Abstract

Digital platforms face a fundamental strategic decision between subscription-only, advertising-only, and freemium (hybrid) monetization models. We develop a game-theoretic framework that unifies these strategies, explicitly modeling consumer heterogeneity in both willingness-to-pay and advertising disutility, while incorporating network effects through the platform’s valuation of user-base size. Our analysis yields closed-form solutions identifying optimal strategy thresholds based on advertising market conditions. We show that subscription-only dominates when advertising prices are low, advertising-only prevails when prices are high, and freemium emerges as strictly optimal in the intermediate region. Under freemium, we demonstrate strategic complementarity: both subscription fees and advertising intensity exceed their levels in pure strategies because each instrument’s effectiveness is amplified by the other through user reallocation across tiers. Network effects universally reduce monetization intensity but alter instruments’ relative sensitivities differently across regimes—when advertising prices are moderate, freemium adjusts ad length more aggressively, while the opposite holds at high prices. Critically, freemium’s profitability requires sufficient consumer heterogeneity in ad tolerance. As consumer preferences converge, the screening mechanism fails and freemium collapses to the superior pure strategy. These results provide operational guidance for platform monetization decisions and clarify when hybrid models create value beyond traditional approaches.

1. Introduction

Digital platforms face a foundational strategic decision: how to monetize user participation while preserving the network effects that sustain their competitiveness [1]. This choice has profound implications for platform performance, with monetization strategy directly affecting user acquisition costs, lifetime value, and market position. Competing platforms have adopted markedly different approaches—some depend exclusively on subscription revenues, others rely almost entirely on advertising, and an increasing number employ hybrid “freemium” models that combine a free ad-supported tier with a paid ad-free option [2]. Netflix, for example, built its business on a subscription-only model, recently experimenting with lower-priced ad-supported plans [3]. In contrast, platforms such as Facebook and TikTok continue to depend predominantly on advertising revenues, leveraging scale and user engagement to attract advertisers [4]. Spotify and YouTube Premium illustrate the freemium model, where the majority of users remain on the free tier while a significant minority subscribe for ad-free access. These contrasting strategies underscore a central dilemma: how should a platform balance the predictable revenues of subscription against the scale advantages and indirect value of advertising-supported access?

The challenge in designing a monetization strategy lies in reconciling two conflicting forces that shape platform performance. Users differ markedly in how they perceive advertising—some view it as a tolerable trade-off for free access, while others experience significant disutility and are willing to pay to avoid it. At the same time, the value of most digital platforms expands with user participation: larger networks amplify engagement, generate richer data, and attract more advertisers, reinforcing a cycle of growth. These intertwined dynamics create a structural tension. An advertising-based model promotes rapid diffusion by lowering entry barriers but risks alienating ad-averse consumers. A subscription-based model secures stable revenues yet constrains participation to paying users, limiting the strength of network effects. The freemium model emerges as a strategic compromise, allowing heterogeneous users to self-select—monetizing some through payments and others through exposure—thus balancing scale with revenue extraction.

This study examines the optimal design of platform monetization under heterogeneous consumer preferences and network effects. We develop a game-theoretic model of a monopolistic platform that serves consumers differing in both their willingness to pay and their disutility from advertising, while the platform simultaneously benefits from an expanding user base through demand-side network effects. Within this framework, we address three central questions. First, under what conditions is each monetization regime—advertising-only, subscription-only, or freemium—profit-maximizing? Second, how should the platform jointly determine subscription price and advertising intensity within each regime? Third, how do consumer heterogeneity and network effects interact to shape the relative profitability and equilibrium design of these regimes?

Our analysis generates several key insights into how digital platforms should monetize heterogeneous users in the presence of network effects. First, we derive explicit threshold conditions that determine which monetization regime—subscription-only, advertising-only, or freemium—maximizes platform profit. When the advertising market is weak, subscription-only dominates; when it is strong, advertising-only prevails; and for intermediate conditions, freemium emerges as optimal by segmenting users according to their ad tolerance. Second, we show that in the freemium regime, subscription pricing and advertising intensity are strategic complements. The platform optimally sets both instruments at higher levels than in single-revenue models, since increasing one amplifies the effectiveness of the other by reallocating marginal users across tiers. This complementarity explains why hybrid monetization can outperform pure models even without new demand creation. Third, the platform’s valuation of its user base—reflecting network externalities and long-term engagement—shapes how aggressively it monetizes users. A higher user-base value induces lower prices and shorter ads to expand participation, but the relative sensitivity of these adjustments varies across regimes. Network effects therefore not only shift the level of optimal instruments but also reshape their comparative trade-offs. Finally, we demonstrate that the profitability of freemium critically depends on consumer heterogeneity in ad aversion. When users differ substantially in their disutility from ads, freemium effectively screens them into paying and ad-supported segments, extracting surplus from both. As consumers become more homogeneous, this screening advantage vanishes, and freemium converges to the better of the two pure regimes.

By integrating these forces—consumer heterogeneity, ad-market conditions, and network effects—into a unified framework, this paper advances the theory of platform monetization and offers actionable insights for digital managers. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related literature and identifies the research gap. Section 3 presents the model setup and key decision variables. Section 4 develops the analytical results, deriving threshold conditions, comparative statics, and welfare implications. Section 5 concludes with theoretical and managerial insights.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Advertising–Subscription Trade-Off

A central theme in platform economics concerns the trade-off between advertising- and subscription-based monetization. Anderson and Coate (2005) [5] establishes the canonical framework showing that ad-supported broadcasters may provide inefficiently high or low ad levels depending on viewers’ nuisance costs and the informational value of ads, while introducing subscription fees shifts this balance toward more efficient allocations. Armstrong (2006) [6] extends this logic to two-sided competition, demonstrating that strong advertising demand can justify subsidizing or eliminating user prices, as advertiser revenues cross-subsidize consumer access. This rationale underpins the prevalence of ad-supported platforms such as television, news media, and social networks. Subsequent work refines this analysis by incorporating dynamic user responses and strategic interaction between content and advertising markets. Lambrecht and Misra (2017) [7], for instance, show that firms should expand rather than restrict free content in high-demand periods—a counter-cyclical policy that maximizes total revenue when user heterogeneity varies over time. Together, these studies reveal that price and ad exposure are strategic complements: lowering access barriers increases audience size and advertising revenues, while excessive monetization through either channel reduces engagement and long-term value.

Recent research extends this trade-off to welfare and quality considerations. Ichihashi and Kim (2023) [8] demonstrates that competition among “addictive platforms” can reduce service quality as firms exploit attention-maximizing features, whereas subscription models mitigate this tendency by weakening reliance on advertising. Chatterjee and Zhou (2021) [9] shows that native advertising can enhance welfare when moderate consumer disliking balances engagement and advertiser value. Zhu et al. (2025) [10] empirically illustrates how monetization reshapes ecosystem composition: Goodreads’ shift to paid participation increased revenues but reduced content diversity, producing “rich-get-richer” dynamics. Collectively, this stream highlights that monetization choices influence not only revenue allocation but also product quality, consumer welfare, and long-term market evolution.

2.2. Freemium Strategies and Network Externalities

The freemium model—offering both free and premium tiers—has become a dominant hybrid monetization approach, combining the scale advantages of advertising with the revenue stability of subscriptions. Niculescu and Wu (2014) [11] provides foundational analysis of freemium designs, showing that their effectiveness relies on balancing two economic mechanisms: learning and screening. The learning effect operates as free users interact with the product, gain familiarity, and become more inclined to upgrade to the premium tier. The screening effect ensures that only consumers with sufficiently high valuations choose the premium option, allowing the firm to extract greater surplus from this segment. Their results suggest that the optimal free version should retain roughly 40–60% of premium functionality to avoid cannibalization while enabling conversion, establishing a benchmark for later studies. Building on this literature, Shi et al. (2019) [12] further demonstrates that freemium becomes optimal only when network effects are asymmetric across tiers—specifically, when premium users benefit more from user-base expansion than free users.

Empirical work further reveals several behavioral mechanisms that shape freemium conversion. Gu et al. (2018) [13] conducts a randomized field experiment and finds that adding additional premium options increases demand for an existing premium product. Their analysis identifies two well-known choice phenomena: the compromise effect, in which consumers gravitate toward a middle option when it is positioned between a low-end and a high-end alternative, and the attraction effect, in which the presence of a clearly inferior or superior option makes another option appear more appealing by comparison. Koch and Benlian (2017) [14] examines two free sampling strategies—“free-first,” where users try the free version before sampling premium, and “premium-first,” where they experience the premium version first—and shows that premium-first trials yield higher conversion rates. This pattern is consistent with the idea that users become reluctant to give up higher-quality experiences once they have been exposed to them, a form of aversion to quality losses. Li et al. (2019) [15] similarly demonstrates that offering high-quality free samples can enhance rather than cannibalize sales, particularly for popular content. Collectively, these studies indicate that freemium outcomes depend on behavioral learning, context-dependent choice, and network feedbacks, suggesting that optimal designs must integrate both economic and psychological drivers of conversion.

2.3. Heterogeneous Ad Aversion and Platform Pricing Design

Consumer heterogeneity in advertising tolerance and content valuation fundamentally determines the optimal monetization structure. Dubé and Misra (2023) [16] provides large-scale experimental evidence that personalized pricing can raise profits by up to 86% relative to static pricing, though it redistributes rather than uniformly increases consumer surplus. Joshi and Musalem (2021) [17] models heterogeneity in both content valuation and ad-nuisance cost, showing that advertising intensity can serve as a screening mechanism that nudges marginal consumers toward paid tiers—linking ad exposure directly to self-selection. Consistent with this, Sato (2019) [18] proves that binary menus (free and premium) are optimal among feasible price–ad combinations, with premium prices targeting the upper quartile of the ad-aversion distribution. These insights collectively establish ad aversion as a structural basis for segmentation and as a primary driver of hybrid-model profitability.

At the same time, heterogeneity in ad sensitivity interacts with privacy concerns and targeting precision. Goldfarb and Tucker (2011) [19] shows that while targeting and ad obtrusiveness each increase purchase intent independently, their combination reduces it due to heightened privacy concerns—especially in sensitive categories such as health or finance. Johnson (2013) [20] complements this view, showing that improved targeting increases engagement among high-interest consumers but also accelerates avoidance among low-interest ones, thereby reducing total impressions. This tension between personalization and reach defines the platform’s equilibrium mix of advertising, subscription, and freemium offerings. The resulting design problem is not merely one of revenue maximization but of welfare and governance, as monetization intensity directly shapes user experience, market reach, and the sustainability of digital ecosystems.

2.4. Research Gaps

Despite extensive research on platform monetization, prior studies typically analyze individual mechanisms—advertising, subscription, or freemium—in isolation, offering only partial insights into their relative performance. Most models treat advertising prices, network effects, and consumer heterogeneity separately, without integrating them into a unified analytical structure. As a result, we lack a clear understanding of when each strategy dominates and how these forces interact to shape optimal pricing and advertising decisions. Existing empirical and theoretical works also provide limited guidance on how a platform’s valuation of its user base—reflecting network externalities and long-term engagement—alters monetization intensity across regimes. Moreover, while consumer heterogeneity in ad tolerance is widely recognized as critical, prior studies rarely quantify its interaction with ad-market strength in determining regime dominance. This study addresses these gaps by developing a tractable framework that explicitly links ad-market conditions, user-base value, and heterogeneity in ad aversion, deriving closed-form threshold conditions for the optimal choice among subscription, advertising, and freemium strategies, and clarifying the comparative statics that govern their equilibrium outcomes.

3. Models

We consider a monopolistic firm operating an online platform that faces three alternative monetization strategies: (i) a subscription-only strategy, (ii) an advertising-only strategy, and (iii) a freemium (hybrid) strategy. Under the subscription-only strategy, the firm charges a fixed subscription fee p and provides ad-free access. Under the advertising-only strategy, the service is offered free of charge, but consumers must watch an advertising clip of length x before accessing the service. Finally, under the freemium strategy, both options are simultaneously available: consumers can either pay the subscription fee or watch an advertising clip. The firm’s objective is to select a strategy and determine the optimal design parameters to maximize overall revenue, balancing direct monetary returns with the strategic value of user-base expansion.

It is worth noting that real-world platforms often employ additional monetization variants such as feature-limited free tiers (e.g., reduced quality, limited functionality) or mixed plans that combine a lower subscription fee with partial advertising. To maintain analytical tractability and to isolate the core trade-offs between pure subscription, pure advertising, and their combination, our model does not incorporate these intermediate or downgraded options. These richer menu-design problems represent natural extensions of our framework and offer promising directions for future research.

Consumers are heterogeneous along two dimensions: their valuation for the service (which is equivalent to willingness-to-pay) and their tolerance for advertising. We model valuation as a random variable , and use v to denote a consumer’s realized valuation. Under the subscription-only strategy, all consumers with subscribe, implying that the demand share is .

Advertising tolerance is captured by a disutility parameter , with . This parameter represents the perceived monetary equivalent of inconvenience per unit ad length, consistent with evidence that consumers are heterogeneous in ad-avoidance behavior. A fraction of consumers are of the low-disutility type , while the remaining fraction are of the high-disutility type . A consumer with valuation v and disutility accepts the ad-supported option if and only if ; otherwise, she refrains from participation. This formulation captures the intuition that ad-tolerant consumers remain active even when ads are relatively long, whereas ad-sensitive consumers either exit or, when available, switch to the subscription option.

The firm generates advertising revenue from external advertisers, who pay a unit price per unit length of ad delivered. Thus, if a consumer watches an ad of length x, the firm earns revenue . Importantly, the same decision variable x simultaneously drives consumer disutility () and advertising income (), highlighting the central trade-off between consumer participation and ad revenue.

Beyond direct revenues, the firm benefits strategically from user-base expansion through network externalities, data accumulation, and long-term engagement. Let denote the per-unit value of consumer participation. We assume that the firm’s user-base value grows quadratically with the number of consumers served:

This assumption captures the increasing marginal contribution of additional users, consistent with the observation that large platforms often adopt aggressive acquisition strategies (e.g., free trials, ad-supported entry) to accelerate network growth. While alternative functional forms (e.g., linear or concave growth) could be considered, the quadratic form emphasizes the convexity of network value creation that is most salient in early-stage platform competition.

3.1. Consumer’s Problem

When a consumer arrives at the platform, the consumer observes the firm’s offer, which may include a subscription fee p, an advertising length x, or the availability of both options, depending on the monetization strategy. In the freemium case, the consumer can choose between paying the subscription fee or watching an advertisement. Based on this information, the consumer decides whether to use the service and, if so, whether to pay the subscription fee or watch an advertisement. The consumer’s decision depends on two individual characteristics: the consumer’s valuation and the disutility from advertising with . The outside option of not using the service yields normalized utility zero.

If the firm adopts the subscription-only strategy, a consumer who pays the fee obtains utility

Participation in this case requires that the consumer’s valuation exceeds the subscription fee. Under the advertising-only strategy, the utility for a type-i consumer is

where the net benefit depends on the trade-off between the value of the service and the perceived cost of enduring advertising. Finally, under the freemium (hybrid) strategy, the consumer chooses between the two options and selects the one that provides the highest payoff:

This structure captures the essential self-selection mechanism that arises from consumer heterogeneity. Consumers with high valuations but strong aversion to advertising () tend to subscribe if their valuation exceeds the fee. By contrast, consumers who are more tolerant of advertising () but less willing to pay are more likely to watch the advertisement, provided that the ad length is not excessively costly relative to their valuation. The freemium strategy leverages this heterogeneity by segmenting the market endogenously: ad-sensitive consumers generate subscription revenue, while ad-tolerant consumers contribute to advertising revenue.

This structure illustrates the essential self-selection mechanism that arises from consumer heterogeneity. Consumers with high valuations but strong aversion to advertising () tend to subscribe whenever their valuation exceeds the subscription fee. By contrast, consumers who are more tolerant of advertising () but have lower valuation are more likely to watch advertisements, provided that the implied cost does not exceed their valuation. The freemium strategy leverages this heterogeneity by endogenously segmenting the market: ad-sensitive consumers contribute to subscription revenue, while ad-tolerant consumers generate advertising revenue.

3.2. Firm’s Problem

The firm determines the subscription fee and the advertising length in order to maximize overall revenue, given the parameters and A. The objective function consists of two direct revenue sources—subscription payments and advertising income—and an additional component that reflects the strategic value of the consumer pool. This last component is modeled as a monetary proxy for long-run benefits of consumer participation, such as stronger network effects, richer data accumulation, and enhanced market presence.

When the firm commits to a single mechanism—either the subscription-only or the advertising-only strategy—the objective simplifies accordingly. Under the subscription-only strategy, revenue is generated from consumers whose valuation exceeds the fee, augmented by the user-base value associated with their participation. Under the advertising-only strategy, revenues are obtained from advertiser payments proportional to the ad length and participation rates, again complemented by the user-base value. The corresponding objective functions can therefore be expressed as follows:

For the subscription-only strategy, consumers participate only if their valuation exceeds the subscription fee . With , the fraction of paying consumers is , yielding subscription revenue of . In addition, the user-base effect contributes . The firm’s objective function under this strategy is therefore

For the advertising-only strategy, participation depends on whether . Aggregating across types, the expected participation rate is , where . Advertising revenue is thus , while the user-base effect contributes . The firm’s objective function is

For the freemium (hybrid) strategy, the platform offers both access modes simultaneously: a subscription option with fee p and an ad-supported option with advertising length x. Consumers self-select between the two modes based on their valuation and ad tolerance. A type- consumer chooses the ad-supported option whenever , while a type- consumer subscribes whenever and . Accordingly, the participation shares are

where denotes the fraction of ad-supported users and denotes the fraction of subscribers.

The platform collects subscription revenue from subscribing users and advertising revenue from ad-supported users, and it also benefits from the user-base value generated by the total number of participants. The objective function for the freemium strategy is therefore

4. Analysis

We begin the analysis by examining the firm’s optimal decisions under the two pure monetization regimes—subscription-only and advertising-only. These baseline cases isolate the economic forces associated with each instrument in its standalone form, allowing us to understand how pricing and advertising intensity respond to the model’s key parameters when they do not interact. Lemma 1 therefore derives the optimal subscription fee and advertising length under the two pure strategies, establishing the foundation for the comparative and threshold analysis of the freemium design that follows. All proofs are provided in Appendix A.

Lemma 1.

Optimal decision under pure strategies. The firm’s optimal decisions under the subscription-only and advertising-only strategies are as follows.

- (a)

- Subscription-only strategy.

- (b)

- Advertising-only strategy. If both consumer types participate, the optimal advertising length isIf only the low-disutility type remains active, the optimal advertising length is

The results highlight the central role of the user-base value () and the advertising price (A) in shaping the firm’s monetization policy. Under the subscription-only strategy, when the platform optimally sets the fee to zero, effectively offering the service for free. This outcome reflects the dominance of user-base value over direct subscription revenue, as expanding participation generates higher marginal benefits than charging a positive price.

In the advertising-only strategy, the firm balances the advertising revenue generated from longer clips against the risk of losing high-disutility consumers. When A is relatively low or the heterogeneity ratio is moderate, the revenue gain from lengthening the advertisement is limited, while the cost of excluding high-disutility users is substantial. As a result, the firm chooses the shorter advertising length that keeps both consumer types active.

However, when A becomes large and the market is highly heterogeneous (i.e., is large), the firm has stronger incentives to extend the advertising length to . A larger heterogeneity gap means that high-disutility users drop out even with modest increases in ad length, while low-disutility users tolerate a much wider range of x. Thus, the marginal revenue from extracting longer ad viewing time from the low-disutility segment outweighs the marginal loss from losing the high-disutility group. This logic explains why sacrificing the consumers can become optimal.

The population shares and further shape this trade-off. When the low-disutility segment is sufficiently large, focusing exclusively on that group becomes more profitable. Conversely, when the high-disutility segment is sizable, excluding them leads to a significant loss in reach, making shorter advertisements more attractive.

The threshold condition

captures the precise balance of these forces by identifying the advertising-price level at which the firm is indifferent between retaining both groups and excluding the high-disutility consumers. Larger shifts the threshold upward because the value of broader participation increases; higher A or greater heterogeneity lowers it by strengthening the incentive to prioritize ad extraction from the low-disutility segment.

Finally, note that the subscription-only and advertising-only models yield identical profits precisely when , i.e., when the advertising price equals the average disutility of viewing ads. This equivalence underscores the substitutability between direct pricing and ad-based monetization, while network considerations tilt the platform toward lower subscription fees or shorter ad lengths whenever user-base effects are significant.

4.1. Optimal Strategy

Lemma 1 characterizes the firm’s optimal pricing and advertising choices when restricted to a single monetization strategy. While these results provide useful benchmarks, the firm ultimately faces the higher-level question of which strategy to adopt. This decision hinges on the relative importance of advertising revenues and user-base value: the advertising price A captures the external market valuation of user attention, whereas measures the platform’s internal benefit from expanding participation. The interplay between these two forces determines whether a subscription-only, advertising-only, or freemium design maximizes firm profit.

Proposition 1 (Optimal strategy). The firm’s optimal strategy is characterized as follows. Define two thresholds

- (i)

- If , the firm optimally implements a subscription-only policy.

- (ii)

- If , the firm adopts a freemium policy: both a finite subscription fee and a finite advertising length are offered, and consumers self-select between paying and watching.

- (iii)

- If , the firm switches to an advertising-only policy.

Table 1 summarizes the corresponding optimal fee, ad length, and revenues for each region.

Table 1.

Optimal decisions and revenues by strategy region.

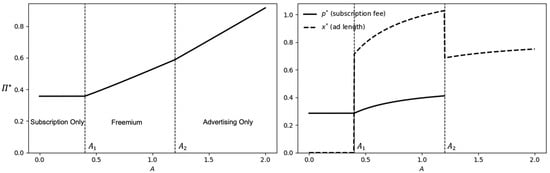

Proposition 1 delivers a clean threshold-based characterization of the firm’s monetization choice. Two cutoffs, and partition the advertising price A into three distinct regions where subscription-only, freemium, or advertising-only emerges as the optimal strategy. This result provides both analytical clarity and operational guidance, as summarized in Table 1. Figure 1 visually illustrates these regions and the corresponding revenue profiles.

Figure 1.

Optimal strategy and revenue. (Parameters: , , , ).

The lower cutoff reflects the minimum advertising price needed to keep even the most ad-tolerant consumers () willing to watch ads. If , any positive ad length generates insufficient revenue relative to the participation loss it induces, making subscription-only the preferred strategy. The optimal subscription fee depends on the user-base value : when the platform charges a positive fee, whereas when it optimally subsidizes access and sets the fee to zero, illustrating the substitutability between direct pricing and the indirect value generated by a large user base.

For intermediate values , neither pure strategy dominates and the freemium design becomes strictly optimal. In this region, the ad price is high enough for advertising to be profitable, but not so high that it is optimal to exclude the high-disutility segment. The two instruments interact through the condition : subscribers (type ) and ad-watchers (type ) coexist in equilibrium, each choosing the option that maximizes individual utility. Comparative statics reveal that and increase in A—reflecting the rising value of consumer attention—and decrease in , since stronger network effects encourage the firm to soften monetization to maintain participation.

The upper cutoff identifies the point at which the advertising market becomes so lucrative that the subscription channel is no longer needed. Formally, is obtained by equating the freemium profit with the advertising-only profit and solving for the value of A that makes the platform indifferent between retaining both instruments and relying solely on advertising. Economically, is the advertising price at which the marginal gain from lengthening ads on the ad-tolerant users exceeds the marginal loss from excluding the high-disutility users. When , intensifying advertising on the low-disutility segment delivers higher returns than maintaining segmentation through a positive subscription fee.

A key feature is that depends on consumer heterogeneity—, , and their population shares —but not on the user-base value . Greater heterogeneity (larger ) or a larger ad-tolerant segment lowers the attractiveness of preserving the high-disutility users, thereby reducing . In contrast, the transition between subscription-only and freemium () depends solely on the tolerance of the low-disutility type. This asymmetry highlights that lower-threshold adoption of advertising is governed by the most tolerant users, whereas the upper-threshold shift to ad-only is governed by the profitability of abandoning the least tolerant users.

4.2. Comparative Statics of Pricing and Advertising Decisions

Having established in Proposition 1 how the firm’s strategy choice depends on the advertising price A, we next examine how the intensity of instruments differs across regimes. The threshold analysis clarifies which strategy dominates in each region, but it does not address how the fee and advertising length in the freemium regime compare with those under the pure strategies. This distinction is important because the freemium design combines two instruments simultaneously, and its profitability stems not only from the coexistence of fee and ads but also from the fact that both can be applied more aggressively than in isolation. Proposition 2 formalizes this comparative property, showing that the optimal fee and advertising length under the freemium strategy are always at least as large as their counterparts in the pure subscription-only and advertising-only regimes.

Proposition 2.

Comparative intensity of instruments under freemium strategy

Under any advertising price A, the firm’s optimal instruments in the freemium regime are weakly higher than those in the pure strategies. Formally,

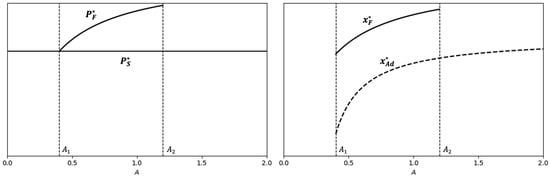

Proposition 2 highlights how the freemium (hybrid) design systematically intensifies both pricing and advertising relative to the corresponding pure strategies. Figure 2 illustrates these relationships.

Figure 2.

Comparative intensity of pricing and advertising instruments under the freemium strategy. (Parameters: , , , ).

In the subscription-only regime, the firm sets the optimal fee by balancing direct subscription revenue against the user-base value , while no advertising is provided (). In contrast, in the freemium regime the subscription fee is never lower than . The availability of an advertising alternative allows the platform to raise the subscription price without fully losing marginal users: ad-tolerant consumers can switch to the advertising channel rather than exit. This cushions participation losses and enables greater surplus extraction from ad-averse () consumers.

A similar mechanism operates on the advertising side. In the pure advertising-only regime, the firm chooses to balance advertising revenue against user attrition. Under freemium, however, ad-averse consumers can avoid ads by paying the subscription fee. This safety valve allows the platform to lengthen advertisements without losing its entire user base, which in turn makes greater than or equal to . When the ad market becomes extremely profitable (), the optimal freemium solution collapses to the advertising-only benchmark because subscription no longer plays a meaningful role. In contrast, within the freemium region, both instruments are simultaneously active and set more aggressively than under either pure strategy, enabling the firm to extract revenue from ad-averse subscribers and ad-tolerant viewers at the same time.

Overall, this result underscores the strategic complementarity of the freemium design. By differentiating purchase modes, the platform raises fees for subscribers and extends ads for tolerant users, thereby expanding the revenue frontier beyond what either pure strategy could achieve in isolation. The additional gains arise precisely from exploiting consumer heterogeneity rather than serving a single representative type.

4.3. Impact of User-Base Value

The previous analysis emphasized how external market conditions, captured by the advertising price A, determine the platform’s strategy choice and the intensity of its instruments. We now turn to the role of the platform’s internal valuation of its user base, . This parameter reflects the importance of network externalities, data accumulation, and other long-run benefits of attracting additional users. Intuitively, a larger makes consumer participation more valuable, leading the platform to moderate both its subscription fee and its advertising length to sustain engagement. Proposition 3 formalizes this comparative static result, showing not only that both instruments decline in , but also that the sensitivity of advertising length differs across regimes depending on the strength of the advertising market.

Proposition 3.

Comparative statics with respect to

Both the optimal subscription fee and the optimal advertising length decrease with the platform’s valuation of the user base δ. Moreover, the relative sensitivity of advertising length to δ depends on the advertising price. In particular, there exists a threshold such that

and

Proposition 3 establishes that a stronger valuation of the user base () always induces the firm to reduce both the subscription fee and the length of the advertising clip. Intuitively, when is large, the marginal value of retaining additional users through network effects outweighs the marginal revenue from charging higher fees or imposing longer ads. As a result, the platform optimally sacrifices immediate revenue extraction in order to preserve a broader consumer base, which in turn amplifies future value.

The comparative statics further reveal a nuanced interaction between and the advertising market. For subscription fees, the freemium design attenuates the sensitivity to relative to the pure subscription model (). This arises because, under freemium, higher fees do not drive marginal consumers entirely out of the market: ad-tolerant users can still join via the advertising channel. This cushions participation losses and reduces the extent to which forces downward adjustment of . By contrast, in the subscription-only regime, fee reductions are the sole lever for expanding the user base, making more strongly decreasing in .

For advertising length, the relative responsiveness hinges on the advertising price A. When A is modest (), the freemium platform reduces ad length more aggressively than the ad-only benchmark. In this range, attracting additional users through shorter clips is particularly valuable, and subscription revenue provides a substitute source of income that allows sharper ad cuts. Conversely, when , the ranking reverses: the freemium platform sustains longer ads than the ad-only regime. Here, ad-averse consumers can exit the ad channel by paying the subscription fee, which permits the platform to intensify advertising on tolerant users without jeopardizing overall participation. The threshold thus captures the point where the relative buffering roles of fee and advertising instruments switch.

Taken together, these results underscore how not only lowers the absolute levels of and but also reshapes their comparative sensitivities across regimes. A higher user-base valuation magnifies the complementarity of the freemium design: the subscription channel mitigates the participation cost of longer ads, while the advertising channel cushions the participation cost of higher fees. This dual buffering effect explains why, even as both instruments decline with , the freemium regime maintains strictly greater intensity than either pure strategy in their respective domains (consistent with Proposition 2).

4.4. Effect of Consumer Heterogeneity

We next examine how the profitability of the freemium design depends on the degree of consumer heterogeneity. The logic of segmentation hinges on the gap between ad-averse and ad-tolerant users: when heterogeneity is sufficiently large, the firm can profitably separate the two groups and extract revenue from both; when heterogeneity is small, the screening mechanism weakens and the advantage of freemium diminishes. The following proposition formalizes this intuition.

Proposition 4.

Role of consumer heterogeneity

The profitability of the freemium strategy requires sufficient heterogeneity in consumers’ disutility from advertising. In particular, as the ratio decreases, the incremental revenue advantage of the freemium regime over the pure strategies converges to zero.

Proposition 4 highlights that the freemium model is not universally superior but instead critically depends on dispersion in ad tolerance. When is large, the platform benefits from offering a differentiated menu: high-disutility consumers () contribute through subscription fees, while low-disutility consumers () generate advertising income. The interior condition ensures that both segments are simultaneously served, thereby expanding the revenue frontier beyond what either pure strategy could achieve.

By contrast, as approaches one, consumers become increasingly homogeneous and the screening mechanism breaks down. In this case, the firm cannot meaningfully distinguish between subscription and advertising users, and the freemium strategy collapses toward the payoff of the superior pure regime. This result underscores that the profitability of freemium arises not merely from combining fee and advertising instruments, but from leveraging heterogeneity in consumer ad tolerance to segment the market effectively.

5. Discussion

This paper develops a unified framework to analyze a platform’s monetization choice between three canonical strategies: subscription-only, advertising-only, and freemium. By explicitly modeling consumer heterogeneity in ad disutility and incorporating the platform’s valuation of user-base size, we derive closed-form solutions for optimal pricing and advertising decisions under each regime and identify the conditions under which each strategy dominates. Our analysis yields several insights that contribute to both theory and practice.

First, we show that the firm’s optimal strategy is governed by two threshold values of the advertising price, and . When the ad price is low (), the advertising market is too weak to sustain participation, and subscription-only emerges as optimal. When the ad price is high (), advertising-only becomes dominant, as the subscription channel no longer contributes incremental revenue. Between these two cutoffs (), the platform strictly prefers the freemium model, which combines subscription and advertising. In this intermediate region, the firm leverages heterogeneity in ad tolerance to segment consumers: ad-averse users purchase the service while ad-tolerant users provide advertising income. This threshold-based characterization (Proposition 1) offers clear operational guidance by mapping observed advertising market conditions to strategic choices.

Second, our results clarify how the freemium model modifies the intensity of instruments. Proposition 2 demonstrates that both the subscription fee and advertising length under freemium are at least as high as those in the corresponding pure regimes. This finding underscores the strategic complementarity of combining two monetization channels: the subscription fee can be raised without fully losing users, as marginal consumers may migrate to the ad-supported option, while advertising can be lengthened because ad-averse users can bypass it by paying. The revenue dominance of freemium in its admissible region stems precisely from this ability to extract surplus from both consumer types.

Third, we establish how the platform’s valuation of its user base, captured by , shapes optimal instrument levels (Proposition 3). Across all regimes, both subscription fee and ad length decline in , as the platform seeks to expand participation when the marginal value of users is high. Importantly, the sensitivity of ad length to differs between freemium and ad-only. When the ad price is moderate, the reduction in ad length is steeper under freemium, reflecting the fact that only ad-tolerant consumers watch ads, and the firm faces weaker opportunity costs from shortening the clip. By contrast, when the ad price is high, the ad-only model exhibits greater responsiveness, since both consumer types are exposed to advertising. These results highlight that network effects not only alter the absolute level of instruments but also reconfigure their relative trade-offs across strategies.

Finally, we demonstrate that the profitability of the freemium strategy hinges on consumer heterogeneity in ad tolerance (Proposition 4). When the ratio is large, the platform gains substantially by offering a differentiated menu: ad-averse consumers contribute fee revenue, while ad-tolerant consumers provide advertising revenue. As heterogeneity shrinks and , the screening mechanism breaks down, and the incremental advantage of freemium vanishes. In the limit, the firm simply reverts to whichever pure strategy yields higher revenue. This underscores that freemium’s profitability arises not merely from combining instruments, but from exploiting heterogeneity to segment the market effectively.

Taken together, our findings contribute to the growing literature on platform monetization by providing a tractable, fully comparative framework that nests and contrasts the three leading strategies. Beyond theoretical characterization, the results offer practical implications for digital platforms, media providers, and subscription-based services. Managers should recognize that the attractiveness of freemium depends critically on both external ad-market conditions (A) and internal assessments of user-base value (). In weak ad markets, subscription remains essential; in strong ad markets, advertising-only is sufficient; and in intermediate markets with heterogeneous users, freemium strictly dominates.

While the framework provides clear analytical insights, several limitations suggest important directions for future research. First, the model is static and does not account for dynamic evolution in consumer ad tolerance, advertiser willingness to pay, or user-base growth. Incorporating such dynamics may alter the threshold structure and yield sharper predictions about how platforms transition between monetization regimes over time. Second, the analysis focuses on the three canonical strategies—subscription-only, advertising-only, and freemium—and intentionally abstracts from intermediate or hybrid menu designs such as downgraded free tiers, limited-functionality versions, or mixed low-fee-with-ads plans. Incorporating menu variations or explicitly modeling transitional dynamics would offer a more complete account of platform monetization. Third, consumer heterogeneity is represented through a two-type structure for tractability. Allowing for continuous or behaviorally grounded preference distributions could reveal additional segmentation mechanisms that shape the profitability of freemium strategies. Finally, the analysis assumes a monopolistic platform. Extending the framework to competitive environments—where platforms interact strategically in pricing, ad loads, and user acquisition—together with empirical validation using platform-level data, would strengthen external validity and broaden the applicability of the model’s implications.

In summary, this paper shows that freemium is neither universally optimal nor merely a hybrid compromise: its success arises from carefully balancing subscription and advertising instruments, calibrated to market conditions, network effects, and consumer heterogeneity. This nuanced view advances both theory and practice by clarifying when and why freemium emerges as the platform’s revenue-maximizing choice

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and H.S.; methodology, Y.S.P.; formal analysis, H.S. and Y.S.P.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.S.P.; writing—review and editing, J.L. and H.S.; project administration, H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

Jinhwan Lee is employed by RIDI Corporation. The authors declare that this employment does not involve any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Proof of Results

Proof of Lemma 1.

- (a)

- For the subscription-only strategy, the profit is . Differentiating and setting the F.O.C. to zero gives , which is feasible when . For , the derivative is non-positive, so the corner solution applies. Substitution yields .

- (b)

- For the advertising-only strategy, with . The F.O.C. gives , valid when both types participate, in which case . If instead only low-disutility consumers remain, the relevant objective is . Optimizing yields and .

□

Proof of Proposition 1.

We compare profits under the three candidate strategies.

- (i)

- If the subscription fee is set below , no consumers choose advertising, so the outcome coincides with the subscription-only model. Lemma 1(a) then applies, yielding . Comparing with the freemium payoff at shows that dominates whenever , which defines threshold .

- (ii)

- If instead , all consumers watch advertising and no one subscribes. This reduces to the advertising-only model, with optimal revenue from Lemma 1(b). By direct comparison with the freemium payoff, one can verify that advertising dominates once A exceeds threshold .

- (iii)

- The remaining region is when , so both mechanisms coexist. In this case the objective iswhich is strictly concave in p. Solving the F.O.C. yields a feasible interior solution whenever , giving the freemium expressions reported in Table 1.

Thus the optimal strategy is subscription-only when , freemium when , and advertising-only when . □

Proof of Proposition 2.

We compare the optimal instruments under the freemium regime with those under the pure strategies.

- (i)

- Subscription fee. Under the subscription-only strategy, Lemma 1 givesIn the freemium regime, Proposition 1 yieldsSubtracting the two expressions givessince and the denominator in the second term is positive for all feasible . Hence .

- (ii)

- Advertising length. The optimal advertising length in the ad-only regime iswhile in the freemium regime it isA direct comparison showswhere is a quadratic form in A that remains strictly positive whenever both and are feasible (i.e., and ). Consequently, .

Combining (i) and (ii), we conclude that both instruments are weakly stronger under the freemium strategy than in their respective pure strategies. □

Proof of Proposition 3.

We show (i) both instruments decrease in , and (ii) the stated cross–regime ordering of sensitivities.

- (i)

- Signs. From Lemma 1 and Proposition 1,where . Differentiating holding fixed,so all four derivatives are negative whenever the corresponding optima are feasible (i.e., for and for ).

- (ii)

- Relative magnitudes. For fees, a direct comparison yieldswhere the positivity follows from (ensuring ) and feasibility of , which jointly imply the numerator is positive. Hence

For advertising length, consider the difference

At the lower boundary one obtains

while at the upper boundary (where F and meet) one finds

Since is continuous in A on , by the intermediate value theorem there exists a threshold such that , with for and for . Equivalently,

This establishes the claim. □

Proof of Proposition 4.

Recall that the strategy thresholds are given by and , with . Note that is invariant to the ratio , whereas is strictly decreasing in this ratio. As , we obtain and thus

In this limit, the freemium region collapses to a singleton, and the incremental profit of the freemium regime over the pure strategies vanishes. Hence, sufficient dispersion in disutility from advertising is necessary for the freemium design to yield a strict profitability advantage. □

References

- Mai, Y.; Hu, B. From Growth to Monetization: Managing Freemium Services. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäntymäki, M.; Islam, A.N.; Benbasat, I. What drives subscribing to premium in freemium services? A consumer value-based view of differences between upgrading to and staying with premium. Inf. Syst. J. 2020, 30, 295–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, C.W.J.; Maleki Vishkaei, B.; De Giovanni, P. Subscription-based business models in the context of tech firms: Theory and applications. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Oper. Manag. 2024, 6, 256–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.W.; Lin, T.X.; Farn, C.K. The Free-of-Charge Phenomena in the Network Economy—A Multi-Party Value Exchange Model. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 16, 2981–3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.P.; Coate, S. Market provision of broadcasting: A welfare analysis. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2005, 72, 947–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M. Competition in two-sided markets. RAND J. Econ. 2006, 37, 668–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, A.; Misra, K. Fee or free: When should firms charge for online content? Manag. Sci. 2017, 63, 1150–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichihashi, S.; Kim, B.C. Addictive platforms. Manag. Sci. 2023, 69, 1127–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, P.; Zhou, B. Sponsored content advertising in a two-sided market. Manag. Sci. 2021, 67, 7560–7574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Shi, Q.; Banerjee, S. Monetizing platforms: An empirical analysis of supply and demand responses to entry costs in two-sided markets. Manag. Sci. 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Niculescu, M.F.; Wu, D.J. Economics of free under perpetual licensing: Implications for the software industry. Inf. Syst. Res. 2014, 25, 173–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Zhang, K.; Srinivasan, K. Freemium as an optimal strategy for market dominant firms. Mark. Sci. 2019, 38, 150–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Kannan, P.; Ma, L. Selling the premium in freemium. J. Mark. 2018, 82, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, O.F.; Benlian, A. The effect of free sampling strategies on freemium conversion rates. Electron. Mark. 2017, 27, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jain, S.; Kannan, P. Optimal design of free samples for digital products and services. J. Mark. Res. 2019, 56, 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubé, J.P.; Misra, S. Personalized pricing and consumer welfare. J. Political Econ. 2023, 131, 131–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.V.; Musalem, A. When consumers learn, money burns: Signaling quality via advertising with observational learning and word of mouth. Mark. Sci. 2021, 40, 168–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S. Freemium as optimal menu pricing. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2019, 63, 480–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, A.; Tucker, C. Online display advertising: Targeting and obtrusiveness. Mark. Sci. 2011, 30, 389–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.P. Targeted advertising and advertising avoidance. RAND J. Econ. 2013, 44, 128–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).