Abstract

As a widely sourced solid waste rich in metallic elements such as Fe, Zn, Mn and Ca, electric furnace dust serves as a crucial raw material for preparing catalytic materials. This study employed a three-step process—“acid/alkali modification–impregnation–calcination”—to synthesise an electric furnace dust-based magnetic heterogeneous catalyst for biodiesel production. The catalyst prepared via CH3ONa modification combined with Na2CO3 impregnation achieved stable cycling performance at low temperatures, with 14 cycles yielding a consistent conversion exceeding 93.44 wt%, demonstrating exceptional catalytic activity. The CH3ONa modification generates abundant reactive oxygen species on the furnace dust surface, facilitating the binding of hydroxyl oxygen from the active component (Na+) to the modified surface (EFD/CH3ONa) and thereby anchoring the active species. However, the decline in catalytic performance of the Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa) catalyst after calcination at 600 °C (yield decreasing to 69.77 wt% after 11 stable cycles) was attributed to the detachment and agglomeration of the active component sodium at elevated temperatures. This paper employed electric furnace dust as feedstock to synthesise highly active and stable magnetic multiphase catalysts, thereby not only providing an environmentally sound pathway for industrial solid waste recycling but also offering novel insights for the industrial-scale production of biodiesel.

1. Introduction

The swift growth of the global population, the accelerated pace of industrialisation, and the continuous rise in economic standards have intensified the consumption of fossil fuels, precipitating severe issues such as resource depletion, energy shortages, and exorbitant greenhouse gas discharges [1,2]. To mitigate these problems, the identification and development of renewable green energy sources have become particularly crucial. Biodiesel, due to its low greenhouse gas discharges, biodegradability, and renewable attributes, has become a sustainable substitute to fossil fuels [3,4,5]. Biodiesel is usually manufactured as fatty acid methyl ester (FAME) via transesterification of vegetable oils or animal fats with short-chain alcohols in the presence of acid or alkaline catalysts. Currently, owing to its excellent fuel properties, it is widely utilised in diesel engines [6]. However, selecting an appropriate catalyst is pivotal for achieving efficient and cost-effective biodiesel production. Presently, the catalysts applied in the industrial production of biodiesel largely comprise homogeneous and heterogeneous varieties. Whilst homogeneous catalysts (such as NaOH and H2SO4) offer advantages, including high catalytic activity and mild reaction conditions, these materials are difficult to separate from the products. By comparison, heterogeneous catalysts, on account of their incompatibility with the products, are more readily separable and reusable, making them the preferred catalysts for sustainable biodiesel synthesis [6]. Metal-based solid wastes, due to their wide availability, suitable pore structures, and tunability, are extensively utilised as adsorbents and catalysts in synthetic energy production. However, conventional separation methods (such as centrifugation and filtration) pose significant challenges for catalyst recovery when handling extremely fine-grained heterogeneous catalysts. To minimise losses during heterogeneous catalyst recovery and enhance catalyst stability, magnetic catalysts have emerged as promising materials. Their responsiveness to external magnetic fields enables straightforward and efficient separation with reduced mass loss [7].

Electric furnace dust, as an industrial waste product, contains substantial quantities of Fe, Zn, Mn and Ca oxides alongside minor amounts of free metals. These constituents can catalyse a variety of reactions [8,9], making it a rich source material for the preparation of magnetic catalytic materials. Amdeha et al. [10] pioneered the fabrication of ordered mesoporous silica (MCM-41), nano-zinc oxide (ZnO), and zinc sulphide (ZnS) with blast furnace slag (BFS) and electric furnace dust (EFD) serving as raw materials. These substances were used as composite photocatalysts, exhibiting effective photoreduction activity for highly toxic chromium(VI) and less toxic chromium(III) under ultraviolet irradiation. Wang et al. [11] utilised electric furnace dust as feedstock to prepare an acid–base dual-functional heterogeneous catalyst via sodium carbonate impregnation for catalysing biodiesel production from soybean oil. Under optimised conditions, the initial biodiesel yield reached 99.8 wt%, and after 11 cycles, the yield remained above 90 wt%, demonstrating exceptionally high catalytic activity and stability.

Moreover, electric furnace dust treated through acid leaching, alkali leaching, and similar processes may exhibit favourable carrier properties, such as suitable morphological structure and high specific surface area. The addition of acid enhances the affinity of metal oxides within the dust [12], thereby facilitating the adhesion of active components. The modified dust exhibits an increased specific surface area, generating abundant active sites that enhance the catalytic stability of electric furnace dust [13]. Common alkali-modifying reagents include NaOH, KOH, and NH3·H2O. Following alkali solution modification, the pore structure and local environment on both the internal and external surfaces of the dust undergo significant alteration [14]. This process generates a large number of oxygen functional groups [12] while introducing alkaline sites [15], thereby further enhancing the catalytic efficiency for biodiesel production. Moreover, alkali modification can effectively reduce ash content and impurities in the dust, thereby increasing the proportion of active components within it. The impregnation method is one of the most commonly employed techniques for preparing supported catalysts. During impregnation, the catalyst support and active components are immersed in a solution. The active components not only adhere to the support surface but also penetrate into the pores of the support via capillary action, thereby forming catalytic materials with high catalytic activity [16]. By adjusting the impregnation temperature, impregnation amount, and impregnation time, the distribution of active components over the catalyst support can be regulated. The more uniform the distribution of these active components, the more conducive it is to enhancing the catalyst’s activity and stability. Catalyst calcination involves high-temperature heating to remove organic matter, moisture, and other impurities from the catalyst. The calcination process influences the catalyst’s surface morphology, structural characteristics, and the dispersion of active sites [17]. Optimising the calcination temperature of materials enables effective modulation of the surface properties of catalysts, thereby further enhancing catalytic activity [18]. To date, no researchers have applied electric furnace dust as a raw material to prepare heterogeneous catalysts that facilitate the production of biodiesel from fats and oils by means of the “acid/alkali modification–impregnation” method.

Hence, this chapter explores the influence of acid–base modification on the catalytic activity of electric furnace dust, with the dust serving as raw material. Employing a combined impregnation–high-temperature calcination method, it examines changes in the chemical composition and structural characteristics of both the original and modified electric furnace dust during the activation process, thereby elucidating the activation mechanism. The final optimised synthetic catalyst exhibits high catalytic activity and satisfactory stability, making it appropriate for catalysing biodiesel production from fats and oils.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Preparation of EFD/S Precursor from Acid/Alkali-Modified Electric Furnace Dust

Characterisation via inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES) and elemental analysis revealed the following metal element contents in the EFD studied: Fe, Zn, Mn, Ca, Si, Mg, and Na at 38.65, 11.54, 4.78, 4.63, 3.26, 1.74, and 1.71 wt%, respectively. The C, H, and S contents in the EFD raw material were 1.61, 0.43, and 0.59 wt%, respectively.

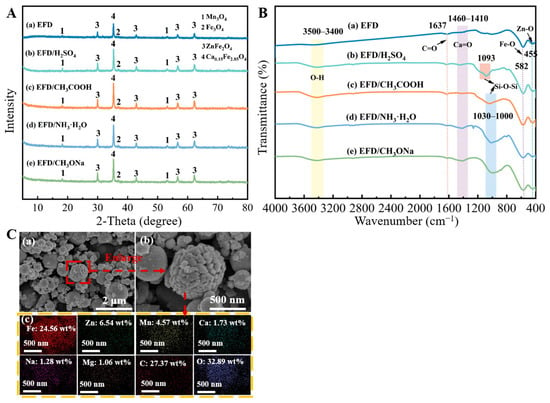

Under the conditions of a reaction temperature of 65 °C, a reaction time of 2 h, 7 wt% catalyst dosage, and 15/1 alcohol/oil molar ratio, electric furnace dust was directly employed as a catalyst to catalyse soybean oil, and the obtained biodiesel yield was 0.3 wt%. To explore the influence of acid–base modification on the catalytic activity of EFD feedstock, EFD was modified as a catalyst using hydrochloric acid, sulfuric acid, nitric acid, phosphoric acid, sodium hydroxide, potassium hydroxide, ammonia water, acetic acid, oxalic acid, malic acid, citric acid, sodium methoxide, potassium methoxide, and sodium ethoxide, respectively. Under identical conditions, the biodiesel yield from the catalysis of soybean oil was merely 0.1~3.6 wt%. To investigate the effects of acid (or alkali) modification on the chemical composition and structural properties of EFD, characterisation analyses were conducted on both unmodified and modified EFD using X-ray diffractometer (XRD), field-emission scanning electron microscope equipped with an energy-dispersive spectrometer (SEM-EDS), Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FT-IR), X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (XPS), Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET), thermogravimetric analyser (TG), and vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM). The EFD raw material comprises mineral phases such as Mn3O4, Fe3O4, ZnFe2O4 and Ca0.15Fe2.85O4 (Figure 1A(a)). The spinel-structured ZnFe2O4 [19] exhibited high-intensity diffraction peaks at multiple angles, including 2θ = 29.8°, 42.9°, 56.7° and 62.3°, indicating that Fe and Zn in the EFD raw material predominantly existed in the form of ZnFe2O4. Mn3O4 appeared at 2θ = 18.3° and 53.4°, while Ca0.15Fe2.85O4 appears at 2θ = 35.4°. Additionally, a low-intensity diffraction peak corresponding to the Fe3O4 (311) crystal plane was detected at 2θ = 35.4° [20], which also explained the magnetic properties exhibited by the electric furnace dust. Following modification of EFD with H2SO4, CH3COOH, NH3·H2O and CH3ONa, no new mineral phases were detected. However, it was evident that following acid (or alkali) modification, the intensities of the ZnFe2O4 and Ca0.15Fe2.85O4 diffraction peaks in the EFD increased significantly (Figure 1A(b–e). This indicated that after acid or alkali treatment, the amorphous oxides or weakly crystalline impurities on the surface of the electric furnace dust were dissolved, resulting in a reduced proportion of amorphous phase components. SEM and EDS analysis of CH3ONa-modified EFD (EFD/CH3ONa) is shown in Figure 1C(a–c). The EFD/CH3ONa sample primarily consisted of irregular spherical particles ranging from 50 to 600 nm in size. Some submicron particles had agglomerated due to electrostatic interactions, forming larger spherical bodies and clusters [21]. Individual spherical particles exhibited a loose, porous surface, likely resulting from reactions between the alkaline solution and metallic dust during the modification process [22]. EDS analysis (Figure 1C(c)) revealed the mass ratios of Na/Fe, Na/Zn, Fe/Mn, Ca/Fe, and Mg/Fe on the surface of the EFD/CH3ONa sample to be 1/19.19 (Na at 1.28 wt% and Fe at 24.56 wt%), 1/5.11 (Zn at 6.54 wt%), 1/0.19 (Mn at 4.57 wt%), 1/14.20 (Ca at 1.73 wt%), and 1/23.17 (Mg at 1.06 wt%). These elements were uniformly distributed throughout the entire detection range.

Figure 1.

(A) XRD patterns and (B) FT-IR spectra of (a) EFD, (b,c) acid-modified EFD, and (d–e) alkali-modified EFD; (C) SEM-EDS spectrum of EFD/CH3ONa. (C) (a,b) SEM images and (c) EDS spectrum of EFD/CH3ONa.

Broad peak bands between 3500 cm−1 and 3400 cm−1 were observed in the FT-IR spectra of both EFD and modified EFD (Figure 1B(a–e)), attributed to the stretching vibrations of O-H groups in water molecules [23]. Bending vibration peaks characteristic of Fe-O [24] and Zn-O functional groups were identified near 582 cm−1 and 455 cm−1, respectively, consistent with XRD analysis. The characteristic peak near 1637 cm−1 corresponded to the C=O group in the carbonyl [25], suggesting the existence of residual organic matter in the EFD. Following acid (or base) modification of the EFD, the resulting EFD/H2SO4, EFD/CH3COOH, EFD/NH3·H2O, and EFD/CH3ONa catalysts exhibited Si-O-Si vibrational peaks near 1090 cm−1, 1028 cm−1, 1018 cm−1, and 1003 cm−1, respectively [26]. This phenomenon was likely attributable to the acid (or base) solution treatment disrupting the external Fe, Zn, and Ca compounds, thereby exposing the internal silicon oxides [27].

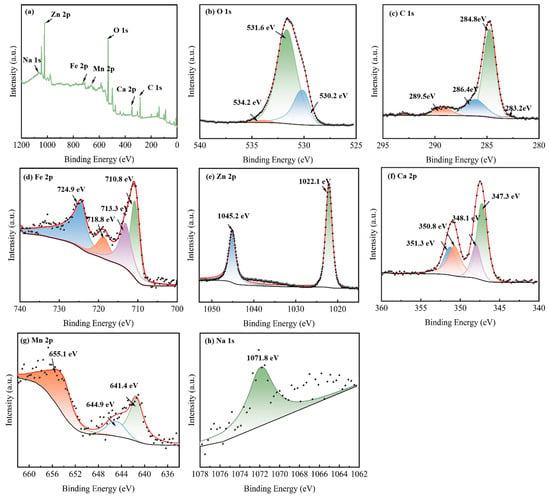

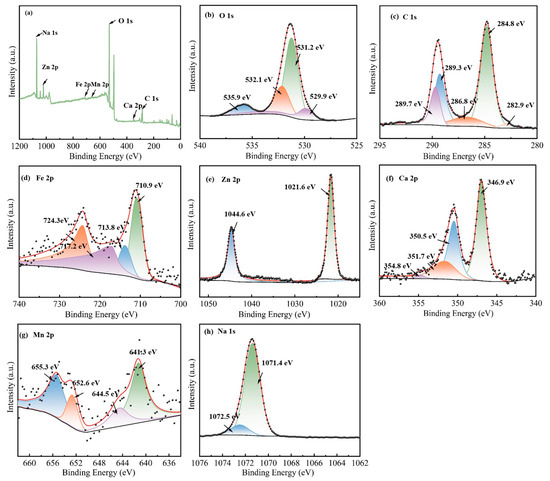

To gain further insight into element composition and chemical states on the surface of modified EFD as a catalytic material, full-spectrum and fine-spectrum XPS analyses were conducted on the EFD/CH3ONa sample. All binding energy data were charge-corrected against the standard peak at 284.8 eV for C 1s. In the full XPS spectrum (Figure 2a), EFD/CH3ONa was primarily composed of Na 1s, Zn 2p, Fe 2p, Mn 2p, O 1s, Ca 2p, and C 1s peaks. As shown in Figure 2b, the O 1s spectrum exhibited three distinct peaks with binding energies of 530.2 eV, 531.6 eV, and 534.2 eV, corresponding to lattice oxygen (OL), O2− in oxygen vacancies (OV), and surface hydroxyl oxygen (-OOH), respectively. These lattice oxygen and oxygen vacancy sites constituted the critical active constituents enhancing catalytic performance and electron transport capacity [28]. The C1s spectrum exhibited three distinct peaks with binding energies of 284.8 eV, 286.4 eV, and 289.5 eV (Figure 2c), associated with the C-C/C=C [29], C-O [30], and C=O [29] functional groups, respectively, in EFD/CH3ONa. In Figure 2d, the Fe 2p peaks near 710.8 eV, 713.3 eV, and 724.9 eV correspond to Fe-C/Fe, Fe3+, and Fe2+, respectively, indicating the simultaneous presence of Fe3O4 and Fe2O3 in the sample. A satellite peak of Fe 2p appeared at a binding energy of 718.8 eV [31], confirming the presence of Fe3+ or Fe2+ oxidation states in the sample. The high-resolution spectrum of the Zn 2p (Figure 2e) displayed two characteristic peaks at 1022.1 eV and 1045.2 eV, matching the spin–orbit peaks of ZnO’s Zn 2p3/2 and Zn 2p1/2, respectively [32]. For EFD, due to spin–orbit coupling, the Ca 2p region showed two peaks at 348.6 eV and 350.8 eV, matching Ca 2p1/2 and Ca 2p3/2, respectively, as shown in Figure 2f, both indicating the presence of calcium in the material as Ca2+ [30]. As depicted in Figure 2g, in the high-resolution Mn 2p XPS spectrum for EFD/CH3ONa, a sharp peak was observed at 641.4 eV, assigned to Mn 2p3/2. Deconvolution of this peak uncovered two separate peaks at 641.4 and 644.9 eV, which correspond to Mn2+ and Mn3+, respectively [33]. A characteristic peak at 1071.8 eV was fitted for Na 1s, indicating the presence of Na+ in the sample [34].

Figure 2.

XPS spectra of EFD/CH3ONa: (a) total spectrum, (b) O 1s, (c) C 1s, (d) Fe 2p, (e) Zn 2p, (f) Ca 2p, (g) Mn 2p, and (h) Na 1s.

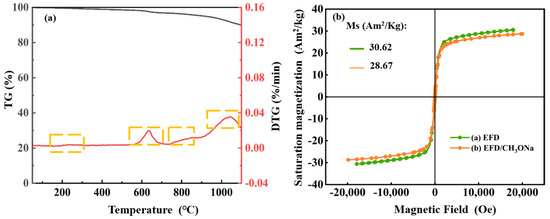

To explore the thermal stability of the EFD/CH3ONa material, TG-DTG analysis was conducted over the range of temperatures for 0–1100 °C, with results presented in Figure 3a. The entire heating process could be subdivided into four distinct stages of mass loss. During the first stage, with the temperature increasing from ambient temperature to 300 °C, a slight decrease in mass was observed for EFD/CH3ONa. This was primarily attributed to the removal of entrapped free water within the sample [35]. In the second stage, as the temperature rose to the 600–700 °C range, a marked acceleration in weight loss occurred (1.48 wt%), attributable to mass loss stemming from the vaporisation of chlorides in EFD/CH3ONa or the decomposition of organic matter (confirmed by FT-IR) [36]. In the third stage, as temperature continued to rise, a gradual weight loss occurred between 750 and 900 °C. This could be attributed to the carbothermal reduction of metal oxides within the sample [37], releasing gases such as carbon monoxide. The fourth stage, occurring when temperatures exceeded 1000 °C, saw the sample lose approximately 3.05 wt% of its mass. This phase likely represented the decomposition of Ca0.15Fe2.85O4 (consistent with XRD results) at elevated temperatures, releasing minor quantities of oxygen. Additionally, the magnetic characteristics of the catalytic material constituted a significant factor influencing catalyst stability. The VSM results are presented in Figure 3b. The hysteresis loops of the samples measured before and after CH3ONa modification exhibited symmetrical “S”-shaped curves, demonstrating superparamagnetic characteristics [38]. The saturation magnetisation of EFD and EFD/CH3ONa was 30.62 Am2/kg and 28.67 Am2/kg, respectively. The modified EFD exhibited a slight decrease in magnetic properties, potentially attributable to alterations in the relative content of internal Fe3O4 following CH3ONa modification. For instance, Fe3O4 might undergo hydrolysis within the alkaline environment of CH3ONa, yielding weakly magnetic iron hydroxide (FeOOH) or non-magnetic ferrites.

Figure 3.

(a) TG-DTG curves of EFD/CH3ONa and (b) VSM curves of EFD and EFD/CH3ONa.

2.2. Preparation of M&(EFD/S) Catalyst by Metal Salt Impregnation Activation of EFD/S

The modified samples did not exhibit enhanced catalytic activity compared to the raw EFD material. However, following modification, the EFD/S samples demonstrated varying degrees of improvement in both specific surface area and the chemical environment of surface elements, suggesting potential as a catalyst precursor. Therefore, this section employed EFD as a precursor both before and after acid (or base) modification. Using metal salts as active agents, the active substances were loaded onto the modified and unmodified EFD via impregnation. The influence of metal salt type on catalytic activity was subsequently investigated.

Select CdCO3, BaCO3, Li2CO3, Na2CO3·10H2O, NaHCO3, K2CO3, CH3ONa, C2H5ONa, CH3OK, Na2CO3, and other activators to treat electric furnace dust. Under the conditions of 65 °C reaction temperature, 2 h reaction time, 7 wt% catalyst dosage, and 15/1 alcohol/oil molar ratio, soybean oil was catalysed to produce biodiesel; the resulting yields exhibited significant variation when catalysing the conversion of soybean oil into biodiesel (Table 1). The first-cycle biodiesel yields catalysed by CdCO3, BaCO3, and Li2CO3-impregnated electric furnace dust were 0.8, 0.7, and 4.2 wt%, respectively. Compared with the original electric furnace dust (with an initial catalytic yield of 0.3 wt%), the catalytic activity did not show a significant improvement. Catalysts prepared using the same method—Na2CO3·10H2O&EFD, NaHCO3&EFD, K2CO3&EFD, CH3ONa&EFD, C2H5ONa&EFD, CH3OK&EFD, and Na2CO3&EFD—exhibited substantially enhanced catalytic activity. Their first-cycle yields reached 66.6 wt%, 88.0 wt%, 92.7 wt%, 89.8 wt%, 84.3 wt%, 94.4 wt%, and 85.6 wt%, respectively. However, their cycling stability proved inadequate, with only Na2CO3&EFD maintaining a yield of 88.6 wt% after the second cycle. It should also be noted that the biodiesel yield increased following the second catalytic cycle. This may be attributed to the activation of active sites on the catalyst surface through interaction with the substrate (methanol or fatty oils), leading to the formation of more stable active centres. This phenomenon was consistent with the findings reported by Wang et al. [11]. Consequently, Na2CO3 was chosen as the optimal activator for the subsequent optimisation of activity.

Table 1.

Biodiesel production from soybean oil catalysed by M&EFD.

A series of Na2CO3&(EFD/S) catalyst systems was prepared using acid (or base)-modified EFD as the precursor, activated via Na2CO3 impregnation. The study investigated the combined effect of different acid (or base) modifiers with Na2CO3 impregnation on catalyst activity and stability. Under identical catalytic conditions, the yields from soybean oil catalysis are presented in Table 2. The catalytic performance of acid (or base)-modified EFD exhibited a more pronounced enhancement following impregnation. During the initial cycle, all modified EFD achieved a biodiesel yield of 100.0 wt%. Cycling experiments revealed that catalysts such as Na2CO3&(EFD/HCl), Na2CO3&(EFD/HNO3), Na2CO3&(EFD/NaOH), Na2CO3&(EFD/H2C2O4), and Na2CO3&(EFD/C2H5ONa) catalysts maintained relatively high biodiesel yields throughout the cycles. However, by the seventh cycle, yields abruptly declined to 49.4 wt%, 75.1 wt%, 53.7 wt%, 51.5 wt% and 12.1 wt%, respectively. The biodiesel yields catalysed by Na2CO3&(EFD/H2SO4), Na2CO3&(EFD/H3PO4), Na2CO3&(EFD/KOH), Na2CO3&(EFD/NH3·H2O), Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3COOH), Na2CO3&(EFD/C4H6O5) and Na2CO3&(EFD/C6H8O7) decreased to 65.8 wt%, 70.2 wt%, 33.2 wt%, 66.0 wt%, 60.0 wt%, 50.7 wt%, and 60.1 wt% in the 8th, 9th, 10th, 10th, 11th, 9th, and 9th cycles of reuse, respectively, exhibiting excellent catalytic stability. More surprisingly, catalysts prepared by impregnating sodium carbonate with a combination of sodium methoxide and potassium methoxide modifications—namely Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa) and Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3OK)—achieved yields exceeding 90.0 wt% across twelve cycling tests. The former maintained a yield of 93.4 wt% even after 14 catalytic cycles, demonstrating optimal cycling stability while retaining high catalytic activity.

Table 2.

Biodiesel production from soybean oil catalysed by Na2CO3&(EFD/S).

To investigate the changes in chemical composition and structural characteristics of EFD and EFD/CH3ONa during the activation process and elucidate the activation mechanism, the samples underwent detailed characterisation analysis employing a combination of XRD, SEM-EDS, BET, XPS, FT-IR, and VSM techniques.

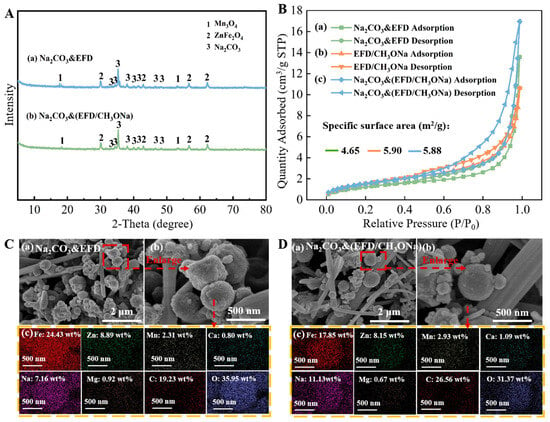

Figure 4A(a,b) displays the XRD patterns of the Na2CO3&EFD and Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa) catalysts, investigating changes in their crystalline compositions. As observed in Figure 4A(a), following Na2CO3 impregnation, the sample exhibited Na2CO3 diffraction peaks at 2θ = 33.4°, 34.5°, 35.3°, 37.9°, 39.9°, 41.5°, 46.4°, and 48.4° [39,40]. Additionally, the original Ca0.15Fe2.85O4 crystalline phase in EFD disappeared without the formation of any new substances, indicating that Na2CO3 may have adsorbed onto the EFD surface in crystalline form. Further analysis using the BET method examined changes in the specific surface area and pore structure of EFD and EFD/CH3ONa before and after Na2CO3 impregnation (Figure 4B). Since the specific surface area, pore volume, and average pore diameter of EFD were 4.19 m2/g, 0.0009 cm3/g, and 2.02 nm, respectively, after modification with sodium methoxide, the specific surface area, pore volume, and average pore diameter of the dust all increased to a certain extent, rising to 5.90 m2/g, 0.016 cm3/g, and 11.13 nm, respectively. This indicated that alkaline modification was an efficient approach to enhancing the specific surface area of electric furnace dust, which was beneficial for EFD to act as a carrier for adsorbing active components. The catalyst Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa) obtained after impregnation of EFD/CH3ONa with Na2CO3 exhibited a further decrease in specific surface area to 5.88 m2/g, indicating that the internal pores of EFD/CH3ONa were filled by Na2CO3. SEM-EDS analysis of the catalyst’s microstructure generated the results presented in Figure 4C,D. The surface of Na2CO3&EFD (Figure 4C(a,b)) comprised an interwoven structure of smooth rod-like features (200~500 nm) and loosely porous spherical particles (20~500 nm), exhibiting an overall well-ordered floral cluster arrangement. This morphology facilitated contact between reactant molecules and active sites [33]. As no rod-like morphology was present in the EFD sample prior to Na2CO3 impregnation, the rod-like structures observed may represent Na2CO3 crystallites. The loose spherical particles on the surface likely resulted from Na attachment to the catalyst surface during Na2CO3 dissolution in the impregnation process, causing the content of Na content to increase from 1.71 wt% (EFD) to 7.16 wt% (Na2CO3&EFD). The morphology of Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa) (Figure 4D(a,b)) resembled that of Na2CO3&EFD, but exhibited a greater number of fine rod-like structures. This resulted in a more porous overall structure, enhancing the diffusion efficiency of reactants across the catalyst surface and thereby promoting reaction rate improvement [41]. This explained why EFD/CH3ONa, as a precursor, facilitated more favourable sodium loading compared to EFD. Furthermore, the EDS patterns of Na2CO3&EFD and Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa) (Figure 4C(c),D(c)) revealed that the primary metallic elements on the catalyst surface were Fe, Zn, Na, and Mn, uniformly dispersed throughout the catalyst. Notably, the Na content in the latter increased by 55.45%, consistent with BET analysis results. Additionally, the mass ratios of Na/Fe, Na/Zn, Fe/Mn, Ca/Fe, and Mg/Fe on the Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa) surface were 1/1.60 (Na at 11.13 wt% and Fe at 17.85 wt%), 1/0.73 (Zn at 8.15 wt%), 1/0.16 (Mn at 2.93 wt%), 1/16.38 (Ca at 1.09 wt%), and 1/26.64 (Mg at 0.67 wt%). Notably, the Na/Fe mass ratio represented a substantial increase from the original EFD/CH3ONa value of 1/19.19, confirming the successful loading of Na2CO3.

Figure 4.

(A) XRD patterns of (a) Na2CO3&EFD and (b) Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa); (B) BET analysis of (a) Na2CO3&EFD, (b) EFD/CH3ONa, and (c) Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa); SEM-EDS spectrum of (C) Na2CO3&EFD and (D) Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa). (C) (a,b) SEM images and (c) EDS spectrum of Na2CO3&EFD; (D) (a,b) SEM images and (c) EDS spectrum of Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa).

XPS analysis was utilised to explore the activation mechanism of the Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa) catalyst, with relevant findings summarised in Figure 5. As demonstrated by the broad XPS spectrum in Figure 5a, the presence of Na, Zn, Fe, Mn, O, Ca, and C elements on the catalyst surface. The atomic percentage of Na increased from 0.53% (EFD/CH3ONa) to 16.28% (Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa)), indicating successful impregnation of Na onto the EFD/CH3ONa precursor. The characteristic peaks of O 1s (Figure 5b) detected lattice-site oxygen (OL) at 529.85 eV, 531.21 eV, and 532.12 eV, respectively [38], adsorbed oxygen (Os), and surface hydroxyl oxygen (-OOH), with a higher proportion of surface hydroxyl oxygen (-OOH) (compared to EFD/CH3ONa), indicating the generation of more oxygen vacancies in the catalyst [42]. Furthermore, compared to the O 1s spectrum of EFD/CH3ONa, a new peak at 535.9 eV corresponded to Na-OH [43], potentially representing a key active site for catalyst activity. Figure 5c displays the split peak spectrum of C 1s, wherein the three observed peaks at 284.78 eV, 286.78 eV, and 289.27 eV were assigned to C-C/C=C, C-O, and C=O in Na2CO3·(EFD/CH3ONa), respectively. In Figure 5d, Fe 2p peaks at 710.93 eV, 713.81 eV, and 724.30 eV were detected, corresponding to Fe-C/Fe, Fe3+, and Fe2+, respectively. A satellite peak of Fe 2p was observed at a binding energy of 717.15 eV, showing little variation compared to EFD/CH3ONa. The high-resolution Zn 2p spectrum (Figure 5e) exhibited two characteristic peaks were observed at 1021.64 eV and 1044.61 eV, which are attributed to the spin–orbit split peaks of the Zn 2p3/2 and Zn 2p1/2 orbitals in ZnO, respectively. Comparing this with the narrow-scan Zn 2p spectrum corresponding to EFD/CH3ONa (Figure 2e), it was evident that the binding energy positions had shifted at both sites. This indicated that the introduction of Na2CO3 had changed the local chemical environment of Zn present in the electric furnace dust. The Ca 2p spectrum revealed two peaks, Ca 2p1/2 and Ca 2p3/2 (Figure 5f), both indicating that Ca in Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa) remained in the Ca2+ form. As depicted in Figure 5g, in the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectrum of Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa), the high-resolution Mn 2p region exhibited two distinct peaks at approximately 642.3 eV and 654 eV. These peaks correspond to the spin–orbit-split Mn 2p1/2 and Mn 2p3/2 peaks, respectively. Furthermore, the Mn 2p1/2 peak was resolved into two separate, distinct sub-peaks, attributed to Mn2+ (641.3 eV) and Mn4+ (644.5 eV). Similarly, the Mn 2p3/2 peak was decomposed into two peaks centred at 652.6 and 655.3 eV, corresponding to Mn2+ and Mn3+, respectively. A single main peak at 1071.4 eV was fitted for Na 1s, representing the Na+ present in the sample [35].

Figure 5.

XPS spectra of Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa): (a) total spectrum, (b) O 1s, (c) C 1s, (d) Fe 2p, (e) Zn 2p, (f) Ca 2p, (g) Mn 2p, and (h) Na 1s.

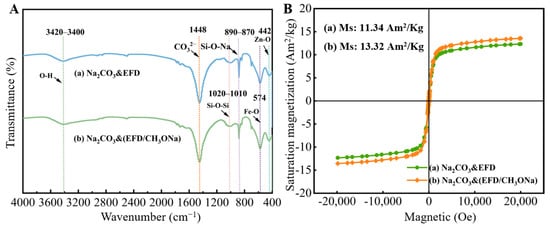

FT-IR spectra, shown in Figure 6A(a,b), were used to analyse the functional group composition of the Na2CO3&EFD and Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa) catalysts. A broad band between 3420 cm−1 and 3400 cm−1 was observed in both sets of samples, attributed to the stretching vibration of the O-H group in water molecules. Fe-O and Zn-O functional groups were observed near 574 cm−1 and 442 cm−1, respectively, consistent with the crystalline phases present in the original electric furnace dust. The intense characteristic peak near 1448 cm−1 corresponded to the CO32− ion in sodium carbonate. Additionally, a peak at 887 cm−1 was analysed, representing the Si-O-Na functional group [44,45]. This confirmed the successful anchoring of Na+ onto the surface of EFD/CH3ONa precursors. This finding was consistent with the XPS characterisation of EFD/CH3ONa. Figure 6B analyses the magnetic susceptibility of the Na2CO3&EFD and Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa) catalysts. It was evident that after Na2CO3 impregnation, the saturation magnetisation of both EFD and EFD/CH3ONa decreased to 12.31 Am2/Kg and 13.57 Am2/Kg, respectively. Nevertheless, they retained superparamagnetic characteristics, indicating that after participating in the transesterification reaction, the catalyst could be separated from reactants using an external magnet, facilitating its reuse.

Figure 6.

(A) FT-IR spectrum and (B) VSM diagram of (a) Na2CO3&EFD and (b) Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa).

Calcination can stabilise the catalyst structure. Consequently, the following subsection will investigate whether different calcination temperatures prove beneficial for enhancing the catalytic performance of Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa).

2.3. Effect of High-Temperature Calcination on the Catalytic Performance of M&(EFD/S)

The calcination temperature significantly influences catalyst performance; selecting an appropriate temperature aids in stabilising the catalyst structure while enhancing the catalytic material’s activity and stability. Herein, the optimal catalyst Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa) identified in the preceding section is subjected to calcination at temperatures ranging from 300 to 900 °C. This study explored the influence of varied temperatures on the catalytic performance of the Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa) catalyst. The cyclic test yields of biodiesel produced from soybean oil using the catalyst (Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa))T are presented in Table 3. At a catalyst loading of 7 wt%, an alcohol/oil molar ratio of 15/1, and a reaction temperature of 65 °C for 2 h, the initial biodiesel yields were 98.8 wt% (300 °C), 99.7 wt% (400 °C), 99.9 wt% (500 °C), 99.8 wt% (600 °C), 99.8 wt% (700 °C), 99.9 wt% (800 °C), and 99.7 wt% (900 °C). It was evident that all catalysts exhibited high activity following calcination treatment. After cyclic testing, only the (Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa))600 samples demonstrated superior stability, sustaining 11 stable catalytic cycles with biodiesel yields consistently above 90.0 wt%. Furthermore, it was observed that the (Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa))600 sample exhibited the slowest decline in activity during the 12th catalytic cycle compared to other samples. However, its stability showed a significant reduction when compared to the uncalcined sample (Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa)). This decline in stability was hypothesised to be associated with the detachment or agglomeration of active components on the catalyst surface caused by high-temperature calcination.

Table 3.

Effect of different calcination temperatures on the catalytic performance of Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa).

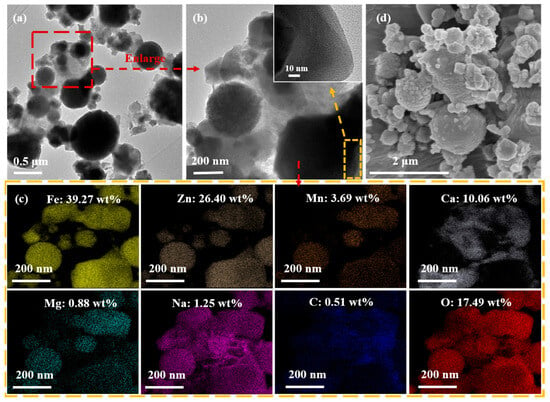

To verify the above conjecture, characterisation analysis of (Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa))600 was conducted using high-resolution transmission electron microscope–energy-dispersive spectrometer (HRTEM-EDS), SEM, XPS, XRD, FT-IR, chemical adsorption analyser (CO2-TPD), and TG. As shown in Figure 7a–d, the morphology of Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa) underwent significant alteration following high-temperature calcination. As shown in Figure 4D(a,b), the Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa) powder comprised numerous fine rod-like structures and loose, porous spherical particles. Following calcination at 600 °C, the rod-like structures disappeared, and agglomeration occurred on the surfaces of the spherical particles. As spherical agglomerates proliferate, they obstruct the catalyst’s porous structure and block pores that could accommodate active sites, thereby reducing the diffusion efficiency of reactants between active sites [46]. This phenomenon was one cause of the decline in catalyst activity following calcination. Combined with the scanning energy spectrum of (Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa))600 (Figure 7c), the relative contents of Fe, Zn, Mn, Ca, Mg, Na, C, and O after calcination at 600 °C were 39.27, 26.40, 3.69, 10.06, 0.88, 1.25, 0.51, and 17.49 wt%, respectively. The corresponding mass ratios for Na/Fe, Na/Zn, Fe/Mn, Ca/Fe and Mg/Fe were 1:31.42, 1:21.12, 1:0.09, 1:3.90 and 1:44.63, respectively. Compared to Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa), the contents of Mn and Mg showed little change, while those of Fe, Zn, and Ca increased. This might stem from calcination at high temperatures, promoting the transformation of crystalline phases towards ZnFe2O4 and Ca0.15Fe2.85O4. Additionally, substantial decreases in Na, C, and O contents were observed. This might result from the reaction of crystalline Na2CO3 with other components in the sample (such as SiO2 and Al2O3), with C and O volatilising as CO2.

Figure 7.

(a–c) TEM-EDS spectra and (d) SEM images of (Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa))600.

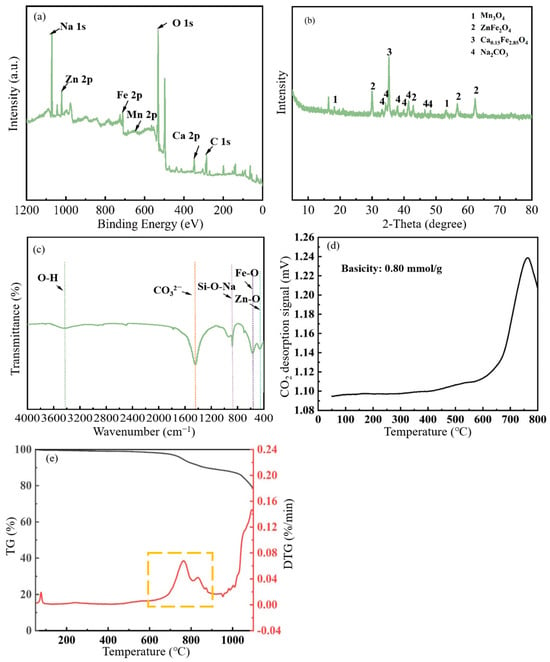

XPS characterisation analysis of (Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa))600 (Figure 8a) revealed the relative atomic contents of Na 1s, Zn 2p, Fe 2p, Mn 2p, O 1s, Ca 2p, and C 1s were 13.92%, 2.04%, 5.70%, 0.60%, 51.44%, 2.56%, and 23.75%, respectively. It was noted that the relative content of Na atoms decreased from 16.28% in the original (Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa)) to 13.92%, indicating that the calcination process caused partial sodium loss. The XRD pattern of (Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa))600 is shown in Figure 8b. The XRD pattern of calcined Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa) resembled that prior to calcination, but at 2θ = 35.25°, the original Na2CO3 phase transitions to Ca0.15Fe2.85O4. Comparing this with the crystalline phase detected with EFD/CH3ONa (Figure 1A(e)), it could be inferred that following calcination at 600 °C, some Na2CO3 adhering to Ca0.15Fe2.85O4 detached, allowing the original Ca0.15Fe2.85O4 phase to be detected. This confirmed the aforementioned conjecture. Further analysis of functional groups in the (Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa))600 sample via FT-IR revealed, as shown in Figure 8c. The characteristic band of Si-O-Si bonds at 1020–1010 cm−1 for the sample Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa) disappeared after calcination at 600 °C, which indicated that the surface Si-O-Si bonds were destroyed. The characteristic spectral band corresponding to CO32- was also weakened. The CO2-TPD analysis, shown in Figure 8d, detected a strong basic site in the catalyst between 700 and 800 °C, with a total basicity of 0.80 mmol/L. No other basic sites were identified beyond this [47]. Moreover, the corresponding TG-DTG analysis (Figure 8e) indicated substantial mass loss commencing at 600 °C, potentially attributable to Na2CO3 decomposition. This finding corresponded to the analytical results from XRD and TEM-EDS.

Figure 8.

(a) XPS survey spectrum, (b) XRD pattern, (c) FT-IR spectrum, (d) CO2-TPD profile, and (e) TG-DTG curves of (Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa))600.

2.4. Analysis of Heavy Metals in Products

Following the 14th catalytic cycle (reaction temperature of 65 °C, reaction time of 2 h, catalyst amount of 7 wt%, and alcohol/oil molar ratio of 15/1), the resulting product was filtered using a 0.22 μm filter head and dried in an oven at 75 °C. The upper layer of biodiesel and the lower layer of glycerol were collected separately for ICP-OES analysis. The concentrations of As, Cd, Cr, Fe, Na, Pb and Sr detected in the biodiesel were 0.30, 0.00, 0.36, 0.87, 0.29, 0.12, and 0.01 mg/L, respectively. In glycerol, the concentrations of As, Cd, Cr, Fe, Na, Pb, and Sr were 0.19, 0.00, 0.45, 2.95, 267.60, 0.69, and 0.04 mg/L, respectively. Only a small quantity of active components (Fe and Na) was leached, with the leached components predominantly deposited in the glycerol. Furthermore, the levels of harmful metals in both the biodiesel and glycerol were below 1.00 mg/L, complying with China’s B5 diesel national standard (95% petroleum diesel and 5% biodiesel) (total metal content < 5 mg/L; GB 25199-2017B5) [48]. This indicated that the solid-waste-based catalyst employed in this study possesses a certain degree of resistance to leaching, and the biodiesel produced can be used as a conventional fuel.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Experimental Materials and Reagents

The soybean oil used in this study (acid value (AV) = 0.02 mg KOH/g, molecular weight (MW) = 860.49 g/mol, saponification value (SV) = 195.60 mg KOH/g) was purchased from a supermarket in Tangshan City, China. Electric furnace dust (abbreviated: EFD) originates from a steelworks in Tangshan City. The EFD powder was dried in an oven at 105 °C to constant weight and sieved through a 200-mesh screen (<75 μm). The hydrochloric acid (HCl, ≥37%), sulfuric acid (H2SO4, ≥99.99%), nitric acid (HNO3, ≥99.99%), oxalic acid (C2H2O4, ≥99.99%) and ammonia solution (NH3·H2O, ≥25%) used in the research institute were procured from Tianjin Yongda Chemical Reagents Co., Ltd. (Tianjin, China). Phosphoric acid (H3PO4, ≥85%), acetic acid (CH3COOH, ≥36%), malic acid (C4H6O5, ≥85%), citric acid (C6H8O7, ≥36%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, ≥96%), potassium hydroxide (KOH, ≥90%), sodium methoxide (CH3ONa, ≥97%), potassium methoxide (CH3OK, ≥95%), sodium ethoxide (C2H5ONa, ≥96%), anhydrous sodium carbonate (Na2CO3, ≥99.99%), potassium carbonate (K2CO3, ≥99.99%), Lithium carbonate (Li2CO3, ≥99%), Cadmium carbonate (CdCO3, ≥99.99%), Barium carbonate (BaCO3, ≥99.99%), sodium carbonate decahydrate (Na2CO3·10H2O, ≥99%), sodium hydrogen carbonate (NaHCO3, ≥99%), methanol (CH3OH, ≥99.5%), anhydrous ethanol (C2H5OH, ≥99.5%), dichloromethane (CH2Cl2, ≥99.9%), methyl heptadecanoate (C18H36O2, ≥99.0%), methyl palmitate (C17H34O2, ≥99.0%), methyl linolenate (C19H32O2, ≥99.5%), methyl oleate (C19H36O2, ≥99.0%), methyl linoleate (C19H34O2, ≥99.0%) and methyl stearate (C19H38O2, ≥99.0%) were procured from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

3.2. Preparation of Catalyst

3.2.1. Preparation of Precursors from Acid/Alkali-Modified Electric Furnace Dust

1 mol/L hydrochloric acid, sulfuric acid, nitric acid, phosphoric acid, sodium hydroxide, potassium hydroxide, ammonia water, acetic acid, oxalic acid, malic acid, citric acid, sodium methoxide, potassium methoxide, and sodium ethoxide solutions were used as modification solutions. 5 g of electric furnace dust powder and 50 mL of 1 mol/L modification solution were placed in a 100 mL serum bottle, which was then sealed and transferred to a thermostatic heating magnetic stirrer (DF-101S, Shanghai Lichen Bangxi Instrument Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) for magnetic stirring at 70 °C for 60 min. The suspension after reaction was transferred to a 1000 mL sand core suction filter flask equipped with a 0.45 μm filter membrane, and the filter cake was rinsed with deionised water until the pH of the washings was around 7. The washed filter residue was placed in an oven (DGG-9140B, Shanghai Senxin Experimental Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) at 105 °C to dry to constant weight, ground, and sieved through a 200-mesh sieve (<75 μm), which was named modified electric furnace dust (EFD/S) (where S represented the type of acid or alkali modifier). Approximately 0.8 g of EFD/S was placed in a tube furnace (SK-ES08143, Tianjin Zhonghuan Experimental Electric Furnace Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China) for calcination at 300–900 °C for 2 h (N2 flow rate: 200 mL/min; heating rate: 10 °C/min), and named (EFD/S)T (where T represented the calcination temperature).

3.2.2. Catalyst Preparation by Impregnation Activation of Modified Electric Furnace Dust

A 100 mL serum bottle was charged with 1 g of EFD or EFD/S, 1.2 g of activator (metal salt), and 20 mL of deionised water, which was then transferred to a thermostatic heating magnetic stirrer for magnetic stirring at 75 °C for 2 h. The reacted mixture was transferred to an oven at 105 °C to dry to constant weight, ground, and screened through a 200-mesh screen (<75 μm), which was named M&EFD or M&(EFD/S) (where S represented the type of acid or alkali modifier, and M represented the type of activator). Roughly 0.8 g of M&(EFD/S) was placed in a tube furnace and calcined at 300–900 °C for 2 h. (N2 flow rate: 200 mL/min; heating rate: 10 °C/min), and the obtained sample was named (M&(EFD/S))T (where T represented the calcination temperature).

3.3. Preparation and Analysis of Biodiesel

7 g of soybean oil, 0.49 g of catalyst (with a catalyst amount of 7 wt%) and 4.8 g of methanol (alcohol/oil molar ratio of 15/1) were placed in a vial, which was then sealed with a rubber–aluminium cap. The vial containing the reactants was transferred to a thermostatic heating magnetic stirrer, followed by magnetic stirring at 65 °C for 2 h. After the reaction, the vial was taken out and allowed to stand for 5 min. The mixture in the vial spontaneously separated into three layers under gravity, namely crude biodiesel, a mixture of methanol and glycerol, and solid catalyst. The catalyst at the bottom layer could be directly used in the next cycle without washing and drying. The crude biodiesel was aspirated with a 10 mL syringe, filtered through a 0.22 μm filter head, and then dried in an oven at 75 °C to constant weight to remove excess methanol. Metal concentrations in biodiesel and glycerol were determined using ICP-OES. The filtered and dried biodiesel was analysed using a gas chromatograph (GC-2014 C, Shimadzu Enterprise Management (China) Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) equipped with an Rtx-Wax capillary column (30 m × Φ 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm). Each sample yield was tested twice, with the average value taken. The analysis conditions were as follows: injection port temperature of 260 °C, chromatographic column temperature of 220 °C, detector temperature of 280 °C, carrier gas flow rate of 1 mL/min, and split ratio of 40:1. Dichloromethane was used as the solvent, and methyl heptadecanoate (HAME, C17:0) was used as the internal standard for quantitative analysis of biodiesel. The yield of biodiesel was calculated based on the mass of standard methyl heptadecanoate, correction factor, and peak area. The calculation Formula (1) is as follows:

where

- Y—Biodiesel yield, wt%;

- WHAME—HAME weight, g;

- AFAME—Chromatographic peak area of FAME, uV min;

- AHAME—Chromatographic peak area of HAME, uV min;

- Fi—Correction factor;

- WC—The weight of crude biodiesel, g.

The correction factors for methyl palmitate, methyl oleate, methyl stearate, methyl linoleate, methyl linolenate and methyl eicosapentaenoate relative to methyl heptadecanoate were 1.000, 0.919, 0.834, 0.936, 1.055 and 0.970, respectively [49].

3.4. Characterisation of Catalysts

The elemental content in the samples was measured using an elemental analyser (Vario EL cube, Elementar Analysensysteme GmbH, Hanau, Germany) and an inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES, Optima 5300, PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The crystalline phase characteristics of the samples were analysed using an X-ray diffractometer (XRD, D8 Advance, Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany). The surface functional group composition of the samples was detected within the 400~4000 cm−1 range using a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FT-IR, Nicolet IS10, Thermo Nicolet Corporation, Madison, WI, USA). Thermogravimetric and differential scanning calorimetric analysis of the samples was conducted using a thermogravimetric analyser (TG-DTG, NETZSCH STA449 F5/F3 Jupiter, Netzsch-Gerätebau GmbH, Selb, Germany) within the temperature range of 25–900 °C. Surface alkalinity was determined using a chemical adsorption analyser (CO2-TPD, AutoChem II 2920, Micromeritics Instrument Co., Ltd., Norcross, GA, USA). The specific surface area and pore size of the samples were determined using a physical adsorption analyser (ASAP 2460, Micromeritics Instrument Co., Ltd., Northcross, GA, USA) by the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method. Field-emission scanning electron microscope equipped with an energy-dispersive spectrometer (SEM-EDS, SU8020, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) and high-resolution transmission electron microscope–energy-dispersive spectrometer (HRTEM-EDS, FEI Tecnai G2 F30, Thermo Nicolet Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) were used to characterise the surface morphology and elemental composition of the samples. The saturation magnetisation of the samples was measured using a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM, SQUID-VSM, MPMS3, Quantum Design International, San Diego, CA, USA). The surface elemental composition and chemical environment of the samples were analysed using an X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (XPS, Thermo escalab 250XI, Thermo Fisher Scientific (China) Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

4. Conclusions

Overall, the current study synthesised a novel sodium carbonate-supported, sodium methoxide-modified, electric furnace dust-based magnetic multiphase catalyst (Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa)). When subjected to reaction temperature of 65 °C, reaction duration of 2 h, 7% catalyst loading, and alcohol/oil molar ratio of 15/1, the catalyst realised a 100.00 wt% yield of biodiesel. The catalyst demonstrated good activity and stability, exhibiting yields exceeding 93.44 wt% over 14 recycling cycles. Characterisation revealed that the active component Na+ forms ionic bonds with hydroxyl oxygen atoms on the modified surface (EFD/CH3ONa), creating critical active sites essential for the catalyst’s high performance. Furthermore, the catalyst exhibits a saturation magnetisation of 13.57 Am2/kg, sufficient for separating (Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa)) from the reaction system using a magnet. The catalytic performance of the calcined catalyst (Na2CO3&(EFD/CH3ONa))600 (effective catalytic cycles: 11) exhibited a decline. Characterisation analysis confirmed this was attributable to partial detachment of Na+ from the modified surface (EFD/CH3ONa) and subsequent agglomeration. In summary, this study not only provided a viable approach for preparing high-performance magnetic solid-waste-based catalysts for efficient, clean biodiesel production but also pioneered a new pathway for developing green, low-carbon, and high-value utilisation processes for electric furnace dust.

5. Research Outlook

Reusability is a key characteristic for evaluating catalyst performance. Current catalysts still suffer from issues such as loss of active components and structural instability of the support during repeated cycles. To further broaden the application of catalysts based on solid waste for the production of biodiesel, future work may consider enhancing catalyst activity and stability by incorporating a binder between the active component and the support. Combining DFT calculations with advanced characterisation techniques (such as synchrotron radiation and three-dimensional reconstruction technology), this approach enables the targeted design of catalytic materials and precise regulation of active sites, thereby achieving industrial standards for the efficient, stable, low-cost, and green production of biodiesel.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Writing—Original draft preparation and Funding acquisition, Y.-T.W.; Methodology, Investigation, Validation and Writing—Original draft preparation, K.-L.D.; Methodology, Investigation, Validation and Writing—Original draft preparation, R.J.; Writing—Review and Editing, Y.-J.W.; Data Curation and Validation, L.-Y.Z.; Data Curation and Validation, S.-H.Z.; Data Curation and Validation, Z.-H.T.; Data Curation and Validation, J.Y.; Data Curation and Validation, H.Z.; Conceptualisation, Methodology, Validation, Supervision, Writing—Review and Editing and Funding acquisition, J.-G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors wish to acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52274333 and U21A20112), the Innovation Research Group Project of the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (E2022209093), Distinguished Youth Science Fund Project of Hebei Natural Science Foundation (E2023209128), S&T Program of Hebei (25363801D), the Central Guidance Local Science and Technology Development Foundation of the Hebei Provincial Department of Science and Technology (236Z3802G and 236Z3803G), the Key Scientific Research Project of the North China University of Science and Technology (ZD-ST-202311–23), and the Youth Preliminary Research Foundation of Metallurgical and Energy College (RN20244187).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their special thanks to Hong-Peng Li from Tangshan Jinlihai Biodiesel Co., Ltd. (Luannan Industrial Park, Tangshan, China) for providing technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Elgharbawy, A.S.; Osman, A.I.; El Demerdash, A.G.M.; Sadik, W.A.; Kasaby, M.A.; Ali, S.E. Enhancing biodiesel production efficiency with industrial waste-derived catalysts: Techno-economic analysis of microwave and ultrasonic transesterification methods. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 321, 118945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, A.K.; Liu, X.; Yuan, Y.; Sun, Y.; Abou-Elyazed, A.S. A sustainable sulfated zirconia catalyst for high-yield biodiesel production: Structure, activity, and mechanism. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2026, 715, 164574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayebzadeh, H.; Rahmanivahid, B.; Maleki, B. Influence of fuel mixture on the performance of K/Ca-Al catalyst synthesized via solution combustion method for Microwave-Assisted biodiesel Production: Optimization study via RSM. Fuel 2026, 405, 136436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba-Rubio, A.C.; Vila, F.; Alonso, D.M.; Ojeda, M.; Mariscal, R.; Granados, M.L. Deactivation of organosulfonic acid functionalized silica catalysts during biodiesel. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2010, 95, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuepethkaew, S.; Klomklao, S.; Phonsatta, N.; Panya, A.; Benjakul, S.; Kishimura, H. Utilization of Nile tilapia viscera oil and lipase as a novel and potential feedstock and catalyst for sustainable biodiesel production. Renew. Energy 2024, 236, 121514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, A.; Khan, H.; Arif, A.; Arshad, M.; Hussain, S.; Maqbool, A. Sustainable biodiesel production via Alkanna tinctoria oil Conversion: A multi-method modeling approach utilizing crab shell-derived biochar catalysts. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 203, 108287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satriadi, H.; Setyojati, P.W.; Shihab, D.; Buchori, L.; Hadiyanto, H.; Nurushofa, F.A. Preparation CaO/MgO/Fe3O4 magnetite catalyst and catalytic test for biodiesel production. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholkina, E.; Kumar, N.; Ohra-aho, T.; Lehtonen, J.; Lindfors, C.; Perula, M.; Murzin, D.Y. Transformation of industrial steel slag with different structure-modifying agents for synthesis of catalysts. Catal. Today 2020, 355, 768–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Zhao, X.; Peng, K.; Liang, S.; Jia, X.; Qian, L. Catalytic reforming of biomass primary tar from pyrolysis over waste steel slag based catalysts. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2019, 44, 16224–16233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amdeha, E.; Mohamed, R.S.; Dhmees, A.S. Sonochemical assisted preparation of ZnS-ZnO/MCM-41 based on blast furnace slag and electric arc furnace dust for Cr (VI) photoreduction. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 23014–23027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.T.; Gao, D.; Zeng, Y.N.; Li, J.G.; Ji, A.M.; Liu, T.J.; Fang, Z. Efficient production of biodiesel with electric furnace dust impregnated in Na2CO3 solution. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 30, 129772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawryluk-Sidoruk, M.; Raczkiewicz, M.; Krasucka, P.; Duan, W.; Mašek, O.; Zarzycki, R.; Oleszczuk, P. Effect of biochar chemical modification (acid, base and hydrogen peroxide) on contaminants content depending on feedstock and pyrolysis conditions. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 481, 148329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Tang, L.; Song, W.; Jiang, H.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H. Predicting and refining acid modifications of biochar based on machine learning and bibliometric analysis: Specific surface area, average pore size, and total pore volume. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Cheng, D.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Du, J.; Alonso-Vante, N.; Yang, J. Iron-supported on alkali-treated zeolites for efficient catalytic decomposition of low-concentration N2O for marine fuel aftertreatment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syeitkhajy, A.; Hamid, M.A.; Boroglu, M.S.; Boz, I. Efficient synthesis of phosphorus-promoted and alkali-modified ZSM-5 catalyst for catalytic dehydration of lactic acid to acrylic acid. Results Chem. 2025, 13, 101942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Wang, Q.; Lu, Y.; Tang, M.; Lu, S. Study on impregnation process optimization for regenerating the spent V2O5-WO3/TiO2 catalysts. Mol. Catal. 2023, 550, 113578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lete, A.; Lacleta, F.; García, L.; Ruiz, J.; Arauzo, J. Effect of calcination temperature and atmosphere on the properties and performance of CuAl catalysts for glycerol dehydration to acetol. Biomass Bioenergy 2025, 195, 107725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Y.; Xao, H.; Li, J.R. Promotional effect of calcination temperature on the Mn-Fe-Al based monolithic catalysts prepared by the low-cost materials for the acetone efficient degradation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 703, 163412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Hu, K.; Feng, J.; Ning, P.; Wang, F.; Cui, S.; Jia, L. Resource utilization of electric arc furnace dust: Efficient wet desulfurization and valuable metal leaching kinetics investigation. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 375, 124419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Li, H.; Wang, R.; Zeng, S.; Xu, W.; Liu, Y. Dual-layer coating Co@Fe@Fe3O4 heterogeneous magnetic particles and their electromagnetic absorption properties. Solid State Sci. 2025, 169, 108081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.T.; Mathew, A.; Akbar, M.A. Use of hazardous electric arc furnace dust in the construction industry: A cleaner production approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 377, 134282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Xiong, Z.; Zhu, W. Developing sustainable cement through alkali-activation of waste glass and hydrophobic modification. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 479, 141507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ani, Y.M.Y.; Ridha, A.M.; Abbas, T.K.; Ahmadlouydarab, M.; Kamar, F.H. Modeling and enhanced biodiesel production using a sustainable green catalyst based on palm frond-activated carbon supported with zirconium oxide. Fuel 2026, 403, 136118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, X.; Sun, L.; Zhao, J.; Fu, Y. Novel amphiphilic magnetic nanocellulose-based phosphotungstic acid type ionic liquid catalysts for biodiesel production. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.; Xu, J.; Zhu, S.; Deng, Z.; Wang, B.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, F. Valorization of waste cattail to porous carbon-based solid acid catalyst for highly efficient production of levulinic acid from fructose. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 117893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, T.; Yang, Y.; Fang, M.; Gao, X. Calcium recovery from waste carbide slag via ammonium sulfate leaching system. J. Cleaner Prod. 2022, 377, 134308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, R. Study on the Mechanism of Activity Regulation of Modified Steel Slag and Synergistic Preparation of Biodiesel. Master’s Thesis, North China University of Science and Technology, Qinhuangdao, China, 2024. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Q.; Bai, Y.; Wang, L.; Feng, T.; Lu, S.; Zhang, A.; Hu, N. Synergistic catalytic degradation of Methotrexate using Ce-based high-entropy metal oxides: Insights from DFT calculations and CWPO performance. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 357, 130130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, T.; Liu, S.; Sun, L.; Feng, X.; Zhao, B.; An, S.; Wang, L. Efficient CO2 capture by a defect-driven O/N co-doped ultramicroporous carbon derived from plastics and biomass solid wastes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 364, 132585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhang, L.; Wei, G.; Yuan, Y.; Huang, Z. Synthesis, characterization and application of a novel carbon-doped mix metal oxide catalyst for production of castor oil biodiesel. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 373, 133768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Pan, Y.; Cao, Q.; Peng, B.; Meng, F.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H. Upcycling waste plastics into FeNi@CNTs chainmail catalysts for effective degradation of norfloxacin: The synergy between metal core and CNTs shell. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 326, 124735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemati, F.; Rangraz, Y. ZnSe nanoparticles anchored on N-doped mesoporous carbon prepared from zinc-based bio-MOF and chitosan as an efficient catalyst for selective hydrogenation of nitroarenes under mild conditions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 320, 145794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Wei, Z.; Wang, C.; Ning, P.; He, M.; Bao, S.; Li, K. One-step synthesis of magnetic catalysts containing Mn3O4-Fe3O4 from manganese slag for degradation of enrofloxacin by activation of peroxymonosulfate. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 499, 156505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Li, X.; Zhan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, K.; Liu, J.; Sakata, Y. Sodium-doped La2Ti2O7 synthesized by molten salt synthesis method for photocatalytic overall water splitting. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2025, 692, 120079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Harahsheh, M.; Kingman, S.; Al-Makhadmah, L.; Hamilton, I.E. Microwave treatment of electric arc furnace dust with PVC: Dielectric characterization and pyrolysis-leaching. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 274, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, M.M.; Saczk, A.A.; da Silva Felix, F.; Penido, E.S.; Santos, T.A.R.; de Souza Teixeira, A.; Magalhães, F. Characterization of electric arc furnace dust and its application in photocatalytic reactions to degrade organic contaminants in synthetic and real samples. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2023, 438, 114585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, C.; Piehl, P.; Weingart, E.; Stolle, D.; Al-Sabbagh, D.; Ostermann, M.; Adam, C. Selective removal of zinc and lead from electric arc furnace dust by chlorination–evaporation reactions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 465, 133421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Zhao, D.; Yan, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hu, X.; Liu, P. Enhanced peroxymonosulfate activation for antibiotic and heavy metal removal using ZIF-67-derived magnetic Ni/Co-LDH@NC: Bimetallic electronic synergy and oxygen vacancy effects. App. Catal. B Environ. 2025, 362, 124753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lim, A.; Poon, C.S.; Kang, S.H.; Moon, J. Scalable carbonation of low-reactivity steel slag monoliths using sodium-based carbonates. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2025, 165, 106338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijo, B.; Fernando, E.; Ramos, M.; Dias, A.P.S. Biodiesel production over sodium carbonate and bicarbonate catalysts. Fuel 2022, 323, 124383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikia, K.; Jamadar, S.P.; Li, H.; Gurunathan, B.; Halder, G.; Rongpipi, M.; Rokhum, S.L. Mango leaves-derived carbonaceous material as a green catalyst for biodiesel synthesis from Jatropha curcas oil. Mol. Catal. 2025, 587, 115499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Li, P.; Zhang, S.; Sun, X.; Cheng, S.; Jiang, Y. High-performance MnOx-CuO catalysts for low-temperature CO oxidation: Metal interaction and reaction mechanism. Mol. Catal. 2025, 576, 114945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousba, D.; Sobhi, C.; Zouaoui, E.; Rouibah, K.; Boublia, A.; Ferkous, H.; Benguerba, Y. Efficient biodiesel production from recycled cooking oil using a NaOH/CoFe2O4 magnetic nano-catalyst: Synthesis, characterization, and process enhancement for sustainability. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 300, 118021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, X.; Chen, S.; Yun, Z. Continuous production of biodiesel from cottonseed oil and methanol using a column reactor packed with calcined sodium silicate base catalyst. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 24, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manurung, R.; Hasibuan, R.; Siregar, A.G.A. Preparation and characterization of lithium, sodium, and potassium silicate from palm leaf as a potential solid base catalyst in developed biodiesel production. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2024, 9, 100543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frainetti, A.J.; Cullen, J.J.; Klinghoffer, N.B. Stability of biochar-supported Ni catalysts during carbon dioxide methanation: A charac-teristic analysis of deactivation mechanisms and catalyst longevity. Biomass Bioenergy 2026, 206, 108645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dun, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, M.; Dong, X.; Wei, S.; Liao, J.; Zhang, P. Unraveling the synergistic effect between KF and MgO for effective transesterification of sunflower oil to produce biodiesel. Fuel 2026, 405, 136761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 25199-2017; B5 diesel fuels. National Standards of the Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Wang, Y.T.; Gao, D.; Yang, J.; Zeng, Y.N.; Li, J.G.; Wang, Y.J.; Fang, Z. Highly stable heterogeneous catalysts from electric furnace dust for biodiesel production: Optimization, performance and reaction kinetics. Catal. Today 2022, 404, 78–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.