; et al. Marine Ecoregions of the World: A Bioregionalization of Coastal and Shelf Areas. Bioscience 2007, 57, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, U.; Azevedo, F.; Dias, A.; de Almeida, A.C.S.; Senna, A.R.; Marques, A.C.; Rezende, D.; Hajdu, E.; Lopes-Filho, E.A.P.; Pitombo, F.B.; et al. Beta Diversity and Regionalization of the Western Atlantic Marine Biota. J. Biogeogr. 2024, 51, 1469–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, M.N.M.; Azevedo, F.; Dias, A.; de Almeida, A.C.S.; Senna, A.R.; Marques, A.C.; Rezende, D.; Hajdu, E.; Lopes-Filho, E.A.P.; Pitombo, F.B.; et al. Causes and Effects of Sampling Bias on Marine Western Atlantic Biodiversity Knowledge. Divers. Distrib. 2024, 30, e13839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targino, A.K.G.; Gomes, P.B. Distribution of Sea Anemones in the Southwest Atlantic: Biogeographical Patterns and Environmental Drivers. Mar. Biodivers. 2020, 50, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, F.F.; de Moura, A.C.; de Oliveira Fernandez, M.; Marques, A.C.; Pérez, C.D. Hydroids from a Reef System under the Influence of the Amazon River Plume, Brazil. Mar. Environ. Res. 2024, 198, 106563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M.O.; Collins, A.G.; Marques, A.C. Gradual and Rapid Shifts in the Composition of Assemblages of Hydroids (Cnidaria) along Depth and Latitude in the Deep Atlantic Ocean. J. Biogeogr. 2020, 47, 1541–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercado Casares, B.; Soto Àngel, J.J.; Peña Cantero, Á.L. Towards a Better Understanding of Southern Ocean Biogeography: New Evidence from Benthic Hydroids. Polar Biol. 2017, 40, 1975–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, T.P.; Genzano, G.N.; Marques, A.C. Areas of Endemism in the Southwestern Atlantic Ocean Based on the Distribution of Benthic Hydroids (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa). Zootaxa 2015, 4033, 484–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, T.P.; Fernandez, M.O.; Genzano, G.N.; Cantero, Á.L.P.; Collins, A.G.; Marques, A.C. Biodiversity and Biogeography of Hydroids across Marine Ecoregions and Provinces of Southern South America and Antarctica. Polar Biol. 2021, 44, 1669–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillon, J.; Gravili, C.; Pagès, F.; Gili, J.-M.; Boero, F. An Introduction to Hydrozoa; Publications Scientifiques du Muséum: Paris, France, 2006; Volume 194, ISBN 2856535801. [Google Scholar]

- Millard, N.A.H. Monograph on the Hydroida of Southern Africa; Kaapstad: Cape Town, South Africa, 1975; Volume 68, ISBN 094994081X. [Google Scholar]

- Migotto, A.E.; Marques, A.C.; Flynn, M.N. Seasonal Recruitment of Hydroids (Cnidaria) on Experimental Panels in the São Sebastião Channel, Southeastern Brazil. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2001, 68, 287–298. [Google Scholar]

- Gili, J.M.; Hughes, R.G. The Ecology of Marine Benthic Hydroids. In Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review; Ansell, A.D., Gibson, R.N., Barnes, M., Eds.; UCL Press: London, UK, 1995; Volume 33, pp. 351–426. ISBN 1857283635. [Google Scholar]

- Cunha, A.F.; Carmelet-Rescan, D.; Marques, A.C.; Morgan-Richards, M. Contrasting Morphological and Genetic Patterns Suggest Cryptic Speciation and Phenotype–Environment Covariation within Three Benthic Marine Hydrozoans. Mar. Biol. 2022, 169, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuchert, P. The European Athecate Hydroids and Their Medusae (Hydrozoa, Cnidaria): Capitata Part 2. Rev. Suisse Zool. 2010, 117, 337–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronowicz, M.; Włodarska-Kowalczuk, M.; Kukliński, P. Patterns of Hydroid (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa) Species Richness and Distribution in an Arctic Glaciated Fjord. Polar Biol. 2011, 34, 1437–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronowicz, M.; Włodarska-Kowalczuk, M.; Kukliński, P. Hydroid Epifaunal Communities in Arctic Coastal Waters (Svalbard): Effects of Substrate Characteristics. Polar Biol. 2013, 36, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Camillo, C.G.; Bavestrello, G.; Cerrano, C.; Gravili, C.; Piraino, S.; Puce, S.; Boero, F. Hydroids (Cnidaria, Hydrozoa): A Neglected Component of Animal Forests. In Marine Animal Forests; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 397–427. [Google Scholar]

- Calder, D.; Choong, H.; Carlton, J.; Chapman, J.; Miller, J.; Geller, J. Hydroids (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa) from Japanese Tsunami Marine Debris Washing Ashore in the Northwestern United States. Aquat. Invasions 2014, 9, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, O.M.P.; Miranda, T.P.; Araujo, E.M.; Ayón, P.; Cedeño-Posso, C.M.; Cepeda-Mercado, A.A.; Córdova, P.; Cunha, A.F.; Genzano, G.N.; Haddad, M.A.; et al. Census of Cnidaria (Medusozoa) and Ctenophora from South American Marine Waters. Zootaxa 2016, 4194, 1–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WoRMS Editorial Board World Register of Marine Species. Available online: https://www.marinespecies.org (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Assis, J.; Tyberghein, L.; Bosch, S.; Verbruggen, H.; Serrão, E.A.; De Clerck, O. Bio-ORACLE v2.0: Extending Marine Data Layers for Bioclimatic Modelling. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2018, 27, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, K.; Elliott, M. Effects of Changing Salinity on the Ecology of the Marine Environment. In Stressors in the Marine Environment; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 161–174. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs, J.C. Marine Zoogeography; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1974; ISBN 0070078009. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs, J.C.; Bowen, B.W. A Realignment of Marine Biogeographic Provinces with Particular Reference to Fish Distributions. J. Biogeogr. 2012, 39, 12–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, J.C.; Bowen, B.W. Marine Shelf Habitat: Biogeography and Evolution. J. Biogeogr. 2013, 40, 1023–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, T.F.; Diniz-Filho, J.A.F.; Bini, L.M. SAM: A Comprehensive Application for Spatial Analysis in Macroecology. Ecography 2010, 33, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.R.; Gorley, R.N.; Somerfield, P.J.; Warwick, R.M. Change in Marine Communities: An Approach to Statistical Analysis and Interpretation, 3rd ed.; PRIMER-E: Plymouth, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, K.R.; Gorley, R.N. PRIMER: Getting Started with V6, 1st ed.; PRIMER-E: Plymouth, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, K.R.; Warwick, R.M. Similarity-Based Testing for Community Pattern: The Two-Way Layout with No Replication. Mar. Biol. 1994, 118, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, K.; Warwick, R. A Further Biodiversity Index Applicable to Species Lists: Variation in Taxonomic Distinctness. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2001, 216, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warwick, R.M.; Clarke, K.R. Taxonomic Distinctness and Environmental Assessment. J. Appl. Ecol. 1998, 35, 532–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Wollenberg, A.L. Redundancy Analysis: An Alternative for Canonical Correlation Analysis. Psychometrika 1977, 42, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P.; Anderson, M.J. Distance-based redundancy analysis: Testing multispecies responses in multifactorial ecological experiments. Ecol. Monogr. 1999, 69, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.M.; Gorley, R.N.; Clarke, K.R. PERMANOVA+ for PRIMER: Guide to Software and Statistical Methods, 1st ed.; PRIMER-E: Plymouth, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Giachini Tosetto, E.; Bertrand, A.; Neumann-Leitão, S.; Nogueira Júnior, M. The Amazon River Plume, a Barrier to Animal Dispersal in the Western Tropical Atlantic. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez, S.M.; Patil, P.G.; Morton, J.; Rodríguez, D.J.; Vanzella, A.; Robin, D.V.; Maes, T.; Corbin, C. Marine Pollution in the Caribbean: Not a Minute to Waste; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro, H.T.; Rocha, L.A.; Macieira, R.M.; Carvalho-Filho, A.; Anderson, A.B.; Bender, M.G.; Di Dario, F.; Ferreira, C.E.L.; Figueiredo-Filho, J.; Francini-Filho, R.; et al. South-western Atlantic Reef Fishes: Zoogeographical Patterns and Ecological Drivers Reveal a Secondary Biodiversity Centre in the Atlantic Ocean. Divers. Distrib. 2018, 24, 951–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, P.B.M.; Ximenes Neto, A.R.; Jucá-Queiroz, B.; Teixeira, C.E.P.; Feitosa, C.V.; Barroso, C.X.; Matthews-Cascon, H.; de Morais, J.O.; Freitas, J.E.P.; Santander-Neto, J.; et al. Interconnected Marine Habitats Form a Single Continental-Scale Reef System in South America. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, P.F.S. North-West European Thecate Hydroids and Their Medusae: Keys and Notes for Identification of the Species; Published for the Linnean Society of London and the Estuarine and Coastal Services Association by Field Studies Council; Field Studies Council: London, UK, 1995; ISBN 1851532544. [Google Scholar]

- Pagliara, P.; Bouillon, J.; Boero, F. Photosynthetic Planulae and Planktonic Hydroids: Contrasting Strategies of Propagule Survival. Sci. Mar. 2000, 64, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boero, F. The Ecology of Marine Hydroids and Effects of Environmental Factors: A Review. Mar. Ecol. 1984, 5, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boero, F.; Bouillon, J. Zoogeography and Life Cycle Patterns of Mediterranean Hydromedusae (Cnidaria). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 1993, 48, 239–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, D.R. Local Distribution and Biogeography of the Hydroids (Cnidaria) of Bermuda. Caribb. J. Sci. 1993, 29, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, T.P.; Marques, A.C. Abordagens Atuais Em Biogeografia Marinha. Rev. Biol. 2011, 7, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lande, R.; DeVries, P.J.; Walla, T.R. When Species Accumulation Curves Intersect: Implications for Ranking Diversity Using Small Samples. Oikos 2000, 89, 601–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitahara, M.V. Species Richness and Distribution of Azooxanthellate Scleractinia in Brazil. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2007, 81, 497–518. [Google Scholar]

- Barroso, C.X.; Lotufo, T.M.d.C.; Matthews-Cascon, H. Biogeography of Brazilian Prosobranch Gastropods and Their Atlantic Relationships. J. Biogeogr. 2016, 43, 2477–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aued, A.W.; Smith, F.; Quimbayo, J.P.; Cândido, D.V.; Longo, G.O.; Ferreira, C.E.L.; Witman, J.D.; Floeter, S.R.; Segal, B. Large-Scale Patterns of Benthic Marine Communities in the Brazilian Province. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0198452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacio, F.J. Revisión Zoogeográfica Marina Del Sur Del Brasil. Bol. Inst. Ocean 1982, 31, 69–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, M.O.; Marques, A.C. Diversity of Diversities: A Response to Chaudhary, Saeedi, and Costello. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2017, 32, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, N. Threatened Biotas: “Hot Spots” in Tropical Forests. Environmentalist 1988, 8, 187–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, N. The Biodiversity Challenge: Expanded Hot-Spots Analysis. Environmentalist 1990, 10, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, D.F.R.; Polónia, A.R.M.; Renema, W.; Hoeksema, B.W.; Rachello-Dolmen, P.G.; Moolenbeek, R.G.; Budiyanto, A.; Yahmantoro; Tuti, Y.; Giyanto; et al. Variation in the Composition of Corals, Fishes, Sponges, Echinoderms, Ascidians, Molluscs, Foraminifera and Macroalgae across a Pronounced in-to-Offshore Environmental Gradient in the Jakarta Bay–Thousand Islands Coral Reef Complex. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 110, 701–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perillo, G.M.E.; Piccolo, M.C.; Parodi, E.; Freije, R.H. The Bahia Blanca Estuary, Argentina. In Coastal Marine Ecosystems of Latin America; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 205–217. [Google Scholar]

- Kairo, M.; Ali, B.; Cheesman, O.; Haysom, K.; Murphy, S. Invasive Species Threats in the Caribbean Region; CAB International: Arlington, TX, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E.P.; Osborne, T.; Maldonado-Ocampo, J.A.; Mills-Novoa, M.; Castello, L.; Montoya, M.; Encalada, A.C.; Jenkins, C.N. Energy Development Reveals Blind Spots for Ecosystem Conservation in the Amazon Basin. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2019, 17, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).