Abstract

Although the use of mobile payments has become increasingly prevalent, understanding the factors that persuade users to continue to rely on the transaction method remains limited. This study applied the Uses and Gratifications Theory and a contingency perspective to examine the relationship between personalized artificial intelligence and users’ intention to continue using mobile payments. Drawing on the contingency perspective, we also assessed four moderating factors: age, educational level, social network, and technological diversity. Using survey data collected from 515 Chinese users and applying hierarchical regression analysis, our results reveal that personalized artificial intelligence significantly enhances users’ intention to continue using mobile payments. Educational level, social network, and technological diversity also have a positive influence but age has a deterring effect. Our empirical findings constitute an academic contribution to a deeper understanding of the dynamics that persuade mobile payment users not to change their routine.

1. Introduction

Within a relatively brief span, mobile payment has become a ubiquitous way to perform day-to-day transactions. The shift from cash and credit cards was driven by the rapid development of financial technology and e-commerce, as well as the widespread popularity of smartphones and social networks [1]. With the swift changes in payment methods, a growing body of academic research has focused on identifying the factors that influence the adoption of mobile payments. Early studies mostly employed the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) model. They emphasized ease of use and perceived usefulness to explain mobile payment adoption [2,3]. With the usage of mobile payments soaring to the point that cash payments are increasingly rare, the earlier approach is no longer providing an insightful understanding [4]. The focus of research should now shift toward understanding what factors encourage users to continue using mobile payment systems, rather than merely adopting them.

The advent of the Fourth Industrial Revolution has transformed many industries. One of the notable drivers of change has been the convergence of different technologies. This is seen in the financial industry, where new technology has spawned mobile payment systems [5]. These systems are increasingly being paired with artificial intelligence (AI) to enable personalized services. The AI systems generate personalized recommendations for mobile payment users based on users’ preferences, behaviors, past actions, and interests [6,7]. The aim is to enhance user experience enough to motivate further willingness to use mobile payment services [8]. In this context, various factors may influence the relationship. However, despite its relevance, this area of user behavior has received relatively little academic attention to date.

We have identified several research gaps in the existing literature. First, there has been limited research on the factors influencing individuals to continue using mobile payment services. As previously mentioned, most studies on mobile payment have primarily focused on initial adoption, often drawing on theories such as TAM and UTAUT [2,3]. These studies largely examine factors like perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, risk, and trust [4]. As a result, they fall short of providing a broader understanding of what influences behavior after mobile payment systems are adopted.

Second, previous studies suggest little insight into how the integration of technologies such as AI influences the continued use of mobile payment services. Most existing studies focus on how AI systems in mobile payment are used for risk analysis [9] or consist of review articles on the application of AI in digital finance [10]. Consequently, there is a noticeable lack of empirical research examining how the integration of AI into mobile payment systems influences actual user behavior—particularly in terms of user retention.

Third, there is a significant lack of research on the factors that moderate the relationship between AI integration and intention to continue using mobile payment services [5,11]. While previous studies have identified various factors that influence users’ willingness to use such services—including personal characteristics such as age and gender, as well as external factors like institutional frameworks and regulations—most of this research has focused on initial adoption. Little attention has been paid to the factors that affect continued use, particularly in the context of how AI influences this behavior [3,12]. As a result, our understanding of possible determinants in the relationship between AI and users’ continued utilization of mobile payment services remains very limited.

Based on these research gaps, this study aims to address the following three research questions: (1) How does the integration of AI technology with mobile payment systems influence mobile payment adoption? (2) Specifically, does personalized AI affect mobile payment users’ intention to continue using the service? (3) What factors may moderate this relationship? To explore these questions, we conducted a survey with 560 mobile payment users in China. China, a frontrunner in financial technology [13], is a prime example of where the leap from cash directly to electronic payments via mobile payment systems has been achieved successfully. Mobile payments are now ubiquitous across the country, with a penetration rate exceeding 85% [14]. In this regard, China is one of the most successful countries in transitioning from cash to digital payment, with 85% of its population using mobile payment services as of 2025. Given the widespread prevalence of mobile payment in China, it offers an ideal setting to explain why users retain their mobile payment systems.

This study makes several academic contributions. First, it addresses key research gaps by presenting empirical findings on the factors that influence users’ continuation of using mobile payment systems. Previous studies mostly focused on the initial adoption of mobile payment. Our research integrates the Uses and Gratifications Theory (UGT) and a contingency perspective to explore the drivers behind the intention to continue using mobile payments. In doing so, we contribute to a deeper understanding of what keeps users engaged with mobile payment services over time. Second, this study provides empirical evidence on how personalized AI, grounded in UGT, influences the continuing use of mobile payments. To date, related studies have either lacked a strong theoretical foundation or offered little empirical investigation. Our research fills this void by offering a theoretically informed and empirically supported analysis.

Finally, and most importantly, this study makes a significant academic contribution by identifying four key variables that influence the relationship between personalized AI and the continued use of mobile payments, based on a contingency perspective. Specifically, we examine how individual characteristics (education level and age) and external factors (social network and technological diversity) moderate this relationship. To our knowledge, no prior studies have explored these moderating effects within this context. By doing so, this research not only deepens our understanding of the dynamics between AI personalization and retention of mobile payment usage but also broadens the theoretical and empirical scope of related studies.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Personalized AI and the Continued Use of Mobile Payments

Drawing on the UGT, users are viewed as active agents if they choose technologies based on their individual needs, which are shaped by both personal and environmental factors [15]. UGT explains why and how individuals actively seek out specific media or technologies to satisfy desires or goals. Rather than being passive recipients, users make conscious decisions to engage with technologies that fulfill their gratification needs [16]. In this context, users’ motivations to use mobile payment services and other technologies play a critical role in shaping their willingness to continue using them. UGT has been widely applied to explain continued usage behaviors in various fields such as the Internet [17], artificial intelligence [18], and gaming [19]. Although relatively limited, studies have also applied UGT to explore mobile payment adoption [20]. UGT thus offers a useful framework for understanding why users continue using mobile payment services. When these services effectively satisfy user needs—referred to as gratifications—users are more likely to persist in their usage and adopt new features. Common gratification factors in mobile payments include convenience [21], personalization [22,23], trust [24,25], and the social network, all of which may significantly influence a user’s intention to continue using such services.

Based on the UGT, we argue that personalized AI positively influences users’ intention to continue using mobile payment services. Personalized AI refers to the use of AI-driven algorithms to deliver tailored content, services, or interactions based on individual user preferences, behaviors, and contextual data [26]. Recent studies in the field of IS have increasingly recognized personalized AI as a key factor influencing users’ willingness to adopt and continue using new technologies. By providing customized services and personalized interactions, firms can enhance customer trust, commitment, and satisfaction, thereby fostering long-term customer relationships [6,27]. With the advancement of data-driven technologies in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, personalized technologies are increasingly leveraged to understand customer needs better and deliver more relevant and differentiated experiences. Through the utilization of big-data analytics and machine learning, personalized AI can significantly optimize service delivery by offering more agile, accurate, and context-aware suggestions [28]. This enhancement in service sophistication and relevance, in turn, has a positive impact on users’ willingness to continue using mobile payment services [29].

For instance, personalized AI can provide intelligent suggestions and real-time financial management by analyzing users’ historical transaction records, payment preferences, and consumption habits. This makes the payment process more intelligent and efficient, satisfying users’ informational needs [30]. These services rely on emerging technologies to analyze user behavior patterns through AI algorithms based on the data profile of a user. They dynamically adjust service content, features, and interaction methods to meet users’ unique needs, delivering highly tailored services in the right context and at the right time [26]. This enables the realization of an intelligent experience often described as “a thousand users, a thousand faces” [31]. Therefore, such personalized recommendation services can be a key factor in encouraging users to continue using mobile payment services.

Specifically, personalized AI can analyze users’ historical behavior, preferences, and location data to push products and services that better meet their needs. Users can experience the value of convenience and efficiency [32,33]. Personalized information can enhance users’ cognitive value, which is also a key psychological mechanism driving the continued use of technology [34]. In other words, personalized technology meets users’ expectations for long-term use by providing dynamic updates, instant feedback, and continuously optimized service processes, thereby extending their usage cycle [35]. Those are key factors in promoting their continued use of mobile payments [36,37].

Personalized AI services not only enhance the value-in-use by delivering instant satisfaction through advanced technologies, but also strengthen emotional connection, trust, and social interaction [21]. Furthermore, this trust is not merely a byproduct but a fundamental pillar for sustainable adoption. When users perceive AI systems as both useful and reliable in handling their data, their trust deepens, reinforcing long-term engagement and encouraging reliance on mobile payments for daily transactions [25,38].

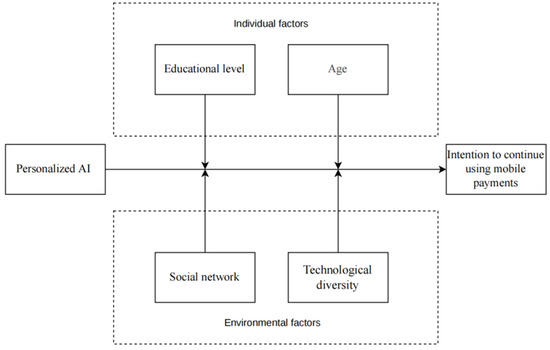

Based on UGT, by leveraging personalized AI, firms can predict user behavior through big data analysis and make adaptive adjustments based on individual needs and preferences. This process enhances user satisfaction and experience, ultimately increasing user retention within mobile payment systems [39]. Several studies show that a higher level of personalized AI services leads to greater user retention and continued usage of the service [22]. This is because personalized AI—enabled by data analytics and machine learning—can offer accurate suggestions, intelligent customer service, and customized payment solutions, all of which contribute to an improved overall user experience. When users recognize the convenience and decision-making support provided by these personalized services, particularly in relation to their individual needs and environmental context, they are more inclined to continue using the mobile payment service. Based on this, we propose the following hypothesis, with our research model shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research Model.

H1.

Personalized AI is positively associated with consumers’ intention to continue using mobile payments.

2.2. Mobile Payment Continuance: A Contingency Perspective

The contingency theory argues that the behavioral decisions of organizations and individuals must be dynamically adjusted based on variables such as the external environment, organizational structure, technology, and individual characteristics [40]. From a contingency perspective, individual decision-making is not determined by a single factor, but rather influenced by a combination of personal traits and external conditions. These contingent factors include not only formal institutions such as national rules and laws, but also personal variables such as age, gender, and educational level [41]. From this perspective, the contingency framework offers important theoretical value in analyzing the complex behavioral mechanisms underlying mobile payment adoption. This is because the willingness to continue using personalized AI—not just initial adoption—is shaped by the synergistic interaction between individual traits and the technological environment [5,10].

By drawing on the contingency perspective, we argue that contextual factors surrounding users may influence their intention to continue using mobile payment services. Recent studies have also confirmed that diverse contingent factors influence the complex relationship between personalization and mobile payment continuance [41]. For instance, when individual characteristics (such as education level) and external environment (such as technological diversity) jointly affect users’ experience and have a positive impact, users will feel a higher fit and enhance the sustainability of their use [42]. Similarly, the adaptability between the technological environment and user characteristics is a key contingency factor affecting sustained usage behavior [43]. This perspective also extends Bhattacherjee’s (2001) [12] view on sustained use drive, emphasizing that personalized user service experience is formed through the interaction of multiple contingency factors, motivating users to persist in using new technological systems. This matching based on specific situations is the core of contingency theory.

2.2.1. The Moderating Effect of Age

From the perspective of contingency theory, we argue that age moderates the relationship between personalized AI and users’ intention to continue using mobile payments. Age has been identified as a significant factor influencing technology acceptance in IS studies [41]. On the one hand, young users usually have high digital literacy and proficiency in using new technologies, and can quickly understand and use the value brought by personalized AI. They tend to quickly adapt to emerging personalized technology services, such as personalized AI services launched based on customer needs [44,45]. They have a stronger perception of the convenience, intelligence, and personalized features provided by new technologies, and this positive user experience can effectively enhance their satisfaction and willingness to continue using mobile payment services [2,46]. In addition, Lee and Li (2024) [41] proposed that compared to elderly users, young users face fewer barriers in perceiving and using mobile payments, which further strengthens their continued use of such services.

On the other hand, as individuals age, their information processing and perceptual abilities may decline, affecting their ability to learn and adapt to new technologies [36,47]. Specifically, older users may face more cognitive and psychological barriers during the use of new technologies, such as concerns about privacy and security, as well as resistance to technological complexity [48]. Therefore, even if mobile payment platforms provide highly personalized AI services, older users may still not fully perceive their value and may even develop resistance due to cognitive load, thereby weakening the positive impact of personalized AI on their willingness to continue using them [49].

Therefore, age plays a key moderating role in shaping the impact of personalized AI on continued mobile payment use, with younger users responding more positively than older users [2]. In this regard, we argue that younger users strengthen the relationship between personalized AI and the intention to continue using mobile payments. Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H2.

Age negatively moderates the relationship between Personalized AI and consumers’ intention to continue using mobile payments.

2.2.2. The Moderating Effect of Educational Level

By drawing on the contingency perspective, we argue that educational level positively moderates the relationship between personalized AI and users’ intention to continue using mobile payments. Contingency theory emphasizes that individual characteristics—such as knowledge, experience, and cognitive abilities—can significantly influence the adoption and continued use of mobile payment technologies [5]. Among these, educational level is a particularly salient factor [50]. Prior IS studies suggest that individuals with higher levels of education are often early adopters of new technologies and are more likely to sustain their usage over time [51]. Conversely, individuals with lower educational attainment may have limited information processing capacity, which can hinder their ability to understand, trust, and adapt to advanced technologies—negatively influencing their post-adoption behaviors.

From this perspective, users with higher educational levels tend to possess stronger cognitive skills and enhanced information processing capabilities. These individuals are better equipped to understand the complexity and benefits of personalized AI recommendation systems and are more likely to perceive their value in mobile payment contexts [52]. Moreover, highly educated users are generally more aware of the security, efficiency, and personalization features embedded in AI-based mobile payment services. As such, they are better able to align these technological benefits with their personal needs, increasing their likelihood of continued usage [53]. In addition, their higher learning capacity and openness to innovation allow them to establish greater trust in technology and better navigate the AI-enabled service environment. This also implies that compared to less educated users, those with higher educational attainment are more likely to appreciate the long-term value of personalized AI services and integrate them more deeply into their digital payment behavior [11]. Hence, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H3.

The educational level positively moderates the relationship between Personalized AI and consumers’ intention to continue using mobile payments.

2.2.3. The Moderating Role of Technological Diversity

Technological diversity refers to the breadth and depth of different technological functions and applications provided by a system or platform, which determines the diversity of technological solutions that users can choose during the usage process [54]. The principle of situational adaptation based on contingency theory states that the realization of technological efficiency is essentially the result of dynamic matching between technology supply and user demand [40]. The effectiveness of personalized AI technology relies on the dynamic matching between user needs and new technologies. Therefore, in the context of mobile payments, technological diversity is a key contextual variable that provides a supportive environment for the continued use of mobile payments by enhancing the system’s adaptability [5].

Firstly, new technologies provide multiple payment methods (such as QR code payment, NFC payment, biometric recognition, etc.) and cross-platform adaptation capabilities (such as mobile phones, watches, POS terminals, etc.) to help users flexibly choose the most suitable service plan according to different scenarios, thereby improving the satisfaction of personalized services [55]. Lee and Li (2024) [41] proposed that exposure to diverse technological environments can influence users’ cognition and attitudes toward usage. Therefore, when personalized AI services are combined with diverse technological environments, users are more likely to experience the convenience and fit of the service, and this positive experience is crucial for forming a willingness to continue using.

In addition, technological diversity not only underpins personalized AI services but also reduces implementation costs and enhances user retention by enabling more appealing service offerings [56]. Technology-enabled personalized AI can reduce users’ decision-making costs, making it easier for users to find service paths that highly match their needs among diverse choices, amplifying positive experiences during use, and ultimately promoting their willingness to continue using [7]. Technological diversity not only affects users’ initial adoption but also shapes long-term usage behavior. However, existing research is mostly limited to studying the acceptance of new technologies, ignoring whether users are willing to continue using them in the future. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H4.

Technological diversity positively moderates the relationship between Personalized AI and consumers’ intention to continue using mobile payments.

2.2.4. The Moderating Role of Social Network

From a social network perspective, we argue that Social Network positively moderates the relationship between Personalized AI and users’ intention to continue using mobile payments [57]. When users are embedded in strong social networks, they are more likely to be influenced by the opinions, behaviors, and experiences of others within their network [58]. In such environments, personalized AI gains greater credibility and perceived value, as they are often validated or echoed by trusted peers [59]. As Wellman (2002) [60] pointed out, in the online society, information systems are embedded in society, and users not only rely on recommendations generated by AI systems but also on interactions with other users to make decisions and achieve sustained user engagement.

For instance, if AI-driven recommendations are aligned with the preferences or experiences of users’ close social contacts, users are more likely to view them as reliable and relevant [61]. This social validation effect enhances users’ trust in the AI system and reduces uncertainty or skepticism toward the technology [62,63]. Moreover, individuals in strong social networks often share information about convenience, promotions, or security features of mobile payment systems, which can reinforce the usefulness of personalized services and foster habitual use [64]. Therefore, in contexts where users are part of active and trusted social communities, the impact of personalized AI on continued use is likely to be stronger [65]. These users are not only more exposed to shared positive feedback but also tend to conform to social norms, leading to a higher likelihood of sustained mobile payment behavior [66]. That is, when personalized AI is supported by other users’ experience and network credibility, users are more likely to act repeatedly and strengthen their willingness to continue using it [67]. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H5.

Social network positively moderates the relationship between Personalized AI and consumers’ intention to continue using mobile payments.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

The survey was conducted among users who use mobile payments in China. We targeted individuals who have previously used mobile payments. We collected data through a questionnaire platform in China, and the data collection method was online surveys, which can better expand the scope of data collection. The data collection adopts quantitative research methods and conducts questionnaire surveys through online questionnaire platforms. During the questionnaire design process, in order to avoid common method bias, anonymous filling and random ordering of questions were adopted.

All responses from the respondents in this survey have been anonymized. Data collection was conducted twice, 2 January–10 February 2025, and 20 February–31 March 2025, to mitigate common method bias. This multi-wave design, involving data collection at different time points, reduced single-source bias through temporal separation [41]. During this period, 560 questionnaires were distributed, and a total of 515 valid questionnaires were collected, with the response rate of about 92%. The survey subjects come from different age groups, regions, and income groups, covering a wide range of consumer groups. In order to improve the effective response rate of questionnaire collection and avoid the annoyance of survey respondents, we have set up several simple personal information-related questions and related scale questionnaire questions.

3.2. Sample Characteristics

The sample (N = 515) exhibited diverse demographic characteristics, including a gender distribution (49.7% male, 50.3% female). The largest age group was 26–35 years old (23.3%), followed by 19–25 (21.7%). In terms of education, 25.4% held a bachelor’s degree. The majority were full-time employees (42.5%), followed by individual business owners (28.2%).

3.3. Estimation Methodology

Multiple regression is common in testing hypotheses, which can usually provide a satisfactory approximation of the regression function, and it is more suitable for dealing with the interaction effect test of moderating variables in this study (Su et al., 2012) [68]. At the same time, multiple regression shows multiple interaction terms more flexibly and visually presents the direction and strength of moderating effects, providing a more intuitive and concise explanation when the relationships between variables are clear. Therefore, we chose to use SPSS 26.0 for multi-step hierarchical regression analysis to test our hypotheses [69].

3.4. Measurements

We evaluated each variable based on a five-point Likert scale, with options ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). To clarify the assumptions for respondents, we provided additional instructions: for AI, respondents were asked to assume a “personalized AI-based pricing recommendation system” with general functions such as store recommendations, price comparisons, and personalized promotions; for mobile payment, respondents were asked to assume a commonly used mobile payment service similar to WeChat Pay or Alipay, which are widely used in China.

Specifically, we evaluated the independent variable Personalized AI using four items [6,70]. For the dependent variable ‘continued use intention of mobile payments’, we used four items to measure it [71,72]. For moderating variables, we use four items including different devices, platforms, operating systems, and payment functions to measure Technological diversity [41]. We also used four items to measure Social network [57,73]. The full questionnaire is provided in Appendix A.

For demographic analysis, we used age, education level, gender, income, and occupation. For example, age range: 1 = 18 years old and below, 2 = 19–25 years old, 3 = 26–35 years old, 4 = 36–45 years old, 5 = 46 years old and above. Gender: 0 = male, 1 = female.

4. Results

4.1. Model Testing

We used SPSS 26.0 for data analysis and employed hierarchical regression to test the hypotheses proposed in our paper. In this study, we used Harman’s single-factor test (HSFT) to examine common method biases. The results of the HSFT indicated that the total variance explained by the single extracted factor was about 35%. Therefore, our data do not have significant common method bias issues. To evaluate the reliability and validity of the measurement model, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on the scale. The standardized factor loadings for each question are all greater than 0.5, and the residuals are positive and significant, indicating no violation of estimation.

Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) are both above the cutoff criteria of 0.7 (e.g., minimum alpha of 0.862) [74], and the average extracted variance (AVE) is greater than 0.5 (e.g., minimum AVE value of 0.615), meeting the criteria for convergent validity. The fit is also within an acceptable range. When using confirmatory factor analysis for validity testing, it is necessary to evaluate the fit of the model and modify the measurement model to improve its fit. According to Hu and Bentler’s (1999) [75] suggestion, the main indicators of the model fitting parameters are: X2 = 258.386, X2/df = 2.637 < 3; CFI = 0.966 > 0.95; TLI = 0.958 > 0.95; IFI = 0.966 > 0.95; RMSEA = 0.056 < 0.1 meets the standard. Table 1 reports the reliability and validity of the measurements.

Table 1.

List of items and validity.

4.2. Correlations and Descriptive Analysis

From the results in Table 2, personalized AI (r = 0.472, p < 0.01), social network (r = 0.345, p < 0.01), and technological diversity (r = 0.250, p < 0.01) are all significantly positively correlated with continued use, indicating that these three variables help to enhance users’ willingness to continue using.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlations.

In the control variables, age is negatively correlated with continued use (r = −0.201, p < 0.01), and education level is positively correlated with continued use (r = 0.304, p < 0.01). Additionally, a significant but weak positive correlation exists between gender and continued use (r = 0.107, p < 0.05).

4.3. Hypotheses Testing Results

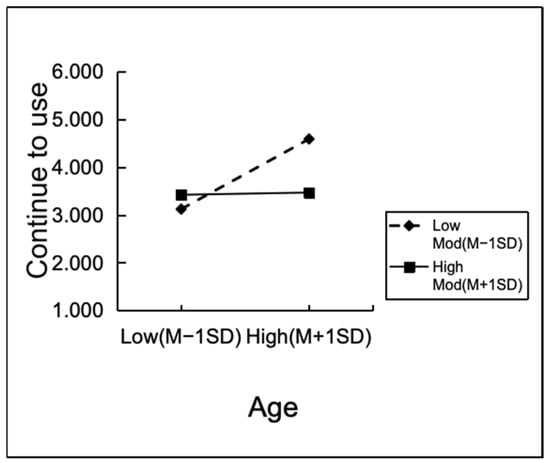

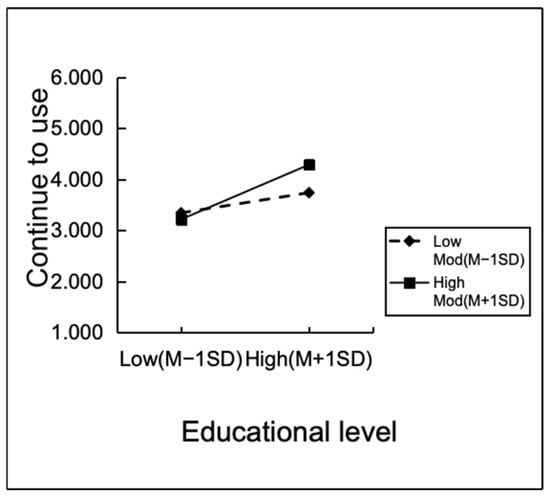

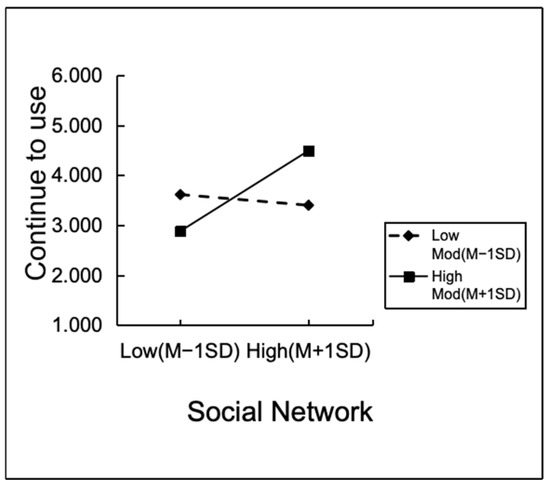

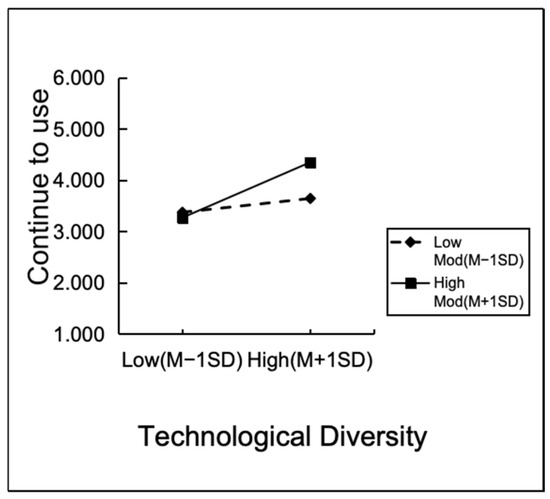

To test the research hypothesis, this study used multiple regression analysis to examine the data, and the results are shown in Table 3 and Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5. Model 1 includes only control variables. Model 2 examines the main effect of personalized AI on continued mobile payment use. Models 3 and 4 test the moderating effects of age and educational level, respectively. Model 5 assesses the moderating effect of social network, while Model 6 examines the effect of technological diversity.

Table 3.

Hypotheses Testing Results.

Figure 2.

Moderating Effect of Age.

Figure 3.

Moderating Effect of Educational Level.

Figure 4.

Moderating Effect of Social Network.

Figure 5.

Moderating Effect of Technological Diversity.

Firstly, regarding the H1 hypothesis, Model 2 revealed that personalized AI has a significant positive impact on the continued use intention of mobile payments (β = 0.289, p < 0.001), supporting the H1 hypothesis which is the main hypothesis. This indicates that as personalized AI increases, consumers’ intention to continue using mobile payments will also significantly increase.

Secondly, H2 and H3 propose that individual demographics moderate the relationship between personalized AI and the intention to continue using mobile payments. Model 3 shows age has a significant negative moderating effect (β = −0.142, p < 0.001), supporting H2. Model 4 shows education positively moderates this relationship (β = 0.135, p < 0.001), with stronger effects among highly educated users, supporting H3.

Furthermore, H4 and H5 propose that the environment moderates the effect of personalized AI on mobile payment post-adoption. Model 5 incorporates the social network and its interaction with personalized AI. The interaction term is significant and positive (β = 0.365, p < 0.001). This result confirms hypothesis 4. Model 6 tests the moderating role of technological diversity. The interaction between personalized AI and technological diversity is significantly positive (β = 0.144, p < 0.001), supporting hypothesis 5. Figure 4 and Figure 5 illustrate this moderation effect.

Finally, to elucidate the nature of the significant interaction effects, simple slope analyses were conducted. The results, summarized in Table 4, reveal the distinct moderating patterns of the four moderators. The moderation results show clear group differences in how Personalization AI influences behavioral intention. For Age, the effect is strong at the low level (β = 0.587, p < 0.001) and moderate at the mean (β = 0.302, p < 0.001), but disappears at the high level (β = 0.019, p = 0.716), indicating reduced responsiveness among older users. Educational level shows the opposite pattern, with effects increasing from low (β = 0.158, p < 0.001) to medium (β = 0.293, p < 0.001) and high (β = 0.428, p < 0.001). Social network intensity also strengthens the effect, shifting from nonsignificant at the low level (β = –0.086, p = 0.346) to significant at medium and high levels (β = 0.279 and 0.564, both p < 0.001). Technological diversity shows a consistent amplification from low (β = 0.108, p = 0.015) to medium (β = 0.289, p < 0.001) and high (β = 0.433, p < 0.001). Overall, personalization AI is more effective among younger, more educated, more socially connected, and more technologically diverse users.

Table 4.

Moderation Analysis.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

The question of whether personalized AI can enhance consumers’ intention to continue using them has garnered attention but remains insufficiently explored in existing research. By surveying 515 Chinese users, this study found that personalized AI has a positive impact on consumers’ willingness to continue using mobile payment platforms. Drawing on the contingency perspective, we further examined the moderating effects of individual and external factors. Specifically, age negatively moderates the relationship, while educational level positively moderates it. In addition, external factors, including social networks and technological diversity, positively moderate the relationship. Based on these findings, we propose several theoretical implications.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This study makes several academic contributions. First, based on the UGT, it extends the extant research on mobile payments by exploring how the integration of AI can enhance mobile payment adoption. Drawing on UGT, our research demonstrates that technologies such as personalized AI can significantly contribute to the adoption of mobile payments. This study further deepens the understanding of the impact mechanism by which personalized AI influences users’ willingness to continue using mobile payments. While previous studies have primarily focused on the effects of innovation on consumer satisfaction or loyalty [76], this research validates the role of personalization in shaping consumers’ continued usage intentions through the lens of usage and satisfaction theory.

Our results show that personalized products or services can meet consumers’ needs, and they are more likely to adopt them [36,37]. In addition, personalization is not only reflected in technological optimization, but also involves interaction between consumers and the system. That is, personalized services driven by AI can more accurately identify user needs and make corresponding adjustments based on these needs, thereby improving user stickiness and enhancing long-term user commitment [33], further verifying how personalized services promote the adoption of mobile payments by improving user experience [6]. At the same time, the application of personalized technology, such as personalized recommendation systems based on artificial intelligence and big data, enables enterprises to better predict the needs of different consumer groups, optimize personalized services, and thereby increase users’ willingness to continue using [35].

Second, this paper further contributes to IS and business studies by integrating the UGT with a contingency perspective. In prior research, few studies have applied personal characteristics from contingency theory in this context. To address this research gap, the present study explores the effects of different moderating variables, revealing how consumers exhibit different response mechanisms to AI personalization under varying individual circumstances. These findings not only broaden the applicability of personalization research but also provide new theoretical foundations for future studies on the interaction between individual differences and technology adaptability. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine these moderating effects, which represents a key academic contribution.

Drawing on the contingency perspective, we identify and empirically validate four moderating variables—two individual factors (educational level and age) and two external factors (social network and technological diversity). Regarding individual factors, we found that age restrains the relationship, while a high level of education is a positive influence. This suggests that the understanding of AI services, which tends to vary by age and education, plays a critical role in sustaining continued mobile payment usage.

For external factors, both social network and technological diversity were found to enhance the relationship. Our findings indicate that recommendations or experiences shared by other users can reinforce an individual’s willingness to continue using mobile payments. Likewise, a wider variety of mobile payment technologies leads to more frequent and seamless user experiences, thereby strengthening the continued use of the service [77,78].

Through the empirical validation of these four factors, our study reveals the dynamics that strengthen or weaken the relationship between personalized AI and continued mobile payment use. We demonstrate that both internal (e.g., age and education) and external (e.g., social network and technological diversity) environmental factors can significantly affect this relationship. While previous research has largely focused on individual factors, the effect of external factors has remained underexplored. In this regard, our study offers a novel perspective and a distinct academic contribution. Our findings also highlight that the external environment is not merely a background factor, but an active component shaping user behavior—an unprecedented approach in mobile payment research. This integration provides a new theoretical perspective, positioning personalized artificial intelligence as a contingent technological stimulus rather than a universally effective tool, whose impact varies depending on individual abilities and environmental backgrounds.

Finally, this study shifts the theoretical focus of mobile payment research from initial adoption to continuous use, thereby advancing the development of this field. Most mobile payment research has been based on models such as the TAM or the UTAUT, which focus on initial adoption rather than long-term retention. As a result, our understanding of the factors influencing mobile payment user retention remains limited. This study contributes to the literature on the sustainability of emerging technologies, indicating that continuous algorithm adaptation, rather than one-time practicality, is the key driving factor for user retention.

Furthermore, empirical studies examining how technologies like AI impact continued use are scarce. To date, only a few studies—such as Ahmed and Aziz (2024) [6] and Jun (2018) [56]—have briefly touched on this research area. In this regard, our study not only addresses this critical research gap but also contributes to the extension of mobile payment research.

Our findings demonstrate that the integration of technologies such as personalized AI, combined with various internal and external factors, significantly influences user retention. From this perspective, our study offers valuable and insightful implications on a practical basis and academic basis for future research into mobile payments.

5.3. Practical Implications

In practice, this study has important implications for personalized marketing strategies and AI technology application optimization for firms and managers. First, the findings underscore the central role of personalization in shaping consumers’ continued usage intentions. Firms in the mobile payments and digital service industries should therefore invest in the ongoing enhancement of algorithmic capabilities, leveraging AI and big data analytics to deliver more precise content recommendations and feature customization. Providing services that closely match individual user preferences can significantly improve user experience and promote long-term engagement. Second, the results highlight the amplifying effect of social influence on personalized services. Companies should strengthen social engagement mechanisms—such as social media campaigns and community-building initiatives—to foster user interaction and encourage the sharing of personalized experiences. Such strategies not only enhance the platform’s social value but also broaden the diffusion and visibility of personalized services.

Third, for highly educated users who demand greater functional depth and information quality, firms should develop more advanced and specialized AI-driven personalization modules. For example, FinTech platforms may offer fine-grained investment portfolio recommendations, while online education providers can generate individualized learning pathways based on users’ learning trajectories. Tailoring services to these higher-level needs can further elevate users’ perceived value. Fourth, given that technological diversity may weaken the effectiveness of personalization, firms should expand the adaptability of their systems across usage contexts. Achieving seamless consistency across devices (e.g., smartphones and tablets) and platforms (e.g., apps and web interfaces) can prevent fragmentation and ensure a coherent personalized experience. Enhancing multi-terminal compatibility strengthens the overall sense of continuity. Finally, firms should design stratified personalization strategies that address age-based differences in technology adoption and interaction preferences. Younger users may respond more positively to innovative, interactive, and gamified personalization features, whereas older users may benefit from simplified interface design, greater ease of use, and enhanced interaction security. Such differentiated strategies ensure that personalized services remain accessible, relevant, and effective for diverse user groups.

6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study is not without limitations. First, although questionnaires are a widely used research method, reliance on subjective scales may introduce common methodological biases. Moreover, the sample—primarily composed of Chinese users and younger individuals who are already familiar with AI and mobile payment systems—may limit the generalizability of the findings to broader populations or real-world contexts. In addition, the results may not fully capture potential negative responses to personalization, such as recommendation overload or privacy concerns, which could influence users’ continued usage intentions. Future research could integrate secondary data and additional data sources to enhance the robustness of the conclusions. Furthermore, exploring additional moderating variables may help uncover more complex mechanisms underlying the relationship between personalized AI and sustained usage intentions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.L.; methodology, N.L.; writing—original draft preparation, N.L.; writing—review and editing, E.T.L.; visualization, N.L.; supervision, E.T.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Sejong University, No. SUIRB-HR-2025050.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Scale items design of the survey questionnaire.

Table A1.

Scale items design of the survey questionnaire.

| Variables | Item | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Personalized AI | When using personalized AI features in the mobile payment app I usually use, I feel satisfied. | Wu et al., 2018; Ahmed & Aziz, 2024 [6,70] |

| The personalized AI services in my mobile payment app—such as intelligent recommendations—provide me with a pleasant user experience. | ||

| I think the personalized AI functions in the mobile payment system I use have improved the quality of my digital interactions. | ||

| The personalized AI services integrated in my preferred mobile payment app meet my expectations for convenience and efficiency. | ||

| Social network | I think social networks are very useful. | Venkatesh et al., 2003; Carnabuci & Diószegi, 2015 [57,73] |

| I often check my social networks every day. | ||

| I like to follow my friends’ sharing on social media. | ||

| I usually check what my friends are doing on social networks. | ||

| Technological diversity | I will use different devices to make mobile payments. | Lee & Li, 2024 [41] |

| I can use mobile payments on different devices. | ||

| I will use different operating systems for mobile payments. | ||

| I can use different payment functions. | ||

| Intention to continue using mobile payment | I plan to increase my usage of mobile payments in the future. | Venkatesh et al., 2012; Liao & Lu, 2008 [71,72] |

| I will use mobile payments regularly in the future. | ||

| I will recommend to others. | ||

| I will continue to use mobile payments for transactions. |

References

- De Luna, I.R.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; Sánchez-Fernández, J.; Muñoz-Leiva, F. Mobile payment is not all the same: The adoption of mobile payment systems depending on the technology applied. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 146, 931–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, K. Exploring the Impact of Self-Concept and IT Identity on Social Media Influencers’ Behavior: A Focus on Young Adult Technology Features Utilization. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2023, 40, 6941–6952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T. An empirical examination of continuance intention of mobile payment services. Decis. Support Syst. 2013, 54, 1085–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, A.B.; Bilgihan, A.; Nusair, K.; Okumus, F. What keeps the mobile hotel booking users loyal? Investigating the roles of self-efficacy, compatibility, perceived ease of use, and perceived convenience. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 1350–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlberg, T.; Mallat, N.; Ondrus, J.; Zmijewska, A. Past, present and future of mobile payments research: A literature review. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2008, 7, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Aziz, N.A. Impact of AI on Customer Experience in Video Streaming Services: A Focus on Personalization and Trust. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2024, 41, 7726–7745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Lu, Y.; Wang, B. Integrating TTF and UTAUT to explain mobile banking user adoption. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qatawneh, N.; Al-Okaily, A.; Al-Okaily, M.; Ur Rehman, S. Exploring the antecedent factors of continuous intention to use mobile money: Insights from emerging markets. Digit. Policy Regul. Gov. 2025, 27, 175–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baryannis, G.; Validi, S.; Dani, S.; Antoniou, G. Supply chain risk management and artificial intelligence: State of the art and future research directions. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2019, 57, 2179–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigam, A.; Pasricha, R.; Singh, T.; Churi, P. A systematic review on AI-based proctoring systems: Past, present and future. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2021, 26, 6421–6445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchiori, D.M.; Mainardes, E.W.; Rodrigues, R.G. Do Individual Characteristics Influence the Types of Technostress Reported by Workers? Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2018, 35, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. An empirical analysis of the antecedents of electronic commerce service continuance. Decis. Support Syst. 2001, 32, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, I.; Jiang, W.; Karolyi, G.A. To FinTech and beyond. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2019, 32, 1647–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PwC. It’s time for a consumer-centered metric: Introducing ‘return on experience’. In Global Consumer Insights Survey; PwC: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, A.M. Ritualized and instrumental television viewing. J. Commun. 1984, 34, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosengren, K.E. Uses and gratifications: A paradigm outlined. Uses Mass Commun. Curr. Perspect. Gratif. Res. 1974, 3, 269–286. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, D.; Chan, L.S.; Du, N.; Hu, X.; Huang, Y.T. Gratification and its associations with problematic internet use: A systematic review and meta-analysis using Use and Gratification theory. Addict. Behav. 2024, 155, 108044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Cho, C.H. Uses and gratifications of smart speakers: Modelling the effectiveness of smart speaker advertising. Int. J. Advert. 2020, 39, 1150–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Kitchen, P.J.; Kim, J. The effects of gamified customer benefits and characteristics on behavioral engagement and purchase: Evidence from mobile exercise application uses. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 92, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, K.; Downes, E.J. An analysis of young people’s use of and attitudes toward cell phones. Telemat. Inform. 2003, 20, 349–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, J.; Maier, E.; Wilken, R. The effect of credit card versus mobile payment on convenience and consumers’ willingness to pay. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.; Mela, C.F. E-customization. J. Mark. Res. 2003, 40, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.; Luo, X.; Xu, B. Personalized mobile marketing strategies. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, H.; Techatassanasoontorn, A.A.; Tan, F.B. Antecedents of consumer trust in mobile payment adoption. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2015, 55, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarifis, A.; Fu, S. Re-evaluating trust and privacy concerns when purchasing a mobile app: Re-calibrating for the increasing role of artificial intelligence. Digital 2023, 3, 286–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kourouthanassis, P.; Boletsis, C.; Bardaki, C.; Chasanidou, D. Tourists responses to mobile augmented reality travel guides: The role of emotions on adoption behavior. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2015, 18, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, F.R.; Schurr, P.H.; Oh, S. Developing buyer-seller relationships. J. Mark. 1987, 51, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, K.J.; Sundar, S.S. Customization in location-based advertising: Effects of tailoring source, locational congruity, and product involvement on ad attitudes. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 51, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, G.D.; Dao, T.H.T. Factors influencing continuance intention to use mobile banking: An extended expectation-confirmation model with moderating role of trust. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polak, P.; Nelischer, C.; Guo, H.; Robertson, D.C. “Intelligent” finance and treasury management: What we can expect. Ai Soc. 2020, 35, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunikka, A.; Bragge, J. Applying text-mining to personalization and customization research literature–Who, what and where? Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 10049–10058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, A.L.; Smith, M.D. Prospects for Personalization on the Internet. J. Interact. Mark. 2009, 23, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.W.; Lim, H.S.; Oh, J. “We think you may like this”: An investigation of electronic commerce personalization for privacy-conscious consumers. Psychol. Mark. 2021, 38, 1723–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.Y.; Ho, S.Y. Web personalization as a persuasion strategy: An elaboration likelihood model perspective. Inf. Syst. Res. 2005, 16, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegger, A.S.; Merfeld, K.; Klein, J.F.; Henkel, S. Technology-enabled personalization: Impact of smart technology choice on consumer shopping behavior. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 181, 121752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y. The privacy–personalization paradox in mHealth services acceptance of different age groups. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2016, 16, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komiak, S.Y.; Benbasat, I. The effects of personalization and familiarity on trust and adoption of recommendation agents. MIS Q. 2006, 30, 941–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.M. The impact of perceived value and trust on mobile payment reuse intention: The mediating role of user satisfaction. Int. J. Mob. Commun. 2025, 25, 62–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, K.P.; Vogel, D.R. An Exploratory Study of Personalization and Learning Systems Continuance. In Proceedings of the PACIS 2009 Proceedings, Hyderabad, India, 10–12 July 2009; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, L. The Contingency Theory of Organizations; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.T.; Li, X. Breaking status-quo inertial use of incumbent payment to adopt mobile payment: A contingency perspective. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 4275–4287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Ortega, B.; Serrano-Cinca, C.; Gomez-Meneses, F. The firm’s continuance intentions to use inter-organizational ICTs: The influence of contingency factors and perceptions. Inf. Manag. 2014, 51, 747–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.S.; Wang, C.H. Antecedences to continued intentions of adopting e-learning system in blended learning instruction: A contingency framework based on models of information system success and task-technology fit. Comput. Educ. 2012, 58, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavdar Aksoy, N.; Tumer Kabadayi, E.; Yilmaz, C.; Kocak Alan, A. A typology of personalisation practices in marketing in the digital age. J. Mark. Manag. 2021, 37, 1091–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzogbenuku, R.K.; Amoako, G.K.; Kumi, D.K.; Bonsu, G.A. Digital payments and financial wellbeing of the rural poor: The moderating role of age and gender. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2022, 34, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; Sánchez-Fernández, J.; Muñoz-Leiva, F. Antecedents of the adoption of the new mobile payment systems: The moderating effect of age. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 35, 464–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Liang, H.N.; Yu, K.; Wen, S.; Baghaei, N.; Tu, H. Acceptance of virtual reality exergames among Chinese older adults. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2023, 39, 1134–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Wang, G.; Huang, C. What promotes the mobile payment behavior of the elderly? Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cham, T.H.; Cheah, J.H.; Cheng, B.L.; Lim, X.J. I Am too old for this! Barriers contributing to the non-adoption of mobile payment. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2022, 40, 1017–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, S.C.; Awa, H.O.; Chinedu-Eze, V.C.; Bello, A.O. Demographic determinants of mobile marketing technology adoption by small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Ekiti State, Nigeria. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strzelecki, A. To use or not to use ChatGPT in higher education? A study of students’ acceptance and use of technology. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2024, 32, 5142–5155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodnow, W.E. The contingency theory of education. Int. J. Lifelong Educ. 1982, 1, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riddell, W.C.; Song, X. The role of education in technology use and adoption: Evidence from the Canadian workplace and employee survey. ILR Rev. 2017, 70, 1219–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Ray, G.; Sambamurthy, V. Efficiency or Innovation: How Do Industry Environments Moderate the Effects of Firms’ IT Asset Portfolios? MIS Q. 2012, 36, 509–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chursin, A.A.; Dubina, I.N.; Carayannis, E.G.; Tyulin, A.E.; Yudin, A.V. Technological platforms as a tool for creating radical innovations. J. Knowl. Econ. 2021, 13, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, J.; Cho, I.; Park, H. Factors influencing continued use of mobile easy payment service: An empirical investigation. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2018, 29, 1043–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnabuci, G.; Diószegi, B. Social networks, cognitive style, and innovative performance: A contingency perspective. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 881–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sledgianowski, D.; Kulviwat, S. Using social network sites: The effects of playfulness, critical mass and trust in a hedonic context. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2009, 49, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, S.; Jie, W. Exploring the impact of artificial intelligence application in personalized learning environments: Thematic analysis of undergraduates’ perceptions in China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellman, B. Designing the Internet for a networked society. Commun. ACM 2002, 45, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Lu, Y.; Gupta, S.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, R. Mobile payment services adoption across time: An empirical study of the effects of behavioral beliefs, social influences, and personal traits. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahanna, E.; Straub, D.W.; Chervany, N.L. Information technology adoption across time: A cross-sectional comparison of pre-adoption and post-adoption beliefs. MIS Q. 1999, 23, 183–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahanna, E.; Xu, S.X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, N. The needs–affordances–features perspective for the use of social media. MIS Q. 2018, 42, 737-A23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Gong, H. From Seeking to Sharing: Pathways of Environmental Risk Information on Social Media and the Roles of Outcome Expectations, Efficacy, and AI-Generated Content. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 11378–11391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preece, J. Online Communities: Designing Usability and Supporting Socialbilty; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Zhao, L.; Hu, C. The mechanism through which members with reconstructed identities become satisfied with a social network community: A contingency model. Inf. Manag. 2019, 56, 103144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, M.A. Sparkling fountains or stagnant ponds: An integrative model of creativity and innovation implementation in work groups. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 51, 355–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Yan, X.; Tsai, C.L. Linear regression. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Comput. Stat. 2012, 4, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westland, J.C. Structural equation models. Stud. Syst. Decis. Control 2015, 22, 152. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Chen, L.; Zhao, Y. Personalizing recommendation diversity based on user personality. User Model. User-Adapt. Interact. 2018, 28, 237–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.L.; Lu, H.P. The role of experience and innovation characteristics in the adoption and continued use of e-learning websites. Comput. Educ. 2008, 51, 1405–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Xu, X. Consumer Acceptance and Use of Information Technology: Extending the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleier, A.; Harmeling, C.M.; Palmatier, R.W. Creating effective online customer experiences. J. Mark. 2019, 83, 98–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedkin, N.E. Structural Bases of Interpersonal Influence in Groups: A Longitudinal Case Study. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1993, 58, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.Y.; Bodoff, D. The effects of web personalization on user attitude and behavior. MIS Q. 2014, 38, 497–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).