Abstract

Effective website usability assessment is crucial for improving user experience, driving customer satisfaction, and ensuring business success, particularly in the competitive e-commerce sector. Traditional methods, such as expert reviews and user testing, are resource-intensive and often fail to fully capture the complex interplay between a site’s aesthetic design and its technical performance. This paper introduces an end-to-end multimodal deep learning framework that automates the usability assessment of fashion e-commerce websites. The framework fuses structured numerical indicators (e.g., load time, mobile compatibility) with high-level visual features extracted from full-page screenshots. The proposed framework employs a comprehensive set of visual backbones—including modern architectures such as ConvNeXt and Vision Transformers (ViT, Swin) alongside established CNNs—and systematically evaluates three fusion strategies: early fusion, late fusion, and a state-of-the-art cross-modal fusion strategy that enables deep, bidirectional interactions between modalities. Extensive experiments demonstrate that the cross-modal fusion approach, particularly when paired with a ConvNeXt backbone, achieves superior performance with a 0.92 accuracy and 0.89 F1-score, outperforming both unimodal and simpler fusion baselines. Model interpretability is provided through SHAP and LIME, confirming that the predictions align with established usability principles and generate actionable insights. Although validated on fashion e-commerce sites, the framework is highly adaptable to other domains—such as e-learning and e-government—via domain-specific data and light fine-tuning. It provides a robust, explainable benchmark for data-driven, multimodal website usability assessment and paves the way for more intelligent, automated user-experience optimization.

1. Introduction

Over the past decade, advances in computing have reduced reliance on traditional information-acquisition methods and transformed how users interact with online services. Websites have become essential channels for commerce, information, and public services, offering 24/7 access and features that shape user behavior and business outcomes [1,2]. Yet, merely deploying a website is insufficient; poor usability frustrates users and undermines commercial success [3,4]. ISO 9241-11 defines usability as “the extent to which a system, product or service can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction,” a standard that remains central to contemporary research [5]. In the context of websites, Cappel & Huang define it more specifically as “a quality attribute that assesses how easy user interfaces are to use” [4]. Ultimately, optimizing website usability is an ongoing challenge that extends beyond design expertise, serving as a critical indicator of site quality and a key driver of commercial success [6,7].

Traditional usability methods—including heuristic inspection, user testing, and analytical approaches such as Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA)—are informative yet resource-intensive. They suffer from high costs, slow turnaround, and inconsistent outcomes due to subjective variability and limited scalability [8]. Automated, data-driven approaches therefore offer a compelling alternative for scalable, repeatable assessment [9]. However, current automated tools and rule-based analyzers, while providing useful diagnostics, often produce inconsistent results when evaluating the same website [10]. A further limitation is their primary focus on post-development testing; this introduces a significant delay between code implementation and usability review, thereby increasing the time and cost of defect resolution [11]. Deep learning (DL), and specifically multimodal DL, can address these limitations. By learning complex interactions between visual design and measurable technical indicators, multimodal DL enables holistic, scalable, and objective usability assessments that better reflect human judgment. Despite this promise, the application of DL to usability evaluation remains underexplored, even in well-studied domains such as e-government and e-learning. Prior work has predominantly relied on unimodal data (e.g., numerical metrics), overlooking the critical interplay of diverse factors that shape user experience. To the best of our knowledge, no prior study has developed a comprehensive multimodal DL framework for website usability assessment that integrates modern visual backbones, advanced fusion strategies, and explainable predictions.

To address this gap, this study introduces a numeric–visual multimodal deep learning framework tailored for fashion e-commerce usability assessment. The framework integrates nine automated usability indicators (load time, mobile compatibility, image quality, contact information, feedback mechanisms, product ratings, sorting functionality, multilingual support, and payment options) with high-level visual embeddings derived from full-page screenshots. A comprehensive benchmark of backbones was evaluated for visual feature extraction, encompassing classic CNNs (ResNet152, EfficientNet-B0, DenseNet201, InceptionV3, MobileNetV2, VGG16), modern ConvNets (ConvNeXt-Tiny/Base), and vision transformers (ViT-B/16, Swin-Base). Three fusion paradigms were systematically compared under identical training and evaluation protocols: Early Fusion (feature-level), Late Fusion (decision-level), and Cross-Modal Fusion (interaction-level)—the latter of which implements bidirectional attention, multiplicative interactions, and a learned gating mechanism.

The study is primarily motivated by the usability challenges of fashion e-commerce websites, a domain where such issues are both pronounced and consequential. Fashion platforms exist at the intersection of aesthetic appeal and technical performance, relying on high-resolution imagery, dynamic product displays (e.g., zoom, 360° views), seasonal content updates, and visually driven buying behaviors. These factors amplify the interaction between visual design and technical metrics such as load time and mobile responsiveness [12,13,14]. The inherent tension between visual richness and functional efficiency makes fashion sites an ideal testbed for developing and validating a multimodal evaluation framework. Furthermore, the sector’s competitive nature and the direct link between user experience and conversion rates create a high-stakes environment where usability improvements yield tangible business impact. Insights derived from this domain are readily transferable to other visually driven industries and establish a rigorous benchmark for multimodal usability assessment.

To ensure representativeness, the dataset comprises 546 fashion e-commerce websites selected through a stratified screening process that balanced regional origin and traffic levels. The selection included exemplars of both high and low usability, as validated by expert heuristic review. Empirical results demonstrate that the Cross-Modal Fusion strategy yields the most robust joint representations for fashion usability prediction. When paired with the ConvNeXt backbone, this combination achieved the highest predictive performance among all evaluated models, with an accuracy of 0.92 and an F1-score of 0.89. The interpretability of the model’s predictions was achieved using Explainable AI (XAI) techniques—specifically, SHAP for global feature importance and LIME for local, instance-level explanations. These XAI analyses confirm that the model’s decisions align with established usability principles, identifying page load time and image resolution as the most influential features. These findings underscore the value of explicitly modeling the interactions between technical performance and visual design for comprehensive usability assessment.

The main contributions include the following:

- -

- A comprehensive multimodal framework that automates website usability assessment. The framework integrates visual and numerical data using three distinct fusion strategies: Early (feature-level), Late (decision-level), and Cross-Modal (interaction-level) fusion.

- -

- Benchmarks a broad set of visual backbones for visual feature extraction, evaluating a diverse set of architectures from classic CNNs (e.g., VGG16, ResNet152) to modern designs like ConvNeXt and Vision Transformers (ViT, Swin).

- -

- An automated, objective, and scalable alternative to expert-based or user-testing methods, achieving state-of-the-art performance through optimized architecture and fusion choices.

- -

- A holistic usability analysis that bridges the gap between a website’s visual design and its functional performance by jointly modeling aesthetic and technical indicators.

- -

- Ensures interpretability via XAI techniques (SHAP and LIME), which explain model predictions and validate their alignment with established usability principles.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work; Section 3 defines usability principles and evaluation criteria; Section 4 provides an overview of the proposed multimodal framework; Section 5 details the dataset compilation, including screening, collection, labeling, and preprocessing; Section 6 describes the multimodal training procedures; Section 7 specifies the evaluation metrics; Section 8 presents the experimental results; Section 9 discusses the explainable AI (XAI) analyses; Section 10 provides a general discussion of the findings; and Section 11 concludes the study by outlining limitations and proposing future research directions.

2. Related Work

The assessment of website usability has evolved through distinct methodological paradigms across various domains. This review traces that evolution—from traditional unimodal approaches to advanced multimodal methods—and concludes by articulating the specific research gap this study addresses.

2.1. Unimodal Website Usability Evaluation

A substantial body of research has tackled website usability by focusing on a single data modality. As synthesized in Table 1, these studies, while valuable within their scope, are inherently constrained to isolated facets of the user experience.

Table 1.

Unimodal Websites Usability Evaluation Approaches.

In e-government, research has prioritized efficiency, navigation, and compliance. Studies by [15] employed Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) to benchmark portal efficiency by comparing resource inputs to service outputs, providing quantitative performance scores. Meanwhile, expert-driven heuristic inspections have been used to uncover navigation and interface flaws against established usability principles [16]. Complementing these, large-scale automated audits, such as those evaluating 65 Indian portals against WCAG 1.0/2.0 [17] and 25 Hungarian sites under WCAG 2.1/EU directives [18], systematically detect accessibility violations that form the baseline of usability.

The e-learning domain has explored usability through diverse lenses. Reference [19] applied a genetic algorithm for feature selection coupled with machine learning scoring to assess efficiency, learnability, and memorability. Behavioral analytics, like the clickstream and interaction log mining by [20], offer direct insights into student satisfaction, informing UI/UX improvements. More complex modeling techniques, including hybrid MCDM-ANN and fuzzy AHP-ANN models, have been developed to evaluate overall educational website quality [21,22]. Furthermore, mixed-method evaluations combining automated tools with user surveys or think-aloud sessions yield actionable redesign recommendations [23,24], while large-scale accessibility audits of 198 Gulf universities [25] and 330 global institutions [26], alongside student surveys of platforms like Moodle and Google Classroom [27], identify specific barriers and user-reported issues.

In e-commerce, usability is closely tied to commercial success. Studies have trained models on Google Analytics and interaction logs using algorithms like k-NN, logistic regression, and random forests to predict where users struggle during shopping [28]. AI-guided UI/UX tweaks have been shown to improve user engagement [29], while PCA and fuzzy clustering group shoppers by their reported issues to reveal which problems most affect buying behavior [30]. Detailed analyses of service elements demonstrate how each component shapes overall customer experience and loyalty [31,32].

For e-banking and hospitality websites, studies target key aspects like ease of use, security, and satisfaction. Fuzzy AHP has been used to rank navigability and security factors in online banking [33], while regression combined with neural network models predicts customer satisfaction [34]. In the hospitality sector, layout analysis combined with guest surveys helps evaluate and refine site design to better match user expectations [35].

Beyond sector-specific investigations, generalizable frameworks have emerged. These include quantifying website completeness through automated feature measurement with an MLP model [36], deep learning-based frameworks for automated website aesthetics assessment [13], and the PEML model that uses logistic regression and SVMs to identify the most important website metrics [37]. Image recognition approaches using OpenCV and dlib map UI element layouts to compute visual complexity metrics [12], and other systems employ 59 usability, accessibility, and performance attributes with SVM and Random Forest classifiers for proactive evaluation [38]. ANN/LSTM pipelines that fuse temporal UX parameters like navigation time and click counts into usability scores represent a move towards more dynamic, data-driven assessments [39]. The development of intelligent tools, such as the IUE tool that combines heuristic inspection with AI-based methods [8] and the “IncWeb” concept for automatic interface transformation [40], further demonstrates the field’s progression towards automation.

Recent advances have introduced more sophisticated techniques. Generative AI has begun to influence usability assessment, with tools such as UXAgent using LLM-simulated agents to design and refine usability testing protocols [41]. Similarly, GPT-4-powered follow-up prompts in unmoderated tests provide deeper insights into existing usability issues, although they uncover few new problems, highlighting both the potential and the limitations of LLM-augmented evaluation [42].

2.2. Multimodal Websites Analysis Approaches

Recent advances in multimodal learning have produced powerful methods for web page analysis. However, most multimodal studies focus on tasks adjacent to usability—such as aesthetic scoring, phishing detection, screenshot parsing, or information extraction—rather than on human-centered usability constructs like learnability, efficiency, and satisfaction. Prior studies demonstrate the value of fusing visual and textual signals for objectives like automated aesthetic judgment via fusion models [43,44]. Other applications include phishing detection by combining URL, HTML, and screenshot features with attention mechanisms [45], and veracity analysis using BERT paired with vision backbones for misinformation detection [46].

Large pretrained vision–language systems represent a significant leap in capability. Models such as Pix2Struct [47], WebLM [48], and ScreenAI [49] offer powerful, general-purpose capabilities for screenshot parsing, element localization, and markup-aware reasoning. Benchmarks like VisualWebArena [50] evaluate these capabilities in complex web navigation tasks. The recent WebQuality dataset and its Hydra model [51] further advance multimodal web quality assessment across multiple scoring dimensions. However, these powerful models and benchmarks are engineered primarily to parse and score page content or to solve broad QA/navigation tasks; they are not explicitly designed to diagnose holistic usability. Table 2 summarizes these multimodal efforts and highlights their respective tasks.

Table 2.

Multimodal Approaches for Website Analysis.

2.3. Synthesis and Identified Research Gap

Across the studies summarized in Table 1 and Table 2, a consistent pattern emerges: most website evaluation approaches are unimodal, relying on numerical metrics, behavioral logs, or visual features in isolation. Consequently, they fail to model the critical interactions between technical performance and visual design that jointly determine user experience. Meanwhile, existing multimodal research is largely optimized for adjacent objectives—such as security, aesthetics, or general web understanding—rather than human-centric usability. Even the most comprehensive benchmark to date, WebQuality [51], targets broad “quality” rather than the ISO-anchored dimensions of effectiveness, efficiency, and satisfaction.

This leaves a significant gap: the absence of a unified, end-to-end deep learning framework that integrates heterogeneous modalities to produce both interpretable and holistic usability evaluations. This work addresses that gap by introducing a cross-modal framework that fuses visual screenshots with quantitative usability indicators, creating a unified model for comprehensive assessment. This makes the approach particularly valuable for context-sensitive domains like fashion e-commerce, where usability emerges from the complex interplay between aesthetic appeal and technical performance [52,53].

3. Essential Principles and Criteria in Website Usability Evaluation

3.1. Principles

Usability principles provide the foundational guidelines for evaluating the acceptability and effectiveness of user interfaces. Widely applied to both prototypes and existing systems, they ensure designs align with user needs and prevent the creation of unusable products [52,53]. These principles help streamline design decisions by narrowing the scope of alternatives and focusing on practical, user-centered outcomes. The most recognized framework is Jakob Nielsen’s 10 Usability Heuristics (1994), which includes: visibility of system status, match between system and the real world, user control and freedom, consistency and standards, error prevention, recognition rather than recall, flexibility and efficiency of use, aesthetics and minimalist design, helping users recognize, diagnose and recover from errors, help and documentation [54].

3.2. Criteria

Usability criteria are specific, measurable standards used to evaluate whether a user interface aligns with established usability principles. In the context of website usability, these criteria are essential; however, no single standardized set exists. Researchers have proposed various dimensions with differing scopes and levels of precision [55]. For example, Singh et al. [56] assessed website usability across six core criteria—user satisfaction, attractiveness, simplicity, speed, efficiency, search functionality, and product information —each with its own sub-criteria. User satisfaction measures overall service and product quality; simplicity reflects how intuitive operations are; attractiveness assesses visual appeal and perceived value; speed tracks page-load times; efficiency evaluates task success rates; search functionality measures the relevance and speed of product lookups; and product information ensures the accuracy and completeness of details. In a broader study, Ilbahar and Çebi [57] identified twenty-two e-commerce evaluation criteria, including comparison tools, live support, guest reviews, guest checkout, secure payment, high-resolution images with zoom, multilingual shopping, diverse payment options, detailed delivery information, social login integration, and order tracking features. While these studies highlight the diversity of usability criteria, they collectively underscore the importance of employing multiple measures for accurate assessment [58]. This multifaceted approach ensures a comprehensive evaluation of user experience, balancing technical performance (e.g., page speed) with user-centric design elements (e.g., intuitive navigation).

4. Proposed Multimodal Framework for Website Usability Evaluation

Figure 1 illustrates the end-to-end workflow of the proposed multimodal framework for predicting website usability. The process begins with data collection, where numerical usability indicators (e.g., load time, customer feedback scores) and visual data (full-page screenshots) are extracted. This is followed by a data labeling stage that assigns reliable usability class labels by integrating numerical and visual grading with expert review. During preprocessing, numerical features are encoded and normalized, while images are resized and standardized to ensure consistency. The prepared modalities are then input to the multimodal training phase, where three fusion strategies—early, late, and cross-modal fusion—are implemented using deep learning backbones for visual feature extraction. The system ultimately outputs a predicted usability class, which is evaluated using standard performance metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score.

Figure 1.

End-to-End Workflow of the Proposed Usability Evaluation Model.

5. Dataset

5.1. Define Usability Criteria

Ten automatically extractable usability criteria, derived directly from website structure and source code, were adopted. Collectively, they represent the core pillars of website usability: efficiency, accessibility, effectiveness, and user satisfaction. A detailed description of each criterion and its relevance is provided below:

- Load Time: The time required for a webpage to load completely. Shorter load times improve efficiency and user satisfaction by reducing wait times, maintaining engagement, and enhancing perceived performance.

- Mobile Compatibility: How well a website adapts its layout and functionality for mobile devices. Responsive design increases accessibility and ease of use, ensuring a consistent experience across all devices.

- Image Quality: The clarity, resolution, and optimization of visual elements. High-quality, properly optimized images strengthen aesthetic appeal, build trust, and improve user engagement, whereas poor images degrade the overall experience and efficiency.

- Contact Information: The availability and visibility of communication details such as emails, phone numbers, or social links. Clear contact options foster trust, provide user support, and align with the help and documentation heuristic.

- Customer Feedback Mechanisms: Interactive features (e.g., forms, surveys, live chat) that allow users to share opinions or report issues. These promote transparency, increase engagement, and enable continuous improvement, thereby reinforcing user satisfaction and responsiveness.

- Product Rating Systems: User-generated evaluations or reviews of products and services. These systems enhance decision making confidence and trust, supporting the match between the system and real-world expectations.

- Sorting Functionalities: Tools that allow users to filter or organize content by relevance, price, or popularity. Effective sorting improves navigation efficiency and user control by reducing cognitive effort during information exploration.

- Multilingual Support: The ability to present content in multiple languages, either by user selection or auto-detection. This ensures inclusivity and broad accessibility, facilitating positive experiences for a global audience and enhancing site credibility.

- Payment Options: The variety and security of available transaction methods. Multiple secure payment gateways enhance user flexibility, build trust, and ensure task completion, directly impacting satisfaction and overall usability.

- Website Screenshot: A visual capture of the entire webpage’s layout and design. Screenshots provide a basis for assessing aesthetic consistency, layout clarity, and visual comfort.

5.2. Data Screening and Collection

A multi-stage data curation protocol was implemented to construct a representative and unbiased dataset for fashion e-commerce usability assessment. Websites were sourced from two industry-leading ranking platforms: Similarweb [59] (“Top Fashion & Apparel Websites”) and Semrush [60] (“Most Visited Apparel & Fashion Websites”). These globally recognized sources provide listings ranked by objective traffic metrics—such as monthly visits and engagement—offering a robust foundation of commercially relevant platforms. The screening protocol was applied as follows:

- Initial Filtering: Websites were required to meet two criteria:

- -

- Be publicly accessible and fully transactional (support online purchases).

- -

- Be primarily focused on selling fashion apparel, accessories, or footwear.

- Stratification for Representativeness: Qualifying websites were stratified along two key dimensions to ensure a balanced sample:

- -

- Geographic Distribution: Categorized into major e-commerce markets: North America, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia.

- -

- Commercial Scale: Classified into three traffic tiers: High (>5 million monthly visits), Mid (0.5–5 million), and Low (<0.5 million).

- Usability Coverage: To guarantee coverage across the usability spectrum, the final selection was informed by the Baymard Institute UX Benchmark [61] and a brief expert heuristic review.

Following this screening process, the final curated dataset comprises 546 fashion e-commerce websites

5.3. Mutimodal Usability Criteria Extraction

To ensure accurate, scalable, and automated multimodal usability evaluation, nine numerical features representing key usability criteria were extracted using modern automated tools compatible with static, dynamic, and client-rendered websites. Simultaneously, full-page screenshots were captured to provide visual data, resulting in a multimodal dataset of 546 fashion websites. The extraction methods are detailed below.

5.3.1. Extracting Numerical Modality

Given the diversity of modern website designs—ranging from static server-rendered pages to JavaScript-driven dynamic sites and hybrid SSR frameworks—the data collection pipeline employed headless browser rendering via Puppeteer and standardized APIs to capture fully rendered page states. This approach (summarized in Table 3) enabled robust, consistent, and architecture-independent extraction of nine numerical features:

- Load Time: Measured using the PerformanceNavigationTiming API (capturing FCP, LCP, and DOMContentLoaded events) within Puppeteer sessions to ensure accurate timing across both static sites and single-page applications.

- Mobile Compatibility: Assessed through viewport emulation and computed CSS inspection at standard mobile resolutions to verify responsive layout behavior.

- Image Quality: Evaluated with the Google PageSpeed Insights API and Lighthouse CLI, deriving averaged quality scores (A–F) based on compression efficiency and resolution adequacy.

- Contact Information: Extracted from the rendered DOM by detecting mailto: and tel: links, combined with regex-based pattern matching for contact-related keywords.

- Feedback Mechanisms: Identified through DOM analysis of interactive forms and network interception of asynchronous feedback endpoints.

- Product Ratings: Retrieved from JSON-LD structured data (AggregateRating schema) and visual star indicators, with validation via the Google Rich Results API.

- Sorting Functionalities: Detected by locating interface elements containing sort-related keywords (“sort,” “order,” “filter”) and confirming functionality through event listener analysis.

- Multilingual Support: Verified through <html lang> and <link hreflang> attributes, supplemented by detection of language-switcher UI components.

- Payment Options: Identified by analyzing checkout page DOM structures and monitoring network calls to payment gateways such as PayPal, Stripe, and Apple Pay.

Table 3.

Summary of Extraction Methods for Website Numerical Features.

Table 3.

Summary of Extraction Methods for Website Numerical Features.

| Feature | Extraction Method |

|---|---|

| Load Time | PerformanceNavigationTiming API (FCP, LCP) via Puppeteer |

| Mobile Interface Compatibility | Headless browser viewport emulation with computed CSS inspection |

| Image Quality | Google PageSpeed Insights API and Lighthouse CLI |

| Contact Information | Rendered DOM parsing with keyword and regex-based extraction |

| Customer Feedback Mechanisms | Rendered form detection and network endpoint tracing |

| Product Rating Systems | JSON-LD parsing and visual star detection validated via Rich Results API |

| Sorting Functionalities | Event listener inspection and DOM interaction tracking |

| Multilingual Support | <html lang> and <hreflang> metadata and navigation switcher detection |

| Payment Options | DOM and network request inspection for embedded payment gateways |

5.3.2. Extracting Visual Modality

To capture comprehensive visual representations of each website, full-page screenshots were automatically generated using Selenium WebDriver in headless mode. This setup was augmented with Playwright and the Chrome DevTools Protocol to enhance rendering accuracy and automation reliability. The configuration ensured complete rendering of entire webpages—including dynamically loaded content and below-the-fold elements—for subsequent analysis. All screenshots were captured in a controlled environment with fixed viewport dimensions and standardized rendering settings, producing consistent, high-quality, and reproducible visual data across all samples.

5.4. Data Labeling

Each website was assigned one of five usability grades—Excellent, Very Good, Good, Bad, or Very Bad—through the following multi-step procedure:

- Numerical Modality Labeling

A K-means clustering algorithm with five clusters was applied to the nine numerical usability metrics. The resulting clusters were mapped to the five usability grades based on the relative importance of the underlying features.

- b.

- Visual Modality Labeling

The WebScore AI tool was used to assign a visual usability score (1–10) with corresponding color-coded ratings. These scores were mapped to the five-grade scale as follows: 3.60–4.59 (Very Bad), 4.60–5.59 (Bad), 5.60–7.00 (Good), 7.01–8.59 (Very Good), and 8.60–10 (Excellent). Scores below 3.60 were excluded due to website inaccessibility.

- c.

- Grade Aggregation

The final usability grade for each website was computed as the average of the numerical and visual modality grades, ensuring a balanced assessment that incorporated both data types.

- d.

- Expert Review and Validation

To ensure labeling accuracy and consistency, domain experts in human–computer interaction (HCI) and web usability independently reviewed the initial labels:

- Experts assessed a representative subset of websites across all five usability categories.

- For each website, experts evaluated the numerical label, visual label, and aggregated final grade.

- Majority voting was applied when experts disagreed (agreement of ≥2 experts).

- Full disagreement cases (three different labels) were resolved through consensus discussions.

- The final agreed-upon labels served as ground truth for model training and evaluation.

- e.

- Inter-Rater Agreement

Expert consensus was quantified using Cohen’s kappa (κ):

where represents observed agreement proportion and represents expected chance agreement.

The resulting κ value of 0.85 indicates strong inter-rater agreement (κ > 0.80), validating the reliability of the labeling methodology for training and evaluating the deep learning models.

5.5. Data Preprocessing

The collected data underwent comprehensive preprocessing to ensure compatibility with the deep learning models:

- Numerical Data Processing

- Encoding: Categorical features—including mobile compatibility, image quality, contact information, feedback mechanisms, product ratings, sorting functionality, multilingual support, and payment options—were converted to numerical representations using LabelEncoder.

- Normalization: All numerical features were standardized using StandardScaler to address varying measurement scales and ensure balanced contribution during model training.

- Image Data Processing

- Resizing: All website screenshots were uniformly resized to 224 × 224 pixels to maintain dimensional consistency across samples.

- Color Conversion: Images were converted to RGB format to ensure proper channel representation.

- Normalization: Pixel values were scaled to the [0, 1] range by dividing by 255, improving numerical stability during training.

6. Multimodal Model Training

This study evaluates three primary fusion strategies within a multimodal learning framework:

Early Fusion (Feature-Level): Integrates modalities by concatenating raw or preprocessed features into a unified input vector. This enables direct learning of cross-modal interactions but increases computational complexity and sensitivity to data quality issues.

Late Fusion (Decision-Level): Processes each modality through separate models and combines predictions at the final stage. This approach preserves modality-specific patterns, supports parallel training, and tolerates imperfect data alignment, but may overlook subtle cross-modal relationships.

Cross-Modal Fusion (Interaction-Level): Enables dynamic, bidirectional interaction through attention mechanisms and gating operations at intermediate layers. This captures complex, non-linear dependencies between modalities and dynamically weights their importance, though it requires more sophisticated architecture design and regularization to prevent overfitting.

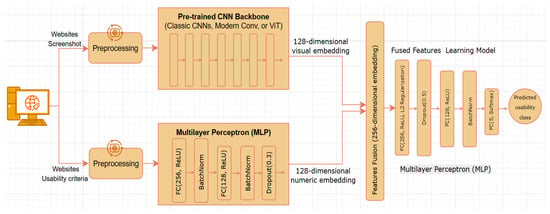

6.1. Early Fusion Training

The early fusion model was trained end-to-end using 80% of the visual-numerical sample pairs. Figure 2 illustrates the complete training framework, with the procedural details outlined below.

Figure 2.

Overview of the Early Fusion Training Framework.

- Feature ExtractionVisual Features: Full-page screenshots were processed using pretrained backbone architectures from three categories:

- -

- Classic CNNs: ResNet152, EfficientNet-B0, DenseNet201, InceptionV3, MobileNetV2, VGG16.

- -

- Modern ConvNets: ConvNeXt-Tiny/Base variants.

- -

- Vision Transformers: ViT-B/16 and Swin-Base.

All backbones were initialized with publicly available weights and fine-tuned on screenshot data. For CNN-style architectures, the classification head was replaced with global average pooling to generate spatially aggregated features. Transformer models used either CLS tokens or averaged patch embeddings. The resulting features were projected through a lightweight head (256 → 128 dimensions) with ReLU, Batch Normalization, and dropout.

Numerical Features: The nine standardized usability indicators were processed through an identical projection head (256 → 128 dimensions) to produce comparable embeddings.

Embedding-dimension Optimization: An ablation study comparing 64, 128, and 256-dimensional embeddings determined that 128 dimensions provided the optimal balance between predictive performance and computational efficiency.

- 2.

- Features Fusion (Concatenation)

The 128-dimensional visual and numerical embeddings were concatenated into a unified 256-dimensional vector, then normalized using Batch Normalization to stabilize distributions and accelerate convergence.

- 3.

- Fusion Learning Model

The combined features were processed by a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) with ReLU activations, L2 regularization, dropout, and batch normalization, mapping to a five-class softmax output representing usability grades. Hyperparameter optimization via systematic ablation identified the optimal configuration summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Early Fusion MLP Model Hyperparameter Optimization Summary.

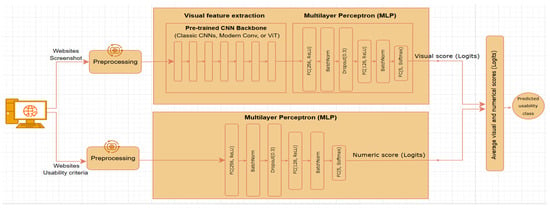

6.2. Late Fusion Training

The late fusion model was trained end-to-end using 80% of the visual-numerical paired samples, following the sequential procedure illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Overview of the Late Fusion Model Training Framework.

- Visual Modality Training

The visual processing pipeline transforms full-page screenshots into predictive logits through two stages:

Feature Extraction: Screenshots are processed through pretrained backbone architectures, with resulting feature maps condensed via global average pooling into fixed-length vectors. Ten state-of-the-art architectures were benchmarked, including six CNNs (ResNet152, EfficientNet-B0, DenseNet201, MobileNetV2, InceptionV3, VGG16) and four transformer-based models (ViT-B/16, Swin-Base, ConvNeXt-Base, ConvNeXt-Tiny), following the methodology established in early fusion experiments.

Scoring: The pooled visual features are processed through a light projection MLP (Dense 256 → ReLU → BatchNorm → Dropout 0.3 → Dense 128 → ReLU → BatchNorm) to generate visual logits representing unnormalized scores for the five usability classes.

- 2.

- Numerical Modality Training

The nine standardized numerical indicators are processed through a parallel MLP with identical architecture (Dense 256 → ReLU → BatchNorm → Dropout 0.3 → Dense 128 → ReLU → BatchNorm) to produce numerical logits.

An ablation study optimized six key hyperparameters for both visual and numerical LP components, with the resulting optimal configurations summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Late Fusion MLP Model Hyperparameter Optimization Summary.

- 3.

- Modality Fusion and Prediction

The five-dimensional visual and numerical logit vectors are combined using element-wise averaging to produce fused logits. These are converted to probabilities via softmax, with the final usability grade determined by the highest probability class.

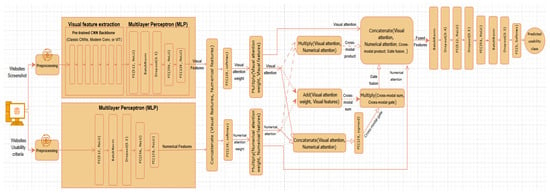

6.3. Cross-Modal Fusion Training

The cross-modal fusion model was trained end-to-end using the same dataset as the early and late fusion experiments. This method moves beyond simple feature concatenation or decision averaging by explicitly modeling bidirectional interactions between visual and numerical modalities. It implements a sophisticated cross-modal interaction pipeline, as illustrated in Figure 4 and detailed in the following outline.

Figure 4.

Overview of the Cross-Modal Fusion Model Training Framework.

- Modality-Specific Feature Processing:

Visual Branch: Full-page screenshots are encoded using a selected pretrained backbone (from ResNet152, EfficientNet-B0, DenseNet201, InceptionV3, MobileNetV2, VGG16, ConvNeXt-Tiny/Base, ViT-B/16, or Swin-Base). The backbone’s pooled output undergoes processing through an image processor MLP head (Dense 256 → BatchNorm → Dropout 0.3 → Dense 128 → GaussianNoise 0.1) to generate a 128-dimensional image embedding.

Numerical Branch: The nine standardized numerical indicators are processed through a structurally identical MLP, projecting them into a corresponding 128-dimensional embedding space.

- 2.

- Cross-Modal Interaction and Fusion:

The core innovation involves dynamic, attention-driven fusion of the two modality embeddings:

Feature Alignment: Both 128-dimensional embeddings are first aligned to ensure dimensional compatibility.

Cross-Modal Attention: Dual attention mechanisms enable:

- ▪

- Visual features to attend to relevant numerical features.

- ▪

- Numerical features to attend to complementary visual patterns.

Multi-Modal Fusion Operations: Attended features are combined through:

- ▪

- Multiplicative Fusion (Hadamard product) to capture feature co-activations.

- ▪

- Additive Fusion to combine feature magnitudes.

- ▪

- Gated fusion to dynamically regulate inter-modal information flow.

Concatenation: Outputs from all fusion operations are concatenated, then batch-normalized and regularized with dropout to form the final fused representation.

- 3.

- Joint Decision Making:

The enriched cross-modal representation is processed through a final MLP classifier (Dense 512 → Dropout 0.5 → Dense 256 → BatchNorm → Dropout 0.3 → L2 regularization → Dense 5 → softmax) to predict the final usability grade.

To optimize the model architecture, a controlled ablation study was conducted on the Cross-Modal Fusion MLPs using stratified cross-validation, with the resulting optimal configurations summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Cross-Modal Fusion MLP Hyperparameter Optimization Summary.

7. Model Evaluation and Evaluation Metrics

Both multimodal frameworks (early and late fusion) were evaluated on a held-out test set comprising 20% of the visual-numerical paired samples. The hold-out strategy was adopted to provide an unbiased estimate of model generalization while preventing data leakage between training and testing phases. This approach is particularly important for multimodal usability assessment, where strong correlations may exist between visual features (e.g., layout balance, color harmony) and numerical attributes (e.g., load time, usability scores). To maintain representativeness, the test set was stratified to preserve the original class distribution across usability categories.

Model performance was assessed using classification reports and confusion matrices, with accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score as primary evaluation metrics. These established measures collectively capture different aspects of classification performance: accuracy indicates overall correctness, precision and recall evaluate class-specific discriminative power, and the F1-score provides a balanced measure of both. Together, they offer a comprehensive assessment of each fusion framework’s predictive effectiveness, robustness, and practical utility.

Accuracy: The proportion of correct predictions (true positives and true negatives) out of the total number of predictions.

where TP is True Positive, TN is True Negative, FP is False Positive, and FN is False Negative.

Precision: The proportion of positive predictions that were correctly identified (true positives) out of all positive predictions made by the model.

where TP is True Positive, and FP is False Positive.

Recall (Sensitivity): The proportion of actual positive cases correctly identified (true positives) out of the total number of actual positive cases.

where TP is True Positive, and FN is False Negative.

F1-Score: A harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balanced measure of a model’s performance, particularly useful when dealing with imbalanced datasets.

8. Experimental Results

All experiments were conducted using Python 3.10 in a Google Colab Pro+ environment, providing a stable, GPU-accelerated computational setup. The implementation utilized TensorFlow 2.19.0 with Keras for model development, Scikit-learn 1.3.0 for data preprocessing and evaluation, NumPy 2.3.0 and Pandas 2.3.0 for numerical operations and data manipulation, and OpenCV with Pillow 11.3.0 for image processing tasks.

8.1. Early Fusion Performance

Early fusion integrates visual and numerical inputs at the feature level, enabling the model to learn joint representations from concatenated embeddings. As shown in Table 7, early fusion models achieve strong predictive performance across backbone architectures, with a clear performance gap between modern and traditional designs. ConvNeXt-Base attains the highest accuracy (0.90), followed closely by ViT-B/16 and Swin-Base (both 0.89). EfficientNet-B0 (0.88) and ConvNeXt-Tiny (0.87) also deliver competitive results, while classic CNNs—DenseNet201 (0.84), ResNet152 (0.80), and VGG16 (0.70)—demonstrate lower performance. The 20 percentage point accuracy difference between the best and worst performers represents a 28.6% relative improvement, indicating that modern architectural advances substantially enhance feature-level multimodal integration.

Table 7.

Comparative performance of visual backbones in Early-fusion framework.

8.2. Late Fusion Performance

Late fusion processes each modality through separate branches and merges their outputs at the decision stage, prioritizing modularity and computational efficiency. As shown in Table 8, this approach is computationally efficient but achieves consistently lower predictive performance compared to early and cross-modal fusion. Performance across backbones shows a compressed range, with the top model (ConvNeXt-Tiny, Accuracy = 0.80, F1 = 0.75) substantially underperforming relative to its early and cross-modal counterparts. Modern architectures maintain a modest advantage, with ConvNeXt-Base and ViT-B/16 (both 0.78 accuracy) following the leading performer. Traditional CNNs exhibit significant performance degradation, with DenseNet201 (0.64), InceptionV3 (0.63), VGG16 (0.58), and MobileNet (0.50) forming the lower performance tier. Since cross-modal interactions are deferred until after unimodal decisions are formed, the late fusion mechanism cannot fully leverage rich feature representations, thereby limiting the benefits of more powerful visual backbones. Consequently, late fusion is most appropriate for scenarios that prioritize modular design, reuse of existing unimodal models, and computational economy over maximum accuracy.

Table 8.

Comparative performance of visual backbones in late-fusion framework.

8.3. Cross-Modal Fusion Performance

Cross-modal fusion explicitly models bidirectional interactions between visual and numerical modalities through cross-attention, multiplicative interactions, and gated fusion. This approach enables the network to learn complex relationships between visual elements (e.g., product layouts, hero images) and numerical usability indicators (e.g., load time, mobile compatibility), establishing it as the most effective fusion paradigm. As detailed in Table 9, cross-modal fusion achieves peak performance across all backbone architectures. ConvNeXt-Base attains the highest accuracy (0.92) with balanced precision (0.90) and recall (0.91), followed closely by ViT-B/16 and Swin-Base (both 0.91 accuracy). ConvNeXt-Tiny delivers competitive performance (0.90 accuracy) while maintaining computational efficiency, while EfficientNet-B0 and DenseNet201 reach 0.89 accuracy. Traditional CNNs show substantial improvement through interaction-level fusion, with ResNet152 and InceptionV3 achieving 0.88 accuracy, and VGG16 and MobileNetV2 reaching 0.85 and 0.84 accuracy, respectively.

Table 9.

Comparative performance of visual backbones in cross-modal fusion framework.

Cross-modal fusion consistently improves accuracy and F1-score by approximately 1–3 percentage points compared to early fusion, and substantially outperforms late fusion across all backbones. The narrow performance range among top models (0.90–0.92) suggests that cross-modal mechanisms drive performance toward an optimal ceiling, particularly for modern architectures. These results demonstrate strong synergy between advanced visual backbones and interaction-aware fusion. Modern architectures like ConvNeXt and transformers (ViT, Swin) generate rich, globally aware visual embeddings that, when combined with cross-attention, enable precise alignment between visual elements and numerical indicators. While traditional CNNs also benefit from cross-modal fusion, their more locally constrained representations limit gains relative to newer architectures. Overall, these findings establish cross-modal fusion with ConvNeXt as the optimal configuration for high-accuracy multimodal usability assessment.

8.4. Computational Efficiency Analysis

Experimental results reveal significant accuracy-efficiency trade-offs across fusion strategies (Table 10). Late Fusion emerges as the most computationally efficient approach, with MobileNet completing training in 25 min (inference: 2.4 ms) but sacrificing substantial accuracy (as low as 0.50). Cross-Modal Fusion achieves peak accuracy (up to 0.92 with ConvNeXt-Base) but requires the heaviest computational investment, with training times exceeding two hours and slower inference speeds. Early Fusion occupies a practical middle ground, where models like EfficientNet-B0 and ConvNeXt-Tiny deliver strong accuracy (0.88–0.90) with moderate computational demands (approximately 1 h training, 4 ms inference).

Table 10.

Comparative computational efficiency across fusion strategies and visual backbone.

The analysis yields clear architectural recommendations based on accuracy-efficiency trade-offs. For applications demanding maximum accuracy, Cross-Modal Fusion with ConvNeXt-Base is optimal when computational resources permit. Early Fusion with EfficientNet-B0 provides a cost-effective alternative for resource-constrained environments requiring strong performance. Late Fusion configurations with MobileNet or EfficientNet suit high-throughput scenarios where approximate usability estimates suffice. Notably, Cross-Modal Fusion with ConvNeXt-Tiny emerges as the most balanced solution, delivering near-state-of-the-art accuracy (0.90) with moderate computational requirements, making it recommended for most practical deployment scenarios.

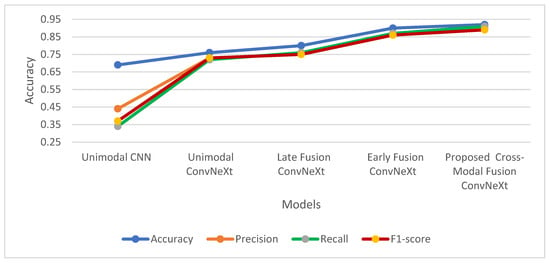

8.5. Comparative Performance Analysis of the Proposed Cross-Modal ConvNeXt Against Baselines

The comparative analysis demonstrates the significant performance advantage of the proposed cross-modal fusion approach (Table 11 and Figure 5), which achieves state-of-the-art results with 0.92 accuracy and 0.89 F1-score. The proposed method substantially outperforms all baseline models, including a unimodal benchmark from literature (accuracy: 0.69) [14], a modern unimodal ConvNeXt implementation (accuracy: 0.76), and simpler fusion strategies such as late fusion (accuracy: 0.80) and early fusion (accuracy: 0.90). This progressive performance improvement validates the core premise that deep, bidirectional interactions between visual and numeric modalities—enabled by cross-modal fusion with a modern backbone—are essential for robust website usability assessment. The proposed model achieves balanced precision (0.90) and recall (0.91), confirming its suitability for reliable real-world deployment.

Table 11.

Comparative Performance of Proposed Cross-modal ConvNeXt versus Baselines.

Figure 5.

Performance Evolution from Baselines to Proposed Cross-modal ConvNeXt.

8.6. Detailed Analysis of the Proposed Cross-Modal ConvNeXt

To validate the robustness and practical utility of the proposed Cross-Modal ConvNeXt model, a comprehensive evaluation was conducted assessing both its predictive performance and training behavior.

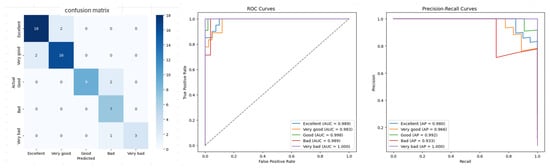

The results (Figure 6) demonstrate excellent discrimination capability across all usability grades. One-versus-rest ROC curves consistently yield AUCs ≥ 0.98 for all usability classes, while precision-recall curves maintain Average Precision ≥ 0.93 throughout. The confusion matrix reveals clear diagonal concentration, with errors occurring primarily between adjacent grades—indicating strong class separation with minimal confusion at naturally ambiguous boundaries. Collectively, these findings confirm robust discriminatory power, reliable calibration across the entire label spectrum, and practical viability for real-world deployment.

Figure 6.

Multiclass evaluation of the Cross-Modal ConvNeXt model, showing the confusion matrix (left), ROC curves (middle), and precision-recall curves (right).

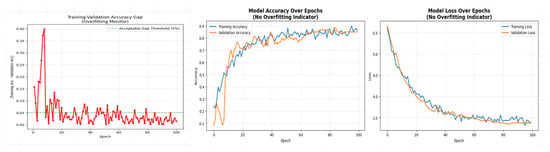

The training dynamics further support these findings (Figure 7). Training and validation accuracy improve steadily, plateauing after approximately 60–80 epochs, while training and validation losses decline correspondingly. The final generalization gap remains below 5%, indicating stable convergence with minimal overfitting and confirming that the cross-modal architecture is well-suited to the task.

Figure 7.

Model learning curves showing the convergence of accuracy and loss.

9. Model Interpretability with XAI Analysis

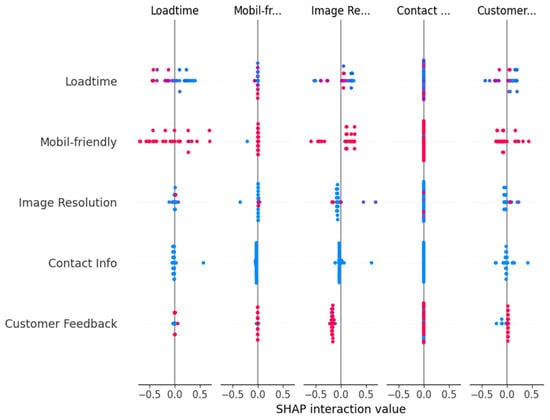

To validate and interpret the proposed ConvNeXt-Base Cross-Modal model, Explainable AI (XAI) techniques—specifically SHAP and LIME—were employed. SHAP provides global insights by ranking feature importance and revealing interactions across the entire dataset, while LIME offers localized, case-specific explanations. Together, these complementary approaches enable comprehensive model interpretation at both dataset and instance levels.

The SHAP interaction analysis (Figure 8) reveals how pairs of usability indicators jointly influence predictions. Key findings include: (i) fast load time combined with strong mobile support or comprehensive customer feedback significantly enhances predicted usability; (ii) the interaction between image resolution and load time confirms that high-resolution imagery is beneficial only when it does not degrade performance, demonstrating the model’s understanding of critical usability trade-offs; and (iii) contact information and customer feedback mutually reinforce each other, indicating that sites providing multiple communication channels are perceived as more usable. This analysis confirms that the model bases its decisions on logical feature combinations rather than isolated metrics.

Figure 8.

SHAP interaction values for the ConvNeXt-Base Cross-Modal model.

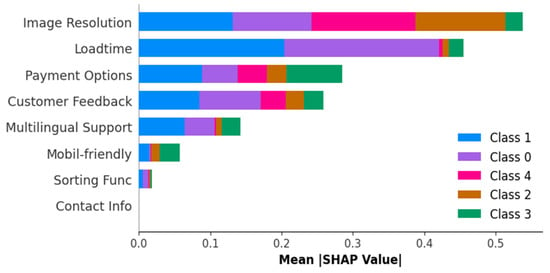

The mean absolute SHAP values (Figure 9) rank overall feature contributions, showing that image resolution and load time dominate as the most critical factors. A secondary tier comprising payment options and customer feedback also contributes substantially, while multilingual support has moderate impact. Mobile compatibility, sorting functionality, and contact information play supporting roles. The consistent importance patterns across all usability classes, visualized through stacked bars, confirm the model’s stable and rational focus on core usability principles.

Figure 9.

Mean absolute SHAP values for the ConvNeXt-Base Cross-Modal model.

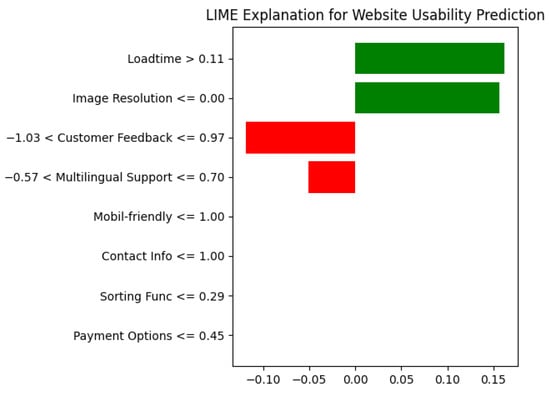

The LIME explanation (Figure 10) provides localized interpretation for a specific website prediction, aligning with the global SHAP analysis. For this instance, load time and image resolution were the strongest positive contributors, while poor customer feedback and limited multilingual support were the primary negative factors. This consistency between global (SHAP) and local (LIME) explanations demonstrates that the model’s decision making remains both stable across the dataset and transparent for individual cases.

Figure 10.

LIME explanation for a sample prediction.

10. Discussion of Findings

This study demonstrates that effective multimodal website usability assessment hinges on two critical design choices: (i) the method of modality fusion and (ii) the selection of the visual backbone. Experimental results reveal empirically consistent performance patterns, offering valuable guidance for both research and practical implementation in automated usability evaluation.

10.1. Performance Hierarchy Across Fusion Strategies

Under identical evaluation protocols, a clear performance hierarchy emerges: Unimodal < Late Fusion < Early Fusion < Cross-Modal Fusion. Cross-modal fusion achieves the strongest results, with a peak accuracy of 0.92 and an F1-score of 0.89 when using the ConvNeXt-Base backbone. This outcome validates the hypothesis that interaction-level fusion more effectively captures the complex dependencies between visual layout cues and quantitative usability indicators compared to simpler feature concatenation or decision averaging.

10.2. Visual Backbones: Mechanistic Interpretation of Results

Performance differences across backbones reflect their distinct architectural characteristics. ConvNeXt’s modern convolutional design—featuring larger kernels and stage-wise scaling—effectively captures both semantic content (e.g., hero images, product grids) and layout structure (e.g., navigation bars, spacing). This enables rich representations of fine visual details alongside global page composition, yielding top performance across all fusion strategies. Vision Transformers (ViT, Swin) achieve competitive results through self-attention mechanisms that model long-range spatial relationships between disparate page regions (menus, content areas, footers). This capability is particularly well-suited to the structured, multi-section nature of web interfaces. EfficientNet, despite being a more traditional CNN, benefits from compound scaling that preserves fine texture details while maintaining adequate contextual receptive fields. In contrast, older CNNs such as VGG and ResNet tend to focus on local or mid-level patterns. Their architectures are less effective at jointly representing high-resolution imagery and complex multi-section layouts, which explains their comparatively lower performance.

10.3. Performance-Efficiency Trade-Offs

Late fusion offers the lowest training and inference cost but compromises on accuracy, with its best performance reaching approximately 0.80. Cross-modal fusion achieves the highest metrics at a greater computational expense; ConvNeXt-Base maximizes accuracy, while ConvNeXt-Tiny offers a favorable accuracy–efficiency trade-off, delivering near-top-tier scores with approximately one hour of training and 4–5 ms inference times. Early fusion provides a balanced middle ground; EfficientNet-B0 attains solid accuracy (≈0.88) with modest runtime, making it suitable for resource-constrained environments that still require high-quality results.

10.4. Explainable AI Validation

Explainability analyses confirm that the model’s decisions align with established usability principles. SHAP analysis identifies image resolution and load time as the dominant predictors, followed by payment options and customer feedback. It also reveals meaningful feature interactions, such as the benefit of high-resolution imagery when it does not compromise page load speed. LIME provides instance-level justifications that corroborate these global SHAP patterns. This transparency elevates the model from a black-box classifier to a practical diagnostic tool, enabling targeted usability improvements.

10.5. Theoretical and Practical Implications

Theoretically, these findings demonstrate that bidirectional cross-modal interaction between visual and numerical features significantly enhances representational learning for usability assessment. This supports the view that usability is best modeled through joint representation learning rather than through the analysis of individual modalities in isolation.

Practically, this framework offers an adaptable, data-driven approach to website usability evaluation. With minimal fine-tuning on domain-specific datasets that combine visual and performance indicators, it can be deployed across diverse sectors—including e-commerce, education, and government. This capability enables the proactive identification of usability bottlenecks and the optimization of design decisions without sole reliance on manual expert reviews or costly user testing.

11. Conclusions

As digital platforms become increasingly central, scalable and data-driven, usability assessment is now essential. This study presented a numeric–visual multimodal deep learning framework for the automated evaluation of fashion e-commerce websites. The model was trained on a dataset of 546 sites using an 80/20 train/test split with stratified cross-validation and controlled ablations. Visual features were extracted using a comprehensive benchmark of backbones—including classic CNNs (ResNet152, EfficientNet-B0, DenseNet201, InceptionV3, MobileNetV2, VGG16), modern ConvNets (ConvNeXt-Tiny/Base), and vision transformers (ViT-B/16, Swin-Base). Three fusion strategies (Early, Late, and Cross-Modal) were systematically compared under identical training protocols.

Cross-Modal Fusion, which implements bidirectional attention, multiplicative interactions, and gated fusion, produced the most discriminative joint representations. When paired with the ConvNeXt-Base backbone, this combination achieved the highest performance across all evaluated metrics (accuracy = 0.92, F1-score = 0.89). Model decisions were rendered interpretable using SHAP and LIME, which quantified the influence of key usability indicators and provided instance-level justifications for actionable insights.

The framework’s architecture captures generalizable usability patterns and is readily adaptable to new domains such as e-learning and hospitality. This requires only light fine-tuning on domain-specific data rather than full retraining. Overall, this work provides a robust, explainable, and scalable alternative to traditional unimodal methods, establishing a practical foundation for continuous, data-driven usability optimization.

12. Limitations and Challenges

- The dataset is relatively limited in size, comprising 546 fashion e-commerce websites.

- The framework’s current focus on fashion e-commerce restricts its direct applicability to other sectors without domain-specific fine-tuning.

- Training the multimodal framework—particularly the cross-modal fusion component with modern backbones—is computationally intensive and time-consuming.

- Full-page screenshots capture only static page states, potentially missing interaction-driven or personalized behaviors (e.g., dynamic menus, A/B testing variants).

13. Future Work

- Validate and fine-tune the framework using larger, more diverse datasets, extending evaluation to additional domains to assess cross-domain applicability.

- Enrich multimodal input by incorporating user-interaction data (clickstreams, scroll depth, session duration) and textual feedback (e.g., reviews, search queries) to capture a broader range of usability factors.

- Improve computational efficiency by exploring lightweight or distilled architectures and parameter-efficient fine-tuning methods.

- Optimize the screenshot capture and processing pipeline to enable near-real-time assessment of dynamic or personalized web pages.

Funding

This work was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, under grant no. (IPP: 1129-612-2025). The author, therefore, acknowledges with thanks DSR for its technical and financial support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges Asmaa Hakami, Raneem Alqarni, and Asmaa Muqaibil [14] for their pivotal role in collecting and organizing the dataset utilized in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Maligat, D.E.; Torio, J.O.; Bigueras, R.T.; Arispe, M.C.; Palaoag, T.D. Web-based knowledge management system for Camarines Norte State College. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 803, 012006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, N.S.; Doğruer, E.; Elosta, A.K.O.; Eraslan, S.; Yeşilada, Y.; Harper, S. EyeCrowdata: Towards a web-based crowdsourcing platform for web-related eye-tracking data. In Proceedings of the ACM Symposium on Eye Tracking Research and Applications (ETRA ’20 Adjunct), Stockholm, Sweden, 11–14 March 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.; Loranger, H. Prioritizing Web Usability; New Riders: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2006; ISBN 9780321350312. [Google Scholar]

- Cappel, J.J.; Huang, Z. A usability analysis of company websites. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2007, 48, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 9241-11:2018; Ergonomics of Human–System Interaction—Part 11: Usability: Definitions and Concepts. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Sivaji, A.; Tsuaan, S.S. Website user experience (UX) testing tool development using open-source software (OSS). In Proceedings of the 2012 Southeast Asian Network of Ergonomics Societies (SEANES), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 3–5 December 2012; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, P.B.; Spaulding, T.; Wells, T.; Moody, G.; Moffitt, K.; Madariaga, S. A theoretical model and empirical results linking website interactivity and usability satisfaction. In Proceedings of the 39th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS ’06), Kauai, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2006; Volume 6, p. 123a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingli, A.; Cassar, S. An intelligent framework for website usability. Adv. Hum. Comput. Interact 2014, 2014, 479286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.A.; Mottay, F.E. A global perspective on website usability. IEEE Softw. 2001, 18, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namoun, A.; Alrehaili, A.; Tufail, A. A review of automated website usability evaluation tools: Research issues and challenges. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science, Proceedings of the Design, User Experience, and Usability: UX Research and Design (HCII 2021), Virtual Event, 24–29 July 2021; Soares, M.M., Rosenzweig, E., Marcus, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 12779, pp. 292–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marenkov, J.; Robal, T.; Kalja, A. Guideliner: A tool to improve web UI development for better usability. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Web Intelligence, Mining and Semantics, Novi Sad, Serbia, 25–27 June 2018; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakaev, M.; Heil, S.; Khvorostov, V.; Gaedke, M. Auto-extraction and integration of metrics for web user interfaces. J. Web Eng. 2018, 17, 561–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Q.; Zheng, X.S.; Sun, T.; Heng, P.A. Webthetics: Quantifying webpage aesthetics with deep learning. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2019, 124, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakami, A.; Alqarni, R.; Muqaibil, A.; Alowidi, N. Intelligent usability evaluation for fashion websites. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.12770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, D.E.; Gil-García, J.R.; Luna-Reyes, L.F.; Sandoval-Almazán, R.; Duarte-Valle, A. Improving the performance assessment of government web portals: A proposal using data envelopment analysis (DEA). Inf. Polity 2013, 18, 169–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Almaghalsah, H. Usability evaluation of e-government websites: A case study from Taiwan. Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 2020, 4, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Das, S. Accessibility and usability analysis of Indian e-government websites. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2020, 19, 949–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csontos, B.; Heckl, I. Accessibility, usability, and security evaluation of Hungarian government websites. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2021, 20, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, M.; Bajwa, I.S.; Ramzan, S.; Afreen, H.; Abdullah, S. A genetic algorithm-based support vector machine approach for intelligent usability assessment of m-learning applications. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2022, 2022, 160975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.N.; Samui, A.; Mukul, M.; Misra, C.; Goswami, B. Usability evaluation of e-learning platforms using UX/UI design and ML techniques. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Advancements in Smart, Secure and Intelligent Computing (ASSIC), Bhubaneswar, India, 27–29 January 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adepoju, S.A.; Oyefolahan, I.O.; Abdullahi, M.B.; Mohammed, A.A. Integrated usability evaluation framework for university websites. i-Manag. J. Inf. Technol. 2019, 8, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adepoju, S.A. Integrated Website Usability Evaluation Model Using Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process and Artificial Neural Network. Ph.D. Thesis, Federal University of Technology Minna Institutional, Minna, Nigeria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jayakody, V.; Atukorale, A. The usability of university websites: A study on Sri Lankan universities. Sri Lankan J. Appl. Sci. 2022, 1, 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulrahman, A.O.; Rawf, K.H. Usability methodologies and data selection: Assessing the usability techniques on educational websites. Int. J. Electron. Commun. Syst. 2022, 2, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakrudeen, M. Evaluation of the accessibility and usability of university websites: A comparative study of the Gulf region. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2025, 24, 1883–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macakoğlu, Ş.S.; Peker, S.; Medeni, İ.T. Accessibility, usability, and security evaluation of universities’ prospective student web pages: A comparative study of Europe, North America, and Oceania. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2023, 22, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqurni, J.S. Evaluating the user interface and usability approaches for e-learning systems. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Web Eng. 2023, 18, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Roy, S.; Sinha, A.; Iwendi, C.; Strážovská, Ľ. E-commerce website usability analysis using association rule mining and machine learning algorithms. Mathematics 2022, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailangkay, A.; Satyabodhi, R.; Halim, E. Analyzing factors influencing adoption of AI in e-commerce UI/UX design using TAM. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Social Sciences and Intelligence Management (SSIM), Taichung, Taiwan, 15–17 December 2023; pp. 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakalejčík, L.; Gavurová, B.; Báčik, R. Website usability and user experience during shopping online from abroad. J. Appl. Econ. Sci. 2018, 13, 1237–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, U.; Yasir, T.; Shakeel, T. Web usability and user experience for Pakistani e-commerce websites. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Innovative Computing (ICIC), Lahore, Pakistan, 9–10 November 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şimşekler, S. The Effects of Service Design on Super-App Brand Perception and User Experience. Master’s Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Shaba, C.D. Development of e-Banking Website Quality Evaluation Model Using Fuzzy Analytic Hierarchy Process. Master’s Thesis, Federal University of Technology Minna Institutional, Minna, Nigeria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Janabi, A.A. Predicting internet banking effectiveness using artificial neural networks. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2021, 12, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawabreh, O.; Jahmani, A.; Maaiah, B.; Basel, A. Evaluation of the contents of the five-star hotel website and customer orientation. Inf. Sci. Lett. 2022, 11, 1077–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biyyapu, V.P.; Jammalamadaka, S.K.R.; Jammalamadaka, S.B.; Chokara, B.; Duvvuri, B.K.K.; Budaraju, R.R. Building an expert system through machine learning for predicting website quality based on its completion. Computers 2023, 12, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghattas, M.M.; Sartawi, P.D.B. Performance evaluation of websites using machine learning. EIMJ 2020, 51, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ghattas, M.M.; Mora, A.M.; Odeh, S. A novel approach for evaluating web page performance based on machine learning and optimization algorithms. AI 2025, 6, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, A.; Giannone, D.; Birardi, V.; Galiano, A.M. An innovative approach for the evaluation of web page impact combining user experience and neural network score. Future Internet 2021, 13, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, J.; Carvalho, D.; Rocha, T.; Barroso, J. Automated evaluation tools for web and mobile accessibility: Proposal of a new adaptive interface tool. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 204, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yao, B.; Gu, H.; Huang, J.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, D. UXAgent: A system for simulating usability testing of web design with LLM agents. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.09407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuric, E.; Demčák, P.; Krajčovič, M. Unmoderated usability studies evolved: Can GPT ask useful follow-up questions? Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2024, 41, 9752–9769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jiang, Y. Aesthetic assessment of website design based on multimodal fusion. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2021, 117, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delitzas, A.; Chatzidimitriou, K.C.; Symeonidis, A.L. Calista: A deep learning-based system for understanding and evaluating website aesthetics. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Stud. 2023, 175, 103019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, G.; Han, X.; Zuo, W.; Liu, W. FusionNet: An effective network phishing website detection framework based on multi-modal fusion. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on High Performance Computing & Communications, Data Science & Systems, Smart City & Dependability in Sensor, Cloud & Big Data Systems & Application (HPCC/DSS/SmartCity/DependSys), Melbourne, Australia, 17–21 December 2023; pp. 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meel, P.; Vishwakarma, D.K. Multi-modal fusion using fine-tuned self-attention and transfer learning for veracity analysis of web information. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 229, 120537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Joshi, M.; Turc, I.R.; Hu, H.; Liu, F.; Eisenschlos, J.M.; Khandelwal, U.; Shaw, P.; Chang, M.W.; Toutanova, K. Pix2Struct: Screenshot parsing as pretraining for visual language understanding. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Honolulu, HI, USA, 3–7 July 2023; pp. 18893–18912. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Chen, L.; Zhao, Z.; Ma, D.; Cao, R.; Zhu, Z.; Yu, K. Hierarchical multimodal pre-training for visually rich webpage understanding. In Proceedings of the 17th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining (WSDM), Merida, Mexico, 4 March 2024; pp. 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baechler, G.; Sunkara, S.; Wang, M.; Zubach, F.; Mansoor, H.; Etter, V.; Cărbune, V.; Lin, J.; Chen, J.; Sharma, A. ScreenAI: A vision-language model for UI and infographics understanding. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Third International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI-24), Jeju, Republic of Korea, 3–9 August 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, J.Y.; Lo, R.; Jang, L.; Duvvur, V.; Lim, M.C.; Huang, P.Y.; Neubig, G.; Zhou, S.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Fried, D. VisualWebArena: Evaluating multimodal agents on realistic visual web tasks. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Bangkok, Thailand, 3 March 2024; Volume 1, pp. 881–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Xin, L.; Xiang, C.; Zhou, T.H.; Ma, J. WebQuality: A large-scale multi-modal web page quality assessment dataset with multiple scoring dimensions. In Proceedings of the 2025 Conference of the Nations of the Americas Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (NAACL-HLT 2025), Volume 1: Long Papers, Albuquerque, NM, USA, 29 April–4 May 2025; pp. 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, E.S.A.; Kamaruddin, N.; Mansor, Z. Adaptation of usability principles in responsive web design technique for e-commerce development. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Informatics (ICEEI), Bali, Indonesia, 10–11 August 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 726–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mvungi, J.; Tossy, T. Usability evaluation methods and principles for the web. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Secur. 2015, 13, 86. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, J. Enhancing the explanatory power of usability heuristics. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI), Boston, MA, USA, 24–28 April 1994; pp. 152–158. [Google Scholar]

- Park, K.S.; Lim, C.H. A structured methodology for comparative evaluation of user interface designs using usability criteria and measures. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 1999, 23, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, T.; Malik, S.; Sarkar, D. E-commerce website quality assessment based on usability. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Computing, Communication and Automation (ICCCA), Greater Noida, India, 29–30 April 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilbahar, E.; Cebi, S. Classification of design parameters for e-commerce websites: A novel fuzzy Kano approach. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 1814–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Venkatesh, V. Assessing a firm’s web presence: A heuristic evaluation procedure for the measurement of usability. Inf. Syst. Res. 2002, 13, 168–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Similarweb Ltd. Similarweb. Available online: https://www.similarweb.com/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Semrush Inc. Semrush. Available online: https://www.semrush.com/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Baymard Institute. Baymard Institute. Available online: https://baymard.com/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).