Abstract

Marine isonitriles represent the largest group of natural products carrying the remarkable isocyanide moiety. Together with marine isothiocyanates and formamides, which originate from the same biosynthetic pathways, they offer diverse biological activities and in spite of their exotic nature they may constitute potential lead structures for pharmaceutical development. Among other biological activities, several marine isonitriles show antimalarial, antitubercular, antifouling and antiplasmodial effects. In contrast to terrestrial isonitriles, which are mostly derived from α-amino acids, the vast majority of marine representatives are of terpenoid origin. An overview of all known marine isonitriles and their congeners will be given and their biological and chemical aspects will be discussed.

1. Introduction

The isonitrile group is a unique functionality as it is isoeletronic to carbon monoxide and shows a high affinity towards transition metals which might cause toxic effects in vivo. Moreover, the isonitrile carbon has an uncommon valency state and the exergonic transformation of isonitriles to amides or related structures in countless named or unnamed two- or multi-component reactions such as Passerini- or Ugi-reactions is paramount. Most isonitriles employed in chemical reactions are man-made and are frequently derived from the corresponding amines. On the other hand, the ocurrence of the isonitrile function in natural products is still regarded as a curiosity by many due to its potential reactivity with diverse nucleophiles and electrophiles.

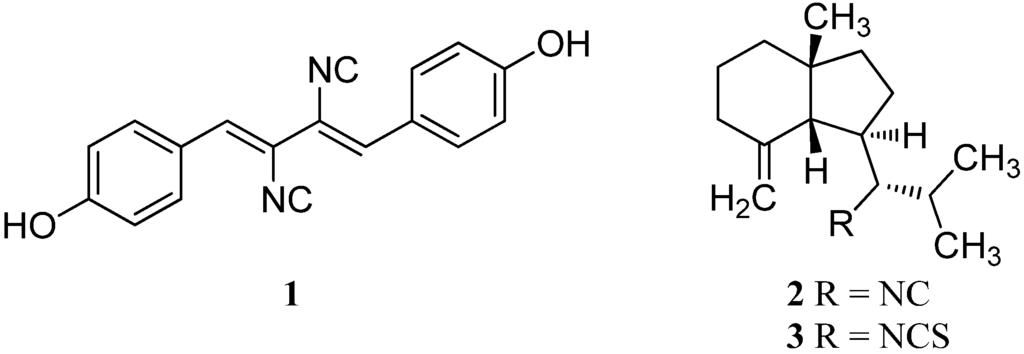

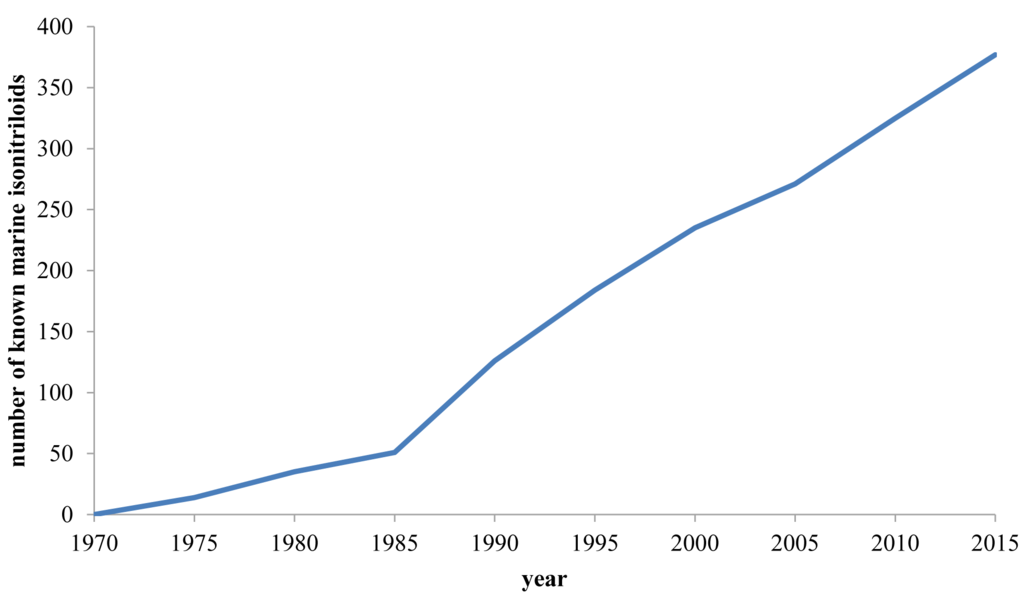

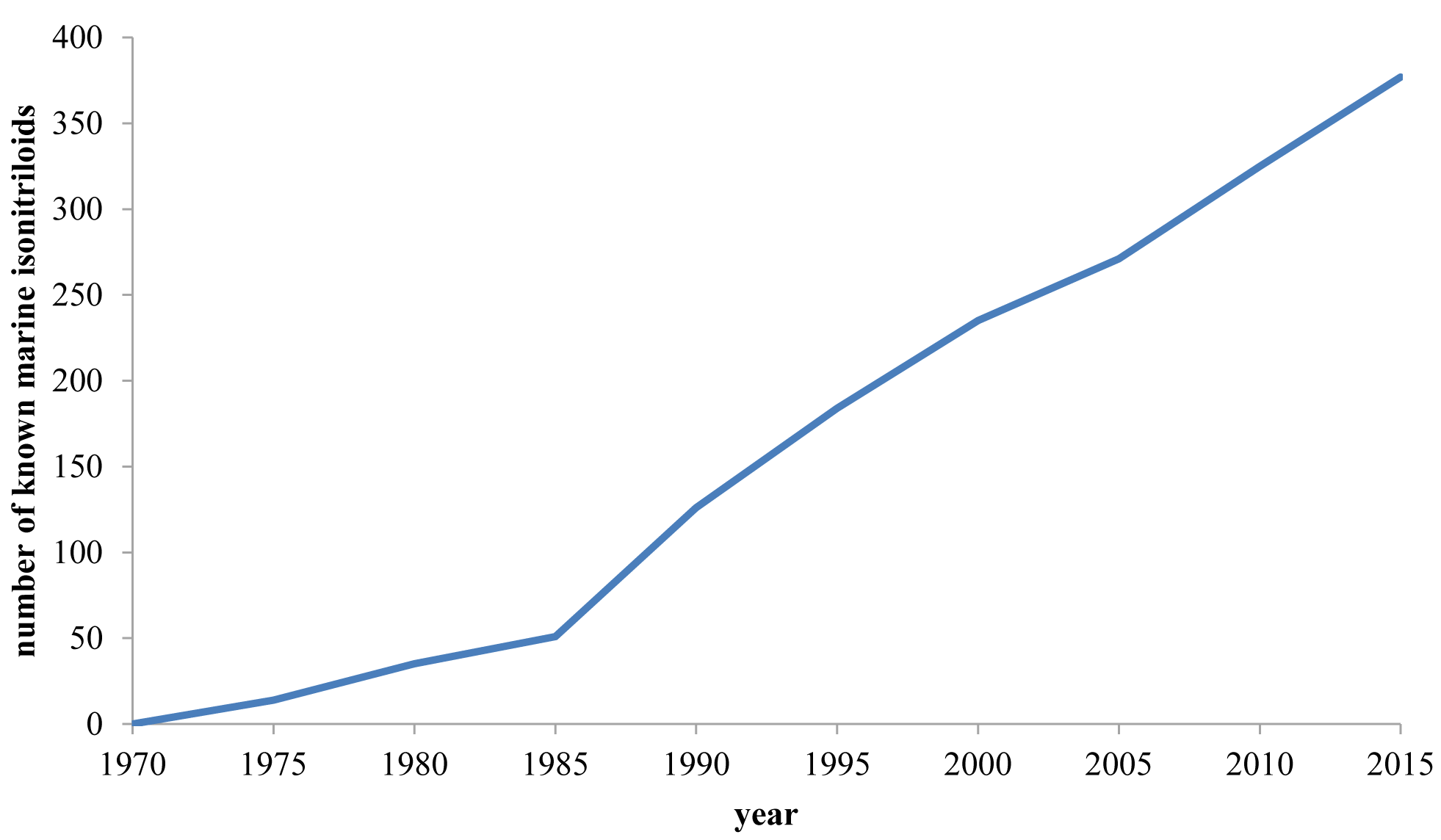

Until 1973, the terrestrial isonitrile xanthocillin (1) was the only known natural isonitrile which was isolated by Rothe in 1950 from Penicillium notatum (Figure 1) [1]. Then, Cafieri et al. isolated the first marine isonitrile, axisonitrile-1 (2), together with axisothiocyanate-1 (3) from the marine sponge Axinella cannabina collected in the Bay of Taranto (Italy) [2]. In contrast to the terrestrial isonitriles, which are mostly derived from amino acids, the majority of marine isonitriles have a terpenoid origin. Not much later, other research groups reported the isolation of further marine isonitriles and related compounds and new representatives are constantly being identified [3,4]. To date, about 200 isonitrile natural products are known and 63% of them originate from marine sources.

Early on, Fattorusso et al. and Burreson et al. observed that the isonitriles occurred usually with the corresponding formamide and isothiocyanate compounds [5,6]. Additionally, structurally closely related cyanates, thiocyanates and carbonimidic dichlorides have been reported, albeit in smaller numbers. The marine isonitriles can be divided into four groups, the sesquiterpenoids (Section 2.1), the diterpenoids (Section 2.2), carbonimidic dichlorides (Section 2.3) and miscellaneous structures (Section 2.4) which can not be classified into the previous groups. The sesquiterpenoids only bear a single nitrogenous functional group and some of them are additionally oxygenated. However, the diterpenoids can possess a higher degree of functionalization. The most complex compounds are the kalihinols which are functionalized with a tetrahydrofuran- or a tetrahydropyran-ring along with hydroxy, chloro or olefinic moieties. Marine isonitriles have been isolated from sponges and from nudibranchs but the latter are probably mostly of dietary origin.

Figure 1.

Xanthocillin (1), axisonitrile-1 (2) and axisothiocyanate (3).

Figure 1.

Xanthocillin (1), axisonitrile-1 (2) and axisothiocyanate (3).

The first review about isonitrile natural products was published by Edenborough and Herbert in 1988 [7] while the first review on marine isonitriles and related compounds by Chang and Scheuer appeared five years later [8]. Chang also published a review on marine and terrestrial isonitriles along with their congeners in 2000 [9]. In the same year Garson et al. published a review about the structures, biosynthesis and ecology of marine isonitriles [10]. Reviews about the biosynthesis of marine isonitriles were published by Garson in 1989 [11], by Chang and Scheuer in 1990 [12], and by Garson in 1993 [13]. An update of Garson’s 1988 review appeared in 2004 [14]. A review about isolation, biological activity and chemical synthesis of isocyanoterpenes was published in 2015 by Schnermann and Shenvi [15].

Since the number of known marine-derived isonitrile natural products has increased significantly since 2000, we intend to give the reader a complete overview of all members of this compound class known to date. In addition, aspects about biosynthesis and bioactivity will be discussed.

2. Marine Isonitriles and Related Compounds

Most marine isonitriles and their formamide and isothiocyanate congeners are either sesquiterpenoids (Section 2.1) or diterpenoids (Section 2.2). The sesquiterpenoids have only one nitrogenous functional group whereas the diterpenes bear up to three functional groups. Carbonimidic dichlorides (Section 2.3), which originate from the corresponding isonitriles or isothiocyanates, are also known. Finally, there are some miscellaneous structures (Section 2.4) which can not be classified in the previous sections.

2.1. Sesquiterpenoids

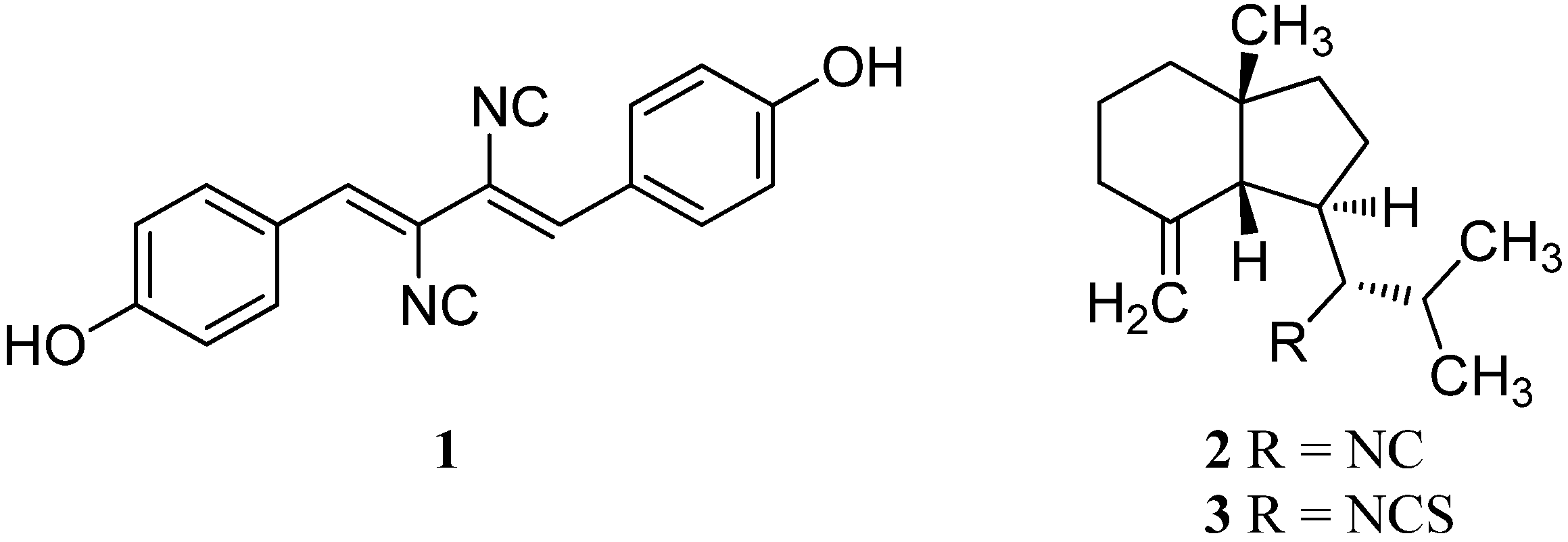

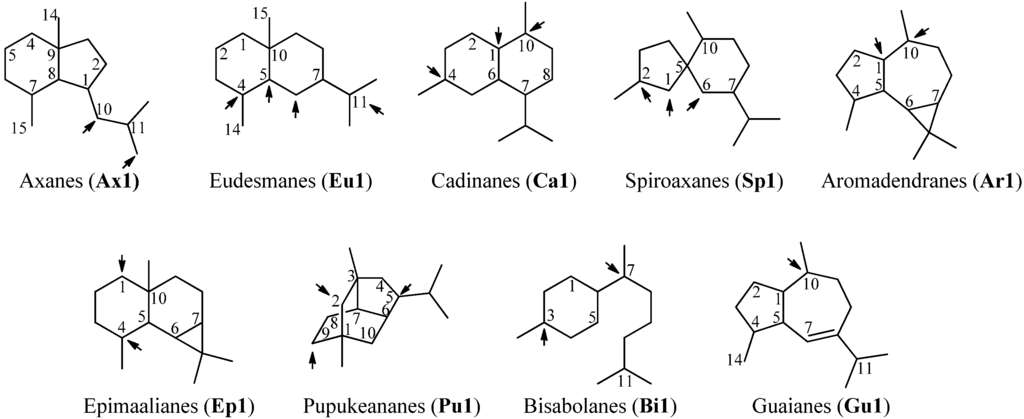

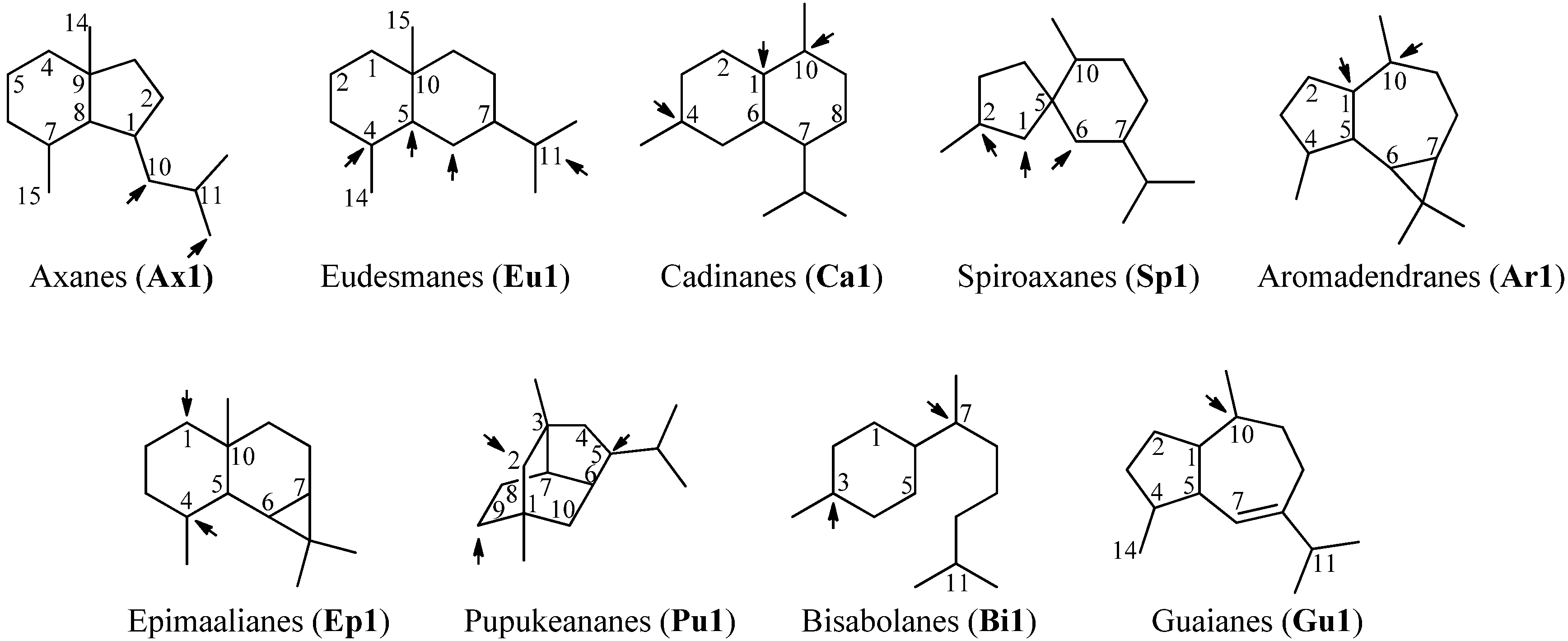

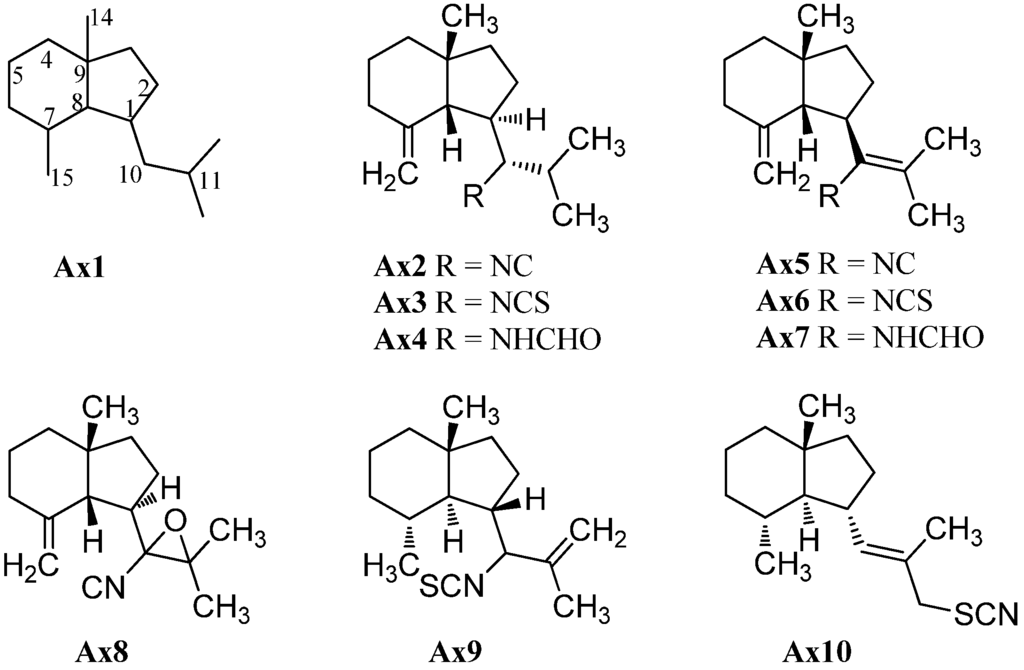

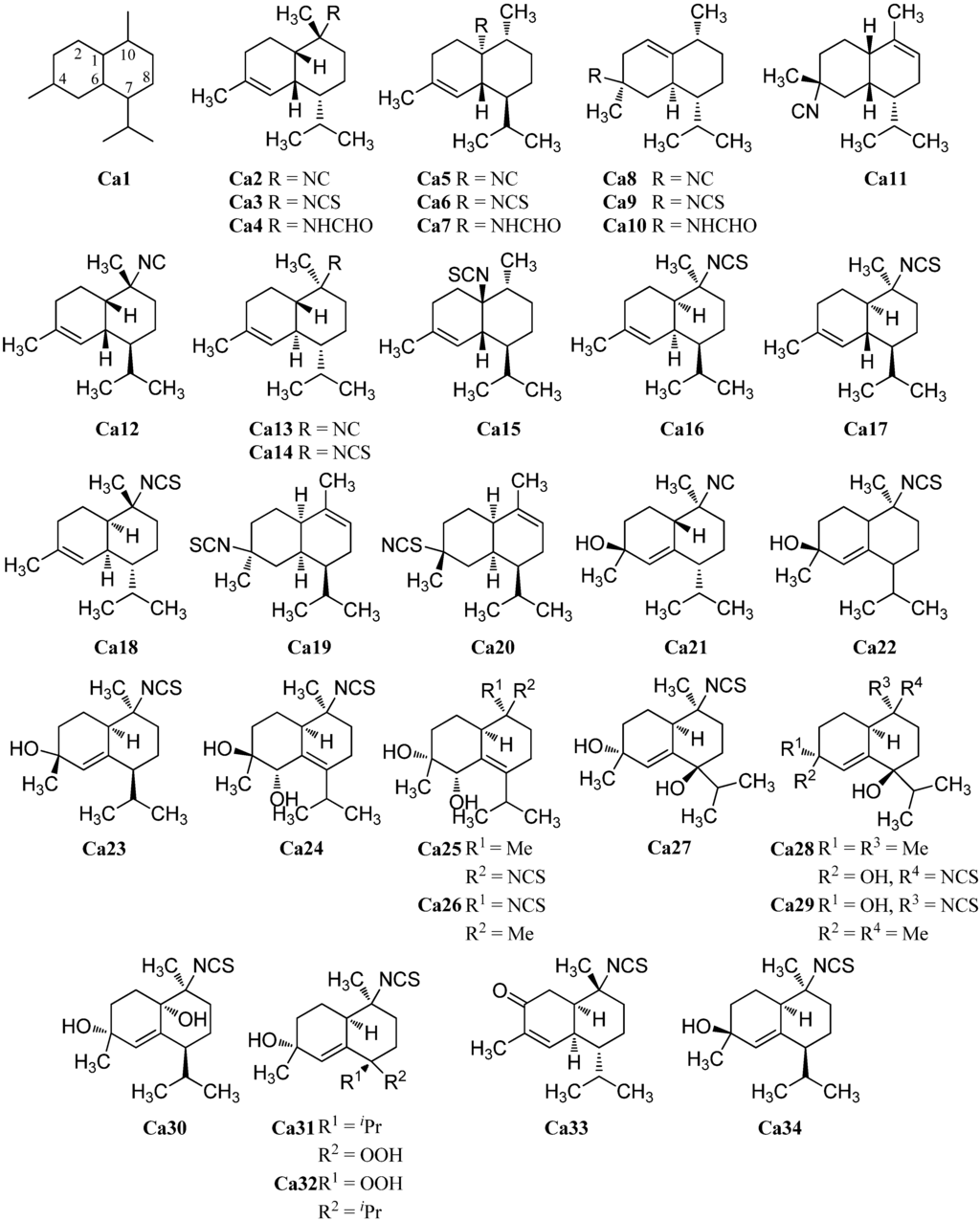

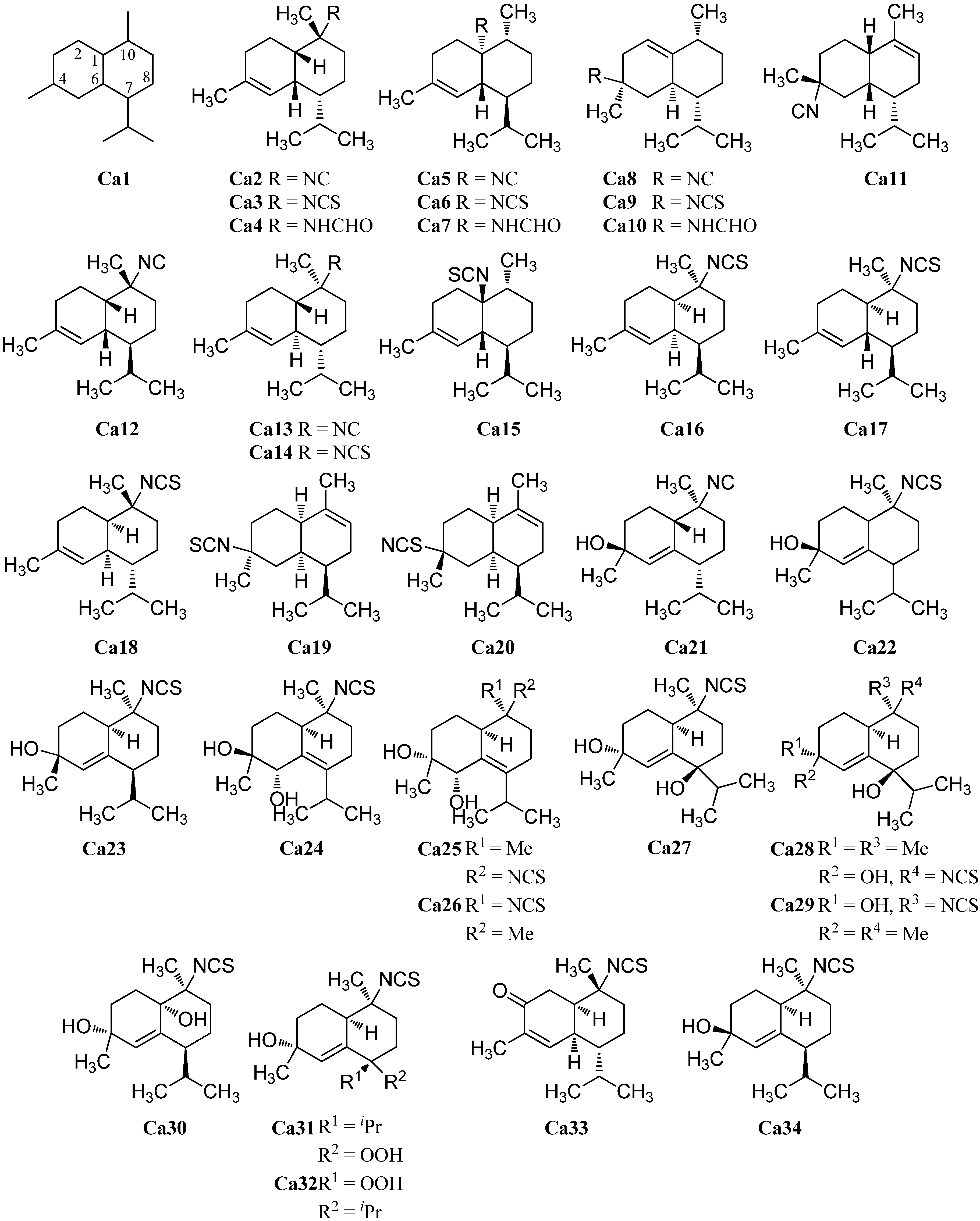

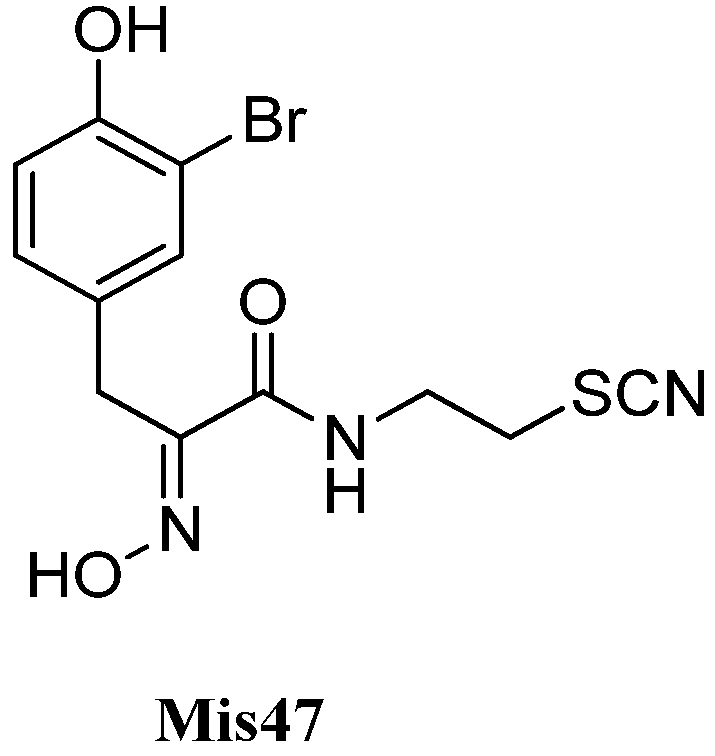

Sesquiterpenoids constitute the largest subgroup of the marine isonitriles and their related compounds (–NCS, –NHCHO, –SCN, –NCO, –N=CCl2) which in combination could be termed “isonitriloids” due to their close biogenetic relationship with the flagship isonitriles. Most of the isonitriles of this class have the molecular formula C15H25NC but they can be subdivided into nine groups based on the type of their molecular skeleton (Figure 2). To date, over 190 sesquiterpenes bearing one of the above-mentioned nitrogenous functions are known, among them are nine axanes (Ax2–Ax10), 32 eudesmanes (Eu2–Eu33), 33 cadinanes/amorphanes (Ca2–Ca34), 19 spiroaxanes (Sp2–Sp20), 14 aromadendranes (Ar2–Ar16), eight epimaalianes (Ep2–Ep9), 14 pupukeananes (Pu2–Pu15), 35 bisabolanes (Bi2–Bi36), nine guaianes (Gu2–Gu10) and 17 further sesquiterpenoids (Fu1–Fu17).

Figure 2.

Skeletal-types of sesquiterpenoids (arrows indicate potential attachment points of the nitrogenous function).

Figure 2.

Skeletal-types of sesquiterpenoids (arrows indicate potential attachment points of the nitrogenous function).

2.1.1. Axanes

As already mentioned in the introduction, the first marine isonitrile, axisonitrile-1 (Ax2), was isolated by Cafieri et al. from the marine sponge Axinella cannabina, collected in the Bay of Taranto (Italy), along with the corresponding axisothiocyanate-1 (Ax3), in 1973 (Figure 3) [2]. The name is based on the genus of the marine sponge, Axinella cannabina, and the functional group “isonitrile” or “isothiocyanate”, respectively. The corresponding formamido compound axamide-1 (Ax4) was isolated by the same group one year later [5]. Further examination of the extracts of Axinella cannabina led to some minor sesquiterpenoids, which could be identified as axisonitrile-4 (Ax5), axisothiocyanate-4 (Ax6) and axamide-4 (Ax7) [16]. The absolute configuration of axisonitrile-1 (Ax2), axisonitrile-4 (Ax5) and their related compounds was determined by X-ray crystallography and by CD-spectroscopy [17] but the configuration at C-10 was initially incorrectly assigned and had to be revised later [18].

Cavernoisonitrile (Ax8), (−)-cavernothiocyanate (Ax10) and 10-isothiocyanato-11-axene (Ax9) were isolated from the marine sponge Acanthella cavernosa and the nudibranch Phyllidia ocellata, collected at the Hachijo-jima Island (Japan) by Fusetani et al. [19,20].

Figure 3.

Axanes.

Figure 3.

Axanes.

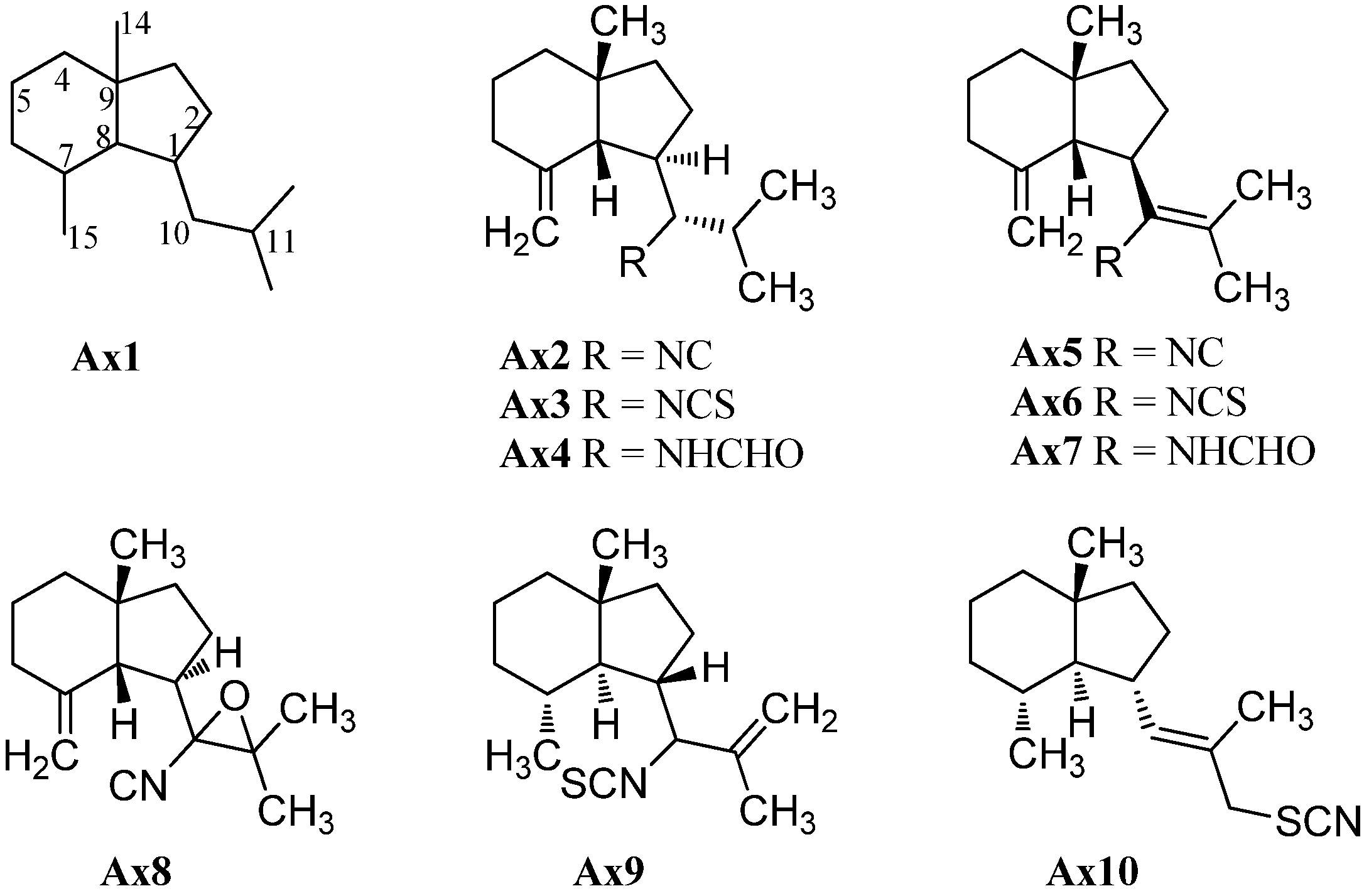

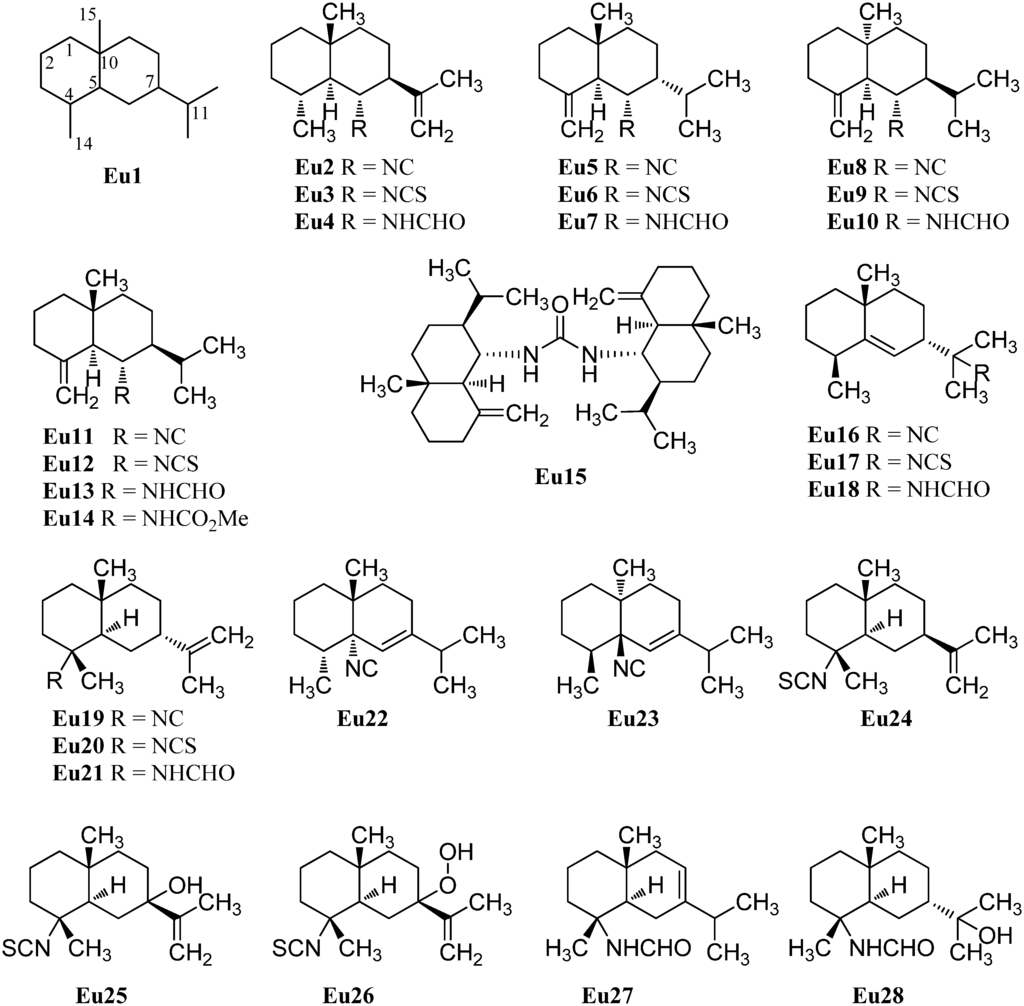

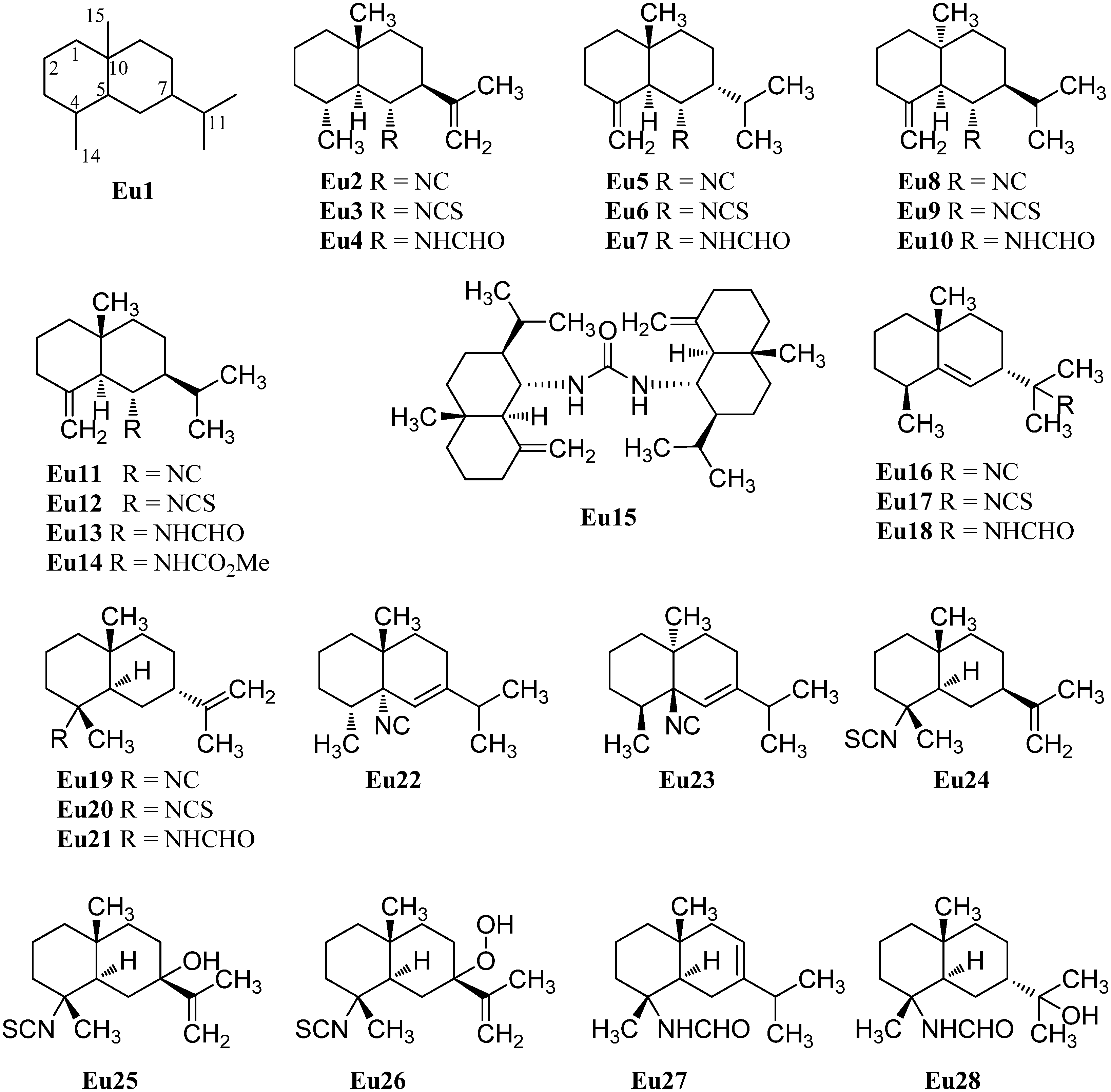

2.1.2. Eudesmanes

The first eudesmane-type isonitrile, acanthellin-1 (Eu2), was isolated from the sponge Acanthella acuta by Minale et al., collected in the Bay of Naples, Italy, in 1974 (Figure 4) [3]. The corresponding isothiocyanate Eu3 and formamide Eu4 were found together with acanthellin-1 (Eu2) ten years later by Ciminiello et al. in a sample of Axinella cannabina [21]. In the same sample, these authors also detected the isonitrile Eu5, the isothiocyanate Eu6 and the formamide Eu7 [21]. The same group also reported the isolation of the isonitrile Eu8, isothiocyanate Eu9 and the formamide Eu10 from the sponge Axinella cannabina [22]. Furthermore, the isonitrile Eu8 and the isothiocyanate Eu9 were isolated from Acanthella acuta [22].

Figure 4.

Eudesmanes.

Figure 4.

Eudesmanes.

In 1993, Burgoyne et al. reported the isolation of acanthene B (Eu12) from an Acanthella sponge and acanthene C (Eu13) from the nudibranch Cadlina luteomarginata but they were unable to isolate the parent isonitrile Eu11 [23]. However, this compound, halichonadin C (Eu11), was obtained from the sponge Halichondria sp. from Unten Port, Okinawa, Japan [24]. In this sample, Ishiyama et al. also found halichonadin B (Eu14) with a carbamate group and halichonadin A (Eu15), a dimer with two eudesmane skeletons bridged by a urea linkage [24].

The previous compounds all carry their nitrogenous function at C-6 but compounds with the function at C-4 and C-11 are also known. 11-Isocyano-7β-H-eudesm-5-ene (Eu16), the corresponding 11-isothiocyano-7β-H-eudesm-5-ene (Eu17), as well as 11-formamido-7β-H-eudesm-5-ene (Eu18) were isolated by Ciminiello et al. in 1987 from the sponge Axinella cannabina [25]. The compounds were also found in the Caribbean sponge Axinyssa ambrosia [26]. Moreover the isonitrile Eu16 was obtained from the nudibranch Phyllidiella pustulosa [27] and together with the isothiocyanato compound Eu17 from the sponge Acanthella sp. and the nudibranch Cadlina luteomarginata [23]. The isothiocyanato compound Eu17 is also one of several sesquiterpenoids isolated from the sponge Acanthella pulcherrima [28]. 11-Isothiocyano-7β-H-eudesm-5-ene (Eu17) did not show cytotoxity against cultured KB-3 cells (IC50 > 20 µg/mL) but moderate antimalarial activity against Plasmodium falciparum was observed (chloroquine-sensitive strain D6: IC50 = 2240 ng/mL, chloroquine-resistant strain W2: IC50 = 610 ng/mL) [29].

4-Isocyanatoeudesm-11-ene (Eu19) and 4-formamidoeudesm-11-ene (Eu21) have been isolated from the Caribbean sponge Axinyssa ambrosia [26]. The appropriate 4-isothiocyanatoeudesm-11-ene (Eu20) was found in the sponge Acanthella klethra [30] and later also in an unidentified sponge of the genus Acanthella, the nudibranch Cadlina luteomarginata [23], the sponge Acanthella cavernosa [31,32] and the sponge Axinyssa Isabela [33]. Similar to isothiocyanate Eu17, 4-isothiocyanatoeudesm-11-ene (Eu20) displayed a moderate antimalarial activity against Plasmodium falciparum (chloroquine-sensitive strain D6: IC50 = 4000 ng/mL, chloroquine-resistant strain W2: IC50 = 550 ng/mL) and no cytotoxic activity against KB-3 cells (IC50 > 20 µg/mL) [29].

Stylostelline (Eu22) ([α]D = +23° (CHCl3, c = 2)), isolated from the Stylotella sp. and collected in the Southeast of New-Caledonia [34], is one of only two marine isonitriloids with the nitrogenous function attached to C-5. The other known isonitrile is the corresponding enantiomer ent-stylotelline (Eu23) ([α]D = −47° (CHCl3, c = 1.7)) which was isolated from the nudibranch Phyllidiella pustulosa [35].

The isothiocyanate Eu24 is a C-7 epimer of compound Eu20 and was also isolated from the marine sponge Acanthella klethra [30]. The inversion of configuration at C-7 leads to a drastic reduction of the antimalarial activity against Plasmodium falciparum (chloroquine-sensitive strain D6: IC50 > 10 µg/mL, chloroquine-resistant strain W2: IC50 > 10 µg/mL) [29].

With only few exceptions, the nitrogenous function is the only heteroatom moiety in these secondary metabolites. However, Zubia et al. investigated the metabolites of the sponge of the genus Axynissa, collected in the Gulf of California (Mexico). In these samples, the hydroxylated axinisothiocyanate M (Eu25) and the hydroperoxide axinisothiocyanate N (Eu26) were identified [33].

In 2008, Lan et al. investigated extracts of the sponge Axinyssa sp., collected from the South Chinese Sea, and isolated the hitherto unknown formamides 4-formamidoeudesm-7-ene (Eu27) and the hydroxylated 4-formamidoeudesman-11-ol (Eu28) [36]. 4-Formamidoeudesm-7-ene (Eu27) exhibited significant cytotoxic activity against the human cancer cell lines CNE-2 (IC50 = 13.8 µg/mL), HeLa (IC50 = 7.5 µg/mL) and LO2 (IC50 = 38.0 µg/mL) [36].

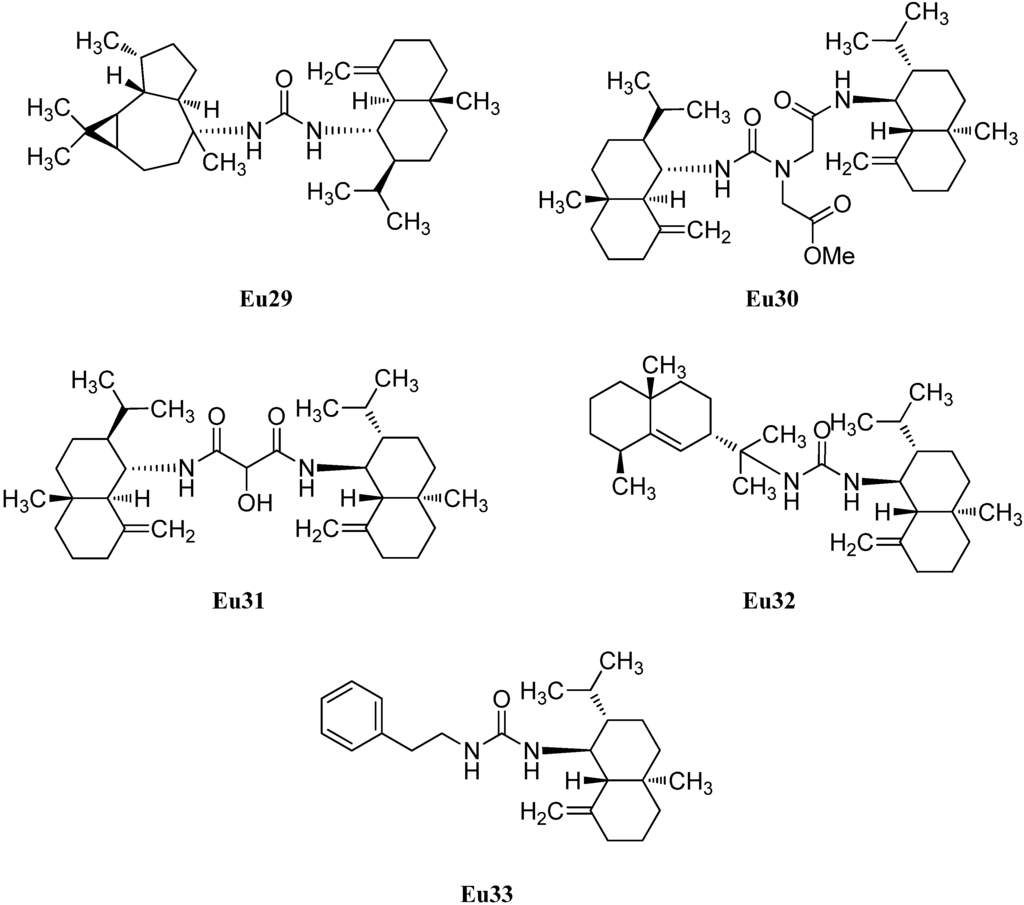

In addition to halichonadin A (Eu15), there are some other dimeric sesquiterpenoids with the eudesmane skeleton (Figure 5). Halichonadin E (Eu29) is an unsymmetrical dimer with one eudesmane and one aromadendrane (see Section 2.1.5) unit linked by a bridging urea moiety and was isolated from the Halichondria sp. by Kozawa et al. [37]. The same group isolated and identified the halichonadins G (Eu30), H (Eu31), I (Eu32) and J (Eu33) [38]. The halichonadins G–I are all dimeric sesquiterpenoids with two eudesmane skeletons with an 2-[1-(2-amino-2-oxoethyl)ureido]acetate linkage (Eu30), a 2-hydroxymalonamide linkage (Eu31) and an urea linkage (Eu32). Halichonadin J (Eu33) is a sesquiterpenoid with an eudesmane skeleton connected to 2-phenethylamine through a urea bridge.

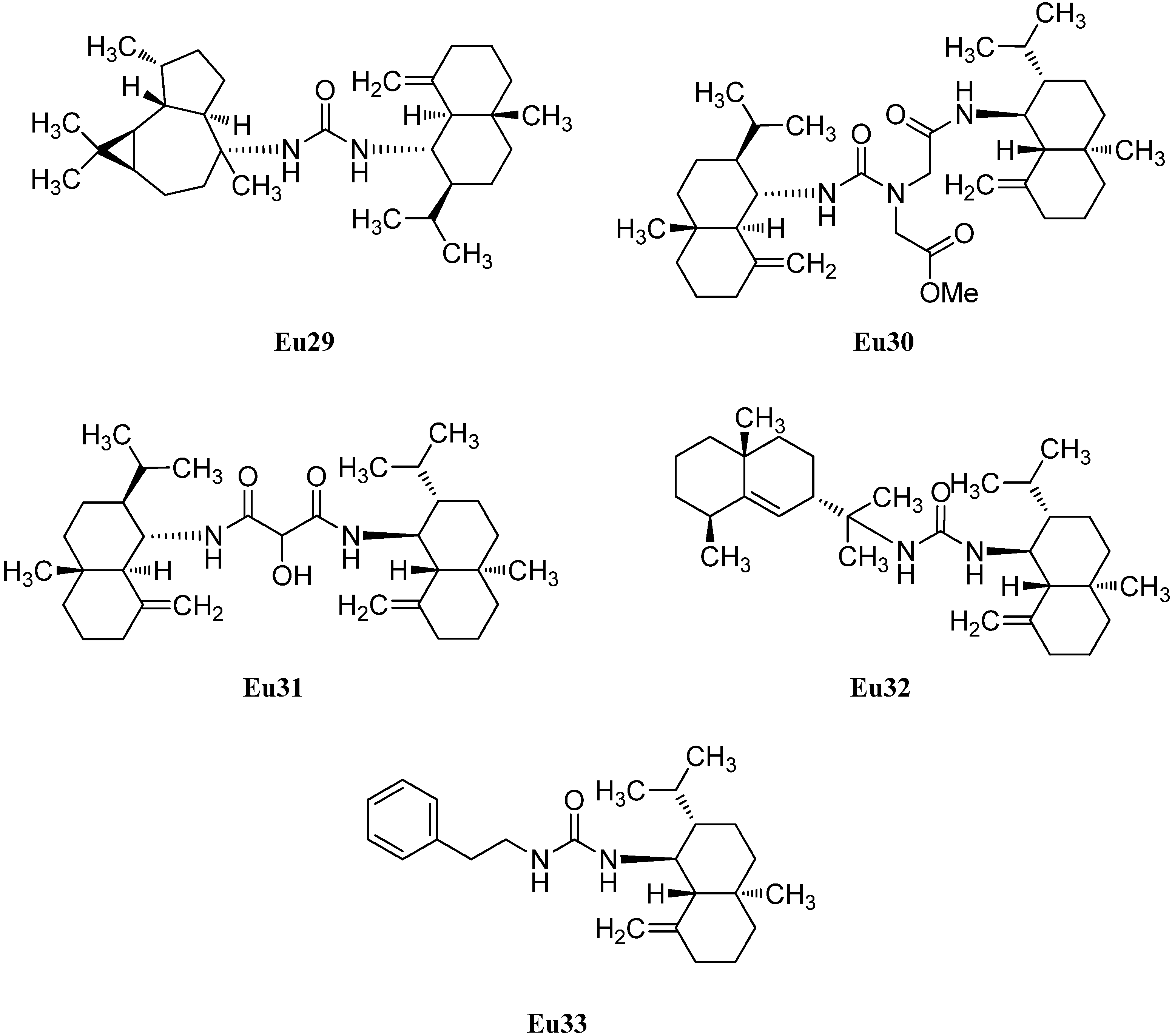

2.1.3. Cadinanes

The first cadinane- or amorphane-type isonitrile Ca2 was isolated along with the corresponding 10-isothiocyanato-4-amorphene (Ca3) and 10-formamido-4-amorphene (Ca4) from the sponge Halichondria sp. by Burreson et al. in 1975 (Figure 6). [6,39,40].

10-Isothiocyanato-4-amorphene (Ca3) displayed a weak antiplasmodial activity against Plasmodium falciparum (strains K1 and NF54, IC50 = 5.7 µM) [41]. Furthermore, 10-isocyano-4-amorphene (Ca2, IC50 = 7.2 µg/mL) and 10-isothiocyanato-4-amorphene (Ca3, IC50 = 0.70 µg/mL) showed potent antifouling activity against larvae of the acorn barnacle Balanus amphitrite [42]. Later, the isonitrile Ca2 was isolated from a sponge of the genus Axinyssa [43] and along with the isothiocyanate Ca3 from nudibranchs of the genus Phyllidiidae [42].

Figure 5.

Dimeric sesquiterpenoids with eudesmane skeleton.

Figure 5.

Dimeric sesquiterpenoids with eudesmane skeleton.

Further investigation by Ciminiello et al. of extracts from the sponge Axinella cannabina led to the identification of minor metabolites isonitrile Ca5, isothiocyanate Ca6 and the formamide Ca7 [44]. The isothiocyanate compound halipanicine (Ca9) was found by Nakamura et al. in the sponge Halichondria panacea, collected from Okinawan Island, Japan [45]. The corresponding isonitrile Ca8 and formamide Ca10 were absent in this sponge and were isolated later from the sponge Axinyssa aplysinoides from Palau [46].

There are numerous cadinanes for which the complete isonitriloid triples of isonitrile, isothiocyanate, and formamide have not yet been found but where only one of the isonitriloid species is known. The isonitrile 4α-isocyano-9-amorphene (Ca11) was isolated by Fusetani et al. from specimens of the nudibranch Phyllidia pustulosa, which were collected off Hachijo-jima Island, Japan [47]. The same team isolated the isonitrile 10α-isocyano-4-amorphene (Ca12) from the sponge Acanthella cf. cavernosa and the nudibranch Phyllidia ocellata [19]. 10-Isocyano-4-cadinene (Ca13) was isolated by Okino et al. from the nudibranch Phyllidia pustulosa from Kamikoshiki-jima Island, Japan, in 1996 [42]. This isonitrile also displayed potent antifouling activity against larvae of the acorn barnacle Balanus amphitrite (IC50 = 0.14 µg/mL) [42]. Four years later, the corresponding 10-isothiocyanato-4-cadinene (Ca14) was isolated from the tropical marine sponge Acanthella cavernosa [31]. Its absolute configuration was elucidated by enantioselective synthesis of both optical antipodes [48]. The isothiocyanate Ca15, a C-1 epimer of isothiocyanate Ca6, was isolated from a specimen of the sponge Acanthella pulcherrima, collected off Weed Reef, Darwin, Australia [28]. The isothiocyanate (1R,6S,7S,10S)-10-isothiocyanato-4-amorphene (Ca16) ([α]D = +100° (CCl4, c = 5.5)), the enantiomer of Ca3 ([α]D = –63° (CCl4, c = 7.4)), was isolated from the sponges Axinella fenestratus, Topsentia sp. and Acanthella cavernosa [49]. Mitome et al. reported the isolation of (1R*,6R*,7S*,10S*)-10-isothiocyanatocadin-4-ene (Ca17) from the Okinawan marine sponge Stylissa sp. [50]. Axinisothiocyanate K (Ca18) was isolated by Zubia et al. from a sponge of the genus Axinyssa, collected in the Gulf of California in 2008 [51]. (1R*,4S*,6R*,7S*)-4-Isothiocyanato-9-amorphene (Ca19) was obtained from the Fijian sponge Axinyssa fenestratus and the Thailand sponges Topsentia sp. and Acanthella cavernosa [49].

Figure 6.

Cadinanes.

Figure 6.

Cadinanes.

He et al. isolated in 1989 the unusual and first marine thiocyanate Ca20 [52]. The relative stereochemistry of (1S*,4S*,6S*,7R*)-4-thiocyanato-9-cadinene (Ca20) was determined by X-ray analysis [52]. The biogenetic relation of the thiocyanates to the classical isonitriloids remains unclear.

As for the eudesmanes (see Section 2.1.2), several hydroxylated and hydroperoxide-funtionalized cadinane sesquiterpenoids are known. The first isolated hydroxylated cadinane-type sesquiterpenoid was (1S*,4S*,7R*,10S*)-10-isocyano-5-cadinen-4-ol (Ca21), isolated from the nudibranch Phyllidia pustulosa [53] while the closely related 10-isothiocyanatoamorph-5-en-4-ol (Ca22) was obtained from the sponges Axinella fenestratus, Topsentia sp. and Acanthella cavernosa [49]. (1S*,4S*,7R*,10S*)-10-Isocyano-5-cadinen-4-ol (Ca21) showed antifouling activity against larvae of the barnacle Balanus amphitrite (EC50 = 0.17 µg/mL) [53].

In 2008, Zubia et al. investigated specimens of the marine sponge Axinyssa sp. and were able to isolate as many as twelve new cadinane-type sesquiterpenoids, the axinisothiocyanates A–L [51]. For the non-oxygenated axinisothiocyanate K (Ca18), vide supra. Axinisothiocyanate J (Ca23) carries a hydroxy group at C-4. In contrast, axinisothiocyanates A (Ca24), B (Ca25) and C (Ca26) have two hydroxy groups at C-4 and C-5 and differ in their relative configuration. The same applies to axinisothiocyanate D (Ca27), axinisothiocyanate E (Ca28) and axinisothiocyanate F (Ca29) with the hydroxy groups at C-4 and C-7.

Another dihydroxylated isonitriloid, this time oxygenated at C-4 and at C-1, is axinisothiocyanate G (Ca30). Furthermore, two isothiocyanates with one hydroxy group at C-4 and one hydroperoxy group at C-1, axinisothiocyanates H (Ca31) and I (Ca32) were isolated from the same source. The last member of the series, axinisothiocyanate L (Ca33), is characterized by a keto group at C-3.

Axiplyn C (Ca34) was isolated from the sponge Axinyssa aplysinoides, collected at Misali Island, Tanzania [54].

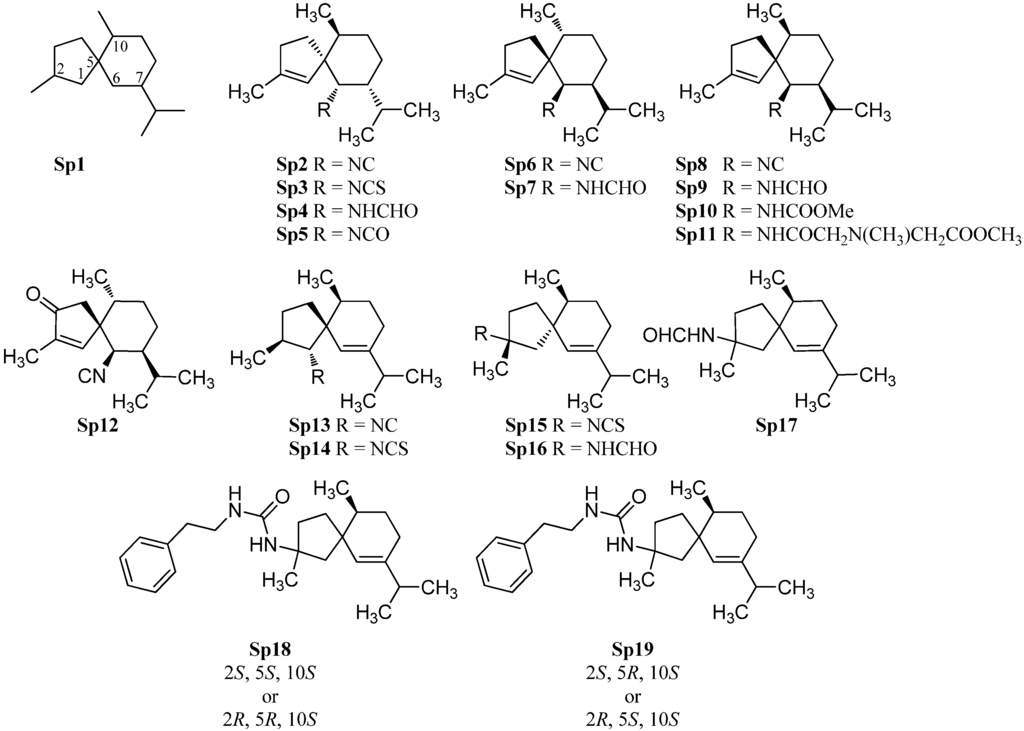

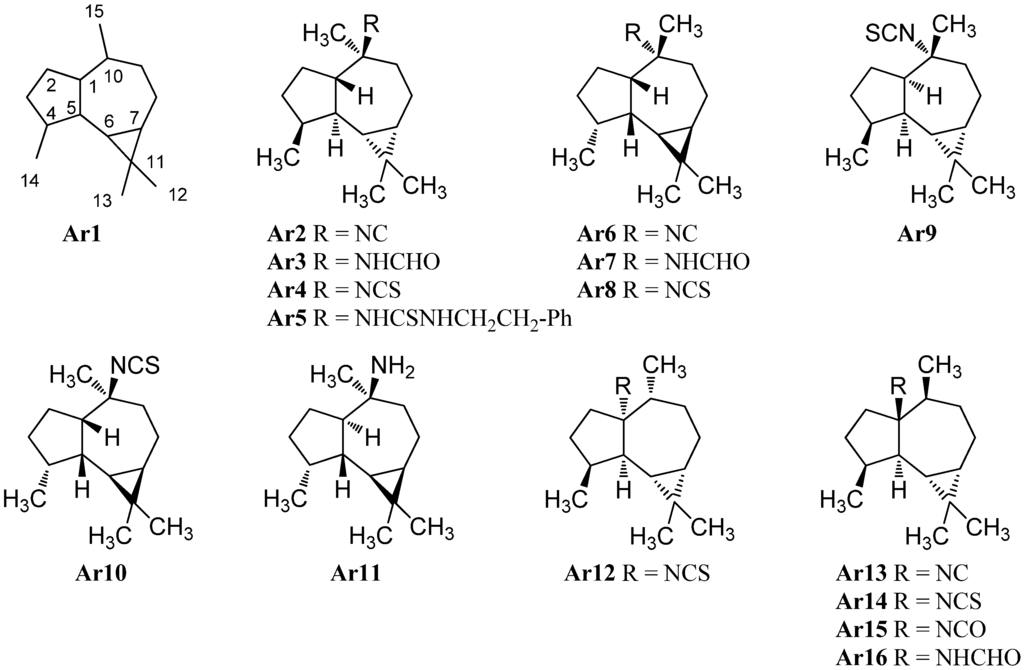

2.1.4. Spiroaxane

Di Blasio et al. isolated in 1976 the first spiroaxane-type isonitrile (+)-axisonitrile-3 (Sp2) ([α]D = +68.4° (CHCl3, c = 1) along with (+)-axisothiocyanate-3 (Sp3) ([α]D = +165.2° (CHCl3, c = 1)) and (−)-axamide-3 (Sp4) ([α]D = −6.86° (CHCl3, c = 1)) from the marine sponge Axinella cannabina (Figure 7) [55]. Their relative configuration was determined by X-ray crystallography while their absolute stereochemistry was determined by total synthesis of the enantiomeric (−)-axisontrile-3 (Sp6), the absolute configuration of which proved to be (5S,6R,7S,10R) [56]. The three compounds were also isolated from other sponges like Acanthella acuta [57], Acanthella cavernosa[19] and the nudibranchs Phyllidia ocellata [19] and Phyllidia pustulosa [42], (+)-axisonitrile-3 (Sp2) exhibited strong antimalarial activity against Plasmodium falciparum (chloroquine-sensitive strain D6: IC50 = 142 ng/mL, chloroquine-resistant strain W2: IC50 = 16.5 ng/mL) without cytotoxic activity against KB-3 cells (IC50 > 20 µg/mL). The corresponding isothiocyanate Sp3 is 500-fold less active than the isonitrile Sp2 (strain D6: IC50 = 12,340 ng/mL, strain W2: IC50 = 3,110 ng/mL) [29].

In extracts of the sponge Acanthella cavernosa was also found one of the few known marine isocyanates, axisocyanate-3 (Sp5) [58]. The enantiomeric (−)-axisonitrile-3 (Sp6) ( = −79° (CHCl3, c = 1.93)) and (+)-axamide (Sp7) ( = +17.5° (CHCl3, c = 3.05)) were obtained from the sponge Halichondria sp., collected off Phi Phi Island in the Andaman Sea, Southern Thailand [59].

10-epi-Axisonitrile-3 (Sp8), a C-10 epimer of axisonitrile-3 (Sp6), has been isolated from the nudibranch Phyllidia pustulosa [42]. Both isonitriles exhibited potent antifouling activity against larvae of the acorn barnacle Balanus amphitrite (Sp6: IC50 = 3.2 µg/mL, Sp8: IC50 = 10 µg/mL) [42]. Together with the known isonitrile Sp8, exiguamide (Sp9), exicarbamate (Sp10) and exigurin (Sp11) were isolated from the sponge Geodia exigua [60]. 3-Oxoaxisonitrile-3 (Sp12) was obtained from an unidentified Chinese marine sponge of the genus Acanthella [61].

Figure 7.

Spiroaxanes.

Figure 7.

Spiroaxanes.

In contrast to the above-mentioned spiroaxanes Sp2–Sp12, the isonitrile Sp13 and the isothiocyanate Sp14 both carry the nitrogenous functional group at C-1. Both spiroaxanes were isolated from the marine sponge Acanthella acuta [62].

(2R,5R,10S)-2-Isothiocyanato-6-axene (Sp15) and (2R,5R,10S)-2-formamido-6-axene (Sp16) with the functional group at C-2 were isolated by He et al. from the Palauan sponge Trachyopsis aplysinoides [52]. However, they identified the relative configuration of the both compounds as (2R,5R,10R) with a stereochemistry at C-10 unusual for natural products. Wegerski et al. revised the configuration from (2R,5R,10R)- to (2R,5R,10S)-2-isothiocyanato-6-axene (Sp15) and (2R,5R,10S)-2-formamido-6-axene (Sp16) [63]. During their investigations, the group also found the isothiocyanate Sp17 with (2S,5R,10S)- or (2R,5S,10S)-configuration [63]. Furthermore they found in analogy to halichonadin J (Eu30), vide supra the compounds N-phenethyl-2-formamido-6-axene (Sp18) with either (2S,5S,10S) or (2R,5R,10S) configuration and N-phenethyl-2-formamido-6-axene (Sp19) with either (2S,5R,10S) or (2R,5S,10S) configuration [63].

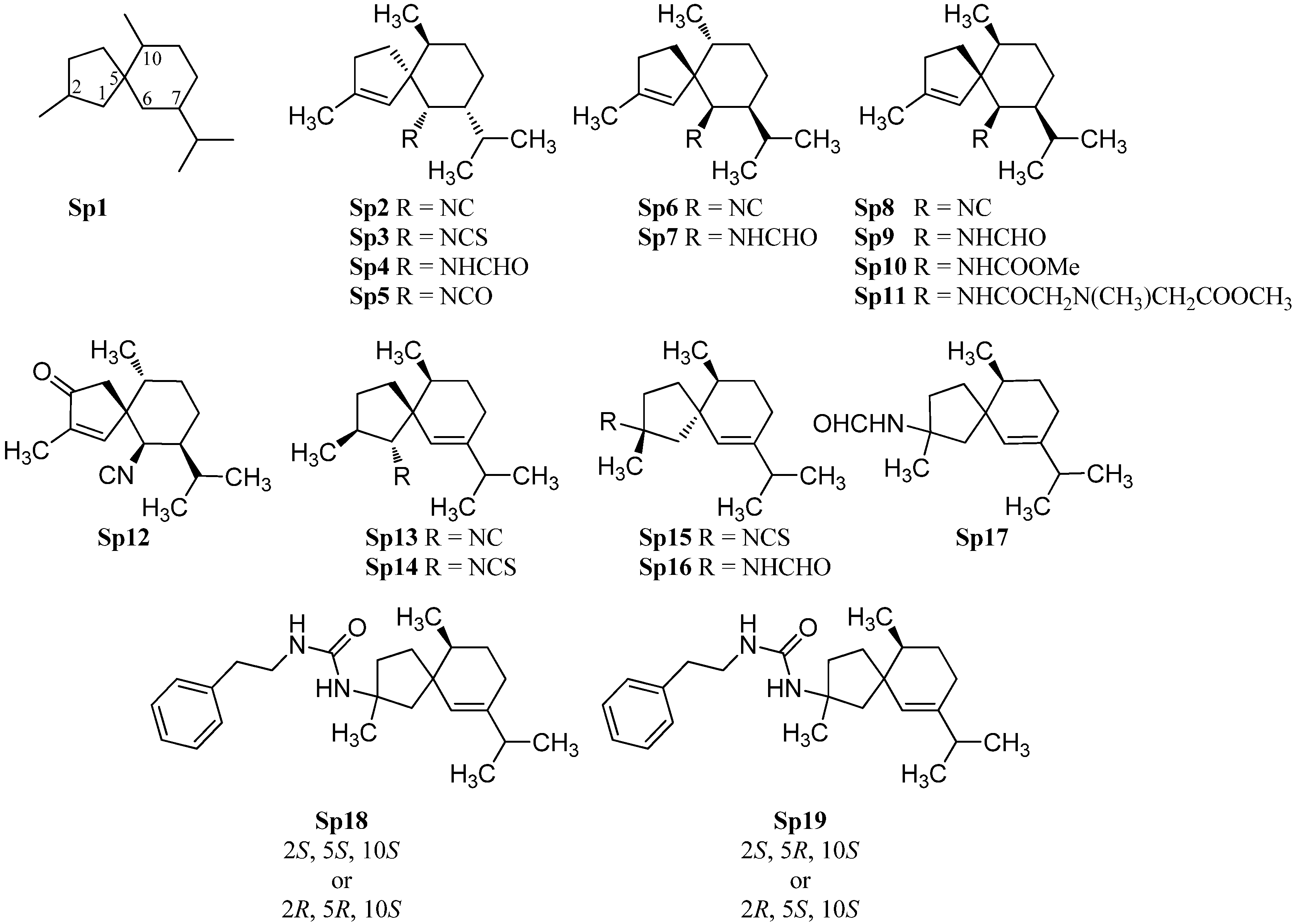

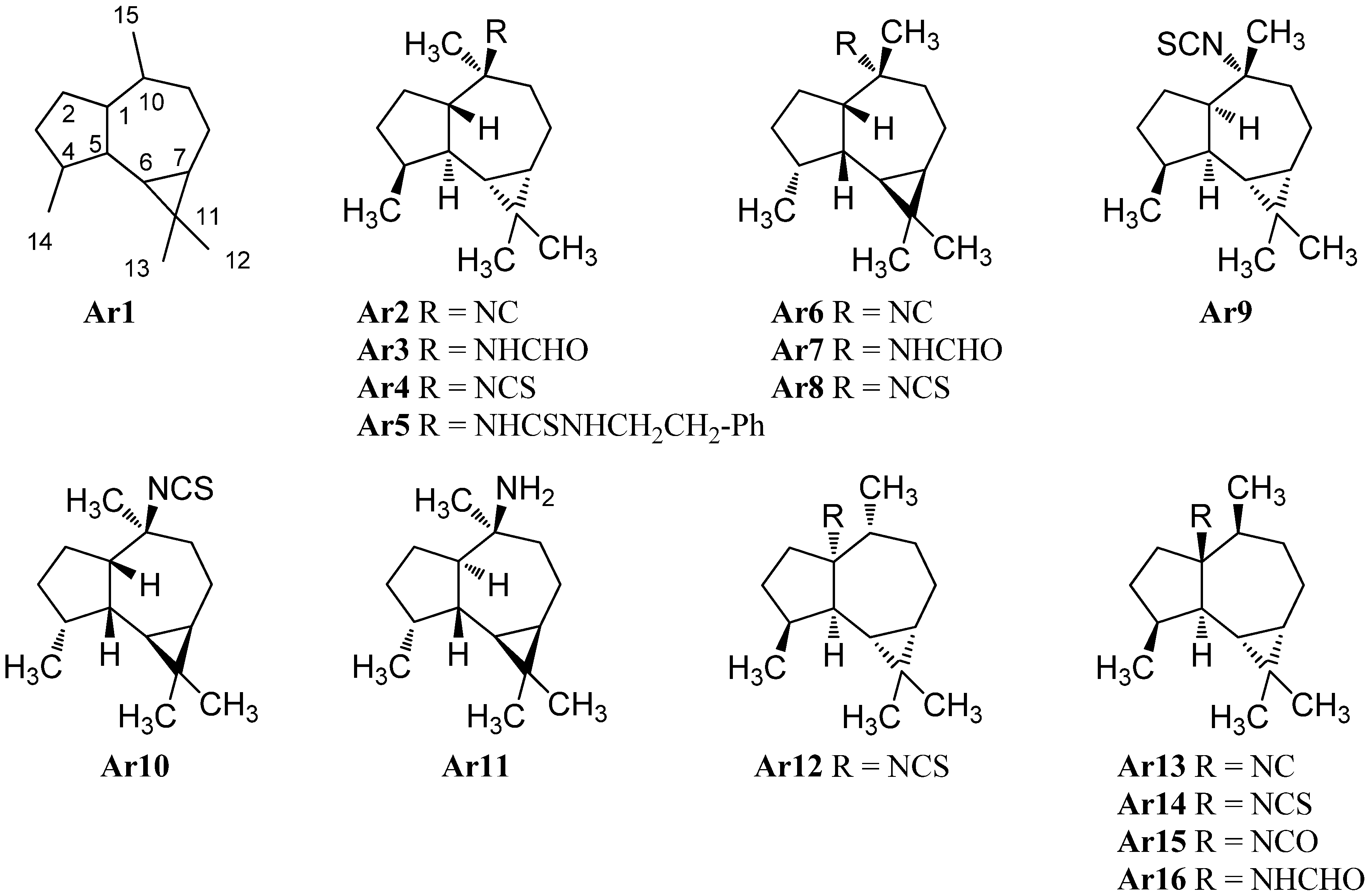

2.1.5. Aromadendranes

Another type of sesquiterpene isonitriles is based on the aromadendrane-skeleton (Ar1) (Figure 8). The first example of this class was isolated directly in the early days of the discovery of marine isonitriles shortly after axisonitrile-1 (Ax2). It was found in the Mediterranean sponge Axinella cannabina collected in the bay of Taranto, Italy by Fattorusso et al. in 1974 and was named axisonitrile-2 (Ar2) [4,5]. Its relative stereochemistry was elucidated by Ciminiello twelve years later [25]. Together with axisonitrile-2 (Ar2), Fattorusso et al. were also able to isolate the corresponding formamide axamide-2 (Ar3) and the isothiocyanate congener axisothiocyanate-2 (Ar4) from the same source[5]. Axisonitrile-2 (Ar2) was later also found by Hirota in the sponge Acanthella cavernosa [47]. In 1985 Tada reported the isolation of the isothiocyanate epipolasin B (Ar4) ([α]D = + 91.2 (CHCl3, c = 1.0)) and its β-phenylethylamine adduct epipolasinthiourea-B (Ar5) in extracts of Epipolasis kushimotoensis [64]. Epipolasin B has the same 2D-structure as axisothiocyanate-2 (Ar4), however, based on differences in the optical rotation compared to Fattorusso’s compound Ar4 ([α]D = + 12.8 (CHCl3, c = 1.5)), Tada proposed that both substances differ in stereochemistry. Chemical synthesis of both isothiocyanate enantiomers by da Silva makes a contamination of Fattorusso’s compound likely which may have caused a wrong optical rotation and suggests both isolated substances to be in fact identical [65]. Epipolasinthiourea-B (Ar5) showed moderate cytotoxic activities against the murine L1210 leukemia cell line (ED50 = 3.7 µg/mL) [64].

Examination of Acanthella cannabina collected off the coast of Taranto near Porto Cesareo (Italy) by Ciminiello et al. in 1987 resulted in the isolation of 10α-isocyanoalloaromadendrane (Ar6), 10α-formamidoalloaromadendrane (Ar7) and 10α-isothiocyanatoalloaromadendrane (Ar8), an isonitriloid triad showing a C1-epimeric alloaromadendrane-skeleton compared to Ar2, Ar3 and Ar4 [25].

An isothiocyanate with an opposite stereochemistry with the exception of C-10, (1R,4S,5S,6R,7S,10R)-(+)-isothiocyanatoalloaromadendrane (Ar9), was found in 1996 by Hirota et al. in an Acanthella cavernosa from Hachijo-jima Island (Japan) [20]. The absolute configuration was elucidated by comparison with the corresponding alcohols synthesized from (−)-alloaromadendrene. The compound was isolated again in 2010 by Lyakhova et al. from the Vietnamese nudibranch Phylidiella pustulosa [27]. The enantiomer Ar10 of this compound was prepared synthetically in 1994 by da Silva et al. and allowed the determination of the absolute configuration [65]. Ar9 and axisothiocyanate-2 (Ar4) were found to display potent antifouling activity against cyprid larvae of the acorn barnacle Balanus amphitrite [20].

Figure 8.

Aromadendranes.

Figure 8.

Aromadendranes.

Investigation of a Halichondria sp. collected near Unten Port (Okinawa, Japan) by Ishiyama et al. in 2008 led to the isolation of halochonadin F (Ar11), an amine epimeric at C-1 to da Silva’s compound . It was found to exhibit antimicrobial activity against Micrococcus luteus (MIC = 4 µg/mL), Trichophyton mentagrophytes (MIC 8 µg/mL) and Cryptococcus neoformans (MIC 16 µg/mL) [66].

In 1988, Breakman reported the isolation of an isonitrile, an isothiocyanate, and an isocyanate from the sponge Acanthella acuta (Banyuls, France) bearing the nitrogen functionality at C-1 instead of C-10 of the aromadendrane skeleton. Due to a misassigned reference substance, a wrong relative configuration was initially published [9,57], which was corrected two years later [67]. The first two compounds were found in parallel in an Acanthella acuta sponge collected in the Bay of Naples (Italy) by Mayol who elucidated the correct relative stereochemistry of Ar13 and Ar14 [62].

The formamide Ar16 was discovered in 2007 by Zhang et al. in the Spanish dancer nudibranch Hexabrandies sanguinens collected in the South China Sea [68]. The isolation of the corresponding isocyanate Ar15 was reported in 2007 by Jumaryatno from an Australian specimen of Acanthella cavernosa (Coral gardens, Gneerings reef, Mooloolaba) [32]. In 1992, He and Faulkner were able to identify the C1/C10-epimer Ar12 of isothiocyanate Ar14 in a sponge Axinyssa aplysinoides collected at Ant Atoll (Pohnpei/Micronesia) [69].

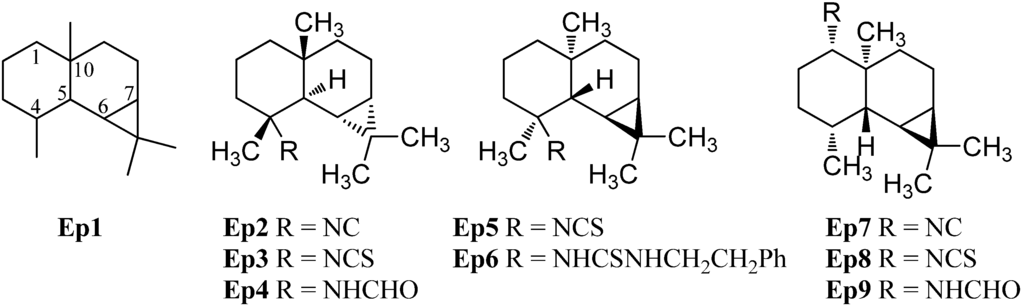

2.1.6. Epimaalianes

The epimaaliane sesquiterpenoids have a similar skeleton to the eudesmanes with a methyl group in C-4 and C-10 position but they possess an additional bond between C-6 and C-11, creating a cyclopropane ring (Ep1, Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Epimaalianes.

Figure 9.

Epimaalianes.

The first isolated epimaaliane-type sesquiterpenoids were the unnamed isonitrile Ep2 and (−)-epipolasin A (Ep3) ([α]D = −12° (CHCl3, c = 1.1)) isolated from the nudibranch Cadlina luteomarginata by Thompson et al. in 1982 [70]. Their relative stereochemistry was determined by X-ray crystallography of the formamide Ep4 which was obtained by hydrolysis of the isonitrile Ep2 [70]. Later, (−)-epipolasin A (Ep3) was isolated from the sponges Acanthella pulcherrima [28] and Axinyssa sp. nov. [71] and along with the isonitrile Ep2 and the formamide Ep4 from a Northeastern Pacific Acanthella sp. [23]. The isonitrile Ep2 and the formamide Ep4 were also isolated from skin extracts of the nudibranch Cadlina luteomarginata while the corresponding (−)-epipolasin A was not found in this organism [23]. (+)-Epipolasin A (Ep5) ([α]D = +7.6° (CHCl3, c = 1)) was found in the sponge Epipolasis kushimotoensis by Tada and Yasuda [64]. The absolute stereochemistry was deduced by correlation of ECD-spectra with those of the naturally occurring maaliol. The related isonitrile and formamide were not found while the thiourea compound Ep6 was isolated from the same producer [64]. (+)-Epipolasin A (Ep5) shows activity against Plasmodium falciparum strains D6 (IC50 = 5600 ng/mL) and W2 (IC50 = 5550 ng/mL) whithout exhibiting cytotoxic activity against KB cells (IC50 > 20 µg/mL) [71].

The isonitrile Ep7, the isothiocyanate Ep8 and the formamide Ep9 with the functional group attached to C-1 instead of C-4 were found during further investigations of extracts of the sponge Axinella cannabina by Ciminiello et al. [72].

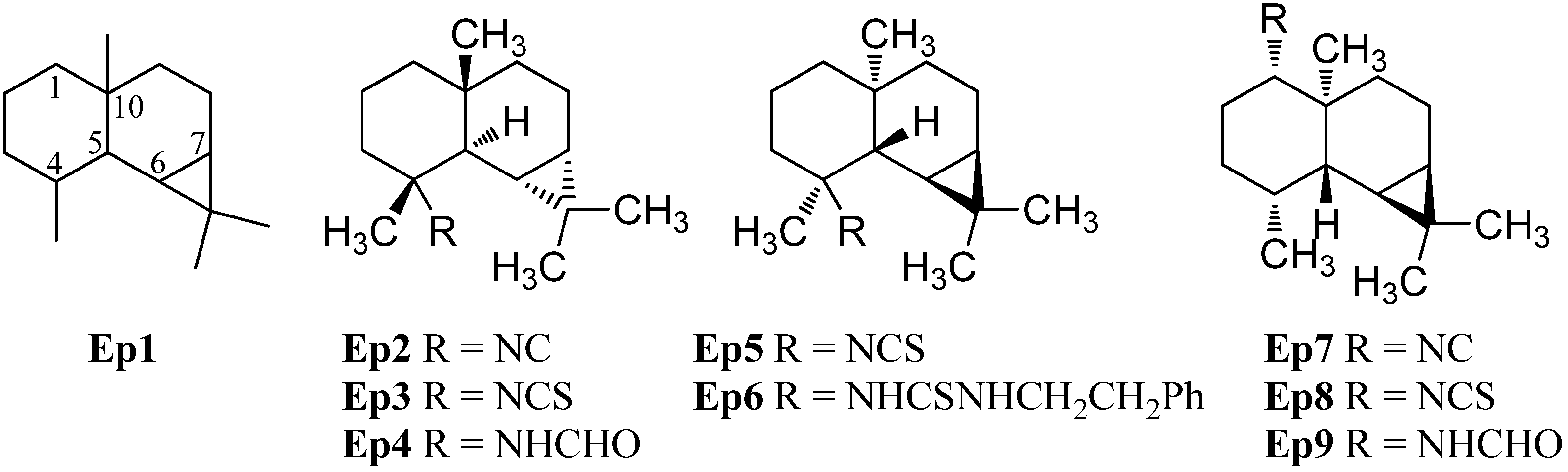

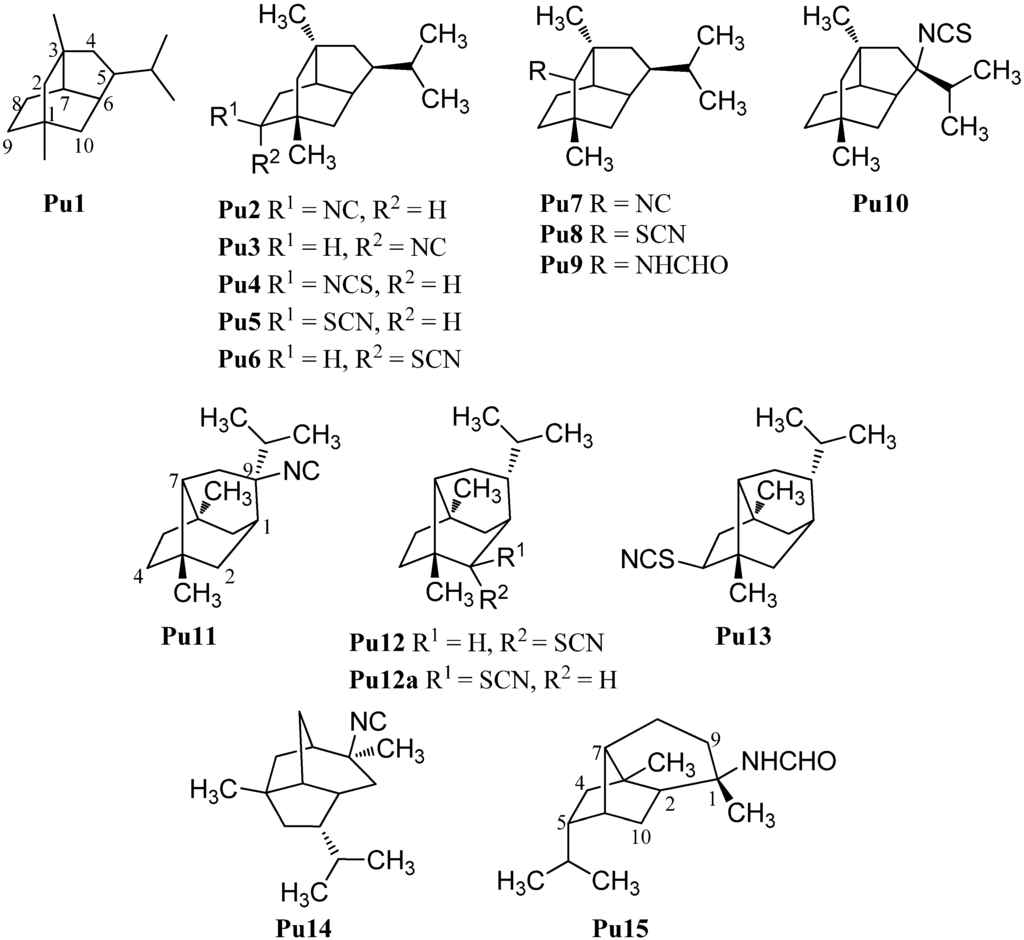

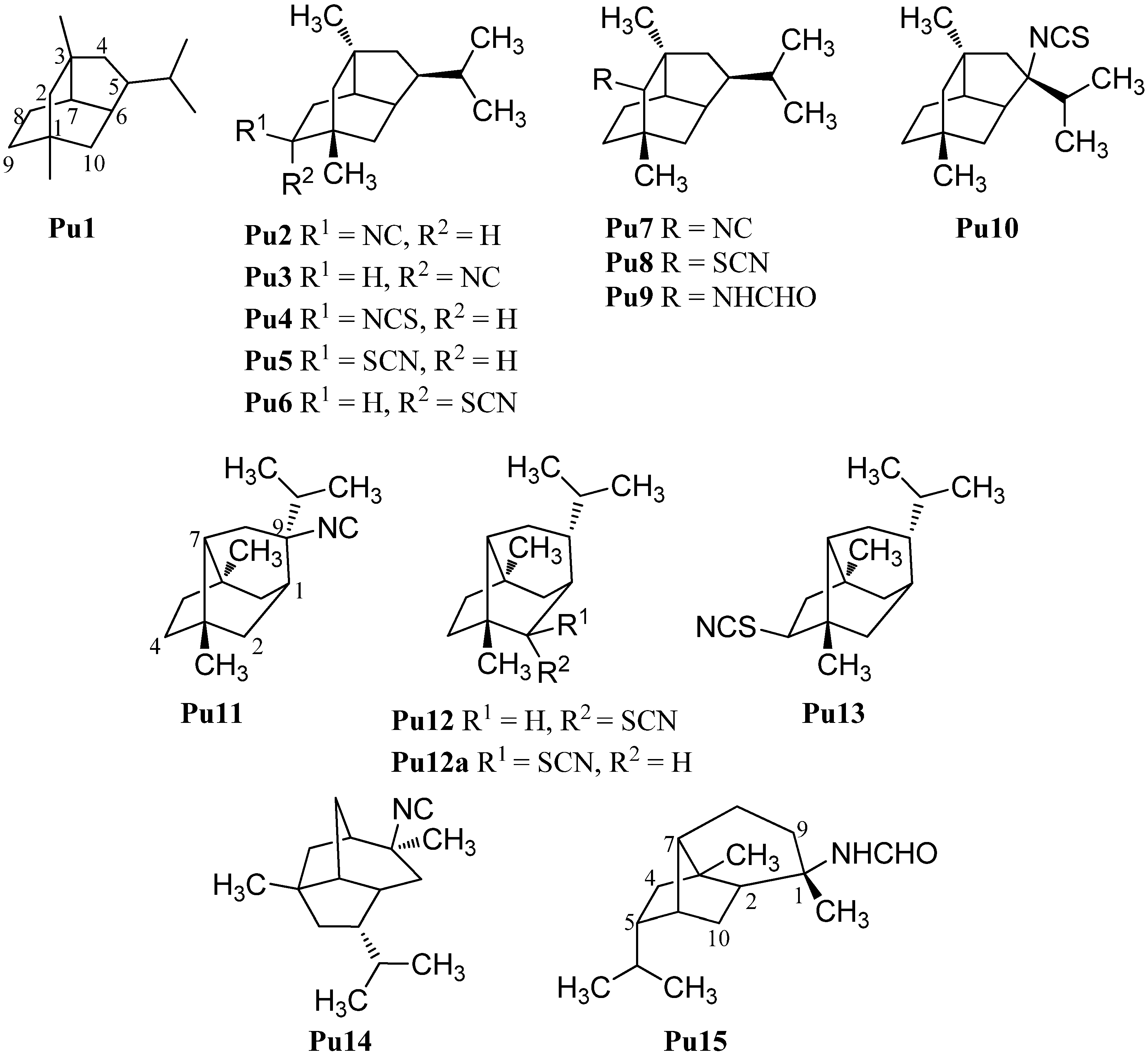

2.1.7. Pupukeananes

A further group of sesquiterpenoids are the pupukeananes which bear a tricyclo[4.3.1.03,7]decane skeleton (Pu1, Figure 10). The first isolated pupukeanane was 9-isocyanopupukeanane (Pu2) which was obtained from the nudibranch Phyllidia varicosa and an unidentified sponge of the genus Hymeniacidon by Burreson et al. in 1975 [73]. Later, Hymeniacidon sp. was reclassified as a Ciocalypta sp. [74]. The corresponding C-9 epimer 9-epi-isocyanopupukeanane (Pu3) was isolated from the nudibranch Phyllidia bourguini along with 9-isocyanopupukeanane (Pu2) [75]. Later, the corresponding 9-isothiocyanatopupukeanane (Pu4) was found in the sponge Axinyssa sp. nov., collected at the Great Barrier Reef, Australia [71]. 9-Isocyanopupukeanane (Pu2) displayed a weak antimalarial activity against Plasmodium falciparum (strain D6: IC50 = 2520 ng/mL, strain W2 IC50 = 1610) and showed no activity against KB cells (IC50 > 20 µg/mL). In contrast to isonitrile Sp2 and isothiocyanatate Sp3, the antimalarial activity of the corresponding isothiocyanate Pu4 was similar to isonitrile Pu2 (strain D6: IC50 = 3290 ng/mL, strain W2: IC50 = 890 ng/mL) [71].

Remarkably and in sharp contrast to the other sesquiterpenoid subgroups, numerous thiocyanates with a pupukeanane skeleton are known. 9-Thiocyanatopupukeanane (Pu5) and its C-9 epimer 9-epi-thiocyanatopupukeanane (Pu6) were isolated from the nudibranch Phyllidia varicosa and the sponge Axinyssa aculeata, collected from the coral reefs of Pramuka Island, Indonesia [76]. Both compounds Pu5 (IC50 = 4.6 µg/mL) and Pu6 (IC50 = 2.3 µg/mL) showed potent antifouling activity against larvae of the acorn barnacle Balanus amphitrite [42].

In addition to the C-9 functionalized pupukeananes, some C-2 and C-5 functionalized representatives of this class ar known as well. 2-Isocyanopupukeanane (Pu7) was obtained by Hagadone et al. from the nudibranch Phyllidia varicosa together with isonitrile Pu2 [77]. He et al. isolated the corresponding 2-thiocyanatopupukeanane (Pu8) from the sponge Axinyssa aplysinoides [69]. Recently the corresponding formamide Pu9 was isolated from Phyllidia coelestis Bergh, collected near the Koh-Ha Islets, Thailand [78].

Figure 10.

Pupukeananes.

Figure 10.

Pupukeananes.

Furthermore, one pupukeanane with an isothiocyanate group at C-5 (Pu10) was obtained by Marcus et al. from a sponge of the genus Axinyssa [43].

In addition, there are some rearranged pupukeananes like 9-isocyanoneopupukeanane (Pu11), which was obtained from the sponge Ciocalypta sp. collected in O’ahu, Hawaii [79]. 2-Thiocyanatoneopupukeanane (Pu12) was first isolated at 1991 by Pham et al. from an unidentified Phonpei sponge but they determined the configuration of the functional group at C-2 incorrectly (Pu12a) [80]. One year later He et al. also isolated the thiocyanato compound Pu12 from the sponge Axinyssa aplysinoides and revised the configuration at C-2 on the basis of NMR experiments [69]. 2-Thiocyanatoneopupukeanane (Pu12) showed a similar antimalarial activity against Plasmodium falciparum (strain D6: IC50 = 4700 ng/mL, strain W2: IC50 = 890 ng/mL) as 9-isocyanopupukeanane (Pu2) and 9-isothiocyanatopupukeanane (Pu4) [71]. 4-Thiocyanatoneopupukeanane (Pu13) was also isolated by Pham et al. from the sponge Phycopsis terpnis [80].

Apart from the pupukeananes (Pu2–Pu10) and the neopupukeananes (Pu11–Pu13), two other rearranged pupukeananes are known: 2-Isocyanoallopupukeanane (Pu14) was obtained from the nudibranch Phyllidia pustulosa by Fusetani et al. [47] and Jaisamut et al. isolated 1-formamido-10(1→ 2)-abeopupukeanane (Pu15) from the nudibranch Phyllidia coelestis Bergh [78].

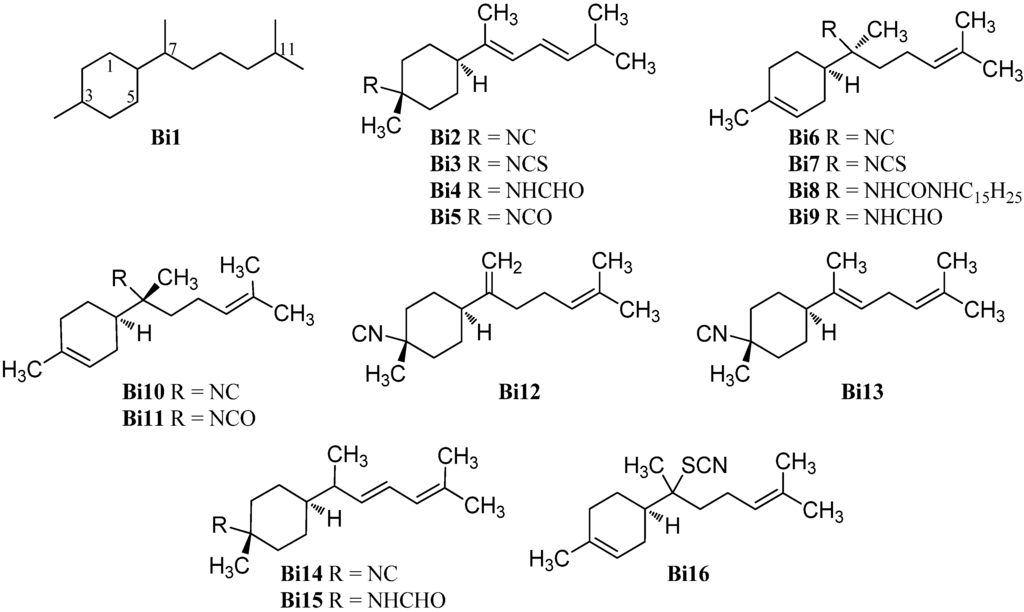

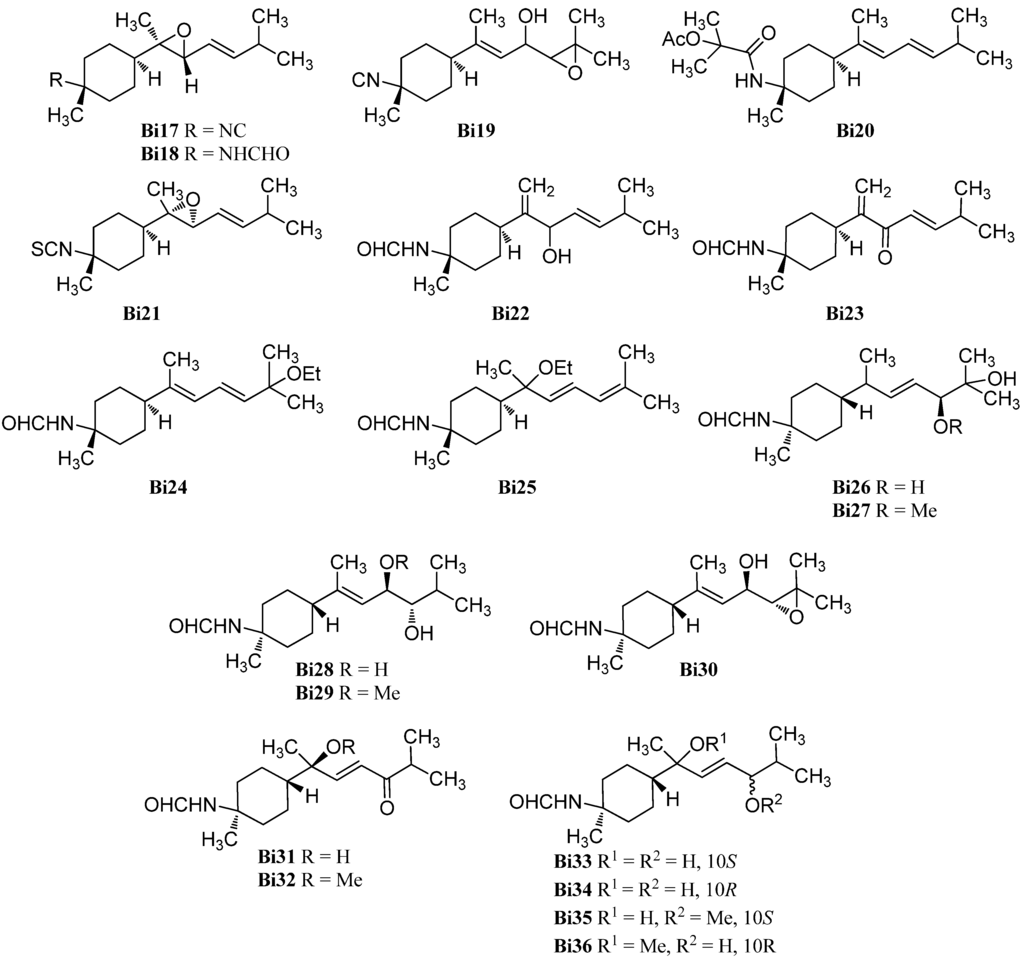

2.1.8. Bisabolanes

Bisabolane-type compounds have a 1-methyl-4-(6-methyl-2-heptanyl)cyclohexane skeleton (Bi1) and the functional group is either located at C-3 or at C-7 (Figure 11). The first isolated bisabolane compounds were 3-isothiocyanatotheonellin (Bi3) and 3-formamidotheonellin (Bi4) from the Okinawan sponge Theonella cf. swinhoei reported by Nakamura et al. in 1984 [81]. The analog 3-isocyanotheonellin (Bi2) was isolated two years later by Gulavita et al. from the nudibranch Phyllidia sp. [74]. 3-Isocyanotheonellin (Bi2) showed potent antifouling activity against larvae of the acorn barnacle Balanus amphitrite (IC50 = 0.13 µg/mL) [42]. In 2012 Wright et al. reported the isolation and characterization of 3-isocyanatotheonellin (Bi5) together with the known isonitrile Bi2, isothiocyanate Bi3 and 7-isothiocyanato-7,8-dihydro-α-bisabolene (Bi7) from the sponge Raphoxya sp., collected near Blue Hole, Guam [82].

Figure 11.

Bisabolanes.

Figure 11.

Bisabolanes.

The latter compound was also found in the sponge Halichondria sp. together with the urea derivate N,N′-bis((6R,7S)-7,8-dihydro-α-bisabolen-7-yl)urea (Bi8) in 1986 [83]. The related 7-isocyano-7,8-dihydro-α-bisabolene (Bi6) was isolated from the tropical marine sponge Acanthella cavernosa by Jumaryatno et al. in 2007 [32] and 7-formamido-7,8-dihydro-α-bisabolene (Bi9) was isolated from the Hainan marine sponge Axinyssa sp. by Li et al. in 2008 [84].

In 1986, Gulavita et al. also reported the isolation of 7-isocyano-7,8-dihydro-α-bisabolene (Bi10), the C-7 epimer of the isonitrile Bi6, and 7-isocyanato-7,8-dihydro-α-bisabolene (Bi11) from the sponge Ciocalypta sp. [74].

The isonitrile Bi12 with an exo-methylene group at C-7 was obtained from the nudibranch Phyllidiella pustulosa from the South China Sea [35]. (E)-4-Isocyanobisabolane-7,10-diene (Bi13) with two non-conjugated double bonds was isolated from an Okinawan sponge of the genus Axinyssa [85].

Kassuehlke et al. reported the isolation of 3-isocyanobisabolane-8,10-diene (Bi14) from the nudibranch Phyllidia pustulosa and the appropriate 3-formamidobisabolene-8,10-diene (Bi15) from the Paulauan sponge Halichondria cf. lendenfeldi. However, the full characterization of the formamide Bi15 was not possible due to decomposition [86].

The thiocyanate axinythiocyanate A (Bi16) was obtained from the sponge Axinyssa isabela, collected in the Gulf of California, Mexico [33].

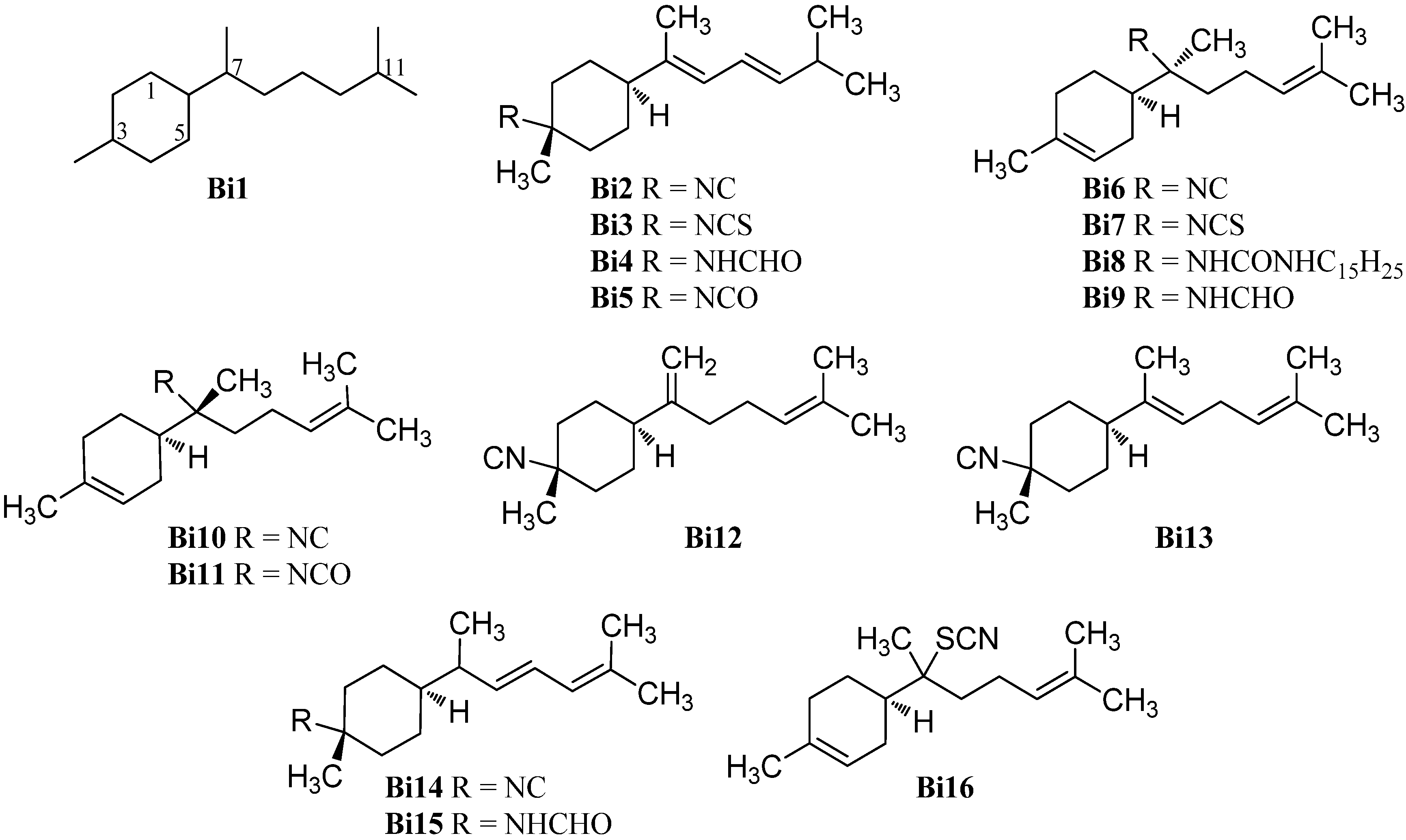

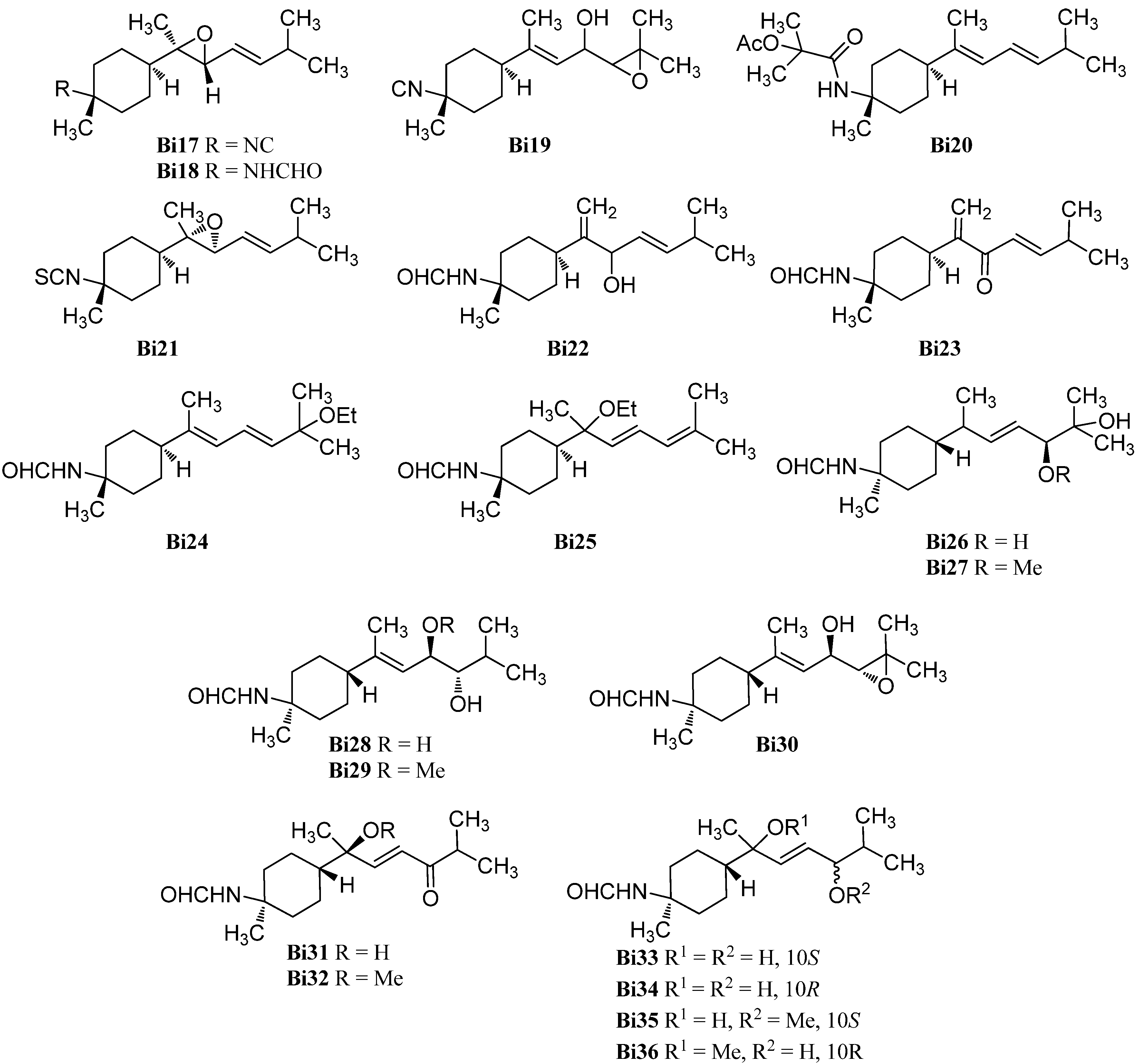

In the past 15 years, a considerable number of oxygenated bisabolanes were isolated and characterize, the majority of which being oxygenated formamides (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Oxygenated bisabolanes.

Figure 12.

Oxygenated bisabolanes.

Sun et al. reported the isolation of 3-isocyano-7,8-epoxy-α-bisabolane (Bi17) and the corresponding 3-formamido-7,8-epoxy-α-bisabolane (Bi18) from the Hainan sponge Axinyssa sp. [87]. Recently, axinysaline A (Bi20) and axinysaline B (Bi19) were found in an unidentified Formosan sponge of the genus Axinyssa by Liu et al. [88].

Previously, the only oxygenated isothiocyanato compound was 7α,8α-epoxy theonellin isothiocyanate (Bi21) which was isolated from Phycopsis sp. collected from the Mandapam coast in the Gulf of Mannar, Tamilnadu, India [89].

The first reported oxygenated bisabolanes were 3-formamidobisabolane-14(7),9-dien-8-ol (Bi22), 3-formamidobisabolane-14(7),9-dien-8-one (Bi23) and 3-formamido-8-methoxybisabolan-9-en-10-ol (Bi36). They were all isolated from a Micronesian sponge of the genus Axinyssa along with the known 3-formamidotheonellin (Bi3) [90].

Two uncommon bisabolanes with an ethoxy group at C-7 or C-11 respectively, 11-ethoxy-3-formamidotheonellin (Bi24) and 7-ethoxy-3-formamidobisabolane-8,10-diene (Bi25), were isolated from a Hainan sponge Axinyssa aff. variabilis by Mao et al. [91].

In 2014, Cheng et al. reported the isolation of ten oxygenated formamidobisabolanes (Bi26–Bi35) from a Chinese sponge (Axinyssa sp.) [92]. Axinyssine C (Bi26) has two hydroxy groups at C-10 and C-11 and a double bond in 8-position. Axinyssine D (Bi27) has the same structure as Bi26 but bears a methoxy group at C-10. Axinyssines E and F (Bi28 and Bi29) have the same functional groups as Bi26/Bi27 but the double bond is located at C-7, one hydroxy group is found at C-10 and the other hydroxy/methoxy group is attached to C-9. However, axinyssine G (Bi30) has one hydroxy group at C-9 and an epoxy group at C-10. NOE experiments revealed a 7E geometry and the coupling constant JH-9/H-10 = 8.0 Hz suggests a threo-orientation of the two stereocenters in the side chain. The absolute configuration of C-9 was determined by ECD spectra of the Rh2(OCOCF3)4 complex. Axinyssine H (Bi31) has a hydroxy group at C-7 and a keto group at C-10. Axinyssine I (Bi32) is the methoxylated analogue of Axinyssine H (Bi31). The compounds Bi33–Bi36 are the reduced compounds of axinyssine H (Bi31) and axinyssine I (Bi32). Axinyssine J (Bi33) has two hydroxy groups and the hydroxy-group-bearing C-10 has S-configuration. In contrast, axinyssine K (Bi34) has R-configuration at C-10. Axinyssine L (Bi35) carries a methoxy group at C-7 and a hydroxy group at the S-configured 10-position. The corresponding 3-formamido-8-methoxybisabolan-9-en-10-ol (Bi36) was isolated earlier [90].

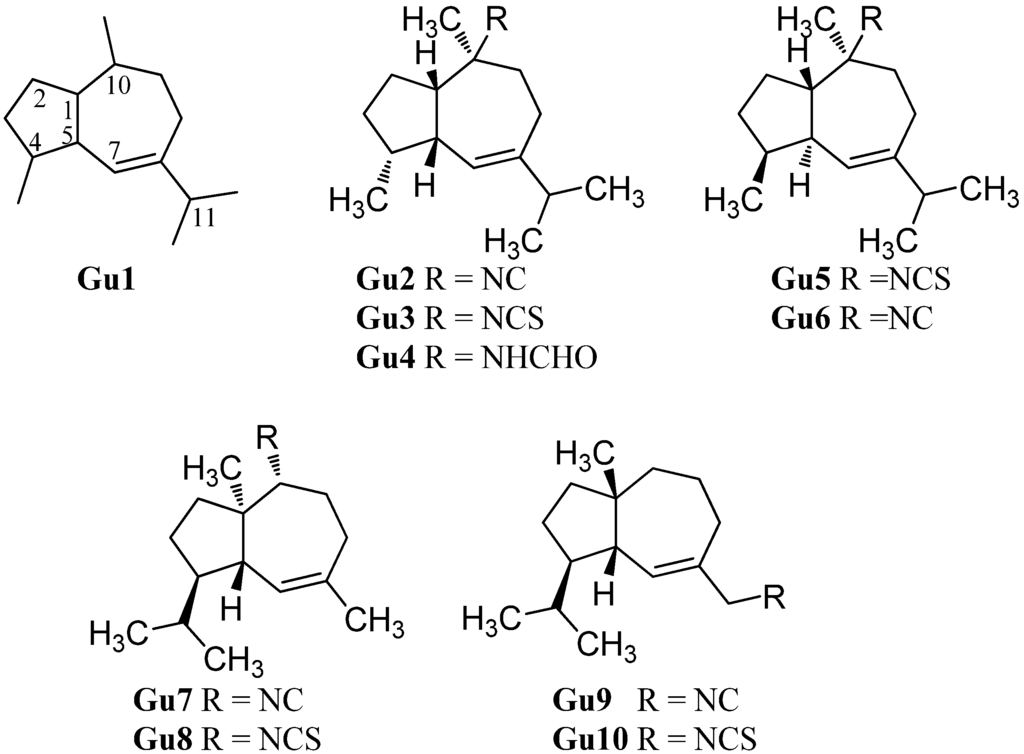

2.1.9. Guaianes

Guaiane-type sesquiterpenoids have a similar skeleton to the aromadendranes but are devoid of the cyclopropane ring (Gu1, Figure 13). Tada et al. reported the first isolation of guaiane isonitriloids in 1988. The isonitrile Gu2, the isothiocyanate Gu3 and the formamide Gu4 were obtained from an unidentified sponge [93]. However, the authors speculated that the formamide Gu4 was not produced by the sponge but rather was an isolation artifact originating from hydrolysis of Gu2 during column chromatography [93]. The isothiocyanate Gu3 was also isolated from the tropical marine sponge Acanthella cavernosa wich was followed by a more detailed characterization but the orientation of the isothiocyanato group could not be elucidated [32]. Tada et al. deduced the relative configuration of the other congeners based on X-ray crystallography of the isonitrile Gu2 [93].

Figure 13.

Guaianes.

Figure 13.

Guaianes.

(1S*,4S*,5R*,10S*)-10-Isothiocyanatoguaia-6-ene (Gu5) was isolated from the sponge Trachyopsis aplysinoides collected in Palau [52]. The corresponding isonitrile Gu6 was isolated in 2004 from the nudibranch Pthyllidiella pustulosa from the South Chinese Sea [35].

In 2008, Li et al. reported the isolation of 4,5-epi-10-isothiocyanatoisodauc-6-ene (Gu8) from the Hainan marine sponge Axinyssa sp. [84]. In contrast to the other guaianes (Gu2–Gu6), one of its methyl groups is not located at C-10 but at C-1 and the isopropyl group and the methyl group at C-8 and C-4 are interchanged. The corresponding isonitrile (Gu7) was obtained recently by Wright et al. from the nudibranch Phyllidia ocellata [94].

Another unusual isonitrile/isothiocyanate pair, Gu9/Gu10, was isolated in 1987 by Mayol et al. from the sponge Acanthella acuta [62]. Similar to the isonitrile Gu7 and the isothiocyanate Gu8, the methyl group is located at C-1 and the isopropyl group and the methyl group are interchanged but the nitrogenous functional group is attached to the exocyclic allylic carbon.

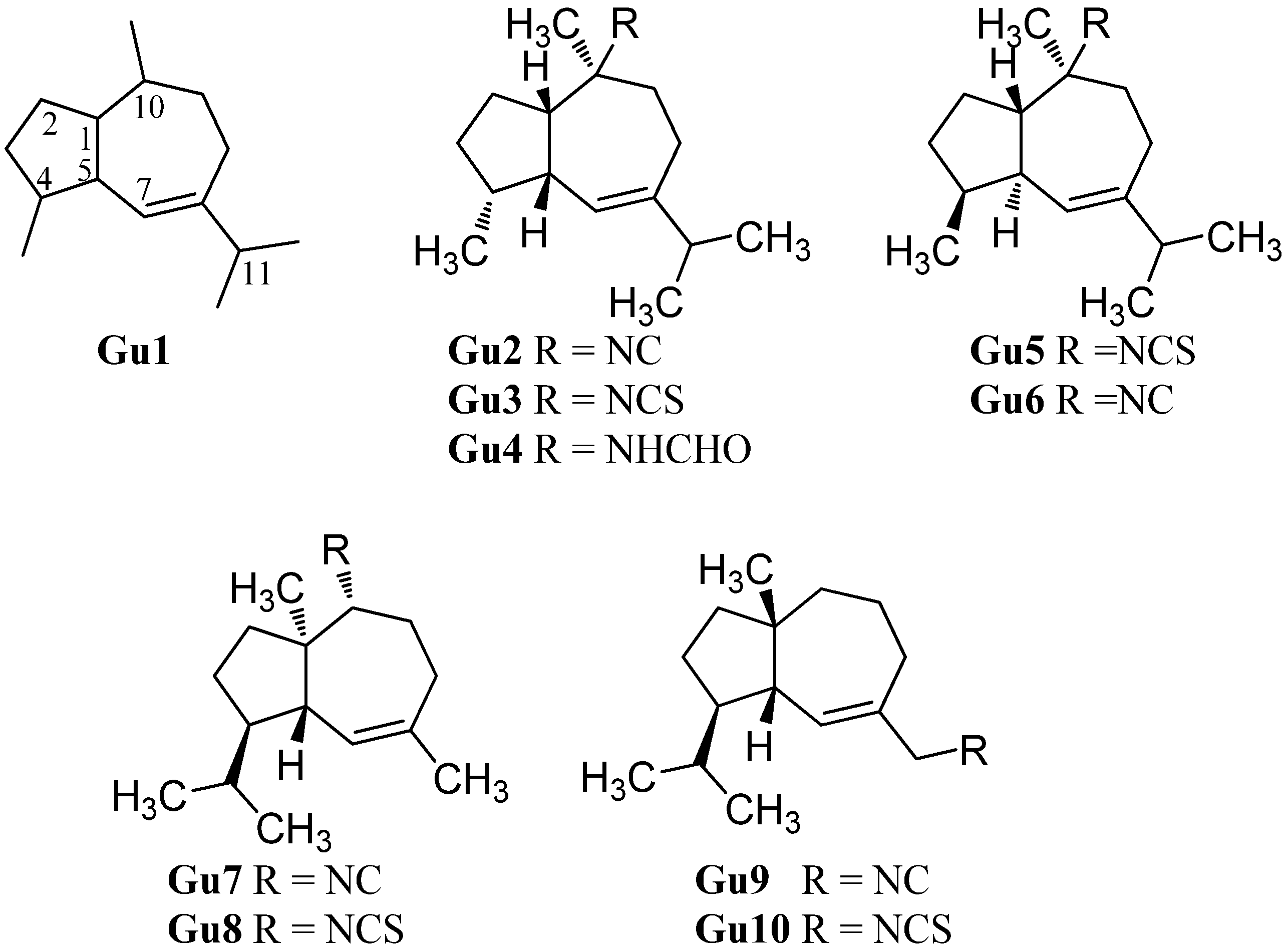

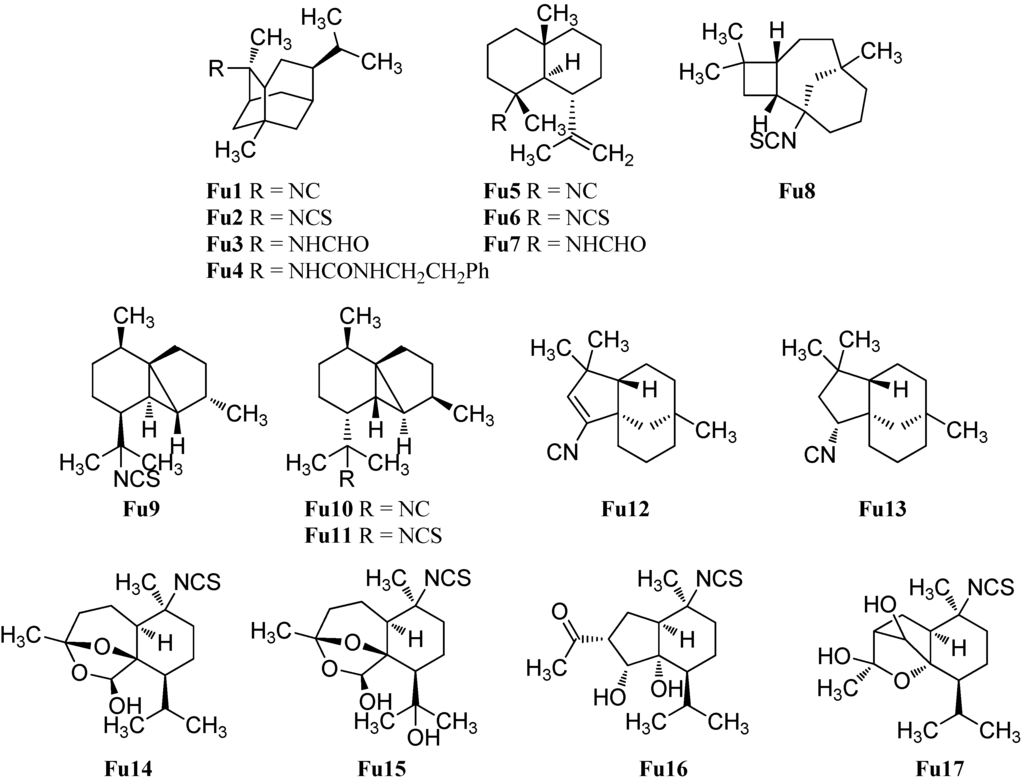

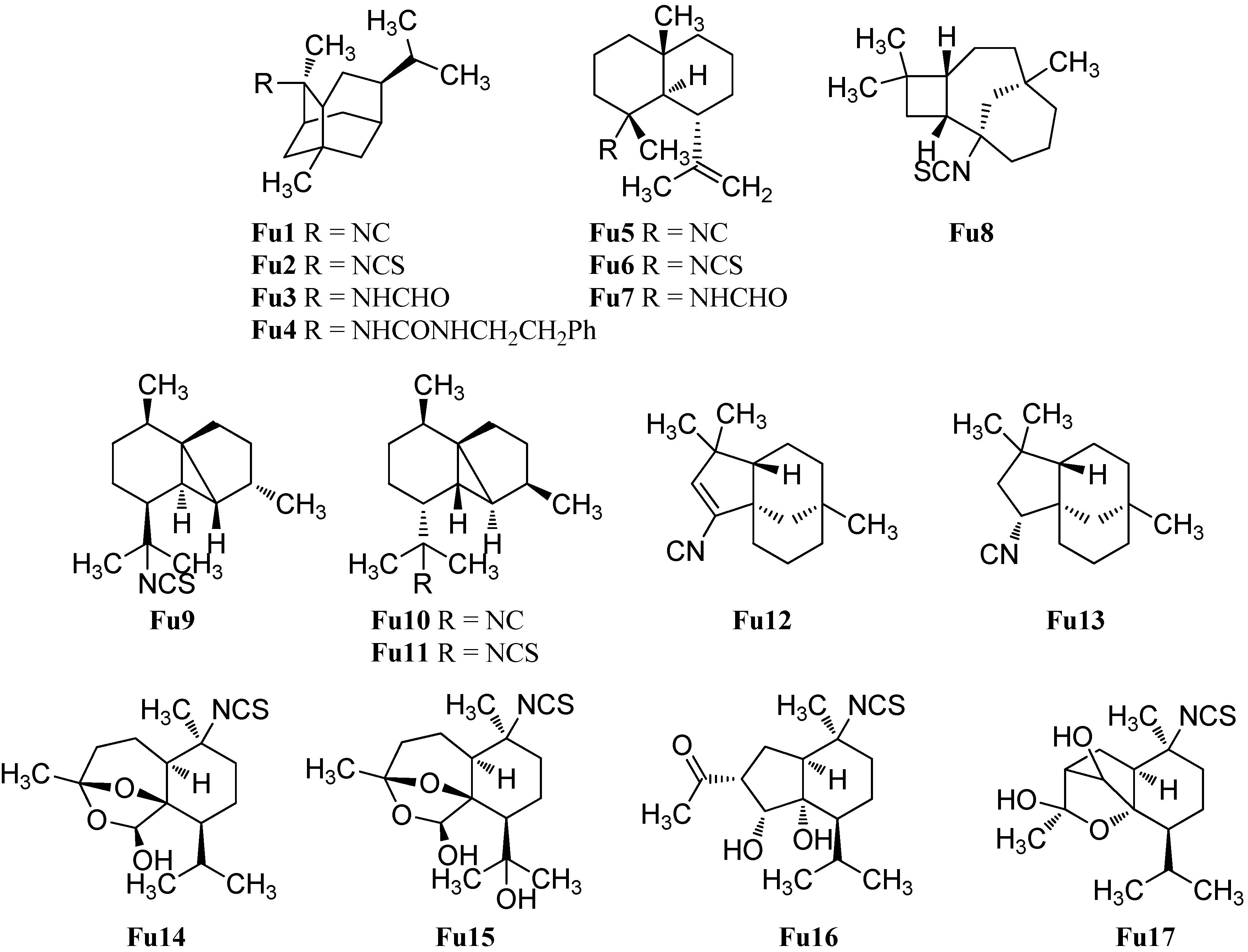

2.1.10. Other Sesquiterpenoids

Apart from the above-mentioned subclasses, there is a small number of marine isonitriloids with uncommon sesquiterpene-based skeletons (Figure 14). He et al. reported in 1989 the isolation of 2-isothiocyanatotrachyopsane (Fu2) with a novel “trachyopsane” skeleton, which is related to the pupukeanane skeleton, from the sponge Trachyopsis aplysinoides [52]. The corresponding 2-isocyanotrachyopsane (Fu1) was obtained seven years later by Okino et al. from four nudibranchs of the Phyllidiidae family [42]. 2-Isocyanotrachyopsane (Fu1, IC50 = 0.33 µg/mL) exhibited potent antifouling activity against larvae of the acorn barnacle Balanus amphitrite [42]. 2-(Formylamino)trachyopsane (Fu3) and N-phenethyl-N′-2-trachyopsane (Fu4) were isolated from the Palauan sponge Axinyssa aplysinoides [95].

The gorgonane skeleton is very similar to the eudesmane skeleton but the isopropyl group is located at C-6 instead of at C-7. Kassuehlke et al. reported the isolation of 4α-isocyanogorgon-11-ene (Fu5) and 4α-formamidogorgon-11-ene (Fu7) from the Philippine nudibranch Phyllidia varicosa along with 4α-isothiocyanatogorgon-11-ene (Fu6) found in the nudibranch Phyllidia pustulosa [86].

Recently, White et al. isolated (−)-(1S,2R,5R,8R)-1-isothiocyanatoepicaryolane (Fu8), the first compound with a caryolane skeleton containing a nitrogenous functional group, from the nudibranch Phyllidia ocellata [94].

Figure 14.

Further sesquiterpenoids.

Figure 14.

Further sesquiterpenoids.

Cubebane sesquiterpenoids possess a very similar skeleton to the cadinanes but they have an additional bond between C-1 and C-5. The first cubebane type sesquiterpenoid, (1S*,2R*,5S*,6S*,7R*,8S*)-13-isothiocyanatocubebane (Fu9), was isolated by He et al. from the sponge Axinyssa aplysinoides [69]. The relative configuration was defined by NOEDS experiments. The C-2 epimer (1S*,2S*,5S*,6S*,7R*,8S*)-13-isothiocyanatocubebane (Fu11) was isolated later by Mitome et al. from the Okinawan sponge Stylissa sp. [50]. The corresponding (1S*,2S*,5S*,6S*,7R*,8S*)-13-isocyanocubebane (Fu10) was obtained in 2015 by White et al. from the nudibranch Phyllidia ocellata [94].

The same group also isolated (−)-(1S,5S,8R)-2-isocyanoclovene (Fu12) and the saturated (−)-(1S,2R,5S,8R)-2-isocyanoclovane (Fu13) from the nudibranch Phyllidia ocellata [94]. The (1S,5S,8R)-configuration of the isonitrile Fu12 was determined by X-ray crystallography of the corresponding formamide, which could be obtained by treatment of isonitrile Fu12 with glacial acetic acid. The new stereocenter in the isonitrile Fu13 was identified by NOESY experiments. The authors propose that the cycloclovane skeleton is formed from the epicaryolane skeleton by an 1,2-alkyl shift [94].

In 2008 Sorek et al. reported the isolation of five new marine isothiocyanates (Axiplyns A–E) from the sponge Axinyssa aplysinoides collected at Misali Island, Tanzania [54]. Axiplyn A (Fu14) and B (Fu15) contain a unprecedented ring system, 6,8-dioxabicyclo[3.2.1]octane. However, Axiplyn D (Fu16) has a bridged hydroindane skeleton and Axiplyn E (Fu17) has a 2-oxabicyclo[2.2.1]heptane core. Axiplyn C (Ca34) is a cadinane type sesquiterpenoid and was already described in Section 2.1.3. Axiplyns A (Fu16, LD50 = 1.6 µg/mL), B (Fu17, LD50 = 1.5 µg/mL) and C (Ca33, LD50 = 1.8 µg/mL) displayed toxic activities to brine shrimp larvae (Artemia salina) [54].

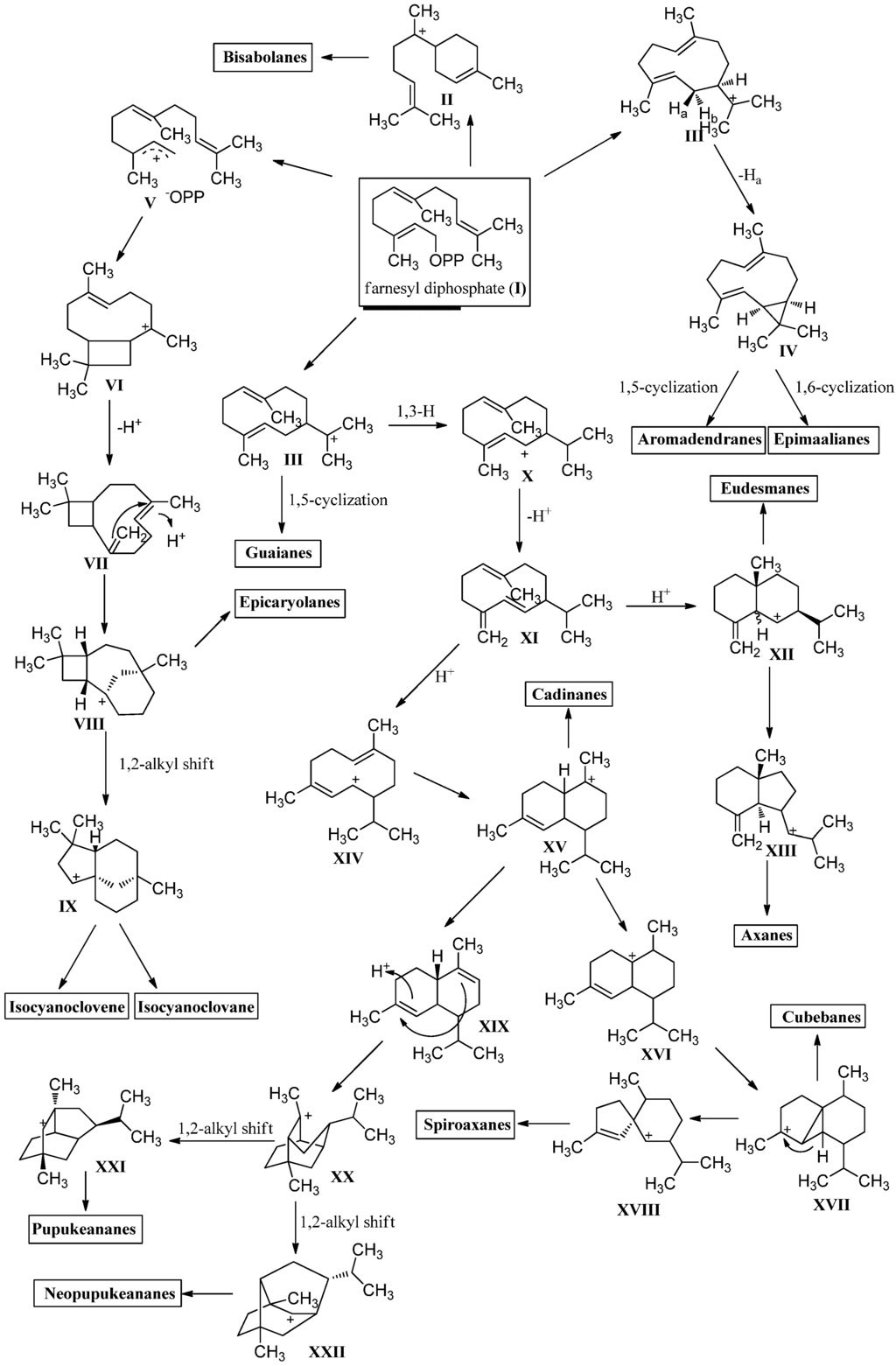

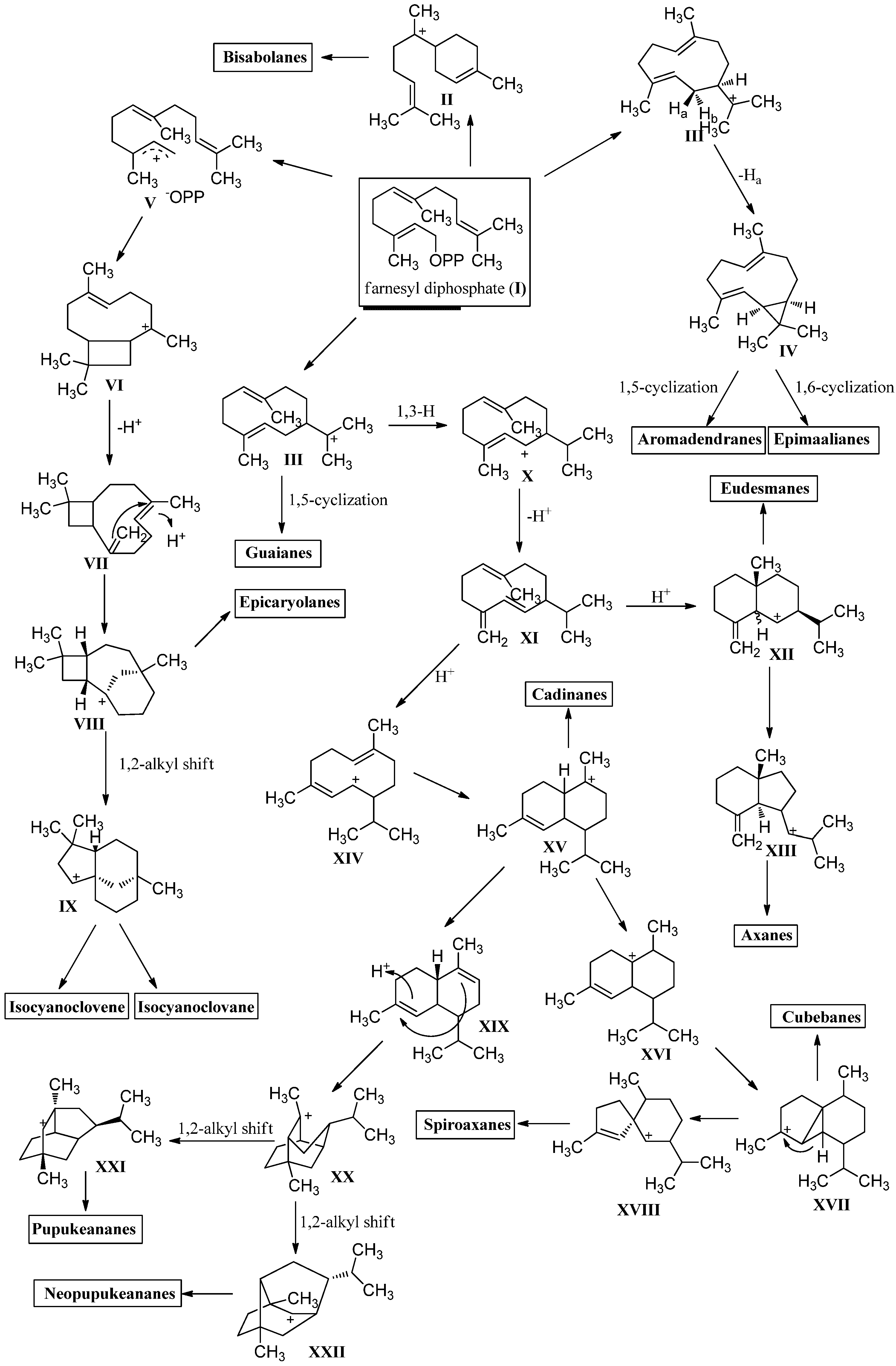

2.2. Diterpenoids

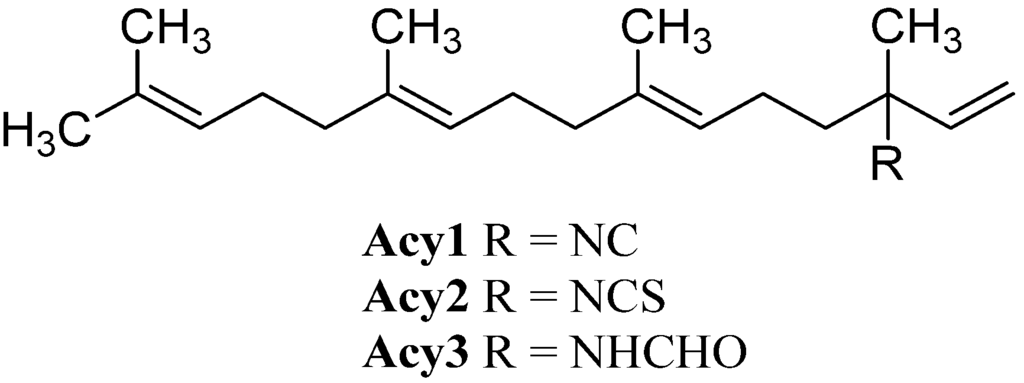

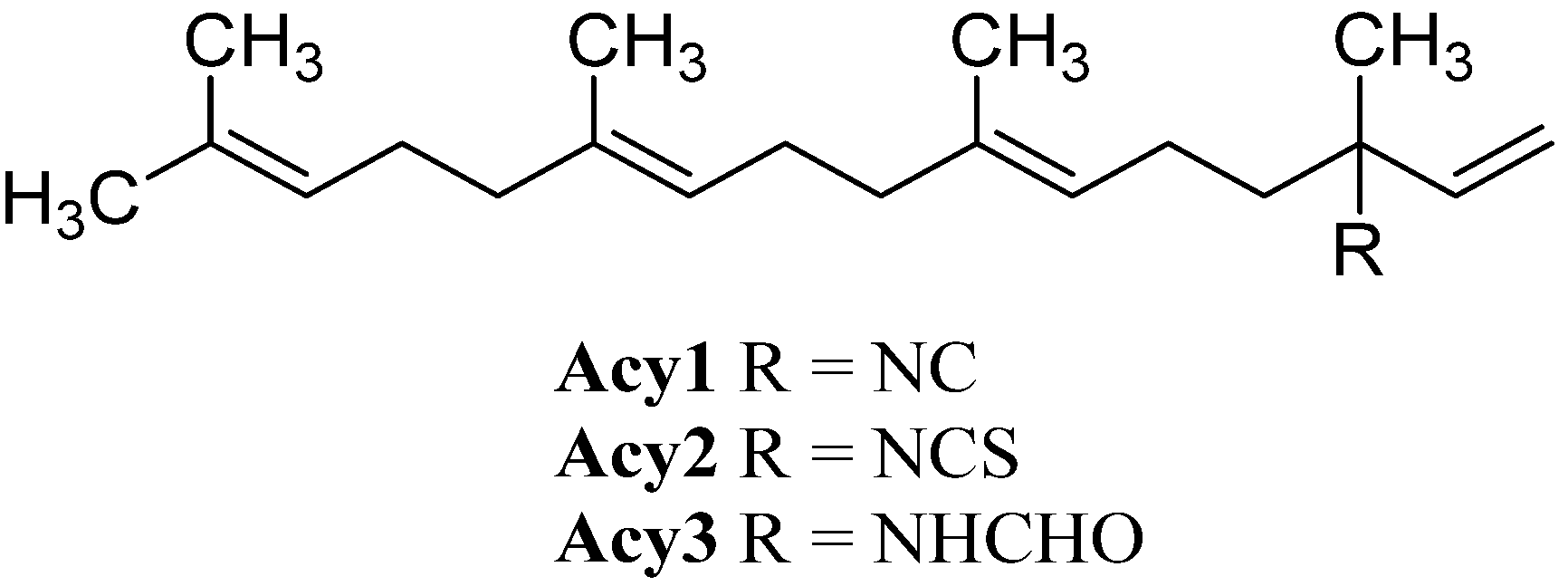

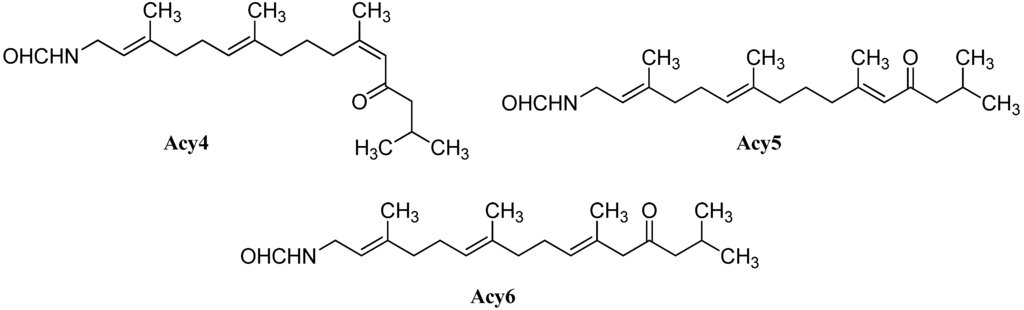

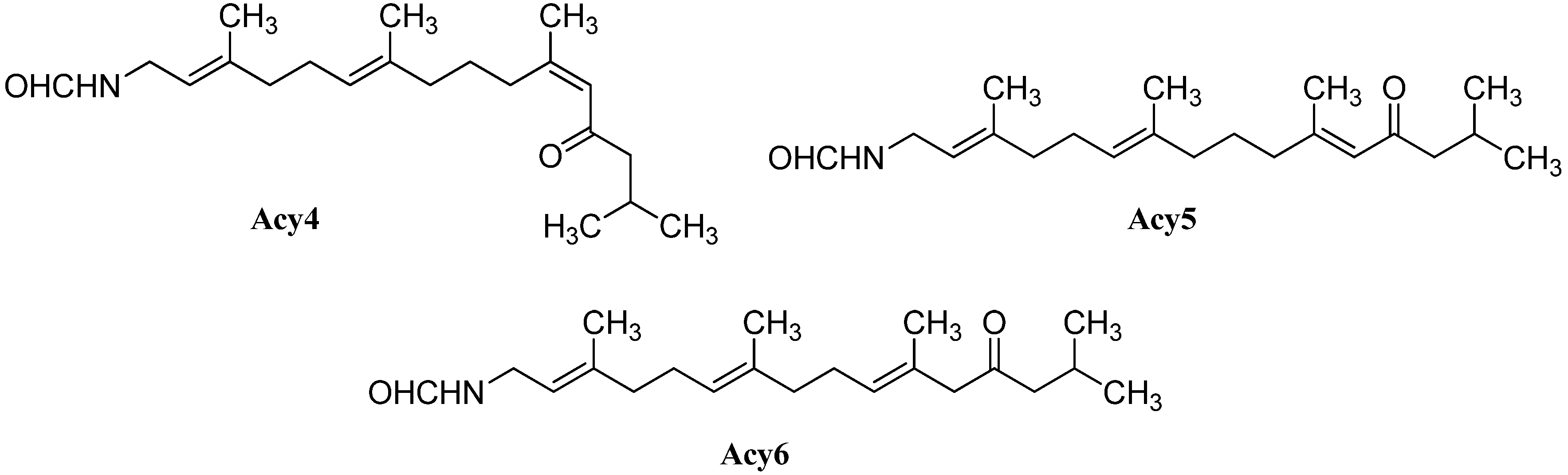

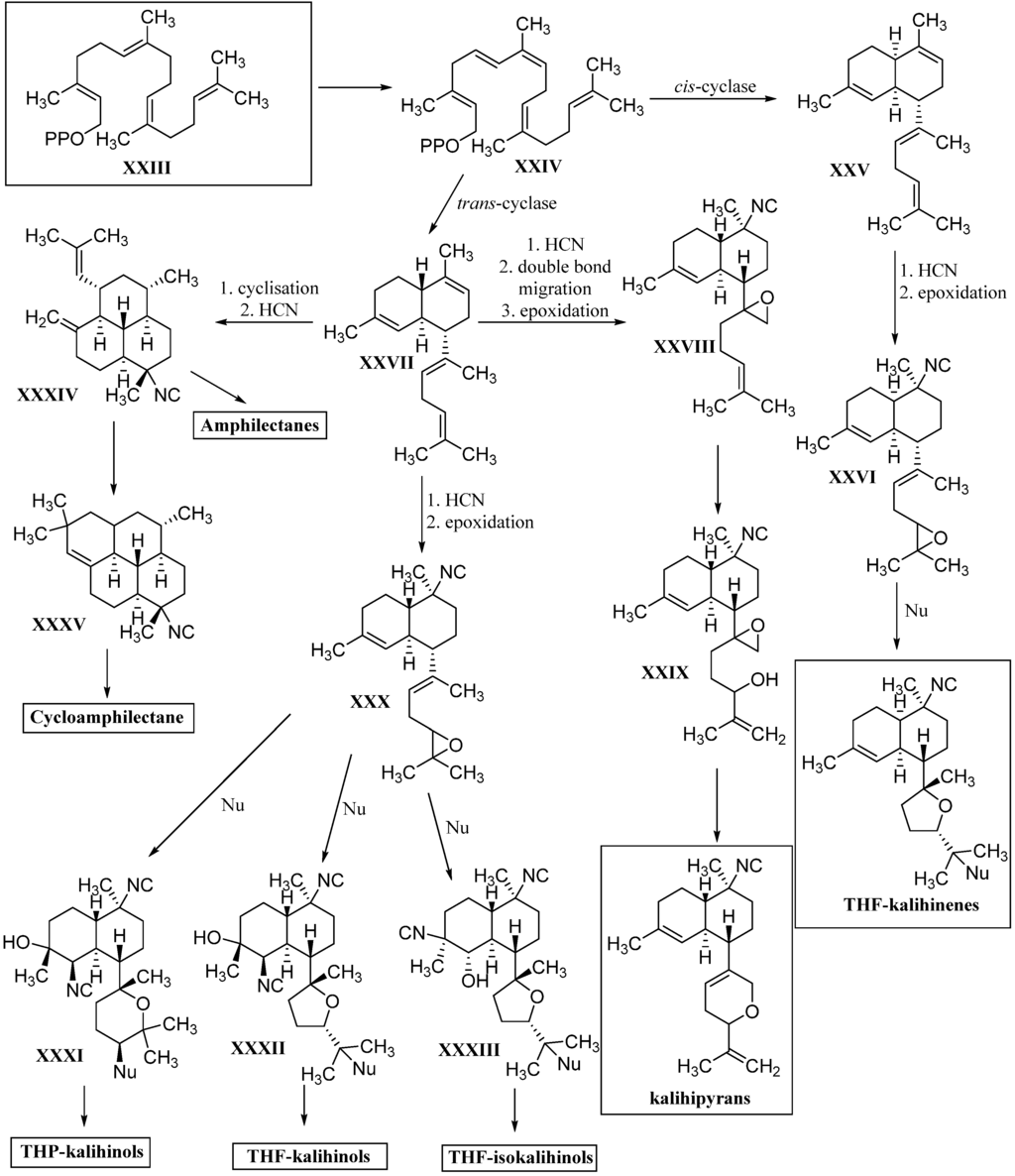

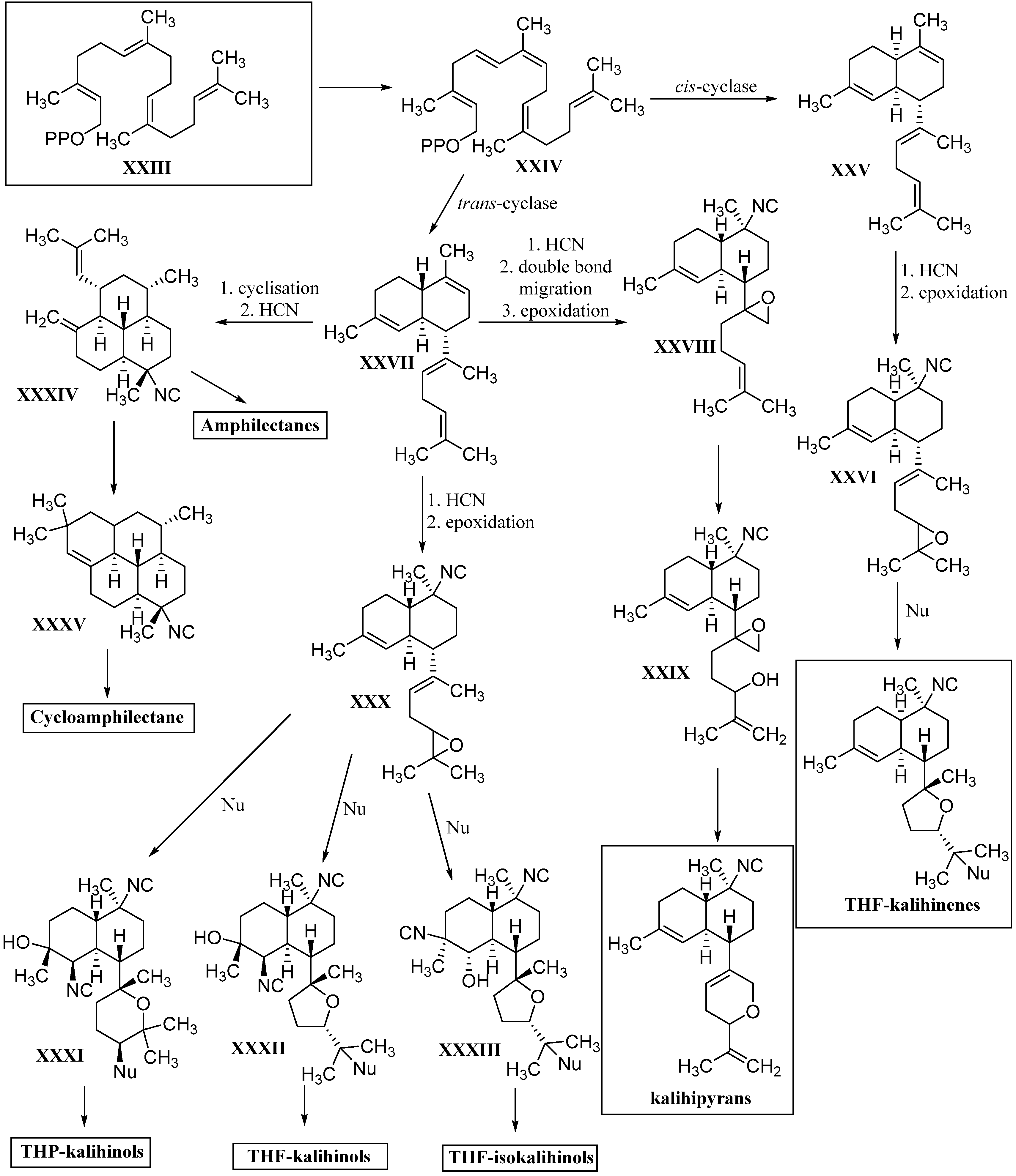

Beside the cyclic sesquiterpenoid compounds already presented in this review, a large fraction of marine isonitriles and isothiocyanates were found to have diterpenoid backbones. They can be categorized into three classes: Acyclic diterpenes, kalihinanes, and amphilectanes.

Until today, six acylic compounds, 69 kalihinanes and 50 amphilectanes have been isolated.

2.2.1. Acyclic

The smallest class, the acyclic diterpenoids, is represented by a isonitriloid triad consisting of isocyanate Acy1, isothiocyanate Acy2 and formamide Acy3, which were the only representatives found until 2006 (Figure 15). The triad was found in 1974 by Burreson et al. along with cyclic sesquiterpenes in an unidentified Halichondria species [39,40].

Figure 15.

Acyclic diterpenoids.

Figure 15.

Acyclic diterpenoids.

Further open-chain terpenoid formamides were isolated from sea fans. Malonganenone C (Acy4), a diterpenoid formamide showing moderate cytotoxic activity against esophageal cancer cell lines, was found in extracts of the gorgonian Leptogorgia gilchristi collected near Ponto Malongane, Mozambique by Keyzers in 2006 (Figure 16) [96]. It was also found in another sea fan, Euplexaura nuttingi (Uvinage, Pemba Island, Tanzania) in 2007 by Sorek et al. who were able to isolate Malonganenone C along with its Δ11,12-(E) double bond isomer malonganenone H (Acy5) [97]. Examination of Euplexaura robusta collected near Weizhou Island (Guangxi Province, China) in 2012 by Zhang et al. revealed the Δ10,11-double bond isomer Malonganenone K (Acy6) [98]. Despite the occurrence of these three new members this class of acyclic compounds still appears as an exception among the other diterpenoid isonitriles which are usually cyclic.

Figure 16.

Malonganenones.

Figure 16.

Malonganenones.

2.2.2. Kalihinanes

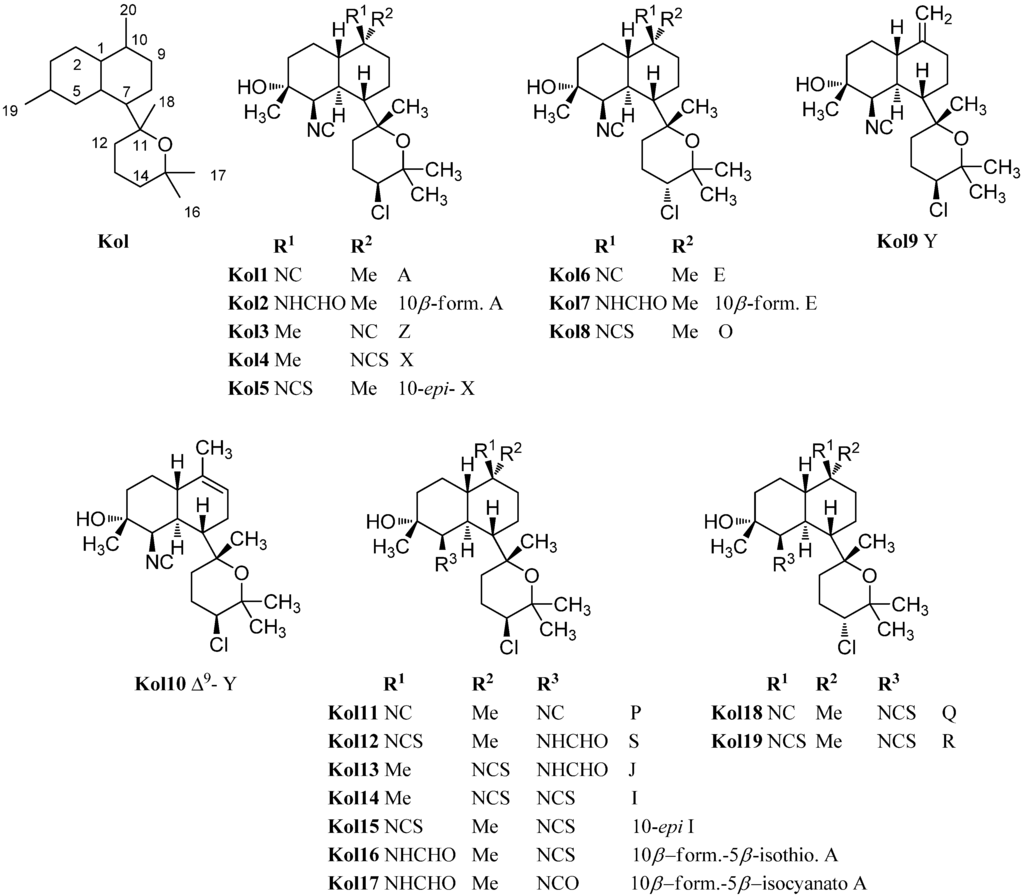

Common to all kalihinanes is the decalin ring system which, apart from some exceptions (cavernenes) which will be discussed later on, either bears a tetrahydofuran, a tetrahydropyran or a dihydropyran moiety linked to C-7. All three rings can bear a large variety of functional groups including isocyano-, isothiocyanato- and hydroxy groups or chlorine. The kalihinanes can be further classified into kalihinols, kalihinenes, kalihipyranes and cavernenes. Most kalihinanes were found in A. cavernosa whereas also a few examples exist that were isolated from the sponge Phakellia pulcherrima.

Kalihinols

Characteristic for the kalihinols is the tertiary alcohol function at C-4 of a trans-decalin system being part of a bifloran skeleton (Figure 17). They can be further subdevided into two groups according to their substitution with a tetrahydropyran or a tetrahydrofuran moiety at C-7. The first eleven kalihinols were found by the Scheuer group of Hawaii in 1987 in two sponges of Acanthella sp. (later indentified as A. cavernosa) [99] and were published in a series of communications [100,101,102]. The kalihinols A–H were isolated from an Acanthella sp. collected at Guam, whereas examination of a Fijian Acanthella species revealed kalihinols X (Kol4), Y (Kol9) and Z (Kol3). Kalihinols A (Kol1), E (Kol6), X (Kol4), Y (Kol9) and Z (Kol3) are all linked at C-7 to a C-14 chlorinated tetrahydropyran moiety and bear an isonitrile function at C-5. Kalihinol E (Kol6) represents the C-14-epimer of kalihinol A (Kol1) just having another orientation of the chlorine substituent. The formamide derivatives of A and E, 10β-formamido kalihinol A (Kol2) and 10β-formamido kalihinol E (Kol7) were isolated in 1996 by Hirota et al. from A. cavernosa while the isothiocyanato derivative, found in the same producer by Xu et al. in 2004, was named kalihinol O (Kol8) [20]. Kalihinol Z (Kol3) on the other hand represents the C-10-epimer of kalihinol A (Kol1), whereas kalihinol X (Kol4) is the 10-isothiocyanato derivative of kalihinol Z (Kol3). Further investigation of A. cavernosa by Sun et al. in 2009 revealed a kalihinol with the opposite stereochemistry at C-10, 10-epi-kalihinol X (Kol5) [103]. Unlike the other tetrahydropyran kalihinols, kalihinol Y (Kol9) bears an exocyclic methylene group at C-10. In 1998, Wolf was able to isolate along with kalihinol Y its double bond isomer Δ9-kalihinol Y (Kol10) from the sponge Phakellia pulcherrima, which was the first time that kalihinanes were found in sponge other than A. cavernosa [104]. Independently from Wolf, Miyaoka also discovered the same kalihinol in A. cavernosa in the same year [105]. In antihelmintic screenings, kalihinol Y (Kol9) displayed extremely high activity against the rodent-pathogenic roundworm Nippostongylus brasiliensis. The kalihinols A (Kol2), X (Kol4) and Z (Kol3) also showed high activity [106].

The first time that kalihinols with other functional groups than the isonitrile group at C-5 were found in 1991 when Alvi was able to isolate kalihinols I (Kol14) and J (Kol13) from A. cavernosa, which are the 5-formamide and the 5-isothiocyanato congeners of kalihinol X (Kol4) respectively [49]. 10-epi-Kalihinol I (Kol15) was isolated by Miyaoka, while Hirota et al. were able to identify the C-5 isocyanato- and isothiocyanato-derivatives 10β-formamido-5β-isothiocyanato-kalihinol A (Kol16) and 10β-formamido-5β-isocyanato-kalihinol A (Kol17) [20,105]. The isocyanato derivative of kalihinol A (Kol1) was found in 2012 by Xu et al. and was named kalihinol P (Kol11) as well as kalihinol S (Kol12), representing the C-5 formamide derivative of 10-epi-kalihinol X (Kol5) [107]. Further investigations of the same sample revealed kalihinols Q (Kol18) and R (Kol19), which are the C-14 epimers of Kol11 and Kol15 respectively [107].

Figure 17.

Tetrahydropyran kalihinols.

Figure 17.

Tetrahydropyran kalihinols.

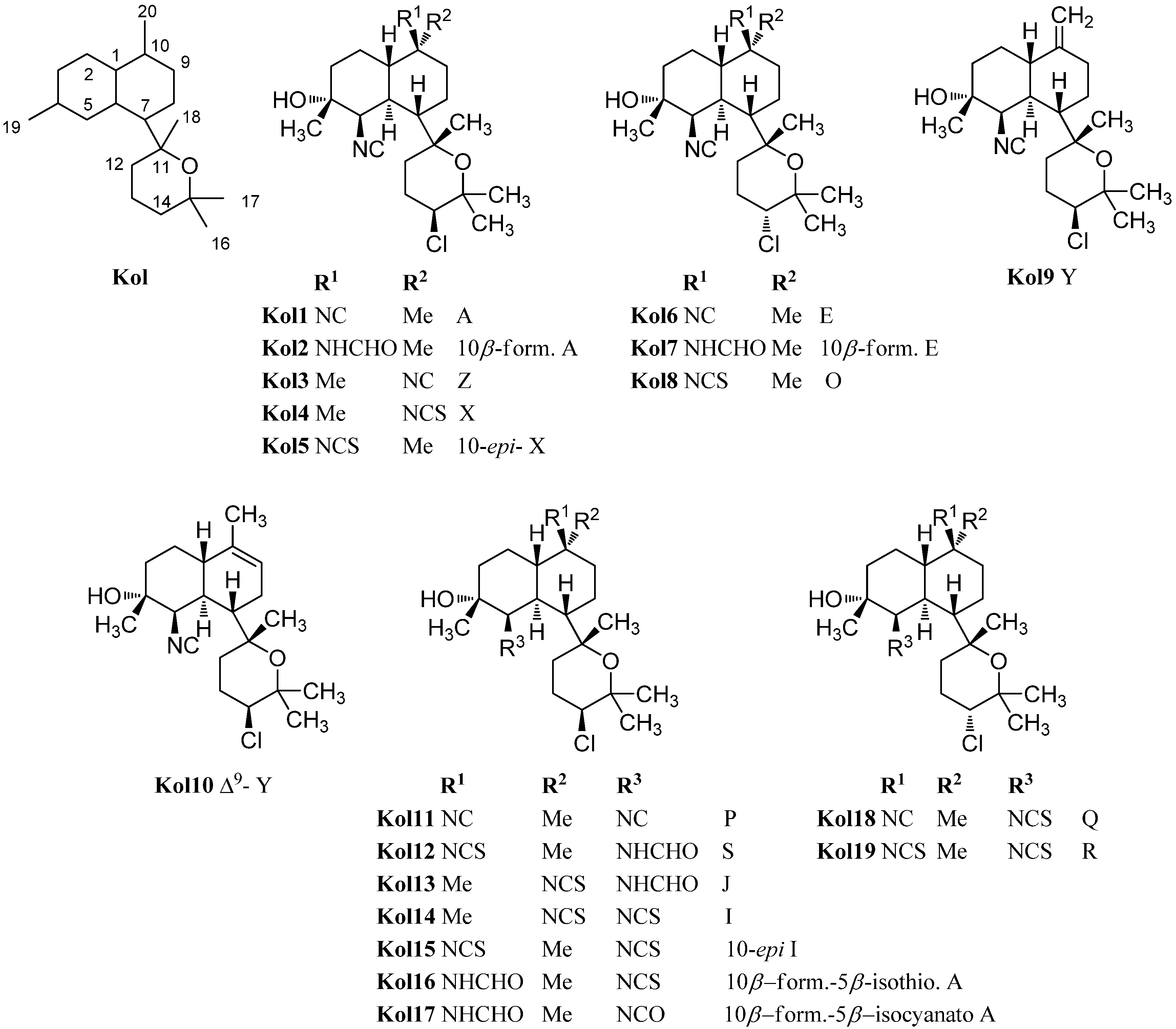

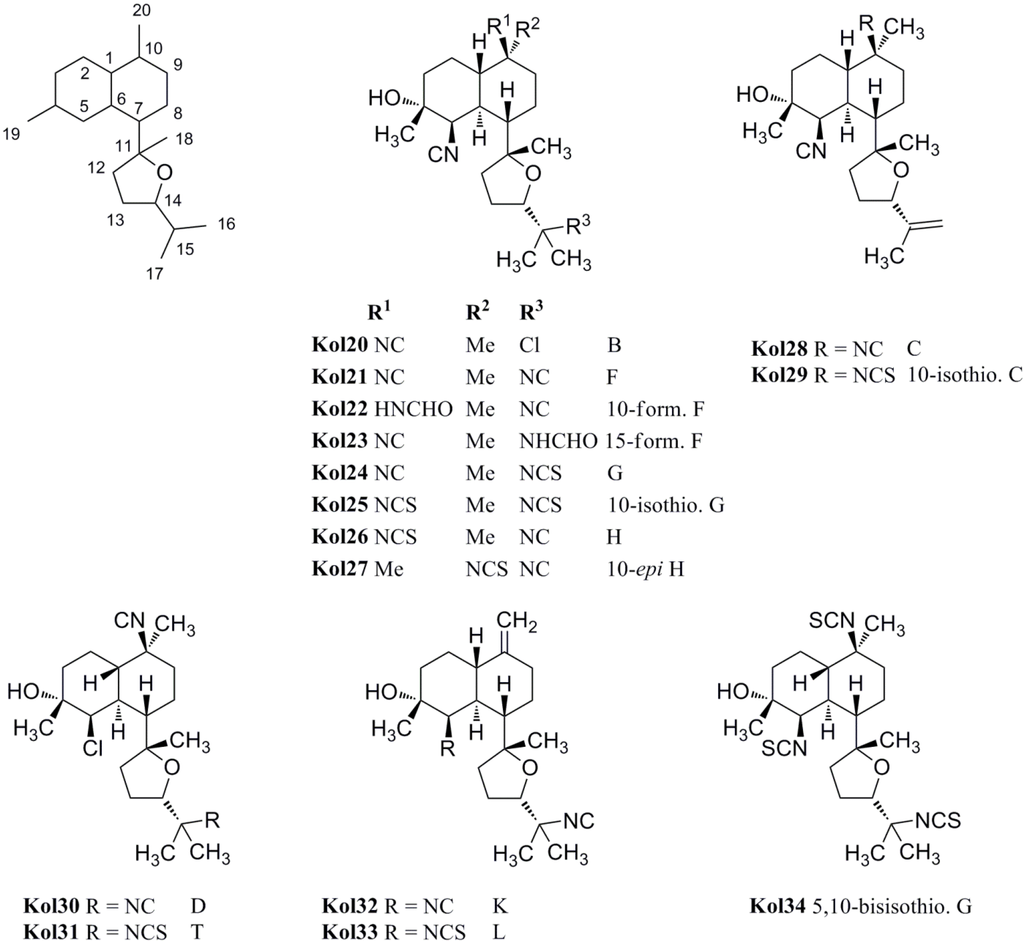

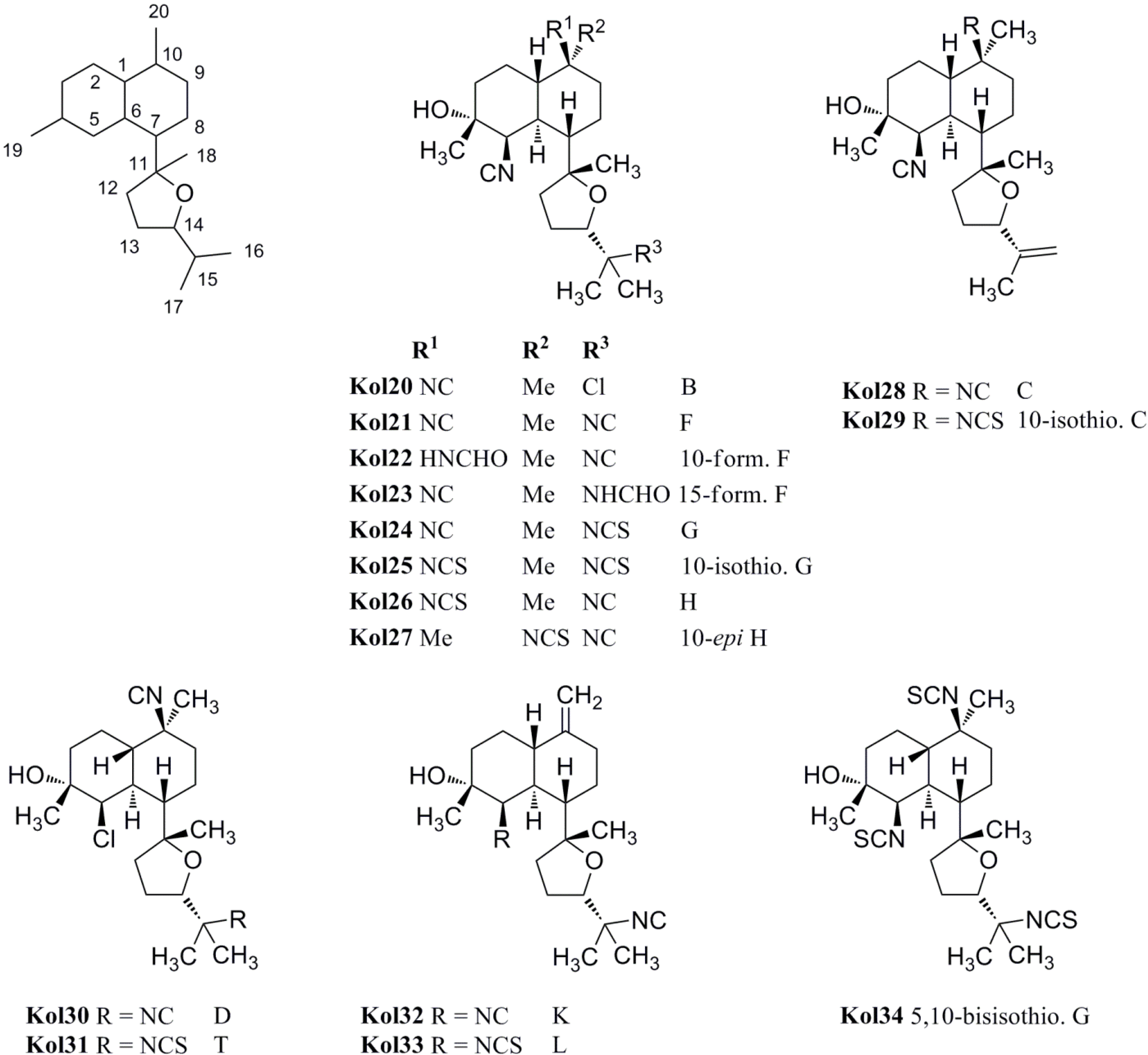

The first representatives of the tetrahydrofuran subclass of kalihinols were kalihinols B (Kol20), C (Kol28), D (Kol30), F (Kol21), G (Kol24) and H (Kol26) discovered by the Scheuer group in the 1980s (Figure 18) [101,102]. The stereochemical and functional variations occur at C-5 and C-10 as in the tetrahydropyran-type kalihinols. Additionally, the tetrahydrofuran moiety can be functionalized at C-15 with isonitrile, isothiocyanate, formamide or chlorine. Examples bearing an isopropenyl side chain are also known.

Kalihinol F (Kol21), a representative of the tetrahydrofuran-type kalihinols, is substituted with three isonitrile groups at C-5, C-10 and C-15. It was shown to be a topoisomerase I inhibitor in Asterina pectinifera, inhibiting the chromosome separation in fertilized starfish eggs [108] and to have antimicrobial activity against Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans [101]. Kalihinol B (Kol20) differs from Kalihinol F (Kol21) just in the functional group at C-15, which is a chlorine instead of an isocyano group. In 2004, Bugni was able to isolate the formamide derivatives 10-formamido kalihinol F (Kol22) and 15-formamido kalihinol F (Kol23) from two Philippine specimens of A. cavernosa [109]. The C-15 isothiocyanate derivative of kalihinols B and F was named kalihinol G (Kol24), while kalihinol H (Kol26) represents the C-10-isothiocyanato derivative of kalihinol F [102].

Figure 18.

Tetrahydrofuran-substituted kalihinols.

Figure 18.

Tetrahydrofuran-substituted kalihinols.

The first member of the class bearing an isopropenyl side chain was kalihinol C (Kol28), which is functionalized at C-5 and C-10 with two isonitrile groups. Kalihinol D (Kol30) represents the 5-Cl-derivative of kalihinol F (Kol21)[102]. Its C-15-isothiocyanato derivative, kalihinol T (Kol31), was isolated by Xu in 2012 from A. cavernosa [107].

In 1998, the Miyaoka group was able to isolate the tris-isothiocyanato compound 5,10-bisisothiocyanatokalihinol G (Kol34) [105]. Further tetrahydrofuran-type kalihinols were presented in the same year by Wolf et al. who identified 10-isothiocyanato kalihinol G (Kol25), 10-epi-kalihinol H (Kol27), and 10-isothiocyanato kalihinol C (Kol29) from a sample of Phakellia pulcherrima [104]. From the same sample, the structures of two compounds with a 10-exo-methylene group were elucidated, kalihinol K (Kol32) bearing an isonitrile substituent at C-5 and its isothiocyanato derivative kalihinol L (Kol33), representing the tetrahydrofuran analogues of kalihinol Y (Kol9) [104].

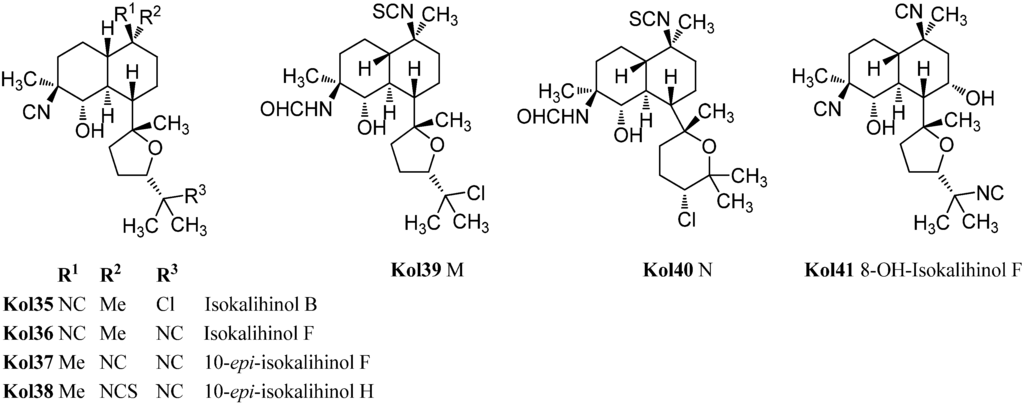

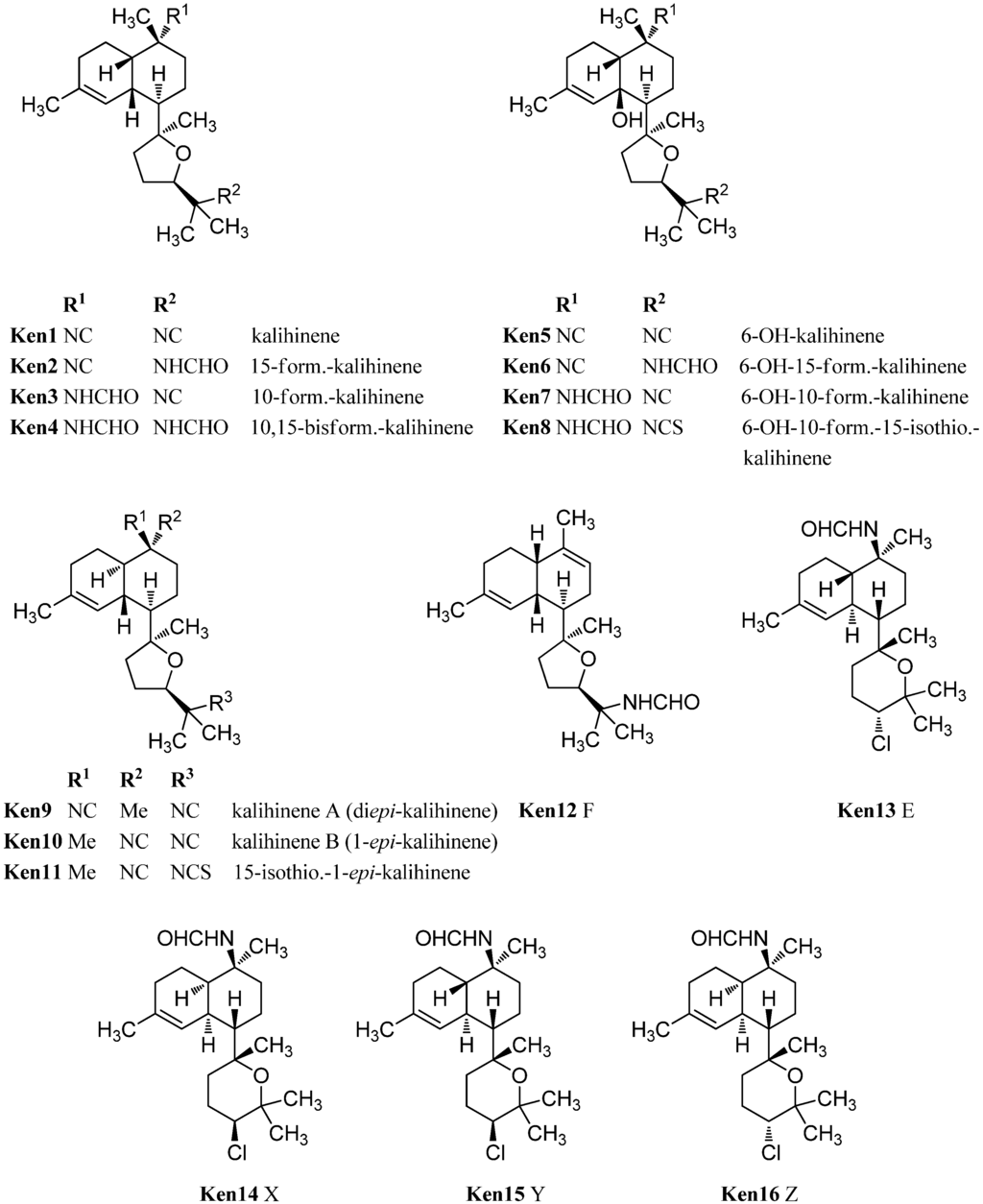

Already in 1988, Omar et al. were able to isolate a variant of the kalihinols with swapped positions of the hydroxy and isonitrile groups at C-4 and C-5 (Figure 19) [106]. The stereochemistry of both groups is opposite compared to the normal kalihinols, presumably due to a different opening of the intermediate epoxide in the biosynthetic pathway. The first example of this so-called “isokalihinols” was isokalihinol F (Kol36) which, except for C-4 and C-5, showed the same configuration and functionalization as kalihinol F (Kol21). 8-OH-Isokalihinol F (Kol41), a rather unusual isokalihinol bearing an additional hydroxy group at C-8, was isolated by Clark et al. in 2000 from A. cavernosa collected at Heron Island (Great Barrier Reef, Australia) [31].

Figure 19.

Isokalihinols.

Figure 19.

Isokalihinols.

Three further isokalihinols with an NC-function at C-4 are known to date: Isokalihinol B (Kol35), being related to kalihinol B (Kol20), was found in 1990 by Fusetani in a marine sponge collected in Kuchihoerabu Island of the Satsunan Archipelago (Japan) which was identified as Acanthella klethra [110]. Rodriguez and Crews revised this assignment afterwards based on voucher samples to be actually A. cavernosa [99]. Isokalihinol B (Kol35) and kalihinene (Ken1) demonstrated besides antifungal activities against Mortierella romannicus and Penicillium chrysogenum also cytotoxic potency against P388 murine leukemia cells (IC50 = 0.8 µg/mL and 1.2 µg/mL), respectively [110].

Many kalihinanes displayed antifouling potency. Kalihinols Kol1 (EC50 = 0.087 µg/mL), Kol2 (EC50 < 0.5 µg/mL), Kol6 (EC50 < 0.5 µg/mL), Kol7 (EC50 = 0.5 µg/mL), Kol16 (EC50 = 0.05 µg/mL) and Kol17 (EC50 = 0.05 µg/mL) and kalihinenes Ken2 (EC50 = 0.095 µg/mL), Ken14 (EC50 = 0.49 µg/mL), Ken15 (EC50 = 0.45 µg/mL) and Ken16 (EC50 = 1.1 µg/mL) were shown to inhibit the attachment and metamorphosis of cyprid larvae of the acorn barnacle Balanus amphitrite [20,111].

The other two known isokalihinols are 10-epi-isokalihinol F (Kol37) and the C-4,5-regioisomer of 10-epi-kalihinol H (Kol27), 10-epi-isokalihinol H (Kol38), which were isolated by Faulkner in 1994 from A. cavernosa collected in the Seychelles [112].

In 2012, Xu et al. reported two novel C-4 formamido representatives of isokalihinols in a South China Sea specimen of A. cavernosa, kalihinol M (Kol39) bearing an isothiocyanato group at C-10 and a chlorine atom at C-15 and kalihinol N (Kol40), the 4-formamido-iso-derivative of kalihinol O (Kol8), representing the first example of isokalihinols of the tetrahydropyran type [107].

Kalihinenes

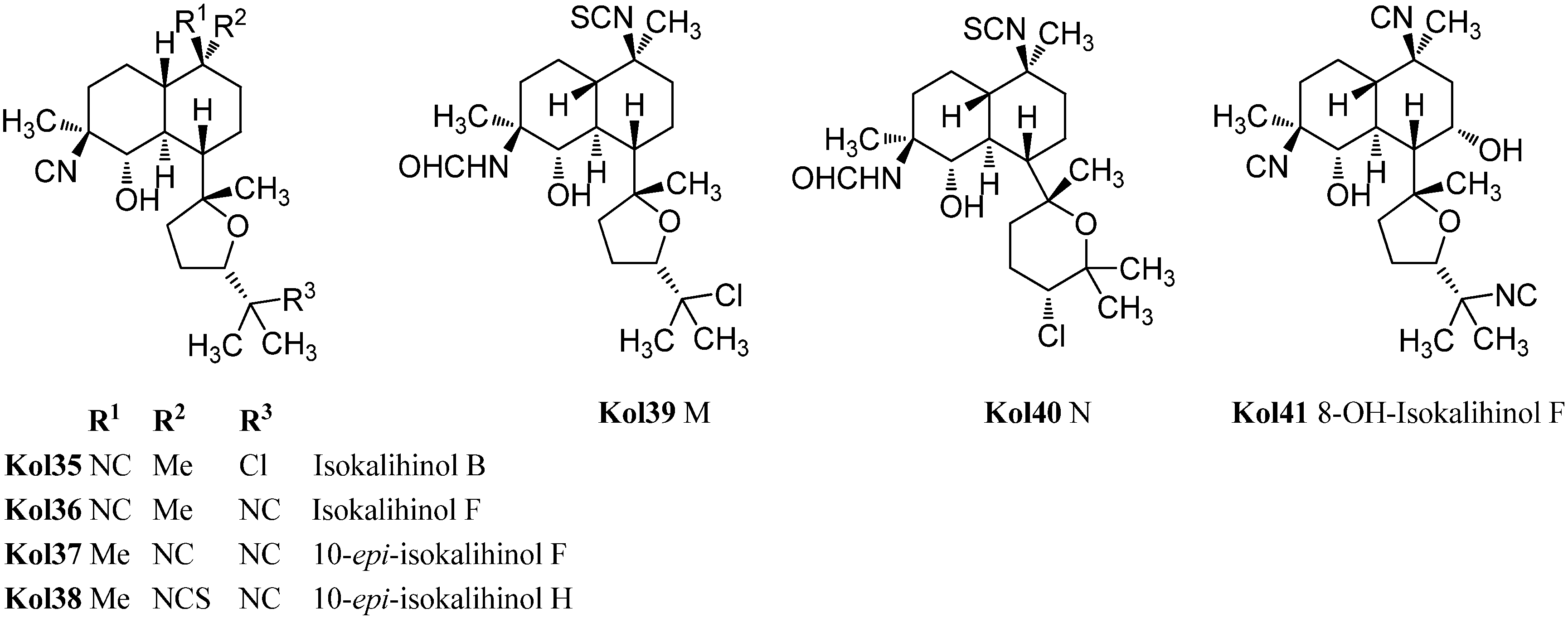

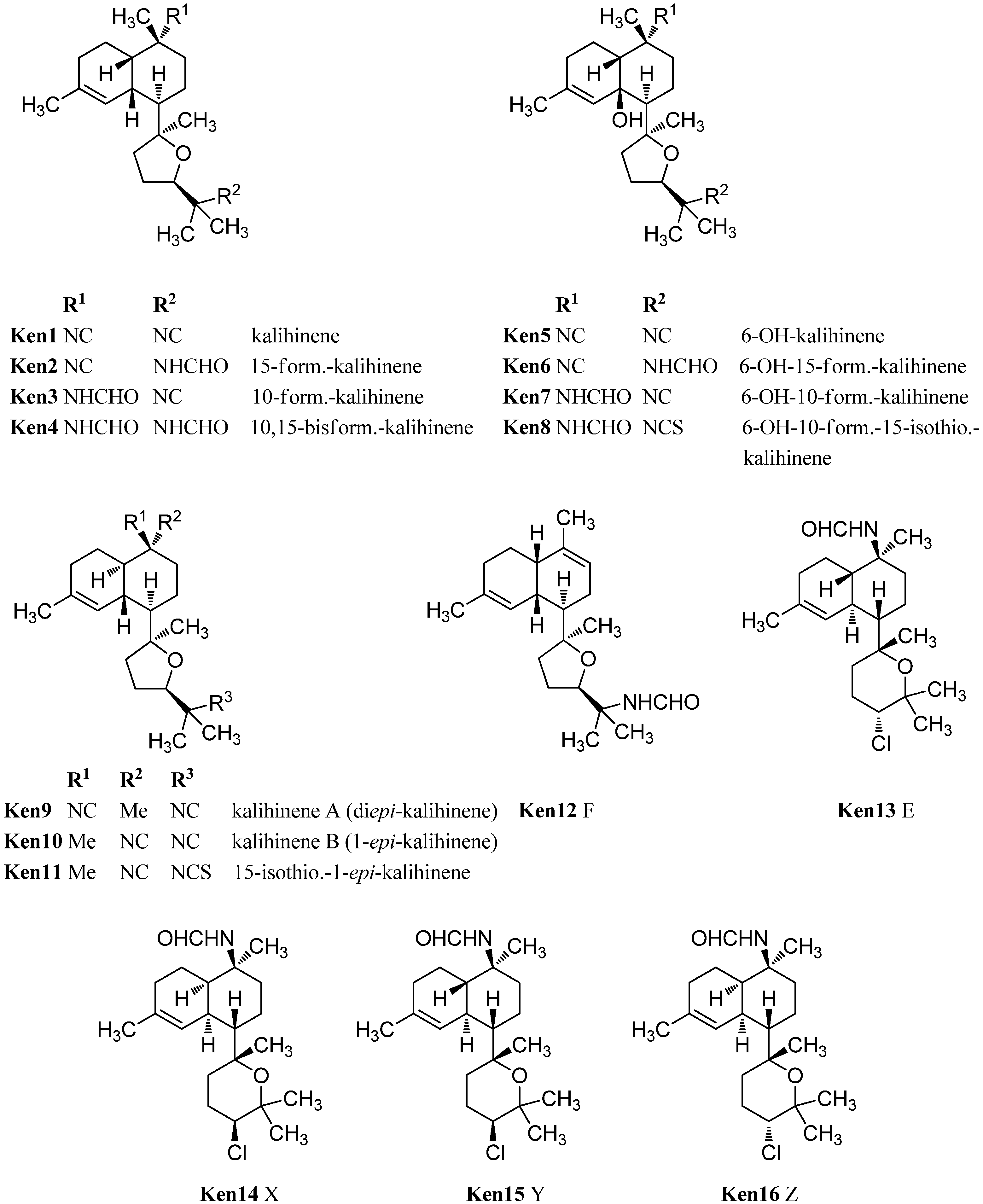

Common to all kalihinenes is the trisubstituted Δ4-double bond and a heterocyclic C8-substituent at C-7 equal to the kalihinols. However, unlike the kalihinols, which to date exclusively featured trans-decalin skeletons, the kalihinenes also exist with cis-decalin backbones (Figure 20).

The prototype of this class after which all other members are named, kalihinene (Ken1), was found in 1990 by Fusetani in a misassigned Acanthella klethra sample (actually cavernosa) [110]. Examination of a Fijian sample of A. cavernosa by Rodriguez et al. resulted in the isolation and identification of 15-formamido-kalihinene (Ken2), 10-formamido kalihinene (Ken3) and 10,15-bisformamido kalihinene (Ken4) [99]. The team additionally proved the persistence of these compounds in sponges kept in an aquaculture for seven months. Together with the three cis-formamido kalihinenes, Rodriguez et al. were also able to identify four members with a novel 6-hydroxy kalihinene framework. The first representative, 6-hydroxy-kalihinene (Ken5), exhibits the same cis-decalin backbone and functional groups as kalihinene but is hydroxylated at C-6. The other isolated examples are the formamido- and formamido-isothiocyanato derivatives 6-hydroxy-15-formamido kalihinene (Ken6), 6-hydroxy-10-formamidokalihinene (Ken7) and 6-hydroxy-10-formamido-15-isothiocyanato kalihinene (Ken8) [99].

Figure 20.

Kalihinenes.

Figure 20.

Kalihinenes.

Another variation of the cis-decalin tetrahydrofuran-substituted kalihinenes is kalihinene F (Ken12), which was isolated in 2012 by Xu et al. and bears a trisubstituted Δ9-double bond similar to Δ9 kalihinol Y (Kol10) [113].

Three kalihinenes with a trans-decalin framework were reported in 1994 by Faulkner et al. [112]. Besides kalihinene A (also named diepi-kalihinene) (Ken9) which is, apart from the double bond, identical to kalihinol F (Kol21), the group could also isolate kalihinene B (or 1-epi-kalihinene) (Ken10) and 15-isothiocyanato-1-epi-kalihinene (Ken11). In contrast to the twelve isolated members of the tetrahydrofuran-substituted kalihinene series, only four tetrahydropyran derivatives are known to date. The first three examples were the kalihinenes X (Ken14), Y (Ken15), and Z (Ken16) isolated in 1995 by Okino et al. from A. cavernosa [111]. All of them bear a formamide function at C-10 and a chlorine at C-14. Differences only consist in the stereochemistry at C-1 and C-14. In 2012, the Xu group added the missing fourth diastereomer kalihinene E (Ken13) also found in the same producer [113]. Its absolute configuration was elucidated by X-ray crystallography.

Kalihinene (Ken1), kalihinol A (Kol1), and kalihinol E (Kol6) were also found by Manzo et al. in 2004 in Phylidiella pustulosa, a nudibranch from the South China Sea [35]. The dietary origin of these diterpenoids is strongly supported by several investigations.

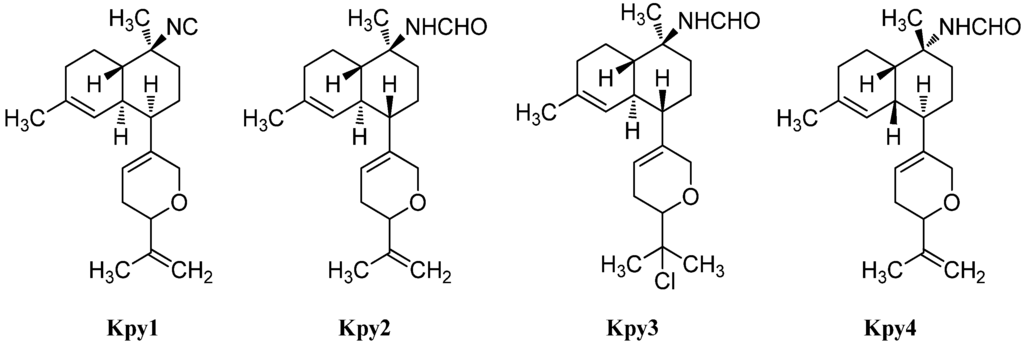

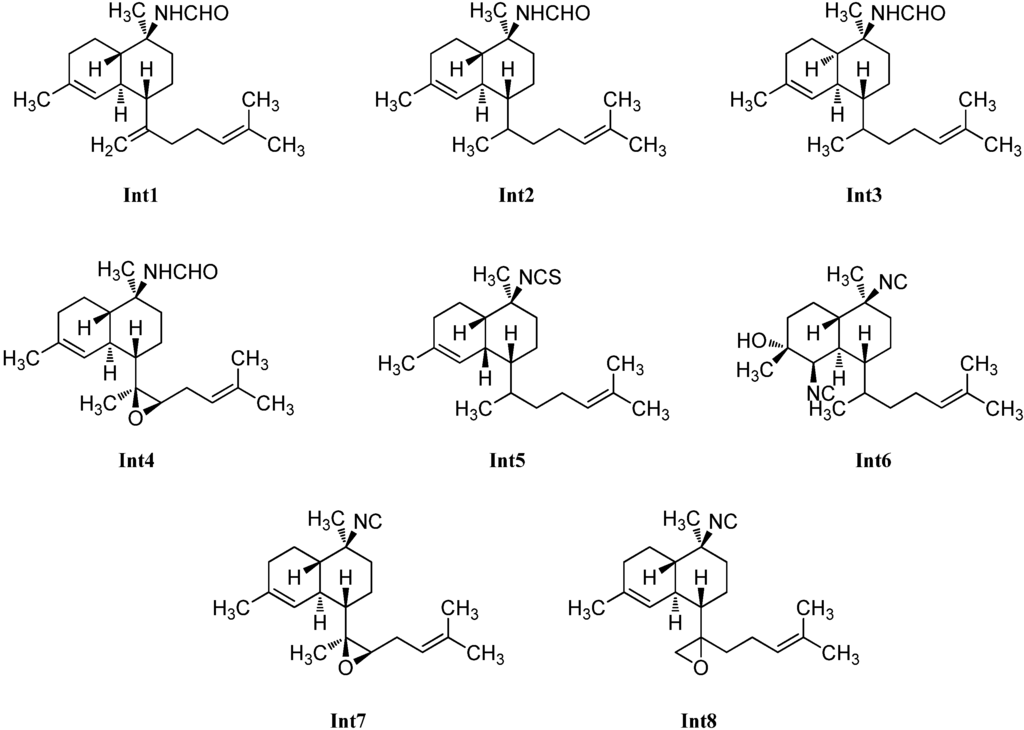

Besides the tetrahydropyran and tetrahydrofuran series of kalihinenes, a third group of kalihinenes with a different pendant C8-unit exists. The first member of this class, kalihipyran (Kpy1), was discovered by Faulkner et al. in 1994 in A. cavernosa (Figure 21) [112]. It shows a kalihinene type trans-decalin system with an isonitrile function at C-10 and is connected at C-7 to a dihydropyran with isopropenyl side chain. Its C-10 formamide derivative kalihipyran A (Kpy2) was isolated in 2012 by Xu et al. along with the cis-decalin derivative kalihipyran C (Kpy4) [113]. Kalihipyran B (Kpy3) isolated by Fusetani, again features a trans-decalin backbone, but contains a chlorine in the side chain [114]. The configuration at C-14 remains unknown.

Figure 21.

Kalihipyrans.

Figure 21.

Kalihipyrans.

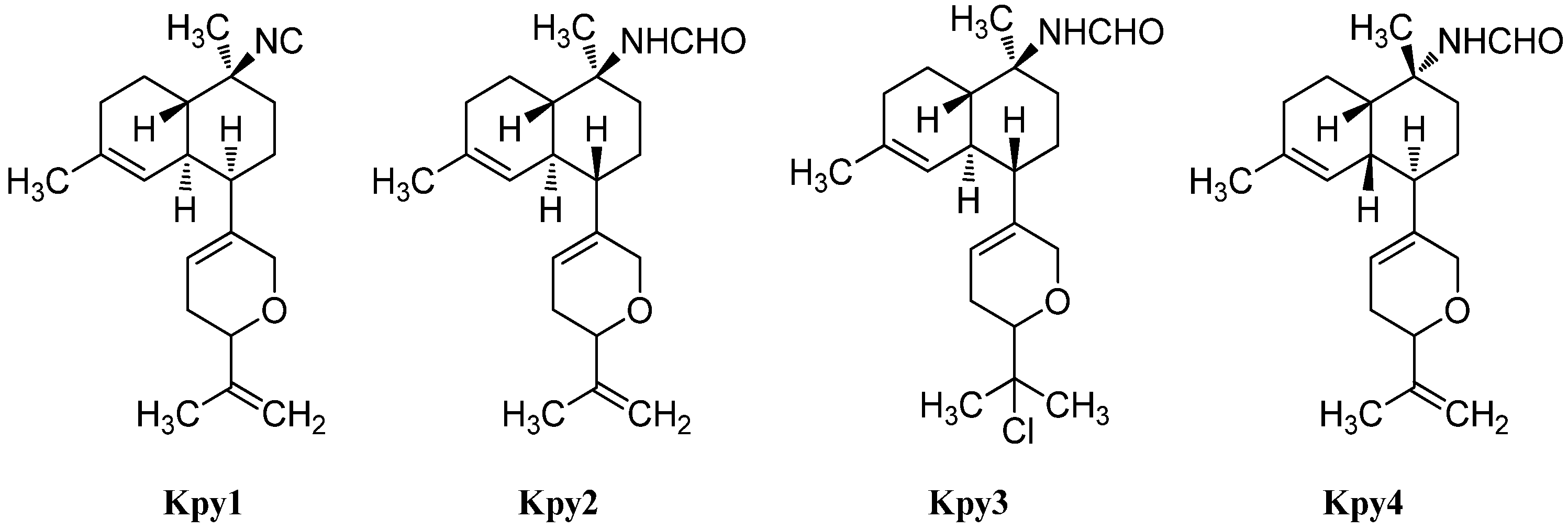

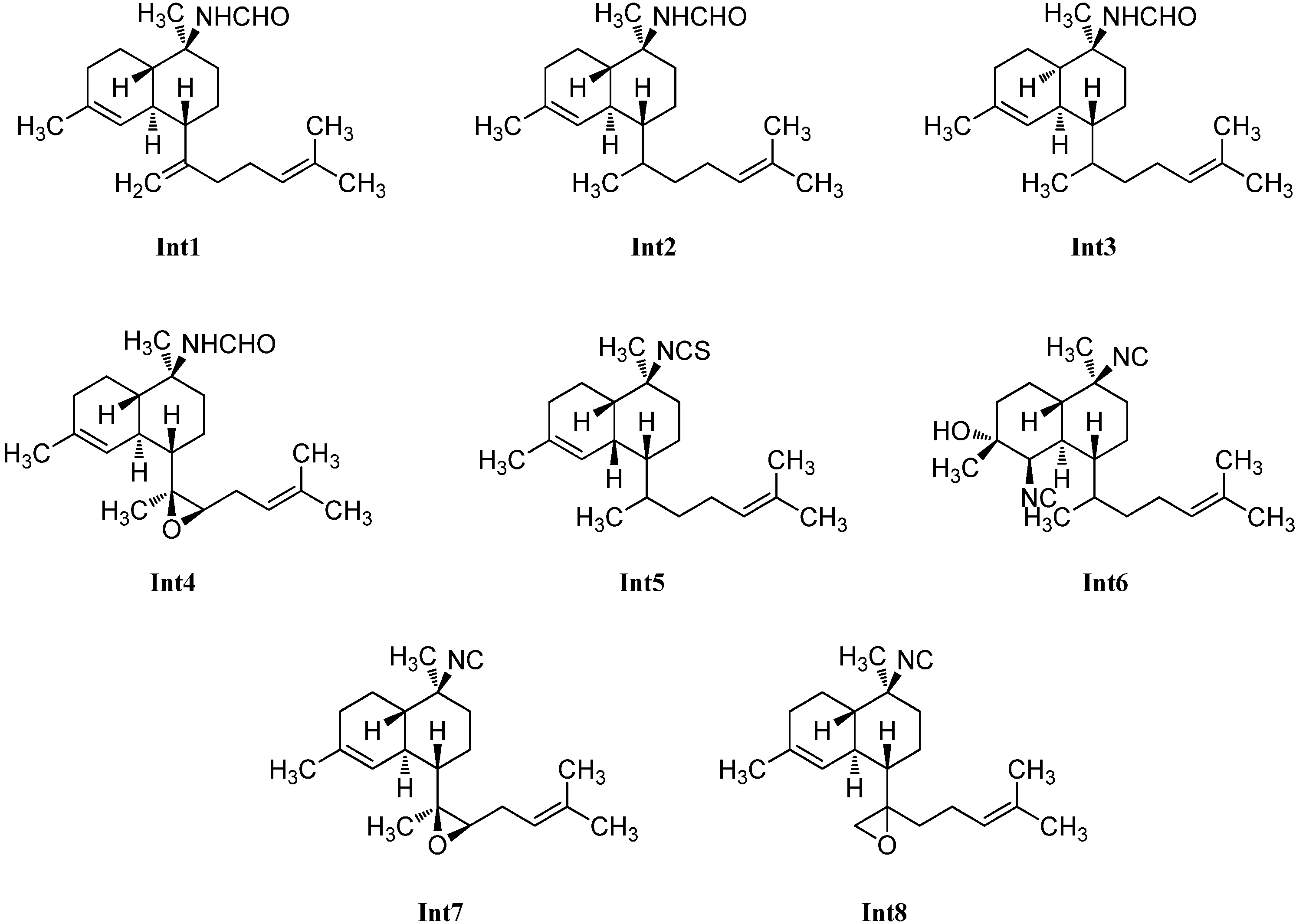

Cavernenes and Other Intermediates

Over the years, a couple of potential intermediates in the biosynthetic pathway of kalihinanes have been identified (Figure 22). In 1996, the first example of a new class of kalihinane diterpenes with an open-chained substituent at C-7 and a kalihinene cis-decalin framework was discovered in Cymbastella hooperi by König et al. who determined the relative configuration to correspond to that of (1S*,6R*,7R*,10S*,11R*)-10-isothiocyanatobiflora-1,14-diene (Int5) ([α]D = +45° (CHCl3, c = 0.26)) [115].

Figure 22.

Intermediates.

Figure 22.

Intermediates.

Already in 1992, a kalihinene derivative with an open isoprenoid side chain was isolated by Sharma et al. from a sample of Adocia sp. showing the same 2D structure but a different optical rotation ([α]D = +97° (CHCl3, c = 0.085)) compared to König’s compound [116]. Its relative configuration was not elucidated.

Examination of an A. cavernosa sponge, collected at Heron Island (Great Barrier Reef, Australia) by Clark et al. in 2000 resulted in the isolation of two oxirane-derivatives, 11,12-epoxy-10-isocyano-4,14-bifloradiene (Int7) possessing a trisubstituted epoxide in the side chain and a trans-decalin framework, and 11,18-epoxy-10-isocyano-4,14-bifloradiene (Int8) featuring a terminal epoxide group. The authors suggest the latter one to be a precursor to the kalihipyran ring system [31].

From the same sponge, four further members of this class of intermediates were reported by Xu et al. in 2012, which all bear a formamide group at C-10 and differ just in the nature of the side chain linked to C-7 and the cis- or trans-configuration of the decalin moiety. Cavernene A (Int1), a trans-decalin, is connected to an isoprenoid unit. In contrast to cavernene A (Int1), cavernene B (Int2) shows a monoolefinic isoprenoid side chain, while cavernene C (Int3) is identical to cavernene B (Int2) apart from the cis-decalin moiety. Cavernene D (Int4) possesses a trisubstituted epoxide in the side chain and the same trans-decalin unit as cavernenes A and B and represents the C-10-formamido derivative of Int7 [113].

The missing link in the kalihinol synthesis was discovered by Wolf et al. in 1998 in a sample of Phylidiella pulcherrima and was named pulcherrimol (Int6) [104]. In contrast to the other intermediates, it shows the decalin framework of kalihinol A, which makes its role as an intermediate in the biosynthesis of kalihinols plausible.

For the proposed role of the intermediates in the kalihinane synthesis see the Chapter 3 on biosynthesis.

2.2.3. Amphilectanes

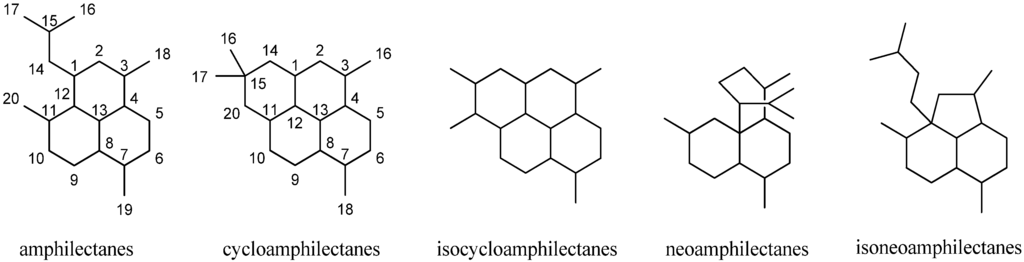

Besides the diterpenoid class of highly substituted decalins, the kalihinanes, which are found almost exclusively in A. cavernosa and apart from the small group of acyclic diterpenes, a third class of naturally occurring diterpenoid isonitriles with tricyclic or tetracyclic structures is known. These so-called amphilectanes are predominantly found in Amphimedon sp., Hymenacidon amphilecta and Halichondria sponges and can furthermore be subdivided based on their carbon frameworks into amphilectanes, cycloamphilectanes, isocycloamphilectanes, neoamphilectanes and isoneoamphilectanes (Figure 23). Recently the assignment of the species Hymeniacidon amphilecta has been revised to Pseudoaxinella amphilecta and will be referred to in the latter way hereinafter [117].

Figure 23.

Amphilectane frameworks.

Figure 23.

Amphilectane frameworks.

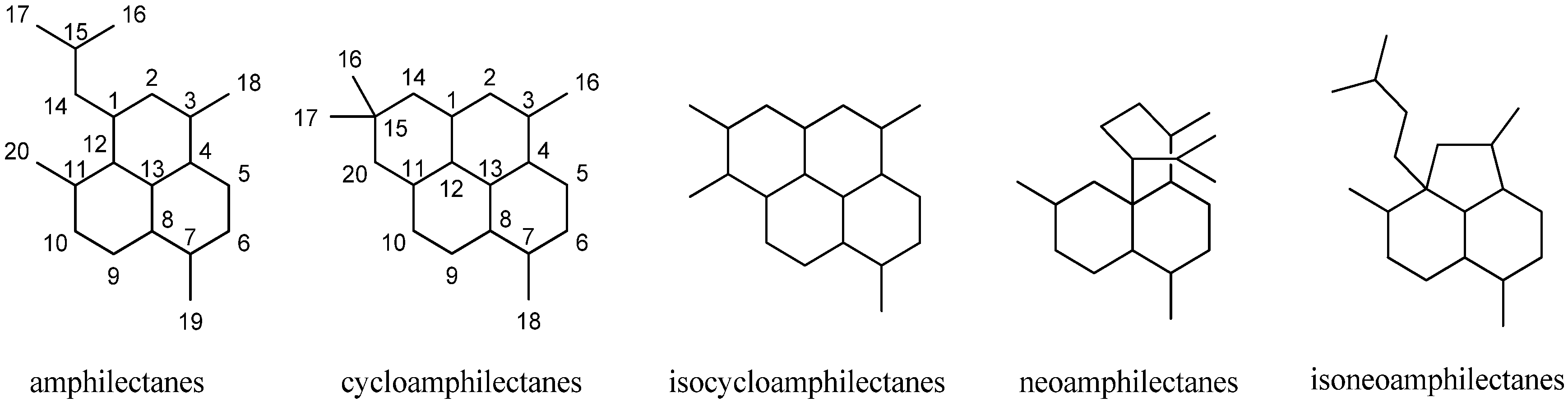

Amphilectenes

Examination of the Caribbean sponge Pseudoaxinella amphilecta by Wratten et al. in 1978 revealed a diterpenoid diisocyanide with a novel tricyclic carbon skeleton, 8,15-diisocyano-11(20)-amphilectene/((−)-DINCA) (Amp1) which became the lead substance of the new class of amphilectenes (Figure 24). It was shown later by Ciavatta et al. to reduce the proliferation of T and B lymphocytes [118]. In the same source, the goup around Wratten was also able to isolate its 15-formamide derivative Amp2 [119].

Figure 24.

Amphilectenes.

Figure 24.

Amphilectenes.

The corresponding 15-thiocyanato derivative Amp3 was isolated in 2005 from the unidentified Caribbean sponge Cribochalina sp. by Ciavatta et al., who also were able to assign the absolute configuration of several amphilectenes based on an investigation of Amp1 by a modification of Mosher’s method in 2005, revising a misassignment of the absolute configuration published in 1999 by the same group [118,120].

Further investigations of a Palauan sponge Halichondria sp. by Molinski et al. in 1987 resulted in the isolation of 8-isocyano-10,14-amphilectadiene (Amp5) bearing an isobutenyl side chain [121]. In 2004, Mitome et al. were able to find two double bond isomers (1S*,3S*,4R*,7S*,8S*,12S*,13S*)-8-isocyanato-amphilecta-11(20),14-diene (Amp4) and (3S*,4R*,7S*,8S*,11S*,13S*)-8-isocyanoamphilecta-1(12),14-diene (Amp6) in an unidentified Okinawan sponge Stylissa sp. taken from the coral reef of Iriomote Island (Japan) [50].

Another double bond isomer was identified in 2009 by Wattanapiromsakul et al. who were able to isolate 8-isocyanoamphilecta-11(20),15-diene (Amp7) from Ciocalapata sp. (family Halichondriidae), collected in Koh-Tao in the Surat-Thani province of Thailand [122].

Examination of the sponge Stylissa cf. massa, collected also in Koh-Tao (Thailand) by Chanthathamrongsiri in 2012 revealed two C-5 derivatives of Amp2, 8-isocyanato-15-formamidoamphilect-11(20)-ene (Amp8) and 8-isothiocyanato-15-formamidoamphilect-11(20)-ene (Amp9) [123].

The isolation of three unprecedented β-lactam amphilectenes was reported in 2010 and 2015 by Avilés et al. from a Puerto Rican Hymeniacidon sp. (Demospongiae) collected in Mona Island [124,125]. The absolute configuration of monamphilectine A (Amp10), B (Amp11) and C (Amp12) was assigned by semisynthesis starting from 8,15-diisocyano-11(20)-amphilectene/((−)-DINCA) (Amp1). Monamphilectines B and C bear a methyl and a methoxy group in α-position of the β-lactam and represent the first α-substituted β-lactams of marine origin.

Monoamphilectine A (Amp10) and Amp1 exhibited activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv with MIC values of 15.3 µg/mL and 3.2 µg/mL, respectively [124].

7-Isocyano-11(20),14-epiamphilectadien (Amp13) or (1R*,3S*,4R*,7S*,8S*,12S*,13S*)-7-isocyanoamphilecta-11(20),14-diene, isolated in 1980 by Kazlauskas from an Adocia species, was the first member of a series of amphilectanes bearing a 7-isonitrile substituent instead of a substituent at C-8 [126]. Its corresponding formamide (1R*,3S*,4R*,7S*,8S*,12S*,13S*)-7-formamidoamphilecta-11(20),14-diene (Amp14) was found in 2009 by Wright et al. in the tropical marine sponge Cymbastela hooperi (Kelso Reef, Queensland, Australia) [127]. Already in 1996, an examination of the same sponge by König et al. had revealed among others the presence of five new 7-substituted amphilectenes, the Δ11,12-double bond isomer of Amp13 (1R*,3S*,4R*,7S*,8S*,13R*)-7-isocyanoamphilecta-11,14-diene (Amp15), (1S*,3S*,4R*,7S*,8S*,12S*,13S*)-7-isocyano-amphilecta-10,14-diene (Amp18), the C-15 isothiocyanato exo-methylene derivative (1S*,3S*,4R*,7S*,8S*,12S*,13S*)-7-isocyano-15-isothiocyanatoamphilecta-11(20)-ene (Amp22), and (1R*,3S*,4R*,7S*,8S*,12R*,13R*)-12-hydroxy-7-isothiocyanato-amphilecta-11(20),14-diene (Amp20), an unprecedented natural product which still represents the only example of an amphilectane containing an oxygen-based functional group [115].

The (1S*,3S*,4R*,7S*,8S*,12S*,13S*)-7-isocyanoamphilecta-11(20),15-ene (Amp16) also isolated by König, is probably identical with the so-called 7-isocyano-11(20),15-epiamphilectadiene that was described by Kazlauskas et al. in 1980 with an undetermined configuration at C-1 [115,126]. From the same sample, Kazlauskas was able to isolate 7,15-diisocyano-11(20)-epiamphilectene (Amp21) again with an uncertain stereochemistry at C-11.

Further investigation of a sample of Stylissa sp. by Mitome et al. revealed the C-1-epimer of Amp18 (1R*,3S*,4R*,7S*,8S*,12S*,13S*)-7-isocyanoamphilecta-10,14-diene (Amp19), while examination of Cymbastela hooperi by Wright et al. in 2009 resulted in the discovery of the formamide-derivative of Amp16, (1S*,3S*,4R*,7S*,8S*,12S*,13S*)-7-formamidoamphilecta-11(20),15-diene (Amp17) [50,127].

X-ray structural analysis of amphilectene metabolites from an unidentified Cribochalina species by Ciavatta et al. in 2005 led to the discovery of three members of the amphilectane class with a rather unusual cis-ring junction between C-8 and C-13, 7,15-diisocyano-11(20)-amphilectene (Amp23), its C15 isothiocyanato derivative 7-isocyano-15-isothiocyanato-11(20)-amphilectene (Amp24), as well as the isobutenyl derivative (1S,3S,4R,7S,8R,12S,13S)-7-isocyanoamphilecta-11(20),15-diene (Amp25) which is the C-8-epimer of Amp16 [120].

In 2011, Lamoral-Theys et al. were able to reisolate compounds Amp1, Amp23 and Amp25 from the Caribbean sponge Pseudoaxinella flava from the Grand Bahamas along with a new representative with cis-junction Amp26. Amphilectenes Amp25 and Amp26 showed cytotoxic effects against the apoptosis-sensitive human PC3 prostate cancer cell line whereas Amp1 and Amp23 displayed cytostatic effects [128].

A putative precursor Amp27 of the amphilectene compounds with a biflora-4,9,15-triene skeleton was isolated by Hirota in 1996 [20]. The absolute configuration and a plausible biosynthetic pathway to the amphilectanes were reported in 2005 by Ciavatta [120].

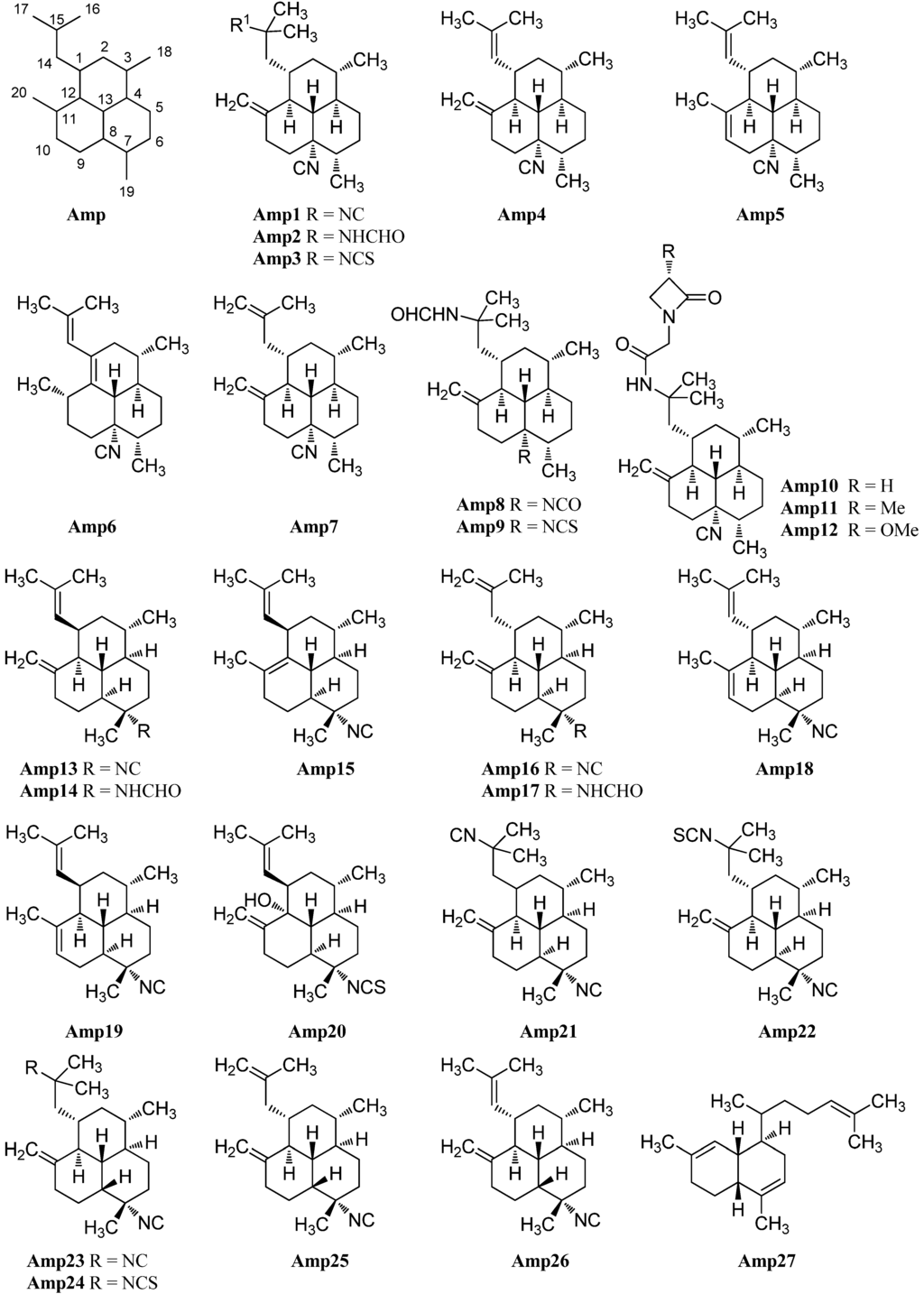

Cycloamphilectenes

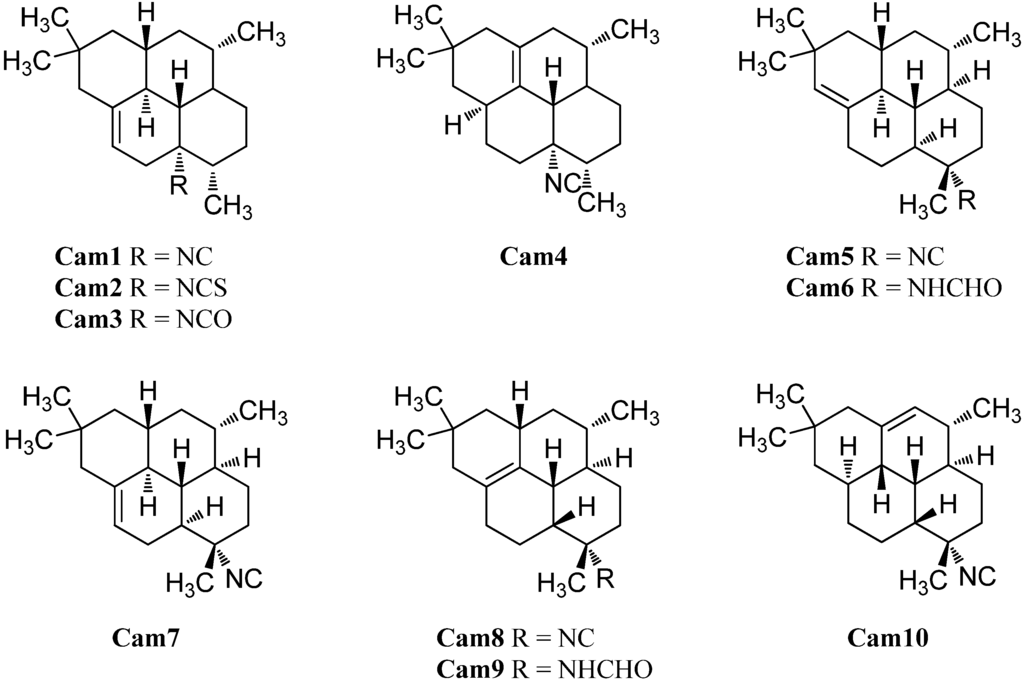

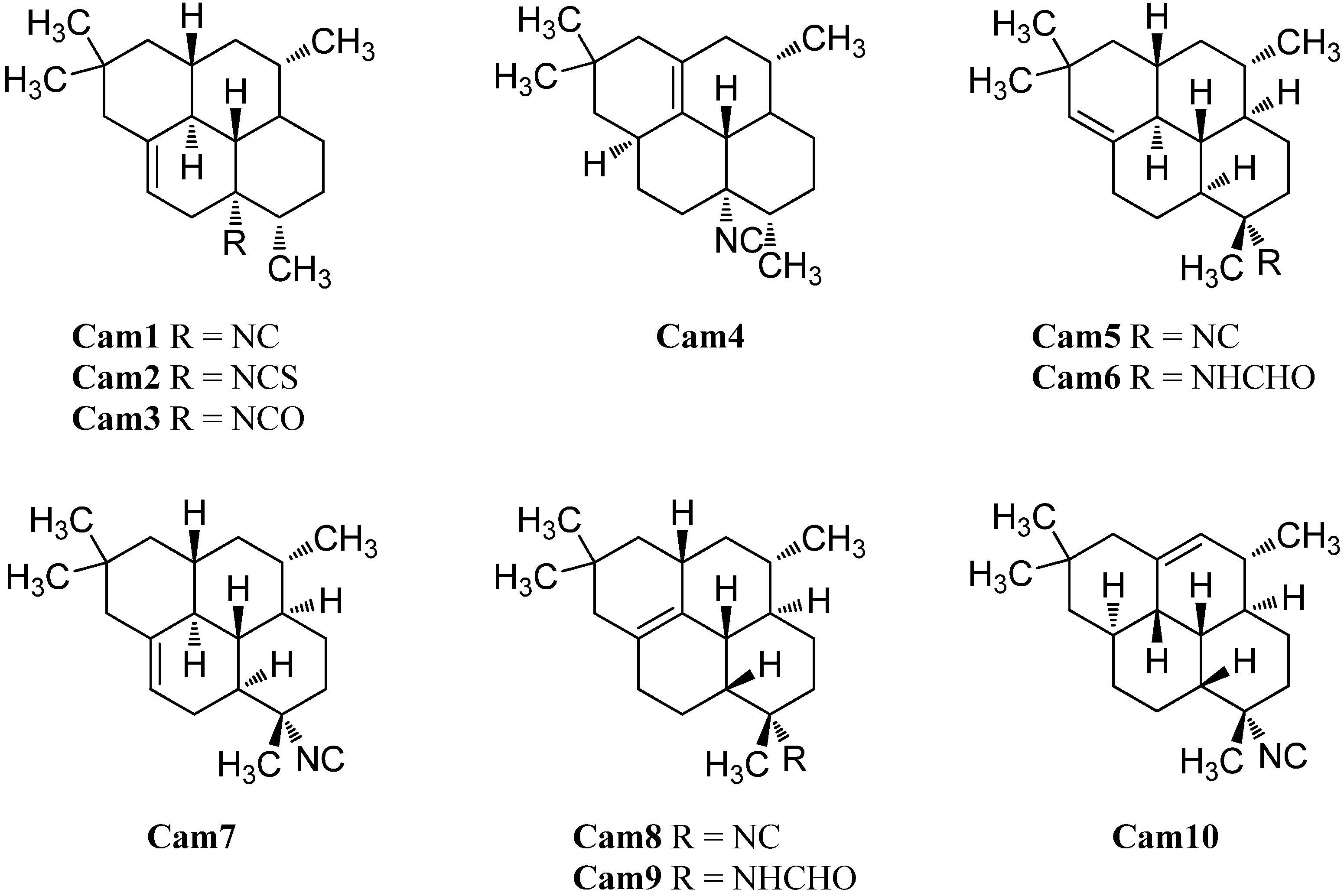

The first representative of the cycloamphilectanes (Figure 25), 8-isocyano-10-cycloamphilectene (Cam1) was isolated in 1980 by Kazlauskas et al. from an Adocia specimen [126]. The group also was able to detect traces of a second cycloamphilectane but due to the limited amount, the structure was initially misassigned. The correct relative configuration was reported in 1987 by Faulkner et al. who proved the compound to be (3S*,4R*,7S*,8S*,11S*,13R*)-8-isocyano-1(12)-cycloamphilectene (Cam4) after reisolation from a Palauan Halichondria specimen [121].

Figure 25.

Cycloamphilectenes.

Figure 25.

Cycloamphilectenes.

In 2004, investigation of the Okinawan sponge Stylissa sp. by Mitome et al. resulted in the isolation of the isocyanato and isothiocyanato derivatives of Cam1, 8-isocyanatocycloamphilect-10-ene (Cam3) and 8-isothiocyanato-amphilect-10-ene (Cam2) [50]. Their absolute configuration was determined by anomalous X-ray dispersion of the corresponding semisynthetic 8-p-bromobenzamide derivative to be 1S,3S,4R,7S,8S,12S,13S. Cycloamphilectanes Cam 2 and Cam3 and amphilectanes Amp6 and Amp18 displayed weak cytotoxicity towards HeLa cells showing IC50 values of 88.7 µg/mL, 38.3 µg/mL, 11.2 µg/mL, and 20.0 µg/mL, respectively [50].

In 1996, the group around König was able to identify two 8-isocyano cycloamphilectanes in a sample of C. hooperi, the (1S*,3S*,4R*,7S*,8S*,12S*,13S*)-7-isocyanocylcoamphilect-10-ene (Cam7) and the (1S*,3S*,4R*,7S*,8S*,12S*,13S*)-7-isocyanocycloamphilect-11(20)-ene (Cam5) [115]. The formamide derivative of the latter compound, (1S*,3S*,4R*,7S*,8S*,12S*,13S*)-7-formamidocycloamphilect-11(20)-ene (Cam6) was reported by Wright et al. in 2009 [127]. As for the amphilectenes, some members of the cycloamphilectenes with the uncommon 8,13-cis-junction are also known. The first two examples, (1S*,3S*,4R*,7S*,8R*,13R*)-7-isocyano-11-cycloamphilectene (Cam8) and (3S*,4R*,7S*,8R*,11S*,12R*,13S*)-7-isocyano-1-cycloamphilectene (Cam10) were revealed in 1987 by Molinski et al. during their investigations of a Palauan Halichondria species [121]. In 2002, Ciasullo et al. were able to find the (1S*,3S*,4R*,7S*,8R*,13R*)-N-formyl-7-amino-11-cycloamphilectene (Cam9) in a sample of Axinella sp. from Vanuatu [129].

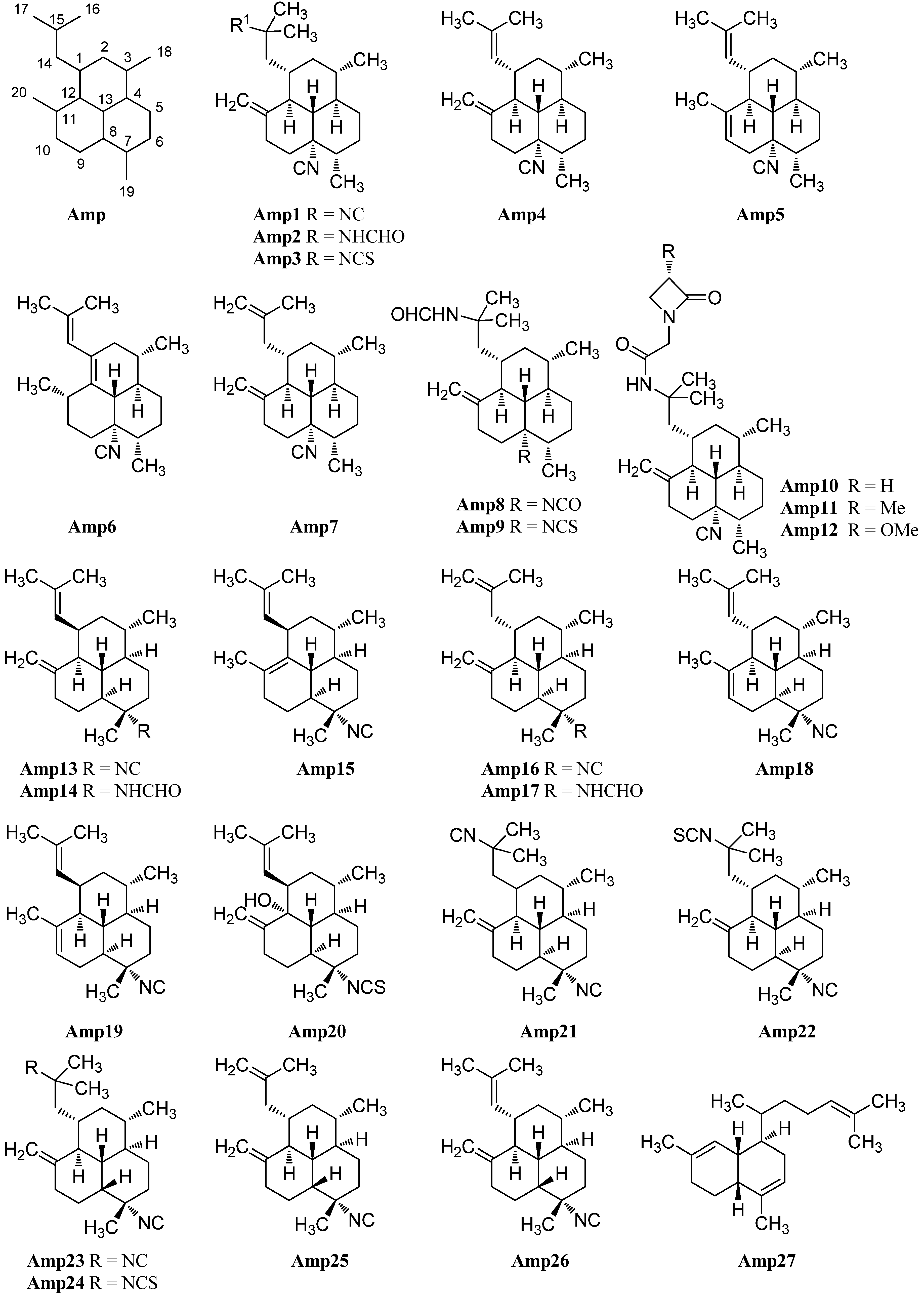

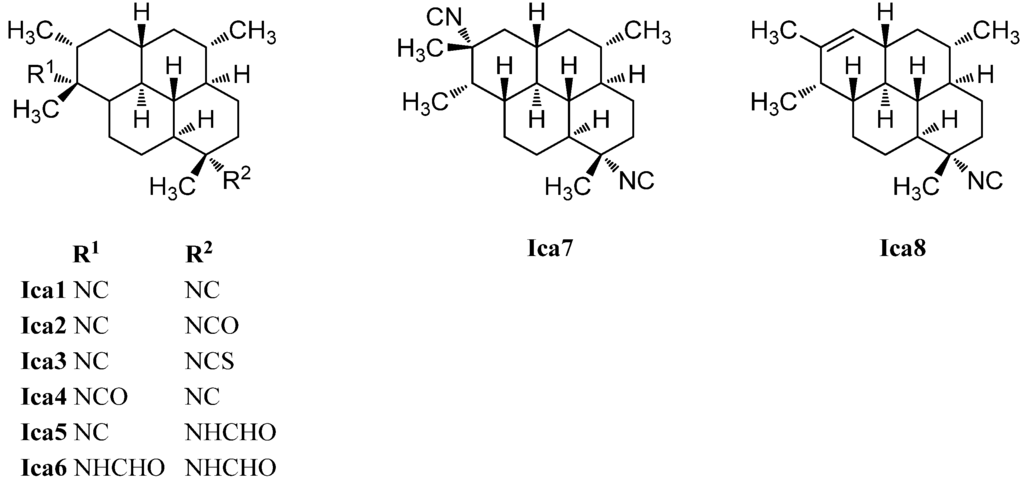

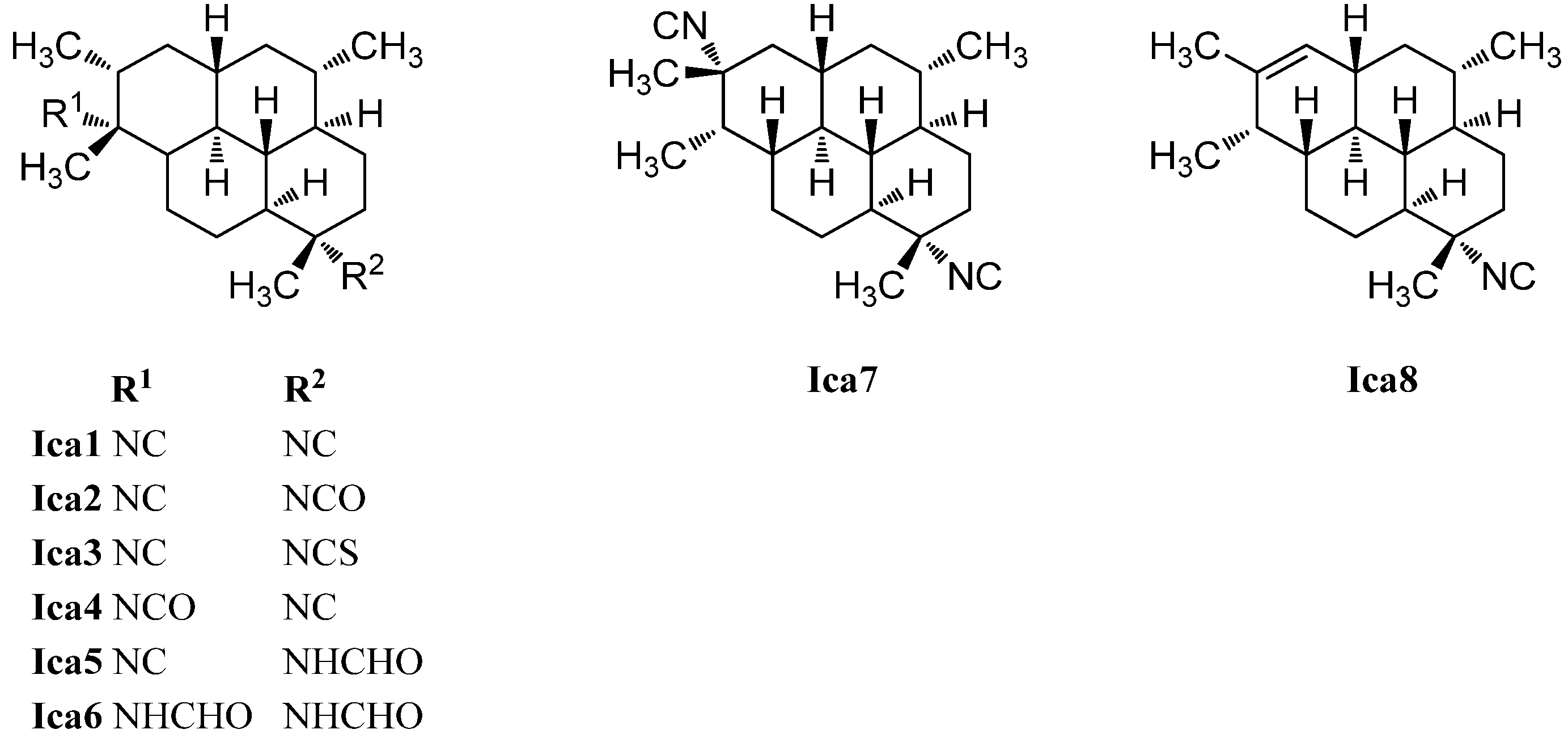

Isocycloamphilectanes

The first representative of the isocycloamphilectenes (Figure 26), which could be derived from amphilectene or cycloamphilectene precursors by a formal single methyl shift [126], was diisocyanoadociane or (1S,3S,4R,7S,8S,11S,12S,13S,15R,20R)-7,20-diisocyanoisocycloamphilectane (Ica1), isolated already in 1976 by Baker from a sponge species of the genus Adocia (Great Barrier Reef, Townsville, Australia) [130]. Its absolute configuration was determined in 1988 by Fookes via X-ray analysis of its p-bromobenzamide derivative and was additionally proven by total synthesis (Corey 1987) [131,132]. The mono- and diformamido derivatives (1S,3S,4R,7S,8S,11S,12S,13S,15R,20R)-7-formamido-10-isocyanoisocycloamphilectane (Ica5) and (1S,3S,4R,7S,8S,11S,12S,13S,15R,20R)-7,20-diformamidoisocycloamphilectane (Ica6) were found by Wright in 2009 in a sample of Cymbastela hooperi [127]. Examination of the same species thirteen years earlier by König et al. resulted in the isolation of the isocyanato compounds (1S,3S,4R,7S,8S,11S,12S,13S,15R,20R)-20-isocyano-7-isocyanatoisocycloamphilectane (Ica2) and (1S,3S,4R,7S,8S,11S,12S,13S,15R,20R)-20-isocyanato-7-isocyanoisocycloamphilectane (Ica4) and the isothiocyanato derivative (1S,3S,4R,7S,8S,11S,12S,13S,15R,20R)-20-isocyano-7-isothiocyanatoisocycloamphilectane (Ica3) [115]. Apart from these, the group was also able to identify the monoolefinic derivative (1S*,3S*,4R*,7S*,8S*,11R*,12R*,13S*,20S*)-7-isocyanoisocycloamphilect-14-ene (Ica8).

Figure 26.

Isocycloamphilectanes.

Figure 26.

Isocycloamphilectanes.

One example of an isocycloamphilectane with a different substitution pattern at C-15 and C-20 is known, the diisocyano compound 7,15-diisocyanoadociane (Ica7), isolated in 1980 by Kazlauskas [126,130].

Neoamphilectene

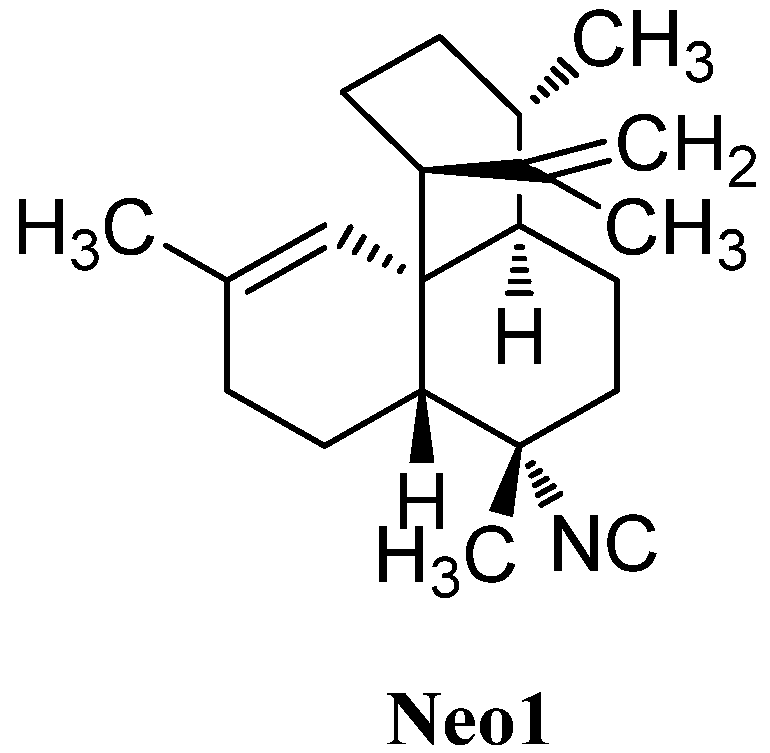

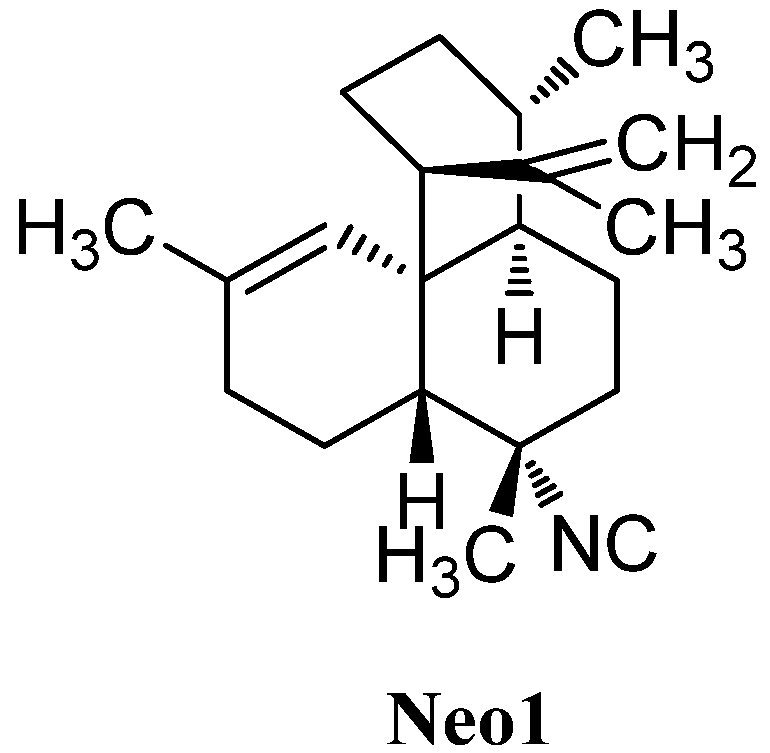

In 1992, a compound with an unusual amphilectane-framework in which ring C is spirocyclic to the cyclohexene ring was found by Sharma in a sponge of the Adociae family, collected off the island of Miyako (Japan, Figure 27). To date 7-isocyanoneoamphilecta-11,15-diene (Neo1) remains the only known representative of its class [116].

Figure 27.

Neopamphilectene.

Figure 27.

Neopamphilectene.

Isoneoamphilectenes

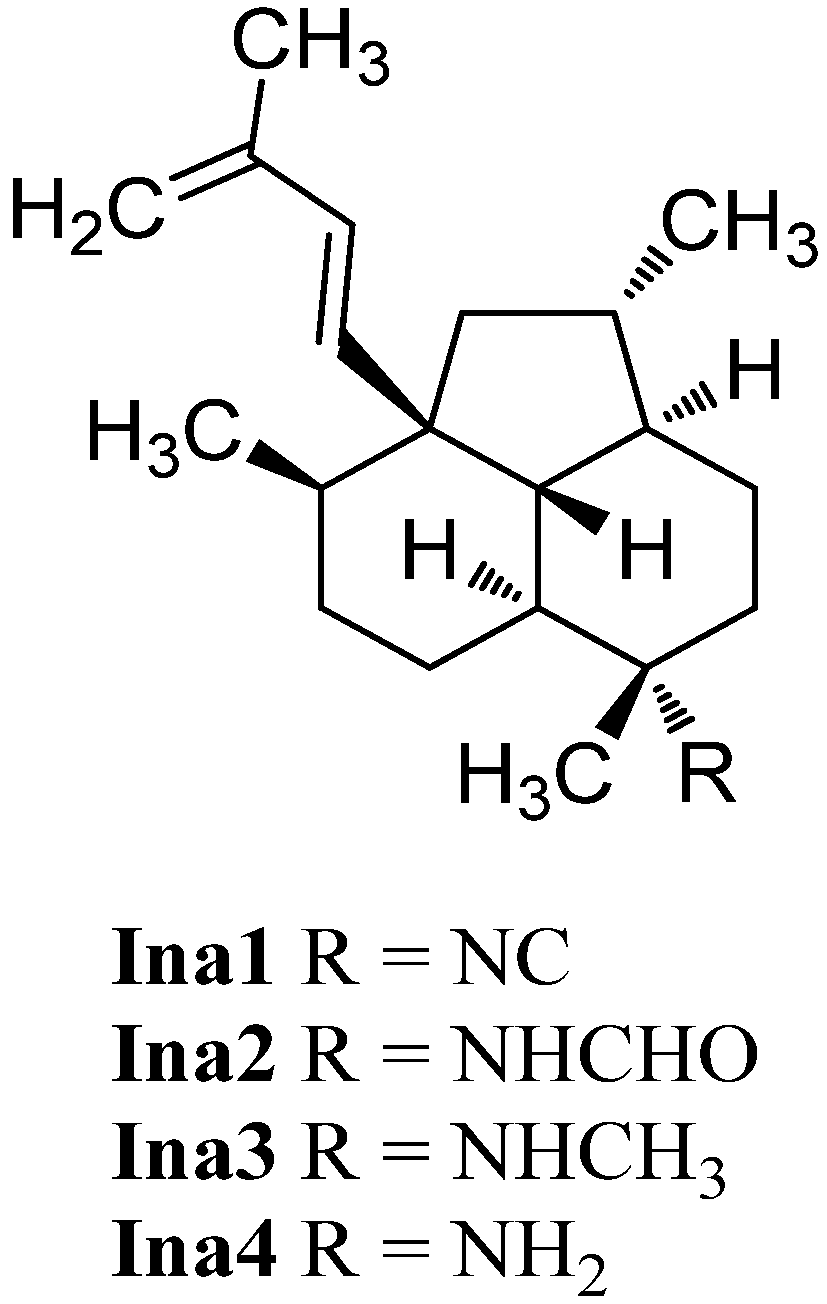

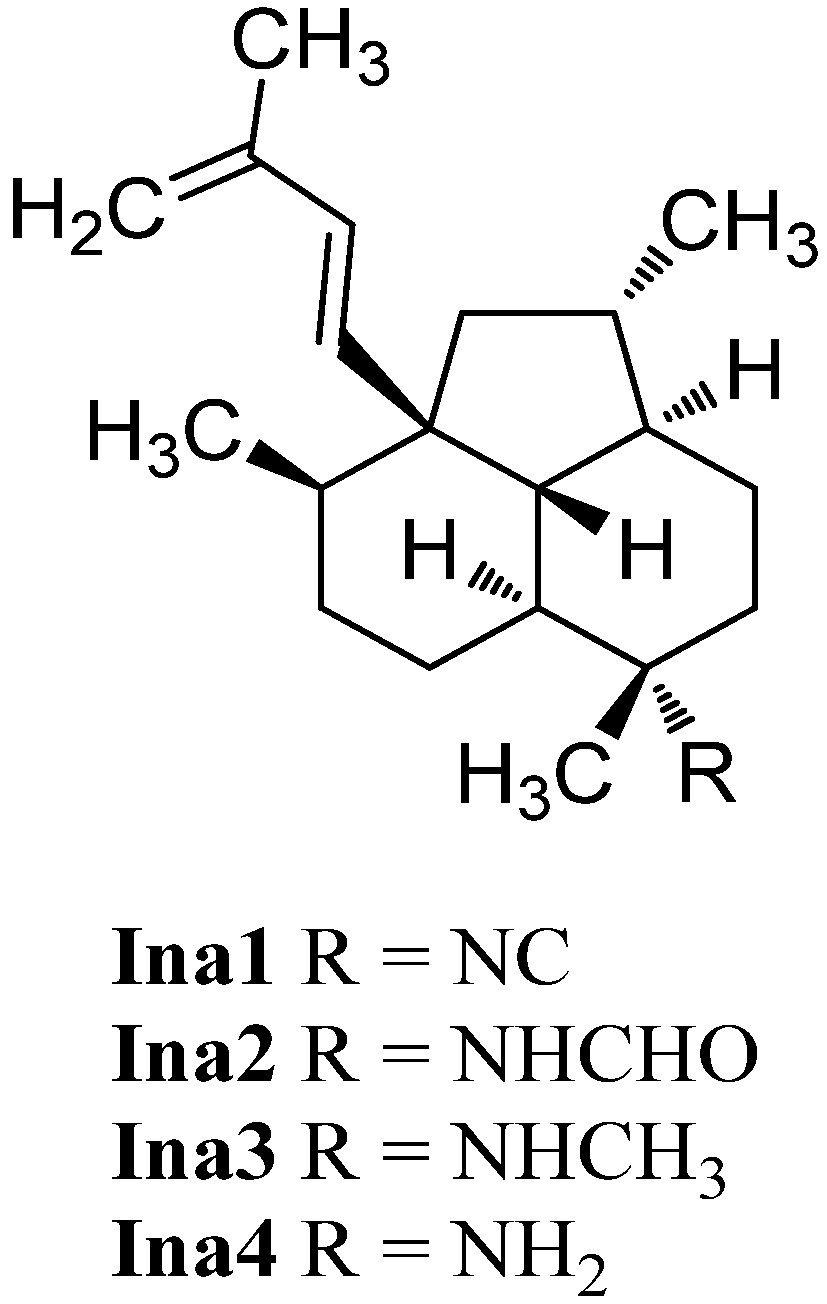

In 1996, examination of C. hooperi by König et al. revealed the unique tricyclic diterpene 7-isocyanoneoamphilecta-1(14),15-diene (Ina1, Figure 28) [115]. It was not before 2013 that Avilés et al. were able to identify two further members of this class, the formamide derivative 7-formamidoisoneoamphilecta-1(14),15-diene (Ina2) and the unusual N-methyl derivative 7-methylaminoisoneoamphilecta-1(14),15-diene (Ina3) in extracts of the Caribbean sponge Svenzea flava collected in Great Inagua Island, Bahamas [133]. Avilés et al. were able to determine the absolute configuration of these natural products to be (3S,4R,7S,8S,11R,12S,13R) by VCD-spectroscopy and DFT-calculations of the semisynthetic NH2-derivative Ina4.

Figure 28.

Isoneoamphilectenes.

Figure 28.

Isoneoamphilectenes.

Isoneoamphilectenes Ina1, 2, 3 and the semisynthetic Ina4 demonstrated strong growth inhibition potency against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv (MIC = 8 µg/mL, 15 µg/mL, 32 µg/mL and 6 µg/mL, respectively) [133].

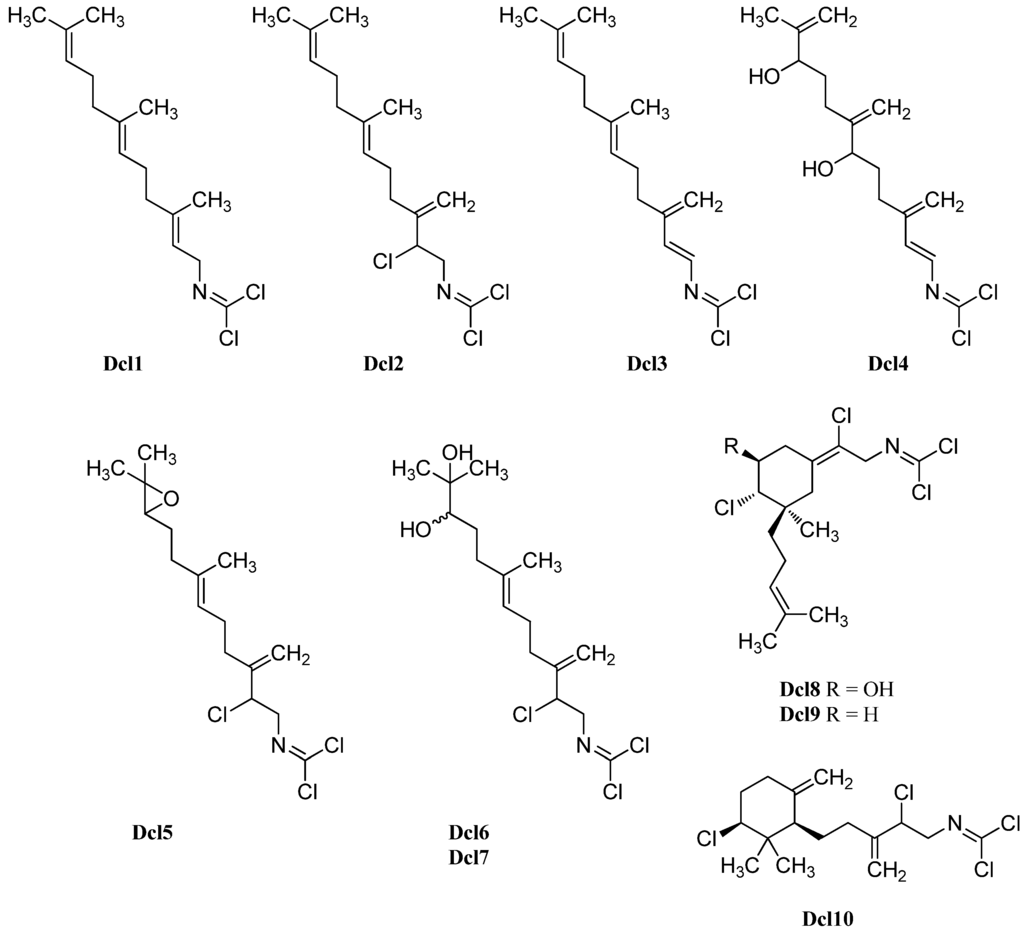

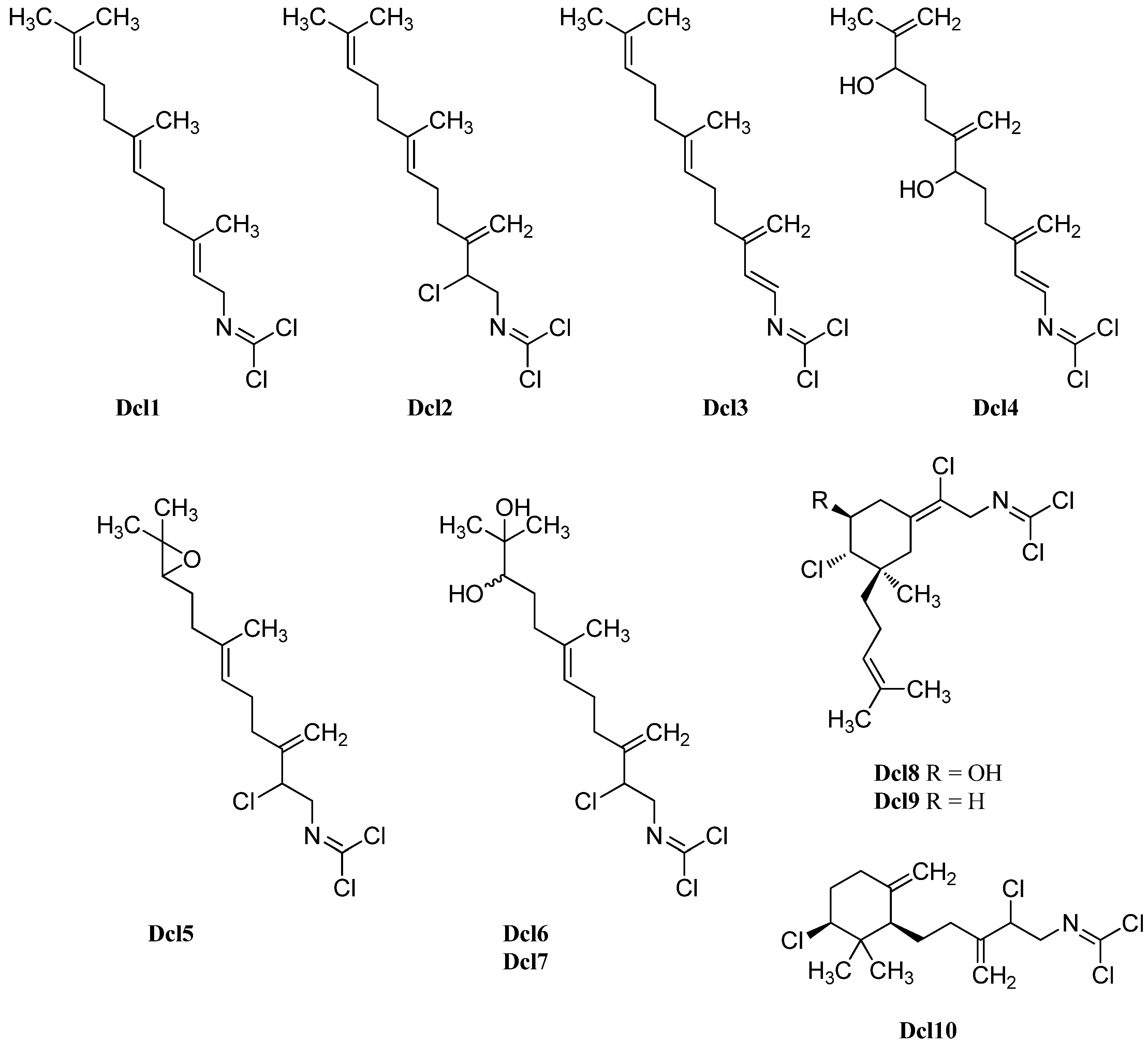

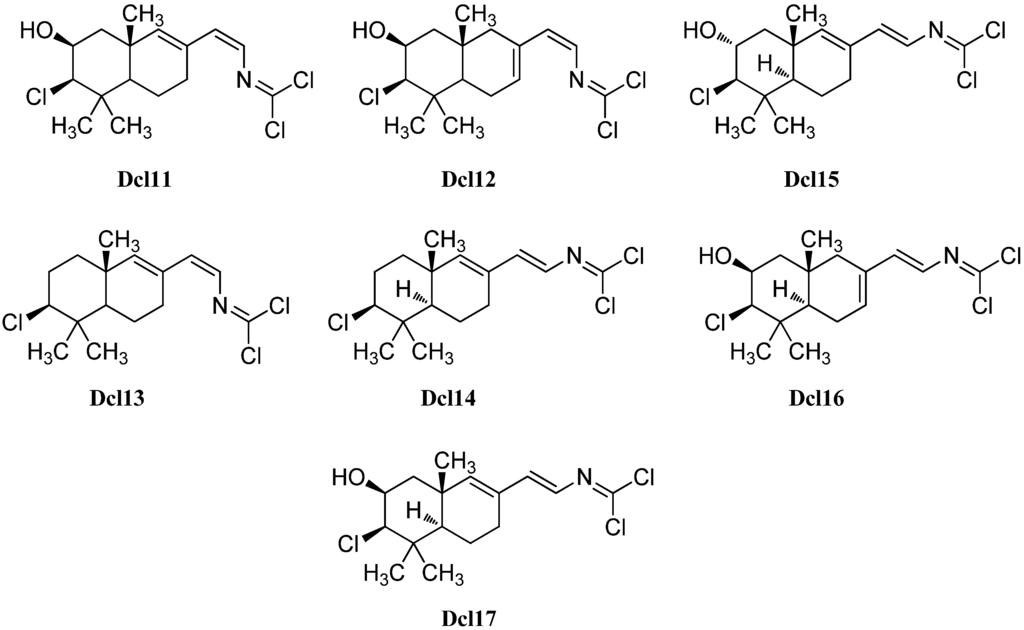

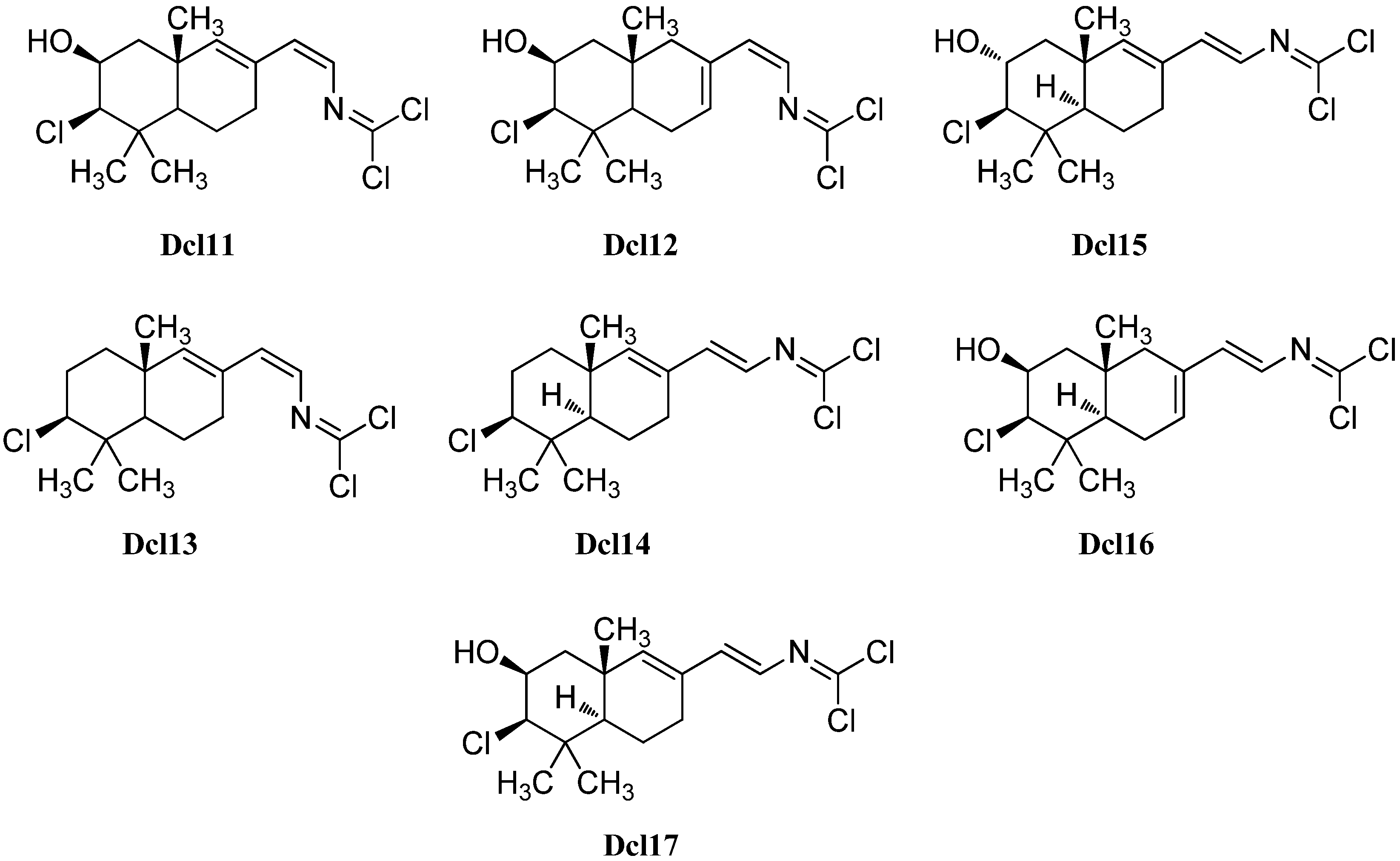

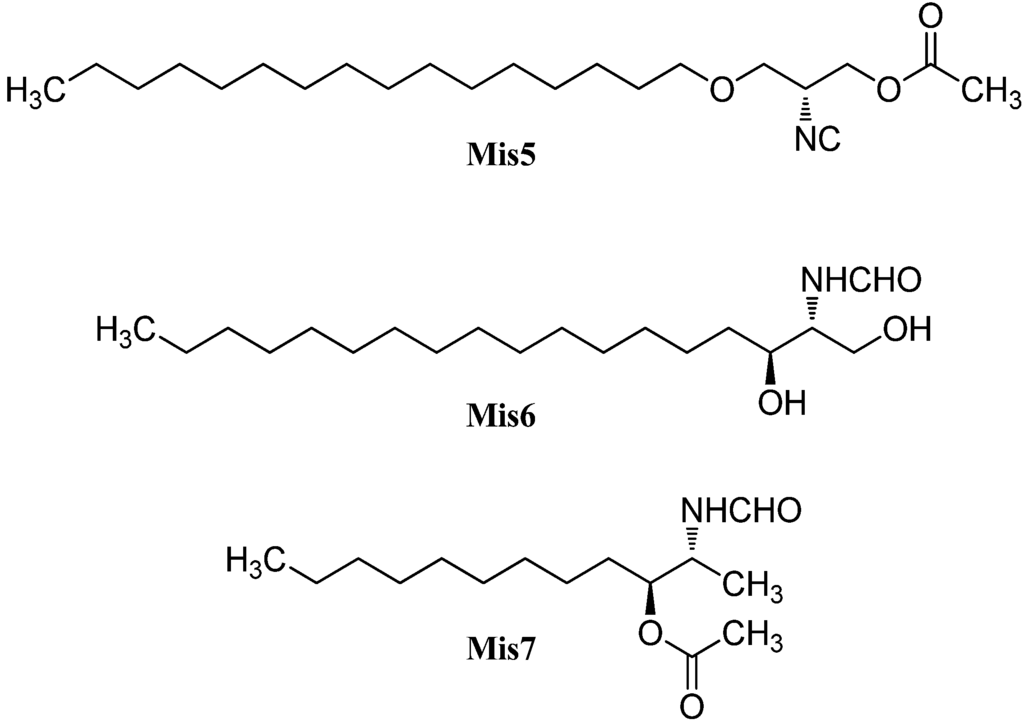

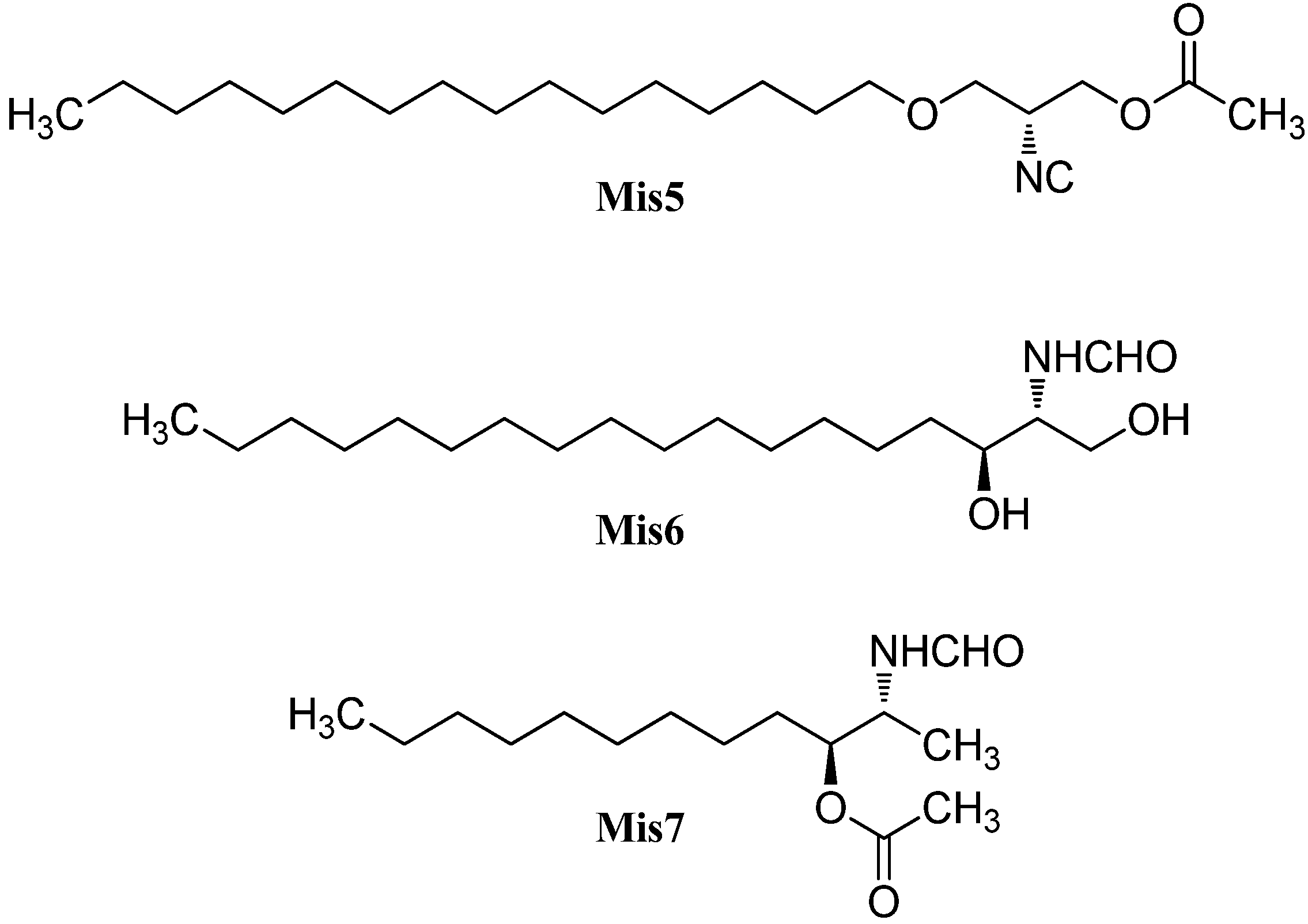

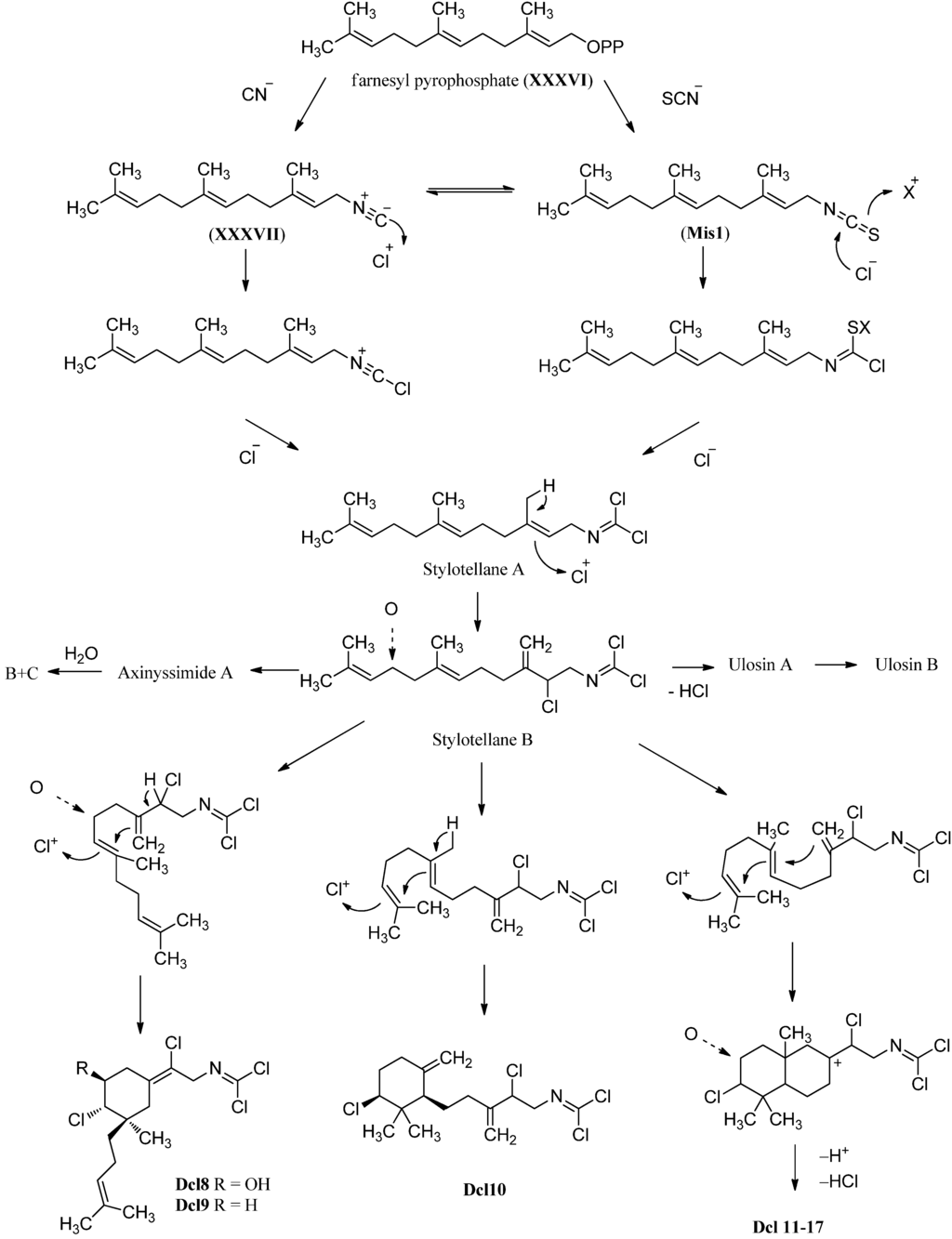

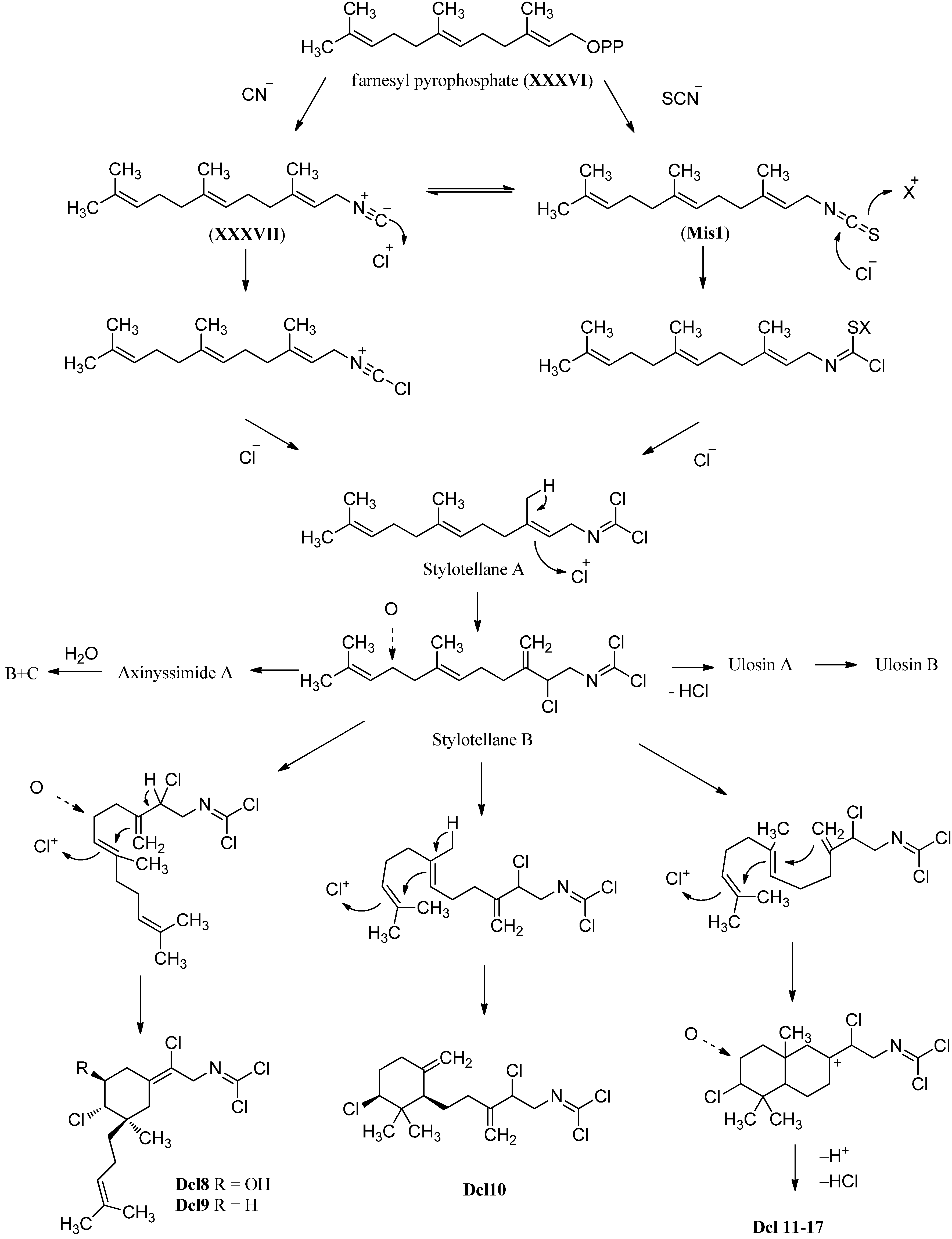

2.3. Carbonimidic Dichlorides

Carbonimidic dichlorides or dichloroimines represent a rare group of natural products of which to date only 16 representatives are known which are all of marine origin (Figure 29 and Figure 30). They have been isolated from four marine sponges (Pseudaxinyssa pitys, Axinyssa sp., Stylotella aurantium and Ulosa spongia) and from the nudibranch Reticulidia fungia presumably feeding on these sponges. Carbonimidic dichlorides exhibit a strong IR absorption at ~1650 cm−1 and a low intensity 13C signal at δ ≈ 127 ppm and can therefore be unequivocally identified.

The first examples of this class of natural products were isolated in 1977 from the Indo-pacific marine sponge Pseudoaxinyssa pitys by Wratten, who identified the trans linear isoprenoid derivative Dcl2 containing three chlorines [134]. The substance was isolated again in 1997 by Simpson from Stylotella aurantium, a tropical marine sponge collected at Heron Island (Great Barrier Reef, Australia), and was named stylotellane B (Dcl2) [135]. The sponge also contained farnesyl isothiocyanate (Mis1) and Stylotellane A (Dcl1), a similar sesquiterpene without the chlorine substituent at C-2. Both stylotellanes were testet against tumor cell line P-388, however only a weak activity was observed for stylotellane B (Dcl 2).

Investigation of the Australian sponge Ulosa spongia collected at Wistari Reef (Great Barrier Reef, Australia) by König et al. in 2001 revealed the presence of ulosin A (Dcl3) which could be obtained from stylotellane B (Dcl2) by formal elimination of HCl and ulosin B (Dcl4) bearing three exo-methylene groups and two hydroxy groups at C-6 and C-10 [136]. Ulosin A was found independently from König in the same year also by Musman et al. in Okinawan Stylotella aurantium [137].

Figure 29.

Acyclic and monocyclic carbonimidic dichlorides.

Figure 29.

Acyclic and monocyclic carbonimidic dichlorides.

Figure 30.

Bicyclic carbonimidic dichlorides.

Figure 30.

Bicyclic carbonimidic dichlorides.

Examination of a marine sponge of the genus Axinyssa collected off Hachijo-jima Island (Japan) by Hirota et al. in 1998 led to the isolation of three new oxygenated sesquiterpenoid carbonimidic dichlorides [53]. Axinyssimide A (Dcl5) represents the 10,11-epoxy derivative of stylotellane B while axinyssimides B (Dcl6) and C (Dcl7) turned out to be the 10,11-dihydroxy derivatives resulting from a ring-opening of the oxirane moiety. Axinyssimides B and C, differing in magnitude and sign of their optical rotation, are diastereomers. All three compounds demonstrated potent antifouling activities against the cypris larvae of the acorn barnacle Balanus amphitrite with an IC50 value of 1.2 µg/mL for axinyssimide A, 70% inhibition at a concentration of 0.5 µg/mL for axinyssimide B and 90% inhibition at the same concentration for axinyssimide C respectively [53].

Apart from stylotellane B, the investigation of Pseudoaxynissa pitys in 1977 by Wratten also revealed a monocyclic sesquiterpene containing the carbonimidic dichloride functionality [134]. This (1R*,5S*,6S*)-6,14-dichloro-5-hydroxy-9,3(14)-(Z)-axinyssadien-15yl-carbonimidic dichloride (Dcl8) was the first representative of a natural product with an axinyssane framework. In 2004, a second example without hydroxy goup at C-5 (Dcl9) was discovered by Brust et al. [138].

Another monocyclic carbonimidic dichloride (Dcl10) was isolated in 2001 by Musman et al. from Stylotella aurantium collected from a coral reef of Iriomate Island (Okinawa, Japan) [137]. Both monocyclic carbon skeletons can be derived from Stylotellane B by an enzymatic chlorination including a formal "chloronium ion" initiated cyclization [139].

Further examination of the Pseudoaxinyssa pitys saple of Wratten in 1978 also revealed four examples of bicyclic sesquiterpenes with carbonimidic dichloride functionality [140]. Compound Dcl11, its Δ7,8-double bond isomer Dcl12 and the non-hydroxylated derivative Dcl13 all show a Z-configurated Δ14-double bond in the side chain. The fourth isolated isomer, isoreticulidin B (Dcl17) showing a Δ7,8-14(E)-diene system, was also found in the nudibranch Reticulidia fungia collected at Irabu Island (Okinawa) in 1999 by Tanaka et al. besides a monocyclic (Dcl8) and two bicyclic compounds that were named reticulidins A (Dcl15) and B (Dcl16) [141]. In 2001, Musman et al. were able to determine the absolute configuration of reticulidin A by a modification of Mosher’s method to be 2R,3R,5S,10S [137]. The same group also revealed the structure of the non-hydroxylated derivative Dcl14 of reticulidin A and isoreticulidin B isolated from Stylotella aurantium.

Dcl10 and Dcl14 exhibited moderate cytotoxicity showing IC50 values of 0.1–1 µg/mL against the tumor cell lines P-388, A549, HT29 and MEL28 [137]. Furthermore, reticulidins A (Dcl15) and B (Dcl16) showed moderate cytotoxic potency against KB cells (IC50 0.41 and 0.42 µg/mL) and L1210 cells (0.59 and 0.11 µg/mL) [141].

2.4. Other Marine Isonitriles and Related Compounds (Miscellaneous Structures)

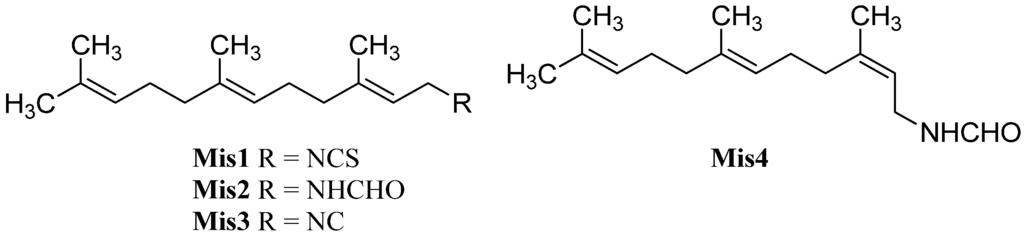

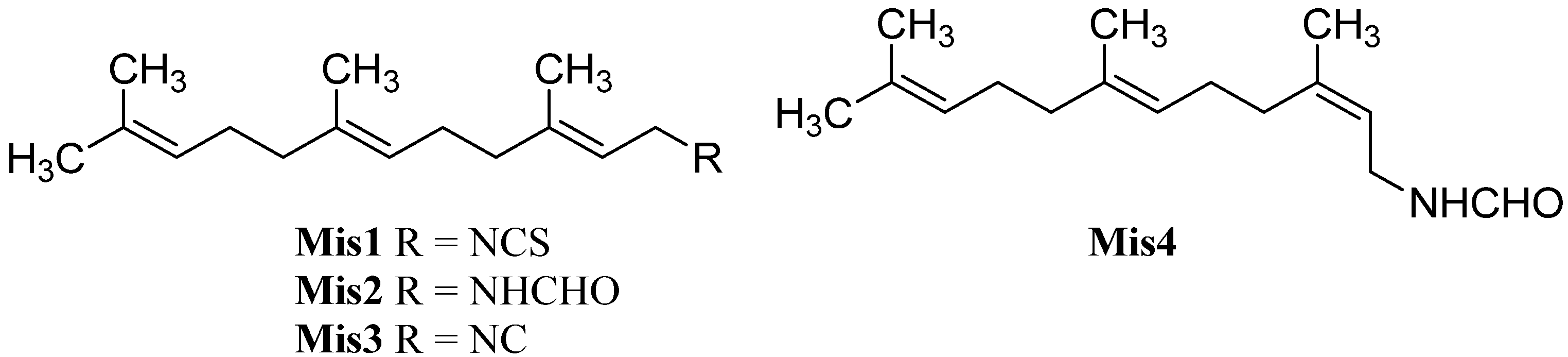

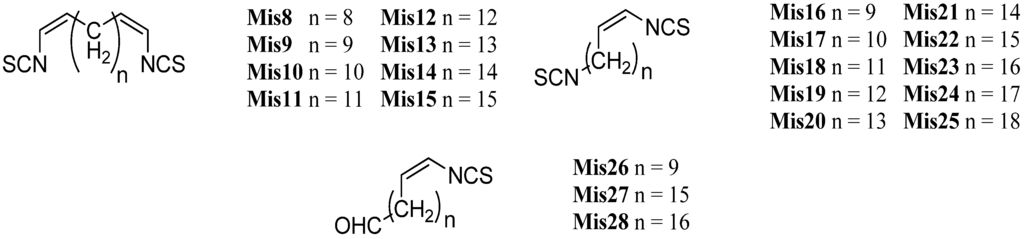

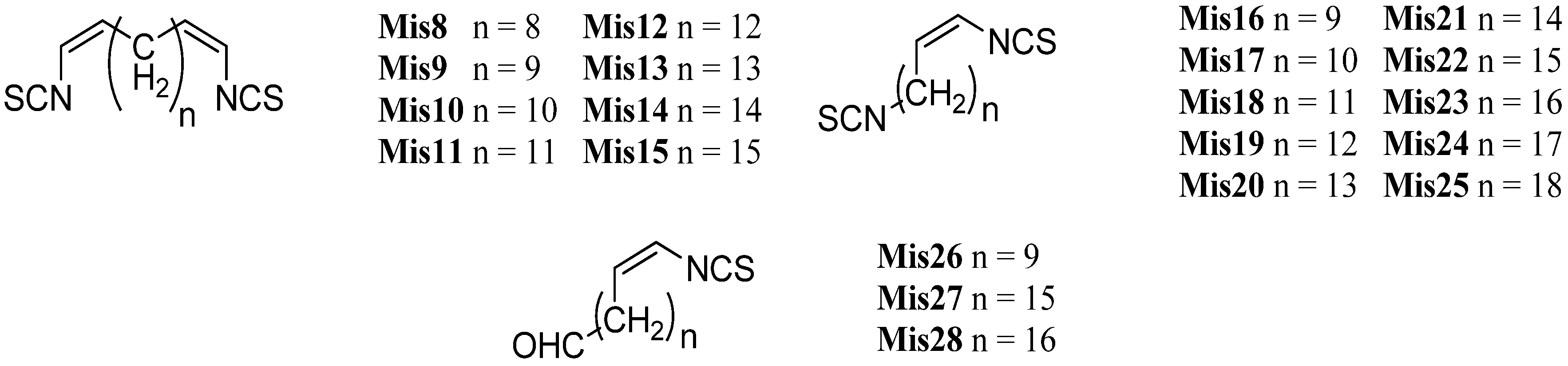

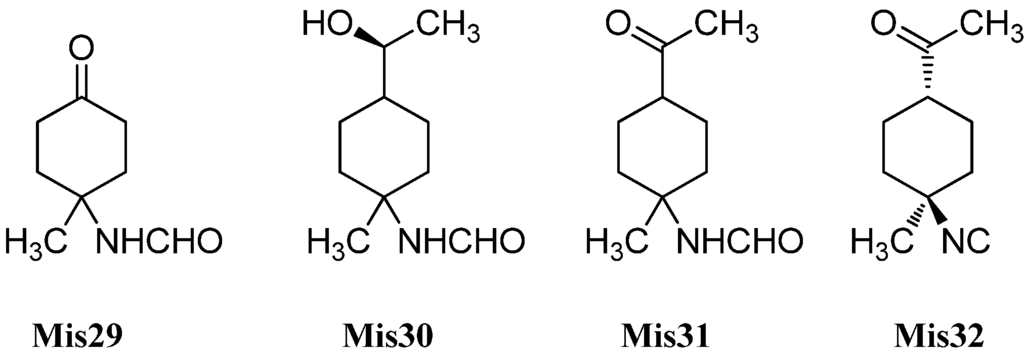

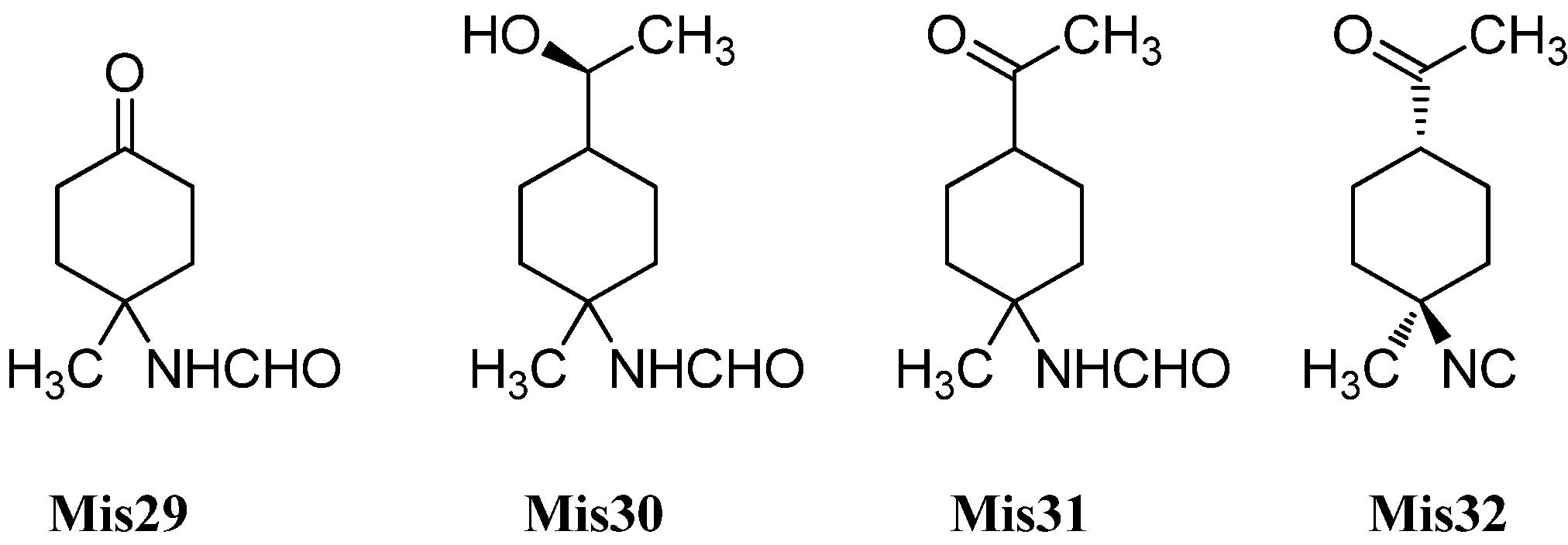

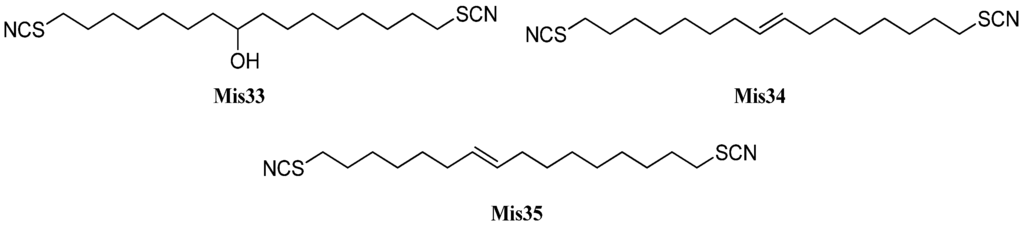

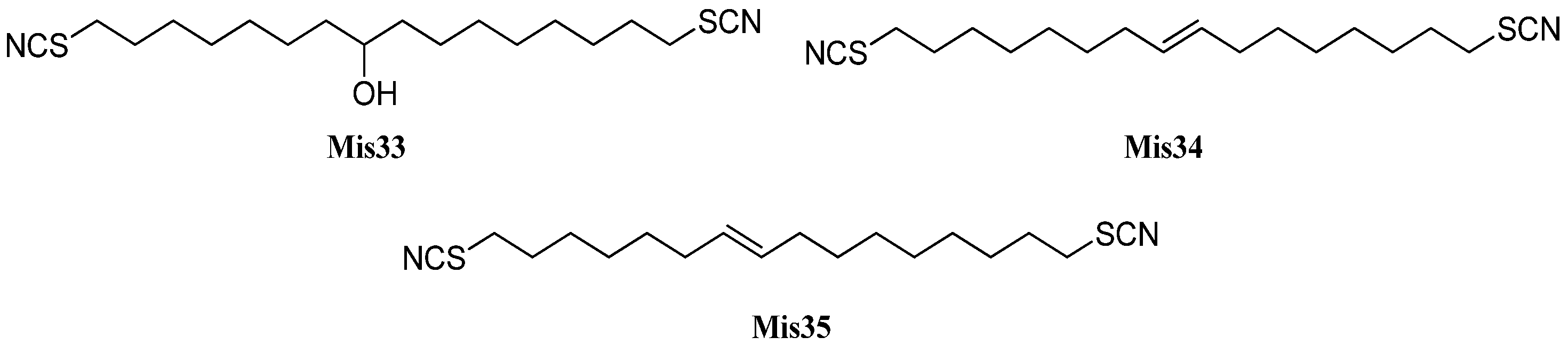

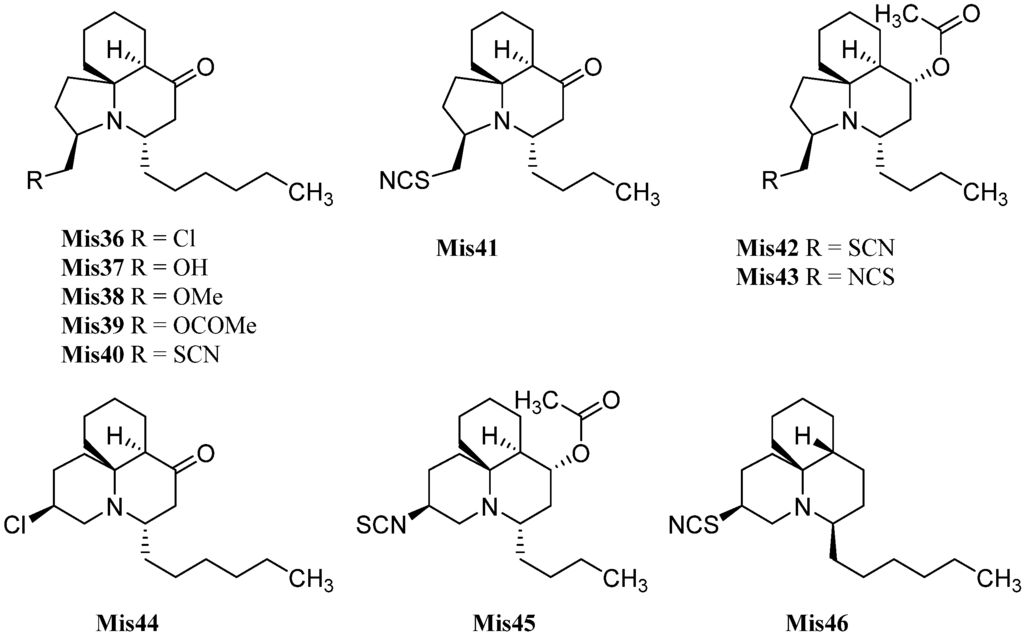

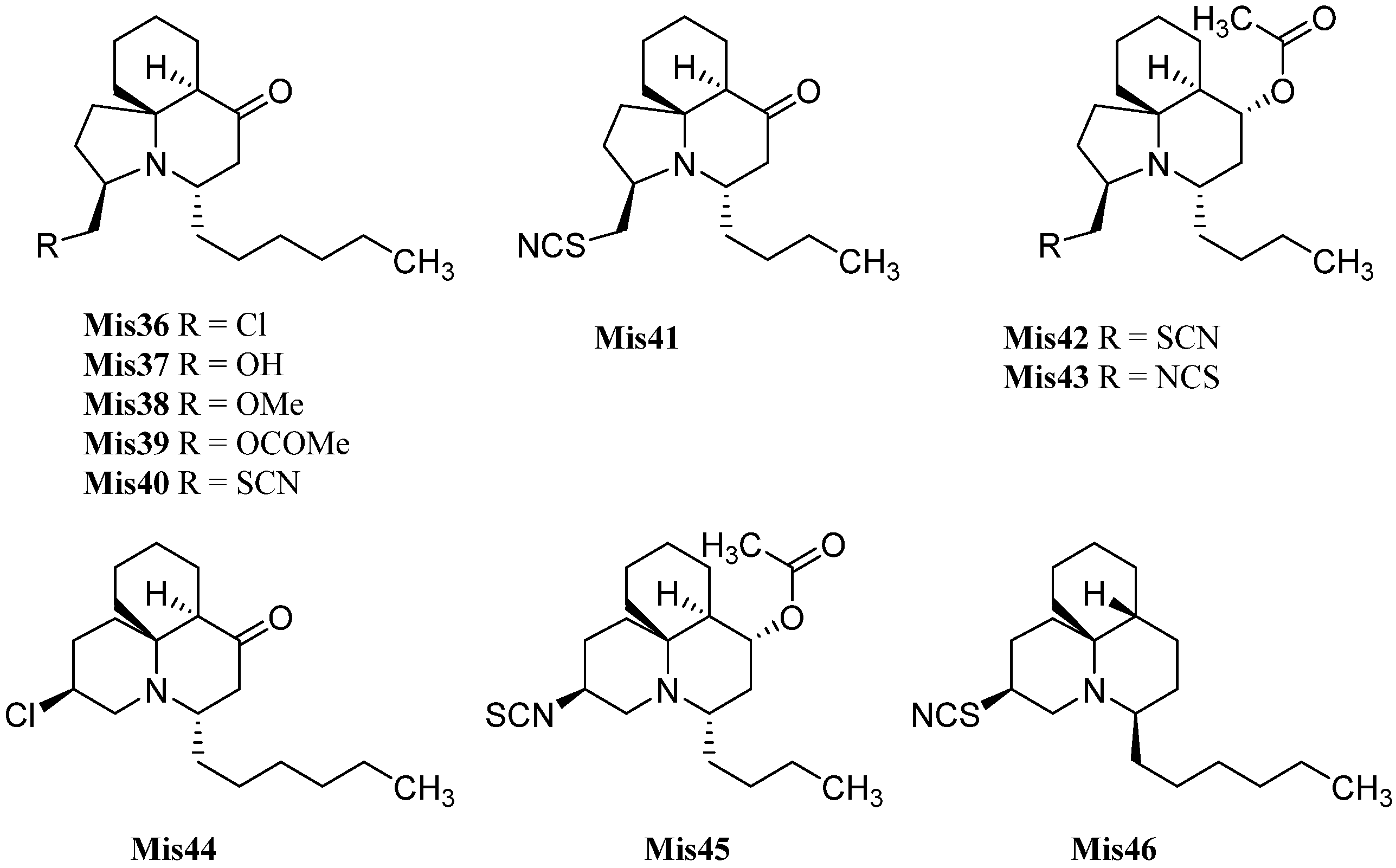

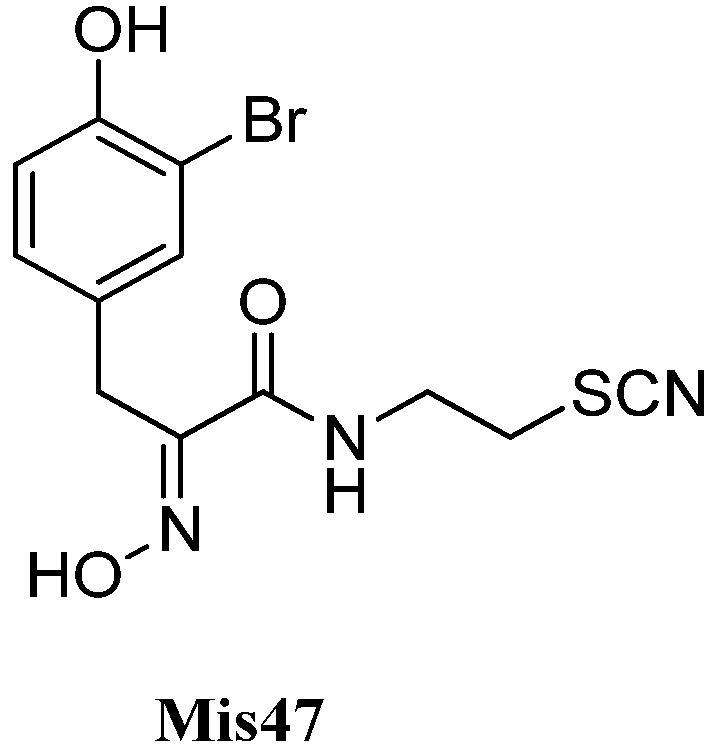

Among the isonitriles, isothiocyanates, and formamides of marine origin there are compounds that cannot be categorized in the structural families already presented (Figure 31).

Figure 31.

Farnesyls.

Figure 31.

Farnesyls.

Farnesylisothiocyanate (Mis1), an intermediate in the biosynthetic pathway of many sesquiterpene-isothiocyanates, was isolated in 1997 by Simpson from Stylotella aurantium [135,140]. Its corresponding formamide Mis2 and isofarnesyl formamide (Mis4) were found in 2008 in Axinyssa sp. collected in Sanya, Hainan Province, China by Li [84]. Until now, farnesyl isocyanide (Mis3) remains elusive which might be caused by the instability of this compound.