Abstract

Ring Box Protein-1 (RBX1) is an essential component of the Skp1-cullin-F-box protein (SCF) E3 ubiquitin ligase, which is involved in the regulation of oocyte maturation in the form of ubiquitination substrate modification. In this study, a sequence of RBX1 (Sp-RBX1) was identified and analyzed using bioinformatics methods from the transcriptome data of Scylla paramamosain. The length of Sp-RBX1 cDNA sequence was 1247 bp, consisting of a 336 bp open reading frame (ORF). Sequence analysis revealed that the protein contained a C-terminal modified RING-H2 finger domain, with two zinc binding sites and a Cullin binding site, classifying it as a member of the RBX1 superfamily. The results of real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) showed that Sp-RBX1 expression in the ovary was low at stages I and II, then significantly increased from stage III to V (p < 0.05), which indicated that it might be closely related to the maturation of oocytes. It also peaked at stage II in the hepatopancreas, then sharply declined from stages III to V. The expression pattern might be related to the accumulation of fat in the early development of hepatopancreas. Furthermore, we characterized the expression of Sp-RBX1 induced by follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and estradiol (E2) hormones. The results showed that the expression in the ovary was up-regulated by FSH and significantly inhibited by E2. The expression in the hepatopancreas increased only at 0.5 µmol/L concentration of FSH, and decreased in other groups. Conversely, it was up-regulated by E2. Thus, the expression of Sp-RBX1 was influenced by FSH in a concentration-dependent manner. These findings could offer valuable insights for further research on ovarian maturation in crustaceans.

1. Introduction

The mud crab Scylla paramamosain (Crustacea: Decapoda: Portunidae: Scylla) is an economically important species in China and Southeast Asia [1]. In China, the total yield of S. paramamosain amounted to 224 thousand tons in 2023 [2]. Female crabs possess more economical and nutritional value, due to their matured ovaries, than males. The development of ovaries can be divided into five stages: undeveloped (stage I), pre-vitellogenic (stage II), early vitellogenic (stage III), late vitellogenic (stage IV), and mature (stage V) [3]. Oocyte maturation is a complex process involving the interaction of extra-ovarian and intra-ovarian signals [4,5]. The maturation process can be affected by some hormones, such as follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and estradiol (E2) [6,7,8,9].

Ring Box Protein-1 (RBX1) is an important component involved in ubiquitination processes [10]. The process targets the proteasome-mediated degradation of multiple proteins [11]. RBX1 protein is involved in various cellular processes by targeting multiple substrates, such as cyclin regulation, cell transcription, and signal transduction [12,13]. RBX1 protein is expressed in reproductive cells, and it is potentially significant as a maternal protein in the maturation of oocytes, early embryonic development, and other related processes [14]. It has been reported that reproductive cells exhibited evident abnormalities in meiosis and cell proliferation after RNAi-mediated knockdown of RBX1 gene [15]. RBX protein homologs also influence the development of reproductive cells [16], and the absence of RBX1 gene can result in individual mortality and male infertility [17].

So far, the research on RBX1 protein in the development of aquatic organisms is limited. RBX1 plays a key role in spermatogenesis of Eriocheir sinensis through forming a complex with Cullin4 [18]. RBX1 is essential for cardiac wall morphogenesis in zebrafish [19]. RBX1 protein exhibits ubiquitin ligase activity and indirectly contributes to the immune response in Haliotis diversicolor supertexta through self-ubiquitination [20]. In this study, we focused on the relationship between the RBX1 gene and oocyte maturation. We obtained and analyzed the cDNA sequence of RBX1 in S. paramamosain, examined RBX1 expression patterns in various tissues and during different ovarian stages, and subsequently characterized the hormone-induced expression of Sp-RBX1 gene by FSH and E2 in vitro. This research provides a theoretical reference for further study of RBX1 on oocyte maturation and ovarian development in S. paramamosain.

2. Results

2.1. RBX1 cDNA Sequence and Coded Protein

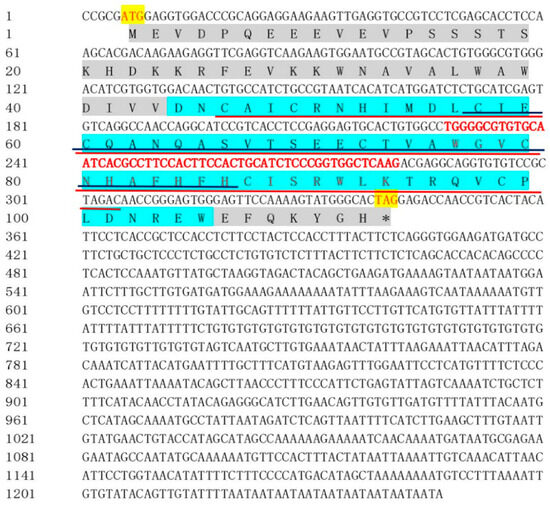

In this study, a homolog of RBX1 was obtained from our transcriptome data and verified to be the RBX1 ortholog, which was named Sp-RBX1 and deposited in GenBank (Accession No. PX688505). The cDNA was 1247 bp in length, with a 336 bp ORF, a 5 bp 5′-untranslated region (5′ UTR), and a 906 bp 3′-untranslated region (3′ UTR). This ORF encoded a 111-amino-acid protein, and the calculated molecular mass was 13.08 kDa (Figure 1). The possible molecular formula of the RBX1 protein was C573H867N163O170S10, and the isoelectric point (pI) was 5.63. The predicted results indicated a total of 17 negatively charged amino acids, and 12 positively charged amino acids. The proportion of valine and glutamic acid in the amino acid composition was up to 9.8%, followed by alanine (8.0%). The RBX1 protein was predicted to contain a modified RING finger domain at its C-terminus, spanning amino acid residues 132 to 317. This domain included two zinc binding sites (138–305 and 171–260) and a Cullin binding site (228–281).

Figure 1.

cDNA and deduced amino acid sequence of RBX1 from S. paramamosain. Note: The start codon (ATG) and stop codon (TAG) are in the yellow box; the asterisk "*" is marked as a termination codon; the gray regions represent the C-terminal conserved domain: the blue shadow region indicates RING finger domain (132~317); the red line indicates a Zn binding site (138–305), the dark blue line indicates another zinc binding site (171–260), and the red sequence indicates a Cullin binding site (228–281).

2.2. RBX1 Multiple Sequence Alignment and Phylogenetic Analysis

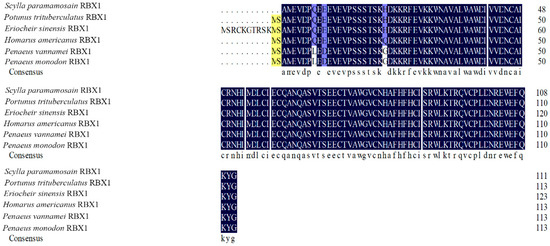

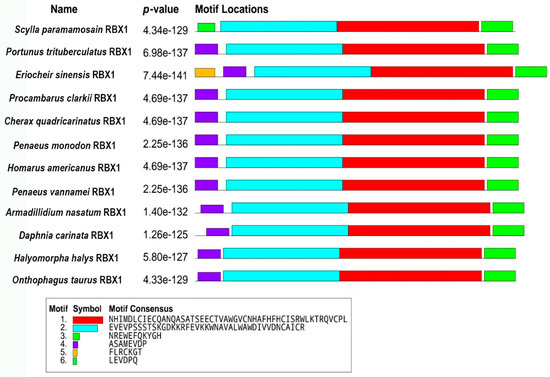

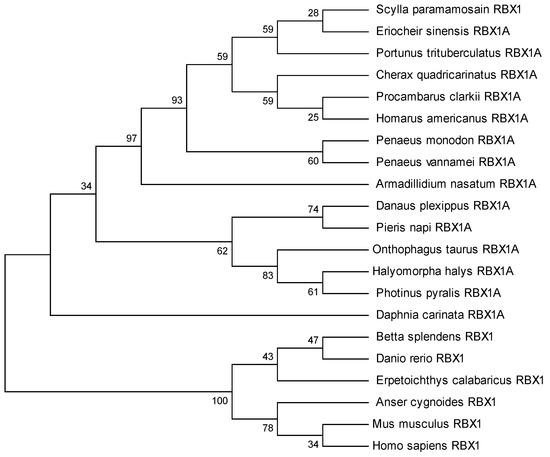

The amino acid sequence comparison of RBX1 revealed the highest homology with Portunus trituberculatus and E. sinensis (100%), followed by Homarus americanus (99.11%), Penaeus vannamei (97.32%), and P. monodon (97.30%) (Figure 2). There were three conserved motifs (motif 1, motif 2, and motif 3) and three typical conserved elements (motif 4, motif 5, and motif 6) in RBX1 protein, among twelve species, in which motif 1 and motif 2 were RING finger domains (Figure 3). The phylogenetic tree analysis showed that S. paramamosain is most closely genetically related to P. trituberculatus and E. sinensis. The crustaceans clustered together on one branch, and insects generally formed another branch, while fish and mammals were grouped together on a separate branch (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequence of Sp-RBX1 protein with other species. Note: The shadowed regions represent homology of amino acids: black: similarity = 100%, yellow: similarity > 75%, blue: similarity > 33%.

Figure 3.

Comparison of conserved motifs between Sp-RBX1 protein and other species. Note: motif 1 (red), motif 2 (blue), and motif 3 (light green) were conserved motifs of RBX1; motif 4 (purple), motif 5 (orange), and motif 6 (dark green) were typical conserved elements.

Figure 4.

The phylogenetic tree of RBX1 amino acid sequences from multiple species according to neighbor-joining method.

2.3. Analysis of Expression Pattern of RBX1 Gene In Vivo

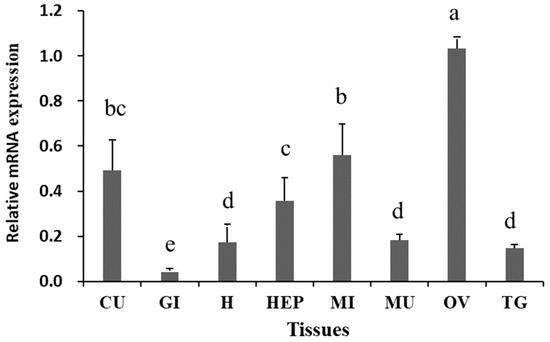

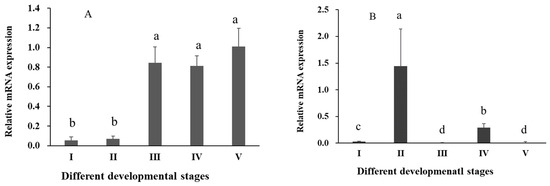

The results of RT-qPCR revealed significant differential expression of Sp-RBX1 in eight tissues, with the highest expression observed in the ovary, followed by intestine, cuticle, and hepatopancreas, while the lowest expression level was detected in the gill (p < 0.05) (Figure 5). During the ovarian development of S. paramamosain, the expression of Sp-RBX1 in the ovary was relatively low in stages I and II, and significantly increased from stage III to V in the ovary (p < 0.05) (Figure 6A). The expression of Sp-RBX1 in the hepatopancreas peaked at stage II, but dropped significantly from stage III onward, remaining low through stage V (p < 0.05) (Figure 6B).

Figure 5.

Expression analysis of Sp-RBX1 in different tissues. Note: CU: cuticle; H: heart; MI: intestine; MU: muscle; HEP: hepatopancreas; GI: gill; TG: thoracic ganglion; OV: ovary. Different letters on the graph indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

Figure 6.

Expression of Sp-RBX1 during different development stages in ovaries and hepatopancreas. Note: (A), expression in ovary, I–V: five stages of ovarian development; (B), expression in hepatopancreas, I–V: five stages of hepatopancreatic development. Different letters on the graph indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

2.4. Analysis of Effects of FSH and E2 on Expression Patterns of Sp-RBX1 In Vitro

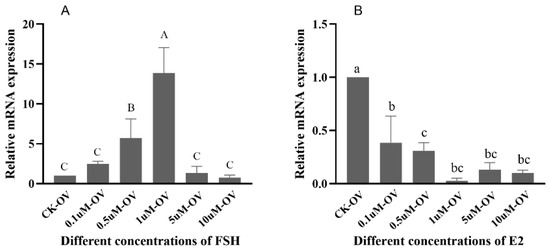

The expressions of Sp-RBX1 in the ovarian tissue increased gradually with FSH concentrations from 0.1 to 1 µM, reaching its peak at 1 µM. However, its expression sharply decreased at concentrations of 5 and 10 µM (p < 0.05) (Figure 7A). Compared to the control group, the expressions of Sp-RBX1 were significantly inhibited under E2 concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 10 µM (p < 0.05) (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

The effects of different FSH and E2 concentrations on Sp-RBX1 in ovaries in vitro. Note: (A), the effect of FSH; (B), the effect of E2. Different case letters indicate significant differences; the capitals indicate FSH, and lowercases indicate E2 (p < 0.05).

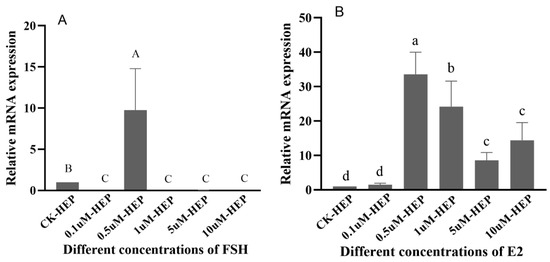

The regulatory effect of FSH on Sp-RBX1 in the hepatopancreatic tissue was up-regulated at the concentration of 0.5 µM. However, other concentrations of FSH had an inhibitory effect on the expression of Sp-RBX1 (p < 0.05) (Figure 8A). Sp-RBX1 expression showed a notable up-regulation under the incubation of E2, with the concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 10 µM (p < 0.05), reaching the highest level at the concentration of 0.5 µM (p < 0.05) (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

The effects of different FSH and E2 concentrations on Sp-RBX1 in hepatopancreas in vitro. Note: (A), the effect of FSH; (B), the effect of E2. Different case letters indicate significant differences; the capitals indicate FSH, and lowercases indicate E2 (p < 0.05).

3. Discussion

RBX1 homologous proteins are evolutionarily conserved from plants to mammals [21]. In this study, we obtained the cDNA sequence of RBX1 from the mud crab. The predicted Sp-RBX1 protein contains a C-terminal modified RING-H2 finger domain, crucial for its ligase activity [22]. This domain includes two zinc binding sites and a Cullin binding site, similar to most RBX1 superfamily members [23]. This conserved domain is homologous to RBX protein families, which indicates that Sp-RBX1 is a member of the RBX superfamily. The evolutionary tree of RBX1 proteins indicated a high evolutionary homology between S. paramamosain and other crabs, which was consistent with previous reports [24]. The evolutionary tree analysis of RBX1 conformed to the biological classification and evolutionary characteristics.

The function of a gene is closely related to specific tissue distribution [25]. In this study, it was found that Sp-RBX1 was expressed in multiple tissues of the mud crab, with the highest level observed in the ovary, which was similar to the expression pattern in the gonad of E. sinensis [18]. Thus, we supposed that RBX1 might potentially be involved in regulating the growth, development, and reproductive processes of crustaceans, particularly in gonadal development. However, further study is required to determine the specific underlying mechanisms.

RBX1 protein plays a key role in oogenesis and ovarian maturation [26]. In ovaries, the expression of Sp-RBX1 gene was low in stage I and stage II, and significantly increased from stage III to stage V. The elevated expression of RBX1 during the middle and late stages of ovarian development might be due to its participation in the ovarian development process [27]. During ovarian development, the hepatopancreas synthesizes and accumulates lipids, then transports them into the ovary to provide the energy and material basis for vitellogenesis and oocyte maturation [28]. In the hepatopancreas of S. paramamosain, the level of total lipid at stage II was significantly greater than those at stages III, IV, and V [29]. The highest expression of Sp-RBX1 in the hepatopancreas at stage II might be correlated with the high energy requirements of subsequent ovum formation and fat accumulation in the ovary.

FSH stimulates follicle growth and oocyte maturation, playing a critical role in reproductive physiology. In this study, FSH up-regulated Sp-RBX1 expression in a concentration-dependent manner, within the range of 0.1 µM to 1 µM, and the most significant effect was observed at 1 µM in ovaries. However, higher FSH concentrations suppressed Sp-RBX1 expression, suggesting a biphasic regulatory role. This indicated that RBX1 might be involved in oocyte maturation through FSH-mediated hormonal regulation, as supported by previous studies [30,31]. Beyond its role in reproductive regulation, FSH has been shown to influence lipid metabolism [32]. The expression of Sp-RBX1 was obviously up-regulated under the concentration of 0.5 µM of FSH. This function might be mediated through its interaction with Sp-RBX1 in the hepatopancreas, which served as the primary lipid storage organ in S. paramamosain. These findings suggest that FSH, along with other reproductive hormones, might play a dual role in both reproductive and metabolic regulation in crustaceans.

E2 is an important sex steroid hormone involved in regulation of animal lipid metabolism [33]. The expression of Sp-RBX1 was up-regulated under the different concentrations of E2, ranging from 0.5 to 10µM, in the hepatopancreas. It was obviously up-regulated under the concentration of 0.5 µM of E2, which suggested the concentration of 0.5 µM might be the optimal concentration to exert biological effects. These findings indicated that hormonal regulation influenced the expression of Sp-RBX1 and might participate in the fat metabolism processes of S. paramamosain. In previous studies, the positive effects of E2 on ovarian development were not detected in some crustaceans at a particular ovarian stage [34,35]. The expression of Sp-RBX1 was low under E2 treatment in ovarian tissue. The possible reason is that E2 might promote oocyte maturation through nutrient provision to the ovaries, mediated by the hepatopancreas, rather than acting directly on ovarian cells.

In conclusion, the cDNA sequence of Sp-RBX1 was obtained, and its sequence characteristics and expression patterns in different tissues and different stages of ovarian development were analyzed. We proposed a preliminary speculation on the regulatory mechanism of Sp-RBX1 in the ovarian development and maturation of S. paramamosain. In addition, through culture experiments in vitro, we demonstrated that Sp-RBX1 might be regulated by FSH and E2 to influence oocyte development and ovarian maturation in S. paramamosain. These findings could offer valuable insights for further research on ovarian development in S. paramamosain.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethics Statement

All animal experiments in this study were conducted in accordance with the relevant national and international guidelines. Our project was approved by the East China Sea Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences, 20250410-1, on 10 April 2025. Our study did not involve endangered or protected species.

4.2. Collection of Experimental Samples

The healthy female mud crabs were selected from the Zhejiang Ninghai Research Center, East China Sea Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences. Ovarian and hepatopancreatic tissues from stage I to stage V (3 individuals per stage) were collected to analyze the expression patterns. In addition, 6 tissues, including thoracic ganglion, epidermis, heart, intestine, gills, and muscles, from adult crabs at stage III were sampled (3 replicates) to analyze tissue-specific expression. Each tissue was placed in RNA keeper tissue stabilizer and stored at −70 °C.

4.3. RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

Total RNA was extracted using UNIQ-10 column Trizol extraction kit (TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration and quality of RNA were determined using a NanoOne spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Shanghai, China). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using EasyScript One-Step gDNA Removal and cDNA Synthesis SuperMix reverse transcription kit (TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and then stored at 4 °C.

4.4. Validation of RBX1 Sequence

The cDNA sequence of RBX1, designated Sp-RBX1, was identified from the full-length transcriptome library of S. paramamosain in our laboratory. The primers for sequence verification were designed by the software Primer Premier 5.0 (Table 1). The PCR reaction was performed in a 25 μL volume consisting of 2× Power Taq PCR MasterMix, 1 μL of each primer (10 μM), 1 μL of template cDNA, and ddH2O. The PCR reactions were carried out under the following conditions: 5 min pre-denaturation at 94 °C; 42 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 45 s at 52 °C, and 45 s at 72 °C; and a final extension at 72 °C for 7 min. The PCR amplification products were checked with 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and sent to Shanghai Jieli Biological Limited Company (Shanghai, China) for sequencing.

Table 1.

Information on primer sequences.

4.5. Bioinformatics Analysis of Sp-RBX1 Sequence

The open reading frame (ORF) of the Sp-RBX1 sequences was identified using NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder/ accessed on 29 December 2024). The ExPASy portal (https://www.expasy.org/ accessed on 29 December 2024) was used to predict the protein molecular weight, molecular structure, and isoelectric point. The homologous RBX1 amino acid sequences were downloaded from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ accessed on 29 December 2024). These species and accession numbers were listed in Table 2. The multiple sequence comparison analysis was carried out by DNAMAN V6 software to determine the similarity of RBX1 amino acid sequences among different species. A phylogenetic tree was constructed, using the above sequences, with the maximum likelihood method (ML) in the MEGA 11 software. The bootstrap value was set to 1000, and the Jones–Taylor–Tornton (JTT) model was used.

Table 2.

Species names and accession numbers used in this study.

4.6. Expression Profile of RBX1 in Various Tissues and Developmental Stages

Real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was performed to determine the relative expression levels of Sp-RBX1 in different tissues, and its temporal expression profile across various stages of ovarian and hepatopancreatic development. Primers for the RT-qPCR reaction of Sp-RBX1 were designed using Primer Premier 5.0. The 18S rRNA was used as the internal reference gene [36] (Table 1). The RT-qPCR reaction was performed in a total volume of 20 μL, consisting of 2 μL of template cDNA, 10 μL of SYBR Primix Ex Taq, 0.8 μL of each primer (10 μM), and 6.4 μL of ddH2O. The RT-qPCR reactions were performed under the following conditions: 30 s initial denaturation at 94 °C; 40 cycles of 5 s at 94 °C, and 30 s at 60 °C. The relative expression of Sp-RBX1 in the different samples was calculated using the 2−∆∆Ct method.

4.7. Analysis of Expression Patterns of Sp-RBX1 Regulated by FSH and E2

FSH was completely dissolved in 10 mM PBS (pH 7.4) containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), then mixed and diluted to the working solutions, with final concentrations of 10 µM, 50 µM, 100 µM, 500 µM, and 1000 µM. The E2 hormone was completely dissolved in 1% DMSO and diluted to the same final concentrations as FSH. Tissues, including ovarian and hepatopancreatic tissues, were collected from 3 healthy female mud crabs (stage III). The tissues were cut into 25 mg pieces with sterilized scissors, rinsed with sterile normal saline 4 times, and placed into sterile 24-well Petri dishes (Corning, New York, NY, USA). They were then cultured on a shaker at 25 °C. A 20 µL hormone working solution was added to 1980 µL of DMEM high-glucose medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to achieve final concentrations of 0.1 µM, 0.5 µM, 1 µM, 5 µM, and 10 µM for each hormone. The control group was treated with 100 µM of PBS for FSH group and 0.01% of DMSO for E2 group. After 6 h of culture on the shaker, the tissues were stored in −80 °C refrigerator until RT-qPCR. All experiments were independently repeated three times.

4.8. Data Analysis of RT-qPCR

As for the results of RT-qPCR, all data were calculated to derive the mean and standard error (SE). Homogeneity of variances was performed by Levene’s test, followed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Scheffé’s post hoc analysis. Differences were considered significant at p < 0.05.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we successfully identified and characterized the RBX1 gene (Sp-RBX1) from the transcriptome of S. paramamosain. The significant upregulation of Sp-RBX1 in the ovary during stages III to V strongly suggested its crucial role in oocyte maturation. Furthermore, the distinct expression patterns observed in the hepatopancreas indicated potential additional functions in metabolic processes related to energy storage for vitellogenesis. The differential regulatory effects of FSH and E2 on Sp-RBX1 expression highlighted a complex hormonal regulatory mechanism, likely tied to its role in the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway governing oocyte maturation. In a word, these findings provided foundational insights into the molecular mechanisms regulating ovarian development in crustaceans and proposed Sp-RBX1 as a valuable candidate for further research into reproductive endocrinology and maturation in S. paramamosain.

Author Contributions

F.Z., T.H. and C.M. conceptualized the experiment. T.H., Y.R., W.W., M.Z., Z.L., K.M., Y.F., W.C. and L.M. collected the specimens. F.Z. and T.H. performed the experiment and analyzed the data. F.Z. and T.H. wrote the manuscript. F.Z. and C.M. revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (2024YFD2401703), the Special Scientific Research Funds for Central Non-profit Institutes, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences (2024JC0103, 2023TD31), the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-48), and the National Infrastructure of Fishery Germplasm Resources.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the East China Sea Fisheries Research Institute (20250410-1, 10 April 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, H.; Cheung, K.C.; Chu, K.H. Cell structure and seasonal changes of the androgenic gland of the mud crab Scylla paramamosain (Decapoda: Portunidae). Zool. Stud. 2008, 47, 720–732. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Fisheries and Fishery Management. China Fishery Statistical Year Book; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2024; pp. 22–38.

- Islam, M.S.; Kodama, K.; Kurokora, H. Ovarian development of the mud crab Scylla paramamosain in a tropical mangrove swamps, Thailand. J. Sci. Res. 2010, 2, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emori, C.; Sugiura, K. Role of oocyte-derived paracrine factors in follicular development. Anim. Sci. J. 2014, 85, 627–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, J.; Orisaka, M.; Wang, H.; Orisaka, S.; Thompson, W.; Zhu, C.; Kotsuji, F.; Tsang, B.K. Gonadotropin and intra-ovarian signals regulating follicle development and atresia: The delicate balance between life and death. Front. Biosci. J. Virtual Libr. 2007, 12, 3628–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoevers, E.J.; Kidson, A.; Verheijden, J.H.M.; Bevers, M.M. Effect of follicle-stimulating hormone on nuclear and cytoplasmic maturation of sow oocytes in vitro. Theriogenology 2003, 59, 2017–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.S.; Seo, Y.I.; Yin, X.J.; Cho, S.G.; Lee, S.S.; Kim, N.H.; Cho, S.K.; Kong, I.K. Effect of follicle stimulation hormone and luteinizing hormone on cumulus cell expansion and in vitro nuclear maturation of canine oocytes. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2007, 42, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Ray, A.K. 17 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity of ovary and hepatopancreas of freshwater prawn, Macrobrachium rosenbergii: Relation to ovarian condition and estrogen treatment. Gen. Comp. Endocr. 1993, 89, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksura, H.; Akon, N.; Islam, M.N.; Akter, I.; Modak, A.K.; Khatun, A.; Alam, M.H.; Hashem, M.A.; Amin, M.R.; Moniruzzaman, M. Effects of estradiol on in vitro maturation of buffalo and goat oocytes. Reprod. Med. Biol. 2021, 20, 62–70. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, W.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Yang, M. RING box protein-1 promotes the metastasis of cervical cancer through regulating matrix metalloproteinases via PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. J. Mol. Histol. 2025, 56, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, N.; Schulman, B.A.; Song, L.; Miller, J.J.; Jeffrey, P.D.; Wang, P.; Chu, C.; Koepp, D.M.; Elledge, S.J.; Pagano, M.; et al. Structure of the Cul1–Rbx1–Skp1–F boxSkp2 SCF ubiquitin ligase complex. Nature 2002, 416, 703–709. [Google Scholar]

- Ping, J.G.; Wang, F.; Pu, J.X.; Hou, P.F.; Chen, Y.S.; Bai, J.; Zheng, J.N. The expression of Cullin1 is increased in renal cell carcinoma and promotes cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. Tumor Biol. 2016, 37, 12823–12831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, E.; Zhou, Y.; He, S.; Tang, J.; He, Y.; Zhu, M.; Cheng, C.; Wang, Y. RING box protein-1 (RBX1), a key component of SCF E3 ligase, induced multiple myeloma cell drug-resistance though suppressing p27. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2023, 24, 2231670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Ni, X.; Guo, Y.; Guo, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Huo, R.; Sha, J. Proteomic-based identification of maternal proteins in mature mouse oocytes. BMC Genom. 2009, 10, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasagawa, Y.; Urano, T.; Kohara, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Higashitani, A. Caenorhabditis elegans RBX1 is essential for meiosis, mitotic chromosomal condensation and segregation, and cytokinesis. Genes Cells 2003, 8, 857–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamura, T.; Koepp, D.M.; Conrad, M.N.; Skowyra, D.; Moreland, R.J.; Iliopoulos, O.; Lane, W.S.; Kaelin, W.G., Jr.; Elledge, S.J.; Conaway, R.C.; et al. Rbx1, a component of the VHL tumor suppressor complex and SCF ubiquitin ligase. Science 1999, 284, 657–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Sun, Y. RBX1/ROC1-SCF E3 ubiquitin ligase is required for mouse embryogenesis and cancer cell survival. Cell Div. 2009, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.S.; Li, X.J.; Yang, L.; Li, W.W.; Wang, Q. Expression pattern and functional analysis of the two RING box protein RBX in spermatogenesis of Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis. Gene 2018, 668, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvari, P.; Rasouli, S.J.; Allanki, S.; Stone, O.A.; Sokol, A.M.; Graumann, J.; Stainier, D.Y. The E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase Rbx1 regulates cardiac wall morphogenesis in zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 2021, 480, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Wu, X.; Wang, L. Identification and functional characterization of an Rbx1 in an invertebrate Haliotis diversicolor supertexta. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2011, 35, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Hu, X.; Chen, X.; Wu, L.; Chen, Y. Identification and characterization of an E3 ubiquitin ligase Rbx1 in maize (Zea mays L.). Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2014, 116, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, D.; Sun, Y. Small RING finger proteins RBX1 and RBX2 of SCF E3 ubiquitin ligases: The role in cancer and as cancer targets. Genes Cancer 2010, 1, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorick, K.L.; Tsai, Y.C.; Yang, Y.; Weissman, A.M. RING fingers and relatives: Determinators of protein fate. Protein Degrad. Ubiquitin Chem. Life 2005, 1, 44–101. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Chen, P.; Liu, P.; Gao, B.; Wang, Q.; Li, J. Molecular characterization and expression analysis of extracellular copper–zinc superoxide dismutase gene from swimming crab Portunus trituberculatus. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2011, 38, 2107–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Movahedi, S.; Van de Peer, Y.; Vandepoele, K. Comparative network analysis reveals that tissue specificity and gene function are important factors influencing the mode of expression evolution in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 1316–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinterová, V.; Kaňka, J.; Bartková, A.; Toralová, T. SCF Ligases and their functions in Oogenesis and embryogenesis—Summary of the most important findings throughout the animal Kingdom. Cells 2022, 11, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monshizadeh, K.; Tajamolian, M.; Anbari, F.; Mehrjardi, M.Y.V.; Kalantar, S.M.; Dehghani, M. The association of RBX1 and BAMBI gene expression with oocyte maturation in PCOS women. BMC Med. Genom. 2023, 17, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantikitti, C.; Kaonoona, R.; Pongmaneerat, J. Fatty acid profiles and carotenoids accumulation in hepatopancreas and ovary of wild female mud crab (Scylla paramamosain, Estampador, 1949). Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 2015, 37, 609–616. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.W.; Tian, Y. The F-box gene Ppa promotes lipid storage in Drosophila. Hereditas 2021, 43, 615–622. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Findlay, J.K.; Drummond, A.E. Regulation of the FSH receptor in the ovary. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 1999, 10, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmlinger, M.; Kühnel, W.; Ranke, M. Reference Ranges for Serum Concentrations of Lutropin (LH), Follitropin (FSH), Estradiol (E2), Prolactin, Progesterone, Sex Hormone-Binding Globulin (SHBG), Dehydroepiandrosterone Sulfate (DHEAS), Cortisol and Ferritin in Neonates, Children and Young Adults. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2002, 40, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Zhao, G.; Liu, R.; Zheng, M.; Chen, J.; Wen, J. FSH stimulates lipid biosynthesis in chicken adipose tissue by upregulating the expression of its receptor FSHR. J. Lipid Res. 2012, 53, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, L.; Cheng, Y.; Gong, J.; Zeng, C.; Wu, X. Effect of estradiol on hepatopancreatic lipid metabolism in the swimming crab, Portunus trituberculatus. Gen. Comp. Endocr. 2019, 280, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koskela, R.; Greenwood, J.; Rothlisberg, P. The influence of prostaglandin E2, and the steroid hormones, 17α-hydroxyprogesterone and 17β-estradiol on moulting and ovarian development in the tiger prawn, Penaeus esculentus, Haswell, 1879 (Crustacea: Decapoda). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Physiol. 1992, 101, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Pan, J.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Gong, J.; Wu, X. Effect of estradiol on vitellogenesis and oocyte development of female swimming crab, Portunus trituberculatus. Aquaculture 2018, 486, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Jiang, K.; Song, W.; Ma, C.; Wang, J.; Meng, Y.; Wei, H.; Chen, K.; Qiao, Z.; Zhang, F.; et al. Two transcripts of HMG-CoA reductase related with developmental regulation from Scylla paramamosain: Evidences from cDNA cloning and expression analysis. IUBMB Life 2015, 67, 954–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.