Reactivity of Antibodies Immobilized on Gold Nanoparticles: Fluorescence Quenching Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

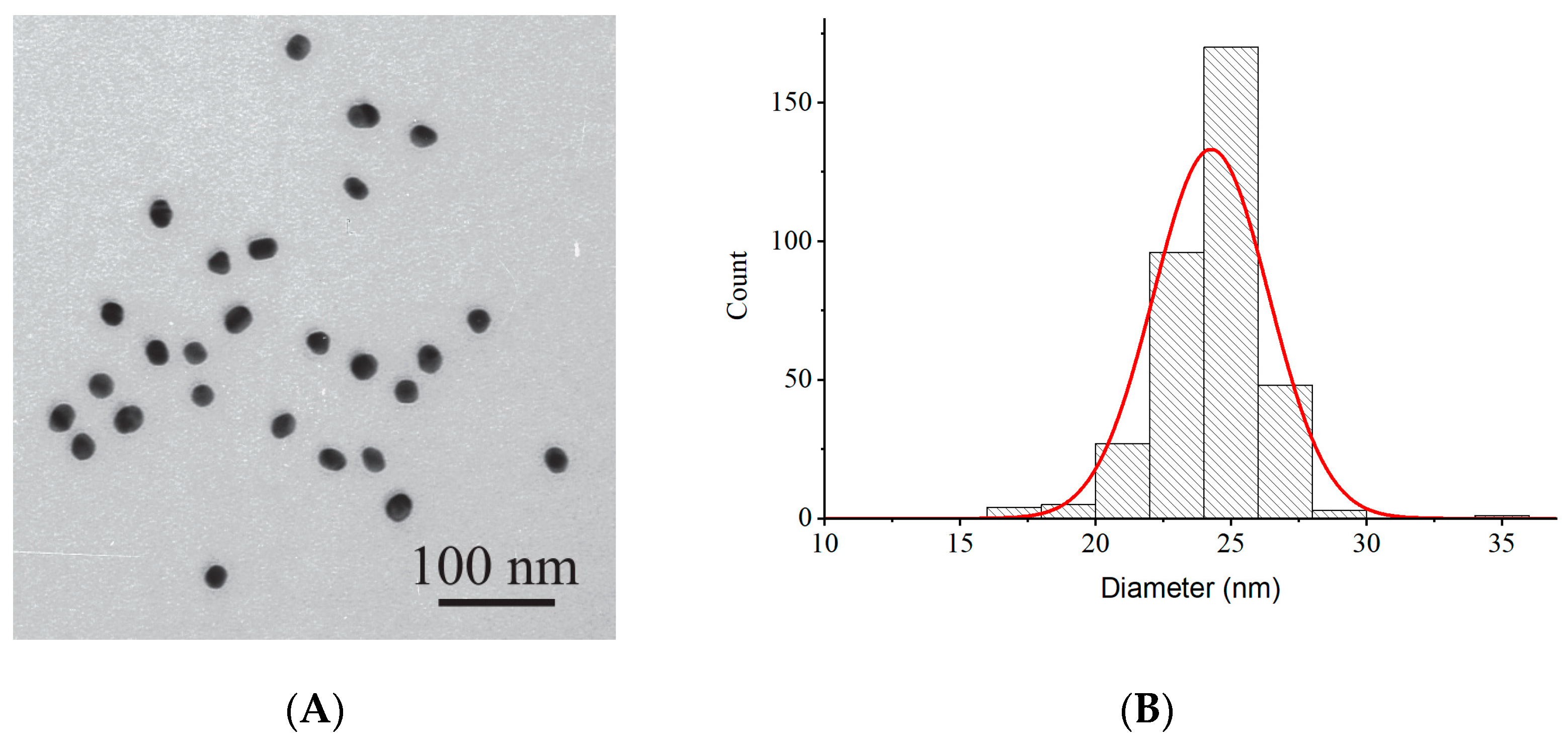

2.1. Characterization of GNPs

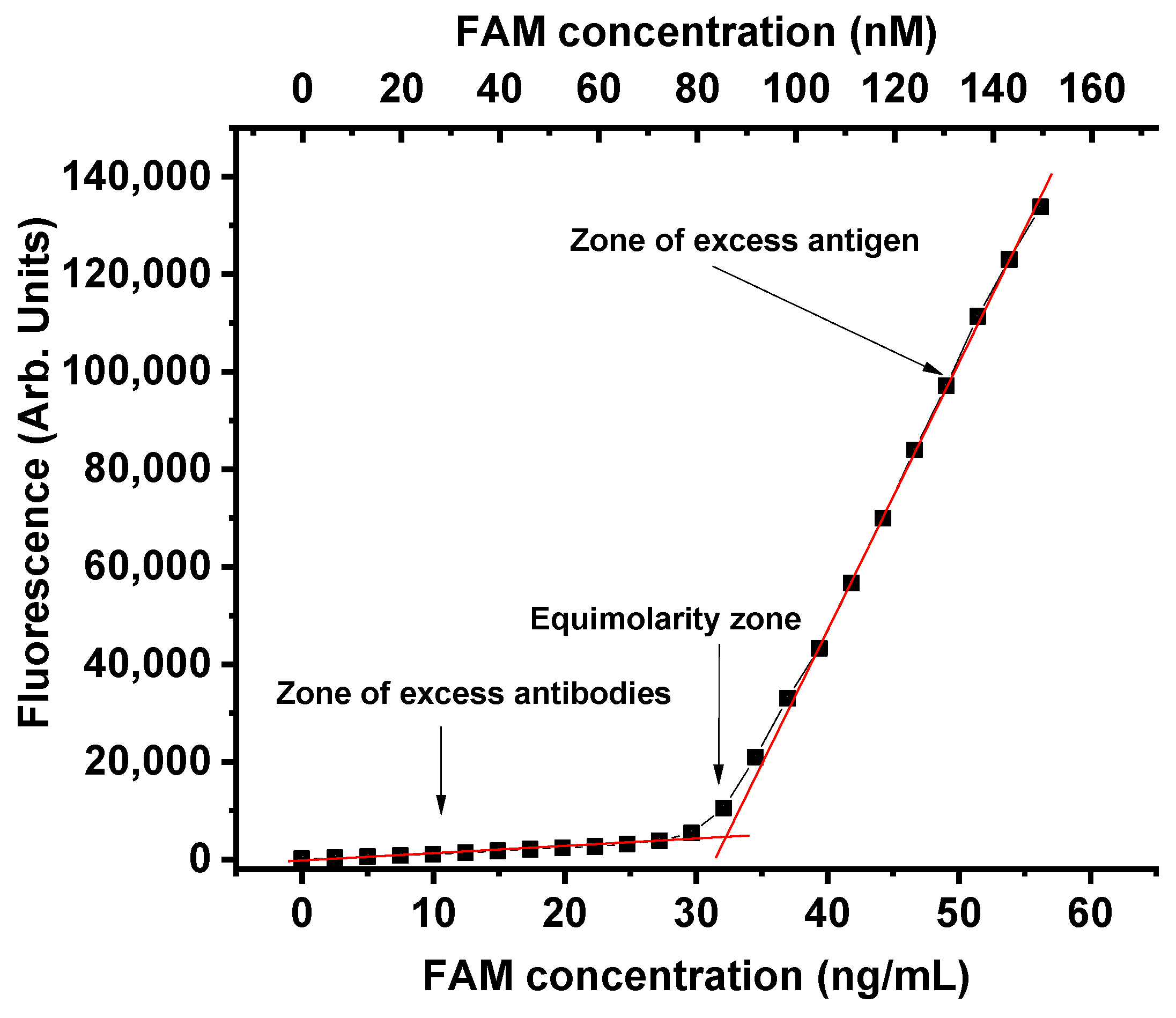

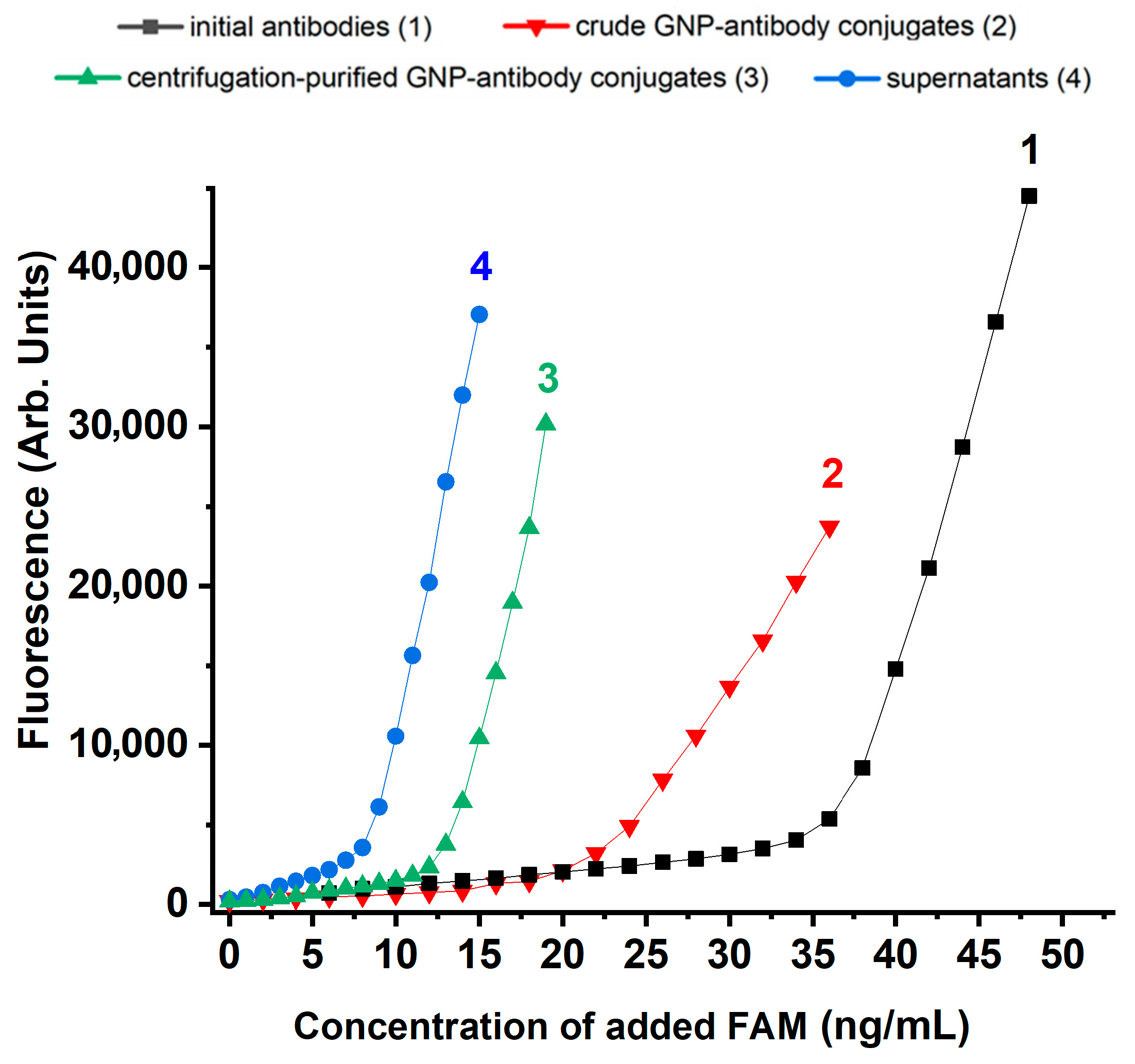

2.2. Testing the Influence of Antigen–Antibody Interaction on Fluorophore Fluorescence

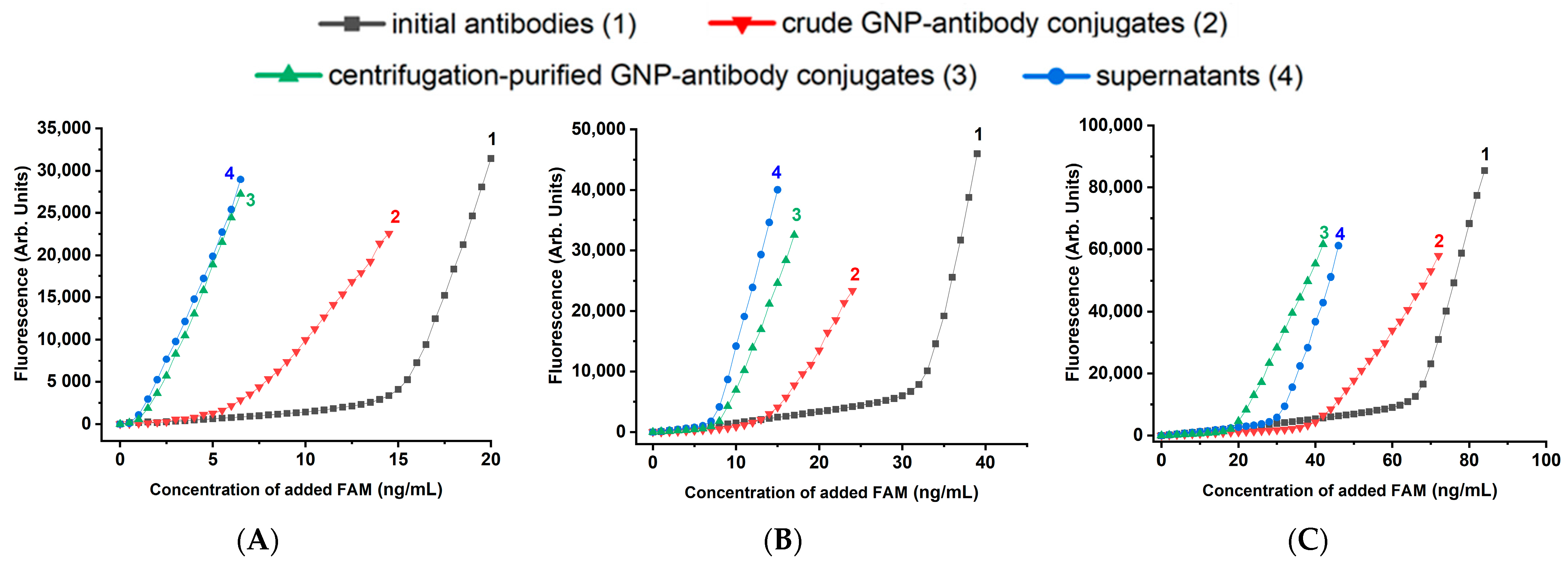

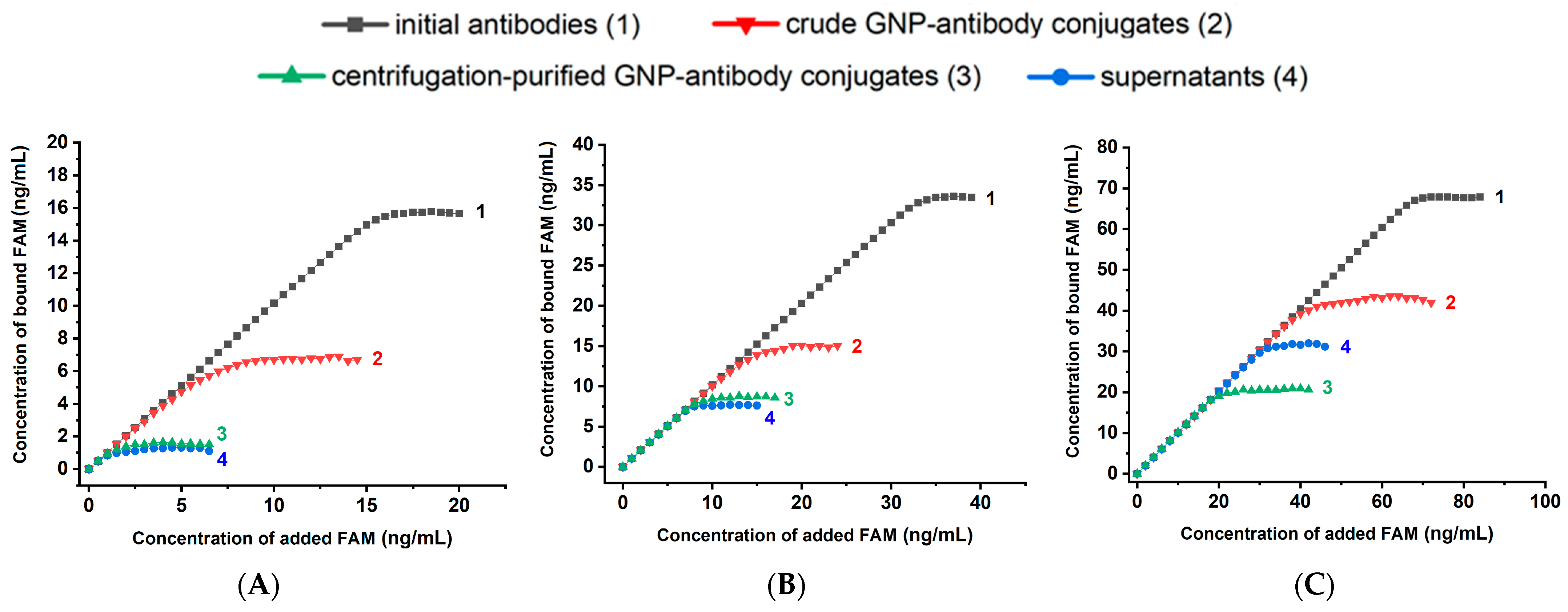

2.3. Technique of Experiments for Determining the Antigen-Binding Capacity of Anti-Fluorescein Antibodies

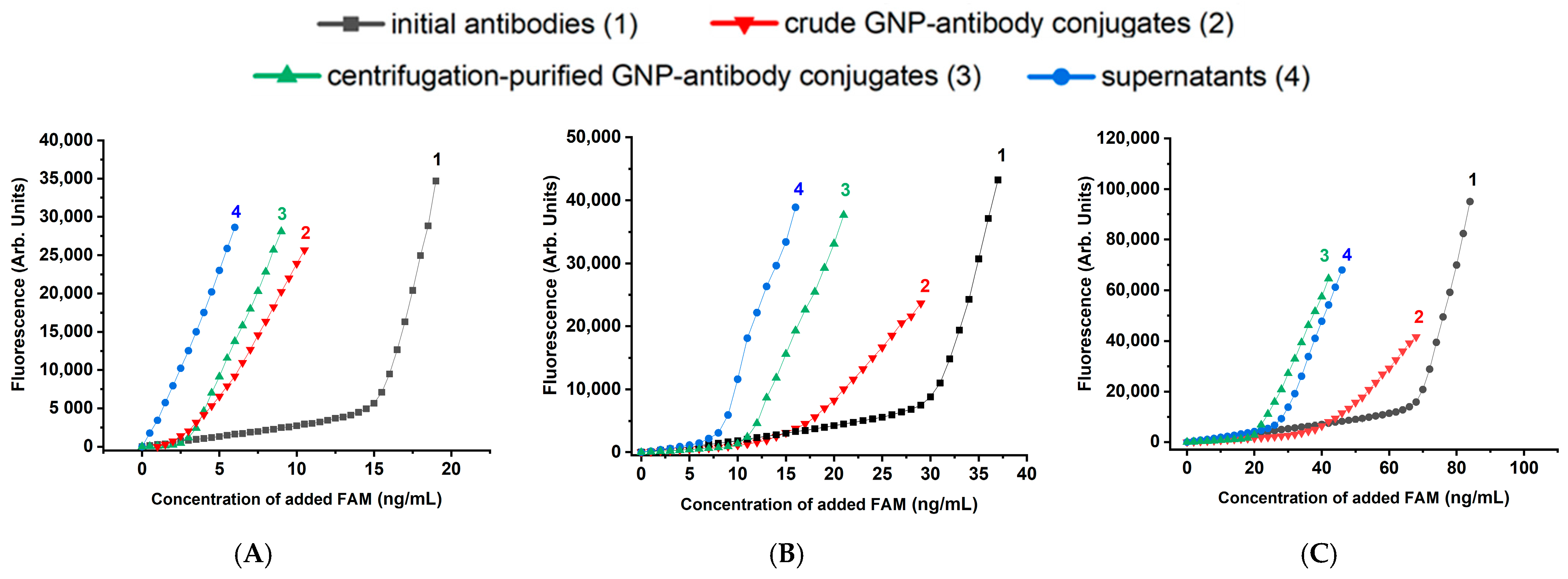

2.4. Description and Justification of the Design of Experiments to Test Different GNP-Antibody Conjugates

- the binding capacity of pure antibodies allows estimating the proportion of active antigen-binding sites in the original antibody preparation;

- the binding capacity of the reaction mixture containing both conjugated and free antibodies provides a direct evaluation of the proportion of antibodies that lose activity as a result of their binding to nanoparticles;

- the binding capacity of the supernatant obtained after separation of the conjugate by centrifugation allows estimating the proportion of antibodies unbound to nanoparticles (assuming centrifugation does not affect the binding capacity of antibodies);

- the binding capacity of the purified conjugate reflects the final activity of the conjugated antibodies.

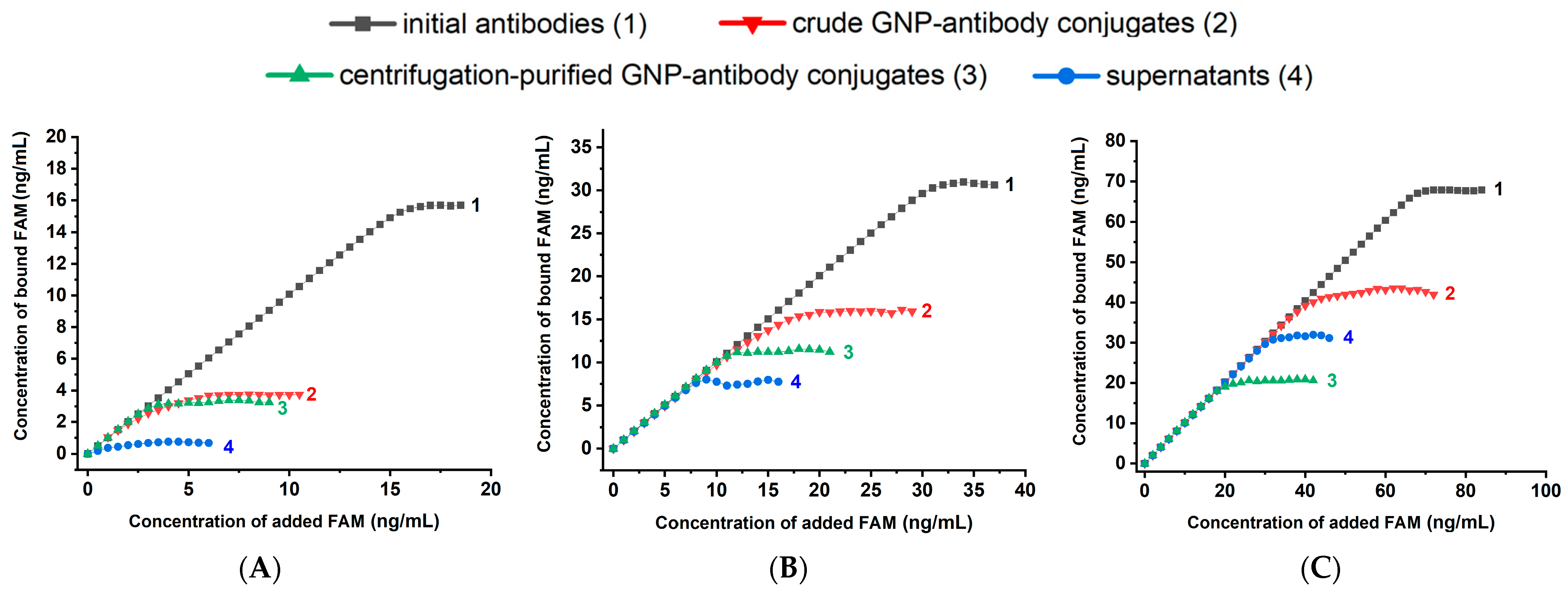

2.5. Experimental Characterization of Stabilized GNP-Antibody Conjugates

2.6. Assessment of the Degree of Reactivity Retention for Antibodies Conjugated with GNPs

2.7. Reproducibility of Measurements for Conjugates’ Composition and Activity

2.8. The Impact of the Proposed Technique on the Knowledge About the Properties of Antibody-GNP Conjugates

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Preparation of Gold Nanoparticles (GNPs)

3.3. Characterization of GNPs by Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

3.4. Determination of the Hydrodynamic Radius of GNPs by the Dynamic Light Scattering Method

3.5. Conjugation of GNPs with Anti-Fluorescein Antibodies

3.6. Testing the Interaction of Free and GNPs-Bound Antibodies with Fluorescein Antigen

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, J.W.; Choi, S.R.; Heo, J.H. Simultaneous stabilization and functionalization of gold nanoparticles via biomolecule conjugation: Progress and perspectives. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 42311–42328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabatabaei, M.S.; Islam, R.; Ahmed, M. Applications of gold nanoparticles in ELISA, PCR, and immuno-PCR assays: A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1143, 250–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Mazouzi, Y.; Salmain, M.; Liedberg, B.; Boujday, S. Antibody-gold nanoparticle bioconjugates for biosensors: Synthesis, characterization and selected applications. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 165, 112370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, R.T.; Karim, F.; Weis, J.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, C.; Vasquez, E.S. Optimization and structural stability of gold nanoparticle–antibody bioconjugates. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 15269–15279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, K.; Driskell, J.D. Quantifying bound and active antibodies conjugated to gold nanoparticles: A comprehensive and robust approach to evaluate immobilization chemistry. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 8253–8259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, G.; Tripathi, K.; Okyem, S.; Driskell, J.D. pH impacts the orientation of antibody adsorbed onto gold nanoparticles. Bioconjug. Chem. 2019, 30, 1182–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotnikov, D.V.; Byzova, N.A.; Zherdev, A.V.; Dzantiev, B.B. Retention of activity by antibodies immobilized on gold nanoparticles of different sizes: Fluorometric method of determination and comparative evaluation. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotnikov, D.V.; Byzova, N.A.; Zherdev, A.V.; Dzantiev, B.B. Ability of antibodies immobilized on gold nanoparticles to bind small antigen fluorescein. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sapsford, K.E.; Tyner, K.M.; Dair, B.J.; Deschamps, J.R.; Medintz, I.L. Analyzing nanomaterial bioconjugates: A review of current and emerging purification and characterization techniques. Anal. Chem. 2011, 83, 4453–4488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardena, H.S.N.; Liyanage, S.H.; Rathnayake, K.; Patel, U.; Yan, M. Analytical methods for characterization of nanomaterial surfaces. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 1889–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correira, J.M.; Handali, P.R.; Webb, L.J. Characterizing protein–surface and protein–nanoparticle conjugates: Activity, binding, and structure. J. Chem. Phys. 2022, 157, 090902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Hu, D.; Salmain, M.; Liedberg, B.; Boujday, S. Direct quantification of surface coverage of antibody in IgG-Gold nanoparticles conjugates. Talanta 2019, 204, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filbrun, S.L.; Driskell, J.D. A fluorescence-based method to directly quantify antibodies immobilized on gold nanoparticles. Analyst 2016, 141, 3851–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakowicz, J.R. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy, 3rd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Watt, R.M.; Voss, E.W., Jr. Mechanism of quenching of fluorescein by anti-fluorescein IgG antibodies. Immunochemistry 1977, 14, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotnikov, D.V.; Byzova, N.A.; Zherdev, A.V.; Dzantiev, B.B. Changes in antigen-binding ability of antibodies caused by immobilization on gold nanoparticles: A case study for monoclonal antibodies to fluorescein. Biointer. Res. Appl. Chem 2023, 13, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amina, S.J.; Guo, B. A review on the synthesis and functionalization of gold nanoparticles as a drug delivery vehicle. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 9823–9857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, K.; Dadashpour, M.; Gharibi, T.; Mellatyar, H.; Akbarzadeh, A. Biomedical applications of functionalized gold nanoparticles: A review. J. Clust. Sci. 2022, 33, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Buchman, J.T.; Rodriguez, R.S.; Ring, H.L.; He, J.; Bantz, K.C.; Haynes, C.L. Stabilization of silver and gold nanoparticles: Preservation and improvement of plasmonic functionalities. Chem. Rev. 2018, 119, 664–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simeonova, S.; Georgiev, P.; Exner, K.S.; Mihaylov, L.; Nihtianova, D.; Koynov, K.; Balashev, K. Kinetic study of gold nanoparticles synthesized in the presence of chitosan and citric acid. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2018, 557, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.A.; Wang, J.; Jasinski, J.B.; Achilefu, S. Fluorescence manipulation by gold nanoparticles: From complete quenching to extensive enhancement. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2011, 9, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Jo, E.J.; Kim, M.G. A label-free fluorescence immunoassay system for the sensitive detection of the mycotoxin, ochratoxin A. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 2304–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbán, J.; Mateos, E.; Cebolla, V.; Domínguez, A.; Delgado-Camón, A.; de Marcos, S.; Sanz-Vicente, I.; Sanz, V. The environmental effect on the fluorescence intensity in solution. An analytical model. Analyst 2009, 134, 2286–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, E.W., Jr.; Watt, R.M.; Weber, G. Solvent perturbation of the fluorescence of fluorescyl ligand bound to specific antibody fluorescence enhancement of antibody bound fluorescein (hapten) in deuterium oxide. Mol. Immunol. 1980, 17, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eftink, M.R. Fluorescence methods for studying equilibrium macromolecule-ligand interactions. Methods Enzymol. 1997, 278, 221–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leopold, L.F.; Tódor, I.S.; Diaconeasa, Z.; Rugină, D.; Ştefancu, A.; Leopold, N.; Coman, C. Assessment of PEG and BSA-PEG gold nanoparticles cellular interaction. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2017, 532, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manson, J.; Kumar, D.; Meenan, B.J.; Dixon, D. Polyethylene glycol functionalized gold nanoparticles: The influence of capping density on stability in various media. Gold Bull. 2011, 44, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevozhay, D.; Rauch, R.; Wang, Z.; Sokolov, K.V. Optimal size and PEG coating of gold nanoparticles for prolonged blood circulation: A statistical analysis of published data. Nanoscale Adv. 2025, 7, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Huang, X.; Liu, H.; Zan, F.; Ren, J. Colloidal stability of gold nanoparticles modified with thiol compounds: Bioconjugation and application in cancer cell imaging. Langmuir 2012, 28, 4464–4471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.K.; Uzunoglu, A.; Stanciu, L.A. Aminolated and thiolated PEG-covered gold nanoparticles with high stability and antiaggregation for lateral flow detection of bisphenol A. Small 2018, 14, 1702828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, Y.R.; Xu, J.X.; Amarasekara, D.L.; Hughes, A.C.; Abbood, I.; Fitzkee, N.C. Understanding the adsorption of peptides and proteins onto PEGylated gold nanoparticles. Molecules 2021, 26, 5788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awotunde, O.; Okyem, S.; Chikoti, R.; Driskell, J.D. Role of free thiol on protein adsorption to gold nanoparticles. Langmuir 2020, 36, 9241–9249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, K.; Forrest, J.A. Influence of particle size on the binding activity of proteins adsorbed onto gold nanoparticles. Langmuir 2012, 28, 2736–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotnikov, D.V.; Safenkova, I.V.; Zherdev, A.V.; Avdienko, V.G.; Kozlova, I.V.; Babayan, S.S.; Gergert, V.Y.; Dzantiev, B.B. A mechanism of gold nanoparticle aggregation by immunoglobulin G preparation. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaza-Bulseco, G.; Liu, H. Fragmentation of a recombinant monoclonal antibody at various pH. Pharm. Res. 2008, 25, 1881–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Álvarez, R.; Vallet-Regí, M. Hard and soft protein corona of nanomaterials: Analysis and relevance. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pederzoli, F.; Tosi, G.; Vandelli, M.A.; Belletti, D.; Forni, F.; Ruozi, B. Protein corona and nanoparticles: How can we investigate on? WIREs Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 9, e1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajipour, M.J.; Safavi-Sohi, R.; Sharifi, S.; Mahmoud, N.; Ashkarran, A.A.; Voke, E.; Serpooshan, V.; Ramezankhani, M.; Milani, A.S.; Landry, M.P.; et al. An overview of nanoparticle protein corona literature. Small 2023, 19, 2301838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casals, E.; Vitali, M.; Puntes, V. The nanoparticle-protein corona untold history (1907–2007). Nano Today 2024, 58, 102435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiese, S.; Papppenberger, A.; Friess, W.; Mahler, H.C. Shaken, not stirred: Mechanical stress testing of an IgG1 antibody. J. Pharm. Sci. 2008, 97, 4347–4366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frens, G. Controlled nucleation for the regulation of the particle size in monodisperse gold suspensions. Nat. Phys. Sci. 1973, 241, 20–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotnikov, D.V.; Zherdev, A.V.; Dzantiev, B.B. Development and application of a label-free fluorescence method for determining the composition of gold nanoparticle–protein conjugates. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 16, 907–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byzova, N.A.; Zherdev, A.V.; Pridvorova, S.M.; Dzantiev, B.B. Development of rapid immunochromatographic assay for D-dimer detection. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2019, 55, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Antibody Concentration, μg/mL (nM) | Maximum Concentration of Bound FAM, ng/mL (nM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Antibodies | GNP-Antibody Conjugate Before Centrifugation | Supernatant After Centrifugation | GNP-Antibody After Centrifugation | (Pellet + Supernatant) Sum | |

| 5 (33.3) | 15.8 (42.0) | 3.8 (10.1) | 0.6 (1.6) | 3.3 (8.8) | 3.9 (10.4) |

| 10 (66.7) | 31.0 (82.4) | 16.1 (42.8) | 8.0 (21.3) | 11.6 (30.8) | 19.6 (52.1) |

| 20 (133.3) | 70.2 (186.5) | 42.0 (111.6) | 27.6 (73.3) | 22.5 (59.8) | 50.1 (133.1) |

| Antibody Concentration, μg/mL (nM) | Maximum Concentration of Bound FAM, ng/mL (nM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Antibodies | GNP-Antibody Conjugate Before Centrifugation | Supernatant After Centrifugation | GNP-Antibody After Centrifugation | (Pellet + Supernatant) Sum | |

| 5 (33.3) | 15.8 (42.0) | 6.9 (18.3) * | 1.3 (3.5) | 1.6 (4.3) * | 2.9 (7.7) |

| 10 (66.7) | 33.6 (89.3) | 15.1 (40.1) | 7.7 (20.5) | 8.8 (23.4) | 16.5 (43.8) |

| 20 (133.3) | 67.9 (180.4) | 43.5 (115.6) | 32.0 (85.0) | 20.9 (55.5) | 52.9 (140.6) |

| Antibody Concentration, μg/mL | Proportion of Antibodies in the Supernatant (%) | Proportion of Antibodies in the Conjugate (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stabilizer—BSA 0.25% | Stabilizer—PEG-SH 0.25% | Stabilizer—BSA 0.25% | Stabilizer—PEG-SH 0.25% | |

| 5 | 3.8 | 8.2 | 96.2 | 91.8 |

| 10 | 25.8 | 22.9 | 74.2 | 77.1 |

| 20 | 39.3 | 47.1 | 60.7 | 52.9 |

| Concentration of Added Antibodies, μg/mL | Maximum Concentration of Bound FAM, ng/mL | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity of Antibodies in the Reaction Mixture *, % | Antibodies in the Conjugate, μg/mL | Activity of Conjugated Antibodies Before Centrifugation, % | Activity of Conjugated Antibodies After Centrifugation, % | |

| Stabilizer—BSA | ||||

| 5 | 24 | 4.8 | 21 | 22 |

| 10 | 52 | 7.4 | 35 | 50 |

| 20 | 60 | 12.1 | 34 | 53 |

| Stabilizer—PEG-SH | ||||

| 5 | 44 | 4.6 | 39 | 11 ** |

| 10 | 45 | 7.7 | 29 | 34 |

| 20 | 64 | 10.6 | 32 | 58 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sotnikov, D.V.; Agapov, A.S.; Zherdev, A.V.; Dzantiev, B.B. Reactivity of Antibodies Immobilized on Gold Nanoparticles: Fluorescence Quenching Study. Molecules 2026, 31, 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010183

Sotnikov DV, Agapov AS, Zherdev AV, Dzantiev BB. Reactivity of Antibodies Immobilized on Gold Nanoparticles: Fluorescence Quenching Study. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):183. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010183

Chicago/Turabian StyleSotnikov, Dmitriy V., Andrey S. Agapov, Anatoly V. Zherdev, and Boris B. Dzantiev. 2026. "Reactivity of Antibodies Immobilized on Gold Nanoparticles: Fluorescence Quenching Study" Molecules 31, no. 1: 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010183

APA StyleSotnikov, D. V., Agapov, A. S., Zherdev, A. V., & Dzantiev, B. B. (2026). Reactivity of Antibodies Immobilized on Gold Nanoparticles: Fluorescence Quenching Study. Molecules, 31(1), 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010183