Abstract

The Fabaceae family plays a vital role in tropical ecosystems and human livelihoods due to its ecological, nutritional, and medicinal significance. This study provides a comprehensive ethnobotanical assessment of Fabaceae in Maha Sarakham Province, Northeastern Thailand. A total of 83 taxa representing 52 genera were recorded, reflecting the family’s high species richness and cultural importance in local communities. Field surveys and semi-structured interviews were conducted across diverse habitats, including homegardens, community forests, markets, and agricultural areas. Quantitative ethnobotanical indices—Species Use Value (SUV), Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC), Fidelity Level (FL), and Informant Consensus Factor (Fic)—were used to evaluate species importance and cultural consensus. The highest SUV and RFC values were observed for Arachis hypogaea L., Glycine max (L.) Merr., Sesbania grandiflora (L.) Poir., and Vigna unguiculata subsp. sesquipedalis (L.) Verdc., indicating their central roles in local diets and livelihoods. Medicinally significant taxa, including Abrus precatorius and Albizia lebbeck, exhibited high FL and Fic values, reflecting strong community agreement on their therapeutic uses. Diverse applications—spanning food, medicine, fodder, fuelwood, dye, ornamental, and construction materials—highlight the multifunctionality of Fabaceae in rural livelihoods. The documentation of 44 new provincial records further emphasizes the value of integrating Indigenous and local knowledge into biodiversity assessments. These findings provide essential insights for sustainable utilization, conservation planning, and the integration of traditional knowledge with modern scientific approaches.

1. Introduction

The Fabaceae (Leguminosae) family, comprising more than 19,500 species and about 765 genera worldwide, is among the largest and most ecologically significant plant families [1]. Members of this family occupy diverse habitats ranging from tropical rainforests to arid grasslands and play crucial roles in terrestrial ecosystems through nitrogen fixation, soil enrichment, and support of faunal biodiversity [2]. Fabaceae species also have immense socioeconomic value, serving as sources of food, fodder, medicine, timber, dyes, and ornamental plants [3]. Economically important genera such as Phaseolus, Vigna, Cajanus, Arachis, and Glycine provide essential protein-rich crops for human and animal nutrition [4], while others like Acacia, Albizia, and Dalbergia are valued for timber and cultural uses [5].

Fabaceae species play important ecological roles that are closely linked to rural livelihoods and traditional practices, particularly in the northeastern region (Isan), where agriculture and ethnobotany are deeply intertwined [6]. Legumes are widely used as vegetables, traditional medicines, soil improvers, and materials for local crafts, reflecting both their practical and cultural significance [7]. Despite their diversity and multifunctional uses, comprehensive ethnobotanical documentation of Fabaceae in northeastern Thailand remains limited. Previous studies have largely focused on general regional surveys rather than on the Fabaceae family specifically, with few investigations targeting this group in detail.

Ethnobotany, the study of relationships between people and plants, provides an essential framework for documenting and preserving traditional knowledge associated with biodiversity [8]. Indigenous and local communities in Thailand possess extensive knowledge regarding the classification, management, and utilization of plants, often passed orally through generations. This knowledge represents not only a repository of cultural heritage but also a potential source for sustainable development, bioprospecting, and conservation planning. However, modernization, changing land-use patterns, and the decline in traditional livelihoods have led to the erosion of plant-based knowledge systems in many parts of rural Thailand. Documenting and analyzing this knowledge is therefore critical for maintaining cultural identity and ecological resilience [9].

Maha Sarakham Province, situated in the heart of the Khorat Plateau in Northeastern Thailand, offers an ideal setting for ethnobotanical studies due to its diverse landscapes, including rice fields, community forests, and homegardens. The region’s rural communities depend heavily on local flora for daily sustenance, herbal remedies, and cultural rituals. Legumes such as Peltophorum dasyrhachis (Miq.) Kurz, Sesbania grandiflora (L.) Poir., and Tamarindus indica L., are among the prominent plants utilized for food and fodder, while species like Senna siamea (Lam.) H.S.Irwin & Barneby and Xylia xylocarpa (Roxb.) W.Theob. serve timber and medicinal purposes. As members of the Lao Isan ethnic group, local people maintain distinctive plant-related traditions and vocabularies that reflect both ecological adaptation and cultural continuity. For instance, Cassia fistula L. is commonly used in sacred rituals and auspicious ceremonies, such as housewarming (Bai Sri Su Khwan), while Tamarindus indica L. is regarded as an auspicious tree believed to inspire respect and reverence [10].

Nevertheless, rapid socio-economic changes, migration, and agricultural intensification threaten the transmission of such traditional plant knowledge [11]. Understanding how local communities use and perceive Fabaceae species can thus contribute not only to ethnobotanical documentation but also to strategies for biodiversity conservation and rural development [12].

Previous ethnobotanical research in northeastern Thailand has highlighted the richness of traditional plant use, particularly in families such as Bignoniaceae and Zingiberaceae [9,13]. However, despite their high species richness and multifunctional uses, Fabaceae have not been the focus of comprehensive studies. In northeastern Thailand, research targeting this family in detail is still lacking. This gap limits our understanding of the cultural and ecological significance of leguminous plants in the region. Moreover, integrating quantitative ethnobotanical indices—such as Species Use Value (SUV), General Use Value (GUV), Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC), and Fidelity Level (FL)—can provide deeper insight into how knowledge and use are distributed among communities and identify species of highest cultural and functional importance.

Therefore, this study aims to provide a comprehensive assessment of Fabaceae in Maha Sarakham Province, Thailand, focusing on their diversity, traditional knowledge, and patterns of use. The specific objectives are to: (1) document Fabaceae species along with their local names; (2) examine traditional uses across multiple categories, including food, medicine, and cultural applications; and (3) evaluate the ethnobotanical significance of each species using quantitative indices such as Species Use Value (SUV), Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC), and Fidelity Level (FL). The results will enhance understanding of the cultural and ecological importance of Fabaceae, support the preservation of traditional plant knowledge, and inform strategies for sustainable management and conservation of leguminous plant resources in rural northeastern Thailand.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

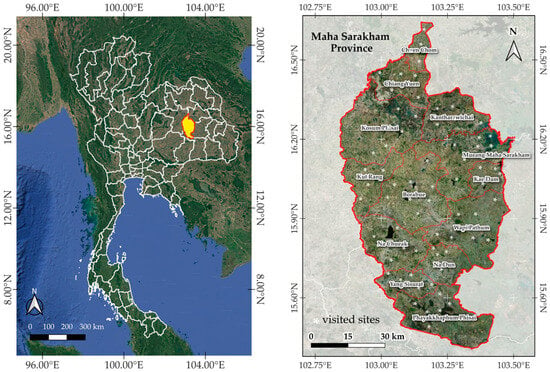

Maha Sarakham Province is situated at the heart of the Khorat Plateau in northeastern Thailand, encompassing approximately 5300 km2. Administratively, it is divided into 13 districts (Figure 1), located between 15°25′–16°40′ N and 102°50′–103°30′ E. The landscape is characterized by gently undulating plains ranging from 130 to 230 m above sea level. The province experiences a tropical monsoon climate, with a dry season from December to April and a rainy season from May to November. The Chi River flows through Maha Sarakham, playing a vital role in shaping local ecosystems and supporting the region’s biodiversity [14].

Figure 1.

Map of Maha Sarakham Province, Thailand, showing the study area. (map created with “QGIS” program ver. 3.34, geographic system ID: WGS 84, EPSG 4326 [15] designed by Phiphat Sonthongphithak).

The population of Maha Sarakham is approximately 930,000 residents [16]. Most of the population belongs to the Lao Isan ethnic group, sharing cultural and linguistic ties with neighboring Laos. The primary language spoken is the Isan dialect, a variant of the Lao language, which is used in daily communication, cultural practices, and traditional knowledge transmission [17].

Theravāda Buddhism is the predominant religion in the province, deeply influencing local customs, festivals, and community life. Buddhist temples (wats) serve as central hubs for religious activities, social gatherings, and educational endeavors. The integration of Buddhism with local traditions fosters a rich cultural heritage, where spiritual beliefs and practices are intertwined with agricultural cycles, healing rituals, and community celebrations [18].

2.2. Data Collection

Data collection was conducted over a 12-month period, from August 2024 to July 2025, to obtain comprehensive insights into the diversity and traditional uses of Fabaceae species in Maha Sarakham Province, Northeastern Thailand. A mixed-methods approach was adopted, integrating both qualitative and quantitative research techniques.

For the purpose of this study, Fabaceae species were defined as plants belonging to the family Fabaceae (Leguminosae) that are utilized by local communities for various purposes, including food, medicine, fodder, fuel, construction materials, and cultural practices. Species were selected based on local recognition and reported traditional uses by informants.

Field surveys were conducted across a wide range of ecological and cultural settings, including deciduous and secondary forests, agricultural fields, homegardens, local markets, and community areas—sites where Fabaceae species are commonly found, cultivated, or traded. The study covered 70 sub-districts across 13 districts, intentionally selected to capture the province’s ecological heterogeneity and socio-economic diversity. A detailed description of all survey sites, including geographic coordinates, administrative divisions, demographic profiles, and cultural attributes, is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and cultural characteristics of survey locations, including GPS coordinates, sub-districts visited (SV), gender distribution, ethnicity, language, and religion.

A total of 260 informants participated in the study, comprising traditional healers, plant vendors, farmers, and household members. Informants were selected through purposive and snowball sampling, emphasizing individuals known for their extensive ethnobotanical knowledge. Semi-structured interviews were used to collect detailed information on local plant names, parts used, preparation and application methods, and categories of use, including medicinal and non-medicinal purposes. Each recorded plant use mentioned by an informant was treated as a use report (UR) and formed the basis for subsequent quantitative analyses.

Simultaneously, botanical identification was conducted through specimen collection and direct field observation. Scientific names were authenticated with assistance from botanists at Mahasarakham University and verified using authoritative databases, including Plants of the World Online (POWO) [19]. All confirmed voucher specimens were deposited at the Vascular Plant Herbarium, Mahasarakham University (VMSU), Kantharawichai District, Maha Sarakham Province, Thailand, for archival reference and future study.

2.3. Utilization Study

Data on the ethnobotanical use of Fabaceae species in Maha Sarakham Province were collected through interviews with 260 residents (130 males and 130 females) from multiple districts. Informants were selected using purposive and snowball sampling techniques to ensure inclusion of individuals recognized for their extensive knowledge of local plants [20,21]. All participants were long-term residents and homeowners in the province; individuals living in temporary or rented accommodation were excluded to ensure familiarity with local traditions and plant use. The participants’ ages ranged from 20 to 70 years and included elders recognized for their cultural knowledge as well as younger adults engaged in agricultural and household activities.

Prior to each interview, the objectives of the study were clearly explained to participants, and prior informed consent was obtained in accordance with the International Society of Ethnobiology (ISE) Code of Ethics [22] and the principles of the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing [23]. Participants were informed of their rights, including voluntary participation, confidentiality of responses, and the option to withdraw at any stage without consequence.

The interviews aimed to document traditional ethnobotanical knowledge, including local plant names, parts used, preparation and consumption methods, and associated uses such as food, medicine, and cultural practices. Interviews were conducted in the local Isan dialect by the authors, who are native speakers. Responses were carefully transcribed and verified with informants when necessary to ensure linguistic and cultural accuracy, and semi-structured interviews with participant observation were employed to minimize potential errors.

Although the study did not involve the collection of sensitive personal information or invasive research methods, all procedures strictly adhered to international ethical standards for ethnobotanical research. Compliance with the ISE Code of Ethics and the Nagoya Protocol ensured respect, transparency, and reciprocity toward participating communities, while promoting the fair recognition of local knowledge holders.

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. The Species Use Value (SUV)

The Species Use Value (SUV) is a quantitative indicator used to evaluate the relative importance of individual Fabaceae species as perceived by local informants in Maha Sarakham Province. The calculation follows the method proposed by Hoffman and Gallaher, and is expressed by formula [24]:

where UVis represents the use value assigned by a single informant for a given species, calculated by dividing the total number of use reports (across all use categories, equally weighted) by the number of times that species was mentioned. The ni denotes the total number of informants interviewed. The final SUV for each species is obtained by averaging the use values reported by all informants, providing a standardized metric of its ethnobotanical relevance.

2.4.2. Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC)

The Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC) was employed to assess how commonly Fabaceae species were mentioned by local informants. This value was determined using the following formula [25]:

Here, FC is the number of informants who mentioned a particular species, and N is the total number of informants interviewed. RFC values range from 0 to 1, where higher values indicate more frequently cited species and thus a greater level of cultural or practical significance within the community.

RFC = FC/N

2.4.3. Plant Part Value (PPV)

The Plant Part Value (PPV) was calculated to assess the relative importance of various plant parts utilized by informants in Maha Sarakham Province. This metric identifies which parts—such as leaves, roots, stems, fruits, bark, and flowers—are most frequently cited in local ethnobotanical practices, especially for medicinal purposes.

PPV was computed following the method described by Gomez-Beloz, using the formula [26]:

where ∑RU(plant part) is the total number of use reports (citations) for a specific plant part across all recorded species, and ∑RU is the total number of use reports for all plant parts from all species in the study. Each use report corresponds to one informant’s mention of a particular plant part’s use. Expressing PPV as a percentage allows for easy comparison of the relative frequency of use among different plant parts, providing insights into their cultural relevance and functional significance within the local ethnobotanical knowledge system.

2.4.4. Informant Consensus Factor (Fic)

To evaluate the consistency in the use of medicinal plants across different ailment categories, the Informant Consensus Factor (Fic) was calculated using the following formula [27]:

In this equation, nur refers to the total number of use reports for a specific ailment category, while nt indicates the number of different plant taxa cited for that category. The Fic value reflects the level of agreement among informants; higher Fic values point to a greater consensus regarding the medicinal application of certain plant species.

Ailments recorded during the study were organized into broad physiological and ethnomedicinal categories, following frameworks used in earlier ethnobotanical research and the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) [28]. The classification applied in this work comprised 12 groups: (1) cardiovascular system, (2) cancer, (3) respiratory system, (4) poisoning and toxicology, (5) skin system, (6) antipyretics, (7) musculoskeletal and joint diseases, (8) infection, parasite and immune system, (9) eyes, (10) gastrointestinal, (11) nutrition and blood, and (12) obstetrics, gynaecology and urinary disorders.

2.4.5. Fidelity Level (%FL)

The Fidelity Level (FL) quantifies the proportion of informants who cited a specific plant species for treating a particular ailment within the study area. It is calculated using the following formula [29]:

In this formula, Np denotes the number of informants who mentioned the plant in relation to a specific health condition, while Nt represents the total number of informants who reported any medicinal use of that plant. The FL value highlights the perceived effectiveness and cultural importance of a species for treating a particular illness.

2.4.6. Comparative Analysis with Previous Studies in the Maha Sarakham Province

To further investigate patterns of diversity among Fabaceae species recorded in Maha Sarakham Province and to compare these findings with previous regional studies, the Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean (UPGMA) [30] was applied exclusively to legume species. The matrix was constructed using presence/absence data (1 = species present, 0 = species absent) for each Fabaceae species across the surveyed locations. It was then analyzed using the UPGMA clustering method, and the resulting dendrograms and heatmap, generated in Past4 software (version 4.15), visualize species similarity across sites and highlight patterns of shared species among locations. This approach allowed for a direct comparison of species composition and diversity patterns between the current study area and previously documented sites in the province.

3. Results

3.1. Diversity of Fabaceae in Maha Sarakham Province

A total of 83 taxa belonging to 52 genera of the family Fabaceae were recorded in Maha Sarakham Province (Figure 2 and Table 2). Among these, Dalbergia was the most diverse genus with 7 taxa (8.43%), followed by Albizia with 4 taxa (4.82%). The genera Bauhinia, Crotalaria, Mimosa, Senegalia, Senna, and Vigna each contained 3 taxa (3.61%). Genera represented by 2 species (2.41%) each were Acacia, Biancaea, Butea, Cassia, Erythrophleum, Peltophorum, Phyllodium, Pterocarpus, Sesbania, and Tephrosia. The remaining 34 genera—Abrus, Adenanthera, Afzelia, Akschindlium, Arachis, Barnebydendron, Brachypterum, Brownea, Caesalpinia, Cajanus, Delonix, Dialium, Glycine, Indigofera, Lablab, Lathyrus, Leucaena, Macroptilium, Mucuna, Neptunia, Pachyrhizus, Phanera, Phaseolus, Piliostigma, Pithecellobium, Psophocarpus, Pueraria, Samanea, Sindora, Spatholobus, Stylosanthes, Tamarindus, Thailentadopsis, and Xylia—were represented by one taxon (1.20%) each.

Figure 2.

Representative examples of Fabaceae recorded in Mahasarakham Province, selected to illustrate the morphological and ethnobotanical diversity of the family. Photographs by Tammanoon Jitpromma.

Table 2.

Ethnobotanical data of selected Fabaceae species in Maha Sarakham Province, Thailand. Includes scientific and vernacular names, distribution in Thailand, life form, resource, used parts, utilization, Species Use Value (SUV), Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC), and voucher specimen numbers.

The Fabaceae species recorded in Maha Sarakham Province represented four distinct life forms (Table 2). Trees constituted the largest group, accounting for 42 taxa (50.60%), reflecting the dominance of woody perennials within the local vegetation and their multiple roles in timber, shade, and traditional uses. Climbers formed the second largest category with 18 taxa (21.69%), many of which are used as food or medicinal plants. Shrubs comprised 16 taxa (19.28%), while herbs were the least represented group, with only 7 taxa (8.43%), primarily consisting of short-lived or seasonal taxa commonly utilized for food and ethnomedicinal purposes.

Regarding resource origin, the recorded Fabaceae species were classified into two categories: cultivated and wild (Table 2). Cultivated species predominated, accounting for 48 taxa (57.83%), including 23 introduced, 23 native, 1 of doubtful origin, and 1 endemic (Thailentadopsis tenuis), highlighting the community’s reliance on domesticated taxa for food, fodder, and economic purposes. In contrast, 35 taxa (42.17%) were wild, reflecting the continued importance of natural habitats as sources of medicine, ornamental, and utility plants.

The distribution of Fabaceae species in Thailand is presented in Table 1. Native species accounted for 52 taxa (62.65%), indicating that most taxa are naturally occurring in the region. Introduced species comprised 30 taxa (36.15%), reflecting the influence of cultivation and human-mediated plant introductions. Only one species (1.20%) was classified as doubtful, suggesting uncertainty regarding its origin or establishment in the area.

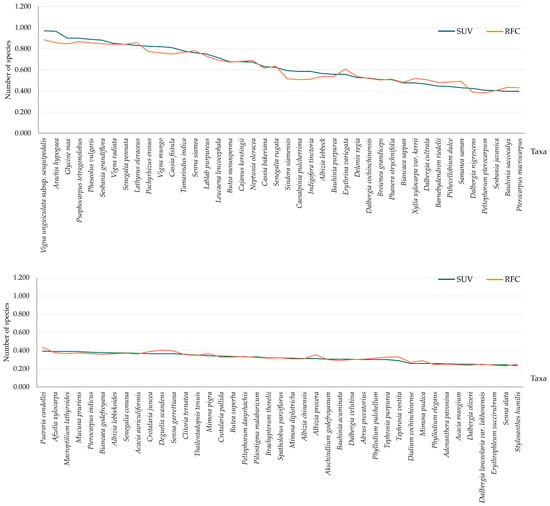

3.2. Species Use Value (SUV) of Fabaceae in Maha Sarakham Province

The Species Use Value (SUV), a quantitative index representing the frequency and intensity of species use by informants, ranged from 0.235 to 0.969 (Table 2). The highest SUV value (0.969) was recorded for Vigna unguiculata subsp. sesquipedalis, followed closely by Arachis hypogaea (0.965), Glycine max (0.900), Psophocarpus tetragonolobus (0.900), and Phaseolus vulgaris (0.888). These species are primarily cultivated legumes and vegetables that play vital roles in local food systems and daily diets. A total of 12 taxa (14.46%) exhibited high SUV values (≥0.80), indicating that they are widely recognized and consistently utilized across the community. These include important edible and economic species such as Vigna unguiculata subsp. sesquipedalis, Arachis hypogaea, Glycine max, Psophocarpus tetragonolobus, Phaseolus vulgaris, and Sesbania grandiflora, which are valued for their nutritional and agricultural importance.

Medium-use species, with SUV values ranging from 0.50 to 0.79, accounted for 19 taxa (22.89%). Representative species include Tamarindus indica (0.781), Senna siamea (0.762), Lablab purpureus (0.750), Leucaena leucocephala (0.715), and Butea monosperma (0.677). These species are generally well-known to the community and serve a variety of purposes, including food, fodder, shade, and ornamental uses, though they are not as consistently used as the high-SUV taxa.

In contrast, species with low SUV values (<0.50) comprised the largest proportion, including 52 taxa (62.65%) of the total recorded Fabaceae. Examples include Biancaea sappan (0.477), Xylia xylocarpa var. kerrii (0.477), Dalbergia cultrata (0.465), and Peltophorum pterocarpum (0.408). These species are typically wild, infrequently encountered, or used for specialized purposes such as timber, medicine, or ornamental planting. Overall, most Fabaceae species in Maha Sarakham Province exhibit low to moderate SUV values, while a smaller number of cultivated and multipurpose species demonstrate high SUV, reflecting their central importance to local livelihoods, food security, and traditional knowledge systems.

3.3. Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC) of Fabaceae in Maha Sarakham Province

Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC) values ranged from 0.885 to 0.231, while Species Use Value (SUV) values ranged from 0.969 to 0.235 (Table 2 and Figure 3). The species with the highest RFC was Vigna unguiculata subsp. sesquipedalis (0.885), which also recorded the highest SUV (0.969), reflecting its universal recognition and importance as a key dietary and economic crop in local communities. Other frequently cited species included Arachis hypogaea (RFC = 0.858, SUV = 0.965), Glycine max (0.846, 0.900), Psophocarpus tetragonolobus (0.865, 0.900), and Phaseolus vulgaris (0.858, 0.888), all of which are widely cultivated and consumed legumes contributing significantly to household nutrition and livelihoods.

Figure 3.

Comparison between the Species Use Value (SUV) and Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC) of 83 Fabaceae species documented in Maha Sarakham Province. The figure illustrates species that are both frequently cited and widely utilized, as well as those showing high use values despite lower citation frequencies. SUV values range from 0.235 to 0.969.

At the lower end of the spectrum, species such as Erythrophleum succirubrum (RFC = 0.238, SUV = 0.242), Senna alata (0.231, 0.242), and Stylosanthes humilis (0.250, 0.235) were less frequently cited and showed lower use values, indicating either specialized applications or limited cultural familiarity.

When comparing RFC and SUV across all 83 taxa, a consistent pattern emerged: species frequently mentioned by informants generally exhibited high use values, suggesting strong alignment between community recognition and practical utilization. For instance, Arachis hypogaea and Vigna unguiculata subsp. sesquipedalis demonstrated both high citation rates and intensive use, reflecting their multifunctional roles in food, fodder, and traditional medicine. Conversely, some species showed notable variation between RFC and SUV; for example, Cassia fistula (RFC = 0.750, SUV = 0.812) and Senna siamea (0.781, 0.762) had higher use values relative to citation frequency, suggesting specialized but valued uses within local ethnobotanical knowledge systems.

3.4. Utilization of Fabaceae in Maha Sarakham Province

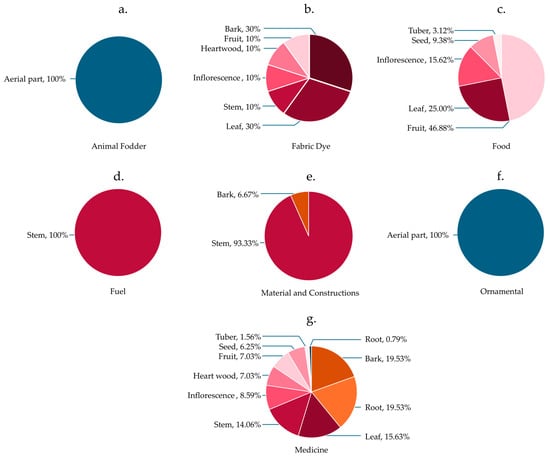

3.4.1. Fabaceae Species Used as Animal Fodder

A total of six Fabaceae species were identified as important sources of animal fodder in Maha Sarakham Province (Table 2), namely Abrus precatorius, Acacia auriculiformis, A. mangium, Adenanthera pavonina, Afzelia xylocarpa, and Akschindlium godefroyanum. The aerial parts of all species (100%) were reported as the main plant part used for feeding livestock (Figure 4), such as cattle, buffaloes, and goats. These species are particularly valued during the dry season when herbaceous fodder becomes limited. Acacia auriculiformis and A. mangium are preferred for their fast growth and high leaf biomass, while Afzelia xylocarpa and Adenanthera pavonina are appreciated in agroforestry systems for providing both shade and nutritious foliage. The predominance of leaf use emphasizes the importance of Fabaceae trees and shrubs in sustaining traditional livestock management and maintaining year-round fodder availability in the province.

Figure 4.

Distribution of plant parts employed in different Fabaceae use categories in Maha Sarakham Province: (a) animal fodder; (b) fabric dye; (c) food; (d) fuel; (e) material and construction; (f) ornamental; (g) medicine.

3.4.2. Fabaceae Species Used as Fabric Dye

Nine Fabaceae species were recorded as sources of natural fabric dyes in Maha Sarakham Province. The genus Pterocarpus contributed the highest number of dye-yielding species (two species), while the remaining genera were each represented by a single species. These include Biancaea sappan, Cassia fistula, Clitoria ternatea, Indigofera tinctoria, Leucaena leucocephala, Peltophorum dasyrhachis, Pterocarpus indicus, Pterocarpus macrocarpus, and Senna siamea. Various plant parts were employed in dye preparation, with bark and leaves being the most frequently used, followed by fruit, heartwood, inflorescence, and stem (Figure 4). The utilization of multiple plant parts underscores the versatility of Fabaceae species as natural dye sources and their cultural relevance in traditional textile coloration practices across rural communities of Maha Sarakham Province.

Traditional dyeing methods typically involved boiling or fermenting plant materials to extract pigments, filtering the solution, and immersing silk or cotton threads in the resulting dye bath. Mordants such as alum or lime water were frequently used to enhance color fixation and durability. The resulting hues varied among species: Biancaea sappan and Peltophorum dasyrhachis produced red to pink tones; Cassia fistula and Pterocarpus species yielded brown to dark brown shades; Clitoria ternatea generated grey-black tones; Indigofera tinctoria produced characteristic blue hues; Leucaena leucocephala provided yellow tones; and Senna siamea imparted a green color. Detailed descriptions of dye preparation methods are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Fabaceae species used for fabric dyeing in Maha Sarakham Province, including used parts, preparation, and resulting colors.

3.4.3. Fabaceae Species Used as Food

A total of 27 Fabaceae taxa were documented as food plants in Maha Sarakham Province (Table 2). The genus Vigna contributed the highest number of edible species (three species), followed by Bauhinia and Sesbania with two species each, while the remaining genera were each represented by a single species. The documented species include Adenanthera pavonina, Albizia procera, Arachis hypogaea, Bauhinia acuminata, B. saccocalyx, Cajanus kerstingii, Clitoria ternatea, Dialium cochinchinense, Glycine max, Lablab purpureus, Lathyrus oleraceus, Leucaena leucocephala, Neptunia oleracea, Pachyrhizus erosus, Phaseolus vulgaris, Pithecellobium dulce, Psophocarpus tetragonolobus, Senegalia pennata, Senna siamea, Sesbania grandiflora, S. javanica, Sindora siamensis, Tamarindus indica, Vigna mungo, V. radiata, V. unguiculata subsp. sesquipedalis, and Xylia xylocarpa var. kerrii.

The most commonly consumed plant parts were fruits, followed by leaves, inflorescences, seeds, and tubers (Figure 4). These edible parts are utilized in various forms, such as fresh vegetables, flavoring agents, and staple food ingredients. Species such as Neptunia oleracea, Senegalia pennata, and Sesbania grandiflora are commonly consumed as vegetables, either fresh or cooked, while legume crops, including Arachis hypogaea, Glycine max, Lablab purpureus, and Vigna radiata, are valued for their nutritional content and are used in desserts, as snacks, or cooked as side vegetables. Fruits of Tamarindus indica and Pithecellobium dulce are eaten fresh, used as sour-flavoring ingredients, or incorporated into local dishes, and seeds of some species, including Adenanthera pavonina and Tamarindus indica, are roasted and eaten as snacks. The predominance of fruit and leaf use underscores the contribution of Fabaceae species to local diets, food culture, and household food security in Maha Sarakham Province. Detailed descriptions of food preparation methods are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Fabaceae species used as food in Maha Sarakham Province, including used parts and method of use.

3.4.4. Fabaceae Species Used as Fuel

Several species of the Fabaceae family are utilized as fuelwood in the study area (Table 2). Among the genera, Acacia and Peltophorum are represented by two species each, while the remaining genera are represented by a single species, totaling 14 taxa across 12 genera. The documented species include Acacia auriculiformis, A. mangium, Dalbergia cochinchinensis, Leucaena leucocephala, Mimosa pigra, Peltophorum dasyrhachis, P. pterocarpum, Pithecellobium dulce, Pterocarpus macrocarpus, Samanea saman, Senna siamea, Sindora siamensis, Tamarindus indica, and Xylia xylocarpa var. kerrii. All these species are harvested primarily for their stems (100%), which serve as a source of fuel (Figure 4).

3.4.5. Fabaceae Species Used as Material and Constructions

A total of 15 Fabaceae species were documented for use as material and construction materials (Table 2). These species belong to 12 genera, with Acacia and Pterocarpus represented by two species each, while the remaining genera—Butea, Cassia, Crotalaria, Dalbergia, Deguelia, Mimosa, Peltophorum, Samanea, Senna, Sindora, and Xylia—are represented by a single taxon each. Stems were the predominant plant part used, while bark was utilized in only one species (Figure 4).

The stems of Acacia auriculiformis and A. mangium are primarily used for furniture and light construction, whereas the stems of Cassia fistula, Peltophorum dasyrhachis, Pterocarpus indicus, P. macrocarpus, Sindora siamensis, and Xylia xylocarpa var. kerrii are processed into household items, tools, agricultural implements, and used in house and bridge construction. Other species have more specialized uses, such as Crotalaria juncea for paper production, Deguelia scandens for agricultural tools, and Mimosa pigra for fences and vegetable supports. Bark of Butea monosperma is used for making ropes and paper. Additionally, stems of Dalbergia cochinchinensis, Samanea saman, and Senna siamea are valued for furniture and construction purposes. Detailed descriptions of the methods of use for each species are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Fabaceae species used as material and constructions in Maha Sarakham Province, including used parts and method of use.

3.4.6. Fabaceae Species Used for Ornamental

A total of 16 Fabaceae species belonging to 14 genera were recorded as ornamental plants in Maha Sarakham Province (Table 2). The genera Bauhinia and Cassia contributed the highest number of species (two species each), while the remaining genera—Albizia, Butea, Caesalpinia, Clitoria, Dalbergia, Erythrina, Peltophorum, Phyllodium, Samanea, Senna, Spatholobus, and Tamarindus—were each represented by a single species. All species were utilized as aerial parts (100%) (Figure 4), primarily cultivated for their aesthetic appeal, shade, and landscaping purposes in home gardens, temples, and along roadsides. Cassia fistula, Cassia bakeriana, and Butea monosperma are particularly admired for their striking inflorescences and cultural symbolism. Additionally, Tamarindus indica is frequently planted as a living fence or boundary tree, highlighting both its ornamental and practical significance.

3.4.7. Fabaceae Species Used as Medicine

A total of 54 Fabaceae species belonging to 39 genera were documented as being used in traditional medicine in Maha Sarakham Province (Table 2). The genus Dalbergia exhibited the highest diversity, represented by five medicinal species, followed by Senna (three species). Several genera—including Albizia, Bauhinia, Biancaea, Butea, Cassia, Mimosa, Peltophorum, Pterocarpus, and Senegalia—were represented by two species each. The remaining 27 genera contributed to a single medicinal species.

An analysis of the plant parts used in traditional medicinal practices revealed that bark and roots were the most commonly utilized parts, followed by leaves and stems, highlighting the prominence of vegetative parts in local healing traditions. Inflorescences, fruits, and heartwood were also used, while seeds and tubers were less frequently employed. One additional record of root use was documented separately, possibly due to a duplicate entry or categorization nuance (Figure 4).

3.5. Fidelity Level (%FL) of Fabaceae Used as Medicine in Maha Sarakham Province

The analysis of Fidelity Level (FL) among the documented Fabaceae species provides key insights into the degree of cultural consensus regarding specific medicinal uses (Table S1). As a widely applied quantitative index in ethnobotany, FL reflects the informants’ agreement on the use of plant species for treating distinct ailments, thus serving as an indicator of perceived efficacy and cultural importance.

In this study, several species achieved the maximum FL value of 100%, indicating unanimous agreement among informants for their specific medicinal applications. These include Abrus precatorius (used externally for skin disorders via root application), Albizia lebbeck (seed oil applied for skin issues).

High FL values were observed in several species, including Bauhinia saccocalyx (leaves used for nutritional and blood-related purposes), Brachypterum thorelii (inflorescence for gastrointestinal health), Butea monosperma (bark used externally for skin conditions), Dalbergia nigrescens (bark decoction for gastrointestinal ailments), D. velutina (root decoction for urinary and reproductive disorders), Phyllodium elegans (root decoction for gastrointestinal issues), Piliostigma malabaricum (leaf decoction for gynecological disorders), Senegalia comosa (root decoction for gastrointestinal uses), and Tephrosia vestita (leaves crushed and applied externally for skin conditions). These high FL values underscore strong cultural validation and the significant role these species play in local healthcare practices.

Several other species exhibited notably high FL values, such as Akschindlium godefroyanum (FL = 64.86%) for the treatment of gastrointestinal disorders using root decoctions, and Biancaea sappan (FL = 78.05%) for treating musculoskeletal and joint ailments with powdered stem preparations mixed with liquor. These results point to a high level of confidence in the traditional effectiveness of these treatments.

Moderate FL values (40–70%) were observed in widely cited species with multiple reported uses. For instance, Acacia auriculiformis showed FL values of 42.68% for external treatment of skin issues and 57.32% for gastrointestinal disorders. Similarly, Barnebydendron riedelii displayed FL values between 29.03% and 37.63% across various uses of bark, root, and heartwood for gastrointestinal, antipyretic, and blood-related applications.

Lower FL values (<40%) were generally associated with species used for a broader range of therapeutic categories, reflecting more diverse applications and hence, lower informant consensus. For example, Tamarindus indica exhibited a wide array of uses—ranging from infection and gastrointestinal issues to cardiovascular health and poisoning—resulting in FL values between 9.68% and 20.65% depending on the plant part and ailment.

These patterns highlight both the cultural salience of certain Fabaceae species and the nuanced, multi-functional roles many play in traditional medicine. A detailed summary of the species used parts, preparation methods, therapeutic indications, and corresponding Fidelity Levels is presented in Table S1.

3.6. Informant Consensus Factor (Fic) of Fabaceae Used as Medicine in Maha Sarakham Province

The informant consensus factor (Fic) was calculated for Fabaceae species used in treating various ailments in Maha Sarakham Province (Table 6). High Fic values, approaching 1.00, indicate strong agreement among informants regarding the use of particular species for specific health conditions. In this study, the highest consensus was observed for the treatment of cardiovascular disorders (Fic = 1.00) with a single species reported. Similarly, cancer disorders (Fic = 0.99) and respiratory disorders (Fic = 0.98) showed very high consensus among informants. Other ailment categories, including poisoning or toxicological disorders, skin disorders, febrile disorders, musculoskeletal disorders, infectious, parasitic, and immune disorders, eye disorders, and gastrointestinal disorders, had Fic values of 0.97, indicating substantial agreement among participants. Nutritional and blood disorders and obstetric, gynecological, and urinary disorders had slightly lower but still high Fic values of 0.96. Overall, these results reflect a strong consensus among local informants on the medicinal use of Fabaceae species across multiple health categories.

Table 6.

Informant consensus factor (Fic) of Fabaceae used as medicine.

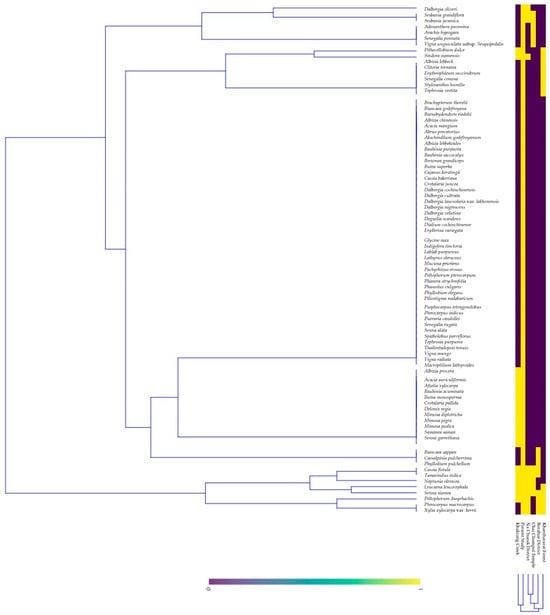

3.7. Comparison of the Present Findings with Previous Studies

A comparative heatmap analysis was conducted to evaluate the similarity of Fabaceae species documented in the present study with previous ethnobotanical surveys in Maha Sarakham Province (Figure 5), including studies in Khanthararat Public Benefit Forest, Kantarawichai District [6]; Na Chueak District [10]; Borabue District [31]; Chai Chumphol Temple Community Market [32]; and communities surrounding Khakrang Creek, Mueang District [33]. For the UPGMA analysis, a data matrix was constructed using presence/absence data (1 = species present, 0 = species absent) for each Fabaceae species across the surveyed locations. The resulting dendrograms illustrate species similarity between locations, showing how species composition clusters across the study area. The two dendrograms presented side-by-side compare (i) similarity among species based on their distribution across sites and (ii) similarity among locations based on the species they share.

Figure 5.

Heatmap analysis of Fabaceae species compared with previous ethnobotanical studies conducted in Maha Sarakham Province. Yellow indicates presence, while purple indicates absence.

The analysis revealed both overlapping and distinct species compositions among the studies. Certain areas and studies showed higher similarity, which may reflect geographic proximity, shared topography, or similar ecological and cultural conditions influencing species utilization. For example, locations in closer proximity tended to cluster together, indicating shared species and ethnobotanical practices, whereas more distant or topographically distinct sites exhibited unique species compositions. Notably, the current survey recorded 44 Fabaceae taxa newly documented for Maha Sarakham Province (Table 2), substantially expanding the known ethnobotanical diversity of this family in the region. These new records underscore the richness of local ecological knowledge and highlight the importance of exploring under-documented areas to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of Fabaceae utilization and distribution in northeastern Thailand.

4. Discussion

4.1. Species Diversity and Genera Composition of Fabaceae

The present study recorded 83 taxa belonging to 52 genera of Fabaceae in Maha Sarakham Province, indicating substantial species richness and reflecting the ecological and ethnobotanical importance of this family in northeastern Thailand. This comprehensive diversity notably exceeds previous localized reports within the province. For instance, earlier ethnobotanical surveys documented only 13 Fabaceae taxa in the Khanthararat Public Benefit Forest, Kantarawichai District [6], 12 taxa in Na Chueak District [10], 9 taxa in Borabue District [31], 11 taxa in Chai Chumphol Temple Community Market [32], and 21 taxa in communities surrounding Khakrang Creek, Mueang District [33]. Such comparisons clearly demonstrate that the present province-wide assessment captures a broader representation of Fabaceae diversity than prior studies limited to specific localities. The difference may be attributed to variations in survey scope, habitat types, and sampling intensity, as well as the inclusion of both wild and cultivated species in the current work.

The genus Dalbergia emerged as the most species-rich, followed by Albizia, Bauhinia, Crotalaria, Mimosa, Senegalia, Senna, and Vigna. This dominance pattern corresponds with floristic observations from other tropical and subtropical regions. For example, Dalbergia species have been reported as major constituents of forest ecosystems in India, Myanmar, and Vietnam, and, where they are widely valued for high-quality timber, traditional medicine, and ornamental purposes [34,35,36]. Similarly, Albizia and Vigna exhibit broad ecological adaptability across tropical Asia and Africa, reflecting their importance in agroforestry systems, soil fertility improvement, and subsistence agriculture [37,38].

4.2. Life Forms, Resource Origin, and Native Status of Fabaceae

The Fabaceae species recorded in Maha Sarakham Province encompassed four distinct life forms, with trees representing the largest group (50.6%). This predominance of woody perennials is consistent with the general pattern of tropical and subtropical savanna and dry deciduous ecosystems, where trees often dominate due to their longevity, structural complexity, and multiple utilitarian roles [39]. Trees in the Fabaceae, including genera such as Dalbergia, Pterocarpus, and Albizia, provide not only timber and fuelwood but also shade, fodder, and raw materials for traditional tools and crafts, reflecting their integral role in both ecological functioning and local livelihoods [40].

Climbers, the second most abundant life form (21.7%), contribute significantly to food and medicinal resources. Many climbing Fabaceae, such as Vigna, Mucuna, and Cajanus, are edible or possess pharmacologically active compounds, highlighting the cultural and nutritional importance of this life form [3,41]. Shrubs (19.3%) and herbs (8.4%) were less represented, with herbs primarily comprising short-lived or seasonal species. Despite their lower abundance, these herbaceous taxa are often highly valued in ethnomedicine and local diets, providing flexible and readily accessible resources throughout the year [42].

Regarding resource origin, the predominance of cultivated species (57.8%) underscores the community’s reliance on domesticated Fabaceae for food, fodder, and economic purposes, such as marketable pulses and ornamentals. The significant proportion of wild species (42.2%) reflects the sustained utilization of natural habitats as reservoirs for medicinal, ornamental, and utility plants, highlighting the continued relevance of in situ biodiversity for traditional knowledge and subsistence strategies [32].

In terms of native status, the majority of species (62.7%) were native to the region, reinforcing the ecological and evolutionary integration of Fabaceae within local vegetation communities. Introduced species (36.2%) illustrate the impact of human-mediated dispersal, agricultural expansion, and historical trade routes in shaping the contemporary flora, consistent with trends observed in other tropical Asian countries, where introduced legumes are widely adopted for food security and agroforestry [43]. Only a single species (1.2%) was classified as doubtful, highlighting minimal uncertainty regarding plant origin and reflecting a relatively well-documented Fabaceae flora in the province.

4.3. Species Use Value (SUV) and Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC) of Fabaceae

The Species Use Value (SUV) and Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC) analyses reveal clear patterns in the utilization of Fabaceae species within Maha Sarakham Province. The highest SUV and RFC values were recorded for Vigna unguiculata subsp. sesquipedalis, Arachis hypogaea, Glycine max, Psophocarpus tetragonolobus, and Phaseolus vulgaris, all of which are widely cultivated legumes with central roles in local diets and household economies. These species’ consistently high use values and citation frequencies underscore their multifunctional significance, including contributions to nutrition, food security, fodder, and traditional medicine. Such patterns are consistent with observations in other tropical regions of Asia and Africa, where similar legumes dominate local agroecosystems and are highly valued for both subsistence and market-oriented purposes [44,45].

A subset of species (14.46% of recorded taxa) exhibited high SUV (≥0.80), reflecting their cultural ubiquity and continuous use. This group includes staple legumes and multipurpose trees such as Sesbania grandiflora, which is valued not only as a food source but also for medicinal and ornamental purposes. The identification of high-SUV species highlights the concentration of ethnobotanical knowledge and reliance on a limited number of versatile taxa, a trend commonly reported in ethnobotanical surveys of Fabaceae in Ghana, India, and Indonesia [46,47].

Species with medium SUV values (0.50–0.79), including Lablab purpureus, Leucaena leucocephala, Senna siamea, and Tamarindus indica are well-recognized in the community and serve multiple roles, such as food, fodder, shade, and ornamental use. While not as intensively used as high-SUV taxa, these species represent a secondary tier of ethnobotanical importance, providing flexibility and resilience in local agroecosystems [10,31,32,33].

The majority of Fabaceae species (62.65%) displayed low SUV (<0.50) and lower RFC values, such as Biancaea sappan, Xylia xylocarpa var. kerrii, and Peltophorum pterocarpum. These taxa are primarily wild, less frequently encountered, or utilized for specialized purposes, including timber, medicine, or ornamental planting. The pattern aligns with general observations in tropical ethnobotany, where wild and less accessible species often have lower use indices despite ecological or pharmacological importance [48].

Comparison of RFC and SUV values revealed that species frequently cited by informants generally exhibited high use values, indicating a strong correspondence between community recognition and practical utilization. Notably, species such as Arachis hypogaea and Vigna unguiculata subsp. sesquipedalis combine high citation and intensive use, reflecting their central role in both cultural and subsistence practices. Conversely, some taxa, including Cassia fistula and Senna siamea, displayed higher SUV relative to RFC, suggesting specialized or context-dependent use known to particular segments of the community, such as traditional healers or experienced cultivators. This divergence highlights the heterogeneity of ethnobotanical knowledge and the presence of niche cultural practices within local communities [49].

4.4. Ethnobotanical Applications of Fabaceae in Maha Sarakham Province

The six Fabaceae species identified as important sources of animal fodder in Maha Sarakham Province emphasize the ecological and economic importance of this family in supporting traditional livestock systems. The predominance of leaf use (100%) aligns with findings from other parts of Southeast Asia and Africa, where Fabaceae species such as Acacia auriculiformis, A. mangium, and Afzelia xylocarpa are recognized for their high protein content and year-round foliage availability [50]. These species also contribute to soil fertility and erosion control in integrated agroforestry systems [51]. The reliance on woody Fabaceae during the dry season underscores their resilience and adaptability to seasonal scarcity, ensuring fodder security for livestock-dependent communities in semi-arid landscapes like the Khorat Plateau.

The identification of nine Fabaceae species as natural dye sources highlights the family’s contribution to traditional craftsmanship and cultural heritage in rural Maha Sarakham. The prominence of Pterocarpus sp., Biancaea sappan, and Indigofera tinctoria reflects the persistence of indigenous textile-dyeing traditions across tropical Asia, where these taxa are widely used for red, brown, and blue pigments [52]. Similar applications have been reported from Bhutan, China, and Nepal, where natural dyes are valued for their eco-friendly qualities and cultural symbolism [53,54,55]. The use of various plant parts—especially bark, leaves, and heartwood—illustrates local knowledge of pigment extraction and mordanting techniques, ensuring color permanence and diversity. Such practices demonstrate the enduring socio-economic importance of Fabaceae in rural handicraft economies and sustainable textile production.

The documentation of 27 edible Fabaceae taxa reflects the family’s critical role in food security, nutrition, and culinary diversity in Northeastern Thailand. The predominance of fruits and leaves as edible parts (50% and 25%, respectively) indicates their importance as readily available and renewable food sources. Similar patterns have been reported in Southeast Asia, particularly in East Timor, where diverse leguminous species—including food beans such as Sesbania, Tamarindus, and Vigna—play an important role in rural diets and cashew-based agroforestry systems, contributing to both nutrition and food security [43]. Leguminous crops like Arachis hypogaea, Glycine max, and Lablab purpureus provide essential proteins and are integrated into both subsistence and commercial farming systems [56]. Furthermore, wild or semi-domesticated species such as Neptunia oleracea and Senegalia pennata enhance dietary diversity and serve as seasonal vegetables. The extensive utilization of Fabaceae as food underscores the intersection between biodiversity conservation and local food culture [57].

Fourteen Fabaceae species were identified as fuelwood sources, with Acacia, Peltophorum, and Pterocarpus being particularly significant. The exclusive use of stems (100%) is consistent with ethnobotanical reports from tropical Africa and Asia, where Fabaceae wood is favored for its density, calorific value, and slow-burning properties [58,59]. The widespread reliance on these species illustrates their dual function in providing household energy and contributing to rural livelihoods. Integrating fast-growing Fabaceae trees into community forestry programs could support sustainable energy strategies in Northeastern Thailand, particularly where wood remains the primary cooking fuel [60].

Fifteen Fabaceae species were utilized for construction and material purposes, reaffirming the family’s pivotal role in providing durable timber and versatile raw materials. Species such as Xylia xylocarpa, Dalbergia cochinchinensis, and Sindora siamensis are highly valued for furniture and house construction, reflecting their strength, termite resistance, and aesthetic appeal. This finding is consistent with previous studies that have highlighted the importance of Fabaceae species as valuable sources of construction materials and durable wood in traditional architecture and craftsmanship [61].

Sixteen Fabaceae species were cultivated as ornamentals, notably Cassia fistula, C. bakeriana, and Butea monosperma, admired for their vibrant floral displays and cultural symbolism. The “Dok Khoon” (C. fistula) serves as Thailand’s national flower and holds ceremonial importance [62]. Likewise, B. monosperma is revered across South and Southeast Asia as a sacred tree symbolizing purity and divine energy. Its flowers are offered in rituals dedicated to the goddess Kali, and its wood and leaves are used in sacred fires and religious utensils. Thus, B. monosperma embodies both aesthetic and spiritual values deeply rooted in Buddhist and Hindu traditions [63]. The predominance of aerial parts use (100%) highlights their integration into landscaping and urban greening. Such multifunctionality—combining aesthetic, cultural, and ecological values—positions Fabaceae as vital components of both traditional and modern Thai gardens [64].

A remarkable 54 Fabaceae species were employed in traditional medicine, indicating the family’s central role in local ethnopharmacology. The dominance of bark and roots (19.53% each) as medicinal materials mirrors findings across tropical Asia and Africa, where these parts are associated with potent bioactive compounds [65,66]. Genera such as Bauhinia, Dalbergia, and Senna exhibit particularly high medicinal diversity, with uses ranging from anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial to gastrointestinal treatments [67,68,69]. This diversity of uses and species reflects deep traditional ecological knowledge and the adaptive integration of Fabaceae into local healthcare systems. However, the frequent use of roots and bark also raises conservation concerns, emphasizing the need for sustainable harvesting practices to ensure long-term resource availability.

4.5. Fidelity Level (FL) of Fabaceae Species Used as Medicine

The analysis of Fidelity Level (FL) in the present study highlights the degree of cultural agreement on the medicinal uses of Fabaceae species in Maha Sarakham Province. High FL values indicate strong consensus among informants, reflecting both the perceived efficacy and the cultural importance of certain taxa. Species such as Abrus precatorius and Albizia lebbeck achieved the maximum FL value of 100%, demonstrating unanimous agreement for their applications in treating skin disorders. Similarly, species including Bauhinia saccocalyx, Brachypterum thorelii, Butea monosperma, Dalbergia nigrescens, D. velutina, Phyllodium elegans, Piliostigma malabaricum, Senegalia comosa, and Tephrosia vestita exhibited high FL values, indicating strong cultural validation and consistent use for specific health conditions [70].

Species with moderate FL values (40–70%) were often widely cited but employed for multiple therapeutic purposes, such as Acacia auriculiformis and Barnebydendron riedelii. In contrast, species with low FL values (<40%), including Tamarindus indica, were associated with a broad spectrum of uses, reflecting lower consensus due to their multifunctional roles in traditional medicine. These patterns suggest that while some Fabaceae species are highly specialized and culturally salient for ailments, others are valued for diverse applications across multiple health categories. Overall, FL analysis underscores the importance of certain key species in local healthcare systems and highlights the concentration of ethnomedicinal knowledge within a limited set of culturally recognized taxa [71].

4.6. Informant Consensus Factor (Fic) of Fabaceae Species Used as Medicine

The Informant Consensus Factor (Fic) provides complementary insights into the agreement among local informants regarding the medicinal applications of Fabaceae species. High Fic values (close to 1.00) indicate a strong consensus, suggesting both reliable knowledge transmission and perceived effectiveness of the plants [72]. In this study, the highest consensus was observed for cardiovascular disorders (Fic = 1.00), followed closely by cancer disorders (0.99) and respiratory disorders (0.98). Other health categories—including poisoning or toxicological disorders, skin disorders, febrile disorders, musculoskeletal disorders, infectious, parasitic, and immune disorders, eye disorders, and gastrointestinal disorders—showed Fic values of 0.97, while nutritional and blood disorders and obstetric, gynecological, and urinary disorders had slightly lower but still high consensus (0.96).

These results demonstrate that Fabaceae species are widely recognized across the community for their medicinal value, with particularly strong agreement for specific ailments. The high Fic values align with the patterns observed in FL analysis, emphasizing that certain species not only hold cultural significance but also enjoy widespread acceptance as effective remedies [73]. Together, the FL and Fic data underscore the central role of Fabaceae in traditional medicine within Maha Sarakham Province, reflecting a well-established and consistent body of ethnobotanical knowledge.

4.7. Comparison with Previous Ethnobotanical Surveys in Maha Sarakham Province

The heatmap comparison revealed both overlaps and clear differences between this province-wide survey and earlier, site-specific ethnobotanical studies in Maha Sarakham, and notably documented 44 Fabaceae taxa not previously recorded for the province. Such an expansion of the local checklist is consistent with the idea that Indigenous and local knowledge (ILK) substantially increases the efficiency and completeness of biodiversity documentation. As Copete et al. [74] argue, long-standing local classification systems and day-to-day interactions with the environment allow Indigenous and local peoples to detect, name and use taxa that are often overlooked by episodic scientific sampling. In practice, this means that broader, community-engaged surveys—which sample a wider range of land-use types (homegardens, markets, fallows, sacred groves, etc.) and draw on multiple knowledge holders—are more likely to reveal cryptic, seasonal, or semi-domesticated species that smaller, site-limited studies miss.

Two aspects of Copete et al.’s synthesis are especially useful for interpreting our results. First, ILK frequently contains fine-grained taxonomic distinctions and ecological observations that mirror or even exceed Linnaean resolution; such knowledge helps locate species that occur at low density or that are used in very specific cultural contexts (e.g., seasonal vegetables or multipurpose trees used only by particular households) [75]. Second, the spatial and cultural heterogeneity of traditional knowledge leads to variation among local inventories: different communities emphasize different taxa depending on livelihood, microhabitat access, and cultural preference [76]. This heterogeneity explains why the heatmap shows both strong overlaps for some commonly used genera (e.g., Cassia, Leucaena, and Senna) and unique species lists in each study area.

The detection of 44 new local records therefore likely reflects a combination of (1) broader spatial coverage and inclusion of diverse use-contexts in the present survey; (2) engagement—implicit or explicit—with a wider set of knowledge holders (market vendors, home-gardeners, herbalists); and (3) targeted searching in habitat types or cultivation niches under-sampled by earlier projects. Copete et al. [74] emphasize that participatory approaches and the formal involvement of local experts (paraecologists, parataxonomists, local collectors) make such comprehensive inventories both feasible and more equitable. Our findings thus reinforce the recommendation that ethnobotanical and floristic studies adopt more inclusive, community-based protocols to capture the full spectrum of use and occurrence.

4.8. Suggestions for Future Research

The findings of this study provide a comprehensive overview of the ethnobotanical importance of Fabaceae in Maha Sarakham Province. However, several areas warrant further investigation to enhance understanding and promote sustainable utilization of these species:

- Phytochemical and pharmacological validation: Many species with high FL and Fic values, such as Abrus precatorius, Albizia lebbeck, and Bauhinia saccocalyx, show strong cultural consensus for treating specific ailments. Future studies should investigate their bioactive compounds and pharmacological activities to validate traditional uses and potentially identify novel therapeutic agents.

- Nutritional and agronomic assessment: Species commonly used as food and fodder, including Vigna unguiculata subsp. sesquipedalis, Arachis hypogaea, and Sesbania grandiflora, could be evaluated for nutrient content, yield optimization, and resilience under local agroecological conditions to support food security and sustainable agriculture.

- Conservation and sustainable management: Several Fabaceae species, particularly those used for timber, construction, and fuel, face pressure from overharvesting. Research on population status, reproductive biology, and community-based conservation strategies is essential to ensure long-term availability.

- Ethnobotanical knowledge transmission: Investigation into intergenerational knowledge transfer could help us understand how traditional practices are maintained or lost over time, particularly for less frequently used species with low FL values.

- Broader geographic and comparative studies: Expanding surveys to neighboring provinces or cross-cultural studies would allow for comparative analyses, helping to identify shared ethnobotanical practices, unique local uses, and potential species of regional or national importance.

In addition, some Fabaceae species recorded in this study, such as Leucaena leucocephala, are reported as naturalized or potentially invasive in certain areas of Thailand, yet they remain important to local livelihoods. These species are widely used for food, fodder, fuelwood, or traditional medicine, reflecting their practical value to communities. Their presence highlights the need for future research on locally appropriate management approaches that support continued utilization while considering potential ecological implications.

Although endemic Fabaceae species are generally limited in distribution, Thailentadopsis tenuis—a species endemic to Thailand—was recorded within the study area. The presence of such narrowly distributed taxa highlights the importance of future research evaluating their conservation status, traditional uses, and potential vulnerabilities. Understanding how endemic or regionally restricted species are utilized is essential to ensure that cultural practices and local harvesting do not inadvertently contribute to population decline.

By addressing these areas, future research can strengthen the integration of traditional knowledge with modern scientific approaches, support biodiversity conservation, and enhance the sustainable use of Fabaceae species in northeastern Thailand.

5. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive ethnobotanical assessment of the Fabaceae family in Maha Sarakham Province, documenting 83 taxa across 52 genera and revealing the family’s profound ecological and cultural significance in Northeastern Thailand. The coexistence of native and introduced species, along with both wild and cultivated forms, underscores the adaptability and resilience of Fabaceae in sustaining local livelihoods, food security, and traditional practices.

Quantitative analyses of Species Use Value (SUV), Relative Frequency of Citation (RFC), Fidelity Level (FL), and Informant Consensus Factor (Fic) highlight the prominence of species such as Vigna unguiculata subsp. sesquipedalis, Arachis hypogaea, Glycine max, and Sesbania grandiflora, which serve as nutritional staples and economic resources. Likewise, medicinally significant taxa such as Abrus precatorius, Albizia lebbeck, and Bauhinia saccocalyx exhibit strong cultural consensus, affirming the deep interlinkage between ethnobotanical knowledge and local healthcare systems.

The wide range of uses—including food, fodder, timber, fuel, dye, ornamental, and medicinal applications—reflects the multifunctionality of Fabaceae and its integral role in agroecological and cultural systems. This diversity illustrates how rural communities maintain ecological balance and economic stability through versatile plant use, reflecting the family’s enduring relevance in biocultural landscapes.

Ultimately, this study underscores the essential role of Fabaceae in promoting biodiversity conservation, sustainable resource use, and cultural continuity in Northeastern Thailand. Future research should explore phytochemical and pharmacological validation of high-FL species, nutritional and agronomic evaluation of edible legumes, and sustainable management of economically important taxa. In addition, studies on knowledge transmission and intergenerational learning could strengthen community-based conservation and ensure the continuity of ethnobotanical heritage. Integrating traditional wisdom with scientific inquiry will be vital for advancing sustainable development, food sovereignty, and health security in the region.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/d17120838/s1, Table S1: Fidelity Level (%FL) of Fabaceae in Maha Sarakham Province, Thailand.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S., S.S., S.M., K.C. and T.J.; methodology, T.J.; software, T.J.; validation, S.S. and T.J.; formal analysis, P.S., S.S., S.M., K.C. and T.J.; investigation, S.S. and T.J.; resources, S.S. and T.J.; data curation, T.J.; writing—original draft preparation, T.J.; writing—review and editing, T.J.; visualization, T.J.; supervision, P.S. and S.S.; project administration, T.J.; funding acquisition, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Thailand Science Research and Innovation (TSRI) and Mahasarakham University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are contained within the article. Any further inquiries may be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Walai Rukhavej Botanical Research Institute, Mahasarakham University, for laboratory facilities and access to a stereo microscope, and Mahasarakham University for financial support. We are grateful to Saisamorn Jitpromma for assistance during fieldwork and to Phiphat Sonthongphithak for guidance in QGIS training. Our sincere appreciation also goes to the local communities of Maha Sarakham Province for their cooperation and for sharing traditional knowledge on the Fabaceae species.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, R.; Jiang, K.-W.; Qi, J.; Hu, Y.; Guo, J.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, T.; Egan, A.N.; Yi, T.-S.; et al. Nuclear phylotranscriptomics and phylogenomics support numerous polyploidization events and hypotheses for the evolution of rhizobial nitrogen-fixing symbiosis in Fabaceae. Mol. Plant 2021, 14, 748–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, B.N.; Simms, E.L.; Komatsu, K.J. More Than a Functional Group: Diversity within the Legume–Rhizobia Mutualism and Its Relationship with Ecosystem Function. Diversity 2020, 12, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbole, O.O.; Akin-Ajani, O.D.; Ajala, T.O.; Ogunniyi, Q.A.; Fettke, J.; Odeku, O.A. Nutritional and pharmacological potentials of orphan legumes: Subfamily Faboideae. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.K.; Elango, D.; Raigne, J.; Van der Laan, L.; Rairdin, A.; Soregaon, C.; Singh, A. Plant-based protein crops and their improvement: Current status and future perspectives. Crop Sci. 2025, 65, e21389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grygier, A.; Chakradhari, S.; Ratusz, K.; Rudzińska, M.; Patel, K.S.; Lazdiņa, D.; Segliņa, D.; Górnaś, P. Evaluation of Selected Medicinal, Timber and Ornamental Legume Species’ Seed Oils as Sources of Bioactive Lipophilic Compounds. Molecules 2023, 28, 3994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saensouk, P.; Saensouk, S.; Boonma, T.; Hanchana, K.; Rakarcha, S.; Maknoi, C.; Chanthavongsa, K.; Jitpromma, T. Ecological Analysis and Ethnobotanical Evaluation of Plants in Khanthararat Public Benefit Forest, Kantarawichai District, Thailand. Forests 2025, 16, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisciani, S.; Marconi, S.; Le Donne, C.; Camilli, E.; Aguzzi, A.; Gabrielli, P.; Gambelli, L.; Kunert, K.; Marais, D.; Vorster, B.J.; et al. Legumes and common beans in sustainable diets: Nutritional quality, environmental benefits, spread and use in food preparations. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1385232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N.J.; Cuerrier, A.; Joseph, L. Well Grounded: Indigenous Peoples’ Knowledge, Ethnobiology and Sustainability. People Nat. 2022, 4, 627–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saensouk, S.; Saensouk, P.; Boonma, T.; Rakarcha, S.; Chanthavongsa, K.; Piwpuan, N.; Jitpromma, T. From Ornamental Beauty to Economic and Horticultural Significance: Species Diversity and Ethnobotany of Bignoniaceae in Maha Sarakham Province, Thailand. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saensouk, P.; Saensouk, S.; Boonma, T.; Junsongduang, A.; Appamaraka, S.; Koompoot, K.; Chanthavongsa, K.; Jitpromma, T. Ethnobotany of Lao Isan Ethnic Group from Na Chueak District, Maha Sarakham Province, Northeastern Thailand. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouma, A. Intergenerational Learning Processes of Traditional Medicinal Knowledge and Socio-Spatial Transformation Dynamics. Front. Sociol. 2022, 7, 661992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asigbaase, M.; Adusu, D.; Anaba, L.; Abugre, S.; Kang-Milung, S.; Acheamfour, S.A.; Adamu, I.; Ackah, D.K. Conservation and Economic Benefits of Medicinal Plants: Insights from Forest-Fringe Communities of Southwestern Ghana. Trees For. People 2023, 14, 100462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saensouk, P.; Saensouk, S.; Boonma, T.; Junsongduang, A.; Rakarcha, S.; Chanthavongsa, K.; Jitpromma, T. Zingiberaceae in Roi Et Province, Thailand: Diversity, Ethnobotany, Horticultural Value, and Conservation Status. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viroj, J.; Claude, J.; Lajaunie, C.; Cappelle, J.; Kritiyakan, A.; Thuainan, P.; Chewnarupai, W.; Morand, S. Agro-Environmental Determinants of Leptospirosis: A Retrospective Spatiotemporal Analysis (2004–2014) in Mahasarakham Province (Thailand). Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. 2024. Available online: http://qgis.osgeo.org (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Department of Provincial Administration (DOPA), Thailand. Statistical Yearbook 2023. Available online: https://stat.bora.dopa.go.th/stat/statnew/statMenu/newStat/home.php (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Alexander, S.T.; McCargo, D. Diglossia and Identity in Northeast Thailand: Linguistic, Social, and Political Hierarchy. J. Socioling. 2014, 18, 60–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duangsin, T.; Chantachon, S.; Paengsoi, K. Buddhist Philosophy: A Study of Buddha Images for Perpetuating Buddhism in Isan Society. J. Soc. Sci. 2011, 7, 149–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plant of the World Online, Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Available online: https://powo.science.kew.org (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Tajik, O.; Golzar, J.; Noor, S. Purposive Sampling. Int. J. Educ. Lang. Stud. 2025, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, L.A. Snowball Sampling. Ann. Math. Stat. 1961, 32, 148–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Society of Ethnobiology (ISE). International Society of Ethnobiology Code of Ethics (with 2008 Additions). 2006. Available online: http://ethnobiology.net/code-of-ethics/ (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. Nagoya Protocol on Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from Their Utilization to the Convention on Biological Diversity. United Nations, Montreal. 2011. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/abs/ (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Hoffman, B.; Gallaher, T. Importance indices in ethnobotany. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2007, 5, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardío, J.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. Cultural importance indices: A comparative analysis based on the useful wild plants of Southern Cantabria (Northern Spain). Econ. Bot. 2008, 62, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Beloz, A. Plant use knowledge of the Winikina Warao: The case for questionnaires in ethnobotany. Econ. Bot. 2002, 56, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, M.; Ankli, A.; Frei, B.; Weimann, C.; Sticher, O. Medicinal plants in Mexico: Healers’ consensus and cultural importance. Soc. Sci. Med. 1998, 47, 1859–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://icd.who.int/en (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Friedman, J.; Yaniv, Z.; Dafni, A.; Palewitch, D. A preliminary classification of the healing potential of medicinal plants, based on a rational analysis of an ethnopharmacological field survey among Bedouins in the Negev Desert, Israel. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1986, 16, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sneath, P.H.A.; Sokal, R.R. Numerical Taxonomy; W.H. Freeman: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Thipthamrongsap, W.; Saensouk, S.; Saensouk, P. Diversity and utilization of medicinal plants in Borabue District, Maha Sarakham Province, Northeastern Thailand. Biodiversitas 2025, 26, 3040–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saensouk, P.; Saensouk, S.; Hein, K.Z.; Appamaraka, S.; Maknoi, C.; Souladeth, P.; Koompoot, K.; Sonthongphithak, P.; Boonma, T.; Jitpromma, T. Diversity, Ethnobotany, and Horticultural Potential of Local Vegetables in Chai Chumphol Temple Community Market, Maha Sarakham Province, Thailand. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saensouk, P.; Saensouk, S.; Boonma, T.; Koompoot, K.; Rakarcha, S.; Chanthavongsa, K.; Jitpromma, T. Ethnobotanical knowledge of the Lao Isan ethnic group in communities surrounding Khakrang Creek, Mueang District, Maha Sarakham Province, Northeastern Thailand. Trop. J. Nat. Prod. Res. 2025, 9, 3607–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunkumar, A.N.; Warrier, R.R.; Kher, M.M.; Teixeira da Silva, J.A. Indian rosewood (Dalbergia latifolia Roxb.): Biology, utilisation, and conservation practices. Trees 2022, 36, 883–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thantsin, K.; San, K.A.A.; Aye, Y.Y. Essential improvement of non-timber forest products in Myanmar. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 591, 012031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhung, N.P.; Chi, N.M.; Thu, P.Q.; Thuong, B.H.; Ban, D.V.; Dell, B. Market and policy setting for the trade in Dalbergia tonkinensis, a rare and valuable rosewood, in Vietnam. Trees For. People 2020, 1, 100002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puspitawati, I.R.; Susanto, A. Potential of Albizzia forest in food crops based agroforestry. Int. J. Integr. Sci. 2023, 2, 1903–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprent, J.I.; Odee, D.W.; Dakora, F.D. African legumes: A vital but under-utilized resource. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 1257–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, C.R.; Coelho de Souza, F.; Françoso, R.D.; Maia, V.A.; Pinto, J.R.R.; Higuchi, P.; Silva, A.C.; do Prado Júnior, J.A.; Farrapo, C.L.; Lenza, E.; et al. Functional and structural attributes of Brazilian tropical and subtropical forests and savannas. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 558, 121811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, S.M.; Pieroni, A.; Bussmann, R.W.; Abd-ElGawad, A.M.; El-Ansary, H.O. Integrating traditional ecological knowledge into habitat restoration: Implications for meeting forest restoration challenges. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2023, 19, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]