Abstract

At the intersection of the circular economy and artificial intelligence (AI), high-value secondhand trading faces a “triple decision dilemma” of cognitive overload, trust risk, and emotional attachment. To address the limits of traditional human-centered theories, this study develops and empirically tests a novel framework of Algorithmic Empowerment. Drawing on data from 1396 users of Chinese secondhand luxury platforms and analyzed using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), the findings reveal that users’ empowerment perception arises from three dimensions—Algorithmic Connectivity (AC), Human–Agent Symbiotic Trust (HAST), and Algorithmic Value Alignment (AVA). This perceived empowerment affects participation willingness through two parallel pathways: the social pathway, where algorithmic curation shapes social norms and recognition, and the cognitive pathway, where AI enhances decision fluency and reduces cognitive friction. The results confirm the dual mediating effects of these mechanisms. This study advances understanding of human–AI collaboration in sustainable consumption by conceptualizing empowerment as the bridge linking algorithmic functions to user engagement, and provides actionable implications for designing AI systems that both enhance efficiency and foster user trust and identification.

1. Introduction

As circular economy principles converge with the era of artificial intelligence (AI), the traditional linear consumption model of “acquire-use-discard” is undergoing profound deconstruction [1]. Particularly within the resource-intensive fashion industry, the recirculation of idle goods has become a critical driver of sustainable development [2,3]. China’s secondhand luxury goods market is experiencing explosive growth, reaching a market size of 34.6 billion yuan in 2023 with a compound annual growth rate of 21.06%. However, a notable paradox exists: the circulation scale of idle luxury apparel (annual transaction value of approximately RMB 6.93 billion) falls significantly short of that for bags and leather goods (annual transaction value of approximately RMB 19.48 billion) [4]. This phenomenon stems from the inherent triple decision-making dilemma of traditional C2C models when dealing with high-value, non-standardized goods: high cognitive load (professional barriers in authenticity verification and value assessment), high trust risk (deep mistrust between buyers and sellers), and strong emotional attachment (emotional resistance to disposal decisions) [5,6].

However, advanced AI technologies, exemplified by AI agents, are fundamentally reshaping this transactional ecosystem. Today’s AI systems—such as ChatGPT 3.0 for advice, Stable Diffusion for fashion visualization, and luxury-item authentication models commonly seen on platforms like Vestiaire Collective—are no longer just tools. AI has evolved beyond being merely a passive “tool” for efficiency enhancement into a proactive “decision partner” and “social actor” capable of offering advice, facilitating communication, and even managing transactions [7,8]. It is deeply embedded throughout the entire process of information discovery, trust building, and norm formation, constructing a novel socio-technical system where humans and algorithms collaborate in decision-making. Within this new paradigm of human–machine collaboration, a core scientific question emerges: How do interactions between users and AI agents in high-risk decision-making scenarios, where AI is deeply involved, jointly empower individuals and ultimately drive their participation in high-value circular business?

Previous research has largely relied on Social Capital Theory to examine how network connections, interpersonal trust, and shared cognition among users influence consumption behavior [9]. However, existing studies mostly assume human-to-human interaction and do not fully address what happens when AI becomes a central social actor [10]. For example, users now often rely on AI pricing models instead of friends’ advice, and they trust authentication algorithms more than seller reviews. As decision-making shifts from “I trust people I know” to “I trust systems that prove reliable”, a new theoretical perspective is needed to explain human–AI interaction in circular business settings.

To address this theoretical gap, this paper proposes and tests a novel “Algorithmic Empowerment” theoretical framework, building upon traditional social capital theory. We contend that AI’s core function for users extends beyond mere information provision. Instead, it generates a profound sense of empowerment by endowing users with previously unattainable capabilities, confidence, and value recognition. This empowerment manifests across three dimensions: Structural Algorithmic Connectivity (AC)—the perceived ability of algorithms to efficiently link value information with communities; relational human-agent symbiotic trust (HAST), which involves establishing anthropomorphic trust in AI agents that transcends instrumental rationality [11]; and cognitive algorithmic value alignment (AVA), where the principles advocated by perceptual algorithms resonate strongly with one’s own values [9]. We further propose that these empowering perception channels influence behavioral intent through two parallel human–machine collaborative decision mechanisms: first, shaping users’ social identity through Algorithm-Curated Social Norms (ACSN); second, reducing users’ cognitive execution costs via AI-Driven Decision Fluency (ADDF).

This study empirically validates the framework using data from users of China’s secondhand luxury clothing market. It contributes by offering a new psychological perspective on sustainable consumption in the digital era, demonstrating the dual mechanisms of AI empowerment, and provides clear, actionable practical insights for how secondhand online trading platforms can design and govern more empowering AI systems. Subsequent sections elaborate as follows: Section 2 constructs the theoretical framework and hypotheses; Section 3 details the research methodology; Section 4 reports empirical findings; Section 5 conducts an in-depth discussion; and Section 6 concludes with a summary and future outlook.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. User Participation in Circular Commerce: Decision Dilemmas in High-Value Categories

Driven by global sustainability agendas, the circular economy has evolved from a niche concept into a core paradigm reshaping global production and consumption patterns. This paradigm advocates minimizing resource waste through design, reuse, repair, and recycling, transitioning from the traditional linear “take-make-dispose” model to a closed-loop system [1,12]. Among all industries, fashion and textiles stand as critical sectors for circular economy transformation due to their massive resource consumption, environmental footprint, and short product lifecycles [2]. Against this backdrop, business models represented by online secondhand trading offer a crucial channel for extending product lifecycles and reducing waste. Notably, the luxury sector—once hesitant toward secondhand markets due to its emphasis on exclusivity and the “brand-new” experience—has increasingly embraced circular models in recent years. This shift is viewed as a strategic opportunity to enhance brand sustainability credentials and attract new generations of consumers [13].

However, when shifting from industry-level progress to individual user behavior, especially in the secondhand luxury apparel market, users still face a three-fold decision dilemma that prevents idle luxury clothing from circulating efficiently.

First, users face high cognitive load. Unlike standardized, low-value goods, disposing of luxury apparel is an information-intensive task requiring specialized knowledge. Users must navigate multiple judgment points—authenticity verification, condition assessment, market trend analysis, and final pricing—which often exceed the knowledge base of average consumers [14]. According to cognitive load theory, when information processing exceeds working memory capacity, cognitive systems become overwhelmed, leading to diminished decision quality or avoidance [15]. For luxury sellers, mispricing can result in thousands of dollars in financial loss. This potential negative outcome further intensifies psychological pressure and decision complexity.

Second, users face high trust risk. Online C2C platforms inherently involve information asymmetry, and the high-value nature of luxury goods magnifies this risk exponentially. Trust is defined as the psychological state of willingness to bear risks arising from others’ actions in uncertain environments [16]. In secondhand luxury transactions, sellers not only worry about fraud risks from potential buyers (such as malicious returns or counterfeit claims) but also face uncertainties inherent in platform mechanisms (e.g., dispute resolution, fund security) [17]. This pervasive distrust forms a formidable barrier to transactions, leading many users to prefer leaving items idle rather than risking potential complications during the transaction process [18].

Finally, users must overcome obstacles stemming from strong emotional attachment. Luxury goods often symbolize self-identity, memories, or personal milestones, fostering deep emotional bonds [19]. Consumer behavior research indicates that the greater an individual’s emotional attachment to an item, the lower their willingness to dispose of it. This is because the disposal process is perceived as a separation from a “self-extension,” triggering negative emotions [20,21]. Consequently, selling a commemorative luxury garment is not merely an economic decision for users but an emotional struggle requiring overcoming, often leading to decision inertia [18].

In summary, this triple dilemma—comprising high cognitive load, high trust risk, and strong emotional attachment—significantly hinders user engagement in high-value circular fashion. Traditional solutions focus mostly on improving information access, yet do not fully address users’ psychological burdens. In contrast, modern AI tools—such as ChatGPT for pricing suggestions, computer-vision authentication models for luxury goods, and AI agents that guide resale decisions—can directly help users verify items, reduce risk, and emotionally support decisions [7,8]. AI is no longer merely an efficiency tool but an active assistant and decision partner, helping users evaluate, trust, and act. This evolution calls for new theoretical perspectives to explain how human-AI collaboration empowers users in circular commerce contexts.

2.2. From Social Capital to Algorithmic Empowerment: A Theoretical Paradigm Shift

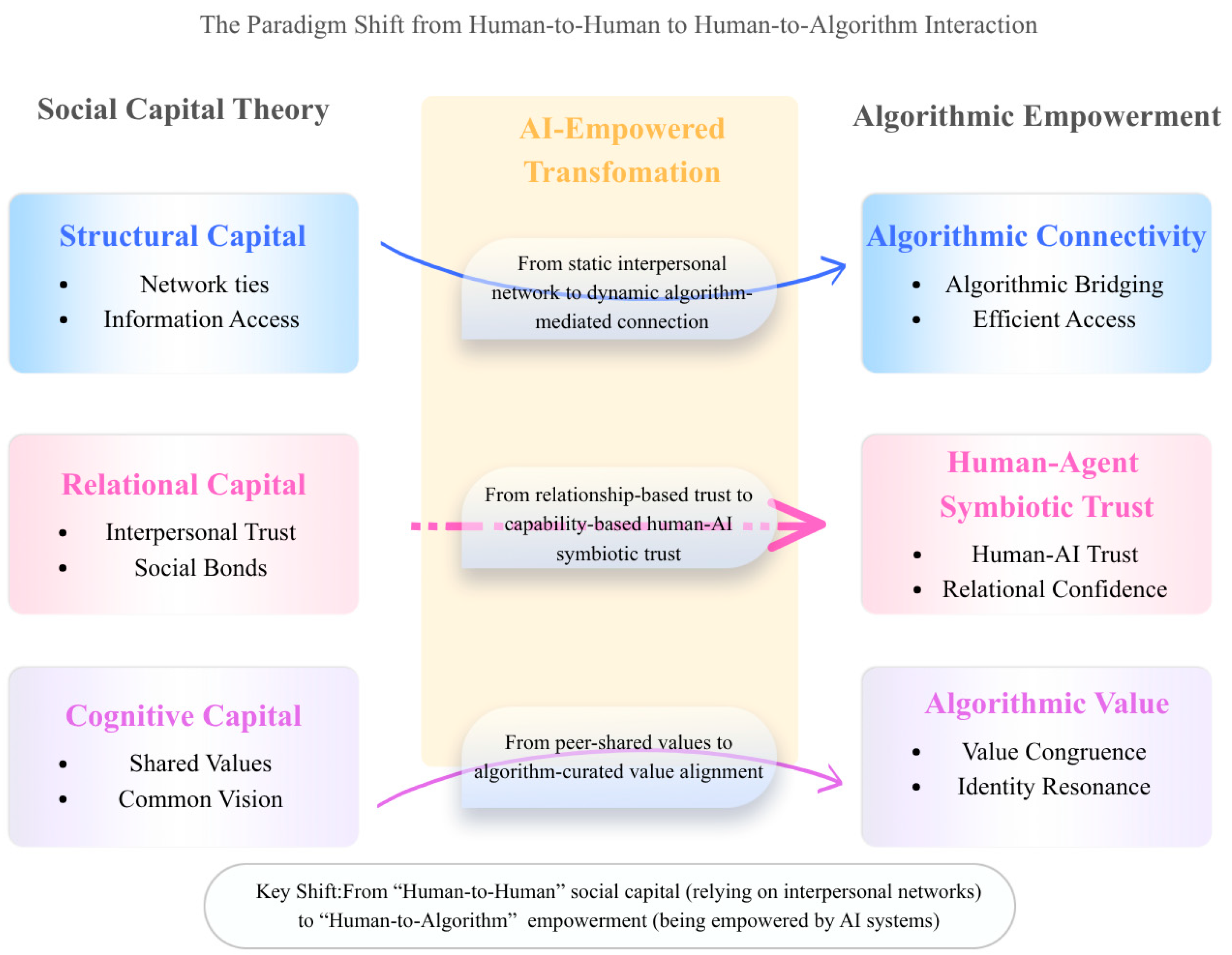

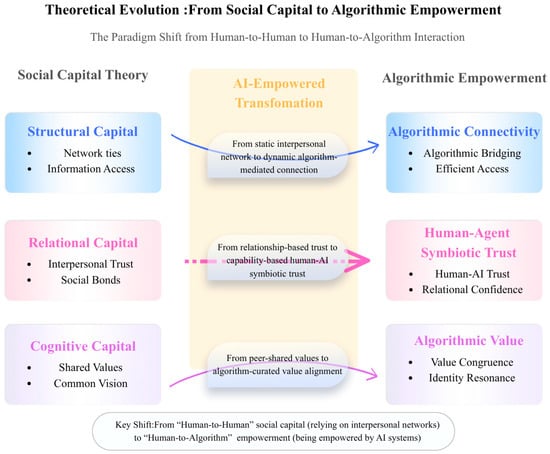

Social capital theory, originating in sociology, was pioneered by Nahapiet & Ghoshal (1998) with a three-dimensional framework encompassing structural, relational, and cognitive dimensions [22]. In digital contexts, structural capital refers to the patterns and density of users’ network connections within communities; relational capital focuses on the strength of bonds maintained through trust, reciprocity, and emotional ties; while cognitive capital emphasizes shared language, narratives, and values [9]. This theory powerfully explains why users in online communities are willing to share knowledge and collaborate, and how these social resources ultimately translate into commercial intent [23]. However, this theory was originally designed for human-to-human relationships, and its explanatory power weakens as artificial intelligence becomes deeply embedded in online interactions.

From a social capital perspective, value has always stemmed from interpersonal connections. Yet contemporary AI systems, particularly intelligent agents, have evolved into proactive social actors capable of learning, reasoning, communicating, and autonomously executing tasks. This raises a critical question: when users begin trusting AI valuation bots more than familiar peers, and when social norms shift from friends’ posts to algorithmic feeds and platform recommendations, can a theory grounded purely in human connections still explain participation behavior? We argue that treating AI merely as a supplementary “enhancer” of social capital is insufficient; AI has become a central actor shaping users’ confidence, decisions, and perceptions of trust.

To this end, this study integrates social capital theory with empowerment theory to form a novel theoretical framework. Empowerment theory emphasizes the dynamic process by which individuals enhance their motivation and sense of control through acquiring resources, skills, and support [24]. Spreitzer (1995) further operationalized this into four dimensions: sense of competence, sense of significance, sense of self-determination, and sense of influence [25]. This study contextualizes these dimensions within human–machine interaction, arguing that advanced AI systems are no longer merely supplementary factors to social capital. Instead, they function as new empowering agents, enhancing users’ sense of competence, significance, and autonomy through their unique capabilities. For instance, AI’s automated valuation and defect detection functions elevate users’ sense of competence [26]; recommendations from sustainable fashion and eco-conscious communities imbue transactions with meaning beyond economic exchange; while diverse, personalized disposal pathway suggestions bolster users’ sense of self-determination.

Within this integrated framework, we propose the core independent variable—Perceived AI Empowerment—which refers to the heightened sense of capability, control, and value realization users experience when engaging with AI-empowered platforms. Figure 1 visualizes this theoretical evolution. This macro-level construct manifests across three dimensions:

Figure 1.

Theoretical Evolution from Social Capital to Algorithmic Empowerment.

Structural Algorithmic Connectivity: Users perceive the platform’s algorithms as capable of efficiently and accurately connecting them to relevant information, opportunities, and users, thereby building a valuable, personalized transactional ecosystem. This reflects AI’s “structural empowerment” in breaking down information barriers and creating market opportunities.

Human-Agent Symbiotic Trust: Drawing from recent advancements in human–machine interaction [27], we define this as users’ comprehensive trust in the capabilities, integrity, and benevolence of platform AI agents (e.g., intelligent customer service, pricing bots, custodial assistants). This trust transcends mere tool dependency, enabling users to perceive AI as reliable, human-like decision-making partners—thus achieving “relational empowerment.”

Cognitive Algorithmic Value Alignment: The experience where users perceive that the content recommended, the values promoted (e.g., circular fashion, green consumption), and the community atmosphere fostered by platform algorithms align closely and resonate with their personal values. It embodies the “cognitive empowerment” of AI in helping users achieve self-identity and value expression.

2.3. Human–Machine Collaborative Decision-Making Mechanism

2.3.1. Algorithm-Curated Social Norms (ACSN)

Algorithm-Curated Social Norms (ACSN) are defined as the mainstream behaviors perceived by users as widely accepted and encouraged within specific communities through algorithmic personalized recommendations, content ranking, and community building.

This concept modernizes a classic idea from the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). TPB posits that subjective norms—an individual’s perceived social pressure from significant others to perform or refrain from performing a behavior—are a core determinant of behavioral intention [28]. Social norms in algorithmic curation represent the contemporary manifestation and evolution of subjective norms within the digital ecosystem. More significantly, this construct integrates insights from Algorithmic Curation & Gatekeeping Theory. In traditional societies, norms formed through interpersonal interactions and mass media dissemination. While norms traditionally formed through interpersonal interactions and mass media, algorithms on modern digital platforms have largely replaced these channels. They now act as powerful gatekeepers and curators that shape social realities and normative perceptions [29]. The “majority behavior” or “mainstream views” users perceive in their information streams are not unbiased reflections of objective reality, but rather outcomes selected, ranked, and amplified by algorithms according to specific objectives [30].

2.3.2. AI-Driven Decision Fluency (ADDF)

We define AI-Driven Decision Fluency as the subjective experience where users perceive reduced cognitive effort in completing the complex decision-making process of disposing idle luxury goods with AI system assistance, rendering the decision-making process effortless, smooth, and unimpeded [18]. This construct’s theoretical foundation is equally rooted in psychology and human–computer interaction.

First, ADDF builds upon Processing Fluency Theory. This theory posits that an individual’s subjective sense of ease when processing information or executing tasks serves as a critical metacognitive cue that enhances positive emotions and behavioral tendencies [31]. In AI-assisted complex decision-making scenarios, processing fluency manifests as users perceiving AI-provided information and solutions as “easy to understand and adopt,” thereby increasing their propensity to act [32].

Second, the formation of ADDF relies on cognitive offloading. Cognitive science research indicates humans tend to leverage external tools to share cognitive tasks, conserving limited mental resources [33]. In platform scenarios, AI reduces users’ cognitive load during information search, evaluation, and execution through automated valuation, copywriting generation, buyer matching, and process guidance [34]. This offloading not only simplifies tasks but also enhances the fluency and consistency of decision-making.

2.4. Impact of Algorithmic Empowerment on Circular Commerce Participation Intent

2.4.1. Algorithmic Connectivity (AC)

We examine the structural dimension of algorithmic empowerment—Algorithmic Connectivity (AC)—defined as users’ perception of a platform algorithm’s ability to efficiently and accurately connect them to valuable information, opportunities, and communities. This construct is grounded in two core theoretical foundations. First, Social Network Theory emphasizes that actors occupying “structural holes” gain advantages by serving as information bridges [35]. Within digital platforms, algorithms function as dynamic “network architects,” dynamically “building bridges” through personalized recommendations. These connections link users to potential transaction partners, expert groups, and niche communities, providing information advantages without relying on accumulated social capital. Second, Technology Affordance Theory posits that a technology’s value lies not in its physical attributes but in the possibilities it affords users to achieve their goals [36]. From this perspective, algorithmic connectivity represents a core technological affordance. It empowers users to effortlessly access market intelligence, match potential buyers, and enter relevant communities, thereby achieving direct structural empowerment. Based on this logic, we contend that algorithmic connectivity not only directly enhances user participation willingness but also exerts indirect effects by shaping social norms and increasing decision-making fluency.

On one hand, high levels of algorithmic connectivity reduce user uncertainty regarding the “sell-ability” of items in high-value circular commerce. When algorithms continuously present successful transaction cases and potential buyer demand, users experience significantly enhanced information accessibility and resource availability. This boosts self-efficacy, directly driving engagement intent. Therefore, we propose:

H1a:

Algorithmic connectivity positively influences the user’s intention to engage in high-value circular commerce.

On the other hand, algorithmic connectivity also serves as a crucial antecedent for social norm formation. Algorithms connect not only “people” but also “content” and “discourse.” When recommendation mechanisms embed users within active and relevant communities (e.g., vintage fashion styling or sustainable fashion), users are continuously exposed to the mainstream behaviors and values advocated by the group. According to social comparison theory [37], individuals assess their own appropriateness by observing others’ behaviors. The curatorial effect of algorithms enhances the visibility of specific content [38], intensifying users’ perception that certain disposal behaviors constitute accepted and encouraged norms. Thus, we hypothesize:

H1b:

Algorithmic connectivity positively influences the user’s perception of algorithm-curated social norms.

Furthermore, algorithmic connectivity enhances users’ decision-making fluency. Disposition decisions for high-value categories are often complex and time-consuming. Efficient connectivity ensures users receive immediate, contextually relevant informational support at critical junctures: successful case studies when hesitating to sell, real-time market data during pricing, and copywriting templates when drafting descriptions. This instant support model effectively reduces users’ cognitive load by facilitating cognitive offloading [15,33], thereby smoothing the entire decision-making process. Thus, we propose:

H1c:

Algorithmic connectivity positively influences the user’s perception of AI-driven decision fluency.

2.4.2. Human-Agent Symbiotic Trust (HAST)

We explore the second dimension of algorithmic empowerment—the relational dimension: Human-Agent Symbiotic Trust (HAST). This is defined as the user’s comprehensive trust in the capabilities, integrity, and benevolence of platform AI agents (e.g., intelligent customer service, pricing bots, custodial assistants), thereby perceiving them as reliable, personified decision-making partners. This construct is grounded in two major theoretical foundations from human–computer interaction.

Research on human–machine trust shows that user trust in automated systems is multidimensional. Lee & See (2004) emphasized that moderate trust is a prerequisite for efficient human–machine collaboration [39]. Subsequent studies identified three core elements constituting this trust: competence, benevolence, and integrity [27,40]. In high-risk, high-value luxury asset transactions, users must not only believe the AI “can do it right” but also confirm it “has my best interests at heart” and ensure its actions are “fair.” Additionally, Parasocial Relationship Theory explains the emotional bonds users form with AI. Originally proposed by Horton & Wohl (1956) to describe one-sided intimate bonds between audiences and media characters [41], this theory is now widely applied to user interactions with virtual idols, social media influencers, and anthropomorphized AI agents [42,43]. When AI exhibits human-like communication styles and personalized care, users gradually perceive it as a warm social companion rather than a cold tool. This development of a pseudo-social relationship lays the emotional foundation for symbiotic trust [11]. Based on this, we argue that human-agent symbiotic trust exerts multiple influences on user decisions and behaviors.

First, trust is a critical mechanism in risk decision-making. When disposing of luxury goods, users face significant economic and psychological risks. Trust reduces this perceived risk and increases willingness to transact online [44]. When users develop high levels of symbiotic trust in AI, they are more inclined to delegate complex, high-risk tasks—such as valuation, communicating with unfamiliar buyers, and dispute resolution—to AI, thereby alleviating psychological burdens and stimulating participation intent. Therefore:

H2a:

Human-agent symbiotic trust positively influences the user’s intention to engage in high-value circular commerce.

Second, symbiotic trust enhances users’ acceptance of algorithm-curated social norms. Persuasion theory emphasizes that source credibility is central to determining the persuasiveness of information. Users who highly trust AI are more likely to perceive its recommendations as well-intentioned and valuable “insider consensus” rather than commercial manipulation or noise. Consequently, the sustainable fashion principles advocated by AI are more readily internalized as social norms users adhere to:

H2b:

Human-agent symbiotic trust positively influences the user’s perception of algorithm-curated social norms.

Finally, symbiotic trust enhances decision-making fluency. Fluency depends not only on streamlined processes but also on the confidence that comes from trust. Users who fully trust AI’s competence and benevolence are less likely to engage in critical scrutiny or repeated verification when accepting its pricing suggestions or auto-generated descriptions. Research indicates that reasonable trust calibration reduces unnecessary monitoring behaviors, thereby enhancing human–machine collaboration efficiency [45]. This willingness to rely on the AI allows users to move through decision-making stages more seamlessly, significantly improving their subjective experience of decision fluency:

H2c:

Human-agent symbiotic trust positively influences the user’s perception of AI-driven decision fluency.

2.4.3. Algorithmic Value Alignment (AVA)

The third dimension of algorithmic empowerment is the cognitive dimension—Algorithmic Value Alignment (AVA). We define it as: users perceiving that the content recommended by platform algorithms, the principles advocated (e.g., circular fashion, green consumption), and the community atmosphere shaped align highly with their personal values, thereby generating an experience of identification and resonance. This construct is theoretically grounded in “fit” research from consumer and organizational behavior.

First, AVA aligns with Self-Congruity Theory. This theory suggests that consumer decisions are based not only on product functionality but also on whether a brand or media image matches their actual self, ideal self, and core values [46]. Similarly, in digital platforms, users assess the fit between the “algorithmic image” and their personal values. When algorithmic recommendations consistently resonate with a user’s life philosophy, it fosters a sense of identification and belonging.

Second, AVA connects to Person-Environment Fit Theory, specifically “Person-Organization Value Fit” (P-O fit). Research indicates that when employees’ values align with organizational values, they exhibit higher satisfaction and commitment [47]. Similarly, in a platform context, the values promoted by its algorithms act like an “organizational culture.”

Based on this, AVA plays a crucial role in stimulating users’ intrinsic identification and meaning-making. Participation in high-value circular commerce often transcends economic motives, becoming an expression of personal values. When algorithms link disposal behaviors to value narratives around environmentalism, fashion, or rational consumption, these actions gain deeper meaning. This sense of meaning can drive user action [48].

Therefore, we propose:

H3a:

Algorithmic value alignment positively influences the user’s intention to engage in high-value circular commerce.

Additionally, AVA influences the level of internalization of algorithmic curation social norms among users. According to social influence theory [49], individual acceptance of norms progresses from compliance to identification to internalization. When algorithm-curated community norms align with users’ core values, participation shifts from conformity to “I believe this is right.” This value-based perception of norms proves more stable and enduring [50].

H3b:

Algorithmic value alignment positively influences the user’s perception of algorithm-curated social norms.

Finally, AVA mitigates value conflicts in disposal decisions, thereby enhancing decision fluency. Luxury goods disposal often involves trade-offs between economic and environmental considerations. When algorithmic recommendations align with user values, they reduce inner conflict and foster cognitive consonance, lowering psychological resistance and improving the decision-making experience [51].

H3c:

Algorithmic value alignment positively influences the user’s perception of AI-driven decision fluency.

2.5. Mediating Roles in Human–Machine Collaborative Decision-Making Mechanisms

2.5.1. Social Mediation Pathway

The influence of algorithmic empowerment does not act directly or in isolation on user intent but is mediated through a series of human–machine collaborative decision mechanisms. The first mediating mechanism we propose is the social pathway—the social norms of algorithmic curation.

Disposing of luxury goods, particularly apparel, is an act with high social visibility that serves as a signal of identity [52]. It concerns not only the items themselves but also the image individuals wish to project—whether savvy, fashionable, or environmentally conscious. When users consistently perceive, through algorithmic curation, that participating in circular fashion is a socially valued, positive norm within their community, they develop strong motivation to adhere to this norm. This is driven by the desire to gain social approval and avoid social exclusion [53]. The need for belonging and a positive social image are fundamental drivers that lead individuals to adopt behaviors consistent with group norms [54]. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4:

The perception of algorithm-curated social norms positively influences the user’s intention to engage in high-value circular commerce.

Following this logic, we argue that algorithm-curated social norms play a crucial mediating role in our model. Perceived AI empowerment (through its three dimensions) does not translate directly into behavioral intent. A core pathway of its influence is by systematically shaping users’ perceptions of what constitutes “desirable behavior,” thereby guiding their choices. The three dimensions of algorithmic empowerment collectively shape users’ social reality, making them more receptive to, and likely to internalize, norms that encourage circular commerce participation. Specifically:

Integrating H1b (Algorithmic Connectivity Enhances Norm Perception) and H4, we contend that algorithms efficiently connect users to relevant communities, exposing them to curated norms that drive their behavior. Therefore, we propose:

H5a:

Algorithm-curated social norms mediate the positive relationship between algorithmic connectivity and the user’s intention to engage in high-value circular commerce.

Combining H2b (Human-Agent Trust Enhances Norm Acceptance) and H4, we propose that users’ trust in AI agents increases their willingness to accept algorithmically recommended community norms and translate them into action. Thus, we propose:

H5b:

Algorithm-curated social norms mediate the positive relationship between human-agent symbiotic trust and the user’s intention to engage in high-value circular commerce.

Combining H3b (Value Alignment Facilitates Norm Internalization) and H4, we propose that when curated norms align with users’ values, they internalize these norms more deeply, generating stronger behavioral motivation. Thus, we propose:

H5c:

Algorithm-curated social norms mediate the positive relationship between algorithmic value alignment and the user’s intention to engage in high-value circular commerce.

2.5.2. Cognitive Mediation Pathway

Parallel to the social pathway, we propose that algorithmic empowerment also operates through a critical cognitive pathway: enhancing AI-Driven Decision Fluency (ADDF). When making disposal decisions for high-value categories, users often face significant action barriers due to the inherent complexity of such choices (see Section 2.1). A key insight from behavioral economics and the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) is that perceived ease of use—the degree to which a system is seen as “effortless”—is a major predictor of technology adoption and behavioral intent [55,56]. When users perceive AI as making complex processes “simple and smooth,” their expected effort significantly decreases, thereby reducing psychological resistance to action [11,57]. Research indicates that reducing the psychological and cognitive costs of action is a crucial mechanism for decreasing procrastination and driving actual behavior [58,59]. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H6:

The perception of AI-driven decision fluency positively influences the user’s intention to engage in high-value circular commerce.

In summary, AI-driven decision fluency constitutes another critical mediating pathway within our theoretical framework. Perceived AI empowerment works not only by shaping social identity but also through an equally important cognitive route—by significantly reducing the complexity and cognitive cost of decision-making. This clears the final psychological barrier to action by creating a subjective sense that “I can easily do this.” We contend that the three dimensions of algorithmic empowerment collectively foster this experience of ease, thereby enhancing users’ willingness to participate. Specifically:

Integrating H1c and H5, we argue that the instant informational support provided by algorithms reduces cognitive effort, making the decision process feel smoother and thus promoting behavior [60]. Therefore, we propose:

H7a:

AI-driven decision fluency mediates the positive relationship between algorithmic connectivity and the user’s intention to engage in high-value circular commerce.

Combining H2c and H5, we argue that users’ trust in AI agents reduces their need for personal deliberation and verification, allowing them to follow AI guidance with less hesitation. This heightened sense of fluency then translates into action. Thus, we propose:

H7b:

AI-driven decision fluency mediates the positive relationship between human-agent symbiotic trust and the user’s intention to engage in high-value circular commerce.

Combining H3c and H5, we propose that when AI recommendations align with users’ values, their internal decision conflict is reduced. This promotes a state of cognitive harmony and fluency, thereby motivating behavior. Thus, we propose:

H7c:

AI-driven decision fluency mediates the positive relationship between algorithmic value alignment and the user’s intention to engage in high-value circular commerce.

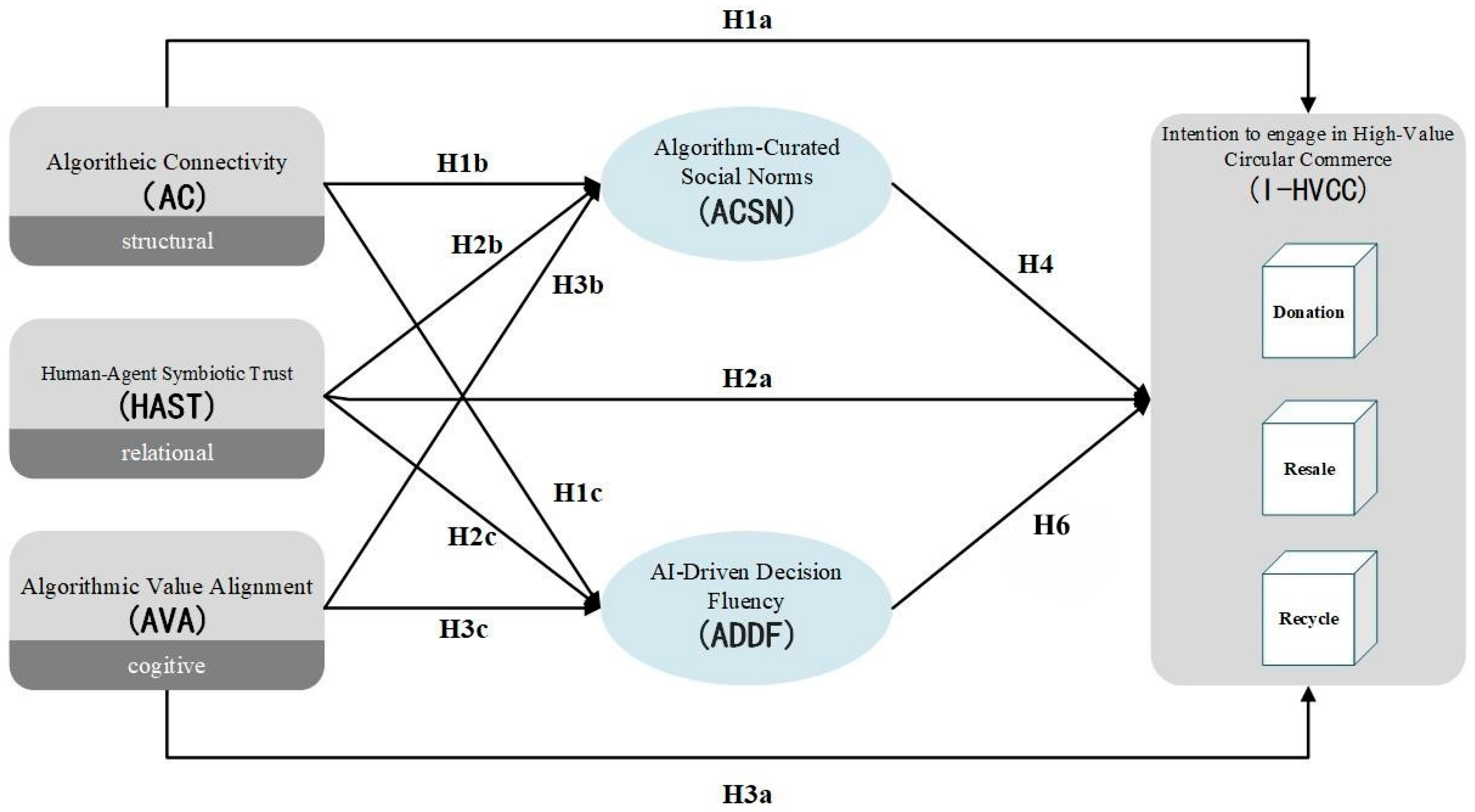

2.6. Theoretical Model

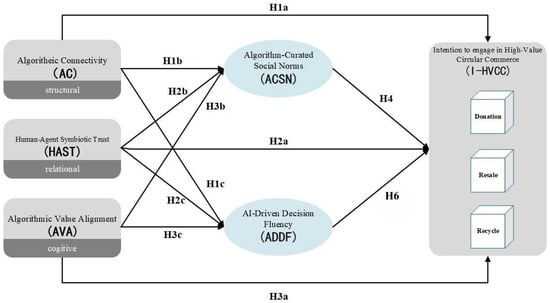

In summary, this study proposes a comprehensive framework centered on Perceived AI Empowerment, integrating Empowerment Theory [61] and Social Capital Theory [22,62,63]. We contend that users’ empowerment experiences on AI platforms stem from three resource categories: Algorithmic Connectivity (AC) embodies structural resource acquisition, Human-Algorithm Symbiotic Trust (HAST) reflects relational resource quality, and Algorithmic Value Alignment (AVA) signifies cognitive and value resource integration. These dimensions exert their effects through two key pathways: a social pathway grounded in social capital logic (shaping algorithmic curation norms to fulfill identity and belonging needs) and a cognitive pathway rooted in empowerment logic (enhancing AI-driven decision-making fluency while reducing cognitive load and action barriers). Their synergistic interaction jointly drives user’s intention to engage in high-value circular commerce (I-HVCC). Based on this, we constructed the research model shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Research Model.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This study employs a cross-sectional survey to collect empirical data, testing the “algorithmic empowerment” theoretical framework proposed in Section 2. Specifically, it aims to validate the causal pathways between the three dimensions of algorithmic empowerment (AC, HAST, AVA), the two human–machine synergy mechanisms (ACSN, ADDF), and users’ intention to engage in high-value circular commerce (I-HVCC) using large-scale Chinese user data.

This research design is grounded in two considerations: First, core constructs such as “AI empowerment perception,” “human–machine symbiotic trust,” and “behavioral intention” are latent variables, and surveys represent a well-established method for measuring such psychological constructs [64]. Second, online surveys enable rapid access to extensive samples, ensuring both external validity of findings and sufficient statistical power to test multiple relationships within the model [65].

3.2. Development and Adaptation of Measurement Tools

Given the strong contextual innovativeness of core constructs like “algorithmic empowerment,” this study adopted a scale adaptation strategy during instrument development. This involved systematically modifying established scales from authoritative literature to align with the research context, ensuring content validity and construct validity. For instance, items measuring algorithmic connectedness (AC) were adapted from a classic scale reflecting network connectivity and information access in social capital and online community participation research [9]. Human-agent symbiotic trust (HAST) was adapted from Mayer et al. organizational trust model and its extensions in human–computer interaction and e-commerce contexts (e.g., McKnight et al.; Glikson & Woolley) [27,44,66]; while the Algorithmic Value Alignment (AVA) scale drew from established measures of individual-organizational value fit [67]. During adaptation, we systematically replaced core terms in the original scales (e.g., “organization,” “colleagues,” “brand”) with terminology highly relevant to AI-enabled secondhand trading platforms (e.g., “AI recommendations,” “intelligent assistants”) to ensure measurement content aligned with the research context.

To ensure validity and reliability of the adapted scales, we implemented two critical procedures. First, three experts in information systems, consumer behavior, and human–computer interaction independently reviewed the preliminary item pool, providing feedback on content and surface validity. Multiple rounds of revisions followed to ensure precise and clear wording. Second, prior to formal research, we conducted a pretest with 50 eligible participants. This involved calculating Cronbach’s α to assess the scale’s preliminary internal consistency reliability and gathering feedback on semantic clarity and comprehensibility. Based on the results, we fine-tuned individual items. All finalized measurement items employed a 7-point Likert scale ranging from “1 = Strongly Disagree” to “7 = Strongly Agree.” The complete list of questionnaire measurement items is detailed in Appendix A.

3.3. Sample and Data Collection

The target population for this study was precisely defined as: “Consumers residing in first- and second-tier cities in China who confirmed owning idle luxury brand clothing and had experience using mainstream secondhand trading platforms (e.g., Xianyu) within the past year.” This group constitutes both the core participants in China’s secondhand luxury market and the cohort most familiar with and likely to adopt platform AI features, thereby providing representative data for model validation in this research.

The survey was conducted from June to July 2024 via the Chinese data collection platform Credamo, which boasts over 3 million users spanning diverse social groups. Widely used across disciplines and recognized by international journals [68], Credamo ensured broad representativeness. To ensure data quality, multiple control measures were implemented: (1) Participants received a small monetary reward (4–6 RMB) upon completing the questionnaire to enhance response rates; (2) Attention checks were incorporated to screen out careless respondents; (3) Questionnaires with missing key responses, highly repetitive answers, or completion times under 3 min were excluded; (4) Questionnaires with illogical responses or clearly unreasonable content were discarded. The survey was targeted at urban areas in Jiangsu Province, Zhejiang Province, and Shanghai. A total of 2056 questionnaires were collected, and after excluding 560 invalid responses, 1396 valid questionnaires were obtained. The valid response rate was 67.9%, meeting academic research standards.

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of respondents. Females constituted 52.6% and males 47.4%, indicating a relatively balanced gender distribution. The age structure revealed a predominantly young sample, with 74.9% of respondents aged 18–35, further highlighting the high acceptance of green consumption concepts among China’s youth and greater maturity in online disposal of secondhand luxury goods [69,70]. Educational attainment at the bachelor’s degree level or above reached 91.5%, while monthly spending exceeding ¥5000 accounted for 60.1%. These findings align with the typical profile of secondhand luxury consumers and online academic research platforms, indicating the sample’s strong representativeness.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of Sample Characteristics.

4. Data Analysis and Model Evaluation

Data analysis employed partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using SmartPLS 3.0. This method is suitable for theory development and prediction-oriented research [71], robustly handles non-normally distributed data, and offers advantages for complex models involving multiple mediating effects [72]. Analysis followed a “two-step approach”: First, the reliability and validity of the measurement model were assessed, including internal consistency (α and CR), convergent validity (loadings and AVE), and discriminant validity (Fornell–Larcker criteria and HTMT). Subsequently, structural model paths were tested using Bootstrapping (5000 resamples) to evaluate path coefficients and the significance of mediating effects, while reporting the explanatory power () of endogenous variables.

4.1. Validity and Reliability Analysis of the Measurement Model

This study employed SEM to assess the reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of the measurement model. For reliability, following Hair et al. (2011), Cronbach’s α and composite reliability (CR) must exceed 0.7 to ensure validity [73]. Convergent validity was assessed through factor loadings and average variance extracted (AVE), requiring loadings above 0.7 and AVE exceeding 0.5 to indicate construct internal consistency [72,74]. Discrimination validity was assessed using the Fornell-Larcker criterion, requiring the square root of a construct’s AVE to exceed its correlation coefficients with other constructs [75]. Analysis results (see Table 2 and Table 3) show that all constructs met the criteria for Cronbach’s α, CR, and factor loadings, with AVE exceeding 0.5, validating reliability and convergent validity. The square root of AVE for each construct was significantly higher than its correlation coefficient, confirming good discriminant validity.

Table 2.

Factor Analysis Results.

Table 3.

Test of Discrimination Validity.

4.2. Structural Model Evaluation and Hypothesis Testing

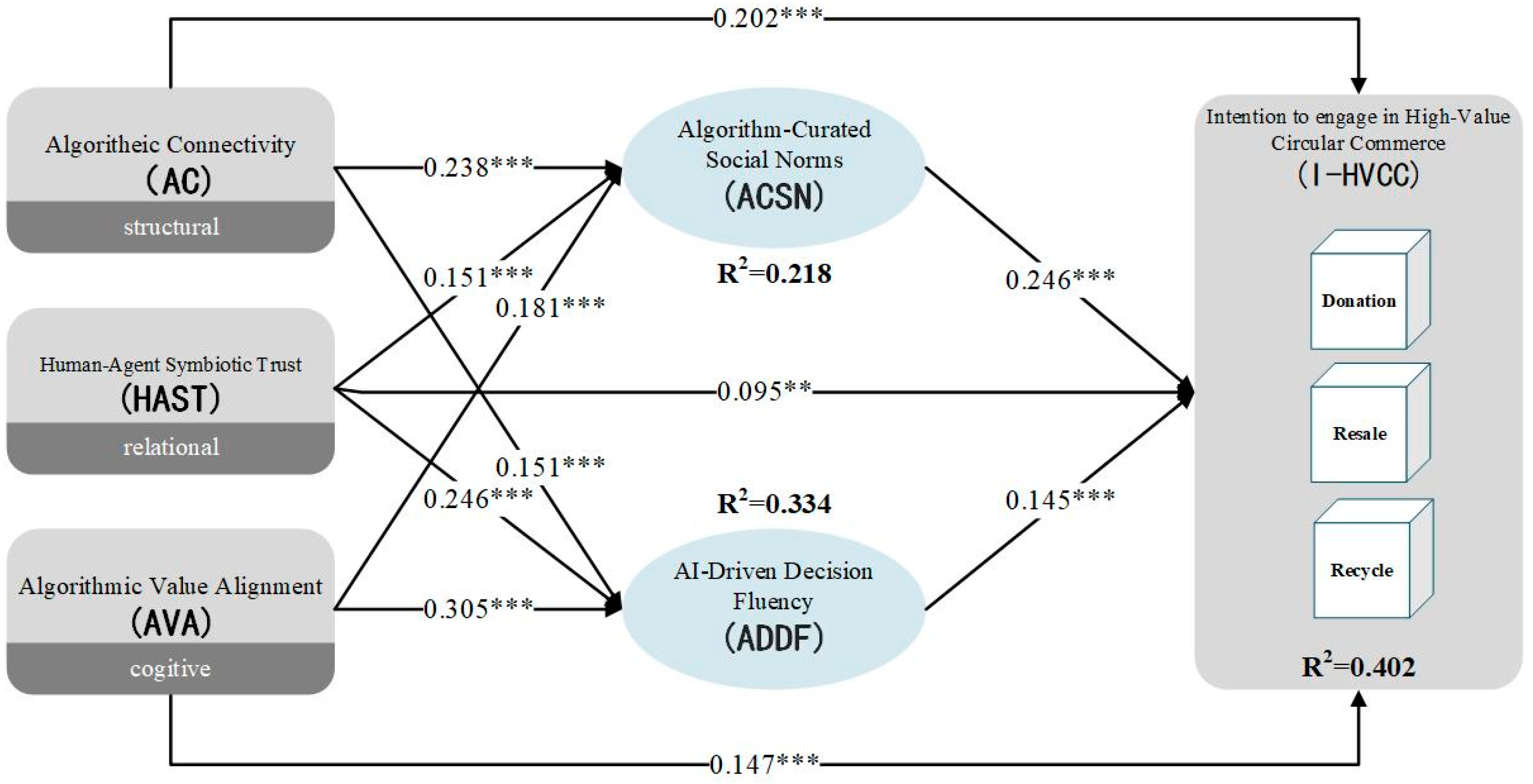

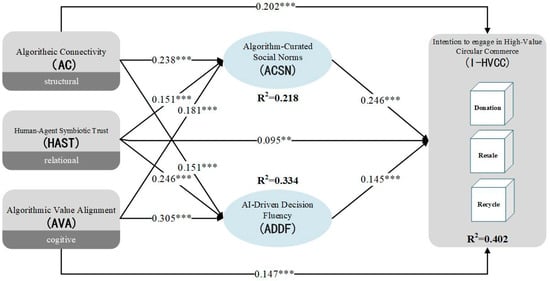

The PLS-SEM analysis tested the research hypotheses, revealing good model fit (Table 3 and Figure 3). The SRMR value of 0.058 falls below the 0.1 benchmark [76], indicating overall high model fit. VIF values ranged from 1.275 to 2.585, significantly below the 3.3 threshold [68], confirming the absence of multicollinearity issues. The model demonstrated good explanatory power: algorithm-curated social norms explained 21.8% of variance, AI-driven decision fluency explained 33.4%, and the final dependent variable participation willingness explained 40.2%. According to Hair et al. (2019) standards, this level is considered moderately strong [72], indicating the research model possesses good predictive validity. Results from 5000 bootstrap samples confirmed significant support for all proposed direct and indirect effect hypotheses (see Table 4 and Table 5).

Figure 3.

Research Results. (Notes: *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01).

Table 4.

Direct Effects.

Table 5.

Indirect Effects.

4.3. Robustness Check: Hierarchical Regression Analysis

To address potential endogeneity concerns and validate the robustness of our PLS-SEM findings, we conducted hierarchical multiple regression analysis following the approach recommended by Aabo et al. [77] This supplementary analysis tests whether our core relationships remain significant when controlling for demographic variables and when using ordered survey data in a regression framework.

Table 6 presents the results of three hierarchical models. Model 1 includes only demographic control variables (age, education level, and monthly spending). Model 2 adds the three dimensions of algorithmic empowerment (AC, HAST, and AVA) as independent variables. Model 3 presents the full model by further including the two mediating mechanisms (ACSN and ADDF).

Table 6.

Hierarchical Regression Analysis: Robustness Check.

The results demonstrate strong robustness. First, the F-statistics increase substantially across models (from 25.743 in Model 1 to 115.488 in Model 2 to 119.024 in Model 3, all p < 0.001), indicating that the addition of algorithmic empowerment dimensions and mediating mechanisms significantly enhances explanatory power. Second, the R2 progressively increases from 0.053 (Model 1) to 0.333 (Model 2) to 0.407 (Model 3), with the algorithmic empowerment dimensions alone contributing an incremental ΔR2 of 0.280 (p < 0.001), and the mediating mechanisms adding another ΔR2 of 0.074 (p < 0.001).

Most importantly, all three dimensions of algorithmic empowerment remain significant predictors of participation intention even after controlling for demographics. In Model 2, algorithmic connectivity exhibits the strongest effect (β = 0.240, p < 0.001), followed by algorithmic value alignment (β = 0.181, p < 0.001) and human-agent symbiotic trust (β = 0.122, p < 0.001). In the full model (Model 3), all three dimensions maintain their significance (AC: β = 0.168, p < 0.001; HAST: β = 0.069, p < 0.001; AVA: β = 0.112, p < 0.001), though coefficients decrease due to the mediating effects of ACSN (β = 0.111, p < 0.001) and ADDF (β = 0.246, p < 0.001). This pattern aligns with our theoretical model proposing dual mediation pathways.

In summary, the hierarchical regression analysis using ordered survey data corroborates our PLS-SEM findings, demonstrating that the observed relationships are robust to alternative analytical approaches, demographic controls, and potential endogeneity concerns. This consistency across methods strengthens confidence in our theoretical model and empirical conclusions.

5. Discussion

This study addresses the challenge that traditional human-centered theoretical frameworks struggle to fully explain user behavior in consumption scenarios deeply integrated with AI. We propose and validate the “algorithm empowerment” framework to systematically reveal how AI drives user engagement in high-value circular commerce. Empirical results provide robust support for this novel framework.

Core findings indicate that all three dimensions of AI empowerment perception—algorithmic connectivity, human–machine symbiotic trust, and algorithmic value alignment—significantly enhance user participation willingness. This demonstrates that users’ empowerment experience constitutes the fundamental driver of sustainable consumption behaviors. Simultaneously, the study uncovers a dual transmission mechanism for empowerment effects: first, by reinforcing users’ perception of algorithmic curation as a social norm, satisfying their needs for social recognition and belonging; second, by enhancing AI-driven decision-making fluency, reducing users’ decision costs when managing high-value categories. The overall model explains over 40% of the variance in user participation willingness, demonstrating the framework’s robust predictive value for user behavior.

These findings align with prior AI-empowerment research showing that intelligent systems enhance users’ confidence, perceived capability, and engagement in digital decision-making contexts. They are also consistent with TAM-based evidence that trust in technology and perceived usefulness drive user intention [16]. However, while TAM primarily focuses on functional evaluation, our results highlight the additional role of value alignment and identity construction in AI-mediated circular consumption. This suggests that, beyond adoption, AI shapes users’ self-expression and social meaning in high-value reuse decisions.

5.1. The Driving Force of AI Empowerment: A Paradigm Shift from Social Capital to Human–Machine Collaboration

This study posits that within deeply integrated AI digital platforms, the driving force behind user participation in high-value circular commerce has shifted from reliance on interpersonal network resources to active perception of human–machine collaborative empowerment. Empirical findings provide compelling evidence for this paradigm shift.

First, algorithmic connectivity exerts the strongest direct influence on user participation intent. Unlike the positional advantages derived from static interpersonal relationships in traditional social capital theory, algorithmic connectivity represents a dynamic structural empowerment actively created by AI. Here, AI acts as a “network architect,” helping users break through information barriers, create market opportunities, and connect communities. In high-risk, high-uncertainty secondhand luxury goods transactions, this technology-enabled structural advantage proves more compelling than traditional interpersonal relationships.

Second, human–machine symbiotic trust remains crucial, though its form has evolved. Traditional e-commerce relied on interpersonal interactions and reputation systems, whereas platforms deeply integrated with AI derive trust primarily from system reliability guarantees (e.g., smart authentication, platform guarantees, escrow services). In other words, users’ sense of security is shifting from “trust in people” to “trust in technology.”

Finally, algorithmic value alignment highlights the identity expression inherent in luxury disposal behaviors. Through resale or donation, users not only manage possessions but also articulate personal values—such as sustainable fashion, mindful consumption, or minimalist living. When AI not only enhances efficiency but also comprehends and aligns with user values, it becomes a true “value partner,” triggering deeper intrinsic motivations. This aligns strongly with green consumption research emphasizing “self-identity” as a behavioral driver [78,79], extending this insight to human–machine interaction scenarios.

5.2. Dual Mediation Mechanism: Parallel Logic of Social Identity and Cognitive Efficiency

This study reveals the influence mechanism of AI empowerment perception, primarily transmitted through two pathways: social identity and cognitive efficiency.

Along the social pathway, algorithmic curation social norms (ACSN) play a pivotal mediating role. Findings indicate that algorithms function not merely as information filters but as novel “fashion definers” and “norm shapers.” The community norms perceived by users do not emerge organically but are continuously constructed through algorithmic selection and reinforcement [30]. In the highly visible domain of luxury goods disposal, AI’s curatorial capabilities transform private actions into socially performative acts with public significance, thereby fulfilling users’ needs for recognition and self-presentation.

Cognitively, AI-driven decision fluency (ADDF) effectively bridges the “intention-behavior gap” users face in disposal decisions. Past research indicates many users hesitate despite intent, primarily due to decision-making “friction” [80,81]. ADDF significantly reduces this friction through “cognitive offloading,” enabling smoother transitions from intention to action. Notably, algorithmic value alignment (AVA) exerts the strongest influence on decision fluency, indicating that alignment between users’ values and AI recommendations enhances decision-making efficiency.

In summary, for AI systems to genuinely stimulate user engagement, they must possess a “dual-core drive”: serving both as efficient tools that reduce cognitive load and enhance decision-making efficiency, and as value guides that shape positive norms and reinforce identity. Neglecting either aspect may weaken their empowering effects, hindering sustained user participation in circular business.

5.3. Theoretical Contributions

This study contributes to the fields of information systems, consumer behavior, and sustainability in three ways.

First, we propose and validate the “Algorithmic Empowerment” framework, providing a new theoretical foundation for understanding how AI influences user behavior. Previous studies often treated AI as a tool or usage context, extending “social capital”-style approaches to explain user behavior [7,8]. This study shifts focus to users’ sense of empowerment by AI—not reliance on others’ resources, but the perception that “technology is actively helping me.” We further decompose this abstract experience into three measurable dimensions: algorithmic connectedness, human–machine trust, and value alignment. This elevates “AI empowerment” from a concept to an operational research object, laying the groundwork for subsequent quantitative studies.

Second, we reveal two core pathways through which AI influences behavior, enriching theories of technology adoption and algorithmic persuasion [11,57]. On one hand, decision fluency confirms efficiency remains a key driver of AI-influenced behavior. On the other, the “sense of social norms” generated by algorithmic curation demonstrates that algorithms not only enhance convenience but also shape users’ understanding of “what constitutes acceptable behavior.” In other words, AI’s persuasive power stems not solely from functional advantages but simultaneously operates at cognitive and socio-psychological levels. This dual-path mechanism provides a more comprehensive logical framework for explaining how AI sparks real-world actions.

Finally, this study offers a novel psychological perspective for understanding user behavior in high-value circular commerce. Existing sustainable consumption research often emphasizes environmental attitudes or economic incentives but struggles to explain why users are willing to make “letting go” decisions regarding high-risk, high-emotional-value items. This study reveals that the true driving force lies in whether users “feel empowered”—that is, whether they believe AI can ensure safety, reduce decision-making burden, and reflect their value stance. This finding expands sustainable behavior research from “human-to-human interaction” to “human-to-algorithm interaction,” offering a new research direction for designing AI to guide large-scale green behavior.

5.4. Practical Implications

The findings of this study hold not only theoretical significance but also provide actionable practical directions for secondhand trading platforms, AI product designers, and marketing strategists.

- From “Content Pusher” to “Resource Architect”—Maximizing Algorithmic Connectivity

Platforms should reposition AI from a mere content-pushing tool to a “resource architect” capable of building resource networks for users. Research indicates that algorithmic connectivity is the most direct factor driving user engagement. Platforms can deliver higher-value support by proactively matching users with critical information resources during disposal processes, predicting market trends with opportunity alerts, and even facilitating connections to experts or communities. This user-empowerment strategy significantly lowers cognitive and informational barriers in high-value transactions.

- 2.

- Building a “Digital Concierge”—Cultivating Human–Machine Symbiotic Trust

In high-risk, high-value transaction scenarios, platforms must position AI as a trusted “digital concierge.” This entails not only functional assistance but also conveying emotional warmth and transparency through interactions. For instance, leveraging natural language processing enables more empathetic conversational interactions, offering psychological support during exchanges. Simultaneously, introducing explainable AI provides clear rationale for critical recommendations, helping users understand the AI’s decision-making logic. Such design effectively reduces user uncertainty while enhancing their sense of security and trust during transactions.

- 3.

- From “Personalization” to “Value-Driven”—Becoming the User’s Value Ally

Platforms should transcend traditional personalized recommendations to cultivate deeper resonance based on shared values. Research indicates that aligning algorithms with values significantly boosts users’ intrinsic motivation. Platforms can not only amplify the meaning of transactions by promoting content related to environmental protection and the circular economy but also visualize users’ values through digital badges and exclusive tags displayed on personal profiles. This strategy enables users to construct their identity and express their values through transactions, transforming the platform into their “value ally” rather than merely a functional tool.

- 4.

- Building a “Dual-Core Engine”—Balancing Social Norms and Decision Fluency

Ultimately, the overall design of AI systems should balance social motivation and cognitive efficiency, forming a “dual-core engine.” On one hand, platforms can amplify the influence of social norms by prioritizing success stories from acquaintances or influencers and introducing gamified mechanisms like leaderboards and challenges. On the other hand, features such as auto-generated product descriptions, smart pricing, and escrow services minimize operational burdens and decision friction. This dual-path design satisfies users’ need for social recognition while ensuring smooth, convenient transactions, effectively converting intent into action.

6. Conclusions

The core finding of this study is that in an era where AI increasingly serves as a decision-making partner for users, sustainable consumption intent is not driven by economic incentives or social pressure alone, but by a sense of empowerment facilitated by AI. This empowerment is not abstract; it operates through two distinct pathways: algorithmic curation establishes social norms that satisfy users’ need for recognition, while AI-driven decision-making fluidity reduces barriers to action. In other words, AI systems capable of promoting circular business behaviors must inherently function as both “tools” and “companions.”

Although this study proposes a systematic theoretical model, several limitations suggest opportunities for future research. First, the cross-sectional self-reported design restricts our ability to capture the dynamic evolution of empowerment; future longitudinal or experimental studies could better examine how empowerment translates into sustained circular behaviors. Second, the sample is drawn from Chinese consumers, and cultural factors—such as stronger normative sensitivity in collectivist contexts—may amplify the role of social identity in empowerment. Future research should replicate this model in diverse cultural markets, particularly individualistic contexts, to evaluate generalizability and potential cultural variation. Finally, we have not yet explored which specific AI design features (e.g., explainability, anthropomorphism, transparency) maximize perceived empowerment. Future experimental research could manipulate these characteristics—such as comparing transparent AI recommendations with “black-box” recommendations, or varying the degree of conversational warmth in AI agents—to identify optimal design principles for empowerment. These directions would deepen theoretical insights and inform the development of more responsible, adaptive AI systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.R. and M.C.; methodology, X.R. and M.C.; software, L.L.; validation, X.R., M.C. and L.L.; formal analysis, X.R. and L.L.; investigation, X.R. and L.L.; resources, M.C.; data curation, L.L.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L.; writing—review and editing, X.R. and M.C.; visualization, L.L.; supervision, X.R.; project administration, X.R.; funding acquisition, X.R. and M.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant number LY22G030017), Zhejiang Provincial Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 24ZJQN059Y), National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant number 22BGL122), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Provincial Universities of Zhejiang (Grant number GK239909299001-211).This paper was also funded by the China Scholarship Council, which has been instrumental in facilitating this research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Academic Committee of the school of Management of Hangzhou Dianzi University (approved on 9 October 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Complete Questionnaire

| Constructs | Items | |

| Screening Questions | Q1: Do you currently own any idle luxury brand clothing items (e.g., designer dresses, coats, suits)? | □ Yes (continue) □ No (terminate survey) |

| Q2: Have you used any online secondhand trading platforms (e.g., Xianyu, Zhuanzhuan) within the past 12 months? | □ Yes (continue) □ No (terminate survey) | |

| Q3: Which city tier do you currently reside in? | □ First-tier city (Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen) □ New first-tier city (e.g., Hangzhou, Chengdu, Wuhan, etc.) □ Second-tier city □ Third-tier city or below (terminate survey) | |

| Algorithm Connectivity (AC) | AC1: This platform’s algorithms help me efficiently discover relevant market information and disposal techniques. | |

| AC2: Through algorithmic recommendations, I can easily connect with communities and potential buyers who share my interests. | ||

| AC3: Overall, this platform’s algorithm enhances my ability to access valuable re-sources. | ||

| Human-AI Symbiotic Trust (HAST) | HAST1: I trust that the platform’s AI assistants (e.g., smart valuation, escrow services) possess the professional capability to assist me in completing transactions. | |

| HAST2: I believe the recommendations pro-vided by the AI assistant (such as pricing suggestions and draft copy) are in my best interest. | ||

| HAST3: I find the AI assistant on this plat-form to be reliable and honest. | ||

| Algorithm Value Alignment (AVA) | AVA1: The content recommended by this platform’s algorithm (e.g., about sustainable fashion) aligns very well with my personal values. | |

| AVA2: I feel the consumption philosophy promoted by this platform’s algorithm is precisely what I endorse. | ||

| AVA3: Overall, this platform feels like it “really gets me,” aligning with my lifestyle and taste. | ||

| Algorithm-Curated Social Norms (ACSN) | ACSN1: On this platform, I feel most people are actively participating in the reuse of idle items. | |

| ACSN2: I feel that eco-friendly disposal practices on this platform are appreciated by community members. | ||

| ACSN3: The communities or influencers I follow mostly advocate for sustainable fashion consumption. | ||

| AI-Driven Decision Fluency (ADDF) | ADDF1: Deciding how to dispose of my unused luxury goods with the help of an AI assistant is a straightforward process. | |

| ADDF2: With AI assistance (such as one-click posting and smart valuation), I found the entire transaction process to be very smooth. | ||

| ADDF3: On this platform, listing and selling a used item doesn’t require much effort on my part. | ||

| Intention to engage in High-Value Circular Commerce (I-HVCC) | I-HVCC1: I plan to use this platform to sell my unused luxury goods in the future. | |

| I-HVCC2: I predict I will use this platform to resell or donate my unused luxury goods in the future. | ||

| I-HVCC3: Overall, I am highly willing to participate in circular fashion activities through this platform. | ||

References

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, K.; Peters, G.; Dahlbo, H.; Perry, P.; Rissanen, T.; Gwilt, A. The environmental price of fast fashion. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Y.T.H.; Nguyen, H.V. An alternative view of the millennial green product purchase: The roles of online product review and self-image congruence. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 33, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhiyan Consulting. Analysis of Policies, Industrial Chain, Market Scale and Development Prospects of China’s Second-Hand Luxury Goods Industry in 2024: Market Scale Continues to Grow, and the Second-Hand Luxury Goods Industry Gradually Matures [EB/OL]. Available online: https://www.chyxx.com/industry/1200474.html (accessed on 18 September 2025).

- Kim, I.; Jung, H.J.; Lee, Y. Consumers’ Value and Risk Perceptions of Circular Fashion: Comparison between Secondhand, Upcycled, and Recycled Clothing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zeng, X.; Turson, R. How does emotional attachment impact mobile phone recycling intention? Emotional process and contingencies. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 380, 125038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silalahi, A.D.K. Can Generative Artificial Intelligence Drive Sustainable Behavior? A Consumer-Adoption Model for AI-Driven Sustainability Recommendations. Technol. Soc. 2025, 83, 102995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silayach, N.; Ray, R.K.; Singh, N.K.; Dash, D.P.; Singh, A. When algorithms meet emotions: Understanding consumer satisfaction in AI companion applications. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 85, 104298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.M.; Hsu, M.H.; Wang, E.T. Understanding knowledge sharing in virtual communities: An integration of social capital and social cognitive theories. Decis. Support Syst. 2006, 42, 1872–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, A.L.; Lewis, S.C. Artificial intelligence and communication: A human–machine communication research agenda. New Media Soc. 2020, 22, 70–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, A.; Bansal, V. AI as decision aid or delegated agent: The effects of trust dimensions on the adoption of AI digital agents. Comput. Hum. Behav. Artif. Hum. 2024, 2, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Towards the Circular Economy: Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition. 2013. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/towards-the-circular-economy-vol-1-an-economic-and-business-rationale-for-an (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Turunen, L.L.M.; Pöyry, E. Shopping with the resale value in mind: A study on second-hand luxury consumers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 43, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, E. Rebirth fashion: Secondhand clothing consumption values and perceived risks. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 273, 122951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cogn. Sci. 1988, 12, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D.; Karahanna, E.; Straub, D.W. Trust and TAM in online shopping: An integrated model. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 51–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, J. Blockchain in luxury resale: The impact of blockchain technology through regulatory focus and uncertainty reduction theories. J. Consum. Behav. 2025, 24, 632–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Kang, J. Less Stress, Fewer Delays: The role of sophisticated AI in mitigating decision fatigue and purchase postponement in luxury retail. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 85, 104268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berthon, P.; Pitt, L.; Parent, M.; Berthon, J.-P. Aesthetics and Ephemerality: Observing and Preserving the Luxury Brand. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2009, 52, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R.W. Possessions and the extended self. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 139–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dommer, S.L.; Winterich, K.P. Disposing of the self: The role of attachment in the disposition process. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2021, 39, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital and value creation: The role of intrafirm networks. Acad. Manag. J. 1988, 41, 464–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.A. Taking aim on empowerment research: On the distinction between individual and psychological conceptions. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1990, 18, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spreitzer, G.M. Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 1442–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Luo, M.; Guo, Y. Deposit AI as the “invisible hand” to make the resale easier: A moderated mediation model. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glikson, E.; Woolley, A.W. Human trust in artificial intelligence: Review of empirical research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2020, 14, 627–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, T. The relevance of algorithms. In Media Technologies; Gillespie, T., Boczkowski, P., Foot, K., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bucher, T. The algorithmic imaginary: Exploring the ordinary affects of Facebook algorithms. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2016, 20, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reber, R.; Schwarz, N.; Winkielman, P. Processing fluency and aesthetic pleasure: Is beauty in the perceiver’s processing experience? Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2004, 8, 364–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alter, A.L.; Oppenheimer, D.M. The effect of processing fluency on judgment and decision making: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2020, 146, 549–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risko, E.F.; Gilbert, S.J. Cognitive offloading. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2016, 20, 676–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L. Investigating the effects of artificial intelligence-assisted language learning strategies on cognitive load and learning outcomes: A comparative study. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 2025, 62, 1741–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Zammuto, R.F.; Griffith, T.L.; Majchrzak, A.; Dougherty, D.J.; Faraj, S. Information technology and the changing fabric of organization. Organ. Sci. 2007, 18, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. A theory of social comparison processes. Hum. Relat. 1954, 7, 117–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozdag, E.; van den Hoven, J. Breaking the filter bubble: Democracy and design. Ethics Inf. Technol. 2015, 17, 249–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.D.; See, K.A. Trust in automation: Designing for appropriate reliance. Hum. Factors 2004, 46, 50–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Visser, E.J.; Pak, R.; Shaw, T.H. From ‘automation’ to ‘autonomy’: The importance of trust repair in human–machine interaction. Ergonomics 2018, 61, 1409–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, D.; Wohl, R.R. Mass communication and para-social interaction: Observations on intimacy at a distance. Psychiatry 1956, 19, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liebers, N.; Schramm, H. Parasocial interactions and relationships with media characters–an inventory of 60 years of research. Commun. Res. Trends 2019, 38, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kammoun, A. Human vs. Virtual Influencers in the Context of Influencer Marketing: A Comparative Analysis. In Redefining the Future of Digital Marketing with Virtual Influencers; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 89–122. [Google Scholar]

- McKnight, D.H.; Choudhury, V.; Kacmar, C. Developing and validating trust measures for e-commerce: An integrative typology. Inf. Syst. Res. 2002, 13, 334–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, M.J.; Duenser, A.; Lacey, J.; Paris, C. Collaborative human-AI trust (CHAI-T): A process framework for active management of trust in human-AI collaboration. Comput. Hum. Behav. Artif. Hum. 2025, 6, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, J. Self-Concept in Consumer Behavior: A Critical Review. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristof-Brown, A.L.; Zimmerman, R.D.; Johnson, E.C. Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Pers. Psychol. 2005, 58, 281–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, E.P.; Carrete, L. Green self-identity and consumer behavior: The mediating role of self-congruity. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 156, 113516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-Y. Persuasive messages on information system acceptance: A theoretical extension of elaboration likelihood model and social influence theory. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, K.; Morris, M.W. Values, schemas, and norms in the culture–behavior nexus: A situated dynamics framework. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2015, 46, 1028–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Lim, J. Value congruence and decision-making in sustainable consumption: The role of cognitive consonance. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turunen, L.L.M.; Cervellon, M.C.; Carey, L.D. Selling second-hand luxury: Empowerment and enactment of social roles. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Yoon, S. Social capital, user motivation, and collaborative consumption of online platform services. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, S.; Staats, H.; Sancho, P. Normative influences on adolescents’ self-reported pro-environmental behaviors: The role of parents and friends. Environ. Behav. 2019, 51, 288–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Bala, H. Technology acceptance model 3 and a research agenda on interventions. Decis. Sci. 2008, 39, 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, M.A. Factors affecting performance expectancy and intentions to use ChatGPT: Using SmartPLS to advance an information technology acceptance framework. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 201, 123247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, P.; König, C.J. Integrating theories of motivation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 889–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, C.; Kleinmann, M. How action initiation influences procrastination: A review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logg, J.M. Algorithm appreciation and decision effort reduction. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2021, 163, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, M.A. Toward a theory of learned hopefulness: A structural model analysis of participation and empowerment. J. Res. Personal. 1990, 24, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.S. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am. J. Sociol. 1988, 94, S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, D.M.; DeRue, D.S. The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di, K.; Chen, W.; Shi, Q.; Cai, Q.; Liu, S. Analysing the impact of coupled domestic demand dynamics of green and low-carbon consumption in the market based on SEM-ANN. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Fu, Y.; Li, Y. Young consumers’ motivations and barriers to the purchase of second-hand clothes: An empirical study of China. Waste Manag. 2022, 143, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, L. Second-hand luxury goods become a “new favorite” among young people. Bus. Obs. 2024, 10, 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Alsaad, A.; Alam, M.M.; Lutfi, A. A sensemaking perspective on the association between social media engagement and pro-environment behavioural intention. Technol. Soc. 2023, 72, 102201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]