Abstract

As chatbots are increasingly deployed to address service failures, understanding their role in facilitating consumer forgiveness has become essential. Several studies have compared consumers’ reactions to service recovery efforts conducted by a human versus a chatbot. Through three scenario-based experiments (total N = 1875) with Chinese participants, our study examines the interaction between service recovery agents (chatbot vs. human), types of consumer loss (utilitarian vs. symbolic), and service failure severity (low vs. high) in influencing consumer forgiveness. The results reveal that in cases of symbolic loss, consumers perceive humans—rather than chatbots—as more capable of providing emotional support during service recovery, thus promoting forgiveness more effectively. However, this discrepancy diminishes in the case of utilitarian loss. Our findings further suggest that the combined effect of service recovery agents and consumer loss on forgiveness is moderated by service failure severity. In the case of low-severity failures, recovery services provided by humans (vs. chatbots) are more effective in fostering forgiveness for consumers experiencing symbolic losses. However, for high-severity failures, regardless of the type of loss, consumers exhibit a higher level of forgiveness toward recovery services provided by humans. This research offers the following practical implications for managers dealing with service failures: strategic escalation to human agents is recommended for symbolic losses or high-severity failures, but chatbots represent a cost-efficient solution for utilitarian losses in low-severity scenarios.

1. Introduction

Service failure occurs when a firm’s or brand’s actual performance falls short of consumers’ expected standards [1]. This failure inevitably leads to consumer loss, which may include financial damages, wasted time, and emotional exhaustion [2,3,4]. In response, firms implement strategies to redress these losses, a process known as service recovery [5]. Effective service recovery strategies, such as apologies, compensation, explanations, and humor-based communication, can mitigate the negative effects of service failure, which is crucial for enhancing consumer satisfaction and loyalty [6,7,8]. Notably, a high level of consumer forgiveness is a key indicator of successful service recovery [9]. Consumer forgiveness refers to the act of consumers releasing grudges or anger and adopting a more favorable attitude toward the offending company [10].

In traditional service recovery contexts, human agents serve as recovery service providers to manage service failures [11]. By offering emotional support and personalized solutions, they help alleviate consumer dissatisfaction during the service recovery process. Recently, AI-enabled chatbots have been increasingly deployed to complement human-based consumer services [12,13,14]. Compared to human-based services, chatbot-based solutions offer distinct advantages, including lower costs and 24/7 availability [15]. More importantly, with their growing ability to understand consumer needs and emotions, chatbots are becoming capable of serving as recovery agents and engaging in the service recovery process to address service failures. This study aims to investigate whether chatbots can effectively handle service failures in a manner similar to humans and contribute to increased consumer forgiveness.

Numerous studies have shown that individuals’ attitudes toward services provided by humans versus AI depend on the nature of the task [16,17,18]. For example, consumers generally perceive AI agents as more capable of assessing objective and utilitarian attributes [17,19]. Extending these findings to our research context, we predict that consumers’ responses—specifically consumer forgiveness—to services provided by a chatbot versus a human will depend on the type of consumer loss resulting from the service failure. We propose that service failure can lead to two distinct types of consumer losses: utilitarian and symbolic losses [20]. Utilitarian losses typically involve economic resources, while symbolic losses pertain to psychological and social resources. Existing literature primarily explores consumers’ reactions to chatbot service failures [21,22,23,24], but largely overlooks how consumers respond to chatbot involvement in service recovery following service failures. Although recent studies examine consumers’ perceptions and intentions regarding chatbots’ role in service recovery [22,25], there is limited research on how consumers’ reactions to service recovery vary when administered by a human versus a chatbot across different types of consumer losses. To address this gap, the first objective of this study is to investigate how the impact of service recovery agents on consumer forgiveness is influenced by the type of consumer loss.

Additionally, service failure severity is a frequently discussed concept in the literature on service failures, as it significantly influences consumers’ attitudes toward recovery efforts [26,27]. Service failure severity can shape consumers’ perceptions and behavioral responses within service failure contexts [28,29]. Therefore, the second research objective of this study is to examine how the interaction between service recovery agents and consumer loss is influenced by the severity of the service failure.

Several key contributions emerge from this research. First, this study represents an initial effort to examine the interplay between service recovery agents and types of consumer loss in shaping forgiveness following a service failure, thereby enriching the existing marketing literature on service failure and recovery. Second, it reveals two mediating pathways—perceived responsiveness and perceived emotional support—that explain the underlying mechanisms through which recovery agents and loss types influence forgiveness. Finally, we identify a critical boundary condition for this interaction by demonstrating that service failure severity moderates the effects of the recovery agent and the type of loss.

2. Literature Review and Research Model

2.1. Service Failure and Consumer Forgiveness

Service failure is defined as “any instance of actual or perceived mishap, error, or problem that occurs during the experience phase” [30]. It typically arises when the service received does not meet a consumer’s expectations. For example, in the hospitality and tourism sectors, consumers may encounter issues such as hotel noise, stains on bathtubs or shower curtains, and poor attitudes from service employees [31]. In the foodservice industry, service failures often result from delays in food delivery, foreign objects found in a customer’s dish, or rude or indifferent behavior from servers [32]. Service failures generally lead to negative consequences, including consumer dissatisfaction, decreased consumer confidence, and negative word-of-mouth (WOM) [33].

Service failure inevitably leads to customer losses. Grönroos (1984) argued that service failure can, on the one hand, cause consumers to incur economic losses, and on the other hand, result in emotional losses [34]. Building on this, Du and Fan (2007) proposed two types of consumer loss: utilitarian loss and symbolic loss [20]. The distinction between these two types of losses is summarized in Table 1. Utilitarian loss refers to tangible flaws or functional deficiencies that diminish the practical value of a product. It typically involves economic resources such as money, goods, and time, focusing on the losses consumers experience in terms of actual outcomes [20]. Symbolic loss, by contrast, pertains to psychological or social deficiencies that may damage a consumer’s identity, dignity, or relational value. It generally involves psychological and social resources such as status, respect, and empathy. Thus, symbolic loss often emphasizes the consumer’s perception of the relationship between themselves and the service provider following the service failure [20]. Consumers who experience utilitarian losses are typically more concerned with how service providers address their practical problems [4]. In contrast, symbolic losses often involve emotional discomfort, such as feelings of disrespect, neglect, and dissatisfaction. Consumers facing symbolic losses may perceive harm to their image, social status, and personal value [35].

Table 1.

Difference between Utilitarian Loss and Symbolic Loss.

When consumers experience service losses, merchants typically implement a range of service recovery strategies. Consumer forgiveness is a crucial outcome of effective service recovery and is defined as the consumer’s willingness to release resentment toward a firm and adopt a constructive, trusting stance following a service failure [9,10]. Existing literature conceptualizes forgiveness as a multifaceted process influenced by several factors. For example, perceived justice, which encompasses distributive, procedural, and interactional dimensions, serves as a key driver, as consumers are more likely to forgive when they perceive recovery efforts as fair [10]. Joireman et al. (2016) emphasized that the severity of service failure amplifies negative emotions, thus reducing the likelihood of forgiveness by lowering consumers’ tolerance for errors made by firms [36]. While previous studies have enhanced our understanding of how to promote consumer forgiveness, these findings may not be directly applicable to situations in which chatbots serve as the service recovery agent. This study focuses on the combined role of consumer loss type (utilitarian vs. symbolic) and service failure severity in influencing preferences for recovery agents. However, it remains unclear whether chatbots’ ability to foster consumer forgiveness varies across different types of losses and service failure severity.

2.2. Responses to Decisions and Services Provided by a Human Versus AI

Numerous studies have examined consumers’ reactions to services provided by AI versus humans. Existing literature suggests that, although AI often performs better than humans, consumers tend to prefer human decisions over those made by AI, a phenomenon known as algorithm aversion [19,37,38]. However, researchers have found that individuals’ attitudes toward AI and human decision-making are influenced by task characteristics and the favorability of the decision [39,40,41]. For example, people tend to prefer algorithms over human advice when dealing with objective tasks, a phenomenon referred to as algorithm appreciation [19,42,43].

In the context of service failures, most studies have focused on consumers’ attitudes toward service failures caused by AI-enabled agents. For example, research has shown that consumers report lower satisfaction and purchase intentions when a virtual agent (vs. a human agent) causes a service failure [44]. Zhang et al. (2025) found that a consumer’s intention to continue using chatbots is influenced by the chatbot’s emotional expression during service failures [8]. Recently, scholars have begun to explore how chatbots, as service recovery agents, impact consumers’ perceptions, intentions, and behaviors. These studies suggest that factors such as chatbots’ language style, anthropomorphism, empathy, and emoji types influence consumer service recovery satisfaction and forgiveness [45,46,47]. For instance, Cao and Yu (2026) found that chatbots using facial emojis lead to higher consumer satisfaction during service recovery than those using non-facial emojis [48]. Similarly, Shams et al. (2024) discovered that chatbots using informal and human-like language increase consumer satisfaction with service recovery efforts [45]. These studies also highlight the underlying mechanisms by which chatbots promote consumer forgiveness, including perceived empathy, perceived ambiguity, trustworthiness, and perceived governance [46,47,49]. However, the existing literature has paid less attention to how different types of consumer loss influence consumer forgiveness. Specifically, the mediating roles of perceived emotional support and perceived responsiveness in consumer forgiveness, particularly when comparing chatbots to humans, depending on the type of loss (utilitarian vs. symbolic), have not yet been empirically verified.

2.3. Task-Technology Fit Model: Interaction Between Consumer Loss and Service Recovery Agent

Consumer forgiveness is achieved through both emotional and cognitive pathways [50]. Drawing on existing literature, this study hypothesizes two mediating pathways—perceived emotional support (i.e., emotional pathway) and perceived responsiveness (i.e., cognitive pathway). Perceived emotional support is defined as the provision of empathetic and reassuring expressions that help alleviate individuals’ emotional distress [51]. Perceived responsiveness, on the other hand, refers to the speed and accuracy with which a service provider delivers prompt, efficient, and relevant information in response to consumer needs [52].

We next draw on task-technology fit theory to explore how the interaction between recovery agents and loss type influences consumer forgiveness. Task-technology fit theory posits that the alignment between task requirements and technology attributes can significantly influence technology utilization and user performance. Task-technology fit refers to the degree to which technology aids an individual in performing a task [53]. This fit is determined by two key components: task attributes and technology attributes. When a technology’s attributes closely match the demands of a task, task-technology fit is high, leading to positive outcomes [53]. Conversely, even if a technology is advanced, users are unlikely to adopt it if it does not meet their task requirements [54].

In our context, the technology can be understood as either a human agent or a chatbot, while the task is to address consumer losses and facilitate forgiveness. Consumers may experience utilitarian and/or symbolic losses when encountering service failures. When consumers face symbolic losses, they are more likely to seek emotional value during the service recovery process [55]. They typically desire understanding and empathy from service providers, which helps alleviate the negative emotions triggered by service failures. In such cases, the service recovery provider must address the emotional needs of consumers experiencing symbolic losses. Human service providers, with their inherent capacity for emotional intelligence [55,56,57], are well-suited to meet these task demands. In contrast, chatbots, which are often perceived as lacking minds and agency, are viewed merely as tools serving humans [58,59,60]. As a result, they are commonly perceived as lacking empathy and struggling to perform emotion-oriented tasks leading to a lower task-technology fit and diminished effectiveness in fostering forgiveness [17,61,62]. Therefore, in the case of symbolic losses, humans are likely to outperform chatbots in promoting consumer forgiveness by providing more emotional support.

When consumers experience service failures, they generally expect service providers to respond promptly and effectively [63]. In particular, for utilitarian losses involving tangible or functional deficits, consumers place greater emphasis on service providers’ adaptability and the provision of practical solutions, as they have higher expectations for the speed of service recovery. In such situations, consumers seek immediate remedies from recovery agents to minimize their losses [64,65]. Today, chatbots have been trained to recognize consumers’ essential needs and respond to complaints with similar speed and efficiency as human agents [66,67,68]. Therefore, in the case of utilitarian losses, both humans and chatbots can meet the demands for quick, tangible solutions and perform effectively in enhancing consumers’ perceived responsiveness. As a result, there may be little difference in consumer forgiveness when either chatbots or humans handle utilitarian losses.

Our theoretical model is closely aligned with perceived justice theory, a cornerstone of service recovery research [1,6]. Perceived emotional support reflects interactional justice, which pertains to the fairness of interpersonal treatment during recovery, such as respect, empathy, and sincerity [10]. For consumers experiencing symbolic loss, interactional justice is particularly important, as emotional support addresses the core injustice of being devalued. Perceived responsiveness corresponds with procedural justice, which concerns the fairness of recovery processes, including speed, efficiency, and transparency [69]. In the case of utilitarian loss, procedural justice plays a crucial role, as consumers prioritize the timely resolution of practical issues. We thus hypothesize:

H1a:

In symbolic loss contexts, recovery services provided by humans are more effective in promoting consumer forgiveness than those provided by chatbots.

H1b:

In utilitarian loss contexts, the effect of the service recovery agent on consumer forgiveness is mitigated.

H2a:

The effect proposed in H1a is mediated by perceived emotional support. Specifically, in symbolic loss contexts, humans are perceived as more capable of providing emotional support than chatbots, thereby promoting consumer forgiveness.

H2b:

The effect proposed in H1b is mediated by perceived responsiveness. Specifically, in utilitarian loss contexts, both humans and chatbots are perceived to have high levels of responsiveness, thereby promoting consumer forgiveness.

2.4. Moderating Effect of Service Failure Severity

Service failure severity refers to the extent of consumer losses [28,70], and it can significantly influence the effectiveness of service recovery [71,72]. The severity of a failure shapes consumers’ tolerance, satisfaction, and behavioral responses [73].

Cognitive appraisal theory further explains why service failure severity moderates our core effects [36,69]. Consumers appraise service failures along three key dimensions: controllability (whether the failure was avoidable), stability (how likely it is to recur), and intentionality (whether the failure was deliberate). For high-severity failures, consumers are more likely to appraise the incident as less controllable, more stable, or potentially intentional, which intensifies their feelings of injustice and the need for meaningful redress. In such situations, human agents are better equipped to address these appraisals. In contrast, for low-severity failures, appraisals tend to be less intense (e.g., perceived as accidental or one-time occurrences), so the primary driver of agent preferences remains the core distinction between loss types and their corresponding justice needs.

In cases of severe service failures, consumers experience relatively greater utilitarian and symbolic losses, which intensifies their negative reactions. When service failures are significant, consumers are less likely to forgive service providers [36]. Severe service failures increase consumers’ focus on how firms resolve the issue, prompting them to invest more emotional energy in the recovery process [74]. Specifically, when the severity of a service failure is high, consumers expect service providers to address their complaints with sincerity. Furthermore, consumers who experience serious service failures care not only about the timeliness of solutions but also about whether service providers can offer emotional support. As noted earlier, chatbots are perceived as lacking emotional understanding [75], which may hinder forgiveness among consumers experiencing severe service failures. In contrast, humans can establish emotional connections with these consumers, helping to restore their confidence in both the functional and emotional capabilities of service providers. We thus hypothesize:

H3a:

Under the high-severity condition, consumers prefer humans to provide recovery services regardless of the type of consumer loss.

H3b:

Under the low-severity condition, the interaction effect predicted in H1 remains significant.

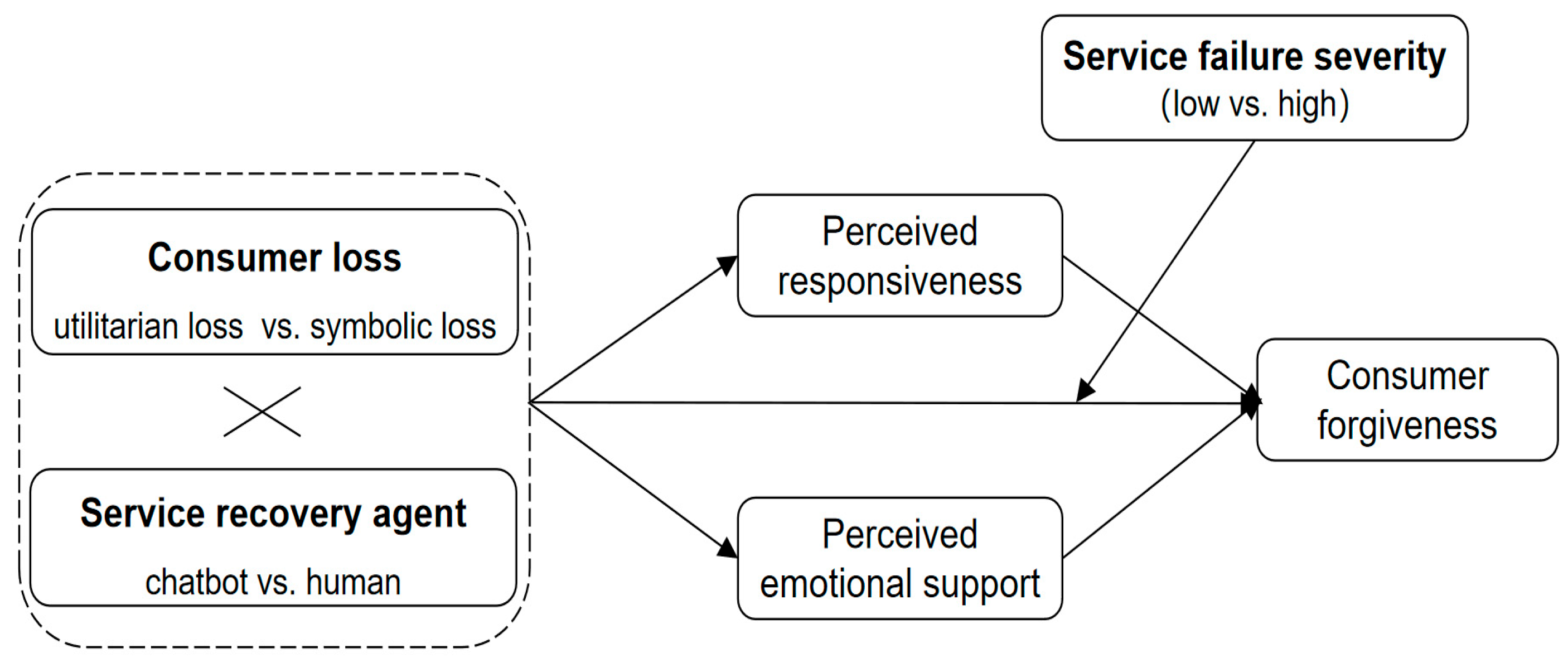

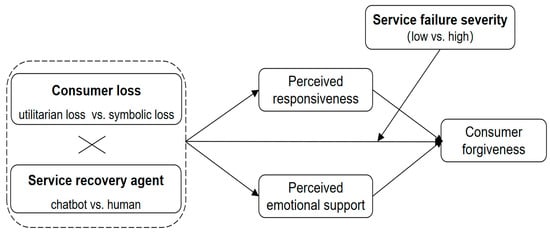

Figure 1 shows the theoretical model.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3. Study 1

3.1. Design and Participants

Study 1 aimed to examine the interaction between consumer loss and service recovery agent on consumer forgiveness (H1). A 2 (consumer loss: symbolic loss vs. utilitarian loss) × 2 (recovery agent: chatbot vs. human) between-subjects design was employed. A total of 270 participants were recruited through Wenjuanxing and were offered a reward of 2 yuan. After excluding 30 invalid responses (e.g., duplicate answers, failed attention checks), 240 valid responses were retained (Mage = 24.89; 59.7% female).

3.2. Procedure

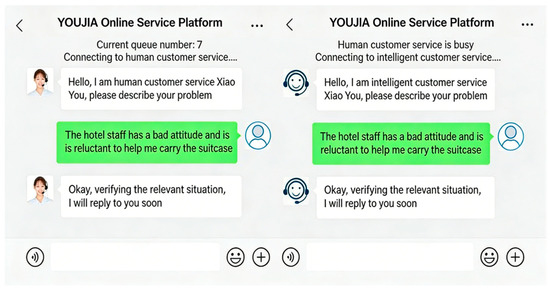

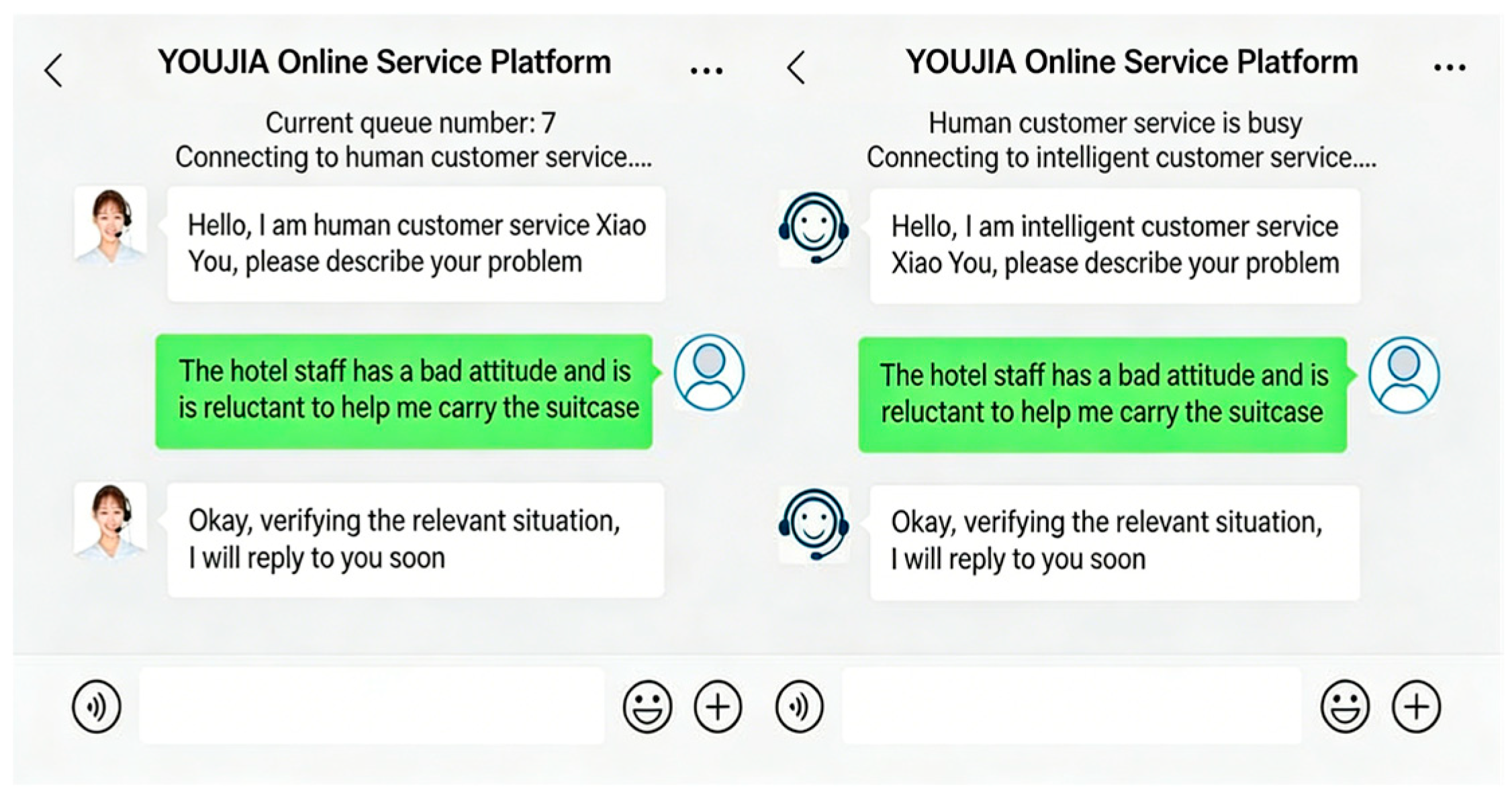

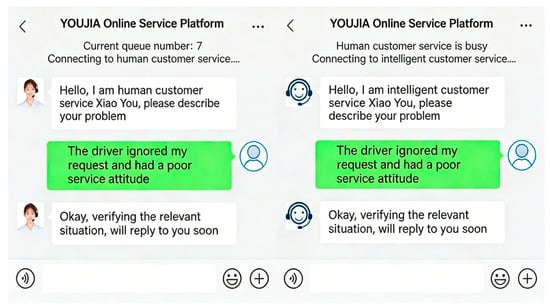

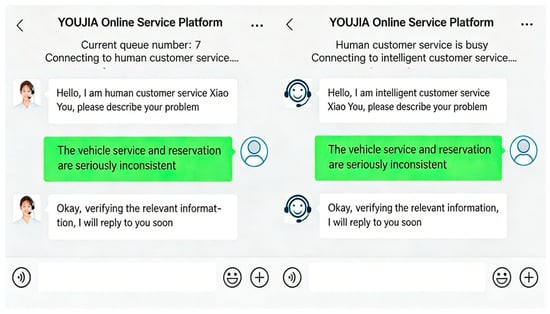

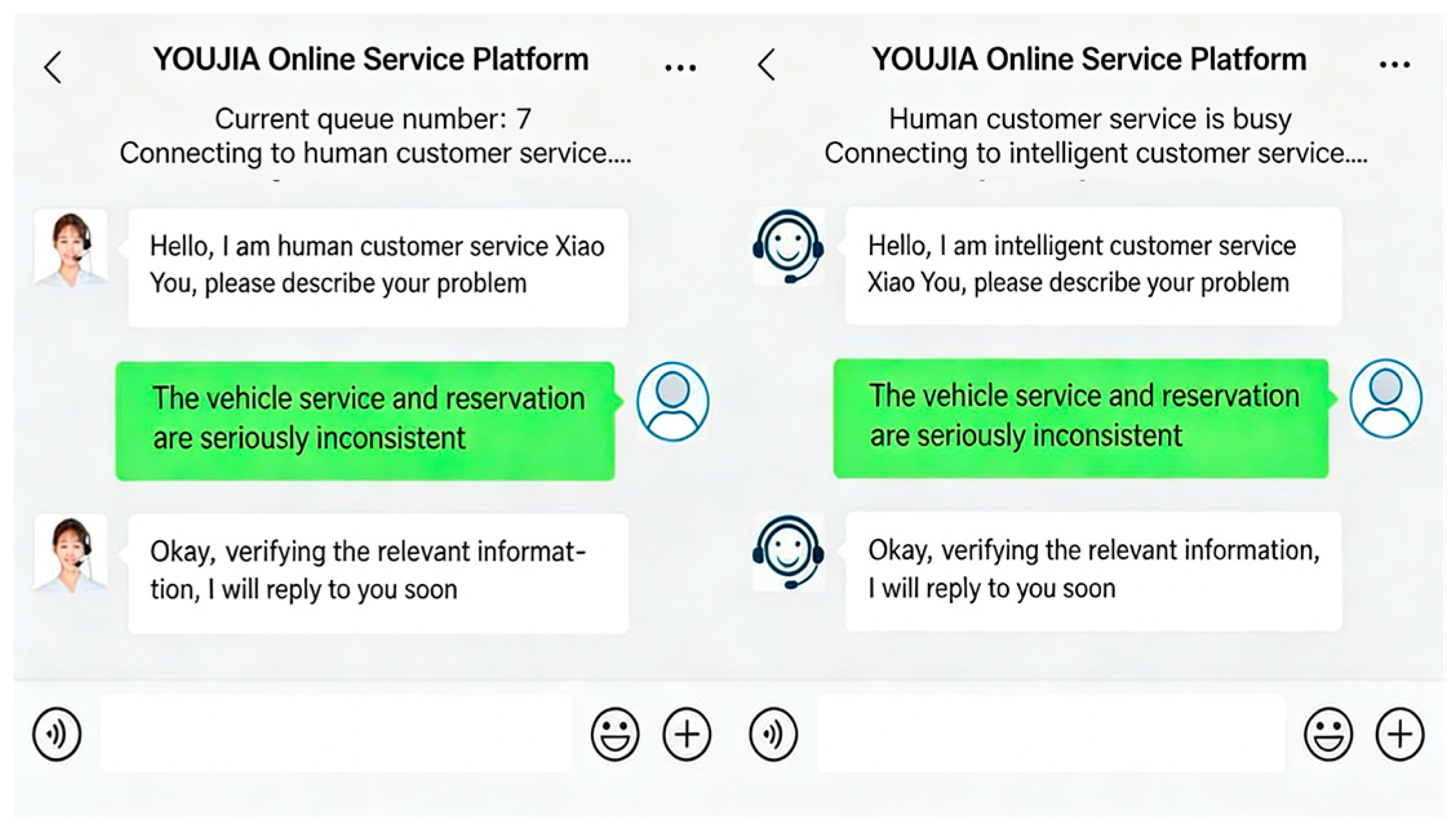

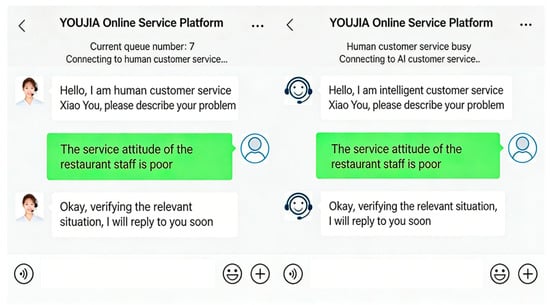

Consumers’ current emotions can influence their forgiveness during service failures [25]. To mitigate the potential impact of participants’ current emotions on the results, participants were first asked to report their current emotional state [76]. They also provided feedback on their previous experiences interacting with chatbots. Subsequently, participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions (utilitarian loss vs. symbolic loss) and read a service failure scenario set in the hotel check-in context. In the symbolic loss condition, participants were informed that they encountered poor service attitudes, while in the utilitarian loss condition, they were told about luggage damage during check-in at Hotel YOUJIA. The detailed experimental materials are provided in Appendix A.1. Participants were then asked to rate their perceived losses [77]. Following this, they were told that they had made a complaint, which was addressed either by a human agent (in the human condition) or by a chatbot (in the chatbot condition). Participants were presented with a screenshot of the dialogue corresponding to their interaction with the human agent or chatbot (see Figure A1 and Figure A2 in Appendix A.1). Finally, they were asked to rate their perceived forgiveness on a 7-point scale. Demographic information was also collected, with all items listed in Appendix B. The reliability and validity of the measurement scales were assessed through confirmatory factor analysis (see Table A2 in Appendix C.1).

3.3. Results

Manipulation Checks. First, we assessed the realism of the experimental scenarios. Participants in both groups, who were exposed to different types of consumer losses, rated the experimental scenario as highly realistic (Msymbolic = 5.81, t(119) = 16.32, p < 0.001; Mutilitarian = 5.06, t(119) = 10.86, p < 0.001). Second, the service recovery agent was more frequently perceived as a chatbot in the chatbot group and more frequently perceived as a human in the human group (Mchatbot = 1.86, SD = 1.03; Mhuman = 6.09, SD = 1.16; t(238) = −26.73, p < 0.001), indicating successful manipulation of the service recovery agent. Regarding consumer loss, participants reported greater utilitarian loss than symbolic loss in the utilitarian loss condition (Msymbolic = 5.23, SD = 1.08; Mutilitarian = 4.50, SD = 1.41; t(238) = −4.53, p < 0.001), whereas they reported greater symbolic loss than utilitarian loss in the symbolic loss condition (Msymbolic = 4.51, SD = 1.05; Mutilitarian = 5.08, SD = 1.08; t(238) = 4.13, p < 0.001). These results confirm successful manipulation of the consumer loss variable. Additionally, participants across the four groups showed no significant differences in their current emotions (F(1, 236) = 3.06, p > 0.05).

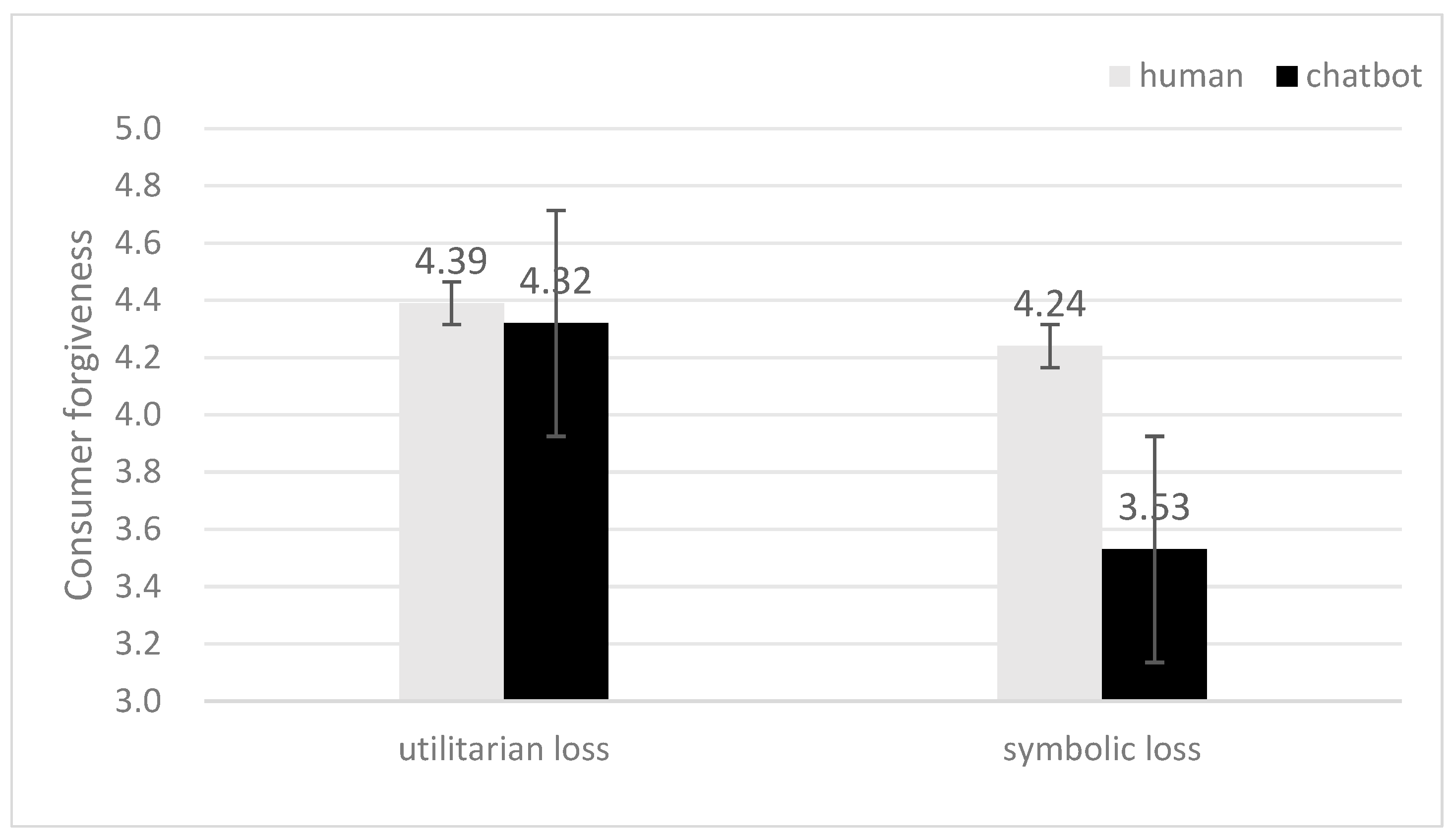

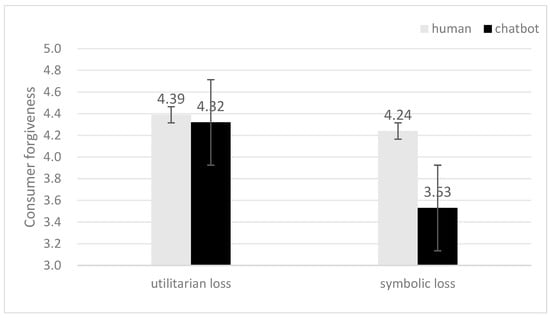

Interaction between Service Recovery Agent and Consumer Loss. An ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of consumer loss (Mutilitarian = 4.36, SD = 1.25; Msymbolic = 3.88, SD = 1.25; F(1, 236) = 8.69, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.04), while the service recovery agent did not have a significant main effect (Mhuman = 4.31, SD = 1.20; Mchatbot = 3.92, SD = 1.32; F(1, 236) = 5.99, p > 0.05, η2 = 0.02) on consumer forgiveness. The 2 × 2 ANOVA revealed a significant interaction between service recovery agent and consumer loss (F(1, 236) = 4.31, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.02; see Figure 2). In the case of utilitarian loss, the type of service recovery agent had no significant effect on consumer forgiveness (Mhuman = 4.39, SD = 1.03; Mchatbot = 4.32, SD = 1.14; F(1, 236) = 0.08, p > 0.05). However, in the case of symbolic loss, humans outperformed chatbots in promoting consumer forgiveness (Mhuman = 4.24, SD = 1.09; Mchatbot = 3.53, SD = 1.21; F(1, 236) = 10.46, p < 0.001). Therefore, H1a and H1b were supported.

Figure 2.

Interaction between service recovery agent and consumer loss on consumer forgiveness.

4. Study 2

4.1. Design and Participants

Study 2 aimed to examine the psychological mechanisms that differentiate consumers’ responses to human agents and chatbots in the context of utilitarian or symbolic loss (H2). A 2 (consumer loss: symbolic loss vs. utilitarian loss) × 2 (recovery agent: chatbot vs. human) between-subjects design was employed. A total of 566 participants were recruited through Wenjuanxing and received a reward of 2 yuan. After excluding 46 invalid responses (e.g., duplicate answers, failed attention checks, etc.), 520 valid samples were retained (Mage = 23.72 years; 65% female).

4.2. Procedure

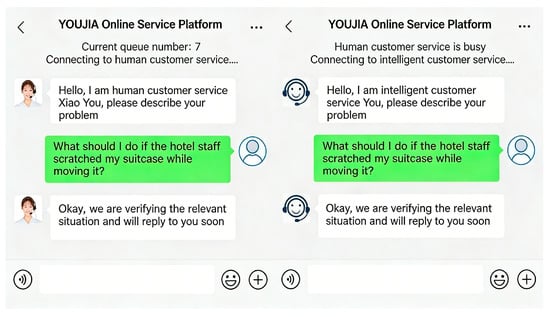

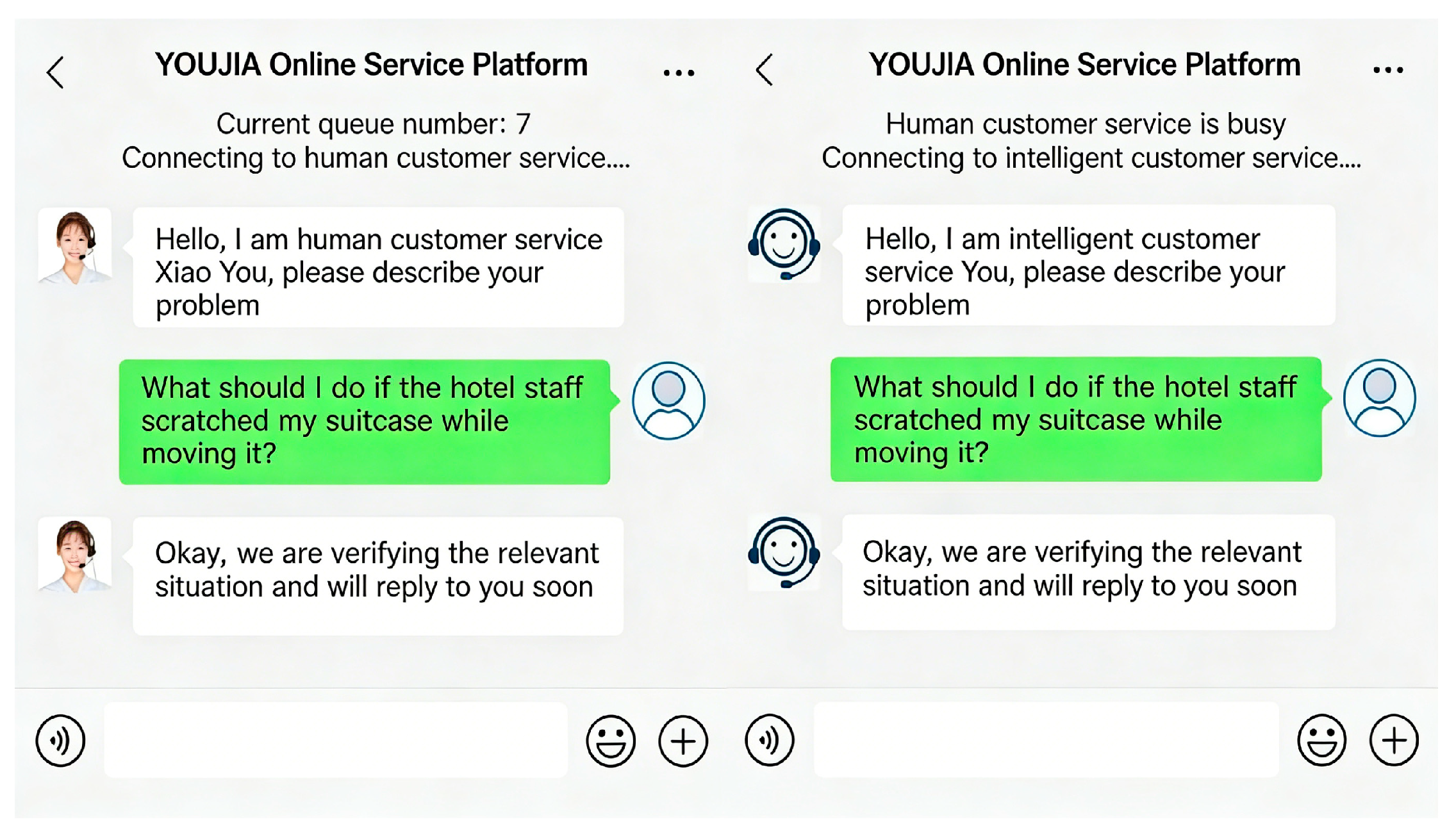

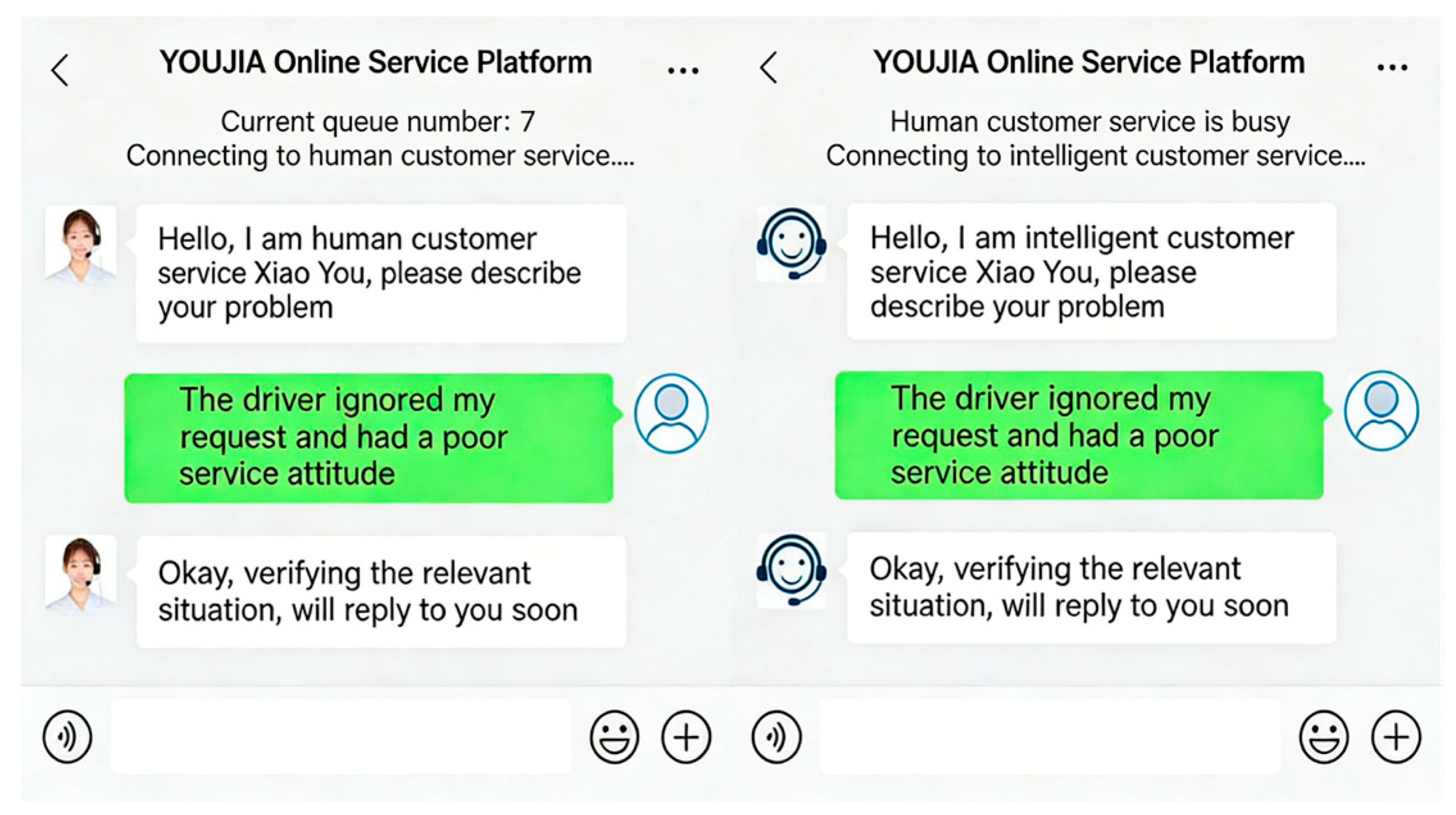

Following the procedure used in Study 1, participants first reported their current emotions and their experiences interacting with chatbots. Next, participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions (utilitarian loss vs. symbolic loss) and read a scenario involving a service failure in the taxi ride context [64]. In the symbolic loss condition, participants were informed that their needs were ignored, whereas in the utilitarian loss condition, they were told that some taxi service facilities were unavailable when taking a taxi through the YOUJIA platform. The detailed experimental materials are presented in Appendix A.2. Participants were then asked to rate their perceived losses. Following this, they learned that they had made a complaint, which was handled either by a human agent (in the human condition) or by a chatbot (in the chatbot condition). They reviewed a screenshot of the dialogue regarding their interactions with the human agent or chatbot (see Figure A3 and Figure A4 in Appendix A.2). Finally, participants reported their perceived responsiveness, perceived emotional support, and perceived forgiveness on a 7-point scale. Demographic information was also collected. The reliability and validity of the measurement scales were assessed through confirmatory factor analysis (see Table A3 in Appendix C.2).

4.3. Results

Manipulation checks. First, the scenarios were perceived as highly realistic, with scores significantly higher than the scale midpoint. The results confirmed that participants across different groups all rated the experimental scenario as extremely realistic (Msymbolic = 5.19, t(259) = 73.92, p < 0.001; Mutilitarian = 5.07, t(259) = 70.01, p < 0.001). Second, the service recovery agent was perceived more as a chatbot in the chatbot group and more as a human in the human group (Mchatbot = 1.91, SD = 0.62; Mhuman = 5.72, SD = 0.65; t(518) = −68.5, p < 0.001), indicating successful manipulation of the service recovery agent. Regarding consumer loss, participants reported experiencing greater utilitarian loss than symbolic loss in the utilitarian loss condition (Msymbolic = 4.50, SD = 1.29; Mutilitarian = 5.52, SD = 1.29; t(518) = 9.34, p < 0.01), while they reported greater symbolic loss than utilitarian loss in the symbolic loss condition (Msymbolic = 4.93, SD = 0.84; Mutilitarian = 3.26, SD = 1.11; t(518) = −19.4, p < 0.001), indicating successful manipulation of consumer loss. Additionally, participants across the four groups showed no significant difference in their current emotions (F(1, 516) = 3.52, p > 0.05).

Interaction between service recovery agent and consumer loss. An ANOVA revealed significant main effects of consumer loss (Mutilitarian = 3.60, SD = 0.06; Msymbolic = 4.21, SD = 0.06; F(1, 516) = 78.33, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.05) and service recovery agent (Mhuman = 4.04, SD = 0.06; Mchatbot = 3.78, SD = 0.06; F(1, 516) = 26.68, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.05) on consumer forgiveness. The 2 × 2 ANOVA showed a significant interaction between consumer loss and service recovery agent on consumer forgiveness (F(1, 516) = 19.81, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.01). For utilitarian loss, the service recovery agent had no significant effect on consumer forgiveness (Mhuman = 3.52, SD = 0.97; Mchatbot = 3.46, SD = 1.34; F(1, 516) = 0.19, p > 0.1). However, for symbolic loss, humans outperformed chatbots in promoting consumer forgiveness (Mhuman = 4.79, SD = 0.92; Mchatbot = 3.86, SD = 1.05; F(1, 516) = 42.03, p < 0.001). These results replicate the findings from Study 1, supporting H1.

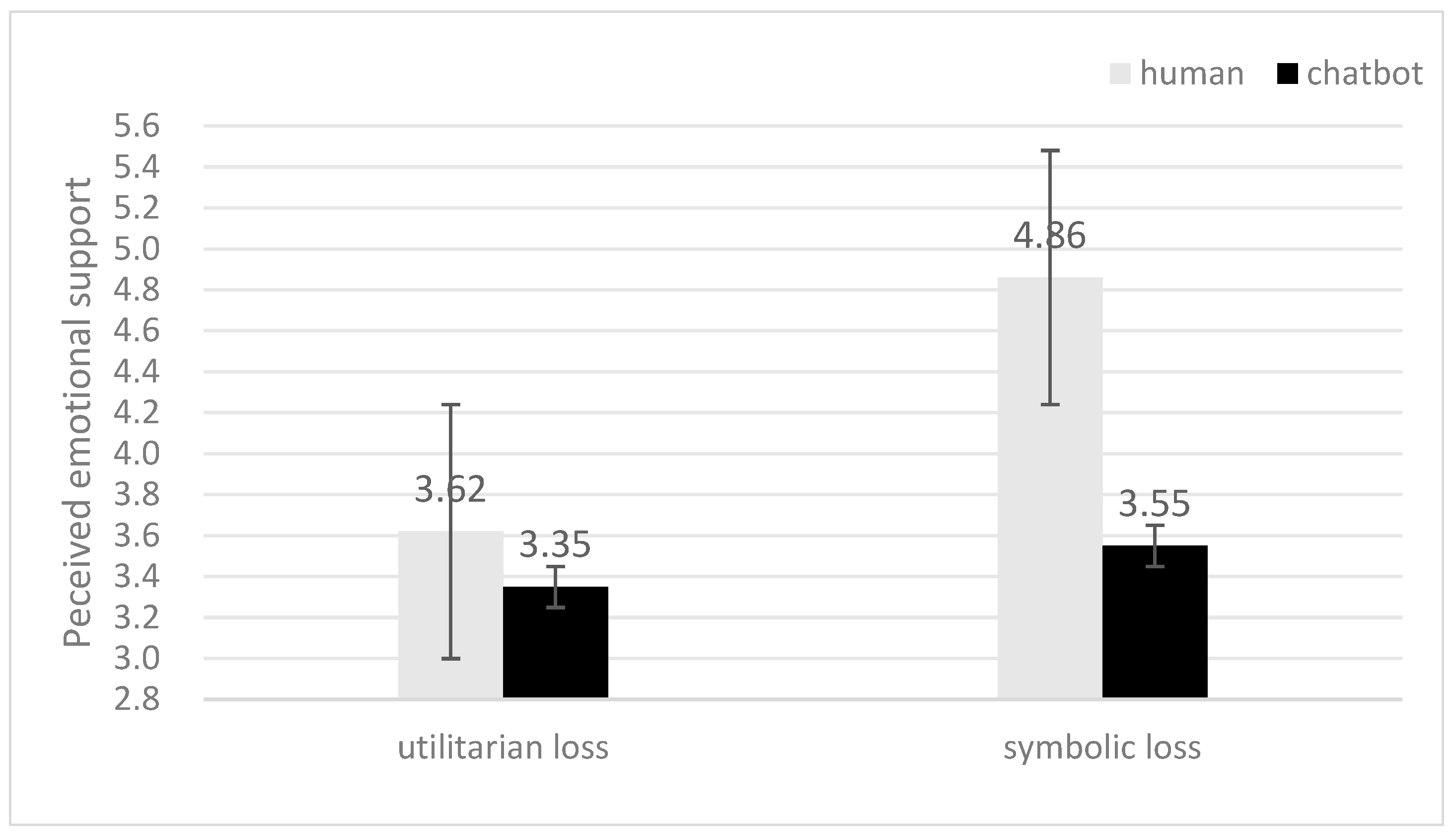

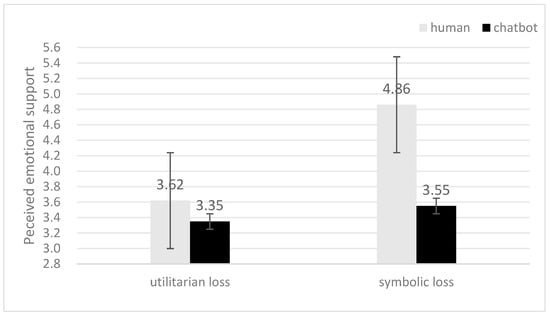

Perceived emotional support. The ANOVA revealed significant main effects of service recovery agent (Mhuman = 4.23, SD = 0.07; Mchatbot = 3.46, SD = 0.07; F(1, 516) = 57.40, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.11) and consumer loss (Mutilitarian = 3.48, SD = 0.07; Msymbolic = 4.20, SD = 0.07; F(1, 516) = 50.64, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.10) on perceived emotional support. Additionally, there was a significant interaction between service recovery agent and consumer loss on perceived emotional support (F(1, 516) = 25.93, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.07; see Figure 3). Specifically, humans were perceived to provide more emotional support than chatbots in the case of symbolic loss (Mhuman = 4.86, SD = 0.97; Mchatbot = 3.55, SD = 1.22; F(1, 516) = 76.28, p < 0.001). This difference was reduced in the case of utilitarian loss (Mhuman = 3.62, SD = 1.07; Mchatbot = 3.35, SD = 1.33; F(1, 516) = 3.31, p > 0.05).

Figure 3.

Interaction between service recovery agent and consumer loss on perceived emotional support.

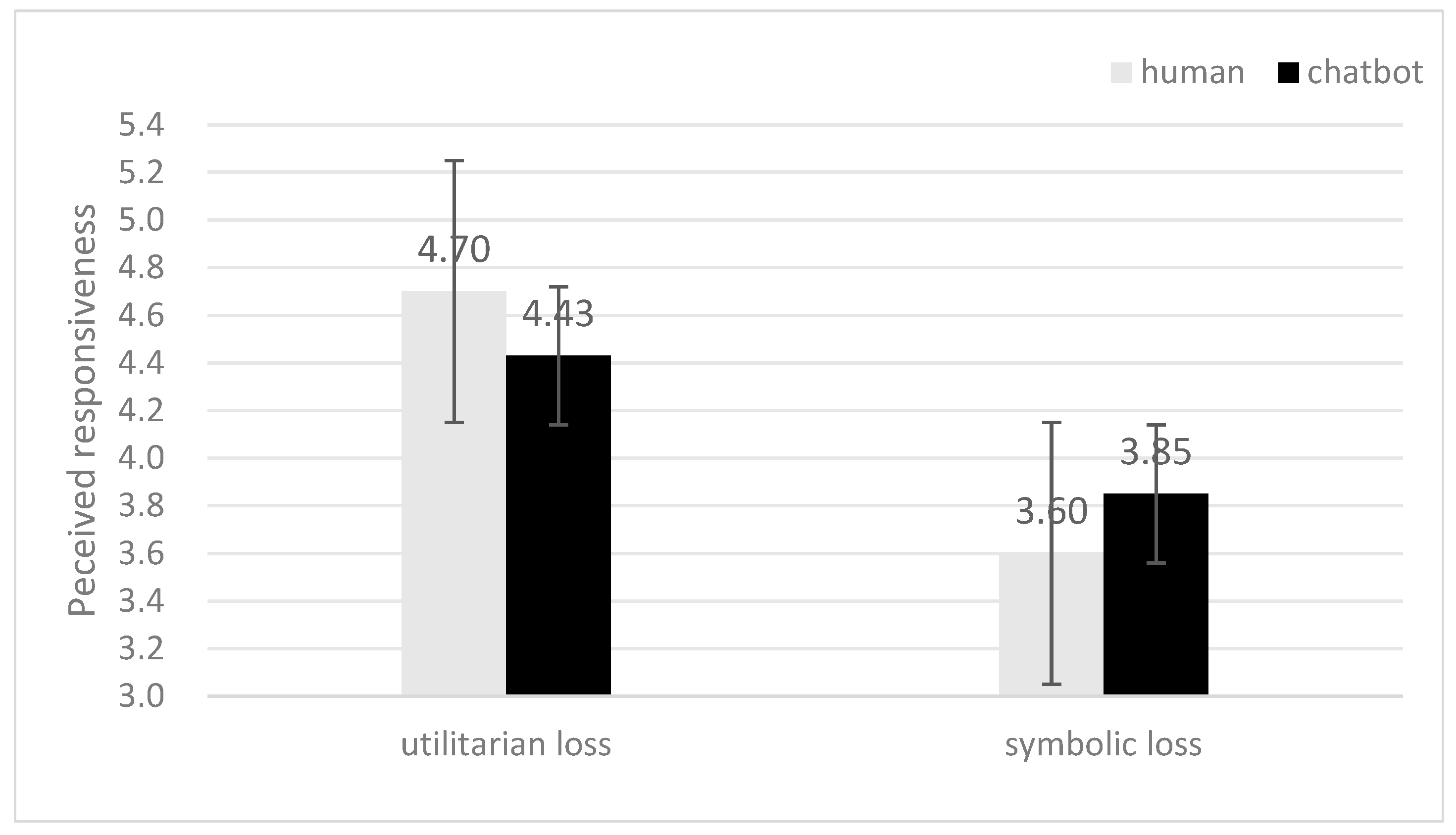

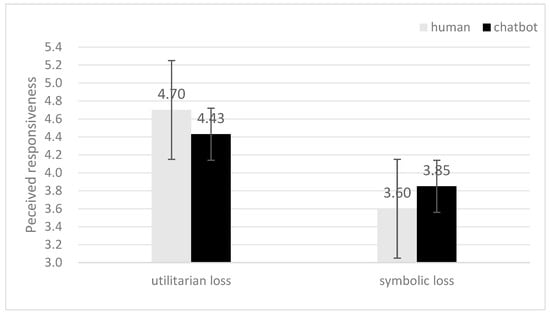

Perceived responsiveness. The ANOVA revealed that service recovery agent (Mhuman = 4.16, SD = 0.07; Mchatbot = 4.13, SD = 0.07; F(1, 516) = 0.08, p > 0.05, η2 = 0.01) had no significant effects on perceived responsiveness, while consumer loss (Mutilitarian = 4.56, SD = 0.07; Msymbolic = 3.73, SD = 0.07; F(1, 516) = 64.05, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.19) had significant effects on perceived responsiveness. Additionally, there was a significant interaction between service recovery agent and consumer loss on perceived responsiveness (F(1, 516) = 5.39, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.01; see Figure 4). However, the service recovery agent had no significant effect on perceived responsiveness, regardless of the type of loss (utilitarian loss: Mhuman = 4.70, SD = 1.05; Mchatbot = 4.43, SD = 1.09; F(1, 516) = 2.88, p > 0.05; symbolic loss: Mhuman = 3.60, SD = 1.52; Mchatbot = 3.85, SD = 1.07; F(1, 516) = 2.52, p > 0.1).

Figure 4.

Interaction between service recovery agent and consumer loss on perceived responsiveness.

Moderated mediation analysis. We conducted a moderated mediation analysis using PROCESS Model 8 with service recovery agents as the independent variable [78], consumer forgiveness as the dependent variable, consumer loss as the moderator, and perceived emotional support and perceived responsiveness as the two mediators. The results showed that the indirect effect of service recovery agent on consumer forgiveness through perceived responsiveness was significant in the case of utilitarian loss (β = −0.03, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [−0.0784, −0.0022]). However, the indirect effect of service recovery agent on consumer forgiveness through perceived responsiveness was not significant in the case of symbolic loss (β = 0.02, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [−0.0048, 0.0745]). Additionally, the indirect effect of service recovery agent on consumer forgiveness through perceived emotional support was not significant in the case of utilitarian loss (β = 0.06, SE = 0.03, 95% CI = [−0.0020, 0.1307]). In contrast, the indirect effect of service recovery agent on consumer forgiveness through perceived emotional support was significant in the case of symbolic loss (β = 0.28, SE = 0.07, 95% CI = [0.1520, 0.4224]). These findings indicate that humans are perceived to provide more emotional support than chatbots in the case of symbolic loss, thereby increasing the likelihood of consumer forgiveness. However, in the case of utilitarian loss, both humans and chatbots are perceived as highly responsive, enabling both to effectively enhance consumer forgiveness. These results support H2a and H2b.

5. Study 3

5.1. Pretest

Study 3 aimed to investigate how the interaction between service recovery agent type and consumer loss influences consumer forgiveness, with a particular focus on how this relationship is moderated by service failure severity. To achieve this, a pretest was conducted to validate the manipulation of service failure severity. We first compiled a range of service failure scenarios involving both symbolic and utilitarian losses, sourced from cases reported on a website. Six graduate students were asked to rate the severity of these scenarios, and based on their ratings, we selected the highest-rated scenarios (high-severity) and the lowest-rated scenarios (low-severity) for each type of loss as the experimental stimuli.

A total of 191 participants were recruited for the pretest, with 160 valid responses retained (Mage = 22.8; 53.42% female). Participants were randomly assigned to different severity conditions within each loss type. The results indicated that, regardless of the consumer loss type, participants in the high-severity condition perceived significantly more severe service failures than those in the low-severity condition (Mlow = 4.91, SD = 1.62; Mhigh = 5.76, SD = 1.10; F(1, 158) = 115.23, p < 0.001). This confirmed that the manipulation of service failure severity was successful. These experimental stimuli were then used in the formal experiment.

5.2. Design and Participants

Study 3 adopted a 2 (consumer loss: symbolic vs. utilitarian) × 2 (recovery agent: chatbot vs. human) × 2 (service failure severity: low vs. high) between-subjects design to examine whether the interaction between consumer loss and service recovery agent on consumer forgiveness was influenced by service failure severity (H3). A total of 1200 participants were randomly recruited through Wenjuanxing and received a reward of 2 yuan. After excluding invalid responses, 995 valid responses were retained (Mage = 23.90; 63.97% female).

5.3. Procedure

Following the procedures used in the previous studies, participants were first asked to report their current emotions and their experience interacting with chatbots. Participants were then randomly assigned to one of four conditions (utilitarian loss vs. symbolic loss; high-severity vs. low-severity) and read a scenario of service failure in the takeaway service context [69]. Participants were informed that they encountered a poor service attitude (in the symbolic loss condition) or missing meals (in the utilitarian loss condition) when ordering from the YOUJIA takeaway platform. In the context of utilitarian loss, the seller forgot to deliver free (paid) items in the low-severity condition (in the high-severity condition). In the symbolic loss context, the merchant impatiently (rudely) agreed to the consumer’s request to change the food’s taste in the low-severity condition (in the high-severity condition). The detailed experimental materials are shown in Appendix A.3. Participants were then asked to rate their perceived loss and the severity of the service failure. Next, they read that they had made a complaint and that their complaint was handled either by a human agent (in the human condition) or by a chatbot (in the chatbot condition). Finally, participants reported their perceived forgiveness, and demographic information was also collected. The reliability and validity of the measurement scales were assessed through confirmatory factor analysis (see Table A4 in Appendix C.3).

5.4. Results

Manipulation Checks. First, for the realism check, the results confirmed that participants in both groups perceived the experimental scenario as highly realistic (Msymbolic = 5.81, t(495) = 16.32, p < 0.001; Mutilitarian = 5.06, t(498) = 10.86, p < 0.001). Second, the service recovery agent was more strongly perceived as a chatbot in the chatbot group and more strongly perceived as a human in the human group (Mchatbot = 2.01, SD = 1.16; Mhuman = 5.98, SD = 1.02; t(993) = −26.31, p < 0.001). Regarding consumer loss, participants reported greater utilitarian loss than symbolic loss in the utilitarian loss condition (Msymbolic = 5.05, SD = 1.27; Mutilitarian = 5.27, SD = 0.94; t(993) = −13.10, p < 0.01), while they reported greater symbolic loss than utilitarian loss in the symbolic loss condition (Msymbolic = 5.46, SD = 1.28; Mutilitarian = 4.42, SD = 1.22; t(993) = −13.10, p < 0.001), indicating successful manipulation of consumer loss. Service failure severity was perceived as higher in the high-severity condition than in the low-severity condition (Mhigh = 5.25, SD = 1.24; Mlow = 4.62, SD = 1.30; t(993) = −7.81, p < 0.001), confirming the successful manipulation of service failure severity. Additionally, participants across the eight groups showed no significant difference in current emotions (F(1, 987) = 3.06, p > 0.05).

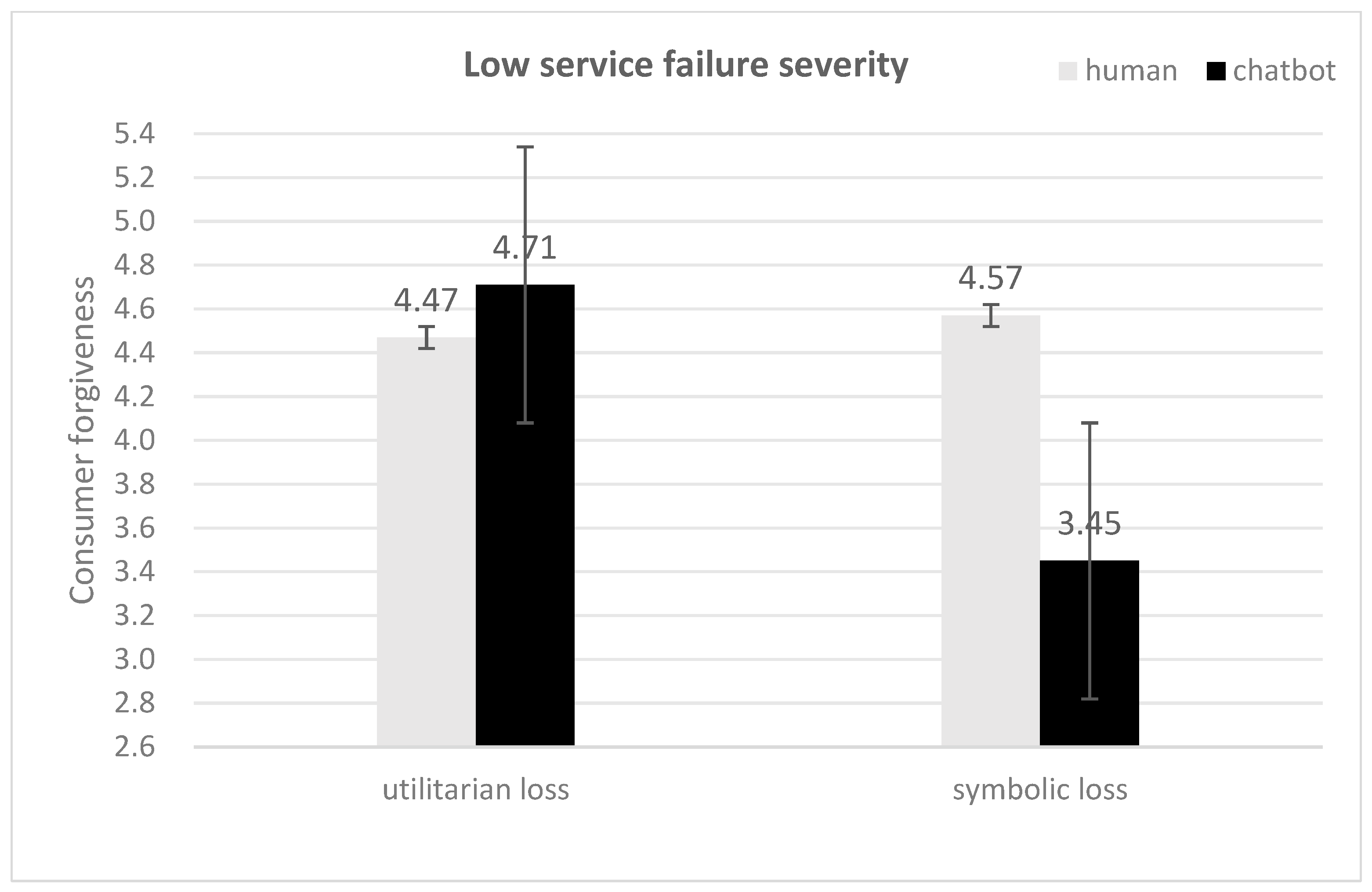

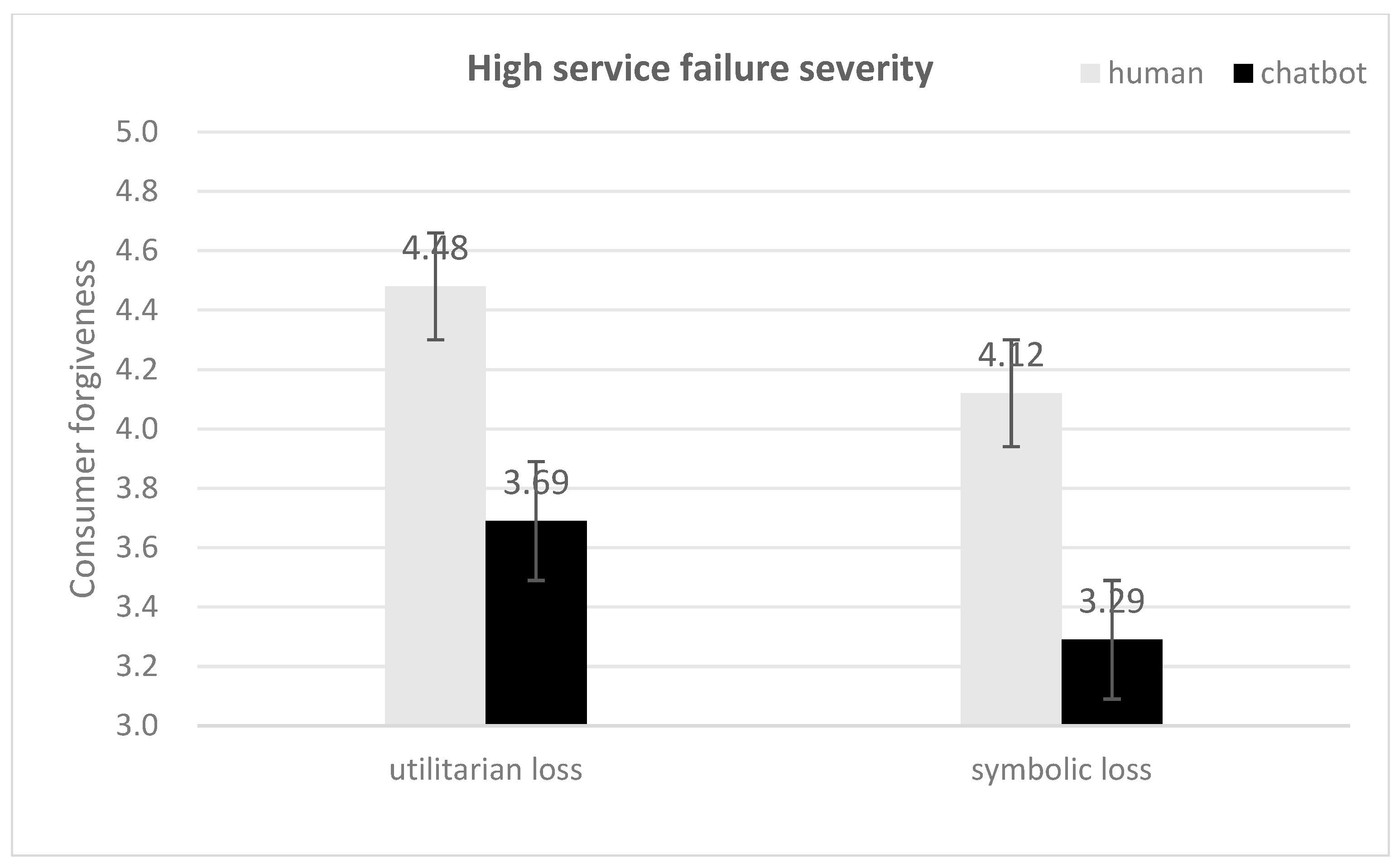

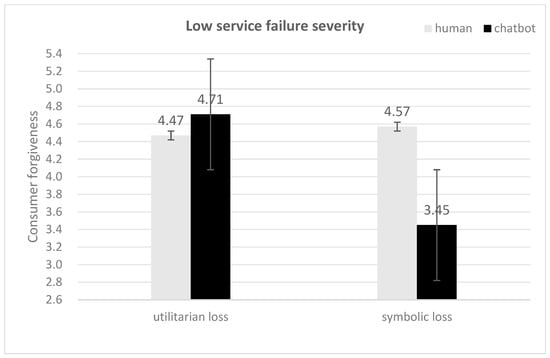

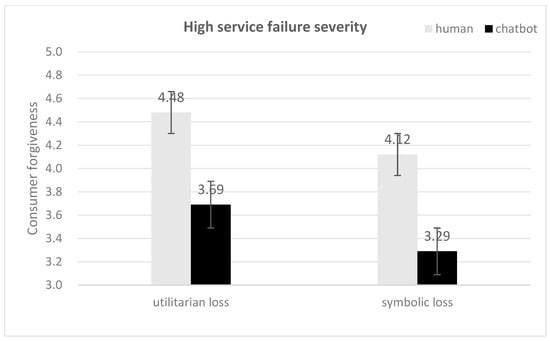

Moderating Effect of Service Failure Severity. An ANOVA revealed significant main effects of service failure severity (Mhigh = 3.82, SD = 1.19; Mlow = 4.21, SD = 1.18; F(1, 987) = 26.66, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.03), consumer loss (Mutilitarian = 4.26, SD = 1.13; Msymbolic = 3.77, SD = 1.22; F(1, 987) = 43.97, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.04), and service recovery agent type (Mhuman = 4.47, SD = 1.07; Mchatbot = 3.65, SD = 1.17; F(1, 987) = 131.10, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.12) on consumer forgiveness. The results also showed a significant interaction between consumer loss, service recovery agent, and service failure severity on consumer forgiveness (F(1, 987) = 4.74, p < 0.05, η2 = 0.01). In the low-severity condition, the interaction between consumer loss and service recovery agent on consumer forgiveness was significant (F(1, 987) = 14.32, p < 0.01, see Figure 5). Specifically, for symbolic loss, humans performed better than chatbots in promoting consumer forgiveness (Mchatbot = 3.45, SD = 1.19; Mhuman = 4.57, SD = 0.97; F(1, 987) = 8.61, p < 0.01). However, for utilitarian loss, this effect was mitigated (Mchatbot = 4.71, SD = 1.00; Mhuman = 4.47, SD = 1.01; F(1, 987) = 5.73, p > 0.05). In the high-severity condition, the interaction between consumer loss and service recovery agent on consumer forgiveness was not significant (F(1, 987) = 0.45, p > 0.05, see Figure 6). Regardless of the loss type, humans performed better than chatbots in promoting consumer forgiveness in the high-severity condition (symbolic loss: Mchatbot = 3.29, SD = 1.06; Mhuman = 4.12, SD = 1.14; F(1, 987) = 42.93, p < 0.001; utilitarian loss: Mchatbot = 3.69, SD = 1.10; Mhuman = 4.48, SD = 1.09; F(1, 987) = 32.64, p < 0.001).

Figure 5.

Interaction between consumer loss and recovery agent in the low-severity condition.

Figure 6.

Interaction between consumer loss and recovery agent in the high-severity condition.

6. Discussion

6.1. General Discussion

With the advancement of machine learning technologies, an increasing number of companies are deploying chatbots as service recovery agents. As a result, consumers are progressively turning to chatbots to resolve complaints arising from service failures. This practice has raised an important question: Can chatbots address service failures as effectively as human agents? To investigate this, three studies were conducted to examine how the interplay between service recovery agents, consumer loss, and service failure severity influences consumer forgiveness in the context of service failures.

The impact of service recovery agents on consumer forgiveness was found to be contingent upon the type of consumer loss. In the case of symbolic loss, addressing consumer complaints through a human agent is more effective in fostering forgiveness than handling them through a chatbot. However, this effect is diminished in the context of utilitarian loss. To explore the underlying mechanisms of this phenomenon, we examined consumer behavior in these contexts. Specifically, when consumers experience symbolic loss, they seek emotional support [57]. Existing literature suggests that chatbot interactions tend to reduce consumers’ emotional experiences [79]. In contrast, humans are better equipped to provide emotional support, making them more effective in promoting consumer forgiveness in the case of symbolic loss. On the other hand, when consumers experience utilitarian loss, they prioritize efficient problem-solving. From a utilitarian perspective, consumers expect recovery services to be accurate, responsive, and compatible [80]. Both human agents and chatbots exhibit high responsiveness, allowing them to effectively enhance consumer forgiveness in cases of utilitarian loss.

We also found that the interaction between service recovery agents and consumer loss is influenced by the severity of the service failure. In the case of high-severity service failures, consumers respond more favorably to recovery services provided by humans compared to those provided by chatbots, regardless of the type of loss. However, for low-severity service failures, humans are more effective than chatbots in addressing service failures and promoting consumer forgiveness, particularly in the case of symbolic loss.

6.2. Theoretical Contributions

First, our study contributes to the existing literature on service failures and service recovery by examining how service recovery agents influence consumer forgiveness across different types of consumer loss. While much of the existing research on service failures primarily focuses on exploring recovery strategies, such as apologies, compensation, and explanations [6,7], our paper enriches this body of work by proposing that the use of chatbots to handle consumer complaints can serve as an effective method for promoting service recovery.

Second, the current study makes a significant contribution by extending research on human-AI interaction to service failure scenarios. Recent studies have focused on consumers’ acceptance of AI-driven services, marking a prominent stream of research in the field of human-AI interaction [81,82]. Numerous studies have highlighted consumers’ varied responses to human-provided versus AI-provided services. Building on these findings, our study explores consumer reactions to complaints handled by chatbots and human agents in service failure situations. While some research has examined the application of AI in managing service failures [83,84], few studies address the interactive effect of service recovery agents and consumer loss on consumer forgiveness. Our results show that chatbots only foster consumer forgiveness in utilitarian loss contexts, whereas they may have a counterproductive effect in symbolic loss contexts. In contrast, human agents promote consumer forgiveness in both symbolic and utilitarian loss contexts. Thus, our study identifies an important boundary condition under which consumers respond differently to human-provided and chatbot-provided services.

Third, this study identifies the mechanisms—perceived emotional support and perceived responsiveness—through which the interaction between recovery agent type and consumer loss influences consumer forgiveness in service failure contexts. While prior studies have identified several mediators like perceived justice and cognitive appraisal, these mediators rarely explain why agent type matters for recovery effectiveness across loss contexts. Perceived justice, for example, treats recovery agents as interchangeable vehicles for delivering fair outcomes, while cognitive appraisal focuses on loss severity rather than agent characteristics. In contrast, perceived emotional support and perceived responsiveness highlight that chatbots and humans differ in their ability to promote consumer forgiveness. This integration clarifies why loss type shapes different agents’ effectiveness in addressing service failures. We found that both chatbots and humans are capable of providing timely responses, which fosters consumer forgiveness in utilitarian loss contexts. However, humans are more adept at offering emotional support, thereby promoting consumer forgiveness in symbolic loss contexts. These findings contribute to a deeper understanding of why consumers respond differently to recovery services provided by chatbots and human agents under varying loss conditions.

Finally, by incorporating cognitive appraisal processes (controllability, stability, intentionality), our study identifies service failure severity as a contextual moderator that influences the interaction between recovery agent type and consumer loss. In low-severity service failures, recovery services provided by a human agent (vs. a chatbot) are more effective in facilitating consumer forgiveness, particularly in symbolic loss contexts. However, in high-severity failures, which trigger more intense cognitive appraisals, consumers exhibit more positive responses to recovery services provided by a human agent, regardless of the loss type.

6.3. Managerial Insights

Our findings offer actionable and nuanced managerial implications for service-oriented firms seeking to optimize service recovery strategies, balance cost efficiency, and enhance consumer forgiveness.

Firms should establish a dynamic service recovery routing system that prioritizes the alignment between recovery agents (human vs. chatbot), consumer loss type, and service failure severity. For symbolic loss scenarios, human agents remain irreplaceable. As our results confirm, humans outperform chatbots in providing perceived emotional support, which is a key mediator of forgiveness for symbolic loss. Managers should ensure that complaints involving terms such as “disrespect,” “rude,” or “humiliating” are automatically escalated to human agents. For utilitarian loss scenarios, chatbots serve as a cost-effective and equally effective alternative to humans. Our study shows that both agents achieve comparable levels of perceived responsiveness, the primary mediator of forgiveness for utilitarian losses. Firms can leverage chatbots to handle consumers’ complaints, as they offer 24/7 availability and lower operational costs while meeting consumers’ core demand for timely, practical solutions [15,64]. Therefore, technicians can develop classification models that automatically distinguish between utilitarian and symbolic losses by analyzing complaint text, emotional expressions, and loss descriptions [85]. Moreover, to mitigate misclassification risks, chatbots must include a prominent “request human assistance” option, which allows consumers to override automated routing if they perceive unmet emotional needs. Regarding service failure severity, human agents are mandatory for high-severity incidents, regardless of loss type. High-severity failures trigger intense cognitive appraisals, with consumers perceiving the incident as less controllable, more stable, or intentional, which amplifies the need for sincere, empathetic recovery [26,28]. Human agents excel at addressing these complex emotional and cognitive needs, whereas chatbots’ perceived lack of emotional intelligence may exacerbate dissatisfaction [11,75]. For low-severity failures, chatbots remain viable for utilitarian losses, while humans are still preferred for symbolic losses to maintain relational trust.

While chatbots cannot fully replicate human emotional intelligence, firms can optimize their design to improve performance in symbolic loss contexts, thus reducing the effectiveness gap with humans. First, anthropomorphism and emotional scripting are critical. Research shows that anthropomorphic design enhances perceived humanness and empathy in chatbots [23,45]. For symbolic loss scenarios, chatbot scripts can be tailored to include empathetic expressions, emoticons, and acknowledgment of emotional distress [25]. Such scripts align with interactional justice principles, addressing the core injustice of symbolic losses. Second, integrating humor and emotional reinforcement can further enhance perceived emotional support. Studies have shown that humorous or self-mocking communication in service recovery reduces negative emotions and increases forgiveness [8,25]. Chatbots can be programmed to use lighthearted humor in low-to-moderate severity symbolic loss scenarios. Additionally, chatbots can leverage facial emojis to convey empathy, as facial emojis have been shown to increase service recovery satisfaction compared to non-facial emojis [48]. Third, hybrid human-chatbot models offer a middle ground for symbolic loss contexts. Chatbots can serve as first-line responders to triage complaints, gather basic information, and provide initial apologies. If the chatbot detects emotional cues or receives a high-severity rating from the consumer, the interaction is seamlessly transferred to a human agent within 1–2 exchanges [44]. This model combines chatbots’ efficiency in routine tasks with humans’ strength in emotional recovery and minimizes consumer frustration while controlling costs.

Firms should adopt a data-driven approach to refine service recovery systems, using consumer feedback and interaction data to improve agent routing, chatbot performance, and training programs. First, feedback loops can be implemented post-recovery to measure perceived emotional support, responsiveness, and forgiveness. For example, consumers can be asked short surveys to identify gaps, such as chatbots failing to recognize symbolic losses or human agents lacking empathy. This data can be used to retrain chatbot algorithms and enhance human agent training. Second, predictive analytics can help anticipate failure severity and consumer responses. By analyzing factors such as complaint content, consumer history, and contextual details, firms can proactively route high-risk complaints to human agents to prevent dissatisfaction from escalating [2,86].

6.4. Limitations and Future Research

The current study has several limitations in three aspects, including experimental design, the robustness of the results, and the generalizability of the findings. First, in terms of experimental design, scenario-based experiments were employed to test our hypotheses, which may limit the external validity of our findings. Future research could conduct field experiments to validate and generalize our results in real-world settings. In addition, while the pretest and Study 3 confirmed statistically significant differences between the intended “low-severity” and “high-severity” conditions, both conditions clustered within the mid-to-high range of the severity scale. This suggests that the “low-severity” scenarios in the current study may not represent minor, easily overlooked service failures. Future research could develop more finely differentiated severity manipulations that can span the entire severity spectrum. Specifically, low-severity service failures could be defined as minimal non-material inconvenience—for example, an online retail platform sending a non-essential order confirmation email with a minor typo. In contrast, high-severity failures should involve substantial tangible losses or threats to essential consumer interests, such as the leakage of consumer personal information by hotels.

Second, in terms of the robustness of the results, individual differences, such as technology readiness, social anxiety, and anthropomorphism tendencies, may influence preferences for service recovery agents. Future research should investigate the impact of these individual differences on consumers’ preferences for human agents versus chatbots. Additionally, our study draws upon previous findings to suggest that anthropomorphic chatbots may perform as effectively as human agents in promoting consumer forgiveness for service failures. However, we have not empirically tested this assertion. Future research could manipulate the level of anthropomorphism in chatbots by using human-like avatars and names and examine the effects of chatbot anthropomorphism on consumer responses in service failure contexts.

Third, in terms of the generalizability of the findings, our study focused solely on data collected from China, which may limit the generalizability of our findings. In collectivist cultures like China, where social harmony and relational respect are highly valued [50], consumers may have heightened expectations for emotional support in symbolic loss contexts. In contrast, individualistic cultures may prioritize individual autonomy and efficiency, potentially leading to greater acceptance of chatbots in symbolic loss situations if they provide prompt and transparent recovery [17]. Therefore, future research should collect data from different cultural backgrounds (such as Western countries vs. China) and investigate the influence of cultural backgrounds on consumer responses in service failure contexts. Moreover, the perception of loss type and severity may vary across different experimental situations. For example, in the medical service scenario, consumers may have a particularly strong perception of the severity of the failure of doctors’ services. Therefore, our research findings may not be applicable to other service domains. Future research could consider verifying consumers’ preferences for service recovery agents in high-risk service domains (e.g., medical diagnosis and financial investment) when they encounter service failures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.F. and C.W.; methodology, S.L.; software, C.W.; validation, L.F., S.L. and C.W.; formal analysis, S.L.; investigation, C.W.; resources, S.L.; data curation, X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.; writing—review and editing, X.Z.; visualization, S.L.; supervision, L.F.; project administration, X.Z.; funding acquisition, L.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by [the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province] grant number [ZR2022MG015], [National Natural Science Foundation of China] grant number [72271082, 72571086], and [Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province] grant number [2408085J041].

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was exempt from ethical review and approval, while strictly abiding by the ethical guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The Institutional Review Board of Wuhan University of Technology waived the requirement for ethical review and approval in line with existing Chinese regulations. The research utilized fully anonymized data without personal identifiers such as names or national ID numbers. This meets the provisions of Article 16 of the Ethical Review Measures for Biomedical Research Involving Humans (National Health Commission Order No. 11, 2016), which grants exemption from ethical approval for studies using non-traceable anonymized data. Additionally, Article 4 of China’s Personal Information Protection Law (2021) legally classifies anonymized data outside the scope of personal information, freeing it from restrictions under personal data protection rules.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on the request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Experimental Stimuli Used in Study 1

Consider the process of checking into a “YOUJIA” hotel. Upon arrival at the reception desk, you request the assistance of the attendant to convey your luggage to your room.

The service staff had a cold and indifferent attitude and reluctantly helped you deliver your luggage to your room. You were dissatisfied with the service experience and complained on the YOUJIA online platform [symbolic loss condition].

You make a complaint and it is handled by a human/chatbot [human condition/chatbot condition] as shown in the picture below. The human/chatbot provides an acceptable solution which resolves your query.

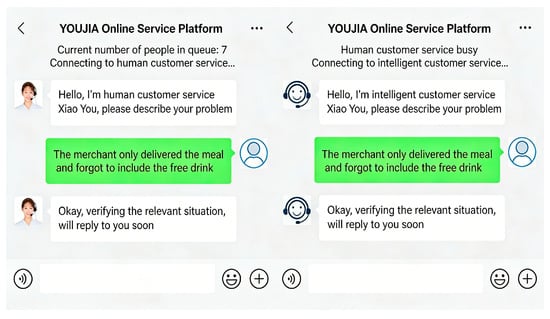

Figure A1.

Symbolic loss material in Study 1. ((Left) human condition; (Right) chatbot condition).

Figure A1.

Symbolic loss material in Study 1. ((Left) human condition; (Right) chatbot condition).

The service staff helped you deliver your luggage to your room. However, you found that the exterior of your suitcase was damaged. You were dissatisfied with the service experience and complained on the YOUJIA online platform [utilitarian loss condition].

You make a complaint and it is handled by a human/chatbot [human condition/chatbot condition] as shown in the picture below. The human/chatbot provides an acceptable solution which resolves your query.

Figure A2.

Utilitarian loss material in Study 1. ((Left) human condition; (Right) chatbot condition).

Figure A2.

Utilitarian loss material in Study 1. ((Left) human condition; (Right) chatbot condition).

Appendix A.2. Experimental Stimuli Used in Study 2

Consider the process of taking a taxi with complimentary Wi-Fi and air conditioning at the “YOUJIA” transportation platform.

Upon entering the vehicle, you found that the air conditioning was not turned on and then requested the driver to turn it on. However, rather than complying with this request, the driver just opened the car window instead of turning on the air conditioning. And then you made a second request. The driver agreed to your request and turned on the air conditioning. Upon arriving at the airport, you complained to the service provider via an app chat interface [symbolic loss condition].

You make a complaint and it is handled by a human/chatbot [human condition/chatbot condition] as shown in the picture below. The human/chatbot provides an acceptable solution which resolves your query.

Figure A3.

Symbolic loss material in Study 2. ((Left) the human condition; (Right) chatbot condition).

Figure A3.

Symbolic loss material in Study 2. ((Left) the human condition; (Right) chatbot condition).

Upon entering the vehicle, you found that there were no air conditioning or WiFi facilities in the taxi. Upon arriving at the airport, you complained to the service provider via an app chat interface. [utilitarian loss condition]

You make a complaint and it is handled by a human/chatbot [human condition/chatbot condition] as shown in the picture below. The human/chatbot provides an acceptable solution which resolves your query.

Figure A4.

Utilitarian loss material in Study 2. ((Left) the human condition; (Right) chatbot condition).

Figure A4.

Utilitarian loss material in Study 2. ((Left) the human condition; (Right) chatbot condition).

Appendix A.3. Experimental Stimuli Used in Study 3

Consider the process of ordering a takeaway at the “YOUJIA” takeaway platform [utilitarian loss condition].

Upon receipt of the takeout order, you found that the merchant did not deliver the free drink they promised. Given the unsatisfactory service, you complained to the YOUJIA takeaway platform [low-level service failure severity condition].

You make a complaint and it is handled by a human/chatbot [human condition/chatbot condition] as shown in the picture below. The human/chatbot provides an acceptable solution which resolves your query.

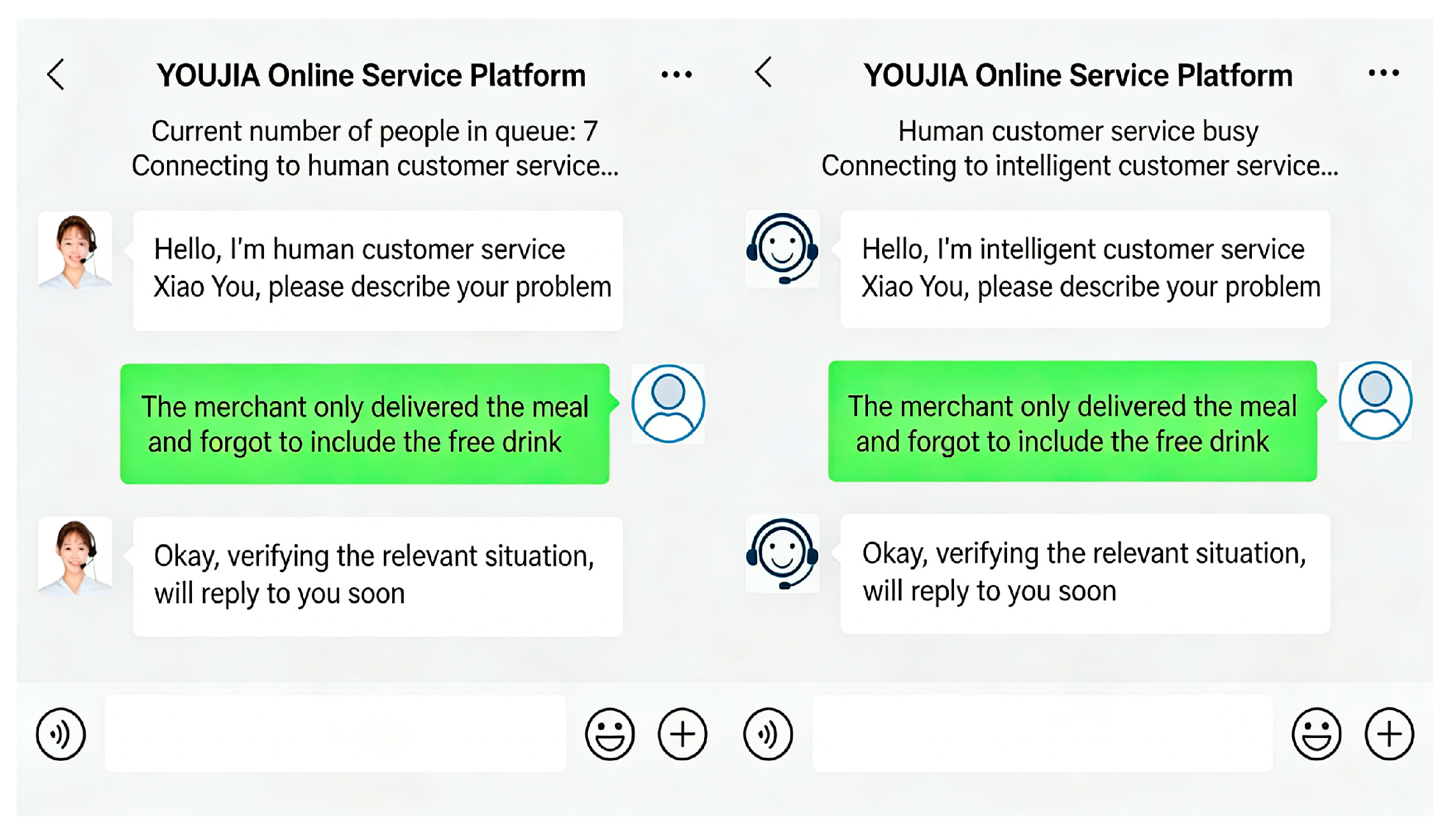

Figure A5.

Utilitarian loss × low service failure severity material in Study 3. ((Left) the human condition; (Right) chatbot condition).

Figure A5.

Utilitarian loss × low service failure severity material in Study 3. ((Left) the human condition; (Right) chatbot condition).

Upon receipt of the takeout order, you found that the merchant did not deliver the free drink they promised and the meal you paid. Given the unsatisfactory service, you complained to the YOUJIA takeaway platform [high-level service failure severity condition].

You make a complaint and it is handled by a human/chatbot [human condition/chatbot condition] as shown in the picture below. The human/chatbot provides an acceptable solution which resolves your query.

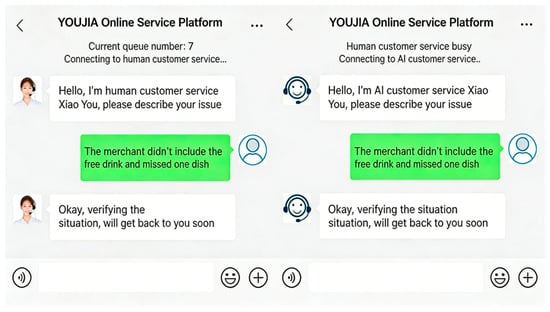

Figure A6.

Utilitarian loss × high service failure severity material in Study 3. ((Left) the human condition; (Right) chatbot condition).

Figure A6.

Utilitarian loss × high service failure severity material in Study 3. ((Left) the human condition; (Right) chatbot condition).

Consider the process of making a phone call to the restaurant to ask to make the food you ordered lighter at the “YOUJIA” takeaway platform. [symbolic loss condition]

You called the merchant to request to make your food lighter. The merchant impatiently agreed to my request and just said “ok” and then hung up immediately. Given the unsatisfactory service, you complained to the YOUJIA takeaway platform [low-level service failure severity condition].

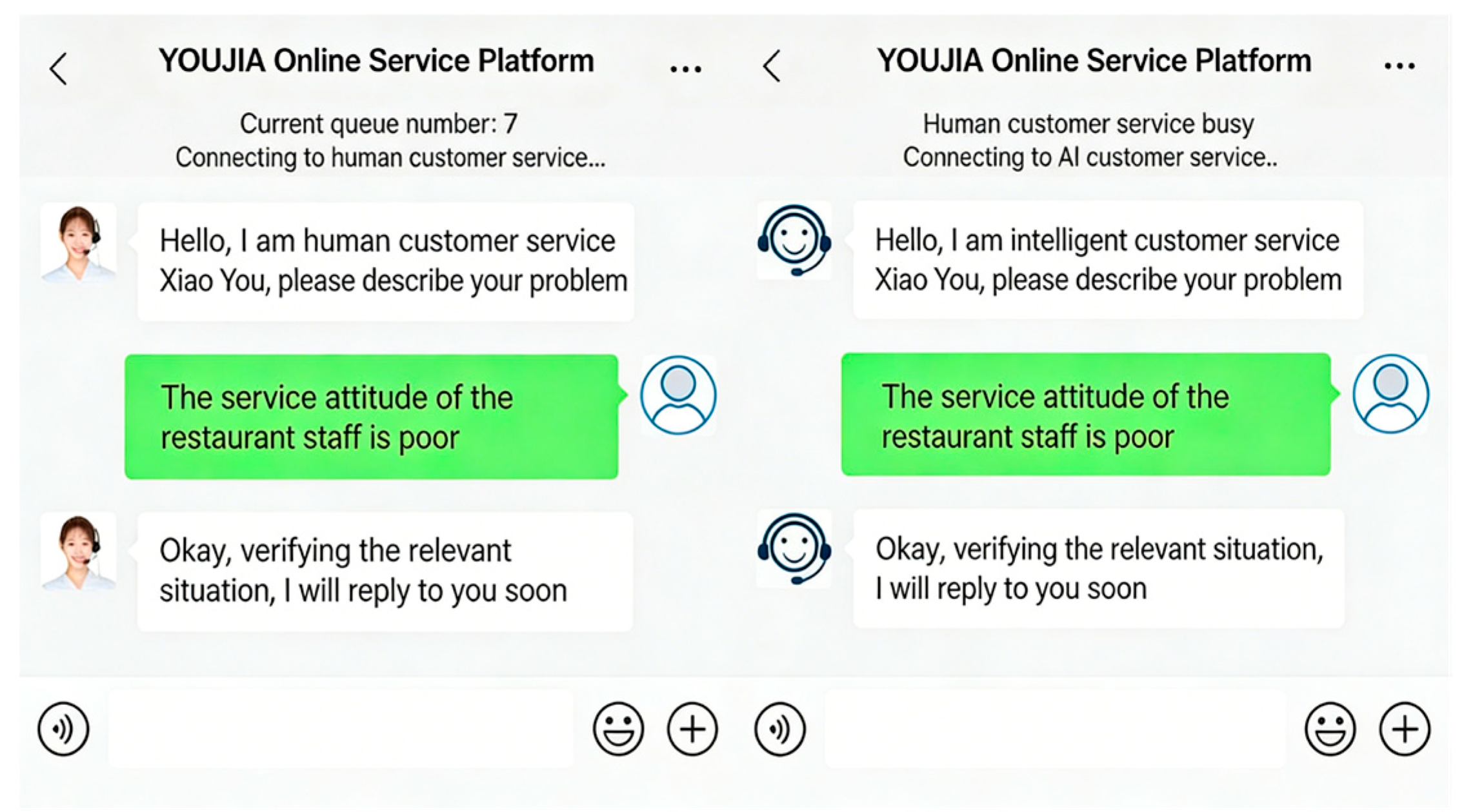

You make a complaint and it is handled by a human/chatbot [human condition/chatbot condition] as shown in the picture below. The human/chatbot provides an acceptable solution which resolves your query.

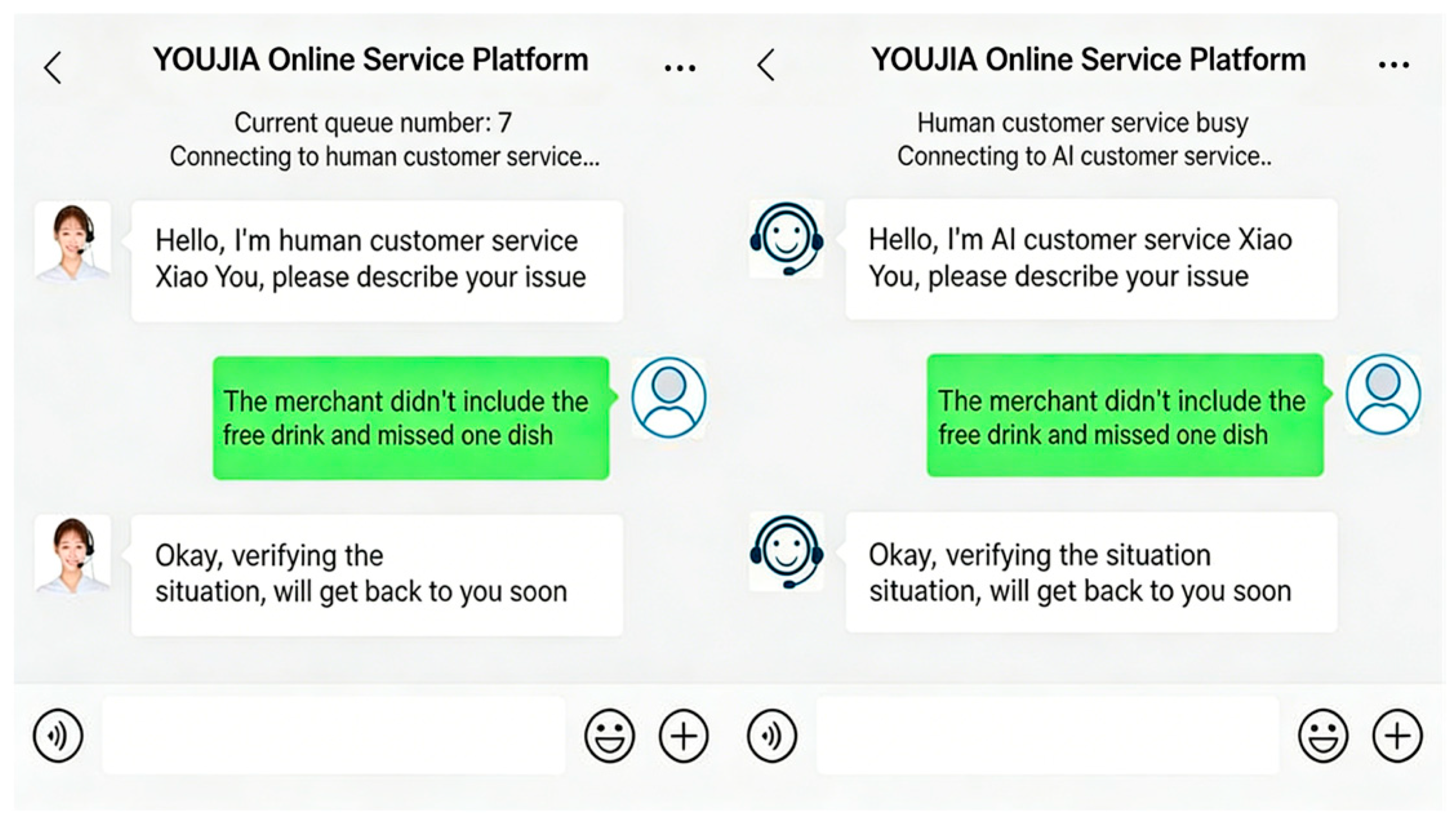

Figure A7.

Symbolic loss × low service failure severity material in Study 3. ((Left) the human condition; (Right) chatbot condition).

Figure A7.

Symbolic loss × low service failure severity material in Study 3. ((Left) the human condition; (Right) chatbot condition).

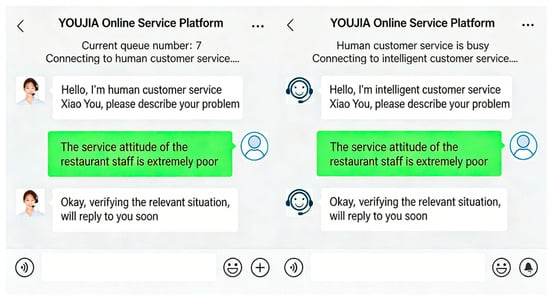

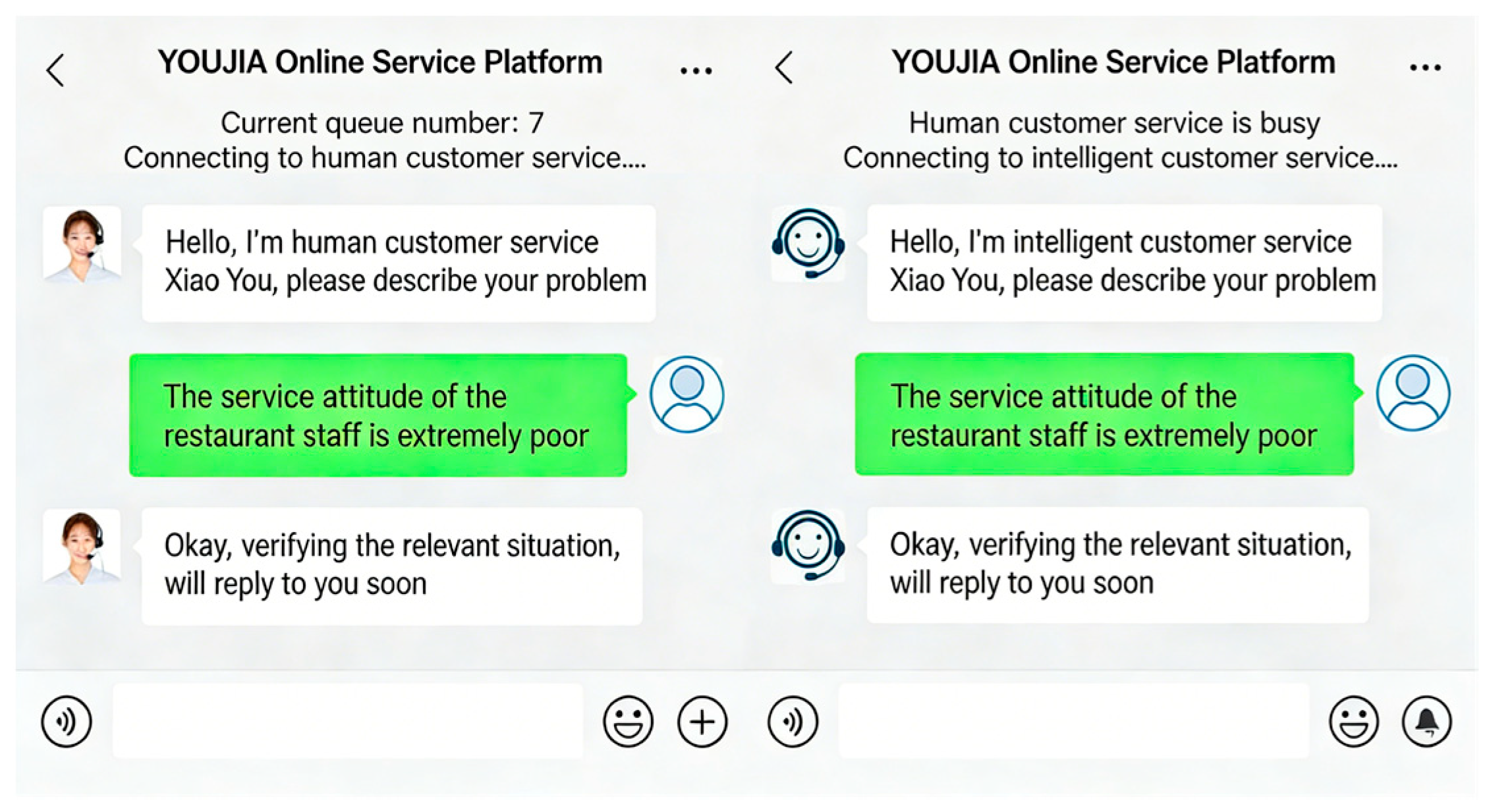

You called the merchant to request to make your food lighter. The merchant impatiently agreed to my request. And the manager said “Can you fill in the notes yourself next time? I am too busy!” and hung up immediately. Given the unsatisfactory service, you complained to the YOUJIA takeaway platform [high-level service failure severity condition].

You make a complaint and it is handled by a human/chatbot [human condition/chatbot condition] as shown in the picture below. The human/chatbot provides an acceptable solution which resolves your query.

Figure A8.

Symbolic loss × high service failure severity material in Study 3. ((Left) the human condition; (Right) chatbot condition).

Figure A8.

Symbolic loss × high service failure severity material in Study 3. ((Left) the human condition; (Right) chatbot condition).

Appendix B. Items

Table A1.

Items.

Table A1.

Items.

| Construct | Source | Items |

|---|---|---|

| Utilitarian loss | Smith et al., 1999 [77] |

|

| Symbolic loss | Smith et al., 1999 [77] |

|

| Consumer forgiveness | Fedorikhin et al., 2008 [87] |

|

| Emotional state | Townsen & Sood, 2012 [76] | I feel:

|

| Perceived responsiveness | Chen et al., 2024 [61] |

|

| Perceived emotional support | Gelbrich et al., 2021 [51] | Feedback from the agent makes me feel …

|

| Service failure severity | Ho et al., 2020 [11] | The above-mentioned service failure that happened to me was …

|

Appendix C

Appendix C.1. Confirmation Factor Analysis of Study 1

Table A2.

Confirmation Factor Analysis of Study 1.

Table A2.

Confirmation Factor Analysis of Study 1.

| Variable | Item | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbolic loss | SL1 | 0.900 | 0.904 | 0.758 | 0.926 |

| SL2 | 0.930 | ||||

| SL3 | 0.804 | ||||

| SL4 | 0.844 | ||||

| Utilitarian loss | UL1 | 0.808 | 0.848 | 0.692 | 0.899 |

| UL2 | 0.772 | ||||

| UL3 | 0.856 | ||||

| UL4 | 0.886 | ||||

| Consumer forgiveness | CF1 | 0.886 | 0.900 | 0.769 | 0.930 |

| CF2 | 0.901 | ||||

| CF3 | 0.856 | ||||

| CF4 | 0.865 |

Appendix C.2. Confirmation Factor Analysis of Study 2

Table A3.

Confirmation Factor Analysis of Study 2.

Table A3.

Confirmation Factor Analysis of Study 2.

| Variable | Item | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbolic loss | SL1 | 0.873 | 0.861 | 0.906 | 0.707 |

| SL2 | 0.818 | ||||

| SL3 | 0.824 | ||||

| SL4 | 0.847 | ||||

| Utilitarian loss | UL1 | 0.899 | 0.902 | 0.932 | 0.774 |

| UL2 | 0.816 | ||||

| UL3 | 0.889 | ||||

| UL4 | 0.913 | ||||

| Consumer forgiveness | CF1 | 0.877 | 0.917 | 0.941 | 0.801 |

| CF2 | 0.907 | ||||

| CF3 | 0.915 | ||||

| CF4 | 0.880 | ||||

| Perceived responsiveness | PR1 | 0.843 | 0.856 | 0.878 | 0.645 |

| PR2 | 0.869 | ||||

| PR3 | 0.787 | ||||

| PR4 | 0.703 | ||||

| Perceived emotional support | PE1 | 0.904 | 0.936 | 0.955 | 0.842 |

| PE2 | 0.920 | ||||

| PE3 | 0.917 | ||||

| PE4 | 0.929 |

Appendix C.3. Confirmation Factor Analysis of Study 3

Table A4.

Confirmation Factor Analysis of Study 3.

Table A4.

Confirmation Factor Analysis of Study 3.

| Variable | Item | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbolic loss | SL1 | 0.910 | 0.909 | 0.936 | 0.786 |

| SL2 | 0.926 | ||||

| SL3 | 0.858 | ||||

| SL4 | 0.851 | ||||

| Utilitarian loss | UL1 | 0.775 | 0.842 | 0.895 | 0.681 |

| UL2 | 0.799 | ||||

| UL3 | 0.882 | ||||

| UL4 | 0.841 | ||||

| Consumer forgiveness | CF1 | 0.865 | 0.890 | 0.924 | 0.754 |

| CF2 | 0.898 | ||||

| CF3 | 0.897 | ||||

| CF4 | 0.810 | ||||

| Service failure severity | SF1 | 0.838 | 0.841 | 0.904 | 0.759 |

| SF2 | 0.881 | ||||

| SF3 | 0.893 |

References

- Migacz, S.J.; Zou, S.; Petrick, J.F. The “Terminal” Effects of Service Failure on Airlines: Examining Service Recovery with Justice Theory. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, P.; Li, Z.; Mensah, I.A.; Omari-Sasu, A.Y. Consumer response to E-commerce service failure: Leveraging repurchase intentions through strategic recovery policies. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 82, 104137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cheng, P.; Ouyang, Z. How trust mediate the effects of perceived justice on loyalty: A study in the context of automotive recall in China. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Q. Does online service failure matter to offline customer loyalty in the integrated multi-channel context? The moderating effect of brand strength. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2018, 28, 774–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grégoire, Y.; Tripp, T.M.; Legoux, R. When customer love turns into lasting hate: The effects of relationship strength and time on customer revenge and avoidance. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelbrich, K.; Roschk, H. A meta-analysis of organizational complaint handling and customer responses. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Yoo, J.W.; Cho, Y.-E.; Park, H. Examining the impact of service robot communication styles on customer intimacy following service failure. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, J.; Pang, Q. Turning setbacks into smiles: Exploring the role of self-mocking strategies in consumers’ recovery satisfaction after e-commerce service failures. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison-Walker, L.J. The critical role of customer forgiveness in successful service recovery. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 95, 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, L.; Gul, E.R. Mediating role of customer forgiveness between perceived justice and satisfaction. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, T.H.; Tojib, D.; Tsarenko, Y. Human staff vs. service robot vs. fellow customer: Does it matter who helps your customer following a service failure incident? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 87, 102501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, S.; Kim, W.G.; Nimri, R. Conceptualizing the role of virtual service agents in service failure recovery: Guiding insights. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 123, 103889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, Q. Impact of AI-oriented live-streaming e-commerce service failures on consumer disengagement—Empirical evidence from China. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 1580–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kale, A.; Nguyen, T.; Harris, F.C.H., Jr.; Li, C.H.; Zhang, J.Y.; Ma, X.G. Provenance documentation to enable explainable and trustworthy AI: A literature review. Data Intell. 2023, 5, 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, G.; Scarpi, D.; Pantano, E. Artificial intelligence and the new forms of interaction: Who has the control when interacting with a chatbot? J. Bus. Res. 2021, 129, 878–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, Q.; Chang, Y. Humans as teammates: The signal of human–AI teaming enhances consumer acceptance of chatbots. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 76, 102771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longoni, C.; Cian, L. Artificial intelligence in utilitarian vs. hedonic contexts: The “word-of-machine” effect. J. Mark. 2022, 86, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovitch, D.G.; Stough, R.A.; Huang, D. Consumer reactions to chatbot versus human service: An investigation in the role of outcome valence and perceived empathy. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelo, N.; Bos, M.W.; Lehmann, D.R. Task-dependent algorithm aversion. J. Mark. Res. 2019, 56, 809–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Fan, X. The impact of customer’s loss and emotion on recovery expectation and complaining intention under the service failure circumstance. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2007, 10, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, B.; Yang, M.; Xie, L.; Zheng, Y. Sincerity or incompetence? The double-edged sword effect of sadness expression in chatbots service failure. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 86, 104325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Lv, Y.; Huang, W. How do consumers react to chatbots’ humorous emojis in service failures. Technol. Soc. 2023, 73, 102244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, X.; Zheng, W.; Wang, X. It’s better than nothing: The influence of service failures on user reusage intention in AI chatbot. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2024, 67, 101421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crolic, C.; Thomaz, F.; Hadi, R.; Stephen, A.T. Blame the bot: Anthropomorphism and anger in customer–chatbot interactions. J. Mark. 2022, 86, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Zhu, J.; Xie, Y.; Liang, C. Apologizing with a smile or crying face? Exploring the impact of emoji types on customer forgiveness within chatbots service recovery. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2025, 70, 101488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joireman, J.; Grégoire, Y.; Devezer, B.; Tripp, T.M. When do customers offer firms a ‘second chance’ following a double deviation? the impact of inferred firm motives on customer revenge and reconciliation. J. Retail. 2013, 89, 315–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, C.; Fang, S. Can beauty save service failures? The role of recovery employees’ physical attractiveness in the tourism industry. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, D.; Ma, B.; Wang, H. The relative impact of advertising and referral reward programs on the post-consumption evaluations in the context of service failure. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 65, 102849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tih, S.; Wong, K.-K.; Lynn, G.S.; Reilly, R.R. Prototyping, customer involvement, and speed of information dissemination in new product success. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2016, 31, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akarsu, T.N.; Marvi, R.; Foroudi, P. Service failure research in the hospitality and tourism industry: A synopsis of past, present and future dynamics from 2001 to 2020. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 35, 186–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sann, R.; Lai, P.-C. Understanding homophily of service failure within the hotel guest cycle: Applying NLP-aspect-based sentiment analysis to the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 91, 102678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Mattila, A.S. The role of tie strength on consumer dissatisfaction responses. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; So, K.K.F. The evolution of service failure and recovery research in hospitality and tourism: An integrative review and future research directions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 111, 103457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C. A service quality model and its marketing implications. Eur. J. Mark. 1984, 18, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, B.A.; Browning, V. Complaining in cyberspace: The motives and forms of hotel guests’ complaints online. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2010, 19, 797–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joireman, J.; Grégoire, Y.; Tripp, T.M. Customer forgiveness following service failures. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2016, 10, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.D.; Attri, R.; Salam, M.A.; Yaqub, M.Z. Retail consumers’ conundrum: An in-depth qualitative study navigating the motivations and aversion of chatbots. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 82, 104147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietvorst, B.J.; Simmons, J.P.; Massey, C. Algorithm aversion: People erroneously avoid algorithms after seeing them err. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2015, 144, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, A.M.; Kim, T.; Duhachek, A. Bad news? send an AI. good news? send a human. J. Mark. 2021, 87, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunaratne, J.; Zalmanson, L.; Nov, O. The persuasive power of algorithmic and crowdsourced advice. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2018, 35, 1092–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin, G.; Lim, S.; Puntoni, S.; van Osselaer, S.M.J. Thumbs Up or Down: Consumer Reactions to Decisions by Algorithms Versus Humans. J. Mark. Res. 2021, 59, 696–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logg, J.M.; Minson, J.A.; Moore, D.A. Algorithm appreciation: People prefer algorithmic to human judgment. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2019, 151, 90–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, H.; Islam, A.K.M.N.; Luo, X.; Mikalef, P. Decoding algorithm appreciation: Unveiling the impact of familiarity with algorithms, tasks, and algorithm performance. Decis. Support Syst. 2024, 179, 114168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sands, S.; Campbell, C.; Plangger, K.; Pitt, L. Buffer bots: The role of virtual service agents in mitigating negative effects when service fails. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 2039–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, G.; Kim, K.K.; Kim, K. Enhancing service recovery satisfaction with chatbots: The role of humor and informal language. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 120, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, A.; Bhattacharya, S. Chatbots’ effectiveness in service recovery. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 76, 102679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhou, P.; Liang, C.; Zhao, S.; Lu, W. Affiliative or self-defeating? exploring the effect of humor types on customer forgiveness in the context of ai agents’ service failure. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 194, 115381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Yu, K. To facial or not to facial? From emoji to empathy in shaping customer satisfaction with chatbot service recovery. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2026, 89, 104633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Song, M.; Duan, Y.; Mou, J. Effects of different service failure types and recovery strategies on the consumer response mechanism of chatbots. Technol. Soc. 2022, 70, 102049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, J.N.; Worthington, E.L.; Utsey, S.O. Collectivism, Forgiveness, and Social Harmony. Couns. Psychol. 2009, 37, 821–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelbrich, K.; Hagel, J.; Orsingher, C. Emotional support from a digital assistant in technology-mediated services: Effects on customer satisfaction and behavioral persistence. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2021, 38, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horning, M.A. Interacting with news: Exploring the effects of modality and perceived responsiveness and control on news source credibility and enjoyment among second screen viewers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 73, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodhue, D.; Thompson, R.L. Task-technology fit and individual performance. MIS Q. 1995, 19, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Lu, Y.; Wang, B. Integrating TTF and UTAUT to explain mobile banking user adoption. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponsignon, F. Making the customer experience journey more hedonic in a traditionally utilitarian service context: A case study. J. Serv. Manag. 2023, 34, 294–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.; Randolph Ford, W.; Farreras, I.G. Real conversations with artificial intelligence: A comparison between human-human online conversations and human-chatbot conversations. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 49, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, J.; Yu-Buck, G.F. A natural apology is sincere: Understanding chatbots’ performance in symbolic recovery. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2023, 108, 103387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, S.Y.; Jin, S.C.; Jiang, S.Y. The limitations and ethical considerations of chatgpt. Data Intell. 2024, 6, 201–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azaria, A.; Azoulay, R.; Reches, S. Chatgpt is a remarkable tool-for experts. Data Intell. 2024, 6, 240–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heather, M.; Gray, K.; Wegner, D.M. Dimensions of mind perception. Science 2007, 315, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Dang, J.; Liu, L. After opening the black box: Meta-dehumanization matters in algorithm recommendation aversion. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 161, 108411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Lu, J.; Liu, L.; Feng, Y. The impact of emotional expression by artificial intelligence recommendation chatbots on perceived humanness and social interactivity. Decis. Support Syst. 2024, 187, 114347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, B.; Olya, H.; Ali, F.; Gannon, M.J. Understanding the influence of airport services cape on traveler dissatisfaction and misbehavior. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 1008–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, S.B.; Prakhya, S.; Sharma, A. Leveraging service recovery strategies to reduce customer churn in an emerging market. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 848–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]