Abstract

This study investigates the impact of social media marketing activities on customers’ behavioral engagement with fashion clothing brands in Pakistan. Drawing on the Stimulus–Organism–Response (S–O–R) framework, this study examined how social media marketing activities affect brand love and subsequent consumers’ behavioral engagement, and to what extent gender moderates the association between social media marketing activities and brand love. Data were collected through a cross-sectional survey using convenience sampling, resulting in 297 valid responses. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling using SmartPLS 4 software was employed for the data analysis. The findings revealed that social media marketing activities have a substantial impact on brand love, and brand love, in turn, influences customers’ behavioral engagement. Specifically, social media marketing dimensions, such as entertainment, trendiness, customization, and word of mouth, emerged as statistically significant drivers of brand love, whereas interaction did not exhibit any effects. Furthermore, brand love also serves as a predictor of behavioral engagement. Regarding the moderating role of gender, the results confirm that the effect of customization on brand love is higher for females than for males. Similarly, gender acts as a moderator, indicating that the effect of word of mouth on brand love is stronger for males than for females. This study contributes to the literature by emphasizing the significance of brand love in formulating strategies to enhance consumer engagement in the digital landscape.

1. Introduction

Digital advancements have reshaped the marketing landscape. Notably, the emergence of social media has revamped the way firms disseminate product- and service-related information to their customers. Social media marketing platforms, such as Facebook and Instagram, have been acknowledged by marketing managers as the preferred media of communication in shaping customers’ perceptions and behavioral outcomes [1]. Unlike traditional media, social media is projected to have 4.41 billion users in 2025 [2], which enables brands to create engaging content, facilitate two-way communication [3], strengthen customer relationships, and contribute to profitability through high sales [4]. Rampant advancement in smartphones has further accelerated the adoption of social media marketing activities (SMMAs) to reach prospective and existing customers, making it an essential component of firms’ modern marketing strategies.

Most importantly, post-COVID-19 Pakistani consumers have experienced a significant transformation in their shopping habits, which contributed to online selling, as individuals were isolated and had no other choice but to shop. Owing to this pivotal change, fashion clothing brands in Pakistan witnessed high growth and contributed to intense rivalry between the brands [5]. Leading clothing brands, such as Asim Jofa, Sana Safinaz, J., Maria B., and Khaadi, secured high market shares, yet they compete with each other to acquire more customers [6]. Fashion brands in Pakistan have started to leverage social media marketing activities to reshape customer–brand relationships through emotional connections [7]. To ensure their online presence, Pakistani clothing brands developed their online pages and engaged with local customers to build strong relationships.

Customer engagement has been widely examined as a psychological phenomenon that leads to a particular attitude and behavior. For example, Salem and Alanadoly [8] posited that customer experience contributes to psychological engagement, which subsequently shapes customer citizenship behavior. Similarly, cognitive engagement has been confirmed as an antecedent of brand love [9]. However, the notion of customer engagement behaviors (referred to as CEBs) has gained paramount importance, as behaviorally engaged customers not only buy themselves but also serve as brand ambassadors, contribute to product development and brand performance through co-creation, and enhance organizations’ sales through referrals and social influence [10,11,12,13,14]. The present study focused on CEBs as conceptualized by Kumar et al. [15], which remained unexplored in the context of luxury fashion brands in Pakistan.

Brand love refers to the degree of passionate emotional attachment a satisfied consumer has toward a particular brand [16]. Brand love has been consistently evidenced as a strong predictor of consumer behavior. In a store brand context, Ahmed [17] confirmed that SMMAs influence brand love and subsequently influence customer loyalty. However, the findings were limited to purchase frequency, neglecting broader consumer behavioral aspects such as social influence, knowledge sharing, referrals, and repurchasing. Similarly, Hafez [18] demonstrated that brand SMMAs contribute to brand equity through customer trust and brand love. The authors focused on brand equity, which may exaggerate the market performance, as brand equity was conceptualized by covering the cognitive and affective aspects and disregarding the behavioral outcome. Furthermore, the findings also have a generalizability issue, as the study was conducted in the Bangladesh banking sector. Similarly, brand love operates as a psychological mechanism through which brand personality traits influence customers’ word of mouth behaviors [19]; however, the findings of this study were limited to online banking with a focus on online WOM. Despite the critical contributions of these studies, the scope is limited to the effect of brand love on customer loyalty, online WOM, and brand equity. Furthermore, some studies confirmed that self-brand congruency [20], perceived value, customer experience [21], customer relationship quality [22], social identification, and customer satisfaction [23] are important antecedents of CEBs. All these antecedents show how researchers have focused on the cognitive aspects while ignoring the affective components of consumer evaluation in earlier literature. Therefore, the effect of brand love as a predictor of CEBs in the Pakistani luxury fashion brand context is still less explored [24,25]. To address this significant gap, this study proposed that brand love is a vital antecedent of CEBs.

Furthermore, past studies have overlooked the moderating role of gender in explaining the influence of SM dimensions on brand love using the schema theory [17]. According to gender schema theory, males and females react incongruently to external environmental stimuli or signals [26]. Therefore, the effect of SMMAs on brand love may vary according to gender differences.

Based on these knowledge gaps, this study aims to investigate how SMMAs influence brand love and subsequent behavioral engagement dimensions and to what extent gender moderates the relationship between SMMAs (e.g., entertainment, trendiness, customization, WOM, and interaction) and brand love.

This study provides valuable contributions. First, contrary to past studies, which have reported SMMAs as a higher-order construct, the present study proposed the dimensional level effect of SMMAs (entertainment, trendiness, customization, and word of mouth) on brand love and identified the varied effect of each dimension on brand love. Second, this study confirmed brand love as a vital predictor of CBE dimensions (social influence, referrals, purchase intentions, and knowledge sharing). Contrary to past studies, which focused on cognitive and attitudinal aspects, the findings contributed to Stimulus–Organism–Response (S–O–R) theory and supported that affective path strengthens customer–brand relationships in which customers contribute to the brand’s long-term development and growth through engagement behaviors. The further moderating role of gender between the relationship of SMMAs and brand love is also an important contribution of this study.

Finally, this study offers new perspectives on the importance of SMMAs within the Pakistani fashion clothing sector. The fashion brands industry in Pakistan has shown exponential growth, and all famous brands, such as Khadi, Asim Jofa, and Sana Safinaz, have leveraged online platforms to build customer relationships. Hence, the focus of the present study on SMMAs, brand love, and CBE is timely and valuable for both scholars and practitioners.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theoretical Framework

Mehrabian and Russell [27] coined the S–O–R theory, which states that emotions (O) triggered by stimuli (S) foster specific behaviors (R). Thus, based on the S–O–R framework, stimuli from the environment create “inner organism changes,” resulting in response behavior. Based on the psychological environment, a stimulus (S) brings out a change in an individual (O), which leads to a particular behavior (R).

Building on this theoretical foundation, recent studies have increasingly applied the S–O–R framework to explain consumer responses in digital and social media contexts. For instance, Ibrahim et al. [28] and Yadav and Rahman [29] posited that SMMAs affect specific customers’ internal psychological states, such as brand trust and brand equity, which, in turn, influence customer loyalty in the e-commerce context.

In the services domain, in a restaurant context, Ibrahim and Aljarah [30] confirmed that SMMAs collectively influence consumers’ self-brand connection through engagement, and the effects vary with respect to the gender difference and levels of trust. Extending these insights to the airline industry, Khan et al. [31] evidenced that SMMAs not only contribute to brand loyalty but also foster electronic word of mouth behaviors.

Multiple studies have emphasized the importance of emotions or affective aspects as a psychological mechanism to explain the effect of SMMAs on consumer behavior [32]. Safeer [33] applied the S–O–R framework in fashion retail and identified that SMMAs stimulate impulse buying through the mediating effect of an emotional response. However, these studies primarily tested the aggregate effect of SMMAs instead of disentangling the unique contribution of individual dimensions. Furthermore, emotions have also been reported as a function of the association between online content attributes and customer engagement [34]. Similarly, social networks’ emotional marketing predicts consumers’ purchase behaviors [35].

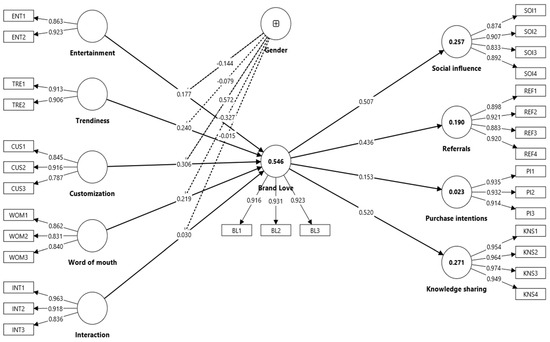

Taken together, these studies highlight that there is a scarcity of studies that identify how individual dimensions of SMMAs in fashion retail brands foster customers’ internal evaluation and CBE through the application of the S–O–R framework. To bridge this gap, the conceptual framework of this research is illustrated in Figure 1. This present study conceptualized SMMAs as representing the external environmental stimuli (S) encountered by customers via SNSs that generate brand love (O), which, in turn, drives CBE (R).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

2.2. Entertainment and Brand Love

Online programs, tools, systems, or platforms that enable content sharing and collaboration between community members are termed social media [36]. The present study followed the conceptualization of Kim and Ko [3] and Yadav and Rahman [37] and defined SMMAs as a multifaceted construct that includes trendiness, word of mouth, entertainment, customization, and interaction.

Entertainment refers to enjoyment derived from social media content interaction [38]. The entertainment factor in social media functions as a decisive element in consumer psychology because it develops enthusiastic brand responses from social media audience members. Marketers utilize social media platforms to provide entertainment, which satisfies consumers’ desire for pleasure by posting visual content and product details [39,40]. Social media features, including games, video sharing, and quizzes, enable increased user participation in brand communities [41]. Brand awareness, together with brand image, receives improvement from entertainment, which creates strong consumer–brand connections. Under social media conditions, entertainment refers to the capability of a platform to present engaging, amusing, and remarkable content for its audience [42]. Previous work reveals the importance of entertainment in enhancing consumer–brand relationships, brand familiarity and image, brand knowledge, and brand equity [3,43,44,45]. Furthermore, Ibrahim et al. [46] and Bazi et al. [47] found that entertaining content results in brand-related emotions, such as brand love and commitment. It has emerged as a strong predictor of customer behavior [48]. Therefore, based on this discussion, as well as other supporting arguments, it became reasonable to propose the following hypothesis:

H1:

Entertainment positively influences brand love.

2.3. Trendiness and Brand Love

Trendiness refers to the degree to which an advertisement conveys the latest and most popular information about a product or service [49]. Trendiness increases consumer involvement by informing customers of the latest developments through social media promotion [9]. The materials presented in online SMMAs must be contemporary and pertinent to fashion brands. This shows that brands adhering to current trends foster a greater sense of connection between consumers and their products. Fashion brands must also enhance the trendy attributes of social media advertisements to boost client engagement [50]. Customers are more inclined to respond to content linked to trendiness in online social media advertising and develop emotional connections [6,51]. Therefore, the incorporation of the trendiness element in fashion brands should be regarded as a pertinent element in SMMAs. Consequently, we hypothesized the following:

H2:

Trendiness positively influences brand love.

2.4. Customization and Brand Love

Customization refers to the creation of a service product according to customer requirements or specific needs [29]. Marketers use social media platforms to deliver personalized messages or content to their target audience. Customization techniques are employed by showing specific content according to customer needs and preferences. This strategy can create more value for customers, with positive results, and personalized messages can develop strong associations between brands and consumers [3]. The contents shared through customized advertisements highlight the details regarding product quality with the concerned customer, who is looking for similar products or services [52]. Abbasi et al. [53] posited that customers who see personalized content through social media advertising identify with it and assimilate the content more quickly, develop a positive association, and have a high probability to take positive steps to address their needs. Godey et al. [54] affirmed that SMMAs require customization for marketers to adapt services to customer preferences. Stronger customer–brand interactions are fostered by social media platforms that use technology to customize brand messages [3]. By providing bespoke material that suits personal tastes, such as customized Facebook posts, customization improves the customer experience. As a result, social media platforms enable personalized interactions, enhancing brand relationships [55]. The ability to customize product recommendations, personalized advertisements, and interactive experiences on social media platforms fosters a sense of belonging and attachment [56,57]. These tailored experiences can contribute to brand love. Therefore, the following was hypothesized:

H3:

Personalization positively influences brand love.

2.5. WOM and Brand Love

WOM is a communication method that involves sharing recommendations by individuals and organizations regarding a product or service aimed at delivering customized information [58]. This addresses customers’ views on the likelihood that other consumers will support and share their experiences on social media [59]. Consumers engage with social media by commenting, enjoying, and sharing content, often reflecting positive and negative experiences [60]. The prevalence of interactive communication on websites reflects considerable public interest, as evidenced by positive feedback and contributions to the online community.

Positive online reviews suggest increased engagement [61] and act as key indicators for consumers, offering insights into adoption and purchasing behavior. This indicates a promotional aspect through word of mouth endorsements and favorable assessments of a product’s value. In the social media advertising context, consumers share their experiences with others, regardless of their knowledge or familiarity with a product or brand [62]. Incorporating word of mouth elements into online SMMAs significantly enhances customer connections with advertising from online fashion apparel brands. We assert that word of mouth significantly influences customer perceptions and enhances emotional connections to brands. Positive endorsements, user-generated content, and customer testimonials disseminated via social media substantially impact consumer trust and engagement [63,64]. This trust-based relationship fosters brand attachment, as customers depend on social proof to affirm their emotional loyalty to a brand. Social media platforms enable the extensive dissemination of word of mouth, enhancing a brand’s credibility and attractiveness. Active dissemination of positive consumer experiences enhances organic brand advocacy, thereby strengthening the community-oriented perspective of brand loyalty. The capacity of word of mouth to strengthen emotional connections underscores its significance for strong associations with customers on digital platforms. Hence, the following was hypothesized:

H4:

Word of mouth positively influences brand love.

2.6. Interaction and Brand Love

Social media interaction involves the mutual connection and sharing of information or ideas with customers with similar interests [38]. This interaction between consumers and brands improves understanding of a brand’s value [65] and customer expectations [66]. Perceptual comprehension can cultivate a strong link between brands and consumers. Marketers can improve brand–consumer interactions by promoting discussions or dialogue about the brand [67]. Interactivity not only disseminates information but also develops consumer attitudes and behaviors [68,69]. Instead of passivity, social media advertising fosters customers’ psychological engagement and motivates them to participate actively in brand-related activities. These actions inspire customers to feel connected with the brands through engaging in discussions and feel part of the communication process.

Studies in the fashion and luxury brand context have demonstrated that interaction profoundly affects customers’ brand equity, perceived experience, store love, and emotions toward the brand [3,17,70]. Moreover, interactivity as part of SMMAs has been reported to influence brand lovemarks (brand reflecting love and respect) in luxury brands [55]. Therefore, we proposed the following:

H5:

Interaction positively influences brand love.

2.7. Brand Love and CBE

Conceptualization of CBE is aligned with previous scholars who favor the multidimensional aspects of CBE. This notion of CBE includes both non-transactional and transactional interactions between firms and customers [71]. CBE is essential for the profitability and future growth of the organization, as these indicators increase through repurchases, referrals, and positive feedback [12]. Organizations currently emphasize the significance of long-term customer partnerships rather than achieving transactional outcomes. Contemporary marketing emphasizes the importance of customer emotional connection and fostering enduring relationships. Brand love is essential for customer–brand relationships [72]. Brand love affects customer perceptions, brand loyalty, electronic word of mouth, purchase intentions, and price sensitivity [48,55,73]. Subsequent research indicates that brand love within social media represents an evolving concept that remains inadequately examined regarding the impact of SMMAs on the brand–consumer relationship and CBE [43]. Drawing on S–O–R theory, we propose that customers’ emotional connections developed based on their interaction with a brand’s SMMAs are most likely to engage in positive word of mouth and defend the brand in case of criticism from rivals. Similarly, customers with strong bonds with the brands want the brands to achieve success as compared with their competitors and feel motivated to contribute to development and co-creation through knowledge sharing and constructive feedback. Therefore, we proposed the following:

H6:

Brand love positively influences customer social influence.

H7:

Brand love positively influences customer referrals.

H8:

Brand love positively influences customer purchase intentions.

H9:

Brand love positively influences customer knowledge sharing.

2.8. Moderating Role of Gender

Schema theory posits that individuals acquire knowledge via internalized cognitive frameworks, referred to as gender schemas, which shape their perceptions and emotional responses to brand-related stimuli [74]. Recent research demonstrates that these schemas continue to affect behavior, especially in digital contexts [75,76]. A study on SMMAs revealed that gender substantially impacted the efficacy of social media tactics in linking individuals to their businesses and enhancing engagement [30]. This result substantiates the idea that gender-specific cognitive processing methods affect consumers’ emotional affiliations with corporations via social media stimuli.

Ibrahim and Aljarah [30] illustrate that gender substantially affects the influence of SMMAs on consumers’ self-brand connection and engagement behaviors on Instagram. This suggests that male and female consumers perceive and emotionally respond to social media stimuli through distinct cognitive frameworks. Fetais, Algharabat, Aljafari, and Rana [55] investigated luxury fashion brands and determined that community participation and lovemark, as elements of brand affection, act as intermediates between social media marketing and brand loyalty. The predominant respondents were female, suggesting a greater degree of emotional receptivity within this demographic. Males and females may display differing views and emotions concerning the same SMMAs, including personalization, entertainment, engagement, trendiness, and word of mouth communication. This may augment individuals’ valuation of the brand across multiple dimensions. Gender substantially affects the level of connection individuals experience toward SMMAs. Hence, we proposed the following:

H10:

Gender moderates the effect of entertainment on brand love.

H11:

Gender moderates the effect of trendiness on brand love.

H12:

Gender moderates the effect of customization on brand love.

H13:

Gender moderates the effect of word of mouth on brand love.

H14:

Gender moderates the effect of interaction on brand love.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sample Size Calculation

This study used G Power software for the sample size calculation. Using parameters such as f2 = 0.15, power = 95%, and significance level = 0.05, G*Power 3.1 calculated a sample size of 144 for the present study. Scholars have advised a minimum sample size of 200 plus to test for structural equation modeling in SmartPLS 4 software [77]. Following the scholars’ guidelines (Hair, Hollingsworth, Randolph and Chong [77]) and the results of G Power, the minimum sample size was set to 350 respondents.

3.2. Data Collection Procedure

For this study, we used a cross-sectional survey design in which data were collected from customers who had purchased fashion clothing brands (such as “Gul Ahmed, Limelight, Nishat Linen, Khaadi, Sana Safinaz, Bonanza, Alkaram Studio, J., Maria B., and Beech Tree”) online in Pakistan. These individuals engage more with the brand’s SMMAs, which play a vital role in maintaining their interests and fostering their engagement.

A convenience sampling technique was used to select respondents who met the following conditions: (1) they actively follow the social media pages of prominent fashion brands, (2) they have made purchases from these brands after watching their online campaigns, and (3) they have also contributed to the brand through engagement activities. This sample strategy guaranteed the selection of respondents who were socially and commercially engaged with the brands, thus enhancing the validity and reliability of the data obtained.

In view of the objective of this study, an online survey was administered to measure three primary constructs: SMMAs, brand love, and customer engagement. To ensure clarity and understanding of the survey instrument, a pilot test was conducted with 40 respondents before proceeding with the full-scale data collection. The respondents were selected based on the predefined selection criteria. We initially formally contacted the respondents from the brand’s social media groups and pages, obtained their consent to participate in the survey, and ensured that there would be no foreseeable risks or harm to potential respondents. Their identification and personal information would be kept confidential. After seeking permission, we shared the Google Form link and requested that they fill out the survey form. Following the same procedure, we shared a full-scale survey and received 350 completed responses for further analysis. Initially, we conducted a preliminary assessment for missing values, discarded inconsistent responses, and used 297 responses for further data analysis using SPSS Statistics 31 and SmartPLS 4 software.

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the respondents who participated in this study. All the respondents were Pakistani citizens; among them, 30.1% were male and 69.1% were female. More importantly, 54.50% of the total respondents were single, while 41.5% were married, and 4% were categorised as other. In terms of monthly income, the majority (57.5%) confirmed earning between PKR 30,000 and 80,000, while 30.5% and 6.3% respondents belonged to the PKR 81,000 to 130,000 and PKR 131,000 to 180,000 income ranges.

Table 1.

Demographic details.

Common method bias (CMB) is a common issue researchers face in their studies, where “CMB occurs when the estimates of the relationships between two or more constructs are biased because they are measured with the same method [78].” The issue of the CMB generally leads to inflated or deflated results. Self-reported surveys are a common source for this problem. We used Harman’s single-factor test in SPSS to check for common method bias. This test is widely accepted and ensures the integrity of the study’s findings. The results showed that the variance explained by a single factor extracted from the principal component analysis was 16.50%, which is less than 50%. Hence, there is no CMB in the data. To overcome the possibility of social desirability bias in the responses, we provided respondents with a guarantee that their personal identities and information would never be disclosed to any entity. This assurance of confidentiality gave them confidence, impartiality, and reduced pressure, which typically leads to avoiding social desirability bias. This shows that the data collected for this study had no CMB issues and provided valid results. Furthermore, we also used VIF (Variance Inflation Factor) to assess the CMB; for this connection, we estimated the internal VIFs between constructs. The VIFs of all the between-constructs ranged from 1 to 2.143, which are below the desired threshold point of 3.00 [79]. Furthermore, the theory strongly supported the independent identity of these constructs. Therefore, there is no major issue of multicollinearity in the data collected.

The present study also used skewness and kurtosis measurements to assess the data normality, even though SmartPLS analysis does not require it. Skewness and kurtosis were within +2 and −2. This shows that the data used for the analysis had a normal distribution.

3.3. Measures

The measuring instruments for the study variables were derived from prior research. All items were evaluated using a five-point Likert scale. The measures and their operational definitions are provided in Appendix A.

SMMAs: This construct, which comprised five dimensions (entertainment, trendiness, customization, word of mouth, and interaction), was measured using 13 items, adapted from [3,54]. A sample item is “Clothing fashion brands’ social media provided customized services.”

Brand love: Brand love was assessed utilizing three questions, developed by Koo and Kim [16]. A sample item is “I love my favorite clothing brand.”

Customer engagement: Customer engagement comprised four dimensions, such as social influence, referrals, purchase intentions, and knowledge sharing, which were assessed using 15 items adapted from Kumar and Pansari [12]. A sample item is “I will purchase other products from the clothing brand in the future.”

4. Results

Data were analyzed using the PLS-SEM technique. Partial Least Squares (PLS) is advantageous for small sample sizes and does not need normally distributed data [80]. Hair, Risher, Sarstedt, and Ringle [80] observed that PLS-SEM surpassed CB-SEM in terms of both statistical and predictive power. Following Anderson and Gerbing [81], the data analysis was conducted in two phases. Phase one assessed the reflective measurement model, whereas phase two examined the structural model.

- Step 1: Measurement Model Assessment

Table 2 presents the results of the measurement models used in the study. According to these guidelines, the factor loadings of all individual measures should be equal to or greater than 0.708 [82]. Table 2 demonstrates that the factor loadings of all the items measuring each construct exceeded the threshold value of 0.708, confirming adequate individual item reliability. Parameters, such as Cronbach’s alpha, Composite Reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE), were used to assess the convergent validity of the constructs. Table 2 confirmed that all values for Cronbach’s alpha, CR, and AVE for all the constructs exceeded the recommended thresholds of 0.708, 0.70, and 0.50, respectively, thereby validating the internal consistency and convergent validity of the constructs used in this study [82]. Moreover, correlation Table 3 also shows that the strength of the relationship between variables is positive and moderate, ranging from 0.029 to 0.77, confirming no sign of multicollinearity between the variables [80,83]. This study used the HTMT criterion to check the discriminant validity. Table 4 shows that the HTMT values of all the variables are lower than the threshold value of 0.90 and establishes discriminant validity among all the dimensions of the discriminant.

Table 2.

Measurement model.

Table 3.

Correlation analysis.

Table 4.

Heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT) matrix.

- Step 2: Structural Model Analysis

SEM analysis was used to identify how the independent variables explained variance in the dependent variables. For model estimation, we assessed the beta values (β), t-values, R2, and effect sizes (f2). We assessed the statistical significance of our structural model parameters using bootstrapping with 5000 subsamples. Table 5 shows the summary of the results and their corresponding significance levels.

Table 5.

Structural model assessment.

This study tested the direct effects of SMMAs’ dimensions (entertainment, trendiness, customization, word of mouth, and interaction) on brand love and its subsequent influence on CBE dimensions. The PLS-SEM path analysis results are presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3. The results confirm that entertainment has a positive and statistically significant effect on brand love (H1: β = 0.177, t = 3.466, p < 0.001). Similarly, trendiness, customization, and word of mouth have statistically significant positive effects on brand love (respectively, H2: β = 0.240, t = 5.216, p = 0.000; H3: β = 0.306, t = 5.861, p = 0.000; H4: β = 0.219, t = 2.925, p = 0.003). The findings support hypotheses H1, H2, H3, and H4. The results also confirm that customization explained the highest variance in brand love, whereas trendiness, word of mouth, and entertainment explained moderate variances. Contrary to these findings, the interaction does not have a statistically significant effect on brand love and led to the rejection of H5 (β = 0.030, t = 0.567, p = 0.571).

Figure 2.

PLS-SEM path analysis results (dotted lines indicate moderation paths).

Figure 3.

PLS-SEM path analysis results (dotted lines indicate moderation paths).

This study also tested the direct effect of brand love on the CBE dimension; the findings confirm that brand love strongly predicts CBE dimensions (H6, H7, H8, and H9), positively influencing social influence (β = 0.507, t = 12.949, p = 0.000), referrals (β = 0.436, t = 8.171, p = 0.000), purchase intentions (β = 0.153, t = 2.787, p = 0.005), and knowledge sharing (β = 0.520, t = 10.990, p = 0.000). This highlights that brand love is a prerequisite for meaningful customer engagement. Together, these variables (entertainment, customization, and word of mouth) accounted for 54.6% of the variation (R2 = 0.546) in brand love. At the same time, brand love explained 25.7%, 19.0%, 25.7%, 0.023%, and 27.1% variances in social influence, referrals, purchase intentions, and knowledge sharing, respectively. These values reflect substantial explanatory power, demonstrating that the predictors are effective in explaining the outcomes.

Table 5 also shows the f2 statistics used to explain the substantive effect of predictor variable. f2 values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 are categorized as small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively. The results show entertainment (f2 = 0.041) and word of mouth (f2 = 0.049) demonstrated a small effect size, which confirmed that both variables positively influence brand love; however, the impact is modest. On the other hand, customization (f2 = 0.113) and trendiness (f2 = 0.095) evidenced stronger effect sizes, which demonstrated that their relative contributions in explaining brand love are higher as compared with other antecedents. Regarding the consequences of brand love, the effect sizes highlight pivotal differences; specifically, brand love demonstrated the highest effect on knowledge sharing (f2 = 0.371) and social influence (f2 = 0.346), which underscores the contribution of brand love (emotional connection) in enhancing consumers’ ability to share knowledge for brand usability and influencing others to prefer that brand during purchase decisions. Contrary to the effects of brand love on referrals (f2 = 0.234) and repurchase intention (f2 = 0.024), the effects are relatively medium and small. Furthermore, SRMR (standardized root mean square residual) is a vital indicator widely used to assess the model fit in SmartPLS [80]. The obtained SRMR value of the model proposed in the present study is 0.05 < 0.08. These findings confirm a satisfactory model fit between the empirical data and the proposed model. Hence, the model shows adequate explanatory power and an appropriate level of the residual.

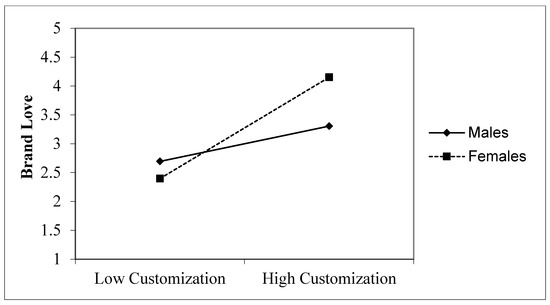

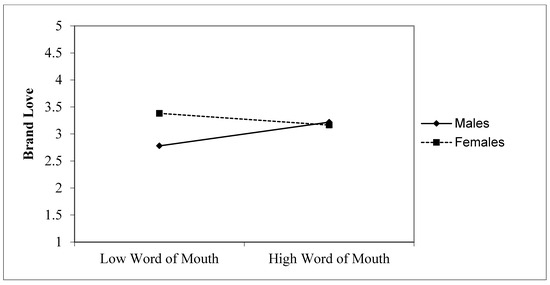

Moderation Analysis

This study tested the moderating effect of gender (a dichotomous variable) to identify the influences of SMMAs (entertainment, trendiness, customization, word of mouth, and interaction) on brand love. The results in Table 6 reflect that H12 and H13 are accepted as statistically significant results; however, H10, H11, and H14 are rejected because of the statistically insignificant role of gender. The fact that H10, H11, and H14 show no gender difference in explaining the effect of entertainment, trendiness, and interaction on brand love means that SM characteristics such as entertainment, trendiness, and interaction are important for both males and females, with no gender difference. The moderation graph (Figure 4) confirms that the effect of customization on brand love varies with respect to gender difference, and the results are statistically significant, and thus, H12 is accepted. When the customization increases, brand love increases for both males and females; however, the effect is higher for females than for males. This shows that females feel more positive emotions and develop love for the fashion brands when they receive customized offers tailored to address their fashion clothing needs. The moderation graph (Figure 5) shows that gender moderates the influence of word of mouth on brand love such that the effect is higher for males than for females (supporting H13). This confirms that males reflect strong brand love when they receive confirmation regarding brand authenticity from other sources in the form of word of mouth. In contrast, females, who develop brand love at an initial level, are not affected by the word of mouth generated by other users at the later stages, and once developed, their brand love stays relatively constant with the brand. The findings confirmed that organizations should strategize their policies for male and female customers separately.

Table 6.

Moderation.

Figure 4.

Moderation role of gender between customization and brand love.

Figure 5.

Moderation role of gender between word of mouth and brand love.

5. Discussion

The findings of our study provide a thorough evaluation of the predictors and outcomes of brand love in the context of Pakistan’s fashion apparel brands. This study was carried out to fill the knowledge gap identified by prior empirical research in SMMAs and the CBE domain [84,85,86]. Past studies conceptualized SMMAs as a multidimensional higher-order construct comprising entertainment, trendiness, customization, word of mouth, and interaction dimensions [87,88,89]. Higher-order constructs measured the collective effect of SMMAs on consumer attitude and behavior, often overlooking the unique contribution of individual dimensions. Addressing this limitation, the present study advanced the literature by testing the dimensional level effect of SMMAs. It offered a unique perspective on how each dimension contributes to the development of customer brand love.

In addition, previous studies predominantly focused on brand loyalty as an outcome of brand love [17,55] and overlooked exploring the impact of brand love on CBE, a broader construct comprising four dimensions (social influence, referrals, purchase, knowledge), which carries pivotal theoretical and practical implications [12]. To fill these gaps, we proposed and empirically tested the model grounded in S–O–R theory, which explains the underlying mechanism of how the dimensional level effect of SMMAs (S) elicits brand love (O), which, in turn, triggers CBE (R). The SEM results revealed that entertainment-oriented social media marketing activities (SMMAs) evoke positive emotional responses that strengthen consumers’ brand love. Within the S–O–R framework, entertainment operates as a hedonic stimulus that triggers affective organismic reactions, such as joy and emotional resonance, which, in turn, cultivate deeper attachment to the brand. This finding corroborates Kulikovskaja et al. [90], who confirmed entertainment as a key enabler of consumer–brand relationship development. In digital interactions, entertainment increases engagement through sensory appeal, enjoyment, and emotional transmission—factors that also characterize luxury fashion branding, where visual pleasure and experience storytelling cultivate emotional bonds and lasting loyalty.

Second, trendiness emerged as another vital predictor of brand love; this finding is consistent with Seo and Park [44], who identified trendiness as the strongest determinant of brand equity in the air transport context. Within the fashion industry, trendiness reflects a brand’s ability to signal uniqueness, relevance, and cultural knowledge, which fulfill consumers’ symbolic and aspirational needs. The findings of the present study support this logic by establishing that trendiness not only triggers cognitive evaluation but also enhances effective evaluation, which reinforces the emotional connection between brand and customer. In Pakistani culture, which emphasizes social image and values peers’ perception and opinions, association with prestigious, trendy brands facilitates self-expression and receiving social validation, which contributes to a deepening emotional connection with the brand in the form of brand love. The present study confirmed that customization acts as a pivotal determinant of brand love. This evidence affirmed the previous research work, which showed that customized experiences increase customers’ association with the brands [91,92]. Customized communication provides value to customers by allowing firms to disseminate specific information as per their preferences. Brands may address individual requirements through individualized communication, establishing a sense of importance and mutual understanding. Drawing on the S–O–R framework, personalized messages evoke emotional satisfaction among individuals and transform commercial exchanges into emotional connections.

Furthermore, WOM positively influenced brand love, supporting the findings of Lee et al. [93], who discussed the impact of peer-generated information on trust and emotional investment. Individuals tend to believe the information provided by other customers is more credible and authentic, which leads to building their confidence and overcoming uncertainty. WOM increases brand affinity in online communities by acting as a social reinforcement mechanism that turns group engagement into one-on-one relationships. These findings enhance our comprehension of how digital stimuli (SMMAs) induce emotional physiological responses (brand love) and behavioral engagement outcomes, which is aligned with the S–O–R paradigm. This study builds upon prior research by illustrating that entertainment, trendiness, customization, and word of mouth (WOM) elicit emotional responses rather than merely cognitive ones, shifting the perspective from transactional to relational interpretations of social media marketing.

In addition, Hudson et al. [94] highlighted the role of interaction in explaining consumer-related outcomes. However, in contrast, the present study identified that interaction had a statistically insignificant impact on brand love, which implies that interactions may contribute only to short-term engagement, which does not always lead to long-term attachment. The reason for this insignificant effect can be ascribed to the nature of interaction in the Pakistani apparel fashion context, which is functional, task-oriented, and informative rather than emotional [95]. Aligned with the S–O–R theory, such informational and task-related stimuli provoke cognitive rather than emotional evaluations, which supports the insignificant effect of interaction on brand love. Moreover, cultural norms in Pakistan that stress minimal self-disclosure, modesty, and formality [96] may reduce people’s emotional involvement while commenting and sharing brand-related information online, and do not lead to brand love.

With respect to the outcomes of brand love, the findings confirmed the statistically significant influence of brand love on CBE dimensions (“social influence, knowledge, referrals, and purchase intentions”). Specifically, brand love exerted strong influences on social influence, knowledge sharing, and referrals. These results are consistent with Lee and Hsieh [97], who demonstrated that social media brand communities are a vital determinant of brand love, which motivates consumers to engage in social sharing behaviors. Furthermore, brand love also evidenced positive influence on consumer purchase intentions, which further validates the assertions about the importance of brand love in driving purchase intention [98]. The results of the present study confirmed that brand love (emotional connection) not only positively shapes customers’ purchase intentions (transactional outcome) but also enhances their social engagement behaviors (referrals and social influences).

Contrary to past studies, which confirmed the moderating role of gender on the collective effect of SMMAs on customer engagement and self-brand connection [30], the present study painted a more nuanced picture by testing gender differences on the dimensional level influences of SMMAs. Surprisingly, gender difference is only found in explaining the influence of customization and word of mouth on brand love. Gender does not moderate the effects of entertainment, trendiness, and interaction on brand love. The findings confirm that females are more influenced by personalized messages compared with males, and the effect of personalization is contingent on demographic factors. This study offers significant theoretical insights and enhances our understanding of how and why SMMAs might elevate CBE in fashion apparel firms in Pakistan. These findings hold significant value for scholars and practitioners in the context of digital influence and the transformation of fashion apparel brands.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study provides significant theoretical contributions in SMMAs and CBE domains. First, past studies have investigated the aggregate influence of SMMAs (customization, trendiness, word of mouth, and interaction) on consumer attitude and behavior [54,55,99,100,101], which undermines theoretical rigor with limited insights.

Unlike prior research, the present study extended the S–O–R framework by testing the dimensional level effect of SMMAs on brand love and subsequent influence on engagement behaviors. The present study evidenced that customization and trendiness are the strongest drivers of brand love as compared with entertainment and word of mouth, while interaction does not have a statistically significant effect. This made it clear which aspects of SMMAs are more critical than others in generating brand love. Hence, identification of the differential impact of SMMAs in creating brand love and its subsequent influence on engagement behaviors dimensions (such as purchase intention, referrals, word of mouth, and knowledge sharing) strengthens the emotional pathway embedded in the S–O–R framework [102,103].

Finally, this research advances the application of schema theory [26] by testing how gender moderates the impact of SMMAs on brand love. Prior studies have revealed a gender difference between SMMAs and customer engagement relationships [30]. This study contributed to the literature by confirming that gender moderates certain SMMA aspects, such as the effects of customization, which were statistically significant and more evident among female consumers, and the effect of word of mouth was more substantial among male consumers. This is a novel finding contrary to the prior studies, suggesting gender works as a moderator across consolidated SMMAs and confirms the influence of SMMAs on brand love varies with respect to gender differences.

5.2. Managerial Implications

This study presents several practical implications for fashion brand managers for enhancing customer relationships and brand love. The findings emphasize that customization and trendiness show the most decisive influence on the formation of brand love. This shows that managers should use personalized marketing initiatives with social media tools to ensure that information regarding fashion clothing design, color, and size suggestions is disseminated according to the taste of the target audience. A customized approach not only improves customer experience but also fosters long-term attachment to the brand [104]. Fashion brands should create captivating and interactive posts that resonate with their target audiences with AI tools and target them through CRM systems. The brand managers should also be open to incorporating changes as per evolving customer needs, with a focus on female customers, as female customers showed more emotional responses to the brands sharing customized information regarding their specific needs. This strategy can lead to a strong customer and brand emotional connection.

Likewise, managers should continuously integrate trend-oriented content into their social media strategies, such as limited-edition collections, innovative designs, and a variety of fabric quality and fashion tips as per the requirements of the season, which can be very useful in flourishing long-term customer relationships. Such initiatives reinforce novelty and relevance, which are critical for sustaining brand resonance in fast-changing fashion markets.

Entertainment and word of mouth are also meaningful determinants of brand love, although their effect was relatively small. Furthermore, males showed more emotional response to word of mouth as compared with female customers. This indicates that the brand managers should share authentic and credible comments, testimonials, and peer endorsements with special focus on the male segments of the target market. This strategy will strengthen the male customers’ trust in the brand and develop a long-term connection with the brand. Similarly, the managers can use entertaining content such as funny short videos, memes, and influencers to develop emotional content for customer engagement. The research indicates that brand love predominantly affects collective behaviors, such as knowledge sharing, social influence, and referrals, rather than merely influencing transactional outcomes like purchase intention. This indicates that management must alter its approach to consumer engagement. Rather than perceiving it solely to generate revenue, they should recognize it as a method for developing the community. Encouraging customers to provide styling advice, create fashion content, or influence their friends’ brand choices can enhance brand equity more efficiently than simply prompting repeat purchases.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study has limitations despite its key findings. First, as this study used a cross-sectional research method and applied a convenience sampling technique for respondents’ selection, in order to obtain generalized results and ensure causality, future researchers could apply longitudinal data collection using probability sampling to obtain more rigorous results. Moreover, this study only tested the effect of SMMAs on brand love and its influence on CBE (the direct effects). Future studies can extend this framework with the inclusion of other important unexplored intervening variables, such as emotions, affection, brand image, and brand satisfaction [53]. Finally, future studies could also investigate the moderating role of age, income, or digital literacy, with cross-cultural comparisons between developed and developing countries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and M.A.A.; methodology, M.S. and M.A.A.; software, M.S.; validation, M.S., M.A.-u.-R. and M.A.A.; formal analysis, M.S. and M.A.A.; investigation, M.S. and M.A.-u.-R.; resources, M.S.; data curation, M.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S. and M.A.A.; writing—review and editing, M.S., M.A.-u.-R. and M.A.A.; visualization, M.S.; supervision, M.S.; project administration, M.S. and M.A.-u.-R.; funding acquisition, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of National Textile University, Faisalabad, Pakistan (protocol code NTU/FBS/24-017 and date of approval 23 May 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions related to the protection of participant privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Operational Definitions and Measures

| Social Media Marketing Activities (SMMAs) |

| Entertainment (ENT): The extent to which brand social media contents are enjoyable and entertaining [3,54]. |

| The content shared by this fashion brand on social media is entertaining. |

| The videos, images, or stories posted by this brand are enjoyable to watch. |

| Trendiness (TRE): The degree to which the brand’s social media provides the latest and fashionable information about apparel products and industry trends [3,54]. |

| This brand’s social media pages provide the latest fashion trends. |

| The information shared by this brand helps me stay current with fashion trends. |

| Customization (CUS): The extent to which the brand’s social media platforms enable customers to communicate, share opinions, and interact with the brand and other users [3,54]. |

| I receive recommendations from this brand that fit my style preferences. |

| The social media page provides suggestions based on my past interactions. |

| This brand’s social media shows content that matches my fashion interests. |

| Word of Mouth (WOM): The extent to which customers share brand information or recommendations with others through social media [3,54]. |

| I often share this brand’s social media posts with my friends. |

| I post or comment positively about this brand online. |

| I recommend this brand to others on social media. |

| Interaction (INT): The degree to which consumers can communicate, share, and exchange information with the brand [3,54]. |

| I can interact directly with the brand through its social media platforms. |

| The brand actively responds to customer comments and feedback. |

| I feel connected to other followers of this brand. |

| Brand Love (BL): Brand love refers to the degree of passionate emotional attachment a satisfied consumer has toward a particular brand [16]. |

| I feel emotionally connected to this fashion brand. |

| I love this brand more than other fashion brands. |

| I am passionate about this fashion brand. |

| Customer Behavioral Engagement (CBE): CBE is an abstract concept defined “as a second-order construct consisting of four dimensions: customer purchases, customer references, customer influence, and customer knowledge/feedback” [12]. |

| Purchase Intentions (PI): The consumer’s conscious plan or likelihood to buy a particular fashion brand in the future [15,105]. |

| I intend to purchase this brand’s products again. |

| I will choose this brand over others when shopping. |

| I would recommend this brand when someone asks for advice. |

| Referrals (REF): The voluntary act of recommending or referring the brand to other potential customers through social networks [15]. |

| I have recommended this fashion brand to friends. |

| I will share positive experiences about this brand online. |

| I talk about this brand when discussing fashion trends. |

| I will encourage others to try this brand. |

| Social Influence (SI): The degree to which a customer affects others’ attitudes and purchase behaviors through word of mouth, reviews, and opinion leadership [15]. |

| I influence others’ choices of fashion brands. |

| My posts about this brand attract others’ attention. |

| People consider my opinion before choosing a fashion brand. |

| My views about this brand affect others’ purchasing decisions. |

| Knowledge Sharing (KNS): The extent to which customers provide ideas, feedback, or suggestions to improve the brand’s offerings [15,105]. |

| I provide feedback to this fashion brand on its products or campaigns. |

| I share suggestions to improve this brand’s social media content. |

| I give ideas to help the brand design better products. |

| I share insights with other consumers about this brand. |

References

- Al Kurdi, B.; Nuseir, M.T.; Alshurideh, M.T.; Alzoubi, H.M.; AlHamad, A.; Hamadneh, S. The impact of social media marketing on online buying behavior via the mediating role of customer perception: Evidence from the Abu Dhabi retail industry. In Cyber Security Impact on Digitalization and Business Intelligence: Big Cyber Security for Information Management: Opportunities and Challenges; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 431–449. [Google Scholar]

- Cagatin, C.S. The societal transformation: The role of social networking platforms in shaping the digital age. Interdiscip. Soc. Stud. 2024, 3, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.J.; Ko, E. Do social media marketing activities enhance customer equity? An empirical study of luxury fashion brand. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1480–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guttena, R.K.; Wu, C.H.-J.; Atmaja, F.T. The influence of brand-related social media content on customer extra-role behavior: A moderated moderation model. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2024, 33, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, M.D.; Farooq, S.; Siddiqui, M.O.R.; Khan, D.R. Textile dynamics in Pakistan: Unraveling the threads of production, consumption, and global competitiveness. In Consumption and Production in the Textile and Garment Industry: A Comparative Study Among Asian Countries; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, A.M.; Ali, M. Social media marketing activities and luxury fashion brands in the post-pandemic world. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2024, 36, 2104–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetta, L.D.A.; Hakim, M.P.; Gastaldi, G.B.; Seabra, L.M.A.J.; Rolim, P.M.; Nascimento, L.G.P.; Medeiros, C.O.; da Cunha, D.T. The use of food delivery apps during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil: The role of solidarity, perceived risk, and regional aspects. Food Res. Int. 2021, 149, 110671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, S.F.; Alanadoly, A.B. Driving customer engagement and citizenship behaviour in omnichannel retailing: Evidence from the fashion sector. Span. J. Mark.-ESIC 2024, 28, 98–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shin, H.; Burns, A.C. Examining the impact of luxury brand’s social media marketing on customer engagement: Using big data analytics and natural language processing. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 125, 815–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nibras, S.; Gunawan, T.A.; Tan, G.W.-H.; Lo, P.-S.; Aw, E.C.-X.; Ooi, K.-B. Engage to co-create! The drivers of brand co-creation on social commerce. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2025, 43, 440–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, L.H.; Woyo, E.; Pham, T.H.; Truong, D.T.X. Value co-creation and destination brand equity: Understanding the role of social commerce information sharing. J. Hosp. Tour. Insights 2023, 6, 1796–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Pansari, A. Competitive advantage through engagement. J. Mark. Res. 2016, 53, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Back, K.-J. Antecedents and consequences of customer brand engagement in integrated resorts. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 75, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Conduit, J.; Sweeney, J.; Soutar, G.; Karpen, I.O.; Jarvis, W.; Chen, T. Epilogue to the special issue and reflections on the future of engagement research. J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 32, 586–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Aksoy, L.; Donkers, B.; Venkatesan, R.; Wiesel, T.; Tillmanns, S. Undervalued or overvalued customers: Capturing total customer engagement value. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, W.; Kim, Y.-K. Impacts of store environmental cues on store love and loyalty: Single-brand apparel retailers. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2013, 25, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, R.U. Social media marketing, shoppers’ store love and loyalty. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2022, 40, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafez, M. The impact of social media marketing activities on brand equity in the banking sector in Bangladesh: The mediating role of brand love and brand trust. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2021, 39, 1353–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, M.; Porcu, L.; Prados-Castillo, J.F.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F. The Role of Social Media in Building Islamic Banking Consumer Engagement: Analysing the Impact of Brand Personality Traits and Brand Love. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2024, 1, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changani, S.; Kumar, R. Social Media Marketing Activities, Brand Community Engagement and Brand Loyalty: Modelling the Role of Self-brand Congruency with Moderated Mediation Approach. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohaib, M.; Safeer, A.A.; Majeed, A. Does firm-created social media communication develop brand evangelists? Role of perceived values and customer experience. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2024, 42, 1074–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, B.; Aljarah, A. The era of Instagram expansion: Matching social media marketing activities and brand loyalty through customer relationship quality. J. Mark. Commun. 2023, 29, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, K.; Dunnan, L.; Gul, R.F.; Shehzad, M.U.; Gillani, S.H.M.; Awan, F.H. Role of social media marketing activities in influencing customer intentions: A perspective of a new emerging era. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 808525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero, J. Customer engagement behaviors in hospitality: Customer-based antecedents. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2017, 26, 565–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, S.; Panda, S.; Ghimire, A.; Kim, D.J. From engagement to retention: Unveiling factors driving user engagement and continued usage of mobile trading apps. Decis. Support Syst. 2024, 183, 114265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bem, S.L. Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychol. Rev. 1981, 88, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, B.; Aljarah, A.; Sawaftah, D. Linking social media marketing activities to revisit intention through brand trust and brand loyalty on the coffee shop facebook pages: Exploring sequential mediation mechanism. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Rahman, Z. The influence of social media marketing activities on customer loyalty: A study of e-commerce industry. Benchmarking Int. J. 2018, 25, 3882–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, B.; Aljarah, A. The role of social media marketing activities in driving self–brand connection and user engagement behavior on Instagram: A moderation–mediation approach. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2024, 27, 1723–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.F.; Amin, F.; Jan, A.; Hakak, I.A. Social media marketing activities in the Indian airlines: Brand equity and electronic word of mouth. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2024, 24, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquart, F.; Brosius, A.; de Vreese, C. United Feelings: The Mediating Role of Emotions in Social Media Campaigns for EU Attitudes and Behavioral Intentions. J. Political Mark. 2022, 21, 85–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safeer, A.A. Harnessing the power of brand social media marketing on consumer online impulse buying intentions: A stimulus-organism-response framework. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2024, 33, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, M.; Fischer, T.; Riedl, R. Impact of content characteristics and emotion on behavioral engagement in social media: Literature review and research agenda. Electron. Commer. Res. 2021, 21, 329–345. [Google Scholar]

- Bin, S. Social Network emotional marketing influence model of consumers’ purchase behavior. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Rahman, Z. Measuring consumer perception of social media marketing activities in e-commerce industry: Scale development & validation. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 1294–1307. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, M.L.; Pires, G.; Rosenberger, P.J. The influence of perceived social media marketing elements on consumer–brand engagement and brand knowledge. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 695–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athwal, N.; Istanbulluoglu, D.; McCormack, S.E. The allure of luxury brands’ social media activities: A uses and gratifications perspective. Inf. Technol. People 2019, 32, 603–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsoud, M.; Trawnih, A.; Yaseen, H.; Majali, T.E.; Alsoud, A.R.; Jaber, O.A. How could entertainment content marketing affect intention to use the metaverse? Empirical findings. Int. J. Inf. Manag. Data Insights 2024, 4, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, C.; Tuten, T. Creative strategies in social media marketing: An exploratory study of branded social content and consumer engagement. Psychol. Mark. 2015, 32, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ningrum, K.K.; Roostika, R. The influence of social media marketing activities on consumer engagement and brand knowledge in the culinary business in Indonesia. Int. J. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Algharabat, R.S. Linking social media marketing activities with brand love: The mediating role of self-expressive brands. Kybernetes 2017, 46, 1801–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.-J.; Park, J.-W. A study on the effects of social media marketing activities on brand equity and customer response in the airline industry. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2018, 66, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plume, C.J.; Slade, E.L. Sharing of sponsored advertisements on social media: A uses and gratifications perspective. Inf. Syst. Front. 2018, 20, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, B.; Hazzam, J.; Ali Qalati, S.; Aljarah, A.; Dobson, P. Building a tribe on Instagram: How User-generated and Firm-created Content can drive brand evangelism and fidelity. J. Mark. Commun. 2024, 31, 905–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazi, S.; Filieri, R.; Gorton, M. Social media content aesthetic quality and customer engagement: The mediating role of entertainment and impacts on brand love and loyalty. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 160, 113778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.M.; Battour, M.; Ratnasari, R.T.; Herianingrum, S.; Fauzi, Q.; Absah, Y.; Sari, D.K. Antecedent and Consequences of Brand Love: A Conceptual in Behavioral Loyalty. In Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Customer Social Responsibility (CSR); Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 1051–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, M.L.; Pires, G.; Rosenberger Iii, P.J.; Leung, W.K.S.; Chang, M.K. The role of social media elements in driving co-creation and engagement. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2021, 33, 1994–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeqiri, J.; Koku, P.S.; Dobre, C.; Milovan, A.-M.; Hasani, V.V.; Paientko, T. The impact of social media marketing on brand awareness, brand engagement and purchase intention in emerging economies. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2025, 43, 28–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Baek, T.H. Fostering brand love through branded memes on social media. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2025, 34, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashishth, T.K.; Sharma, K.K.; Kumar, B.; Chaudhary, S.; Panwar, R. Enhancing customer experience through AI-enabled content personalization in e-commerce marketing. In Advances in Digital Marketing in the Era of Artificial Intelligence; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 7–32. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, A.Z.; Qummar, H.; Bashir, S.; Aziz, S.; Ting, D.H. Customer engagement in Saudi food delivery apps through social media marketing: Examining the antecedents and consequences using PLS-SEM and NCA. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 81, 104001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godey, B.; Manthiou, A.; Pederzoli, D.; Rokka, J.; Aiello, G.; Donvito, R.; Singh, R. Social media marketing efforts of luxury brands: Influence on brand equity and consumer behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5833–5841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetais, A.H.; Algharabat, R.S.; Aljafari, A.; Rana, N.P. Do social media marketing activities improve brand loyalty? An empirical study on luxury fashion brands. Inf. Syst. Front. 2023, 25, 795–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, T.; Tran, T.P.; Taylor, E.C. Getting to know you: Social media personalization as a means of enhancing brand loyalty and perceived quality. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Yeh, R.K.-J.; Yen, D.C.; Sandoya, M.G. Antecedents of emotional attachment of social media users. Serv. Ind. J. 2016, 36, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J. Word of mouth and interpersonal communication: A review and directions for future research. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 586–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachmad, Y.E.; Budiyanto, B.; Khuzaini, K. Impact of Viral Marketing and Gimmick Marketing on Transformation of Customer Behavior Mediated by Influencer Marketing. Int. J. Econ. Manag. Account. 2025, 2, 221–233. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, R.; Conduit, J.; Frethey-Bentham, C.; Fahy, J.; Goodman, S. Social media engagement behavior: A framework for engaging customers through social media content. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2213–2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventre, I.; Kolbe, D. The impact of perceived usefulness of online reviews, trust and perceived risk on online purchase intention in emerging markets: A Mexican perspective. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2020, 32, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunpeng, S.; Khan, Y.A. Understanding the effect of online brand experience on customer satisfaction in China: A mediating role of brand familiarity. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 3888–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, R. Customer engagement and online reviews. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljarah, A.; Sawaftah, D.; Ibrahim, B.; Lahuerta-Otero, E. The differential impact of user-and firm-generated content on online brand advocacy: Customer engagement and brand familiarity matter. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2024, 27, 1160–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.M. @ Brand-to-@ brand: The value co-creating impact of social media interactions on consumer–brand evaluations. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2025, 19, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J. An investigation of the effect of online consumer trust on expectation, satisfaction, and post-expectation. Inf. Syst. E-Bus. Manag. 2012, 10, 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessart, L.; Veloutsou, C.; Morgan-Thomas, A. Consumer engagement in online brand communities: A social media perspective. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2015, 24, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, K.; Ketron, S. A dual model of product involvement for effective virtual reality: The roles of imagination, co-creation, telepresence, and interactivity. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 100, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.L. Editorial–what is an interactive marketing perspective and what are emerging research areas? J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2024, 18, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.A.; Amin, F. Impact of Social Media Interaction on Customer’s Brand Engagement, Emotions, Word of Mouth, and Brand Relationship Quality in Luxury Hotel Brands. In Consumer Brand Relationships in Tourism: An International Perspective, Rather, R.A., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 121–139. [Google Scholar]

- Pansari, A.; Kumar, V. Customer engagement: The construct, antecedents, and consequences. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 294–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, M.; MacInnis, D.J.; Whan Park, C. The ties that bind: Measuring the strength of consumers’ emotional attachments to brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2005, 15, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Ahuvia, A.; Bagozzi, R.P. Brand love. J. Mark. 2012, 76, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiske, S.T. Thinking is for doing: Portraits of social cognition from daguerreotype to laserphoto. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 63, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molla, A.; Duan, S.X.; Deng, H.; Tay, R. The effects of digital platform expectations, information schema congruity and behavioural factors on mobility as a service (MaaS) adoption. Inf. Technol. People 2024, 37, 81–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekar, S.B. Schema congruity in sustainable fashion influencers’ promotion of secondhand fashion. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2025, 29, 1195–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Hollingsworth, C.L.; Randolph, A.B.; Chong, A.Y.L. An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Organ, D.W. Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. J. Manag. 1986, 12, 531–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Mayfield, M. PLS-based SEM algorithms: The good neighbor assumption, collinearity, and nonlinearity. Inf. Manag. Bus. Rev. 2015, 7, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.; Alamer, A. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) in second language and education research: Guidelines using an applied example. Res. Methods Appl. Linguist. 2022, 1, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, S.C.; Sweeney, J.C.; Plewa, C. Customer engagement: A systematic review and future research priorities. Australas. Mark. J. 2020, 28, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M.; Rasul, T.; Kumar, S.; Ala, M. Past, present, and future of customer engagement. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 140, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvi, R.; Foroudi, P.; Jerez, M.J. A bibliometric review of customer engagement in the international domain: Reviewing the past and the present. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hujri, A.; Al-Hakimi, M.A.; Alshageri, S.; Vasant Keshavrao, B.; Al Koliby, I.S. The impact of social media marketing activities on brand loyalty and awareness: The mediating role of customer satisfaction in Yemen’s telecom industry. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2025, 12, 2509793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, A. Social media marketing activities for influencing voter citizenship behaviour: Brand relationship quality as a mediator. J. Mark. Commun. 2024, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurhadi, M.; Suryani, T.; Fauzi, A.A. Cultivating domestic brand love through social media marketing activities: Insights from young consumers in an emerging market. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2025, 30, 100349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulikovskaja, V.; Hubert, M.; Grunert, K.G.; Zhao, H. Driving marketing outcomes through social media-based customer engagement. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 74, 103445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobile, T.H.; Cantoni, L. Personalization and customization in fashion: Searching for a definition. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2023, 27, 665–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Lee, Y. The effect of online customization on consumers’ happiness and purchase intention and the mediating roles of autonomy, competence, and pride of authorship. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2020, 36, 403–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-L.; Liu, C.-H.; Tseng, T.-W. The multiple effects of service innovation and quality on transitional and electronic word-of-mouth in predicting customer behaviour. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 64, 102791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, S.; Huang, L.; Roth, M.S.; Madden, T.J. The influence of social media interactions on consumer–brand relationships: A three-country study of brand perceptions and marketing behaviors. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2016, 33, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.L.; Pires, G.D.; Rosenberger, P.J.; De Oliveira, M.J. Driving consumer–brand engagement and co-creation by brand interactivity. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2020, 38, 523–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2011, 2, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.T.; Hsieh, S.H. Can social media-based brand communities build brand relationships? Examining the effect of community engagement on brand love. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2022, 41, 1270–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, I.J. I trust friends before I trust companies: The mediation of WOM and brand love on psychological contract fulfilment and repurchase intention. Manag. Matters 2022, 19, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Xu, X.; Han, J.; Ko, E. The impact of digital fashion marketing on purchase intention. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2025, 37, 210–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, F.U.; Al-Ghazali, B.M. Evaluating the influence of social advertising, individual factors, and brand image on the buying behavior toward fashion clothing brands. Sage Open 2022, 12, 21582440221088858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koay, K.Y.; Ong, D.L.T.; Khoo, K.L.; Yeoh, H.J. Perceived social media marketing activities and consumer-based brand equity: Testing a moderated mediation model. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2021, 33, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodie, R.J.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Jurić, B.; Ilić, A. Customer engagement: Conceptual domain, fundamental propositions, and implications for research. J. Serv. Res. 2011, 14, 252–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Doorn, J.; Lemon, K.N.; Mittal, V.; Nass, S.; Pick, D.; Pirner, P.; Verhoef, P.C. Customer engagement behavior: Theoretical foundations and research directions. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]