Abstract

Waardenburg syndrome (WS) represents a group of genetic conditions characterized by auditory and pigmentation defects. Pathogenic variants in PAX3, MITF, SOX10, EDN3, EDNRB, SNAI2, and KITLG genes have been associated with WS across multiple populations; a comprehensive study of WS in Africa has not yet been reported. We conducted a systematic review of clinical expressions and genetics of WS across Africa. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines were followed, and the study protocol was registered on PROSPERO, the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (2025 CRD420250655744). A literature search was performed on Google Scholar, PubMed, Scopus, Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), Global Index Medicus, African-Wide Information, ScienceDirect, Connecting Repositories (CORE), and the Web of Science databases. We reviewed a total of 15 articles describing 84 WS cases, which showed no gender bias and a mean age at reporting of 17.5 years. Congenital, sensorineural, and profound hearing loss was described in most cases (66.7%; n = 56/84). WS type 2 (WS2), with characteristically no dystopia canthorum, is the predominant subtype (36.9%; n = 31/84). Pathogenic variants in four WS known genes, i.e., PAX3 (13 families), SOX10 (7 families), EDNRB (4 families), and EDN3 (1 family), were reported in Morocco, Tunisia, and South Africa. One candidate gene (PAX8) was described in one family in Ghana. Two non-syndromic hearing loss (NSHL) genes (BDP1 and MYO6) were reported in two separate families in South Africa, suggesting a possible phenotypic expansion. The highest number of WS cases was described in South Africa (38.1%; n = 32/84) and Tunisia (26.2%; n = 22/84). Gene variants were missense (27/43), deletion (7/43), splicing (5/43), nonsense (2/43), indel (1/43), and duplication (1/43), chiefly segregating in an autosomal dominant inheritance mode. There was no functional data to support the pathogenicity of putative causative variants. This review showed that WS2 is the most common in Africa. Variants in PAX3 and SOX10 were the predominant genetic causes. This study emphasizes the need to further investigate in-depth clinical characterization, molecular landscape, and the pathobiology of WS in Africa.

1. Introduction

Waardenburg syndrome (WS) comprises a group of heterogeneous genetic conditions, characterized by hearing loss (HL) and pigmentation abnormalities of the skin, hair, and eyes. WS is the most prevalent (2–5%) syndromic defect associated with congenital sensorineural HL [1,2,3]. Based on clinical features, WS can be classified into four types (WS1-4). Presence or absence of dystopia canthorum distinguishes WS1 (MIM# 193500) from WS2 (MIM# 193510; 600193; 606662; 608890; 611584). Limb anomalies differentiate WS3 (MIM# 148820) from WS1, while WS4 (MIM# 277580), also known as Shah–Waardenburg or Waardenburg–Hirschsprung syndrome, is defined by the presence of aganglionic megacolon. Despite this clinical heterogeneity, HL remains the most disabling feature affecting the well-being and quality of life of individuals with WS.

Genetically, WS is equally heterogeneous. To date, pathogenic variants in six established genes (PAX3, MITF, SOX10, EDN3, EDNRB, and SNAI2) and two candidate genes (KITLG and PAX8) have been associated with the condition worldwide (https://hereditaryhearingloss.org/waardenburg, accessed on 30 June 2025). Over 400 WS-associated variants have been reported [4], and multiple genetic subtypes have been defined, particularly within WS2 (WS2A, B, C, D, and E) and WS4 (WS4A, B, and C). Nevertheless, the molecular underpinnings driving the variable clinical expressions and incomplete penetrance remain unclear.

A prevailing biological explanation positions WS as a neurocristopathy arising from defects in the migration, proliferation, and differentiation of neural crest-derived cells [1,4,5]. The disruption of these developmental pathways affects melanocytes, craniofacial structures, limb musculature, and enteric ganglia, providing a unifying model for the multisystem phenotype. Alternatively, the characteristic craniofacial features have led authors to propose that WS may be a variation of branchial arch syndrome [6,7]. However, this hypothesis does not fully account for its broad range of clinical manifestations.

While there is a fair amount of literature on WS from other continents, a comprehensive study of WS in Africa has not yet been reported. In this systematic review, we present the most comprehensive assessment to date of the phenotypic spectrum and genetic causes of WS in Africa.

2. Materials and Methods

We investigated all published articles reporting and describing WS phenotypes and associated genetic etiology from Africa, following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [8]. We registered the study protocol and strategy for this review on PROSPERO, the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews, with the registration number under the following reference: 2025 CRD420250655744.

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

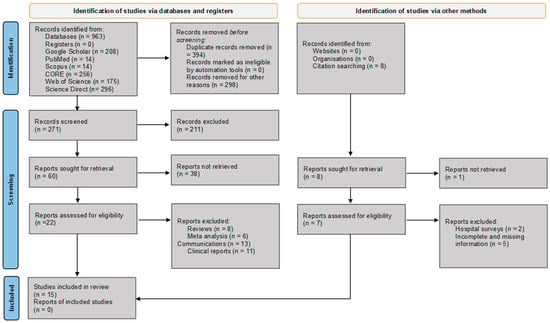

We conducted an extensive electronic database search, including Google Scholar, PubMed, Scopus, Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), Global Index Medicus, African-Wide Information, ScienceDirect, Connecting Repositories (CORE), and the Web of Science, for relevant articles. The search strictly used the following search string: Waardenburg Syndrome AND “Africa” AND “Genetics”, Waardenburg Syndrome AND “Africa” AND “Genetic Variants”, and Waardenburg Syndrome AND “Africa” AND “Genetic Variants” NOT “Review” in [Title AND/OR Abstract] separately. Zotero reference manager (https://www.zotero.org/) was used to build search results and generate a bibliography, and citations were retrieved from the search build folder. The PRISMA schematic flow chart guide was followed for the identification, screening, eligibility, and selection of included articles (Figure 1). The article search parameters covered WS disease-associated and/or causal variants reported in Africa. All cited references in the selected articles that met the outlined study inclusion criteria were checked, retrieved, and considered for synthesis until no further relevant studies were identified.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and inclusion of studies for data extraction, synthesis, and analysis [8]. CORE = COnnecting REpositories.

2.2. Selection Criteria and Data Extraction

The literature search was conducted until 28 February 2025, with regular updates, considering only full-text articles in English for information retrieval. Study eligibility was assessed using the following inclusion criteria: HL case description with WS and/or WS-like clinical manifestations; and WS case with probable genetic etiology and/or associated with a likely pathogenic variant. In addition to removing duplicates, reviews and meta-analyses, policy documents, communications, articles reporting on non-African WS cases, and unrelated studies were systematically excluded, in line with the PRISMA guidelines, based on the title and abstract, as well as articles not published in English.

For selected articles, demographic variables (ethnic identity and origin, gender, and age at phenotype onset), clinical phenotypes (HL type, cause, severity, and laterality), and genetic characteristics (gene, variant, allele frequency, variant pathogenicity, variant classification tools used, genetic investigation strategy, variant analysis method, variant annotation, and filtration strategy) were captured. Reported disease-causing variants and WS-associated variants were manually curated using the American College of Medical Genomics (ACMG) [9] guidelines. Alternate allele frequency (AAF) of variants was queried on relevant population databases, including Bravo (https://bravo.sph.umich.edu/) and TOPMed (https://topmed.nhlbi.nih.gov/), accessed on 30 June 2025.

Data extraction, quality assessment, and synthesis were conducted independently by the first and second authors of this manuscript (ETA and RPW). To avoid article selection bias, Sohani et al.’s quality of genetic studies (Q-Genie) [10], the Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS tool) [11], Hoy et al.’s risk-of-bias assessment [12], and the PRISMA quality of meta-analysis tools were used (Tables S1–S4). Altogether, the relevance of each study’s outcome informed the final decision for selection. All discrepancies in data extraction, study selection, and synthesis were thoroughly discussed and resolved by all authors.

2.3. Data Analysis

Study-level characteristics (publication year, type of investigation, study design and method of examination, and first author), participant characteristics (number of families, number of individuals affected, age of WS onset, gender, population, and WS type; pigmentation disorders, dystopia canthorum, limbs defect, intestinal complications, and mobility disorder), HL features (type, severity, laterality, additional auditory report, and examination details), and genetic variant details (gene, transcript, variant (Human Genome Variation Society nomenclature), dbSNP reference SNP, protein change, pathobiology, penetrance, reported pathogenicity, inheritance mode, ACMG classification, in silico variant effect prediction tools scores, ClinVar, ClinGen, and Uniprot) were systematically extracted and analyzed. To examine molecular mechanisms underlying phenotypic variability and incomplete penetrance in WS, publicly available functional evidence for each implicated gene-disease pair was also reviewed.

For studies describing multiple individuals, only participants with sufficient phenotypic or genetic information were included in the analysis. All statistical calculations were performed using STATA 19 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Article Search Results

Figure 1 illustrates the schematic flow chart of the article selection process. A total of 564 articles were initially identified from the title and abstract search. After removing duplicates and excluding non-English articles, non-African reports, and unrelated studies, 60 articles were considered for full-text review. Of these, 15 studies met the inclusion criteria and were selected for data extraction, synthesis, and analysis [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28].

Of note, seven studies partially met the inclusion criteria but were excluded from analysis due to incomplete or missing clinical and genetic information. Most of these reports consisted of clinical surveys of deceased individuals presenting with WS-like features. One study described a probable founder variant in a three-generation family pedigree [29], while a related investigation reported 52 individuals with WS from 11 Southern African families but provided no individual-level clinical or molecular data [30]. Another survey of 3,006 deaf children identified 90 individuals presenting with WS features but lacked detailed phenotypic characterization [31]. A report describing a 9-year-old girl with WS and bilateral profound HL was excluded due to insufficient information [32]. Similarly, a prevalence study that described 13 WS cases with suspected autosomal dominant inheritance among black South Africans lacked adequate detail for inclusion [33]. A school-based survey of 240 deaf children identified 16 WS cases, but no phenotypic information was provided [34]. Another report describing 8 individuals with WS features among 366 deaf persons screened in Cape Town lacked essential clinical and genetic details and was therefore excluded [35]. Additional studies were excluded because full-text access was unavailable, although their titles suggested potential genetic contributions to WS in South Africa, Nigeria, and Kenya [36,37,38,39].

The 15 articles that met the study inclusion criteria described 84 WS cases from 57 families across ten (10) countries in Africa. Table 1 describes the WS participants reported in this article.

Table 1.

Reviewed Waardenburg syndrome studies’ clinical parameter distribution in Africa.

3.2. Biased and Quality Assessment

Risk-of-bias and quality assessments of the selected studies, evaluated using three independent tools, are presented in Tables S1–S3 [10,11,12]. Overall, the included studies demonstrated a low risk of bias.

3.3. Waardenburg Syndrome Participants’ Clinical Phenotypes

Across the 15 eligible studies, a total of 84 WS-affected participants were reported. Of these cases, 78.5% (n = 66/84) had gender information, with an equal distribution of males and females (50.0%; n = 33/66, Table 1). The mean age of participants was 17.5 years, with a standard deviation of ±12.9 (ages were available for 48/84 participants).

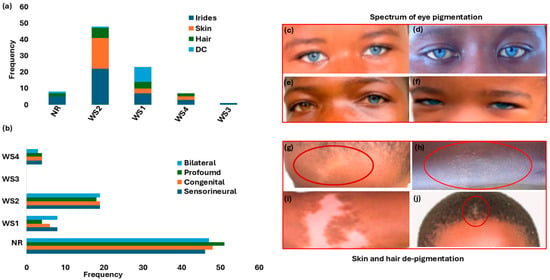

Regarding auditory phenotype manifestations, sensorineural defects were the principal cause of HL (66.7%, n = 56/84). Two independent reports described conductive and mixed HL (1.2%; n = 1/84). The HL type was undetermined in a significant proportion of WS cases (30.9%; n = 26/84). Most reviewed cases (67.8%; n = 57/84) described congenital HL. One prelingual onset was reported, and 30.9% (n = 26/84) did not report any information on HL type (Figure 2a and Table 1). Bilateral HL was the most frequently observed laterality pattern (70.2%, n = 59/84), with unilateral HL reported in one case, while the remaining 28.5% (n = 24/84) had no laterality information. Although the severity of HL among cases was predominantly profound (60.7%; n = 51/84), a significant number of affected individuals’ degree of severity was undetermined (26.2%; n = 22/84, Table 1 and Figure 2b). None of the studies provided longitudinal follow-up, preventing the assessment of HL progression.

Figure 2.

Waardenburg syndrome: characteristic features and spectrum of pigmentation presentations. Panel (a): Hearing loss phenotypes across WS types. Panel (b): Distribution of pigmentation abnormalities (iris, skin, and hair) and dystopia canthorum by WS type. (c–f) shows the array and shades of eyes, hair, and skin pigmentations. Panels (c,d,f) show bilateral blue eyes (hypochromic blue). Panel (e) shows unilateral complete heterochromia iridum (brown right eye and blue left eye). Panels (g–i) depict the depigmentation of skin WS feature presentations (forehead and chest, indicated with the red circles). Panel (j): Premature hair greying (indicated with the red circle). Figure 2c–j images were adapted from our open-access and previously published data (https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4425/16/3/257 and https://www.nature.com/articles/s42003-022-03326-8 accessed on 25 June 2025). WS = Waardenburg syndrome; NR = not reported; DC = dystopia canthorum.

3.4. Waardenburg Syndrome Subtype Classification

Figure 2a details the distribution of the different WS types, based on clinical presentations. WS2 (no dystopia canthorum) was the most reported (36.9%; n = 31/84). A significant proportion of participants had no data on WS classification type (44.0%; n = 37/84) (Figure 2a and Table 1).

The variable clinical expressions and incomplete penetrance, including degree of pigmentation defect (striking blue eyes, iris discoloration and heterochromia, premature greying, and skin depigmentation), are shown in Table 1 and Figure 2c–h. Iris discoloration was present in all WS types, characteristically described as sapphire-blue eyes in over 52% (44/84); 11.9% (10/84) as blue eyes; and the incidence of isolated bright blue eyes, segmented, sapphire, and complete blue eyes in separate reports (Table 1 and Figure 2c–h). Skin and hair pigmentation disorders were also reported in WS1, WS2, and WS4 (Table 1 and Figure 2g–j).

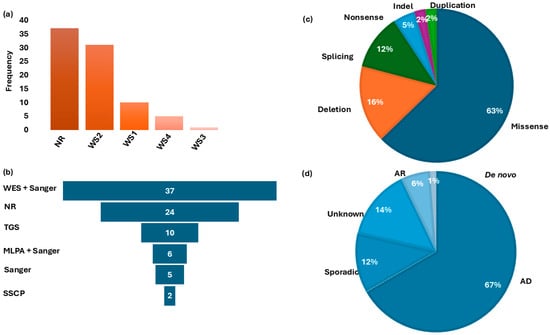

3.5. Waardenburg Syndrome Genetic Aetiology

Five distinct molecular methods were used across the included studies to investigate the genetic basis of WS (Figure 3a). Whole-exome sequencing (WES) followed by Sanger sequencing was the most commonly employed approach (44.0%; 37/84). Other molecular techniques (Figure 3b) included targeted gene sequencing (TGS) in 11.9% (n = 10/84), multiple ligation dependent probe amplification (MLPA) combined with Sanger sequencing (7.1%; n = 6/84), Sanger sequencing alone (5.9%; n = 5/84), and single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) (2.4%; n = 2/84). WES investigations typically involved sequencing at least two affected individuals per family, together with first-degree relatives, followed by Sanger sequencing to confirm candidate variants and perform segregation analysis. TGS employed a 113-gene hearing loss panel sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform.

Figure 3.

Waardenburg syndrome type distribution, Molecular investigation methods, gene variants classification, and mode of inheritance. Panel (a): Distribution of WS-type frequencies in studies reported in Africa. Panel (b) shows the frequency of different molecular methods used for genetic investigations. Panel (c): Distribution of associated gene variants. Panel (d): Classification of the pattern of inheritance in families reviewed. WS = Waardenburg syndrome; WES = whole-exome sequencing; NR = no report on molecular methods; TGS = targeted gene sequencing; MLPA = multiple ligation-dependent probe amplification; SSCP = single-strand conformation polymorphism; AD = autosomal dominant; AR = autosomal recessive; Indel = insertion/deletion.

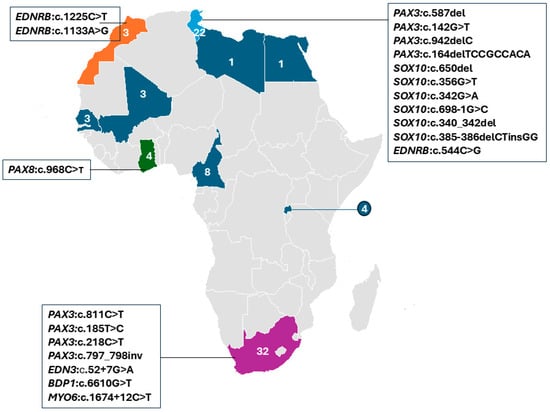

South Africa accounted for the largest proportion of WS cases in the studies reviewed, with 38.1% (32/84), followed by Tunisia with 26.2% (22/84) of individuals (Figure 4). Putative genetic etiology was reported in 71.4% (60/84) of individual WS cases. Pathogenic variants were identified in four established WS genes, in a total of 26 families, i.e., PAX3 (13 families), SOX10 (7 families), EDNRB (4 families), and EDN3 (1 family), which were reported in Morocco, Tunisia, and South Africa, respectively. Additionally, a candidate variant in PAX8 was described in one family from Ghana (Figure 4; Table 2). Thus, PAX3-associated variants were frequently reported in 46.1% (12/26 families), followed by SOX10 variants at 23.1% (6/26 families) and 15.3% (4/26) and 3.8% (1/26 families) in EDNRB and EDN3, respectively. In addition, variants in two non-syndromic hearing loss (NSHL) genes (BDP1 and MYO6) were reported in two independent South African families with WS features, suggesting a possible phenotypic expansion. A total of 24 cases remained unresolved, including 13 simplex cases, 2 cases from one multiplex Ghanaian family, and 9 cases from five multiplex South African families, even after WES investigations.

Figure 4.

Distribution of reported WS studies by African country, with at least one report (colored). The specific genes and variants identified in affected individuals are indicated. The numbers show the summed reports of Waardenburg syndrome individuals in each country, while different colors are used to differentiate the countries.

Table 2.

Genetic characterization of reported variants among Waardenburg syndrome cases reported in Africa.

Analysis of the reported genes against the WS types confirmed that WS1 and WS3 were primarily associated with PAX3 variants, whereas WS2 was linked to SOX10 variants, and WS4 cases were associated with both EDNRB and SOX10 variants (Table 2). PAX3 pathogenic variants were identified in both WS1 and WS3 cases. Pathogenic variants in SOX10 were predominantly reported in WS2 and WS4 cases. EDNRB and SOX10 variants were described exclusively in WS4 separately (Table 2). EDNRB variants were dominant in Morocco.

Within these genes, likely causal variants were identified in 51.1% of the total WS cohort (43/84). Of these, 60.4% (26/43) were recurrent within countries and likely population-specific (Figure 4, Table 2). In addition, we found population-/country-specific variants, e.g., in PAX3 (Table 2), suggesting possible founder effects. As described in Figure 3c, the identified causal variants consisted of missense (27/43), deletion (7/43), splicing (5/43), nonsense (2/43), indel (1/43), and duplication (1/43) types. Observed segregation of phenotype with the identified genetic variants was mostly compatible with an AD pattern of inheritance (Figure 3d and Table 2).

3.6. Manual Curation and Comparative Review of Targeted WS-Associated Variants

Manual curation of the reported variants revealed possible mutational hotspots at specific amino acid positions for some of the identified PAX3 and SOX10 variants in WS individuals. For example, at the PAX3 (NM_181458.4):c.142G>T-p.(Gly48Cys) variant position, four previously reported pathogenic variants (p.Gly48fs, p.Gly48Ala, p.Gly48Arg, and p.Gly48Ser) that alter the same amino acid (a different nucleotide change in the codon) were identified (Table S5). In addition, PAX3 (NM_181458.4):c.808G>C-p.(Arg270Gly), known as the WS1 pathogenic variant, affects a residue at which other pathogenic substitutions have been described in global cohorts, including p.(Arg270Cys), p.(Arg270His), p.(Arg270Pro), and p.(Arg270Ser). At amino acid position 271, c.811C>T-p.(Arg271Cys) identified in a WS1 case corresponds to the same position as other known PAX3-p.(Arg271Gly) and p.(Arg271His) pathogenic variants, which were previously described. Likewise, a variant that alters the amino acid codon in SOX10(NM_006941.4):c.385-386delCTinsGG-p.(Leu129Pro) was identified, and the previously reported SOX10-p.(Leu129Pro), a known WS pathogenic variant, occurred at the same position (Table S5).

To further evaluate the biological significance of the reported disease-associated variants, we curated the pathogenicity of the reported gene variants using the ACMG guidelines and queried TopMED and Bravo databases (Table 1). The reported variant classification established 44.2% (19/43) as pathogenic, 30.2% (13/43) as likely pathogenic, 4.6% (2/43) as benign, and 20.9% (9/43) as a variant of uncertain significance (Table 2). Investigations to identify the likely WS causal variants were limited to in silico variant effect prediction tools and databases for putative variants prioritization and classification. Importantly, none of the studies conducted cell-based and/or in vivo functional experiments to support the pathogenicity of the identified variants.

Despite the limited knowledge on WS pathogenesis, the wide phenotypic spectrum has been primarily linked to the disruption of normal regulatory networks, which primarily compromise neural crest cell development and melanocyte differentiation [40]. WS-implicated genes likely share common interactive networks and pathways, which may support their biological significance in WS development. Collectively, WS genes are involved in molecular processes including melanocyte differentiation, neural crest development, transcription regulation, neural cell migration, and pigmentation [41]. A review of available functional and in silico data highlights PAX3-SOX10-MITF as central in the regulatory network under a hierarchical transcription control [42]. Early neural crest cell specifications have been demonstrated to be regulated tightly by PAX3, a key upstream transcription factor [43]. Whereas SOX10 is involved in both neural crest delineation and melanocyte differentiation regulation, MITF modulates melanocyte development and pigmentation [44]. At the cellular level, PAX3 and SOX10 synergistic activation via physical interaction activates MITF. Coordinated by cooperative enhancement, PAX3-SOX10 directly binds to a conserved regulatory element in the MITF promoter region, which has been demonstrated by co-immunoprecipitation [45].

On the other hand, the endothelial network interaction genes (EDN3 and EDNRB) operate in parallel to this transcription regulatory network [46]. The successful binding of the ligand EDN3 to its receptor EDNRB affects the downstream cascade of signaling events critical for neural crest cells migration, which is essential in enteric nervous system development [46]. Wnt-signaling components are believed to be potential modulators of WS gene expression, culminating in phenotype variability (neural crest cells’ fate-dependent pathology) [47]. Post-transcriptional regulation mechanisms, including nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) [48], alternative splicing, and microRNA activity on WS genes’ expressivity and penetrance, likely lead to the inter-intra family phenotype heterogeneity observed.

4. Discussion

This systematic review is the most comprehensive integrative clinical and genetic analysis of WS from data across Africa. Collectively, the reviewed studies highlight an urgent need for more extensive clinical assessment and detailed genetic characterization of individuals with HL and suspected WS features across the continent. Indeed, findings reveal substantial gaps in clinical documentation and subtype-specific diagnostic criteria, which are essential for accurate classification. Genetic characterizations of WS-associated variants are reported in just a few countries (10/54). There was, as expected, a high allelic and locus heterogeneity for established WS genes. Moreover, there were 24 unresolved cases, including some from six multiplex families following exome sequencing analysis, suggesting the high prospect for novel variants and candidate gene discovery in largely underexplored and highly genetically diverse African populations [15]. However, the high proportion of molecularly unsolved cases, particularly among individuals labelled as WS2—where the defining clinical features (prelingual sensorineural hearing loss and pigmentary anomalies) are inherently less specific than those of WS1, WS3, or WS4—likely reflects a combination of diagnostic imprecision, as attested by substantial gaps in clinical documentation; phenotypic overlap with other hearing loss entities; blended or dual genetic diagnoses (Mendelian or otherwise); and pathogenic variation in known WS genes that remains undetected by conventional first-tier testing strategies such as Sanger sequencing or capture/PCR-based short-read NGS.

Overall, the observations reported here are broadly consistent with global WS epidemiology [1,49]. Nevertheless, over 50% of WS individuals exhibited sensorineural, congenital, bilateral, and profound HL; however, comprehensive data on audiological assessment, including auditory brainstem response (ABR), radiological tests, and inner ear imaging recommended for thorough WS evaluation, were absent in the studies analyzed. The large fraction of participants lacking formal audiometry likely reflects systemic challenge, a severe shortage of audiologists, limited healthcare access, inadequate diagnostic equipment, and financial constraints across many African settings [50]. Sociocultural factors, including the stigma and neglect associated with HL and pigmentation anomalies characteristic of WS, may also deter affected individuals from seeking clinical evaluations [4,51]. Additionally, the complete absence of longitudinal audiological information on affected individuals further magnifies the reported challenge of one audiologist per million people in 78% of African countries, compared to 10 audiologists per million in 52% of countries across Europe [49].

WS2 is the most common subtype reported among participants reviewed, showing high inter- and intrafamilial phenotype variability and incomplete penetrance. This finding aligns with global patterns [1]. In contrast, WS3 remains rare, also consistent with previous reports [1,4]. Likewise, AD inheritance in 67% of cases analyzed conforms to the often-reported pathogenic variant segregation pattern in families with WS disorder globally [1]. However, variations in clinical expression and incomplete phenotype documentation undermine the reliability of subtype classification across African cases. These limitations highlight the potential utility of integrating genetic findings with clinical features in refining WS subtype diagnosis, particularly when clinical information is incomplete. Strengthening genetic medicine infrastructure, including clinical genetics services and molecular diagnostic capabilities, is therefore essential for accurate WS classification in Africa.

Though the MLPA, TGS, and SSCP molecular investigation methods used are very specific and effective in identifying single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and small indels (insertions or deletions), they lack the breadth of WES. Given the limitations of WES in detecting complex genomic rearrangements, future applications of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) may be critical for resolving these cases and uncovering novel disease mechanisms. Of the seven known WS genes (PAX3, MITF, SNAI2, SOX10, EDNRB, EDN3, and KITLG candidate genes), pathogenic variants in four WS genes (PAX3, SOX10, EDNRB, and EDN3) and one candidate WS gene (PAX8) were implicated in cases reviewed across 10 African countries. We also report possible mutation hotspots that could be important for molecular studies on WS globally. In addition, we found population-/country-specific variants, e.g., in PAX3 (Table 2), suggesting possible founder effects that merit further investigations. If confirmed with larger sample sizes, such findings could enable the implementation of an affordable targeted variant diagnosis strategy in clinical practice. However, outside these localized contexts, high allelic heterogeneity remains the prevailing pattern in the other populations and settings reported in this study. WS cases associated with PAX3 variants were categorized into WS1 mostly and, in some cases WS3, according to the clinical profile presented. WS3 is a more severe condition than WS1. Though moderately rare [1], a thorough clinical evaluation of the categorized WS1 and WS3 would have confirmed unclassified WS-type cases. For instance, evidence of musculoskeletal deformities of the upper limbs supports the WS3 diagnosis [4]. Likewise, SOX10 pathogenic variants were identified in WS2 and WS4 cases. Interestingly, MITF variants, which were primarily associated with WS2 individuals in non-African populations [52,53], were not reported in cases analyzed. However, since WS2 shares other characteristic features with WS1, extensive genetic characterization in this group of individuals may have identified some cases associated with MITF. Moreover, in the WS4 cases associated with EDNRB and EDN3 pathogenic variants, the characteristic presentation of Hirschsprung disease [54] caused by enteric nervous system disorder was inconclusive.

WS etiology, described as a paradigmatic neural defect, culminates from disrupted hierarchies of transcription regulation and signaling pathways, supporting prior deleted promoter findings [55]. Disruption of transcription regulatory networks underpins neural crest cell development and melanocyte differentiation [54]. Neural crest disorders described in neurocristopathies have been linked to unusual proliferation, survival, migration, and/or differentiation of neural crest melanocytes, manifesting the spectrum of WS clinical presentations (HL and associated pigmentation anomalies) [56]. SOX10 pathogenic variants are associated with more severe neural defects, such as olfactory bulb agenesis, frequent in Kallman and Waardenburg syndrome cases [47,57]. However, none of the neurological disorders common in patients with SOX10 pathogenic variants were reported in individuals with WS4 that we reviewed. Components of the Wnt-signaling pathway also influence WS gene expression and contribute to phenotypic variability, particularly in MITF-associated WS2 manifestations [47]. The pathological molecular mechanisms implicating the reported dysregulation of neural crest cell fate specifications include NMD [47,58], alternative splicing [59], and microRNA regulation [60]. The splice-site mutations in PAX3 and SOX10 likely translate into isoforms via alternative splicing, affecting the paired domain and C-terminal end activation domain that impact regulatory function [59,61]. Exon skipping (synthesizing nonfunctional protein) and hidden splice site activation (exon truncation and intron addition) have also been described in an isolated WS case [62]. Future studies exploring patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) models, epigenetic regulation profiling of crucial transcription networks, and transcription regulatory modifiers are imperative to generate empirical data on personalized networks and pathway interactions.

5. Conclusions

This review showed that WS2 is common in Africa and reveals the lack of comprehensive clinical and in-depth molecular characterization in reported cases. We reported variants predominantly in PAX3, SOX10, EDNRB, and EDN3, mostly inherited in an autosomal dominant manner in the families investigated. Variants in PAX3 and SOX10 were the predominant genetic causes. The observed genetic and allelic heterogeneity, as well as intra-family wide variability in clinical expressions, is similar to what is reported in WS cases in most populations. However, in-depth molecular experimentation to support the biological significance of identified variants was absent. This study emphasizes the need to further investigate in-depth clinical characterization, molecular landscape, and the pathobiology of WS in Africa. These findings revealed the urgent need to harness opportunities for novel variants and candidate gene discoveries in largely unexplored and highly genetically diverse populations in Africa.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms27010127/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.W. and E.T.A.; methodology, E.T.A. and R.P.W.; validation, E.T.A., R.P.W. and C.d.K.; formal analysis, E.T.A. and R.P.W.; data curation, E.T.A. and R.P.W.; writing—original draft preparation, E.T.A. and R.P.W.; writing—review and editing, E.T.A., R.P.W., C.d.K., C.D. and A.W.; supervision, A.W. and C.D.; funding acquisition, A.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institute of Health (NIH)’s NIH/NIMH grant U01MH127692 and NIH/NHGRI grant U01-HG-009716 awarded to AW; and the African Academy of Science/Wellcome Trust, grant number H3A/18/001, awarded to AW.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in full compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Relevant institutional ethical approvals were granted by the University of Cape Town’s Faculty of Health Sciences’ Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC REF: 039/2024, approved on 13 May 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Prior to enrollment of the participants in the original studies, the protocol was explained in the participants’ preferred language; sign language interpretation was used for affected individuals for full comprehension; signed and verbal consent was obtained before recruitment. Parental consent was obtained for one individual aged under 18 years. Written informed consent was obtained from participants for the publication of personal or clinical details along with any identifying images in this study. In the case of minors, written informed consent was obtained from their parents.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAF | Alternate allele frequency; |

| ABR | Auditory brainstem response; |

| ACMG | American College of Medicine Genetics and Genomics; |

| AD | Autosomal dominant; |

| BDPI | B double prime 1; |

| CORE | Connecting repositories; |

| DC | Dystopia canthorum; |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals; |

| EDN3 | Endothelin 3; |

| EDNRB | Endothelin receptor type B; |

| HL | Hearing loss; |

| KITLG | Kit ligand; |

| MITF | Melanocyte-inducing transcription factor; |

| MLDPA | Multiplex ligation-dependent amplification; |

| MYO6 | Myosin VI; |

| PAX3 | Paired box 3; |

| PAX8 | Paired box 8; |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses; |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid; |

| SNAI2 | Snail family transcription repressor 2; |

| SNPs | Single nucleotide polymorphisms; |

| SOX10 | SRY-box transcription factor 10; |

| SSCP | Single-strand conformation polymorphism polymerase chain reaction; |

| TGS | Targeted gene sequencing; |

| WES | Whole-exome sequencing; |

| WS | Waardenburg syndrome. |

References

- Song, J.; Feng, Y.; Acke, F.R.; Coucke, P.; Vleminckx, K.; Dhooge, I.J. Hearing Loss in Waardenburg Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Clin. Genet. 2016, 89, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H. Waardenburg Syndrome. In Atlas of Genetic Diagnosis and Counseling; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1–9. ISBN 978-1-4614-6430-3. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, F.; Xiao, M.; Ji, D.; Zheng, F.; Shi, T. Deciphering Potential Causative Factors for Undiagnosed Waardenburg Syndrome through Multi-Data Integration. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2024, 19, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, R.; Masood, S. Waardenburg Syndrome. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Song, J.; He, C.; Cai, X.; Yuan, K.; Mei, L.; Feng, Y. Genetic Insights, Disease Mechanisms, and Biological Therapeutics for Waardenburg Syndrome. Gene Ther. 2022, 29, 479–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, B.; Campbell, N.R.; Swifts, S. Waardenbrug’s Syndrome. A Variation of the First Arch Syndrome. Arch. Dermatol. 1962, 86, 718–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleck, K.; Erhardt, G.; Lühken, G. From Single Nucleotide Substitutions up to Chromosomal Deletions: Genetic Pause of Leucism-Associated Disorders in Animals. Berl. Munch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. 2016, 129, 269–281. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oza, A.M.; DiStefano, M.T.; Hemphill, S.E.; Cushman, B.J.; Grant, A.R.; Siegert, R.K.; Shen, J.; Chapin, A.; Boczek, N.J.; Schimmenti, L.A.; et al. Expert Specification of the ACMG/AMP Variant Interpretation Guidelines for Genetic Hearing Loss. Hum. Mutat. 2018, 39, 1593–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohani, Z.N.; Meyre, D.; de Souza, R.J.; Joseph, P.G.; Gandhi, M.; Dennis, B.B.; Norman, G.; Anand, S.S. Assessing the Quality of Published Genetic Association Studies in Meta-Analyses: The Quality of Genetic Studies (Q-Genie) Tool. BMC Genet. 2015, 16, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downes, M.J.; Brennan, M.L.; Williams, H.C.; Dean, R.S. Development of a Critical Appraisal Tool to Assess the Quality of Cross-Sectional Studies (AXIS). BMJ Open 2016, 6, e011458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoy, D.; Brooks, P.; Woolf, A.; Blyth, F.; March, L.; Bain, C.; Baker, P.; Smith, E.; Buchbinder, R. Assessing Risk of Bias in Prevalence Studies: Modification of an Existing Tool and Evidence of Interrater Agreement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2012, 65, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbdelRahman, A.M.; Amin, R.H. Juvenile Open-Angle Glaucoma with Waardenburg Syndrome: A Case Report. J. Glaucoma 2021, 30, e1–e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AitRaise, I.; Amalou, G.; Bousfiha, A.; Charoute, H.; Rouba, H.; Abdelghaffar, H.; Bonnet, C.; Petit, C.; Barakat, A. Genetic Heterogeneity in GJB2, COL4A3, ATP6V1B1 and EDNRB Variants Detected among Hearing Impaired Families in Morocco. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 3949–3954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonkam, A.; Adadey, S.M.; Schrauwen, I.; Aboagye, E.T.; Wonkam-Tingang, E.; Esoh, K.; Popel, K.; Manyisa, N.; Jonas, M.; deKock, C.; et al. Exome Sequencing of Families from Ghana Reveals Known and Candidate Hearing Impairment Genes. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dia, Y.; Loum, B.; Dieng, Y.J.K.B.; Diop, J.P.D.; Adadey, S.M.; Aboagye, E.T.; Ba, S.A.; Touré, A.A.; Niang, F.; Diaga Sarr, P.; et al. Childhood Hearing Impairment in Senegal. Genes 2023, 14, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doubaj, Y.; Pingault, V.; Elalaoui, S.C.; Ratbi, I.; Azouz, M.; Zerhouni, H.; Ettayebi, F.; Sefiani, A. A Novel Mutation in the Endothelin B Receptor Gene in a Moroccan Family with Shah-Waardenburg Syndrome. Mol. Syndr. 2015, 6, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wonkam, E.T.; Chimusa, E.; Noubiap, J.J.; Adadey, S.M.; Fokouo, J.V.F.; Wonkam, A. GJB2 and GJB6 Mutations in Hereditary Recessive Non-Syndromic Hearing Impairment in Cameroon. Genes 2019, 10, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imperato, P.J.; Imperato, G.H. Clinical Manifestations of Waardenburg Syndrome in a Male Adolescent in Mali, West Africa. J. Community Health 2015, 40, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yalcouyé, A.; Traoré, O.; Taméga, A.; Maïga, A.B.; Kané, F.; Oluwole, O.G.; Guinto, C.O.; Kéita, M.; Timbo, S.K.; DeKock, C.; et al. Etiologies of Childhood Hearing Impairment in Schools for the Deaf in Mali. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 726776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkaouar, R.; Riahi, Z.; Marrakchi, J.; Mezzi, N.; Romdhane, L.; Boujemaa, M.; Dallali, H.; Sayeb, M.; Lahbib, S.; Jaouadi, H.; et al. Current Phenotypic and Genetic Spectrum of Syndromic Deafness in Tunisia: Paving the Way for Precision Auditory Health. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1384094, Erratum in Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1437233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noubiap, J.-J.; Djomou, F.; Njock, R.; Toure, G.B.; Wonkam, A. Waardenburg Syndrome in Childhood Deafness in Cameroon. S. Afr. J. Child. Health 2014, 8, 3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otman, S.G.; Abdelhamid, N.I. Waardenburg Syndrome Type 2 in an African Patient. Indian. J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2005, 71, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trabelsi, M.; Nouira, M.; Maazoul, F.; Kraoua, L.; Meddeb, R.; Ouertani, I.; Chelly, I.; Benoit, V.; Besbes, G.; Mrad, R. Novel PAX3 Mutations Causing Waardenburg Syndrome Type 1 in Tunisian Patients. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017, 103, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwibambe, E.; Mutesa, L.; Muhizi, C.; Ncogoza, I.; Twumasi Aboagye, E.; Dukuze, N.; Adadey, S.M.; DeKock, C.; Wonkam, A. Etiologies of Early-Onset Hearing Impairment in Rwanda. Genes 2025, 16, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attié, T.; Till, M.; Pelet, A.; Amiel, J.; Edery, P.; Boutrand, L.; Munnich, A.; Lyonnet, S. Mutation of the Endothelin-Receptor B Gene in Waardenburg-Hirschsprung Disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1995, 4, 2407–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharadwaj, T.; Acharya, A.; Manyisa, N.R.; Aboagye, E.T.; Peigou Wonkam, R.; Xhakaza, L.; Popel, K.; de Kock, C.; Schrauwen, I.; Wonkam, A.; et al. The Diverse Genetic Landscape of Hearing Impairment in South African Families. Clin. Genet. 2025, 108, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Saxe, M.; Kromberg, J.G.; Jenkins, T. Waardenburg Syndrome in South Africa. Part II. Is There Founder Effect for Type I? S. Afr. Med. J. 1984, 66, 291–293. [Google Scholar]

- de Saxe, M.; Kromberg, J.G.; Jenkins, T. Waardenburg Syndrome in South Africa. Part I. An Evaluation of the Clinical Findings in 11 Families. S. Afr. Med. J. 1984, 66, 256–261. [Google Scholar]

- Sellars, S.; Beighton, P. Childhood Deafness in Southern Africa. An Aetiological Survey of 3,064 Deaf Children. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1983, 97, 885–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellars, S.L.; Beighton, P. The Aetiology of Partial Deafness in Childhood. S. Afr. Med. J. 1978, 54, 811–813. [Google Scholar]

- Sellars, S.; Beighton, G.; Horan, F.; Beighton, P.H. Deafness in Black Children Is Southern Africa. S. Afr. Med. J. 1977, 51, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sellars, S.; Groeneveldt, L.; Beighton, P. Aetiology of Deafness in White Children in the Cape. S. Afr. Med. J. 1976, 50, 1193–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Sellars, S.; Napier, E.; Beighton, P. Childhood Deafness in Cape Town. S. Afr. Med. J. 1975, 49, 1135–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Butt, J.; Greenberg, J.; Winship, I.; Sellars, S.; Beighton, P.; Ramesar, R. A Splice Junction Mutation in PAX3 Causes Waardenburg Syndrome in a South African Family. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1994, 3, 197–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, T. The Waardenburg Syndrome in Southern Africa. S. Afr. Med. J. 1983, 64, 82. [Google Scholar]

- Amoni, S.S.; Abdurrahman, M.B. Waardenburg’s Syndrome: Case Reports in Two Nigerians. J. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus 1979, 16, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hageman, M.J. Heterogeneity of Waardenburg Syndrome in Kenyan Africans. Metab. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. 1980, 4, 183–184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vega-Lopez, G.A.; Cerrizuela, S.; Tribulo, C.; Aybar, M.J. Neurocristopathies: New Insights 150 Years after the Neural Crest Discovery. Dev. Biol. 2018, 444 (Suppl. S1), S110–S143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Chuong, C.-M.; Lei, M. Regulation of Melanocyte Stem Cells in the Pigmentation of Skin and Its Appendages: Biological Patterning and Therapeutic Potentials. Exp. Dermatol. 2019, 28, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potterf, S.B.; Furumura, M.; Dunn, K.J.; Arnheiter, H.; Pavan, W.J. Transcription Factor Hierarchy in Waardenburg Syndrome: Regulation of MITF Expression by SOX10 and PAX3. Hum. Genet. 2000, 107, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelms, B.L.; Labosky, P.A. Transcriptional Control of Neural Crest Development; Developmental Biology; Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, X.; Luan, C.; Zhang, Z.; Wessely, A.; Heppt, M.V.; Berking, C.; Vera, J. SOX10, MITF, and microRNAs: Decoding Their Interplay in Regulating Melanoma Plasticity. Int. J. Cancer 2025, 157, 1277–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondurand, N.; Pingault, V.; Goerich, D.E.; Lemort, N.; Sock, E.; Le Caignec, C.; Wegner, M.; Goossens, M. Interaction among SOX10, PAX3 and MITF, Three Genes Altered in Waardenburg Syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000, 9, 1907–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.; Le Moullec, J.M.; Corvol, P.; Gasc, J.M. Ontogeny of Endothelins-1 and -3, Their Receptors, and Endothelin Converting Enzyme-1 in the Early Human Embryo. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 101, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-P.; Liu, Y.-L.; Mei, L.-Y.; He, C.-F.; Niu, Z.-J.; Sun, J.; Zhao, Y.-L.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, H. Wnt Signaling Pathway Involvement in Genotypic and Phenotypic Variations in Waardenburg Syndrome Type 2 with MITF Mutations. J. Hum. Genet. 2018, 63, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hug, N.; Longman, D.; Cáceres, J.F. Mechanism and Regulation of the Nonsense-Mediated Decay Pathway. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, 1483–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamenov, K.; Martinez, R.; Kunjumen, T.; Chadha, S. Ear and Hearing Care Workforce: Current Status and Its Implications. Ear Hear. 2021, 42, 249–257, Erratum in Ear Hear. 2021, 42, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, R.H.; McMahon, C.; Waterworth, C.; Morton, S.; Platt, A.; Chadha, S.; Xu, M.J.; Der, C.; Nakku, D.; Seguya, A.; et al. Access to Ear and Hearing Care Globally: A Survey of Stakeholder Perceptions from the Lancet Commission on Global Hearing Loss. Otol. Neurotol. 2025, 46, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmalak, I.K.S.; Mahmoud, S.; ElRouby, I. Waardenburg Syndrome as a Challenging Experience in Pediatric Cochlear Implantation. J. Med. Sci. Res. 2021, 4, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, G.; Chen, K.; Yu, H.; Gao, J.; Tian, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, P.; Zhang, L.; et al. A Novel Frameshift Variant of the MITF Gene in a Chinese Family with Waardenburg Syndrome Type 2. Mol. Syndr. 2021, 12, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Chen, X.; Kong, X.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Q.; Jiao, Z.; Shi, H. Identification of Six Novel Variants in Waardenburg Syndrome Type II by Next-Generation Sequencing. Mol. Genet. Genom. Med. 2020, 8, e1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simões-Costa, M.; Bronner, M.E. Establishing Neural Crest Identity: A Gene Regulatory Recipe. Development 2015, 142, 242–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondurand, N.; Dastot-Le Moal, F.; Stanchina, L.; Collot, N.; Baral, V.; Marlin, S.; Attie-Bitach, T.; Giurgea, I.; Skopinski, L.; Reardon, W.; et al. Deletions at the SOX10 Gene Locus Cause Waardenburg Syndrome Types 2 and 4. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 1169–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojas, R.A.; Kutateladze, A.A.; Plummer, L.; Stamou, M.; Keefe, D.L.; Salnikov, K.B.; Delaney, A.; Hall, J.E.; Sadreyev, R.; Ji, F.; et al. Phenotypic Continuum between Waardenburg Syndrome and Idiopathic Hypogonadotropic Hypogonadism in Humans with SOX10 Variants. Genet. Med. 2021, 23, 629–636, Erratum in Genet Med. 2023, 25, 100855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakabayashi, T.; Takei, A.; Okada, N.; Shinohara, M.; Takahashi, M.; Nagashima, S.; Okada, K.; Ebihara, K.; Ishibashi, S. A Novel SOX10 Nonsense Mutation in a Patient with Kallmann Syndrome and Waardenburg Syndrome. Endocrinol. Diabetes Metab. Case Rep. 2021, 2021, 20–0145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isken, O.; Maquat, L.E. Quality Control of Eukaryotic mRNA: Safeguarding Cells from Abnormal mRNA Function. Genes Dev. 2007, 21, 1833–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelby, M.V. Waardenburg Syndrome Expression and Penetrance. J. Rare Dis. Res. Treat. 2017, 2, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibi, D.M.; Mia, M.M.; Guna Shekeran, S.; Yun, L.S.; Sandireddy, R.; Gupta, P.; Hota, M.; Sun, L.; Ghosh, S.; Singh, M.K. Neural Crest-Specific Deletion of Rbfox2 in Mice Leads to Craniofacial Abnormalities Including Cleft Palate. Elife 2019, 8, e45418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, T.D.; Barber, M.C.; Cloutier, T.E.; Friedman, T.B. PAX3 Gene Structure, Alternative Splicing and Evolution. Gene 1999, 237, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soosanabadi, M.; Biglari, S.; Bayat, S.; Ghorashi, T.; Sohanforooshan Moghaddam, A.; Gholami, M. A Novel Noncanonical Splicing Pathogenic Variant in PAX3 Associated with Waardenburg Syndrome Type 1 in an Iranian Family. Egypt. J. Med. Hum. Genet. 2025, 26, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.