1. Introduction

Glucagon, a peptide comprising 29 amino acids, is produced in α-cells in pancreatic islets of Langerhans (e.g., [

1]). Glucagon acts via glucagon receptors (

Figure 1, GCGR [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]). GCGR raises the activity of adenylyl cyclases in many tissues via stimulatory guanosine-triphosphate-binding proteins (G

s-proteins) [

7]. In principle, glucagon has positive inotropic and positive chronotropic effects in the heart, but these effects show species differences and age differences [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Here, we were interested in the cardiac effects of glucagon in adult mice. For instance, others reported that glucagon, in contrast to isoprenaline, failed to stimulate the activity of adenylyl cyclases in adult mouse cardiac membranes [

12]. In adult mice, one might distinguish between effects of glucagon on the heart in vivo and ex vivo. Under in vivo conditions, injection of glucagon increased the beating rate in adult wild-type mouse hearts [

13]. Injected glucagon failed to augment the beating rate in living adult transgenic mice with constitutive ablation of the GCGR [

13]. This suggests that the chronotropic effects of injected glucagon in vivo in the adult mouse are GCGR-mediated [

13]. However, in these adult transgenic mice, the GCGR was not only deleted in the heart but also in the brain [

13]. Hence, glucagon might have worked in that study via the brain GCGR. Such a central effect of glucagon might have resulted from an enhanced activity of the sympathetic outflow from the brain. Indeed, GCGR is present in the mouse brain, e.g., [

14]. Moreover, others have studied the influence of glucagon in isolated Langendorff-perfused hearts from adult wild-type mice [

15]. In that study, glucagon did not alter left ventricular pressure, but the authors did not report the beating rate after infusion of glucagon. Hence, a conceivable positive chronotropic effect of glucagon might have been overlooked [

15]. Therefore, we tested here the hypothesis that glucagon exerts a direct positive chronotropic and/or inotropic effect in the isolated, spontaneously beating right atrial preparations or isolated hearts from adult wild-type (CD1) mice. We decided to study mice because the genome of mice is currently often manipulated to elevate or reduce the expression of genes of interest as models for the human heart (e.g., [

15]). For example, mice with general deletion of the GCGR have been published [

16]. Moreover, in recent reports, GCGR antagonists could ameliorate heart failure in adult mice [

17,

18,

19]. Thence, it seems mechanistically important to understand the direct cardiac effects of glucagon and GCGR antagonists in the isolated atrium of adult mice. From a clinical perspective, the cardiac GCGR is gaining interest as a drug target for the treatment of cardiac diseases. This principle is used in the drugs retatrutide, mazdutide, survodutide and cotadutide [

20]. These drugs activate the GCGR. Fittingly, central GCGR stimulation can reduce appetite, slow gastric emptying and can increase the energy consumption in the human body. For this reason, stimulation of the GCGR might be helpful to improve the efficacy of new drugs that reduce the body weight and thus increase life expectancy. Hence, a better understanding of the GCGR in the heart and its signal transduction seems to be clinically desirable.

As mentioned, GCGR is thought to act mainly via stimulation of adenylyl cyclase. In the mouse heart, the β-adrenoceptors (using isoprenaline as an agonist) like GCGR act mainly via stimulation of adenylyl cyclases (

Figure 1). Now, stimulation of A

1-adenosine receptors in the presence of isoprenaline leads to a negative chronotropic effect in the adult mouse atrium in part via inhibition of adenylyl cyclases (e.g., [

21]). Similarly, stimulation of muscarinic receptors in the presence of isoprenaline leads to a negative chronotropic effect in the mouse atrium, also in part via inhibition of adenylyl cyclases (e.g., [

21]). We wanted to know whether a similar interaction between GCGR and muscarinic receptor agonists (using carbachol) or adenosine A

1-receptor agonists (using R-PIA) in the mammalian atrium exists. Moreover, the positive chronotropic effect of isoprenaline probably occurs via direct stimulation of HCN channels by cAMP (

Figure 1, [

22]). If glucagon acted via cardiac GCGR, then this effect should be reversed by GCGR antagonists. Here, we decided to study antagonists from two chemical classes: a peptide (desglucagon) and a small organic molecule (SC203972). In addition, we wanted to find out whether glucagon acted via stimulation of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase, via the release of noradrenaline from cardiac stores, via an inhibition of phosphodiesterases, via a stimulation of MAP kinase or via a stimulation of phospholipase C: such pathways exist for GCGR at least in non-cardiac tissues.

Glucagon stimulates the glucagon receptor (GCG-R, blocked by SC203972 and desglucagon) which leads to an increase of adenylyl cyclase (AC) activity through stimulatory GTP-binding proteins (Gs). Isoprenaline activates AC via the β-adrenoceptors (β-R, inhibited by propranolol). AC increases the formation of 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP). This cAMP stimulates the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA, inhibited by H89). PKA phosphorylates (red P in circles) and thus activates inter alia phospholamban (PLB), the inhibitory subunit of troponin (TnI), the ryanodine receptor (RYR) and the L-type calcium channel (LTCC). The cAMP can directly activate the If-currents carried by hyperpolarization-activated cation channels (HCN channels, blocked by ivabradine). The formed cAMP can be degraded to inactive 5′-AMP by phosphodiesterases (PDEs) in the mouse heart mainly via PDE IV (inhibited by rolipram). Calcium cations (Ca2+) are stored by binding to calsequestrin (CSQ) in the sarcoplasmic reticulum and are released via RYR from the sarcoplasmic reticulum. This released Ca2+ binds to troponin C on thin myofilaments, and as a result, the force is augmented. In cardiac diastole, Ca2+-concentrations fall because Ca2+ is pumped into the sarcoplasmic reticulum via a calcium ATPase (SERCA). The activity of SERCA is increased when phospholamban (PLB) is phosphorylated. The activation of GCGR can be functionally antagonized by A1-adenosine receptors (A1-R, stimulated by R-PIA and antagonized by DPCPX) or by M2-muscarinic receptors (M2-R, stimulated by carbachol and antagonized by atropine). The GCGR may activate phospholipase C (PLC, inhibited U73122), which forms inositoltrisphosphate (IP3) and MAPK (inhibited by U0126). M2-R and A1-R may in part act via opening potassium channels (PCs).

Hence, our main hypotheses were as follows:

Parts of this study have been published as abstracts [

23,

24].

2. Results

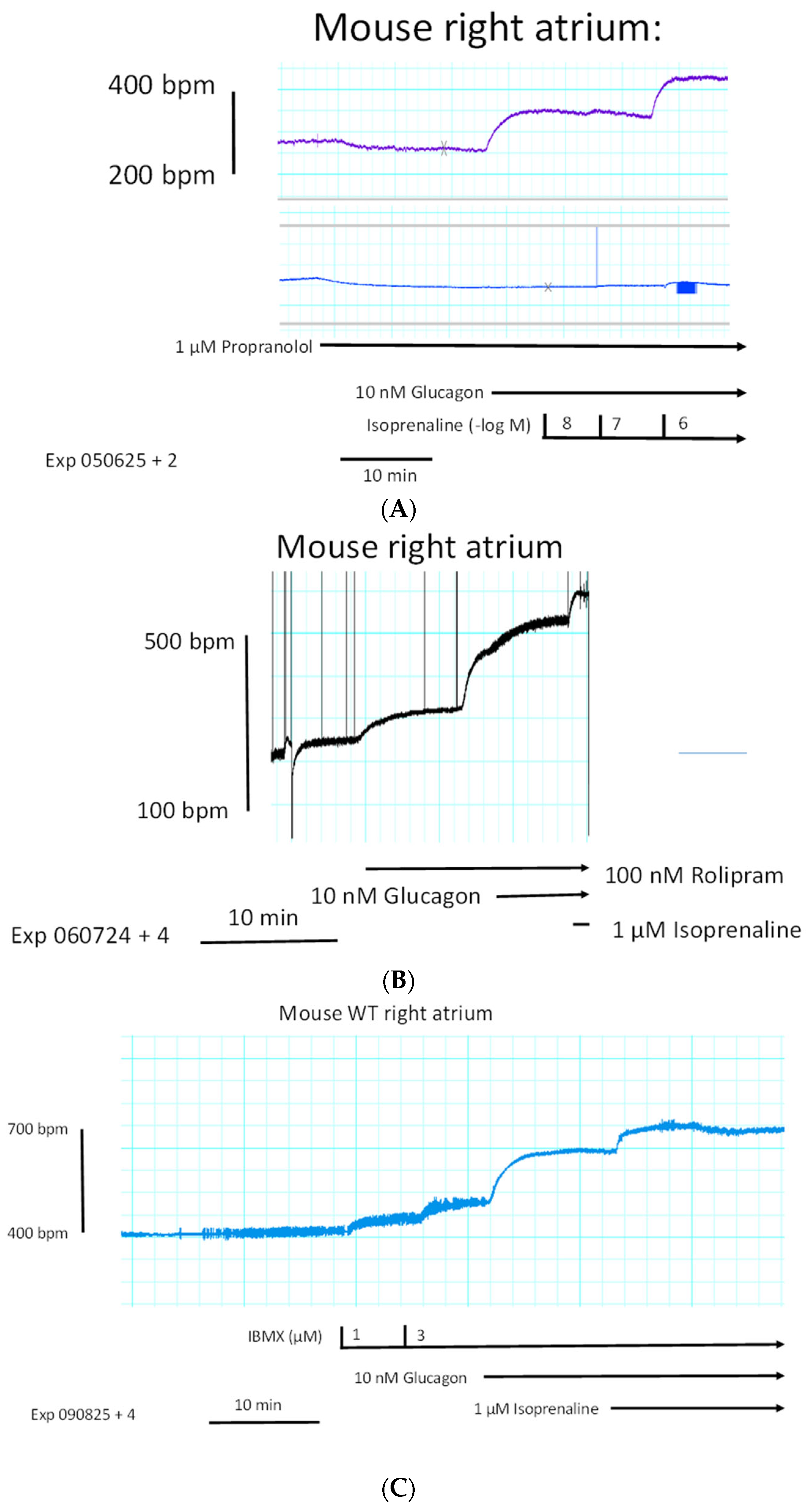

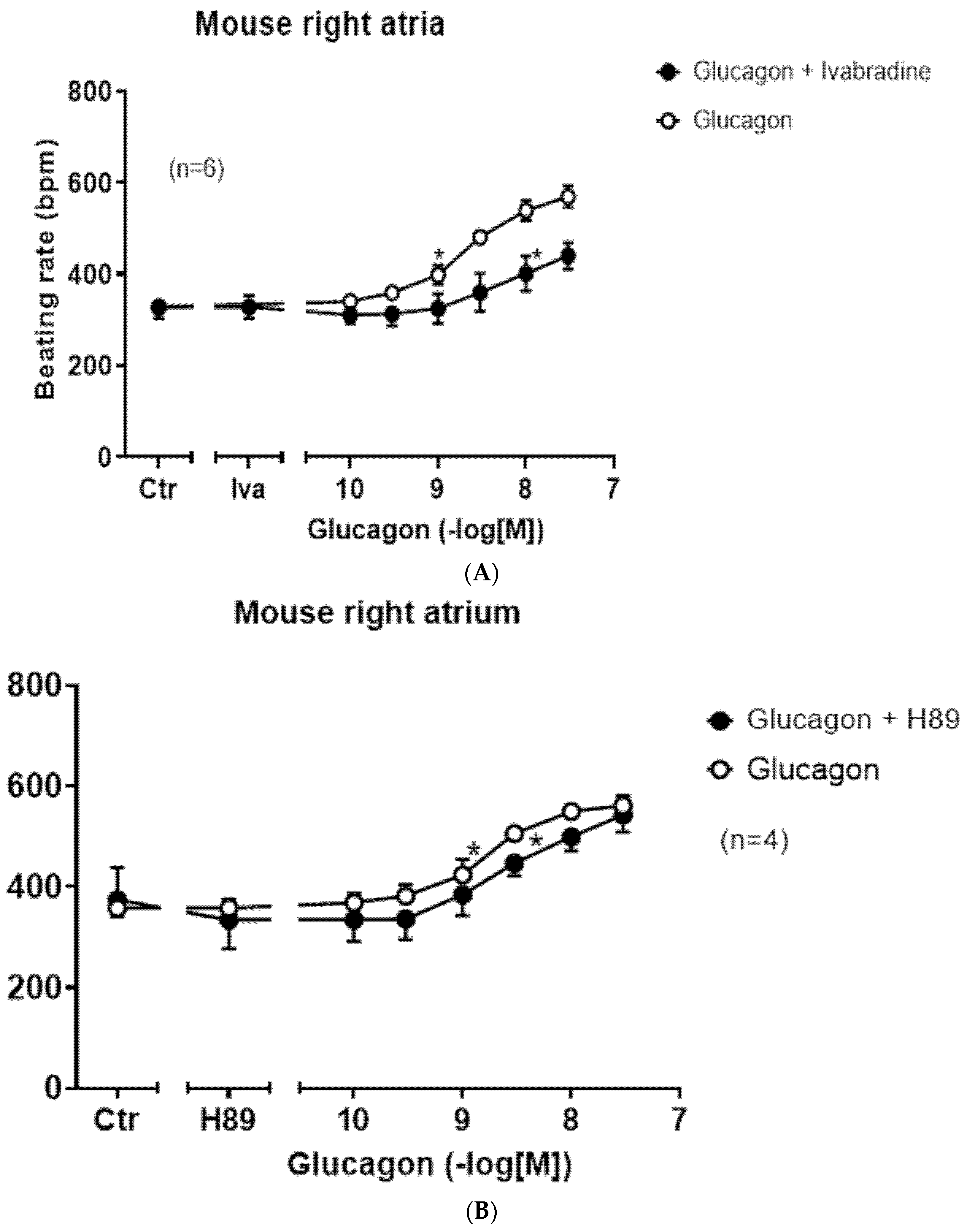

We started to compare the effects of glucagon on force of contraction in left atrial preparations and right atrial preparations. One can see in the original tracings of

Figure 2A (top tracing) that glucagon failed to increase the force of contraction in mouse left atrial preparations. However, at the same concentrations, glucagon exerted a positive chronotropic effect in right atrial preparations. This positive chronotropic effect of glucagon is seen in original recordings in

Figure 2A (lower tracing). In the very same right atrial preparation, where glucagon increased the beating rate, glucagon reduced the force of contraction (

Figure 2A, middle tracing).

Original recordings (

Figure 2A) of the force of contraction are depicted from electrically stimulated left atrial preparations (top tracing) and the force of contraction in spontaneously beating right atrial preparations (middle). Beating rate (beats per minute, bpm) in the right atrial preparation is displayed in the lower tracing. Glucagon was cumulatively applied. Ordinates give the force of contraction in millinewtons (mN) in the top and middle tracing. The ordinate in the lower tracing displays the beating rate in beats per minute (bpm). The horizonal bar gives the time in minutes (min). We repeated these experiments several times, and mean values are presented in

Figure 2B (filled circles).

Isoprenaline exerted a positive chronotropic effect in right atrial preparations (

Figure 2B, open circles). Glucagon and isoprenaline were approximately equieffective at raising the beating rate (

Figure 2B). We plotted the percentile increase in the beating rate with reference to pre-drug values in

Figure 2C. Glucagon was more potent for elevating the beating rate than isoprenaline (

Figure 2B). Both glucagon and isoprenaline augmented the beating rate (

Figure 2B). Isoprenaline in contrast to glucagon stimulated the force of contraction in right atrial preparations (

Figure 2C, closed circles).

In contrast to its effect on the beating rate, glucagon diminished the force of contraction in isolated right atrial preparations (

Figure 2D, open circles). As a control, we have plotted (

Figure 2D, squares) the force of contraction in right atrial preparations without any drug addition (time control: squares) in time-matched right atrial preparations, which can be compared with the effects of added glucagon (

Figure 2D, open circles). Under these conditions where glucagon lessened and isoprenaline raised the force of contraction in right atrial preparations (

Figure 2D), glucagon and isoprenaline shortened the time to peak tension (

Figure 2E). Glucagon (open circles) and isoprenaline (closed circles) reduced the time of relaxation in right atrial preparations (

Figure 2F).

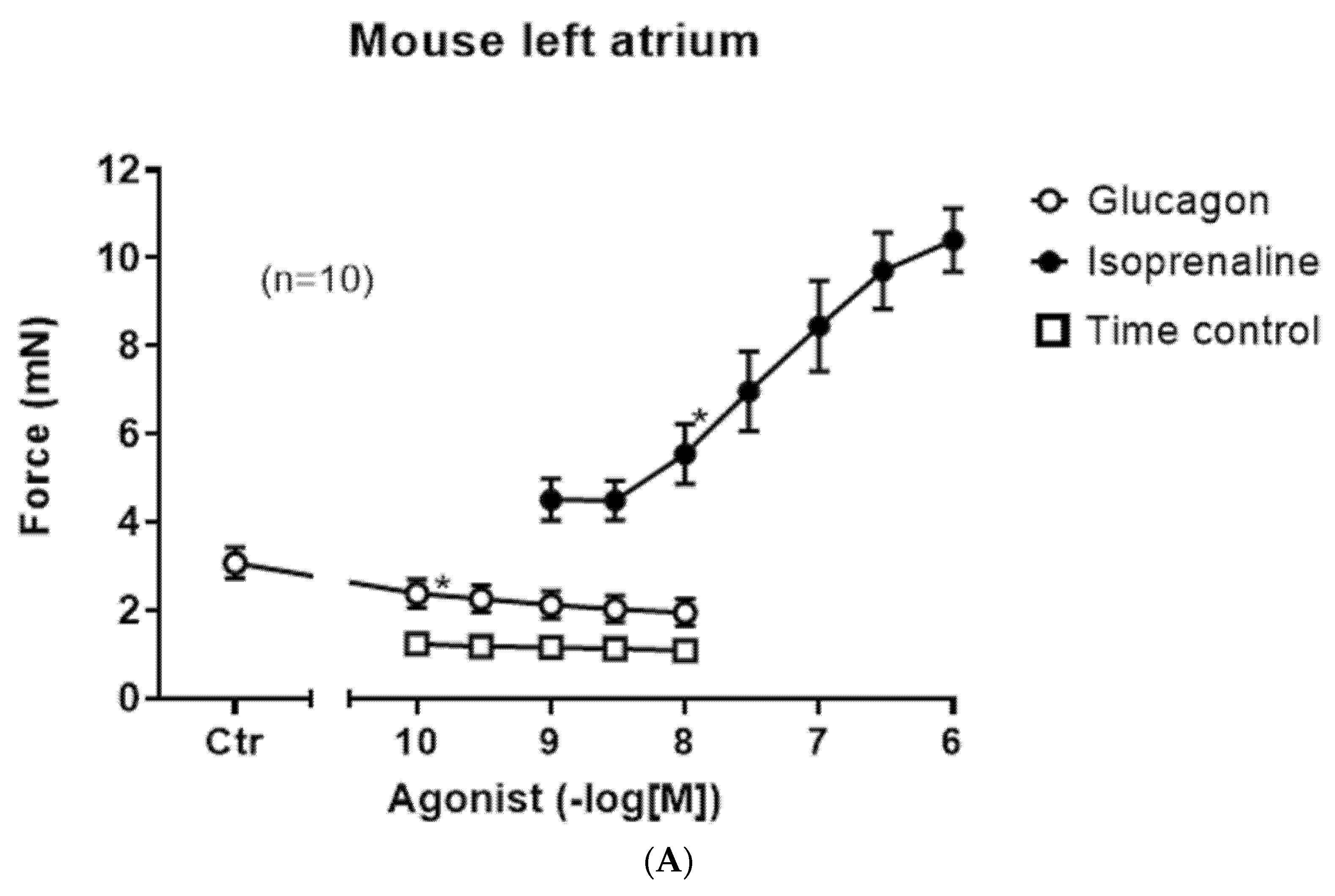

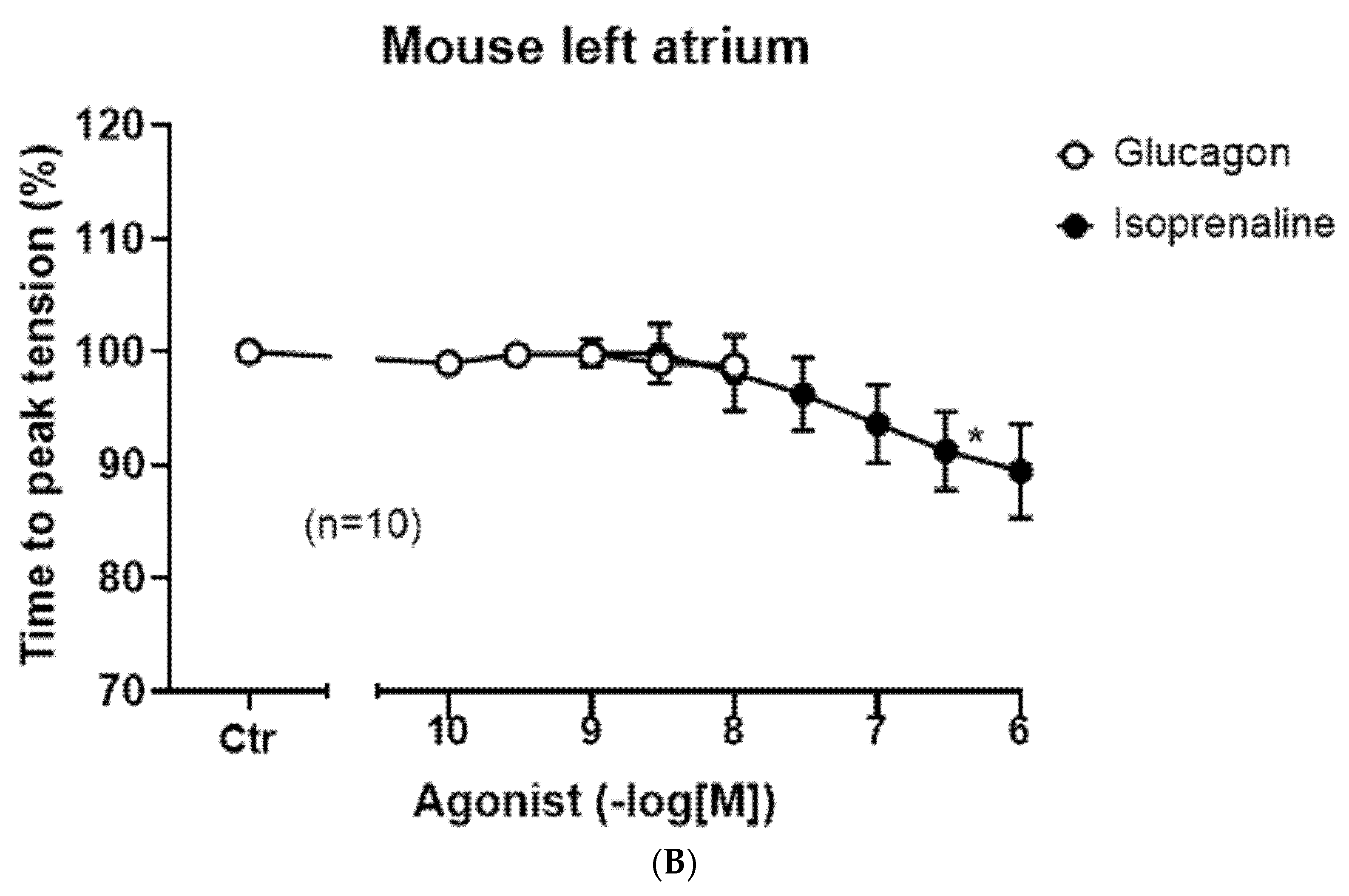

In left atrial preparations, isoprenaline exerts a positive inotropic effect (closed circle), but glucagon did not lead to a positive inotropic effect (

Figure 3A, open circles). We also performed control contraction experiments where no glucagon was added to the organ bath at comparable time points (

Figure 3A, squares), indicating that the contraction over time is quite stable in the isolated paced mouse left atrium. As expected, isoprenaline in these left atrial preparations shortened the time to peak tension (

Figure 3B, closed circle); however, glucagon did not affect the time to peak tension (

Figure 3B, open circles).

Next, we asked which receptor is involved in the positive chronotropic effect of glucagon in the right atrium. We used two selective GCGR antagonists, a small organic molecule (SC203972) [

25] and the peptide desglucagon [

26]. The effect of glucagon to augment the beating rate could be attenuated by subsequent application of the glucagon antagonist SC203972 (

Figure 4A). In separate experiments, we first applied 1 µM of SC203972 for 10 min and then added glucagon cumulatively and measured the beating rate: glucagon alone had an EC

50-value for the increase in the beating rate in right atrial preparations of 8.7 (−lg M) (

n = 16), which was shifted to the right by SC203972 to an EC

50-value of 7.8 (−lg M) (

n = 6,

p < 0.05).

We could also reduce the positive chronotropic effect of glucagon with a chemically different GCGR-antagonist. After glucagon increased the beating rate, we subsequently applied desglucagon, a peptide antagonist of GCGR. This is displayed in an original tracing in

Figure 4B and summarized in

Figure 4C.

Moreover, we altered the order of drug addition in further experiments. Here, first 1 µM of desglucagon was applied to the organ bath for 10 min and then increasing concentrations of glucagon were cumulatively added. As depicted in

Figure 4D, desglucagon shifted the concentration response curve to the right (

Figure 4D, open circles). However, no plateau for the effects of glucagon in the presence of desglucagon was obtained (

Figure 4D, closed circles). Hence, no EC

50-values or pA

2-values can be reported here. Moreover, one could speculate that once glucagon is produced in the heart or remains in heart (coming from the circulation), then desglucagon might decrease the beating rate. This, however, was not the case: when the basal beating rate under control conditions (no drugs applied) amounted to 350 ± 33 bpm, then an additional 1 µM of desglucagon led to a beating rate of 360 ± 25 bpm after 10 min, which was not significantly different (

n = 4 each,

p > 0.05).

Next, we report here that the positive chronotropic effects of glucagon in right atrial preparations were antagonized by R-PIA (PIA), an A

1-adenosine receptor agonist. This is seen in an original recording in

Figure 5A. First glucagon raised the beating rate, then additionally applied R-PIA reduced the beating rate. This effect was reversed by DPCPX, an antagonist at A

1-adenosine receptors (

Figure 5A). This is summed up in

Figure 5B. We have used R-PIA and DPCPX at these concentrations before in mouse atrial preparations. Next, we noted that carbachol reduced the positive chronotropic effects of glucagon in a right atrial preparation (compare scheme in

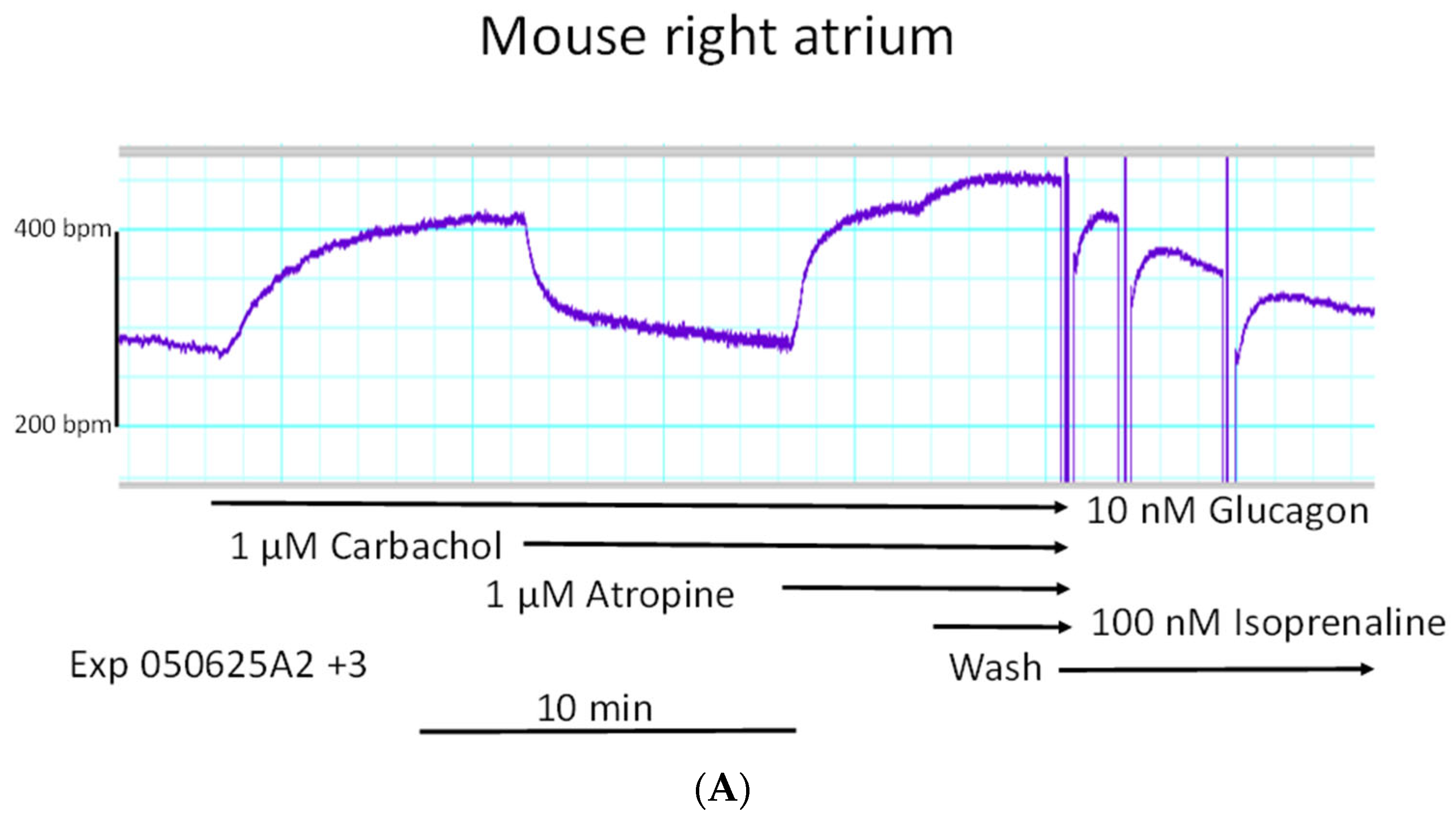

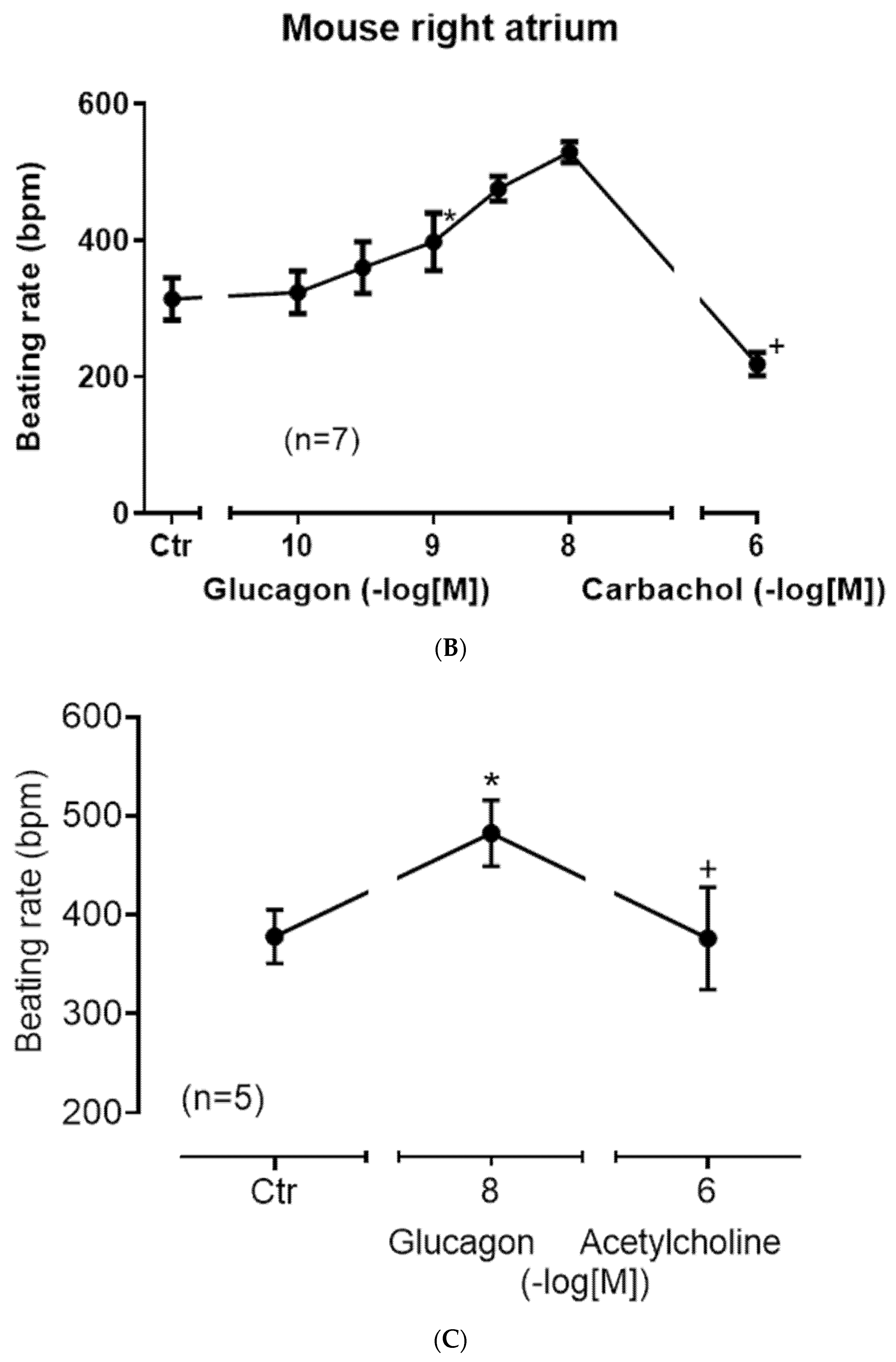

Figure 1).

This effect is exemplified in an original recording in

Figure 6A. The negative chronotropic effect of carbachol was antagonized by the muscarinic receptor antagonist atropine (

Figure 6A). This negative chronotropic effect of carbachol after the positive chronotropic effect of carbachol in such experiments is summarized in

Figure 6B.

Furthermore, instead of carbachol, we used the endogenous neurotransmitter acetylcholine itself and obtained the same result: acetylcholine diminished the positive chronotropic effect of glucagon as seen in

Figure 6C. In order to test whether glucagon might act as an indirect sympathomimetic agent, we studied a possible effect of propranolol (scheme in

Figure 1). When we first applied 1 µM of propranolol, a concentration of propranolol which was active because it slightly reduced beating rate (

Figure 7A), we noted that 10 nM of glucagon could still increase the beating rate. One might argue that 1 µM of propranolol was too low to completely block β-adrenergic effects of noradrenaline, which might have been released by glucagon from cardiac stores (

Figure 1). Hence, we added increasing concentrations of isoprenaline. We noted that 10 nM of isoprenaline, the same concentration we used for glucagon, was ineffective at raising the beating rate. Even 100 nM of isoprenaline did not raise the beating rate (

Figure 7A). Only 1 µM of isoprenaline augmented the beating rate (

Figure 7A). Hence, release of noradrenaline is unlikely to explain the positive chronotropic effects of glucagon under our experimental conditions. In some species, including mice, glucagon might raise cAMP levels by inhibiting the activity of phosphodiesterases [

27,

28]. However, when we gave rolipram, a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, additionally applied glucagon could still augment the beating rate (

Figure 7B). As a further control, we applied in separate experiments increasing concentrations of the unselective phosphodiesterase inhibitor 3-isobutyl-methylxanthine (IBMX). In addition to phosphodiesterase 4, this drug also inhibits phosphodiesterase 2 and phosphodiesterase 3 [

29]. However, while IBMX alone was able to augment the beating rate (

Figure 7C), additional glucagon was still able to raise the beating rate further (

Figure 7C). This means 10 nM of glucagon was able to enhance the beating rate by 78 ± 12% (

n = 5,

p < 0.05) compared to the pre-glucagon values (this is 3 µM of IBMX). This finding is inconsistent with the hypothesis that glucagon acts via inhibition of phosphodiesterases [

27]. We have used 100 nM of rolipram and 3 µM of IBMX before in mouse right atrial preparations to raise the beating rate [

30]. Others have reported that phosphodiesterase inhibitors can in principle heighten the positive inotropic effect of glucagon in rat ventricular preparation. Hence, cardiac effects of glucagon can be augmented by phosphodiesterase inhibitors, at least in some species [

30]. There is evidence from other groups that, in principle, phosphodiesterases can act locally on subcellular compartments of cAMP; this mechanism may come into play under our experimental conditions [

31,

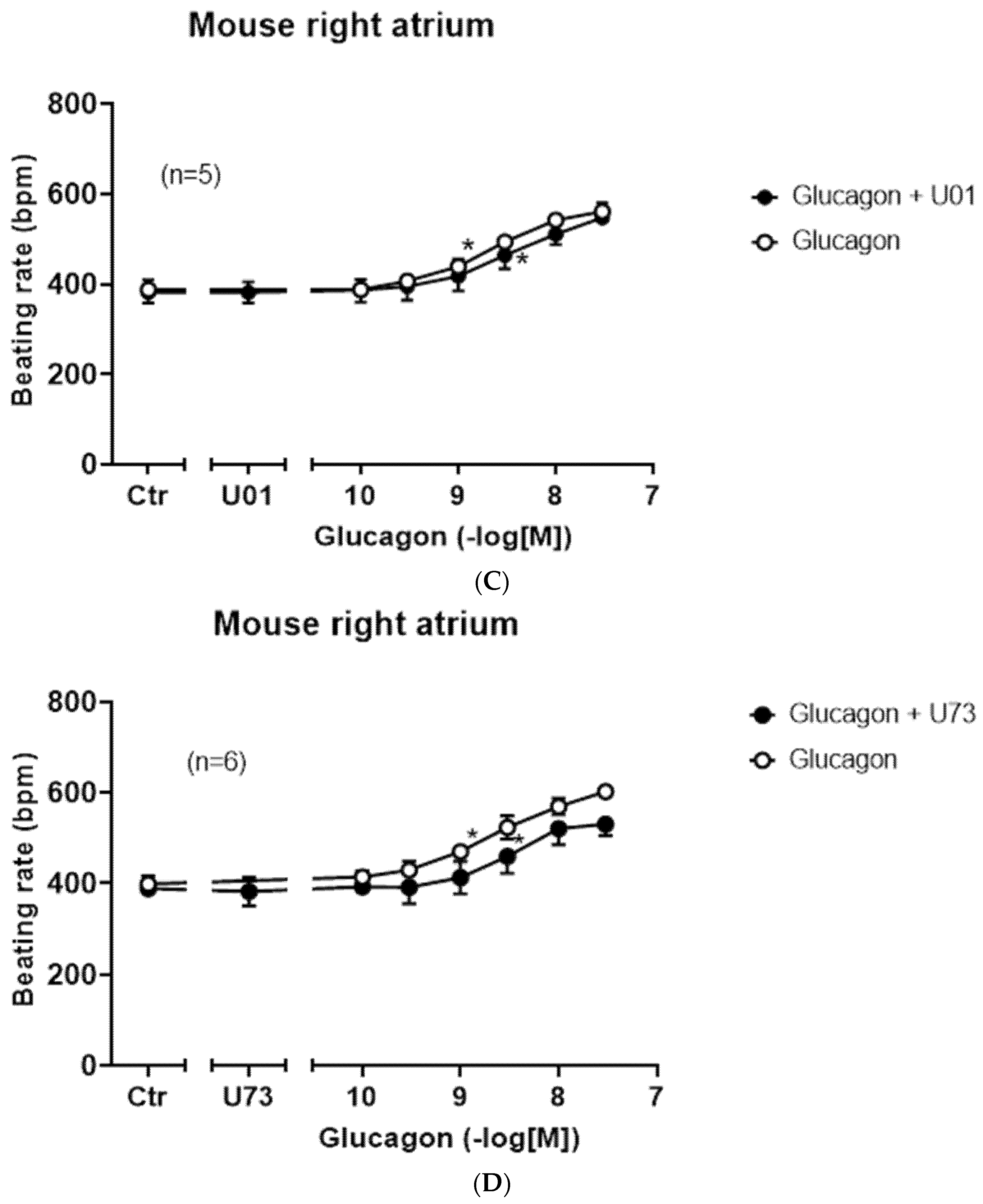

32]. Moreover, one can ask how glucagon acts, if the right atrium is not beating spontaneously. These right atrial preparations that failed to beat spontaneously were electrically stimulated. Here, the beating rate was set at 60 beats per minute (

Figure 7D, lower ordinate). Under these conditions, the electrically stimulated right atrial preparation generated force of contraction (

Figure 7D, upper ordinate). When we added increasing concentrations of glucagon that would augment the beating rate in spontaneously beating right atrial preparations (cf.

Figure 6B), we did not observe any augmentation in the force of contraction. As a positive control, we next added isoprenaline. Isoprenaline, as expected, raised the force of contraction (upper ordinate), indicating that the mouse right atrium has intact β-adrenoceptors, which, when isoprenaline is added, can elevate force. Please also note that the isoprenaline-induced short-lasting, spontaneous contractions which appear as arrhythmias in the lower ordinate tracing of

Figure 7D. In summary, 100 nM of glucagon did not alter the force of contraction in electrically stimulated right atrial preparations of adult mice (amounting 102 ± 9% of pre-glucagon value,

p > 0.05,

n = 5).

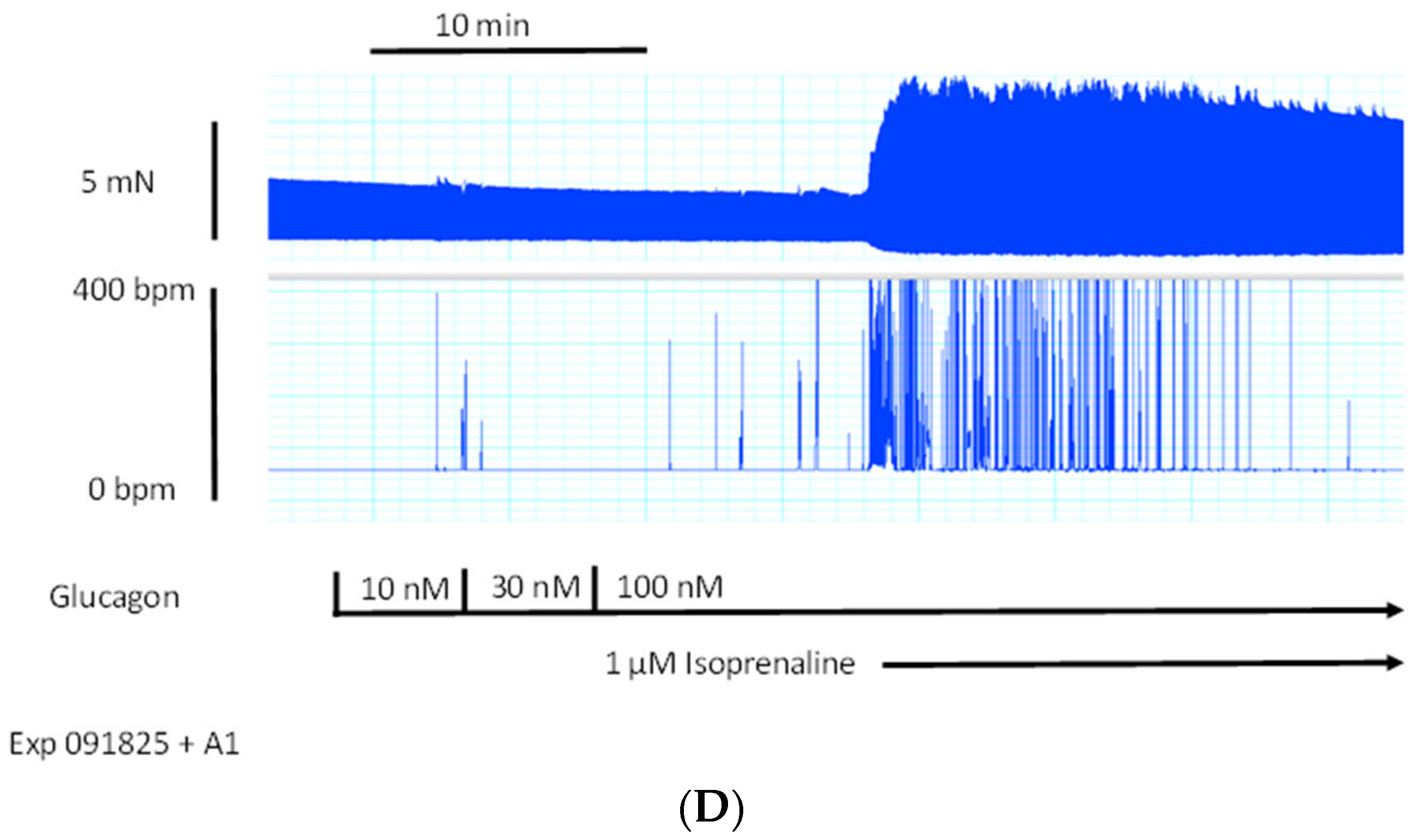

Next, one can question via which ion channel glucagon augmented the beating rate in right atrial preparations.

One likely target, based on the work of others, is the HCN channel, which causes the funny current (

Figure 1, I

f-current, rat: [

33]). We chose an HCN channel inhibitor that is an approved drug (against certain forms of chest pain and heart failure), namely ivabradine (1 µM), which we have studied before in mice at this concentration [

34]. These results are summed up in

Figure 8A. Ivabradine attenuated the effect of glucagon. This can be seen in

Figure 8A as a rightward shift of the concentration response curve to glucagon after pre-incubation with 1 µM of ivabradine (

Figure 8A). This suggested to us that the positive chronotropic effect of glucagon is mediated, at least in part, by the HCN channels. The cAMP in the right atrium may directly open HCN channels, independently of any phosphorylation of the HCN channels. However, there are reports to the opposite, in which the cAMP-dependent protein kinase may phosphorylate HCN channels [

35]. Therefore, we tested the effect of H89, an inhibitor of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase (

Figure 8B). Under our experimental conditions, the positive chronotropic effect of glucagon was not attenuated by H89. We have used H89 successfully before to inhibit the activity of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase in the mouse atrium [

36]. There are reports that a MAP kinase (MAPK) might mediate biochemical effects of GCGR [

37]. Hence, we tested a MAPK inhibitor, which we have used before at this concentration [

38], namely 10 µM of U0126 (

Figure 1). However, the positive chronotropic effect of glucagon was not affected by pre-incubation for 10 min with 10 µM of U0126, and thus MAPK does not appear to be involved (

Figure 8C). Others have reported that glucagon might stimulate the activity of phospholipase C (hepatocytes: [

39]). However, 10 µM of U73122, which we used successfully before at this concentration in mouse atria [

38], did not attenuate the positive chronotropic effects of glucagon in isolated right atrial preparations from adult wild-type hearts (

Figure 8D).

Moreover, the question arose of whether the positive chronotropic effects of glucagon were only seen in isolated right atrial preparations or were a phenomenon also noticeable in more clinically relevant, more physiological preparations. Hence, we infused glucagon retrogradely via the coronary arteries into the isolated spontaneously beating mouse heart (Langendorff heart:

Table 1). The main result was that, as in the isolated right atrium, in the whole mouse heart, glucagon also augmented the beating rate (

Table 1). Here, we performed a post hoc power analysis. We calculated the power to detect an augmentation in the beating rate of 98%. Interestingly, the contractile data in the left atrium agree with the contractile data in the mouse right atrium: in the same isolated mouse hearts where glucagon raised the beating rate, glucagon also reduced the force of contraction (

Table 1). This can be explained by the negative staircase (“Treppe”) phenomenon: a rise in beating rate per se attenuated the force of contraction in the left ventricle of the adult mouse heart under our experimental conditions. We also noted in the whole perfused heart that glucagon reduced the time to peak tension and time to relaxation (

Table 1). Finally, we studied the gene expression of the GCGR in the regions of the mouse heart. The expression was highest in the right atrium, hardly detectable in the left atrium and small in the mouse ventricle (

Figure 9).

Here, we also performed a post hoc power analysis. We calculated a power of 99% to detect an increase in the amount of mRNA for the GCGR between LA and RA.

3. Discussion

The main new finding of this report is that glucagon exerts a positive chronotropic effect via GCGR in adult mouse right atrial preparations. One can ask why glucagon raised the beating rate but not the force of contraction in spontaneously beating right atrial preparations of adult mice, whereas isoprenaline could augment the beating rate and force under these conditions. It is conceivable that the GCGR is only present in the sinus node, whereas the β-adrenoceptors are present in the sinus node and in the remainder of the right atrium. This view is supported by our studies in paced right atria (

Figure 7D). Another major finding was that also in left atrial preparations, we failed to find a positive inotropic effect of glucagon, whereas under the same experimental conditions, isoprenaline elevated the force of contraction. These findings are difficult to reconcile with the mechanism plotted in

Figure 1. Why should glucagon augment cAMP only in the right atrium and not in the left atrium? A rise in cAMP in the right atrium explains any augmentation in activity of the HCN and thus the climbing of the beating rate in the right atrium (

Figure 1). A rise in cAMP in the left atrium should activate the regulatory proteins responsible for force generation in the left atrium. However, this finding is not without precedence: prostaglandin E1 raised cAMP in kitten hearts and beating rate but not force of contraction, which might have been caused by subcellular compartments of cAMP [

40].

It merits some thoughts why glucagon failed to elevate the force of contraction in adult mouse left atrial preparations. The action of glucagon in the left atrium probably does not lead to an augmentation of cAMP-levels in contrast to the sinus node but may use a different signal transduction pathway. Alternatively, the GCGR might not be expressed in the cardiomyocytes of the mouse left atrium but in other left atrial cells, for instance in endothelial cells. Consistently, we measured only small amounts of GCGR in the left atrium, which might indicate a very low or absent expression of GCGR in cardiomyocytes (

Figure 9). But this GCGR might be located on endothelial cells, and thus it cannot raise cAMP in left atrial cardiomyocytes. This would explain why glucagon does not augment the force of contraction in adult mouse left atrial preparations. Interestingly, not only in the mouse left atrium (this paper) but also in the rat left atrium, glucagon failed to raise the force of contraction [

33]. Hence, this lack of left atrial inotropy to glucagon may be a general phenomenon in rodents. As concerns the mechanism underlying the positive chronotropic effect of glucagon, we would like to mention that we had studied ivabradine before in mouse right atrial preparations and noted a negative chronotropic effect [

34]. In extension, here ivabradine attenuated the positive chronotropic effect of glucagon. From our present data, we assume that glucagon acts in the sinus node of adult mice via stimulation of HCN channels. This stimulation of HCN channels then would elevate the heartbeat. This glucagon-stimulated heartbeat was reversed by carbachol and R-PIA. In other species than mice, glucagon exerts a positive inotropic effect in cardiac preparations. For instance, the positive inotropic effects of glucagon in the isolated canine ventricle were antagonized by carbachol or acetylcholine; however, the effects of glucagon on the spontaneous beating rate of the canine right atrium were not reported [

41,

42]. As another example, in rat ventricular cells, acetylcholine could reduce the glucagon-stimulated current through the L-type calcium ion channel [

28]. Hence, a cardiac antagonism between glucagon and acetylcholine is not without precedence in the mammalian heart. Here, a further new finding is that such an antagonism is also present in the mammalian sinus node. The observation that carbachol reduced the positive chronotropic effect of glucagon in mouse right atrial preparations suggests that this interaction is similar to that in rat ventricular cardiomyocytes or canine ventricle. Hence, we extend previous findings to a new species (mouse) and a new tissue (atrium) and other contractile parameters (beating rate). It is now well known that acetylcholine can be produced in the heart [

43]. Thus, in a paracrine way, cardiac acetylcholine might reduce conceivably detrimental glucagon-induced tachycardia in mice. As far as we know, it is a further novel finding that an A

1-adenosine receptor agonist like R-PIA can reduce any glucagon-induced effect in mammalian sinus nodes. However, this is biochemically not without precedence in other tissue: R-PIA inhibited glucagon-stimulated activity of adenylyl cyclase in rat Sertoli cells and in hepatic cells [

44,

45,

46]. Hence, in principle, an interaction of the A

1-adenosine receptor and the GCGR seems to exist and is now extended to the mouse sinus node. Like acetylcholine, adenosine is also produced in the heart [

47]. This production of cardiac adenosine rises in ischemia and reperfusion. Hence, our findings (

Figure 5B) open the possibility that adenosine like acetylcholine offers a protection against the putative detrimental tachycardia caused by glucagon, especially in cardiac ischemia. As concerns the signal transduction in the sinus node of mice, our data would argue for an involvement of cAMP at the HCN channel but do not support an action via the cAMP-dependent protein kinase because H89 was without effect (

Figure 9). Likewise, the positive chronotropic effects of glucagon in adult mice are probably not mediated via MAPK (

Figure 9). Likewise, we failed to detect evidence for an involvement of phospholipase C in the positive chronotropic effects of glucagon (

Figure 9).

Of note, we show here that glucagon not only acted in the isolated mouse right atrium. Importantly, glucagon also elevated the beating rate in isolated perfused mouse hearts (

Table 1). This might be interpreted as being consistent with a positive chronotropic effect of injected glucagon in living mice. This is mechanistically interesting, as our data would argue that there is also a direct cardiac effect of glucagon in living mice. However, there is GCGR in the brain, and our data do not rule out that this brain GCGR also contributes to a positive chronotropic effect of injected glucagon in living mice. One has to admit that the concentrations of glucagon we used are elevated and thus here represent pharmacological concentrations; i.e., these concentrations are much higher than the physiological concentrations of the glucagon that are found in humans or experimental animals (around 10 pM [

15]). However, like us, many other groups used nanomolar or even micromolar concentrations of glucagon to elicit a positive chronotropic or positive inotropic effect in other species [

13,

33,

48].

We have recently reported that glucagon alone had no positive inotropic effect in human atrial preparations. However, in the presence of a phosphodiesterase inhibitor 3 inhibitor, namely cilostamide, glucagon augmented the force of contraction in human atrial preparations [

49]. Actually, this finding was one reason why we studied phosphodiesterase inhibitors here. We had shown that only in the presence of rolipram (a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor; phosphodiesterase 4 is the main phosphodiesterase in the mouse heart, and phosphodiesterase 3 is the main phosphodiesterase in the human heart) did some drugs exert positive inotropic effects. This is probably the case because phosphodiesterase inhibitors induced a rise in cAMP in such a way that even small further increases in cAMP by receptor stimulation can add up to a positive inotropic effect. This seems to be the case in the human atrium. Another issue is that human right atrial preparations, which we routinely study, very rarely beat spontaneously. In such rare cases, we noted in human right atrial preparations from patients suffering from persistent atrial fibrillation that their isolated right atrial preparations (which do not include the human sinus node) initially beat spontaneously. However, usually after three times of changing the buffer in the organ bath, which is our standard procedure, the isolated human right atrial preparations stopped beating on their own, and we had to start to pace them. In short, we could not study sinus node function in our isolated human right atrial preparations. Hence, we studied as a surrogate parameter the sinus node function in the right atrium of the mouse heart.

Furthermore, the present data give a plausible reason why we failed to detect a positive inotropic effect in the left atrium of the mouse heart: the mRNA of the glucagon receptor is very low in the mouse left atrium. In contrast, others have published that the mRNA of the glucagon receptor is present in human right atrial samples. Indeed, as just mentioned, we measured a positive inotropic effect of glucagon in the presence of cilostamide in human right atrial preparations. Hence, in humans, the functionally active GCGR is apparently present in high levels on cardiomyocytes in the human right atrium (and not endothelial cells). Thus, glucagon can elevate the force in isolated human right atrial muscle preparations even outside the sinus node [

50]. Hence, we would argue that the inotropic effect in the human atrium of glucagon can be explained by high regional GCGR expression in cardiomyocytes. The most straightforward explanation for the lack of a positive inotropic effect of glucagon in the mouse left atrium is the very low expression of the glucagon receptor, and this expression might be confined to endothelial cells. The situation might be different in the mouse right atrium: we detect high levels of mRNA for glucagon receptor in the right atrium (

Figure 9). We note a positive chronotropic effect of glucagon in the mouse right atrium but interestingly no positive inotropic effect in the paced mouse right atrium. This may mean that the GCGR is only expressed in the sinus node in the mouse right atrium and not in the remaining muscle part of the right atrium (which is different qualitatively and quantitatively from the human expression, as discussed above).

Clinical relevance: It is probable that pharmacological concentrations of glucagon can induce a direct positive chronotropic effect in humans. This effect is probably GCGR-mediated. Thus, there might be a clinical perspective to our present studies in mice. We have shown that glucagon augmented the force of contraction in the isolated electrically human right atrial muscle strips via GCGR, and hence such a pathway exist, in principle [

49]. Thus, glucagon might act directly on the human heart via GCGR to augment force and beating rate. However, this is still controversial and merits further work, e.g., with human-pluripotent-stem-cell-derived cardiomyocytes, whether glucagon can directly elevate the heartbeat in the human heart.

Limitations of the study: We did not have the opportunity to measure the expression of the GCGR in the sinus node of mice and compare this expression with the expression of the GCGR in the remainder of the right atrium of the adult mouse. We have not been able to measure the effects of glucagon on cAMP microdomains in the mouse right atrial cardiomyocytes or sinus node cardiomyocytes. We have not yet measured whether glucagon raised the If-current in the sinus node of adult mice. Hence, due to our technical boundaries, we cannot prove with certainty the signal transduction of the GCGR in the mouse sinus node. Moreover, we have not removed the sinus node in control experiments on isolated perfused hearts and then measured pressure in the left ventricular with external pacing to understand the role of glucagon in the ventricle more definitely. In addition, one might isolate ventricular cardiomyocytes from adult wild-type mice, pace them electrically and then study the effect of glucagon on contractility. As other control experiments for future studies, it would be useful to pre-treat living mice with reserpine or 6-hydroxy-dopamine to empty cardiac noradrenaline stores. Finally, we have not yet performed comparison contraction experiments on right atrial preparations from adult mice with a cardiac or general GCGR deletion. If our assumption of a GCGR-mediated effect of glucagon is valid, in these mice lacking GCGR, glucagon should not lead to a positive chronotropic effect.

In conclusion,