Abstract

With the rapid development of live streaming e-commerce, opening live streaming sales channels for online product sales has become an important strategic priority for enterprises. This paper examines information technology-driven operational decisions in live streaming e-commerce supply chains, including sales mode selection, technology investment, and information sharing. We develop game-theoretic models for reselling and agency selling modes under three scenarios: no technology investment, investment without information sharing, and investment with information sharing. Our findings show that under the reselling mode, e-tailers tend to accept information sharing when the live streaming creates high extra value or when the market demand is underestimated. Under the agency mode, e-tailers usually reject sharing. Regarding technology investment, platforms are motivated to invest under the reselling mode when the market is underestimated regardless of sharing; in contrast, under the agency mode, platforms only invest when e-tailers accept sharing and the market is severely underestimated, the sharing fee is moderate, and the agency fee and hassle cost are low. A win-win outcome arises when the agency fee is low and live streaming generates low extra value with high hassle costs, making the agency optimal for both e-tailers and platforms; conversely, when the agency fee is high and live streaming generates high extra value with low hassle costs, the reselling becomes optimal. This study provides important strategic guidance and policy insights for supply chain members, enabling firms to make better decisions and thus gain a competitive advantage in the face of fierce market competition.

1. Introduction

In recent years, live streaming e-commerce (LSC) has become a significant marketing phenomenon for addressing traffic saturation issues on online platforms. It has gradually developed into a supplementary sales channel. The market size of China’s live commerce is expected to reach RMB 19 trillion by 2029, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of approximately 30% [1]. In the United States, the live commerce market was valued at USD 1.749 billion in 2024 and is forecasted to grow to USD 8.269 billion by 2030, with a CAGR of 30.3% from 2025 to 2030 [2]. To seize this growth opportunity, major e-commerce platforms have been actively developing their own live commerce. Platforms such as Taobao and JD.com are among the first to integrate live streaming into their operations, forming a relatively mature business mode. In parallel, platforms including Amazon, Shopee, and Lazada have also expanded their live streaming capabilities to facilitate more interactive engagement between sellers and consumers. These developments suggest that LSC has become an important global trend and will play an increasingly relevant role in the evolution of online retail.

Driven by the rapid expansion of online retail, two predominant sales modes, reselling and agency selling, have been widely adopted by e-commerce platforms and e-tailers. Under the reselling mode, platforms purchase products directly from e-tailers and subsequently resell them to end consumers, effectively functioning as retailers. This sales mode is commonly employed by platforms such as Walmart.com, Gome.com, and Suning.com [3]. In contrast, the agency selling mode allows e-tailers to maintain ownership of products and sell directly to end consumers via platforms that act primarily as intermediary marketplaces and earn revenue through agency fees. Platforms that mainly adopt this mode include Shopee, Pinduoduo, and Lazada [4]. Recently, leading platforms such as Amazon, Taobao, and JD.com have been gradually moving away from the reselling mode to the agency selling mode. For example, in the “Spring Dawn Plan” launched by JD.com in 2023, the platform actively encouraged more third-party merchants to join by introducing a series of supportive measures, including lowering entry threshold, simplifying the entry process, and reducing deposit requirements [5].

At present, most e-tailers typically have two main sales channels: the traditional platform channel (including reselling or agency selling modes) and the live streaming sales channel. In the development of LSC, streamers generally enter into one of three types of contractual relationships: with platforms, with multi-channel network (MCN) organizations, or directly with e-tailers. In recent years, several major scandals involving top streamers have put platforms and merchants at great risk. For example, in December 2021, the well-known streamer Viya was fined for tax evasion, resulting in many products being suddenly removed from shelves. The incident caused significant financial losses to e-tailers and damaged Taobao’s reputation. Therefore, more and more e-tailers prefer to sign contracts with ordinary streamers to strengthen the management of their behavior. In this context, e-tailers have established live streaming rooms within their stores on e-commerce platforms to allow streamers to sell products directly to consumers. According to a report by IResearch Company, the mode in which e-tailers sign contracts with store streamers and conduct live stream sales has become mainstream, with such streamers accounting for nearly 90% in the market. The recruitment, management, and operation of streamers have increasingly become an integral part of e-tailers’ daily business practices [6]. However, most existing studies focus on the collaboration between streamers and platforms or MCN organizations, while research on sales channels formed by direct contracts between e-tailers and streamers remains limited. Therefore, this paper focuses on the live streaming sales channel established through contracts between e-tailers and streamers (referred to as the streamer channel to highlight the intermediary role of streamers, similar to that of platforms) and investigates the operational decisions within a dual-channel LSC supply chain composed of the platform channel and the streamer channel.

The global supply chain landscape is now frequently disrupted by major, high-impact events. These include instances such as the 2004 tsunami, the 2014 Ebola crisis in West Africa, the COVID-19 pandemic’s global scope, and ongoing shifts in international trade policy. These uncertainties often lead to sharp fluctuations in demand, complicating operational decisions across supply chains. In the absence of accurate information, supply chain members may make suboptimal decisions due to information asymmetry and thereby reduce overall efficiency. As a result, establishing effective mechanisms for information collection and sharing is essential for strengthening both the coordination and inherent resilience of these networks. To address this challenge, with the rapid advancement of information technology (IT), firms are increasingly investing in tools such as Internet of Things (IoT), Internet of Vehicles (IoV), big data, blockchain, and cloud computing to monitor market dynamics in real time and obtain more accurate demand information. However, such investments are often costly, and not all supply chain members, particularly small and medium-sized retailers, have the necessary resources to adopt these technologies. As a result, large e-commerce platforms often take the lead in IT investment and function as central hubs for data collection and processing. By investing in these technologies and establishing information sharing contracts, platforms can provide e-tailers with valuable demand information and thereby improve the overall responsiveness and coordination efficiency of supply chains. For example, JD.com has developed the “Jinghui” integrated intelligent supply chain platform, leveraging information technologies such as big data analytics and intelligent algorithms to provide businesses with decision support for demand forecasting, inventory alerts, and smart replenishment, earning wide recognition from numerous firms.

Inspired by the above analysis, this paper studies strategic decisions covering pricing, IT investment, and information sharing in a dual-channel LSC supply chain consisting of one platform and one e-tailer with streamer channels. Both reselling and agency selling modes are considered under random demand perturbations. Our objective is to address the following key research questions:

Q1: Under what conditions is the platform consistently incentivized to invest in IT to secure accurate demand information?

Q2: Is the e-tailer always willing to accept information sharing?

Q3: What are the preferences of supply chain members between reselling and agency selling modes?

Q4: Can IT investment and information sharing improve supply chain coordination?

To address these questions, this paper considers three scenarios under reselling and agency selling modes: (i) The platform does not invest in IT and hence both the platform and the e-tailer only possess expected demands. (ii) The platform acquires accurate demand information through IT investment, but the e-tailer declines the sharing contract and continues to rely on expected demand data. (iii) Following the platform’s IT investment, the accurate information is successfully transferred, resulting in precise demand data being available to both entities. LSC, driven by real-time dynamics, generates substantial information asymmetry and strategic interdependence (e.g., technology investment conditional on information sharing) between the platform and e-tailers. As traditional optimization models fail to capture this complex strategic environment, we develop a multi-stage game model across these scenarios, conducting a comparative analysis of equilibrium profits to derive robust managerial insights.

The main contributions of this paper lie in the structural innovation of the theoretical model and the integration of key operational decisions. First, concerning the research architecture, this study constructs a theoretical model for a specific LSC structure where the e-tailer operates its own live streaming room on the platform. This significantly expands the theoretical boundaries of the existing literature on emerging LSC operational modes, contrasting with prior work (e.g., [7,8,9,10]) that focuses on traditional or simplified e-commerce channels. Second, we thoroughly analyze the strategic choice between reselling and agency selling modes within the dual-channel LSC (platform and streamer channels), thus endogenizing the sales mode selection. Most critically, this study achieves an innovative integration of multiple operational decisions. Distinguishing our work from papers focused on pricing decision (e.g., [11]) or purely empirical analyses (e.g., [12]), our model is to integrate IT investment and information sharing within the composite framework of random demand volatility and sales mode selection. This not only provides a new perspective for assessing the comprehensive value of information in supply chains but also marks a breakthrough in the theory of supply chain coordination mechanisms for information asymmetry.

The main findings of our research can be summarized as follows. Firstly, in the selling mode, the e-tailer is more inclined to accept information sharing contracts when the extra value generated by live streaming sales is high or when market demand is underestimated, while high streamer commissions, high consumer hassle costs, or overestimated demand reduce its willingness to accept information sharing. Moreover, in the agency selling mode, the e-tailer tends to reject information sharing contracts under relatively stable market conditions. Only when the market is severely underestimated, the information sharing cost is moderate, and both the agency rate and hassle cost are low does the e-tailer tend to accept such contracts. Secondly, the platform’s IT investment strategy also varies by sales mode. In the reselling mode, the platform has investment incentive when demand uncertainty is large or when the market is underestimated, regardless of whether information is shared. However, in the agency selling mode, the platform does not invest in IT if the e-tailer does not accept information sharing. Moreover, the platform is willing to invest when the e-tailer accepts information sharing and the market is severely underestimated the information sharing fee is moderate, and both the agency fee and the hassle cost are low. Thirdly, with respect to sales mode selection, the e-tailer prefers the reselling mode when the agency fee is high. When the agency fee is low, it tends to choose the agency mode if the extra value generated by live streaming is limited and the hassle cost is high; otherwise, it still prefers the reselling mode. However, the e-tailer’s optimal choice is not always optimal for the platform. A win-win result between the platform and the e-tailer can only be achieved under the following two conditions: (i) When the agency fee is low, the extra value is low, and the hassle cost is high, the agency mode is optimal for both parties. (ii) When the agency fee is high, the extra value is high, and the hassle cost is low, the reselling mode is optimal for both parties. Finally, regardless of reselling or agency selling mode, when the platform invests in IT and the e-tailer accepts information sharing, supply chain coordination can be achieved if the extra value generated by live streaming is high. The platform should establish a reasonable fixed fee for opening live streaming rooms to attract e-tailers, and e-tailers should provide a low base salary and a moderate unit commission to streamers to protect their own income and effectively motivate streamers.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 summarizes and reviews the related literature. Section 3 lays out the problem description and clarifies the sequence of the game. The core of our model is formulated in Section 4, establishing a five-stage game where the e-tailer selects between reselling/agency selling and accepting/rejecting information sharing, while the platform determines its IT investment. The equilibrium strategies for the supply chain members are derived and analyzed in Section 5, Section 6 and Section 7. Section 8 presents a discussion of supply chain coordination and live streaming channels. Lastly, Section 9 concludes this study and suggests avenues for further exploration. All mathematical proofs are provided in Appendix B.

2. Literature Review

We review three streams of research in the literature related to our research: live streaming e-commerce, channel selection strategy, and information collection and sharing.

2.1. Live Streaming E-Commerce (LSC)

As a popular sales channel in recent years, LSC has attracted extensive attention from both academia and industry. Empirical research on LSC is relatively well established, particularly in exploring consumer viewing and shopping motivations [13,14]. Some other scholars have focused on developing strategies to enhance consumer engagement and trust, thereby increasing purchase intention [12,15,16,17]. Modeling studies are relatively scarce compared to empirical studies, but they are emerging currently.Yang et al. investigate the strategic selection among three compensation schemes: a basic plan, a salary-based incentive, and a commission-based incentive. They further analyze which mechanism the platform should adopt to most effectively motivate streamers [18]. Zhang and Xu study incentive mechanisms for engaging consumers in value co-creation and explore their impact on the optimal sales strategy selection [19]. Moreover, many scholars have studied the strategic choice between live streaming and conventional e-commerce sales channels, along with the competitive impact of the former on the latter. Pan et al. show that adding live streaming sales channels increases retailers’ profits only if the selling power of streamers is high enough [20]. A comparison of merchant and influencer live streaming channels by [21] demonstrates that the influencer mode is not consistently the most effective. Zhang et al. examine operation strategies in the LSC supply chain through three models, and they show that the introduction of live streaming sales channels is beneficial to both the e-commerce platform and streamers [22]. Xiao et al. investigate risk sharing in the LSC supply chain; this research reveals that the streamer’s hybrid commitment mechanism fosters superior coordination between seller inventory and streamer effort, yielding mutual benefits for both parties [23]. Lu et al. examine a retailer’s optimal information sharing policy regarding demand with a manufacturer who may potentially establish a live streaming sales channel with a streamer [24].

Our study contributes to the literature stream examining mode selection in LSC. In contrast to previous works that solely focus on the selection between reselling and agency selling modes, our study explores optimal mode selection in more complex scenarios involving information collection and sharing. Another key contribution of our study is the incorporation of IT investments and information sharing in LSC.

2.2. Reselling and Agency Selling

Online platforms often adopt various sales modes, with reselling and agency selling being the most prevalent. The strategic selection between reselling and agency selling modes has been widely discussed, particularly their inherent trade-offs and relative advantages. Previous studies on this issue include single-channel [9,25,26] and multi-channel modes [27,28]. This study contributes to the selection of reselling and agency selling modes in multiple channels.From an alternative perspective, existing research has explored this issue by focusing on driving factors such as product quality [29], channel competition [7], information asymmetry [30,31], and marketing activity [7,32]. In contrast, our research focuses on LSC and information collection and sharing. We next review the literature on the selection of reselling and agency selling modes from these two aspects.

Table 1 summarizes the correlations and differences between this study and the most related studies. One the one hand, Hao and Yang consider the issue of mode selection including live streaming channels. Notably, the live streaming channel is considered as a general sales channel that includes both reselling and agency selling models [33]. Ji et al. analyze the channel selection issues and price discount strategies of the LSC supply chain [34]. Wang et al. analyze the issue of mode choice in a dual channel consisting of live streaming and common sales [11]. One the other hand, Zhang and Zhang examine the issue of mode selection when an e-tailer shares market information with a supplier who is simultaneously planning to enter the offline market [31]. Lin et al. consider that manufacturers and their resellers usually use online intermediaries to sell products. These intermediaries usually have superior demand information and decide whether to share it with sellers. They further compare the manufacturers’ choice of reselling and agency selling modes [35].

Table 1.

Comparison between our study and relevant studies.

Our research examines the choice between reselling and agency selling models in the context of IT investment and information sharing in LSC. The innovation of this study lies in placing the choice between resale and consignment models within the unique context of the emerging LSC and constructing a unified analytical framework to simultaneously examine two key interdependent strategic decisions: the platform’s IT investment decisions (to reduce demand uncertainty) and the merchant’s information sharing strategies (to optimize supply and demand matching). This integrated approach allows us to move beyond single-factor analysis and systematically define which sales models, within the LSC channel, can maximize channel coordination and profit sharing.

2.3. Information Collection and Sharing

In the era of limited IT, supply chain members often lacked access to accurate market information, leading to poor decisions. However, with the rapid advancement of technology such as big data, cloud computing, AI, IoT, IoV, and blockchain, members can make optimal decisions by investing in these technologies to gather accurate market information. This shift has significant implications for business operations and supply chain management. Some of the literature focuses on collecting information. Huang and Rust employ AI to collect information for strategic marketing planning [36]. Zhao et al. consider that investing in IT at a certain cost can obtain accurate demand information without focusing on specific IT [37].

Integrating information sharing into supply chain management is essential for enhancing overall performance [38]. Guided by the principle of win-win cooperation, demand information sharing among supply chain members has received extensive attention. Specifically, competing retailers are often more inclined to disclose demand information to suppliers under confidentiality agreements [39,40]. Huang et al. study the motivation of retailers to share demand information with suppliers with invasion capabilities, who may invade the market at fixed costs [41]. Zhang and Zhang consider the offline expansion strategies of suppliers under reselling or agency selling modes and explore the incentive mechanism for e-tailers to share demand information [31].

Building on the rapid growth of e-commerce, a growing number of studies have initiated research into demand information sharing involving platforms, a field to which this paper contributes. In particular, Zhang et al. explore product quality decision-making in platform sales, where the platform possesses market data and can share it with manufacturers via contracts [29]. Cao et al. analyze the platform’s demand information sharing strategy and the resulting impact of extreme weather-induced demand disruptions on the operational strategies of both the platform and the enterprises [42]. In the aforementioned literature, at least one of the supply chain members possesses demand information. In contrast, Zhao et al. examine a setting in which demand information is not readily available to any supply chain party; instead, the platform is required to make an IT investment to secure it [37]. Zha et al. investigate an online platform’s strategy for sharing demand information in a dual-channel distribution setting, where the manufacturer sells products via both the platform and independent sellers [43].

This paper considers platform investment in demand information acquisition. Differing from prior research, we jointly examine the dual strategic decisions of platform IT investment for demand information acquisition and e-tailer information sharing within the context of LSC. This integrated approach enables us to comprehensively assess how these interdependent information and technology strategies influence channel coordination and profitability in the emerging digital environment.

3. Problem Description

3.1. The Platform, the E-Tailer, and the Streamer

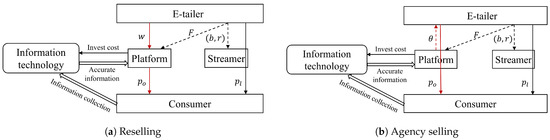

Consider a dual-channel e-commerce supply chain consisting of a platform (he), an e-tailer (she), and a streamer where the e-tailer sells products to end consumers via dual distribution channels: a streamer sales channel and a platform sales channel. The supply chain structure is shown in Figure 1. This dual-channel sales mode is very common in actual situations, such as JD.com and Amazon, but there are few studies in the literature conducting in-depth model research on this. To establish a live streaming sales channel on the platform, the e-tailer needs to pay a fixed fee F to the platform and recruit streamers. The e-tailer pays the streamer through a salary mechanism , where b represents a fixed salary and r denotes a unit commission. Since the e-tailer has already established a live streaming room and recruited the streamer when setting prices, we assume that F, b, and r are exogenous parameters. Moreover, the e-tailer determines the selling price in the live streaming channel due to the fact that the streamer, being contracted by the e-tailer and acting as an internal sales employee, has no pricing power. Given that the e-tailer determines the pricing in both cases, the live streaming channel shares some similarities with the traditional direct selling channel. However, there are fundamental differences between them: First, in the live streaming channel, the e-tailer must share a portion of sales profits with the streamer as compensation, whereas in the direct selling channel, there is no such profit sharing with other supply chain members. Second, the live streaming channel is defined by its interactivity and real-time engagement, which contrasts with the static nature of the traditional direct selling channel.

Figure 1.

Dual-channel supply chain structure under reselling and agency selling.

The operational sequence for the platform sales channel begins with the e-tailer selecting either the reselling or agency selling mode with the platform. Following this, the platform makes its critical decision: whether to invest in new IT at a cost I to acquire precise market demand information. In particular, the IT investment cost is set as a fixed value I to reflect the fixed capital expenditure required for acquiring new systems or proprietary technology, thereby focusing the model on the key binary strategic decision of whether to invest. If the platform chooses not to invest, neither party gains access to accurate market data. Conversely, should the platform proceed with the IT investment, it then secures the accurate market information and is able to offer an information sharing contract to the e-tailer. The platform is willing to share market information with the e-tailer [37], because the e-tailer’s high sales may contribute to the platform’s long-term development. At this stage, the e-tailer decides whether to accept the platform’s information sharing contract. If the e-tailer accepts the contract, she gains access to accurate market information; otherwise, she cannot. Notations adopted in this paper are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

List of notations.

3.2. Market Demand

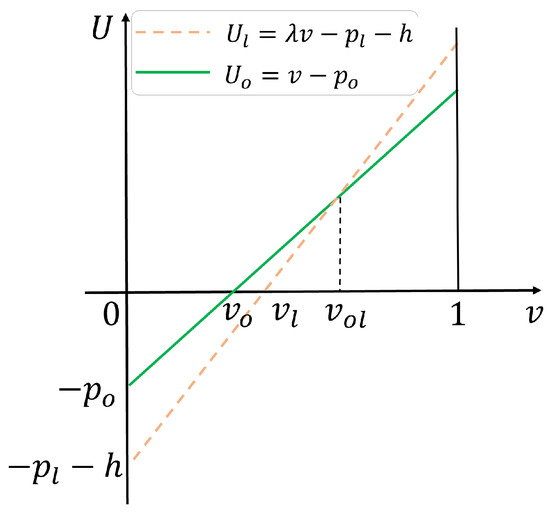

Consider a group of customers purchasing one unit of a product from either the platform channel or the streamer channel. Customers have heterogeneous valuation v for products, which is assumed to be uniformly distributed in the interval . The selling price in the platform channel is denoted by . Then, the utility of a consumer from purchasing a product through the platform channel is .

The streamer channel introduces distinct characteristics of LSC when benchmarked against the traditional platform channel. On the one hand, consumers enjoy the extra value from real-time interactions with the streamer or other consumers [12,44]. We assume that a consumer can obtain valuation when buying via the streamer channel, where is the potential to increase product value through live streaming. The parameter is a strategic metric measuring the unique value and sales efficacy of the streamer channel. Management should use to guide resource allocation and incentive strategies: a high signals strong channel competitiveness, justifying greater investment in top streamer talent and the design of higher performance-based incentives to maximize returns from this high value demand stream. Conversely, participation in live streaming incurs a hassle cost h for the consumer (e.g., time spent or search effort), instead of just a click and buy. (Abstracting the consumer hassle cost h as a constant is reasonable as it represents the average inherent cost of time and effort required for engaging with live content, simplifying the analysis to focus on how this cost acts as a strategic barrier influencing consumer purchasing intent in the LSC.) In addition, the parameter h is a critical metric for gauging consumer friction in the shopping experience. Management must target the reduction of h as a core operational objective: by improving the efficiency of live interaction, simplifying the purchasing journey (e.g., one-click buying), optimizing platform search, or offering viewing incentives, they can effectively lower the consumer’s time cost and cognitive load, thereby boosting conversion rates and user retention in the live channel. The seller charges a price in this channel; therefore, the utility a consumer derives from the streamer channel is .

Each consumer has three choices: leave the market, buy the product in the platform channel, or buy the product in the streamer channel. Consumers base their purchasing decision on utility maximization, formalized as . We define the indifference points based on utility thresholds: The point represents the consumer valuation at which a consumer is indifferent between using the platform channel and exiting the market (i.e., ), yielding the threshold . Similarly, is the valuation where a consumer is indifferent between utilizing the streamer channel and leaving the market (i.e., ), establishing the boundary . Finally, marks the valuation where a consumer is indifferent between the two competing channels (i.e., ), defining the crossover point . According to the expression of utility functions , and the size relationship of three indifference points , , and , these show the possible market divisions between the platform channel and the streamer channel, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Market segmentation under the platform channel and the streamer channel.

As shown in Figure 2, consumers whose valuations fall within the interval opt to exit the market. The customers whose valuations lie in the interval will purchase items exclusively via the streamer channel. The resulting demand function for this channel is

Conversely, consumers with valuations in the interval will buy products from the platform channel, and the corresponding demand function is

Given that high=impact events such as global pandemics and ongoing shifts in international trade policy frequently disrupt the market, demand randomness is a common and critical reality leading to sharp operational fluctuations across modern supply chains. Following [10,45,46], we assume the stochastic demands to be

where is a random variable reflecting the market potential uncertainty level. If new IT is obtained, the actual value can be observed; otherwise, only the prior distribution of is available, which is assumed to be uniformly distributed over the interval .

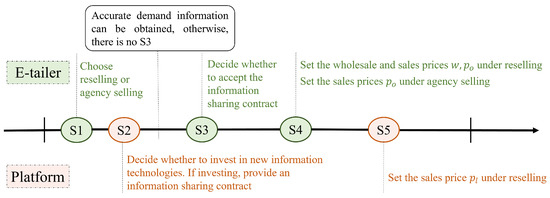

3.3. Sequence of Decisions

The sequence of decisions in this paper is shown in Figure 3. In the S1 stage, the e-tailer chooses a reselling mode or an agency selling mode with the platform. In S2, the platform decides whether to invest in new IT (denoted by I) or not (denoted by N). Reference [37] discusses this mode selection issue under traditional direct sales channel and selling channel. If the platform does not invest in new IT, the demand information is unknown. Thus, there is no S3, and so we turn directly to S4 and S5 instead. By investing cost I in new IT, the platform is able to acquire accurate demand information and, subsequently, he offers an information sharing contract to allow e-tailers to choose whether or not to participate. In S3, the e-tailer decides whether to accept (S) the information sharing contract or reject (N) it. In S4, the e-tailer sets the wholesale price w to the platform and the sales price in the streamer channel under the reselling mode. If an agency selling mode is adopted, the e-tailer sets the sales price in the streamer channel and in the platform channel. Under the agency selling mode, the platform grants the e-tailer permission to sell through its channel in exchange for an agency fee , representing the share of revenue retained by the platform per unit sold. We assume that the agency fee is exogenous because it is commonly applied in practice (e.g., Amazon, Taobao, JD.com) and is also widely used in platform pricing studies [7,8,47]. For example, Amazon adopts a 15/85 revenue split for product categories such as apparel, fashion, and skin care, where 85% of the revenue goes to the upstream e-tailer and 15% goes to Amazon, e.g., . In S5, the platform sets the sales price in the platform channel under the reselling mode.

Figure 3.

The sequence of decisions in this paper.

This is a multi-stage game and we utilize backward induction to identify the subgame perfect equilibria. The solution process is executed in three parts: First, we determine the subgame equilibria in S4 and S5 by solving the pricing decisions for every possible outcome resulting from S1 through S3. Second, using these derived subgame equilibria, we move backward to solve for the optimal strategies in S2 and S3. This step yields the equilibrium decisions concerning IT investment (platform) and information sharing (e-tailer). Finally, the optimal selling mode (reselling or agency selling) is determined in S1.

4. Models for S4 and S5

For either the reselling mode or agency selling mode, the platform decides whether to invest in new IT in S2. If the platform chooses to invest, he offers an information sharing contract. In S3, the e-tailer decides whether to accept this contract, leading to three possible outcomes in S4 to S5: Cases NN, IN, and IS. Throughout, we use superscripts “∼” and “∧” to denote the reselling case and the agency selling case, respectively.

4.1. Reselling Mode

Under the reselling mode, the e-tailer first sets the wholesale prices for the platform and the streamer channels. Subsequently, the platform sets the retail price for their own channel. This sequence of decisions forms a leader–follower game model, in which the e-tailer acts as the leader and the platform as the follower.

4.1.1. Case NN: No IT Investment

If the platform makes no investment in new IT, S3 is omitted and accurate demand information remains unavailable to both the platform and the e-tailer. In this scenario, the profit functions for the two parties are

respectively. Since the demands are influenced by the random variable and neither the e-tailer nor the platform has access to accurate demand information, they make their pricing decisions by maximizing their own expected profits and . The equilibrium outcomes are presented in Table A1.

4.1.2. Case IN: IT Investment Without Sharing

When the platform expends cost I on new IT, he gains access to the actual demand perturbation and subsequently offers an information sharing contract to the e-tailer. However, if the e-tailer chooses not to accept the contract, she does not obtain the actual demand perturbation. In this case, the profits of the e-tailer and the platform are

respectively. Since the platform has the actual demand perturbation while the e-tailer does not, the platform decides their pricing by maximizing their profit , whereas the e-tailer decides her pricing by maximizing her expected profit . The equilibrium outcomes are presented in Table A1.

4.1.3. Case IS: IT Investment with Sharing

When the platform expends cost I on new IT, he obtains access to the actual demand perturbation and then offers the e-tailer an information sharing contract. Under this contract, the platform charges a fixed fee for each unit of demand generated by the platform channel. In addition, setting the fixed fee as a fixed charge per unit of demand reasonably models the platform’s channel commission or operational rent for the utilization of its infrastructure and traffic by the e-tailer. In this case, the e-tailer accepts the information sharing contract and also obtains the actual demand perturbation. The profits for the e-tailer and the platform are

respectively. Since the platform and the e-tailer both know the actual demand perturbation, they decide their pricing by maximizing their profits and . The equilibrium outcomes are presented in Table A1.

4.2. Agency Selling Mode

Under the agency selling mode, the e-tailer sets the sales prices of the platform and streamer channels, while the platform does not engage in any decision-making. Therefore, an optimization model is formulated to maximize the profit of the e-tailer.

4.2.1. Case NN: No IT Investment

If the platform makes no investment in new IT, the accurate demand information cannot be disclosed. The profits for the e-tailer and the platform are

respectively. Without access to the accurate demand data, the e-tailer decides her pricing by maximizing her expected profits . Since the platform has no decision-making behavior and their profit depends on the e-tailer’s expected profit, he is also receiving the corresponding expected profit. The equilibrium outcomes are presented in Table A2.

4.2.2. Case IN: IT Investment Without Sharing

When the platform expends cost I on new IT, he can obtain the actual demand perturbation . Although the platform offers an information sharing contract to the e-tailer, she chooses not to accept it. The profits of the e-tailer and the platform are

respectively. Without access to the accurate demand information, the e-tailer decides the pricing by maximizing her expected profits . The equilibrium results are shown in Table A2.

It is worth noting that under the agency selling mode, if the e-tailer does not accept the information sharing contract, the platform’s investment decision does not affect the e-tailer’s profit. This is because the platform does not participate in any decision-making and the e-tailer always sets her pricing based on her expected profits. However, if the e-tailer chooses not to accept the information sharing contract and the platform invests in IT, the platform’s profitability will decrease due to the associated costs of the investment. Therefore, under the agency selling mode, if the e-tailer does not accept the information sharing contract, the platform should avoid investing in IT. In the case that the platform invests in IT, he should provide a reasonable information sharing contract to ensure that the e-tailer will accept it.

4.2.3. Case IS: IT Investment with Sharing

When the platform expends cost I on new IT, he can obtain the actual demand perturbation and then offers the e-tailer an information sharing contract. Under this contract, the platform charges a fixed fee for each unit of demand generated by the platform channel. In this case, the e-tailer accepts the information sharing contract and then obtains the actual demand perturbation . The profits for the e-tailer and the platform are

respectively. Since the e-tailer has the accurate demand information, she decides the pricing by maximizing her profit . The equilibrium results are shown in Table A2.

4.3. Equilibrium Results

By analyzing the equilibria for each case, we can obtain the equilibrium results in Proposition 1. See Appendix A for its proof. Note that the equilibrium feasibility conditions are primarily required to satisfy constraints such as non-negativity.

4.4. Insights on Pricing and Demand

In what follows, we compare equilibrium results across Cases NN, IN, and IS under the reselling mode or agency selling mode with a view to providing management insights. To focus our research problems closely, we analyze pricing and demand here, and in Section 5, Section 6 and Section 7, we delve into the analysis of firm’s profits. It should be noted that to make the results more concise, the conditions ensuring the existence of solutions are not detailed in the following analysis; however, all derivations are conducted under the assumption that these conditions hold. Through comparative studies of the optimal pricing and demand across different scenarios, Propositions 2 and 3 are drawn.

Proposition 2.

Under the reselling mode, the optimal wholesale prices, retail prices, and demands of the e-tailer and platform in Cases NN, IN, and IS satisfy the following relationships:

- (i)

- If or , . If , .

- (ii)

- If , , , , and . If , , , , and .

See the Appendix B for a proof of Proposition 2. This proposition presents a comparative analysis of pricing and demand across different cases in the reselling mode, which are mainly affected by the actual market perturbation and the fixed unit fee paid by the e-tailer to the platform upon accepting the information sharing contract. From Proposition 2, we conclude that under the reselling case, if the e-tailer does not accept the information sharing contract, the platform’s investment decision does not impact the wholesale price, as well as the pricing and demand in the e-tailer’s alternative sales channels, namely, the streamer channel.

Specifically, Proposition 2(i) shows that when the unit fee paid by the e-tailer to the platform is sufficiently large (i.e., ), the realized wholesale price exceeds the e-tailer’s initial expectations. This means that when external costs exceed internal risks (expectation deviation), merchants, in order to maintain survival and rational profits, will be forced to pass on the increased external costs to upstream suppliers by raising wholesale prices w, resulting in actual wholesale prices exceeding their initial optimal expectations. This reflects how when channel fees are too high, incentive compatibility forces merchants to adopt a more conservative (i.e., higher price) strategy. Moreover, Proposition 2(ii) reveals that if the actual perturbation exceeds the anticipated level, the realized prices and demands surpass those expected by both the platform and the e-tailer, and vice versa. This conclusion aligns well not only with the findings presented by [37] but also with practical real-world market behavior. In particular, a higher-than-expected perturbation suggests that participants underestimate the market potential, resulting in actual pricing and demand that exceed initial forecasts; conversely, overestimating the perturbation leads to the opposite effect. In addition, when the actual perturbation exceeds expectations, the platform’s pricing is higher when both the platform and the e-retailer are informed than when only the platform possesses this information. However, the demand for the platform channel is the opposite. This is because e-tailers who can obtain accurate market information are more capable of attracting consumers through their own channels, thereby reducing the demand for the platform channel.

Proposition 3.

Under the agency selling mode, the optimal retail prices and demands of the e-tailer and platform in Case NN, Case IN, and Case IS satisfy the following relationships:

- (i)

- If or , . If , .

- (ii)

- If or , . If , .

- (iii)

- When , if or , and if , .When , if or , and if , .

- (iv)

- If or , . If , .Here, , , , .

See Appendix B for a proof of Proposition 3. This proposition presents a comparative analysis of pricing and demand under different cases in the agency selling mode, which are primarily influenced by the actual market perturbation , the agency fee rate , the degree of increasing product extra value through live streaming , and the fixed unit fee paid by the e-tailer to the platform upon accepting the information sharing contract. Evidently, pricing and demand in the agency selling mode are subject to a broader set of influencing factors compared to the reselling mode, thereby offering e-tailers greater flexibility in making information sharing decisions. According to Proposition 3, when the e-tailer does not accept information sharing, the platform’s investment decision has no impact on the pricing or demand for either the e-tailer or the platform. This is because in both cases, the e-tailer remains unaware of the true market demand, and under the agency selling mode, only the e-tailer’s decisions are involved. Proposition 3(i)–(ii) reveals that when the disclosed market potential exceeds a threshold (i.e., and ), the actual prices are larger than the e-tailer expected, and vice versa. From Proposition 3(iii)–(iv), we observe that the e-tailer’s acceptance of information sharing typically leads to a rise in demand for the streamer channel and a corresponding decline in demand for the platform channel. However, according to Proposition 3(iii), when the agency fee rate is below a defined threshold (i.e., ) and the disclosed market potential exceeds a threshold (i.e., ), or when the agency fee rate exceeds the threshold (i.e., ) and the disclosed market potential is below the threshold (i.e., ), the demand for the platform channel can grow under information sharing.

5. E-Tailer Accepting Sharing vs. No Accepting in S3

5.1. Reselling Mode

By comparing the optimal expected profits of the e-tailer in Cases IN and IS under the reselling mode, the e-tailer’s optimal decision is given, as shown in Proposition 4.

Proposition 4.

Under the reselling mode, the e-tailer accepts the information sharing contract (i.e., ) if or and she does not accept the information sharing contract (i.e., ) if or , where .

See the Appendix B for a proof of Proposition 4.This proposition suggests that the unit fixed cost associated with the e-tailer accepting the information sharing contract has no effect on the e-tailer’s decision to accept the contract under the reselling mode. This conclusion deviates from intuition because it is generally believed that the cost of information sharing is closely related to the e-tailer’s willingness to accept. The reason for this phenomenon can be explained by Proposition 2, that is, in the reselling mode, whether the e-tailer chooses to share information or not, its demand and pricing are not affected by the cost of information sharing. Moreover, under the reselling mode, the e-tailer only needs to take into account the streamer channel parameters () and the demand perturbations () when making the sharing decision. Specifically, since , the left endpoint value is above a threshold (i.e., ) when the extra value of product by live streaming is high and then the e-tailer always accepts the information sharing contract. Since , the right endpoint value is below a threshold (i.e., ) when the hassle cost and unit commission paid by the e-tailer to the streamer are sufficiently large and then the e-tailer always refrains from accepting the information sharing contract. In particular, when , the e-tailer accepts the information sharing only if the disclosed market potential is larger than a threshold (i.e., ); otherwise, she rejects it.

5.2. Agency Selling Mode

By comparing the optimal expected profits of the e-tailer between Cases IN and IS under the agency selling mode, the e-tailer’s optimal decision is obtained, as shown in Proposition 5.

Proposition 5.

Under the agency selling mode, the e-tailer’s optimal strategy is given as follows:

- (i)

- The e-tailer accepts the information sharing contract (i.e., ) if , where

- (ii)

- When and , if , then the e-tailer accepts the information sharing contract, and if and

- (a)

- or , the e-tailer accepts the information sharing contract (i.e., );

- (b)

- and , the e-tailer rejects the information sharing contract (i.e., );

- (c)

- , the e-tailer rejects the information sharing contract if and accepts if ;

- (d)

- , the e-tailer rejects the information sharing contract if and accepts if ;

- (e)

- and , the e-tailer rejects the information sharing contract if and accepts if .

Here, and (, , and ). - (iii)

- When , if , then the e-tailer’s decision is the same as (a)–(e) in (ii).

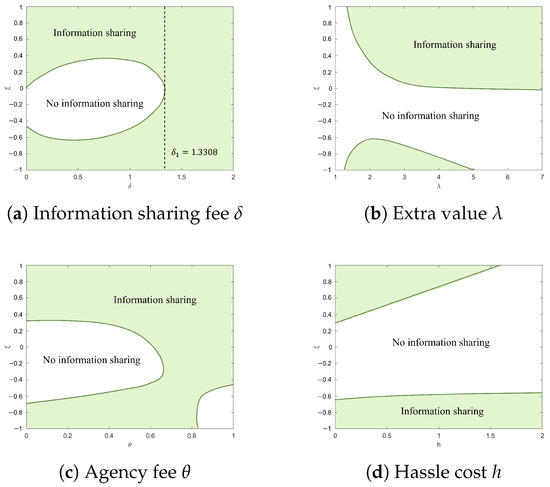

See Appendix B for a proof of Proposition 5. This proposition indicates that under the agency selling mode, the e-tailer’s decision to accept the information sharing contract is influenced by multiple factors, including the unit fixed fee of accepting information sharing , the agency fee , the streamer channel parameters (), and the demand perturbations (). From Proposition 5(i), we conclude that if the unit fixed fee of accepting the information sharing contract is lager than a threshold, i.e., , the e-tailer always accepts the information sharing. This result appears counterintuitive, as it is generally believed that a high unit cost of information sharing may erode the e-tailer’s profit margin and thus reduce her willingness to adopt the contract. To explain this phenomenon, we further examine the underlying mechanism. Recall Proposition 3(iii)–(iv), that when is sufficiently large, the e-tailer’s acceptance of information sharing reduces demand in the platform channel and increases demand in the streamer channel. Since the streamer channel does not incur agency fees, it offers a high marginal profit. As a result, this shift in demand may actually enhance the e-tailer’s overall profitability and thereby strengthen her incentive to accept the information sharing contract. From Proposition 5(ii)–(iii), when , the e-tailer’s acceptance of information sharing is affected by multiple parameters, resulting in a complex decision problem. Specifically, the e-tailer accepts the information sharing contract if a threshold is below the left endpoint value (i.e., ) or a threshold is above the right endpoint value (i.e., ).

To make Proposition 5 more intuitive, we conduct numerical experiments to evaluate the impact of various parameters on the e-tailer’s decision to accept information sharing. The results are presented in Figure 4. The basic parameter settings are , , , , , , (these values are used throughout this paper unless otherwise stated). In particular, by observation, we find that the parameters r and h exhibit similar effects on the results. Therefore, we focus our analysis on the impact of h, with the understanding that the effect of r follows the same pattern.

Figure 4.

E-tailer’s optimal information sharing strategy under agency selling.

To better interpret Figure 4, we define a gap as , which captures the difference between the realized perturbation and its expected value. As shown in Figure 4, when the gap is relatively large, the e-tailer is more likely to accept information sharing contract; conversely, when the gap is small, the incentive diminishes. This observation is consistent with case (5) in Proposition 5(ii)–(iii). Indeed, a large gap indicates that the e-tailer either severely overestimates or underestimates market demand, both of which can lead to significant losses. Figure 4a shows that if , then the e-tailer always accepts the information sharing, which is consistent with Proposition 5(i). From Figure 4b, it can be seen that when is quite small, i.e., the extra value of the product by live streaming is very low, the e-tailer should not accept the information sharing contract; when is sufficiently large, information sharing becomes beneficial to the e-tailer only if the realized disturbance exceeds the expected one, i.e., when the e-tailer underestimates the market. Figure 4c illustrates that information sharing is more advantageous to the e-tailer only when the gap is relatively large. Figure 4d shows that when h is sufficiently large, i.e, the hassle cost incurred by a consumer participating in live streaming programs is high, the e-tailer does not accept information sharing even if the market is seriously underestimated.

5.3. Impact of Accepting Sharing on the Platform

Since the e-tailer decides whether to accept the information sharing contract proposed by the platform, the platform is bound to consider the impact of the e-tailer’s behavior on its own profitability when designing the contract. Therefore, it is both meaningful and necessary to explore the impact of the e-tailer’s acceptance of information sharing contract on the platform. First, under the reselling mode, the impact of the e-tailer’s acceptance of the information sharing contract on the platform is analyzed by comparing the optimal expected profits of the platform in Cases IN and IS, as shown in Proposition 6.

Proposition 6.

Under the reselling mode, the platform is worse off with the e-tailer accepting the information sharing contract (i.e., ) if or and is better off with the e-tailer accepting the information sharing contract (i.e., ) if , where .

See the Appendix B for a proof of Proposition 6. Similarly to Proposition 4, Proposition 6 indicates that the unit fixed cost of acceptance the information sharing contract by the e-tailer has no effect on the platform’s profits under the reselling mode. This conclusion is also counterintuitive, as it is generally believed that the information sharing fees charged by platforms should be closely related to their profits. This is because under the reselling mode, regardless of whether sharing information occurs, the demand and pricing of the platform channel are not be affected by the information sharing fee. Proposition 6 shows that if the right endpoint value is below a threshold (i.e., ), then the platform is always worse off with information sharing. Since , the higher extra value of the product by live streaming, it follows from Proposition 4 that the e-tailer is more likely to accept the information sharing, although doing so may reduce the platform’s profit. Since , the higher hassle cost and unit commission of the streamer, it follows from Proposition 4 that the e-tailer is less likely to accept the information sharing contract, but if she does, the platform’s profit may be higher. Therefore, there is a contradiction between the benefit of the platform and the acceptance of information sharing by the e-tailer. This highlights the importance of investigating whether the e-tailer’s acceptance of the information sharing can simultaneously enhance the profits of both the platform and the e-tailer. Proposition 6 shows that the platform is better off with information sharing only if . Based on Proposition 4, if , or , , then both the platform and the e-tailer benefit from the e-tailer to accept information sharing under the reselling mode.

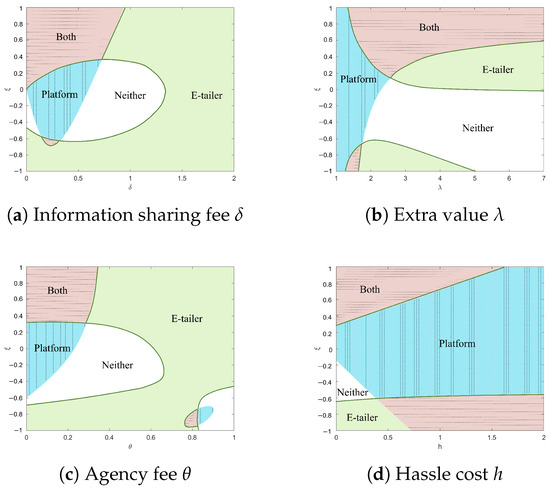

To determine the consequences of the e-tailer’s information sharing acceptance for the platform under the agency selling mode, a comparison is drawn between the platform’s optimal expected profits in Cases IN and IS. Since the profit function of the platform is complex and no effective theoretical results can be obtained, we employ a numerical experiment to illustrate this problem, and the results are shown in Figure 5. Specifically, Region “Both” is a Pareto improvement area, where the e-tailer’s acceptance of the information sharing leads to increased profits for both the platform and the e-tailer. Region “E-tailer” represents that only the e-tailer benefits from accepting sharing, while Region “Platform” represents that only the platform gains. Region “Neither” represents that neither the platform nor the e-tailer benefits from the e-tailer accepting sharing.

Figure 5.

Impact of the e-tailer accepting sharing under agency selling.

Figure 5a indicates that only if the cost of the e-tailer accepting sharing is relatively low is the platform better off with the e-tailer accepting sharing. Notably, Proposition 5(i) shows that the e-tailer is consistently motivated to accept sharing when exceeds a threshold (i.e., ). However, to maximize their own profit, the platform should set at a low level when designing the information sharing contract.

Figure 5b shows that if the extra value created by live streaming is limited, then the platform benefits from the e-tailer accepting sharing, while the e-tailer herself does not gain from it. Figure 5c reveals that the platform’s profitability is enhanced by setting a low agency fee rate when the e-tailer accepts information sharing. This incentivizes the platform to adopt a low agency fee rate to promote information sharing. Figure 5d shows that when the hassle cost and unit commission are high, the platform benefits from the e-tailer accepting sharing. Given the focus on achieving a “win-win” outcome in which both the platform and e-tailer benefit, an analysis of Figure 5 provides the following managerial insights for the “win-win” situation: (i) The actual perturbation is larger than the expected perturbation, namely, the market is underestimated. (ii) The cost of the e-tailer to accept sharing is at a moderate level (to be consistent with the following text, it is called the moderate level). (iii) The extra value generated by live streaming is relatively high. (iv) The agency fee rate set by the platform is at a low level. (v) The hassle cost and unit commission are at a low level when the market is underestimated, while the hassle cost and unit commission are at a high level when the market is overestimated.

6. Platform Investing vs. No Investing in S2

6.1. Reselling Mode

By comparing the optimal expected profits of the platform in Cases NN and IN or Cases NN and IS under the reselling mode, the platform’s optimal investing decision is obtained, as shown in Proposition 7.

Proposition 7.

Under the reselling mode, when the e-tailer does not accept sharing, the platform invests if and never invests if ; conversely, when the e-tailer accepts sharing, the platform invests if and never invests if . Here, and .

See Appendix B for a proof of Proposition 7. This proposition indicates that even if the e-tailer rejects information sharing, the platform can still improve their profit by investing in new technology provided that the investment cost is below a threshold, i.e., . This is because under the reselling mode, the platform can obtain accurate demand information for their own channel through investment, thereby enabling more effective decision-making. In contrast, when the e-tailer rejects information sharing, the actual demand in the streamer channel remains unknown to the e-tailer, which may provide the platform with a relative advantage in formulating strategy. Moreover, since and , a larger demand perturbation threshold and a higher extra value generated through live streaming both expand the feasible cost for the platform to invest in IT. From Proposition 7, we conclude that when the e-tailer accepts the information sharing contract and the investment cost is lower than a threshold, i.e., , the platform’s profit with investment will exceed that without investment. Note that is the actual value of a demand perturbation that we do not know before investing. However, we can find that when the market is underestimated (i.e., ), there is always , and as the degree of undervaluation of the market increases, the platform’s acceptable IT investment cost is high. Therefore, when making investment decisions, the platform needs to evaluate the current market environment in advance. Although we cannot obtain accurate market perturbation information before investing, it is relatively easy to analyze the overall market trend by some methods, such as Porter’s Five Forces analysis, consumer surveys, industry reports, and market research. As a result, when the market is underestimated, the platform tends to adopt new IT. In addition, if the investment cost exceeds a critical level, i.e., , then the platform should refrain from investing in IT regardless of whether the e-tailer accepts the information sharing contract.

6.2. Agency Selling Mode

Considering the optimal expected profits of the platform in Cases NN and IN under the agency selling mode, the platform’s optimal investing strategy is obtained, as shown in Proposition 8.

Proposition 8.

Under the agency selling mode, the platform’s optimal strategy is always not to invest in new technology when the e-tailer does not accept the information sharing contract.

Proposition 8 shows that under the agency selling mode, when the e-tailer rejects the information sharing contract, it is never optimal for the platform to incur the cost of new technology. The fundamental reason is that in this case, the e-tailer’s decision-making remains unaffected by the platform’s investment, and thus the revenues of both the platform and the e-tailer remain unchanged. However, the platform incurs the investment cost, leading to a reduction in their profit. Therefore, under the agency mode, if the platform intends to improve their profitability through IT investment, he must design an information sharing contract that the e-tailer is willing to accept to realize a positive return on investment.

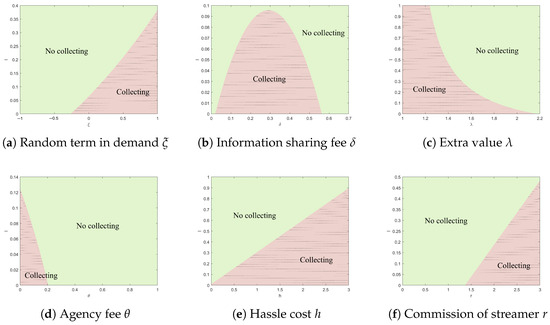

Naturally, the following questions emerge: Under the agency selling mode, how should the platform design the information sharing contract to ensure the e-tailer’s willingness to accept it? Furthermore, if the e-tailer accepts information sharing, can the platform’s investment in IT lead to high return? To respond to these questions, a numerical experiment is performed to compare the optimal expected profits of the platform and the e-tailer in Cases NN and IS under the agency selling mode. The results are illustrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Impact of the platform collecting information under agency selling.

Figure 6 reveals that under the agency selling mode, if the e-tailer accepts the information sharing contract, the platform can potentially benefit from investing in IT when the market demand is underestimated, the cost of the e-tailer accepting sharing is low, the extra value generated by live streaming is limited, the agency fee rate set by the platform is at a low level, and the hassle cost and unit commission are not at a low level. Specifically, as illustrated in Figure 6b, setting the information sharing fee either excessively high or overly low narrows the feasible investment cost threshold for the platform, thereby weakening their incentive to invest in IT. Therefore, the sharing fee should be set at a moderate level to maximize investment returns. Figure 6c shows that when the extra value is low, the platform should invest in IT. However, as the extra value increases, the platform’s incentive to invest in IT gradually diminishes. Moreover, Figure 6a,d–f indicate that the platform’s acceptable investment cost exhibits a linear relationship with other parameters: it is positively correlated with the actual perturbation, the hassle cost, and the unit commission while negatively correlated with the agency fee rate.

To explore the optimal strategy, we combine the analysis of Section 5 and Section 6 and draw the following management inspiration:

- Under the reselling mode, when the investment cost satisfies , the platform has an incentive to invest in IT. Furthermore, if and , or and , the e-tailer’s acceptance of the information sharing leads to mutual benefits for both the platform and the e-tailer, resulting in a strict Pareto improvement. Moreover, when the investment cost satisfies , the platform still has an incentive to invest in IT. In this case, if or , the e-tailer does not accept sharing. Although the e-tailer’s profit remains unchanged, the platform can still improve their own profit through investment, which also constitutes a weak Pareto improvement.

- Under the agency selling mode, when the market environment is relatively stable, the e-tailer tends to reject information sharing contract. In this case, platform investment in IT leads to a decline in their own profit and the e-tailer’s profit remains unchanged, thus failing to achieve a Pareto improvement. In contrast, if the market demand is significantly underestimated, the cost for the e-tailer to accept information sharing is low, the extra value is at a moderate level, the agency fee rate is low, and the hassle cost and unit commission are at a low level, the platform is more likely to invest in IT. Under these conditions, the e-tailer is also more likely to accept the information sharing contract, thereby enabling a strict Pareto improvement for both parties.

7. Reselling vs. Agency Selling in S1

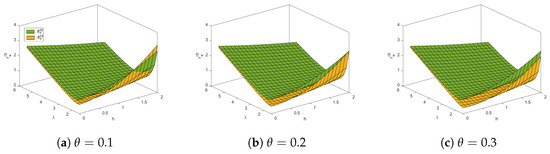

Based on the analysis in Section 5 and Section 6, we find that a strict Pareto improvement (i.e., both the platform and the e-tailer realize higher profits) can be achieved under some conditions when the platform collects information and the e-tailer accepts the information sharing contract. Given the complexity of deriving an analytical solution, a numerical analysis is performed to investigate the impact of reselling and agency selling on the equilibrium profits of both the e-tailer and the platform under these conditions.

Figure 7 presents a comparison of the e-tailer’s equilibrium profits under reselling and agency selling. From Figure 7, we can find that when the agency fee is high, the e-tailer consistently prefers the reselling mode. Conversely, when the agency fee is low, the e-tailer chooses the agency selling mode only when the extra value of live streaming is low and the the hassle cost is large; otherwise, the reselling mode remains the preferred choice.

Figure 7.

Equilibrium profits under reselling and agency selling for the e-tailer.

Next, we analyze the impact of the e-tailer’s mode choice on the platform’s profit, with the results illustrated in Figure 8. As shown, the agency mode is more beneficial to the platform if the agency fee is relatively low. However, under a higher agency fee, the reselling mode becomes more advantageous for the platform if live streaming brings high extra value and incurs low hassle costs; otherwise, the agency mode remains the preferable option.

Figure 8.

Equilibrium profits under reselling and agency selling for the platform.

In summary, by combining the analysis of the e-tailer’s mode selection and its impact on the platform’s profit, we find that the selected sales mode often fails to maximize the platform’s profit. Nevertheless, there are two scenarios in which the e-tailer’s decision coincides with the platform’s optimal outcome: (i) When the agency fee is low, if live streaming brings low extra value and incurs high hassle costs, then the e-tailer prefers the agency mode, which is also optimal for the platform. (ii) When the agency fee is high, if live streaming brings high extra value and incurs low hassle costs, then the e-tailer tends to choose the reselling mode, which is also optimal for the platform.

8. Discussion

The previous sections analyze the optimal strategies, including pricing, IT investment, information sharing contract design, information sharing, etc. In this section, we discuss the supply chain coordination and the live streaming sales channels under the scenario of IT investment and information sharing, since this scenario may achieve a strict Pareto improvement.

8.1. Supply Chain Coordination

First of all, we analyze the impact of some key parameters on the profits of individual members and overall supply chain, and whether supply chain coordination can be achieved. Specifically, the basic parameters are set as , , , , and the remaining parameters follow the settings used in the previous analysis. The profit of the streamer is and the total profit of the supply chain is .

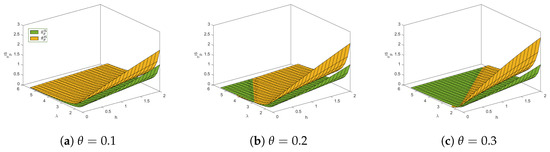

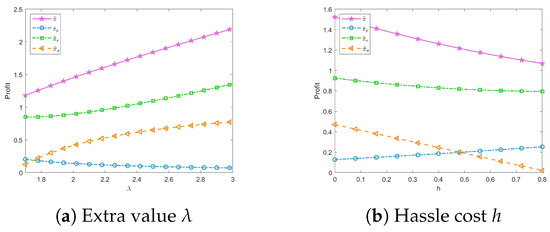

Under the reselling mode, it is observed that the information sharing cost has no impact on the profits of either the platform or the e-tailer. Therefore, this factor is not necessary to analyze. Instead, we focus on the parameters related to live streaming sales, with the results presented in Figure 9. As shown in Figure 9a, as the extra value brought by live streaming sales increases, the profits of the e-tailer, the streamer, and the overall supply chain increase, while the platform’s profit decreases. This suggests that the enhanced effectiveness of live streaming improves overall performance of the supply chain but also intensifies the profit-sharing pressure on the platform, leading to a decline in their profit. Figure 9b shows that as the hassle cost for consumers to participate in live streaming increases, the profits of the e-tailer, the streamer, and the overall supply chain decrease, whereas the platform’s profit increases slightly. This indicates that high consumer participation barriers reduce the effectiveness of live streaming sales, thereby lowering total supply chain profits. However, it also alleviates the competitive pressure on the platform, resulting in a modest profit increase.

Figure 9.

Impact of parameters on the profits of supply chain members under reselling.

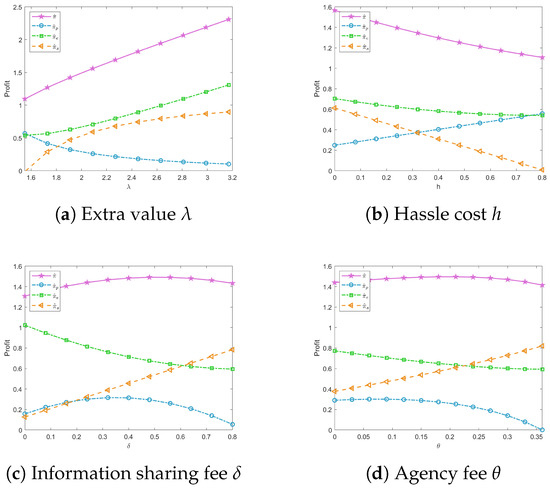

Under the agency selling mode, we analyze the impact of four key parameters, namely, the extra value of live streaming, the hassle cost of consumer participation, the information sharing cost, and the agency fee, on member profits throughout the supply chain. The corresponding results are shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Impact of parameters on the profits of supply chain members under agency selling.

Figure 10a demonstrates that the profits of the e-tailer, the streamer, and the overall supply chain increase with the extra value generated by live streaming sales, while the platform’s profit decreases. This indicates that as the marginal benefit of live streaming improves, the e-tailer and the streamer can capture a larger share of the value, whereas the platform’s profit is squeezed under the profit-sharing mechanism. Figure 10b shows that as the hassle cost for consumers to engage in live streaming increases, the profits of the e-tailer, the streamer, and the entire supply chain decrease, whereas the platform’s profit slightly increases. This outcome may stem from the fact that rising participation barriers diminish the effectiveness of the live streaming channel and suppress overall demand. Nonetheless, as an intermediary, the platform is relatively less affected and may even benefit marginally from improved bargaining power. Figure 10c reveals that increasing the information sharing cost does not necessarily benefit the platform. Instead, the profits of both the platform and the entire supply chain reach their maximum when the cost is set at a moderate level. Therefore, it is crucial for the platform to determine a balanced level of information sharing cost. This finding aligns with the earlier analysis in Figure 6b. Figure 10d illustrates that a high agency fee leads to a decline in the platform’s profit, which seems counterintuitive. It may be attributed to the fact that a high agency fee incentivizes the e-tailer to raise the retail price in the platform channel, thereby reducing consumer demand and ultimately diminishing the platform’s revenue. Thus, the agency fee should be set at a reasonable level to avoid a negative cycle of “high agency fee–reduced demand–lower profit”. In practice, commission rates on e-commerce platforms rarely exceed 30%, which is consistent with this analytical result.

8.2. Introducing Live Streaming Sales Channel

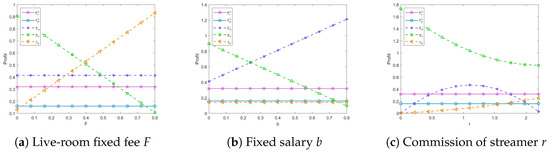

In this subsection, we analyze the impact of introducing live streaming sales channel on the supply chain members and investigate the mechanism for setting the parameters related to the channel.

If the live streaming sales channel is not introduced, the demand function is . Under reselling mode, when IT investment and information sharing are implemented, the profits for the e-tailer and the platform are and , respectively. By backward induction, we can obtain the equilibrium profits for the platform and the e-tailer to be

A comparison of the profits before under the reselling mode and the above ones is shown in Figure 11. It is evident from Figure 11a that when the fixed fee of the e-tailer paying to open live streaming rooms increases, her willingness to adopt the streamer channel decreases significantly. Moreover, unless the fixed fee is very low, the platform usually benefits from introducing a live streaming sales channel. This phenomenon can explain why many e-tailers in the real-world like to operate both platform and streamer channels on the same platform. Therefore, the platform should set a moderate fixed fee for opening a live streaming room, which not only can effectively promote the introduction of a live streaming sales channel but also can ensure a substantial increase in their revenue. From Figure 11b, we can observe that the e-tailer should set a relatively low base salary for the streamer, as otherwise the streamer’s earnings may exceed those of the e-tailer. From Figure 11c, it is evident that both excessively high and excessively low unit commissions for the streamer fail to effectively incentivize the streamer. Therefore, the e-tailer should set the streamer’s unit commission at a moderate level to ensure the effectiveness of the incentive mechanism.

Figure 11.

Comparison before and after the introduction of live streaming selling under reselling.

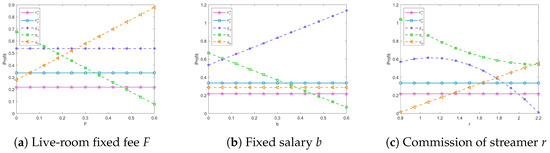

Under the agency selling mode, when IT investment and information sharing are implemented, the profits for the e-tailer and the platform are and , respectively. By maximizing the e-tailer’s profit, we can obtain the equilibrium profits for the platform and the e-tailer to be

A comparison of the profits before under the agency selling mode and the above ones is shown in Figure 12. As shown in Figure 12a, the platform should set a moderate fixed fee for opening a live streaming room. This will not only encourage the e-tailer to use the platform to open a store live streaming room but also significantly increase the platform’s revenue. Figure 12b shows that the e-tailer should set a relatively low base salary for the streamer, as otherwise the streamer’s earnings may exceed the e-tailer. Figure 12c shows that as the streamer’s unit commission varies, the e-tailer’s revenue consistently exceeds the streamer’s. In addition, the streamer’s revenue does not continuously increase with the rise in unit commission, suggesting that the e-tailer should set the commission at a moderate level to effectively motivate the streamer while safeguarding their own revenue.

Figure 12.

Comparison before and after the introduction of live streaming selling under agency selling.

9. Conclusions

This paper investigates the operational decisions within a dual-channel LSC supply chain under stochastic demand perturbations. The decisions considered include pricing, mode selection, IT investment, information sharing contract design, and information sharing selection. We discuss the demand functions for both the platform and streamer channels, incorporating the distinctive characteristics of live streaming sales. Subsequently, under both reselling and agency selling modes, we establish optimization models and derive the corresponding equilibrium solutions. Then, we analyze the platform’s optimal IT investment strategy and the e-tailer’s information sharing decision. Comparative analysis of the equilibrium profits under two sales modes is conducted to explore the strategic preferences of supply chain members.

9.1. Summary of Main Findings

To illustrate the validity and robustness of the model, we perform a sensitivity analysis of key parameters to examine their impact on member profits, from which some managerial insights are drawn. Furthermore, through the systematic investigation and sensitivity analysis of key parameters (such as live streaming extra value and hassle cost h), we clearly reveal the continuous boundaries between different equilibrium regions. This finding not only strongly demonstrates the high robustness and stability of our model under parameter fluctuations but also confirms its validity. This robust characteristic ensures that the managerial insights we derive (e.g., regarding incentive conditions for investment and mechanism choice for information sharing) do not rely on extreme parameter settings but maintain their consistency and guiding value across a broad and realistic range of LSC operational environments.

Firstly, in the selling mode, the e-tailer is more inclined to accept information sharing contracts when the extra value generated by live streaming sales is high or when market demand is underestimated. Conversely, when the streamer’s commission and the hassle cost incurred by consumers participating in live streaming are high or when market demand is overestimated, the e-tailer is more likely to reject such contract. Moreover, information sharing costs primarily influence wholesale prices but have no impact on pricing, IT investment, and information sharing. In the agency selling mode, the e-tailer tends to reject the information sharing contract under relatively stable market conditions. Only when the market is significantly underestimated, the information sharing cost is moderate, and the agency rate and hassle cost are low is the e-tailer more likely to accept such contracts.

Secondly, with regard to the platform’s IT investment strategy, under the reselling case, when the e-tailer refuses to accept information sharing, the platform still has an incentive to invest in IT if the demand perturbation threshold is large or the extra value generated by live streaming is high. Furthermore, when the e-tailer accepts the information sharing contract, the platform also has an incentive to invest if the market is underestimated. In the agency selling case, if the e-tailer rejects information sharing, the platform should never invest in IT, as their own profit would be adversely affected. However, if the e-tailer is willing to accept information sharing, the platform becomes motivated to invest when the market is severely underestimated, the information sharing fee is moderate, and the agency fee and the hassle cost are low.

Thirdly, in terms of sales mode selection, the e-tailer tends to choose the reselling mode when the agency fee is high. When the agency fee is low, the e-tailer is more likely to choose the agency mode if the extra value generated by live streaming is limited and the hassle cost is high; otherwise, she still prefers the reselling mode. However, the e-tailer’s optimal choice does not always coincide with the platform’s optimal outcome. A win-win result between the platform and the e-tailer can only be achieved under the following two conditions: (i) When the agency fee is low, the extra value is low, and the hassle cost is high, the agency mode is optimal for both parties. (ii) When the agency fee is high, the extra value is high, and the hassle cost is low, the reselling mode is the jointly optimal choice. Moreover, regardless of the reselling or agency selling mode, when the platform invests in IT and the e-tailer accepts information sharing, supply chain coordination can be realized if the extra value created by live streaming is high. In addition, the platform should set a moderate fixed fee for opening live streaming rooms to attract e-tailers and boost their revenue, while the e-tailer should set a low base salary and a moderate unit commission for streamers to ensure their own revenue and effectively motivate streamers.

9.2. Managerial Insights and Practical Implications