Abstract

Seaweed diseases have been reported in both wild and cultivated seaweed species worldwide. However, reports on tropical seaweed diseases are uncommon and are often focused on farmed species. In the Philippines, seaweed diseases have been reported in economically important species such as Eucheuma, Kappaphycus, and Halymenia. Regarding Halymenia, the occurrence of white rot disease has been reported on laboratory-reared and open sea-outplanted individuals. Here, I report for the first time the occurrence of white rot disease on Halymenia durvillei as observed in the wild. While the disease may have detrimental effects, I hypothesize that the disease and the subsequent breaking of branches may play a role in the dispersal and reproductive success of H. durvillei. Nonetheless, studies on the bio-ecology of its pathogen and the impacts of the disease should be conducted considering the commercial potential of H. durvillei farming.

The red seaweed Halymenia durvillei Bory de Saint-Vincent (Halymeniales, Rhodophyta), characterized by its upright, highly branched, bushy, cartilaginous and slimy thallus, is commonly found attached to hard substrates in the intertidal to shallow subtidal zones of tropical reefs, including in the Philippines [1,2]. An economically important species, H. durvillei can be consumed as food and has been prospected for its commercially important derivatives, such as carrageenan and pigments r-phycoerythrin and r-phycocyanin [3,4].

During the course of our research for development work on H. durvillei, we reported the occurrence and described the progression of a white rot disease on open sea-outplanted crops [4]. At that time, we thought that such disease occurred only on transplanted laboratory-cultured H. durvillei, noting that these were relatively more vulnerable considering that they were initially reared in a sterile environment. While these in vitro cultured H. durvillei have been acclimated in a hatchery facility, they were still grown in a controlled environment.

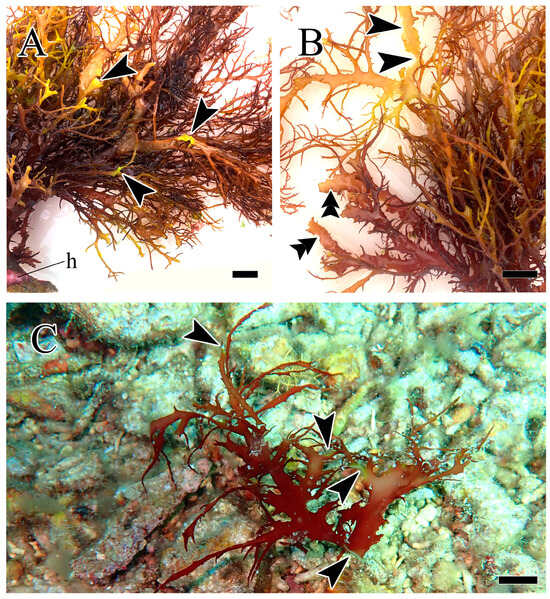

In a research expedition conducted along the coast of Palauig Bay, Zambales, from 3 to 5 May 2024, I observed indications of the natural occurrence of white rot disease in two H. durvillei individuals found on the reef flat (15°24′10.8″ N, 119°53′53.988″ E). One of these H. durvillei individuals (MSI30702; Figure 1A,B) has a red-orange–brown-colored thallus that was attached to a rocky substrate via a discoid holdfast; the other individual is represented by a branch portion (MSI30703; Figure 1C) with deep red coloration. Both individuals were collected at 5–6 m depth, with temperatures of 29–30 °C, and showed indications of white rot disease (Figure 1, arrowheads). Voucher specimens are deposited at the Gregorio T. Velasquez Phycological Herbarium (MSI) of the Marine Science Institute, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines.

Figure 1.

White rot disease-infected Halymenia durvillei found on the reef of Palauig, Zambales, Philippines. (A) Upright thallus of H. durvillei (MSI30702) showing holdfast (h) and branches with discolored and disintegrated portions (arrowhead). (B) Upper portion of H. durvillei thallus (MSI30702) showing infected (arrowhead) and healed (double arrowhead) parts. (C) Drifting apical portion of H. durvillei (MSI30703) showing characteristic discoloration and infected portions (arrowhead). The scale bars measure 1 cm.

In both specimens, I observed the same characteristic semi-circular discoloration and disintegration of branches (Figure 1, arrowheads) that we observed in our previous report [4]. In the case of MSI30702, several branches have margins that have various levels of deformation resulting from tissue degeneration (Figure 1A,B, arrowhead), although some show indications of healing and recovery (Figure 1B, double arrowhead). As for MSI30703, this drifting branch portion is very likely a consequence of the disease as its basal portion also showed tissue discoloration and disintegration, like its other branch portions (Figure 1C, arrowhead). The causative agent(s) of white rot disease in H. durvillei have remained unknown since our first report in 2016, as work on tropical seaweed diseases has largely focused on the commercially important carrageenan-producing red seaweeds Kappaphycus and Eucheuma [5].

Red seaweeds are known to produce a wide array of biochemicals that function as defenses against viruses, bacteria, and fungi [6]. It is therefore curious why such disease is observed in both laboratory-reared and wild H. durvillei. Aside from knowing the identities of the causative agent(s) of white rot disease and the mechanism of their infection on H. durvillei, it is also worth investigating the value of allowing such pathogenic action for the biology of H. durvillei, especially its reproduction. As with other red seaweeds, H. durvillei produces non-motile reproductive structures [7], and propagation and settlement (and consequently, distribution) are therefore dictated by water movement characteristics. However, H. durvillei has also been shown to grow vegetatively under land-based culture conditions [1]. Taking all of these into consideration, allowing white rot disease to progress and break (fertile) branches can be a good strategy for H. durvillei to maximize its reproductive capacity by ‘delivering’ propagules to new colonizable areas, ensuring the proliferation and, consequently, the survival of the species. Nevertheless, it is apparent that further research is needed to answer questions related to my observations and propositions, especially considering commercial importance and the need to conserve wild populations of H. durvillei in anticipation of the demand for its derivatives.

Funding

This work is funded by the Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic, and Natural Resources Research and Development of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST-PCAARRD) of the Government of the Philippines through “Resource Inventory, Valuation and Policy in Ecosystem Services under Threat (RE-INVEST): The Case of the West Philippine Sea. Project 1: Resource Inventory and Assessment of the West Philippine Sea” (Project No. 9610430-499-416).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Seaweed samples were collected with Gratuitous Permit No. 0295-24 from the Department of Agriculture of the Government of the Philippines.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

I thank Fraulein Jan O. Calumpiano and Christine Marie L. Lazaro for their assistance during field work, and the science and ship crews of RV Panata of the Marine Science Institute, University of the Philippines Diliman.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Trono, G.C., Jr. Field Guide and Atlas of the Seaweed Resources of the Philippines; Bookmark: Makati, Philippines, 1997; 306p. [Google Scholar]

- Lastimoso, J.M.L.; Santiañez, W.J.E. An updated checklist of the benthic marine algae of the Philippines. Phil. J. Sci. 2021, 150, 29–92. [Google Scholar]

- Trono, G.C., Jr. A Primer on the Land-Based Culture of Halymenia durvillaei Bory de Saint-Vincent (Rhodophyta); Marine Science Institute, University of the Philippines Diliman: Quezon City, Philippines, 2010; 27p. [Google Scholar]

- Santiañez, W.J.E.; Suan-Flandez, H.J.; Trono, G.C., Jr. White rot disease and epiphytism on Halymenia durvillei Bory de Saint-Vincent (Halymeniaceae, Rhodophyta) in culture. Sci. Diliman 2016, 28, 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Faisan, J.P., Jr.; Luhan, M.R.; Sibonga, R.; Mateo, J.; Ferriols, V.M.E.; Brakel, J.; Ward, G.M.; Ross, S.; Bass, D.; Stentiford, G.; et al. Preliminary survey of pests and diseases of eucheumatoid seaweed farms in the Philippines. J. Appl. Phycol. 2021, 33, 2391–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, M.J.; Falqué, E.; Domínguez, H. Antimicrobial action of compounds from marine seaweed. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bold, H.C.; Wynne, M.J. Introduction to Algae; Prentice-Hall, Inc.: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1985; 662p. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).