Synthesis of Cobalt Hydroxychloride and Its Application as a Catalyst in the Condensation of Perimidines

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

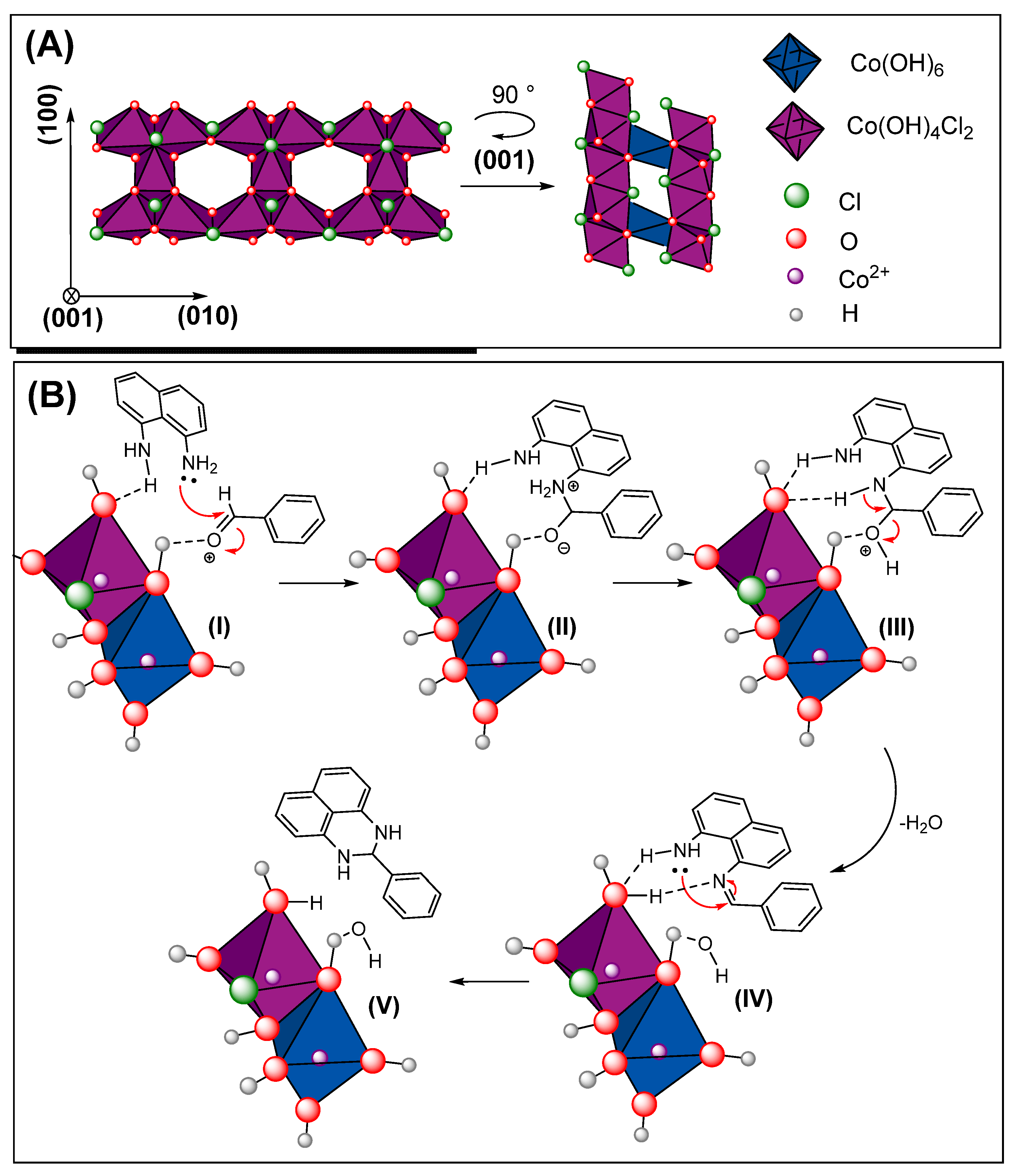

2.1. Cobalt Hydroxychloride [Co2(OH)3Cl] Characterization

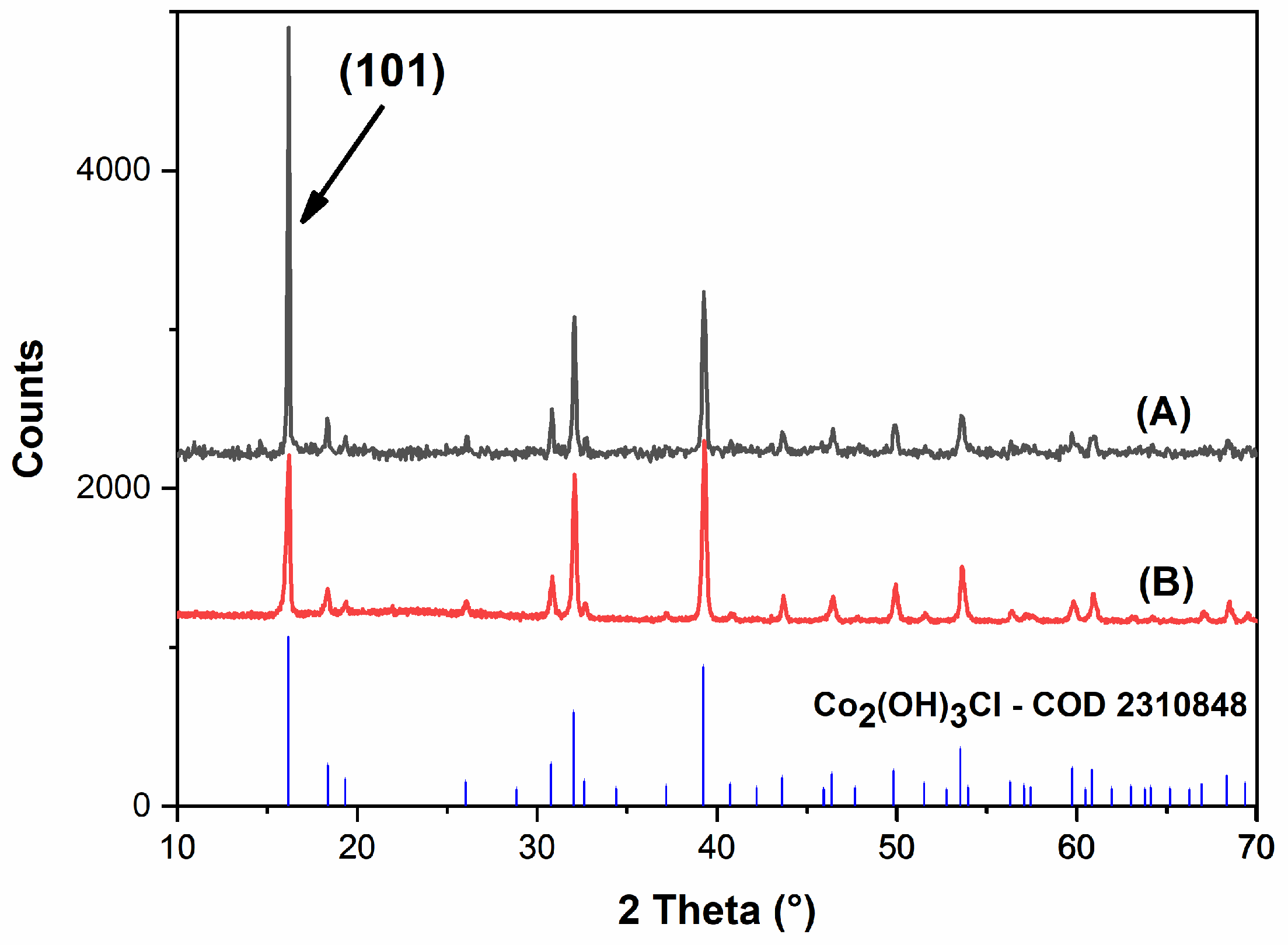

2.1.1. Structural and Phase Formation Characterization

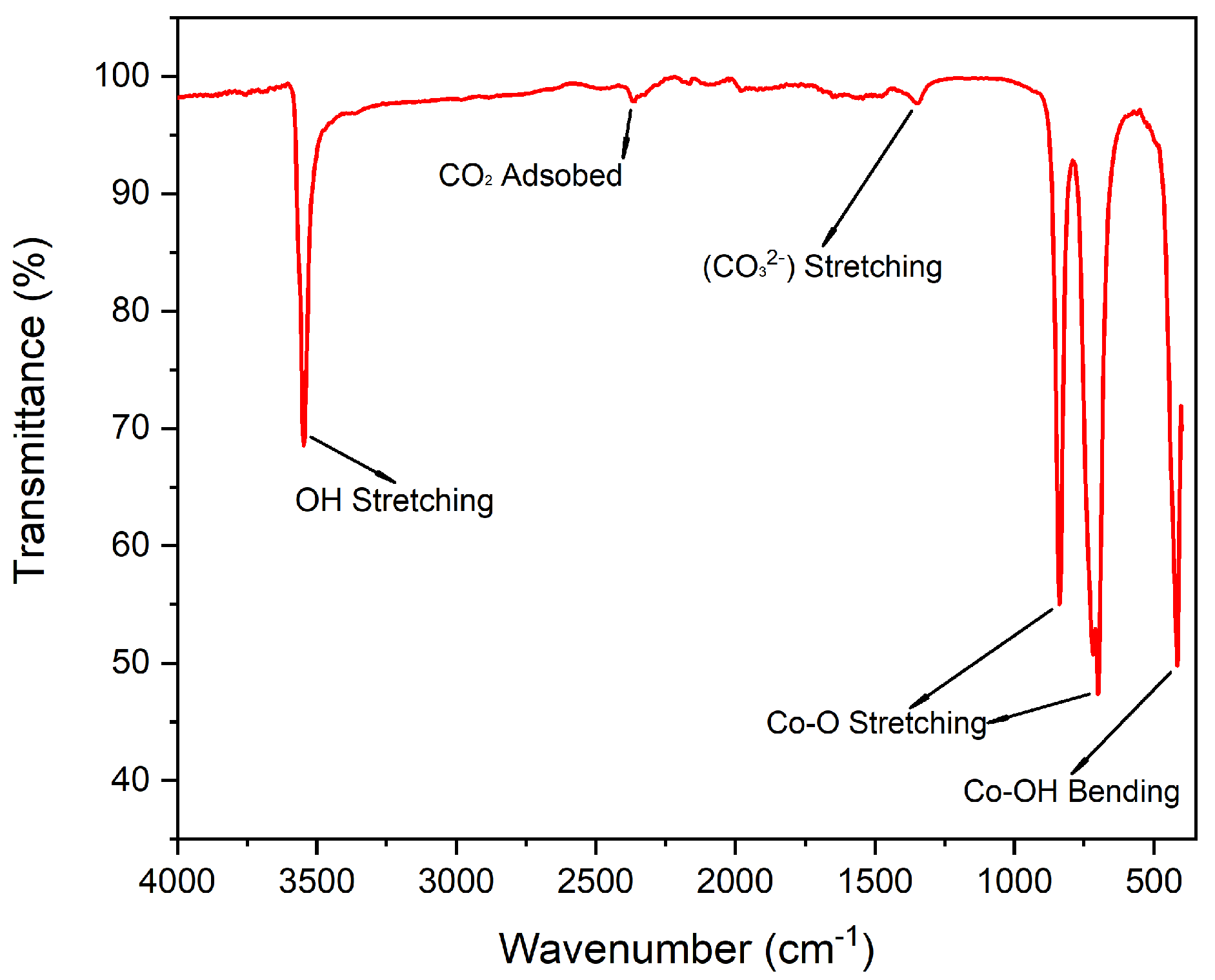

2.1.2. Vibrational Spectroscopy Analysis

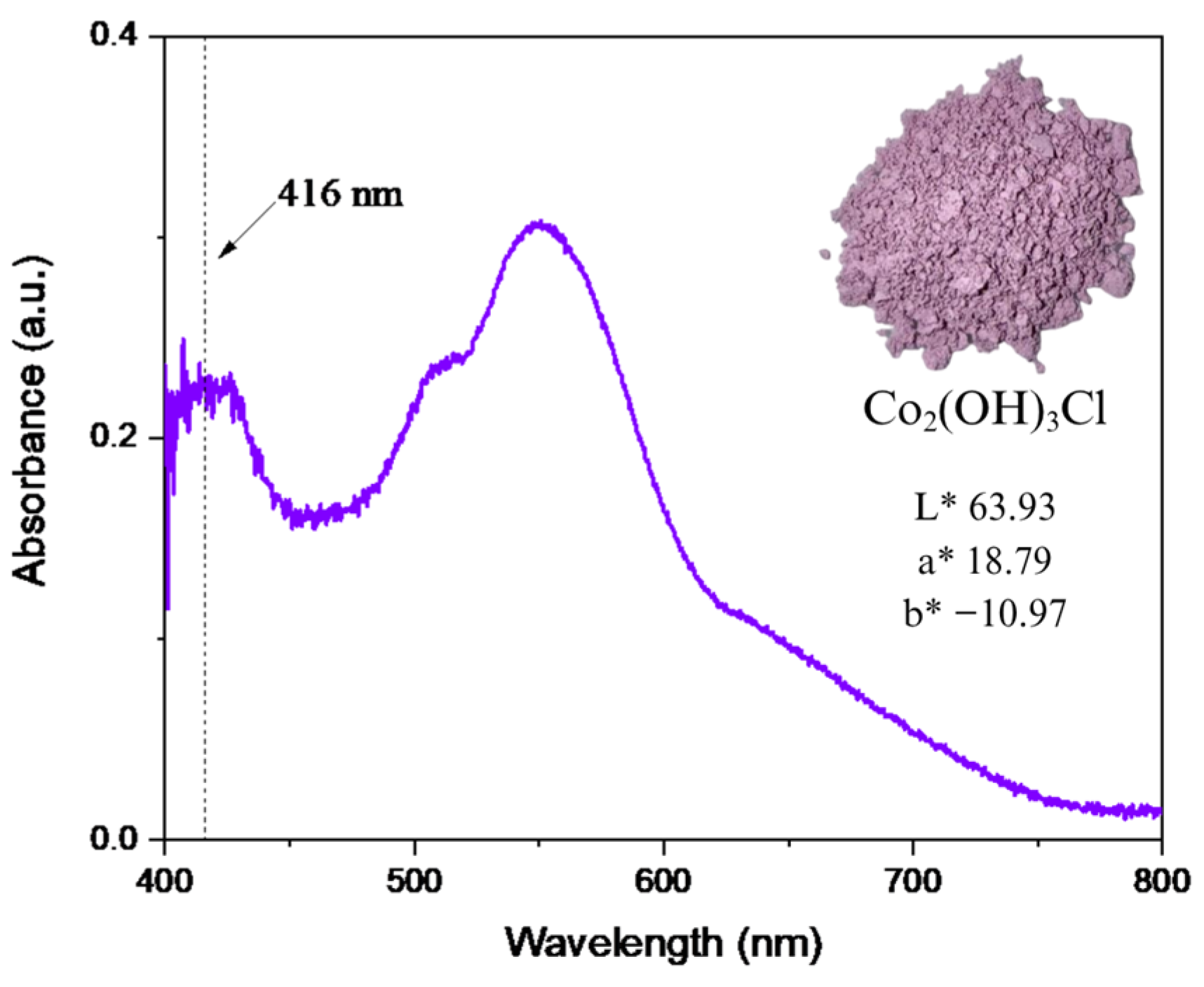

2.1.3. Electronic Behaviour

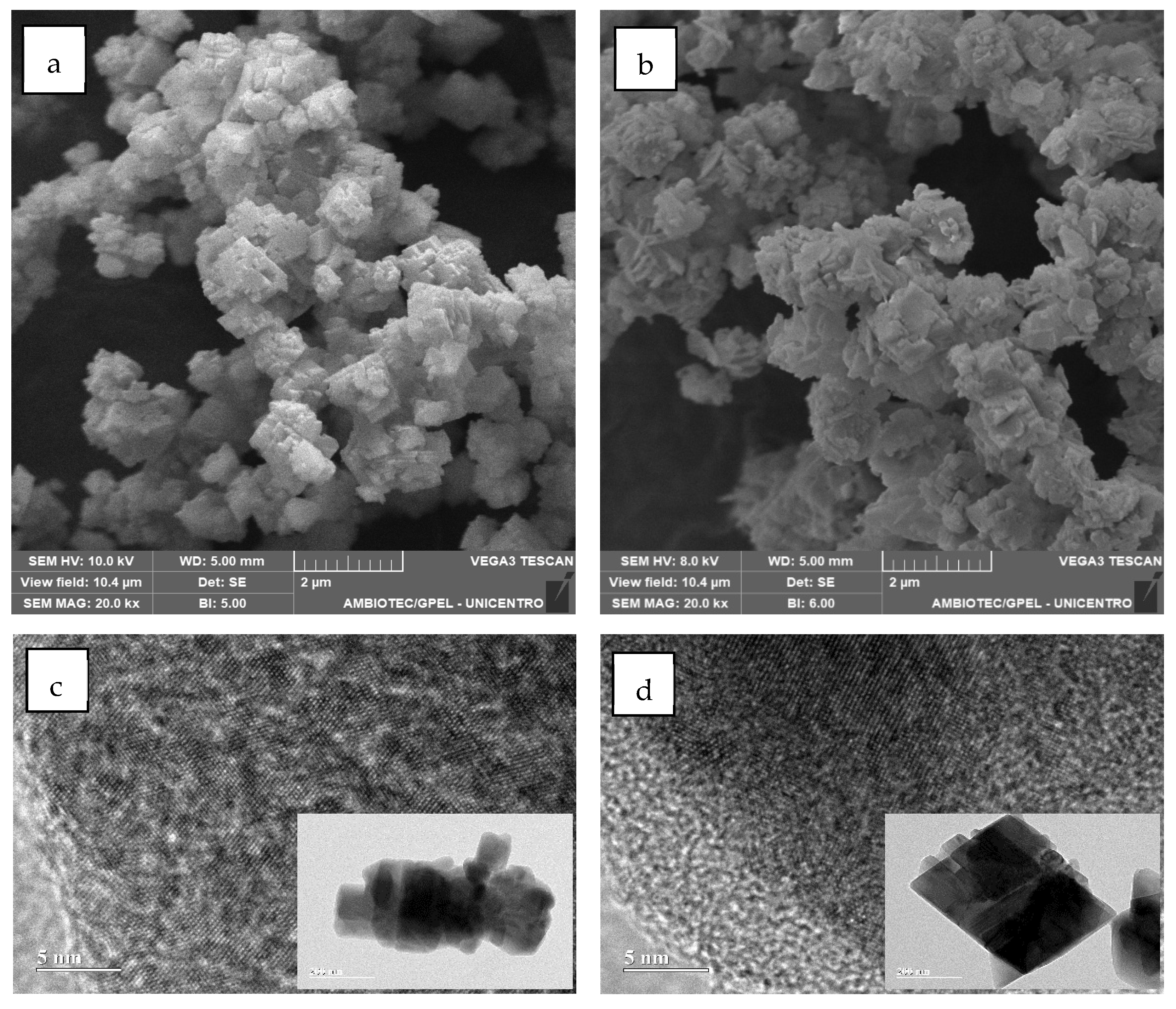

2.1.4. Morphological, Surface, and Chemical Analysis

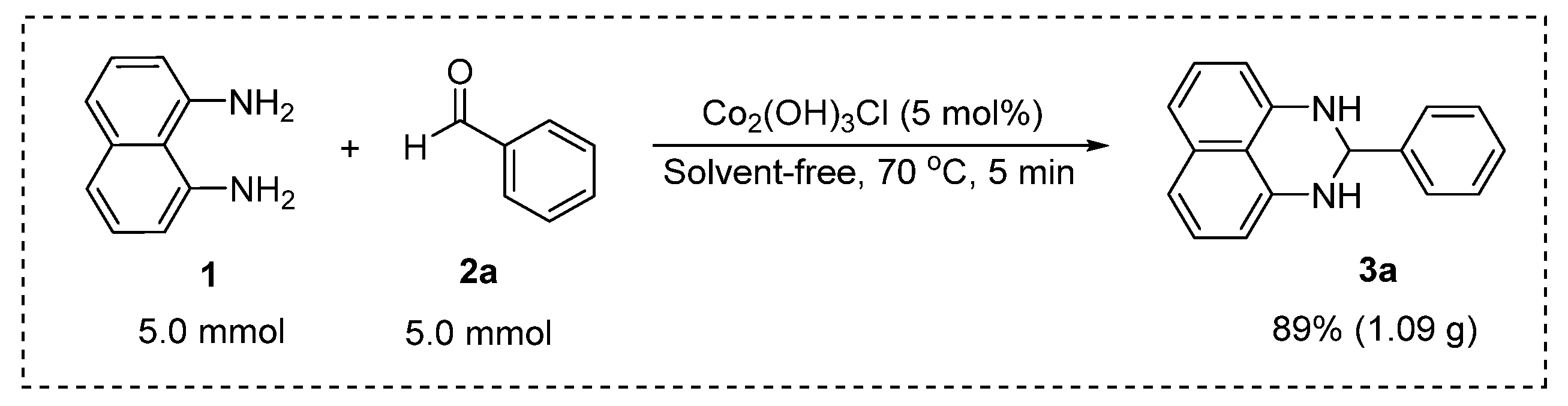

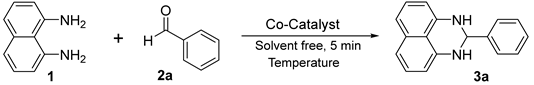

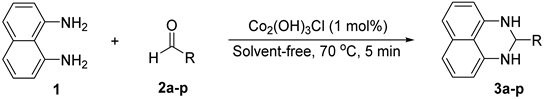

2.2. Synthesis of 2-Substituted 2,3-dihydro-1H-perimidines

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Reagents and Apparatus

3.1.1. Reagents and Characterization for [Co2(OH)3Cl]

3.1.2. Reagents and Characterization for 2,3-Dihydro-1H-perimidines

3.2. Experimental Procedures

3.2.1. Cobalt Hydroxichloride [Co2(OH)3Cl] Solid State Synthesis

3.2.2. Synthesis of 2-Substituted 2,3-dihydro-1H-permidine

3.2.3. Co2(OH)3Cl Recycling

3.2.4. Scale-Up Synthesis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Park, G.D.; Ko, Y.N.; Kang, Y.C. Electrochemical Properties of Cobalt Hydroxychloride Microspheres as a New Anode Material for Li-Ion Batteries. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 5785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kampf, A.R.; Sciberras, M.J.; Leverett, P.; Williams, P.A.; Malcherek, T.; Schlüter, J.; Welch, M.D.; Dini, M.; Molina Donoso, A.A. Paratacamite-(Mg), Cu3 (Mg,Cu)Cl2 (OH)6; a New Substituted Basic Copper Chloride Mineral from Camerones, Chile. Mineral. Mag. 2013, 77, 3113–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampf, A.R.; Sciberras, M.J.; Williams, P.A.; Dini, M.; Molina Donoso, A.A. Leverettite from the Torrecillas Mine, Iquique Provence, Chile: The Co-Analogue of Herbertsmithite. Mineral. Mag. 2013, 77, 3047–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, M.D.; Sciberras, M.J.; Williams, P.A.; Leverett, P.; Schlüter, J.; Malcherek, T. A Temperature-Induced Reversible Transformation between Paratacamite and Herbertsmithite. Phys. Chem. Miner. 2014, 41, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braithwaite, R.S.W.; Mereiter, K.; Paar, W.H.; Clark, A.M. Herbertsmithite, Cu3 Zn(OH)6 Cl2, a New Species, and the Definition of Paratacamite. Mineral. Mag. 2004, 68, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, S.; Thakur, A.; Thakur, R.; Bhatia, S.K.; Sharma, A.K. Multifaceted Potential Applicability of Hydrotalcite-Type Anionic Clays from Green Chemistry to Environmental Sustainability. Chemosphere 2022, 306, 135464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Tang, X.; Dai, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, A.; Yuan, Z.; Li, X. Layered Double Hydroxide Membrane with High Hydroxide Conductivity and Ion Selectivity for Energy Storage Device. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morais de Faria, J.; Alkimin Muniz, L.; Netto, J.F.Z.; Scheres Firak, D.; B. De Sousa, F.; da Silva Lisboa, F. Application of a Hybrid Material Formed by Layered Zinc Hydroxide Chloride Modified with Spiropyran in the Adsorption of Ca2+ from Water. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 631, 127738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaassis, A.Y.A.; Al-Jamal, W.T.; Strimaite, M.; Severic, M.; Williams, G.R. Biocompatible Hydroxy Double Salts as Delivery Matrices for Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Epileptic Drugs. Appl. Clay. Sci. 2022, 221, 106456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaassis, A.Y.A.; Xu, S.-M.; Guan, S.; Evans, D.G.; Wei, M.; Williams, G.R. Hydroxy Double Salts Loaded with Bioactive Ions: Synthesis, Intercalation Mechanisms, and Functional Performance. J. Solid State Chem. 2016, 238, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho, R.R., Jr.; Oliveira, A.F.; de Andrade, S.J.; da Silva Lisboa, F. Congo Red Dye Degradation by the Composite Zn(II)/Co(II) Layered Double Hydroxy Salt/Peanut Shell Biochar as Photocatalyst. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 44, 111924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuaicham, C.; Sekar, K.; Balakumar, V.; Zhang, L.; Trakulmututa, J.; Smith, S.M.; Sasaki, K. Fabrication of Hydrotalcite-like Copper Hydroxyl Salts as a Photocatalyst and Adsorbent for Hexavalent Chromium Removal. Minerals 2022, 12, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centi, G.; Perathoner, S. Catalysis by Layered Materials: A Review. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2008, 107, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arizaga, G.; Satyanarayana, K.; Wypych, F. Layered Hydroxide Salts: Synthesis, Properties and Potential Applications. Solid State Ion. 2007, 178, 1143–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jijoe, P.S.; Yashas, S.R.; Shivaraju, H.P. Fundamentals, Synthesis, Characterization and Environmental Applications of Layered Double Hydroxides: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 2643–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathee, G.; Kohli, S.; Singh, N.; Awasthi, A.; Chandra, R. Calcined Layered Double Hydroxides: Catalysts for Xanthene, 1,4-Dihydropyridine, and Polyhydroquinoline Derivative Synthesis. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 15673–15680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, P.K. Eco-Friendly Grinding Synthesis of a Double-Layered Nanomaterial and the Correlation between Its Basicity, Calcination and Catalytic Activity in the Green Synthesis of Novel Fused Pyrimidines. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 78409–78423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharali, D.; Devi, R.; Bharali, P.; Deka, R.C. Synthesis of High Surface Area Mixed Metal Oxide from the NiMgAl LDH Precursor for Nitro-Aldol Condensation Reaction. New J. Chem. 2015, 39, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, P.K. A Green Approach to the Synthesis of a Nano Catalyst and the Role of Basicity, Calcination, Catalytic Activity and Aging in the Green Synthesis of 2-Aryl Bezimidazoles, Benzothiazoles and Benzoxazoles. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 42000–42012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.S.R.; Nakhate, A.V.; Rasal, K.B.; Deshmukh, G.P.; Mannepalli, L.K. Oxidative Amidation of Benzaldehydes and Benzylamines with N -Substituted Formamides over a Co/Al Hydrotalcite-Derived Catalyst. New J. Chem. 2017, 41, 15268–15276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, C.S.; da Silva, F.R.; Marangoni, R.; Wypych, F.; Ramos, L.P. LDHs Instability in Esterification Reactions and Their Conversion to Catalytically Active Layered Carboxylates. Catal. Lett. 2012, 142, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagaki, S.; Machado, G.S.; Stival, J.F.; Henrique dos Santos, E.; Silva, G.M.; Wypych, F. Natural and Synthetic Layered Hydroxide Salts (LHS): Recent Advances and Application Perspectives Emphasizing Catalysis. Prog. Solid State Chem. 2021, 64, 100335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangoni, R.; Carvalho, R.E.; Machado, M.V.; Dos Santos, V.B.; Saba, S.; Botteselle, G.V.; Rafique, J. Layered Copper Hydroxide Salts as Catalyst for the “Click” Reaction and Their Application in Methyl Orange Photocatalytic Discoloration. Catalysts 2023, 13, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, M.; Warad, I.; Al-Resayes, S.; Zahin, M.; Ahmad, I.; Shakir, M. Syntheses, Physico-Chemical Studies and Antioxidant Activities of Transition Metal Complexes with a Perimidine Ligand. Z Anorg. Allg. Chem. 2012, 638, 881–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farghaly, T.A.; Abdallah, M.A.; Muhammad, Z.A. New 2-Heterocyclic Perimidines: Synthesis and Antimicrobial Activity. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2015, 41, 3937–3947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Melha, S. Confirmed Mechanism for 1,8-Diaminonaphthalene and Ethyl Aroylpyrovate Derivatives Reaction, DFT/B3LYP, and Antimicrobial Activity of the Products. J. Chem. 2018, 2018, 4086824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Banerjee, S.; Roy, P.; Sondhi, S.M.; Sharma, A. Solvent-Free Synthesis and Anticancer Activity Evaluation of Benzimidazole and Perimidine Derivatives. Mol. Divers. 2018, 22, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eldeab, H.A.; Eweas, A.F. A Greener Approach Synthesis and Docking Studies of Perimidine Derivatives as Potential Anticancer Agents. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2018, 55, 431–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassyouni, F.A.; Abu-Bakr, S.M.; Hegab, K.H.; El-Eraky, W.; El Beih, A.A.; Rehim, M.E.A. Synthesis of New Transition Metal Complexes of 1H-Perimidine Derivatives Having Antimicrobial and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2012, 38, 1527–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.-J.; Wang, X.-Z.; Cao, Q.; Gong, G.-H.; Quan, Z.-S. Design, Synthesis, Anti-Inflammatory Activity, and Molecular Docking Studies of Perimidine Derivatives Containing Triazole. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 4409–4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khopkar, S.; Shankarling, G. Squaric Acid: An Impressive Organocatalyst for the Synthesis of Biologically Relevant 2,3-Dihydro-1H-Perimidines in Water. J. Chem. Sci. 2020, 132, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobinikhaledi, A.; Steel, P.J. Synthesis of Perimidines Using Copper Nitrate as an Efficient Catalyst. Synth. React. Inorg. Met.-Org. Nano-Met. Chem. 2009, 39, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behbahani, F.K.; Golchin, F.M. A New Catalyst for the Synthesis of 2-Substituted Perimidines Catalysed by FePO4. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 2017, 11, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michiyuki, T.; Komeyama, K. Recent Advances in Four-Coordinated Planar Cobalt Catalysis in Organic Synthesis. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2020, 9, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohidi, M.M.; Paymard, B.; Vasquez-García, S.R.; Fernández-Quiroz, D. Recent Progress in Applications of Cobalt Catalysts in Organic Reactions. Tetrahedron 2023, 136, 133352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liandi, A.R.; Cahyana, A.H.; Kusumah, A.J.F.; Lupitasari, A.; Alfariza, D.N.; Nuraini, R.; Sari, R.W.; Kusumasari, F.C. Recent Trends of Spinel Ferrites (MFe2O4: Mn, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn) Applications as an Environmentally Friendly Catalyst in Multicomponent Reactions: A Review. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2023, 7, 100303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigolo, T.A.; de Campos, S.D.; Manarin, F.; Botteselle, G.V.; Brandão, P.; Amaral, A.A.; de Campos, E.A. Catalytic Properties of a Cobalt Metal–Organic Framework with a Zwitterionic Ligand Synthesized in Situ. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 15698–15703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Retizlaf, A.; de Souza Sikora, M.; Ivashita, F.F.; Schneider, R.; Botteselle, G.V.; Junior, H.E.Z. CoFe2O4 Magnetic Nanoparticles: Synthesis by Thermal Decomposition of 8-Hydroxyquinolinates, Characterization, and Application in Catalysis. MRS Commun. 2023, 13, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwob, T.; Ade, M.; Kempe, R. A Cobalt Catalyst Permits the Direct Hydrogenative Synthesis of 1 H-Perimidines from a Dinitroarene and an Aldehyde. ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 3013–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Yang, L.; Tang, S.; Li, L.; Wang, W.; Yuan, B.; Yang, G. Highly Efficient Acetalization and Ketalization Catalyzed by Cobaloxime under Solvent-Free Condition. Catalyst 2018, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobras, G.; Kasperczyk, K.; Jurczhyk, S.; Orlinska, B. N-Hydroxyphthalimide Supported on Silica Coated with Ionic Liquids Containing CoCl2 (SCILLs) as New Catalytic System for Solvent-Free Ethylbenzene Oxidation. Catalysts 2020, 10, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamier, W.M.; El-Telbani, E.M.; Syed, I.S.; Bakry, A.M. Cobalt Ferrite Nanoparticles: Highly Efficient Catalysts for the Biginelli Reaction. Ceramics 2025, 8, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javad, S.; Hossein, B.S.; Shiva, D.K. Cobalt Nanoparticles Promoted Highly Efficient One Pot Four-Component Synthesis of 1,4-Dihydropyridines under Solvent-Free Conditions. Chin. J. Catal. 2011, 32, 1850–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornquist, B.L.; Bueno, G.P.; Manzano Willing, J.C.; de Oliveira, I.M.; Stefani, H.A.; Rafique, J.; Saba, S.; Almeida Iglesias, B.; Botteselle, G.V.; Manarin, F. Ytterbium (III) triflate/sodium dodecyl sulfate: A versatile recyclable and water-tolerant catalyst for the synthesis of bis(indolyl)methanes (BIMs). ChemistrySelect 2018, 3, 6358–6363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, M.S.T.; Rafique, J.; Saba, S.; Azeredo, J.B.; Back, D.; Godoi, M.; Braga, A.L. Regioselective hydrothiolation of terminal acetylene catalyzed by magnetite (Fe3O4) nanoparticles. Synth. Commun. 2017, 47, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerner, C.V.; Scheide, M.R.; Nicoleti, C.R.; Durigon, D.C.; Idiarte, V.D.; Sousa, M.J.A.; Mendes, S.R.; Saba, S.; Neto, J.S.S.; Martins, G.M.; et al. Versatile electrochemical synthesis of selenylbenzo[b]furan derivatives through the cyclization of 2-alkynylphenols. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 880099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoi, M.; Botteselle, G.V.; Rafique, J.; Rocha, M.S.T.; Pena, J.M.; Braga, A.L. Solvent-free Fmoc protection of amines under microwave irradiation. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2013, 2, 746–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botteselle, G.V.; Elias, W.C.; Bettanin, L.; Canto, R.F.S.; Salin, D.N.O.; Barbosa, F.A.R.; Saba, S.; Gallardo, H.; Ciancaleoni, G.; Domingos, J.B.; et al. Catalytic Antioxidant Activity of Bis-Aniline-Derived Diselenides as GPx Mimics. Molecules 2021, 26, 4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, J.; Farias, G.; Saba, S.; Zapp, E.; Bellettini, I.C.; Momoli Salla, C.A.; Bechtold, I.H.; Scheide, M.R.; Santos Neto, J.S.; Monteiro de Souza Junior, D.; et al. Selenylated-oxadiazoles as promising DNA intercalators: Synthesis, electronic structure, DNA interaction and cleavage. Dyes Pigm. 2020, 180, 108519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Wolff, P.M. The Crystal Structure of Co2 (OH)3 Cl. Acta Crystallogr. 1953, 6, 359–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcherek, T.; Welch, M.D.; Williams, P.A. The Atacamite Family of Minerals—A Testbed for Quantum Spin Liquids. Acta Crystallogr. B Struct. Sci. Cryst. Eng. Mater. 2018, 74, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, N.; Rajamathi, M. High Selectivity in Anion Exchange Reactions of the Anionic Clay, Cobalt Hydroxynitrate. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 18077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, V.; Uthayakumar, M.; Karthick, R. Self-Assembled Cobalt Hydroxide Micro Flowers from Nanopetals: Structural, Fractal Analysis and Molecular Docking Study. Surf. Interfaces 2022, 32, 102163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diouane, Y.; Seijas-Da Silva, A.; Oestreicher, V.; Abellán, G. Exploring Pseudohalide Substitution in α-Cobalt-Based Layered Hydroxides. Dalton Trans. 2025, 54, 6538–6549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchis-Gual, R.; Hunt, D.; Jaramillo-Hernández, C.; Seijas-Da Silva, A.; Mizrahi, M.; Marini, C.; Oestreicher, V.; Abellán, G. Crystallographic and Geometrical Dependence of Water Oxidation Activity in Co-Based Layered Hydroxides. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 10351–10363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velu, S.; Suzuki, K.; Hashimoto, S.; Satoh, N.; Ohashi, F.; Tomura, S. The Effect of Cobalt on the Structural Properties and Reducibility of CuCoZnAl Layered Double Hydroxides and Their Thermally Derived Mixed Oxides. J. Mater. Chem. 2001, 11, 2049–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Liu, Z.; Takada, K.; Fukuda, K.; Ebina, Y.; Bando, Y.; Sasaki, T. Tetrahedral Co(II) Coordination in α-Type Cobalt Hydroxide: Rietveld Refinement and X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopy. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 3964–3969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neilson, J.R.; Schwenzer, B.; Seshadri, R.; Morse, D.E. Kinetic Control of Intralayer Cobalt Coordination in Layered Hydroxides: Co1−0.5 x oct Co x tet (OH)2 (Cl) x (H2O) n. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 11017–11023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajamathi, M.; Kamath, P.V. Urea Hydrolysis of Cobalt (II) Nitrate Melts: Synthesis of Novel Hydroxides and Hydroxynitrates. Int. J. Inorg. Mater. 2001, 3, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ann Harry, N.; Mary Cherian, R.; Radhika, S.; Anilkumar, G. A Novel Catalyst-Free, Eco-Friendly, on Water Protocol for the Synthesis of 2,3-Dihydro-1H-Perimidines. Tetrahedron. Lett. 2019, 60, 150946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, C.; Dos Santos, T.J.C.; Theisen, R.; Saba, S.; Rafique, J.; Gallina, A.L.; Botteselle, G.V. Direct Utilization of Waste Glycerol from Biodiesel Production for the Synthesis of Perimidines. Lett. Org. Chem. 2025, 22, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehm, H.P. Acidic and Basic Properties of Hydroxylated Metal Oxide Surfaces. Discuss. Faraday. Soc. 1971, 52, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.-S.; Fujita, T.; Yoshikai, N. Cobalt-Catalyzed, Room-Temperature Addition of Aromatic Imines to Alkynes via Directed C–H Bond Activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 17283–17295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrowfield, J.M.; Sargeson, A.M.; Springborg, J.; Snow, M.R.; Taylor, D. Imine Formation and Stability and Interligand Condensation with Cobalt(III) 1,2-Ethanediamine Complexes. Inorg. Chem. 1983, 22, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavani, F.; Trifirò, F.; Vaccari, A. Hydrotalcite-Type Anionic Clays: Preparation, Properties and Applications. Catal. Today 1991, 11, 173–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Li, J.; Zhu, H.; Xia, X.F.; Wang, D. Novel Recyclable Catalysts for Selective Synthesis of Substituted Perimidines and Aminopyrimidines. Catal. Lett. 2022, 153, 2388–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahiba, N.; Sethiya, A.; Soni, J.; Agarwal, S. Metal Free Sulfonic Acid Functionalized Carbon Catalyst for Green and Mechanochemical Synthesis of Perimidines. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 13076–13080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, K.; Mondal, A.; Pal, D.; Srivastava, H.K.; Srimani, D. Phosphine-Free Well-Defined Mn(I) Complex-Catalyzed Synthesis of Amine, Imine, and 2,3-Dihydro-1 H -Perimidine via Hydrogen Autotransfer or Acceptorless Dehydrogenative Coupling of Amine and Alcohol. Organometallics 2019, 38, 1815–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alama, M.; Lee, D.-U. Synthesis, spectroscopic and computational studies of 2-(thiophen-2-yl)-2,3-dihydro-1H-perimidine: An enzymes inhibition study. Comput. Biol. Chem. 2016, 64, 184–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harry, N.A.; Radhika, S.; Neetha, M.; Anilkumar, G. A novel catalyst-free mechanochemical protocol for the synthesis of 2,3-dihydro-1H-perimidines. J. Heterocyclic. Chem. 2020, 57, 2037–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadri, Z.; Behdbhani, F.K.; Keshmirizahe, E. Synthesis and Characterization of a Novel and Reusable Adenine Based Acidic Nanomagnetic Catalyst and Its Application in the Preparation of 2-Substituted-2,3-dihydro -1H-perimidines under Ultrasonic Irradiation and Solvent-Free Condition. Polycycl. Aromat. Comp. 2022, 43, 1898–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Catalyst (mol%) | T (°C) | Yield (%) b |

| 1 | Co2(OH)3SO4 (1) | 70 | 67 |

| 2 | Co2(OH)3NO3 (1) | 70 | 86 |

| 3 | Co2(OH)3Cl (1) | 70 | 96 |

| 4 | Co2(OH)3Cl (1) | 60 | 30 |

| 5 | Co2(OH)3Cl (5) | 70 | 94 |

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

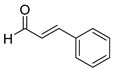

| Entry | Aldehyde | Product | Yield (%) b |

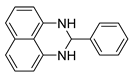

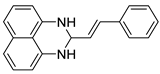

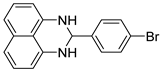

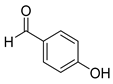

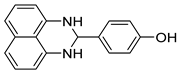

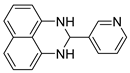

| 1 |  2a

2a |  3a

3a | 96 |

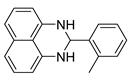

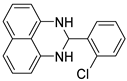

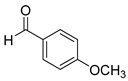

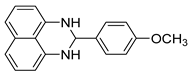

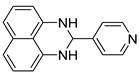

| 2 |  2b

2b |  3b

3b | 99 |

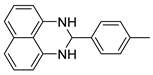

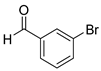

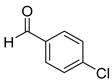

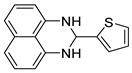

| 3 |  2c

2c |  3c

3c | 84 |

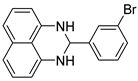

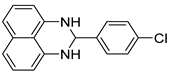

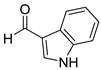

| 4 |  2d

2d |  3d

3d | 97 |

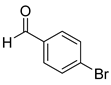

| 5 |  2e

2e |  3e

3e | 88 |

| 6 |  2f

2f |  3f

3f | 84 |

| 7 |  2g

2g |  3g

3g | 84 |

| 8 |  2h

2h |  3h

3h | 85 |

| 9 |  2i

2i |  3i

3i | 94 |

| 10 |  2j

2j |  3j

3j | 85 |

| 11 |  2k

2k |  3k

3k | 85 |

| 12 |  2l

2l |  3l

3l | 93 |

| 13 |  2m

2m |  3m

3m | 88 |

| 14 |  2n

2n |  3n

3n | 80 |

| 15 |  2o

2o |  3o

3o | 64 |

| 16 |  2p

2p |  3p

3p | 88 |

| Entry | Cycle | Yield (%) b |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1° | 96 |

| 2 | 2° | 90 |

| 3 | 3° | 71 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Siqueira, C.; Borges, G.R.; Portela, F.S.; Miks, M.E.; Marques, F.F.; Casagrande, G.A.; Saba, S.; Marangoni, R.; Rafique, J.; Botteselle, G.V. Synthesis of Cobalt Hydroxychloride and Its Application as a Catalyst in the Condensation of Perimidines. Molecules 2026, 31, 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010182

Siqueira C, Borges GR, Portela FS, Miks ME, Marques FF, Casagrande GA, Saba S, Marangoni R, Rafique J, Botteselle GV. Synthesis of Cobalt Hydroxychloride and Its Application as a Catalyst in the Condensation of Perimidines. Molecules. 2026; 31(1):182. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010182

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiqueira, Cássio, Gabriela R. Borges, Fernanda S. Portela, Maria E. Miks, Felipe F. Marques, Gleison A. Casagrande, Sumbal Saba, Rafael Marangoni, Jamal Rafique, and Giancarlo V. Botteselle. 2026. "Synthesis of Cobalt Hydroxychloride and Its Application as a Catalyst in the Condensation of Perimidines" Molecules 31, no. 1: 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010182

APA StyleSiqueira, C., Borges, G. R., Portela, F. S., Miks, M. E., Marques, F. F., Casagrande, G. A., Saba, S., Marangoni, R., Rafique, J., & Botteselle, G. V. (2026). Synthesis of Cobalt Hydroxychloride and Its Application as a Catalyst in the Condensation of Perimidines. Molecules, 31(1), 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules31010182