Abstract

With worsening energy and environmental issues, new energy vehicles (NEVs) have emerged as the future of the automotive industry, as they aim to address the high energy consumption and carbon emissions of traditional fuel vehicles. However, due to the industry’s short development history, limited available data, and incomplete supporting systems, most existing NEV research focuses on theoretical analysis, which hinders the achievement of accurate sales predictions. Today, online reviews influence consumer decisions and thus provide a new perspective for sales forecasting. Based on consumer behavior theory and neural network principles, our research selects factors influencing NEV sales (covering economics, technological, policy, and consumer dimensions, including preprocessed crawled online reviews), constructs an index system screened via grey relational analysis, and establishes five models (SARIMA, GRU, Seq2Seq, Attention-GRU, Attention-Seq2Seq) for training and testing. The study supports the use of online reviews in NEV sales prediction and proves that the model based on cutting-edge technology of Attention-Seq2Seq can outperform the other four methods presented above. Through this, the current contributions advance marketing innovation by helping NEV stakeholders understand relevant information using a predictive model from online reviews, which leads to precise product improvement and optimal distribution of resources as well as precise adoption of marketing strategies.

1. Introduction

With the global emphasis on environmental protection and sustainable development, the high pollution and energy consumption of traditional fuel vehicles have become increasingly prominent [1]. Governments worldwide are promoting the popularization of NEVs through regulatory measures and incentive policies, for instance, the EU’s 2035 ban on fossil fuel vehicles [2] and China’s nationwide NEV promotion scheme (such as vehicle purchase subsidies [3], tax incentives [4], and the construction of charging infrastructure [5]) have accelerated market growth. Combined with global energy structure adjustment and market demand for intelligent vehicles, the NEV industry has ushered in development opportunities. In recent years, the NEV industry has grown significantly, with steady global sales growth. According to EVTank data, NEV sales in the U.S. and Europe reached 2.948 million and 1.468 million units, respectively, in 2023, representing year-on-year growth of 18.3% and 48.0% [6]. Global sales hit 18.236 million units in 2024 (+24.4% year-on-year), with China’s market share rising from 64.8% to 70.5% in 2023 [7]. China’s NEV production and sales in 2024 reached 12.888 million and 12.866 million units, increasing by 34.4% and 35.5% year-on-year, respectively, and ranking first globally for 10 consecutive years [8].

Despite a rise in NEV purchases, obstacles remain which inhibit further adoption: battery range apprehensions, weak coverage of charging stations, and high prices—these considerations all affect whether a consumer decides to buy an NEV or not [9]. This necessitates proper sales projections to guide industry supply chain development, sort through resources, and provide data for decision-making. Due to the recently established NEV market and its rapidly changing environment, existing prediction models still fall short.

Before statistical methods gained widespread adoption, sales forecasting merely relied on enterprise managers’ experiential judgment, lacking a systematic analytical framework [10]. With the data resources expanded, prediction deviations could lead to substantial financial losses and missed business opportunities, prompting more and more enterprises to adopt traditional time series forecasting models to improve prediction accuracy [11]. Although these time series forecasting models have demonstrated excellent performance in sales forecasting, they fail to capture nonlinear relationships. Consequently, researchers turned to machine learning-based prediction models, which, despite their capability to handle nonlinear relationships, suffer from degraded prediction performance when faced with high sample noise [12]. In recent years, deep learning has transformed sales forecasting by addressing the temporal and nonlinear challenges that plagued earlier methods [13,14,15,16]. However, most deep learning models tend to treat all input features as equally important, failing to dynamically prioritize critical factors that exert outsized influences on NEV sales.

With emerging technologies reshaping marketing paradigms, the integration of unstructured consumer-generated content into cutting-edge neural network architectures offers an innovative avenue for marketing development in the NEV industry. To address the limitations of existing research on new energy vehicle (NEV) sales forecasting, this study sets four core objectives. (1) Integrating unstructured online reviews into traditional structured indicators; (2) constructing a more reasonable combined prediction index system from multiple perspectives; (3) establishing a better fit sales prediction model for NEVs, applying an attention mechanism to embedding layer; and (4) verifying the great merits brought by fusion of multi-source data as well as advanced model architecture through a series of comparative experiments. The work thus provides a replicable approach for sales forecasting for emergent industries.

Contributions from our study include (1) introducing online unstructured review data to combine with the traditional structured data used for sales forecasting in NEV, thereby broadening the scope of utilization of multi-source data fusion in the NEV field; (2) adopting the combination model of the attention mechanism and Seq2Seq structure to improve the accuracy and interpretability of forecast models, providing empirical evidence for the benefit of combining the two structures in NEV sales predictions; (3) offering suggestions for government policies on policy adjustments, companies’ production scheduling, and industrial resource allocation in order to promote the sustainable and high-quality development of the NEV industry.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Evolution of Vehicle Sales Forecasting Methods

Vehicle sales forecasting moves through three major stages from traditional statistics to machine learning and finally to a deep learning approach. Every step forward is built on addressing problems with the old phase as well as taking advantage of their progress.

Traditional statistical models laid the foundation for sales prediction with a focus on linear relationships and time-based patterns. Early regression-based studies [17,18] established correlations between macroeconomic indicators (e.g., household income, employment rate) and vehicle demand but failed to capture nonlinear market dynamics. In terms of time series prediction research on China’s automobile sales, the ARIMA model is widely used to capture the temporal patterns of sales volume. For instance, Guo utilized monthly sales data to construct an ARIMA model for predicting China’s total automobile sales in 2013 [19]; Chen et al. further optimized the parameters and established the ARIMA (7,2,1) model to predict the sales volume of the ORA brand in early 2021 [20]. Meanwhile, multiple regression methods are introduced to integrate external variables such as economy and environment. For instance, Zhang constructed the ARIMA and regression models based on economic and environmental factors to explore the influencing factors of private car ownership [21]; Zhang et al. introduced multiple variables such as the proportion of new vehicles, gasoline production, electricity consumption, and unemployment rate, to conduct regression analysis and predict the sales volume of new energy vehicles in 2018 [22]. ProfARIMA introduces profit-driven parameter optimization [23]. These models are characterized by strong parameter interpretability and low computational cost. However, they require time series data to be stationary, fail to capture nonlinear relationships, and have high demands on data quality.

Machine learning models emerged to address nonlinearity challenges. Hybrid models such as adaptive network-based fuzzy inference systems [24] and particle swarm-optimized grey Bernoulli models [25] have demonstrated superior performance over single statistical models by integrating multiple algorithmic strengths. Support vector regression (SVR) [26] and random forests [14] effectively handle high-dimensional data and noise but suffer from poor interpretability and overfitting risks in dynamic markets. For NEV-specific forecasting, Wang combined BP neural network with ARIMA and principal component analysis to predict monthly and annual sales, respectively [27]. Ouyang et al. found through comparative experiments that the prediction accuracy of LSTM neural networks is superior to that of other models such as multi-layer perceptrons and support vector machines [28]. Liu et al. utilized convolutional neural networks to process online search volume and sales data and found that its prediction effect is superior to that of RBF, ARIMA, and their hybrid models [29]. Furthermore, the combined models have further enhanced the predictive performance. For instance, Zhou et al. introduced grey relational analysis to screen out influencing factors and constructed a grey neural network optimized by the fruit fly algorithm (FOA-GNN) to predict the monthly sales of NEV in 2019 [30]. However, machine learning models suffer from long training time, poor interpretability, high risk of overfitting, and sensitivity to noise.

Deep learning has revolutionized forecasting by capturing long-term dependencies and complex feature interactions. LSTM and GRU networks [31] have outperformed traditional models in handling sequential sales data, with the Prophet-LSTM hybrid [32] achieving enhanced adaptability to seasonal fluctuations. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [15] excel at extracting local patterns from multi-source data, while attention-augmented models [33] improve feature prioritization. The Hybrid LSTM-GBRT model introduced in reference [34] incorporates long-term dependency modeling of LSTM and robust nonlinear mapping of GBRT but disregards unstructured data (e.g., user reviews) so as to narrow down the data dimensions. Chandriah et al. [13] adopted modified Adam optimizer for LSTM to improve automotive demand forecast, pointing out that there is still room for enhancing the algorithm in practice. Although a few DL models for NEVs applied structured data only or treated all input features equally, most works did not adequately integrate the nuances of some important real-time input features such as user intent/demand and external conditions into their models.

2.2. Sales Forecasting Based on Text Mining

Feldman et al. were pioneers in text mining unstructured data [35] and advocated for mining structured information through online textual content. It seeks to obtain useful structured information about semantics using deep learning and other algorithms that are capable of understanding text content and deriving implicit meaning from potential concepts and implied associations between them [36]. However, early text mining algorithms can only attain only basic semantic understanding and do not grasp contextual or emotive cues present within a text.

With advances in artificial intelligence and deep learning techniques, text mining develops rapidly, and broad applications emerge across different disciplines. In terms of the influence on consumer decisions, multiple studies have revealed the direct promoting effect of online reviews on sales performance. For instance, Chevalier et al. demonstrated that book reviews on Amazon have significantly increased sales [37]. Duan et al. also found that online reviews played a key role in driving box office revenues of films [38]. Despite these findings, these early studies primarily focus on the quantitative impact of reviews (e.g., volume) rather than qualitative attributes (e.g., sentiment intensity or topic relevance). Meanwhile, researchers are dedicated to developing more efficient methods for review mining and representation to enhance information usability. Hong et al. proposed a review analysis framework that integrates grammar rules and the LDA model, which can identify product attributes and their evaluation phrases and automatically generate concise summaries with the help of deep neural networks, thereby providing users with intuitive product insights [39]. However, this framework relies on pre-specified grammar rules, reducing its adaptability to informal or dynamically evolving online review language. In terms of personalized services, comment mining also provides a new path for the optimization of recommendation systems. Hao et al. constructed a product recommendation model based on feature-opinion pairs, verified the feasibility and effectiveness of using comment data to assist users in decision-making, and further expanded the application prospects of comment data in intelligent recommendation [40]. However, the model’s performance declines when faced with sparse review data—a prevalent issue in emerging NEV market segments with limited user feedback.

As text mining research has advanced, scholars have recognized that emotional information in online reviews reflects consumers’ psychological expectations, making sentiment analysis a key direction. At the polarity analysis level, Lee et al. found review sentiment polarity influences new product acceptance [41] but overlooked product maturity’s moderating role—critical for evolving NEVs. Berezina et al. identified differing focuses of satisfied and dissatisfied hotel customers [42], yet this is less applicable to automotive reviews, which blend technical, service, and cost factors. Methodologically, Huang et al. combined word2vec with sentiment similarity to enhance accuracy [43], but high computational complexity hinders scalability for large NEV review datasets. Sun’s user segmentation [44] assumes stable consumer preferences, conflicting with NEVs’ rapid tech/policy-driven changes. Liu et al.’s MPCM model [45] improves cross-group emotion recognition but relies on multi modal data that remains incomplete in NEV platforms, restricting practical use.

Beyond building user profiles and analyzing consumer demands, online reviews are extensively employed in product sales forecasting, especially in the automotive industry with representative frameworks. Fan et al. integrated review sentiment scores with the Bass/Norton model to improve accuracy [46], but the model’s stable diffusion assumption is incompatible with NEVs’ policy/tech-driven volatility. Jiang et al.’s Attention-LSTM combined word-of-mouth and search data [33], yet failed to dynamically adjust feature weights across NEV market stages. Wang et al.’s autoregressive model found price-related prediction differences [47], with weaker performance for high-priced NEVs, highlighting overlooked price-specific calibration needs. These studies show multi-source fusion evolution but lack adaptability to NEVs’ unique traits.

2.3. Summary and Research Gaps

A review of existing literature reveals a wealth of studies on vehicle sales forecasting, featuring diverse research methods and perspectives that cover various forecasting models. However, these studies mostly focus on optimizing forecasting models or algorithms and their applications in different contexts (such as countries or time frames). For instance, some analyze the impact of macro-factors on vehicle sales. These factors include fluctuations in fuel or electricity prices, changes in consumer income levels, and variations in highway mileage or patent counts; others concentrate on improving forecast accuracy by comparing models (such as time series, regression, or machine learning) to select the optimal one. Given the relatively short development history of NEV, in-depth research on NEV sales forecasting remains limited, leaving significant research gaps and market value in this field.

From the literature on vehicle sales forecasting, most scholars rely on historical sales data for predictions. Many studies prioritize traditional macro-indicators (such as GDP growth rate, unemployment rate). While these indicators are important, they fail to fully reflect market dynamics and the diversity of consumer behavior. With the development of the Internet, online reviews and social media data have become critical information sources for consumer decision-making, yet existing research often overlooks or does not sufficiently consider these factors. For example, analyzing online reviews and social media data could reveal consumers’ emotional attitudes toward NEVs, thereby predicting potential purchase behavior. Moreover, word-of-mouth (WOM) spread on social media exerts a significant impact on vehicle sales, a factor that existing studies also rarely adequately addressed. Although some scholars have developed models by combining historical sales data with traditional economic indicators, few have incorporated WOM review-related features. Additionally, researchers have not yet established unified standards for researching WOM reviews. Furthermore, many studies rely on a single data source—primarily official statistical data—while neglecting other potential sources; they mostly focus on structured data (such as sales volume, price, or economic indicators), failing to effectively leverage the value of unstructured data. Also, while official data is reliable, it has low update frequency and inherent lag, making it difficult to reflect real-time market changes.

With the popularization of the Internet, online WOM reviews increasingly influence consumers, and automotive manufacturers are paying greater attention to user reviews on online media. Therefore, integrating user online reviews with traditional indicators can establish a more comprehensive sales forecasting index system, enabling more holistic capture of factors affecting sales. Traditional indicators provide macro and overall market trends, while online reviews offer real-time consumer feedback and emotional attitudes. The combination of these two can better utilize multi-source data, enrich model inputs, and improve the reliability, accuracy, and precision of forecasts. This holds significant value for the expansion and application of NEV sales forecasting models.

3. Basic Model Selection

Our research focuses on comparing four models: Support Vector Regression (SVR), Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), Long Short-Term Memory Network (LSTM), and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU). These four models represent different types of algorithms: GRU and LSTM are typical recurrent neural networks suitable for time series data with long-term dependencies; CNN excels at extracting spatial or local features, which can be valuable for capturing patterns in sales data; and SVR is a traditional machine learning-based model based on statistical learning theory. By comparing these representative models, we aim to provide clear insights into the performance of different model types in the specific context of predicting Chinese NEV sales, considering factors such as model complexity, interpretability, and prediction accuracy.

3.1. Support Vector Regression (SVR)

As a type of time series prediction task, NEV sales prediction involves various models. The Support Vector Machine (SVM) is a machine learning-based model for solving separable binary classification problems. It appeared earlier and is widely applied [12]. The algorithm in this model maps the low-dimensional nonlinear data to the high-dimensional linear space through a kernel function and constructs an optimal hyperplane in this high-dimensional space to separate all samples in the feature space. The sample point closest to the optimal hyperplane is known as a support vector. Through the support vector, we can calculate the hyperplanes α1 and α2 on both sides of the optimal hyperplane. The larger the distance between α1 and α2, the more reliable the classification result. When SVM is applied to regression problems, it is referred to as SVR. The purpose of this algorithm is to find a regression hyperplane that is closest to all sample points. SVR can achieve the best prediction effect with only a small amount of sample data, which to a certain extent solves problems such as overfitting and local extremum. Its strong nonlinear modeling ability and flexibility make it have certain advantages in time series prediction.

The SVR estimation function is given by Equation (1):

In Equation (1), is the dimension of the feature space, is the mapping from low dimension to high dimension, and is the bias term. The optimization problem is given by Equations (2) and (3):

In Equations (2) and (3), is the insensitive factor, and are the relaxation variables, and is the penalty parameter. To solve Equation (2), the Lagrange multiplier method is introduced, as shown in Equations (4) and (5):

In Equation (4), is the sum function.

3.2. Convolutional Neural Network (CNN)

In addition to supporting vector machines, neural networks, as emerging models, have sparked research enthusiasm in many fields since their advent and have been applied to various tasks, including time series prediction. Research on neural networks often focuses on network structure optimization and hyper-parameter selection. During this process, researchers have proposed many excellent models. Among them, CNN [15] and RNN [16] are two representative improved models.

CNN is a type of deep neural network with wide applications and excellent performance, and it has extensive application value in many fields. Its core operation is to extract local data features through convolution calculation in the convolutional layer and then introduce activation function to enhance the nonlinear fitting ability of the model [15]. Meanwhile, a pooling layer is also set up in CNN to perform data down-sampling and feature dimensionality reduction. Due to the characteristics of convolutional operation and shared weights, CNN has obvious advantages in dealing with high-dimensional data. With the problem of sequence analysis in the context of big data attracting more and more attention, many studies have attempted to improve CNN to introduce sequence learning capabilities.

The principle of CNN for time series prediction is to use the ability of convolutional kernel to perceive changes in historical data over a period and make predictions according to the changes in this historical data. Pooling operations can retain key information and reduce information redundancy. Convolutional neural networks can effectively reduce the human resource consumption of feature extraction by previous algorithms and avoid the generation of human errors at the same time. The convolutional neural network requires a huge amount of sample input and is primarily utilized to predict datasets with spatial characteristics. Its internal structure consists of an input layer, convolutional layer, pooling layer, fully connected layer, and output layer.

3.3. Long Short-Term Memory Network (LSTM)

The sales volume of new energy vehicles usually varies over time, and future sales often depend on past data and market trends. Time series data has obvious order and dependence. RNN and its variants can effectively capture these long-term dependencies, whereas traditional time series analysis methods may struggle to handle complex long-term dependencies. RNN and its variants can be adapted and optimized for specific application scenarios. For example, researchers can modify parameters such as the size and number of hidden layers to adapt them to different datasets and prediction tasks. With the increase in data and the continuous training of the model, RNN can gradually enhance its prediction ability to adapt to the dynamic changes in the data. As a variant of RNN, LSTM neural network introduces input gate, forget gate, and output gate to save historical information and long-term state and uses gating to control the flow of information.

At time step t, the input and output vectors of the hidden layer of LSTM are and respectively, and the memory unit is . The input gate is used to control how much of the current input data of the network flows into the memory unit, that is, how much can be saved to , as shown in Equation (6):

In Equation (6), i represents the input gate, W and b represent the weight matrix and bias vector of the network.

The forget gate is a key component of the LSTM unit that controls what information to keep and what to forget and somehow avoids the vanishing and exploding gradient problems that arise when gradients are back-propagated over time. The forget gate controls the self-connecting unit and can determine which parts of the historical information will be discarded. That is the influence of the information in the last time memory unit on the current memory cell . The calculation is derived in Equations (7) and (8):

In Equations (7) and (8), represents the forget gate, represents the multiplication of corresponding elements, and W and b represent the weight matrix and bias vector of the network.

The output gate controls the influence of the memory unit on the current output value , that is, which part of the memory unit will output at time step t. The value of the output gate is given by Equation (9), and the output of the LSTM at time t can be obtained by Equation (10).

In Equations (9) and (10), represents the output gate, represents the multiplication of corresponding elements, W and b represent the weight matrix and bias vector of the network.

3.4. Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU)

The GRU neural network in RNN is a simplified version of LSTM, but it retains the advantages of LSTM in dealing with long short-term memory and can effectively avoid the gradient vanishing problem, so that the model can better capture long-term dependencies. Compared with LSTM, the structure of the GRU model is more simplified and its computational efficiency is higher. Through the gating mechanism (update gate and reset gate), GRU can control the flow of information and effectively capture the long-term dependencies in the time series. This is particularly important for sales volume prediction because long-term factors such as market trends and policy changes have a significant impact on sales volume.

In summary, in order to determine the appropriate prediction model, we select SVR in the traditional prediction model, CNN in the neural network, and LSTM neural network and GRU neural network in the recurrent neural network. It analyzes these four prediction models and selects the most suitable one according to the experimental results.

In our research, the GRU neural network is employed as the base predictive model, with further details presented in the Appendix A.

4. Proposed Model

When developing sales forecasting models, although GRU neural networks inherently handle long-sequence data, integrating the attention mechanism enables the model to better capture critical information at different time points in the sequence. This is particularly important for sales forecasting, as key factors such as residents’ consumption levels, technological development, and consumer attention may be distributed across different segments of the time series. A notable advantage of the attention mechanism is its ability to focus on relevant information while ignoring irrelevant data. It establishes direct dependencies between inputs and outputs without recursion, enhancing parallelization and significantly improving operational speed [48,49]. It overcomes limitations of traditional neural networks, including performance degradation with increasing input length, low computational efficiency due to unreasonable input order, and insufficient feature extraction and enhancement. Moreover, the attention mechanism effectively models variable-length sequence data, further strengthening its capability to capture long-range dependencies, reducing hierarchical depth and improving prediction accuracy [50].

Sales forecasting is essentially a time series forecasting task. The Sequence to Sequence (Seq2Seq) model can capture long-term dependencies in time series. The Seq2Seq model is a type of encoder–decoder structure. In the encoder–decoder framework, the encoder converts the input sequence into a vector containing specific information through recurrent neural network structures such as LSTM and GRU. After corresponding semantic encoding, the decoder then uses recurrent neural network structures to translate this vector into output information.

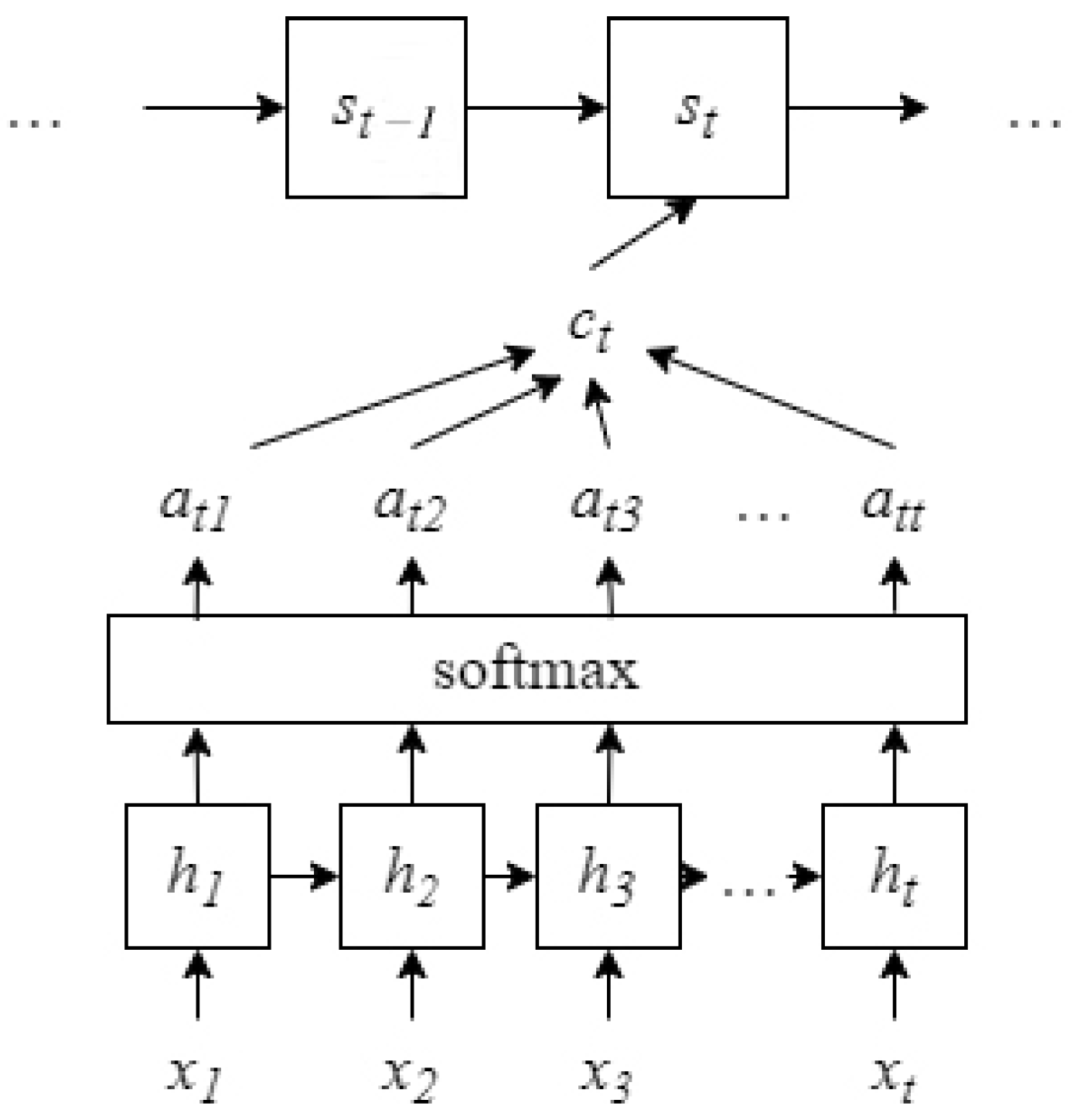

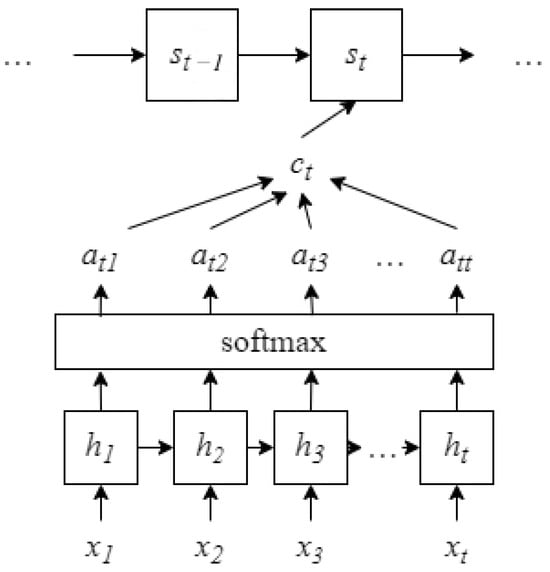

However, the performance of the Seq2Seq model degrades when the input sequence is too long, while the attention mechanism helps the model focus on the parts of the input sequence that are most relevant to the current prediction. The Attention mechanism focuses on contextual information by inputting different c at each time step. Each c performs a weighted summation of information from all hidden layers of the input sequence (h1, h2, …, hₜ) to select the contextual information that is most appropriate for the currently required output y, i.e., , where is the weight. The state output of the decoder at time t is derived from a nonlinear function of the previous state , , and , as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Attention-Seq2Seq Model.

In time series forecasting, Seq2Seq modeling with the attention mechanism via encoder–decoder architecture not only accommodates variable-length sequence data but also links the current input to the previous output and the model’s own state. This increases model complexity, thereby improving prediction accuracy and ensuring good scalability [51].

Therefore, this study takes the GRU neural network as the foundation to construct a Seq2Seq model where both the encoder and decoder are based on GRU neural networks. Additionally, we integrate an attention mechanism and discuss whether there are changes in the prediction accuracy among different models.

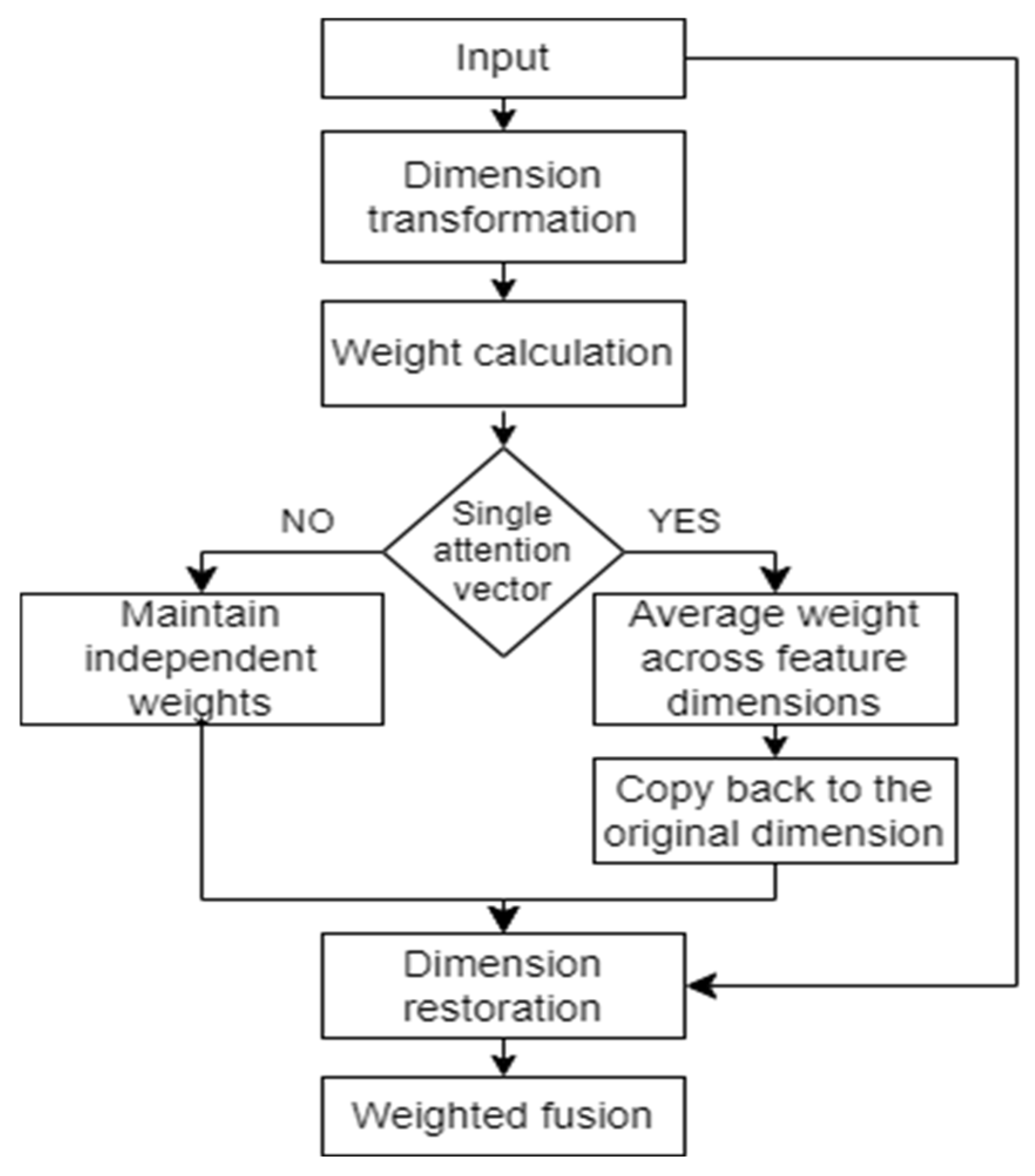

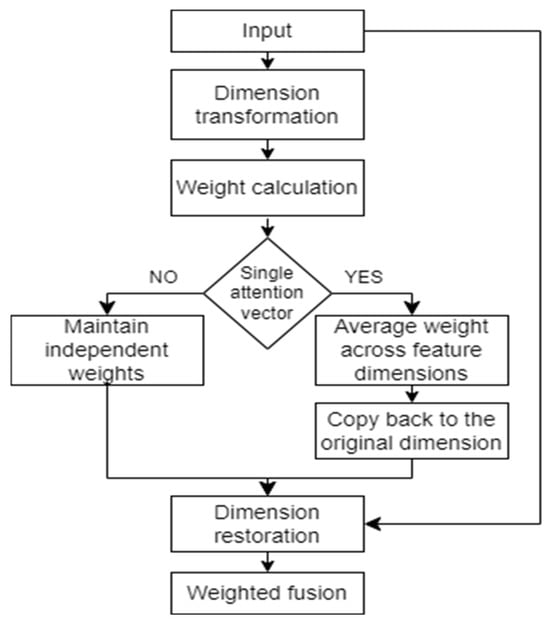

To facilitate valid comparisons between multi-variable and single-variable sales forecasting models, we minimize their structural differences as much as possible. The dataset was split into a training set (85%) and a test set (15%) for the NEVs forecasting models. The 85/15 partitioning adopted in the paper is a commonly used partitioning method in time series prediction tasks. Its purpose is to ensure that the training sequence of the learning model is long enough while retaining sufficient test data to evaluate the generalization ability. The selection of batch size is a balance point achieved between training efficiency and model stability under the existing computing resource conditions. During the training process, the loss curves of the training set and the validation set were closely monitored to confirm that the model tended to converge and no obvious overfitting or underfitting phenomena occurred. Three models were constructed: a standalone GRU neural network, a Seq2Seq model (with GRU for both encoder and decoder), and an attention-augmented Seq2Seq model (also using GRU for encoder and decoder). We set a random seed to ensure experimental reproducibility. For the NEV forecasting models, the number of neurons was set to 14, time steps to 3, batch size to 1, and training iterations to 500. The Attention-Seq2Seq model uses GRU to construct an encoder–decoder structure. After attention-weighting the input sequence, the encoder passes the final state to the decoder. The decoder output is processed through a fully connected layer and global average pooling to obtain a single predicted value. It adopts an auto-encoder training method: Train the sequence-to-numerical regression task using the same data as the codec input. Apply the attention mechanism to the encoder. The attention mechanism works by calculating independent time step attention weights for each feature dimension of the input sequence. First, perform dimension transformation on the input. Then, use the fully connected layer and the softmax activation function to generate attention weights. Finally, multiply these weights element-by-element with the original input to enhance the feature representation of important time steps and suppress unimportant time steps, enabling subsequent GRU layers to process the attention-weighted sequence information more effectively. The details are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Attention mechanism.

After training and testing each model, evaluation metrics including RMSE, MAE, MAPE, SMAPE, and MASE are used to assess their prediction accuracy.

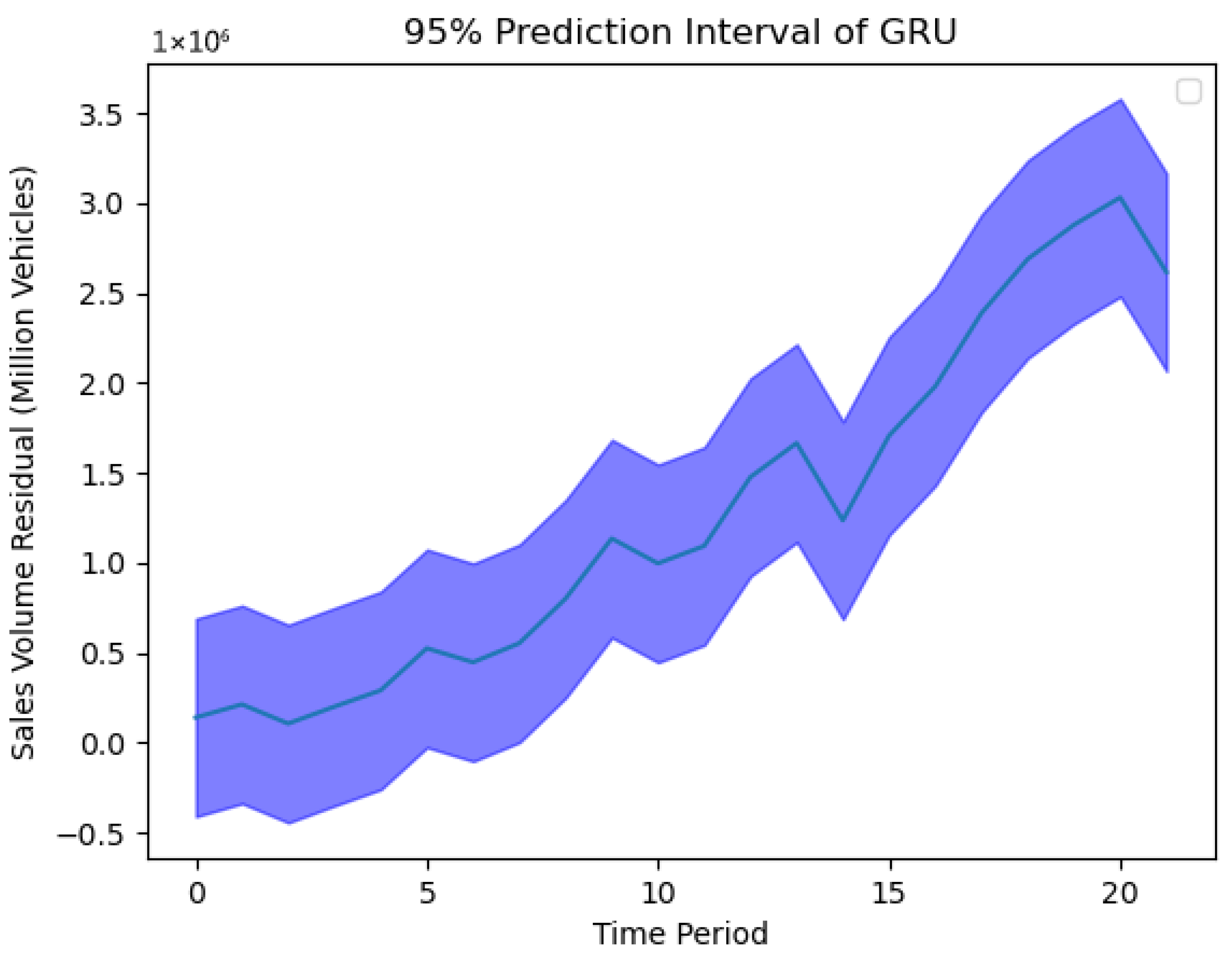

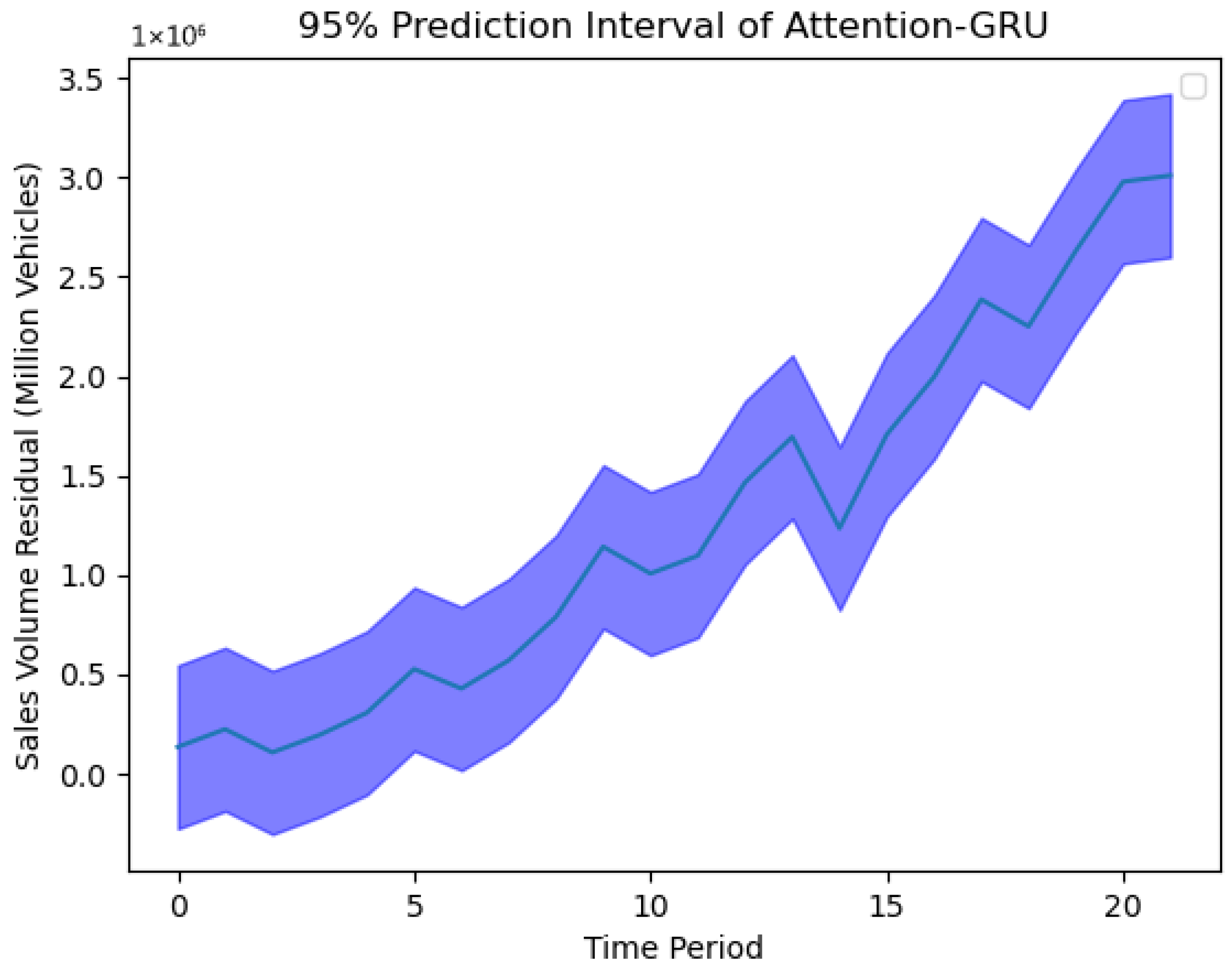

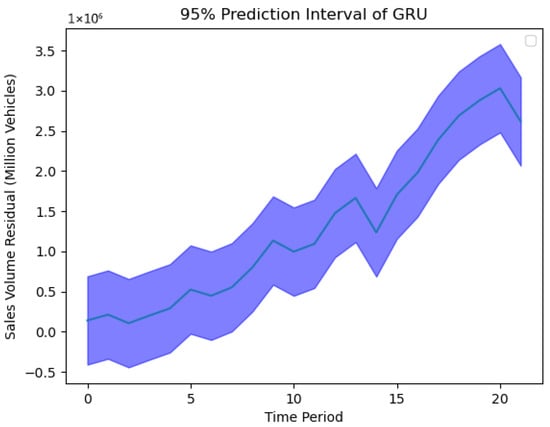

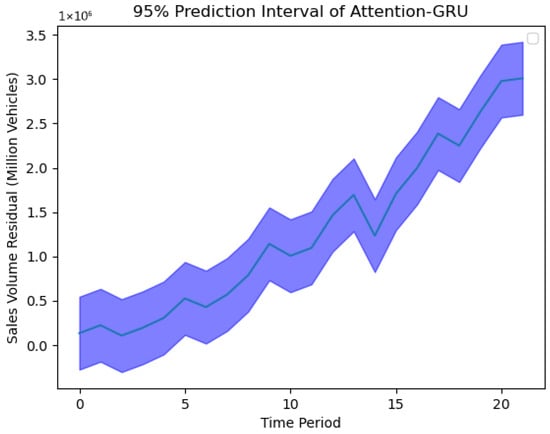

To explicitly demonstrate that models integrated with an attention mechanism outperform their counterparts without this mechanism in prediction accuracy, we conduct comparative experiments using GRU as the baseline architecture. Specifically, residual correlation plots and prediction interval plots are employed to visually quantify and contrast the performance disparities between the standard GRU model and the Attention-GRU model. The experimental results illustrated in Figure 3 and Figure 4 provide direct empirical evidence that incorporating the attention mechanism enhances predictive accuracy. Specifically, Figure 3 presents the prediction curve of the GRU model with its 95% confidence interval denoted by the purple area, while Figure 4 shows the Attention-GRU model’s prediction curve with the purple area representing its corresponding 95% confidence interval. The Attention model shows a noticeably tighter prediction interval compared with that of a regular GRU model. In other words, the more narrow the prediction interval is, the more precise the forecast result will be, since the smaller the prediction interval, the smaller the model’s uncertainty about the final output is and the higher confidence one can have in the model’s predicted values.

Figure 3.

95% Prediction interval of GRU.

Figure 4.

95% Prediction interval of Attention-GRU.

5. Data

The long-term development trend of the NEV industry is influenced by multiple factors. Therefore, when constructing a NEV sales forecasting model, it is necessary to consider various key factors affecting sales. Combining macro and micro perspectives, we incorporate the impact of online reviews on sales in addition to economic, policy, and technological factors. From these four dimensions, we select characteristic indicators of factors influencing NEV sales. We use the grey relational analysis method to rank and screen these indicators based on their correlation degrees and establish an NEV sales forecasting index system using the screened indicators.

5.1. Construction of the Indicator System

5.1.1. Principles for Constructing the Indicator System

A set of indicator systems aimed at NEV sales forecasting is established on the basis of four major principles to guarantee strictness and practicability.

In terms of the scientific principle, it demands that the system should abide by reliable data sources, rigorous measurement methods, adhere to objective facts, select representative indicators that can represent important influencing factors of the NEV industry, and conduct standardized data processing in line with scientific theory to ensure the scientific validity, rationality, and reproducibility of results, as well as eliminate bias.

Secondly, based on the principle of systematics, from the multi-level system composed of targets, criteria, and indicators, the coverage system for critical content in NEV sales was constructed. NEV sales are simultaneously affected by technology, consumer spending, policy, and infrastructure; therefore, relevant indicators needed to be selected at different levels and fields to fully reflect the industry’s development trend, ensuring an accurate evaluation.

Third, the operability principle provides that usable, measurable data (for example, that which is available via government platforms such as the National Bureau of Statistics) must be tracked, and done so in real time, at all times. The goal is to be able to produce data as proof and context when responding to questions from researchers and managers.

Another condition, the dynamic-stability criterion, keeps stability and adaptability in balance—when the market is different from before, dynamic forecast indicators are revised to suit the new circumstances; meanwhile, core indicators remain constant for a certain period of time, so long as the goal for predicting NEV sales does not change.

5.1.2. Analysis of Influencing Factors and Selection of Indicators

Given the multi-faceted influences on NEV sales, this study constructs a sales forecasting indicator system by analyzing key factors across four dimensions—economy, technology, policy, and consumers—supported by relevant theories and literature.

Higher economic levels stimulate NEV consumption, with economic scale impacting NEV promotion efficiency [52]. GDP and Urban Survey Unemployment Rate are selected to reflect macroeconomic conditions, while Per Capita Disposable Income and Per Capita Consumption Expenditure measure residents’ purchasing power—key to affording NEVs [53]. For industrial dynamics, NEV Industry Investment Amount, NEV Industry Investment Events, Automotive Aftermarket Investment Amount, and Automotive Aftermarket Investment Events capture industry attractiveness and post-sales service impacts. Gasoline Price is included, as oil price hikes positively influence NEV purchase intentions [54]. In total, nine economic indicators are chosen.

Technological advancement boosts NEV demand by enhancing battery performance, drive systems, and intelligence—directly increasing consumer purchase intent [48]. Tech progress outweighs financial subsidies in promoting NEVs [49]. Due to inconsistent tech metrics across NEV firms and opaque R&D, NEV Basic Patent Applications in China is selected to reflect industry innovation. Battery tech constraints (range, safety) make Power Battery Output and Total Power Battery Installation Capacity key indicators (scaled battery production supports stable industry growth). In total, two technological indicators are chosen.

NEV market dynamics are closely tied to industrial policies. Fiscal and tax incentives (e.g., vehicle purchase tax exemptions) boost NEV demand [50], so the Number of NEV-related Policies is selected to reflect policy support. Inadequate charging infrastructure causes range anxiety [55]; Public Charging Pile Quantity is chosen as it indicates government emphasis on NEV promotion (via infrastructure subsidies). Lower bank loan interest rates reduce purchase costs, stimulating demand. Thus, Bank Loan Interest Rate is included to capture financial policy impacts. Three policy indicators are chosen.

Online platforms reshape how consumers access information. Online reviews (sentiment/polarity) impact purchase decisions [56], so Review Volume, Average Sentiment Score, Positive/Negative Reviews, Most Probable Review Topic, and Topic-specific Sentiment Score are selected. Baidu Search Index reflects purchase intent [57]. Seven consumer indicators are finalized.

A total of 21 indicators were selected from the four dimensions to form the index system, which is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Preliminary selection table of NEV sales forecasting index system.

5.1.3. Data Sources

To balance data accessibility and processability, this study selects data spanning from July 2018 to December 2024. There are no missing data for each indicator from July 2018 to December 2024. Economic indicator data are sourced from the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) (monthly/quarterly data) and the Pan-Internet Venture Capital Project Information Database, processed at a quarterly time scale. Technological indicator data are obtained from national government websites, the China Automotive Power Battery Industry Innovation Alliance, and patent databases. Policy indicator data come from national government websites, the People’s Bank of China, and the China Charging Alliance. Among consumer-related indicators, Baidu Search Index data are retrieved from Baidu index.

For consumer-related indicators, online review data are derived from processing semi-structured text reviews, with the raw text sourced from Autohome website (https://www.autohome.com.cn/, accessed on 3 December 2025) and CHEZHIWANG (https://www.12365auto.com/, accessed on 3 December 2025). Autohome is recognized as one of China’s most influential and trusted automotive vertical platforms, with a proven track record of providing high-quality, user-generated content (UGC) and authoritative industry data. As of December 2024, Autohome’s mobile App has accumulated over 500 million downloads, with a monthly active user (MAU) count of 64.51 million and a panoramic ecosystem monthly unique user peak of 532 million [58]. Autohome is a trusted data partner for major NEV manufacturers (e.g., BYD, NIO, Xpeng) and government research institutions. CHEZHIWANG is a leading national platform specializing in automotive quality complaints and consumer feedback, with a focus on data integrity and objectivity. Its authority is firmly anchored in its institutional endorsements and collaborative partnerships: as an official member unit of China’s National Automobile Product Defect Clue Monitoring Network (founded in 2019), the platform operates under direct guidance and coordination with the State Administration for Market Regulation. Notably, Autohome and CHEZHIWANG platform have been widely adopted as reliable data sources by researchers in numerous high-impact, peer-reviewed journals for automotive-related studies [59,60,61,62]. This cross-referencing in scholarly literature further validates the credibility and scientific applicability of the review data derived from these platforms, aligning with the rigorous standards of academic research. Given their long-term focus on the automotive sector, broad user bases, long time spans of reviews, and large review volumes, Autohome and CHEZHIWANG are representative platforms for NEV user reviews. Thus, they are selected as the sources of online review data for NEVs in our research.

To address the inherent procedural limitations of text mining (e.g., subjectivity in sentiment classification, ambiguity in topic delineation) and further enhance the reliability and interpretability of sentiment/topic indicators derived from NEV online reviews, we present systematic validation experiments and standardized quality assessment metrics specifically designed for SnowNLP-based sentiment analysis and LDA-based topic modeling.

To examine SnowNLP in classifying NEV review sentiment, a two-part validation experiment was performed. Firstly, we used stratified random sampling from the 97,887 preprocessed reviews, choosing 1000 of them, equally representing every quarter between 2018Q3 and 2024Q4 (≈40 reviews per quarter) and ensuring time periods coverage and randomness. We annotated these reviews manually with a scale from −1 (Negative), 0 (Neutral), +1 (Positive), among which annotation consistency was estimated using Cohens Kappa Coefficient, which obtains a value of 0.87, exceeding 0.75, meaning high consistency [43], which shows the confirmation of gold standard.

Second, the SnowNLP model was tested against this gold standard, with the following performance metrics: accuracy = 92.3%, macro-averaged recall = 91.7%, and macro-averaged F1-score = 0.91. Among them, positive reviews achieve the highest recall (93.5%), while negative reviews have a recall of 89.2%—a minor gap attributed to the low proportion of negative reviews (≈8.3% of the total dataset).

The quality of the LDA topic model is evaluated using two core metrics: perplexity (measuring model generalization ability) and coherence score (measuring semantic consistency of topics). For the NEV review corpus, when the number of topics K = 8 (determine via grid search over K = 5, 8, 10, 12), the model achieve perplexity = 892.

To address ambiguities in data processing procedures, this section clarifies technical specifications for text preprocessing and provides a rationale for normalization methods, along with statistical results.

Noise Removal: Irrelevant characters (including emojis, special symbols like “★” or “→”, and non-Chinese/English text) are removed using the regular expression r‘[^\u4e00-\u9fa5a-zA-Z0-9\s]’. Domain-specific terms (e.g., “kW·h”, “fast charging”) are retained to avoid information loss.

Redundant Review Filtering: Duplicate reviews (identical text and posting time) and short reviews (<5 Chinese characters, e.g., “Good” or “Decent”) are excluded, reducing the corpus from 112,345 to 97,887 valid reviews.

Stopword Removal: A hybrid stopword list is used, combining the Harbin Institute of Technology’s general Chinese stopword list (782 terms, e.g., “of”, “because”) and a custom NEV domain stopword list (68 terms, e.g., “automobile”, “vehicle”, “new energy”—terms that appear in >90% of reviews and lack discriminative value).

Word Segmentation: The Word Segmentation library’s “precise mode” is used, with a custom dictionary of 320 NEV-specific terms (e.g., “driving range”, “public charging pile”, “battery degradation”) added to improve segmentation accuracy. Post-segmentation validation show that domain terms are correctly split in 95.7% of cases (vs. 82.3% without the custom dictionary).

To address concerns about indicator reliability, we take concrete measures to ensure reproducibility and validate indicator robustness across time and tools.

All experiments involving randomness are strictly controlled to ensure results can be replicated:

Random Seed Fixing: Key tools and libraries use fixed random seeds:

Python version 3.13 base randomness: random.seed(42)

TensorFlow (for model training): tf.random.set_seed(42)

LDA topic modeling (via gensim): random_state=42

SnowNLP sentiment analysis: snownlp.seed(42)

Three experiments are conducted to verify that sentiment and topic indicators are stable across time, tools, and parameter changes:

Temporal Consistency Test: The dataset is split into two periods—Q3 2018 to Q4 2021 (Phase 1) and Q1 2022 to Q4 2024 (Phase 2). The grey correlation between sentiment X17 and NEV sales is 0.81 in Phase 1 and 0.83 in Phase 2; the correlation for X16 is 0.89 and 0.91, respectively. Differences confirm that indicators maintain consistent predictive relevance over time.

Cross-Tool Validation: The same 1000 annotated reviews are analyzed using two alternative tools—BosonNLP (Chinese sentiment analysis) and TextBlob (English sentiment analysis, for bilingual reviews). Pearson correlations between SnowNLP scores and BosonNLP/TextBlob scores are 0.93 and 0.88, respectively, indicating high consistency across tools.

LDA Parameter Sensitivity Analysis: The number of topics K is varied (K = 5, 8, 10, 12) to test topic stability. The top 3 keywords for “driving range & charging” (Topic 1) remained unchanged across all K values, and coherence scores only fluctuated between 0.72 and 0.76. This confirms that topic indicators are not sensitive to minor parameter adjustments.

The data is presented in Table 2, where indicator names are replaced with simplified symbols; “Y” denotes quarterly NEV sales, and “Q3 2018” represents the third quarter of 2018.

Table 2.

Data of preliminary selection indicators for NEV sales forecasting.

As shown in Table 2, the number of online reviews increased by about 58 times from the third quarter of 2018 to the fourth quarter of 2024, indicating that online discussion and consumer interest in NEVs have exploded in the past few years. The period from 2018 to 2019 is a slow start. The number of comments begin to grow slowly from a relatively low base. In 2019, the number of quarterly comments increase from 283 to 747, reflecting the gradual rise in consumers’ attention to NEVs in the early stage of the market. The period from 2020 to 2021 is a time of rapid growth. The number of comments increases from 561 to 1999 in 2020 and from 1736 to 4758 in 2021, with the growth rate significantly accelerating. This may be associated with the surge in online activities during the epidemic, the implementation of government subsidy policies, and the launch of popular car models. The period from 2022 to 2023 experiences a slowdown in growth or a plateau. The number of comments continue to increase in 2022, but the growth rate slows down (from 3905 to 6914), and even a quarterly decline occurs in 2023. This may be due to market saturation, supply chain issues, or economic uncertainties, which have temporarily stabilized the discussion heat. The year 2024 will be a strong rebound period, with the number of comments increasing significantly from 4150 to 12,799, reaching a peak in the fourth quarter. This may be attributed to the maturity of NEV technology, the frequent launch of new models, price wars that stimulate consumption, and the global carbon neutrality goal driving long-term demand. Data shows that the number of reviews is often higher in the fourth quarter, which may be related to year-end promotions, auto shows, or consumers’ car-buying decisions during holidays. As shown in Table 2, the emotional score rose from 0.783 in the third quarter of 2018 to 0.917 in the fourth quarter of 2024. The overall emotional score shows an upward trend, reflecting that consumers’ attitudes towards NEVs are gradually becoming more positive. The upward trend of emotional scores clearly reflects the transition process of the new energy vehicle industry from the introduction stage to the mature stage. Consumers have gradually shifted from initial observation and doubt to positive evaluation, which is attributed to the overall development of the industry and the support of the social environment. In the future, the emotional score may remain at a relatively high level, but it is necessary to pay attention to fluctuating factors (such as economic conditions or technical malfunctions) to maintain consumer confidence. In addition, the data of external related influencing factors have all increased to varying degrees, reflecting that the development environment for NEVs is relatively favorable.

Numerous factors influence NEV sales, yet an excessive number of input indicators would overcomplicate the model, hindering its ability to solve practical problems efficiently. Additionally, not all preselected indicators exhibit strong correlation or high impact on NEV sales. Therefore, it is necessary to screen the 21 preselected indicators before incorporating them into the NEV sales forecasting index system as model inputs.

5.2. Establishment of a Forecasting Indicator System Based on Grey Relational Analysis

Among methods for analyzing NEV sales influencing factors, grey relational analysis (GRA) has low data requirements, making it suitable for the NEV industry where rapid development has resulted in relatively limited historical data. Moreover, GRA can comprehensively examine relationships between multiple influencing factors and sales, facilitating a holistic understanding of the sales impact mechanism.

In this study, NEV sales data is used as the reference sequence, while 21 influencing factors (including gross domestic product (GDP) and per capita disposable income of urban residents) served as comparison sequences. Due to the rapid development trend of the NEV industry, its indicator data show approximately exponential growth characteristics and significant volatility in data distribution. To improve the accuracy of subsequent analysis, the Z-score normalization method is adopted to standardize the original data: for each variable in the time series, the difference between its actual value and the mean value is divided by the variable’s standard deviation. After data normalization, we conduct grey relational analysis; the analysis results and ranking are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

The result of grey relational analysis.

Table 3 shows that indicators related to technology, policy, economy, and consumers have varying correlations with NEV sales—some high and others low. This is due to the following reasons:

Dependence on electricity-related factors: Due to the unique nature of NEVs, their sales are particularly reliant on electricity-related factors. For example, the technological standards of the power batteries in NEVs determine the driving range and obviously affect users’ needs because NEVs whose ranges are longer can satisfy more customer requests. Moreover, improvements to the power batteries will make their charges faster, shorten the charging time, so they offer better user experience.

Impact of public charging facilities on the NEV market: People tend to accept the NEV market more if the distribution density of public charging piles is higher and charging convenience is better. Battery range is limited, so NEV customers need frequent charging. With more popularization of charging piles, more charging points can be added, which improves the practicability of NEVs.

The role of online user reviews is to allow consumers to give direct opinions on the NEVs and thus tell their real product use experience. Positive reviews enhance potential consumers’ purchase confidence, while negative reviews may inhibit purchase intentions. Different review topics also affect consumer purchase decisions—for example, reviews highlighting strong power performance of a specific NEV brand will attract consumers with similar preferences.

Lagged and indirect impact of the aftermarket: The automotive aftermarket (e.g., maintenance, servicing, spare parts) primarily serves existing vehicles rather than directly influencing new car purchase decisions. NEV sales depend more on pre-purchase factors such as policy incentives, technical performance, and price competitiveness. The impact of aftermarket activities on sales is lagged or indirect, which results in relatively low correlation.

Diluted impact of interest rates: Although loan interest rates may affect car purchase costs, NEV consumers are more sensitive to direct subsidies (e.g., purchase tax exemptions, local subsidies) or usage costs (e.g., charging fees, battery leasing). If policy subsidies are substantial, the marginal impact of interest rates may be diluted.

Based on the grey relational analysis results, the overall indicator correlation is greater than 0.6, which indicates a strong correlation with sales. To further improve the accuracy of the forecasting model, this study identifies indicators with a correlation greater than 0.7 (among the 21 preselected indicators) as highly correlated with NEV sales. Specifically, the top 18 indicators by correlation are selected to construct the NEV sales forecasting index system, which serves as the input data for the model. The NEV sales forecasting index system is presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

NEV sales forecasting index system.

Finally, 18 indicators are identified to establish the NEV sales forecasting index system, which provides data input for subsequent sales forecasting.

6. Results

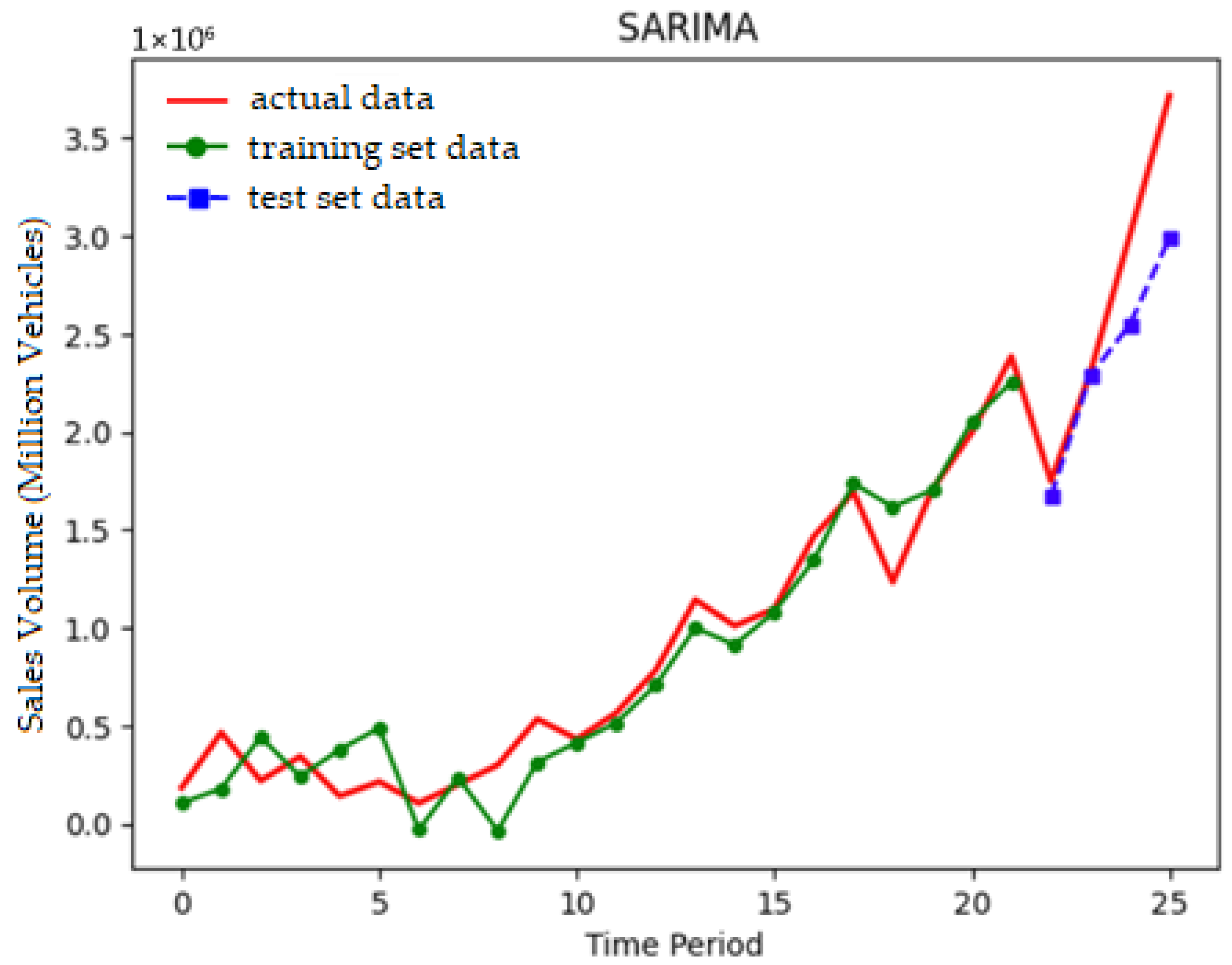

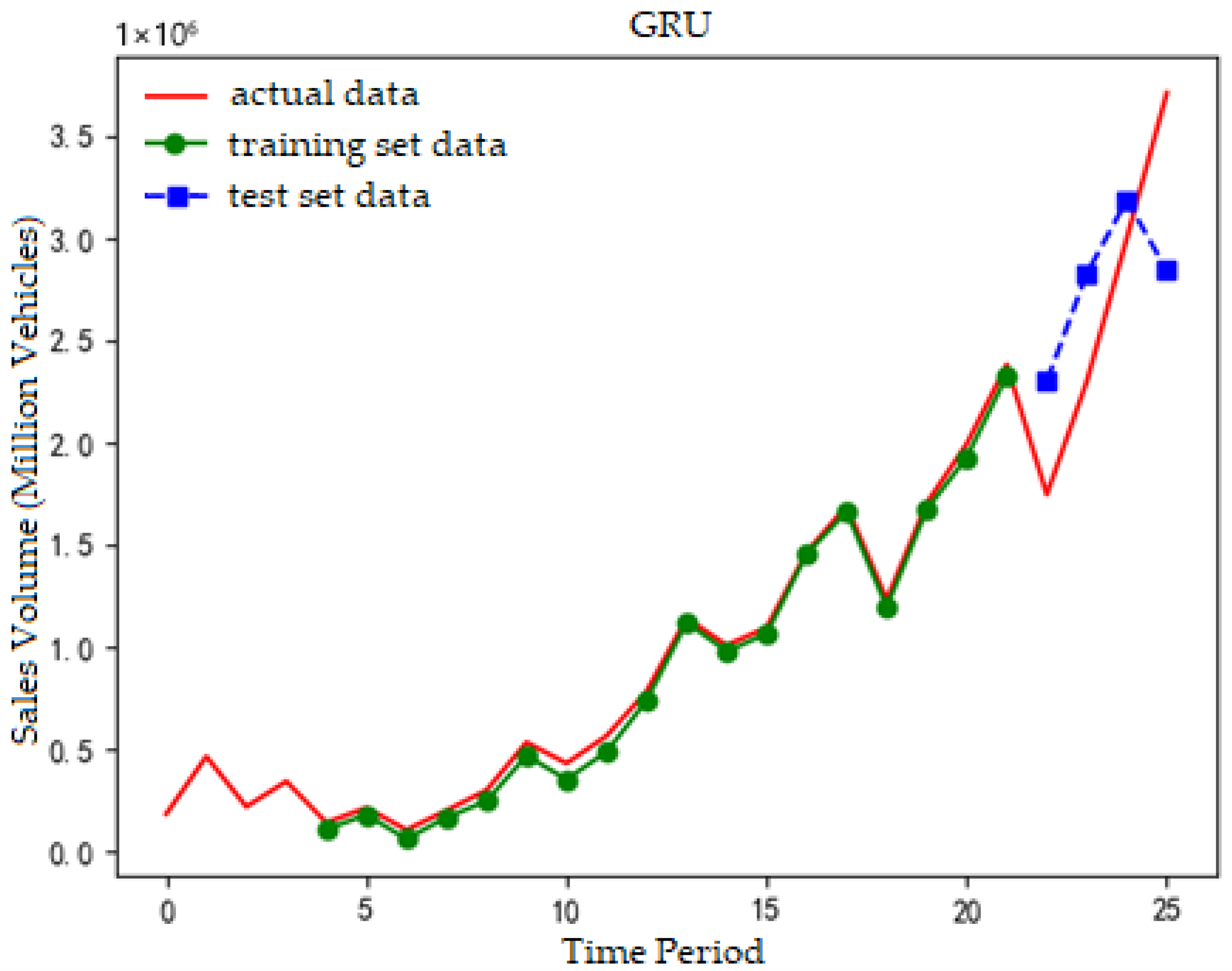

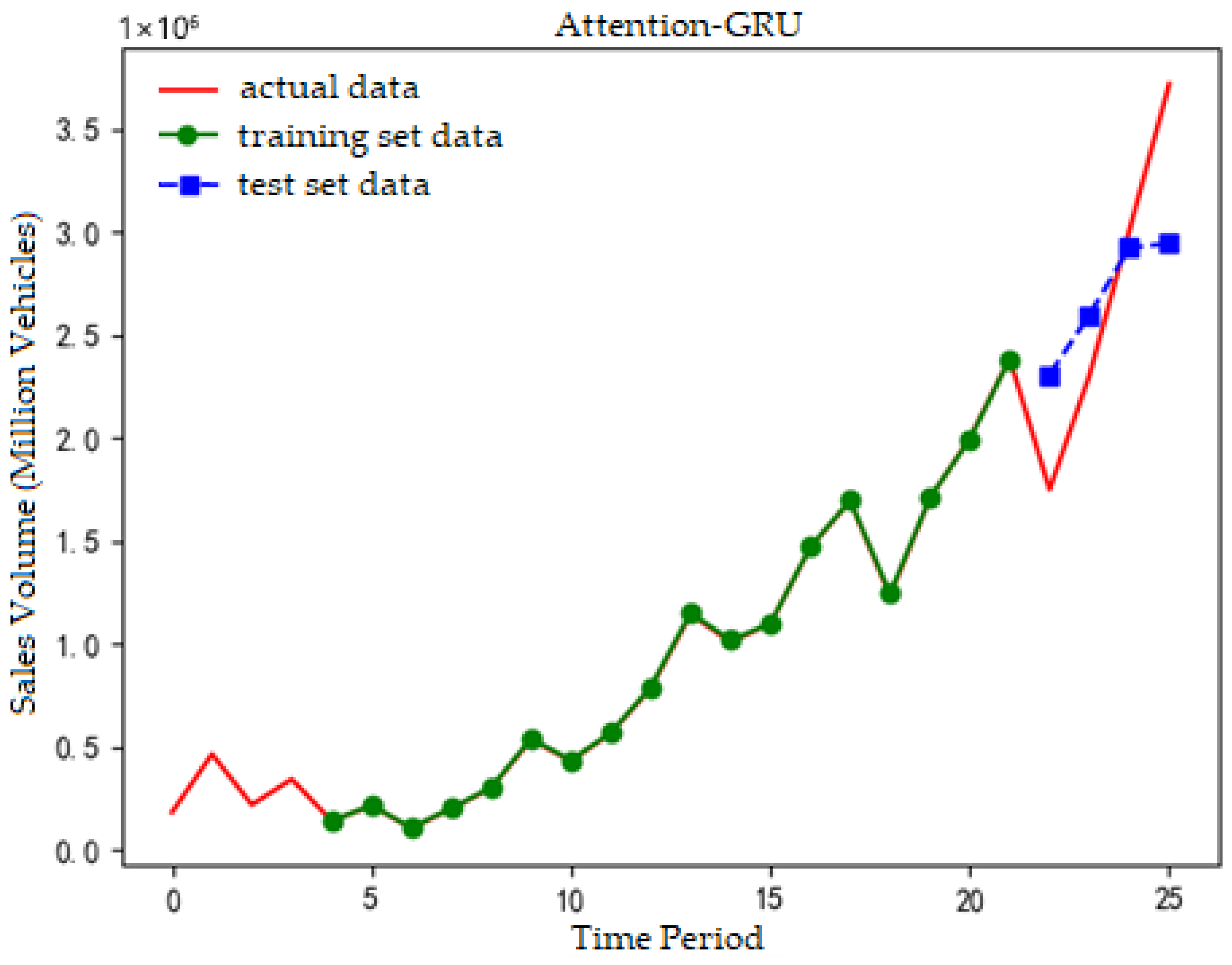

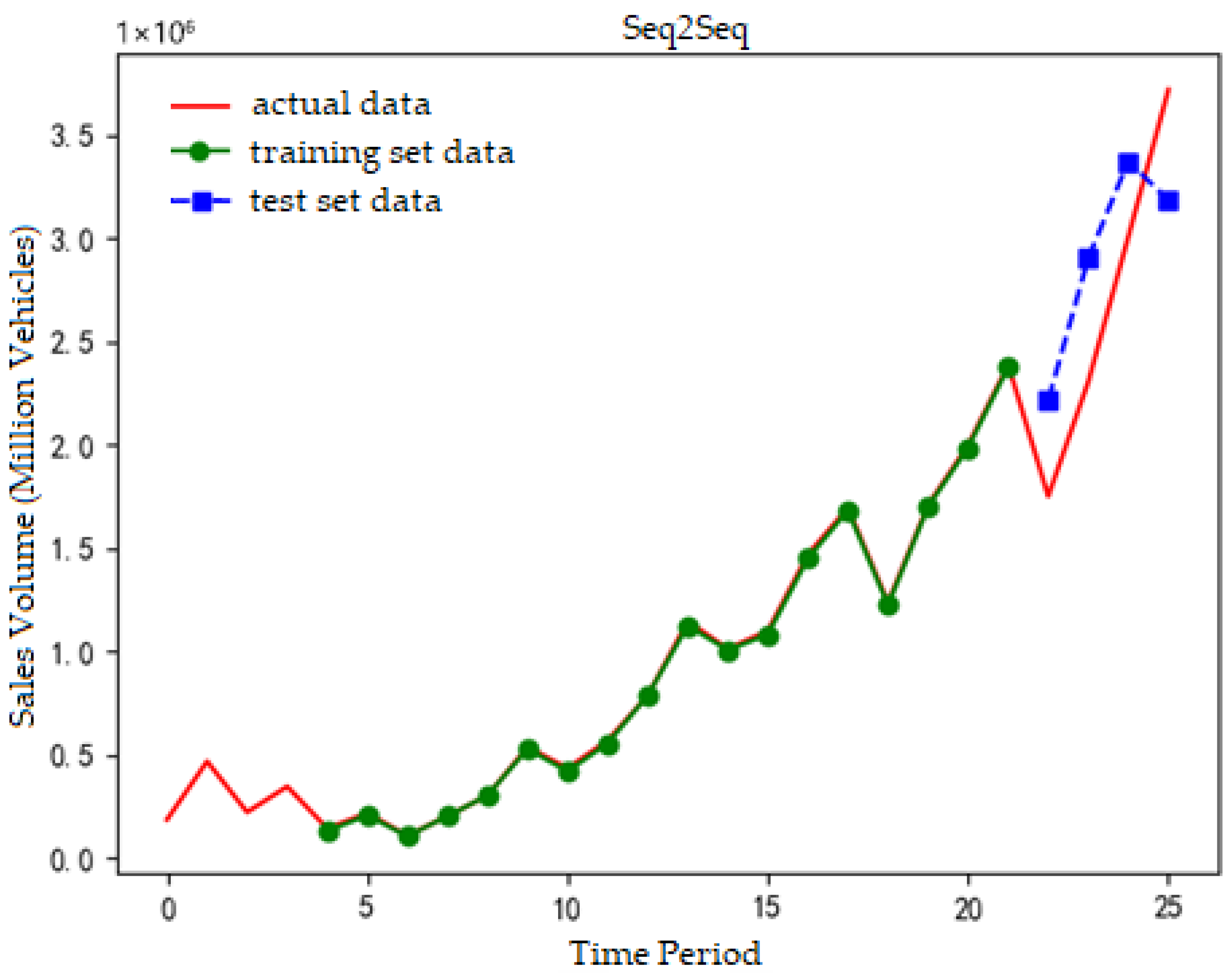

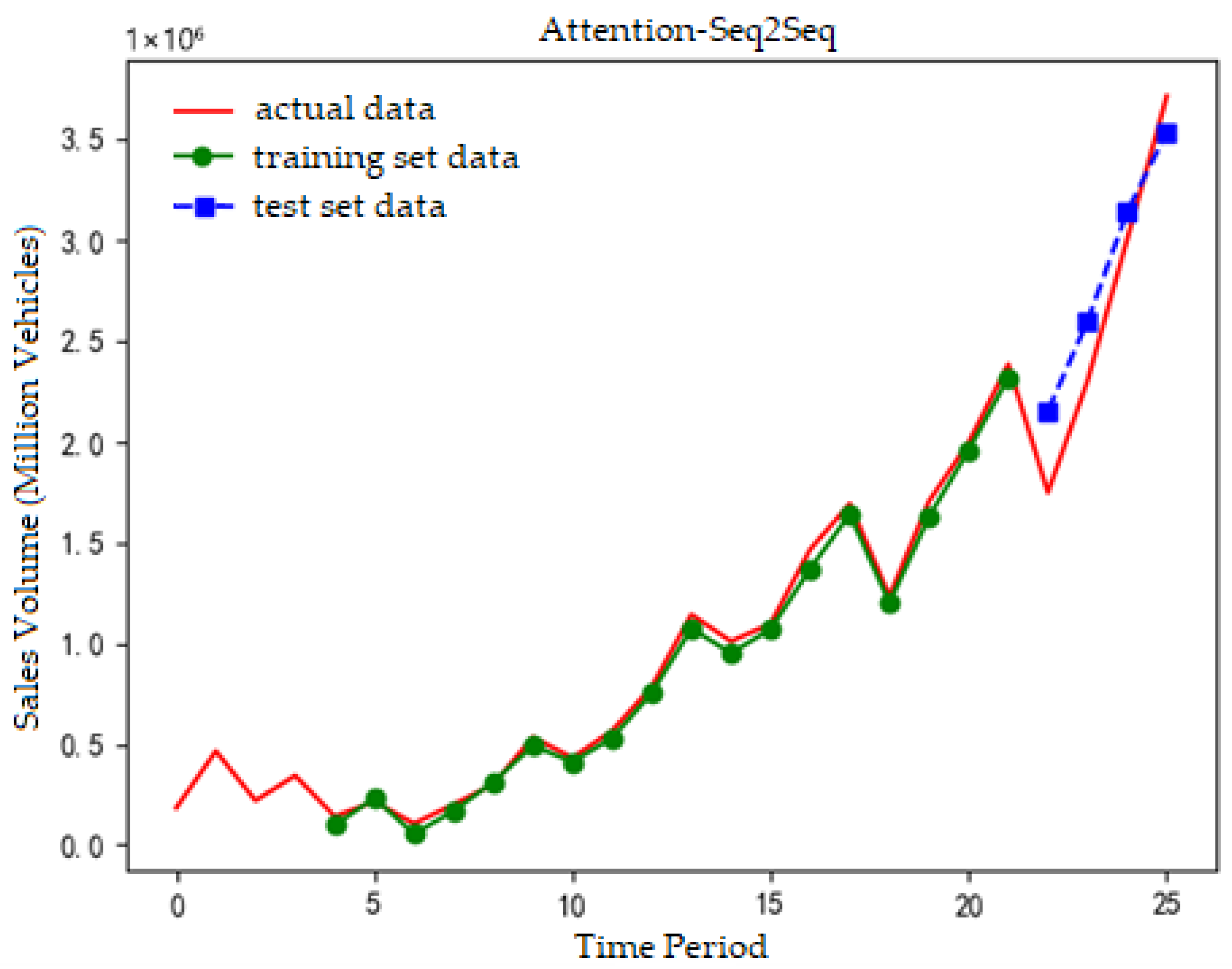

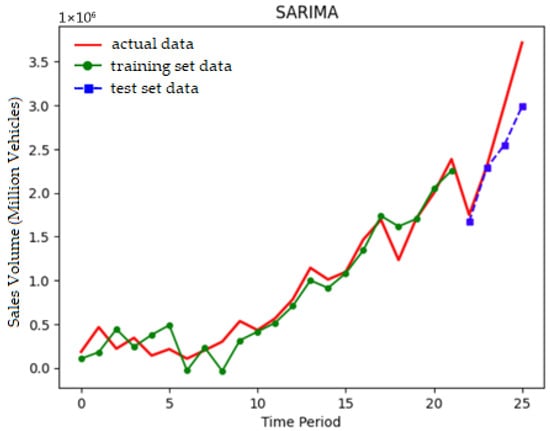

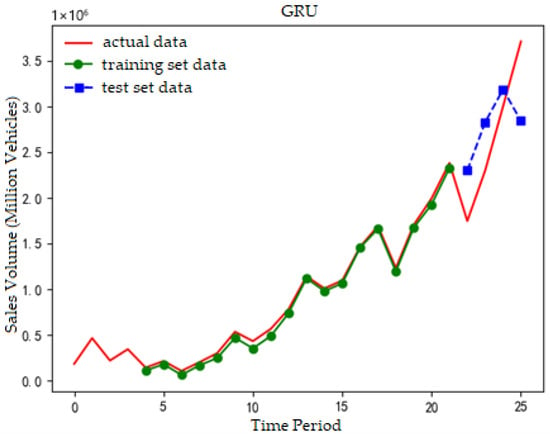

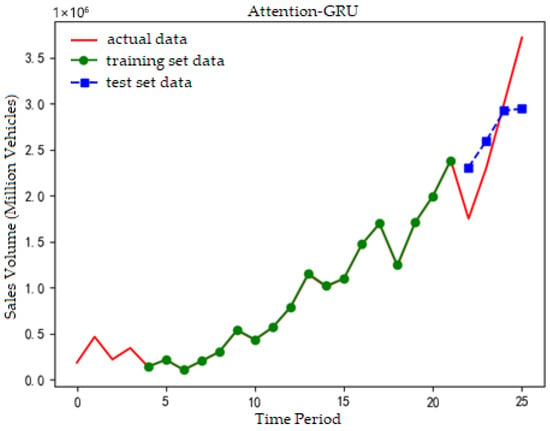

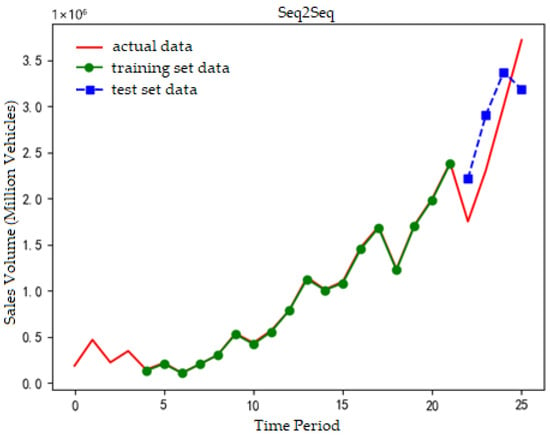

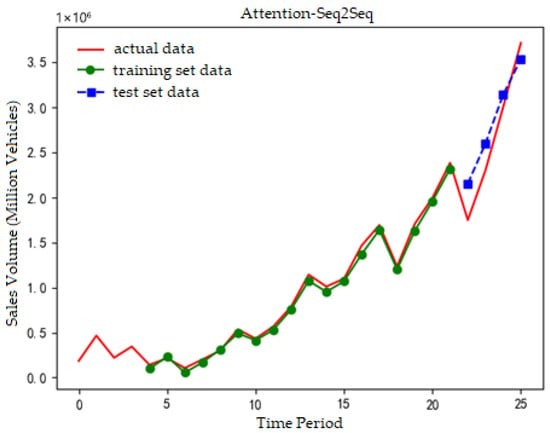

The prediction fitting results of the Attention-Seq2Seq model, along with the SARIMA, GRU neural network, Attention-GRU model, and Seq2Seq model, are presented in Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9. In these figures, the red line represents actual sales volume, the green line denotes training data derived from the training set, and the blue line indicates test data from the test set.

Figure 5.

SARIMA sales forecasting model.

Figure 6.

GRU sales forecasting model.

Figure 7.

Attention-GRU sales forecasting model.

Figure 8.

Seq2Seq sales forecasting model.

Figure 9.

Attention-Seq2Seq sales forecasting model.

In Figure 5, the actual data exhibits an overall linear upward trend, and the training data fits relatively well with it; yet the test data, though generally trending upward, has a deviated fluctuation rhythm from the actual data and fails to follow the latter’s rapid rise in the later period, indicating a certain prediction error of the SARIMA model.

In Figure 6, the test data shows a trend of first increasing then decreasing, while the actual data exhibits a linear upward trend, indicating a certain prediction error of the model.

In Figure 7, the test data shows a trend of first increasing then stabilizing, which contrasts with the linear upward trend of actual data and results in a certain prediction error.

In Figure 8, the test data shows a trend of first increasing then decreasing, which is inconsistent with the linear upward trend of actual data and leads to a certain prediction error.

In Figure 9, both the test data and actual data exhibit a linear upward trend, with the predicted data closely matching the actual values.

Detailed evaluation metrics of each model are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Indicator data of NEV forecasting model.

As shown in Table 5, compared with the GRU network, the Attention-GRU model reduces RMSE by 14.73%, MAE by 20.19%, MAPE by 19%, SMAPE by 18.60%, and MASE by 54.39%.

The Seq2Seq model (with GRU as both encoder and decoder) achieves higher prediction accuracy than the GRU neural network, with RMSE reduced by 15.06%, MAE by 8.16%, MAPE by 6.03%, SMAPE by 8.7%, and MASE by 55.84%. When compared with the Attention-GRU model, the Seq2Seq model shows a 0.39% reduction in RMSE but increases in MAE (15.06%), MAPE (16.01%), SMAPE (12.16%), and MASE (2.75%), which indicates mixed performance between the two models.

The Attention-Seq2Seq model outperforms the other models across all metrics:

Versus the GRU neural network: RMSE (−53.08%), MAE (−52.35%), MAPE (−45.99%), SMAPE (−47.44%), and MASE (−77.62%).

Versus the Attention-GRU model: RMSE (−44.97%), MAE (−40.3%), MAPE (−33.31%), SMAPE (−35.43%), and MASE (−51.22%).

Versus the Seq2Seq model: RMSE (−44.75%), MAE (−48.11%), MAPE (−45.52%), SMAPE (−42.43%), and MASE (−51.22%).

These comparisons confirm that the Attention-Seq2Seq model delivers superior performance in multi-variable NEV sales forecasting compared to SARIMA, GRU neural network, Attention-GRU, and Seq2Seq models. This superiority can be attributed to three key factors:

First, compared with single-GRU, the encoder–decoder method fully utilizes the advantage of neural network to some extent. During each step of processing, it takes into consideration all time steps of the input sequence rather than only the output value from the previous time step of the input sequence; hence, longer-term dependencies can be represented effectively with the help of attention mechanisms. Also, the attention mechanism makes the model choose to emphasize specific input components at certain time steps.

Secondly, although GRU can manage dependencies, it is hard to deal with complicated sequences; Different from GRU (one input and one output processed each time step), Seq2Seq’s encoder–decoder structure passes and utilizes information more efficaciously to pick up complicated sequences’ relations. But the standard Seq2Seq obtains a constant-length context vector from the encoder which causes some degrees of information loss. By applying the attention mechanism, the decoder can have direct access to the encoder’s all-hidden states and acquire relevant knowledge via dynamically choosing right pieces of information instead of using a constant-length context vector which implies the essence of attention.

It turns out that in all the metrics, when compared with the traditional SARIMA model, the Attention-Seq2Seq model attains the best results. As for the metrics of the SARIMA model, the values are as follows: RMSE = 431358.49, MAE = 319875.05, MAPE = 10%, SMAPE = 10.87%, and MASE of 1.4276. In comparison, the Attention-Seq2Seq model shows reductions of 36.14% in RMSE, 20.33% in MAE, and 13.70% in SMAPE, while achieving a 47.36% lower MASE value. Although SARIMA shows a slightly better MAPE (10.00% vs. 11.37%), the comprehensive performance of Attention-Seq2Seq across all other metrics solidifies its advantage for multi-variable NEV sales forecasting. As a traditional statistical model, SARIMA does not require the introduction of an attention mechanism—its core is based on assumptions of linear trends and periodicity in time series, achieving prediction through parametric modeling. There is an inherent difference in design objectives between SARIMA and neural network models that rely on attention mechanisms to capture complex nonlinear dependencies, so SARIMA can exert its statistical modeling advantages without depending on this mechanism.

Third, the attention mechanism helps the model accurately focus on key information in the input sequence, while GRU provides strong sequence modeling capabilities. Their combination enables the model to capture complex input-output relationships more precisely, thereby improving prediction accuracy.

In addition, we performed a complete Diebold–Mariano test for four models, respectively, and created the p-value table as the result of the test. SARIMA acts as a benchmark, not a candidate. Our goal is to test neural network models’ significance via Diebold–Mariano, so SARIMA is excluded to focus on key comparisons.

Table 6 shows that Attention-Seq2Seq outperforms other three models. When compared to other models, the p-values of Attention-Seq2Seq (2.076, 2.958, 3.299) are all over 1.96, passing 95% at the 95% confidence level. It proves Attention-Seq2Seq performs better in the field of NEV sales forecasting.

Table 6.

p-value of Diebold–Mariano test for four models.

We also adopt rolling-origin cross-validation method to further explain the advantage of Attention-Seq2Seq. While MASE is a commonly used metric for static forecasting scenarios, it is excluded from the rolling-origin cross-validation evaluation because our research aims to validate the predictive accuracy and robustness of the Attention-Seq2Seq model for multi-variable NEV sales forecasting. RMSE, MAE, MAPE, and SMAPE provide a holistic assessment of model performance without relying on MASE’s scaling, which is prone to bias in time series data with structural changes. Table 7 is the output result.

Table 7.

Rolling-origin cross-validation outputs.

As shown in Table 7, the performance of Attention-Seq2Seq is excellent in each four metrics, respectively, with values of 10,764.68 ± 11,262.91, 490,049.38 ± 236,420.94, 18.40% ± 15.53%, and 18.66 ± 11.20%. The results are all far less than the outputs of the other four models.

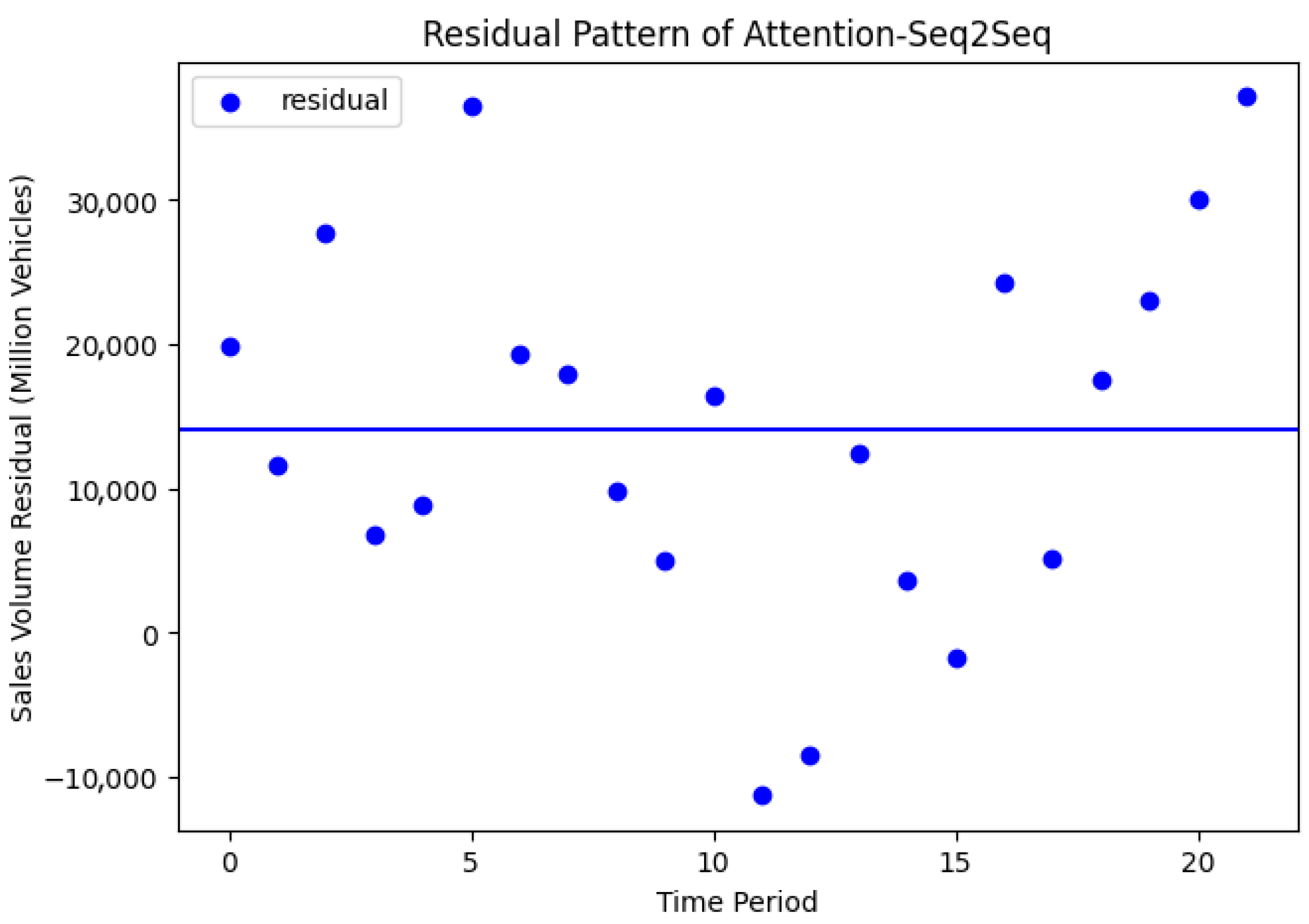

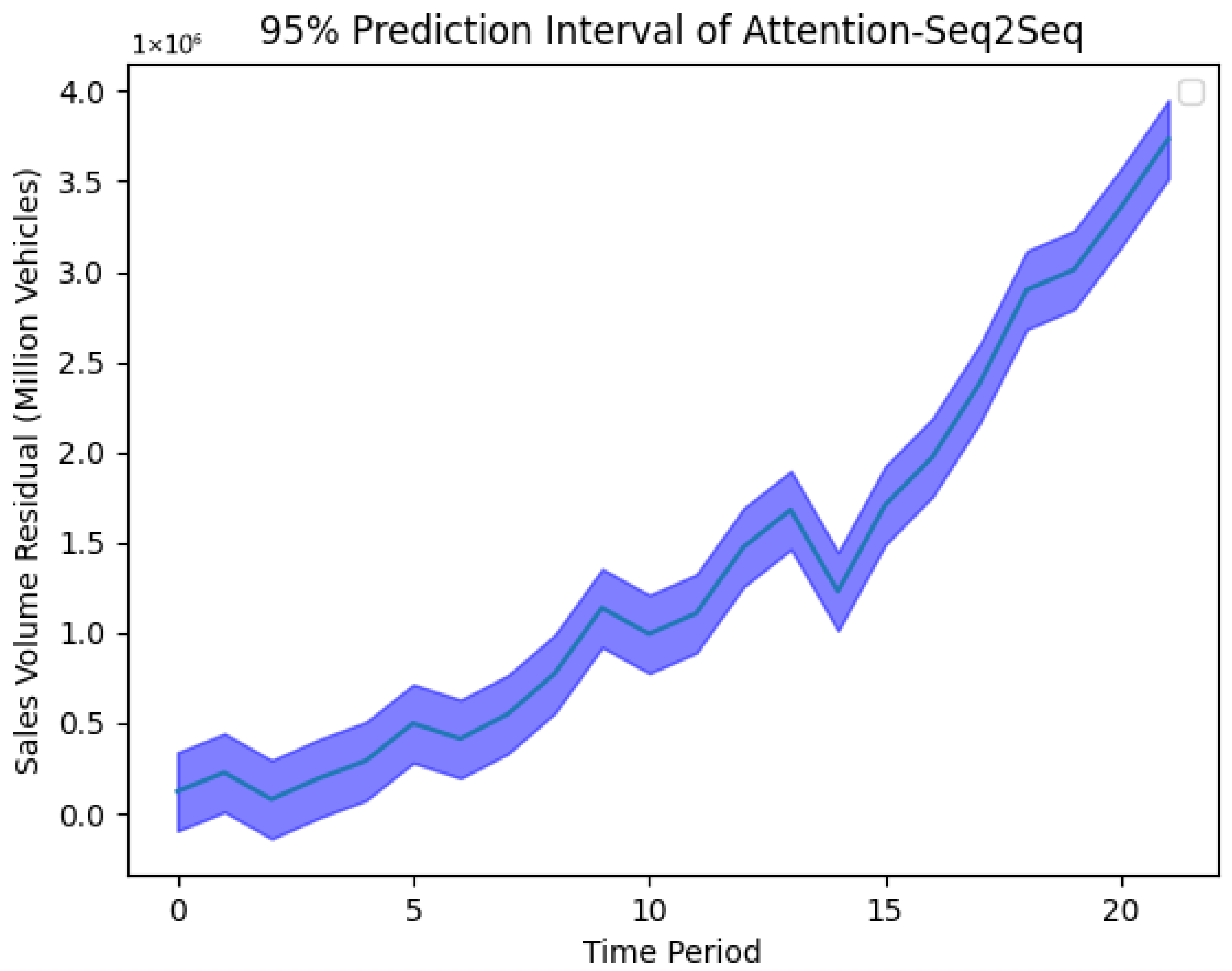

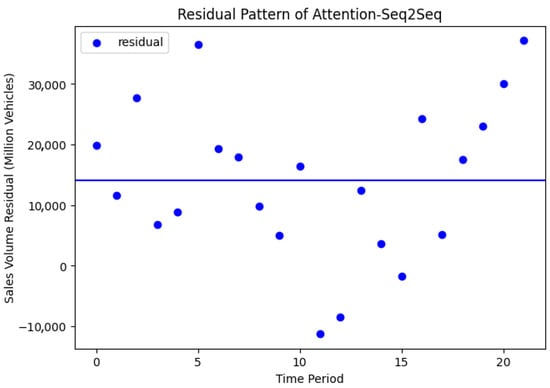

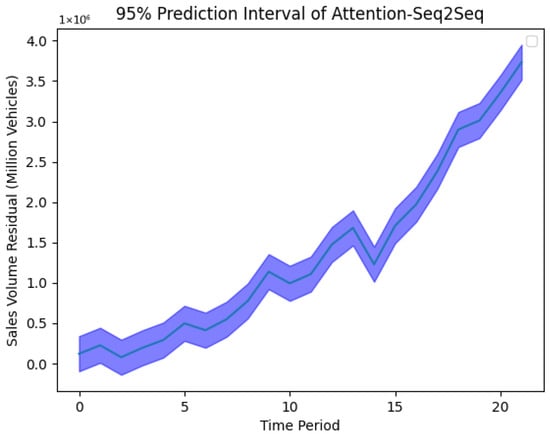

As we can see in Figure 10 and Figure 11, Attention-Seq2Seq overall performs excellent. It shows that model outputs have no residual correlation, and the prediction interval is small enough to support prediction effectiveness. In Figure 10, the distance between residual points and baseline clearly shows normal distribution and has no residual correlation. In Figure 11, the 95% prediction interval encapsulates the prediction curve; the purple area denotes the 95% confidence interval of the prediction curve generated by the Attention-Seq2Seq model. Notably, the prediction interval is sufficiently narrow, which ensures the reliability of the data predictions. Based on the above data comparisons and graphical illustrations, we can confidently conclude that the Attention-Seq2Seq model outperforms the other models, making it the optimal choice among the four candidates.

Figure 10.

Residual pattern of attention-Seq2Seq.

Figure 11.

95% Prediction interval of attention-Seq2Seq.

7. Conclusions

Our research addresses the gaps in NEV sales forecasting research by integrating unstructured online review data with structured indicators and proposing an Attention-Seq2Seq model. Comparative experiments with SARIMA, GRU, Seq2Seq, and Attention-GRU models confirm that the proposed model improves prediction accuracy.

7.1. Theoretical Contributions

This work advances NEV sales forecasting through three distinct theoretical breakthroughs. First, existing studies primarily relied on structured data such as economic indicators, policy variables, and historical sales [19,22], with a few incorporating online reviews but only focusing on quantitative attributes or simple sentiment polarity [37,38,63], lacking integration of qualitative features such as review topics and sentiment intensity. This study fills the gap by integrating seven consumer-related indicators with economic, technological, and policy dimensions. Grey relational analysis confirms positive reviews and number of reviews rank among the top four influencing factors, verifying the predictive validity of unstructured data and extending multi-source data fusion paradigms. Second, traditional GRU/LSTM models treat features equally [28,31], while standard Seq2Seq suffers from long-sequence information loss [51]. The proposed Attention-Seq2Seq model combines a GRU-based encoder–decoder with a feature-specific attention mechanism. Comparative experimental results demonstrate that the proposed model outperforms other four models across RMSE, MAE, MAPE, SMAPE, and MASE. It provides empirical evidence for the effectiveness of integrating attention mechanisms with Seq2Seq in handling high-dimensional, nonlinear time series data, thereby supplementing the technical system of deep learning applied to sales prediction in emerging industries. Third, previous studies on NEV sales prediction have adopted fragmented indicator selection without systematic validation [21,64]. By contrast, this study adheres to scientific, systematic, and operable principles: it initially selects 21 indicators across four dimensions and subsequently identifies 18 high-correlation indicators via grey relational analysis. It addresses the issue of inconsistent variable selection in existing research and provides a replicable framework for future studies.

7.2. Practical Implications

This study generates tangible practical implications for NEV industry stakeholders and the broader landscape of emergent sectors, categorized into three key dimensions. First, the model provides data support for policy adjustment and infrastructure planning, facilitating rational subsidy allocation, tax incentive optimization, and charging facility layout refinement to promote sustainable NEV industry development. Second, its high-precision prediction results enable enterprises to optimize production scheduling and inventory management, avoiding overproduction or supply shortages so enterprises can adjust production capacity in advance and launch targeted marketing strategies. Third, the proposed framework offers a replicable solution for sales forecasting in industries with short development histories and limited data, aiding stakeholders in addressing market volatility through data-driven decisions.

7.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study also has limitations, which indicate directions for future research. First, the model optimization was insufficient, as the selection of hyperparameters like optimizers and activation functions was relatively basic, and the specific mechanism of the attention mechanism which captures key information requires further exploration. Future research can adopt grid search or Bayesian optimization to refine parameters and conduct ablation experiments to clarify each component’s contribution. Second, the indicator system can be expanded. Due to data availability constraints, this study mainly used monthly and quarterly data, failing to fully consider factors such as enterprise marketing strategies and consumer demographics. Extending the data time range and adding more micro-level indicators will help improve prediction accuracy. Third, the research was limited to China’s NEV market; the generalizability of the conclusions to regions with different policy environments and market maturity needs verification. Future cross-country comparative studies can explore the heterogeneous impact of influencing factors in different contexts.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Y.P.; validation, Y.P. and J.W.; formal analysis, J.W.; data curation, Y.P.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.P.; writing—review and editing, J.W.; project administration, Y.P.; funding acquisition, Y.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Projects of the 14th Five-Year Plan for Education Science in Jilin Province China (No. GH24173) and the 2026 Social Science Research Program of the Department of Education of Jilin Province, with the title “Construction of Jilin Ice-Snow Tourism Portrait and Development Strategy Research Based on Multimodal Data Mining”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Haoze Li and Yu Gao for their valuable contributions to the supplementary experiments of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Considering the availability and tractability of data, we select the quarterly sales data of new energy vehicles in China from July 2018 to December 2024 as the basic sample data, and the data comes from the Dolphin Magic Cube professional vehicle data platform. This platform provides one-stop data query and analysis services, including real-time data online query, in-depth data analysis, and multi-dimensional car sales ranking. The time span is long, so this platform is selected as the source of sales data. The platform takes new energy passenger vehicles as the statistical caliber. It includes data on sales, configuration, price, and other aspects of various vehicles and has a large statistical time span and high reference value. For the convenience of analysis, we combine the monthly sales volumes and conduct the analysis with one quarter as a time scale, which can take into account both micro and macro perspectives to explore market trends. Table A1 shows the specific quarterly sales data of new energy vehicles in China from the third quarter of 2018 to the fourth quarter of 2024.

Table A1.

Quarterly sales of new energy vehicles in China from 2018 to 2024.

Table A1.

Quarterly sales of new energy vehicles in China from 2018 to 2024.

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The first quarter | 220,149 | 106,316 | 432,717 | 1,010,583 | 1,233,872 | 1,749,048 | |

| The second quarter | 344,161 | 201,151 | 566,774 | 1,097,500 | 1,706,675 | 2,303,370 | |

| The third quarter | 184,301 | 141,727 | 300,326 | 784,300 | 1,467,201 | 1,997,438 | 3,005,597 |

| The fourth quarter | 465,817 | 215,001 | 535,030 | 1,143,663 | 1,693,701 | 2,385,676 | 3,716,736 |

We use the Tensorflow in Python to build a univariate sales prediction model. The quarterly historical sales data is taken as the dataset, and the dataset is divided into the training set and the test set. Considering the data volumes of the training set and the test set, in the data division of the new energy vehicle prediction model, the training set accounts for 85% and the test set accounts for 15%. We establish the GRU neural network, LSTM neural network, CNN neural network, and support vector regression machine. We set random seeds to ensure the reproducibility of the experiment. We make a prediction of the sales volume of new energy vehicles for a certain period as a reference. Considering the convenience of comparison with subsequent models, the parameters are kept as consistent as possible in the model design. The number of neurons in the new energy neural network prediction model is set to 4, the time step is set to 4 (four quarters), and the batch size is set to 1. The support vector machine model is established using the sklearn in Python, and the parameters were set to default. The parameters of the CNN prediction model are set as filters to 64, kernel size to 2, pool size to 2, and the activation function is the Relu function. The future prediction adopts direct output. In comparison to recursive and multi-output forecasting strategies, this approach offers two key advantages. First, it avoids the error accumulation that is prone to occur in recursive forecasting, as the direct strategy generates predictions exclusively based on reliable historical data rather than relying on intermediate predicted values that may propagate or amplify errors. Second, it is well-aligned with the practical demands of this study, which focuses on accurate short-term NEV sales forecasting to support industrial decision-making. In such scenarios, the priority lies in ensuring the reliability and interpretability of single-step predictions—rather than pursuing multi-period sequential outputs. After the model training and testing, we calculate the evaluation indicators of each model, respectively.

Five evaluation metrics are used to assess the performance of the models: Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), Symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error (SMAPE), and Mean Absolute Scaled Error (MASE).

The formula of RMSE is shown as Equation (A1):

In Equation (A1), n represents the number of samples, represents the true value, and represents the predicted value.

The formula of MAE is shown as Equation (A2):

The formula of MAPE is shown as Equation (A3):

The formula of SMAPE is shown as Equation (A4):

The formula of MASE is shown as Equation (A5):

In the above equations, n represents the number of samples, represents the true value, and represents the predicted value. MASE is more valuable in scenarios where cross-dataset or cross-time comparisons are required (e.g., evaluating the same model on different time periods or datasets with varying scales). However, the univariate baseline comparison in this study is confined to a single dataset (quarterly NEV sales from 2018 Q3 to 2024 Q4) with consistent units and scale. In such a closed comparison system, MASE fails to demonstrate its unique advantage of scale invariance, making its inclusion unnecessary. Notably, MASE is incorporated in the multivariate model evaluation (Section 6) to enable rigorous comparison between the proposed Attention-Seq2Seq model and traditional statistical models (e.g., SARIMA) with distinct underlying assumptions.

The indicator data of the new energy vehicle sales prediction model is shown in Table A2.

Table A2.

Indicator data of univariate prediction model for new energy vehicles.

Table A2.

Indicator data of univariate prediction model for new energy vehicles.

| Model | RMSE | MAE | MAPE | SMAPE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRU | 614,099.63 | 534,567.94 | 20.27% | 20.15% |

| LSTM | 853,922.08 | 674,150.28 | 21.81% | 25.27% |

| CNN | 847,003.70 | 761,006.87 | 26.67% | 31.30% |

| SVR | 1,942,586.60 | 1,796,243.31 | 63.93% | 95.61% |

In conclusion, the GRU neural network prediction model outperforms LSTM, CNN, and SVR in terms of RMSE, MAE, MAPE, and SMAPE indicators. According to the indicator data results, GRU neural network can be used as a basic prediction model.

References

- Huang, Y.; Unger, N.; Harper, K.; Heyes, C. Global climate and human health effects of the gasoline and diesel vehicle fleets. GeoHealth 2020, 4, e2019GH000240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, R. Eu’s ban on ice car sales from 2035 thrown into doubt after german demands. Platt’s Oilgram News 2023, 101, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, H.; Peng, S.; Li, L.; Zhu, Y. The role of governmental policy in game between traditional fuel and new energy vehicles. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2022, 169, 108292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoxi, Z.; Minglun, R.; Guangdong, W.; Jun, P.; Panos, M.P. Promoting new energy vehicles consumption: The effect of implementing carbon regulation on automobile industry in China. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 135, 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, R.; Lin, B. Are people willing to support the construction of charging facilities in China? Energy Policy 2020, 143, 111604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EVTank. Available online: http://www.evtank.cn/DownloadDetail.aspx?ID=546 (accessed on 16 January 2024).

- EVTank. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1821295724169209532&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Xinhua News Agency. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/lianbo/bumen/202501/content_7000306.htm (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Xiong, Y.Q.; Cheng, Q.; Liao, M.Y. The impact of new energy vehicle information sources on mass consumers’ purchase intentions: An investigation in China. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2024, 36, 1337–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decarlo, T.; Roy, T.; Barone, M. How sales manager experience and historical data trends affect decision making. Eur. J. Mark. 2015, 49, 1484–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D. Chinese automobile demand prediction based on ARIMA model. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Informatics, Shanghai, China, 15–17 October 2011; pp. 2197–2201. [Google Scholar]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandriah, K.K.; Naraganahalli, R.V. RNN/LSTM with modified Adam optimizer in deep learning approach for automobile spare parts demand forecasting. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 26145–26159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Singh, V.; Goel, R. Strategic forecasting for electric vehicle sales: A cutting edge holistic model leveraging key factors and machine learning technique. Transp. Dev. Econ. 2024, 10, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Boser, B.; Denker, J.S.; Henderson, D.; Howard, R.E.; Hubbard, W.; Jackel, L.D. Backpropagation applied to handwritten zip code recognition. Neural Comput. 1989, 1, 541–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaremba, W.; Sutskever, I.; Vinyals, O. Recurrent neural network regularization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.2329. [Google Scholar]

- Marc, N. A note on long-run automobile demand. J. Mark. 1957, 22, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick, S.M. Market price and income elasticities of new vehicle demands. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1996, 78, 543–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Wang, L.; Huang, K. The forecasting model of automobile sales volume based on times series. Mech. Eng. 2013, 05, 8–10. [Google Scholar]