Abstract

Grounded in Social Impact Theory, this study examines the effects of virtual experiences generated by Mere Virtual Presence (MVP), Mere Virtual Presence with Product Experience (MVPE), and pure brand websites on consumers’ brand attitudes and purchase intentions. Additionally, it explores the moderating roles of Consumers’ Need for Uniqueness (CNFU) and product type (search vs. experience products). This study adopts an experimental design with three brand website types (MVP brand communities, MVPE brand communities, and pure brand websites) and two product types to examine the hypothesis. Specifically, a 3 (brand website type) × 2 (product type) experimental design was implemented to examine the influence of brand website types across different scenarios of online marketing. The findings reveal significant insights into consumer brand marketing. Specifically, consumers with low CNFU exhibited higher brand attitudes and purchase intentions compared to those with high CNFU when engaging with search products in MVPE brand communities Furthermore, fan avatars within a virtual brand community can still influence consumer perceptions even without direct interaction. These insights contribute to the growing body of research on personalized marketing and offer practical strategies for leveraging eWOM to enhance consumer engagement and influence decision-making in the digital landscape.

1. Introduction

User-Generated Content (UGC) serves as a key driver of electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM), offering consumers authentic and relevant insights that significantly influence their decision-making processes [1]. While previous research has extensively examined text-based UGC, the role of presence—particularly as facilitated by visual elements such as photos and videos—remains underexplored in enhancing the effectiveness of eWOM marketing [2]. For instance, a written review of a vacation destination may provide a detailed description of its scenic beauty, yet photos or videos capturing visitors’ experiences can evoke a stronger sense of immersion, thereby increasing the persuasive impact of the recommendation [3]. This oversight in existing research highlights a critical gap, particularly as technological advancements now enable richer and more immersive online experiences that can enhance the perceived presence of products and services. To address this issue, Mere Virtual Presence (MVP) and Mere Virtual Presence with Product Experience (MVPE) virtual environments have been developed to allow users to passively observe static messages and images or actively engage in shared experiences, thus promoting a more comprehensive understanding of products [4,5]. These presence-driven interactions enrich consumer perceptions and foster trust, thereby amplifying the impact of UGC and eWOM beyond traditional text-based reviews. By exploring these innovations, this study aims to bridge the existing research gap by investigating how presence influences the effectiveness of UGC and eWOM within contemporary digital marketing.

Emotion has been widely recognized as a fundamental factor in word-of-mouth (WOM) marketing, shaping consumer behaviors such as brand attitudes and purchase intentions through its immediate psychological and evaluative effects [6]. When consumers browse online reviews or UGC on social media, emotional cues—such as tone, imagery, and sentiment—can elicit strong reactions that influence product perceptions and decision-making processes [7,8,9,10,11]. Gefen and Straub [12] further emphasize that consumers’ awareness of others’ online presence fosters trust, thereby strengthening purchase intentions by enhancing the perceived credibility of interactions. While prior studies have established the significance of emotion in traditional text-based UGC, the advent of presence-driven MVP and MVPE virtual environments introduces novel mechanisms for eliciting and intensifying emotional responses [13]. Building upon these insights, this study examines how presence-driven MVP and MVPE environments shape emotional responses, thereby deepening our understanding of eWOM’s influence on consumer behavior.

In addition to the affective consequences of presence-driven interactions, individual differences constitute a critical determinant of how consumers interpret and react to marketing stimuli. Among these traits, the Consumer Need for Uniqueness (CNFU) is particularly salient, as it reflects the degree to which individuals strive to establish distinctiveness through unique choices and behaviors that differentiate them from others [14]. CNFU influences how consumers engage with UGC and eWOM, with those exhibiting high CNFU typically seeking unconventional perspectives or niche products, whereas individuals with lower CNFU may gravitate toward mainstream opinions. These differences extend to virtual environments, where the emotional impact of presence-driven UGC—such as in MVP and MVPE contexts—may vary based on individual consumer traits [5]. Recognizing this interplay, this study incorporates CNFU as a moderating factor to examine how individual differences shape responses to eWOM and, consequently, influence brand attitudes and purchase intentions. This approach not only bridges the gap between consumer traits and eWOM engagement but also underscores the need for personalized marketing strategies that cater to diverse emotional and psychological profiles.

Building upon the discussion of CNFU as a key moderator of eWOM engagement, product type represents another critical determinant shaping consumer responses. Prior research suggests that product type significantly affects how consumers search for and evaluate information in UGC and eWOM contexts [15]. For instance, search products (e.g., electronics) often require detailed, objective reviews to facilitate decision-making, whereas experience products (e.g., travel or dining) benefit more from sensory-rich and emotionally engaging content that helps consumers visualize the experience [16]. In the context of MVP and MVPE environments, virtual presence further enhances the way consumers process product information by creating immersive, real-life experiences. While MVP environments provide social proof by showcasing the presence of other users, MVPE environments allow consumers to engage with a product’s intangible attributes through visual and interactive cues. By examining the interplay among product type, virtual presence, and consumer characteristics, this study addresses a critical gap in eWOM research and offers actionable insights for the development of more effective and tailored marketing strategies.

This study offers a comprehensive examination of the effects of MVP, MVPE, brand communities, and pure brand websites on brand attitudes and purchase intentions across diverse consumer segments and product categories. The findings indicate that consumers with varying levels of CNFU demonstrate distinct brand attitudes and purchase intentions when engaging with MVPE communities and exploring search products, thereby underscoring the importance of aligning virtual presence environments with consumer traits and product types. These insights contribute to the growing literature on personalized marketing and offer practical strategies for leveraging eWOM to enhance consumer engagement and influence decision-making within the digital landscape.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Social Impact Theory

The Social Impact Theory (SIT) [17] posits that different forms of social influence may manifest in an individual, including the phenomena and responses of social facilitation, social inhibition, conformity, and obedience. The magnitude of social impact perceived by individuals is determined by three key factors: (1) the number of individuals involved, (2) the immediacy of the effect, and (3) the strength of the social source. Specifically, when more individuals are present and the targets are situated in close temporal and spatial proximity, the influence exerted on individuals tends to be greater. Conversely, the strength of the influence source is shaped by attributes such as social status, capability, and the relationship between the target and the individual. As the strength of the influence (e.g., social status and power) increases, the impact on others also increases. Taken together, these principles suggest that the mere presence of others can generate varying levels of social impact and influence, exemplified by the phenomenon of Mere Presence [18].

2.2. Mere Presence (MP)

Individuals are inevitably influenced by others in group settings. According to the SIT, Mere Presence (MP) exerts influence within the same spatial and temporal context, irrespective of whether direct interaction occurs (see Table 1). Argo et al. [18] demonstrated that in an interaction-free physical consumption context, the size and proximity of a social group significantly affect consumers’ emotions and self-presentation behavior. Consequently, scholars have inferred that when customers share the same retail environment, the presence of other customers exerts varying degrees of influence on the focal customer’s overall evaluation of the store, thereby predicting acceptance and avoidance behaviors [19,20]. Moreover, the effect of MP extends into virtual contexts, facilitated by the real-time, interactive, and remote presence characteristics of online communities. (e.g., Mere Virtual Presence) [4,5].

2.3. Mere Virtual Presence (MVP)

With the advancement of online information technology, research indicates that increasing consumers’ awareness of the presence of others online (e.g., MVPs) on a webpage enhances trust and strengthens purchase intentions [12]. Naylor et al. [5] investigated the effects of interaction-free virtual environments and proposed a more comprehensive typology of MVPs. Accordingly, MVPs can be categorized into three types: (1) Similar MVPs; (2) Ambiguous MVPs; (3) Dissimilar MVPs. These categories are distinguished based on their effectiveness in revealing or presenting varying levels of brand supporters. Similar MVPs enable online consumers to perceive community members as similar to themselves, thereby fostering high-level inferential commonality among brand users. On the other hand, ambiguous MVPs lack explicit supporter characteristics or detailed product information within online shopping communities (see Table 1 for MVP characteristics). In such cases, consumers rely on perceived similarity, which can generate more favorable brand evaluations. In essence, the MVP concept extends the scope of Social Impact Theory (SIT) from physical to virtual environments, suggesting that ambiguous images or representative pictures may be employed by brand websites to symbolize online members (e.g., fan clubs) and achieve persuasive effects.

2.4. Virtual Product Experience (VPE)/Pure Brand Websites

Research on the Virtual Product Experience (VPE) research context indicates that pure brand websites provide a platform for displaying a brand’s products while effectively simulating experiences of using the product, thereby shaping consumer attitudes and behaviors [21,22,23,24]. Li et al. [24] categorized consumers’ experiences into three types of product experiences: direct, indirect, and virtual, based on the degree of interaction. Direct product experience involves consumers perceiving product characteristics through their sensory abilities, whereas indirect product experience refers to learning about product attributes via intermediaries such as brand websites. In this regard, the quality of brand websites and the level of brand awareness significantly influence consumer satisfaction and online loyalty [25,26]. VPE employs interactive media to simulate the shopping environment and creates immersive consumer experiences. According to Klein [23], VPEs can enhance consumers’ product experiences by enabling diversified perspectives, thereby producing effects comparable to direct experience. Furthermore, since VPEs generate a sense of telepresence, they surpass traditional advertising’s indirect product experience by leveraging the advantages of human–computer interaction (HCI) and human–human interaction (HHI) to present virtual products, thereby broadening their applicability [21,22,24].

2.5. Mere Virtual Presence with Product Experience (MVPE)

Extending Latané’s [17] SIT and Naylor et al.’s [5] MVP theory, this study posits that when individuals disseminate self-created content via online social media, regardless of the nature of the content or the form of its presentation, such dissemination intentionally or unintentionally shapes others’ perceptions of a brand’s products and related services. Naylor et al. [5] further demonstrated that when brand supporters only passively experience MP, their crowd characteristics may affect the target customers’ evaluations of the brand and their purchase intention. That is, the visual cues of MVP activate consumers’ social identity concerns and conformity tendencies, fostering the belief that “others are paying attention, so the brand is trustworthy.” Building on these findings, the present study develops the concept of Mere Virtual Presence with Product Experience (MVPE) within the aforementioned overarching theoretical framework.

Mere Virtual Presence with Exemplars (MVPE), which has emerged from psychosocial needs and social influences, is defined as a context in which consumers acquire knowledge about a product or brand via receiving information about it from others with undisclosed identities (e.g., images depicting them in close contact with the product or brand) while situated in a purely interaction-free virtual presence with other members of a brand community. By providing exemplars for observational learning, MVPE allows consumers to infer product characteristics based on the visual depiction of others’ image. Furthermore, driven by identification with these similar models, consumers can more profoundly link these inferred features to their own needs. Recent studies demonstrate that the display of other individuals’ icons or images within online communities conveys social cues to target customers, thereby inducing positive evaluative behavior [27,28,29]. In such contexts, users are free to join fan communities of brands and products of interest according to their own preferences after obtaining the relevant information.

This study explored the influence of pure brand websites, MVP, and MVPE environments on consumers’ brand attitude and purchase intention. The analysis is situated within the frameworks of SIT and VPE. To support subsequent experimental research, the characteristics of various virtual experiences were systematically compiled, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Various Virtual Experiences.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Various Virtual Experiences.

| Name | Definition | Characteristics | Case | Theoretical Basis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mere Presence (MP) | An act of communication does not occur between individuals in the same social environment. | N/A | All the audience in a concert hall | Social Impact Theory (Latané [17] + Argo, Dahl [18]) |

| Mere Visual Presence (MVP) | Members simply appear in the same virtual social platform environment, but no actual communication behavior occurs. |  | Online members of a shopping website. | Social Impact Theory (Latané [17] + Naylor et al. [5]) |

| Pure Brand Websites | Consumers use computers to search for product information, and then are encountered and learn about these products. |  | Products on the shopping website. | Virtual Product Experience Research Context (Li et al. [24]; Keng et al. [21,22]; Klein [23]) |

| Mere Virtual Presence with Product Experience (MVPE) | All members are simply present in the virtual social environment, browsing static messages about products shared by other members while being exposed to and learning about these products. |  | Members of the online brand community who have displayed their products. | This study merged the MVP and the VPE research context to extend the experience. |

2.6. Consumers’ Need for Uniqueness

The concept of Consumer Need for Uniqueness (CNFU) originated from the theory of uniqueness proposed by Snyder and Fromkin [14]. This theory suggests that individuals’ motivation for uniqueness arises from perceived similarity to others, while consumers pursue differentiation through product acquisition, usage, and processing. Such behaviors are conceptualized as outcomes of the interaction between motives for differentiation and conformity to societal norms [30,31].

Irmak et al. [32] examined CNFU from a social comparison theory perspective and classified the social comparison process into two types: projection and introjection. Projection refers to consumers using their preferences as a basis to predict or estimate the preferences of others, whereas introjection involves consumers aligning their preferences with those of others and adopting them as reference points for evaluation [33,34]. Irmak, et al. [32] further found that consumers with high uniqueness orientation are less likely to introject others’ preferences; they perceive themselves as more unique and actively express this distinctiveness in their consumption behaviors. In contrast, consumers with low CNFU are more susceptible to external influence, accepting others’ preferences and passively manifesting them in their consumption behaviors. Building on these insights, the present study investigates whether consumers with different levels of CNFU exhibit distinct brand attitudes and purchase intentions within MVP/MVPE brand communities pure brand websites.

2.7. Search Products and Experience Products

Research on VPE suggests that variations in product attributes and types, such as search versus experience products, significantly influence consumer attitudes and behavioral decisions [23,35]. Nelson [36] distinguished between search and experience attributes based on information acquisition costs, emphasizing that products may simultaneously embody both. Search products are characterized by the availability of sufficient information prior to purchase, enabling consumers to evaluate quality through observable features. Conversely, the attributes of experience products are discernible solely through direct consumption, wherein evaluation is contingent upon the emotional and sensory feedback elicited during use [37].

Contemporary consumers frequently rely on the Internet and social media to obtain product information and to review the consumption experiences of others prior to making purchase decisions. Keng et al. [21,22,38,39] demonstrate that VPE web design can enhance consumers’ experiential perceptions of a product, thereby approximating the effects of direct experience. Moreover, Klein [23] argues that transforming an experience product into a search product mitigates consumers’ perceived purchase risk. Building on this perspective, numerous scholars have employed the distinction between search and experience attributes to assess the Internet’s influence on marketing effectiveness [23,40,41]. Accordingly, the present study adopts the framework of search and experience products to examine how MVP/MVPE brand communities and pure brand websites shape consumers’ brand attitudes and purchase intentions.

2.8. Brand Attitude and Purchase Intention

Aaker [42] defined brand equity as the brand-related assets or liabilities associated with a brand name or logo. Brand equity may exert either positive or negative effects on a product or service [43,44]. Purchase intention refers to consumers’ subjective inclination toward a particular product and serves as a critical indicator for predicting consumer behavior [45]. Lardinoit and Derbaix [46] conceptualized purchase intention as the degree to which customers intend to purchase a specific product or brand, reflecting their propensity to act. Gwinner and Swanson [47] further described purchase intention as the strength of the relationship between customers and a particular product or service, as well as the likelihood of future purchases. Gefen and Straub [12] also suggest that enhancing the perception of MVPs on a webpage can increase consumer trust, thereby elevating purchase intention. Similarly, Moon et al. [48] found that social interaction between salespersons and consumers in virtual characters (e.g., avatars) effectively enhances consumers’ sense of social presence, shopping enjoyment, brand attitude, and purchase intention within virtual shopping environments.

3. Hypotheses and Research Framework

3.1. Hypotheses

3.1.1. The Effects of Consumers in MVP and MVPE

According to Latané’s SIT, the closer and more critical the proximity within the community, the greater the impact and the stronger the compliance. Gefen and Straub [12] suggested that increasing the perception of MVP on web pages can enhance consumer trust, thereby increasing purchase intention. When individuals are in an environment of information ambiguity, they employ anchoring theory as a cognitive tool [49]. Accordingly, this study posited that compared to pure brand websites that only provide product information, when individuals face members with information ambiguity in a brand community, there is an expectation for shared brand preferences and interests among MVP and MVPE brand community members. Such commonalities foster interpersonal relationships and enhance group cohesion. Hence, the following hypothesis was proposed:

H1.

Consumers in MVP and MVPE brand communities exhibit higher brand attitude and purchase intention than those on pure brand websites.

3.1.2. The Effects of High CNFU in MVP and MVPE

Huang et al. [50] emphasized that the difference in information between search and experience products can lead to significant differences in consumers’ browsing and purchasing behaviors. This finding implies that consumers with different levels of need for uniqueness exhibit significant differences in their purchasing behaviors. Online browsing behavior for search products tends to be shallow but broad, while information gathering for experience products leans toward deeper and narrower explorations. CNFU comprises three motivations: (1) Creative choices; (2) Unpopular choices; (3) Avoidance of similarity. People seek differentiation by avoiding products commonly used by others [51]. Consumers with high CNFU perceive themselves as unique and believe that introjection will threaten their uniqueness and may damage their self-esteem. As such, consumers with high CNFU are less likely to engage in introjected involvement. Moreover, they tend to be more reluctant to share evaluative word-of-mouth, as such endorsements can inadvertently drive mass adoption, thereby diminishing the product’s perceived uniqueness [32]. Additionally, consumers with high CNFU are less likely to be influenced by other people’s opinions or peer-to-peer communication to purchase a product [31,32,52].

In summary, consumers with high CNFU are less likely to readily express positive attitudes toward a particular product. Their expression of positive product evaluations is typically contingent upon a low perceived threat of social adoption or imitation by others [32]. Therefore, this study inferred that when consumers with high CNFU are exposed to different product types in MVP/MVPE brand communities or pure brand websites, they exhibit higher brand attitude and purchase intention on pure brand websites. Based on the above, this paper proposed the following hypotheses:

H2.

When consumers with high CNFU face different product types, their brand attitude and purchase intention generated from pure brand websites are higher than those from MVP and MVPE brand communities.

H2a.

When consumers with high CNFU face search products, their brand attitude and purchase intention generated from pure brand websites are higher than those from MVP and MVPE brand communities.

H2b.

When consumers with high CNFU face experience products, their brand attitude and purchase intention generated from pure brand websites are higher than those from MVP and MVPE brand communities.

3.1.3. The Effects of Low CNFU in MVP and MVPE

Consumers with low CNFU are more likely to reference others’ preferences when forming their own, indicating a higher propensity for decision-making introjection [32]. White and Argo [53] found that such consumers do not have a significant separation response (e.g., property disposal intentions or re-customization) toward symbolic products when imitated by others. Irmak et al. [32] further suggested that consumers with low CNFU rely heavily on the shared word-of-mouth and experiences of others as a basis for their own purchase decisions. Accordingly, employing popular means of communication (e.g., predictions based on high market share or social demands) can effectively attract consumers with low CNFU. The persona of fans and brand members within MVPE environments is typically ambiguous and inclusive, spanning various ages, genders, and social circles. This ambiguous member imagery lowers the psychological barriers to identification and amplifies the perceived social identity value for low-CNFU individuals. Consequently, these consumers are more likely to perceive brand affiliation as a low-threshold act of belonging, thereby facilitating their adoption of group consensus.

For search products, information is highly accessible within MVPE brand communities. Consumers with low CNFU perceive such products as widely accepted by the public, thereby generating stronger brand attitude and purchase intention in MVPE contexts. In contrast, for experience products—whose attributes are difficult to demonstrate and require direct consumption to be fully understood— consumers with low CNFU exhibit comparable brand attitudes and purchase intentions across both MVP and MVPE brand communities. Nevertheless, these factors are more significant than those of pure brand websites. Based on the above, this paper proposed the following hypotheses:

H3.

When consumers with low CNFU face different product types, their brand attitude and purchase intention differ between MVP and MVPE brand communities and pure brand websites.

H3a.

When consumers with low CNFU face search products, their brand attitude and purchase intention generated from MVPE brand communities are higher than those from MVP brand communities and pure brand websites.

H3b.

When consumers with low CNFU face experience products, their brand attitude and purchase intention generated from MVP and MVPE brand communities are similar but higher than those from pure brand websites.

Drawing on consumer socialization theory, Wang et al. [54] found that CNFU significantly affects consumers’ product evaluations and purchase intentions. Based on H2 and H3, different levels of CNFU may generate different brand attitudes and purchase intentions across different product types. Integrating the preceding literature review and study hypotheses, this study further infers that consumers with varying needs of uniqueness, when combined with varying types of products, exhibit a three-factor interaction effect on brand attitude and purchase intention within the contexts of virtual presence experience (MVP, MVPE) brand communities and pure brand websites. Based on the above, this paper proposed the following hypothesis:

H4.

With different levels of CNFU (high/low), the variation in product type (search/experience products) affects consumers’ brand attitude and purchase intention in MVP and MVPE brand communities and pure brand websites.

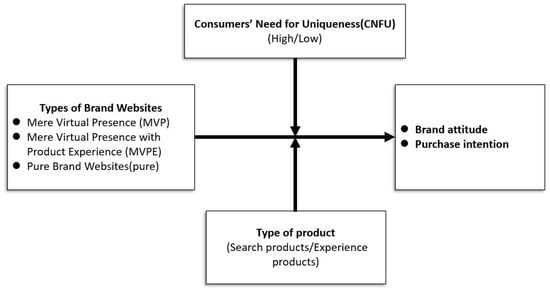

3.2. Research Framework

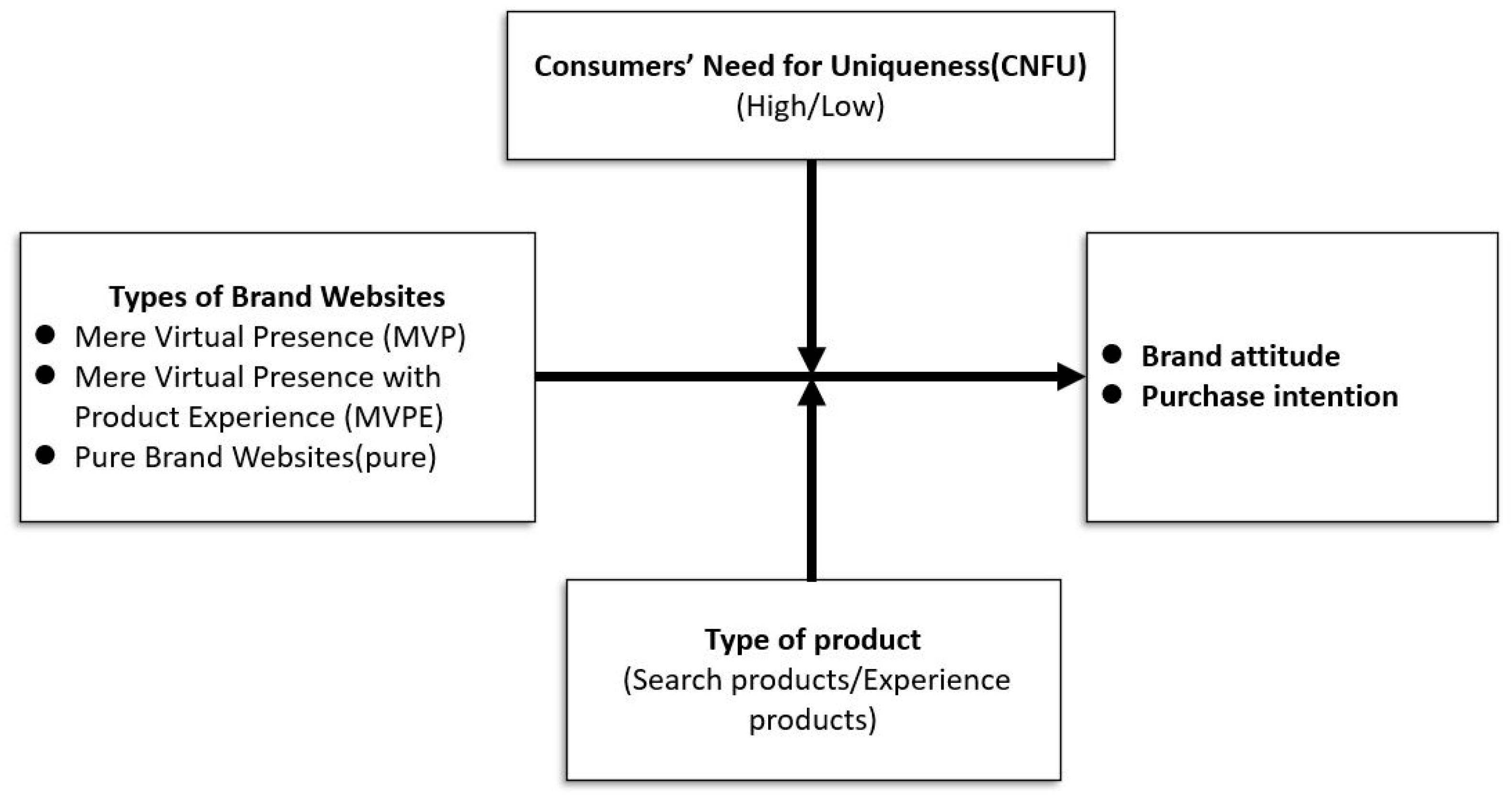

This study was grounded in the concept of interaction-free mere presence and extended its application to brand communities on Facebook, where the mere presence of others (e.g., fan images) can influence users. This phenomenon is referred to as MVP. Furthermore, when combining MVP with VPE (such as ambiguous personal photos with products), the concept of MVPE emerges. Scholars have suggested that the impact of the Internet on marketing effectiveness can be examined by categorizing search and experience products [23,40,41]. Tsai [55] and Irmak et al. [32] found that different levels of CNFU shape product attitudes, subsequently influencing purchase behavior. Accordingly, this study employed MVP brand communities, MVPE brand communities and pure brand websites as the independent variables, while product type and CNFU served as moderating variables to collectively assess their effects on the dependent variables of brand attitude and purchase intention. The research framework is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research Framework.

4. Methodology

4.1. Experimental Design and Sample Selection

This study developed an experimental design of three brand website types (MVP brand communities, MVPE brand communities, and pure brand websites) × two product types (search and experience products) which adopted an experimental method with web-based questionnaire and recruited Facebook users through the forums. Facebook was taken as the experimental website and individuals of all ages who had joined the Facebook brand community for over a year were recruited as the research subjects. Photos and text were supplemented to illustrate the experimental procedures. The total number of valid samples was 345 participants.

The experimental website comprised three online experience types and two product types (search and experience products) across six different types of experimental websites. The research subjects were randomly assigned by a computer after they logged in. Each subject only entered one of the six websites of experimental combination. The sample size of each combination is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Number of Valid Samples for Each Experimental Group.

4.2. Product Selection

This study analyzed the combined effects of brand website type and product type. Due to the multiple classifications of products, careful selection was made regarding each product. The primary product types considered in this study were search and experience products, as proposed by Nelson [36]. Following the experimental product selection methods for direct experience, indirect experience, and virtual experience outlined by Daugherty et al. [56], this study employed a 7-point Likert scale for measurement. A total of 30 participants of all ages who had been in Facebook online brand communities for more than one year were recruited as the pre-test sample. Based on the statistical results of the “Duncan’s Multiple Range Grouping” method with a significance level of α = 0.05, restaurant was chosen as the experience product for requiring a higher level of experiential involvement, while apparel was chosen as the search product for requiring medium high levels of information search and involvement.

4.3. Brand Selection

For the search product category (apparel), five brands with an intermediate number of followers on their brand fan pages were selected. For the experience product category (restaurant), five brands with comparable price ranges were selected. In total, ten brands were included in the pre-test. A 5-point Likert scale was employed to measure brand attitude. A total of 30 participants of all ages who had been in the Facebook online branding communities for more than one year were recruited as the pre-test sample. Based on the statistical results of the Duncan’s Multiple Range Grouping method with a significance level of α = 0.05, the search product Pazzo Apparel and the experience product Second Floor Restaurant were identified as brands of medium quality and familiarity. To prevent the influence of brand familiarity on the experimental outcomes, Pazzo was selected as the experimental brand for the search product, while Second Floor was selected as the experimental brand for the experience product category.

4.4. Mere Virtual Presence Experience Design

4.4.1. Experimental Design

The experimental environment in this study was primarily designed around the MVP/MVPE brand communities and pure brand websites. Distinct differences exist among these contexts. In MVPE brand communities, fan images consist of ambiguous identities with joint photos of individuals and products, accompanied by brand introductions, company posts, and responses. In MVP brand communities, fan images appear as highly blurred blue-and-white figures, likewise accompanied by brand introductions, company posts, and responses. By contrast, pure brand websites present only product photos and brand introductions without fan or member images or company posts/responses. Overall, the MVPE brand community encompasses MVP brand community content, while the MVP brand community includes the content of pure brand website content, indicating the following hierarchy: MVPE > MVP > pure brand website, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Differences in brand website type.

This study collectively referred to the MVP and MVPE brand communities as mere virtual presence experience brand communities. Due to the distinct definitions and contexts of mere virtual presence experience brand communities and pure brand websites, a comparable amount of brand and product information was incorporated for both search and experience products. Furthermore, the textual content was carefully designed to avoid information imbalances regarding the different types of brand websites.

4.4.2. Experimental Procedures

This study employed an experimental method using a web-based questionnaire. with Facebook serving as the experimental platform. Participants of all ages who had been in the Facebook brand community for more than one year were recruited. Each participant was required to log in to their Facebook accounts on their browsers and verify that their identities would not be duplicated before they were able to enter one of the randomly assigned experimental scenarios. The experiment manipulated the textual and visual content on the website. The participants were asked to complete a questionnaire after viewing the contextual web pages. The first part of the questionnaire assessed the manipulation of the mere virtual presence experience and product type, whereas the second part measured the participants’ needs for uniqueness, brand attitudes, purchase intentions, and basic demographic information. The participants were considered to have finished the experiment upon completing the questionnaire.

4.4.3. Manipulation Test

Reliability and Validity Analysis

This study developed six different contextual websites using brand website types (MVP/MVPE brand communities, pure brand websites) and product types (search/experience products) as the manipulation variables. Two types of CNFU (high/low) were used as the measurement variables of the within-group variation. Cronbach’s alpha reliability was used as the basis for the test. All the values obtained were greater than 0.7, which indicates that the study questionnaire has a high degree of consistency and stability (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Reliability Analysis.

Chi-Square Test of the Demographic Variables Among All Experimental Groups

To ensure that the six demographic variables (gender, age, education level, occupation, and the number and duration of Facebook fan groups joined) did not interfere with the experiment results, we used Pearson’s Chi-square test for independence. The results showed that the six demographic variables were not significantly different (p-value > 0.05) (see Table 4), meaning that the demographic variables did not interfere with the experimental results.

Table 4.

Chi-square Test for the Independence of Demographic Variables among Experimental Groups.

Manipulation Test of MVP, MVPE, and Product Type

MVP and MVPE served as the main manipulation variables in this study, and their validity was assessed using a 7-point Likert scale. The search and experience product types were also incorporated to manipulate the experimental scenarios, with effectiveness likewise measured on a 7-point Likert scale. The results of the one-way ANOVA (Table 5) and independent sample t-test (Table 6) indicate that MVP, MVPE, pure brand websites, and product type significantly differed. These findings indicate that participants were able to distinguish among MVP, MVPE, pure brand websites, and product types across the six experimental scenarios. Accordingly, the website scenarios constructed in this study are considered valid.

Table 5.

All Virtual Presence Experiences-One-way ANOVA.

Table 6.

Product Type-Independent Sample T-test.

4.4.4. Measuring Consumer Uniqueness

CNFU refers to pursuing traits that differentiate individuals from others through various behaviors and intentions. This study adopted a 17-item scale developed by Ruvio et al. [57]. Items deemed culturally irrelevant to Taiwan, such as ‘I have a wet bar in my kitchen,’ were removed, resulting in a revised 12-item scale. Responses were measured using a 5-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating the participants’ higher level of need for uniqueness. Following White and Argo’s [53] suggestion of using the median of the total score for the need for uniqueness as the differentiation benchmark. Participants were categorized into two groups: consumers with low CNFU (total score < 40) and consumers with high CNFU (total score ≥ 40). Table 7 presents the distribution of participants across the experimental groups after classification.

Table 7.

CNFU Distribution.

4.4.5. Measuring Brand Attitude

Brand attitude refers to consumers’ preferences for brand communities. This study employed a 4-item brand attitude scale developed by Raman [58] and measured the level of agreement using a 7-point Likert scale. The measurement items are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Brand Attitude Measurement Items.

4.4.6. Measuring Purchase Intention

This study measured purchase intention based on three items developed by Holzwarth et al. [59]. We calculated the level of agreement using a 7-point Likert scale. The measurement items are presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

Purchase Intention Measurement Items.

5. Results

This study categorized brand website types into three groups (MVP, MVPE, and pure brand websites) and product types into two groups (search products and experience products). Participants’ needs for uniqueness were divided into two groups (high/low). A one-way ANOVA was initially conducted to assess the main effects of brand website types. This was followed by a two-way ANOVA examining the combined effects of websites, product types, and CNFU. Finally, a three-way ANOVA was performed to identify potential interaction effects among the variables and to validate the proposed hypotheses testing results across the four groups.

5.1. Hypothesis 1 Testing

This study was grounded in SIT and interaction-free environments. Drawing on the presentation of Facebook brand community fan images and the degree of fan image ambiguity, brands were categorized into three website types: (1) MVP brand communities; (2) MVPE brand communities; (3) Pure brand websites. H1 posits that when consumers are in a mere virtual presence experience (MVP, MVPE) brand community, their brand attitudes and purchase intentions will be higher than those observed on pure brand websites. The analysis of the single-factor variances (Table 10) revealed significant differences in brand attitudes and purchase intentions across three different types of brand websites. MVP and MVPE brand communities demonstrated superior brand attitudes and purchase intentions compared to pure brand websites, thus supporting H1.

Table 10.

One-way ANOVA (Brand Website Type * Brand Attitude/Purchase Intention).

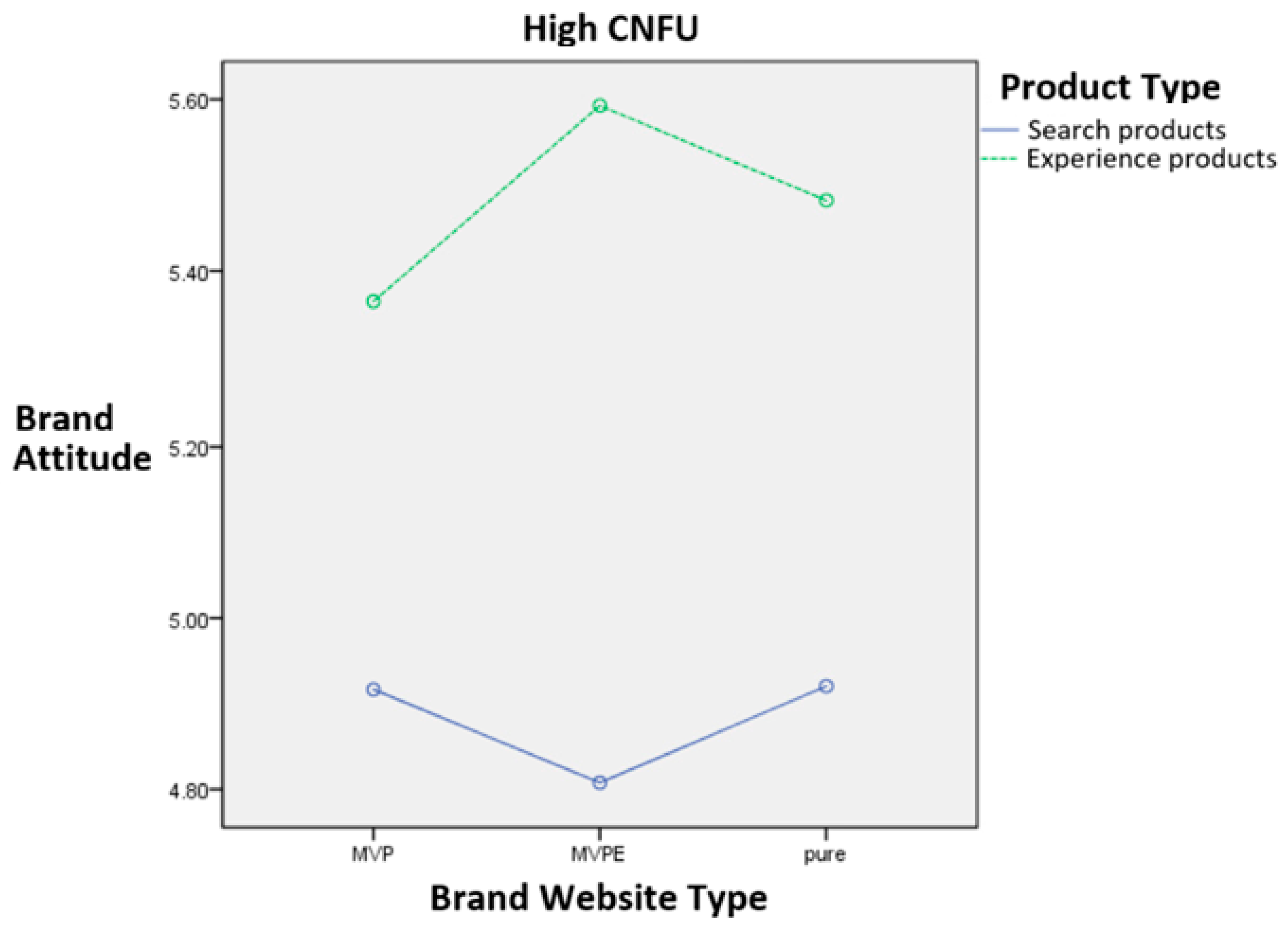

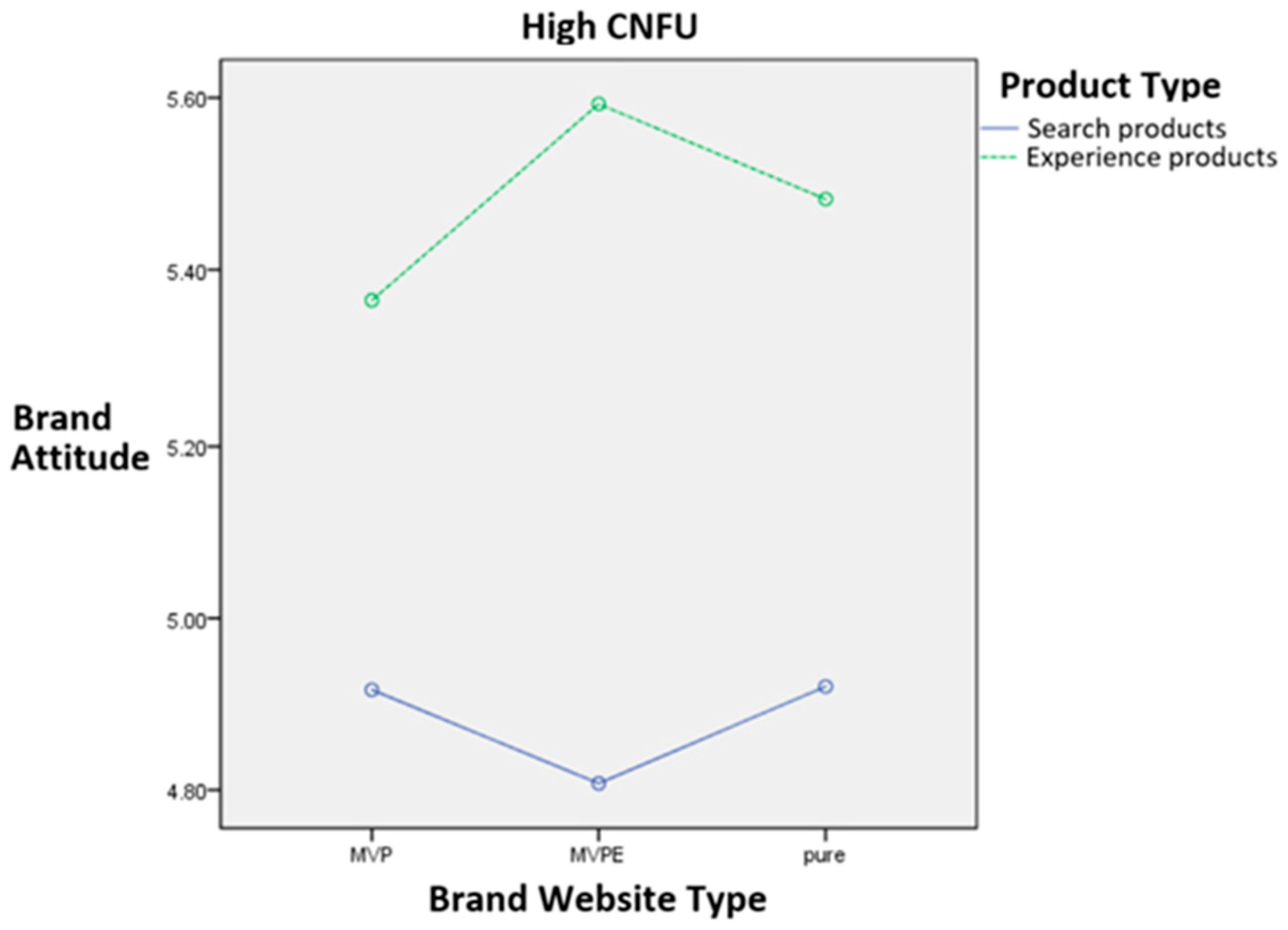

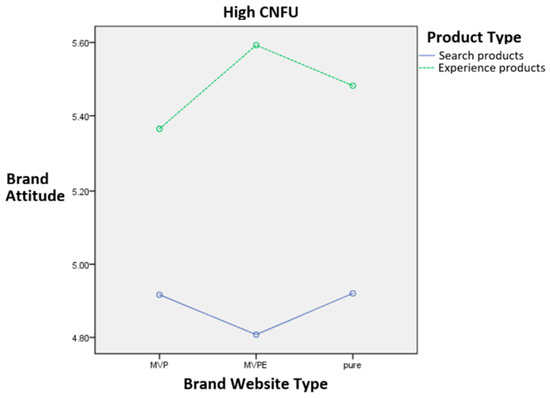

5.2. Hypothesis 2 Testing

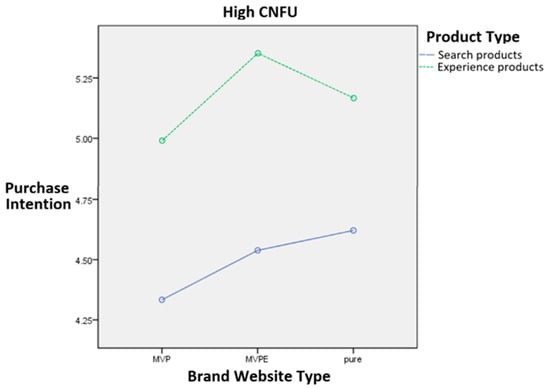

H2 examined whether the differences in brand website type and CNFU would affect consumer brand attitudes and purchase intentions as the main inference. Results from the two-way ANOVA (Table 11 and Table 12) indicated no significant interaction effect between the three groups of brand website types and product types (p = 0.796 > 0.05). Accordingly, participants with high CNFU exhibited no significant differences in brand attitude (p = 0.567 > 0.05) and purchase intention (p = 0.827 > 0.05) among MVP communities, MVPE brand communities, and pure brand websites when exposed to different product types. Figure 3 and Figure 4 illustrate that the participants with high CNFU exhibited higher brand attitude and purchase intention in the MVPE brand community when exposed to search products, thus H2a was not supported. On the other hand, when exposed to experience products, there was no significant difference in brand attitude or purchase intention between the MVP/MVPE brand communities, thus H2b was not supported. The findings also indicate that participants with high CNFU exhibited no differences in brand attitude and purchase intention across MVP/MVPE brand communities and pure brand websites when facing both search and experience products, thus H2 was not supported. This finding aligns with Irmak et al. [32], who noted that consumers with high CNFU are reluctant to provide positive evaluations of specific products (e.g., expressing evaluative word-of-mouth), as such behavior may lead to imitation by others, thus posing a threat to their uniqueness.

Table 11.

H2: Two-way ANOVA (Brand Website Type * Product Type).

Table 12.

H2: Interaction Effects (Brand Website Type * Product Type).

Figure 3.

Two-way ANOVA: High CNFU and brand attitude.

Figure 4.

Two-way ANOVA: High CNFU and purchase intention.

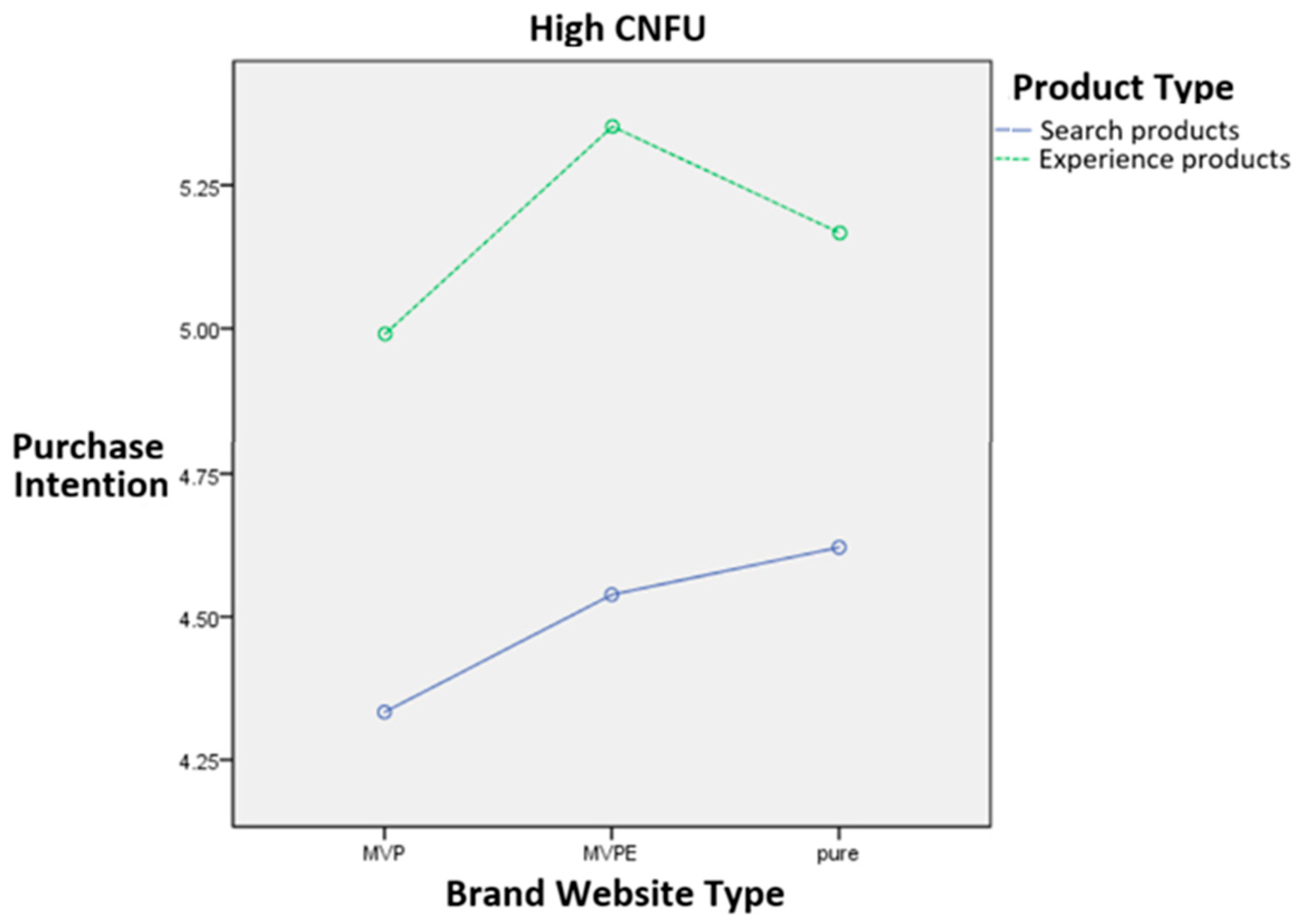

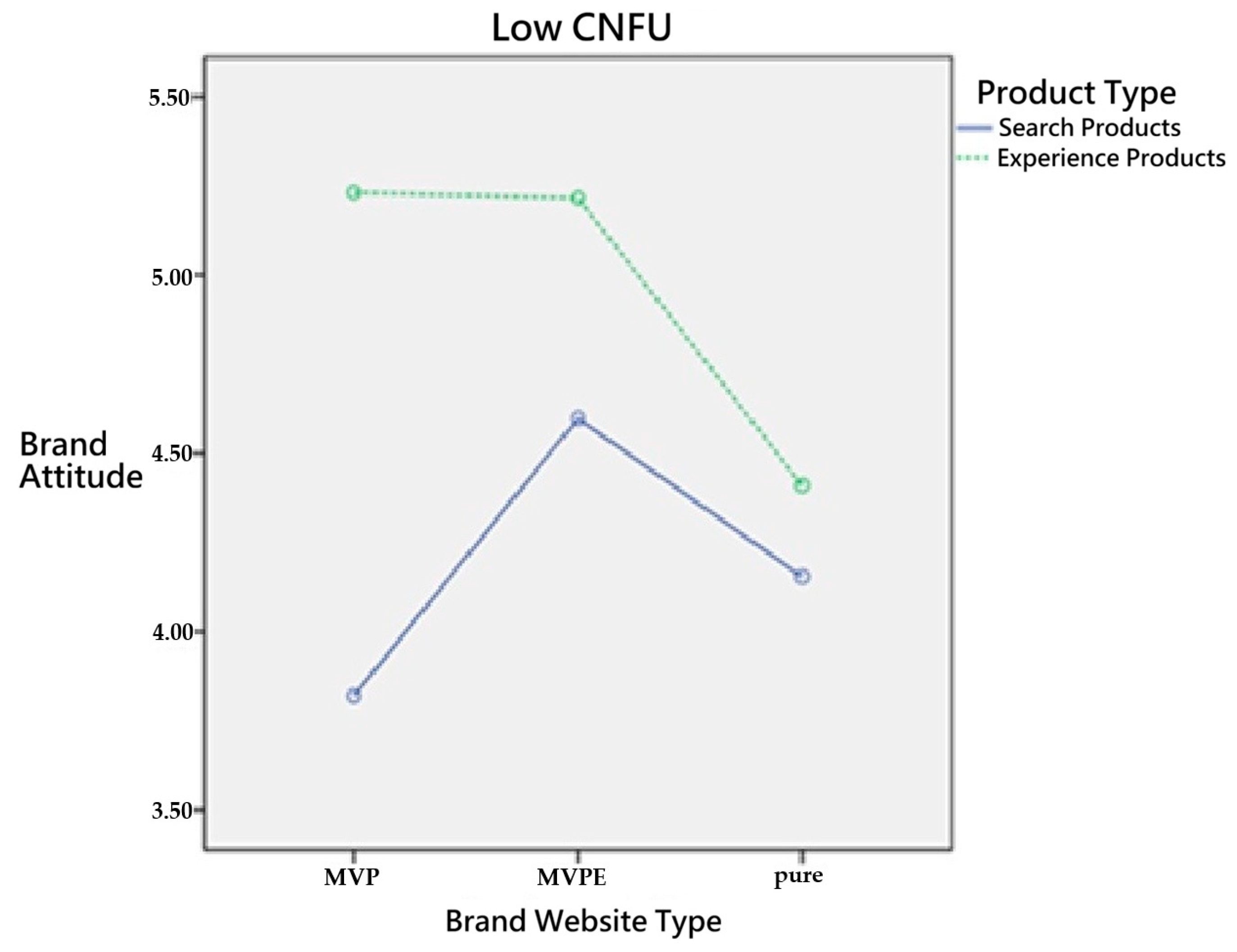

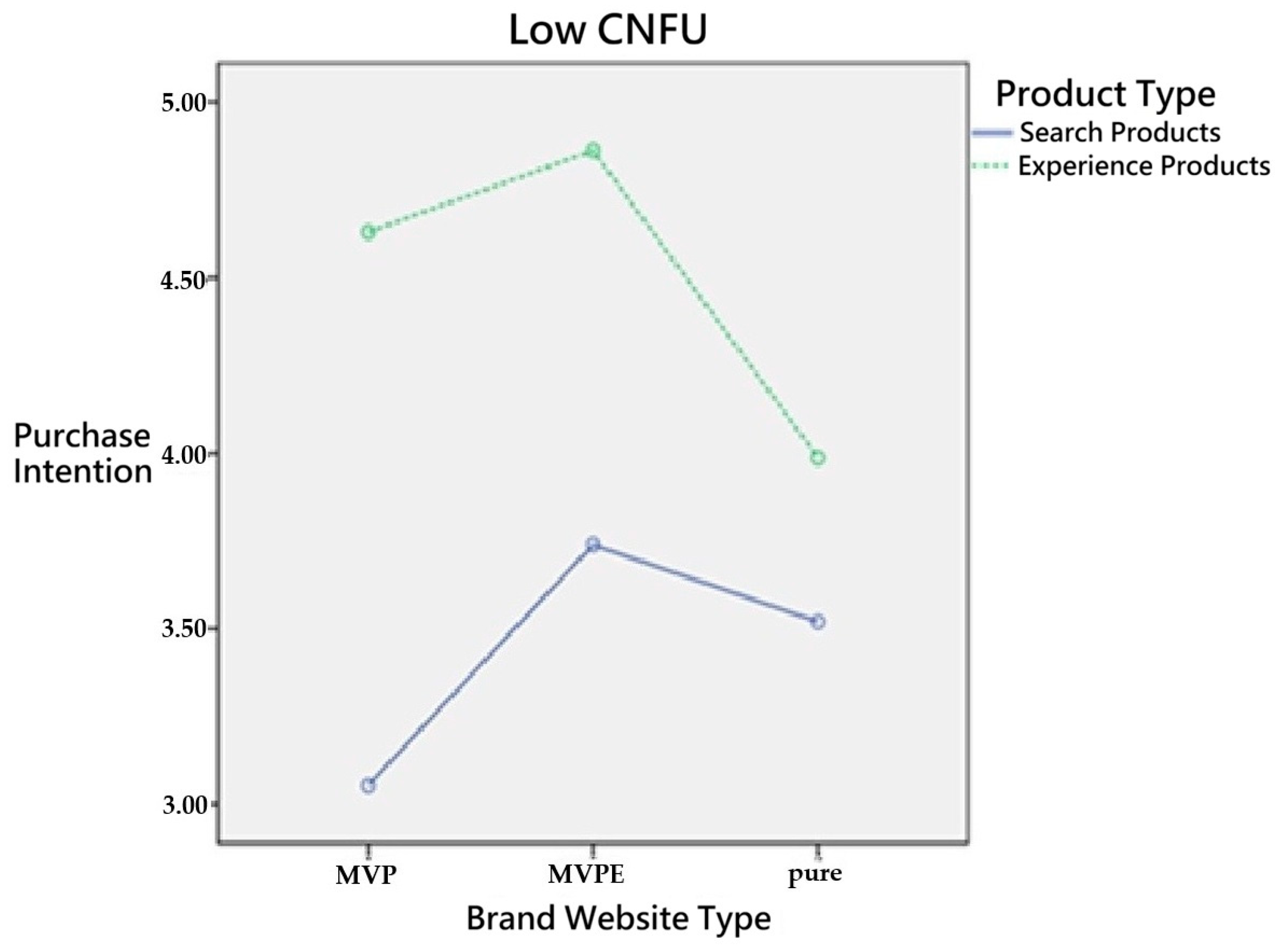

5.3. Hypothesis 3 Testing

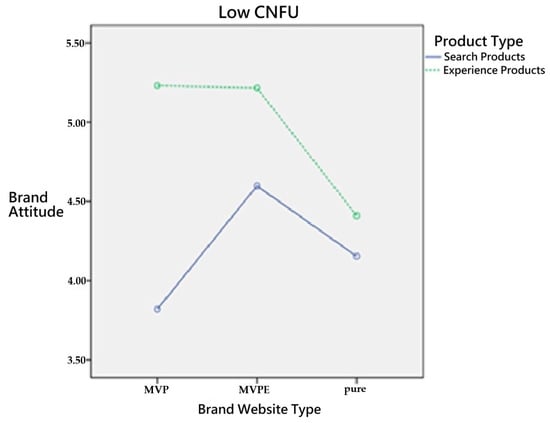

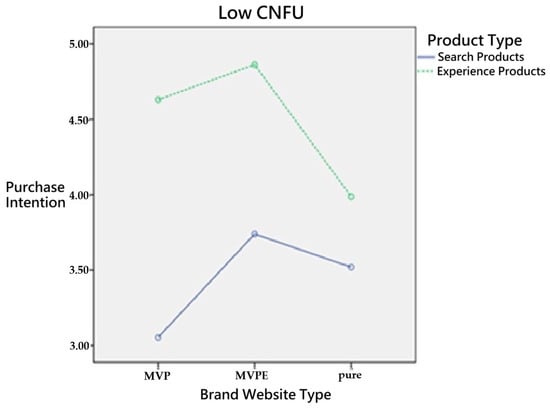

H3 examined whether there were differences in brand attitude and purchase intention among participants with low CNFU when exposed to different products in MVP/MVPE brand communities and pure brand websites. Results from the two-way ANOVA (Table 13 and Table 14) indicate a significant interaction effect between brand website type and product type on brand attitude and purchase intention (p = 0.003 < 0.05). Specifically, significant differences were observed in brand attitude (p = 0.001 < 0.05) and purchase intention (p = 0.044 < 0.05). Figure 5 and Figure 6 further illustrate that the participants with low CNFU exhibited higher brand attitude and purchase intention in the MVPE brand community when exposed to search products, thus supporting H3a. On the other hand, when exposed to experience products, there was no significant difference in brand attitude or purchase intention between the MVP/MVPE brand communities. However, both yielded higher brand attitudes and purchase intentions compared to pure brand websites, thus supporting H3b. Overall, these findings indicate that participants with low CNFU exhibited significant differences in brand attitude and purchase intention across MVP/MVPE brand communities and pure brand websites when facing both search and experience products, thus supporting H3.

Table 13.

H3: Two-way ANOVA (Brand Website Type * Product Type).

Table 14.

H3: Interaction Effect (Brand Website Type * Product Type).

Figure 5.

Two-way ANOVA: Low CNFU and brand attitude.

Figure 6.

Two-way ANOVA: Low CNFU and purchase intention.

5.4. Hypothesis 4 Testing

A three-way ANOVA was conducted using brand website type (three groups), product type (two groups), and CNFU (two groups) to investigate the moderating effects of product type and CNFU on the relationship between brand website type and brand attitude as well as purchase intention. Results from the three-way ANOVA (Table 15 and Table 16) indicate a significant three-way interaction effect between brand website type, product type, and CNFU was observed (p = 0.036 < 0.05). Moreover, the moderating effect of product type and CNFU on brand attitude was the most significant (p = 0.008 < 0.05). These findings suggest that product type and CNFU moderate the relationship between brand website type and participants’ brand attitudes, thereby partially supporting H4.

Table 15.

H4: Three-way ANOVA (Brand Website Type * Product Type * CNFU).

Table 16.

H4: Interaction Effects (Brand Website Type * Product Type * CNFU).

We also conducted MANOVA analyses using brand website type (three groups), product type (two groups), and CNFU (two groups) to explore the moderating effect of product type and CNFU on brand website type, brand attitude, and purchase intention. The results are consistent with the results of Three-way ANOVA, as shown in Table 17.

Table 17.

H4: MANOVA Interaction (Brand Website Type * Product Type * CNFU).

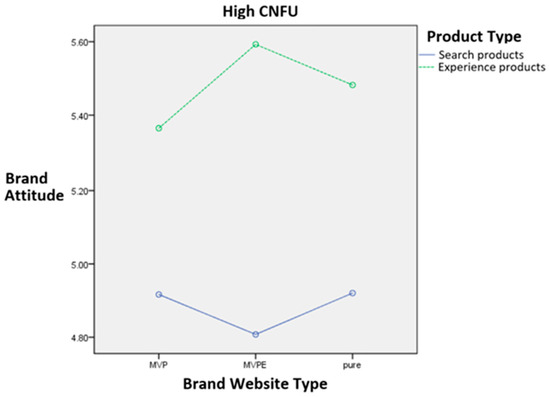

This study further analyzed the mutual interaction effects among brand website type, product type, and CNFU. As illustrated in Figure 7, when participants with high CNFU were paired with search products, their brand attitudes in the MVP brand community and the pure brand website did not significantly differ. Still, both were higher than in the MVPE brand community. In contrast, in the case of experiential products, the brand attitudes generated in the MVPE brand community were higher than in the other two.

Figure 7.

Three-way ANOVA: High CNFU and brand attitude.

The empirical findings of this study suggest that when individuals with different levels of CNFU face different product types and are simultaneously exposed to varying degrees of virtual presence, their brand attitudes will exhibit significant differences.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Discussion

This study recruited brand community members as the primary research subjects and examined the diverse patterns of interaction-free engagement on online community platforms. The findings indicate that varying the levels of fan imagery within brand communities—such as highly blurred blue-and-white images in MVP brand communities and clear images of fans holding products in MVPE brand communities—can effectively enhance consumers’ brand evaluations and subsequent purchase behaviors. Notably, even in the absence of direct interaction among brand community members, the social influence generated by their mere presence resulted in stronger effects for MVP and MVPE brand communities compared to pure brand websites, which lacked any visible community presence (H1). This finding underscores the role of anchoring theory in consumers’ decision-making processes, as individuals tend to rely on social cues when faced with ambiguous information in brand communities where members exhibit similar tastes or preferences [49]. Consequently, heuristic processing plays a crucial role in MVPE brand communities, where the perceived social presence surpasses the informational content of the product itself, leading to higher brand attitudes and purchase intentions [60].

The lack of significant effects of H2, H2a and H2b may be attributed to the inherent psychological traits of consumers with high CNFU, who typically refrain from readily expressing positive evaluations of conventional products. Characterized by a pervasive desire for distinctiveness and nonconformity, these individuals tend to exhibit counter-conformity behaviors, favoring highly innovative or novel offerings [32]. The product categories selected for this study—restaurants and clothing—may not have triggered a sufficiently strong perception of uniqueness or novelty to elicit a differential response. This suggests that the stimuli failed to activate the distinctiveness-seeking mechanisms of high-CNFU participants, resulting in the observed non-significant variances in both brand attitude and purchase intention.

Further analysis of consumer differences across the three types of brand websites (MVP, MVPE, and pure brand websites) reveals significant variations in the moderating effects of CNFU and product type on brand attitude. Compared to consumers with high CNFU, those with low CNFU were more easily engaged. When evaluating search products, these consumers exhibited higher brand attitudes and purchase intentions in MVPE brand communities (H3a). When evaluating experience products, their brand attitudes and purchase intentions in MVP and MVPE brand communities were comparable but consistently higher than those on pure brand websites (H3b). These findings suggest that consumers’ responses to different brand website formats are significantly influenced by their CNFU levels, with MVPE communities being particularly effective for those with lower CNFU. Accordingly, for apparel search-type products, we recommend leveraging MVPE brand communities to enhance persuasive effectiveness among consumers with low CNFU.

Moreover, across these three types of brand websites, this study confirms that CNFU moderates brand attitudes to varying degrees depending on the type of product being evaluated (H4). This highlights the necessity for brands to tailor their online brand community strategies based on consumers’ unique psychological traits and product types. By leveraging MVPE brand communities, companies can enhance consumer identification with the brand, thereby fostering more favorable brand attitudes and increased purchase intentions.

6.2. Academic Implications

Existing literature provides limited insight into the relationship between presence and WOM. This study demonstrates that even in the absence of direct interaction among brand community members—such as textual responses—the MVPE community, represented by fan avatars in a virtual environment, can still generate social impact and influence consumer perceptions. The findings contribute to SIT and the concept of MVP by further extending MVPE to explore social influence within social media platforms and examining the impact of virtual product experiences on consumer behavior. While consumers who obtain information from social media may not immediately develop purchase intentions, SIT suggests that emotional connections play a crucial role in shaping positive brand evaluations. Compared to traditional marketing tools such as television advertisements, the pull strategy facilitated by MVPE brand communities on social media fosters proactive communication, strengthens emotional bonds, and enhances consumer engagement. Psychologically, it alleviates pre-purchase uncertainty, instills a sense of security, and reinforces brand familiarity and trust.

Moreover, user profiles influence the WOM they generate. Consumers are more likely to provide authentic WOM within MVP/MVPE environments, where a strong sense of presence enhances their engagement. However, existing research has paid little attention to this phenomenon [2]. Addressing this gap, this study incorporates the concept of CNFU from a social comparison theory perspective, confirming that individuals with varying levels of CNFU exhibit distinct behavioral differences. The results indicate that brand attitudes and purchase intentions are significantly influenced by consumers’ unique needs. Furthermore, this study extends SIT by demonstrating that CNFU moderates consumer responses to search and experience products across MVP, MVPE brand communities, and pure brand websites. Specifically, consumers with low CNFU exhibited higher brand attitudes and purchase intentions when engaging with search products in MVPE brand communities, compared to the other two brand communities. In contrast, across all product categories, consumers with high CNFU demonstrated no significant differences in brand attitudes or purchase intentions among the three website types. This outcome is consistent with their heightened need for uniqueness and their greater tendency toward self-projection.

6.3. Practical Implications

This study provides several practical recommendations for businesses operating brand communities, with a focus on both company and customer perspectives. First, companies should carefully consider the key characteristics and types of products they offer. Second, a thorough understanding of the unique needs and characteristics of brand supporters is critical. This perspective aligns with the conclusion of Ahn and Lee [61] that the salience of different influence types varies depending on group similarity and individuals’ self-construal. The attributes of leading brand advocates can be analyzed based on a company’s brand personality, while consumers’ browsing history on a brand’s website can be tracked to assess their level of Consumer Need for Uniqueness (CNFU). Using this information, the website’s content can be adjusted to effectively present different product types. When targeting consumers with high CNFU, providing detailed product information is crucial in attracting their interest. Conversely, consumers with low CNFU are more likely to be influenced by popularity-driven messages or high market share cues [32].

Targeting CNFU presents a strategic challenge, as it represents an intrinsic psychological trait. Nevertheless, this study offers practical recommendations on how practitioners may operationalize precision targeting by leveraging lookalike modeling or identifying digital footprints (e.g., interest-based behaviors) as robust proxies for uniqueness motivations. For high CNFU consumers, marketing strategies should emphasize product differentiation and counter-mainstream appeal to resonate with their need for distinctiveness. Conversely, low CNFU consumers are more effectively engaged through offerings that highlight prevailing trends, as these individuals prioritize social validation and conformity. First, understanding customers and the types of products a company provides is critical. When a company website identifies high CNFU consumers, innovative and novel products are more likely to generate positive brand attitudes among them. These consumers are also more receptive to new product promotions without emphasis on popularity or commonality. Providing comprehensive brand and product information and employing ephemeral (time-limited) formats to create informational scarcity can enhance brand attractiveness for high CNFU consumers and reduce prepurchase uncertainty. Second, although H2 was not supported. For consumers with high CNFU who tend to emphasize uniqueness expression, a closer inspection of the results from H4 suggests that presenting restaurants—as prototypical experience goods—within MVPE website environments can nonetheless positively shape brand perception among this segment. Given the exploratory nature of this observation, future research should examine downstream consequences (e.g., engagement on niche products in the community) and potential mechanisms (e.g., motivation to develop unique contents). Third, when a company website identifies low CNFU consumers engaging with search products (e.g., apparel), fan images with low ambiguity in MVPE brand communities can provide a sense of security while reinforcing brand familiarity. Fourth, when low CNFU consumers engage with experiential products, pure brand websites should be avoided. These consumers perceive fan images in brand communities (MVP, MVPE) as role models and reference points for evaluation. Fan images also serve as indicators of product acceptance, thereby strengthening consumer trust. In other words, customers and brand community members become the most influential brand advocates, reinforcing the inseparable relationship between the brand community and the company. Fifth, Consumers may occasionally experience social anxiety or perceived overcrowding when participating in high-activity online brand communities. To alleviate this discomfort, this study recommends designing interaction-free contexts that enable pressure-free co-presence. In practice, brands can (i) suppress intrusive, real-time activity pop-ups (e.g., “X just purchased”) to reduce perceived message overload, and (ii) offer browse-only “quiet feeds” by hiding visible engagement counters (likes/views/shares) and disabling public comment sections. Importantly, private channels (e.g., direct messages) or confidential forms should be retained to accommodate non-public feedback.

7. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations and future research recommendations. First, we employed an online questionnaire method constrained by current technological limitations. The operational mechanisms designed in this experiment, such as preventing participants from returning to previous pages, could be improved by employing different research methods in future studies. Second, questionnaire distribution primarily targeted individuals in online communities, research institutes, and undergraduate programs. We recommend diversifying the sample selection by including participants from different fields. We also recommend expanding the research scope by including various products and product categories, such as homogeneous and heterogeneous products and utilitarian and hedonic products, to achieve more comprehensive research outcomes. Third, in addition to the three factors of social influence based on SIT, future studies should consider the impact of factors such as importance (e.g., assessing key platform usage intensity), time period (e.g., longitudinal research), positive and negative emotions (e.g., employing qualitative methods to uncover underlying mechanisms and contextual triggers), and brand choice on consumers’ brand attitudes and purchase intentions. Forth, Future research should further investigation into the effects across different platforms—particularly on anonymity, visually oriented and ephemeral platforms (e.g., Instagram Stories, TikTok)—to test whether MVP/MVPE effects produce comparable outcomes under different content formats and interaction dynamics. Fifth, the emergence of AI-generated social presence and virtual influencers has fundamentally redefined the nature of the ‘pure presence’ effect within online communities [62,63]. Consequently, future research should further investigate how the MVP and MVPE effects manifest and influence consumers within these AI-driven virtual environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-J.K., M.-Y.H. and M.-C.J.; Data curation, M.-Y.H. and M.-C.J. Formal analysis, C.-J.K. and M.-Y.H.; Methodology, C.-J.K., M.-Y.H. and M.-C.J.; Supervision, C.-J.K., M.-Y.H. and M.-C.J.; Writing—original draft, M.-Y.H. and M.-C.J.; Writing—review and editing, C.-J.K. and M.-Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to Legal Regulations (Our study does not involve medical interventions, identifiable personal data, or biological samples. According to Document No. 1010265079, titled Scope of Human Research Exempt from Ethics Committee Review, issued by the relevant authority in Taiwan, certain types of research are exempt from formal ethics review under specified conditions. Our research falls within the exempt categories outlined in this regulation, and therefore, in accordance with Regulation No. 1010265079, no formal ethical approval is required).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17573017.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to sincerely thank the editor and reviewers for their kind comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Redek, T.; Godnov, U. From data to decision: Distilling decision intelligence from user-generated content. Kybernetes 2024, 53, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, L.; Wang, L.; Huang, P. Discovering the evolution of online reviews: A bibliometric review. Electron. Mark. 2023, 33, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinko, R.; Stolk, P.; Furner, Z.; Almond, B. A picture is worth a thousand words: How images influence information quality and information load in online reviews. Electron. Mark. 2020, 30, 775–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreijns, K.; Xu, K.; Weidlich, J. Social presence: Conceptualization and measurement. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2022, 34, 139–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naylor, R.W.; Lamberton, C.P.; West, P.M. Beyond the “like” button: The impact of mere virtual presence on brand evaluations and purchase intentions in social media settings. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.S.; Hartwell, H.J.; Brown, L. The relationship between emotions, food consumption and meal acceptability when eating out of the home. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 30, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.; Milkman, K.L. What makes online content viral? J. Mark. Res. 2012, 49, 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, P.-Y.; Lei, H.-T.; Huang, S.-H.; Liao, T.H.; Lo, Y.-C.; Lo, C.-C. Effects of sentiment on recommendations in social network. Electron. Mark. 2019, 29, 253–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Chung, J.; Rao, V.R. The importance of functional and emotional content in online consumer reviews for product sales: Evidence from the mobile gaming market. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 130, 583–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Jenamani, M.; Thakkar, J.J.; Rana, N.P. Quantifying the effect of eWOM embedded consumer perceptions on sales: An integrated aspect-level sentiment analysis and panel data modeling approach. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 138, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirci, S.; Ling, C.-J.; Lee, D.-R.; Chen, C.-W. How personality traits affect customer empathy expression of social media ads and purchasing intention: A psychological perspective. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Straub, D.W. Consumer trust in B2C e-Commerce and the importance of social presence: Experiments in e-Products and e-Services. Omega 2004, 32, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-J. Antecedents and outcomes of virtual presence in online shopping: A perspective of SOR (Stimulus-Organism-Response) paradigm. Electron. Mark. 2023, 33, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.R.; Fromkin, H.L. Abnormality as a positive characteristic: The development and validation of a scale measuring need for uniqueness. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1977, 86, 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, M.; Sahney, S. Exploring the relationships between socialization agents, social media communication, online shopping experience, and pre-purchase search: A moderated model. Internet Res. 2022, 32, 536–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.; Lee, T. Product type and consumers’ perception of online consumer reviews. Electron. Mark. 2011, 21, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latané, B. The psychology of social impact. Am. Psychol. 1981, 36, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argo, J.J.; Dahl, D.W.; Manchanda, R.V. The influence of a mere social presence in a retail context. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocato, E.D.; Voorhees, C.M.; Baker, J. Understanding the influence of cues from other customers in the service experience: A scale development and validation. J. Retail. 2012, 88, 384–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderlund, M. Other customers in the retail environment and their impact on the customer’s evaluations of the retailer. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2011, 18, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keng, C.J.; Ting, H.Y.; Chen, Y.T. Effects of virtual-experience combinations on consumer-related “sense of virtual community”. Internet Res. 2011, 21, 408–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keng, C.-J.; Tran, V.-D.; Liao, T.-H.; Yao, C.-J.; Hsu, M.K. Sequential combination of consumer experiences and their impact on product knowledge and brand attitude: The moderating role of desire for unique consumer products. Internet Res. 2014, 24, 270–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, L.R. Evaluating the potential of interactive media through a new lens: Search versus experience goods. J. Bus. Res. 1998, 41, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Daugherty, T.; Biocca, F. Characteristics of virtual experience in electronic commerce: A protocol analysis. J. Interact. Mark. 2001, 15, 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, N.; Chi, N.; Nhung, D.; Ngan, N.; Phong, L. The influence of website brand equity, e-brand experience on e-loyalty: The mediating role of e-satisfaction. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S.I.; Kwon, W.-S.; Forsythe, S. Enhancing brand loyalty through brand experience: Application of online flow theory. In Proceedings of the International Textile and Apparel Association Annual Conference Proceedings; Iowa State University Digital Press: Ames, IA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Back, R.M.; Park, J.-Y.; Bufquin, D.; Nutta, M.W.; Lee, S.J. Effects of hotel website photograph size and human images on perceived transportation and behavioral intentions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Noone, B.M.; Robson, S.K. An exploration of the effects of photograph content, photograph source, and price on consumers’ online travel booking intentions. J. Travel Res. 2020, 59, 120–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Chen, L.; Santhanam, R. Will video be the next generation of e-commerce product reviews? Presentation format and the role of product type. Decis. Support Syst. 2015, 73, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.-T.; Shi, G.; Zheng, Y.-H. From Virtual Experience to Real Action: Efficiency–Flexibility Ambidexterity Fuels Virtual Reality Webrooming Behavior. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.T.; Bearden, W.O.; Hunter, G.L. Consumers’ need for uniqueness: Scale development and validation. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 28, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irmak, C.; Vallen, B.; Sen, S. You like what I like, but I don’t like what you like: Uniqueness motivations in product preferences. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 443–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codol, J.-P. Comparability and incomparability between oneself and others: Means of differentiation and comparison reference points. Eur. J. Cogn. Psychol. 1987, 7, 87–105. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger, J. The projective perception of the social world: A building block of social comparison processes. In Handbook of Social Comparison: Theory and Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2000; pp. 323–351. [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez, E.E. Effect of an e-retailer’s product category and social media platform selection on perceived quality of e-retail products. Electron. Mark. 2021, 31, 139–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P. Information and consumer behavior. J. Political Econ. 1970, 78, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.-Y.; Stahl, D.O.; Whinston, A.B. The Economics of Electronic Commerce; Macmillan Technical Publishing: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Keng, C.J.; Huang, T.L.; Zheng, L.J.; Hsu, M.K. Modeling service encounters and customer experiential value in retailing: An empirical investigation of shopping mall customers in Taiwan. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 2007, 18, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keng, C.-J.; Liao, T.-H.; Yang, Y.-I. The effects of sequential combinations of virtual experience, direct experience, and indirect experience: The moderating roles of need for touch and product involvement. Electron. Commer. Res. 2012, 12, 177–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, J.; Lynch, J.; Weitz, B.; Janiszewski, C.; Lutz, R.; Sawyer, A.; Wood, S. Interactive home shopping: Consumer, retailer, and manufacturer incentives to participate in electronic marketplaces. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, J.A.; Malter, A.J. E-(embodied) knowledge and e-commerce: How physiological factors affect online sales of experiential products. J. Consum. Psychol. 2003, 13, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A.; Equity, M.B. Capitalizing on the Value of a Brand Name; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; Volume 28, pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kapferer, J.N. The New Strategic Brand Management: Creating and Sustaining Brand Equity Long Term; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Willerton, R. Branding: Brand Strategy, Design and Implementation of Corporate and Product Identity. Tech. Commun. 2004, 51, 549–550. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Contemp. Sociol. 1977, 6, 244. [Google Scholar]

- Lardinoit, T.; Derbaix, C. Sponsorship and recall of sponsors. Psychol. Mark. 2001, 18, 167–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwinner, K.; Swanson, S.R. A model of fan identification: Antecedents and sponsorship outcomes. J. Serv. Mark. 2003, 17, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.H.; Kim, E.; Choi, S.M.; Sung, Y. Keep the social in social media: The role of social interaction in avatar-based virtual shopping. J. Interact. Advert. 2013, 13, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, R.W.; Lamberton, C.P.; Norton, D.A. Seeing ourselves in others: Reviewer ambiguity, egocentric anchoring, and persuasion. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 48, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Lurie, N.H.; Mitra, S. Searching for experience on the web: An empirical examination of consumer behavior for search and experience goods. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruvio, A. Unique like everybody else? The dual role of consumers’ need for uniqueness. Psychol. Mark. 2008, 25, 444–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.T.; McKenzie, K. The long-term predictive validity of the consumers’ need for uniqueness scale. J. Consum. Psychol. 2001, 10, 171–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Argo, J.J. When imitation doesn’t flatter: The role of consumer distinctiveness in responses to mimicry. J. Consum. Res. 2011, 38, 667–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Yu, C.; Wei, Y. Social media peer communication and impacts on purchase intentions: A consumer socialization framework. J. Interact. Mark. 2012, 26, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.-p. Impact of personal orientation on luxury-brand purchase value. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2005, 47, 427–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugherty, T.; Li, H.; Biocca, F. Consumer learning and the effects of virtual experience relative to indirect and direct product experience. Psychol. Mark. 2008, 25, 568–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruvio, A.; Shoham, A.; Makovec Brenčič, M. Consumers’ need for uniqueness: Short-form scale development and cross-cultural validation. Int. Mark. Rev. 2008, 25, 33–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, N.V. Determinants of Desired Exposure to Interactive Advertising; The University of Texas at Austin: Austin, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Holzwarth, M.; Janiszewski, C.; Neumann, M.M. The influence of avatars on online consumer shopping behavior. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, C.; Ghose, A.; Wiesenfeld, B. Examining the relationship between reviews and sales: The role of reviewer identity disclosure in electronic markets. Inf. Syst. Res. 2008, 19, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.; Lee, J. The impact of online reviews on consumers’ purchase intentions: Examining the social influence of online reviews, group similarity, and self-construal. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2024, 19, 1060–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavián, C.; Belk, R.W.; Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V. Automated social presence in AI: Avoiding consumer psychological tensions to improve service value. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 175, 114545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z. From human to virtual: Unmasking consumer switching intentions to virtual influencers by an integrated fsQCA and NCA method. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 78, 103715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.