Abstract

Cancer continues to be a global health problem due to high mortality rates and resistance to treatment. Since conventional chemotherapies cause serious side effects, interest in natural complementary therapies has increased. In this context, common fig (Ficus carica L.) (F. carica), which stands out with its rich phytochemical content, has been used in traditional medicine for a long time and attracts attention with its anticancer potential. The purpose of this review is to evaluate the biological effects of extracts obtained from different parts of the F. carica plant on cancer cells. Recent in vitro studies have shown that F. carica extracts suppress proliferation, induce apoptosis and reduce oxidative stress in various cancer cell lines. However, factors such as the plant part used, extraction method, dose and application time have caused differences in the results. In vivo studies are limited and there is no clinical study. Some studies report that high doses, especially latex, may cause toxic effects. F. carica extracts are promising against cancer. However, comprehensive in vivo and clinical studies with standardized extracts are needed to transfer this potential to clinical practice.

1. Introduction

Cancer is characterized by unregulated cell proliferation and remains the second leading cause of death worldwide. Globally, an estimated 20 million new cancer cases and 9.7 million deaths from cancer were reported in 2022 [1]. The cancer burden is projected to increase by approximately 77% by 2050, further straining healthcare systems, individuals, and communities [1,2]. One of the main goal in the field of cancer treatment is to formulate innovative approaches that specifically target malignant cells while sparing healthy tissues and reducing the development of resistance to chemotherapeutic compounds. Effective anticancer drugs are expected to exert their effects through mechanisms such as induction of apoptosis, inhibition of cell proliferation, promotion of cellular differentiation, suppression of DNA topoisomerase function, and modulation of intracellular signaling pathways. However, despite significant medical and technological advances, drugs used in traditional cancer treatments still face, in many cases, serious limitations, such as unacceptable toxicity, development of resistance, and the risk of targeting healthy cells and causing adverse effects [3,4]. Therefore, studies investigating the anticancer potential of naturally occurring compounds are gaining increasing importance. These limitations of conventional cancer therapies have intensified interest in exploring naturally occurring compounds as complementary or alternative strategies. Many plant-derived molecules interact with key oncogenic pathways—such as proliferation control, apoptosis induction, and oxidative stress regulation—suggesting that phytochemicals may help bridge current therapeutic gaps and support the development of safer, more targeted anticancer approaches [5,6]. In this context, plants that have been used in traditional medicine for a long time and have a rich pharmacological profile are attracting attention as alternative therapeutic agents. One of these plants, the Ficus genus, is an important group that stands out with its medicinal properties, and one of the most well-known species of this genus is the common fig (Ficus carica L.), which is especially valued for its nutritious fruit [7,8]. Ficus carica L. (the common fig) has a long history of use in traditional medicine in the Mediterranean basin, the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of South Asia and East Africa. Different plant parts are used depending on tradition. The fruits and seeds are eaten for their nutritional and digestive benefits, while leaf decoctions are used for glycemic control and gastrointestinal complaints. The latex is applied topically for warts and other skin conditions. Ethnobotanical studies and pharmacological research document the use of the leaves, fruit, latex, bark, and roots for conditions such as digestive disorders, diabetes, skin conditions, infections, and inflammation. Examples include the traditional topical use of fig latex for verruca vulgaris and the use of fig leaf decoctions in experimental and clinical glycemic control studies [9,10,11]. This species, which naturally spreads from the intersection of Asia and Europe to Northern India, is commercially cultivated in many regions, especially in the Mediterranean countries, thanks to its high adaptability to hot climate conditions. However, its production is limited to certain regions due to its special pollination and drying requirements [12]. The fig is considered a quality fruit due to its high nutritional value. Beyond its nutritional benefits, F. carica serves as a rich source of polyphenols, flavonoids, and other bioactive compounds [13]. Minerals, vitamins, carbohydrates, phenolic compounds, organic acids and various sugars have been determined to be present in high amounts in dried fruits of F. carica. Fiber and polyphenol contents are remarkable in both fresh and dried fruits. Phytochemical analyses show that F. carica is a rich source not only of polyphenols and flavonoids, but also of many biologically active compounds such as β-amyrins, arabinose, β-carotene, β-sitosterols and xanthoxol, as well as various flavonoids and phenolic glycosides (including rutin and quercetin derivatives) [14,15]. Bioactive substances isolated from different parts of the plant include phenolic compounds, organic acids, phytosterols, coumarins, triterpenoids, aliphatic alcohols, and hydrocarbons. In addition to these groups, a number of volatile compounds and other secondary metabolites have been reported in F. carica cultivars. This richness of content is an important indicator supporting the pharmacological potential of the plant. As summarized in the review by Hajam and Saleem (2022) [16], several studies have reported that phenolic compounds, coumarins, flavonoids, and terpenoids isolated from F. carica may exert anticancer effects by inhibiting cancer cell proliferation, inducing apoptosis through mitochondrial pathways, and modulating oxidative stress. These conclusions are based on in vitro findings from human cancer cell lines, including breast, colorectal, and hepatocellular carcinoma models, in which isolated components such as psoralen, bergapten, and quercetin derivatives demonstrated cytotoxic or pro-apoptotic activity [16]. However, the current scientific evidence on these potential biological effects of F. carica is still limited. Comprehensive and systematic studies are needed to more clearly reveal the protective or therapeutic roles of different components of the plant on cancer development.

The aim of this review is to evaluate current scientific studies investigating the anticancer potential of extracts obtained from various parts of the F. carica plant. In line with the studies conducted in recent years, it has been reported that bioactive compounds obtained from different parts of the plant, such as fruit, leaf, latex, bark, and seed, have various biological effects on cancer cells through mechanisms such as inhibiting cell proliferation, inducing apoptosis, reducing oxidative stress and modulating tumor cell-specific signaling pathways [17,18,19]. In this context, in addition to variables such as plant part, extraction method, solvent, dose, and application time used in the review, the effects of the cancer cell lines used on the results were evaluated comparatively.

2. Bioactive Compounds of F. Carica

Phytochemical studies on F. carica have revealed that many biologically active compounds are present in various parts of the plant (latex, leaves, fruits, and roots). These compounds include phytosterols, flavonoids (including anthocyanins), organic acids, aliphatic alcohols and hydrocarbons. When examined in terms of organic acids, malic, citric, oxalic, shikimic and fumaric acids were detected, especially in the leaf extract, along with high amounts of quinic acid. In terms of flavonoid content, luteolin stands out as the main compound in the leaves, followed by quercetin and biochanin A. The antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anticarcinogenic effects of these compounds have been reported in the literature. Phenolic compounds are found in all parts of the fruit; phenols such as caffeoylquinic acid isomers, quercetin derivatives, ferulic acid, psoralen, and bergapten were detected especially intensely in the leaves. Among phytosterols, β-sitosterol was found in the highest amount, while other sterols such as lupeol, α-amyrin, and betulol were also identified [14,16,20,21] (Table 1 and Table 2). In addition, the content of five different polyphenols (-epicatechin, chlorogenic acid, syringic acid, psoralen, and rutin) was determined in F. carica seeds [22].

Table 1.

Phytochemical content of F. carica according to its parts [14,16,23].

Table 2.

Phytosterol and organic acid content of F. carica according to its parts [14,23].

3. Effects of F. carica on Cancer and Its Mechanism of Action

Studies investigating the anticancer effects of F. carica have revealed the potential therapeutic value of various extracts of this plant against different types of cancer. These studies, which were mainly conducted in in vitro and in vivo model systems, have revealed that extracts obtained from different parts of F. carica, such as fruit, leaves, latex and bark, exhibit various biological effects such as cytotoxicity, induction of apoptosis, cell cycle arrest, reduction in cell viability, suppression of migration and invasion [24,25,26,27]. It has been observed that factors such as the extraction methods used, type of solvent, dose intervals, and the exposure times are determinants of the biological effect. In addition, these studies report that the effects of F. carica mostly occur through mechanisms such as ROS production, disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential, caspase activation, p53 regulation and modulation of intracellular signaling pathways. However, some studies have also reported dose-dependent or cell line-specific ineffectiveness. Current evidence suggests that F. carica extracts exhibit significant cytotoxic and apoptotic effects, particularly on breast, liver, colon, and cervix cancer cell lines. Table 3 and Table 4 summarizes the findings from studies investigating the anticancer effects of F. carica.

Table 3.

The potential anticancer effects and underlying mechanisms of F. carica based on in vitro research.

Table 4.

The potential anticancer effects and underlying mechanisms of F. carica based on in vivo research.

3.1. Breast Cancer

The activity of F. carica against breast cancer has been investigated using extracts obtained from its latex, fruit, leaves and bark (Table 3).

A recent study has shown that exposure to varying concentrations (1/1500, 1/900, 1/600, 1/300, 1/180, 1/60, 1/36 and 1/12) of fig latex resulted in a significant decrease in the survival of breast cancer cells, exhibiting a dose-dependent response. The latex showed remarkable cytotoxic activity against MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer models, especially at the highest concentration tested (1/12). Cell viability after treatment was observed as 20.63% and 16.66%, respectively, with half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50) measured at 1/40 and 1/45 [34]. In a different study, researchers characterized the phenolic composition of the latex extract, identifying the presence of luteolin, rutin, quercetin, chlorogenic acid, and caffeic acid. Treatment of MCF-7 cells with this extract resulted in a significant decrease in cell viability. The strongest cytotoxic effect was observed at a concentration of 400 µg/mL, which reduced cell viability to 14 ± 2% (IC50: 134.60 ± 13.52 µg/mL). The researchers attributed this effect to the hydrophilic and hydrophobic interactions between phenolic compounds and proteins expressed by cancer cells. However, the study also reported that latex extract exhibited cytotoxic effects on healthy human skin fibroblasts cells (CCD-45 SK) [19]. Another study reported that F. carica latex exhibited antiproliferative and antimetastatic effects in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. The treatment dose-dependently reduced cell proliferation and migration, induced apoptosis and led to morphological changes. Cytotoxic and genotoxic effects were confirmed by DNA damage analyses, and it was determined that these effects occurred at the molecular level by downregulation of AMPKα, ERK2, CREB, and GSK-3α/β signaling pathways [28].

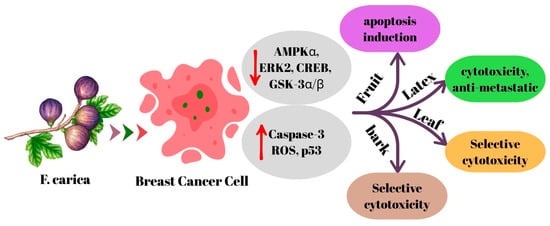

In a recent study, it was determined that F. carica leaf extract showed cytotoxic effects comparable to cisplatin in MCF-7, MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-436 breast cancer cells. This effect was reported to be related to caspase-3 activation by rutin, naringin and catechin compounds found in the extract. It was also reported that the extract showed lower toxicity against healthy peripheral blood mononuclear cells and was more selective against cancer cells [32]. A different study found that the leaf extract showed a significant inhibitory effect on cell viability in MCF-7 cells, while also exhibiting an increase in the percentage of cellular viability of peripheral blood mononuclear cells [25]. These differences from the findings reported by Yahiaoui et al. [19] are likely due to the distinct phytochemical compositions of latex and leaf extracts, which commonly lead to variations in biological activity rather than representing a true contradiction. In a study conducted by Farooq et al. [29], it was reported that nanoparticles obtained from F. carica leaf extract reduced cell viability in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells and increased the effectiveness of the chemotherapeutic drug integrated into these nanoparticles. Shiraishi et al. [31], reported that the leaf extract showed moderate cytotoxic effects in MCF-7 cells. In another study, it was observed that F. carica fruit extract promoted apoptosis in MCF-7 cells, but only had a mild cytotoxic effect [30]. In one study, 2-benzhydrylsulfinyl-N-hydroxyacetamide-Na compound found in F. carica fruit extract was identified and shown to trigger mitochondrial apoptosis in AMJ-13 breast cancer cells by increasing Bax, suppressing Bcl-2, as well as activating p53, caspase-8 and -9 via increasing ROS. The compound effectively inhibited cell proliferation and induced mitochondrial pathway-dependent apoptosis. Furthermore, no changes were observed in liver enzyme levels and lung and spleen tissues, and no significant toxicity was reported [24]. Finally, A recent study revealed that F. carica bark extract did not exhibit cytotoxic effects on healthy macrophage (RAW 264.7) and human skin fibroblast (CCD45-SK) cell lines, even at a high concentration of 400 µg/mL. However, the extract showed significant cytotoxic effect on MCF-7 breast cancer cells at lower concentration (IC50: 143.30 µg/mL), indicating its selective anticancer potential [33]. Ghandehari and Fatemi, in an in vivo experiment, demonstrated the anticancer effect of F. carica latex extract, decreasing tumor size and growth as well as inhibiting metastasis in breast tumor-bearing Wistar rats [47]. The mechanism of action of F. carica on breast cancer is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The mechanism of action of F. carica on breast cancer.

The evidence obtained indicates that F. carica has remarkable anticancer potential against breast cancer cells. Latex, leaf, fruit, and bark extracts have been reported to exhibit cytotoxic, antiproliferative, and apoptosis-inducing effects on different breast cancer cell lines. The latex modulates signaling pathways related to energy and proliferation, while leaf extracts stand out with caspase-3 activation and phytochemical selectivity. Compounds isolated from fruit extracts potently activate mitochondrial apoptosis, while the peel extract is notable for its low toxicity to healthy cells. Although the obtained findings are generally promising, it is understood that phytochemical differences between different types of extracts are decisive for the results. Therefore, before F. carica can be evaluated as a complementary agent in breast cancer treatment, extract standardization, toxicity profile, and mechanisms of action need to be investigated more comprehensively with advanced in vitro and in vivo studies.

3.2. Colon Cancer

The effects of F. carica against colon cancer have been evaluated in various studies with extracts from latex, fruit, leaves and bark of the plant.

A recent study investigated the impact of F. carica latex extracts on HT-29 colon cancer cells, revealing a dose- and time-dependent reduction in cell viability relative to the control group, both before and after digestion. Furthermore, both forms of the extract inhibited colony formation in HT-29 cells, though the undigested extracts exhibited lower IC50 values compared to their digested counterparts. In this study, the digested and undigested forms of F. carica latex extracts were compared using an in vitro gastrointestinal digestion model based on the standardized INFOGEST protocol [49]. Digestion was initiated by subjecting the extracts to sequential oral, gastric, and intestinal phases [38]. A study was conducted on HC-116 colon cancer cells to evaluate the cytotoxic effects of latex extracts from three different varieties of F. carica. The results indicated that the Aberkane and Aghanime varieties exhibited cytotoxic effects, while the El-bakour variety did not show any toxicity. Moreover, it was reported that all varieties exhibited elevated concentrations of cytotoxic activity against the healthy fibroblast cell line (CCD-45SK) [19]. Similarly, another study found that latex obtained from the Yellow Lop variety did not show cytotoxic effects at 10 μg/mL, but reduced HT-29 cell viability by 28.91% after 72 h at 20 μg/mL. Alternatively, latex from the Aydın Siyah variety at the same concentration caused 85.33% cell death. Furthermore, 40 μg/mL Aydın Black latex increased apoptosis by 10-fold, while Yellow Lop latex increased it by 2-fold, and this effect was shown to be related to caspase-3 and -7 activation [35]. The findings of these two studies reveal that F. carica variety is an important factor in terms of biological activity. The difference in activity between varieties may be due to differences in their phytochemical compositions. A recent study reported that nanofibers loaded with F. carica latex showed lower toxicity compared to 5-fluorouracil on normal cells (WI-38) and had significant cytotoxic effects on colon cancer cells (Caco-2) (IC50: 23.96 μg/mL). Molecular analysis revealed upregulation of BCL-2 and downregulation of P53 and TNF, indicating that this treatment could potentially weaken tumor suppressive mechanisms. However, increased P21 gene expression suggests that the antiproliferative effect may be supported by cell cycle arrest [17].

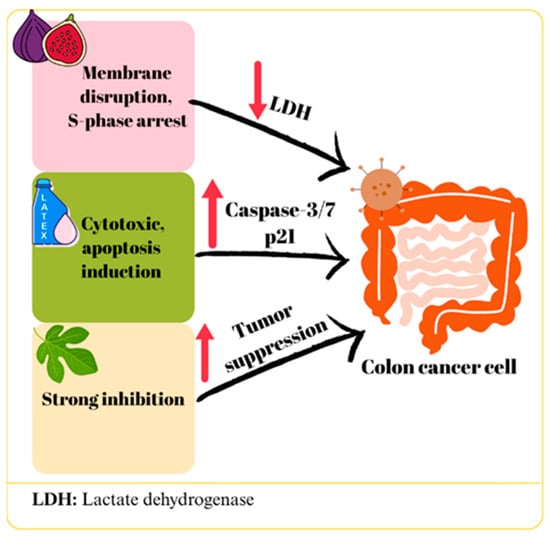

In a study using the Caco-2 cell line, a significant inhibition of cell proliferation was observed when F. carica leaf extract was applied in the concentration range of 5000–156 μg/mL [25]. However, in another study using a similar cell line, no significant cytotoxic effect was detected at an extract concentration of 8 mg/mL [31]. Despite using a comparable cell line and applying concentrations within a similar range, the discrepancies in results may stem from variations in the specific F. carica cultivar used, differences in incubation periods, or unavoidable phytochemical degradation occurring between leaf collection and extract preparation. Abdou et al. [36] evaluated the in vitro and in vivo cytotoxic effects of bergapten isolated from F. carica leaves on C-26 colon cancer cells by loading it into cubosomes. Bergapten-loaded cubosomes exhibited stronger cytotoxicity than free bergapten (IC50 values of 0.015 ± 0.001 μM and 0.062 ± 0.003 μM, respectively, for 72 h incubation), while empty cubosomes did not show toxicity. Additionally, significant reductions in tumor volume and weight were observed in mice treated with bergapten cubosomes in in vivo experiments [36]. A significant cytotoxic effect was observed in HT-29 cells treated with F. carica fruit extract, depending on the dose and time. The increase in lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) levels in the culture medium suggested that this cytotoxic effect may be due to the disruption of cell membrane integrity. Furthermore, the researchers reported that the extract arrested HT-29 cells in S phase (p < 0.007) and that apoptosis rates increased 12-fold in the early phase and 1.5-fold in total after treatment [37]. In a study in which HT-116 cell lines were treated with F. carica bark extract, only a negligible cytotoxic effect was observed even at the highest concentration (400 μg/mL), but this varied among different cultivars [33]. According to Sharma et al. the morin flavonoid content of F. carica inhibited the 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-induced colon cancer in Wistar rats by downregulating the inflammatory and cell proliferation-stimulating NF-κB pathway, including interleukin 6 (IL-6), TNF-α, prostaglandin (PGE-2), and cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2). Furthermore, it increased the BAX/BCL2 ratio, favoring the apoptotic pathway [48]. Hence, morin downregulates both Pumilio-1 (PUM1) and CD133, leading to inhibition of Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs) that may remain after colon cancer treatment [50]. The potential effects of F. carica on colon cancer are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The mechanism of action of F. carica on colon cancer.

Various studies on colon cancer cells have demonstrated that extracts from different parts of F. carica exhibit significant effects, which are dependent on both dose and plant variety. In particular, it appears that the digestive process can weaken the biological activity of extracts, while differences in plant variety can significantly alter toxicity levels. Furthermore, the use of nanotechnological formulations such as cubosomes and nanofibers has been reported to increase the efficacy of extracts while potentially reducing toxicity to healthy cells. However, the inconsistencies in the levels of efficacy observed in different studies are due to differences in the F. carica varieties used, extract preparation methods, and experimental conditions. This suggests that the potential of F. carica in the treatment of colon cancer depends on the development of standardized extract preparation and dosing protocols. Overall, the data support the existence of anticancer effects of the plant, but its efficacy needs to be optimized and its mechanisms investigated in more detail.

3.3. Liver Cancer

The therapeutic capacity of F. carica against liver cancer has been addressed in studies evaluating extracts from various tissue parts, including latex, fruit, leaves, and bark.

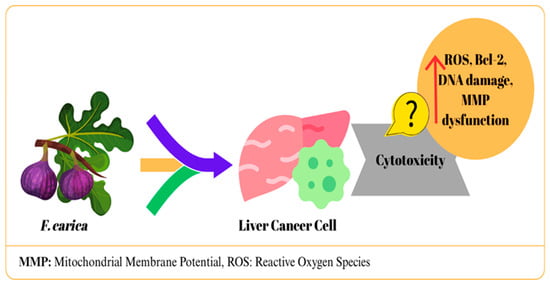

In a study, F. carica latex-loaded nanofiber was determined to have cytotoxic effects on liver cancer cells (HepG2), and the IC50 value was determined as 23.97 μg/mL [17]. Similarly, in HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells, exposure to the highest tested concentration (100 µg/mL) of latex from the three F. carica cultivars (Aberkanei, Aghanime, and El-Bakour) resulted in a marked decrease in cell viability, with the highest IC50 value reported as 19.40 ± 2.69 µg/mL [19]. In another study, F. carica latex was tested with four different solvents in HepG2 cells. The methanol fraction exhibited no cytotoxic activity and promoted cell growth, while the other fractions showed toxic effects. The strongest effect was observed in the chloroform fraction with an IC50 value of 0.2 ± 0.02 mg/mL and was reported to induce apoptosis. This effect was attributed to lupeol acetate and lupeol palmitate identified in the fraction [26]. Mustafa et al. [39] reported that F. carica leaf extract produced dose-dependent cytotoxic effects on HepG2 cells (IC50: 0.081 mg/mL), whereas it did not show significant toxicity up to 2 mg/mL in healthy HUVEC cells. While significant morphological deteriorations were observed in treated HepG2 cells, HUVECs maintained their normal appearance. These differences suggested that the extract exhibited selective apoptotic effects. The researchers stated that this effect was associated with increased ROS production, DNA damage, disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential, suppression of Bcl-2, and downregulation of CDK-1, CDK-5, and CDK-9 [39]. Similarly, Abdel-Rahman et al. [25] reported that leaf extract showed a significant effect in HepG cells with a 66.9% inhibition rate [25]. A study reported that treatment of HepG2 cells with F. carica dried fruit extract provided moderate cytotoxic effects [30]. In one study, the anticancer effects of F. carica fruit essential oils extracted using a hot distillation procedure with water (FCFW) and hexane (FCFH) were investigated in HepG2 cells. It was determined that both extracts showed moderate cytotoxicity; FCFW arrested the cells in S phase, while FCFH did not affect the cell cycle. In the apoptosis analysis, FCFH increased early apoptosis (43.1%), while FCFW increased late apoptosis (30.2%) [40]. In addition, it was observed that both extracts reduced ROS production, which contradicts what was reported by Mustafa et al. (2021) [39]. This discrepancy indicates differences in the anticancer mechanisms of fruit and leaf extracts and suggests that ROS reduction may be a different pathway from classical chemotherapeutic mechanisms [40]. Finally, F. carica wood bark extract showed a weak cytotoxic effect against HepG-2 cells (IC50: ≥100 μg/mL) [33]. The potential effects of F. carica on liver cancer are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The mechanism of action of F. carica on liver cancer.

In general, different tissue extracts of F. carica show anticancer potential in HepG2 cells. Notably, noteworthy that nanofiber formulations increase efficacy while reducing toxicity to healthy cells. The findings vary depending on the tissue used, extraction method, and test conditions. Therefore, standardization of extracts, isolation of active components, and more comprehensive studies at the mechanistic level are required to fully demonstrate the therapeutic potential of F. carica against liver cancer.

3.4. Cervical Cancer

The effects of F. carica on cervical cancer were evaluated through studies performed with latex and fruit-derived extracts of the plant.

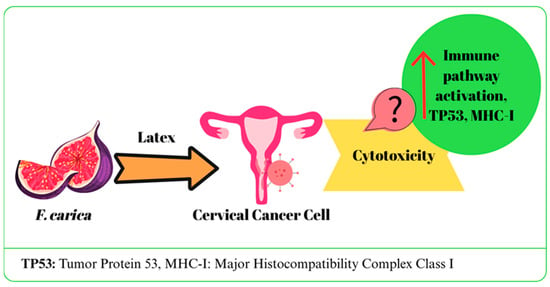

A study investigated the anticancer activity of digested (in vitro) and undigested F. carica latex (white and black varieties) in the HeLa cell line. Although in vitro gastrointestinal digestion was observed to cause a decrease in anticancer properties, all calculated % viability values were reported to be lower compared to the control groups [38]. In two similar studies, the effects of F. carica latex on HPV16+ CaSki, HPV18+ HeLa, and HPV-negative C33A cervical cancer cell lines were evaluated. IC50 values were determined as 106 µg/mL for HeLa, 110 µg/mL for CaSki, and 108 µg/mL for C33A, and no toxicity was observed in healthy HCKT1 cells. Latex application led to upregulation of genes related to immune response, RNA processing and protein degradation, especially in HeLa and CaSki cells, while it activated apoptosis pathways in C33A cells. In addition, it was determined that MHC-I expression and TP53-mediated pathways increased, and the immune escape effect of E5 protein decreased. It has been reported that latex affects cell cycle and immune responses through regulatory molecules such as TAF1, CDK1/4, and MAPK1 [41,42]. In a different study, it was suggested that F. carica fruit extract did not exhibit any cytotoxic effect on HeLa cancer cells (IC50: >1000 µg/mL). Furthermore, when combined with olive oil, it diminished the cytotoxic effect of olive oil [27]. The potential effects of F. carica on cervical cancer are summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The mechanism of action of F. carica on cervical cancer.

Current studies on cervical cancer cells have shown that latex extract the latex extract has a unique activity profile, specifically targeting genetic and immune response mechanisms. In addition, its selective effect is supported by the fact that it does not cause toxicity in healthy cells. However, no cytotoxic effect was observed with the fruit extract. These findings show that the potential of F. carica varies depending on the part of the plant and the method of application. Further in vivo and clinical studies are needed to confirm the efficacy and clarify the mechanisms.

3.5. Other Types of Cancer

The fruit extract of F. carica has been the subject of investigation in the context of pancreatic, ovarian, gastric, and osteosarcoma cancer cell lines.

In one study, the extract (0.1, 0.5, 1.0 mg/mL for 24 h) exhibited low toxicity in Panc-1 and AsPC-1 pancreatic cancer cells, with no significant antiproliferative effect. While the extract slightly reduced cancer cell viability, it did not substantially impact cell proliferation [44]. Conversely, another study reported that F. carica fruit extract exhibited dose- and time-dependent cytotoxic effects on pancreatic cancer cells. The 600 µg/mL extract caused a 60% and 70% decrease in viability in Panc-1 and QGP-1 cells, respectively. Apoptosis was confirmed by increased PARP-1 activation, and cell migration and invasion were suppressed. The extract induced cell death by increasing ROS production, while simultaneously balancing this effect by stimulating autophagy. The decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential and the increase in lipid peroxidation suggested the potential for ferroptosis. In vivo experiments, oral administration of 200 mg/kg extract significantly suppressed tumor growth in mice with QGP-1-induced tumors; increased PARP-1 and LC3A/B expression indicated a collaborative role for apoptosis and autophagy. No toxicity was observed in normal pancreatic cells [43]. The observed variations in results between the two studies may be due to differences in extract composition, solvent choice, preparation techniques, cell models, administered concentrations, exposure duration, and overall experimental preparation. Notably, the extract’s impact on cancer cells seems influenced by both concentration and treatment duration.

Ali et al. [45] reported that the 2-(benzhydrylsulfinyl)-N-sec-butylacetamide compound isolated from F. carica fruit promoted macrophage activation in SKOV-3 ovarian cancer cells by increasing Fcγ receptor expression. When co-administered with trastuzumab, the compound enhanced phagocytic activity and exerted in vivo tumoricidal effects through the induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and mitochondrial activation. Similarly, 2-benzhydrylsulfinyl-N-hydroxyacetamide-Na compound derived from the same plant showed dose-dependent suppression of proliferation and induction of apoptosis in SKOV-3 cells. This effect was associated with downregulation of BCL-2, activation of pro-apoptotic factors, and cytochrome c release due to a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential [24].

A recent study reported that F. carica fruit extract exhibited cytotoxic effects in gastric cancer cells (AGS) in a dose-dependent manner by both increasing ROS production and via apoptosis and DNA damage [18]. Another study reported that the fruit extract promoted cell death in osteosarcoma cancer cells (MG-63) in proportion to dose and time by disrupting the cell membrane structure, reducing mitochondrial activity and DNA damage, although no significant changes were observed in any cell cycle stage [37].

F. carica latex extract was investigated for its cytotoxic effects on prostate and lung cancer cell lines. Aysin et al. [34] reported that latex extract dose-dependently reduced cell viability in A549 lung cancer cells, and the IC50 value was 1/26 dilution [34]. The same observation was documented by Baohong et al., namely that the alcoholic extract of fig fruit latex in A549 xenograft mice significantly inhibited the tumor growth without inducing obvious damage to the liver or kidney normal mouse tissues [51]. Similarly, in another study, the effects of latex obtained from different fig varieties on PC-3 prostate cancer cell line were evaluated; while viability decreased from 84.7% to 19.1% in Sarı Lop variety, this rate decreased from 80.6% to 2.0% in Black variety. These findings indicate that F. carica latex has significant cytotoxic potential against both cancer types [35].

The leaf extract of F. carica has been the subject of investigation in the context of skin and laryngeal cancer cell lines. A study demonstrated that F. carica leaf extract exhibits cytotoxic effects on melanoma cancer cells (B16F10). Notably, the extract decreased cell viability by 50% at 750 μg/mL after 24 h of incubation and 650 μg/mL after 48 h. Nonetheless, these concentration levels did not result in notable toxicity in normal HEK-293 epithelial cells. Furthermore, findings from the study suggested that the extract induced programmed cell death in melanoma cells via the mitochondrial pathway, leading to an upregulation of caspase-3, caspase-9, P53, and BAX gene expression. Notably, at elevated doses (650–750 μg/mL), the expression of apoptosis-associated genes exhibited a substantial increase compared to the control reference gene [46]. Additionally, research by Abdel-Rahman et al. [25] provided evidence of the cytotoxic impact of F. carica leaf extract on laryngeal cancer cell lines [25].

In pancreatic cancer models, F. carica extract-induced autophagy appears to be regulated via the mTOR/AMPK axis, as suggested by concurrent PARP-1 and LC3A/B upregulation. However, upstream regulators such as Nrf2 and MAPK remain to be investigated [6].

3.6. Comparative Summary Across Cancer Types

Across different cancer types, F. carica extracts commonly induce mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis through ROS generation, P53 activation, and caspase signaling. Latex and leaf extracts show similar molecular patterns, whereas fruit extracts exert milder and more variable responses. When comparing the extracts, latex generally demonstrates the strongest cytotoxic and pro-apoptotic activity but also presents a greater risk of toxicity in normal cells. Leaf extracts exhibit strong anticancer potential with better selectivity, likely due to their high polyphenolic content (quercetin, luteolin, rutin). Fruit extracts tend to show moderate effects, possibly due to lower concentrations of triterpenes and coumarins. These findings suggest that leaf-based extracts may offer the most favorable therapeutic profile, while latex requires further safety validation.

3.7. Contradictions and Gaps

Several studies have reported opposing trends regarding ROS modulation, indicating both antioxidant and pro-oxidant behavior depending on extract composition and dose. This duality highlights the need for standardized extraction methods and comparative mechanistic assays to reconcile the discrepancies observed across studies.

A concise summary of the comparative properties of different F. carica extracts is presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of the comparative properties of different F. carica extracts.

4. Safety

The safety of F. carica and its extracts remains an important issue in the evaluation of their potential therapeutic applications. In popular medicine for several hundred years, the fruits of F. carica have been used for laxative, nose bleeding, or skin problems, e.g., leprosy, or as an emollient, demulcent. Also, it was utilized as an antipyretic, aphrodisiac, lithontriptic, or painkiller. The latex of F. carica has been employed as an expectorant, diuretic, and anthelmintic. The leaves have been utilized to treat diabetes, among others [52]. Remarkably, F. carica exhibits a diverse array of advantageous effects, including, but not limited to, antioxidant, anti-neurodegenerative, antimicrobial, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, anti-arthritic, antiepileptic, anticonvulsant, anti-hyperlipidemic, anti-angiogenic, antidiabetic, anticancer, and antimutagenic properties [53]. In summary, the multifarious utilization could be underpinned by the anti-inflammatory effects of different plant parts, as demonstrated in this study. Hence, the mentioned indications probably determined the categories of utilization, excluding inadequate use, for example, the consumption of the fruit with diarrhea.

Most in vitro studies have reported significant anticancer activity in different cancer cell lines; nevertheless, in vivo evidence regarding toxicity and safety is rather limited and insufficient. Studies have shown that F. carica extracts have a selective affinity for cancer cells while showing minimal toxicity to normal cells. However, this selectivity is largely dependent on factors such as the type of extract, the solvent used, the dosage, and the duration of treatment [52].

The systemic effects of F. carica extracts at higher doses in in vivo models have not been adequately investigated, and some reports indicate that certain plant parts—particularly the latex—may be toxic to normal cells at elevated concentrations. Given the scarcity of in vivo data and these toxicity concerns, the review cannot provide definitive information regarding the therapeutic applicability of F. carica extracts. Therefore, current findings remain insufficient to guide clinical or systemic use, highlighting the need for well-designed in vivo studies, toxicity assessments, and extract standardization before translation into therapeutic practice can be considered. For example, fig latex extracts exhibited cytotoxic effects on normal fibroblast cells (CCD-45SK) at concentrations above 100 µg/mL [19], whereas leaf extracts showed no significant toxicity up to 2 mg/mL in HUVEC cells [39]. These data suggest a relatively wider therapeutic window for leaf extracts.

Furthermore, while several studies describe antioxidant properties that may contribute to its anticancer effects, others indicate potential pro-oxidant activity that could be detrimental under specific conditions. Toxic manifestations reported at high doses include irritation, oxidative damage, or mitochondrial dysfunction, particularly with latex or essential oil fractions rich in thujones and coumarins. To date, there is no standardized toxicological assessment, and the safe-use limits have not been clearly established [54].

On the other hand, in one patient anaphylactic reaction occurred after ingestion of a fresh fig fruit. In that case, the IgE-dependent allergic mechanism was demonstrated based on the positivity of the prick test with fresh Ficus 5 extract. However, presumably, weeping fig (Ficus benjamina) initiated sensitization in that patient [55]. Furthermore, rarely acute contact urticaria to F. carica may occur [56]. Hence, ficin is the major allergen component of F. carica, belonging to the cysteine protease family, such as Der p 1 [57].

Furthermore, ficin can activate the coagulation factor X, a key step in the blood clotting cascade [58]. Also, the vitamin K in F. carica can interfere with the effectiveness of anticoagulant drugs (blood thinners) [53,59].

Another critical concern is the complete lack of clinical studies evaluating the long-term safety of F. carica in humans. Without comprehensive pharmacokinetic and toxicological evaluations, it is difficult to determine the safe dosage range for therapeutic use. In addition, interactions with conventional chemotherapy or other drugs have not yet been investigated, raising concerns about possible side effects [53]. Given these uncertainties, comprehensive in vivo and longitudinal randomized controlled trials are imperative to evaluate F. carica extracts’ safety. Standardized toxicity assessments, dose optimization studies, and long-term safety analyses will be critical to determining whether F. carica can be safely incorporated into anticancer treatment strategies. Until evidence is available, caution should be exercised when evaluating its use beyond experimental settings.

5. Discussion

F. carica is a plant with a long history of use in traditional medicine and shows remarkable potential in modern oncological research. Current literature suggests that extracts derived from F. carica fruit, leaves, and latex can exhibit anticancer activity in various cancer cell lines, such as pancreas, ovary, stomach, osteosarcoma, lung, prostate, skin, and larynx cancer models. These effects have been associated with mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis, increased ROS production, activation of anti-proliferative mechanisms, induction of autophagy, and, in some cases, initiation of alternative cell death pathways such as ferroptosis. In addition, some studies have shown that compounds isolated from F. carica may also play a role in tumor suppression via the immune system. Nonetheless, the mechanisms explaining the pharmacological effects of F. carica and the specific bioactive compounds that cause these effects remain largely undefined. A significant limitation of the current findings is that the anticancer effect is largely based on in vitro data. A critical parameter in assessing the clinical applicability of herbal extracts is whether the concentrations used are pharmacologically relevant. Although no universally accepted standard defines precise potency thresholds for crude extracts, the literature commonly refers to approximate ranges to guide interpretation. Generally accepted efficacy thresholds for extracts in the literature are reported as IC50 < 50 µg/mL for strong cytotoxicity, 50–100 µg/mL for moderate activity, and > 200 µg/mL for poor pharmacological applicability. These ranges, however, are not definitive and may vary depending on experimental design and methodological differences among studies [60,61]. While some of the studies included in this review demonstrated efficacy below this range, some examples, particularly latex and polar extracts, appear to produce cytotoxic effects only at very high concentrations [25,33]. This suggests that the observed in vitro effect may have limited translational relevance in terms of in vivo bioavailability and tissue distribution. Significant inconsistencies among studies are due to methodological differences, such as the plant parts from which the extracts were prepared, the solvents used, doses, application times, and the variety of cell lines used in the studies. This heterogeneity complicates the comparative assessment of the anticancer potential of F. carica. Also, the use of crude extracts in many studies leaves the true biological source of the anticancer effect unclear. Given the known low oral bioavailability, rapid metabolic transformation, and poor systemic stability of phenolic compounds, the use of extracts as direct therapeutic agents is limited from a pharmacokinetic perspective. Therefore, the use of biodirected fractionation methods to isolate individual bioactive compounds and define the pharmacodynamic mechanisms specific to these molecules appears to be a more ra-tional approach. Indeed, some isolated compounds appear to have significantly lower IC50 values compared to crude extracts. Regarding safety, although many studies indicate that F. carica extracts selectively target cancer cells and cause minimal toxicity to normal cells, these results are generally short-term and confined to cell culture. It has been reported that some plant parts, especially latex, can show toxicity in normal cells at high concentrations. Also, contrary to some findings, limited data suggest that F. carica may promote tumor development under certain conditions, highlighting the condition-dependent effects of the plant. Therefore, the safety profile should be examined from a broad perspective, not only through toxicity assessments but also by identifying potential tumor-promoting effects. Moreover, in addition to antioxidant effects, the potential for pro-oxidant activity may also pose a risk under certain conditions. Currently, there is insufficient pharmacokinetic, toxicological, or clinical evidence to evaluate the long-term safety of F. carica in humans.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, although F. carica demonstrates promising anticancer potential against various types of cancer, the bioactive compounds mediating these effects and their underlying mechanism remain inadequately characterized. Before clinical application, comprehensive in vivo studies and well-designed controlled clinical trials utilizing standardized extracts are essential to rigorously evaluate both the efficacy and safety profile of F. carica. For example, in preclinical small animal studies, a careful choice of parts (excluding leaves) or purification of components, or an absence genetic version of F. carica will be needed to avert anticoagulant effects of coumarin as well as liver- and neurotoxic effects of thujones. Such studies are critical to determine whether F. carica can be incorporated into anticancer treatment strategies on a scientific basis. Future research should elucidate the upstream signaling regulators, such as Nrf2, MAPK, and mTOR, that may integrate oxidative stress responses and autophagy pathways induced by F. carica compounds.

Here we need to highlight that potential allergic and anticoagulant effects, as well as blood sugar level-decreasing effects of F. carica, indicate precautions before treatment of potentially sensitive patients with its extracts or even the first consumption of the fruits.

Author Contributions

E.N.G.: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review and Editing. S.G.: Formal Analysis, Writing, Review and Editing. B.L.R.: Supervision, Review and Editing. D.S.: Supervision, Review and Editing. F.B.: Supervision, Review and Editing. D.A.: Supervision, Review and Editing, Project Administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- WHO. Cancer Fact Sheet. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- WHO. World Cancer Day. 2024. Available online: https://www.emro.who.int/media/news/world-cancer-day-2024.html (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Zhou, R.; Tang, X.; Wang, Y. Emerging strategies to investigate the biology of early cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2024, 24, 850–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiri, S.; Ryba, T. Cancer, metastasis, and the epigenome. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranjan, A.; Ramachandran, S.; Gupta, N.; Kaushik, I.; Wright, S.; Srivastava, S.; Das, H.; Srivastava, S.; Prasad, S.; Srivastava, S.K. Role of Phytochemicals in Cancer Prevention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, L.; Ren, D. Anti-Cancer Potential of Phytochemicals: The Regulation of the Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Molecules 2023, 28, 5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, M.Y.; Alshaikhi, A.I.; Hazzazi, J.S.; Kurdi, J.R.; Ramadan, M.F. Recent insight on nutritional value, active phytochemicals, and health-enhancing characteristics of fig (Ficus craica). Food Saf. Health 2024, 2, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holic, R.; Xu, Y.; Caldo, K.M.P.; Singer, S.D.; Field, C.J.; Weselake, R.J.; Chen, G. Bioactivity and biotechnological production of punicic acid. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 3537–3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlooli, S.; Mohebipoor, A.; Mohammadi, S.; Kouhnavard, M.; Pashapoor, S. Comparative study of fig tree efficacy in the treatment of common warts (Verruca vulgaris) vs. cryotherapy. Int. J. Dermatol. 2007, 46, 524–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen Irudayaraj, S.; Christudas, S.; Antony, S.; Duraipandiyan, V.; Naif Abdullah, A.D.; Ignacimuthu, S. Protective effects of Ficus carica leaves on glucose and lipids levels, carbohydrate metabolism enzymes and β-cells in type 2 diabetic rats. Pharm. Biol. 2017, 55, 1074–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mon, A.M.; Shi, Y.; Yang, X.; Hein, P.P.; Oo, T.N.; Whitney, C.W.; Yang, Y. The uses of fig (Ficus) by five ethnic minority communities in Southern Shan State, Myanmar. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2020, 16, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayuso, M.; Carpena, M.; Taofiq, O.; Albuquerque, T.G.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Oliveira, M.B.P.; Prieto, M.A.; Ferreira, I.C.; Barros, L. Fig “Ficus carica L.” and its by-products: A decade evidence of their health-promoting benefits towards the development of novel food formulations. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 127, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayrak, Ç.; Birinci, C.; Kemal, M.; Kolayli, S. The Phenolic Composition and Antioxidant Properties of Figs (Ficus carica L.) Grown in the Black Sea Region. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2023, 78, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrigal-Santillán, E.; Portillo-Reyes, J.; Morales-González, J.A.; Sánchez-Gutiérrez, M.; Izquierdo-Vega, J.A.; Valadez-Vega, C.; Álvarez-González, I.; Chamorro-Cevallos, G.; Morales-González, Á.; Garcia-Melo, L.F.; et al. A review of Ficus L. genus (Moraceae): A source of bioactive compounds for health and disease. Part 1. Am. J. Transl. Res. 2024, 16, 6236–6273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Li, S.; Li, C.; Wang, T.; Tian, Y.; Li, X. Flavonoids from Fig (Ficus carica Linn.) Leaves: The Development of a New Extraction Method and Identification by UPLC-QTOF-MS/MS. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajam, T.A.; Saleem, H. Phytochemistry, biological activities, industrial and traditional uses of fig (Ficus carica): A review. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2022, 368, 110237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Fawal, G.; Sobhy, S.E.; Hafez, E.E. Biological activities of fig latex -loaded cellulose acetate/poly(ethylene oxide) nanofiber for potential therapeutics: Anticancer and antioxidant material. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 270, 132176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metin Guler, E.; Nur Ozkan, B.; Bozali, K.; Dundar, T.; Kocyigit, A. Ficus carica L. extract: A glimmer of hope on AGS human gastric adenocarcinoma. World Cancer Res. J. 2024, 11, e2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahiaoui, S.; Kati, D.E.; Ali, L.M.A.; El Cheikh, K.; Morére, A.; Menut, C.; Bachir-bey, M.; Bettache, N. Assessment of antioxidant, antiproliferative, anti-inflammatory, and enzyme inhibition activities and UPLC-MS phenolic determination of Ficus carica latex. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 178, 114629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Song, X.Y.; Hu, X.S.; Chen, F.; Ma, C. Health benefits of proanthocyanidins linking with gastrointestinal modulation: An updated review. Food Chem. 2023, 404, 134596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivarelli, S.; Costa, C.; Teodoro, M.; Giambo, F.; Tsatsakis, A.M.; Fenga, C. Polyphenols: A route from bioavailability to bioactivity addressing potential health benefits to tackle human chronic diseases. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 3–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakilcioglu-Tas, E.; Otles, S. Influence of extraction solvents on the polyphenol contents, compositions, and antioxidant capacities of fig (Ficus carica L.) seeds. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2021, 93, e20190526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badgujar, S.B.; Patel, V.V.; Bandivdekar, A.H.; Mahajan, R.T. Traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology of Ficus carica: A review. Pharm. Biol. 2014, 52, 1487–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Salman, H.N.K.; Ali, E.T.; Jabir, M.; Sulaiman, G.M.; Al-Jadaan, S.A.S. 2-Benzhydrylsulfinyl-N-hydroxyacetamide-Na extracted from fig as a novel cytotoxic and apoptosis inducer in SKOV-3 and AMJ-13 cell lines via P53 and caspase-8 pathway. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2020, 246, 1591–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Rahman, R.; Ghoneimy, E.; Abdel-Wahab, A.; Eldeeb, N.; Salem, M.; Salama, E.; Ahmed, T. The therapeutic effects of Ficus carica extract as antioxidant and anticancer agent. South Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 141, 273–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeivad, F.; Yassa, N.; Ostad, S.N.; Hassannejad, Z.; Gheshlaghi, G.H.; Sabzevari, O. Ficus carica l. Latex: Possible chemo-preventive, apoptotic activity and safety assessment. Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 2020, 19, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyaningrum, N.; Hussaana, A.; Puspitasari, N.A. Invitro Antioxidant and Cytotoxic Potential of Ficus carica L. and Olea europeae L. Against Cervical Cancer. Sains Med. 2020, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlGhalban, F.M.; Khan, A.A.; Khattak, M.N.K. Comparative anticancer activities of Ficus carica and Ficus salicifolia latex in MDA-MB-231 cells. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 3225–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, I.; Noor, S.; Sajjad, S.; Ashraf, S.; Sadaf, S. Functionalization of Biosynthesized CQDs Capped AgO/ZnO Ternary Composite Against Microbes and Targeted Drug Delivery to Tumor Cells. J. Clust. Sci. 2023, 34, 2681–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangsopha, J.; Moongngarm, A.; Pornchaiyaphum, S.; Bandorn, A.; Khaejonlarp, R.; Pluemjia, B. Chemical compositions, phytochemicals, and biological activity of dried edible wild fruits. Pak. J. Agric. Sci. 2023, 60, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraishi, C.S.H.; Zbiss, Y.; Roriz, C.L.; Dias, M.I.; Prieto, M.A.; Calhelha, R.C.; Alves, M.J.; Heleno, S.A.; da Cunha Mendes, V.; Carocho, M.; et al. Fig Leaves (Ficus carica L.): Source of Bioactive Ingredients for Industrial Valorization. Processes 2023, 11, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikent, A.; Laaraj, S.; Bouddine, T.; Chebaibi, M.; Bouhrim, M.; Elfazazi, K.; Alqahtani, A.S.; Noman, O.M.; Hajji, L.; Rhazi, L.; et al. Antioxidant potential, antimicrobial activity, polyphenol profile analysis, and cytotoxicity against breast cancer cell lines of hydro-ethanolic extracts of leaves of (Ficus carica L.) from Eastern Morocco. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1505473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahiaoui, S.; Kati, D.E.; Chaalal, M.; Ali, L.M.A.; El Cheikh, K.; Depaepe, G.; Morère, A.; Menut, C.; Bettache, N.; Bachir-Bey, M. Antioxidant, antiproliferative, anti-inflammatory, and enzyme inhibition potentials of Ficus carica wood bark and related bioactive phenolic metabolites. Wood Sci. Technol. 2024, 58, 1051–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aysin, F.; Şimşek Özek, N.; Acet, N.; Koc, K. The Anti-Proliferative Effects of Ficus carica Latex on Cancer and Normal Cells [Ficus carica Sütünün Kanser ve Normal Hücre Üzerindeki Anti-proliferatif Etkileri]. J. Anatol. Environ. Anim. Sci. 2024, 9, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyacıoğlu, O.; Kara, B.; Tecimen, S.; Kılıç, M.; Delibaş, M.; Erdoğan, R.; Özdemir, E.; Bahadır, A.; Örenay-Boyacıoğlu, S. Antiproliferative effect of Ficus carica latex on cancer cell lines is not solely linked to peroxidase-like activity of ficin. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2021, 45, 101348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdou, R.; Mojally, M.; Attia, H.G.; Dawoud, M. Cubic nanoparticles as potential carriers for a natural anticancer drug: Development, in vitro and in vivo characterization. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2023, 13, 2463–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalçınkaya, T.; Kozacı, L.D.; Çarhan, A. Ficus carica extract causes cell cycle arrest and induces apoptosis in MG-63 and HT-29 cancer cell lines. Turk. Hij. Den. Biyol. Derg. 2023, 80, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeniocak, S.; Karaduman-Yesildal, T.; Arslan, M.E.; Toraman, G.C.; Yücetepe, A. Effect of In Vitro Digestion on Anticancer and Antioxidant Activity of Phenolic Extracts From Latex of Fig Fruit (Ficus carica L.). Chem. Biodivers. 2024, 22, e202401624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, K.; Yu, S.X.; Zhang, W.; Mohamed, H.; Naz, T.; Xiao, H.F.; Liu, Y.X.; Nazir, Y.; Fazili, A.A.; Nosheen, S.; et al. Screening, characterization, and in vitro-ROS dependent cytotoxic potential of extract from Ficus carica against hepatocellular (HepG2) carcinoma cells. South. Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 138, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalefa, N.K.; Al-Shawi, A.A.A. The essential oils isolated from the fruit of Ficus carica induced reactive oxygen species and apoptosis of human liver cancer cells. Egypt. J. Chem. 2023, 66, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakir, M.O.; Bilge, U.; Ghanbari, A.; Ashrafi, G.H. Regulatory Effect of Ficus carica Latex on Cell Cycle Progression in Human Papillomavirus-Positive Cervical Cancer Cell Lines: Insights from Gene Expression Analysis. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cakir, M.O.; Bilge, U.; Naughton, D.; Ashrafi, G.H. Ficus carica Latex Modulates Immunity-Linked Gene Expression in Human Papillomavirus Positive Cervical Cancer Cell Lines: Evidence from RNA Seq Transcriptome Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 13646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, A.X.; Zhao, X.X.; Lu, Z.M. Autophagy is involved in Ficus carica fruit extract-induced anti-tumor effects on pancreatic cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 150, 112966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekdouk, N.; Ameddah, S.; Bensouici, C.; Ibtissem, M.; Ahmed, M.; Martel, F. Antioxidant properties and anticancer activity of Olea europaea L. olive and Ficus carica fruit extracts against pancreatic cancer cell lines. Trends Phytochem. Res. 2024, 8, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, E.T.; Al-Salman, H.N.K.; Rasool, K.H.; Jabir, M.S.; Ghimire, T.R.; Shari, F.H.; Hussein, H.H.; Al-Fregi, A.A.; Sulaiman, G.M.; Khalil, K.A.A.; et al. 2-(Benzhydryl sulfinyl)-N-sec-butylacetamide) isolated from fig augmented trastuzumab-triggered phagocytic killing of cancer cells through interface with Fcγ receptor. Nat. Prod. Res. 2023, 37, 4112–4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghizade, M.; Baharara, J.; Salek, F.; Amini, E. Assessment the Effect of Ficus carica Leaf Extract on B16F10 Melanoma Cancer Cells: The Roles of p53, Caspase-3 & Caspase-9 on Induction of Intrinsic Apoptosis Cascade. Jundishapur J. Nat. Pharm. Prod. 2022, 17, e117429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghandehari, F.; Fatemi, M. The effect of Ficus carica latex on 7 2018, 12-dimethylbenz (a) anthracene-induced breast cancer in rats. Avicenna J. Phytomed 2018, 8, 286–295. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.H.; Kumar, J.S.; Chellappan, D.R.; Nagarajan, S. Molecular chemoprevention by morin—A plant flavonoid that targets nuclear factor kappa B in experimental colon cancer. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 100, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minekus, M.; Alminger, M.; Alvito, P.; Ballance, S.; Bohn, T.; Bourlieu, C.; Carrière, F.; Boutrou, R.; Corredig, M.; Dupont, D.; et al. A standardised static in vitro digestion method suitable for food—An international consensus. Food Funct. 2014, 5, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gor, R.; Saha, L.; Agarwal, S.; Karri, U.; Sohani, A.; Madhavan, T.; Pachaiappan, R.; Ramalingam, S. Morin inhibits colon cancer stem cells by inhibiting PUM1 expression in vitro. Med. Oncol. 2022, 39, 251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baohong, L.; Zhongyuan, L.; Ying, T.; Beibei, Y.; Wenting, N.; Yiming, Y.; Qinghua, C.; Qingjun, Z. Latex derived from Ficus carica L. inhibited the growth of NSCLC by regulating the caspase/gasdermin/AKT signaling pathway. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 2239–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morovati, M.R.; Ghanbari-Movahed, M.; Barton, E.M.; Farzaei, M.H.; Bishayee, A. A systematic review on potential anticancer activities of Ficus carica L. with focus on cellular and molecular mechanisms. Phytomedicine 2022, 105, 154333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazel, M.F.; Abu, I.F.; Mohamad, M.H.N.; Mat Daud, N.A.; Hasan, A.N.; Aboo Bakkar, Z.; Md Khir, M.A.N.; Juliana, N.; Das, S.; Mohd Razali, M.R.; et al. Physicochemistry, Nutritional, and Therapeutic Potential of Ficus carica—A Promising Nutraceutical. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2024, 18, 1947–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, R.; Chauhan, A.; Kanta, C. A critical review of antioxidant potential and pharmacological applications of important Ficus species. J. HerbMed Pharmacol. 2024, 13, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechamp, C.; Bessot, J.C.; Pauli, G.; Deviller, P. First report of anaphylactic reaction after fig (Ficus carica) ingestion. Allergy 1995, 50, 514–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, N.V.; Bahna, S.L.; Knight, A.K. Fig Allergy: Not Just Oral Allergy Syndrome (OAS). J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007, 119, S110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbani, S.; Aruanno, A.; Nucera, E. Adverse reaction to Ficus Carica: Reported case of a possible cross-reactivity with Der p1. Clin. Mol. Allergy 2020, 18, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, G.; Schwarz, H.P.; Dorner, F.; Turecek, P.L. Activation and inactivation of human factor X by proteases derived from Ficus carica. Br. J. Haematol. 2002, 119, 1042–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakima, B.; Sara, H. Anticoagulant Activity of Some Ficus carica Varieties Extracts Grown in Algeria. Acta Sci. Nat. 2019, 6, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canga, I.; Vita, P.; Oliveira, A.I.; Castro, M.; Pinho, C. In Vitro Cytotoxic Activity of African Plants: A Review. Molecules 2022, 27, 4989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belete, T.M.; Beyna, A.T. Review on the Ethnopharmacological Use of Medicinal Plants and Their Anticancer Activity from Preclinical to Clinical Trial. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2025, 20, 1934578X251333027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.