Comparison of Creatinine-, Cystatin C-, and Combined Creatinine–Cystatin C-Based Equations for Estimating Glomerular Filtration Rate: A Real-World Analysis in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Agreement and Discrepancy Among eGFR Equations

2.2. Subgroup Analysis of Discrepant Cases

- In all 16 CKD cases, the combined equation most closely reflected the clinical diagnosis, based on nephrology notes, comorbidities, and the presence of albuminuria.

- The creatinine-based equation frequently overestimated renal function, especially in older adults or patients with reduced muscle mass.

- The cystatin C-based equation often showed lower GFR values, particularly in patients with inflammatory states or obesity, aligning with early CKD detection but potentially affected by non-GFR factors.

2.3. Acute and Infection-Related Cases

- Elevated Scr, likely due to tubular secretion inhibition, leading to underestimation of GFR by the creatinine-based equation.

- Elevated ScysC, possibly reflecting inflammation.

- The combined equation provided a more balanced estimate, consistent with the overall clinical condition.

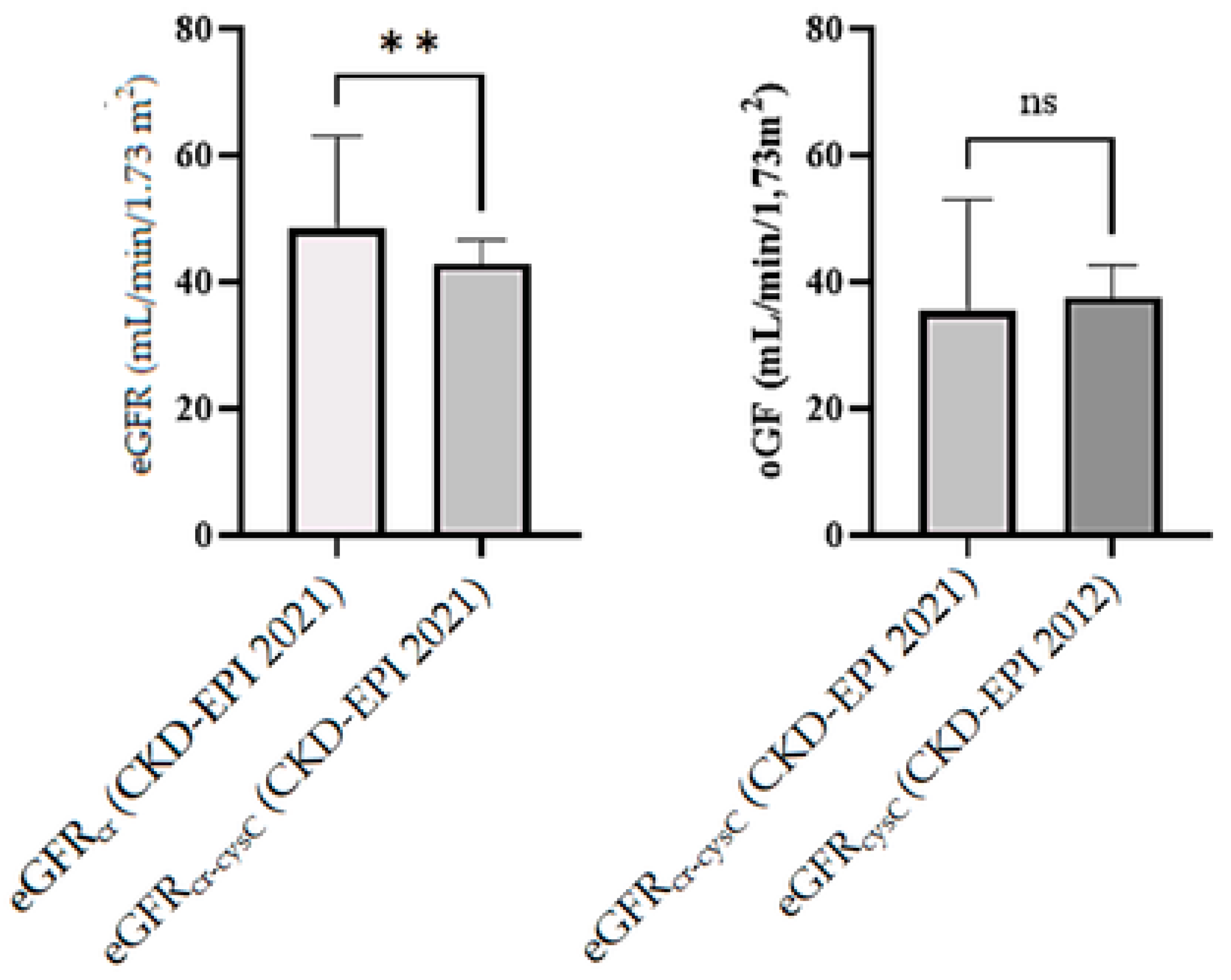

2.4. Statistical Comparison of Equations

- Mean eGFR values were significantly different across equations (p < 0.05).

- Two- tailed paired t-test confirmed statistically significant differences between eGFRcr and eGFRcr-cysC (p = 0.006).

- Wilcoxon tests did not confirm statistically significant differences between eGFRcysC and eGFRcr-cysC (p = 0.0553) and between eGFRcr and eGFRcr-cysC (p = 0.0285).

2.5. Clinical Relevance

- Therapeutic decision-making (e.g., drug dosing);

- Nephrology referral timing;

- Risk stratification.

3. Discussion

3.1. Clinical Consequences of Equation Selection

3.2. Importance of Patient-Specific Context

3.3. Advantages of the Combined Equation

3.4. Limitations

3.5. Clinical Implications

- Use eGFRcr as the standard screening tool in stable adults without known confounders.

- Consider eGFRcr-cysC when higher precision is needed, or when eGFRcr may be unreliable (e.g., extremes of age, body size, muscle mass).

- Use eGFRcysC in situations of suspected AKI or early-stage CKD where creatinine remains within normal range.

- In cases of major discrepancy between equations (>15 mL/min/1.73 m2), eGFRcr-cysC should be prioritized or validated with measured GFR if available.

3.6. Toward a Tiered Diagnostic Strategy for eGFR Use

3.7. Practical Integration into Laboratory and Clinical Workflows

- Automatic reflex testing of cystatin C when eGFRcr is borderline or when requested by clinicians;

- Including interpretative comments in reports indicating when cystatin C-based or combined eGFR may be more appropriate;

- Education and collaboration with nephrology and internal medicine teams on the clinical interpretation of eGFR variability.

3.8. Alignment with Guidelines and Future Directions

4. Materials and Methods

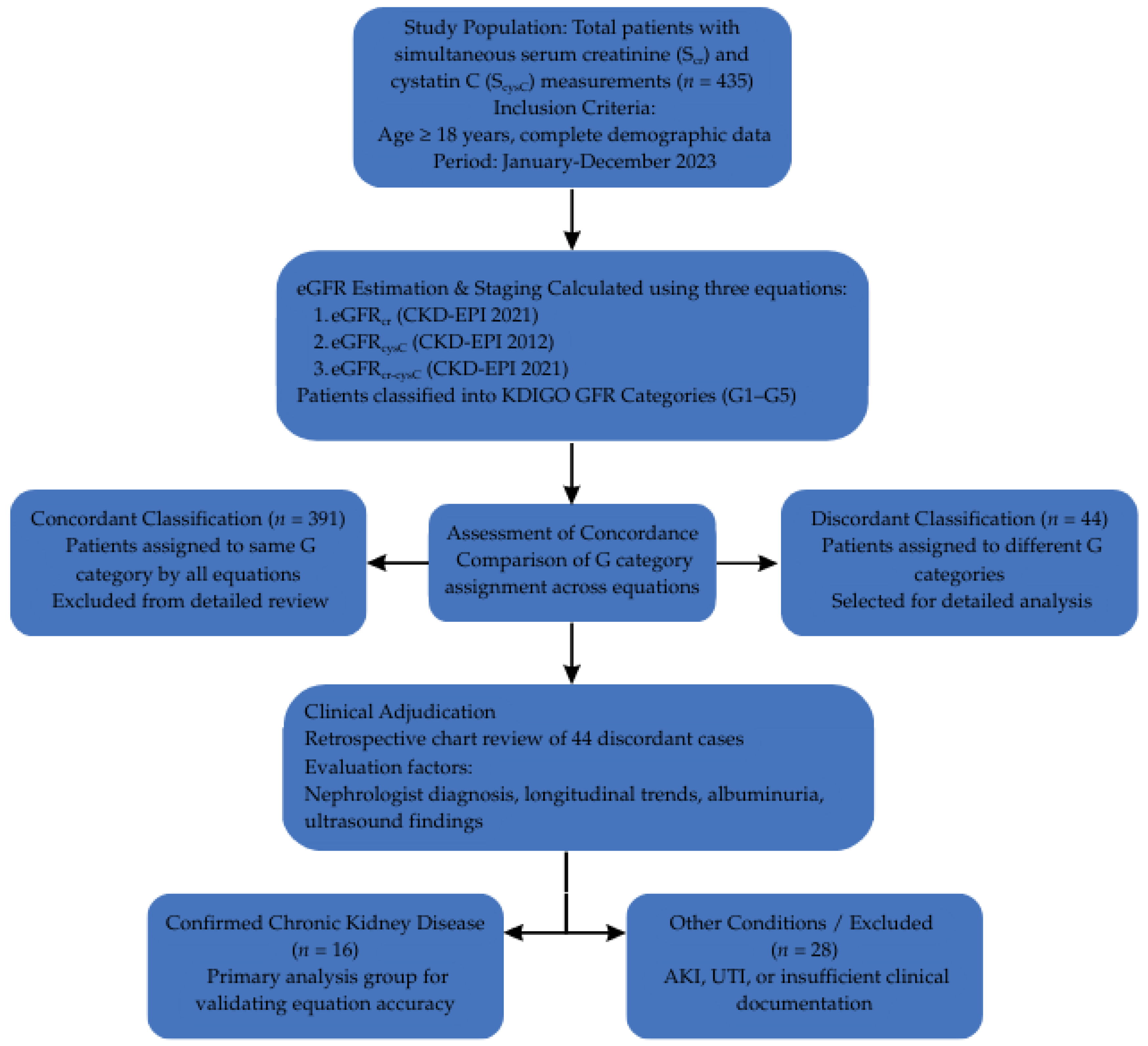

4.1. Study Design and Population

4.2. eGFR Equations

- CKD-EPI 2021 Creatinine Equation (eGFRcr): Uses Scr, age, and sex. It includes separate constants ($\kappa$ and $\alpha$) for males and females to account for differences in the muscle mass generation of creatinine.

- CKD-EPI 2012 Cystatin C Equation (eGFRcysC): Uses ScysC, age, and sex. Unlike creatinine, this equation does not require race adjustments but relies on the constant generation of cystatin C by nucleated cells.

- CKD-EPI 2021 Combined Equation (eGFRcr-cysC): Incorporates both markers (Scr and ScysC) along with age and sex to mitigate the non-GFR determinants affecting each marker individually.

4.3. eGFR Calculation and GFR Staging

- Creatinine-based (CKD-EPI 2021, eGFRcr);

- Cystatin C-based (CKD-EPI 2012, eGFRcysC);

- Combined creatinine + cystatin C (CKD-EPI 2021, eGFRcr-cysC).

4.4. Selection of Clinically Relevant Subset

4.5. Laboratory Measurements

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| eGFR | Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| mGFR | Measured estimated glomerular filtration rate |

| eGFRcr | Estimated glomerular filtration rate creatinine |

| eGFRcysC | Estimated glomerular filtration rate, cystatin C |

| eGFRcr-cysC | Estimated glomerular filtration rate, creatinine–cystatin C |

| CKD | Chronic kidney disease |

| GFR | Glomerular filtration rate |

| AKI | acute kidney injury |

| UTI | Urinary tract infections |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| KDIGO | Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes |

| Scr | Serum creatinine |

| IDMS | Isotope dilution mass spectrometry |

| ScysC | Serum cystatin C |

| PENIA | Particle-enhanced immunonephelometric assay |

References

- Argyropoulos, C.P.; Chen, S.S.; Ng, Y.H.; Roumelioti, M.E.; Shaffi, K.; Singh, P.P.; Tzamaloukas, A.H. Rediscovering Beta-2 Microglobulin As a Biomarker across the Spectrum of Kidney Diseases. Front. Med. 2017, 4, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komenda, P.; Ferguson, T.W.; Macdonald, K.; Rigatto, C.; Koolage, C.; Sood, M.M.; Tangri, N. Cost-effectiveness of primary screening for CKD: A systematic review. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2014, 63, 789–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Kidney Foundation. Frequently Asked Questions About GFR Estimates; National Kidney Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Adingwupu, O.M.; Barbosa, E.R.; Palevsky, P.M.; Vassalotti, J.A.; Levey, A.S.; Inker, L.A. Cystatin C as a GFR Estimation Marker in Acute and Chronic Illness: A Systematic Review. Kidney Med. 2023, 5, 100727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, C.C.; Marzinke, M.A.; Ahmed, S.B.; Collister, D.; Colón-Franco, J.M.; Hoenig, M.P.; Lorey, T.; Palevsky, P.M.; Palmer, O.P.; Rosas, S.E.; et al. AACC/NKF Guidance Document on Improving Equity in Chronic Kidney Disease Care. J. Appl. Lab. Med. 2023, 8, 789–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, L.A.; Levey, A.S. Measured GFR as a confirmatory test for estimated GFR. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 20, 2305–2313, Erratum in J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karger, A.B.; Inker, L.A.; Coresh, J.; Levey, A.S.; Eckfeldt, J.H. Novel Filtration Markers for GFR Estimation. EJIFCC 2017, 28, 277–288. [Google Scholar]

- Lindič, J.; Kovač, D.; Kveder, R.; Malovrh, M.; Pajek, J.; Aleš Rigler, A.; Škoberne, A. Bolezni Ledvic; Slovensko Zdravniško Društvo–Slovensko Nefrološko Društvo: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2014; pp. 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ebert, N.; Schaeffner, E. New biomarkers for estimating glomerular filtration rate. J. Lab. Precis. Med. 2018, 3, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, M.A.; Waikar, S.S. Established and emerging markers of kidney function. Clin. Chem. 2012, 58, 680–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Foster, M.C.; Tighiouart, H.; Anderson, A.H.; Beck, G.J.; Contreras, G.; Coresh, J.; Eckfeldt, J.H.; Feldman, H.I.; Greene, T.; et al. Non-GFR Determinants of Low-Molecular-Weight Serum Protein Filtration Markers in CKD. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2016, 68, 892–900, Erratum in Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2024, 83, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, M.C.; Levey, A.S.; Inker, L.A.; Shafi, T.; Fan, L.; Gudnason, V.; Katz, R.; Mitchell, G.F.; Okparavero, A.; Palsson, R.; et al. Non-GFR Determinants of Low-Molecular-Weight Serum Protein Filtration Markers in the Elderly: AGES-Kidney and MESA-Kidney. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2017, 70, 406–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, N.; Koep, C.; Schwarz, K.; Martus, P.; Mielke, N.; Bartel, J.; Kuhlmann, M.; Gaedeke, J.; Toelle, M.; van der Giet, M.; et al. Beta Trace Protein does not outperform Creatinine and Cystatin C in estimating Glomerular Filtration Rate in Older Adults. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12656, Erratum in Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 7396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, L.A.; Schmid, C.H.; Greene, T.; Li, L.; Beck, G.J.; Joffe, M.M.; Froissart, M.; Kusek, J.W.; Zhang, Y.L.; Coresh, J.; et al. Factors other than glomerular filtration rate affect serum cystatin C levels. Kidney Int. 2009, 75, 652–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanga, Z.; Nock, S.; Medina-Escobar, P.; Nydegger, U.E.; Risch, M.; Risch, L. Factors other than the glomerular filtration rate that determine the serum beta-2-microglobulin level. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e72073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwisa, S.; Soliman, N.; Faraj, M.; Salem, G.; Alosta, A.; Alshoshan, S.; Alfituri, R.F.; Aziez, Z.A. Association Between TSH and Creatinine Levels in Patients with Hypothyroidism. World Acad. Sci. J. 2024, 6, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Lu, B.; Sheng, X.; Jin, N. Cystatin C in Prediction of Acute Kidney Injury: A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2011, 58, 356–365, Erratum in Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2012, 59, 590–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hojs, R.; Bevc, S.; Ekart, R.; Gorenjak, M.; Puklavec, L. Serum cystatin C-based equation compared to serum creatinine-based equations for estimation of glomerular filtration rate in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin. Nephrol. 2008, 70, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inker, L.A.; Schmid, C.H.; Tighiouart, H.; Eckfeldt, J.H.; Feldman, H.I.; Greene, T.; Kusek, J.W.; Manzi, J.; Van Lente, F.; Zhang, Y.L.; et al. Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 20–29, Erratum in N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 681. Erratum in N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024, 105, S117–S314. [CrossRef]

- Appel, L.J.; Grams, M.; Woodward, M.; Harris, K.; Arima, H.; Chalmers, J.; Yatsuya, H.; Tamakoshi, K.; Li, Y.; Coresh, J.; et al. Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate, Albuminuria, and Adverse Outcomes: An Individual-Participant Data Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2023, 330, 1266–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lameire, N.H.; Levin, A.; Kellum, J.A.; Cheung, M.; Jadoul, M.; Winkelmayer, W.C.; Stevens, P.E.; Caskey, F.J.; Farmer, C.K.; Fuentes, A.F.; et al. Harmonizing acute and chronic kidney disease definition and classification: Report of a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Consensus Conference. Kidney Int. 2021, 100, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, E.L.; Verhave, J.C.; Spiegelman, D.; Hillege, H.L.; de Zeeuw, D.; Curhan, G.C.; de Jong, P.E. Factors influencing serum cystatin C levels other than renal function and the impact on renal function measurement. Kidney Int. 2004, 65, 1416–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shlipak, M.G.; Matsushita, K.; Ärnlöv, J.; Inker, L.A.; Katz, R.; Polkinghorne, K.R.; Rothenbacher, D.; Sarnak, M.J.; Astor, B.C.; Coresh, J.; et al. Cystatin C versus Creatinine in Determining Risk Based on Kidney Function. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 932–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inker, L.A.; Levey, A.S.; Coresh, J. Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate from a Panel of Filtration Markers-Hope for Increased Accuracy Beyond Measured Glomerular Filtration Rate? Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2018, 25, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United States Renal Data System (USRDS). USRDS 2015 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States; NIH/NIDDK: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2015; pp. 1–300. [Google Scholar]

- Go, A.S.; Chertow, G.M.; Fan, D.; McCulloch, C.E.; Hsu, C.Y. Chronic Kidney Disease and the Risks of Death, Cardiovascular Events, and Hospitalization. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 1296–1305, Erratum in N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 18, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chronic Kidney Disease: Assessment and Management, No. 203; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London, UK, 2021.

- ISO 15189:2022; Medical Laboratories—Requirements for Quality and Competence (English Version). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

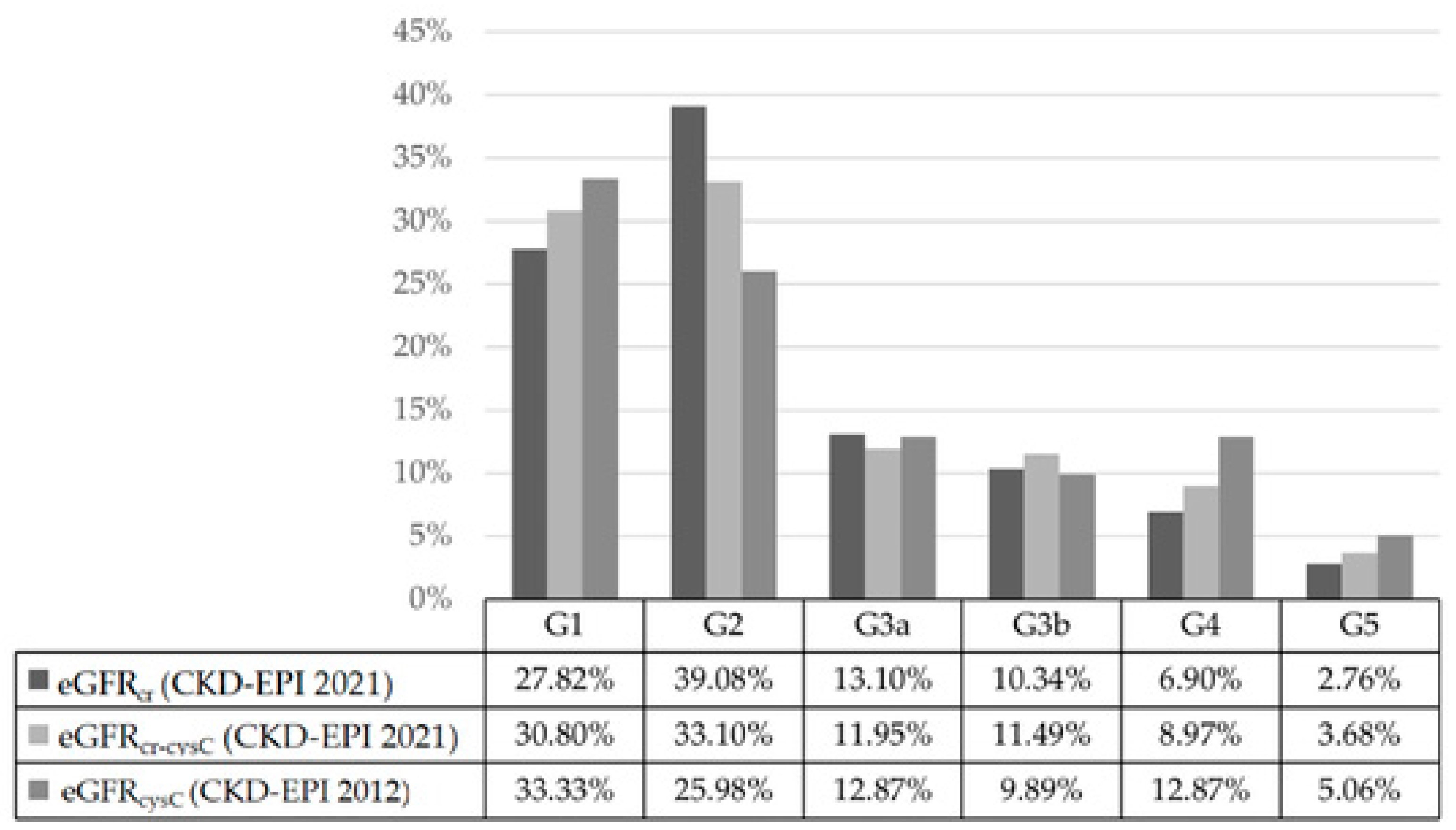

| Equation | G1 | G2 | G3a | G3b | G4 | G5 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eGFRcr (CDK-EPI 2021) | 121 | 170 | 57 | 45 | 30 | 12 | 435 |

| eGFRcr-cysC (CDK-EPI 2021) | 134 | 144 | 52 | 50 | 39 | 16 | 435 |

| eGFRcysC (CDK-EPI 2012) | 145 | 113 | 56 | 43 | 56 | 22 | 435 |

| Number of Patients | Sex–Female (%) | Sex–Male (%) | Age–Female (Mean) | Age–Male (Mean) | Age (Mean) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total: | 16 | 43.75 | 56.25 | 72 | 61 | 67 |

| CKD Stage Distribution: | CKD Stage 2 (%) | CKD Stage 3 (%) | CKD Stage 4 (%) | CKD Stage 5 (%) | CKD Unspecified (%) | |

| 6.25 | 56.25 | 25.00 | 6.25 | 6.25 | ||

| Equation Concordance: | Best Fit: eGFRcr (%) | Best Fit: eGFRcr-cysC (%) | Best Fit: eGFRcysC (%) | |||

| 12.50 | 56.25 | 31.25 | ||||

| Clinical Characteristics: | Increased BMI (%) | Decreased BMI (%) | Autoimmune diseases (%) | Liver diseases (%) | Muscle mass issues (%) | Arterial Hypertension (%) |

| 43.75 | 12.50 | 43.75 | 31.25 | 50.00 | 68.75 | |

| Comorbidities: | Smoking (%) | Diabetes mellitus (%) | Proteinuria (%) | Kidney transplant (%) | Hypothyroidism (%) | |

| 18.75 | 37.50 | 56.25 | 18.75 | 18.75 | ||

| Clinical Scenario | Recommended Equation | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Routine Screening | eGFRcr (CKD-EPI 2021) | Cost-effective; sufficient for stable patients with normal body composition. |

| Suspected Error/High Risk (Extremes of muscle mass, elderly, amputation) | eGFRcr-cysC | Mitigates muscle mass bias; improves accuracy. |

| Dynamic/Acute Changes (AKI, unstable creatinine) | eGFRcysC | Shorter half-life; less dependent on muscle metabolism. |

| Discordant Results (Diff > 15 mL/min/1.73 m2) | eGFRcr-cysC or mGFR | Combined equation balances errors; mGFR provides a definitive answer. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Osredkar, J.; Klemenčič, I.; Kumer, K.; Pajek, J.; Knap, B. Comparison of Creatinine-, Cystatin C-, and Combined Creatinine–Cystatin C-Based Equations for Estimating Glomerular Filtration Rate: A Real-World Analysis in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2026, 27, 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010364

Osredkar J, Klemenčič I, Kumer K, Pajek J, Knap B. Comparison of Creatinine-, Cystatin C-, and Combined Creatinine–Cystatin C-Based Equations for Estimating Glomerular Filtration Rate: A Real-World Analysis in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2026; 27(1):364. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010364

Chicago/Turabian StyleOsredkar, Joško, Iza Klemenčič, Kristina Kumer, Jernej Pajek, and Bojan Knap. 2026. "Comparison of Creatinine-, Cystatin C-, and Combined Creatinine–Cystatin C-Based Equations for Estimating Glomerular Filtration Rate: A Real-World Analysis in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 27, no. 1: 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010364

APA StyleOsredkar, J., Klemenčič, I., Kumer, K., Pajek, J., & Knap, B. (2026). Comparison of Creatinine-, Cystatin C-, and Combined Creatinine–Cystatin C-Based Equations for Estimating Glomerular Filtration Rate: A Real-World Analysis in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 27(1), 364. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms27010364