Abstract

The identification of new cancer-associated genes/proteins, the characterization of their expression variation, the interactomics-based assessment of differentially expressed genes/proteins (DEGs/DEPs), and understanding the tumorigenic pathways and biological processes involved in BC genesis and progression are necessary and possible by the rapid and recent advances in bioinformatics and molecular profiling strategies. Taking into account the opinion of other authors, as well as based on our own team’s in vitro studies, we suggest that the human jumping translocation breakpoint (hJTB) protein might be considered as a tumor biomarker for BC and should be studied as a target for BC therapy. In this study, we identify DEPs, carcinogenic pathways, and biological processes associated with JTB silencing, using 2D-PAGE coupled with nano-liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (nLC-MS/MS) proteomics applied to a MCF7 breast cancer cell line, for complementing and completing our previous results based on SDS-PAGE, as well as in-solution proteomics of MCF7 cells transfected for JTB downregulation. The functions of significant DEPs are analyzed using GSEA and KEGG analyses. Almost all DEPs exert pro-tumorigenic effects in the JTBlow condition, sustaining the tumor suppressive function of JTB. Thus, the identified DEPs are involved in several signaling and metabolic pathways that play pro-tumorigenic roles: EMT, ERK/MAPK, PI3K/AKT, Wnt/β-catenin, mTOR, C-MYC, NF-κB, IFN-γ and IFN-α responses, UPR, and glycolysis/gluconeogenesis. These pathways sustain cancer cell growth, adhesion, survival, proliferation, invasion, metastasis, resistance to apoptosis, tight junctions and cytoskeleton reorganization, the maintenance of stemness, metabolic reprogramming, survival in a hostile environment, and sustain a poor clinical outcome. In conclusion, JTB silencing might increase the neoplastic phenotype and behavior of the MCF7 BC cell line. The data is available via ProteomeXchange with the identifier PXD046265.

1. Introduction

Discovering and validating novel biomarkers, especially for early cancer diagnosis, as well as molecular targets for advanced therapies in breast cancer (BC), necessitate the handling of accurate gene expression datasets [1]. The identification of new cancer-associated regulatory genes/proteins, the characterization of their expression variations, the interactomics-based assessment of differentially expressed genes/proteins (DEGs/DEPs), and understanding the tumorigenic pathways and biological processes involved in BC genesis and progression are possible by the rapid and recent advances in bioinformatics and molecular profiling strategies or analytical techniques, especially based on high-throughput sequencing and mass spectrometry (MS) developments.

In 1999, Hatakeyama et al. reported the human jumping translocation breakpoint (hJTB) as a novel transmembrane protein gene at locus 1q21, a region called the epidermal differentiation complex (EDC), involved in unbalanced jumping translocation, suggesting the JTB’s association with tumor progression [2]. Moreover, Tyszkiewicz et al. (2014) showed that the EDC molecules were involved in important mechanisms in adenocarcinomas [3], while other authors showed that chromosomal translocations were a hallmark for cancer [4], jumping translocations (JTs) being usually identified in tumors [5]. In 2007, Kanome et al. stated that JTB is a transmembrane protein with an unknown function; however, the authors observed that JTB expression was suppressed in many tumor types, emphasizing its role in the malignant transformation of cells [6]. Platica et al. (2000) showed that hJTB cDNA had a 100% homology with prostate androgen-regulated (PAR) gene isolated from an androgen-resistant prostate cancer cell line [7]. The same authors reported that PAR/JTB expression was upregulated in all studied prostatic carcinoma cell lines compared with normal prostatic tissue, in androgen-resistant prostate cancer cell lines in comparison with androgen-sensitive prostate cells, in MCF7 and T47D BC cell lines, as well as in all the primary breast tumors studied compared to their normal counterparts. Moreover, Platica et al. (2011) observed that the downregulation of PAR levels in DU145 cells resulted in defects in centrosome segregation, failed cytokinesis and chromosome alignment, and an increased number of apoptotic cells, polyploidy, and aberrant mitosis that could lead to genomic instability and tumorigenesis [8]. These authors suggested that the PAR overexpression in several human cancers might be a putative target for therapy. Pan et al. (2009) showed that JTB may play a critical role in liver carcinogenesis [9]. Functionally, JTB has been reported as a regulator of mitochondrial function, cell growth, cell death and apoptosis, as well as being a protein involved in cytokinesis/cell cycle activities [6,8].

MCF7 is a middle aggressive and non-invasive BC cell line that has been used for membrane protein enrichment proteomic analyses [10] as well as for the identification of dysregulated signaling pathways and cellular targets of different compounds with anti-tumorigenic activity [11]. We also show that the upregulated expression of DEPs in the JTBlow condition, investigated by SDS-PAGE followed by nLC-MS/MS proteomics in a transfected MCF7 BC cell line, promotes cancer cell viability, motility, proliferation, invasion, the ability to survive in hostile environments, metabolic reprogramming, and the escaping of tumor cells from host immune control, leading to a more invasive phenotype for MCF7 cells. Several downregulated DEPs in a low-JTB condition also promote the invasive phenotype of MCF7 cells, sustaining cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and tumorigenesis [12]. Several DEPs identified during JTB silencing by in-solution digestion followed by nLC-MS/MS that were complementary to the initial in-gel based ones [12], especially upregulated proteins, are known to emphasize pro-tumorigenic activities in a downregulated state [13].

Taking into account the previously cited references [2,6,7,8,9], as well as based on our own team’s studies [12,13,14,15], we suggest that the JTB protein might be a tumor biomarker for BC and should be studied as a target for cancer therapy. In this study, we identify the DEPs and carcinogenic pathways associated with JTB silencing, using 2D-PAGE coupled with nano-liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (nLC-MS/MS) proteomics applied to the MCF7 breast cancer cell line, for complementing and completing our previous results based on SDS-PAGE [12], as well as the in-solution proteomics of MCF7 cells transfected for JTB downregulation [13]. We concluded that almost all DEPs exert pro-tumorigenic effects in JTBlow conditions, sustaining the tumor suppressive function of JTB. The function of DEPs has been analyzed using GSEA and KEGG, while STRING analysis has been applied to construct the protein-protein interaction network of the JTBlow-related proteins that exert a PT activity. The identified DEPs are involved in several signaling and metabolic pathways and biological processes that exert pro-tumorigenic (PT) roles: EMT, tight junction, cytoskeleton organization, ERK/MAPK, PI3K/AKT, Wnt/β-catenin, mTOR, c-MYC, NF-κB, IFN-γ and IFN-α response, UPR, and metabolic reprogramming.

2. Results and Discussion

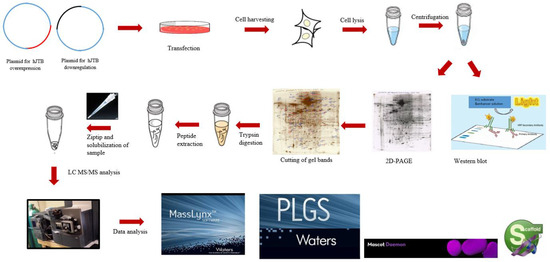

Using 2D-PAGE coupled with nLC-MS/MS proteomics, the present study identified 45 significantly dysregulated proteins, 37 upregulated and 8 downregulated, in the MCF7 BC cell line transfected for JTB silencing. The workflow for cellular proteomics followed by 2D-polyacrylamide gel (2D-PAGE) coupled with nLC-MS/MS analysis of the cell lysates is presented in the Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The workflow for cellular proteomics followed by 2D-polyacrylamide gel (2D-PAGE) coupled with nLC-MS/MS analysis of the cell lysates.

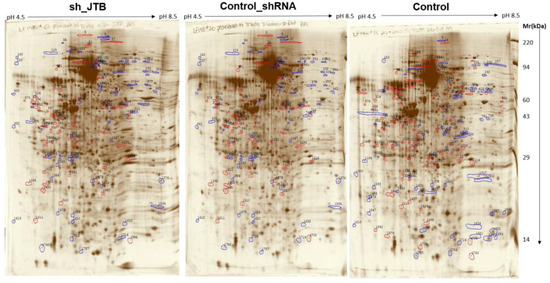

There were 131 dysregulated spots in the control_shRNA vs. sh_JTB and 153 differences in the control vs. sh_JTB (Figure 2 and Figure 3). A total of 284 spots were selected for Nano LC- MS/MS analysis, as previously described [16].

Figure 2.

Images of sh_JTB (left), control_shRNA (middle), control (right) silver stained 2D polyacrylamide gels. Polypeptide spots increased in each compared gels (top vs. bottom) are shown in blue, while spots decreased are outlined in red.

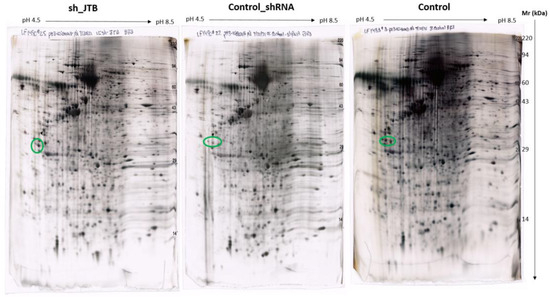

Figure 3.

Images of sh_JTB (left), control_shRNA (middle), control (right) silver stained 2D polyacrylamide gels. The circles on each 2D-polyacrylamide gel shows the location of Isoelectric focusing internal standard Tropomyosin of Mw: 33000 and a pI of 5.2.

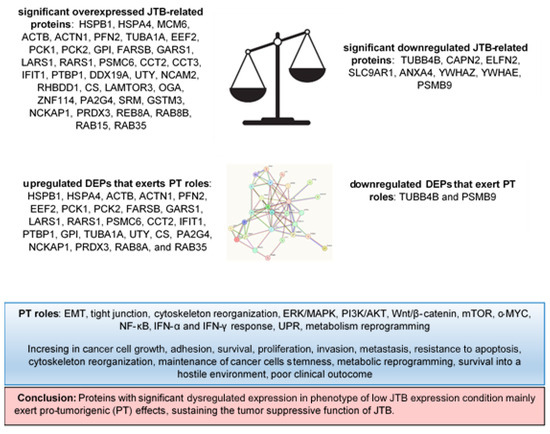

We only analyzed proteins that have a protein score of above 40 and p-value < 0.05. HSPB1, HSPA4, MCM6, ACTB, ACTN1, PFN2, TUBA1A, EEF2, PCK1, PCK2, GPI, FARSB, GARS1, LARS1, RARS1, PSMC6, CCT2, CCT3, IFIT1, PTBP1, DDX19A, UTY, NCAM2, RHBDD1, CS, LAMTOR3, OGA, ZNF114, PA2G4, SRM, GSTM3, NCKAP1, PRDX3, REB8A, RAB8B, RAB15 and RAB35 are overexpressed, while TUBB4B, CAPN2, ELFN2, SLC9AR1, ANXA4, YWHAZ, YWHAE, and PSMB9 proteins were found to be significantly downregulated. GSEA analysis was performed for the downregulated JTB condition using the H (hallmark gene sets) collection in MSigDB. Analysis of the H collection revealed four upregulated pathways, including proteins important for interferon alpha response (IFN-α), interferon gamma response (IFN-γ), Myc targets V1, and unfolded protein response (UPR). Two downregulated pathways comprised proteins involved in estrogen response late and estrogen response early pathways (Table 1). We also performed Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis and here we emphasized the enriched biological processes in pro-tumorigenic proteins identified in downregulated JTB conditions using GeneCodis website (https://genecodis.genyo.es/, accessed on 22 October 2023). There were 25 upregulated and two downregulated proteins with pro-tumorigenic (PT) potential, which were then submitted for protein-protein interaction (PPI) network construction with Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (STRING) database (https://string-db.org/, accessed on 22 October 2023), to analyze the specific interaction network associated with the JTBlow condition in the transfected MCF7 BC cell line. A total of 27 nodes and 69 edges were mapped in the PPI network, with an average node degree of 5.11, an average local clustering coefficient of 0.632, and a PPI enrichment p-value 6.44 × 10−12.

Table 1.

Significant up and downregulated pathways in the downregulated JTB condition in the MCF7 BC cell line, according to GSEA with FDR < 25%.

To emphasize the role of the JTB-interactome, we analysed the pro-tumorigenic (PT) and anti-tumorigenic (AT) function of these proteins, as well as the neoplastic dysregulated pathways and biological processes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Deregulated DEPs, neoplastic roles, and biological processes expressed in response to JTB downregulation in MCF7 BC cell line.

Analyzing the data from Table 2, we observed that 38 DEPs emphasize a pro-tumorigenic (PT) role and 5 DEPs are known to have anti-tumorigenic (AT) activity in the MCF7 BC cell line transfected for JTB downregulation.

2.1. JTB Silencing Is Associated with Neoplastic Abilities of MCF7 Transfected Cells

The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process facilitates the local invasion in cancer. We identified a plethora of upregulated and downregulated DEPs directly or indirectly involved in EMT process: HSPB1, HSPA4, MCM6, ACTN1, PFN2, EEF2, IFIT1, DDX19A, GPI, TUBA1A, CS, PA2G4, GSTM3, NCKAP1, and TUBB4B (Table 2). According to previously published data, HSPB1 and HSPA4 are members of the HSP family that promote EMT in association with the increased invasiveness of cancer cells [13]. Also, the EMT process is subjected to metabolic regulation, while the metabolic pathways adapt to cellular changes during the EMT. The mammalian or mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway becomes aberrant in various types of cancer. The hyperactivation of mTOR signaling pathway promotes cell proliferation and metabolic reprogramming that initiates tumorigenesis and progression [129]. HSPA4, PCK1, PCK2, LARS1, PSMC6, LAMTOR3, SRM, and SLC9AR1 proteins are involved in mTOR pathway activation in MCF7 cells transfected for JTB silencing. The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway regulates proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis and stress responses, while the overexpression of extracellular signal-regulated kinases ERK1 and ERK2 is critical in cancer development and progression [130]. We identified MCM6, PCK1, LAMTOR3, GSM3, and REB8A as pro-tumorigenic proteins involved in ERK/MAPK signaling pathways in the JTBlow condition. Also, the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K/AKT) pathway is one of the most hyper-activated intracellular pathways in many human cancers, contributing to carcinogenesis, cell proliferation, invasion and metastasis [131]. HSPA4, CCT3, PTBP1, and RAB35 are pro-tumorigenic proteins involved in PI3K/AKT pathway. The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway facilitates cancer stem cell renewal, cell proliferation and differentiation, being involved in carcinogenesis and therapy response [132]. Several DEPs, such as POTEF/ACTB, PSMC6, CCT3, IFIT1, and RAB8B are dysregulated proteins involved in Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which emphasize pro-tumorigenic activities. NF-κB is an important signaling pathway involved in cancer development and progression, which controls the expression of several target genes and mediates cancer cell proliferation, survival and angiogenesis [133]. Thus, HSPB1/HSP27 and POTEF have been identified as proto-oncogenic proteins involved in this pathway. The unfolded protein response (UPR) is known as a pro-survival mechanism involved in progression of several cancers, such as BC, prostate cancer, and glioblastoma multiforme [134]. Here, JTB silencing was associated with UPR-related proteins, such as EEF2 and IFIT1.

The vesicle transport regulators play key roles in tumor progression, including uncontrolled cell growth, invasion and metastasis [104]. Ras-related proteins, small GTP-binding proteins of the Rab family, are dysregulated in malignant cells, affecting intracellular and membrane traffic, as well as proliferation and metastasis, reducing the survival rate of patients [101]. Ras-related protein Rab-8A (RAB8A) and Ras-related protein Rab-8B (RAB8B) were significantly upregulated in this experiment. Gene ontology enrichment analysis identified the following biological processes enriched in these upregulated proteins: vesicle docking involved in exocytosis, regulation of exocytosis, regulation of protein transport, protein secretion, protein import into peroxisome membrane, Golgi vesicle fusion to target membrane, protein localization to plasma membrane and cell junction organization. RABA8 was reported as overexpressed in BC tissues [101], while RAB8B was upregulated in TC [102]. The RAB8A silencing inhibits the proliferation, migration and invasion of BC cells through suppression of AKT and ERK1/2 phosphorylation [101]. RAB8B is required for the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [103], while its overexpression promotes the activity and internalization by caveolar endocytosis of LRP6, a member of the low-density lipoprotein receptor superfamily of cell-surface receptors, which is involved in cell proliferation, migration, and metastasis [135]. RAB15 is involved in trafficking cargo through the apical recycling endosome (ARE) to mediate transcytosis [104]. It is overexpressed in liver cancer cells [105] and is associated with the susceptibility of cells to DNA damage-induced cell death [105]. RAB35 is an oncogenic protein that enhances the invasion and metastasis of BC cells [107].

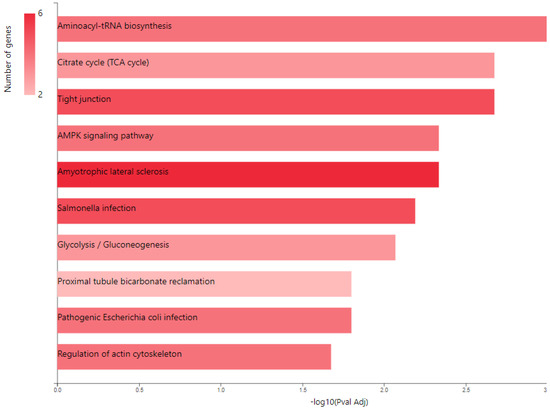

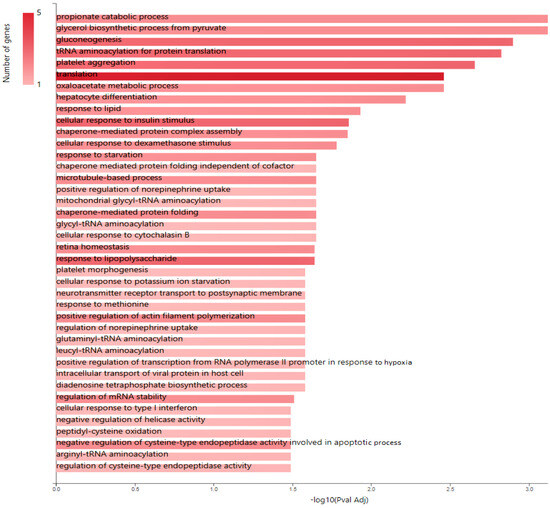

KEGG pathway analysis (Figure 4) also emphasized the following enriched pathways in the MCF7 BC cell line transfected for JTB downregulation: KEGG_Tight junction and KEGG_Regulation of actin cytoskeleton. De Abreu Pereira et al. (2022) showed that highly expressed proteins and biological processes in HCC-1954 (HER2+), a very invasive and metastatic BC cell line, are classified as tight junctions and cytoskeleton proteins, as compared to an MCF7 BC cell line that emphasized proteins related to proteasome and histones in correlation with the higher rate of mutation in MCF7 BC cells [10].

Figure 4.

KEGG pathway analysis of pro-tumorigenic (PT) proteins in downregulated JTB condition; B. Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of proteins in MCF7 BC cell line transfected for JTB downregulation: biological processes (BP) enriched in PT proteins. The analysis was performed using GeneCodis website (https://genecodis.genyo.es/, accessed on 22 October 2023).

2.2. Glucose Metabolism Reprogramming in JTB Downregulated Condition

Multiple cancer cell metabolic pathways are reprogrammed and adapted to sustain cell proliferation, tumor growth, and metastasis in tumor progression, especially under a nutrient deprivation condition. KEGG pathway analysis (Figure 4) emphasized several metabolic enriched pathways in the MCF7 BC cell line transfected for JTB downregulation: TCA cycle (KEGG_Citrate cycle/TCA cycle) and Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis (KEGG_Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis), while GO analysis showed as upregulated: gluconeogenesis (GO_BP Gluconeogenesis) and pyruvate metabolism (GO_BP_Glycerol biosynthetic process from pyruvate). The highlighted dysregulation of propionate metabolism (GO_BP Propionate catabolic process) is also known to contribute to a pro-aggressive state in BC cells, increasing cancer cell metastatic ability [136]. Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) carboxykinases (PCK1/PEPCK-C, cytosolic isoform, and PCK2/PEPCK-M, mitochondrial isoform) have been shown to be multifunctional enzymes, critical for the growth of certain cancers [137], sustaining cell cycle progression and cell proliferation [39,40]. Thus, in the absence of glucose, cancer cells may synthesize essential metabolites using abbreviated forms of gluconeogenesis, as a reverse phase of glycolysis, especially by PCK1 and PCK2 expression [137], both well known for their key roles in gluconeogenesis and regulation of TCA cycle flux [39]. PCK1 has been reported as a tumor-suppressor in cancers arising from gluconeogenic tissues/organs, such as liver and kidney, while it acts as a tumor promoter in many human cancers arising in non-gluconeogenic tissues [138]. Consequently, PCK1 was reported as an overexpressed oncogene in colon, thyroid, breast, lung, urinary tract, and melanoma cancers [36], while it was found as a downregulated tumor suppressor in tumors arising in gluconeogenic tissues of liver and kidney, such as in HCC [36], and ccRCC [37]. Here we showed that MCF7 cells transfected for JTB downregulation markedly upregulated cytosolic PCK1, which was described as a molecular hub that regulates glycolysis, TCA cycle and gluconeogenesis to increase glycogenesis via gluconeogenesis [139]. PCK1, as a key rate-limiting enzyme in gluconeogenesis, catalyzes the conversion of oxaloacetate (OAA) to PEP (GO_BP oxaloacetate metabolic process) [138] and links the TCA and glycolysis/gluconeogenesis [40]. The expression of PGK1 leads to the biosynthesis of glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) that can be used by different pathways, including conversion to glucose, glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) or glycogenesis [139]. Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase (GPI) that interconverts G6P and fructose-6-phosphate (F6P) is also overexpressed in the downregulated JTB condition (GO_BP Gluconeogenesis). Cytoplasmic GPI is a glycolytic-related enzyme secreted in the extracellular matrix (ECM) of cancer cells, where it is called an autocrine motility factor (AMF) [62], and functions as a cytokine or growth factor [63]. GPI is overexpressed in BC [63], LUAD/NSCLC, glioblastoma, ccRCC [64], and GC [62]. This glycolytic enzyme is involved in cell cycle, cell proliferation, correlates with immune infiltration, cell migration and invasion [64], while silencing suppressed proliferation, migration, invasion, glycolysis, and induced apoptosis (GO_BP Negative regulation of cysteine-type endopeptidase activity involved in apoptotic process) [62]. PCK1 also enhances the PPP, which produces ribose-5-phosphate for nucleotide synthesis and NADPH for biosynthetic pathways [138]. Abundant NADPH ensures high levels of reduced glutathione (GSH) [139], known for its important intracellular antioxidant role, which acts as a regulator of cellular redox state as well as a controller of cell differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, ferroptosis and immune function [140].

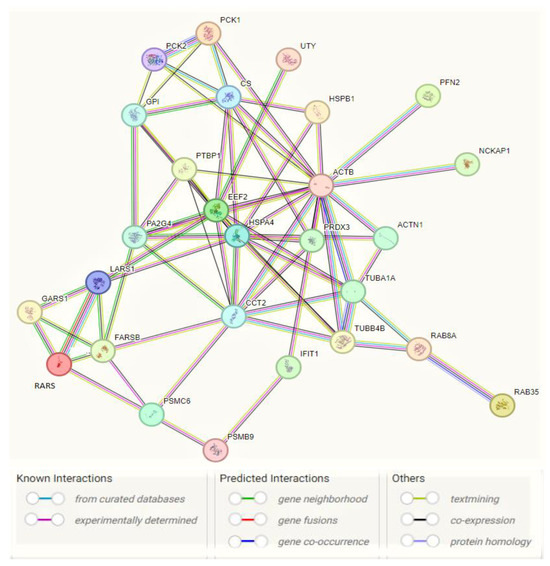

Cancer cells utilize glutamine metabolism for energy generation as well as to synthesize molecules that are essential for cancer growth and progression [141], such as nucleotides and fatty acids, which regulate redox balance in cancer cells [142]. PEPCKs increase the synthesis of ribose from non-carbohydrate sources, such as glutamine [39] as well as the serine and other amino acid synthesis [143]. Also, PCK1 helps regulate triglyceride/fatty acid cycle (GO_BP Regulation of lipid biosynthetic process) and development of insulin resistance (GO_BP Cellular response to insulin stimulus), being involved in glyceroneogenesis (GO_BP Glycerol biosynthetic pathway from pyruvate) and re-esterification of free fatty acids [144]. PEPCK-M is reported as a key mediator for the synthesis of glycerol phosphate from non-carbohydrate precursors, being important to maintain level of glycerophospholipids as major constituents of bio-membranes [145]. The effects of PEPCK on glucose metabolism and cancer cell proliferation are partially mediated by activation of mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTORC1) [39], which is regulated by glucose, growth factors and amino acids and is coupled to the insulin/IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor 1) signaling pathway [146]. Thus, the mitochondrial phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK-M/PCK2), known to enhance cell proliferation and response to stress or nutrient/glucose restriction/deprivation in cancer cells (GO_BP Response to starvation) compared to PCK1 that functions primarily in gluconeogenesis, promotes tumor growth in ER+ BC through regulation of mTOR pathway (GO_BP Positive regulation of mTOR signaling) [40]. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is an ”energy sensor”/metabolic regulator involved in lipogenesis, glycolysis, TCA cycle, cell cycle progression, and mitochondrial dynamics [147]. PCK1 dysregulation may promote cell proliferation via inactivation of AMPK (KEGG_AMPK signaling pathway), known as a tumor suppressor [36] but was recently reconsidered as a putative oncogene [148]. PCK1-directed glycogen metabolic program regulates differentiation and maintenance of CD8+ T cells that are essential for protective immunity against cancer [139] (GO_BP Positive regulation of memory T cell differentiation). PEPCK is known to be activated in response to acidosis. The acid-induced PEPCK provides glucose for acid-base homeostasis (GO_BP Positive regulation of transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter in response to acidic pH) [149]. In conclusion, PCK enzymes are involved in gluconeogenesis, glyceroneogenesis, serine biosynthesis, and amino acid metabolism, targeting the increase of glucose level that contributes to the development and progression of many types of cancer arising in non-gluconeogenic tissues/organs [150]. 25 upregulated DEPs with PT activity (HSPB1, HSPA4, ACTB, ACTN1, PFN2, EEF2, PCK1, PCK2, FARSB, GARS1, LARS1, RARS1, PSMC6, CCT2, IFIT1, PTBP1, GPI, TUBA1A, UTY, CS, PA2G4, NCKAP1, PRDX3, RAB8A, and RAB35) and two downregulated DEPs (TUBB4B and PSMB9) were submitted for PPI network construction with STRING database (https://string-db.org/, accessed on 22 October 2023), to highlight the specific interaction network associated with the JTBlow condition in transfected MCF7 BC cell line (Figure 5). This enrichment indicates that these proteins with PT potential are biological connected, as a group.

Figure 5.

Interaction network of pro-tumorigenic (PT) proteins in MCF7 BC cell line transfected for JTB silencing, by means of STRING on-line database (https://string-db.org/, accessed on 22 October 2023). A total of 27 nodes and 69 edges were mapped in the PPI network with a PPI enrichment p-value of 6.44 × 10−12.

The main results of this experiment are synthetized in the Figure 6.

Figure 6.

DEPs and their pro-tumorigenic (PT) activity in MCF7 BC cell line transfected for JTB silencing.

3. Materials and Methods

MCF7 cell culture, the transfection of hJTB plasmids and the collection of cell lysates was described previously [12] and briefly described below.

3.1. Cell Culture

MCF7 cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (HTB-22 ATCC) and grown in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS, 0.2% Gentamicin, 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin and 0.2% Amphotericin (growth media) at 37 °C. The cells were grown until they reached 70–80% confluency and were transiently transfected with JTB shRNA plasmid for downregulation.

3.2. Plasmids for Downregulation

Four plasmids were custom made by Creative Biogene, Shirley, NY, USA. Three shRNA plasmids containing GCTTTGATGGAACAACGCTTA sequence, with forward sequencing primer of 5′-CCGACAACCACTACCTGA-3′ and reverse primer of 5’-CTCTACAAATGTGGTATGGC-3′, GCAAATCGAGTCCATATAGCT sequence, with forward primer 5′-CCGACAACCACTACCTGA-3′ and reverse primer of 5′-CTCTACAAATGTGGTATGGC-3′, and GTGCAGGAAGAGAAGCTGTCA sequence with 5′-CCGACAACCACTACCTGA-3′ and reverse primer of 5′-CTCTACAAATGTGGTATGGC-3’, all targeting the hJTB mRNA respectively. The fourth plasmid was a control plasmid with a scramble sequence GCTTCGCGCCGTAGTCTTA with forward primer 5′-CCGACAACCACTACCTGA-3′ and reverse primer of 5′-CTCTACAAATGTGGTATGGC-3′. These plasmids were further customized to have an eGFP tag with Puromicin antibiotic resistance gene.

3.3. Transfection into MCF7 Cells

As stated in [12], Lipofectamine™ 3000/DNA and DNA/Plasmid (10 µg/µL) complexes were prepared in Opti-MEM Reduced Serum Media (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) for each condition and added directly to the cells in culture medium. Cells were allowed to grow for 48–72 h after which they were collected. 70% transient transfection efficiency was confirmed by visualizing the green fluorescence emitted by the eGFP using a confocal microscope (Figure S1).

3.4. Western Blot Analysis

Cell lysates from both the control and downregulated JTB condition were collected using a lysis buffer. The lysates were then incubated on ice for 30 min and centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 20 min. The protein samples were quantified using Bradford Assay. Lysates containing 20 µg of proteins were run in a 14% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The blots were incubated with blocking buffer containing 5% milk and 0.1% tween-20 overnight at 4 °C with shaking. Primary antibody (JTB Polyclonal Antibody—PA5-52307, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) was added and incubated for 1 h with constant shaking. Secondary antibody (mouse anti-rabbit IgG-HRP sc-2357, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas TX, USA) was added and incubated for 1 h with constant shaking. After each incubation, the blots were washed thrice with TBS-T (1X TBS buffer, containing 0.05% tween-20) for 10 min each with constant shaking. Finally, the enhanced chemi-luminescent substrate (Pierce™ ECL Western Blotting Substrate—32106, ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) was added and the blot was analyzed using a CCD Imager. For normalization, mouse GAPDH monoclonal antibody (51332, cell-signaling technology, Danvers, MA, USA) was added and incubated for 1 h, followed by the addition of goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP (sc-2005, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and the addition of ECL substrate. Image J software was used for the detection and comparison of the intensity of the bands (Figure S2).

3.5. 2D-PAGE & Proteomic Analysis

We used three biological replicates for the downregulated JTB condition. Two controls were used for the comparison: control (n = 3), control_shRNA (n = 3) and sh_JTB (n = 3). These conditions were analyzed in 2D-PAGE by Kendrick Labs, Inc. (Madison, WI, USA) and nanoLC-MS/MS as previously described [13]. The computer comparison was done for the average of three samples (3 vs. 3)—control_shRNA vs. sh_JTB (n = 3) and Control vs. sh_JTB (n = 3). The dysregulated spots were selected based on the criteria of having a fold increase or decrease of ≥1.7 and p value of ≤0.05. The data processing was done using PLGS software (v. 2.4) to convert them to pkl files and Mascot Daemon software (v. 2.5.1) was used to identify the dysregulated proteins. Finally, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) analysis was done to identify the identify the dysregulated pathways as previously described [13].

3.6. Data Sharing

Mascot data will be provided upon request, according to Clarkson University Material Transfer Agreement. The mass spectrometry data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD046265.4.

4. Conclusions

The jumping translocation breakpoint (JTB) protein has been reported as a regulator of mitochondrial function, cell growth, cell death and apoptosis, as well as a protein involved in cytokinesis/cell cycle. Some authors detected JTB as an overexpressed gene/protein in several malignant tissues and cancer cell lines, including liver cancer, prostate cancer, and BC, showing that this gene may suffer from unbalanced jumping translocation that leads to aberrant products, highlighting that the JTB downregulation/silencing increases cancer cell motility, anti-apoptosis, and promotes genomic instability and tumorigenesis. We also showed that the upregulated expression of DEPs in the JTBlow condition, investigated by SDS-PAGE followed by nLC-MS/MS proteomics in transfected MCF7 BC cell line, may promote cancer cell viability, motility, proliferation, invasion, ability to survive into hostile environment, metabolic reprogramming, escaping of tumor cells from host immune control, leading to a more invasive phenotype for MCF7 cells. Several downregulated DEPs in the JTBlow condition also promoted the invasive phenotype of MCF7 cells, sustaining cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and tumorigenesis. A plethora of DEPs identified during JTB silencing by in-solution digestion followed by nLC-MS/MS have been complementary and completed the list of DEPs identified by SDS-PAGE proteomics [12]. In this last case especially, upregulated proteins emphasized pro-tumorigenic activities in downregulated JTB state [13].

Using 2D-PAGE coupled with nLC-MS/MS proteomics, the present study identified 45 significantly dysregulated proteins, of which 37 were upregulated and 8 downregulated, in MCF7 BC cell line transfected for downregulated JTB condition. HSPB1, HSPA4, MCM6, ACTB, ACTN1, PFN2, TUBA1A, EEF2, PCK1, PCK2, GPI, FARSB, GARS1, LARS1, RARS1, PSMC6, CCT2, CCT3, IFIT1, PTBP1, DDX19A, UTY, NCAM2, RHBDD1, CS, LAMTOR3, OGA, ZNF114, PA2G4, SRM, GSTM3, NCKAP1, PRDX3, REB8A, RAB8B, RAB15 and RAB35 have been overexpressed, while TUBB4B, CAPN2, ELFN2, SLC9AR1, ANXA4, YWHAZ, YWHAE, and PSMB9 proteins were found to be significantly downregulated. GSEA revealed four upregulated pathways, including proteins important for interferon alpha (IFN-α) response, interferon gamma (IFN-γ) response, Myc targets V1, and unfolded protein response (UPR). Two downregulated pathways comprised proteins involved in estrogen response late and estrogen response early pathways. Almost all DEPs identified in this experiment exert pro-tumorigenic effects in the JTBlow condition, sustaining the tumor suppressive function of JTB. Thus, the identified DEPs are involved in several signaling and metabolic pathways that exert pro-tumorigenic roles: EMT, ERK/MAPK, PI3K/AKT, Wnt/β-catenin, mTOR, C-MYC, NF-κB, IFN-γ and IFN-α response, UPR, and glycolysis/gluconeogenesis. These pathways sustain cancer cell growth, adhesion, survival, proliferation, invasion, metastasis, resistance to apoptosis, cytoskeleton reorganization, maintenance of stemness, metabolic reprogramming, survival in a hostile environment, and a poor clinical outcome. In conclusion, JTB silencing might increase the neoplastic phenotype and behavior of MCF7 BC cell line.

Analysis of upregulation of JTB was systematic, complementary and comprehensive: in-solution digestion, 1-D-PAGE and 2D-PAGE, followed by proteomics. Analysis of JTB silencing was also systematic, complementary and comprehensive: in-solution digestion and 1D-PAGE, and now 2D-PAGE, followed by proteomics. Additional, complementary or better methods can also be used, at the sample level, or at the instrumentation level. The current in-solution and gel-based analysis can be complemented, among others, by peptidomics analysis, phsosphoproteomics analysis, or analysis of stable and transient protein-protein interactions. At the instrumentation level, 2D-UPLC could be one option, and newer, more performant mass spectrometers could also be used.

Overall, taking into account the opinion of other authors, as well as based on our own team’s in vitro studies, we suggest that JTB protein might be considered as a tumor biomarker for BC and should be studied as a target for BC therapy.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules28227501/s1, Figure S1. Confocal microscope images showing conformation of transient transfection for control (A) and JTB downregulated condition (B). Left panel is the Bright Field (BF) mode, middle panel is the GFP mode and the right panel is a merge between BF and GFP modes. Figure S2. Downregulation confirmation of hJTB compared to control samples with (A) showing the downregulation of JTB protein at ~45 kDa in MCF7 cells treated with sh plasmids compared to control using commercially available full length hJTB antibody from Invitrogen; (B) shows GAPDH used as the loading control at 37 kDa.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.J. and C.C.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.J., A.-N.N., D.W., I.S., B.A.P., T.J. and C.C.D.; writing—review and editing, M.J., A.-N.N., D.W., I.S., B.A.P., T.J. and C.C.D.; funding acquisition, C.C.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This publication was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R15CA260126. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The mass spectrometry data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD046265.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the members of the Biochemistry & Proteomics Laboratories for the pleasant working environment. CCD would like to thank the Fulbright Commission USA-Romania (CCD host, Brindusa Alina Petre guest) and to the Erasmus+ Exchange Program between Clarkson University and Al. I. Cuza Iasi, Romania (Tess Cassler at Clarkson and Alina Malanciuc & Gina Marinescu at Al. I. Cuza Iasi).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ali, R.; Sultan, A.; Ishrat, R.; Haque, S.; Khan, N.J.; Prieto, M.A. Identification of New Key Genes and Their Association with Breast Cancer Occurrence and Poor Survival Using In Silico and In Vitro Methods. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatakeyama, S.; Osawa, M.; Omine, M.; Ishikawa, F. JTB: A novel membrane protein gene at 1q21 rearranged in a jumping translocation. Oncogene 1999, 18, 2085–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyszkiewicz, T.; Jarzab, M.; Szymczyk, C.; Kowal, M.; Krajewska, J.; Jaworska, M.; Fraczek, M.; Krajewska, A.; Hadas, E.; Swierniak, M.; et al. Epidermal differentiation complex (locus 1q21) gene expression in head and neck cancer and normal mucosa. Folia Histochem. et Cytobiol. 2014, 52, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogenbirk, M.A.; Heideman, M.R.; de Rink, I.; Velds, A.; Kerkhoven, R.M.; Wessels, L.F.A.; Jacobs, H. Defining chromosomal translocation risks in cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E3649–E3656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stankiewicz, P.; Cheung, S.; Shaw, C.; Saleki, R.; Szigeti, K.; Lupski, J. The donor chromosome breakpoint for a jumping translocation is associated with large low-copy repeats in 21q21.3. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2003, 101, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanome, T.; Itoh, N.; Ishikawa, F.; Mori, K.; Kim-Kaneyama, J.R.; Nose, K.; Shibanuma, M. Characterization of Jumping translocation breakpoint (JTB) gene product isolated as a TGF-β1-inducible clone involved in regulation of mitochondrial function, cell growth and cell death. Oncogene 2007, 26, 5991–6001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platica, O.; Chen, S.; Ivan, E.; Lopingco, M.C.; Holland, J.F.; Platica, M. PAR, a novel androgen regulated gene, ubiquitously expressed in normal and malignant cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2000, 16, 1055–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platica, M.; Ionescu, A.; Ivan, E.; Holland, J.F.; Mandeli, J.; Platica, O. PAR, a protein involved in the cell cycle, is functionally related to chromosomal passenger proteins. Int. J. Oncol. 2011, 38, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.-S.; Cai, J.-Y.; Xie, C.-X.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, Z.-P.; Dong, J.; Xu, H.-Z.; Shi, H.-X.; Ren, J.-L. Interacting with HBsAg compromises resistance of Jumping translocation breakpoint protein to ultraviolet radiation-induced apoptosis in 293FT cells. Cancer Lett. 2009, 285, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Abreu Pereira, D.; Sandim, V.; Fernandes, T.F.; Almeida, V.H.; Rocha, M.R.; do Amaral, R.J.; Rossi, M.I.D.; Kalume, D.E.; Zingali, R.B. Proteomic Analysis of HCC-1954 and MCF-7 Cell Lines Highlights Crosstalk between αv and β1 Integrins, E-Cadherin and HER-2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somasekhara, D.; Dammalli, M.; Nadumane, V.K. Proteomic Analysis of Human Breast Cancer MCF-7 Cells to Identify Cellular Targets of the Anticancer Pigment OR3 from Streptomyces coelicolor JUACT03. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2023, 195, 236–252. [Google Scholar]

- Jayathirtha, M.; Whitham, D.; Alwine, S.; Donnelly, M.; Neagu, A.-N.; Darie, C.C. Investigating the Function of Human Jumping Translocation Breakpoint Protein (hJTB) and Its Interacting Partners through In-Solution Proteomics of MCF7 Cells. Molecules 2022, 27, 8301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayathirtha, M.; Neagu, A.-N.; Whitham, D.; Alwine, S.; Darie, C.C. Investigation of the effects of overexpression of jumping translocation breakpoint (JTB) protein in MCF7 cells for potential use as a biomarker in breast cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2022, 12, 1784–1823. [Google Scholar]

- Jayathirtha, M.; Channaveerappa, D.; Darie, C. Investigation and Characterization of the Jumping Translocation Breakpoint (JTB) Protein using Mass Spectrometry based Proteomics. FASEB J. 2021, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayathirtha, M.; Neagu, A.-N.; Whitham, D.; Alwine, S.; Darie, C.C. Investigation of the effects of downregulation of jumping translocation breakpoint (JTB) protein expression in MCF7 cells for potential use as a biomarker in breast cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2022, 12, 4373–4398. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aslebagh, R.; Channaveerappa, D.; Arcaro, K.F.; Darie, C.C. Comparative two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (2D-PAGE) of human milk to identify dysregulated proteins in breast cancer. Electrophoresis 2018, 39, 1723–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, A.-P.; Gibert, B. HspB1, HspB5 and HspB4 in Human Cancers: Potent Oncogenic Role of Some of Their Client Proteins. Cancers 2014, 6, 333–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Liu, T.T.; Wang, H.H.; Hong, H.M.; Yu, A.L.; Feng, H.P.; Chang, W.W. Hsp27 participates in the maintenance of breast cancer stem cells through regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition and nuclear factor-κB. Breast Cancer Res. 2011, 13, R101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, B.-B.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.-G.; Liu, H. Significant correlation between HSPA4 and prognosis and immune regulation in hepatocellular carcinoma. PeerJ 2021, 9, e12315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Dai, W.; Li, Z.; Tang, L.; Chen, J.; Chen, C. HSPA4 Knockdown Retarded Progression and Development of Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 2021, 13, 4679–4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Tu, Y.; Wu, N.; Xiao, H. The expression profiles and prognostic values of HSPs family members in Head and neck cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2020, 20, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Tang, Z.; Tan, Z.; Pu, D.; Tan, W.; Zhang, W.; Liu, S. Comprehensive Analysis of Necroptosis-Related Genes as Prognostic Factors and Immunological Biomarkers in Breast Cancer. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 13, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morisaki, T.; Yashiro, M.; Kakehashi, A.; Inagaki, A.; Kinoshita, H.; Fukuoka, T.; Kasashima, H.; Masuda, G.; Sakurai, K.; Kubo, N.; et al. Comparative proteomics analysis of gastric cancer stem cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e110736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, T.; Guan, Y.; Li, Y.-K.; Wu, Q.; Tang, X.-J.; Zeng, X.; Ling, H.; Zou, J. The DNA replication regulator MCM6: An emerging cancer biomarker and target. Clin. Chim. Acta 2021, 517, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Hu, Q.; Tu, M.; Wang, X.; Yang, Z.; Yang, G.; Luo, R. MCM6 promotes metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma via MEK/ERK pathway and serves as a novel serum biomarker for early recurrence. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Tang, S.; Wang, Z.; Cai, L.; Lian, H.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, Y. A pan-cancer analysis of the prognostic and immunological role of β-actin (ACTB) in human cancers. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 6166–6185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misawa, A.; Takayama, K.I.; Fujimura, T.; Homma, Y.; Suzuki, Y.; Inoue, S. Androgen-induced lncRNA POTEF-AS1 regulates apoptosis-related pathway to facilitate cell survival in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 2017, 108, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, N.; Choi, S. Toll-like Receptors from the Perspective of Cancer Treatment. Cancers 2020, 12, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, T.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, K.; Zheng, K.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; et al. α-Actinin1 promotes tumorigenesis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition of gastric cancer via the AKT/GSK3β/β-Catenin pathway. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 5688–5704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovac, B.; Mäkelä, T.P.; Vallenius, T. Increased α-actinin-1 destabilizes E-cadherin-based adhesions and associates with poor prognosis in basal-like breast cancer. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.; Cao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, K.; Chen, Z.; Du, X.; Huo, X.; Kang, H.; et al. Profilin 2 (PFN2) promotes the proliferation, migration, invasion and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of triple negative breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer 2021, 28, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.-B.; Zhang, S.-M.; Xu, Y.-X.; Dang, H.-W.; Liu, C.-X.; Wang, L.-H.; Yang, L.; Hu, J.-M.; Liang, W.-H.; Jiang, J.-F.; et al. PFN2, a novel marker of unfavorable prognosis, is a potential therapeutic target involved in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meric-Bernstam, F.; Chen, H.; Akcakanat, A.; Do, K.-A.; Lluch, A.; Hennessy, B.T.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Mills, G.B.; Gonzalez-Angulo, A.M. Aberrations in translational regulation are associated with poor prognosis in hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2012, 14, R138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oji, Y.; Tatsumi, N.; Fukuda, M.; Nakatsuka, S.-I.; Aoyagi, S.; Hirata, E.; Nanchi, I.; Fujiki, F.; Nakajima, H.; Yamamoto, Y.; et al. The translation elongation factor eEF2 is a novel tumor-associated antigen overexpressed in various types of cancers. Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 44, 1461–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Sun, B.; Hao, L.; Hu, J.; Du, S.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, L.; Gong, L.; Chi, X.; et al. Elevated eukaryotic elongation factor 2 expression is involved in proliferation and invasion of lung squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 58470–58482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuo, L.; Xiang, J.; Pan, X.; Hu, J.; Tang, H.; Liang, L.; Xia, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Huang, A.; et al. PCK1 negatively regulates cell cycle progression and hepatoma cell proliferation via the AMPK/p27Kip1 axis. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; An, S.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, F. PCK1 Regulates Glycolysis and Tumor Progression in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma Through LDHA. OncoTargets Ther. 2020, 13, 2613–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Gou, D.; Xiang, J.; Pan, X.; Gao, Q.; Zhou, P.; Liu, Y.; Hu, J.; Wang, K.; Tang, N. O-GlcNAc modified-TIP60/KAT5 is required for PCK1 deficiency-induced HCC metastasis. Oncogene 2021, 40, 6707–6719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montal, E.D.; Dewi, R.; Bhalla, K.; Ou, L.; Hwang, B.J.; Ropell, A.E.; Gordon, C.; Liu, W.-J.; DeBerardinis, R.J.; Sudderth, J.; et al. PEPCK Coordinates the Regulation of Central Carbon Metabolism to Promote Cancer Cell Growth. Mol. Cell 2015, 60, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.; Chu, P.; Chang, T.; Huang, K.; Hung, W.; Jiang, S.S.; Lin, H.; Tsai, H. Mitochondrial phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase promotes tumor growth in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer via regulation of the mTOR pathway. Cancer Med. 2022, 12, 1588–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Dong, C. Gluconeogenesis in Cancer: Function and Regulation of PEPCK, FBPase, and G6Pase. Trends Cancer 2019, 5, 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Gao, Y.; Liu, J.; Xu, L.; Liu, W.; Huna, A.; Wang, X.; Gong, W. Low expression of PCK2 in breast tumors contributes to better prognosis by inducing senescence of cancer cells. IUBMB Life 2022, 74, 896–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangha, A.K.; Kantidakis, T. The Aminoacyl-tRNA Synthetase and tRNA Expression Levels Are Deregulated in Cancer and Correlate Independently with Patient Survival. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 3001–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Guo, R.; Li, Y.; Kang, G.; Wu, Y.; Cheng, J.; Jia, J.; Wang, W.; Li, Z.; Wang, A.; et al. Contribution of upregulated aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis to metabolic dysregulation in gastric cancer. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 36, 3113–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.; Yoon, I.; Han, J.M.; Kim, S. Functional and pathologic association of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases with cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, S.H.; Kim, H.S.; Jung, S.H.; Xu, H.D.; Jeong, Y.B.; Chung, Y.J. Implication of leucyl-tRNA synthetase 1 (LARS1) over-expression in growth and migration of lung cancer cells detected by siRNA targeted knock-down analysis. Exp. Mol. Med. 2008, 40, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, K.; Gogonea, V.; Fox, P.L. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases of the multi-tRNA synthetase complex and their role in tumorigenesis. Transl. Oncol. 2022, 19, 101392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottoni, A.; Vignali, C.; Piccin, D.; Tagliati, F.; Luchin, A.; Zatelli, M.C.; Uberti, E.C.D. Proteasomes and RARS modulate AIMP1/EMAP II secretion in human cancer cell lines. J. Cell. Physiol. 2007, 212, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-Y.; Shi, K.-Z.; Liao, X.-Y.; Li, S.-J.; Bao, D.; Qian, Y.; Li, D.-J. The Silence of PSMC6 Inhibits Cell Growth and Metastasis in Lung Adenocarcinoma. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 9922185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, T.-J.; Wu, C.-C.; Phan, N.N.; Liu, Y.-H.; Ta, H.D.K.; Anuraga, G.; Wu, Y.-F.; Lee, K.-H.; Chuang, J.-Y.; Wang, C.-Y. Prognoses and genomic analyses of proteasome 26S subunit, ATPase (PSMC) family genes in clinical breast cancer. Aging 2021, 13, 17970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Qi, Y.; Kong, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhai, J.; Yang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Wang, J. Molecular and Clinical Characterization of CCT2 Expression and Prognosis via Large-Scale Transcriptome Profile of Breast Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 614497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Lu, Y.; Yan, X.; Lu, Q.; Sun, Y.; Wan, X.; Li, Y.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Jiang, G. Current understanding on the role of CCT3 in cancer research. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 961733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boudiaf-Benmammar, C.; Cresteil, T.; Melki, R. The cytosolic chaperonin CCT/TRiC and cancer cell proliferation. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e60895. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.H.; Zhao, B.B.; Qin, C.; Wang, Y.Y.; Li, Z.R.; Cao, H.T.; Yang, X.Y.; Zhou, X.T.; Wang, W.B. IFIT1 modulates the proliferation, migration and invasion of pancreatic cancer cells via Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Cell. Oncol. 2021, 44, 1425–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, H.H.; Goyal, S.; Taunk, N.K.; Wu, H.; Moran, M.S.; Haffty, B.G. Interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 1 (IFIT1) as a prognostic marker for local control in T1-2 N0 breast cancer treated with breast-conserving surgery and radiation therapy (BCS + RT). Breast J. 2013, 19, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidugu, V.K.; Wu, M.-M.; Yen, A.-H.; Pidugu, H.B.; Chang, K.-W.; Liu, C.-J.; Lee, T.-C. IFIT1 and IFIT3 promote oral squamous cell carcinoma metastasis and contribute to the anti-tumor effect of gefitinib via enhancing p-EGFR recycling. Oncogene 2019, 38, 3232–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Fan, Y.; Yu, X.; Mao, X.; Jin, F. PTBP1 promotes the growth of breast cancer cells through the PTEN/Akt pathway and autophagy. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 8930–8939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Shen, L.; Huang, L.; Lei, S.; Cai, X.; Breitzig, M.; Zhang, B.; Yang, A.; Ji, W.; Huang, M.; et al. PTBP1 enhances exon11a skipping in Mena pre-mRNA to promote migration and invasion in lung carcinoma cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Gene Regul. Mech. 2019, 1862, 858–869. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W.; Zhou, B.-L.; Rong, L.-J.; Ye, L.; Xu, H.-J.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, X.-J.; Liu, W.-D.; Zhu, B.; Wang, L.; et al. Roles of PTBP1 in alternative splicing, glycolysis, and oncogensis. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B 2020, 21, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, B.; Li, Y.; Shen, J.; Wei, Y.; Li, H.; Chen, S.; Yang, H.; Zeng, F.; Liu, C.; et al. DDX19A Promotes Metastasis of Cervical Squamous Cell Carcinoma by Inducing NOX1-Mediated ROS Production. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 6299744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Xiong Chen, Z.; Rane, G.; Satendra Singh, S.; Choo, Z.E.; Wang, C.; Yuan, Y.; Zea Tan, T.; Arfuso, F.; Yap, C.T.; et al. Wanted DEAD/H or Alive: Helicases Winding Up in Cancers. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2017, 109, djw278. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.-T.; Xing, X.-F.; Dong, B.; Cheng, X.-J.; Guo, T.; Du, H.; Wen, X.-Z.; Ji, J.-F. Higher autocrine motility factor/glucose-6-phosphate isomerase expression is associated with tumorigenesis and poorer prognosis in gastric cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 2018, 10, 4969–4980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Yi, J.; Tan, S.; Zeng, Y.; Zou, L.; Zhang, C.; Liu, L.; Yi, P.; Fan, P.; Yu, J. GPI: An indicator for immune infiltrates and prognosis of human breast cancer from a comprehensive analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 995972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Deng, X.; Sun, R.; Luo, M.; Liang, M.; Gu, B.; Zhang, T.; Peng, Z.; Lu, Y.; Tian, C.; et al. GPI Is a Prognostic Biomarker and Correlates With Immune Infiltrates in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 752642. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo-Pérez, J.C.; Rivero-Segura, N.A.; Marín-Hernández, A.; Moreno-Sánchez, R.; Rodríguez-Enríquez, S. GPI/AMF inhibition blocks the development of the metastatic phenotype of mature multi-cellular tumor spheroids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Mol. Cell Res. 2014, 1843, 1043–1053. [Google Scholar]

- Nami, B.; Wang, Z. Genetics and Expression Profile of the Tubulin Gene Superfamily in Breast Cancer Subtypes and Its Relation to Taxane Resistance. Cancers 2018, 10, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.; Jiao, Z.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, S. Elevated TUBA1A Might Indicate the Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Gastric Cancer, Being Associated with the Infiltration of Macrophages in the Tumor Immune Microenvironment. J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. 2020, 29, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Sun, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, M.; Yang, X.; Kuang, R.; Zheng, H. Meta-Analysis of EMT Datasets Reveals Different Types of EMT. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156839. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, C.; Chen, J.; Li, S.; Zhou, J.; Fu, J.; Sun, W.; Wang, W. KDM6 Demethylases and Their Roles in Human Cancers. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 779918. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, J.; Menezes, S.V.; Abbassi, R.H.; Munoz, L. Histone lysine demethylases and their functions in cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 148, 2375–2388. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, S.; Kato, K.; Nakamura, K.; Nakano, R.; Kubota, K.; Hamada, H. Neural cell adhesion molecule 2 as a target molecule for prostate and breast cancer gene therapy. Cancer Sci. 2011, 102, 808–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, C.; Ju, H.; Liu, W.; Zhang, X.; Miao, S.; Wang, L.; Sun, Q.; Song, W. Rhomboid domain-containing protein 1 promotes breast cancer progression by regulating the p-Akt and CDK2 levels. Cell Commun. Signal. 2018, 16, 65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ren, X.; Song, W.; Liu, W.; Guan, X.; Miao, F.; Miao, S.; Wang, L. Rhomboid domain containing 1 inhibits cell apoptosis by upregulating AP-1 activity and its downstream target Bcl-3. FEBS Lett. 2013, 587, 1793–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Deng, Y.; Ye, J.; Zhuo, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, X.; Luo, Y.; Feng, Y.; et al. Aberrant Expression of Citrate Synthase is Linked to Disease Progression and Clinical Outcome in Prostate Cancer. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 6149–6163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schlichtholz, B.; Turyn, J.; Goyke, E.; Biernacki, M.; Jaskiewicz, K.; Sledzinski, Z.; Swierczynski, J. Enhanced Citrate Synthase Activity in Human Pancreatic Cancer. Pancreas 2005, 30, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, T.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Di, W.; Zhang, S. Citrate synthase expression affects tumor phenotype and drug resistance in human ovarian carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e115708. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.-C.; Cheng, T.-L.; Tsai, W.-H.; Tsai, H.-J.; Hu, K.-H.; Chang, H.-C.; Yeh, C.-W.; Chen, Y.-C.; Liao, C.-C.; Chang, W.-T. Loss of the respiratory enzyme citrate synthase directly links the Warburg effect to tumor malignancy. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 785. [Google Scholar]

- MacPherson, S.; Horkoff, M.; Gravel, C.; Hoffmann, T.; Zuber, J.; Lum, J.J. STAT3 Regulation of Citrate Synthase Is Essential during the Initiation of Lymphocyte Cell Growth. Cell Rep. 2017, 19, 910–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Lv, Y.; Xu, F.; Xiu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Deng, L. LAMTOR3 is a prognostic biomarker in kidney renal clear cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24648. [Google Scholar]

- Marina, M.; Wang, L.; Conrad, S.E. The scaffold protein MEK Partner 1 is required for the survival of estrogen receptor positive breast cancer cells. Cell Commun. Signal. 2012, 10, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Araujo, M.E.; Erhart, G.; Buck, K.; Müller-Holzner, E.; Hubalek, M.; Fiegl, H.; Campa, D.; Canzian, F.; Eilber, U.; Chang-Claude, J.; et al. Polymorphisms in the gene regions of the adaptor complex LAMTOR2/LAMTOR3 and their association with breast cancer risk. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e53768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, O.S.; Hong, S.K.; Kwon, S.J.; Go, Y.H.; Oh, E.; Cha, H.J. BCL2 induced by LAMTOR3/MAPK is a druggable target of chemoradioresistance in mesenchymal lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 2017, 403, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, J.P.; Qian, K.; Lee, J.S.; Zhou, J.; Han, X.; Zhang, B.; Ong, Q.; Ni, W.; Jiang, M.; Ruan, H.B.; et al. O-GlcNAcase targets pyruvate kinase M2 to regulate tumor growth. Oncogene 2020, 39, 560–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olechnowicz, A.; Oleksiewicz, U.; Machnik, M. KRAB-ZFPs and cancer stem cells identity. Genes Dis. 2022, 10, 1820–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhang, H.; Liang, C.; Li, B. Identification of a 5-Gene Signature Predicting Progression and Prognosis of Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 4401–4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleksiewicz, U.; Gładych, M.; Raman, A.T.; Heyn, H.; Mereu, E.; Chlebanowska, P.; Andrzejewska, A.; Sozańska, B.; Samant, N.; Fąk, K.; et al. TRIM28 and Interacting KRAB-ZNFs Control Self-Renewal of Human Pluripotent Stem Cells through Epigenetic Repression of Pro-differentiation Genes. Stem Cell Rep. 2017, 9, 2065–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, M.; Wen, J.; Xue, L.; Han, S.; Liang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Yu, J.; et al. PA2G4 promotes the metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma by stabilizing FYN mRNA in a YTHDF2-dependent manner. Cell Biosci. 2022, 12, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novita Sari, I.; Setiawan, T.; Seock Kim, K.; Toni Wijaya, Y.; Won Cho, K.; Young Kwon, H. Metabolism and function of polyamines in cancer progression. Cancer Lett. 2021, 519, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinyele, O.; Wallace, H.M. Characterising the Response of Human Breast Cancer Cells to Polyamine Modulation. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snezhkina, A.V.; Krasnov, G.S.; Lipatova, A.V.; Sadritdinova, A.F.; Kardymon, O.L.; Fedorova, M.S.; Melnikova, N.V.; Stepanov, O.A.; Zaretsky, A.R.; Kaprin, A.D. The Dysregulation of Polyamine Metabolism in Colorectal Cancer Is Associated with Overexpression of c-Myc and C/EBPβ rather than Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis Infection. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 2353560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamble, L.D.; Hogarty, M.D.; Liu, X.; Ziegler, D.S.; Marshall, G.; Norris, M.D.; Haber, M. Polyamine pathway inhibition as a novel therapeutic approach to treating neuroblastoma. Front. Oncol. 2012, 2, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Checa-Rojas, A.; Delgadillo-Silva, L.F.; Velasco-Herrera, M.d.C.; Andrade-Domínguez, A.; Gil, J.; Santillán, O.; Lozano, L.; Toledo-Leyva, A.; Ramírez-Torres, A.; Talamas-Rohana, P.; et al. GSTM3 and GSTP1: Novel players driving tumor progression in cervical cancer. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 21696–21714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Yang, J.; You, L.; Dai, M.; Zhao, Y. GSTM3 Function and Polymorphism in Cancer: Emerging but Promising. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 10377–10388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lollo, V.; Canciello, A.; Orsini, M.; Bernabò, N.; Ancora, M.; Federico, M.; Curini, V.; Mattioli, M.; Russo, V.; Mauro, A.; et al. Transcriptomic and computational analysis identified LPA metabolism, KLHL14 and KCNE3 as novel regulators of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Y.; He, L.; Shay, C.; Lang, L.; Loveless, J.; Yu, J.; Chemmalakuzhy, R.; Jiang, H.; Liu, M.; Teng, Y. Nck-associated protein 1 associates with HSP90 to drive metastasis in human non-small-cell lung cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Qin, H.; Bahassan, A.; Bendzunas, N.G.; Kennedy, E.J.; Cowell, J.K. The WASF3-NCKAP1-CYFIP1 Complex Is Essential for Breast Cancer Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 5133–5142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ge, J.; Zhang, W.; Xie, X.; Zhong, X.; Tang, S. NCKAP1 is a Prognostic Biomarker for Inhibition of Cell Growth in Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Front. Genet. 2022, 13, 764957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.P.; Kan, A.; Ling, Y.H.; Lu, L.H.; Mei, J.; Wei, W.; Li, S.H.; Guo, R.P. NCKAP1 improves patient outcome and inhibits cell growth by enhancing Rb1/p53 activation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolussi, A.; D’Inzeo, S.; Capalbo, C.; Giannini, G.; Coppa, A. The role of peroxiredoxins in cancer. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 6, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.H.; Jo, M.; Kim, Y.R.; Lee, C.-K.; Hong, J.T. Roles of peroxiredoxins in cancer, neurodegenerative diseases and inflammatory diseases. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 163, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Gao, X.; Ma, Q.; Yu, Z.; Huang, S. Rab8A promotes breast cancer progression by increasing surface expression of Tropomyosin-related kinase B. Cancer Lett. 2022, 535, 215629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboubakr, H.; Lavanya, S.; Thirupathi, M.; Rohini, R.; Sarita, R. Human Rab8b Protein as a Cancer Target—An In Silico Study. J. Comput. Sci. Syst. Biol. 2016, 9, 132–149. [Google Scholar]

- Demir, K.; Kirsch, N.; Beretta, C.A.; Erdmann, G.; Ingelfinger, D.; Moro, E.; Argenton, F.; Carl, M.; Niehrs, C.; Boutros, M. RAB8B Is Required for Activity and Caveolar Endocytosis of LRP6. Cell Rep. 2013, 4, 1224–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzeng, H.-T.; Wang, Y.-C. Rab-mediated vesicle trafficking in cancer. J. Biomed. Sci. 2016, 23, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, N.; Song, Z.; Chen, B.; Cheng, J.; Zhou, W. A Novel Circular RNA circCSPP1 Promotes Liver Cancer Progression by Sponging miR-1182. OncoTargets Ther. 2021, 14, 2829–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, N.; Pham, T.V.H.; Hartomo, T.B.; Lee, M.J.; Hasegawa, D.; Takeda, H.; Kawasaki, K.; Kosaka, Y.; Yamamoto, T.; Morikawa, S.; et al. Rab15 expression correlates with retinoic acid-induced differentiation of neuroblastoma cells. Oncol. Rep. 2011, 26, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Villagomez, F.R.; Medina-Contreras, O.; Cerna-Cortes, J.F.; Patino-Lopez, G. The role of the oncogenic Rab35 in cancer invasion, metastasis, and immune evasion, especially in leukemia. Small GTPases 2020, 11, 334–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmapal, D.; Jyothy, A.; Mohan, A.; Balagopal, P.G.; George, N.A.; Sebastian, P.; Maliekal, T.T.; Sengupta, S. β-Tubulin Isotype, TUBB4B, Regulates The Maintenance of Cancer Stem Cells. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 788024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobierajska, K.; Ciszewski, W.M.; Wawro, M.E.; Wieczorek-Szukała, K.; Boncela, J.; Papiewska-Pajak, I.; Niewiarowska, J.; Kowalska, M.A. TUBB4B Downregulation Is Critical for Increasing Migration of Metastatic Colon Cancer Cells. Cells 2019, 8, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Miao, C.; Liang, C.; Shao, P.; Wang, Z.; Li, J. Silencing CAPN2 Expression Inhibited Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Cells Proliferation and Invasion via AKT/mTOR Signal Pathway. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 2593674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Liang, C.; Tian, Y.; Xu, A.; Zhu, J.; Zhao, K.; Zhang, J.; Hua, Y.; Liu, S.; Dong, H.; et al. Overexpression of CAPN2 promotes cell metastasis and proliferation via AKT/mTOR signaling in renal cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 97811–97821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Yang, R.; Song, J.; Wang, X.; Dong, W. Calpain2 Upregulation Regulates EMT-Mediated Pancreatic Cancer Metastasis via the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 783592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Haijuan, F.; Liu, X.; Lei, Q.; Zhang, Y.; She, X.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Q.; Sun, Y.; Li, G.; et al. LINC00470 Coordinates the Epigenetic Regulation of ELFN2 to Distract GBM Cells Autophagy. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 2267–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.Q.; Zhang, J.J.; Song, H.J.; Li, D.W. Overexpression of CST4 promotes gastric cancer aggressiveness by activating the ELFN2 signaling pathway. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2017, 7, 2290–2304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Yang, Y.; Friedman, P.A. Na/H Exchange Regulatory Factor 1, a Novel AKT-associating Protein, Regulates Extracellular Signal-regulated Kinase Signaling through a B-Raf–Mediated Pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell 2008, 19, 1637–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocamo, S.; Binato, R.; Santos, E.; de Paula, B.; Abdelhay, E. Translational Results of Zo-NAnTax: A Phase II Trial of Neoadjuvant Zoledronic Acid in HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q.; Jiao, Y.; Hao, Y.; Yan, S.; Lyu, N.; Gao, H.; Li, D.; Liu, Q.; Zheng, J.; Song, N. Targeting of NHERF1 through RNA interference inhibits the proliferation and migration of metastatic prostate cancer cells. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 11, 1149–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Z.; Zhu, H.; Sun, H.; Hua, Y.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, J.; Wang, X. Adipose Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomal microRNA-1236 Reduces Resistance of Breast Cancer Cells to Cisplatin by Suppressing SLC9A1 and the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 8733–8744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Morales, F.C.; Kreimann, E.L.; Georgescu, M.-M. PTEN tumor suppressor associates with NHERF proteins to attenuate PDGF receptor signaling. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 910–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.H.; Chung, J.-Y.; Chung, E.J.; Sears, J.D.; Lee, J.-W.; Bae, D.-S.; Hewitt, S.M. Prognostic significance of annexin A2 and annexin A4 expression in patients with cervical cancer. BMC Cancer 2016, 16, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Sun, C.; Hu, Z.; Wang, W. The role of annexin A4 in cancer. Front. Biosci. Landmark Ed. 2016, 21, 949–957. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.-L.; Huang, H.-C.; Juan, H.-F. Revealing the Molecular Mechanism of Gastric Cancer Marker Annexin A4 in Cancer Cell Proliferation Using Exon Arrays. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, B.; Guo, C.; Liu, S.; Sun, M.Z. Annexin A4 and cancer. Clin. Chim. Acta Int. J. Clin. Chem. 2015, 447, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.F.; Lee, Y.C.; Wang, Y.Y.; Wang, C.H.; Hou, M.F.; Yuan, S.S.F. YWHAE promotes proliferation, metastasis, and chemoresistance in breast cancer cells. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 2019, 35, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, Y.; Ye, F.; He, X.-X. The role of YWHAZ in cancer: A maze of opportunities and challenges. J. Cancer 2020, 11, 2252–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.C.; Li, C.F.; Chen, I.H.; Lai, M.T.; Lin, Z.J.; Korla, P.K.; Chai, C.Y.; Ko, G.; Chen, C.M.; Hwang, T. YWHAZ amplification/overexpression defines aggressive bladder cancer and contributes to chemo-/radio-resistance by suppressing caspase-mediated apoptosis. J. Pathol. 2019, 248, 476–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, X.; Ji, Q.; Yang, L.; Li, J.; Long, X.; Ye, M.; Huang, K.; Zhu, X. Immune Characteristics and Prognosis Analysis of the Proteasome 20S Subunit Beta 9 in Lower-Grade Gliomas. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 875131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Horiuchi, A.; Sano, K.; Hiraoka, N.; Kasai, M.; Ichimura, T.; Sudo, T.; Tagawa, Y.-I.; Nishimura, R.; Ishiko, O.; et al. Potential role of LMP2 as tumor-suppressor defines new targets for uterine leiomyosarcoma therapy. Sci. Rep. 2011, 1, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Li, X.; Zhang, J. mTOR Signaling in Cancer and mTOR Inhibitors in Solid Tumor Targeting Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.J.; Pan, W.W.; Liu, S.B.; Shen, Z.F.; Xu, Y.; Hu, L.L. ERK/MAPK signalling pathway and tumorigenesis. Exp. Ther. Med. 2020, 19, 1997–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rascio, F.; Spadaccino, F.; Rocchetti, M.T.; Castellano, G.; Stallone, G.; Netti, G.S.; Ranieri, E. The Pathogenic Role of PI3K/AKT Pathway in Cancer Onset and Drug Resistance: An Updated Review. Cancers 2021, 13, 3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. Targeting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, L.; Tan, S.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, J.; Wang, H.; Oyang, L.; Tian, Y.; Liu, L.; Su, M.; Wang, H.; et al. Role of the NFκB-signaling pathway in cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2018, 11, 2063–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madden, E.; Logue, S.E.; Healy, S.J.; Manie, S.; Samali, A. The role of the unfolded protein response in cancer progression: From oncogenesis to chemoresistance. Biol. Cell 2019, 111, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrefaei, A.F.; Abu-Elmagd, M. LRP6 Receptor Plays Essential Functions in Development and Human Diseases. Genes 2022, 13, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.P.; Ilter, D.; Low, V.; Drapela, S.; Schild, T.; Mullarky, E.; Han, J.; Elia, I.; Broekaert, D.; Rosenzweig, A.; et al. Altered propionate metabolism contributes to tumour progression and aggressiveness. Nat. Metab. 2022, 4, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasmann, G.; Smolle, E.; Olschewski, H.; Leithner, K. Gluconeogenesis in cancer cells—Repurposing of a starvation-induced metabolic pathway? Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Rev. Cancer 2019, 1872, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Han, M.; Zhang, H.; Liu, F.; Pan, Y.; Zhu, J.; Liao, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, B. Structures and biological functions of zinc finger proteins and their roles in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biomark. Res. 2022, 10, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Ji, T.; Zhang, H.; Dong, W.; Chen, X.; Xu, P.; Chen, D.; Liang, X.; Yin, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. A Pck1-directed glycogen metabolic program regulates formation and maintenance of memory CD8+ T cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, L.; Sandhu, J.K.; Harper, M.-E.; Cuperlovic-Culf, M. Role of Glutathione in Cancer: From Mechanisms to Therapies. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halama, A.; Suhre, K. Advancing Cancer Treatment by Targeting Glutamine Metabolism—A Roadmap. Cancers 2022, 14, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, B.J.; Stine, Z.E.; Dang, C.V. From Krebs to clinic: Glutamine metabolism to cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2016, 16, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.-X.; Jin, L.; Sun, S.-J.; Liu, P.; Feng, X.; Cheng, Z.-L.; Liu, W.-R.; Guan, K.-L.; Shi, Y.-H.; Yuan, H.-X.; et al. Metabolic reprogramming by PCK1 promotes TCA cataplerosis, oxidative stress and apoptosis in liver cancer cells and suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene 2018, 37, 1637–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millward, C.A.; DeSantis, D.; Hsieh, C.-W.; Heaney, J.D.; Pisano, S.; Olswang, Y.; Reshef, L.; Beidelschies, M.; Puchowicz, M.; Croniger, C.M. Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (Pck1) helps regulate the triglyceride/fatty acid cycle and development of insulin resistance in mice. J. Lipid Res. 2010, 51, 1452–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithner, K.; Triebl, A.; Trötzmüller, M.; Hinteregger, B.; Leko, P.; Wieser, B.I.; Grasmann, G.; Bertsch, A.L.; Züllig, T.; Stacher, E.; et al. The glycerol backbone of phospholipids derives from noncarbohydrate precursors in starved lung cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 6225–6230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadria, M.; Layton, A.T. Interactions among mTORC, AMPK and SIRT: A computational model for cell energy balance and metabolism. Cell Commun. Signal. 2021, 19, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.-C.; Peng, D.; Cai, Z.; Lin, H.-K. AMPK signaling and its targeting in cancer progression and treatment. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 85, 52–68. [Google Scholar]

- Penugurti, V.; Mishra, Y.G.; Manavathi, B. AMPK: An odyssey of a metabolic regulator, a tumor suppressor, and now a contextual oncogene. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Rev. Cancer 2022, 1877, 188785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, F.; Tseng, Y.-C.; Liu, S.-T.; Chou, Y.-L.; Lin, C.-C.; Sung, P.-H.; Uchida, K.; Lin, L.-Y.; Hwang, P.-P. Induction of Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxykinase (PEPCK) during Acute Acidosis and Its Role in Acid Secretion by V-ATPase-Expressing Ionocytes. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2015, 11, 712–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Meng, S.; Xiang, M.; Ma, H. Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase in cell metabolism: Roles and mechanisms beyond gluconeogenesis. Mol. Metab. 2021, 53, 101257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).