Abstract

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs) represent a class of incurable and progressive disorders characterized by the gradual degeneration of the structure and function of the nervous system, particularly the brain and spinal cord. A range of innovative therapeutic approaches is currently under investigation, such as stem cell-based therapies, gene-editing platforms such as CRISPR, and immunotherapies directed at pathogenic proteins. Moreover, phytochemicals such as β-caryophyllene and xanthohumol have demonstrated significant neuroprotective potential in preclinical models. These natural agents exert multifaceted effects by modulating neuroinflammatory pathways, oxidative stress responses, and aberrant protein aggregation—pathological mechanisms that are central to the development and progression of neurodegenerative disorders. Recent investigations have increasingly emphasized the optimization of the pharmacokinetic properties of β-caryophyllene and xanthohumol through the development of advanced drug-delivery systems, including polymer- and lipid-based nano- and microscale carriers. Such advancements not only enhance the bioavailability and therapeutic potential of these phytochemicals but also underscore their growing relevance as natural candidates in the development of future interventions for neurodegenerative disorders.

1. Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs) represent a class of incurable and progressive disorders characterized by the gradual degeneration of the structure and function of the nervous system, particularly the brain and spinal cord [1]. These conditions often lead to debilitating cognitive, behavioral, and motor impairments, significantly affecting the quality of life and placing a considerable burden on caregivers and healthcare systems. As life expectancy increases globally, the prevalence of neurodegenerative disorders is rising, prompting urgent research into their causes, classification, and treatment. Neurodegenerative disorders affect a substantial portion of the global population. Although advancing age is one of the most significant risk factor associated with the onset of NDDs, accumulating evidence suggests that the interplay between genetic susceptibility and environmental exposures also substantially contributes to disease pathogenesis and progression [1].

Several classifications exist regarding neurodegenerative diseases [2,3]. According to the affected protein pathology Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is associated with accumulation of amyloid-β and hyperphosphorylated tau, the Parkinson’s disease (PD) is associated with α-synuclein aggregates in Lewy bodies, the amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is associated with TDP-43 or SOD1 protein dysfunction and Huntington’s disease (HD) is associated with mutant huntingtin protein due to CAG triplet repeat expansion [4].

Regarding Clinical Manifestation the neurodegenerative disorders could be classified as cognitive disorders (AD, frontotemporal dementia) [5], motor disorders (PD, ALS, HD) [4,6], and mixed disorders (dementia with Lewy bodies, corticobasal degeneration) [7,8]. Parkinson’s disease is considered the second most prevalent progressive neurodegenerative disorder (ND) [9]. As mentioned above, this ND could be regarded as motor disorder. Its motor symptoms—include tremors, muscle rigidity, bradykinesia, and others. Individuals affected by PD suffer postural instability. However, PD is also associated with a range of non-motor manifestations, notably psychological disturbances such as depression, anxiety, and apathy, as well as cognitive decline and, in advanced stages, dementia [1].

The NDDs affect different predominant brain regions: hippocampus (AD), basal ganglia (Parkinson’s and Huntington’s disease), and motor neurons (ALS) [10]. The exact etiology of most NDDs still remains unclear. However, several risk factors are recognized, including genetic mutations (e.g., mutations in APP, PSEN1, and HTT genes), inflammation, and oxidative stress. Nowadays, it is considered that chronic brain inflammation may significantly accelerate neurodegeneration. Aging is also regarded as a risk factor for most NDDs. Environmental exposure to toxins or head injuries are also considered risk factors [1].

NDDs involve the progressive loss of neurons, the building blocks of the nervous system. This loss is often irreversible and occurs through various mechanisms, including protein misfolding, mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, excitotoxicity, and chronic inflammation. Many NDDs are associated with the accumulation of misfolded or abnormal proteins, such as amyloid-β in Alzheimer’s disease, α-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease, and huntingtin protein in Huntington’s disease. These proteins aggregate in brain tissue, forming plaques or tangles that disrupt neuronal communication and trigger cell death.

At present, NDDs remain incurable. The therapeutic strategies are primarily focused on alleviating symptoms and decelerating disease progression. Pharmacological interventions are frequently employed to manage clinical symptoms—acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are prescribed for AD, while levodopa remains the standard treatment for motor symptoms in PD. A major challenge still remains detecting NDDs in early stage and distinguishing between similar conditions due to overlapping symptoms [11]. Non-pharmacological interventions, including physiotherapy, cognitive rehabilitation, nutritional management, and psychosocial support, are essential for sustaining patients’ functional abilities and overall quality of life [12,13]. Moreover, herbal medicine presents promising strategies for slowing the progression of AD and alleviating its symptoms. The development and commercialization of plant-based medications are rapidly gaining traction, reflecting their growing scientific and economic importance in the healthcare industry. Several plant-derived products have undergone rigorous standardization, with their efficacy and safety validated for specific therapeutic applications. Notable examples include Ginkgo biloba, Bacopa monnieri, Salvia officinalis, Curcuma longa, Rosmarinus officinalis, Melissa officinalis, Galanthus nivalis, Lepidium meyenii, and Centella asiatica. A range of bioactive phytochemicals—including polyphenols, lipophilic vitamins, long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, isothiocyanates, and carotenoids—exhibit neuroprotective properties and have been implicated in modulating molecular pathways associated with Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis. These compounds represent promising candidates for the development of prophylactic and therapeutic interventions aimed at mitigating neurodegeneration [12,13].

A range of innovative therapeutic approaches is currently under investigation, such as stem cell-based therapies, gene-editing platforms such as CRISPR, and immunotherapies directed at pathogenic proteins. Moreover, phytochemicals such as β-caryophyllene and xanthohumol have demonstrated significant neuroprotective potential in preclinical models. These natural agents exert multifaceted effects by modulating neuroinflammatory pathways, oxidative stress responses, and aberrant protein aggregation—pathological mechanisms that are central to the development and progression of neurodegenerative disorders.

The aim of this review is to provide a comprehensive synthesis of current scientific findings on the neuroprotective potential of the natural compounds β-caryophyllene and xanthohumol. By examining their biological effects and recent advancements in optimization through nano- and microscale drug-delivery systems, current work offers a better understanding of their therapeutic relevance.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Studies Evaluating β-Caryophyllene Activity on NDDS

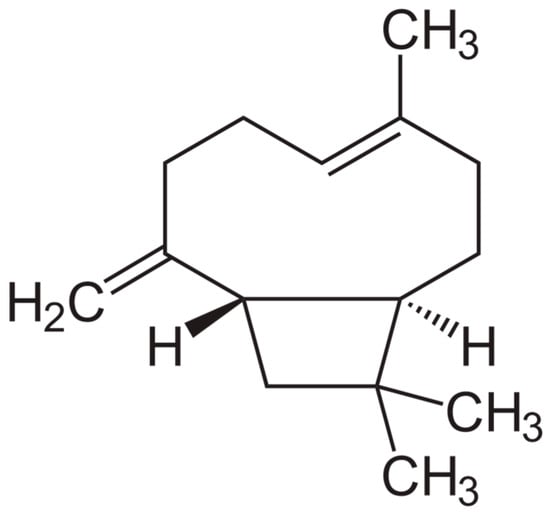

β-Caryophyllene (BCP) is a naturally occurring bicyclic sesquiterpene (Figure 1). Several plant species are known to be rich in BCP, including Syzygium aromaticum, the rhizome of Zingiber nimmonii, Helichrysum species, the leaves of Callistemon linearis, the aerial parts of Salvia verticillata, and the leaves of Humulus lupulus and Stachys lanata.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of β-caryophyllene.

The compound is a selective agonist of cannabinoid type 2 receptors (CB2-R). Unlike the compounds that interact with cannabinoid type 1 receptors (CB1), BCP lacks psychoactive effects due to its minimal CB1 affinity. Among its diverse biological roles, BCP demonstrates anti-inflammatory properties by suppressing key inflammatory mediators, including inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), and cyclooxygenases COX-1 and COX-2. Furthermore, its actions are partly mediated through activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, particularly PPAR-α and PPAR-γ.

Based on several in vivo and in vitro studies, it can be concluded that BCP possesses significant neuroprotective activity (Table 1). The possible mechanisms of neuroprotection are presented in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Studies presenting the pharmacological potential of β-caryophyllene, with a focus on its neuroprotective activity.

Figure 2.

β-Caryophyllene mechanisms of neuroprotection (created with BioRender https://BioRender.com/8ogb0lz, accessed on 6 August 2025)

Ojha, Shreesh, et al. demonstrated that the neuroprotective effect of the cannabinoid in a model of PD was mediated by its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities [27]. Its antioxidant activity was also established by Flores-Soto, M. E., et al., as the phytocannabinoid enhanced the activity of NAD(P)H quinone oxidoreductase (NQO1) [33]. The anti-inflammatory effect in a transgenic APP/PS1 AD model was confirmed by the activation of the CB2 receptor and PPARγ pathway by BCP [26]. Furthermore, BCP alleviated PD-associated BBB disruption and oxidative stress by reducing the selective death of dopaminergic neurons [36] and also relieved motor dysfunction [28].

Some in vitro studies demonstrated the neuroprotective activity in SH-SY5Y cell lines, as BCP enhanced cell viability, reduced the release of lactic dehydrogenase, decreased the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), and altered Caspase 3 activity [17,23]. Gouthamchandra, Kuluvar, et al. proved that standardized extract of BCP from black pepper exerted both neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory activities by suppressing COX-2, iNOS, and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway [20]. In vitro protective effects of BCP were also established in Aβ1–42-induced neuroinflammation, which is associated with AD [18]. In a model of AD, BCP showed neuronal protection and antagonism of Aβ neurotoxicity by inhibiting the “JAK2-STAT3-BACE1” signaling pathway [21]. In vivo and ex vivo research utilizing models of chronic MS, along with in vitro studies, demonstrated the neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory effects of BCP [24,29,31,34].

Askari, Vahid Reza, and Reza Shafiee-Nick demonstrated that BCP at low doses exerted its effects through CB2 receptors, while at higher concentrations the protective activity decreased and the PPAR-γ pathway was activated [19]. Another study revealed the neuritogenic potential of BCP, suggesting it may provide neuroprotection through a mechanism that does not involve cannabinoid receptors [15].

2.2. Studies Evaluating Xanthohumol Activity on NDDS

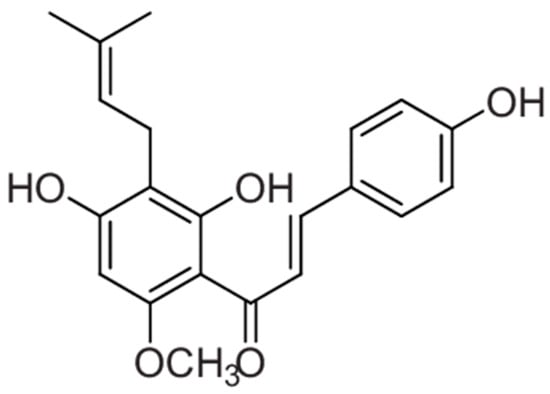

Xanthohumol ((E)-1-[2,4-dihydroxy-6-methoxy-3-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)phenyl]-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one, XAN, (Figure 3) is a relatively simple prenylated chalcone found in the Humulus lupulus L., Cannabaceae (hop plant), where it serves as the main prenylflavonoid in the female flowers, commonly known as hop cones. Hops are primarily used to impart bitterness and flavor to beer, making beer the main dietary source of XAN and similar compounds. In recent years, XAN and other prenylated chalcones have drawn considerable scientific interest for their potential role in cancer prevention. Meanwhile, hop-based herbal products are being sold—often marketed for purposes such as breast enhancement in women—without sufficient testing for safety or effectiveness. Although the market for such herbal products is small and not actively supported by the hop farming industry, growers are exploring new uses for hops and their constituents [38].

Figure 3.

Chemical structure of xanthohumol.

XAN has been shown to counteract cognitive impairments caused by a high-fat diet [39].

Hop extracts containing XAN promote sleep and neuroprotection, with enhanced potential for antioxidant and neuroprotective activity [40].

Xanthohumol, a prenylchalcone, shows significantly lower activity in stimulating neuronal differentiation in adult neural stem cells compared to pyranochalcones, suggesting that the pyrano ring is a key structural element. However, XAN has been reported to possess neuroprotective properties [41]. Moreover, XAN may enhance cognitive flexibility in mice [42]. According to Legette et al., XAN bioavailability in rats is dose-dependent, with higher doses resulting in lower relative bioavailability [43].

Xanthohumol has attracted significant attention for its neuroprotective potential in neurodegenerative diseases, particularly AD and PD. In vitro and in vivo studies are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

In vitro and in vivo studies on the neuroprotective potential of xanthohumol.

The findings summarized in the Table 2 provide a comprehensive overview of the multifaceted mechanisms through which XAN exerts its therapeutic effects, including modulation of protein aggregation, antioxidant activity, anti-inflammatory responses, neurotransmitter regulation, and enhancement of neuronal survival (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Biological activities of xanthohumol (created with BioRender. https://BioRender.com/v19cxxt, accessed on 6 August 2025).

A key neuroprotective mechanism of XAN involves the inhibition of pathological protein aggregation. XAN has been shown to directly inhibit the fibrillization tau protein and disaggregate existing fibrils, effectively reducing tau-induced apoptosis in cellular models of AD [48]. In parallel, XAN and its derivatives have demonstrated the ability to inhibit the aggregation and fibrillation of amyloid-β (Aβ1-42), forming less-toxic amorphous aggregates and preventing β-sheet formation, which is crucial in mitigating amyloid pathology [52,67].

Oxidative stress and neuroinflammation are pivotal contributors to neurodegeneration, and XAN has been consistently shown to activate the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, enhancing antioxidant defenses and reducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels [45,49,50,56,58,62]. These effects have been observed in models of ischemic stroke, LPS-induced inflammation, corticosterone-induced cytotoxicity, and iron overload. Furthermore, XAN reduced the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β, and inhibited signaling pathways such as NF-κB and p38-MAPK, suggesting its efficacy in curbing neuroinflammatory responses [54,55,56,58].

XAN also modulates several key signaling pathways associated with neurodegeneration. For instance, it regulates kinases such as GSK3β and phosphatases such as PP2A, which are involved in tau hyperphosphorylation, and influences endoplasmic reticulum stress and proteasome function [47]. In vivo studies in APP/PS1 transgenic mice revealed that XAN reduced excitotoxicity by decreasing glutamate levels, enhancing mitochondrial function, and promoting mitophagy, thereby supporting synaptic health and memory function [63]. Additionally, XAN was shown to suppress autophagosome maturation via VCP binding in certain contexts, although in others, it promoted autophagy and inhibited apoptosis, highlighting the complexity and context-specific nature of its effects [44,59].

Beyond its antioxidant and anti-apoptotic roles, XAN modulates the adenosinergic system by enhancing A1 receptor expression, which may reduce excitotoxicity—a critical process in AD progression [51,53]. Moreover, its ability to inhibit cholinesterases (AChE and BChE) supports its potential for symptomatic treatment of AD, akin to currently approved cholinergic drugs [46].

Emerging evidence also implicates the gut–brain axis in XAN’s neuroprotective mechanisms. Studies demonstrated that XAN modulates gut microbiota composition and metabolite profiles, thereby contributing to improved cognition and reduced neuroinflammation in AD models [53,55,64]. These findings open new avenues for XAN in systems-level interventions targeting neurodegeneration.

Despite its therapeutic promise, XAN’s clinical translation is hindered by poor oral bioavailability and limited BBB penetration. To address these limitations, several formulation strategies have been developed. Nanostructured lipid carriers, solid dispersions, self-emulsifying drug-delivery systems (SNEDDSs), and cyclodextrin complexes have significantly enhanced XAN’s solubility, stability, and brain bioavailability, resulting in improved cognitive and motor function in animal models [46,62,65,68].

XAN exhibits a broad spectrum of neuroprotective activities relevant to the pathology of neurodegenerative diseases. Its ability to target oxidative stress, inflammation, protein misfolding, synaptic dysfunction, and neurotransmitter imbalance makes it a compelling candidate for future therapeutic development. Continued research, particularly well-designed clinical studies and optimized drug-delivery systems, will be critical to unlocking XAN’s full potential in treating AD, PD, and related disorders.

Despite the promising neuroprotective potential of XAN in the management of PD, its clinical application is hindered by poor solubility, low bioavailability, and limited permeability across the BBB, ultimately resulting in reduced therapeutic efficacy. To address these challenges, a solid dispersion formulation of XAN was developed. This strategy significantly enhanced the delivery of XAN to the brain, leading to increased dopamine levels and reduced oxidative stress and inflammation—critical pathological features implicated in PD progression [69].

Similarly, XAN has demonstrated both neuroprotective and senolytic properties in the context of AD, yet its therapeutic impact remains constrained by the same pharmacokinetic limitations. To overcome these barriers, a self-nanoemulsifying drug-delivery system (SNEDDS) was formulated. In vivo studies demonstrated that XAN-loaded SNEDDS significantly improved cognitive and motor functions while reducing AChE activity, Aβ levels, oxidative stress, and neuroinflammation in rat models of AD [40]. These findings underscore the potential of advanced drug-delivery strategies in enhancing the bioavailability, stability, and therapeutic efficacy of XAN for neurodegenerative diseases.

2.3. Drug-Delivery Systems for β-Caryophyllene

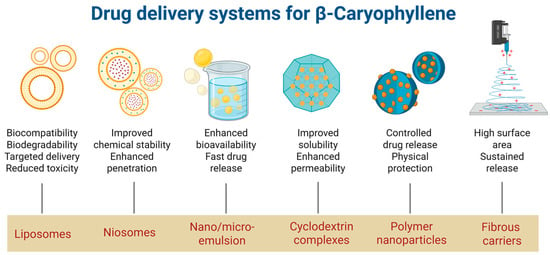

The pharmacological potential of β-caryophyllene as a neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic agent has generated considerable interest in developing effective delivery systems to overcome its inherent limitations, including low aqueous solubility, high lipophilicity, chemical instability, and extensive first-pass metabolism. In recent years, a variety of advanced carriers (Table 3), primarily nanotechnology-based, have been designed to improve its bioavailability, stability, and therapeutic efficacy (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Drug-delivery systems for β-Caryophyllene (created with BioRender. https://BioRender.com/0bywlj6, accessed on 7 August 2025).

Lipid-based nanocarriers are among the most widely investigated, leveraging BCP’s lipophilic nature. Nanostructured lipid carriers combine solid and liquid lipids into a matrix that entraps BCP, resulting in high encapsulation efficiency (87%), particle sizes of 200–250 nm, and sustained release profiles. These nanostructures enhance solubility, protect BCP from volatilization and oxidation, and improve membrane penetration, offering superior pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties compared to conventional formulations [70]. Similarly, self-emulsifying drug-delivery systems, which spontaneously form fine oil-in-water emulsions upon contact with aqueous media, encapsulate BCP in 40–50 nm droplets, significantly increasing its oral bioavailability, reducing inter-subject variability, and accelerating absorption [71]. Liposomes, particularly those prepared with soy phosphatidylcholine, encapsulate BCP in bilayer vesicles, improving dispersibility and cellular uptake. Studies have shown that BCP-loaded unilamellar and multilamellar liposomes enhance cytotoxic effects on cancer cells compared to free BCP, with stability and release profiles depending on the lipid-to-drug ratio [72]. A notable advancement in this area is Rephyll®, a liposomal BCP powder produced via nanofiber weaving technology, which demonstrated high encapsulation efficiency, sustained release, long shelf life, and improved muscle recovery in a clinical study [73]. Another liposomal formulation improved neurological outcomes and preserved BBB integrity in a rat model of subarachnoid hemorrhage, underscoring the neurovascular protective potential of liposomal BCP [74].

Emulsion-based carriers have also been extensively employed for BCP delivery. Both nanoemulsions and microemulsions, which are isotropic oil–surfactant–water mixtures with nanodroplets typically less than 200 nm, improve BCP stability, controlled release, and tissue distribution. Incorporating nanoemulsions into hydrogels enhances their handling and residence time at the target site, resulting in improved penetration and anti-inflammatory activity [75]. On the other hand, microemulsion-based hydrogels have demonstrated even greater entrapment, skin retention, and pharmacological efficacy, attributable to their thermodynamic stability and superior globule characteristics [76]. Microemulsions using copaiba oil-resin as both the oil phase and the active ingredient protected BCP from oxidation and enhanced its antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activity in vitro and in vivo [77]. A complementary approach involves using BCP itself as a multifunctional oily core in nanoemulsions. In another study, nanoemulsions co-loaded with indomethacin in a BCP-rich core exhibited synergistic anti-inflammatory effects, reduced the required doses, and demonstrated favorable physicochemical and safety profiles, highlighting the multifunctionality of BCP as both an active ingredient and carrier [78]. Furthermore, the choice of lipid plays a critical role in the performance of BCP-loaded carriers. Medium-chain triglyceride carriers exhibited superior stability, digestion, and bioaccessibility compared to those with longer or unsaturated fatty acids [79]. HLB-guided (hydrophilic lipophilic balance) formulation strategies have also been used to optimize nanoemulsion properties, producing stable, monodisperse systems with high encapsulation efficiency and biphasic release [80].

Cyclodextrin-based delivery systems have been explored to enhance the solubility and biological activity of BCP. Complexes of BCP with methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) increased solubility approximately tenfold, protected it from degradation, and enhanced its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and gastric protective effects in vivo [81]. A similar inclusion complex prepared by coprecipitation improved BCP’s solubility, stability, and oral bioavailability by 2.6-fold compared to free BCP [82].

In addition to lipid- and cyclodextrin-based carriers, niosomes have been adapted for BCP delivery. PLGA-modified, pH-sensitive niosomes achieved high encapsulation efficiency, controlled release in acidic environments, and enhanced cytotoxicity against triple-negative breast cancer cells, demonstrating their potential as advanced, responsive delivery systems [83].

Polymeric nanoparticles are another promising approach, offering controlled and targeted delivery. When modified with polyethylene glycol (PEG), nanoparticles stabilize BCP in a hydrophilic matrix, achieving 98% encapsulation and forming uniform particles (<150 nm), with potential for brain targeting [29]. PEG–PLGA nanoparticles (350 nm) enhance BCP stability, oral bioavailability, and pharmacokinetics, as PEG reduces mucoadhesion and extends circulation [84]. Chitosan-based nanoparticles, which are positively charged and bioadhesive, improve BCP activity, decrease toxicity, and increase tissue retention [85].

Beyond conventional carriers, other innovative delivery platforms have been reported. Intranasal nanoemulsions demonstrated efficient brain delivery of BCP in a seizure model, with high encapsulation efficiency, stability, and anticonvulsant effects [86]. Solid fibrous carriers, such as edible hemp, coconut, or rice fibers, provided rapid mucosal absorption and sustained oral release of BCP in a patented formulation (US10933016B2). Inhalation-based systems using handheld vaporizers enabled controlled pulmonary delivery of pure BCP (CN110225748A/WO2018094359A1), while clinically formulated products have been patented for schizophrenia (EP2827846A1), pain (EP4364730A1), multifunctional phospholipid–triglyceride systems (US11202765B2), and mild cognitive impairment (US11911346B2), illustrating the wide therapeutic potential of optimized BCP delivery strategies.

Apart from its role as an active compound, BCP has been investigated as a natural penetration enhancer. Studies have demonstrated that BCP fluidizes and disrupts stratum corneum lipids, increasing the permeability of hydrophilic drugs with minimal irritation [87]. Spectroscopic evidence confirmed its incorporation into bilayers, disturbing hydrophobic and subpolar regions, particularly in cholesterol-rich membranes, thereby increasing permeability [88]. Finally, a green, catalyst-free process for oxidizing BCP into caryophyllene oxide, described in patent WO2020069754A1, yields stable epoxide isomers suitable for pharmaceutical and cosmetic use, aligning with sustainable production approaches.

Table 3.

Drug-delivery systems for β-Caryophyllene, where ↑—increase and ↓—decrease.

Table 3.

Drug-delivery systems for β-Caryophyllene, where ↑—increase and ↓—decrease.

| Carrier Type | Polymer/Lipid | Impact on BCP Characteristics | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanostructured lipid carriers | Compritol 888ATO and linseed oil | ↑ Solubility, ↑ stability, and cumulative release | [70] |

| Lipid nanocarriers | Medium-chain triglyceride, coconut oil, cocoa butter, olive oil, soybean oil | ↑ Stability, ↑ bioaccessibility | [79] |

| Self-emulsifying drug-delivery system (VESIsorb®) | Medium-chain triglycerides, natural vegetable oils, PEG | ↑ Oral bioavailability, ↓ inter-individual variability, and fast absorption | [71] |

| Liposomes | Soybean phosphatidylcholine | ↑ Dispersibility, ↑ cellular uptake, | [72] |

| Phospholipids | Neuroprotection, BBB repair, ↓brain edema | [74] | |

| Liposomal powder (Rephyll®) | Phospholipids | ↑ Stability, sustained release, ↑ clinical efficacy | [73] |

| Hydrogel containing nanoemulsified BCP | Hydroxyethyl cellulose | ↑ Stability, controlled release, ↑anti-inflammatory activity | [75] |

| Microemulsion hydrogel | Isopropyl myristate, Phospholipon 90, Carbopol 940 | ↑ Skin permeation, ↑ anti-inflammatory activity | [76] |

| Microemulsion | Copaiba oil-resin | ↑ Antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activity | [77] |

| Nanoemulsion | Medium chain triglycerides (capric and caprylic acids) | Dose reduction, ↑ anti-inflammatory effect | [78] |

| Lecithin, oleylamine | Direct brain delivery, ↑ anticonvulsant effect | [86] | |

| Cyclodextrin inclusion complexes | Methyl-β-cyclodextrin β-cyclodextrin | ↑ Solubility, ↑ stability, ↑ oral bioavailability | [81,82] |

| PEGylated nanoparticles | PEG 400, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), poly-caprolactone (PCL), β-CD, and chitosan | Controlled release, ↑ stability, ↑ ability to permeate BBB | [89] |

| Nanoparticles | PEG, PLGA | ↑ Stability, prolonged circulation, ↑ oral bioavailability | [84] |

| Chitosan | ↑ Mucoadhesion and retention, ↓ toxicity | [85] | |

| Fibrous carriers | Natural fibers (hemp, coconut, rice) | ↑ mucosal absorption, controlled release, | US10933016B2 |

2.4. Drug-Delivery Systems for Xanthohumol

Due to its poor biopharmaceutical characteristics, mainly its low solubility in water, XAN exhibits insufficient oral resorption due to the restricted dissolution in body fluids [90]. Apart from this, it is also characterized by relatively short half-life and extensive liver biotransformation via processes such as oxidation, reduction, glucuronidation etc. This leads to the formation of multiple metabolites, some of which are bioactive, such as isoxanthohumol, while others do not contain the biological activity of the initial compound [43].

In general, enhancing the solubility of XAN is one of the most commonly used methods for improving its biopharmaceutical characteristics, namely the incorporation of XAN in a complex with cyclodextrins. They are cyclic oligosaccharides with a hydrophobic interior cavity and hydrophilic exterior. They are well-established carriers for enhancing the solubility of hydrophobic drugs and that of natural compounds [91]. In a recent study, Kirchinger et al. developed a xanthohumol/2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin complex and reported that, as the concentration of cyclodextrin was increased, a 650-fold increase in the solubility of XAN was observed. They also stated that the in vitro bioactivity of free xanthohumol and that of its complexed form were not significantly different, which showed that xanthohumol was released from the complex unchanged. Furthermore, the scientists conducted an in vivo pharmacokinetics test, which showed that XAN can be detected in the brain and the cerebrospinal fluid for up to 6 h post i.p. administration in mouse models [92].

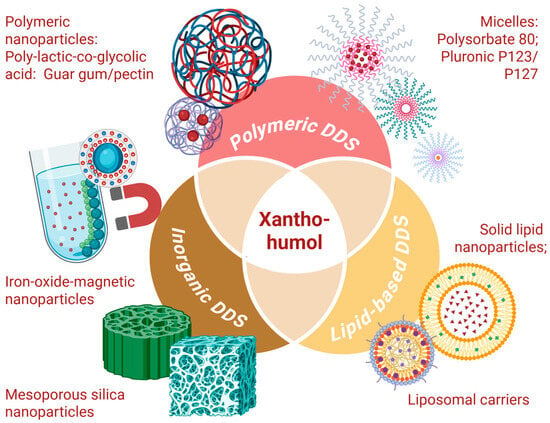

Another popular method for overcoming the poor biopharmaceutical characteristics of XAN is its incorporation in different nanoparticulate systems. They present a great opportunity to increase the solubility, bioavailability and stability of XAN, as well as alter its pharmacokinetics [93]. Over the years, multiple nano-sized drug-delivery systems (DDS), with incorporated XAN, have been developed, which can be classified as polymer-based drug-delivery systems, lipid-based DDS or inorganic-based DDS (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Drug-delivery systems for xanthohumol (created with BioRender. https://BioRender.com/7sxkqpq, accessed on 7 August 2025).

2.4.1. Polymeric DDS for Xanthohumol

Polymeric nanoparticulate systems have been broadly studied as carriers of XAN. The most common technique used is the micellar incorporation of XAN. In a recent study, Khayyal et al. developed micelles consisting of polysorbate 80, with incorporated XAN. The resulting micelles were compared in vivo for their anti-inflammatory effects with pure diclofenac sodium and non-micellized XAN. They reported a significantly higher anti-inflammatory effect of the micellar XAN compared to the native form, which was found not only to reduce the paw volume in arthritic rats but also to decrease the serum levels of cytokines TNF-α and IL-6. The effect was not significantly different from the effect of pure diclofenac sodium, which shows that the incorporation of xanthohumol in micelles significantly increases its efficacy due to the enhancement of its biopharmaceutical characteristics [94]. In another study, Ronka et al. developed Pluronic P123- and Pluronic F127-based micelles loaded with XAN and its primary metabolite, isoxanthohumol. They managed to synthesize micelles with a size of around 30 nm and extremely high encapsulation efficiency varying between 93.5% and 100%. However, the in vitro cytotoxicity assay and in vitro dissolution test showed relatively similar results between micellar-xanthohumol/isoxanthohumol and their native counterparts [95].

Apart from micellar incorporation, several other polymer-based drug-delivery systems have been developed as potential carriers of XAN. Poly-lactic-co-glycolic acid has been broadly utilized as a carrier for several classes of drugs due to its versatility, biocompatibility, and biodegradability [96]. Fonseca et al. (2021) developed xanthohumol-loaded PLGA nanoparticles as a new approach in the treatment of cutaneous melanoma [97]. The synthesized PLGA nanoparticles showed a relatively small average size of around 310 nm and loading efficiency of up to 90%. The developed structures showed sufficiently higher cytotoxic effects against malignant cutaneous cell-lines, compared to non-encapsulated XAN. This makes PLGA-based nanoparticles a suitable carrier for XAN, significantly increasing its therapeutic potential [97].

Similar nano-sized structures have been developed by Ghosh et al.; however, they were developed as a tool for the protection of the corneal epithelial cells. They reported that the formulated structures had a cytoprotective effect in in vitro oxidative stress injury in human corneal epithelial cells and significantly improved dry eye disease symptoms in a mouse model [98].

A polysaccharide-based drug-delivery system was also used as a potential carrier of xanthohumol. Hanmantrao et al. developed a guar gum/pectin based self-nanoemulsifying system for the colon-targeted drug-delivery of xanthohumol. The developed formulation showed increased xanthohumol solubility in water due to the transformation of its structure from crystalline into amorphous form. In addition, the formulation showed a 1.5-fold increase in the cytotoxic effect of XAN against Caco-2 cells, compared to free xanthohumol [99].

All the above-mentioned studies underscore the potency of polymer-based drug-delivery systems for XAN, enhancing its biopharmaceutical characteristics and its therapeutic potential.

2.4.2. Lipid-Based DDS for Xanthohumol

Apart from polymeric systems, different lipid-based formulations, such as liposomes and solid lipid nanoparticles, have also been reported as potential carriers of XAN. Solid lipid nanoparticles were found to be extensively utilized due to their advantages, including high colloidal stability, biocompatibility, and non-toxicity. Harish et al. developed xanthohumol-loaded solid lipid nanoparticles, which were reported to be in the 100 nm-range in terms of their size and high entrapment efficiency of XAN, around 80%. DSC (differential scanning calorimetry) and PXRD (powder x-ray diffraction) analyses showed that the xanthohumol structure shifted from a crystalline to an amorphous form; however, the release of xanthohumol was significantly slow; at 92 h, only 28% of the drug was released, which was probably due to the immobilization of xanthohumol in the lipid matrix. Although the drug release was slow, the formulated xanthohumol-loaded structures showed enhanced pharmacokinetic properties compared to non-encapsulated XAN [100].

In a recent study, Khandale et al. successfully addressed the issue of slow drug release by developing a novel solid lipid nanoparticle structure which showed a 5-fold increase in the in vitro drug release rate, compared to native xanthohumol. The formulation was tested in vivo in AlCl3-induced AD mouse models. The data showed no statistically significant differences between the animal groups treated with solid lipid nanoparticles loaded with xanthohumol and the standard treatment with donepezil. The pharmacokinetic study showed an 11.3-fold increase in the brain concentration of xanthohumol after incorporation in solid lipid nanoparticles, compared to the non-encapsulated xanthohumol, which shows the significance of the nano-sized drug-delivery systems in the transportation of molecules across the BBB [66].

Liposomal carriers of xanthohumol have also been developed previously. Buczek et al. investigated the effect of cyclodextrins on characteristics of xanthohumol-loaded liposomes. They reported that the complexation of xanthohumol with cyclodextrin modulates the temperature-dependent release of XAN from the synthesized structures [101].

2.4.3. Inorganic Carriers for Xanthohumol

While less studied compared to polymeric and lipidic DDSs, inorganic carriers receive great attention from the scientific community due to their unique optical and magnetic properties. They can be utilized for targeted drug delivery and for diagnostic purposes, which makes them highly versatile carriers of different active substances [102].

Iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles are one of the most extensively researched inorganic carriers for magnetically assisted drug delivery. Matthews et al. developed xanthohumol-loaded iron oxide nanoparticles coated with polyethylene glycol-block-allyl glycidyl ether, as a potential tool for the treatment of multiple myeloma. The prepared structures showed a high loading efficiency of 80%. The in vitro dissolution assay showed that <5% of xanthohumol was released after 48 h, whereas after stimulation for 15 min, > 40% of the incorporated xanthohumol was released. The developed structures showed high cytotoxic effects against multiple myeloma cells, which was additionally amplified by the generation of reactive oxygen species from the iron carriers [103].

Mesoporous silica nanoparticles are another attractive drug-delivery tool, possessing numerous advantages due to their porous structure and relatively high surface area, biocompatibility, and non-toxicity. Their pore-size is easily controlled and allows extensive surface modification, providing stimuli-responsive behavior, control of the drug release process, targeted delivery of genes, and diagnostic capabilities [104].

Krajnovic et al. developed XAN-loaded mesoporous silica nanoparticles and studied their cytotoxic effects against melanoma cells. They reported a relatively low entrapment efficiency of XAN, ranging between 8 and 17%. They tested the formulation in vitro for its antitumor activity. It was determined that the cell-death effect induced by the xanthohumol-loaded mesoporous particles involves inhibition of cell proliferation and an autophagic cell death mechanism, whereas free XAN induces apoptosis. This shows that the incorporation of xanthohumol in mesoporous silica nanoparticles can alter the antitumor effect of xanthohumol qualitatively as well as quantitatively [105].

2.5. Clinical Trials and Future Perspectives

Despite their promising biological effects, both BCP and xanthohumol are not yet FDA-approved pharmaceuticals, which may be related to some of their poor biopharmaceutical characteristics [93,106]. However, they remain subjects of significant scientific interest. A thorough search through of the database clinicaltrials.gov [107] shows that there are quite a few clinical trials for both compounds, which are presented in Table 4. Although none of the studies are directly related to neurodegenerative diseases, most of them aim to evaluate the potential of the molecules as antioxidants and anti-inflammatory drugs. Some of the trials aim to determine the pharmacokinetics of XAN and BCP, which can provide a better understanding of their biopharmaceutical behavior.

Table 4.

Clinical trials on β-caryophyllene and xanthohumol (clinicaltrials.gov).

Although β-caryophyllene and xanthohumol are generally considered safe and are available as dietary supplements, their long-term safety profiles in patients with neurodegenerative diseases are not well characterized. Preclinical and early clinical data suggest that these compounds have low toxicity; however, they both interact with important metabolic pathways. β-Caryophyllene acts as a CB2 receptor agonist and a PPAR-γ activator, which may influence immune responses and potentially interact with other anti-inflammatory or immunomodulatory medications. On the other hand, xanthohumol undergoes extensive metabolism in the liver, such as glucuronidation and oxidation, which raises concerns about interactions with cytochrome P450 substrates or drugs that have narrow therapeutic windows. Additionally, the possibility of additive effects with conventional antioxidants or cholinesterase inhibitors cannot be ruled out. To ensure safe clinical use, it is crucial to conduct thorough safety assessments, pharmacokinetic–pharmacodynamic studies, and a systematic evaluation of potential drug–drug interaction risks.

Regarding neuroprotection, research on β-caryophyllene and xanthohumol is still predominantly at the in vitro or in vivo animal study stage. To translate these findings into clinical practice, well-designed human trials are essential to confirm safety, efficacy, and optimal dosing. Achieving regulatory approval will require not only robust clinical evidence but also advanced formulation strategies to overcome bioavailability limitations. Polymer- and lipid-based nano/microsystems, micellar carriers, and self-emulsifying drug-delivery systems offer promising solutions. Future work should also explore biomarker-driven studies and potential synergistic effects in combination therapies. By integrating formulation science, clinical pharmacology, and neuroscience, the therapeutic potential of β-caryophyllene and xanthohumol could be fully realized, paving the way for novel strategies in neurodegenerative disease management.

3. Materials and Methods

The literature search aimed to identify studies investigating β-caryophyllene and xanthohumol as neuroprotective agents. The search strategy employed a combination of relevant keywords, including β-caryophyllene, xanthohumol, neuroprotective agents, neuroprotection, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, structure–activity relationship, drug-delivery systems, animal studies, cell culture studies and clinical trials. Only studies that specifically addressed NDDs and DDSs in relation to these two phytochemicals were considered eligible for inclusion. After the initial screening and removal of duplicates, the selected articles were read in full to confirm their relevance.

4. Conclusions

Neurodegenerative diseases currently have no cure, but β-caryophyllene and xanthohumol show promise as natural therapeutic agents. Preclinical studies suggest BCP may effectively target Parkinson’s disease and multiple sclerosis by activating the CB2 receptor and PPAR-γ, which modulate neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and blood–brain barrier integrity. It also reduces amyloid-β neurotoxicity and tau aggregation, although evidence for Alzheimer’s disease is less comprehensive. Conversely, XAN consistently demonstrates efficacy in Alzheimer’s models by inhibiting amyloid-β and tau aggregation, reducing excitotoxicity, activating the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, and modulating cholinesterase activity. While both compounds share neuroprotective mechanisms, such as anti-inflammatory signaling and antioxidant defense, BCP primarily targets immune pathways, whereas XAN focuses on protein aggregation and redox balance, guiding disease-focused development. At present, BCP and XAN cannot yet be classified as established therapeutic drugs. Rather, they should be regarded as bioactive natural modulators with pronounced neuroprotective properties, holding promise as lead structures or precursors for rational drug design. While no pharmaceutical drug products based on these molecules have yet been registered, β-caryophyllene and xanthohumol are already available as dietary supplements, and the interest in them is steadily growing. This is further supported by the numerous studies in recent years aiming to confirm their efficacy and to develop suitable drug formulations that can enhance their pharmacokinetic characteristics. In this regard, polymer- and lipid-based nano- and microscale drug-delivery systems have emerged as particularly promising carriers for β-caryophyllene and xanthohumol. It is probably only a matter of time before these formulations successfully pass clinical trials and become effective therapeutic strategies for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.I., Z.D., V.T. and P.S.; methodology, S.I. and P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.I., Z.D., V.T., P.S. and R.B.; writing—review and editing, S.I. and P.K.; visualization, S.I. and P.K.; supervision, S.I. and P.K.; project administration, S.I. and P.K.; funding acquisition, S.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union—NextGenerationEU, through the National Recovery and Resilience Plan of the Republic of Bulgaria, project No. BG-RRP-2.004-0007-C01.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| XAN | Xanthohumol |

| NDDs | Neurodegenerative diseases |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| ALS | amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| BCP | β-Caryophyllene |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| CB2 | Cannabinoid receptor 2 |

| HLB | Hydrophilic lipophilic balance |

| MβCD | Methyl-β-cyclodextrin |

| MS | Multiple sclerosis |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| PLGA | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid |

| PEG | Polyethylene glycol |

| PCL | Poly-caprolactone |

| PPARγ | Peroxisome proliferatoractivated receptor-γ |

| PVA | Polyvinyl alcohol |

| TC | Trans-caryophyllene |

| TNBC | Triple-negative breast cancer |

| CD | Cyclodextrin |

| DDS | Drug-delivery system |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor α |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

| PXRD | Powder x-ray diffraction |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

References

- Lamptey, R.N.L.; Chaulagain, B.; Trivedi, R.; Gothwal, A.; Layek, B.; Singh, J. A Review of the Common Neurodegenerative Disorders: Current Therapeutic Approaches and the Potential Role of Nanotherapeutics. IJMS 2022, 23, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, G.G. Concepts and Classification of Neurodegenerative Diseases. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 145, pp. 301–307. ISBN 978-0-12-802395-2. [Google Scholar]

- Relja, M. Pathophysiology and Classification of Neurodegenerative Diseases. EJIFCC 2004, 15, 97–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, G.P.; Dorsey, R.; Gusella, J.F.; Hayden, M.R.; Kay, C.; Leavitt, B.R.; Nance, M.; Ross, C.A.; Scahill, R.I.; Wetzel, R.; et al. Huntington Disease. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015, 1, 15005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, N.; Robbins, T.W.; Rowe, J.B. The Role of Noradrenaline in Cognition and Cognitive Disorders. Brain 2021, 144, 2243–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postuma, R.B.; Aarsland, D.; Barone, P.; Burn, D.J.; Hawkes, C.H.; Oertel, W.; Ziemssen, T. Identifying Prodromal Parkinson’s Disease: Pre-Motor Disorders in Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2012, 27, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasanuki, K.; Josephs, K.A.; Ferman, T.J.; Murray, M.E.; Koga, S.; Konno, T.; Sakae, N.; Parks, A.; Uitti, R.J.; Van Gerpen, J.A.; et al. Diffuse Lewy Body Disease Manifesting as Corticobasal Syndrome: A Rare Form of Lewy Body Disease. Neurology 2018, 91, e268–e279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranza, G.M.; Whitwell, J.L.; Kovacs, G.G.; Lang, A.E. Corticobasal Degeneration. In International Review of Neurobiology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 149, pp. 87–136. ISBN 978-0-12-817730-3. [Google Scholar]

- Rahul; Siddique, Y. Neurodegenerative Disorders and the Current State, Pathophysiology, andManagement of Parkinson’s Disease. CNSNDDT 2022, 21, 574–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Advani, D.; Yadav, D.; Ambasta, R.K.; Kumar, P. Dissecting the Relationship Between Neuropsychiatric and Neurodegenerative Disorders. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 60, 6476–6529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chopade, P.; Chopade, N.; Zhao, Z.; Mitragotri, S.; Liao, R.; Chandran Suja, V. Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s Disease Therapies in the Clinic. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2023, 8, e10367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bordoloi, S.; Pathak, K.; Devi, M.; Saikia, R.; Das, J.; Kashyap, V.H.; Das, D.; Ahmad, M.Z.; Abdel-Wahab, B.A. Some Promising Medicinal Plants Used in Alzheimer’s Disease: An Ethnopharmacological Perspective. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavan, M.; Hanachi, P.; de la Luz Cádiz-Gurrea, M.; Segura Carretero, A.; Mirjalili, M.H. Natural Phenolic Compounds with Neuroprotective Effects. Neurochem. Res. 2024, 49, 306–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assis, L.C.; Straliotto, M.R.; Engel, D.; Hort, M.A.; Dutra, R.C.; Bem, A.F. de β-Caryophyllene Protects the C6 Glioma Cells against Glutamate-Induced Excitotoxicity through the Nrf2 Pathway. Neuroscience 2014, 279, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, N.A.G.; Martins, N.M.; Sisti, F.M.; Fernandes, L.S.; Ferreira, R.S.; de Freitas, O.; Santos, A.C. The Cannabinoid Beta-Caryophyllene (BCP) Induces Neuritogenesis in PC12 Cells by a Cannabinoid-Receptor-Independent Mechanism. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2017, 261, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, B.; Guo, S. Trans-Caryophyllene Inhibits Amyloid β (Aβ) Oligomer-Induced Neuroinflammation in BV-2 Microglial Cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017, 51, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Ma, W.; Du, J. β-Caryophyllene (BCP) Ameliorates MPP+ Induced Cytotoxicity. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 103, 1086–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, V.R.; Shafiee-Nick, R. Promising Neuroprotective Effects of β-Caryophyllene against LPS-Induced Oligodendrocyte Toxicity: A Mechanistic Study. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2019, 159, 154–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, V.R.; Shafiee-Nick, R. The Protective Effects of β-Caryophyllene on LPS-Induced Primary Microglia M1/M2 Imbalance: A Mechanistic Evaluation. Life Sci. 2019, 219, 40–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouthamchandra, K.; Venkataramana, S.H.; Sathish, A.; Amritharaj; Basavegowda, L.H.; Puttaswamy, N.; Kodimule, S.P. Anti-Inflammatory and Neuroprotective Activity of Viphyllin a Standardized Extract of β-Caryophyllene from Black Pepper (Piper nigrum L.) and Its Associated Mechanisms in Mouse Macrophage Cells and Human Neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y Cells. Fortune J. Health Sci. 2024, 7, 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, Q.; Wang, S.; Liao, Z.; Jin, H.; Huang, S.; Hong, X.; Liu, Y.; Pang, J.; Shen, Q.; et al. The Food Additive β-Caryophyllene Exerts Its Neuroprotective Effects Through the JAK2-STAT3-BACE1 Pathway. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 14, 814432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbaraki, A.; Dindar, Z.; Mousavi-Jarrahi, Z.; Ghasemi, A.; Moeini, Z.; Evini, M.; Saboury, A.A.; Seyedarabi, A. The Novel Anti-Fibrillary Effects of Volatile Compounds α-Asarone and β-Caryophyllene on Tau Protein: Towards Promising Therapeutic Agents for Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 271, 132401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathod, S.S.; Agrawal, Y.O. β-Caryophyllene (CB2 Agonist) Mitigates Rotenone-Induced Neurotoxicity and Apoptosis in SH-SY5Y Neuroblastoma Cells via Modulation of GSK-3β/NRF2/HO-1 Axis. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontes, L.B.A.; Dias, D.D.S.; Aarestrup, B.J.V.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Da Silva Filho, A.A.; do Amaral Corrêa, J.O. β-Caryophyllene Ameliorates the Development of Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis in C57BL/6 Mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 91, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, K.D.C.; Paz, M.F.C.J.; Oliveira Santos, J.V.D.; da Silva, F.C.C.; Tchekalarova, J.D.; Salehi, B.; Islam, M.T.; Setzer, W.N.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; de Castro e Sousa, J.M.; et al. Anxiety Therapeutic Interventions of β-Caryophyllene: A Laboratory-Based Study. Nat. Product. Commun. 2020, 15, 1934578X20962229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Dong, Z.; Liu, S. β-Caryophyllene Ameliorates the Alzheimer-Like Phenotype in APP/PS1 Mice through CB2 Receptor Activation and the PPARγ Pathway. Pharmacology 2014, 94, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojha, S.; Javed, H.; Azimullah, S.; Haque, M.E. β-Caryophyllene, a Phytocannabinoid Attenuates Oxidative Stress, Neuroinflammation, Glial Activation, and Salvages Dopaminergic Neurons in a Rat Model of Parkinson Disease. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2016, 418, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viveros-Paredes, J.M.; González-Castañeda, R.E.; Gertsch, J.; Chaparro-Huerta, V.; López-Roa, R.I.; Vázquez-Valls, E.; Beas-Zarate, C.; Camins-Espuny, A.; Flores-Soto, M.E. Neuroprotective Effects of β-Caryophyllene against Dopaminergic Neuron Injury in a Murine Model of Parkinson’s Disease Induced by MPTP. Pharmaceuticals 2017, 10, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, T.B.; Barbosa, W.L.R.; Vieira, J.L.F.; Raposo, N.R.B.; Dutra, R.C. (−)-β-Caryophyllene, a CB2 Receptor-Selective Phytocannabinoid, Suppresses Motor Paralysis and Neuroinflammation in a Murine Model of Multiple Sclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, J.; Teng, Z.; Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Ma, L.; Wang, F.; Tian, X.; An, R.; Yang, M.; Zhang, Q.; et al. β-Caryophyllene/Hydroxypropyl-β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex Improves Cognitive Deficits in Rats with Vascular Dementia through the Cannabinoid Receptor Type 2-Mediated Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesquita, H.L.; Fontes, L.B.A.; Cinsa, L.A.; Filho, A.A.D.S.; Nagato, A.C.; Aarestrup, B.J.V.; do Amaral Corrêa, J.O.; Aarestrup, F.M. β-Caryophyllene Causes Remyelination and Modifies Cytokines Expression in C57BL/6 Mice with Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. J. App Pharm. Sci. 2019, 9, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kanojia, U.; Chaturbhuj, S.G.; Sankhe, R.; Das, M.; Surubhotla, R.; Krishnadas, N.; Gourishetti, K.; Nayak, P.G.; Kishore, A. Beta-Caryophyllene, a CB2R Selective Agonist, Protects Against Cognitive Impairment Caused by Neuro-Inflammation and Not in Dementia Due to Ageing Induced by Mitochondrial Dysfunction. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2021, 20, 963–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores-Soto, M.E.; Corona-Angeles, J.A.; Tejeda-Martinez, A.R.; Flores-Guzman, P.A.; Luna-Mujica, I.; Chaparro-Huerta, V.; Viveros-Paredes, J.M. β-Caryophyllene Exerts Protective Antioxidant Effects through the Activation of NQO1 in the MPTP Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2021, 742, 135534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askari, V.R.; Baradaran Rahimi, V.; Shafiee-Nick, R. Low Doses of β-Caryophyllene Reduced Clinical and Paraclinical Parameters of an Autoimmune Animal Model of Multiple Sclerosis: Investigating the Role of CB2 Receptors in Inflammation by Lymphocytes and Microglial. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand-Rubalcava, P.A.; Tejeda-Martínez, A.R.; González-Reynoso, O.; Nápoles-Medina, A.Y.; Chaparro-Huerta, V.; Flores-Soto, M.E. β-Caryophyllene Decreases Neuroinflammation and Exerts Neuroprotection of Dopaminergic Neurons in a Model of Hemiparkinsonism through Inhibition of the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Park. Relat. Disord. 2023, 117, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Molina, A.R.; Tejeda-Martínez, A.R.; Viveros-Paredes, J.M.; Chaparro-Huerta, V.; Urmeneta-Ortíz, M.F.; Ramírez-Jirano, L.J.; Flores-Soto, M.E. Beta-Caryophyllene Inhibits the Permeability of the Blood–Brain Barrier in MPTP-Induced Parkinsonism. Neurología 2025, 40, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, S.J.; Gomez-Pinilla, F.; Ling, P.-R. Beta-Caryophyllene, An Anti-Inflammatory Natural Compound, Improves Cognition. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2021, 3, 31–43. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, J.F.; Page, J.E. Xanthohumol and Related Prenylflavonoids from Hops and Beer: To Your Good Health! Phytochemistry 2004, 65, 1317–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, P.; Holden, S.; Paraiso, I.L.; Sudhakar, R.; McQuesten, C.; Choi, J.; Miranda, C.L.; Maier, C.S.; Bobe, G.; Stevens, J.F.; et al. ApoE Isoform-Dependent Effects of Xanthohumol on High Fat Diet-Induced Cognitive Impairments and Hippocampal Metabolic Pathways. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 954980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, B.; Park, C.W.; Ahn, Y.; Hong, K.-B.; Cho, H.-J.; Lee, J.H.; Jo, K.; Suh, H.J. Effect of Hop Mixture Containing Xanthohumol on Sleep Enhancement in a Mouse Model and ROS Scavenging Effect in Oxidative Stress-Induced HT22 Cells. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, e29922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urmann, C.; Bieler, L.; Priglinger, E.; Aigner, L.; Couillard-Despres, S.; Riepl, H.M. Neuroregenerative Potential of Prenyl- and Pyranochalcones: A Structure–Activity Study. J. Nat. Prod. 2021, 84, 2675–2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamzow, D.R.; Elias, V.; Legette, L.L.; Choi, J.; Stevens, J.F.; Magnusson, K.R. Xanthohumol Improved Cognitive Flexibility in Young Mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2014, 275, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legette, L.; Ma, L.; Reed, R.L.; Miranda, C.L.; Christensen, J.M.; Rodriguez-Proteau, R.; Stevens, J.F. Pharmacokinetics of Xanthohumol and Metabolites in Rats after Oral and Intravenous Administration. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2012, 56, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasazawa, Y.; Kanagaki, S.; Tashiro, E.; Nogawa, T.; Muroi, M.; Kondoh, Y.; Osada, H.; Imoto, M. Xanthohumol Impairs Autophagosome Maturation through Direct Inhibition of Valosin-Containing Protein. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012, 7, 892–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Zhang, B.; Ge, C.; Peng, S.; Fang, J. Xanthohumol, a Polyphenol Chalcone Present in Hops, Activating Nrf2 Enzymes To Confer Protection against Oxidative Damage in PC12 Cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 1521–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, I.E.; Jedrejek, D.; Senol, F.S.; Salmas, R.E.; Durdagi, S.; Kowalska, I.; Pecio, L.; Oleszek, W. Molecular Modeling and in Vitro Approaches towards Cholinesterase Inhibitory Effect of Some Natural Xanthohumol, Naringenin, and Acyl Phloroglucinol Derivatives. Phytomedicine 2018, 42, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, P.; Wang, S.; Song, F.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, F.; Huang, X.; Liu, J.; et al. The Prenylflavonoid Xanthohumol Reduces Alzheimer-Like Changes and Modulates Multiple Pathogenic Molecular Pathways in the Neuro2a/APPswe Cell Model of AD. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Wu, Q.; Yao, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhong, W.; Liu, Q.; Xiao, S. Xanthohumol Inhibits Tau Protein Aggregation and Protects Cells against Tau Aggregates. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 7865–7874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, F.; Zhang, B.; Hou, Y.; Yao, J.; Xu, Q.; Xu, J.; Fang, J. Xanthohumol Analogues as Potent Nrf2 Activators against Oxidative Stress Mediated Damages of PC12 Cells. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 2956–2966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoso, F.; Ramírez, V.T.; Golubeva, A.V.; Moloney, G.M.; Stanton, C.; Dinan, T.G.; Cryan, J.F. Naturally Derived Polyphenols Protect Against Corticosterone-Induced Changes in Primary Cortical Neurons. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019, 22, 765–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, P.; Albasanz, J.L.; Martín, M. Modulation of Adenosine Receptors by Hops and Xanthohumol in Cell Cultures. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2021, 12, 2373–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molteni, L.; Bruzzone, C.; Ami, D.; De Luigi, A.; Colombo, L.; Moretti, L.; Natalello, A.; Palmioli, A.; Airoldi, C. Xanthohumol Destabilizes the Structure of Amyloid-β (Aβ) Oligomers and Promotes the Formation of High-Molecular-Weight Amorphous Aggregates. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 319, 145720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejero, A.; León-Navarro, D.A.; Martín, M. Effect of Xanthohumol, a Bioactive Natural Compound from Hops, on Adenosine Pathway in Rat C6 Glioma and Human SH-SY5Y Neuroblastoma Cell Lines. Nutrients 2024, 16, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, T.-L.; Hsu, C.-K.; Lu, W.-J.; Hsieh, C.-Y.; Hsiao, G.; Chou, D.-S.; Wu, G.-J.; Sheu, J.-R. Neuroprotective Effects of Xanthohumol, a Prenylated Flavonoid from Hops (Humulus lupulus), in Ischemic Stroke of Rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 1937–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rancán, L.; Paredes, S.D.; García, I.; Muñoz, P.; García, C.; López De Hontanar, G.; De La Fuente, M.; Vara, E.; Tresguerres, J.A.F. Protective Effect of Xanthohumol against Age-Related Brain Damage. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2017, 49, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Cao, Y.; Lu, X.; Wang, J.; Saitgareeva, A.; Kong, X.; Song, C.; Li, J.; Tian, K.; Zhang, S.; et al. Xanthohumol Protects Neuron from Cerebral Ischemia Injury in Experimental Stroke. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 2417–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.; Ho, Y.H.; Hung, C.F.; Kuo, J.R.; Wang, S.J. Xanthohumol, an Active Constituent from Hope, Affords Protection against Kainic Acid-Induced Excitotoxicity in Rats. Neurochem. Int. 2020, 133, 104629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.U.; Ali, T.; Hao, Q.; He, K.; Li, W.; Ullah, N.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Li, S. Xanthohumol Attenuates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Depressive Like Behavior in Mice: Involvement of NF-κB/Nrf2 Signaling Pathways. Neurochem. Res. 2021, 46, 3135–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.-L.; Zhang, J.-B.; Guo, Y.-X.; Xia, T.-S.; Xu, L.-C.; Rahmand, K.; Wang, G.-P.; Li, X.-J.; Han, T.; Wang, N.-N.; et al. Xanthohumol Ameliorates Memory Impairment and Reduces the Deposition of β-Amyloid in APP/PS1 Mice via Regulating the mTOR/LC3II and Bax/Bcl-2 Signalling Pathways. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2021, 73, 1230–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; He, K.; Wu, D.; Zhou, L.; Li, G.; Lin, Z.; Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Pui Man Hoi, M. Natural Dietary Compound Xanthohumol Regulates the Gut Microbiota and Its Metabolic Profile in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Molecules 2022, 27, 1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shao, J.; Qiao, R.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Cao, W. Xanthohumol Improves Cognitive Impairment by Regulating miRNA-532-3p/Mpped1 in Ovariectomized Mice. Psychopharmacology 2023, 240, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao-Lei, S.; Tian-Shuang, X.; Yi-Ping, J.; Na-Ni, W.; Ling-Chuan, X.; Ting, H.; Hai-Liang, X. Humulus lupulus L. Extract and Its Active Constituent Xanthohumol Attenuate Oxidative Stress and Nerve Injury Induced by Iron Overload via Activating AKT/GSK3β and Nrf2/NQO1 Pathways. J. Nat. Med. 2023, 77, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.-F.; Pan, S.-Y.; Chu, J.-Y.; Liu, J.-J.; Duan, T.-T.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, W.; Wang, Z.-M.; Liu, W.; Zeng, Y. Xanthohumol Protects Against Neuronal Excitotoxicity and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in APP/PS1 Mice: An Omics-Based Study. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chen, X.; Zhao, J.; Yang, C.; Huang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J. Protective Signature of Xanthohumol on Cognitive Function of APP/PS1 Mice: A Urine Metabolomics Approach by Age. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1423060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Chen, X.; Yang, C.; Lin, Z.; Huang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J. Preventive Effects of Xanthohumol in APP/PS1 Mice Based on Multi-Omics Atlas. Brain Res. Bull. 2025, 224, 111316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandale, N.; Birla, D.; Alam, M.S.; Bashir, B.; Vishwas, S.; Kumar, A.; Potale, Y.; Gupta, G.; Negi, P.; Alam, A.; et al. Quality by Design Endorsed Fabrication of Xanthohumol Loaded Solid Nanostructured Lipid Carrier Based Powder for Effective Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease in Rats. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2025, 107, 106792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ho, S.-L.; Poon, C.-Y.; Yan, T.; Li, H.-W.; Wong, M.S. Amyloid-β Aggregation Inhibitory and Neuroprotective Effects of Xanthohumol and Its Derivatives for Alzheimer’s Diseases. CAR 2019, 16, 836–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, B.; Singh, S.K.; Gulati, M.; Vishwas, S.; Dua, K. Xanthohumol Loaded Self-Nano Emulsifying Drug Delivery System: Harnessing Neuroprotective Effects in Alzheimer’s Disease Management. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, e087955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Khandale, N.; Birla, D.; Bashir, B.; Vishwas, S.; Kulkarni, M.P.; Rajput, R.P.; Pandey, N.K.; Loebenberg, R.; Davies, N.M.; et al. Formulation and Optimization of Xanthohumol Loaded Solid Dispersion for Effective Treatment of Parkinson’s Disease in Rats: In Vitro and in Vivo Assessment. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 102, 106385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazwani, M.; Hani, U.; Alqarni, M.H.; Alam, A. Beta Caryophyllene-Loaded Nanostructured Lipid Carriers for Topical Management of Skin Disorders: Statistical Optimization, In Vitro and Dermatokinetic Evaluation. Gels 2023, 9, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mödinger, Y.; Knaub, K.; Dharsono, T.; Wacker, R.; Meyrat, R.; Land, M.H.; Petraglia, A.L.; Schön, C. Enhanced Oral Bioavailability of β-Caryophyllene in Healthy Subjects Using the VESIsorb® Formulation Technology, a Novel Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery System (SEDDS). Molecules 2022, 27, 2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Sotto, A.; Paolicelli, P.; Nardoni, M.; Abete, L.; Garzoli, S.; Di Giacomo, S.; Mazzanti, G.; Casadei, M.A.; Petralito, S. SPC Liposomes as Possible Delivery Systems for Improving Bioavailability of the Natural Sesquiterpene β-Caryophyllene: Lamellarity and Drug-Loading as Key Features for a Rational Drug Delivery Design. Pharmaceutics 2018, 10, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amalraj, A.; Jacob, J.; Varma, K.; Gopi, S. Preparation and Characterization of Liposomal β-Caryophyllene (Rephyll) by Nanofiber Weaving Technology and Its Effects on Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness (DOMS) in Humans: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Crossover-Designed, and Placebo-Controlled Study. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 24045–24056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Teng, Z.; Liu, D.; Wang, Y.; Lou, J.; Dong, Z. β-Caryophyllene Liposomes Attenuate Neurovascular Unit Damage After Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in Rats. Neurochem. Res. 2020, 45, 1758–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parisotto-Peterle, J.; Bidone, J.; Lucca, L.G.; Araújo, G.D.M.S.; Falkembach, M.C.; Da Silva Marques, M.; Horn, A.P.; Dos Santos, M.K.; Da Veiga, V.F.; Limberger, R.P.; et al. Healing Activity of Hydrogel Containing Nanoemulsified β-Caryophyllene. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 148, 105318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharthi, S.; Ziora, Z.M.; Mustafa, G.; Chaubey, P.; El Kirdasy, A.F.; Alotaibi, G. β-Caryophyllene-Loaded Microemulsion-Based Topical Hydrogel: A Promising Carrier to Enhance the Analgesic and Anti-Inflammatory Outcomes. Gels 2023, 9, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira Neves, J.K.; Apolinário, A.C.; Alcantara Saraiva, K.L.; Da Silva, D.T.C.; De Freitas Araújo Reis, M.Y.; De Lima Damasceno, B.P.G.; Pessoa, A.; Moraes Galvão, M.A.; Soares, L.A.L.; Veiga Júnior, V.F.D.; et al. Microemulsions Containing Copaifera Multijuga Hayne Oil-Resin: Challenges to Achieve an Efficient System for β-Caryophyllene Delivery. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 111, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weimer, P.; Kirsten, C.N.; De Araújo Lock, G.; Nunes, K.A.A.; Rossi, R.C.; Koester, L.S. Co-Delivery of Beta-Caryophyllene and Indomethacin in the Oily Core of Nanoemulsions Potentiates the Anti-Inflammatory Effect in LPS-Stimulated Macrophage Model. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2023, 191, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H.; Lee, I.Y.; Chun, Y.G.; Kim, B.-K. Formulation and Characterization of β-Caryophellene-Loaded Lipid Nanocarriers with Different Carrier Lipids for Food Processing Applications. LWT 2021, 149, 111805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranda, E.R.; Santos, J.S.; Toledo, A.L.M.M.; Barradas, T.N. Design and Characterization of Stable β-Caryophyllene-Loaded Nanoemulsions: A Rational HLB-Based Approach for Enhanced Volatility Control and Sustained Release. Beilstein Arch. 2025, 2025, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, P.S.; Souza, L.K.M.; Araújo, T.S.L.; Medeiros, J.V.R.; Nunes, S.C.C.; Carvalho, R.A.; Pais, A.C.C.; Veiga, F.J.B.; Nunes, L.C.C.; Figueiras, A. Methyl-β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex with β-Caryophyllene: Preparation, Characterization, and Improvement of Pharmacological Activities. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 9080–9094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Yang, G.; Tang, Y.; Cao, D.; Qi, T.; Qi, Y.; Fan, G. Physicochemical Characterization and Pharmacokinetics Evaluation of β-Caryophyllene/β-Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex. Int. J. Pharm. 2013, 450, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nurul Hidayati, E.S. pH-Sensitive Niosomal Nanoencapsulation of Beta- Caryophyllene and Its Novel Pathway in Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2025, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Hammadi, M.M.; Small-Howard, A.L.; Fernández-Arévalo, M.; Martín-Banderas, L. Development of Enhanced Drug Delivery Vehicles for Three Cannabis-Based Terpenes Using Poly(Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid) Based Nanoparticles. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 164, 113345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porto, D.S.; Fretes Argenta, D.; Ziech, C.C.; Balleste, M.P.; Dreyer, J.P.; Micke, G.A.; Campos, Â.M.; Caumo, K.S.; Caon, T. Amoebicidal Potential of β-Caryophyllene-Loaded Polymeric Nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 14447–14457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, C.; Lemos-Senna, E.; Da Silva Vieira, E.; Sampaio, T.B.; Mallmann, M.P.; Oliveira, M.S.; Bernardi, L.S.; Oliveira, P.R. β-Caryophyllene Cationic Nanoemulsion for Intranasal Delivery and Treatment of Epilepsy: Development and in Vivo Evaluation of Anticonvulsant Activity. J. Nanopart Res. 2023, 25, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Xu, F.; Wei, X.; Gu, J.; Qiao, P.; Zhu, X.; Yin, S.; Ouyang, D.; Dong, J.; Yao, J.; et al. Investigation of β-Caryophyllene as Terpene Penetration Enhancer: Role of Stratum Corneum Retention. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 183, 106401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakimov, I.D.; Kolmogorov, I.M.; Le-Deygen, I.M. Beta-Caryophyllene Induces Significant Changes in the Lipid Bilayer at Room and Physiological Temperatures: ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy Studies. Biophysica 2023, 3, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, T.B.; Coelho, D.S.; Maraschin, M. β-Caryophyllene Nanoparticles Design and Development: Controlled Drug Delivery of Cannabinoid CB2 Agonist as a Strategic Tool towards Neurodegeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 121, 111824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Długosz, A.; Błaszak, B.; Czarnecki, D.; Szulc, J. Mechanism of Action and Therapeutic Potential of Xanthohumol in Prevention of Selected Neurodegenerative Diseases. Molecules 2025, 30, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christaki, S.; Spanidi, E.; Panagiotidou, E.; Athanasopoulou, S.; Kyriakoudi, A.; Mourtzinos, I.; Gardikis, K. Cyclodextrins for the Delivery of Bioactive Compounds from Natural Sources: Medicinal, Food and Cosmetics Applications. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirchinger, M.; Bieler, L.; Tevini, J.; Vogl, M.; Haschke-Becher, E.; Felder, T.K.; Couillard-Després, S.; Riepl, H.; Urmann, C. Development and Characterization of the Neuroregenerative Xanthohumol C/Hydroxypropyl-β-Cyclodextrin Complex Suitable for Parenteral Administration. Planta Medica 2019, 85, 1233–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oledzka, E. Xanthohumol—A Miracle Molecule with Biological Activities: A Review of Biodegradable Polymeric Carriers and Naturally Derived Compounds for Its Delivery. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayyal, M.T.; El-Hazek, R.M.; El-Sabbagh, W.A.; Frank, J.; Behnam, D.; Abdel-Tawab, M. Micellar Solubilization Enhances the Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Xanthohumol. Phytomedicine 2020, 71, 153233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronka, S.; Kowalczyk, A.; Baczyńska, D.; Żołnierczyk, A.K. Pluronics-Based Drug Delivery Systems for Flavonoids Anticancer Treatment. Gels 2023, 9, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.A. The Manufacturing Techniques of Various Drug Loaded Biodegradable Poly(Lactide-Co-Glycolide) (PLGA) Devices. Biomaterials 2000, 21, 2475–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonseca, M.; Macedo, A.S.; Lima, S.A.C.; Reis, S.; Soares, R.; Fonte, P. Evaluation of the Antitumour and Antiproliferative Effect of Xanthohumol-Loaded PLGA Nanoparticles on Melanoma. Materials 2021, 14, 6421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Thapa, R.; Hariani, H.N.; Volyanyuk, M.; Ogle, S.D.; Orloff, K.A.; Ankireddy, S.; Lai, K.; Žiniauskaitė, A.; Stubbs, E.B.; et al. Poly(Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid) Nanoparticles Encapsulating the Prenylated Flavonoid, Xanthohumol, Protect Corneal Epithelial Cells from Dry Eye Disease-Associated Oxidative Stress. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanmantrao, M.; Chaterjee, S.; Kumar, R.; Vishwas, S.; Harish, V.; Porwal, O.; Alrouji, M.; Alomeir, O.; Alhajlah, S.; Gulati, M.; et al. Development of Guar Gum-Pectin-Based Colon Targeted Solid Self-Nanoemulsifying Drug Delivery System of Xanthohumol. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harish, V.; Tewari, D.; Mohd, S.; Govindaiah, P.; Babu, M.R.; Kumar, R.; Gulati, M.; Gowthamarajan, K.; Madhunapantula, S.V.; Chellappan, D.K.; et al. Quality by Design Based Formulation of Xanthohumol Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles with Improved Bioavailability and Anticancer Effect against PC-3 Cells. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buczek, A.; Rzepiela, K.; Stępniak, A.; Buczkowski, A.; Broda, M.A.; Pentak, D. Xanthohumol in Liposomal Form in the Presence of Cyclodextrins: Drug Delivery and Stability Analysis. Food Chem. 2025, 492, 145453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, W.; Sharma, C.P. Inorganic Nanoparticles for Targeted Drug Delivery. In Biointegration of Medical Implant Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 333–373. ISBN 978-0-08-102680-9. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, T.; Wang, X.E.; Dang, T.; Pruner, J.; Li, Y. Preparation and Characterization of Xanthohumol-Incorporated Sub-5 Ultrafine Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Investigation of Their Effects on Multiple Myeloma Cell Growth (Abstract ID: 190025). J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2025, 392, 103487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauda, V.; Canavese, G. Mesoporous Materials for Drug Delivery and Theranostics. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krajnović, T.; Pantelić, N.Đ.; Wolf, K.; Eichhorn, T.; Maksimović-Ivanić, D.; Mijatović, S.; Wessjohann, L.A.; Kaluđerović, G.N. Anticancer Potential of Xanthohumol and Isoxanthohumol Loaded into SBA-15 Mesoporous Silica Particles against B16F10 Melanoma Cells. Materials 2022, 15, 5028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.-H.; Galaj, E.; Bi, G.-H.; He, Y.; Hempel, B.; Wang, Y.-L.; Gardner, E.L.; Xi, Z.-X. β-Caryophyllene, an FDA-Approved Food Additive, Inhibits Methamphetamine-Taking and Methamphetamine-Seeking Behaviors Possibly via CB2 and Non-CB2 Receptor Mechanisms. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 722476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clinicaltrials.Gov. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ (accessed on 8 January 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).