Abstract

The grasslands and shrublands of northern and central Mexico cover nearly 25% of the country and harbor high biodiversity. However, they are increasingly degraded by agriculture, urbanization, infrastructure development, and water overexploitation. To assess the status of medium- and large-sized mammals in these threatened ecosystems, we quantified species richness, relative abundance, and naïve occupancy across vegetation types and seasons. From April 2023 to February 2024, monthly track surveys and camera trapping were performed, and the data were analyzed in R. We documented 16 species representing four orders and nine families, with Carnivora being the most diverse (eight species). The species richness varied by habitat, ranging from 11 in montane forest to 13 in semi-desert grassland, the latter habitat having the highest Shannon and Simpson indices, particularly in the dry season. Odocoileus virginianus and Sylvilagus audubonii were consistently the most abundant species in montane forest and desert scrub, whereas Cynomys mexicanus predominated in semi-desert grasslands, accounting for >90% of detections during the rainy season. Rare species included Lynx rufus, Taxidea taxus, and Ursus americanus, each with isolated detections. Rarefaction and sample coverage curves approached asymptotes (>99%), indicating sufficient sampling effort. Naïve occupancy and encounter rates were highest for O. virginianus (0.82) and S. audubonii (0.68), with a strong positive correlation between the two metrics (r2 = 0.92). These findings provide robust baseline information on mammalian diversity, abundance, and habitat associations in semi-arid anthropogenic landscapes, supporting future monitoring and conservation strategies.

1. Introduction

The grasslands and shrublands of the arid and semi-arid regions of central and northern Mexico cover nearly 25% of the national territory and support high levels of biodiversity [1,2]. Despite their ecological importance, these ecosystems exhibit increasing degradation driven by population growth and unsustainable resource use, which accelerate biodiversity loss and compromise ecosystem integrity [2]. In semi-arid environments, anthropogenic pressures represent one of the main threats to medium- and large-sized mammals by altering habitat availability, behavioral patterns, and long-term population viability [3,4]. Agricultural expansion, urban development, and transportation infrastructure fragment the landscape, reduce ecological connectivity, and diminish native vegetation cover, thereby restricting access to essential resources such as food, water, and shelter [5,6]. Habitat fragmentation, in turn, promotes population isolation, decreases gene flow, and increases susceptibility to stochastic events [7]. Additional pressures include the overexploitation of water resources, which intensifies physiological stress during critical periods of the year, and illegal hunting and human–wildlife conflicts associated with livestock production, which reduce populations of key species (e.g., Puma concolor, Canis latrans, Ursus americanus) and disrupt trophic interactions [8,9]. Moreover, anthropogenic disturbances frequently facilitate the expansion of generalist or invasive species, displacing specialists and contributing to biotic homogenization [10]. These cumulative impacts, coupled with the high climatic variability characteristic of semi-arid ecosystems, are expected to elevate the risk of local extinctions. In Coahuila, semi-arid grasslands have undergone alterations over the past several decades that have led to a substantial decline in the spatial distribution of biodiversity [2].

The northern Mexican state of Coahuila is notable for its faunal diversity, particularly of mammals. Among the 544 mammal species reported nationwide [11,12], approximately 126 species are found in the state, and nearly 15% of these are endemic to Mexico [13]. According to Mexican legislation, 20 of these species are classified under risk categories [11,13]. Terrestrial mammals are key to ecological stability, functioning as primary dispersers of seeds and organic matter and as regulators of prey and plant populations. Through these dispersal and trophic interactions, they shape population dynamics, stabilize community structure, and sustain the functional integrity and resilience of ecosystems across landscapes [14]. However, intensifying pressures, such as overgrazing, extensive agriculture, and land-use change, continue to degrade habitat quality and reduce functional connectivity across the landscape [15,16]. Specifically, mammal communities in the arid and semi-arid ecosystems of northern Mexico have remained functionally and genetically isolated from contiguous vegetation for decades, increasing their vulnerability to diversity loss, genetic drift, and local extinction [17,18,19]. This historical fragmentation reduces connectivity, alters population dynamics, and complicates recovery from anthropogenic and climatic disturbances [17,19]. For example, endangered species within the grasslands of southern Coahuila, such as the American black bear (Ursus americanus) [11], depend on biological corridors to move between suitable vegetation patches, avoid being road-killed, and maintain genetic exchange [20,21]. Similarly, the Mexican prairie dog (Cynomys mexicanus), which is endemic to northeastern Mexico, plays a keystone ecological role. Through its burrowing activities, it increases biodiversity by modifying the landscape, altering soil composition, enhancing water infiltration, facilitating plant regeneration, and providing refuge for numerous other species [22,23]. Both species are severely threatened by habitat loss and fragmentation, largely driven by agricultural expansion and land-use change, which have drastically reduced landscape connectivity, restricted movement, and compromised population viability [24,25,26].

The distribution of mammals is influenced by seasonal dynamics and habitat types, with each species occupying a range shaped by the interaction between current ecological conditions and its evolutionary history [27,28]. Although some species exhibit similar distributional patterns, these are rarely identical. At the local scale, home ranges, territories, and microhabitat use reflect individual-level distribution within accessible environments [29,30]. Medium- and large-sized mammals are particularly sensitive to habitat alterations, making them effective bioindicators of ecosystem integrity [31,32]. Ecosystems with greater structural complexity generally provide more niches and greater diversity of strategies for resource use, which, in turn, promotes greater mammalian diversity [33,34]. In semi-arid systems, the spatial and temporal distribution of mammals has a strong seasonal pattern. During the dry season, limited water and food availability restricts movement and activity, leading to a concentration of individuals in microhabitats that provide water sources or dense vegetation cover [35,36]. Conversely, during the rainy season, increased primary productivity expands the availability of food and refuge, facilitating wider ranging behavior [37]. Such seasonal shifts modify competition, predation, and reproductive patterns, ultimately shaping population dynamics and community structure. Understanding these ecological processes is essential for the development of effective conservation and management strategies in semi-arid regions, particularly under climate change scenarios that are altering seasonality and resource availability.

Monitoring mammal communities relies on complementary methods, including camera trapping and tracking. Camera traps enhance the detection of cryptic and nocturnal species, while also providing robust data on species richness, capture rates, and site occupancy [38,39,40]. Meanwhile, tracking techniques, based on the identification of footprints, feces, burrows, feeding remains, or other activity signs, provide indirect but reliable evidence of species presence and spatial distribution across large areas [41,42,43]. These approaches are non-invasive and cost-effective, making them particularly valuable in large or remote landscapes where extensive sampling is required. When combined, camera traps and track surveys provide complementary insights, strengthening assessments of mammalian diversity, distribution, and habitat use, thereby supporting more informed conservation planning.

In Coahuila, mammalian inventories have been less frequently documented than in other regions of Mexico [13,44,45]. This scarcity of information is particularly critical in semi-arid ecosystems, where anthropogenic pressure and habitat transformation can significantly affect the composition and structure of mammal communities. In contrast to tropical forests, where high mammal densities facilitate detection, arid and semi-arid ecosystems pose significant challenges due to sparse vegetation and low encounter rates. The complementary use of camera trapping and track surveys enhances species detectability and ecological inference, providing crucial insights for mammal conservation under increasing anthropogenic pressures [43,46,47]. In semi-arid ecosystems with a high degree of anthropization, effective mammal monitoring requires methods that maximize detection and minimize disturbance. The combination of indirect techniques, such as camera trapping and track surveying is essential for obtaining robust data on the presence, activity, and habitat use of medium- and large-sized species. In this context, it is essential to generate reference data that allows for the evaluation of species diversity, relative abundance, and occupancy patterns to design conservation and management strategies. Therefore, this study aimed to estimate the alpha diversity of medium- and large-sized mammals, evaluate the photographic rate and naïve occupancy of these species, and compare diversity, photographic rate, and naïve occupancy between the rainy and dry seasons in different vegetation types in an anthropized landscape in southeastern Coahuila, Mexico, to provide a baseline for understanding spatial and seasonal variation in mammal communities, which is critical for ecosystem monitoring and management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The state of Coahuila is located in northeastern Mexico, between 24°32′–29°53′ north latitude and 99°51′–103°58′ west longitude (Figure 1). It shares borders with the United States of America to the north, Zacatecas and San Luis Potosí to the south, Nuevo León to the east, and Chihuahua and Durango to the west. The state lies within the Chihuahuan Desert, an ecoregion that covers approximately 7.9% of the Mexican territory [48]. Its complex topography and wide altitudinal range (130–3470 m) create marked climatic heterogeneity supporting a mosaic of arid and semi-arid ecosystems [48]. Arid and semi-arid ecosystems in northern Mexico, particularly in southwestern Coahuila, are increasingly threatened by livestock overgrazing, habitat fragmentation, groundwater depletion, and land-use change driven by agriculture and energy development. These anthropogenic pressures alter vegetation structure, reduce habitat connectivity, and compromise mammal community integrity and ecosystem functioning [49,50].

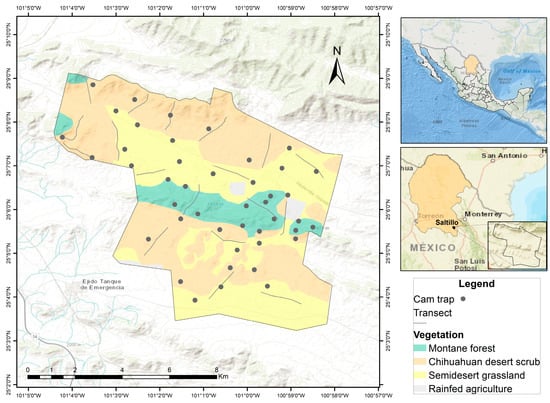

Figure 1.

Map showing the location of the study site in southeastern Coahuila, Mexico.

The study was conducted at the Los Ángeles Cattle Ranch (RGLA), a property of the Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro (UAAAN). The ranch encompasses ~7000 hectares and is primarily dedicated to extensive cattle ranching [24,51,52]. It is situated in the municipality of Saltillo, southeastern Coahuila (25°04′12″–25°08′51″ N, 100°58′07″–101°03′12″ W; Figure 1), at elevations ranging from 1600 to 2150 m. The regional climate is predominantly dry, with the most arid zones concentrated in the east, while sub-humid conditions occur in the Sierra de Arteaga and the north-central portion of the state [53]. Mean annual temperatures range from 18 to 22 °C, and average precipitation varies between 500 and 600 mm [51,53]. Vegetation cover at RGLA is dominated by Chihuahuan desert scrub and semi-desert grassland, which together occupy more than 70% of the surface. Larrea tridentata and Neltuma glandulosa, characterize the scrubland, while the grasslands are dominated by native grasses such as Bouteloua gracilis and B. curtipendula, interspersed with scattered shrubs. Additionally, patches of montane forest dominated by Pinus cembroides occur on some hillsides, reflecting the environmental heterogeneity of the area [54].

2.2. Field Work

The study was conducted between April 2023 and February 2024 using two complementary sampling methods: track surveys (using transect lines) and camera trapping. Transect surveys were implemented monthly to estimate species diversity and habitat associations of medium- and large-sized mammals. Transects were stratified by vegetation type and randomly allocated in proportion to the area of each habitat [55,56]. A total of 18 transect lines, each 1.5 km long and 0.2 km wide, were established at intervals of 1–2 km to minimize duplicate counts and systematically distributed at intervals of ~2 km across the study area. Along each transect, wherever evidence of mammal presence was recorded (e.g., tracks, droppings, burrows, and remains), it was documented photographically using a Canon® Rebel 3 camera (Canon® Inc.; Tokyo, Japan). The total sampling effort was calculated as the combined length of all transect walks. Surveys were conducted twice daily for three consecutive days each month, during both the dry season (October–May) and the rainy season (June–September), from 06:00 to 11:00 h and from 15:00 to 19:00 h, coinciding with periods of peak activity and visibility. Species identification was carried out using Aranda’s methodology [41], field guides, and local ecological knowledge. To reduce duplicate records, feeding and resting areas were monitored simultaneously, particularly in rugged terrain. The habitat type, season, and number of individuals were recorded for each sighting. Nine active camera traps were deployed for periods of 27–31 days and rotated across sites to maximize coverage of all vegetation types. Sampling stations were placed at 2 km intervals in locations with evidence of mammal activity (e.g., tracks, burrows, latrines) or along wildlife trails [57,58]. No attractants were used. Equipment included six Reconyx® Hyperfire Semi-Coverage IR HC500 units (Reconyx®; Holmen, WI, USA), two Wildgame® Innovations Terra Extremes, and one Bushnell® 24 MP Core camera (Wildgame® Innovations; Irving, TX, USA). Cameras were mounted 40–60 cm above the ground on Yucca (Yucca carnerosana) or pine (Pinus cembroides) trunks in scrub and forest habitats or on wooden posts in open grasslands. Each station was georeferenced using a Garmin® eTrex 10 unit (Garmin®; Siijhih City, Taiwan, China). Photographed mammals were identified based on the specialized literature [11,12,59].

2.3. Data Analysis

The data were compiled into a structured database and analyzed using R version 4.3.1 [60]. Mammalian diversity was evaluated through alpha diversity metrics calculated using the vegan package [61]. To compare diversity between the dry and rainy seasons, we generated rarefaction and extrapolation curves based on Hill numbers using the iNEXT package 3.0.2 [62,63,64,65]. These curves provide standardized estimates of species richness and allow robust comparisons of diversity across unequal sampling efforts [66]. Differences in Shannon diversity (H′) between seasons were evaluated using Hutcheson’s t-test, which statistically compares index values while accounting for their estimated variance [67,68]. The analysis was conducted in R [60] using the ecolTest package 0.0.1 [69]. H′ values corresponded to estimates obtained for each vegetation type—Chihuahuan Desert scrub, montane forest, and semi-desert grassland—during the rainy and dry seasons. A significance threshold of α = 0.05 was used to identify statistically significant differences.

Camera-trap photographs were processed and annotated using Digikam software 8.7.0 (available at https://apps.kde.org/es/digikam/ (accessed on 22 August 2025)). A photographic-event database was then constructed in R [60] with the camtrapR package 3.0.0 [70], which is specifically designed for camera-trapping data management [39]. Independent detection events were defined as consecutive records of the same species separated by at least 24 h or by the presence of different individuals within shorter intervals, thus avoiding pseudo replication [58,71,72,73]. Sampling effort was quantified as the total number of trap nights, calculated as the sum of days in which each camera was active and functioning properly [74]. To assess variation in the composition of terrestrial mammal assemblages recorded in both tracking and camera trapping, a multivariate ordination approach was applied using canonical correspondence analysis (CCA). The response matrix comprised species detection data, while explanatory variables included season (dry vs. rainy), vegetation type (Chihuahuan desert scrub, semi-desert grassland, montane forest), and sampling method (tracking vs. camera trapping). The significance of the model and the predictor variables was evaluated using permutation tests with 999 permutations [61], which allowed us to determine the statistical contribution of each environmental factor to the observed variation in community composition, ensuring a robust inference free of parametric assumptions. The analysis was performed using the vegan package 2.7-2 [61] in R [60], and graphical representations of ordination results were generated with the ggplot2 package 4.0.0 [75]. To assess species composition similarity among vegetation types and between seasons (rainy and dry), the Jaccard similarity index was calculated, based on the proportion of shared species between pairs of sites relative to the total number of species recorded in both. Analyses were conducted in R [60] using the vegan package [61]. The resulting similarity matrix was converted into long format using the reshape2 package 1.4.4 [76] to generate a heatmap visualization with ggplot2 [75]. For records obtained using camera traps, the photographic rate (or encounter rate) was used as a relative measure of abundance, and was calculated using the following expression:

This estimate relates the average number of detections to the sampling effort [77,78]. Any event of the same species separated by a minimum interval of 24 h was considered an independent record, to minimize pseudo replication and ensure that each detection represented a distinct biological event. The photographic rate of each species was estimated using the beta version of the RAIeR package [77,78]. Naïve occupancy (OccNaïve)—defined as the proportion of camera-trap stations where a species was recorded— was calculated as the proportion of stations where a species was recorded relative to the total number of active stations [79]. To evaluate the potential relationship of spatial distribution of species, we calculated correlations between naïve occupancy and photographic encounter rates [77,78].

Finally, each species was assigned a conservation status based on two criteria: (1) the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species [Critically Endangered (CR), Endangered (EN), Vulnerable (VU), Near Threatened (NT), Least Concern (LC), Data Deficient (DD), or Not Evaluated (NE)] [80], and (2) the legislation established in Mexican Official Standard (NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010) [81].

3. Results

3.1. Species Composition and Richness

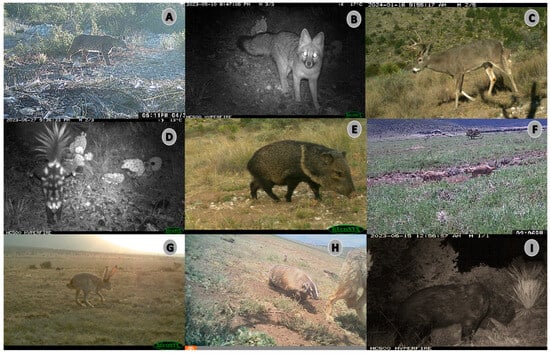

We recorded 16 mammal species, belonging to four orders and nine families (Table 1, Figure 2). The order Carnivora was the most diverse, comprising five families and eight species (Table 1). Track surveys, with a cumulative effort of 297 km, detected 14 species. Camera trapping resulted in 2799 trap nights and 571 independent photographic records, corresponding to 14 species (Figure 2). Regarding conservation status, one species, Cynomys mexicanus, is listed as Endangered by the IUCN Red List. Under Mexican law (NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010), Taxidea taxus is classified as Threatened, while Ursus americanus and C. mexicanus are classified as Endangered (Table 1).

Table 1.

Mammal species recorded using camera trapping and tracking at the Los Ángeles Cattle Ranch, Coahuila, Mexico. NOM-059 (NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010) [69]: E: Endangered; T: Threatened; IUCN [68]: LC: Least Concern; EN: Endangered.

Figure 2.

Some mammal species recorded using camera trapping at the Los Ángeles Cattle Ranch, Coahuila, Mexico: (A) Lynx rufus, (B) Urocyon cinereoargenteus, (C) Odocoileus virginianus, (D) Spilogale gracilis, (E) Dicotyles tajacu, (F) Cynomys mexicanus, (G) Lepus californicus, (H) Taxidea taxus and Canis latrans, (I) Ursus americanus.

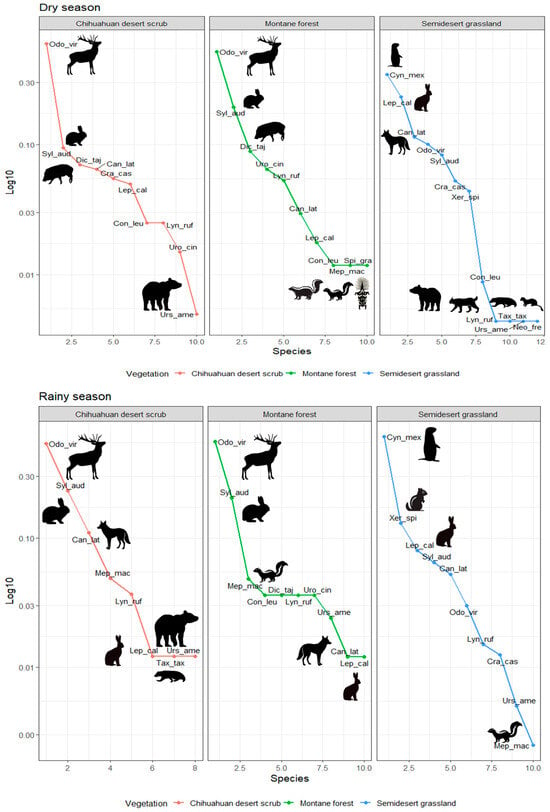

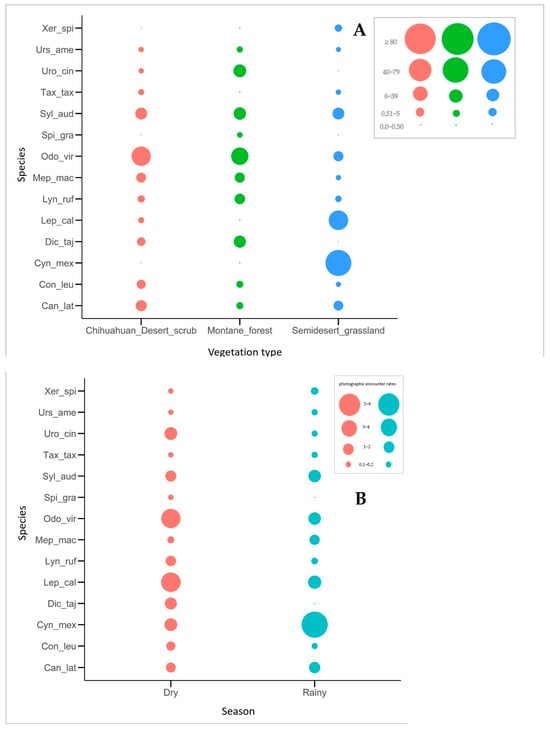

During the dry season, Odocoileus virginianus showed the highest relative abundance in the Chihuahuan desert scrub (0.59) and montane forest (0.51), followed by Sylvilagus audubonii (0.09–0.19). In the semi-desert grassland, C. mexicanus was dominant (0.34), together with Lepus californicus (0.23; Figure 3). During the rainy season, O. virginianus (0.53–0.55) and S. audubonii (0.20–0.23) maintained their predominance in scrub and forest, while C. mexicanus increased its abundance (0.60) in grasslands. In all habitats, carnivores had the lowest relative abundances (<0.012; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Rank abundance graphs of mammals recorded during the dry and rainy seasons in the study area. Odo_vir: Odocoileus virginianus; Syl_aud: Sylvilagus audubonii; Dic_taj: Dicotyles tajacu; Can_lat: Canis latrans; Uro_cin: Urocyon cinereoargenteus; Con_leu: Conepatus leuconotus; Mep_mac: Mephitis macroura; Spi_gra: Spilogale gracilis; Lyn_ruf: Lynx rufus; Urs_ame: Ursus americanus; Tax_tax: Taxidea taxus; Neo_fre: Neogale frenata; Lep_cal: Lepus californicus; Cyn_Mex: Cynomys mexicanus; Xer_spi: Xerospermophilus spilosoma; Cra_cas: Cratogeomys castanops.

Using the track surveys, we recorded a total of 604 terrestrial mammal signs, representing four orders, eight families, and 14 species. The order Rodentia was the most represented, with four species and 379 records, followed by Artiodactyla with two species and 111 records. The order Carnivora had the highest number of species (six) but the lowest number of records (43). The most abundant species was C. mexicanus (279 records), while Lynx rufus, Conepatus leuconotus, Neogale frenata, and U. americanus were the least abundant, with only one record each (Figure 3). Seasonal and habitat-specific patterns were also evident: C. mexicanus was particularly abundant in the semi-desert grassland during the rainy season (208 records), while L. rufus (montane forest, rainy season), C. leuconotus (Chihuahuan desert scrub, rainy season), N. frenata (semi-desert grassland, dry season), and U. americanus (semi-desert grassland, rainy season) were detected only once (in isolation).

In terms of species richness, 11 species were recorded in the montane forest, 12 in the Chihuahuan desert scrub, and 13 in the semi-desert grassland, yielding a mean species richness of 12 (Table 2). Diversity indices showed spatial and seasonal variation (Table 2); for example, during the rainy season, the montane forest, Chihuahuan desert scrub, and semi-desert grassland had Shannon diversity indices of 1.36, 1.43, and 1.37, and Simpson indices of 0.64, 0.63, and 0.60, respectively. Similarly, the semi-desert grassland showed the highest Simpson index (0.79), followed by the montane forest (0.73) and the Chihuahuan desert scrub (0.53) (Table 2). Hutcheson’s t-test revealed no significant differences in diversity between the wet and dry seasons (t = 0.18, df = 5.01, p = 0.86), suggesting that terrestrial mammal diversity remained relatively stable across seasons. No significant differences in Shannon diversity (H′) were observed among vegetation types (p > 0.05), indicating comparable levels of species diversity across habitats. The H′ values varied slightly between 1.52 and 1.61, with overlapping variances among communities, suggesting a relatively homogeneous distribution of species and evenness across the evaluated vegetation types.

Table 2.

Diversity indices recorded in the different types of vegetation during the dry and rainy seasons in the study area.

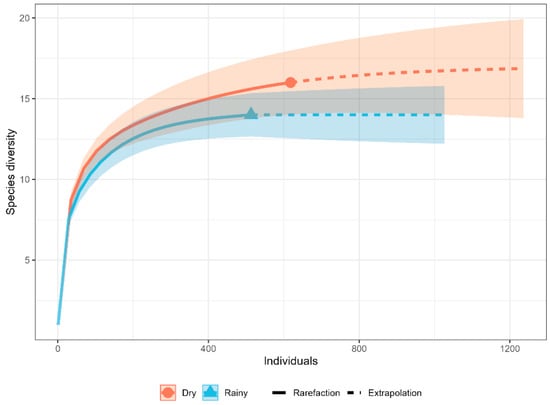

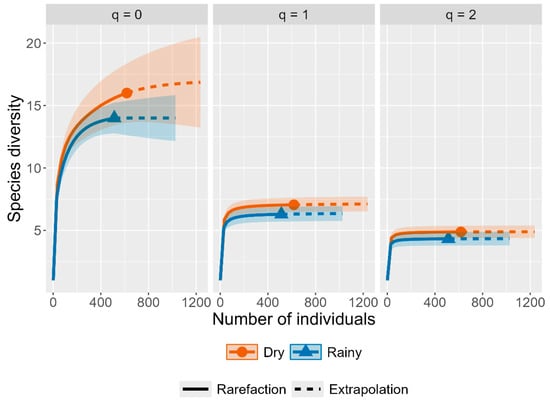

3.2. Species Rarefaction Curves

Rarefaction curves for both seasons tended to stabilize, suggesting sufficient sampling completeness. Although the rarefaction curve suggested higher species diversity in the dry season, the overlap of the 95% confidence intervals revealed no significant differences between seasons (Figure 4). Sample coverage curves also reached an asymptote, with values close to 99% for both seasons, confirming a high level of representativeness and that most species present were recorded. Hill numbers provided complementary insights into diversity patterns. The species richness (q0) was 16 species in the dry season and 14 in the rainy season. The highest values for q1 (Shannon) and q2 (inverse Simpson exponential) also occurred in the dry season, indicating greater diversity and greater evenness compared to the rainy season (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

Rarefaction curve of medium and large mammal species during the dry and rainy seasons in the study area.

Figure 5.

Species diversity curves according to Hill numbers (q = 0, richness; q = 1, Shannon exponential; and q = 2, the inverse Simpson).

3.3. Effects of Method, Season, and Habitat at Community Level

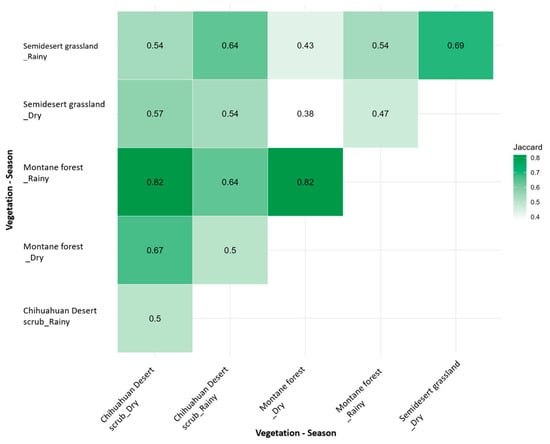

The heatmap shows a continuous color gradient representing Jaccard similarity values, where darker tones indicated higher similarity in species composition among vegetation types and seasons (Figure 6). The similarity values ranged from 0.38 to 0.82, indicating moderate to high variation across communities (Figure 6). The highest similarity (0.82) was recorded between the montane forest in the rainy season and the Chihuahuan desert scrub in the dry season, while the lowest (0.38) occurred between the semi-desert grassland and the montane forest, both in the dry season. Intermediate similarity values (0.54–0.57) were observed between the montane forest and the Chihuahuan desert scrub, denoting a moderate degree of species overlap across vegetation types and seasons (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Heatmap between medium and large mammal community composition and vegetation types during the dry and rainy seasons in the study area.

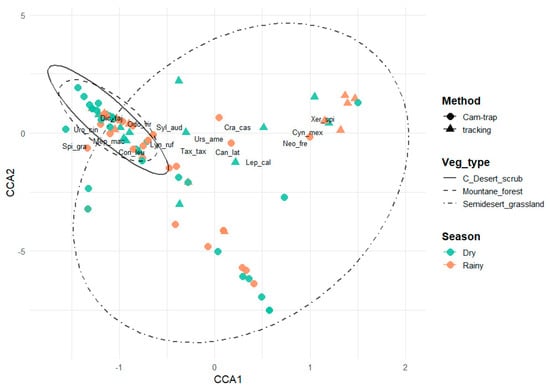

The canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) explained 21.7% of the total variation in mammal community composition. The first two canonical axes, CCA1 and CCA2, accounted for 16.1% and 2.9% of the total variation, respectively, summing to 19.0% (Figure 7). Permutation tests confirmed that the overall model was statistically significant (F4,94 = 6.51, p = 0.001), indicating a strong association between species abundance and the analyzed environmental gradients. Among the explanatory variables, vegetation type exerted the strongest and most significant influence on species distribution (F2,94 = 8.14, p = 0.001), followed by season (F1,94 = 5.60, p = 0.003) and sampling method (F1,94 = 4.15, p = 0.017). CCA showed that environmental variables explained 21.7% of the total variation in terrestrial mammal composition, demonstrating a structured community response to environmental gradients. The first two axes (CCA1 and CCA2) together explained 19.0% of the total variance and were significant (p < 0.05), indicating that environmental conditions determine the distribution and composition of species across sites. The CCA1 axis was primarily associated with the vegetation type gradient, distinguishing communities of the Chihuahuan desert scrub toward negative values, whereas semi-desert grasslands were distributed across both canonical axes, indicating broader variability (Figure 7). The CCA2 axis reflected seasonal variation in community composition. Montane forest assemblages exhibited a more compact clustering pattern, suggesting greater structural homogeneity, while semi-desert grassland communities showed a wider dispersion, consistent with higher compositional heterogeneity (Figure 7). Seasonality affected the spatial dispersion of the sampled sites, with greater heterogeneity during the rainy season, whereas the sampling method did not produce a clear separation among groups. In the CCA ordination plot (Figure 7), confidence ellipses differentiated by vegetation type illustrate distinct species–habitat associations, while the seasonal dispersion of points reflects temporal shifts in community composition. In the semi-desert grassland, species such as C. mexicanus, Xerospermophilus spilosoma, N. frenata, L. californicus, and Canis latrans exhibited a broad distribution across canonical axes, indicating ecological tolerance and plasticity in response to environmental variation.

Figure 7.

Canonical correspondence analysis (CCA) of the variation in medium and large mammal community composition during the dry and rainy seasons in the study area. Odo_vir: Odocoileus virginianus; Syl_aud: Sylvilagus audubonii; Dic_taj: Dicotyles tajacu; Can_lat: Canis latrans; Uro_cin: Urocyon cinereoargenteus; Con_leu: Conepatus leuconotus; Mep_mac: Mephitis macroura; Spi_gra: Spilogale gracilis; Lyn_ruf: Lynx rufus; Urs_ame: Ursus americanus; Tax_tax: Taxidea taxus; Neo_fre: Neogale frenata; Lep_cal: Lepus californicus; Cyn_Mex: Cynomys mexicanus; Xer_spi: Xerospermophilus spilosoma; Cra_cas: Cratogeomys castanops.

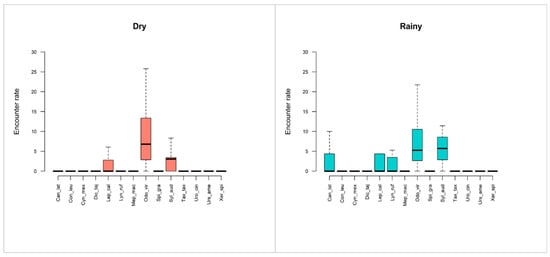

3.4. Photographic Rates

Photographic rates from camera trapping reflected similar patterns to track surveys. During the dry season, O. virginianus and S. audubonii exhibited the highest photographic rates (RAIeR = 4.10 ± 9.3). Lepus californicus showed an intermediate rate (4.0), while C. latrans, C. leuconotus, C. mexicanus, Dicotyles tajacu, L. rufus, Mephitis macroura, Spilogale gracilis, T. taxus, Urocyon cinereoargenteus, U. americanus, and X. spilosoma all presented low values (0.1 ± 1.3). In the rainy season, S. audubonii and O. virginianus again dominated (3 ± 10), while L. californicus, C. latrans, and L. rufus exhibited intermediate values (1 ± 4) with moderate dispersion. The remaining species showed consistently low photographic rates (0.1 ± 1.1) with reduced variability compared to the dry season (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Boxplots of the encounter rate of terrestrial mammal species recorded by camera trapping in the study area. Odo_vir: Odocoileus virginianus; Syl_aud: Sylvilagus audubonii; Dic_taj: Dicotyles tajacu; Can_lat: Canis latrans; Uro_cin: Urocyon cinereoargenteus; Con_leu: Conepatus leuconotus; Mep_mac: Mephitis macroura; Spi_gra: Spilogale gracilis; Lyn_ruf: Lynx rufus; Urs_ame: Ursus americanus; Tax_tax: Taxidea taxus; Neo_fre: Neogale frenata; Lep_cal: Lepus californicus; Cyn_Mex: Cynomys mexicanus; Xer_spi: Xerospermophilus spilosoma; Cra_cas: Cratogeomys castanops.

Photographic rates varied notably among vegetation types. In the montane forest, the highest photographic rates corresponded to O. virginianus (2.6 ± 44.8) and S. audubonii (2.6 ± 21.7), while S. gracilis and U. americanus also exhibited relatively elevated values (2.9 ± 3.4). In the Chihuahuan desert scrub, O. virginianus had the highest detection rate (2.7 ± 57.1). However, despite being represented by a single record, T. taxus reached the maximum photographic rates (RAIeR = 4.3). In the semi-desert grassland, C. mexicanus had the highest photographic rate (>90% of detections), whereas C. leuconotus had the lowest (2.9; Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Photographic rates of mammals recorded in the different types of vegetation (A) and in the dry and rainy seasons (B) in the study area. Odo_vir: Odocoileus virginianus; Syl_aud: Sylvilagus audubonii; Dic_taj: Dicotyles tajacu; Can_lat: Canis latrans; Uro_cin: Urocyon cinereoargenteus; Con_leu: Conepatus leuconotus; Mep_mac: Mephitis macroura; Spi_gra: Spilogale gracilis; Lyn_ruf: Lynx rufus; Urs_ame: Ursus americanus; Tax_tax: Taxidea taxus; Neo_fre: Neogale frenata; Lep_cal: Lepus californicus; Cyn_Mex: Cynomys mexicanus; Xer_spi: Xerospermophilus spilosoma; Cra_cas: Cratogeomys castanops.

During the dry season, O. virginianus was the most frequently recorded species, suggesting high activity during this period. In contrast, during the rainy season, C. mexicanus dominated detections, suggesting increased visibility and activity in grassland habitats. Other species with relatively high photographic rates in both seasons included S. audubonii, L. californicus, and U. cinereoargenteus (Figure 9).

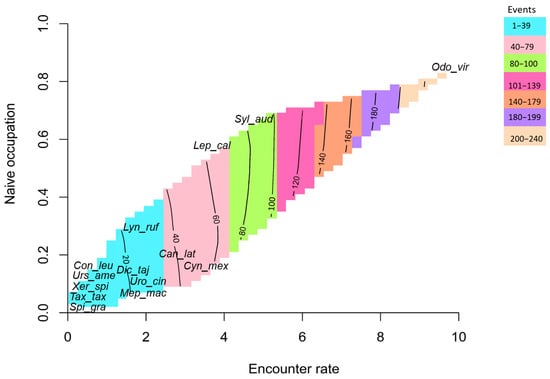

A significant and positive correlation was observed between the photographic rate (RAIeR) and naïve occupancy (OccNaïve, r2 = 0.92; p < 0.001), indicating a strong relationship between detection frequency and spatial occurrence across species (Figure 10). Among the recorded taxa, O. virginianus exhibited the highest detection metrics, with a photographic rate of 9.35, a naïve occupancy of 0.82, and 234 independent photographic events. Following this species, S. audubonii (RAIeR = 4.9; OccNaïve = 0.68; events = 88), L. californicus (RAIeR = 3.89; OccNaïve = 0.35; events = 67), C. latrans (RAIeR = 1.59; OccNaïve = 0.30; events = 48), and C. mexicanus (RAIeR = 2.95; OccNaïve = 0.10; events = 43) also displayed relatively high detection rates and broad spatial distributions within the study area. In contrast, several species clustered in the lower-left quadrant of the correlation plot, including D. tajacu, C. leuconotus, M. macroura, U. cinereoargenteus, U. americanus, X. spilosoma, T. taxus, and S. gracilis (Figure 10). These species exhibited fewer than 25 photographic events and low encounter rates (mean RAIeR = 0.1 ± 2.9), reflecting limited spatial occupancy and reduced detectability.

Figure 10.

Correlation between photographic rate and naive occupancy (OccNaive) for the mammal community in the study area. Odo_vir: Odocoileus virginianus; Syl_aud: Sylvilagus audubonii; Dic_taj: Dicotyles tajacu; Can_lat: Canis latrans; Uro_cin: Urocyon cinereoargenteus; Con_leu: Conepatus leuconotus; Mep_mac: Mephitis macroura; Spi_gra: Spilogale gracilis; Lyn_ruf: Lynx rufus; Urs_ame: Ursus americanus; Tax_tax: Taxidea taxus; Neo_fre: Neogale frenata; Lep_cal: Lepus californicus; Cyn_Mex: Cynomys mexicanus; Xer_spi: Xerospermophilus spilosoma; Cra_cas: Cratogeomys castanops.

4. Discussion

A total of 16 medium- and large-sized mammal species, belonging to four orders and nine families, were recorded through the combined use of track surveys and camera trapping, a complementary approach that enhances detection probability and provides a more comprehensive assessment of species richness and functional diversity [46,82]. This integrative methodology is particularly valuable in arid and semi-arid ecosystems, where low population densities, cryptic behavior, and harsh environmental conditions often hinder direct observations [43,83]. The integration of these complementary methodologies improved detection efficiency, as it facilitated the recording of species with cryptic behavior and low visual detectability while also capturing records of more abundant and wide-ranging taxa. This approach aligns with previous studies that highlight the importance of combining direct and indirect monitoring methods to generate robust and reliable estimates of mammal community structure [84,85]. Among the recorded species, C. mexicanus is listed as Endangered by the IUCN [80], T. taxus is classified as Threatened, and both U. americanus and C. mexicanus are considered Endangered under Mexican Official Standards [81]. The presence of protected and regionally threatened species highlights the importance of conservation in the study area, acting as a critical refuge that supports populations of taxa facing elevated extinction risk. This pattern is consistent with broader conservation trends across arid and semi-arid regions of Mexico and the Americas, where escalating anthropogenic pressures—particularly habitat loss, fragmentation, and climate variability—are eroding ecosystem integrity and driving a disproportionate increase in the number of threatened and endangered species [86].

Compared to other studies in arid and semi-arid ecosystems [87,88], the species richness observed here is moderate. Nevertheless, camera trapping has proven to be an essential tool in northern Mexico for documenting mammal richness, distribution, and activity patterns, particularly for species adapted to conditions of water scarcity and marked temperature fluctuations [89,90]. For instance, in the Janos Biosphere Reserve, the presence of Cynomys ludovicianus has been well documented. This species acts as an ecosystem engineer, enhancing habitat heterogeneity, promoting water infiltration, and providing shelter for a variety of taxa [49]. At the same time, the reintroduction of Bison bison into the same reserve has improved grassland health, strengthened ecosystem services, and contributed to the preservation of indigenous cultural values. In other portions of the Chihuahuan Desert, camera trapping has recorded more than 30 mammal species, including rodents (Dipodomys merriami), lagomorphs (L. californicus), and carnivores (Puma concolor), thus enriching the faunal inventory of this region [91].

Indirect evidence, including tracks, scat, and burrows, provides an important complement to camera-trapping data, particularly for elusive species with low detectability [38]. In anthropogenically transformed regions of northern Mexico, the integration of both methods has proven effective for identifying movement corridors, transit zones, and areas of conflict with human infrastructure [87,91]. However, there remains a notable gap in the Mexican literature, as few published studies have explicitly combined these approaches within a unified framework. On a broader scale, integrated monitoring has also shown considerable potential. For example, in hyper-arid regions of the Middle East, camera trapping documented 59 vertebrate species—including 12 IUCN-listed threatened species—and highlighted the dependence of desert fauna on scarce water sources. The study also evaluated reintroduction success by detecting offspring and predators of reintroduced populations, such as the desert gazelle (Gazella dorcas) [92]. Similarly, in Khaudum National Park, Namibia, camera trapping has been instrumental in identifying individuals of Panthera pardus, revealing habitat-use patterns and home-range sizes of large carnivores in arid ecosystems, with direct implications for their conservation [93]. Although track surveys and sign surveys remain methodologically useful in arid ecosystems, particularly for detecting species with low camera-trap detectability, the systematic integration of both approaches is still limited in the scientific literature. Strengthening this combined methodology will provide more comprehensive insights into mammal communities, particularly in regions facing intense anthropogenic pressures and climatic variability.

In tropical ecosystems, camera trapping has proven particularly effective for detecting complex community patterns. A standardized global survey in tropical forests, including sites in Costa Rica and Brazil, documented 105 mammal species and demonstrated how habitat fragmentation reduces both species richness and functional diversity [94]. Similarly, in cloud forests of the Sierra Madre Oriental, Hidalgo, camera placement along riparian and non-riparian areas enabled the estimation of relative abundance indices and activity patterns, revealing marked differences in habitat use [95]. These examples underscore that tropical ecosystems, although richer in species diversity, are also more sensitive to fragmentation: studies show that terrestrial mammal communities in fragmented tropical forest landscapes exhibit lower species richness, altered functional composition and elevated extinction risk [18,94]. In contrast to more mesic systems, semi-arid ecosystems in northern Mexico are characterized by lower overall species richness; nonetheless, camera-trap surveys have proven indispensable for detecting key mammalian taxa and elucidating spatial usage patterns across landscapes increasingly dominated by anthropogenic activity (e.g., detection of carnivores and prey in the Mapimí Biosphere Reserve, Chihuahuan Desert) [95,96,97]. Meanwhile, although less commonly applied in arid settings, indirect track- or footprint-based surveys hold considerable potential for documenting elusive or visually inconspicuous taxa, identifying movement corridors and critical human–wildlife crossing zones (methods reviewed in sign-based surveys of desert mammals) [96,97]. Despite these methodological advantages, integrative studies combining camera trapping with track surveys in arid and semi-arid northern Mexican landscapes remain scarce.

In the present study area, the mammal assemblage recorded during both wet and dry seasons reflected moderate richness and was dominated by generalist herbivores (O. virginianus, S. audubonii and C. mexicanus) and a key colonial rodent of arid zones as C. mexicanus. Greater diversity and evenness were observed in the dry season, particularly in semi-desert grassland. The overlap in the 95% confidence intervals of the seasonal rarefaction curves, both reaching asymptotes, indicates that sampling effort was sufficient to capture most of the species present in each season. Ecologically, this suggests comparable community richness and a stable assemblage structure across seasons, reflecting limited temporal turnover in species composition. This result suggests that seasonal differences were not significant. This pattern is consistent with arid ecosystems, where reduced vegetation cover and water availability increase animal movements toward predictable resources, enhancing detectability. Comparable results from the Chihuahuan and Sonoran deserts indicate that colonial rodents and lagomorphs drive relative abundance, while carnivores occur at low densities and with highly localized detections. This aligns with the low occupancy rates of mustelids, skunks, and ursids observed in this study. In contrast, tropical ecosystems typically exhibit higher local richness, a greater representation of medium- to large-sized carnivores and frugivores, and more complex trophic structures, where dominance rarely depends on a few diurnal herbivores [94,98]. Moreover, tropical systems often show seasonal peaks in detectability linked to fruiting or dry-season resource concentration, but higher baseline productivity buffers these fluctuations and sustains high diversity year-round. At a global scale, tropical forests are generally characterized by higher Shannon diversity values and greater evenness, whereas deserts and arid shrublands exhibit lower alpha diversity and assemblages that are strongly shaped by primary productivity and climatic variability [99]. The results presented here—species richness of ≈12 and pronounced dominance of O. virginianus and S. audubonii—are consistent with expectations for arid systems, where community structure is tightly constrained by environmental unpredictability.

Rarefaction stabilization and ≈99% sample coverage indicates near-complete inventory. This is comparable to well-designed tropical surveys, though dense forests typically require greater effort to reach asymptotes due to microenvironmental heterogeneity. The strong correlation between RAIeR and naïve occupancy (r2 = 0.92) suggests that photographic rates effectively captured spatial availability, a common pattern in open landscapes with low vegetation cover. In contrast, in closed tropical forests, the relationship is often weakened by microhabitat complexity, trail-use biases, and species-specific detectability. From a conservation perspective, the co-occurrence of at-risk species (i.e., C. mexicanus, U. americanus, T. taxus, under national legislation) underscores the ecological relevance of arid mosaics with heterogeneous productivity and grassland patches. At a global scale, grassland and desert specialists face steep declines driven by fragmentation, overgrazing, and climate change, while in the humid tropics, deforestation and hunting remain predominant threats [100,101]. The dominance of C. mexicanus in semi-desert grassland and its marked seasonal signal are consistent with studies in arid grasslands that document ecological engineering effects and colonial aggregation. In tropical forests, community structuring is also mediated by engineering species (e.g., peccaries), but dominance tends to be distributed across multiple guilds. Collectively, the observed patterns conform with theoretical and empirical expectations for arid systems, which differ from tropical ones in richness, evenness, detectability, and seasonality [99].

The high similarity (0.82) recorded between the mammal community of the montane forest during the rainy season and that of the Chihuahuan desert scrub during the dry season suggests a relatively homogeneous composition between structurally contrasting habitats. This pattern indicates the presence of generalist species, or species with broad ecological plasticity, capable of exploiting resources in different environments and under varying seasonal conditions. Similar results have been reported by Derebe et al. [102], who attribute this affinity to the spatial continuity of the landscape and the existence of natural corridors that facilitate species movement. The desert scrub, characterized by its structural heterogeneity and the temporal availability of resources, favors the coexistence of species with different ecological strategies and contributes to the functional connectivity of the landscape [103]. These conditions could explain its role as a transitional habitat between arid and temperate ecosystems. In contrast, the low similarity between the semi-desert grassland and montane forest communities during the dry season demonstrates a marked differentiation in species composition, likely associated with variations in vegetation structure, ground cover, and refuge availability. Coincidentally, changes in terrestrial mammal composition have been documented to depend more on habitat type than on climatic seasonality [104,105]. Taken together, these results underscore the role of landscape heterogeneity and habitat structure in the spatial organization of mammal communities.

In climates with strong seasonal gradients, the strategic placement of cameras near water sources has proven highly effective for detecting carnivores, and global aridland studies have confirmed that proximity to water increases both species’ detectability and recorded richness [106]. Nationally, in more humid regions, camera traps have shown connectivity along riparian corridors in Sonora, where jaguars, black bears, and ocelots use river systems as transit routes, highlighting the importance of conservation of rivers in fragmented landscapes [87]. In the Sierra Nanchititla, studies revealed that ~67% of species are nocturnal, with diurnal and crepuscular activity varying seasonally and by sex or resource availability [107]. These findings demonstrate the utility of camera trapping for assessing temporal patterns and connectivity in both natural and anthropized ecosystems. A key methodological challenge in arid and semi-arid systems is the bias introduced by camera placement. In such areas, cameras positioned on animal trails often inflate detection probabilities for some species while underrepresenting others, potentially leading to biased interpretations. Consequently, mixed sampling designs—combining trail-based placements with off-trail or interior habitats—are recommended to reduce spatial bias.

Overall, evidence indicates that camera trapping provides robust, non-invasive data on faunal composition, richness, and activity in arid and semi-arid systems, while indirect tracking remains a valuable complement for detecting elusive or highly mobile taxa. However, integrative methodological approaches remain underdeveloped in northern Mexico. Strategic camera placement, especially near water sources or anthropogenic access structures, significantly increases sampling efficiency in fragmented landscapes. When combined, camera trapping and track surveys enhance the capacity to characterize habitat use, connectivity, and anthropogenic pressures on mammal populations [38,108]. Advancing integrative approaches in northern Mexico’s semi-arid landscapes—where agriculture, livestock, and infrastructure intensify human pressure—is therefore essential for designing conservation and adaptive management strategies. Such efforts will improve understanding of medium- and large-sized mammal dynamics in anthropized arid environments, strengthening the scientific basis for informed policy and effective conservation action.

Our findings emphasize the importance of studying overlooked and unique ecosystems such as semi-arid and arid ecosystems, even within fragmented and human-dominated landscapes. The mammal communities documented in our study are likely to have been isolated for decades from larger, contiguous tracts of natural vegetation, making them both vulnerable and valuable as reservoirs of genetic diversity. Small and isolated populations of medium- and large-sized mammals are disproportionately affected by human-induced mortality, which substantially increases their probability of local extinction [109,110].

5. Conclusions

This study provides baseline information on the composition and abundance of medium- and large-sized terrestrial mammals in southeastern Coahuila, Mexico. The results align with expected patterns for arid ecosystems: dominance of colonial herbivores and rodents, moderate diversity, higher evenness during the dry season, elevated detectability, and efficient sampling. In contrast, tropical ecosystems in Mexico typically exhibit greater species richness, more complex trophic structures, and variable detectability. These contrasts reflect global ecological patterns and reinforce the need for biome-specific conservation strategies.

Our contribution expands current knowledge of mammalian diversity and habitat associations in semi-arid anthropogenic landscapes. Importantly, the integration of complementary approaches—including camera trapping, track surveys, biological collections, and community participation—facilitates a more comprehensive understanding of species distributions, population dynamics, and anthropogenic impacts. Consequently, conservation planning should prioritize the maintenance of native ecosystems—such as mountain forests, Chihuahuan desert scrub, and semi-desert grasslands—while reducing proximity to human infrastructure. Our results are essential for informing adaptive and sustainable conservation strategies in semi-arid regions under increasing human pressure and climate change. Protecting and managing remnant natural habitats, while mitigating infrastructure impacts, will be critical to ensuring the long-term persistence of medium- and large-sized mammals in northern Mexico.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.J.C.-B. and J.A.E.-D.; methodology, E.J.C.-B.; software, E.J.C.-B.; validation, E.J.C.-B., J.A.E.-D. and J.E.R.-A.; formal analysis, E.J.C.-B., J.A.E.-D. and J.E.R.-A.; investigation, E.J.C.-B.; resources, E.J.C.-B. and J.A.E.-D.; data curation, E.J.C.-B. and E.G.C.-L.; writing—original draft preparation, E.J.C.-B. and J.E.R.-A.; writing—review and editing, E.J.C.-B., J.A.E.-D., J.E.R.-A., J.A.H.-H. and E.G.C.-L.; visualization, E.J.C.-B.; supervision, J.A.E.-D. and J.E.R.-A.; project administration, E.J.C.-B. and J.A.E.-D.; funding acquisition, E.J.C.-B. and J.A.E.-D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Institutional Research Funds for projects 25311-425202001-2391, 38111-425104001-2178, and 38111-425104001-2389 of the Antonio Narro Agrarian Autonomous University and to the postgraduate scholarships (835404, 832842) from the SECIHTI.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Ricardo Vásquez Aldape, Pedro Carrillo López, and all the staff in charge of the Los Ángeles Cattle Ranch for the logistical support and the facilities provided.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Challenger, A. Utilización y Conservación de los Ecosistemas de México: Pasado, Presente y Futuro; Instituto de Biología, UNAM, Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad: Mexico City, Mexico, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jurado-Guerra, P.; Velázquez-Martínez, M.; Sánchez-Gutiérrez, R.A.; Álvarez-Holguín, A.; Domínguez-Martínez, P.A.; Gutiérrez-Luna, R.; Chávez-Ruiz, M.G. Los pastizales y matorrales de zonas áridas y semiáridas de México: Estatus actual, retos y perspectivas. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Pecu. 2021, 12, 261–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewart, H.E.; Pasqualotto, N.; Paolino, R.M.; Jensen, K.; Chiarello, A.G. Effect of anthropogenic disturbance and land cover protection on the behavioral patterns and abundance of Brazilian mammals. Global Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 50, e02839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzun, G.; Evcin, Ö. Determination of Dispersal Corridors Used by Large Mammals Between Close Habitats. Diversity 2025, 17, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiang, D.C.F.; Morris, A.; Bell, M.; Gibbins, C.N.; Azhar, B.; Lechner, A.M. Ecological connectivity in fragmented agricultural landscapes and the importance of scattered trees and small patches. Ecol. Process. 2021, 10, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Wang, L.-J.; Jiang, J.; Zhao, Y.-G. Direct and indirect effects of agricultural expansion and landscape fragmentation processes on natural habitats. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 353, 108555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheptou, P.O.; Hargreaves, A.L.; Bonte, D.; Jacquemyn, H. Adaptation to fragmentation: Evolutionary dynamics driven by human influences. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2017, 372, 20160037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cromsigt, J.P.G.M.; Kuijper, D.P.J.; Adam, M.; Beschta, R.L.; Churski, M.; Eycott, A.; Kerley, G.I.H.; Mysterud, A.; Schmidt, K.; West, K. Hunting for fear: Innovating management of human-wildlife conflicts. J. Appl. Ecol. 2013, 50, 544–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Flores, J.; Mardero, S.; López-Cen, A.; Contreras-Moreno, F.M. Human-wildlife conflicts and drought in the greater Calakmul Region, Mexico: Implications for tapir conservation. Neotrop. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 16, 539–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessen, D.O. Biotic Deterioration and Homogenization: Why It Matters. Int. J. Polit. Cult. Soc. 2024. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10767-024-09498-x#citeas (accessed on 22 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ceballos, G.; Oliva, G. Los Mamíferos Silvestres de México; Conabio-Fondo de Cultura Económica: Mexico City, Mexico, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos, G. Mammals of Mexico; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Pulido, J.; González-Ruíz, N.; Contreras-Balderas, A.J. Mamíferos. In La Biodiversidad en Coahuila. Estudio de Estado; Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, Gobierno del Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza: Mexico City, Mexico, 2018; Volume 2, pp. 411–418. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Rodríguez, E.; Escalera-Vázquez, L.; Calderón-Patrón, J.M.; Mendoza, E. Mamíferos medianos y grandes en sitios de tala de impacto reducido y de conservación en la sierra Juárez, Oaxaca. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2019, 90, e902776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milligan, M.C.; McNew, L.B. Evaluating the cumulative effects of livestock grazing on wildlife with an integrated population model. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 818050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezcurra, E. Los corredores biológicos desde las ciencias ambientales. In Conectividad para la Conservación de la Biodiversidad en México: Estado Actual, Retos y Perspectivas; Bezaury-Creel, J.E., Ed.; Agencia Francesa de Desarrollo: Mexico City, Mexico, 2024; pp. 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- León-Paniagua, L.; García-Trejo, E.; Arroyo-Cabrales, J.; Castañeda-Rico, S. Patrones biogeográficos de la mastofauna. In Biodiversidad de la Sierra Madre Oriental; Luna, I., Morrone, J.J., Espinosa, D., Eds.; Las Prensas de Ciencias: Mexico City, Mexico, 2004; pp. 469–486. [Google Scholar]

- Crooks, K.R.; Burdett, C.L.; Theobald, S.R.B.; Di Marco, M.; Rondinini, M.; Rondinini, C.; Boitani, L. Quantification of hábitat fragmentation reveals extinction risk in terrestrial mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 7635–7640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfau, R.S.; Kozora, A.N.; Gatica-Colima, A.B.; Sudman, P.S. Population genetic structure of a Chihuahuan Desert endemic mammal, the desert pocket gopher, Geomys arenarius. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, e10576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbuena-Serrano, Á.; Zarco-González, M.M.; Carreón-Arroyo, G.; Carrera-Treviño, R.; Amador-Alcalá, S.; Monroy-Vilchis, O. Connectivity of priority areas for the conservation of large carnivores in northern Mexico. J. Nat. Conserv. 2022, 65, 126116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarco-González, Z.; Carrera-Treviño, R.; Monroy-Vilchis, O. Conservation of black bear (Ursus americanus) in Mexico through GPS tracking: Crossing and roadkill sites. Wildl. Res. 2023, 51, WR22121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Morales, G.; Hernández-Gómez, J.E.; García-Moreno, J.; León-Paniagua, L. Peripatric speciation of an endemic species driven by Pleistocene climate change: The case of the Mexican prairie dog (Cynomys mexicanus). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2016, 94, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, A.; Cerna, E.; Ceballos, G.; Ochoa, Y.M. Detección y cuantificación de plaguicidas en heces de Cynomys mexicanus en colonias de dos estados del norte de México. Act. Univ. 2023, 33, e3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Bazan, E.J.; Encina-Domínguez, J.A.; Ramírez-Albores, J.E.; Chávez-Lugo, E.G. Rodents in xerophilous shrubland and semi-desert grassland communities of southeastern Coahuila, Mexico. Agro Product. 2024, 17, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-García, F.; Escobar-Flores, J.G.; Vázquez-López, P.A. Potential distribution models for predicting human-Black bear (Ursus americanus var. eremicus) interactions in the Sierra de Zapalinamé Natural Reserve, Saltillo, Coahuila. Agro Product. 2024, 17, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wilson, M.; Hu, G.; Liu, J.; Wu, J.; Yu, M. How does habitat fragmentation affect the biodiversity and ecosystem functioning relationship? Landsc. Ecol. 2018, 33, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.E.; Safi, K. Ecology and evolution of mammalian biodiversity. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2011, 366, 2451–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udy, K.; Fritsch, M.; Meyer, K.M.; Grass, I.; Hanß, S.; Hartig, F.; Kneib, T.; Kreft, H.; Kukunda, C.B.; Péer, G.; et al. Environmental heterogeneity predicts global species richness patterns better than area. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2021, 30, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bene, J.K.; Bitty, E.A.; Bohoussou, K.H.; Abedi, M.; Gamys, J.; Soribah, P.A.J. Current conservation status of large mammals in Sime Darby oil palm concession in Liberia. Glob. J. Biol. Agric. Health Sci. 2013, 2, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- García-Feria, L.M.; Pérez-Solano, L.A.; Gallina-Tessaro, S.; Peña-Peniche, A. Microhabitat characterization in the home range of the Mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) in arid zones. Therya 2025, 15, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabira, G.; Tsegaye, G.; Tadesse, H. The diversity, abundance and habitat association of medium and large-sized mammals of Dati Wolel National Park, Western Ethiopia. Int. J. Biodivers. Conserv. 2015, 7, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tefera, G.G.; Tessema, T.H.; Bekere, T.A.; Gutema, T.M. The diversity and habitat association of medium and large mammals in the Dhidhessa Wildlife Sanctuary, Southwestern Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0317441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, R.S.; Johnston, E.L.; Clark, G.F. The role of habitat complexity in community development is mediated by resource availability. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, V.L.; Boyé, A.; Le Garrec, V.; Maguer, M.; Tauran, A.; Gauthier, O.; Grall, J. Habitat complexity promotes species richness and community stability: A case study in a marine biogenic habitat. Oikos 2025, 2025, e10675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fynn, R.W.S.; Chase, M.; Röder, A. Functional habitat heterogeneity and large herbivore seasonal habitat selection in northern Botswana. S. Afr. J. Wildl. Res. 2014, 44, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demosthenous-Bonastre, E.; Grau-Andrés, R.; Batlle-Benaiges, J.; Corbera, J.; Preece, C.; Torner, G.; Viza, A.; Fernández-Martínez, M. Water sources shape drought effects on mammal activity in mediterranean woodlands. Mamm. Biol. 2025. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42991-025-00507-w (accessed on 22 August 2025). [CrossRef]

- Tucker, M.A.; Santini, L.; Carbone, C.; Mueller, T. Mammals population densities at a global scale are higher in human-modified areas. Ecography 2021, 44, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyra-Jorge, M.C.; Ciocheti, G.; Pivello, V.R.; Meirelles, S.T. Comparing methods for sampling large- and medium-sized mammals: Camera traps and track plots. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2008, 54, 739–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Tello, E.; Mandujano, S. Paquete camtrapR para gestionar datos de foto-trampeo: Aplicación en la Reserva de la Biosfera Tehuacán-Cuicatlán. Rev. Mex. Mastozool. 2017, 7, 13–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mandujano, S. Índice de abundancia relativa y tasa de encuentro con trampas cámara. Mammal. Notes 2024, 10, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aranda, M. Manual para el Rastreo de Mamíferos Silvestres de México; Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad: Mexico City, Mexico, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chávez, C.; De La Torre, A.; Bárcenas, H.; Medellín, R.A.; Zarza, H.; Ceballos, G. Manual de Fototrampeo para Estudio de Fauna Silvestre. el Jaguar en México Como Estudio de Caso; Alianza WWF-Telcel, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Tangil, B.D.; Rodríguez, A. Uniform performance of mammal detection methods under contrasting environmental conditions in Mediterranean landscapes. Ecosphere 2021, 12, e03349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa-Martínez, D.V.; Ríos-Muñoz, C.A.; González-Ruíz, N.; Ramírez-Pulido, J.; León-Paniagua, L.; Arroyo-Cabrales, J. Mamíferos de Coahuila. Rev. Mex. Mastozool. 2016, 6, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Pulido, J. Panorama del conocimiento de los mamíferos de México: Con énfasis a nivel estatal. In Riqueza y Conservación de los Mamíferos en México a Nivel Estatal; Sosa-Escalante, J.E., Sánchez-Rojas, G., Briones-Salas, M., Hortelano-Moncada, Y., Magaña-Cota, G., Eds.; Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Asociación Mexicana de Mastozoología A.C., Universidad de Guanajuato: Mexico City, Mexico, 2016; pp. 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Burton, A.C.; Neilson, E.; Moreira, D.; Ladle, A.; Steenweg, R.; Fisher, J.T.; Bayne, E.; Boutin, S. Wildlife camera trapping: A review and recommendations for linking surveys to ecological processes. J. Appl. Ecol. 2015, 52, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trofino-Falasco, C.; Simoy, M.V.; Aranguren, M.F.; Pizzarello, M.G.; Cortelezzi, A.; Vera, D.G.; Simoy, M.I.; Marinelli, C.B.; Cepeda, R.E.; Di Giacomo, A.S.; et al. How effective is camera trapping in monitoring grassland species in the southern Pampas ecoregion? Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2023, 94, e945243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Aldaco, S.X. Análisis espacial y temporal de la cobertura forestal. In La Biodiversidad en Coahuila. Estudio de Estado; Conabio, Gobierno del Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza, Comps.: Mexico City, Mexico, 2017; Volume 1, pp. 113–122. [Google Scholar]

- Ceballos, G.; Davidson, A.; List, R.; Pacheco, J.; Manzano-Fisher, P.; Santo-Barrera, G.; Cruzado, J. Rapid decline of a grassland system and its ecological and conservation implications. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e8562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, E.; Guevara, R.; Dirzo, R. Impacts of land use and cover change on land mammal distribution ranges across Mexican ecosystems. In Mexican Fauna in the Anthropocene; Jones, R.W., Ornelas-García, C.P., Pineda-López, R., Álvarez, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Santos, A.; Zermeño-González, A.; Cadena-Zapata, M.; Gil-Marín, J.A.; Cornejo-Oviedo, E.; Ríos-Camey, M.S. Impacto de la labranza en el flujo energético de un suelo arcilloso. Terra Latinoam. 2018, 26, 203–213. [Google Scholar]

- Heredia-Pineda, F.J.; Lozano-Cavazos, E.A.; Romero-Figueroa, G.; Alanís-Rodríguez, E.; Tarango-Arámbula, L.A.; Ugalde-Lezama, S. Relaciones interespecíficas de alimentación del gorrión de Worthen (Spizella wortheni) durante la época no reproductiva en Coahuila, México. Rev. Chapingo Ser. Zonas Áridas 2017, 16, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza-Hernández, J.M.; González-Aldaco, S.X. Clima. In La Biodiversidad en Coahuila. Estudio de Estado; Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, Gobierno del Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza, Comps.: Mexico City, Mexico, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Encina-Domínguez, J.A.; Valdés, J.; Villarreal, J.A. Tipos de vegetación y comunidades vegetales. In La Biodiversidad en Coahuila. Estudio de Estado; Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, Gobierno del Estado de Coahuila de Zaragoza: Mexico City, Mexico, 2018; Volume 2, pp. 89–110. [Google Scholar]

- Stachowicz, I.; Ferrer, J.R.; Quiroga-Carmona, M.; Moran, L.; Lozano, C. Baseline for monitoring and habitat use of medium to large non-volant mammals in Gran Sabana, Venezuela. Therya 2020, 11, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babyesiza, S.W.; Mgode, G.; Mpagi, J.L.; Sabuni, C.; Ssuuna, J.; Akoth, S.; Katak-Webwa, A. Composition in non-volant small mammals inhabiting a degradation gradient in a lowland tropical forest in Uganda. Wildl. Biol. 2023, 2023, e01135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karanth, K.U.; Nichols, J.D. Estimation of tiger densities in India using photographic captures and recaptures. Ecology 1998, 79, 2852–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffei, L.; Cuellar, E.; Noss, J. Uso de trampas cámara para la evaluación de mamíferos en el ecotono Chaco-Chiquitanía. Rev. Bol. Ecol. Conserv. Amb. 2002, 11, 55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez-Castañeda, S.T.; Álvarez, T.; González-Ruiz, N. Guía para la Identificación de los Mamíferos de México en Campo y Laboratorio; Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste, S.C., Instituto Politécnico Nacional 195: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023; Available online: https://www.r-project.org/ (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.; Weedon, J. Vegan Community Ecology Package Version 2.6, The Comprehensive R Archive Network. 2022. Available online: http://cran.r-project.org (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Hill, A.M.O. Diversity and evenness: A unifying notation and its consequences. Ecology 1973, 54, 427–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C.E. Métodos para Medir la Biodiversidad; MyT-Manuales y Tesis SEA: Zaragoza, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, T.C.; Ma, K.H.; Chao, A. iNEXT: An R package for interpolation and extrapolation of species diversity (Hill numbers). Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 1451–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, A.; Kubota, Y.; Zelený, D.; Chiu, C.H.; Li, C.F.; Kusumoto, B.; Colwell, R.K. Quantifying sample completeness and comparing diversities among assemblages. Ecol. Res. 2020, 35, 292–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Hernández, J.C. Inter/extrapolación de la diversidad: iNEXT. In Fototrampeo en R: Organización y Análisis de Datos; Mandujano, S., Pérez-Solano, L.A., Eds.; Instituto de Ecología A. C.: Xalapa, Mexico, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hutcheson, K. A test for comparing diversities based on the Shannon formula. J. Theor. Biol. 1970, 29, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magurran, A.E. Measuring Biological Diversity; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Delgado, D. ecolTest: Community Ecology Tests. R Package Version 1.0.2. 2021. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=ecolTest (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Niedballa, J.; Sollmann, R.; Courtiol, A.; Wilting, A. camtrapR: An R package for efficient camera trap data management. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 1457–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira-Torres, I.; Briones-Salas, M.; Sánchez-Rojas, G. Abundancia relativa, estructura poblacional, preferencia de hábitat y patrones de actividad del tapir centroamericano Tapirus bairdii (Perissodactyla: Tapiridae), en la Selva de Los Chimalapas, Oaxaca, México. Rev. Biol. Trop. 2014, 62, 1407–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Pérez, E.; Reyna-Hurtado, R.; Castillo-Vela, G.; Sanvicente-López, M.; Moreira-Ramírez, J.F. Fototrampeo de mamíferos terrestres de talla mediana y grande asociados a petenes del noroeste de la península de Yucatán, México. Therya 2015, 6, 559–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Werschitz, A.; Mandujano, S.; Passamani, M. Influence of forest type on the diversity, abundance, and naïve occupancy of the mammal assemblage in the southeastern Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Therya 2023, 14, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Espinoza, J.M.; Soria-Díaz, L.; Astudillo-Sánchez, C.C.; Treviño-Carreón, J.; Barriga-Vallejo, C.; Maldonado-Camacho, E. Diversidad y abundancia de mamíferos del bosque mesófilo de montaña del noreste de México. Act. Zool. Mex. 2023, 39, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H. Remodelación de datos con el paquete reshape2. J. Stat. Soft. 2007, 21, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandujano, S. Beta Version of the RAI_eR Package, GitHub Repository. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/SMandujanoR (accessed on 22 August 2025).

- Mandujano, S.; Pérez-Solano, L.A. Fototrampeo en R: Organización y Análisis de Datos; Instituto de Ecología A. C.: Xalapa, Mexico, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kéry, M.; Royle, J.A. Applied Hierarchical Modeling in Ecology: Analysis of Distribution, Abundance and Species Richness in R and BUGS; Academic Press: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). Red List of Threatened Species-International Union for Conservation of Nature. 2024. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/ (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT). Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010, Protección Ambiental-Especies Nativas de México de Flora y Fauna Silvestres-Categorías de Riesgo y Especificaciones para su Inclusión, Exclusión o Cambio-Lista de Especies en Riesgo. Diario Oficial de la Federación. 2010. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/profepa/documentos/norma-oficial-mexicana-nom-059-semarnat-2010 (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Steenweg, R.; Hebblewhite, M.; Whittington, J.; Lukacs, P.; McKelvey, K. Sampling scales define occupancy and underlying occupancy-abundance relationships in animals. Ecology 2018, 99, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogues, E.; Arends, A.; von Keyserlingk, M.A.G. Rapid systematic literature review: Camera trap sampling in ecological studies: Consideration of wildlife welfare. Anim. Welf. 2025, 34, e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Irineo, G.; Santos-Moreno, A. Diversidad de una comunidad de mamíferos carnívoros en una selva mediana del noreste de Oaxaca, México. Act. Zool. Mex. 2010, 26, 721–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, I.; Salvatori, M.; Buonafede, E.; Pistolesi, A.; Corradini, A.; Cappai, N.; Marconi, M.; Seidenari, L.; Cagnacci, F.; Rovero, F. Placement matters: Implications of trail-versus random-based camera-trap deployment for monitoring mammal communities. Ecol. Appl. 2025, 35, e70083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Cordero, V.; Botello, F.; Flores-Martínez, J.J.; Gómez-Rodríguez, R.A.; Guevara, L.; Gutiérrez-Granados, G. Biodiversidad de Chordata (Mammalia) en México. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2014, 85, S496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragan, K.; Schipper, J.; Bateman, H.L.; Hall, S.J. Mammal use of riparian corridors in semi-arid Sonora, Mexico. J. Wildl. Manag. 2023, 87, e22322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo-Sanabria, A.A.; Fernández, J.A.; Hernández-Quiroz, N.S.; Buitrago-Torres, D.L.; Álvarez-Córdova, F. Ecological interactions of terrestrial mammals in the Chihuahuan Desert: A systematic map. Mammal Rev. 2025, 55, e70001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, J. Changing use of camera traps in mammalian field research: Habitats, taxa and study types. Mammal Rev. 2013, 43, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halle, S. Ecological Relevance of Daily Activity Patterns. In Activity Patterns in Small Mammals; Halle, S., Stenseth, N.C., Eds.; Ecological Studies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; Volume 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizalde-Arellano, C.; López-Vidal, J.C.; Hernández, L.; Laundré, J.W.; Cervantes, F.A.; Morales-Mejía, F.M.; Ramírez-Vargas, M.; Dávila-Galaviz, L.F.; González-Romero, A.; Alonso-Spilsbury, M. Registro de presencia y actividades de algunos mamíferos en el Desierto Chihuahuense, México. Therya 2014, 5, 793–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abáigar, T.; Cano, M.; Ensenyat, C. Habitat preference of reintroduced dorcas gazelles (Gazella dorcas neglecta) in North Ferlo, Senegal. J. Arid Environ. 2013, 97, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, A.P.; Gerngross, P.; Lemeris, J.R., Jr.; Schoonover, R.F.; Anco, C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Durant, S.M.; Farhadinia, M.S.; Henschel, P.; Kamler, J.F.; et al. Leopard (Panthera pardus) status, distribution, and the research efforts across its range. PeerJ. 2016, 4, e1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahumada, J.A.; Silva, C.E.; Gajapersad, K.; Hallam, C.; Hurtado, J.; Martin, E.; McWilliam, A.; Mugerwa, B.; O’Brien, T.; Rovero, F.; et al. Community structure and diversity of tropical forest mammals: Data from a global camera trap network. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2011, 366, 2703–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huerta-Rodríguez, J.O.; Rosas-Rosas, O.C.; López-Mata, L.; Alcántara-Carbajal, J.L.; Tarango-Arámbula, L.A. Camera traps reveal the natural corridors used by mammalian species in eastern Mexico. Ecol. Process. 2022, 11, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán-Antonio, J.; González-Romero, A.; Sosa, V.J. Activity overlap of carnivores, their potential wild prey, and temporal segregation, with livestock in a Biosphere Reserve in the Chihuahuan Desert. J. Mammal. 2020, 101, 1609–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Solano, L.A.; Gallina-Tessaro, S. Activity patterns and their relationship to the habitat use of mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) in the Chihuahuan Desert, Mexico. Therya 2019, 10, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wearn, O.R.; Rowcliffe, J.M.; Carbone, C.; Pfeifer, M.; Bernard, H.; Ewers, R.M. Mammalian species abundance across a gradient of tropical land-use intensity: A hierarchical multi-species modelling approach. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 212, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenville, A.C.; Wardle, G.M.; Dickman, C.R. Desert mammal populations are limited by introduced predators rather than future climate change. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2017, 4, 170384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuipers, K.J.J.; Hilbers, J.P.; Garcia-Ulloa, J.; Graae, B.J.; May, R.; Verones, F.; Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Schipper, A.M. Habitat fragmentation amplifies threats from habitat loss to mammal diversity across the world’s terrestrial ecoregions. One Earth 2021, 4, 1505–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, A.; Murali, G.; Rachmilevitch, S.; Roll, U. Global evaluation of current and future threats to drylands and their vertebrate biodiversity. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 8, 1448–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derebe, B.; Derebe, Y.; Gedamu, B. Composition, relative abundance, and diversity of medium and large mammals in the Lake Tirba Awi area, Ethiopia. Anthr. Sci. 2023, 2, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda, R.A.; Tabeni, S. The mammals of the Monte Desert revisited. J. Arid Environm. 2009, 73, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga-Pacheco, C.J.; Velez-Liendo, X.; Zedrosser, A. Effects of seasonality on the large and medium-sized mammal community in mountain dry forests. Diversity 2024, 16, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas-Sánchez, J.V.; Coates, R.I.; Sánchez-Cordero, V.; Lavariega, M.C.; Flores-Martínez, J.J. Diversity and abundance of the species of arboreal mammals in a tropical rainforest in southeast Mexico. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e70812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, S.; Gange, A.C.; Wiesel, I. An oasis in the desert: The potential of water sources as camera trap sites in arid environments for surveying a carnivore guild. J. Arid Environ. 2016, 124, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroy-Vilchis, O.; Zarco-González, M.M.; Ramírez-Pulido, J.; Aguilera-Reyes, U. Diversidad de mamíferos de la Reserva Natural Sierra Nanchititla, México. Rev. Mex. Biodivers. 2011, 82, 237–248. [Google Scholar]

- Beukes, M.; Perry, T.; Parker, D.M.; Mgqatsa, N. Refining camera trap surveys for mammal detection and diversity assessment in the Baviaanskloof Catchment, South Africa. Wild 2025, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacifi, M.; Di Marco, M.; Watson, J.E.M. Protected areas are now the last strongholds for many imperiled mammal species. Conserv. Lett. 2020, 13, e12748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]