Abstract

This study examines if peers’ digital transformation affects focal firms’ greenwashing, addressing the literature gap of insufficient focus on industry interactions via institutional theory. Using a sample of Chinese listed companies, the paper conducts an empirical analysis and finds that the digital transformation of peer enterprises significantly inhibits the greenwashing behavior of focal enterprises. This inhibitory effect is realized through three key mechanisms: the competitive peer spillover effect of digital transformation, the suppression of peer spillover in greenwashing behavior, and the convergence effect of industry-wide information disclosure quality. Moreover, this inhibitory effect is particularly pronounced in industries characterized by low short-termism tendencies, high technology intensity, high pollution levels, and fierce competition. Further research confirms that the initial emergence of highly digitalized enterprises in an industry triggers a “catfish effect,” and once the proportion of digitalized enterprises exceeds 50%, the inhibitory effect on greenwashing behavior becomes significantly stronger.

1. Introduction

Corporate green transformation has become a core pathway for achieving sustainable development. However, the emergence and proliferation of greenwashing behaviors have severely distorted the market order of green development. Greenwashing is characterized by companies exaggerating environmental disclosures and fabricating green practices to create a false image of environmental responsibility. This behavior is widely recognized as a new trend or a strategic means for firms to obtain additional competitive advantages: amid growing stakeholder attention to sustainability, companies can leverage superficial “green” narratives to attract eco-conscious consumers, secure socially responsible investment, or mitigate regulatory pressure—without undertaking the real costs of environmental improvement. At its core, this behavior stems from opportunism driven by information asymmetry and self-interest. At the same time, the widespread adoption of digital technologies is reshaping the logic of corporate operations. Digital transformation not only enhances the transparency of environmental information through technologies like big data and blockchain but also alters the competitive landscape of industries through collaborative effects. According to Xingye, et al. [1], the application rate of digital technologies among Chinese listed companies reached 91% in 2023. The digital penetration at the industry level provides a new governance perspective for curbing greenwashing behaviors. Against this backdrop, the effects of individual companies’ digital transformations are no longer sufficient to comprehensively explain the evolution of greenwashing behaviors within the industry. It is imperative to explore the transmission mechanisms of digital transformation on greenwashing behaviors from the perspective of industry interactions.

Corporate decision-making does not exist in isolation. The phenomenon of peer effects, as a common organizational behavior, has been shown to significantly influence enterprises’ decisions related to innovation [2,3], investment [4,5], and social responsibility fulfillment [6,7]. The spillover effects among peer enterprises manifest not only in the horizontal diffusion of technology and management practices but also in the imitation of strategic behaviors and competitive responses [8,9]. Their impact spans the entire chain of corporate strategy formulation, operational management, and information disclosure [10,11,12]. In the context of an accelerating digital transformation across industries, the digital practices of peer enterprises can influence the transformation process of focal enterprises through pathways such as technological diffusion and experiential imitation. Moreover, they may indirectly affect the greenwashing decisions of focal enterprises by altering the industry information environment, competitive intensity, and regulatory pressures. This industry-level governance effect triggered by peer digital transformation offers a potential breakthrough in addressing the challenges of managing greenwashing behavior; however, existing research has yet to explore this issue.

Existing research on the factors influencing corporate greenwashing behavior primarily analyzes the issue through single frameworks, such as legitimacy theory [13,14], stakeholder theory [15,16], and agency theory [17,18]. Although some studies have examined the effects of external environmental factors, like government regulation [19] and media oversight [20], the existing literature often limits its boundaries to the characteristics of focal enterprises themselves—such as size and governance structure [21]—or the macro institutional environment [22], neglecting the potential impact of interactions among peer enterprises within the industry. A small number of studies addressing the relationship between digital transformation and greenwashing have primarily focused on the direct effects of a firm’s own level of digitalization [23,24,25,26], failing to reveal the underlying logic of how the digital transformation of peer enterprises can suppress greenwashing behaviors through spillover effects. Existing studies not only overlook the impact of industry peer interactions on greenwashing but also fail to reveal the internal logic by which digital transformation inhibits greenwashing through multiple industry-level mechanisms. They also lack exploration of the dynamic process and critical conditions of digital governance. This leads to a significant limitation in the understanding of governance pathways for managing greenwashing behavior.

This study systematically explores the impact of peer enterprises’ digital transformation on the greenwashing behaviors of focal enterprises from the dual perspectives of peer effects theory and institutional theory. We aim to reveal the new theoretical logic of how peer digital transformation affects greenwashing through three transmission mechanisms and two theoretical propositions. First, this paper incorporates the digital transformation of peer enterprises into the analytical framework of factors influencing greenwashing behaviors, moving beyond the traditional focus on individual firms to expand the industry interaction perspective on greenwashing governance. Second, through theoretical analysis and empirical testing, it deconstructs three pathways of influence based on institutional theory: the competitive peer spillover effect of digital transformation, the proactive peer spillover effect of greenwashing behaviors, and the convergence effect of industry disclosure quality, thereby clarifying the transmission mechanism by which peer digital transformation suppresses greenwashing behaviors. Finally, by combining heterogeneity analysis and further analysis, this study reveals the differences in the suppressive effects under various types of digital technologies and industry characteristics, while also validating the existence of the “catfish effect” in industry digitalization and the threshold of penetration rates. The findings of this research not only provide theoretical references for enterprises in formulating green transformation and digital strategies but also offer empirical evidence for regulatory bodies in constructing industry collaborative governance systems to curb greenwashing behaviors.

2. Theoretical Framework

Existing research primarily analyzes the factors influencing corporate greenwashing behavior based on three key theories. First, legitimacy theory posits that companies may engage in symbolic environmental disclosure to achieve institutional legitimacy, with the strength of institutional constraints directly shaping their behavioral choices [27]. Second, stakeholder theory emphasizes external pressures from entities such as consumers and investors, suggesting that the level of environmental concern and discernment ability of stakeholders determines the effectiveness of such constraints on corporate actions [28]. Finally, principal-agent theory approaches greenwashing from the perspective of internal governance, attributing the behavior to a conflict between managerial opportunism and insufficient shareholder oversight [17]. These studies largely focus on the characteristics of focal firms or broader macro-level environments, forming the foundational analytical framework. However, when it comes to examining the impact of peer firms on greenwashing behavior, existing theories often fall short. According to the theory of peer effects, the spillover effect implies that the actions of one firm can influence the decisions and strategies of other similar firms. Successful practices and innovations are frequently imitated, driving industry-wide transformation and development, which may also affect greenwashing behaviors across firms. Therefore, it is critical to integrate greenwashing-related theories with the spillover effects of peer firms to conduct a more comprehensive analysis.

In this section, we propose a novel theoretical framework to analyze the impact of peer firms’ digital transformation on the greenwashing behavior of focal firms. This framework is rooted in institutional theory, leveraging the concepts of mimetic isomorphism and normative pressures to better understand the spillover effects of peer firms’ digital transformation and explore how these effects can influence corporate greenwashing behavior.

2.1. Mechanisms of Digital Transformation Spillover Among Peer Companies

From the perspective of institutional theory, the spillover effects of digital transformation among peer companies can be understood through mimetic isomorphism. When an enterprise successfully achieves digital transformation, it sets a benchmark within the industry, prompting competitors to imitate its strategies to remain competitive [29]. Mimetic pressures arise as companies perceive the adoption of digital technologies not only as a means to gain efficiency and innovation but also as a way to conform to evolving industry norms shaped by leading enterprises. This imitation is driven by uncertainty about market demands and the pressure to avoid falling behind [30].

Digital transformation also creates coercive pressures within the competitive landscape. When leading companies leverage digital technologies to enhance their market share and responsiveness, lagging firms face pressure from stakeholders—investors, regulators, and customers—to adopt similar transformations [31]. Regulatory agencies may indirectly enforce these transformations as governments increasingly promote digitalization policies and data transparency initiatives. Normative pressures further arise as professional associations, industry standards, and technological consulting firms promote best practices for digital adoption, encouraging conformity to industry-wide norms.

In this context, institutional theory provides a framework to understand why digital transformation spreads rapidly among peer companies. Enterprises are driven not only by competitive dynamics but also by institutional pressures to conform to the industry’s evolving standards of technological innovation and performance. This convergence contributes to the competitive spillover effects and accelerates digital transformation across the industry.

In summary, the digital transformation of peer enterprises will influence the focal enterprise through competitive peer spillover effects. Existing research has shown that digital transformation has a significant inhibitory effect on a company’s greenwashing behavior [23,24,25]. Therefore, the digital transformation of enterprises within the same industry will indirectly improve the greenwashing situation of the focal enterprise. Based on this analysis, we propose the first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.

The digital transformation implemented by peer firms transmits to focal firms through competitive peer spillover effects, thereby improving the focal firms’ greenwashing behavior.

2.2. Mechanisms of Greenwashing Spillover Among Peer Companies

Institutional theory also sheds light on the spread of greenwashing behavior among peer companies. Mimetic isomorphism explains how companies imitate successful greenwashing strategies adopted by competitors. When a leading enterprise uses greenwashing to gain a competitive edge in brand image and market positioning, other firms in the industry are likely to replicate these practices [32]. They view greenwashing as a socially accepted and potentially effective strategy to respond to growing demand for environmental responsibility and stakeholder expectations [33]. This imitation is compounded by uncertainty about how best to meet these demands [30].

Normative isomorphism plays a critical role in the dissemination of greenwashing behavior. Industry standards, professional networks, and media coverage often normalize greenwashing practices, inadvertently legitimizing them. As environmental reporting and corporate social responsibility become integral to corporate practices, companies face normative pressures to demonstrate their commitment to sustainability—even if these demonstrations are superficial.

Additionally, coercive pressures arise from market competition and regulatory frameworks. When greenwashing becomes widespread within an industry, stakeholders—such as investors, customers, and regulators—may indirectly pressure companies to adopt similar strategies to maintain competitiveness [34]. For instance, firms that fail to align themselves with market expectations risk losing socially conscious consumers and investor confidence [35]. Regulatory scrutiny may also incentivize companies to disclose environmental practices, even if those disclosures are exaggerated or misleading.

Therefore, the spread of greenwashing behavior is more of an active response based on market demand and external pressure, combined with the group effect, leading to its rapid dissemination and becoming a common phenomenon in the industry. According to previous analyses, digital transformation can significantly suppress greenwashing behavior in enterprises. As the digital transformation process accelerates among peer companies, the level of greenwashing within the industry will significantly decrease, alleviating the competitive pressure on focal companies caused by the greenwashing of their peers, thus further reducing their own level of greenwashing. Based on this, we propose the second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2.

The reduced greenwashing from peer firms’ deepened digital transformation alleviates the peer spillover effect of peer greenwashing on focal firms, thereby lowering focal firms’ greenwashing level.

2.3. Mechanisms of Industry Disclosure Quality Convergence

The digital transformation within the same industry has effectively suppressed greenwashing behavior among focal companies by enhancing the quality of information disclosure. This is primarily attributed to the increased transparency and improved information sharing brought about by digital transformation, which makes companies’ environmental performance more visible. With the advancement of digital technologies, companies can more efficiently collect, analyze, and disclose environmental-related data [36], thereby enhancing the transparency and quality of environmental information. For instance, many companies are adopting advanced data analysis tools to monitor and report their environmental impacts in real-time, allowing stakeholders to gain a clearer understanding of the companies’ environmental performance [37]. This transparency not only strengthens trust between companies and consumers but also creates a demonstration effect within the industry, prompting other companies to follow suit.

Additionally, digital transformation has driven the homogeneity of industry regulation. Institutional theory suggests that coercive, normative, and mimetic pressures can lead to organizational convergence [30]. The widespread adoption of digital technologies enables regulatory agencies to more easily access industry environmental information, thereby strengthening supervision and increasing penalties for non-compliance [38]. To maintain industry reputation and avoid scrutiny from the public and competitors, companies need to enhance the quality of their environmental information disclosure [39]. Consequently, focal companies are also influenced by the digital transformation of their peers, leading them to adhere to higher standards of environmental disclosure.

In summary, the digital transformation of peer companies has suppressed greenwashing behavior by improving information disclosure quality and promoting transparency within the industry, thereby advancing overall environmental compliance and sustainability. Based on this, we propose the third hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.

The digital transformation of peer firms promotes the convergence of industry disclosure quality, which in turn inhibits the focal firms’ greenwashing behavior.

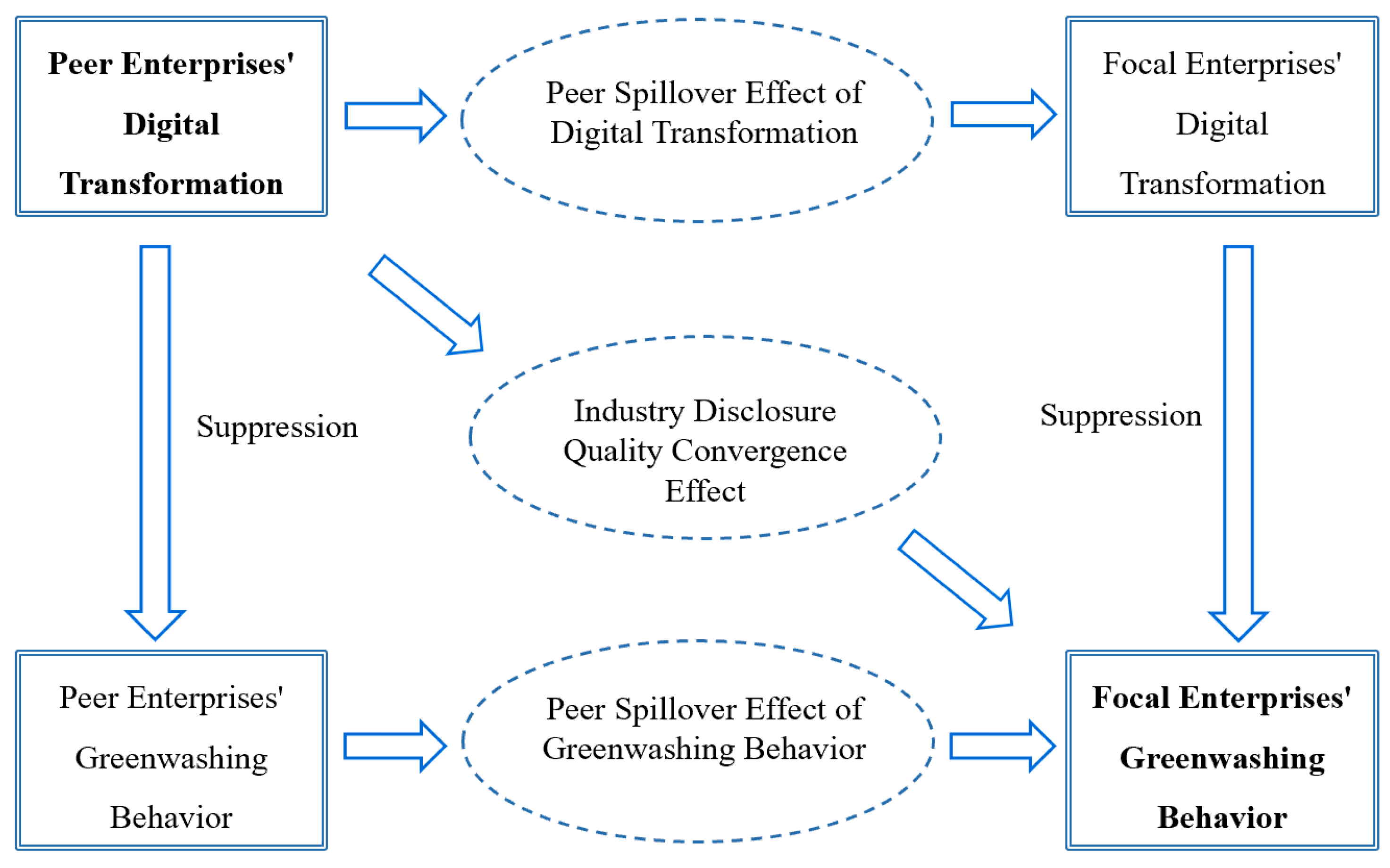

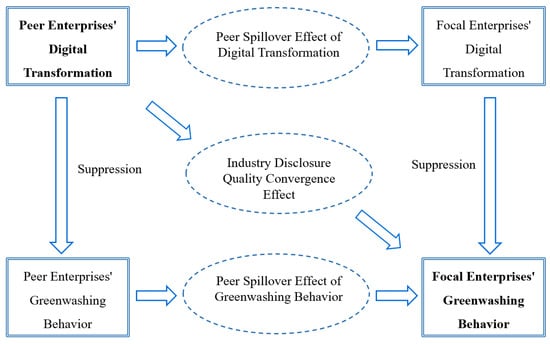

Based on the above analysis, the mechanisms through which peer enterprises’ digital transformation influences the greenwashing behavior of focal enterprises include the peer spillover effect of digital transformation, the peer spillover effect of greenwashing behavior, and the industry disclosure quality convergence effect, as illustrated in Figure 1:

Figure 1.

Mechanism of peer enterprises’ digital transformation on greenwashing behavior.

3. Research Design

3.1. Model

To verify the spillover effects of digital transformation of peer enterprises on the greenwashing behavior of focal enterprises, this paper constructs a two-way fixed effects model, as shown below:

In the equation, and represent the enterprise and year, respectively; denotes the level of greenwashing of the enterprise; refers to the degree of digital transformation of peer enterprises. is the impact coefficient of peer firms’ digital transformation on the focal firm’s greenwashing behavior. If is significantly negative, it indicates that the digital transformation of peer firms significantly inhibits the focal firm’s greenwashing behavior, i.e., the inhibitory effect of digital transformation on greenwashing behavior spills over among firms within the same industry. denotes control variables; represents firm-fixed effects; stands for year-fixed effects; and is the random error term. Since both the explanatory variable and the dependent variable are firm-level indicators, we cluster the standard errors at the firm level.

3.2. Variable Definition

3.2.1. Dependent Variable: Greenwashing Behavior

Drawing on existing research, this paper adopts the “Disclosure-Performance Matching Method” to measure the level of corporate greenwashing. Specifically, the difference between a firm’s environmental information disclosure rating and its environmental performance rating is used as the indicator for measuring the degree of greenwashing. Given that the evaluation criteria for environmental information disclosure ratings and environmental performance ratings may differ, this paper standardizes the environmental information disclosure scores and environmental performance scores, respectively, to ensure their comparability at the numerical level. The specific calculation formula for the degree of greenwashing is as follows:

where represents the degree of greenwashing of firm in year , is the environmental information disclosure score, and is the environmental performance score. and are the means of environmental information disclosure scores and environmental performance scores of firms, respectively, and and are the standard deviations of environmental information disclosure scores and environmental performance scores of firms, respectively. If the environmental information disclosure score is higher than the environmental performance score, it indicates that the actual environmental performance of the firm is not as good as what is disclosed, which means the firm engages in greenwashing behavior. The greater the difference between the two scores, the higher the degree of greenwashing of the firm. We use the environmental dimension disclosure score from the Bloomberg ESG scoring system to measure companies’ environmental information disclosure performance, and adopts the environmental performance score from the China Securities Index ESG Rating Index as the indicator for measuring environmental performance.

Furthermore, drawing on the research of Grennan [40], this study defines peer firms as other enterprises within the same industry. Specifically, to measure the greenwashing degree of peer firms, this study adopts the industry average value after excluding the focal firm, with the calculation formula presented as follows:

where denotes the greenwashing degree of firm in industry during year ; represents the total greenwashing degree of all firms in industry ; and stands for the total number of firms.

3.2.2. Independent Variable: Digital Transformation

Drawing on the approach of Wu, et al. [41], this paper employs Python 2.7.16 web crawler technology to extract keywords related to digital transformation from the annual reports of listed companies. These keywords are sourced from Chinese local government reports, the 14th Five-Year Plan for the Development of the Digital Economy, and research reports on the digital transformation of Chinese enterprises issued by authoritative institutions such as Tsinghua University. Based on the conceptual definition of digital transformation in this paper, the keywords of digital transformation are divided into two levels: “underlying technology architecture” and “technology practice application”. Among them, the “underlying technology architecture” includes four major digital technologies, namely artificial intelligence, big data, cloud computing, and blockchain, while “technology practice application” emphasizes the application and transformation of digital technologies in actual business scenarios. In total, there are more than 100 keywords related to digital transformation. Then, the frequency of these feature words is used to measure the digitalization level of enterprises. The frequency of words related to digital transformation mentioned in enterprises’ annual reports is used as an indicator to measure the level of digitalization. Due to the potential huge differences in the number of annual report texts disclosed by enterprises, this paper draws on the processing method of Yuan, et al. [42] and divides the word frequency related to digital transformation by the total word frequency of the annual report texts to finally obtain the enterprise digital transformation index (Dig). For the convenience of expression, this indicator is multiplied by 10,000 in this paper.

3.2.3. Control Variables

Corporate greenwashing behaviors are influenced by multiple factors. To accurately estimate the relationship between digital transformation and greenwashing and avoid errors from unobservable factors, this paper introduces control variables from firm characteristics and corporate governance. Firm characteristics include enterprise size (Size), leverage ratio (Lev), fixed asset proportion (Fixed), listing years (Listage), and cash flow ratio (Cashflow); corporate governance aspects involve board size (Board), CEO–chairman duality (Dual), and independent director proportion (Indep). Additionally, the robustness tests control for regional factors affecting greenwashing, such as economic development level (Pgdp), population density (Pop), technological progress (Tech), and human capital (Hum).

3.3. Data Description

Considering the environmental performance score data starts to be fully disclosed in 2009 and the availability of control variables, this study sets the sample period as 2009–2022. The raw data are processed as follows: (1) ST, ST*, and PT enterprises within the sample period are excluded; (2) samples with missing observations on key variables are removed; (3) financial sector companies are excluded; (4) non-ratio variables are log-transformed to mitigate heteroscedasticity and non-stationarity; (5) minor missing values are imputed—using the average growth rate method for the first and final years and linear interpolation for intermediate years. The dataset comprises 13,079 observations from 1403 listed firms. Since only one enterprise exists in some industries that year, excluding the focal enterprise results in a loss of 76 samples, with the final number of sample observations being 13,003. Data disclosed by listed companies are sourced from the China Stock Market and Accounting Research (CSMAR) database and China Research Data Service (CNRDS). Environmental performance scores are obtained from the Wind database. Regional-level data are drawn from the Annual China Statistical Yearbook and China Urban Statistical Yearbook across years. Descriptive statistics for the variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Regression

Table 2 reports the results of the impact of peer firms’ digital transformation on the greenwashing behavior of target firms. Columns (1) and (2) present the estimation results of the two-way fixed effects model without and with control variables, respectively. The results show that the coefficients of peer firms’ digital transformation on the focal firm’s greenwashing behavior are both significantly negative at the 1% significance level. In addition, Columns (3) and (4) illustrate the impact of the extent of peer firms’ digital transformation on environmental disclosure (ED) scores and environmental performance (EP) scores. When controlling for ED scores, the coefficient of peer digital transformation on EP scores is significantly positive. Conversely, when controlling for EP scores, the coefficient on ED scores turns significantly negative. This indicates that the digital transformation of peer firms enhances the actual environmental performance of target firms while reducing their disclosure scores, further confirming that it effectively curbs corporate greenwashing behavior.

Table 2.

Results of peer firms’ digital transformation on focal firms’ greenwashing behavior.

4.2. Endogenous Discussion

4.2.1. Lagged Independent Variable

To address the endogeneity issue arising from reverse causality, we first adopt a lagged treatment strategy for the independent variables. As shown in Table 3, the coefficients of the impact of peer firms’ digital transformation (with lags from 1 to 4) on the focal firm’s greenwashing behavior are all significantly negative. This indicates that peer firms’ digital transformation exerts a lasting effect on the focal firm’s greenwashing behavior, similar to its persistent impact on their own operations and the upstream industries.

Table 3.

Results of lagged explanatory variables.

4.2.2. Difference-in-Differences Method

Based on the pilot program for supply chain innovation and application, this paper constructs a continuous difference-in-differences model to further address the potential endogeneity of peer firms’ digital transformation. The primary task of pilot enterprises is to apply modern information technologies to drive the digitalization and intelligent development of the entire industrial chain. Existing literature suggests that this pilot program is highly connotative of supply chain digitalization and has been studied as a quasi-natural experiment on digital transformation [43].

A critical concern about the DID model is policy targeting bias—that the pilot program may not be randomly assigned across industries. First, it is necessary to clarify the selection mechanism of the pilot program: the supply chain innovation and application pilot program was determined through a strict review process of application plans by experts. Local enterprises voluntarily declared, and the review expert group, composed of industry experts, academic scholars and government officials, evaluated the declared plans from multiple dimensions such as supply chain integration capability, digital transformation foundation, and green development potential. Finally, 55 pilot cities and 266 pilot enterprises were identified.

This review-based selection mechanism provides an important foundation for the exogeneity of the pilot program: on the one hand, the review focuses on the supply chain operation and digital transformation capability of enterprises, which is a “supply-side” capability evaluation that is not directly related to the “demand-side” greenwashing behavior of enterprises (greenwashing is more related to external information disclosure and stakeholder pressure, with weak direct correlation to supply chain intrinsic capability); on the other hand, the multi-subject expert group and multi-dimensional evaluation system avoid the single tendency of policy selection, reducing the possibility of selection bias caused by subjective preferences.

First, the industries of listed companies are divided into two groups: those more affected by the pilot program and those less affected, and an industry shock dummy variable is constructed accordingly :

where represents the number of pilot enterprises in industry , is the average number of pilot enterprises in the industry. If the number of pilot enterprises in an industry is greater than the average, it is considered to be more affected by the pilot program, in which case = 1; otherwise, it is 0. A difference-in-differences model is used to test the impact of the degree of digital shock from peer firms on corporate greenwashing behavior, as shown below:

where is a dummy variable for the period before and after the pilot program. If the time is 2018 or later, ; otherwise, . If the regression coefficient is significantly greater than 0, it indicates that the supply chain digitalization shock from peer firms has inhibited the greenwashing behavior of the focal firm.

The results of the DID model are presented in Table 4. As shown in Columns (1) and (2), regardless of whether control variables are included, the impact of peer firms’ digitalization pilot shock on corporate greenwashing behavior is negative and significant at the 1% level. It is worth noting that if the focal firm is a pilot enterprise, the supply chain digitalization pilot shock from peer firms will include the impact of the focal firm’s own digital transformation, which may lead to an inaccurate measurement of the extent of peer firms’ supply chain digitalization shock. Therefore, Columns (3) and (4) report the regression results of the continuous DID model after excluding the samples of pilot enterprises. It can be found that after excluding pilot enterprise samples, the coefficient of the peer firms’ supply chain digitalization shock indicator remains significantly negative at the 1% level, and the coefficient is larger than that of the full sample. This indicates that the results of the DID model are robust.

Table 4.

Results of Difference-in-Differences method.

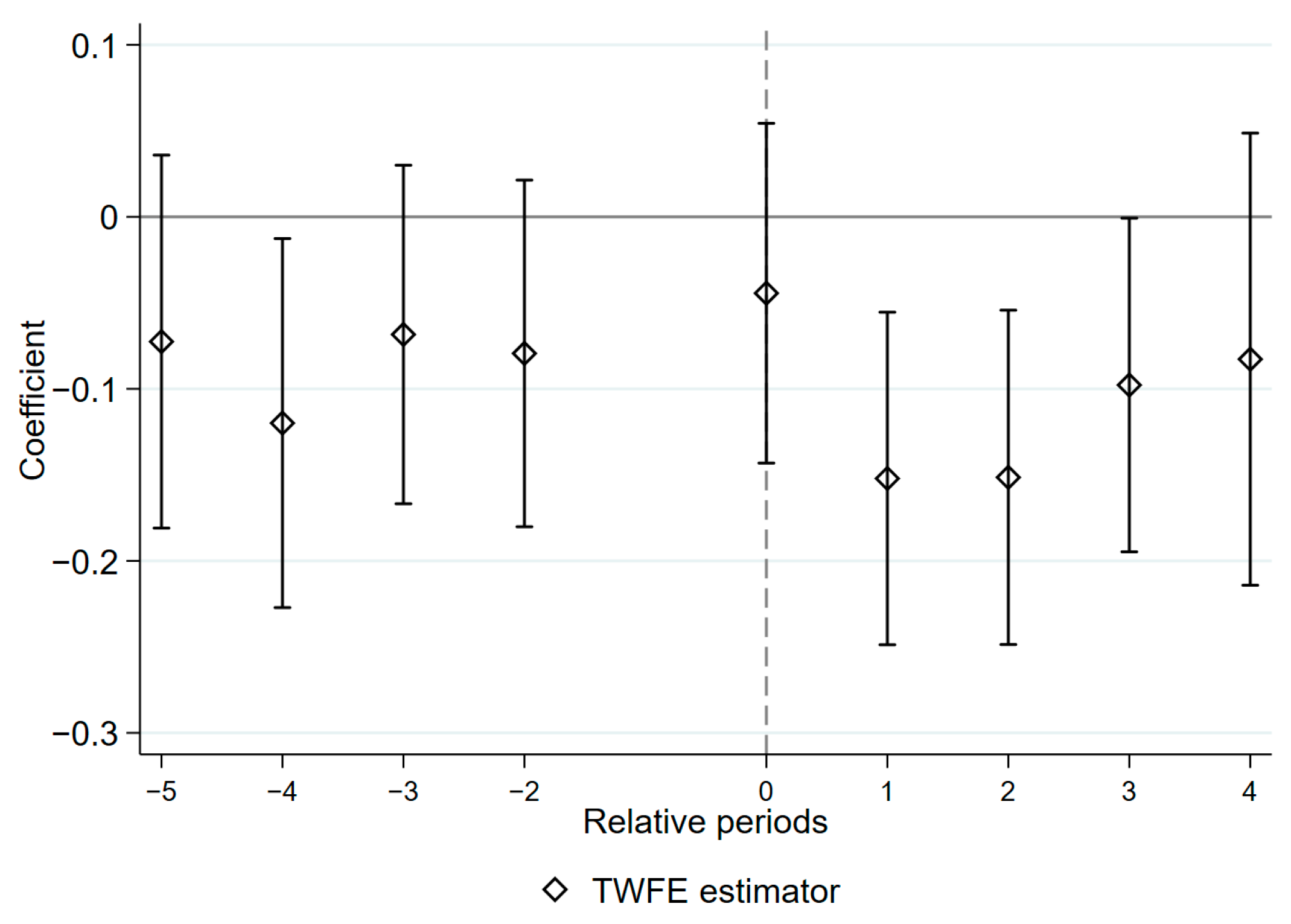

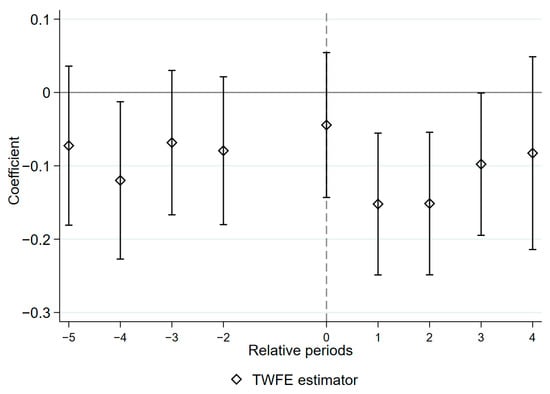

To ensure the robustness of the DID model, a parallel trend test is conducted below. Following the approach in the previous literature, the period immediately preceding the policy implementation is excluded as the reference period to avoid multicollinearity. Given the small number of samples from more than 5 years before the policy implementation, these samples are merged into the −5th period. Since the pilot program was launched in a single year, the two-way fixed effects (TWFE) estimator is free from contamination issues, making the results reliable. As shown in Figure 2, the DID model used in this paper satisfies the parallel trend assumption, indicating that the aforementioned results are not driven by pre-existing trends. The supply chain digitalization shock from upstream industries exerts a significant inhibitory effect on the greenwashing behavior of focal firms, and this effect is persistent.

Figure 2.

Parallel trend test of supply chain digitalization shocks from peer firms.

4.2.3. Instrumental Variable Method

First, drawing on the approach of Bartik instrumental variable method [44], the predicted value of the degree of peer firms’ digital transformation is constructed using the shift-share method as the first instrumental variable (IV1), as shown in the following formula:

where represents the degree of digital transformation of peer firms in the base period, and denotes the growth rate of the average degree of digital transformation of peer firms outside industry in year relative to the average in the base period. The growth rate of the degree of digital transformation of peer firms in industry is closely related to the average growth rate of the degree of digital transformation of peer firms across all industries, which ensures IV1’s relevance. Critically, excluding industry from growth rate calculation is the core exogeneity guarantee: it makes IV1 capture only cross-industry macro digital trends (not industry-specific traits). As greenwashing is driven by firm-internal or micro-industry factors, IV1 avoids direct impact, satisfying exogeneity. Therefore, this instrumental variable satisfies the conditions of relevance and exogeneity.

Second, the second instrumental variable (IV2) is constructed using the Lewbel instrumental variable method based on heteroscedasticity [45]. Traditional instrumental variable methods require finding exogenous variables that are correlated with endogenous variables but uncorrelated with the error term. The Lewbel method, however, does not rely on exogenous variables; instead, it constructs instrumental variables by leveraging the characteristics of other variables in the model. This method posits that when there are certain exogenous variables in the equation and the error term exhibits heteroscedasticity, endogeneity can be identified without imposing additional standard exclusion restrictions. This study employs the Breusch–Pagan/Cook–Weisberg test for verification: first, we regress the endogenous variable on control variables and extract the residuals, then conduct the heteroskedasticity test. The results show a chi-square statistic of 1206.60 with 1 degree of freedom (chi2(1) = 1206.60) and a p-value of 0.0000 (Prob > chi2 = 0.0000), which strongly rejects the null hypothesis of homoskedasticity and confirms the presence of significant heteroskedasticity. Specifically, one can perform an OLS regression of the endogenous variable on exogenous variables to obtain residuals, then use the product of these residuals and the exogenous variables as instrumental variables to estimate the original equation via two-stage least squares (2SLS).

Third, following the approach of Leary and Roberts [46], the third instrumental variable (IV3) is constructed using the idiosyncratic stock returns of firms within the same industry. On one hand, the stock returns of peer firms contain idiosyncratic information about other companies in the industry and are highly correlated with the overall level of digital transformation among peers. On the other hand, Leary and Roberts [46] indicate that idiosyncratic stock returns exhibit favorable exogeneity properties, including the absence of serial correlation and cross-sectional correlation. Idiosyncratic stock returns are extracted from overall stock returns and contain only information specific to individual stocks, which means they cannot predict the greenwashing degree of the firm itself or other companies. This also indirectly reflects that the industry-average idiosyncratic stock returns do not directly affect the error term. The calculation formula for idiosyncratic stock returns is as follows:

where denotes the stock return of company in industry in month ; represents the risk-free rate in month , which is replaced by the one-year time deposit interest rate; indicates the average stock return of peer companies of firm in month ; , , , and respectively stand for the four factors in the Carhart four-factor model, namely market, size, book-to-market ratio, and momentum; is the random disturbance term. At the beginning of each year, the data of the sample companies in the previous 36 months are used to regress Equation (7). In each month of the year, with the same regression coefficients, the expected value of the excess return of each stock per month () is calculated according to Equation (8), and the idiosyncratic stock return () is calculated according to Equation (9). Then, the monthly idiosyncratic stock returns of a single stock are simply compounded to obtain the annual idiosyncratic stock return. Finally, the average is calculated according to the industry to which the enterprise belongs, and the industry-average idiosyncratic return is constructed as an instrumental variable.

Table 5 presents the regression results of the 2SLS method based on the three instrumental variables. It can be observed that all three instrumental variables have a high correlation with the digital transformation of upstream industries, and there is no issue of weak instrumental variables (the F-statistic in the first stage is greater than 10). In addition, the Kleibergen–Paap rk LM statistic also rejects the null hypothesis that the instrumental variables are unidentifiable at the 1% significance level. It can be found that regardless of which instrumental variable is used, the impact of peer firms’ digital transformation on the greenwashing behavior of focal firms is significantly negative. Moreover, the absolute value of the coefficient in the 2SLS regression results is larger than that in the benchmark regression results, indicating that the benchmark regression results are robust.

Table 5.

Results of the 2SLS method.

4.3. Robustness Test

4.3.1. Adding Control Variables

Column (1) of Table 6 incorporates control variables at the prefecture-level city level, including economic development, population density, technological level, and human capital, to test the robustness of the baseline regression. After including these regional control variables, the coefficient for the impact of peer firms’ digital transformation on focal firms’ greenwashing behavior remains significantly negative at the 1% level. This finding indicates that the baseline regression results are robust.

Table 6.

Robustness tests.

4.3.2. Controlling Interactive Fixed Effects

This paper incorporates city-year interactive fixed effects into the model to rule out potential impacts of time-varying city characteristics on firms’ greenwashing behavior. Results from controlling for these interactive fixed effects are presented in column (2) of Table 6. It can be observed that after imposing stricter controls on fixed effects in the model, the coefficients of the explanatory variable remain significantly negative at the 1% level, indicating that the inhibitory effect of peer firms’ digital transformation on greenwashing behavior is robust.

4.3.3. Clustering Standard Errors at a Higher Level

In the baseline regression, standard errors are clustered at the firm level. This paper further clusters standard errors at the city, provincial, and industry levels. Column (3) of Table 6 reports the regression results with standard errors clustered at the city level. Column (4) presents the results when standard errors are clustered at the provincial level, while Column (5) shows those with standard errors clustered at the industry level. It can be seen that the impact of peer firms’ digital transformation on focal firms’ greenwashing behavior remains significantly negative, which indicates that the results of the baseline regression are robust.

4.3.4. Replacing the Dependent Variable

Following the method of Hu, et al. [47], we construct two variables: Oral and Actual. Oral is an indicator variable equal to 1 if a firm’s keyword frequency exceeds the industry median, and 0 otherwise. Actual is an indicator variable equal to 1 if the firm received an environmental penalty in the current year and 0 otherwise. We then multiply these two variables to generate the dummy variable GW2, which measures whether a firm engages in greenwashing. As shown in Column (6) of Table 6, after replacing the dependent variable, the impact of peer firms’ digital transformation on focal firms’ greenwashing behavior remains significantly negative at the 1% level. Moreover, the coefficient is larger in magnitude compared to the baseline regression results, which indicates that the baseline regression results are robust.

4.3.5. Replacing the Independent Variable

Following the approach of Wang, et al. [48], we calculate the total digital investment of enterprises as a proxy variable (Peer_Dig2) for peer digital transformation. Specifically, we sum the year-end book values of digital fixed assets and digital intangible assets disclosed in the annual financial reports of enterprises. The regression results are presented in Column (7) of Table 6. It can be observed that the impact of peer firms’ digital transformation on focal firms’ greenwashing behavior remains significantly negative, consistent with the baseline regression results. Additionally, we perform a correlation test between digital investment data and the original explanatory variable. The results show a high correlation coefficient of 0.7844, which is statistically significant at the 1% level. This confirms the robustness of the baseline regression findings.

4.3.6. Sample Replacement

First, to avoid spatial and industry self-selection biases arising from changes in location and industry, this study excludes firms that relocate geographically or switch industries during the sample period and reruns the regressions. The results, presented in columns (1) and (2) of Table 7, show that after excluding these firms, the coefficient for peer firms’ digital transformation remains significantly negative at the 1% level. Furthermore, the estimated coefficient slightly increases after the exclusion, indicating that the baseline regression is not affected by self-selection bias and that the conclusions are robust. Second, firms located in China’s four municipalities directly under the central government (Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, and Chongqing) are excluded, and the regression is rerun. As shown in column (3) of Table 7, the significant impact of peer firms’ digital transformation on corporate greenwashing behavior persists after excluding these municipalities. Finally, this study excludes the 2020–2022 sample and reruns the regression. The results, presented in column (4) of Table 7, reveal that the coefficient remains significantly negative after controlling for the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 7.

Results with sample replacement and redefining peer relationships.

4.3.7. Redefining Peer Relationships

To enhance the precision of peer definition, this study also considers a peer network based on market relationships. Following Lu, et al. [49], we calculate the digital transformation level of upstream industries for each firm using China’s Input–Output Tables. Additionally, drawing on existing literature on supply chain spillovers, we obtain data on listed firms’ suppliers and customers from the CSMAR database to construct a firm-upstream/downstream supply chain firm-year dataset. This dataset is used to examine the impact of suppliers’ digital transformation on customers’ greenwashing behavior. As shown in columns (5) and (6) of Table 7, when peers are defined as supply chain partners, the regression coefficient remains significantly negative, confirming the robustness of the baseline regression findings.

4.3.8. Double Machine Learning (DML) Model

When examining the factors influencing corporate greenwashing behavior, linear regression models assume a simple linear relationship between control variables, digital transformation, and greenwashing. This assumption may fail to account for genuine confounding factors, potentially leading to model misspecification bias. In contrast, DML, which leverages machine learning algorithms, excels at capturing nonlinear relationships [50]. This capability effectively mitigates estimation biases arising from model misspecification. Therefore, this study employs DML to conduct a robustness check on the relationship between digital transformation and corporate greenwashing behavior. The regression results of the DML approach are presented in Table 8. It is evident that regardless of whether the random forest, LASSO regression, or gradient boosting algorithm is employed, the coefficients estimated by the DML model remain negative and statistically significant at the 1% level. Furthermore, after adjusting the sample proportion, the effect of peer firms’ digital transformation on the focal firms’ greenwashing behavior persists, which once again confirms the robustness of the baseline regression results.

Table 8.

Estimation results of DML model.

4.4. Mechanism Test

4.4.1. The Impact of Digital Transformation on a Company’s Own Greenwashing

Although existing literature has demonstrated that digital transformation can inhibit greenwashing behavior in companies, this study aims to further explore and substantiate the theoretical mechanisms through which upstream digital transformation affects corporate greenwashing. Table 9 presents the results of the impact of digital transformation on greenwashing behavior. It is evident that digital transformation at the company level significantly suppresses greenwashing behavior at the 1% significance level.

Table 9.

Results of the impact of digital transformation on a company’s own greenwashing.

4.4.2. Test of Digital Transformation Spillover Among Peer Companies

Table 10, column (1), reports the impact of digital transformation among peer companies on the digital transformation of the focal company. It is observed that digital transformation among peer companies significantly promotes the digital transformation of the focal company at the 1% significance level. This indicates that the effects of digital transformation can spill over among peer companies. Consequently, a company’s greenwashing behavior is influenced not only by its own digital transformation but also by the spillover effects of digital transformation from peer firms. To further analyze the competitive nature of the spillover effects of digital transformation among peer companies, we draw on the method proposed by Peng, et al. [51] to calculate the Herfindahl Index based on revenue. Samples with a Herfindahl Index below the median are classified as belonging to highly competitive industries, while those above the median are categorized as belonging to less competitive industries. We then examine the spillover effects of digital transformation among peer companies based on these different subsamples. According to the results presented in columns (2) and (3) of Table 10, in a highly competitive industry environment, the spillover effects of digital transformation among peer companies exhibit a significant positive trend, with a greater impact than that observed in the baseline regression model. Conversely, in industries with lower levels of competition, the spillover effects of digital transformation are not statistically significant.

Table 10.

Mechanism test results.

4.4.3. Test of Greenwashing Spillover Among Peer Companies

Column (4) of Table 10 reports the impact of peer companies’ greenwashing behavior on the greenwashing behavior of the focal company. The findings reveal that peer companies’ greenwashing behavior consistently promotes the greenwashing activities of the focal company at the 1% significance level. This indicates that greenwashing behavior tends to spill over among peer companies. The theoretical analysis suggests that the spillover of greenwashing behavior among peer companies may stem from firms deliberately imitating these practices in pursuit of short-term competitive advantages. To test this hypothesis, this study uses the proportion of institutional investor holdings as a measure of a firm’s motivation to imitate and conducts a grouped regression analysis. Since institutional investors primarily focus on profitability, firms with higher institutional ownership are more likely to mimic the greenwashing behavior of their peers. Based on whether institutional ownership is above the industry average, the sample is divided into two groups: firms with strong imitation motives and firms with weak imitation motives. Columns (5) and (6) of Table 10 show that firms with higher institutional ownership (strong imitation motives) are more likely to follow their peers in engaging in greenwashing behavior.

4.4.4. Test of Industry Disclosure Quality Convergence

According to the theoretical analysis, digital transformation among other companies in the same industry may lead to a convergence effect in disclosure quality, which in turn can suppress the greenwashing behavior of the focal company. To test this mechanism, we construct a coupling model to measure the coupling degree between the KV index of peer companies and that of the focal company. This coupling degree serves as an indicator of the convergence in information disclosure quality between the focal company and its peers. The calculation formula is presented in Equation (10):

where represents the degree of convergence in information disclosure quality between the peer companies and the focal company, calculated using the coupling model. denotes the average KV index of the peer companies, excluding the focal company, while refers to the KV index of the focal company. The value of ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating a greater degree of convergence. Column (7) of Table 10 shows that an increase in the level of digital transformation among peer companies enhances the synergy in industry information disclosure quality. The industry’s digital transformation promotes the elevation of disclosure standards and norms, thereby improving the transparency and consistency of information among companies. This environment encourages firms to prioritize accurate disclosures and enhances stakeholder trust. Consequently, the greenwashing behavior of the focal company is likely to decrease, as firms in high-disclosure-quality industries are subject to stricter oversight, facing greater risks and penalties for disseminating false information.

4.5. Heterogeneity Test

4.5.1. Types of Digital Transformation

Table 11 presents five types of digital transformation among peer companies—Artificial Intelligence (Peer_IT), Big Data (Peer_BD), Cloud Computing (Peer_Cloud), Blockchain (Peer_Block), and Technology Application (Peer_Apply)—and their impact on corporate greenwashing behavior. Except for Technology Application, the other four foundational technologies show a significant negative effect on greenwashing behavior at the 1% level. From a mechanistic perspective, digital transformation facilitates the convergence of disclosure quality within the industry. The foundational technologies enhance data transparency and comparability, making it easier to assess the environmental performance of focal companies and exposing any greenwashing practices, thereby suppressing such behavior. Conversely, if Technology Application does not become deeply embedded in corporate culture, decision-making, and operational practices, it may allow greenwashing to persist. Among these technologies, Blockchain has the largest impact coefficient. Its facilitation of information sharing enhances the comparability and traceability of environmental data, increasing the risk of exposing greenwashing among focal companies. Additionally, the data sharing facilitated by Blockchain among peer companies may foster collaboration, thereby supporting the sustainable development of the industry.

Table 11.

Heterogeneity test for digital transformation types.

4.5.2. Short-Termism

Following the approach of Yu, et al. [52], we measure the short-sightedness of corporate management by analyzing the ratio of current short-term investments to total assets at the beginning of the period and conducting a grouped regression analysis. According to the results presented in columns (1) and (2) of Table 12, digital transformation among peer companies significantly suppresses greenwashing behavior only in firms with lower levels of short-sightedness. This is because companies with lower short-sightedness tend to adopt a long-term strategic perspective and possess a stronger sense of social responsibility. They are generally more focused on sustainable development and brand reputation, allowing them to respond to market expectations and regulatory pressures with greater transparency and environmental awareness in the context of their peers’ digital transformation. In contrast, companies characterized by higher short-sightedness may prioritize short-term profits and lack sensitivity to industry dynamics, resulting in a less pronounced response to the digital transformation of their peers, thereby failing to significantly suppress their greenwashing behavior.

Table 12.

Heterogeneity test of corporate myopia level and industry characteristics.

4.5.3. Industry Characteristics

First, based on the China Securities Regulatory Commission’s 2012 industry classification guidelines for listed companies, industries classified as C25–C29, C31–C32, C34–C41, I, and M are grouped as high-tech industries, while others are categorized as non-high-tech industries for regression analysis. Columns (3) and (4) in Table 12 reveal that digital transformation among peer companies significantly suppresses greenwashing behavior in high-tech industries, while no such effect is observed in non-high-tech industries. The competitive spillover effect of digital transformation is particularly evident in high-tech industries—it not only enhances corporate competitiveness but also intensifies intra-industry rivalry, prompting companies to accelerate their transformation. Moreover, high-tech firms benefit from stronger innovation capabilities and resource advantages, enabling them to proactively adjust strategies to reduce greenwashing. In contrast, non-high-tech industries face a more relaxed competitive environment and lower information flow among firms, diminishing the guiding effect of digital transformation and resulting in negligible suppression of greenwashing.

Second, referring to the methodology of Pan, et al. [53] and the Ministry of Environmental Protection’s 2008 Industry Classification Management Catalog for Environmental Verification of Listed Companies, the sample is divided into high-pollution and low-pollution industries for regression analysis. Columns (5) and (6) in Table 12 show that digital transformation among peer companies significantly suppresses greenwashing behavior in high-pollution industries, while in low-pollution industries, the coefficient is also significantly negative but notably smaller. In high-pollution industries, digital transformation improves information transparency and intensifies regulatory pressure, encouraging companies to disclose environmental measures and operational data more comprehensively. This, in turn, inspires and constrains peer companies, elevating industry-wide environmental standards and self-discipline. Such competitive effects compel companies to adopt more pragmatic operations and avoid greenwashing to maintain their reputation and market competitiveness. In contrast, low-pollution industries exhibit weaker competitive pressure and lower information transparency, limiting the influence of peer companies’ digital transformation on individual firms and thereby resulting in less pronounced suppression of greenwashing.

Finally, samples are divided into high-competition and low-competition industries based on the Herfindahl index for regression analysis. Columns (7) and (8) in Table 12 demonstrate that peer companies’ digital transformation significantly suppresses greenwashing in high-competition industries, while the effect is negligible in low-competition industries. This can be attributed to the heightened sensitivity of firms in high-competition industries to industry dynamics. Peer companies’ digital transformation enhances transparency and data sharing, strengthening mutual supervision among firms and prompting them to exercise greater caution in their greenwashing practices to avoid exposure by competitors or negative evaluations. In low-competition industries, where the motivation for greenwashing is inherently weaker, the restraining effect of peer companies’ digital transformation on greenwashing is relatively limited and hence less significant.

5. Further Analysis

5.1. The “Catfish Effect” of Digital Transformation

The previous section verifies that the digital transformation of peer enterprises significantly inhibits greenwashing behavior. However, this conclusion is based on the context of overall industry digital transformation, indicating that industry-level digital transformation plays a positive role in reducing corporate greenwashing. Then, when an enterprise with a high level of digital transformation emerges for the first time in the industry, can it exert a “catfish effect” to promote other enterprises to reduce greenwashing? Clarifying this question helps to gain an in-depth understanding of the spillover effect of digital transformation on the greenwashing behavior of peer enterprises and the industry influence of individual “pioneer” enterprises. Based on this, this study constructs the following econometric model to verify the industry “catfish effect” of digital transformation:

where is an industry-level dummy variable: if, in year , industry (to which firm belongs) sees the first emergence of an enterprise with a digital transformation degree higher than the average level of the industry sample period, is defined as 1 (and remains 1 for the industry in years after t); otherwise, it is 0. If the coefficient of is significantly less than 0, it indicates that the first appearance of a highly digitally transformed enterprise in the industry will drive down the greenwashing degree of other enterprises. Considering that the driving effect of “pioneer” enterprises may have a lag, this study lags to explore the multi-period impact of the “catfish effect” of digital transformation on greenwashing behavior.

The test results in Table 13 show that while the current-period coefficient is not significant, the impact of the emergence of a digitally transformed “pioneer” in the industry on corporate greenwashing is significantly negative in the 1st to 4th lag periods. This confirms that digital transformation indeed exerts a “catfish effect” on industry greenwashing: the appearance of a highly digitally transformed enterprise in the industry will continuously drive other enterprises to reduce greenwashing in the subsequent years. As digital transformation is accompanied by improved efficiency, increased transparency, and optimized resources, other enterprises, under imitation and competitive pressure, will reduce superficial environmental behaviors and shift toward genuine sustainable development. This process not only changes the competitive dynamics within the industry but also promotes the improvement of overall environmental standards, highlighting the key role of digitally transformed “pioneers” in industry transformation.

Table 13.

Regression results of the “catfish effect” of digital transformation.

5.2. Incremental Impact of Digital Transformed Enterprise Share Within the Industry

The previous section mainly explores the spillover effect of digital transformation on greenwashing behavior within the industry from the perspective of the average level of digital transformation of other enterprises in the same industry. However, achieving convergence in the same industry depends not only on this average level but also may be closely related to the number of enterprises that implement digital transformation in the industry. In fact, if there are a large number of digitally transformed enterprises in an industry, their successful cases and advanced practices form a positive demonstration effect, thereby further promoting the spillover effect of digital transformation. Therefore, this study constructs the following model to verify the impact of the number of digitally transformed enterprises in the same industry on greenwashing behavior:

where denotes the ratio of the number of enterprises with digital transformation to the total number of enterprises in the industry that enterprise i belongs to. Here, enterprises with digital transformation are defined as those with a digital transformation degree greater than 0. If the coefficient corresponding to is significantly less than 0, it indicates that the higher the proportion of enterprises with digital transformation in the industry, the lower the level of corporate greenwashing. Consistent with the previous section, this study further lags to explore the multi-period impact of the proportion of digitally transformed enterprises in the industry on greenwashing behavior. Since the explanatory variable in this study is the proportion of enterprises with digital transformation degree greater than 0 in the same industry, samples of such enterprises are excluded to analyze its impact more accurately. This exclusion ensures the study focuses on enterprises without digital transformation, thereby clarifying the impact of the number of digitally transformed enterprises in the same industry on the overall industry performance.

Table 14 presents the test results of the impact of the proportion of digitally transformed enterprises in the same industry on greenwashing. Although the coefficient of the current period is not significant, the coefficients of the first to fourth lag periods are all significantly negative. This shows that the higher the proportion of digitally transformed enterprises in the same industry, the lower the degree of corporate greenwashing.

Table 14.

The impact of the proportion of digitally transforming enterprises in the same industry on greenwashing.

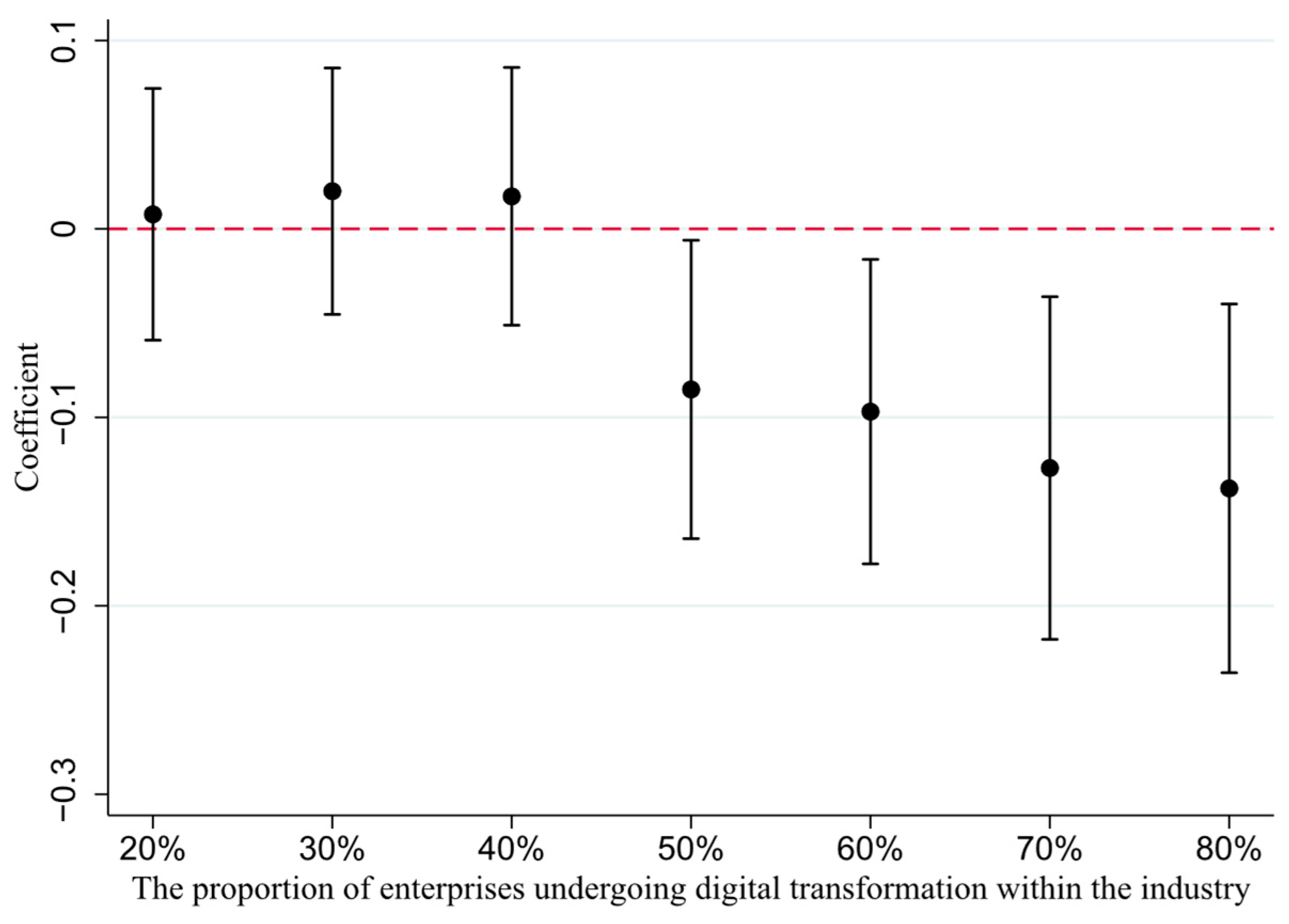

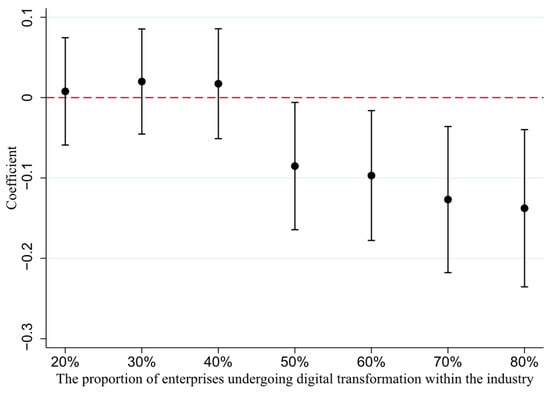

Furthermore, to further explore the threshold of industry digital transformation penetration rate required to inhibit greenwashing behavior, this study conducted tests by setting different dummy variables. Specifically, starting from 20%, if the proportion of enterprises with digital transformation in the same industry exceeds 20%, the dummy variable is set to 1; otherwise, it is set to 0. Subsequently, with a 10% increment, the study examined the impact of the dummy variable on corporate greenwashing behavior across different intervals of the industry digital transformation proportion (ranging from 20% to 80%), aiming to accurately identify its progressive effect. Figure 3 illustrates the impact of the proportion of digitally transformed enterprises on greenwashing behavior across different industries. The results show that when the proportion of digitally transformed enterprises in the same industry reaches 40%, it is still insufficient to effectively inhibit greenwashing; however, when this proportion exceeds 50%, the degree of corporate greenwashing begins to decrease significantly, with the magnitude of the decrease increasing as the proportion rises. The reason is as follows: when the proportion reaches 40%, although information transparency is improved to a certain extent, it is not enough to form universal industry consensus or mandatory standards. As a result, enterprises may still rely on vague or untrue green claims to gain market advantages. When the proportion exceeds 50%, however, the transparency, traceability, and social supervision brought about by digital transformation are significantly enhanced, making it more difficult for enterprises to evade responsibilities through greenwashing. At the same time, digital transformation at this stage often intensifies competition within the industry. To maintain their market position, enterprises need to pay more attention to practical green practices, leading to a significant reduction in greenwashing behavior. This shift reflects the critical threshold where digital transformation transitions from a quantitative change to a qualitative change.

Figure 3.

The impact of the proportion of digitally transforming enterprises in the same industry on greenwashing.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

6.1. Conclusions

Taking listed companies in China from 2009 to 2022 as the sample, this paper studies the impact of peer firms’ digital transformation on focal firms’ greenwashing behavior from the perspective of institutional theory. The results show that peer firms’ digital transformation can significantly inhibit focal firms’ greenwashing behavior, and this effect is exerted through three pathways: the competitive peer spillover effect of digital transformation, the inhibitory peer spillover effect of greenwashing behavior, and the convergence effect of industry information disclosure quality. Meanwhile, the inhibitory effect is more significant in industries with extensive application of underlying digital technologies, low short-termism tendency, high-tech attributes, high pollution levels, and high competition intensity. Further analysis reveals that the first highly digitized enterprise in the industry will generate a “catfish effect”, and when the proportion of digitized enterprises in the industry exceeds 50%, the inhibitory effect is significantly enhanced.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

We offer three key theoretical contributions to the existing research. First, we enrich the theoretical framework of factors influencing greenwashing: The three new transmission mechanisms break through the limitations of traditional studies focusing on firm-specific characteristics or macro environments, incorporate industry peer interactions into the analysis, supplement the explanatory power of legitimacy theory and stakeholder theory at the industry level, and reveal the industry collaborative pathway for greenwashing governance.

Second, we expand theoretical cognition of the spillover effects of digital transformation. Through the two propositions of the “catfish effect” and threshold effect, the impact of digital transformation is extended from individual firms to the dynamic evolution of the industry ecosystem. This deepens the understanding of the “industry-level governance effect” of digital transformation and provides a new empirical scenario for peer effect theory.

Third, we clarify the boundary conditions of digital governance. The threshold effect proposition quantifies the critical conditions for industry digital governance for the first time, providing a new theoretical perspective for understanding the interaction between digital technology and the industry ecosystem and offering empirical evidence for the “formation conditions of normative pressure” in institutional theory.

6.3. Practical Implications

We propose several recommendations for enhancing digital transformation and governance at various levels. First, for enterprises: Prioritize foundational digital technologies (AI, big data, blockchain—proven most effective in curbing greenwashing, Section 4.5.1) to build traceable environmental data systems (e.g., real-time emission tracking). Firms should actively benchmark digital leaders (industry “pioneers” with digital levels above the 75th percentile, Section 5.1): establish quarterly peer-learning sessions to replicate their automated environmental reporting and third-party audit mechanisms, especially critical for high-short-termism firms (Section 4.5.2) to avoid profit-driven greenwashing.

Second, for industries: Accelerate peer digital diffusion by mandating digital pioneers to share anti-greenwashing tools (e.g., cloud-based environmental management platforms) with 10–15 SMEs yearly—activating the “catfish effect” (Section 5.1) to push industry digital penetration across the 50% threshold (Section 5.2). For high-pollution sectors (where digital suppression of greenwashing is strongest, Section 4.5.3), set a 3-year timeline to reach this threshold via subsidized SME access to digital tools.

Third, for regulators: Leverage peer digital diffusion by tying supervision to industry digital traits. For high-tech/high-pollution industries (Section 4.5.3), mandate monthly digital disclosure of key environmental indicators (e.g., carbon emissions) via official platforms, with penalties for non-compliance doubled. Use industry-average idiosyncratic stock returns (Section 4.2.3) to identify high-greenwashing-risk industries, then deploy blockchain audits targeting firms with below-average peer digital levels—ensuring supervision aligns with empirical risk factors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.X. and R.L.; methodology, J.X. and R.L.; software, J.X. and Z.P.; validation, R.L.; formal analysis, R.L. and Z.P.; investigation, J.X. and Z.P.; resources, J.X.; data curation, J.X. and Z.P.; writing—original draft preparation, R.L.; writing—review and editing, J.X. and R.L.; visualization, J.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in FigShare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30498380.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the anonymous referees who provided valuable comments and suggestions to significantly improve the quality of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jin, X.; Zuo, C.; Fang, M.; Li, T.; Nie, H. Measurement problem of enterprise digital transformation: New methods and findings based on large language models. China Econ. 2025, 20, 70–95. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Li, Y.; Feng, C. Green innovation peer effects in common institutional ownership networks. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 641–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Cui, C.; Chen, X.; Xiu, P. How can regional integration promote corporate innovation? A peer effect study of R&D expenditure. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Lian, Y.; Forson, J.A. Peer effects in R&D investment policy: Evidence from China. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2021, 26, 4516–4533. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Shi, Z.; He, C.; Lv, C. Peer effects on corporate R&D investment policies: A spatial panel model approach. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 158, 113667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Huang, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, D. ESG peer effects and corporate financial distress: An executive social network perspective. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2025, 30, 2284–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Wang, H. The industry peer effect of enterprise ESG performance: The moderating effect of customer concentration. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2024, 92, 1499–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Lou, J.; Hu, H. Peer effect of enterprise digital transformation in the network constructed by supply chain common-ownership. China Ind. Econ. 2023, 4, 136–155. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wan, M. Research on peer effect of enterprise digital transformation and influencing factors. Chin. J. Manag. 2021, 18, 653–663. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, X.; Zeng, G.; Sun, X. The peer effect of digital transformation and corporate environmental performance: Empirical evidence from listed companies in China. Econ. Model. 2023, 128, 106515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Guo, X.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Z. Research on the mechanism by which digital transformation peer effects influence innovation performance in emerging industries: A case study of China’s photovoltaic industry. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0313615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.; Li, J.; Xiao, L. Hear all parties: Peer effect of digital transformation on long-term firm investment in China. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2024, 45, 1242–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seele, P.; Gatti, L. Greenwashing revisited: In search of a typology and accusation-based definition incorporating legitimacy strategies. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrone, P.; Fosfuri, A.; Gelabert, L. Does greenwashing pay off? Understanding the relationship between environmental actions and environmental legitimacy. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 144, 363–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Dagestani, A.A. Greenwashing behavior and firm value–From the perspective of board characteristics. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2023, 30, 2330–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.T.; Raschke, R.L. Stakeholder legitimacy in firm greening and financial performance: What about greenwashing temptations? J. Bus. Res. 2023, 155, 113393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Duan, D.; Tang, P.; Yang, S. Greenwashing or brownwashing? Green bond issuance and corporate environmental decoupling. Appl. Econ. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Qian, H.; Wu, Q.; Han, F. Research on the masking effect of vertical interlock on ESG greenwashing in the context of sustainable Enterprise development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Environmental regulation and firm product quality improvement: How does the greenwashing response? Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 80, 102058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Wu, P.; Hou, L. Social media attention and corporate greenwashing: Evidence from China. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 5446–5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zioło, M.; Bąk, I.; Spoz, A. Literature review of greenwashing research: State of the art. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 5343–5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Huong, N.T.T.; Nam, N.H.; Nga, N.T.T.; Thanh, C.T. Greenwashing behaviours: Causes, taxonomy and consequences based on a systematic literature review. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. (JBEM) 2020, 21, 1486–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Li, Y. Does corporate engagement in digital transformation influence greenwashing? Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Pan, Z.; Zhang, K.; Ji, F. The effect of digitalization transformation on greenwashing of Chinese listed companies: An analysis from the dual perspectives of resource-based view and legitimacy. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1179419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lai, Y.; Zhang, S. Greening by digitization? Exploring the effect of enterprise digital transformation on greenwashing. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 6616–6639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nygaard, A.; Silkoset, R. Sustainable development and greenwashing: How blockchain technology information can empower green consumers. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 3801–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Tao, L.; Li, C.B.; Wang, T. A path analysis of greenwashing in a trust crisis among Chinese energy companies: The role of brand legitimacy and brand loyalty. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torelli, R.; Balluchi, F.; Lazzini, A. Greenwashing and environmental communication: Effects on stakeholders’ perceptions. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 407–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brynjolfsson, E.; McAfee, A. The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies; WW Norton & Company: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, F.; Liu, T.; Xue, Q.; Liu, N. Peer effects of digital innovation behavior: An external environment perspective. Manag. Decis. 2023, 61, 2173–2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.K.; Chung, J.Y. Brand popularity, country image and market share: An empirical study. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 1997, 28, 361–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Burbano, V.C. The drivers of greenwashing. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 54, 64–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikhchandani, S.; Hirshleifer, D.; Welch, I. A theory of fads, fashion, custom, and cultural change as informational cascades. J. Political Econ. 1992, 100, 992–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Xie, X.; Zhou, H. ‘Isomorphic’ behavior of corporate greenwashing. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2022, 20, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, M.; Matthews, L.; Guo, H. Digital transformation and environmental information disclosure in China: The moderating role of top management team’s ability. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2024, 33, 8456–8470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, J. Digital transformation, environmental disclosure, and environmental performance: An examination based on listed companies in heavy-pollution industries in China. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2023, 87, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Teng, L.; Arkorful, V.E.; Hu, H. Impacts of digital government on regional eco-innovation: Moderating role of dual environmental regulations. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 196, 122842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzpeyma, Z.; Bozorgmehriyan, S.; Bandariyan, A. The Effect of product market competition on Environmental Information Disclosure with Emphasis on the Role of Management Ability. J. Account. Manag. Vis. 2022, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Grennan, J. Dividend payments as a response to peer influence. J. Financ. Econ. 2019, 131, 549–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Hu, H.; Lin, H.; Ren, X. Enterprise digital transformation and capital market performance: Empirical evidence from stock liquidity. Manag. World 2021, 37, 130–144. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, C.; Xiao, T.; Geng, C.; Sheng, Y. Digital transformation and division of labor between enterprises: Vertical specialization or vertical integration. China Ind. Econ. 2021, 9, 137–155. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Peng, Y.; Zhou, T. The Impact of Supply Chain Innovation and Application Policies on Supply Chain Digitalization. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2025, 61, 3308–3331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith-Pinkham, P.; Sorkin, I.; Swift, H. Bartik instruments: What, when, why, and how. Am. Econ. Rev. 2020, 110, 2586–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]