Abstract

With the ubiquitous connectivity and exposure of social network service (SNS), the stressors it causes have received extensive attention in the academic community. Unlike previous studies, this research focuses on the cross-cultural dimension and explores the different effects of multiple SNS-generated stressors on user behavior outcomes. Based on the “Stressors-Strain-Outcome” (SSO) theoretical framework, we constructed a “technical stressors—exhaustion—reduced SNS usage intention” pathway to systematically investigate five types of technical stressors. These were perceived information overload, perceived social overload, perceived compulsive use, perceived privacy concern, and perceived role conflict. We introduce “fear of missing out” (FOMO) as a moderating variable to explore its moderating role in SNS exhaustion and reduced SNS usage intention. In this study, we took SNS users from China and the United States as the research subjects (338 samples from China and 346 samples from the United States), and conducted empirical tests using structural equation models and multiple comparative analyses. The results show that there are significant cultural differences between Chinese and American users in terms of the perceived intensity of technostress, the path of stress transmission, and the moderating effect of FOMO. Against the background of collectivist culture in China, perceived information overload, privacy concerns, and role conflicts have a significant positive impact on SNS exhaustion, and SNS exhaustion further positively drives the intention to reduce usage of SNS. However, the direct impacts of perceived social overload and perceived compulsive usage are not significant, and FOMO does not play a significant moderating role. In the context of the individualistic culture found in the United States, only perceived information overload and perceived social overload have a significant positive impact on SNS exhaustion, and FOMO significantly negatively moderates the relationship between exhaustion and reduced SNS usage intention, as high FOMO levels will strengthen the driving effect of exhaustion on reduced usage intention. The innovation this study exhibits lies in verifying the applicability of the SSO model in social media behavior research from a cross-cultural perspective, revealing the cultural boundaries of the FOMO moderating effect, and enriching the cross-cultural research system of reduced usage intention of SNS. The research results not only provide empirical support for a deep understanding of the psychological mechanisms of users’ SNS usage behaviors in different cultural backgrounds, but also offer important references that SNS enterprises can use to formulate differentiated operation strategies and optimize cross-cultural user experiences.

1. Introduction

Social Network Service (SNS) has been deeply embedded in modern social life and has become the core carrier by which individuals can build social connections, obtain information resources, and achieve self-expression [1]. From daily communication to group collaboration, and from information dissemination to cultural exchange, SNS’s connection function has continuously expanded its boundaries. However, at the same time, the technical pressure it triggers has gradually emerged: the impact of massive redundant information, the entanglement of high-frequency social demands, and the latent risk of privacy leakage. These stressors exceed individuals’ cognitive and emotional processing capabilities. They trigger negative psychological experiences such as anxiety and fatigue among users, and further prompt adjustments in usage behavior [2]. For instance, some users voluntarily reduce their login frequency due to information overload or avoid interactive behaviors as a result of social pressure. Such a phenomenon of SNS reduced usage intention has become an important topic in the study of user behavior in the digital age. However, the internal formation mechanism and cultural context differences require further analysis.

From a theoretical perspective, psychology’s Stressor-Strain-Outcome (SSO) model provides a key framework for analyzing this phenomenon. Koeske and Koeske [3] proposed this model in 1993. Its core logic argues that stressor sources in the environment (such as various burdens involved in the use of technology) do not directly act on behavioral outcomes, but rather indirectly promote behavioral adjustment by triggering individual stress responses (such as psychological burnout) [4]. In the SNS usage scenario, this logic manifests as follows: The technical stressors perceived by users, such as information overload and social overload, first transform into the stress state of SNS exhaustion, and eventually prompt users to intend to reduce usage [5,6]. However, most of the existing research based on the SSO model focuses on a single cultural context and lacks sufficient exploration of the boundary conditions in the stressor—stress transmission process. For instance, when faced with information overload, why do some users quickly fall into burnout and reduce usage, while others maintain frequent usage? Is this difference related to specific psychological traits or cultural backgrounds?

Fear of Missing Out (FOMO), as a typical psychological trait in SNS usage scenarios, provides an important perspective for answering the questions posed above [7]. FOMO refers to the persistent anxiety that individuals experience when they fear missing out on valuable experiences involving others, such as social activities and information updates. Its core feature is the fear of broken social connections, which are amplified by the real-time updates and wide connections of SNS [8,9]. Previous studies have confirmed that users with a high level of FOMO are more inclined to maintain a sense of social presence by using SNS frequently. Even when facing information overload or social pressure, they may delay or give up using it for adjustment due to their fear of missing out [10,11]. However, the existing research has two limitations: First, most of them regard FOMO as a single variable driving usage, ignoring its moderating role in the “string—outcome” path—that is, whether FOMO will change the intensity of the impact of exhaustion on the intention to reduce usage. Second, there is a lack of cross-cultural comparative analysis, which fails to reveal the differences in FOMO’s mechanism when it operates in different cultural backgrounds [12,13].

As a deep-seated framework shaping an individual’s cognition and behavior, culture’s influence on SNS usage behavior and the FOMO mechanism cannot and should not be ignored. According to Hofstede’s theory of cultural dimensions, China and the United States represent typical collectivist and individualist cultures, respectively, and there are significant differences between the two in terms of values, social logic, and behavioral norms [14]. In terms of values, American culture emphasizes individual autonomy and self-actualization, while social behaviors attend more to personal needs and boundaries [15]. Chinese culture, profoundly influenced by Confucianism, places greater emphasis on group connection and interpersonal harmony. Individuals have a stronger need to integrate into the collective, and social behaviors often center around maintaining relationship networks [16]. From the perspective of social practice, the family structure in the United States is loose, and individuals tend to make independent decisions after reaching adulthood. In social interactions, participants emphasize direct expression and privacy protection [17]. Chinese families are closely connected. In intergenerational interactions, filial piety and care are emphasized, and social communication tends to be more implicit, placing great emphasis on maintaining “face” [18].

This cultural difference is highly likely to reshape FOMO’s mechanism of action and pressure transmission path [19,20]. For instance, Chinese users in a collectivist culture, due to their greater need for a sense of social belonging, may generally have a higher level of FOMO. Will this common anxiety weaken their sensitivity to exhaustion and thereby suppress the intention to reduce usage? In an individualistic culture, American users pay more attention to personal experience and efficiency. Will FOMO become an amplifier of the exhaustion—reduced usage intention path? In other words, when people with high FOMO perceive burnout, will they more decisively reduce usage out of fear of missing key information? The answers to these questions will not only fill the gap in cross-cultural FOMO research, but also provide a cultural contextualization supplement for applying the SSO model in the field of digital behavior.

Based on the above research gaps, in this study we take SNS users in China and the United States as the research objects, combine the SSO model with the FOMO moderating variable, and construct a cross-cultural research framework of Technical Stressor—SNS Exhaustion—Reduced usage intention, aiming to achieve the following goals: (1) To have the system verify five types of technical stress sources, namely perceived information overload, perceived social overload, perceived compulsive use, perceived privacy concerns, and perceived role conflicts, and reduce the transmission mechanism of intention through SNS exhaustion use. (2) Explore the moderating role of FOMO in the SNS Exhaustion—Intent to Reduce Use path and compare the differences between Chinese and American samples; (3) From the perspective of cultural differences, explain the distinct characteristics of users in the two countries in terms of stress perception, burnout formation, and the role of FOMO. Correspondingly, the study proposed seven key hypotheses: H1–H5: Perceived information overload, social overload, compulsive use, privacy concern, and role conflict will each positively predict SNS exhaustion; H6: SNS exhaustion will positively predict reduced usage intention of SNS; H7: FOMO will moderate the relationship between SNS exhaustion and reduced usage intention, with the relationship being weaker for individuals with high FOMO. These hypotheses guide the subsequent research design, data collection, and empirical analysis, aiming to provide clear theoretical and empirical answers to the cross-cultural differences in SNS usage reduction behavior.

The theoretical and practical significance of this research can mainly be seen in three aspects. First, at the theoretical level, we expand the applicable boundaries of the SSO model in SNS behavior research by introducing FOMO moderating variables and cross-cultural comparisons, and enrich the integrated theoretical system of culture—psychology—behavior. Second, at the methodological level, we adopt the structural equation model and multi-group comparative analysis to provide a referenceable empirical paradigm for cross-cultural digital behavior research. Third, at the practical level, the results of this research can provide references that social media platforms can use to formulate differentiated operation strategies (such as designing different information push and social functions for Chinese and American users) and offer cross-cultural groups psychological adjustment suggestions for SNS usage (such as intervention plans to alleviate FOMO and exhaustion). Ultimately, our work will help users to achieve a healthier digital lifestyle, while promoting positive interaction and cultural exchange among SNS users from different cultural backgrounds.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

2.1. SSO Maodel

Koeske and Koeske [4] proposed the stressors-strain-outcome (SSO) framework, arguing that stressors may bring strain and induce adverse consequences that can negatively influence users. According to the SSO model, stressors are environmental stimuli that individuals perceive as troublesome, irritating, or disruptive [21]. Common stressors include overload, conflict, and invasion [22]. Strain and outcomes consist of an individual’s personal emotional and behavioral responses to stressors [23]. “Strain” refers to how someone reacts psychologically to the stressors disrupting their physiology, attention, and emotions [24]. Hence, the subsequent outcome is that a person’s behavior responds to the strain factors. This model reveals the stressors in an individual’s life that directly affect the strain variables that become the outcome variables.

2.1.1. Technostress as a Stressor

There is no doubt that the SNS is considered to be among the most useful tools for building and strengthening positive connections, promoting social participation and continuous interaction in modern society [25,26]. However, these new technologies and services can also produce negative effects, including technostress [27]. In a ubiquitous connected communication environment, SNS users must pay continuous attention to the overwhelming volume of social demands arising from SNS [28]. If people use various SNS aimlessly and excessively, they may feel stressed, fatigued, and anxious, which may bring about negative SNS uses [29]. This kind of SNS-induced stress is called technostress [22]. Technostress is viewed as a kind of “modern disease” that harms an individuals’ well-being with regards both to their work and to their family life [30].

Technostress has been conceptualized with diverse dimensions in existing literature [22,30]. For the context of SNS usage, we selected five core stressors based on two key criteria: direct relevance to SNS’s unique features [1,28,31,32] and empirical support for their impact on user exhaustion and usage behavior in social media research [32,33,34,35]. Specifically: Perceived information overload and social overload are the most frequently cited SNS-related stressors, tied to SNS’s information explosion and persistent social demands [31,32]; Perceived compulsive use reflects the addictive tendency of SNS, a critical trigger for psychological strain [33]; Perceived privacy concern addresses the inherent risk of personal information disclosure in SNS, a well-documented stressor for digital users [34]; Perceived role conflict arises from SNS’s multi-group interaction scenarios, where users face conflicting expectations across social circles [35]. These five stressors comprehensively cover cognitive (information overload), social (social overload, role conflict), behavioral (compulsive use), and security (privacy concern) dimensions of SNS-induced technostress, ensuring a holistic examination of stressor-strain relationships.

Information overload is defined as a condition in which the mass of information generated on SNS exceeds the capacity of individuals to process [36]. It may get worse, as information now spreads much more quickly than ever before as ICT continues to develop. Wang et al. [37] argue that users have difficulty in dealing with all the information they receive from smartphone-based SNS and are negatively emotionally influenced; they propose that this psychological reaction is SNS exhaustion.

Social overload described a situation in which an individual deals with many other users’ requests on SNS [38]. Smartphone-based SNS provides easy access to social media, allowing people to connect with each other anytime and anywhere [39]. Nevertheless, the need for people to provide social support for their friends on social networks has become a social norm [40]. Simultaneously, ubiquitous exposure makes users feel that they are provided with excessive social support; the virtual social requests exceed what they can process, leading to feelings of fatigue [41]. Fatigue arises when individuals’ resource inputs and outputs are not balanced.

Another technostress is users’ privacy concerns regarding SNS usage. Privacy concerns are activated when individuals feel that they are losing control of their personal information or are having their privacy invaded by unauthorized persons [33]. Since reducing the use of SNS can reduce the risk of information leakage, it is generally believed that privacy concerns are negatively correlated with users’ feelings and their use of SNS [37,42].

Perceived compulsive use is also considered a kind of technostress in SNS usage [43,44]. It considers perceptual beliefs that are of importance for the decision regarding whether technologies (such as SNS usage in this study) are used in voluntary settings. Li et al. [43] suggest that smartphones are sometimes frequently checked unnecessarily because users have become used to checking them. They may even be anxious at missing calls or not replying to messages timeously, contributing some compulsive acts like checking the phones frequently [44]. In addition, people may be stressed keeping their social links to others if they spend too much time on their devices, so it is necessary to study perceived compulsive use as an SNS usage behavior stressor. This study proposes that when users use SNS compulsively, they will experience exhaustion.

When communicating on SNS, role conflict reflects how much someone may feel incompatible with the role they expect to play on SNS [45]. Users’ self-disclosure of personal information may not meet the expectations of every social circle on their SNS [46]. However, if users present themselves on SNS in ways consistent with others’ expectations, they may fail to present their real thoughts or life to others, defeating their motive for using SNS in the first place [45]. Therefore, this study proposes that role conflict in the context of SNS will result in exhaustion.

2.1.2. SNS Exhaustion as a Strain

Salo et al. [47] describe strain as the individual’s adverse responses in relation to the technostressors. The exhaustion phenomenon, common in the age of mobile internet, is the feeling of being tired from overwork or pressure [48]. When users overuse social platforms by interacting with others on social media, scanning fragmented pieces of news or commenting on others, they may become exhausted easily. An individual’s subjective sense of fatigue stemming from their use of social media can be characterized as SNS exhaustion [49]. The increased number of social interactions in SNS may tire some users, so they may not wish to engage in it further. SNS exhaustion reflects such negative perceptions of individuals on SNS as stress [24], anxiety [50,51], tiredness [52], boredom [53], and depression [54].

2.1.3. Reduced SNS Usage Intention as an Outcome

Reduced usage intention is considered a self-regulatory SNS use behavior [55]. Reduced usage intention means that users endeavor to reduce the time they spend on SNS as much as possible until they believe that they would no longer overuse SNS [56]. Scholars have also proposed that reduced SNS usage is more realistic for many users than stopping use altogether; is more common than many other corrective actions; and that it can have many satisfying outcomes [57]. Therefore, this study proposes five kinds of technostress in SNS usage (perceived information overload, perceived social overload, perceived privacy concern, perceived compulsive, and perceived role conflict) as the technostressors that lead to SNS exhaustion. Consequently, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1:

Perceived information overload will positively influence SNS exhaustion.

H2:

Perceived social overload will positively influence SNS exhaustion.

H3:

Perceived compulsive use will positively influence SNS exhaustion.

H4:

Perceived privacy concern will positively influence SNS exhaustion.

H5:

Perceived role conflict will positively influence SNS exhaustion.

H6:

SNS exhaustion will positively influence the reduced usage intention of SNS.

2.2. Fear of Missing Out

FOMO refers to negative emotions like fears, concerns, and anxieties arising in people worried that they may fail to experience something or keep in touch with others in social interactions [58]. It is common in people anxious that others enjoy better lives or have more valuable experiences, which suggests that they strive to keep abreast of events in the lives of others and in the wider world [59]. Yin et al. [60] proposed that people with high level of FOMO spend more time on SNS in their life and when users experience a high level of FOMO in SNS use, they will show more need for social support; moreover, users with high level FOMO will show more addiction in SNS.

Hence, FOMO can be treated as a type of motivation or intention to connect with others. It is also a process of appraisal and the fulfilment of a psychological need in SNS use [11]. Consequently, this research proposes a new approach to FOMO influencing users’ SNS behavior: We suggest that even in a state of SNS exhaustion, users with high FOMO will show less intention to reduce SNS usage because of their greater need to connect with others. Users with low FOMO are expected to behave in the opposite manner. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H7:

FoMO would moderate the relation between SNS exhaustion and reduced usage intention of SNS, with the relation being stronger for people with low levels of FOMO.

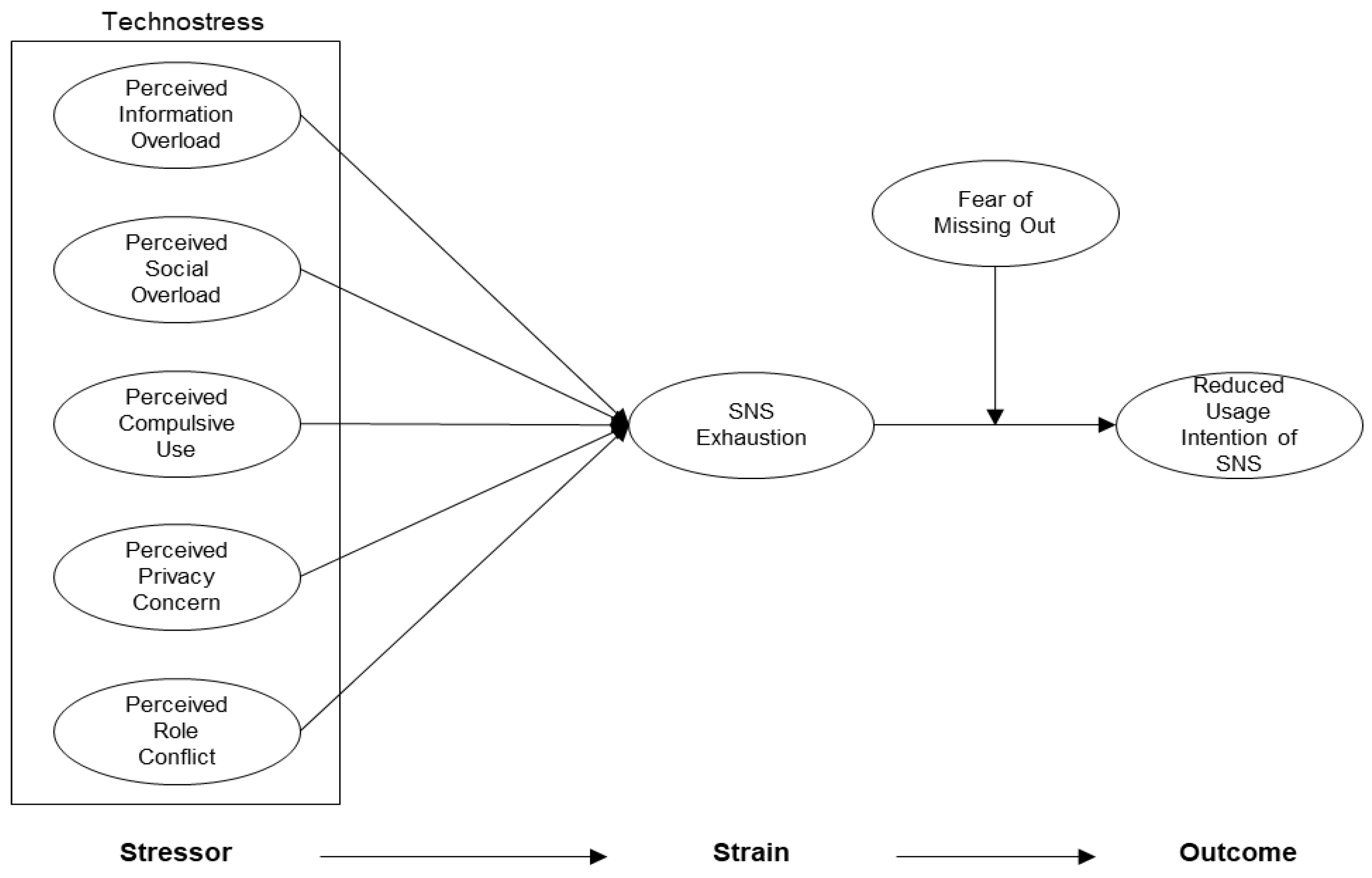

Research Model

In the SNS reduced usage context, and based on the SSO model, we propose the research model shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research Model.

2.3. Cultural Dimension

Cultures affect how people think, act, and reason [61]. Mosca et al. [62] highlighting the critical role of the cultural context within a psycho-social perspective on psychological well-being, and maintains that there is no universal human nature and nor are there universally critical psychological needs. Instead, consistent with a social-constructivist perspective, individuals’ goals, values, and needs are primarily conceived as social constructions or scripts largely shaped by specific social-cultural contexts [63].

Most cross-country information system studies are based on Hofstede’s cultural dimensions. This is a framework for cross-cultural communication developed by Geert Hofstede [64]. National differences can be understood in terms of national cultures, which are holistic examples of the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one human group from another [61]. Even though a given individual within a country may or may not follow the cultural norms of that country, he or she is still influenced by them.

Individualism/collectivism is an important variable for explaining cultural differences at the individual level (as discussed in social psychology research) [65]. At the national level, individualism means that loosely connected social relationships are valued, and individuals are expected to care only for themselves and the members of their immediate social circle (which may be familial). Collectivism means that tightly knit relations are valued, and individuals are expected to look after their extended social relations [66]. Individualism places importance on the welfare and values of the individual person, as opposed to collectivism, which emphasizes the good or desire of the group. For example, individualism is more focused on, more attentive to, and more knowledgeable about the self than about others. Social behavior is driven by attitude, personal values, and cost-benefit analysis, which emphasizes objective rules and principles rather than subjective experiences, processes, and specific contextual information [67]. Collectivist culture tends to provide approval and emotional support so that conversations are likely to revolve around feelings.

China and the United States are recognized as typical representatives of collectivist culture and individualist culture, respectively [64]. The significant differences between the two in terms of values, social structure, and behavioral norms directly affect users’ SNS usage behavior. Chinese culture is deeply influenced by Confucianism and reflects collectivist characteristics. Its core values include filial piety, interpersonal harmony, and “face” (social reputation) [16,18]. Families are closely connected with social networks, and individuals have a strong need to integrate into the collective [16]. This cultural trait manifests in the use of SNS as follows: Users pay more attention to maintaining existing social relationships (such as strengthening their connection with friends and relatives by sharing life updates on Moments), and avoid behaviors that may disrupt interpersonal harmony [59]. Meanwhile, self-disclosure on social media platforms is often oriented towards meeting the expectations of the group and strengthening social bonds, rather than being merely a personal expression.

However, American culture centers on individual freedom, individual achievement, and boundary setting [15,17]. The family structure is relatively loose, and individuals gain independence at an early age after reaching adulthood. Social behavior is geared towards meeting personal needs and demonstrating self-identity [17]. American users of SNS pay more attention to personal entertainment experience, information acquisition efficiency, and self-presentation in line with personal identity [59]. Self-disclosure is more selective, mainly driven by personal preferences rather than catering to group expectations; at the same time, users have higher requirements for the protection of personal privacy and the boundaries of autonomy.

In summary, the differences between individualism and collectivism can influence and determine an individual’s cognition, attitude, emotion, motivation, and social behavior [68]. The psychology and behavior of SNS users are more affected by the influence of numerous contextual lodestars embedded in the broader cultural climate [59]. Therefore, we also need to consider the cultural differences between Chinese and American social network users, on the basis of which we speculate that Chinese and American SNS users will have different responses to the above hypotheses. We therefore collected questionnaires from Chinese and American SNS users, and compared and analyzed the differences in the causes and moderating variables of reduced usage behavior between users from the two countries.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedures

Table 1 shows the specific demographic data for the respondents from China and the United States. Among the Chinese respondents, male respondents accounted for 52.96% and the remaining 47.04% were female. A total of 97.04% of the respondents were generally in the range of 21–40 years old, a proportion higher than the US samples (67.83%). Among the US respondents, males represented 62.72% and females 36.42%. A majority of respondents had at least a bachelor’s degree (76.92% of respondents from China; 63.1% of respondents from the United States). 50.59% of the Chinese respondents are married, as are 50.87% of the US respondents.

Table 1.

Profile of Respondents.

Next, the study gathered statistics on the respondents’ SNS usage. 75.45% of the Chinese respondents and 45.09% of the American respondents indicated that they currently used 3 or more SNS applications (“apps”). In order to reduce the respondents’ response bias, the author induced the respondents to choose only one of the SNS apps to answer the questions.

The selection of SNS platforms in this study was based on three core criteria to ensure the validity and cross-cultural comparability of the research: (1) Market penetration and user representativeness; (2) Alignment with research constructs; (3) Cross-cultural comparability. For Chineses samples, WeChat, Douyin and Sina were selected as they are the most widely used SNS platforms in China. For American samples, Facebook, TikTok, and Instagram were chosen as they are also the top SNS platforms in the U.S. by active users. Also, all selected platforms exhibit the core features of SNS, such as ubiquitous connectivity, social interaction, and information dissemination. That are central to this study’s focus on technostress and FOMO. Meanwhile, the chosen SNS platforms also have functionally comparable such as WeChat and Facebook are both comprehensive social platforms centered on interpersonal connections; Douyin and TikTok are direct counterparts in short-video social services; Sina Weibo and Instagram focus on content dissemination and self-presentation. This functional equivalence allows for valid cross-cultural comparisons of stress perception and FOMO mechanisms.

For Chinese respondents, a majority (50%) chose WeChat as their most commonly used SNS platform, with 39.94% choosing Douyin. Following their choice of SNS app, they reported their main purpose in using this SNS as mainly chatting (70.71%), following others’ lives (65.38%), and getting information (53.25%). Most of them (74.26%) have 100–600 friends in their SNS network and 62.43% of them have used the SNS for more than five years.

A total of 48.84% of American respondents chose Facebook, 24.57% of them chose TikTok, 17.92% of them chose Instagram, and the remaining 8.67% chose other SNS options, such as Reddit, Twitter, LinkedIn and so on. The respondents reported that their main purpose in using their chosen SNS was enjoyment (77.75%), getting information (73.7%), and chatting (47.11%). These responses differ from those of the Chinese respondents, shown in Table 2. Most of the American respondents (54.62%) have 100–600 friends in their chosen SNS, and 21.68% of them have used the SNS more than five years.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics of Respondent’s Characteristics in SNS Usage.

For more descriptive statistics about the SNS usage condition shown as Table 2.

3.2. Measurements

All measurement items were adapted from existing literature and adjusted to the research context. We measured perceived information overload and SNS exhaustion using items from Park [69]. Perceived social overload and reduced usage intention of SNS were measured using items from Zhang et al. [70], and the perceived compulsive use was measured based on Wang and Lee [71]. We drew measures of perceived privacy concern and perceived role conflict from Fan et al. [72]. This study measured fear of missing out using items from Przybylski et al. [73]. Table 3 shows all the measurement items and source of constructs. All constructs were measured using a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Table 3.

Measurement Items.

3.3. Data Analysis

We adopted a structural equation modeling approach. We used confirmatory factor analysis to check the convergent and discriminant validity of the measures through AMOS 25.0. We use three criteria that are normally used to evaluate reliability and validity: (1) In the reliability test, CR and Cronbach’s α are greater than 0.7; (2) in the convergence validity test, all the factor loadings should exceed 0.4 and AVE should exceed 0.5 (however, 0.4 is acceptable: Fornell and Larcker [74] claimed that when CR is higher than 0.6, even if AVE is less than 0.5, the convergent validity of the construct is still adequate); and (3), in the discriminant validity test, the square root of each AVE should be greater than the inter-structure correlation [75].

We checked the convergent validity by using factor loadings, Cronbach’s alpha (α), composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE), as shown in Table 4. Therefore, when we compared the results of our measurement model with the recommended values proposed by Hair et al. [76], we found them acceptable.

Table 4.

Item Loadings and Validities.

We tested the discriminant validity by comparing the correlations against the squared root of the AVE. Table 5 and Table 6 show the results of the US and Chinese samples for the discriminant analysis, demonstrating that the AVE of all constructs is higher than those for all related construct correlations. This suggests that each construct is distinct from others.

Table 5.

Correlation Coefficient Matrix and Roots of the AVE (CN samples).

Table 6.

Correlation Coefficient Matrix and Roots of the AVE (US samples).

Moreover, all the fit indices of the measurement model were acceptable, shown as Table 7.

Table 7.

Fit indices of the measurement model.

4. Results

We adopted structural equation modeling via AMOS 25.0 to test the proposed model and hypotheses. Table 8 also shows that all the fit indices of structural model were acceptable.

Table 8.

Fit indices of the structural model.

4.1. Group Comparison of Hypothesis Testing

In the first step, we examined the structural model by using the two samples. We conducted analyses through AMOS 25.0 to compare the difference between the Chinese samples and the US samples in the structural model and the different moderation effects of psychosocial factors.

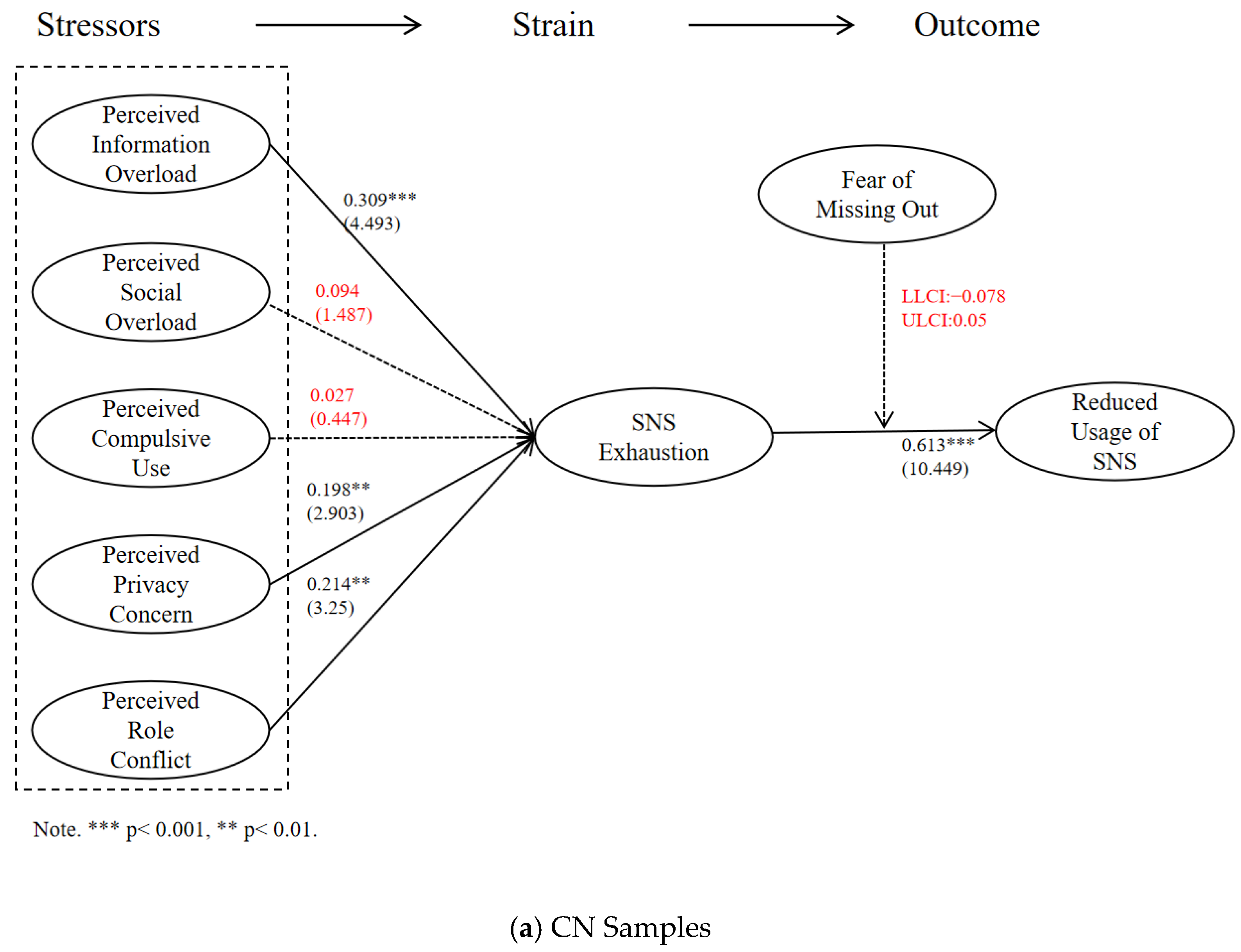

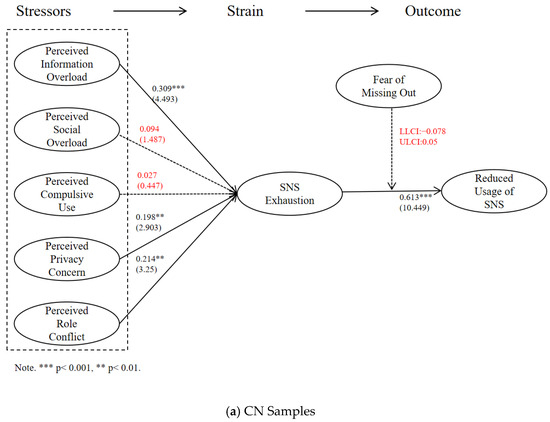

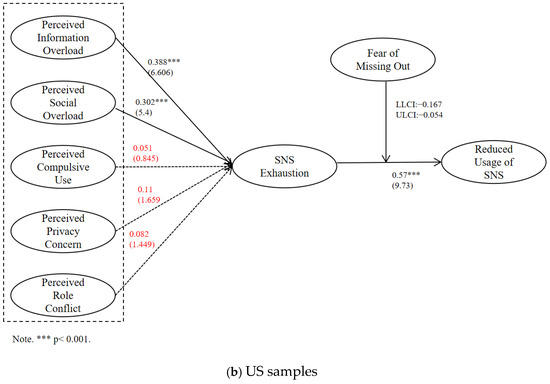

The results of structural model shown as Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Results of the Structural Model Analysis of the CN and US Samples.

Results of Hypotheses Testing

Assessing the results in terms of the paths shown in Figure 2 and Table 9, the Chinese and US respondents showed significant differences in their perception of technostress and the relationship between technostress and SNS exhaustion.

Table 9.

Summary of Hypotheses Testing Results of the CN and US Samples.

In the relationship between perceived information overload and SNS exhaustion (H1), both samples supported the hypothesis. Both Chinese and US respondents experience exhaustion when they perceive information overload arising from their SNS usage. Both samples reject the hypothesized relationship between perceived compulsive use and SNS exhaustion (H3). SNS exhaustion had a significant effect on reduced usage intention (H6) in both samples.

The effect of perceived social overload on SNS exhaustion (H2) was not significant for the Chinese samples, but it was significant for the US samples. Hofstede’s individualism/collectivism cultural dimension can explain this phenomenon. Individualists are more autonomous, independent, self-contained, success-oriented, and deliberate [77]. On the other hand, collectivists value interdependence and consider the interests of the group. Hence, Americans will perceive greater overload when faced with greater social support or social demand than the Chinese, because users possessing a collective cultural background would likely view social demand or support as necessary for establishing and maintaining a group relationship. Therefore, H2 is rejected for the Chinese respondents as they will not be tired by what they consider reasonable behavior.

Moreover, neither perceived privacy (H4) nor perceived role conflict (H5) exerted significant influence on SNS exhaustion for the US samples, but both were significant for the Chinese samples. Culture is an important criterion for self-disclosure decisions [78], but it has not been well examined, meaning that how relationships are different across various cultural dimensions is not well understood. Table 2 reveals that the main purposes of SNS usage for the US respondents were pleasure and information-gathering, whereas Chinese respondents focused on chatting and following their friends’ lives, showing a higher level of self-disclosure on SNS. This also reflects Hofstede’s individualism/collectivism cultural dimension, as the Americans focus on the meeting of personal needs, while the Chinese focus on collective pursuits. Hence, from the cross-cultural and self-disclosure perspective, the reason why H4 is rejected for the US samples appears straightforward.

Some scholars have claimed that differences between different cultures exist with regard to privacy concern and online SNS behavior [59]. Thomson et al. [79] found cross-national differences in online privacy concerns between the US and Japan, with Japanese SNS users more concerned about privacy than American users. Like China, Japan is also representative of a collectivist cultural background. The findings presented by Thomson et al. [79] are consistent with the results of this study. This study focused on problematic SNS usage and consequent psychosocial exhaustion: in contrast to the Americans, the Chinese pay more attention to privacy concerns and experience higher psychosocial stress because of it.

Role conflict can be experienced if one feels incompatibility and dissonance in the different roles one is expected to play on SNS [72]. Scholars in cross-cultural studies argue that individualism is more focused on, more attentive to, and more knowledgeable about the self than about others [80]. Thus, when individualists publish things on SNS, they need only ever meet their own needs, not accord with different role expectations. Therefore, H5 is rejected for the US respondents as they will not be tired by role conflict.

Additionally, analyses of control variables (gender, age, different SNS usage) revealed no statistically significant effects on the structural relationships in the model, which suggests that the hypothesized paths remain robust across demographic and behavioral contexts.

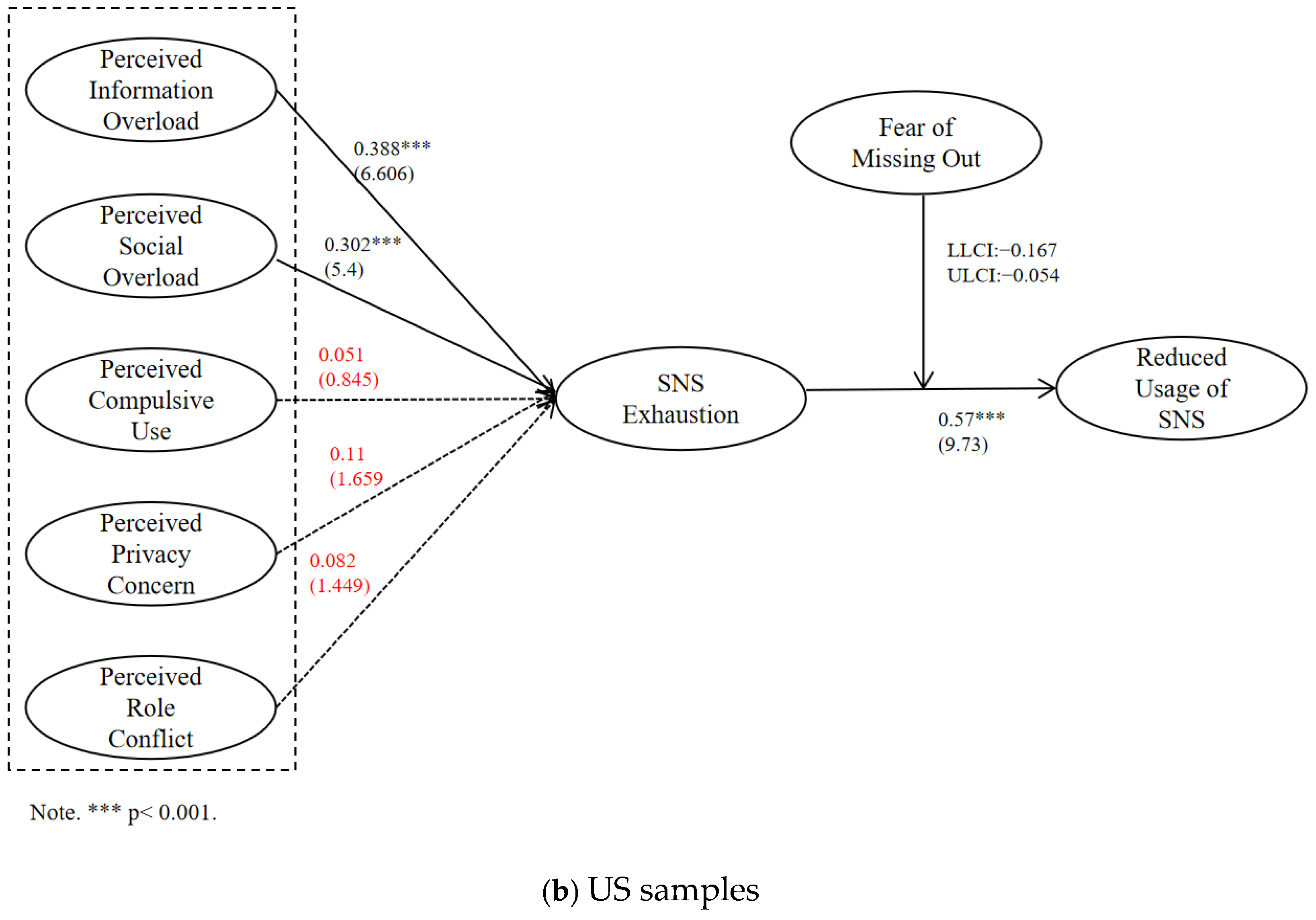

4.2. Group Comparison of Moderation Effect Test of Fear of Missing Out

We considered FOMO, a psychosocial factor, as a moderator in the relationship between SNS exhaustion and reduced usage intention. Given the distinct cultural backgrounds of Chinese and US respondents (collectivism vs. individualism), we adopted an independent moderation testing approach for each group—rather than a comparative multi-group framework—to avoid potential confounding effects of cultural differences on the measurement of moderating paths. This strategy aligns with the study’s core goal of exploring how FOMO operates within each cultural context, without imposing cross-group constraint assumptions that could obscure culture-specific mechanisms. Specifically, we used PROCESS v3.4 (Model 1) to test the moderating effect of FOMO separately for the Chinese and US samples. For each sample, we performed 5000 bootstrap resamples to assess the significance of the interaction term (SE*FOMO). This independent testing allowed us to directly examine whether FOMO exerts a significant moderating role within each cultural context. The results of the independent moderation tests are shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

Results of the Moderating Effects of FoMO between the CN and US Samples.

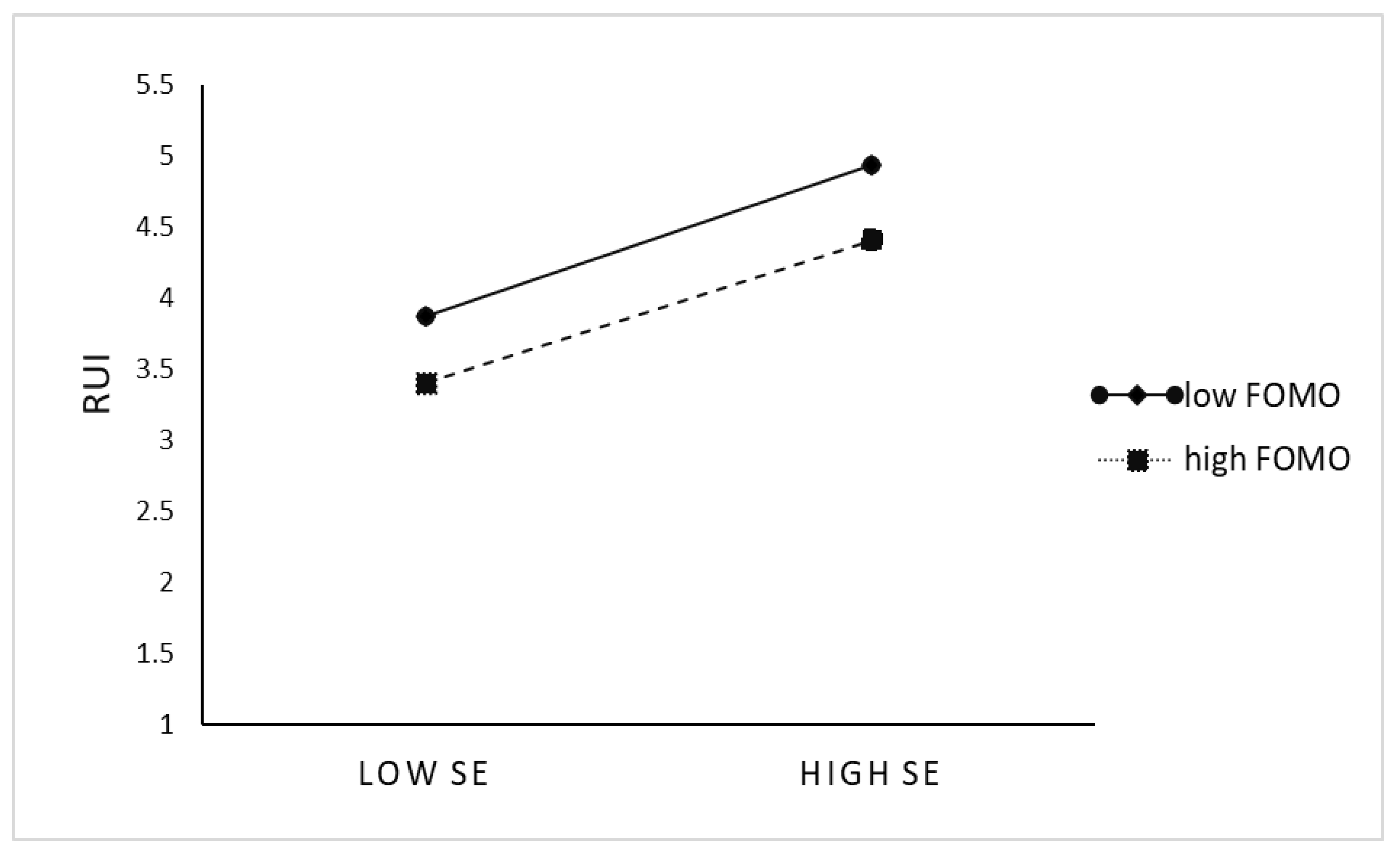

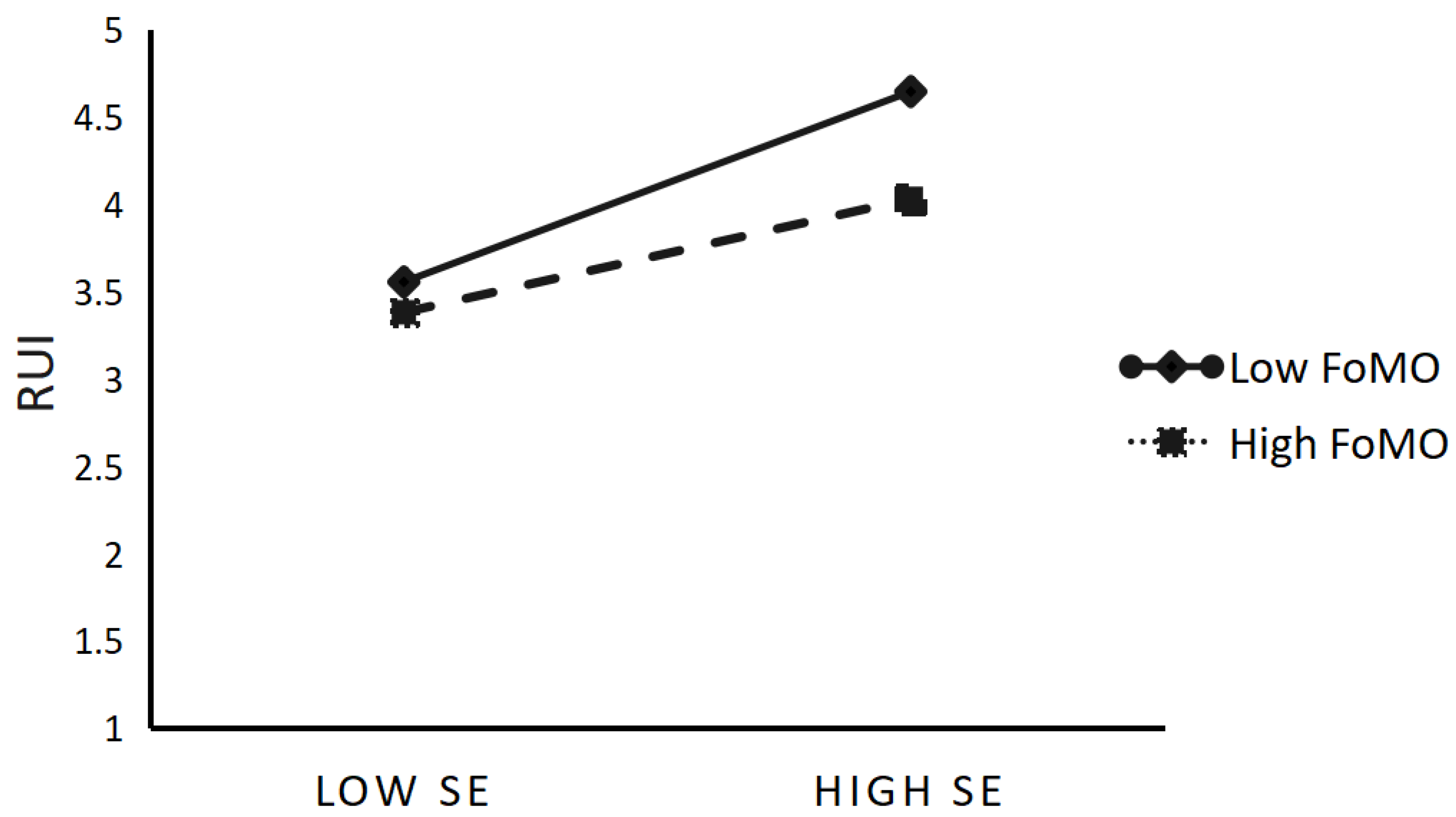

According to Table 10, in the Chinese sample, SE*FOMO has no significant negative impact on RUI (coeff. = −0.014, p > 0.05), Figure 3 also indicating that FOMO does not have a negative moderating effect on the impact of SE on RUI.

Figure 3.

Moderating effect of FOMO in the CN samples.

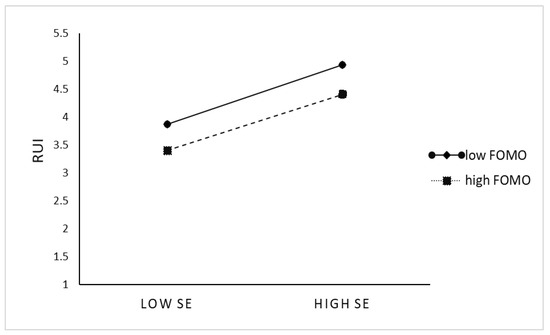

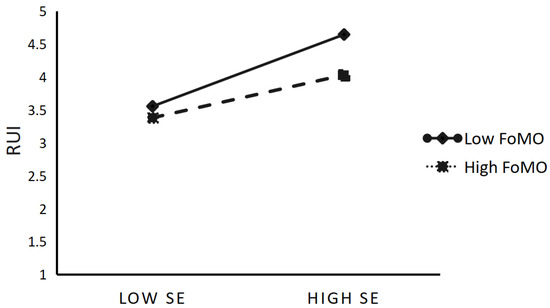

In the US sample, SE*FOMO has a significant negative impact on RUI (coeff. = −0.11, p < 0.05), indicating that FOMO has a negative moderating effect on the impact of SE on RUI. The moderating effect of FOMO in the US samples is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Moderating effect of FOMO in the US samples.

4.2.1. Results of Moderating Effect Test

Group Difference Characteristics of the FOMO Moderating Effect

By comparing the moderating effects of FOMO for US and Chinese respondents, our results indicate that there is a difference between the two samples. Our empirical analysis results show that there are significant group differences in the moderating effect of FOMO between SNS exhaustion and reduced usage intention shown in Table 10. For the group of respondents in the United States, the moderating effect of FOMO reached a statistically significant level (p < 0.05), meaning that in the US sample, respondents with high FOMO levels are significantly more susceptible to the positive impact of SNS exhaustion on the intention to reduce usage. When such respondents experience exhaustion such as energy consumption and information overload brought about by SNS, the anxiety caused by the fear of missing social events will further prompt them to choose to reduce their use of SNS. For US respondents with low FOMO levels, the association strength between SNS exhaustion and the intention to reduce usage was significantly lower.

In sharp contrast, the moderating effect of FOMO in the Chinese respondent group did not reach statistical significance (p > 0.05). Regardless of whether the Chinese samples were divided into high and low groups based on FOMO levels, there was no significant difference in the degree to which SNS exhaustion affected the intention to reduce usage between the two groups. Thus, FOMO did not play a moderating role in strengthening or weakening the above association in the Chinese population.

Explanation of the Underlying Cultural and Sample Characteristics and Differences Seen in the Two Groups

From the perspective of conceptual connotation, FOMO is essentially the anxiety that individuals experience due to the fear of missing out on interesting events in which others are involved, especially those observed through SNS. Its mechanism of action is often closely related to the cultural environment and social behavior logic in which the individual is located. Previous studies have noted that China is a typical representative of a collectivist culture [81], and the Chinese respondents in this study also belong to the group that frequently uses SNS. This dual characteristic provides a key explanatory perspective for explaining the group differences applying to the above-mentioned moderating effect.

Mean comparison analysis (shown in Table 4) reveals that the overall FOMO level of Chinese respondents was significantly higher than that of American respondents. We speculate that the core reason for this is that collectivist culture emphasizes the connection between individuals and groups, and generates a stronger need for a sense of social belonging. Moreover, the frequent use of SNS makes it easier for Chinese respondents to access the social dynamics of others, which in turn generally gives rise to a higher level of fear of missing out. When FOMO becomes a common emotional trait within a group rather than a differentiating variable, its moderating effect on the association of SNS exhaustion with intention to reduce usage is naturally weakened, because regardless of an individual’s FOMO level, they are already at a relatively high anxiety baseline. Therefore, it is difficult to further change the direction and intensity of the impact of exhaustion on the “intention to use” behavior through the differences in FOMO. This result also indirectly confirms the significance of cultural values in shaping FOMO’s mechanism, providing empirical support for the research on SNS user behavior in a cross-cultural context.

Notably, the moderating effect of FOMO in the US sample not only reached statistical significance but also showed an opposite direction to Hypothesis H7. H7 proposed that high-FOMO individuals would be less likely to reduce SNS usage despite exhaustion, assuming that the fear of missing social connections would override the negative impact of exhaustion. However, the US data revealed that high FOMO strengthens the positive relationship between SNS exhaustion and reduced usage intention—this unexpected result is deeply rooted in the individualistic cultural context. Individualistic culture emphasizes personal autonomy and efficiency [64,66], so American users’ FOMO is inherently self-focused rather than relationship-centered. Unlike collectivist users who view FOMO as a signal of social belonging [60], American users’ FOMO aligns with Przybylski et al. [73]’s original conceptualization—anxiety about missing out on personally valuable experiences rather than maintaining group ties. When SNS exhaustion undermines their ability to efficiently obtain these personal values, high-FOMO users perceive a “cost-benefit imbalance”—the exhaustion of maintaining SNS use outweighs the potential gains of avoiding missing out. This prompts them to reduce usage to restore personal efficiency, consistent with the individualistic logic of prioritizing self-interest [28].

5. Discussion

This study examines SNS usage reduction behavior through a cross-cultural comparison between China and the United States. While Hofstede’s cultural dimension theory provides an important macro-level background for understanding cross-national differences, the findings are more precisely interpreted by considering psychological mechanisms shaped by cultural context, rather than attributing the observed differences directly to collectivism or individualism. Based on this cultural difference, we systematically tested the proposed seven hypotheses (H1–H7) and compared the differences in variable relationships and moderating effects between respondents from the two countries.

For respondents in the Chinese context, the results indicate that perceived information overload, privacy concerns, and role conflicts have significant positive effects on SNS exhaustion, which in turn increases the intention to reduce SNS usage. H1, H4, H5 and H6 were fully supported. These relationships can be theoretically understood through the lens of interdependent self-construal. Prior research suggests that individuals in collectivist contexts tend to define themselves in relation to others and place greater emphasis on relational obligations and social evaluation [82]. As a result, stressors that threaten relational harmony or social appropriateness—such as privacy concerns and role conflicts—are more likely to be internalized as psychological strain, thereby intensifying SNS exhaustion and motivating usage reduction.

Notably, perceived social overload and perceived compulsive use do not significantly predict SNS exhaustion among Chinese users. H2 and H3 were rejected. Rather than implying the absence of social demands, this pattern may be explained by norm salience in collectivist cultures. In such contexts, frequent social interaction and responsiveness to others’ requests are often perceived as normative expectations embedded in everyday social life, rather than discretionary burdens. This results also supplemented Wang et al.’s [43] research on compulsive use and reflecting that collectivist users may perceive social demands as a necessary part of group belonging [66], thus mitigating social overload’s stress effect. Consequently, social demands may be less likely to be appraised as stressful, reducing their direct impact on exhaustion. Furthermore, the non-significant moderating effect of FOMO in the Chinese sample suggests that fear of missing out may function as a relatively baseline emotional condition in collectivist settings, where maintaining social contentedness is a central and widely shared concern. When FOMO is prevalent across individuals, differences in its level may be insufficient to meaningfully alter the relationship between exhaustion and usage reduction.

In contrast, the results for U.S. respondents reveal a different pattern. Perceived information overload and perceived social overload both significantly increase SNS exhaustion, which subsequently leads to a stronger intention to reduce SNS usage. H1 and H2 were fully accepted. These findings are consistent with cultural contexts that emphasize personal autonomy and boundary regulation. In individualistic cultures, SNS usage is more closely tied to personal efficiency and self-regulation, making users more sensitive to disruptions that consume cognitive and emotional resources. Social and informational demands are therefore more likely to be perceived as intrusive, resulting in higher exhaustion. However, in the US sample, the three types of technical stressors (perceived compulsive use, privacy concerns, and role conflicts) did not have a direct and significant effect on SNS exhaustion. H3, H4 and H5 were rejected. This aligns with Maier et al. [22] and Lee et al. [28], who noted that individualist users prioritize personal efficiency and autonomy, making overload-related stressors (rather than privacy or role conflict) more salient.

More importantly, FOMO plays a significant moderating role in the U.S. sample, strengthening the relationship between SNS exhaustion and reduced usage intention. This effect can be interpreted as reflecting a tension between the desire to remain socially informed and the need to protect personal resources. For American users with high FOMO, exhaustion may heighten awareness of this conflict, prompting a more decisive reduction in SNS usage as a self-regulatory response. In this sense, FOMO operates not merely as a motivation to remain connected, but also as a factor that amplifies the behavioral consequences of exhaustion in autonomy-oriented contexts.

Taken together, these findings suggest that collectivism–individualism should be understood as a distal cultural backdrop that shapes more proximate psychological mechanisms, such as self-construal, norm salience, and boundary regulation. By focusing on these mechanisms, the present discussion avoids post hoc cultural explanations and offers a theoretically grounded interpretation of why SNS-related stressors, exhaustion, and FOMO operate differently across cultural contexts, while remaining fully consistent with the empirical results.

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

The theoretical value of this study is mainly reflected in its expansion of the research framework for SNS usage behavior, its deepening of the core variable mechanism, and its supplementation of cross-cultural research perspectives. First, using the Stressors-Strain-Outcome (SSO) framework as its core theoretical support, this paper systematically explores the influence mechanism for SNS users’ reduced usage behavior, enriching the current state of the research into SNS reduced usage intention. Most existing studies present only fragmented analyses of the impact of a single factor on reduced usage intention. This study builds an integrated model based on the SSO framework, linking multi-dimensional stressor sources such as information overload and social overload with SNS exhaustion and the intention to reduce usage, clearly presenting a complete logical chain of “the stressor triggers a stress response (exhaustion), and ultimately leads to behavioral results (reduced usage intention)”. It thus provides a more systematic theoretical analysis framework for research in this field.

Second, it innovatively introduced missing out anxiety (FOMO) as a key moderating variable and empirically tested its moderating role in the stressor—stress response pathway, and also reveal the pathway from multiple stressors to SNS exhaustion. This research confirms that users with different levels of FOMO show significant differences in stressor dimensions such as perceived information overload, perceived social overload, perceived compulsive use, perceived privacy concerns, and perceived role conflicts. Users with high FOMO are more sensitive to various social stressors and are more likely to experience exhaustion due to these pressures. However, the perception intensity of users with low FOMO is relatively weak. This discovery overcomes the single perspective of previous FOMO research, further expands and enriches the FOMO research context, and provides a brand-new idea for subsequent exploration of the role of FOMO in the stress transmission mechanism.

Third, it fills the research gap regarding how FOMO regulates the reduced usage intention of SNS by examining it in the cross-cultural contexts of China and the United States. Most existing studies that have focused on FOMO have reviewed its influencing factors and its single effect on mental health. Few studies have placed FOMO in a cross-cultural perspective to explore the differences in the regulatory mechanisms of its behavior with regard to reducing SNS use in different cultures. This study takes China and the United States as cross-cultural research scenarios, comparatively analyzing the causes of the reduced usage intention of SNS by internet users in the two countries and the differences in the moderating effects of FOMO. It not only reveals the cultural boundaries of the role of FOMO, but it also helps to comprehensively explain the cross-cultural commonalities and particularities of the FOMO phenomenon.

Fourth, using the SSO model, we verified the direct correlations among perceived information overload, perceived social overload, perceived compulsive use, perceived privacy concerns, perceived role conflicts, and SNS exhaustion empirically. At the same time, we identified the clear and significant correlation between SNS exhaustion and the intention to reduce use, and explored the intrinsic connection between FOMO and the intention to reduce SNS use in depth. This series of confirmatory studies not only provides new empirical support for the applicability of the SSO model to SNS behavior research, but also further improves the field’s understanding of the theoretical stressors—exhaustion—reduced usage intention path, laying a solid foundation for the subsequent research on the relationship of related variables.

Fifth, it has enriched the research results on FOMO by applying Hofstede’s cultural theories. Most existing studies focus on the correlation between FOMO and mental health indicators such as anxiety, depression, and decreased self-esteem, but few explore the influence of cultural differences on the FOMO mechanism from the perspective of psychological factors and health, and especially not when in combination with the Hofstede cultural dimension. This study found that the moderating effect of FOMO on SNS exhaustion—intention to reduce usage is significantly influenced by the cultural differences between China and the United States. The moderating effect is significant in the individualistic culture (the United States), but not significant in the collectivist culture (China). This result deeply integrates FOMO research with cross-cultural theory, expands the application scenarios of Hofstede’s cultural dimension, and also provides key empirical evidence for understanding how culture shapes the FOMO mechanism.

5.2. Practical Insights

Based on the cross-cultural differences found in this study, we present the following targeted practical suggestions to SNS platform operators, cross-cultural management institutions, and individual users, aiming to solve the problems of exhaustion management and experience optimization in the use of SNS in different cultures.

First are our operational suggestions for SNS platforms. For American users (where FOMO regulation has a significant effect), platforms can develop personalized exhaustion intervention tools. For example, when the system detects that a user shows signs of exhaustion (such as a sudden decrease in usage time or a drop in interaction frequency), it can push lightweight social content (such as summaries of key friends’ updates, rather than full information) based on the user’s FOMO level. This will not only alleviate the exhaustion caused by information overload but also reduce the anxiety triggered by FOMO, preventing users from completely reducing their usage due to “exhaustion + high FOMO”. For Chinese users (who generally have a high level of FOMO coupled with weak regulatory effects), platforms need to focus on optimizing the balance between providing a sense of social belonging and alleviating exhaustion. For instance, they could launch group light-interaction functions (such as low-frequency check-in in interest communities and multiplayer collaborative mini-games), which not only meet the users’ demands for social connection in a collectivist culture, reduce FOMO caused by fear of missing group activities, and lower information overload and energy consumption through low-intensity interaction, alleviating exhaustion from the source and avoiding the vicious cycle of “high FOMO + high exhaustion”.

Second, we offer the following suggestions for cross-cultural management and digital health institutions. Cross-cultural enterprises or educational institutions (such as employees of multinational companies and international student groups), when conducting SNS usage management and mental health intervention, must fully consider cultural differences. For Americans, a combined intervention of “FOMO level assessment + exhaustion warning” can be adopted, while anxiety management courses (teaching such lessons as how to rationally view social dynamics and reduce missing-out concerns) can be provided for users with high FOMO, showing them how to set reasonable SNS usage boundaries. For the Chinese community, the focus of intervention should be on a dual approach for reducing the prevalence of FOMO and alleviating exhaustion. This could be achieved, for instance, through collective mindfulness training to help users reduce their excessive reliance on group social interaction. At the same time, collaborate with platforms to optimize information push algorithms to minimize the extent to which redundant information interferes with users and user experiences. Doing so will reduce the risk of exhaustion from both environmental and psychological perspectives.

Third, we offer practical guidance for individual users. American users (with high FOMO, which can intensify the effect of exhaustion) can reduce the combination of FOMO and exhaustion by actively filtering social information by, for instance, regularly clearing their SNS follow lists and only keeping their core social contacts. This would enable them to avoid simultaneously triggering FOMO (fear of missing important information) and exhaustion (information overload) due to a vast number of irrelevant updates. Chinese users (who generally possess high FOMO) can balance their social needs and self-regulation by setting “no social” time periods, such as a fixed period of 1–2 h of offline time each day to focus on real social interactions or personal affairs, gradually reducing their SNS-based missing-out anxiety and at the same time reducing the fatigue caused by continuous use. This will allow them to realize a healthier digital lifestyle.

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

This study adopts a quantitative research method to explore FOMO’s moderating effect on the reduced usage intention of SNS when examined in the culturally different contexts of China and the United States. Although the results achieved are important, this study also faces certain limitations. First, there are limitations to the sample representativeness and the data collected. The sample only covered the United States and China, and the respondents were mainly young people, with middle-aged and elderly people, people from different occupations, and other groups underrepresented. The cultural representativeness and demographic diversity of the sample may have been insufficient—for example, the American sample may not fully represent all groups found in its individualistic culture, and the Chinese sample does not address the differences between rural and urban areas. This may reduce the generalizability of the research conclusions. In addition, our data collection process adopts the cross-sectional survey method, which can only capture the variable relationship at a certain point in time and cannot reveal dynamic changes in FOMO, exhaustion, and usage intention.

Second, there are limitations in the measurement and control of variables. In terms of variable measurement, the operational definition of SNS exhaustion adopted in this study is mainly based on factors such as information overload and energy consumption [28], but does not distinguish between different types of SNS. For example, users’ exhaustion on (and with) short-video platforms may stem primarily from passive consumption caused by algorithmic push notifications, while on social networking platforms, it may result from the pressure to actively maintain social relationships. This difference may affect the moderating effect of FOMO, but this study did not consider such detailed or granular distinctions. Furthermore, although the study controlled for demographic variables such as usage frequency, it did not include potential interfering variables such as cultural identity intensity (such as the cultural identity of immigrant groups in the United States, or the extent of cultural adaptation found in Chinese overseas students), which might affect the accuracy of cross-cultural comparison results.

Third, the depth to which we explore theoretical mechanisms is limited. Although this study identified cultural differences in the moderating effect of FOMO and explained these in combination with individualism–collectivism, it did not delve deeply into the intermediate mechanism to explain why high FOMO cannot moderate exhaustion and usage intention in collectivist cultures, or identify whether there are other variables (such as social norm pressure). Is the mediating effect of Chinese users’ reluctance to reduce usage even when they are tired a result of a fear of being out of the group, thereby masking the moderating role of FOMO? This issue remains unanswered, resulting in this study’s explanations of cultural differences remaining at the level of initial engagement, rather than demonstrating a profound understanding of the deeper psychological mechanisms at play, and thereby offering an enticing prospect for future researchers wishing to investigate these issues more thoroughly.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.-M.W., N.J. and K.L.; methodology, K.L. and H.X.; software, H.-M.W.; validation, H.-M.W., N.J. and K.L.; formal analysis, N.J.; investigation, H.-M.W.; resources, H.-M.W. and K.L.; data curation, H.-M.W.; writing—original draft preparation, H.-M.W.; writing—review and editing, H.-M.W., H.X. and K.L.; visualization, H.X. and K.L.; supervision, K.L.; project administration, H.-M.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partially funded by the Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project of Zhejiang Province in China (25SSHZ035YB), the Scientific Research Fund of Zhejiang Provincial Education Department (Y202559116) and the Chinese Ministry of Education University-Industry Collaborative Education Program (2410300149).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Ningbo University of Finance and Economics (protocol code NBUFE-2025-1201 and date of approval 15 September 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alsharif, S.; Shafie, H.; Al-Qahtani, S.; Al-Qannas, L.; Abdullah, M.; Al-Shammari, H. Saudi Women’s Social Fragility in Friendship Relationships and Its Social and Cultural Effects in Urban Areas: An Analytical Social Study. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2025, 11, 2492393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Lu, Z.; Kuang, H.; Wang, C. Information Avoidance Behavior on Social Network Sites: Information Irrelevance, Overload, and the Moderating Role of Time Pressure. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 52, 102067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Mao, Z.; Gu, X. The Relationships between Social Support Seeking, Social Media Use, and Psychological Resilience among College Students. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2025, 18, 563–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koeske, G.F.; Koeske, R.D. A Preliminary Test of a Stress-Strain-Outcome Model for Reconceptualizing the Burnout Phenomenon. J. Soc. Serv. Res. 1993, 17, 107–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jung, S.H.; Choi, H.J. Antecedents Influencing SNS Addiction and Exhaustion (Fatigue Syndrome): Focusing on Six Countries. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2023, 42, 2601–2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.M.; Liu, J.Y.; Chen, J.W. The Double-Edged Sword Effect of Performance Pressure on Employee Boundary-Spanning Behavior. J. Chin. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2024, 15, 86–103. [Google Scholar]

- Fioravanti, G.; Casale, S.; Benucci, S.B.; Prostamo, A.; Falone, A.; Ricca, V.; Rotella, F. Fear of Missing Out and Social Networking Sites Use and Abuse: A Meta-Analysis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 122, 106839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, I.; Cui, H.; Son, J. Conformity Consumption Behavior and FoMO. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frampton, J.R.; Fox, J. Social Media’s Role in Romantic Partners’ Retroactive Jealousy: Social Comparison, Uncertainty, and Information Seeking. Soc. Media Soc. 2018, 4, 2056305118800317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Wang, Y.; Wang, W. Does Cyberchondria Influence Subjective Well-Being in Online Healthcare Platforms?—An Empirical Study. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2025, 18, 1825–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Zhang, B. Differential Effects of Active Social Media Use on General Trait and Online-Specific State-FoMO: Moderating Effects of Passive Social Media Use. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 1391–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Tian, Y. The Impact of Problematic Social Media Use on Inhibitory Control and the Role of Fear of Missing Out: Evidence from Event-Related Potentials. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2024, 17, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Q.; Nam, B.H.; English, A.S. Acculturation and Linguistic Ideology in the Context of Global Student Mobility: A Cross-Cultural Ethnography of Anglophone International Students in China. Educ. Rev. 2024, 76, 1620–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H. The Pursuit of Individual Value and Free Expression: A Comparative Study of the Eastern and Western Renaissance and Its Impact on Modern Society. J. Educ. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2023, 21, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoliarchuk, O.; Yang, Q.; Diedkov, M.; Serhieienkova, O.; Ishchuk, A.; Kokhanova, O.; Patlaichuk, O. Self-Realization as a Driver of Sustainable Social Development: Balancing Individual Goals and Collective Values. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 13, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. Global Transmission of Chinese Culture from the Perspective of Cross-Cultural Communication. Philos. Soc. Sci. 2024, 1, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Din, J. The impact of Confucianism on ancient Chinese society and governance. Int. J. Foreign Trade Int. Bus 2024, 6, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Hu, H. Discursive Strategies of Chinese Elders in Intergenerational Conflicts: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Mediation Television Programs in China. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0320909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandon, A.; Dhir, A.; Almugren, I.; AlNemer, G.N.; Mäntymäki, M. Fear of Missing Out (FoMO) among Social Media Users: A Systematic Literature Review, Synthesis and Framework for Future Research. Internet Res. 2021, 31, 782–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flecha Ortiz, J.A.; Santos Corrada, M.; Perez, S.; Dones, V.; Rodriguez, L.H. Exploring the Influence of Uncontrolled Social Media Use, Fear of Missing Out, Fear of Better Options, and Fear of Doing Anything on Consumer Purchase Intent. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2024, 48, e12990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Shi, C.; Cao, X. Understanding the Effect of Social Media Overload on Academic Performance: A Stressor-Strain-Outcome Perspective. In Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 8–11 January 2019; pp. 2657–2666. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, C.; Laumer, S.; Weinert, C.; Weitzel, T. The Effects of Technostress and Switching Stress on Discontinued Use of Social Networking Services: A Study of Facebook Use. Inf. Syst. J. 2015, 25, 275–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaluddin, H.; Ahmad, Z.; Wei, L.T. Exploring Cyberloafing as a Coping Mechanism in Relation to Job-Related Strain and Outcomes: A Study Using the Mediational Model of Stress. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2023, 9, 2278209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovsiannikova, Y.; Pokhilko, D.; Kerdyvar, V.; Krasnokutsky, M.; Kosolapov, O. Peculiarities of the Impact of Stress on Physical and Psychological Health. Multidiscip. Sci. J. 2024, 6, 2024ss0711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, N.B.; Hoang, D.; Do, H.N.; Martinez, L.F. Managing Trust and Fatigue in Social Media Consumption: A Strategic Perspective on Discontinuance Intention. J. Mark. Anal. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.M.; Zhu, Y.P.; Lee, K.T. What Signals Are You Sending? How Signal Consistency Influences Consumer Purchase Behavior in Live Streaming Commerce. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Xu, C.; Ali, A. A Socio-Technical System Perspective to Exploring the Negative Effects of Social Media on Work Performance. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 2024, 76, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.R.; Son, S.M.; Kim, K.K. Information and Communication Technology Overload and Social Networking Service Fatigue: A Stress Perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 55, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, J.; Turel, O.; Oliveira, T. Explaining Social Media Use Reduction as an Adaptive Coping Mechanism: The Roles of Privacy Literacy, Social Media Addiction and Exhaustion. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2024, 42, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondo, M.; Pileri, J.; Barbieri, B.; Bellini, D.; De Simone, S. The Role of Techno-Stress and Psychological Detachment in the Relationship between Workload and Well-Being in a Sample of Italian Smart Workers: A Moderated Mediated Model. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlici, I.A.; Maftei, A.; Opariuc-Dan, C. This Is Too Much! Social Media Integration and Adults’ Psychological Distress: The Mediating Role of Cyber and Place-Based Information Overload. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2025, 44, 2445–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azri, M.D.N.; Malek, S.N.N.A.; Besar, T.B.H.T. An Overview of Information Overload, System Feature Overload, Social Overload and Communication Overload. Environ.-Behav. Proc. J. 2024, 9, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, H.; Wang, Y. Deciphering Dynamic Effects of Mobile App Addiction, Privacy Concern and Cognitive Overload on Subjective Well-Being and Academic Expectancy: The Pivotal Function of Perceived Technostress. Technol. Soc. 2025, 81, 102861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, A.; Laato, S.; Islam, N.; Dhir, A. Social Comparisons at Social Networking Sites: How Social Media-Induced Fear of Missing Out and Envy Drive Compulsive Use. Internet Res. 2025, 35, 691–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, T.; Warraich, N.F.; Arshad, A. Assessing the Relationship between Information Overload, Role Stress, and Teachers’ Job Performance: Exploring the Moderating Effect of Self-Efficacy. Inf. Dev. 2024, 02666669241232422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ahmad, W. Online Impulse Purchase in Social Commerce: Roles of Social Capital and Information Overload. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 4412–4429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wu, Q.; Li, D.; Tian, X. An Exploration of the Influencing Factors of Privacy Fatigue among Mobile Social Media Users from the Configuration Perspective. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang-Van, T.; Nguyen, P.T.; Vu, T.T.; Doan, M.Q. How Does Social Overload Lead to Withdrawal Behavior? The Case of Social Communities on Social Networking Sites. Inf. Technol. People 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, F.; Liu, J.; Alvi, A.; Luqman, A.; Shahzad, F.; Sajjad, A. Unpacking the Relationship between Technological Conflicts, Dissatisfaction, and Social Media Discontinuance Intention: An Integrated Theoretical Perspective. Acta Psychol. 2023, 238, 103965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Cai, M. Social Support and Reference Group: The Dual Action Mechanism of the Social Network on Subjective Poverty. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, N.; Yang, C.; Han, L.; Jou, M. Too Much Overload and Concerns: Antecedents of Social Media Fatigue and the Mediating Role of Emotional Exhaustion. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 139, 107500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, T.; Guo, Y.; Chen, H. Understanding the Privacy Protection Disengagement Behaviour of Contactless Digital Service Users: The Roles of Privacy Fatigue and Privacy Literacy. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2024, 43, 2007–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liang, M.; Lc, R.; Luo, Y. StayFocused: Examining the Effects of Reflective Prompts and Chatbot Support on Compulsive Smartphone Use. In Proceedings of the 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 11–16 May 2024; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Vaghefi, I. Want to Disconnect? Understanding the Dual Effects of Compulsive Social Media Use on Temporary Discontinuance Behavior. Inf. Technol. People 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Kwok, R.C.W.; Lowry, P.B.; Liu, Z.; Wu, J. The Influence of Role Stress on Self-Disclosure on Social Networking Sites: A Conservation of Resources Perspective. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 103147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.W.; Jhou, Y.T. Understanding Self-Disclosure in Social Networking Sites: The Influence of Trust and Perceived Privacy Risk. J. Appl. Financ. Bank. 2025, 15, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salo, M.; Pirkkalainen, H.; Chua, C.E.H.; Koskelainen, T. Formation and Mitigation of Technostress in the Personal Use of IT. MIS Q. 2022, 46, 1073–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, H.; Li, C.; Lu, X. Disentangling User Fatigue in WeChat Use: The Configurational Interplay of Fear of Missing Out and Overload. Internet Res. 2024, 34, 160–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhao, J.; Tong, L.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y. Too Much Social Media? Unveiling the Effects of Determinants in Social Media Fatigue. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1277846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piao, X.; Kim, S.; Shin, Y.; Lee, C.; Yue, J. The Effect of Social Anxiety on SNS Addiction among College Students in Northeast China: The Mediating Role of Depressive Symptoms. Acta Psychol. 2025, 259, 105397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Tian, H.; Hou, Y.; Zhu, M.; Gao, X. Social Networking Sites Use Exacerbates Appearance Anxiety in Young Chinese Women: The Moderating Role of Self-Concept Clarity. Psychol. Pop. Media 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, S.; Su, C. System Complexity, Information & Communication Overload, Work-Family Balance & Social Networking Sites’ Tiredness: A Social and Digital Perspective. Prof. Inf. 2024, 33, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kolas, J.; von Mühlenen, A. Checking in to Check Out? The Effect of Boredom on Craving, Behavioural Inhibition and Social Networking Site Use. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2024, 23, 4265–4284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, S.; Hudson, C.C.; Harkness, K. Social Media and Depression Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis. Res. Child Adolesc. Psychopathol. 2021, 49, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osatuyi, B.; Turel, O. Conceptualisation and Validation of System Use Reduction as a Self-Regulatory IS Use Behaviour. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 29, 44–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, A.; Feng, Y.; Rasheed, M.I.; Ali, A.; Gong, M. Smartphone-Based Social Networking Sites and Intention to Quit: Self-Regulatory Perspective. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2021, 40, 1055–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.; Yao, L.; Tian, Y.; Sun, X.; Zhou, Z. Information Overload and the Intention to Reduce SNS Usage: The Mediating Roles of Negative Social Comparison and Fatigue. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 5212–5219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, M.; Zhang, H. FOMO: A Fragment-Based Objective Molecule Optimization Framework. Res. Sq. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Niu, Z.; Mei, S.; Griffiths, M.D. A Network Analysis Approach to the Relationship between Fear of Missing Out (FoMO), Smartphone Addiction, and Social Networking Site Use among a Sample of Chinese University Students. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2022, 128, 107086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Wang, P.; Nie, J.; Guo, J.; Feng, J.; Lei, L. Social Networking Sites Addiction and FoMO: The Mediating Role of Envy and the Moderating Role of Need to Belong. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 3879–3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, I.; Ali, H.; Us, K.A. Factors Affecting Critical and Holistic Thinking in Islamic Education in Indonesia: Self-Concept, System, Tradition, Culture. (Literature Review of Islamic Education Management). Dinasti Int. J. Manag. Sci. 2022, 3, 407–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosca, O.; Milani, A.; Fornara, F.; Manunza, A.; Krys, K.; Maricchiolo, F. Basic Psychological Needs, Good Societal Development and Satisfaction with Life: The Mediating Role of the Environment. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tri, N.M. Culture as a Dynamic Product of Socially and Historically Situated Discourse Communities: A Review of Literature. VMOST J. Soc. Sci. Hum. 2024, 66, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.C.; Unal, A.F. Individualism-Collectivism: A Review of Conceptualization and Measurement. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Business and Management; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bienek, N.B.; Gross, C.; Lackes, R.; Siepermann, M. Toward an Understanding of Individualism, Collectivism and Technostress on Social Network Sites: Evidence from China and Germany. Int. J. Mob. Commun. 2024, 23, 324–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.Y.; Wang, Y.T.; Huang, T.K. Exploring the Antecedents of Mobile Payment Service Usage: Perspectives Based on Cost–Benefit Theory, Perceived Value, and Social Influences. Online Inf. Rev. 2020, 44, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Du, J.; Yang, K.; Ge, Y.; Ma, Y.; Mao, H.; Wu, D. Relationship between Horizontal Collectivism and Social Network Influence among College Students: Mediating Effect of Self-Monitoring and Moderating Effect of Self-Efficacy. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1424223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, N. The Moderating Influence of SNS Users’ Attachment Style on the Associations between Perceived Information Overload, SNS Fatigue, and Mental Health. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2024, 43, 3510–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]