Abstract

Drawing upon the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) and Trust Transfer Theory, this study investigates how AI digital avatars influence consumer trust and purchase intention. Using survey data collected from 378 valid respondents, the proposed model was tested with Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). The results reveal that brand awareness and perceived quality significantly affect purchase intention through product trust, while social endorsement cues, anthropomorphism, and interaction quality indirectly influence purchase intention through AI Avatar trust. Furthermore, both AI Avatar trust and product trust have significant direct effects on purchase intention, highlighting the critical role of trust in AI-driven persuasion processes. This study validates the dual-route persuasion mechanism of the ELM in AI marketing contexts and extends the application of trust theory to human–AI interactions, offering valuable insights for future research on AI brand endorsement and consumer psychology.

1. Introduction

The rapid advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies has accelerated the application of AI avatars in marketing and consumer interaction. In recent years, marketing scholars have increasingly emphasized the integration of technology and consumer experience, suggesting that future marketing models will rely heavily on the convergence of intelligent agents, anthropomorphic design, and social media platforms [1]. According to anthropomorphism theory [2], consumers tend to project human-like attributes onto digital agents, thereby establishing emotional connections. This phenomenon has been empirically validated in interactions involving social robots and AI-driven avatars [3].

However, the value of AI avatars extends beyond novelty or interactivity—trust is the key factor driving consumer acceptance and adoption. In essence, trust is a multi-dimensional construct encompassing both interpersonal components—such as integrity and competence—and technological components—such as reliability and transparency [4]. When interacting with AI avatars, consumers often transfer interpersonal trust patterns to artificial agents, particularly when avatars exhibit human-like appearances and emotional expressions [2]. Nonetheless, trust in AI avatars arises not only from anthropomorphic cues but also from perceptions of the accuracy, credibility, and ethical transparency of the underlying algorithm [5].

In marketing contexts, trust has long been recognized as a central psychological mechanism influencing consumer attitudes and purchase intentions. Belanche et al. [6] found that influencer credibility significantly enhances followers’ attitudes and behavioral responses, while Marbach et al. [7] showed that virtual influencers and human influencers generate trust through similar processes, positioning trust as a critical mediator of purchase decisions. Trust also mitigates perceived risk and uncertainty, thereby increasing consumers’ willingness to adopt new technologies [8]. Understanding how AI avatars cultivate consumer trust is thus crucial to uncovering their marketing potential.

Furthermore, the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) provides a suitable framework for examining this phenomenon. The central route reflects consumers’ rational evaluation of the AI avatar’s expertise, accuracy, and interaction quality, fostering cognitive trust; the peripheral route operates through social endorsement, brand familiarity, and anthropomorphic design to enhance affective trust [9]. This dual-path trust formation mechanism not only complements models such as TAM [10] and UTAUT [11] but also deepens our understanding of how consumers form purchase intentions under uncertainty.

Despite growing interest in AI and virtual influencer marketing, significant research gaps remain. First, most prior studies rely on TAM, UTAUT, or S-O-R frameworks and rarely incorporate ELM, leading to a limited understanding of trust formation via central and peripheral routes. Second, existing research tends to examine overall trust or technology acceptance rather than investigating how specific AI avatar features—such as anthropomorphism, interaction quality, or social endorsement—shape consumer psychology and behavior [12]. Finally, although industry applications of AI avatars in retail and e-commerce have proliferated, academic studies have yet to fully address their impact on consumer purchase intention, creating a disconnect between theory and practice [7].

In response to these gaps, this study aims to explore how AI avatars influence consumer trust and purchase intention through both central and peripheral routes. By integrating ELM with Trust Theory, this research advances beyond prior reliance on TAM or UTAUT to offer a nuanced analysis of AI-mediated persuasion mechanisms. The study incorporates key constructs—brand awareness, product trust, social endorsement, anthropomorphism, and interaction quality—to empirically examine their effects on consumer trust formation [6,13], thereby contributing both theoretically and practically to the emerging field of AI-driven marketing.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Theoretical Foundation

2.1.1. Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM)

The Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM), proposed by Cacioppo, Petty, Kao, and Rodriguez [9], is a widely adopted theory for explaining persuasion and attitude change. ELM posits that individuals process persuasive messages through two distinct routes: the central route and the peripheral route. The central route occurs when individuals possess both the motivation and cognitive ability to engage in careful evaluation of message quality and logic, leading to deep processing and enduring attitude change. In contrast, the peripheral route is activated when motivation or ability is low; in such cases, individuals rely on superficial cues—such as the attractiveness of a spokesperson, social endorsement, or brand familiarity—resulting in more temporary and fragile attitude shifts.

In recent years, ELM has been extensively applied to digital marketing and online communication contexts. For instance, in online shopping and social media marketing, consumers are simultaneously influenced by central cues (e.g., product information, professional quality of recommendations) and peripheral cues (e.g., number of likes, user reviews) [14,15]. This theoretical foundation provides a valuable lens for understanding the persuasive effects of AI avatars. Specifically, the interaction quality and expertise of AI avatars can be conceptualized as central route cues, requiring cognitive evaluation, while anthropomorphic design, brand awareness, and social endorsement function as peripheral cues, triggering heuristic processing.

2.1.2. Trust Theory and Human–Technology Interaction

Trust has long been recognized in marketing and information systems research as a key factor in reducing uncertainty and facilitating transactions [8]. McKnight, Choudhury, and Kacmar [4] conceptualized trust as a multi-dimensional construct that includes cognitive trust and affective trust. The former is grounded in perceptions of competence and expertise, whereas the latter arises from emotional bonds and interpersonal experiences. When consumers interact with AI avatars, they often transfer interpersonal trust patterns to technological agents—particularly when the avatar exhibits anthropomorphic features [2].

In the context of technology interaction, trust also encompasses judgments about a system’s integrity, transparency, and accuracy [5]. Prior studies have demonstrated that when consumers perceive AI agents as credible and accurate, they are more likely to form favorable attitudes and increase their intention to adopt such systems [6,12]. Thus, trust functions not only as a mediator of attitude change but also as a central psychological mechanism explaining how consumers translate AI avatar interactions into purchase intentions.

Integrating Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) and Trust Theory, this study constructs an analytical framework for understanding AI-driven persuasion. Central-route factors—such as interaction quality and the perceived accuracy of the AI avatar—primarily influence decision-making through cognitive trust. Peripheral-route factors—such as brand awareness, anthropomorphism, and social endorsement—affect consumer attitudes via affective trust. Furthermore, AI avatar trust and product trust jointly form a dual-layered trust structure that ultimately drives consumers’ purchase intentions [7]. Accordingly, this study adopts ELM as the theoretical foundation and incorporates trust theory to propose an integrated model explaining how AI avatars influence consumer purchasing decisions.

2.2. Brand Awareness and Product Trust

Brand awareness is regarded as a composite construct that reflects consumers’ familiarity and cognitive recognition of a brand, and has long been considered an essential market signal that reduces uncertainty [16]. According to Signaling Theory, in information-asymmetric environments, brands act as credible signals by consistently communicating promises of quality and reliability through sustained marketing efforts [17]. As consumers become more familiar with a brand, they are more likely to interpret it as a “reliable signal,” thereby reducing perceived risk and reinforcing trust in the associated products [18].

Recent studies further support this perspective. Foroudi et al. [19] demonstrated a significant positive relationship between brand awareness and brand credibility, which in turn fosters consumer trust and favorable product attitudes. Similarly, Seo and Park [20] confirmed that, in digital retail contexts, well-known brands enhance cognitive trust and reduce uncertainty, thereby increasing purchase intention. These findings indicate that brand awareness functions not merely as a memory cue but as a foundational basis for trust formation in consumers’ decision-making processes.

Moreover, the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) provides a complementary theoretical lens. Petty et al. [21] suggested that when consumers lack the time or motivation to process information deeply, they rely on peripheral cues for decision-making. Brand awareness operates as a familiarity heuristic, allowing consumers to reduce cognitive effort and quickly form perceptions of credibility in low-involvement situations [22]. More recent research in digital marketing and social media contexts indicates that brand familiarity improves message fluency, which in turn strengthens trust in both the brand and its products [23,24]. In other words, brand awareness can exert influence through the peripheral route by generating instant heuristic trust, while also serving as a central cue under high-involvement conditions, prompting deeper product evaluation and reinforcing trust.

In summary, brand awareness plays a pivotal role even in AI avatar recommendation contexts. When consumers perceive that an AI avatar recommends a product from a familiar brand, this signal reduces uncertainty about the recommendation and enhances trust in the promoted product. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1.

Brand awareness has a positive effect on product trust.

2.3. Perceived Quality and Product Trust

Perceived quality refers to consumers’ subjective evaluation of a product’s overall excellence and reliability [25]. According to Cue Utilization Theory, when consumers lack complete product information, they rely on a combination of intrinsic cues (e.g., design, functionality) and extrinsic cues (e.g., brand reputation, price) to infer product quality [26]. In digital marketing contexts—where consumers cannot physically inspect products—perceived quality often serves as a proxy signal, helping to reduce uncertainty and facilitate trust judgments [27].

Signaling Theory offers an additional explanatory foundation. When consumers perceive a product as high-quality, such perception signals a firm’s integrity, competence, and responsibility, thereby strengthening trust in both the brand and the product [17]. Empirical studies consistently support this relationship. Yoo and Donthu [28] found that perceived quality is not only a key source of brand equity but also a determinant of consumer trust. More recent evidence from digital retail research indicates that high perceived quality enhances consumers’ perceptions of product reliability and honesty [29]. Similarly, Ladhari and Tchetgna [30] confirmed a significant positive relationship between perceived quality and customer trust in e-commerce settings.

Further empirical support has emerged from recent studies. Fan et al. [31] revealed that both service quality and perceived quality positively influence consumer trust in social commerce platforms and, by reducing perceived risk, promote continued use intention. Gün and Söyük [32] found in the health insurance industry that perceived quality and customer satisfaction sequentially mediate the relationship between trust and repurchase intention. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that perceived quality not only directly enhances trust but also indirectly shapes behavioral outcomes through risk mitigation and satisfaction mechanisms.

Within the framework of the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM), perceived quality functions as a central-route cue that requires consumers’ active cognitive engagement [21]. When an AI avatar provides information that highlights superior product attributes—such as professional specifications, performance, or durability—consumers are likely to engage in central processing and form cognitive trust grounded in rational evaluation. Therefore, it can be inferred that higher perceived quality increases consumers’ tendency to trust products recommended by AI avatars.

H2.

Perceived quality has a positive effect on product trust.

2.4. Social Endorsement Cues and AI Avatar Trust

Social endorsement cues—such as the number of likes, comments, shares, or followers—are widely regarded as critical external indicators that influence consumers’ judgments and decision-making. According to Social Proof Theory [33], individuals in uncertain situations tend to rely on the behaviors or signals of others as references to reduce decision risks and enhance their sense of trust. In digital marketing contexts, these cues not only serve as indirect evidence that “others have already adopted” but also function as salient peripheral-route signals in consumers’ information processing [21].

Empirical studies have consistently supported this view. Early research by Chevalier and Mayzlin [34] found that both the quantity and valence of online reviews significantly increased consumers’ trust and purchase intentions for books. Similarly, Chen et al. [35] demonstrated that online consumer reviews and word-of-mouth communications act as vital social cues that shape consumer trust in e-retailing environments. More recent studies have examined this phenomenon in the context of digital influencers and AI avatars. Belanche et al. [36] showed that virtual influencers’ credibility and their associated social support signals (e.g., follower count and engagement rate) significantly enhance followers’ attitudes and behavioral responses. Likewise, Lou and Yuan [37] found that visible engagement metrics—such as likes and shares—serve as social endorsements that strengthen users’ trust toward both brands and endorsers.

Synthesizing these theoretical and empirical insights, this study argues that when an AI avatar exhibits strong social endorsement cues, consumers are more likely to trust its recommendations. These cues reduce information asymmetry and reinforce the perceived reliability of the AI avatar as a source of influence.

H3.

Social endorsement cues have a positive effect on AI avatar trust.

2.5. Anthropomorphism and AI Avatar Trust

Anthropomorphism refers to attributing human-like characteristics—such as appearance, language, and emotional expression—to non-human entities, thereby making them appear more human [2]. According to Anthropomorphism Theory, humans tend to project mind and intention onto non-human agents, a psychological mechanism that enhances social presence during interactions and consequently fosters trust toward the agent [38]. In parallel, both Media Richness Theory and Social Presence Theory suggest that when digital agents exhibit greater interactivity and emotional expressiveness, consumers are more likely to perceive them as credible and trustworthy communication partners [39].

Empirical evidence further supports these theoretical perspectives. Qiu and Benbasat [12] found that anthropomorphic design features—such as natural language use and human-like appearance—significantly enhance social presence and trust in recommendation agents within e-commerce environments. Similarly, Eyssel and Kuchenbrandt [40] demonstrated through experiments that robots with higher levels of anthropomorphism evoke stronger social attributions, promoting users’ trust and cooperation intentions. Extending this line of research, Fakhimi et al. [41] reported that humanized voice, conversational competence, and cognitive attributes significantly enhance users’ trust and engagement toward virtual conversational assistants (VCAs). Likewise, Seymour and Van Kleek [42] observed that users’ relationship development with voice assistants is closely tied to both anthropomorphism and trust, where deeper relational engagement leads to stronger trust.

More recently, Li and Huang [43] found that anthropomorphic features—such as behavioral and emotional expressions—enhance purchase intention through the mediating role of cognitive trust in virtual livestreaming contexts. Synthesizing these theoretical and empirical insights, this study posits that when an AI avatar demonstrates a high degree of anthropomorphism (e.g., realistic appearance, natural language interaction, and emotional expressiveness), it can effectively increase consumers’ sense of social presence and emotional connection, thereby enhancing perceived trustworthiness.

H4.

Anthropomorphism has a positive effect on AI avatar trust.

2.6. Interaction Quality and AI Avatar Trust

Interaction quality refers to consumers’ subjective evaluation of an agent’s responsiveness, linguistic fluency, and communication clarity [44]. According to Service Quality Theory [45], the quality and efficiency of service interactions directly affect consumers’ satisfaction and trust toward the service provider. In digital interaction contexts, the Computers Are Social Actors (CASA) paradigm [46] posits that when agents demonstrate human-like responsiveness and conversational behaviors, users interpret such exchanges through a “social interaction” framework, thereby enhancing their sense of trust.

When virtual assistants or conversational agents exhibit high interaction quality—including fast responses, natural language, and clear communication—they not only improve user satisfaction but also enhance perceived social presence, which in turn strengthens trust toward the agent. Empirical studies provide robust support for this argument. De Visser et al. [47] showed in human–automation interaction that system responsiveness and communication fluency significantly increase users’ trust and willingness to cooperate. Xu et al. [48] found in social media chatbot service contexts that higher linguistic naturalness and response immediacy positively affect users’ trust and experience quality. Similarly, Harrison and Kwon [49] reported that an agent’s interaction style (social-oriented vs. task-oriented) influences user trust through perceived social support and interaction quality.

Therefore, this study posits that in AI avatar recommendation contexts, when the avatar demonstrates high interaction quality, such as quick response, linguistic fluency, and communicative clarity, consumers are more likely to perceive it as trustworthy.

H5.

Interaction quality has a positive effect on AI avatar trust.

2.7. AI Avatar Trust and Product Trust

Trust is widely regarded as a fundamental psychological mechanism that reduces uncertainty and perceived risk [50]. In digital marketing contexts, consumers often face incomplete or asymmetric information and thus rely on intermediary cues or third-party agents for decision-making. According to Trust Transfer Theory [51], trust in one entity can be transferred to another through social relationships or recommendation processes. In this study’s context, once consumers develop trust in an AI avatar, such trust may extend to the products or brands endorsed by that avatar.

Empirical research supports this perspective. McKnight, Choudhury, and Kacmar [4] demonstrated that in e-commerce settings, consumers’ trust in websites or intermediaries significantly influences their trust and acceptance of products and transactions. Similarly, Lankton et al. [52] found that trust in technological agents can be transferred—through both cognitive and affective channels—into trust in related services. More recently, Shin [53] reported that when users trust AI assistants, they are more likely to believe in the accuracy and reliability of the information and products recommended. Likewise, Gursoy et al. [54] revealed in the hospitality and tourism industry that trust in service robots positively affects customers’ trust in associated brands and services. These findings collectively indicate that trust exhibits a cross-level transference effect—from the agent to the product—particularly in decision-making scenarios where consumers heavily depend on digital intermediaries.

Therefore, it can be reasonably inferred that AI avatar trust plays a pivotal role in shaping product trust. When consumers perceive the AI avatar as honest, reliable, and competent, such trust is likely to be transferred to the recommended product, reinforcing positive perceptions of its quality and value.

H6.

AI avatar trust has a positive effect on product trust.

2.8. Product Trust and Purchase Intention

In the fields of e-commerce and digital marketing, trust is recognized as a fundamental mechanism for reducing uncertainty and perceived risk [50]. According to the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control jointly shape behavioral intentions. Within this framework, trust plays a crucial role in fostering positive attitudes and lowering perceived barriers to action [55]. When consumers develop trust in a product, they experience reduced transaction risk and information asymmetry [8], which enhances their confidence in decision-making and consequently increases their purchase intention.

Empirical studies have provided substantial support for this relationship. Kim et al. [56] demonstrated in a cross-cultural study that product trust significantly decreases consumers’ perceived risk and positively influences their purchase intentions. Similarly, Chaudhuri and Holbrook [57] found that brand trust not only strengthens purchase intention but also promotes long-term brand loyalty. More recent research has extended this understanding to digital contexts. Wu et al. [58] revealed that in online shopping settings, consumers’ product trust significantly enhances purchase intention through satisfaction and perceived value. Likewise, Lăzăroiu et al. [59] found that in social commerce environments, online trust and perceived risk are key antecedents of purchase intention—trust directly promotes purchase intention, while risk reduction indirectly strengthens it through trust formation.

Accordingly, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H7.

Product trust has a positive effect on purchase intention.

2.9. AI Avatar Trust and Purchase Intention

Trust is regarded as a fundamental evaluative basis for consumers when making decisions under uncertainty and perceived risk [8,50]. In digital interaction contexts, consumers are often unable to directly verify the authenticity of product information and must therefore rely on signals provided by intermediaries or platforms. According to Trust Transfer Theory, when consumers develop trust in an intermediary or an information source, that trust can be transferred to the products or services recommended by the source, thereby influencing subsequent purchasing behaviors [51].

Empirical evidence supports this view. Belanche, Casaló, Flavián, and Ibáñez-Sánchez [36] found that the credibility of virtual influencers significantly enhances followers’ attitudes and behavioral intentions, including purchase tendency. Similarly, Lou and Yuan [37] showed that consumers’ trust in social media influencers is a key determinant of their acceptance of branded content and purchase intention. In the context of artificial intelligence and digital agents, Gursoy, Chi, Lu, and Nunkoo [54] demonstrated that consumers’ trust in AI devices positively affects their intention to adopt and use such technologies, ultimately shaping their behavioral outcomes.

Taken together, these findings suggest that when consumers trust AI avatars, they are more likely to be persuaded by their recommendations and to form stronger intentions to purchase the endorsed products.

H8.

AI avatar trust has a positive effect on purchase intention.

2.10. Trust as a Mediating Mechanism

Within the context of persuasion and attitude change, the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) suggests that individuals form attitudes and intentions through two distinct processing routes: a central route, which involves rational elaboration based on message quality, and a peripheral route, which relies on heuristic processing of source or contextual cues [60]. However, the formation of attitudes and intentions is rarely a simple linear process of “cue → intention.” Instead, it typically involves a more proximal psychological evaluation that is closer to the core of decision-making. In online and AI-interaction contexts, this proximal evaluation is often represented by trust [4,8,50]. Trust reduces uncertainty and perceived risk while enhancing predictability, thereby serving as a crucial psychological bridge connecting various central and peripheral cues to purchase intention.

Furthermore, Trust Transfer Theory [51] posits that trust in one entity (e.g., a platform or agent) can be transferred to another entity (e.g., a specific product or brand) through associative or recommendation-based relationships. In the context of this study, product-level trust is more likely to capture the effects of product-related cues (e.g., brand awareness and perceived quality), while agent-level trust (AI avatar trust) is more likely to absorb the effects of source- and interaction-related cues (e.g., social endorsement, anthropomorphism, and interaction quality).

Meanwhile, theoretical perspectives such as Social Proof Theory [33], Signaling Theory [17,18], Cue Utilization Theory [26], and Social Presence/Media Richness Theory [39] collectively explain that different types of cues enhance credibility, diagnosticity, and processing fluency, thereby influencing trust, which in turn drives purchase intention.

Based on this integrative theoretical perspective, this study proposes the following mediating hypotheses:

2.10.1. Product-Level Mediation: Brand Awareness, Perceived Quality → Product Trust → Purchase Intention

Brand awareness, as both a market signal and a familiarity heuristic, enhances brand credibility and reduces uncertainty [16,17,18]. This perceived credibility primarily manifests in consumers’ judgments of whether a product is reliable, which in turn drives purchase intention. Meanwhile, perceived quality—representing a central-route message within the ELM framework—strengthens product trust by improving consumers’ evaluations of product excellence and reliability through cue utilization and signaling mechanisms [25,26,29,30].

Under the ELM framework, the effects of these two cues on purchase intention are theoretically expected to follow an indirect path through trust, rather than a purely direct route.

H9a.

Product trust mediates the relationship between brand awareness and purchase intention.

H9b.

Product trust mediates the relationship between perceived quality and purchase intention.

2.10.2. Agent-Level Mediation: Social Endorsement, Anthropomorphism, Interaction Quality → AI Avatar Trust → Purchase Intention

Social endorsement cues (e.g., likes, comments, and follower counts) provide social proof that “others have already adopted,” functioning as peripheral cues that enhance source credibility under low elaboration conditions. Such cues first strengthen trust in the AI avatar, which subsequently translates into higher acceptance of its recommendations and stronger purchase intention [33,34,35,36].

Anthropomorphism enhances perceived credibility of the agent by evoking social presence and mind attribution, thereby increasing consumers’ willingness to accept its suggestions and engage in purchase behavior [2,12,38].

Interaction quality—reflected in response speed, linguistic naturalness, and clarity of communication—has been shown in the CASA framework and automation trust literature to be interpreted by users as a form of “human-like interaction.” High interaction quality enhances perceptions of competence and integrity of the agent, thereby strengthening trust and ultimately increasing adoption and purchase likelihood [44,47,48].

H9c.

AI Avatar trust mediates the relationship between social endorsement cues and purchase intention.

H9d.

AI Avatar trust mediates the relationship between anthropomorphism and purchase intention.

H9e.

AI Avatar trust mediates the relationship between interaction quality and purchase intention.

2.11. Control Variables: Trust Disposition and Experience

In explaining purchase intention, this study controls for trust disposition and past experience to avoid potential confounding effects.

First, trust disposition refers to an individual’s generalized tendency to trust others or new technologies [61]. Prior research indicates that trust disposition is a stable personality trait that influences people’s initial trust toward emerging technologies or agents [8]. For example, consumers with a high trust disposition may naturally exhibit higher levels of product trust and adoption intention regardless of the AI avatar’s specific features. If this variable were not controlled, the relationship between “AI Avatar characteristics → trust → purchase intention” might be confounded by individual differences in generalized trust tendencies.

Second, experience is another important control variable. Previous studies have shown that consumers’ prior interactions with digital agents or online shopping platforms significantly affect their trust and behavioral intentions [62]. For instance, consumers who have had positive online transaction experiences are more likely to trust AI avatar recommendations, thereby increasing their purchase intention. Conversely, those with negative experiences may display lower trust levels toward the AI avatar.

Therefore, this study includes trust disposition and experience as control variables to eliminate individual-level differences stemming from existing trust tendencies or prior usage experiences. This ensures that the observed relationships among the key constructs more accurately reflect the theoretical mechanism of AI Avatar characteristics → trust → purchase intention.

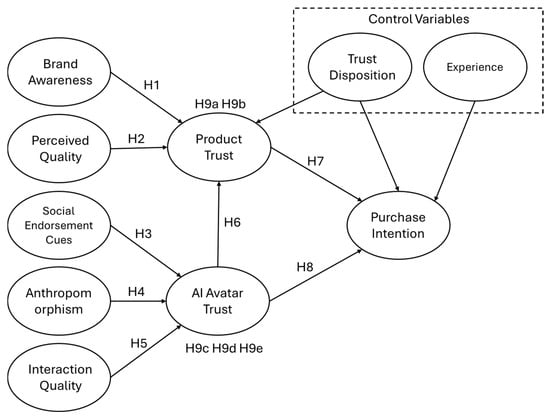

The proposed research framework, including all hypothesized paths, is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research model. Note: H9a–H9e represent the indirect (mediated) effects of brand awareness, perceived quality, social endorsement cues, anthropomorphism, and interaction quality via product trust and AI Avatar trust.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Research Participants and Data Collection

This study targeted consumers with online shopping experience, focusing particularly on their perceptions and behavioral responses toward products recommended by AI avatars. Given that the research model involves multiple constructs—including brand awareness, perceived quality, product trust, social endorsement cues, anthropomorphism, interaction quality, AI avatar trust, purchase intention, trust disposition, and prior experience—participants were required to have a certain level of digital consumption experience to ensure valid evaluations of the questionnaire items. Data were collected through an online survey, distributed via social media platforms, email invitations, and survey platforms such as Google Forms and WJX. To ensure diversity and representativeness of the sample, a screening question was included at the beginning of the questionnaire to verify whether respondents had previously engaged with product information or recommendations through online platforms or AI agents. Only those who met this criterion were allowed to proceed. Demographic variables—including gender, age, education level, shopping frequency, and AI usage experience—were also recorded for further analysis. Data collection was conducted between August and September 2025, yielding a total of 652 responses. After excluding incomplete or abnormally fast responses, 378 valid samples remained. The final sample size satisfies the minimum requirements for Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) [63] and provides sufficient statistical power to test the proposed hypotheses.

The demographic composition of the respondents closely aligns with the characteristics commonly observed among consumers who interact with AI-assisted shopping tools. Industry reports consistently indicate that users of AI avatars and AI-generated product recommendations tend to be younger adults, well-educated individuals, and frequent online shoppers. Our sample reflects these same attributes—most participants were within the young-to-middle-age range, possessed higher levels of education, and demonstrated active online shopping behavior. Accordingly, the sample is considered representative of the primary population segment relevant to AI-mediated shopping environments.

3.2. Measurement Instruments

The questionnaire of this study was designed based on the proposed research framework and the operational definitions of each construct. All items were measured using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) to capture respondents’ degree of agreement with each statement. The measurement items for all major constructs were adapted from well-established academic literature and revised to fit the context of this study, thereby ensuring content validity.

Specifically, items for Brand Awareness were adapted from Keller [16] to measure consumers’ familiarity and recognition of a brand. Perceived Quality items were based on Washburn and Plank [64], assessing consumers’ subjective evaluations of the overall excellence and value of a product. Product trust was measured using items adapted from Morgan and Hunt [65] and Schlenker et al. [66], focusing on consumers’ beliefs in the reliability and quality of products recommended by AI avatars. Social endorsement cues were drawn from Che, Cheung, and Thadani [15] and Lim et al. [67], reflecting consumers’ perceptions of the avatar’s popularity, user support, and public evaluation. Anthropomorphism items were adapted from Waytz, Cacioppo, and Epley [2] and Qiu and Benbasat [12], measuring the extent to which consumers perceive the AI avatar as human-like in terms of appearance, language, and emotional expression. Interaction quality was measured using items adapted from de Visser et al. [68] and Lee and See [44], evaluating the avatar’s responsiveness, linguistic naturalness, and clarity in communication. AI Avatar trust was adapted from Lauer and Deng [5] and Qiu and Benbasat [12], capturing consumers’ perceived honesty, accuracy, and credibility of the AI avatar. Purchase intention was measured based on Dodds et al. [69] and Washburn and Plank [64], assessing consumers’ willingness and likelihood to purchase the products recommended by the AI avatar. In addition, trust disposition was adapted from Gefen [8], McKnight, Choudhury, and Kacmar [4] and Wang et al. [70] to measure individuals’ general tendency to trust others or new technologies. Experience was adapted from Yoon [71] and Pavlou and Gefen [72], reflecting consumers’ prior experiences purchasing products through online platforms or AI agents. Besides the main constructs, the questionnaire also included demographic variables such as gender, age, education level, and consumption experience, which were used for sample description and subsequent control analyses.

Also, a screening question was included at the start of the survey: “Have you ever used an AI avatar, virtual assistant, or AI-generated product recommendation while shopping online?” Only respondents who answered “Yes” proceeded, ensuring a relevant AI-mediated shopping experience.

3.3. Data Analysis

This study employed Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) as the primary analytical method, using SmartPLS 4.0 software for model estimation. PLS-SEM was chosen because it is suitable for simultaneously examining both the measurement and structural models, is less restrictive in terms of sample size, and is effective in analyzing complex research frameworks involving multiple mediating and moderating effects [63]. The data analysis procedure consisted of several steps. First, descriptive statistics and normality tests were conducted to understand the sample characteristics and ensure that the data met the assumptions required for subsequent analyses. Second, the measurement model was assessed to examine the reliability and validity of the constructs. Internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR), while convergent validity was assessed through average variance extracted (AVE) and outer loadings. Discriminant validity was verified using the Fornell–Larcker criterion. After confirming the adequacy of the measurement model, the structural model was analyzed to test the hypothesized relationships among the constructs. Path coefficients and their significance levels were evaluated using the bootstrapping technique with 5000 resamples. The coefficient of determination (R2) was examined to assess the explanatory power of the model. In addition, mediating and moderating effects were further tested. For mediation analysis, the significance of the indirect effects was verified through the bootstrapping approach to determine whether the mediating relationships were statistically significant.

4. Research Results

4.1. Demographic Profile

A total of 378 valid questionnaires were collected for this study. The demographic characteristics of the respondents are summarized in Table 1. Female respondents accounted for 56.3% (n = 213), while males made up 43.7% (n = 165), indicating that female consumers participated slightly more in AI-assisted shopping contexts. In terms of age distribution, respondents aged 21–30 years represented the largest group (57.7%), followed by those aged 31–40 years (17.2%), 41–50 years (15.9%), and over 50 years (9.3%). This suggests that the sample mainly comprised younger consumers, consistent with the demographic most engaged in AI-based consumption environments. Regarding education level, 60.3% of respondents held a bachelor’s degree, 28.8% had a graduate degree or above, and 10.8% had a high school education or below, indicating that most respondents were well educated and possessed adequate technological literacy. For AI experience, 65.9% of respondents had used AI for less than six months, 16.7% for six months to one year, and 17.5% for more than one year, suggesting that most participants were still in the early stages of AI adoption. Concerning shopping frequency, 87.8% of respondents reported shopping more than five times per month, while 12.2% shopped fewer than five times, indicating that the majority were active online consumers. Overall, the sample consisted mainly of young, well-educated, and digitally active consumers, effectively reflecting the characteristics of individuals likely to form trust and purchase intentions in AI-mediated interaction contexts—consistent with the purpose of this study, examining how AI avatars influence consumer behavior.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of respondents.

4.2. Convergent Validity

According to the criteria proposed by Fornell and Larcker [73] and Nunnally [74], the assessment of validity in the measurement model includes several indicators: factor loadings should exceed 0.7, composite reliability (CR) should be greater than 0.7, the average variance extracted (AVE) should be above 0.5, and Cronbach’s α should be greater than 0.7. The statistical results of this study indicate that all factor loadings for each construct ranged from 0.707 to 0.967, exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.7. The composite reliability values ranged from 0.883 to 0.971, confirming strong internal consistency. The AVE values ranged from 0.712 to 0.919, all above 0.5, demonstrating satisfactory convergent validity. Additionally, the Cronbach’s α values for all constructs were between 0.801 and 0.956, meeting the reliability standard. In summary, these results demonstrate that the measurement model in this study exhibits excellent convergent validity, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Convergent validity analysis.

4.3. Discriminant Validity

This study assessed the discriminant validity of the reflective constructs using the average variance extracted (AVE) method. According to the criterion proposed by Fornell and Larcker [73], discriminant validity is established when the square root of the AVE for each construct exceeds the correlations between that construct and any other constructs in the model. The analysis results indicate that, for all constructs in this study, the square roots of their AVE values were greater than the corresponding inter-construct correlation coefficients. This finding confirms that each construct is empirically distinct from the others and captures unique conceptual dimensions. Overall, the results demonstrate that the measurement model possesses adequate discriminant validity, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity analysis.

4.4. Model Fit

The goodness of fit (GOF) index was used to assess the overall model fit of the conceptual framework. Following the formula proposed by Vinzi [75], the GOF value is calculated as . According to the established benchmarks, a GOF value of 0.10 indicates a small fit, 0.25 indicates a medium fit, and 0.36 or higher represents a strong fit. The GOF value for this study was 0.596, which exceeds the threshold for a strong model fit. This result demonstrates that the overall research model exhibits a high level of goodness of fit, indicating that the measurement and structural models collectively provide a robust representation of the empirical data.

4.5. Path Analysis

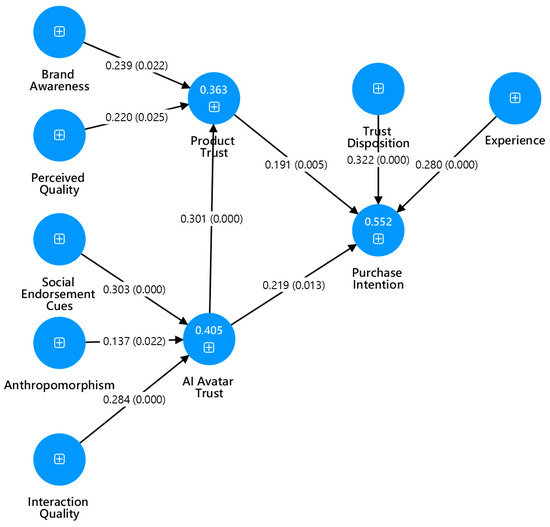

The results of the hypothesis testing are summarized in Table 4 and Figure 2. For H1, brand awareness was found to have a significant positive effect on product trust (β = 0.239, t = 2.289, p = 0.022), supporting the hypothesis. Similarly, H2 was supported, as perceived quality significantly predicted product trust (β = 0.220, t = 2.235, p = 0.025). With regard to AI avatar trust, H3 was supported, indicating that social endorsement cues had a significant positive effect (β = 0.303, t = 5.796, p < 0.001). H4 was also supported, as anthropomorphism significantly influenced AI avatar trust (β = 0.137, t = 2.298, p = 0.022). Likewise, H5 was confirmed, showing that interaction quality positively affected AI avatar trust (β = 0.284, t = 5.250, p < 0.001). In addition, H6 was supported, demonstrating that AI avatar trust significantly predicted product trust (β = 0.301, t = 4.029, p < 0.001). Regarding purchase intention, H7 was supported, as product trust had a significant positive effect (β = 0.191, t = 2.790, p = 0.005). H8 was also supported, with AI avatar trust positively influencing purchase intention (β = 0.219, t = 2.486, p = 0.013). For the control variables, both experience (β = 0.280, t = 3.639, p < 0.001) and trust disposition (β = 0.322, t = 5.776, p < 0.001) were found to significantly and positively predict purchase intention.

Table 4.

Results of path analysis.

Figure 2.

PLS-SEM structural model.

4.6. Mediating Effect Analysis

Table 5 presents the indirect effects of each construct through the mediating variables. The results show that the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of all indirect paths do not include zero, indicating that all mediation effects are statistically significant. First, brand awareness exerts a significant indirect effect on purchase intention through product trust (β = 0.046, 95% CI = [0.004, 0.091]), suggesting that greater brand familiarity enhances product trust, thereby increasing consumers’ purchase intentions. Second, perceived quality also has a significant positive indirect effect on purchase intention through product trust (β = 0.042, 95% CI = [0.003, 0.118]). This indicates that when consumers perceive higher product quality, they are more likely to develop trust in the product, which subsequently strengthens their purchase intention. Furthermore, anthropomorphism shows a significant positive indirect effect on purchase intention via AI Avatar trust (β = 0.030, 95% CI = [0.001, 0.064]). This result suggests that higher levels of human-like characteristics in AI avatars enhance users’ trust, thereby promoting purchase intention.

Table 5.

Indirect effect analysis.

Similarly, interaction quality demonstrates a significant positive indirect effect on purchase intention through AI Avatar trust (β = 0.062, 95% CI = [0.014, 0.133]), indicating that smoother and more natural interactions increase the avatar’s perceived credibility, which in turn enhances consumers’ purchase intention. Finally, social endorsement cues also exert a significant positive indirect effect on purchase intention via AI Avatar trust (β = 0.066, 95% CI = [0.014, 0.147]). This finding implies that when AI avatars are accompanied by social validation cues—such as likes, comments, or follower numbers—they can effectively strengthen perceived trustworthiness and subsequently boost purchase intention.

Overall, these results confirm that both product-level factors (brand awareness and perceived quality) and AI interaction-level factors (anthropomorphism, interaction quality, and social endorsement cues) influence consumers’ purchase intention indirectly through trust mechanisms. This highlights the pivotal role of trust as a key mediating variable in the proposed research model.

5. Research Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Research Conclusions

5.1.1. Relationship Between Brand Awareness, Perceived Quality, and Product Trust

The empirical results of this study reveal that both brand awareness and perceived quality have significant positive effects on product trust, supporting hypotheses H1 and H2. This finding not only echoes the propositions of Signaling Theory and Cue Utilization Theory but also extends their applicability to the context of AI-based product recommendations. In traditional marketing research, brand awareness has been regarded as a symbol of consumer familiarity and credibility, which helps reduce information asymmetry and perceived risk [16,17]. However, in the context of AI Avatar recommendations, the brand signal is no longer directly conveyed by the brand itself but rather mediated through the AI Avatar as an intermediary. The results indicate that when an AI Avatar recommends products from familiar brands, consumers tend to transfer their trust in the brand to the AI source, thereby reducing concerns about algorithmic opacity. This phenomenon, referred to as algorithm-mediated trust transfer, provides a novel extension of traditional branding theory.

Similarly, perceived quality, serving as a central cue within the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) framework, demonstrates its rational persuasive role in AI-driven recommendation settings. While prior studies have focused on physical or online retail environments [25,29], this study finds that when AI Avatars deliver clear, accurate, and detailed product information, consumers develop cognitive trust based on quality cues. This suggests that even in virtual interaction contexts, high-quality informational signals can effectively foster rational trust formation. Overall, by integrating ELM with trust-based theories, this study illustrates how brand awareness (as a peripheral cue) and perceived quality (as a central cue) jointly shape product trust within AI-mediated communication frameworks, offering valuable insights into AI-driven brand trust formation in the digital era.

5.1.2. Relationship Between Social Endorsement Cues, Anthropomorphism, Interaction Quality, and AI Avatar Trust

The empirical results indicate that social endorsement cues, anthropomorphism, and interaction quality all have significant positive effects on AI Avatar trust, supporting Hypotheses H3, H4, and H5. These findings validate the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) by demonstrating that both peripheral and central cues play vital roles in trust formation, while also extending the applicability of the Computers Are Social Actors (CASA) model [76] to AI-avatar contexts. First, the results regarding social endorsement cues reveal that consumers tend to rely on others’ actions—such as likes, comments, and follower counts—as heuristic indicators of trust and credibility, consistent with Social Proof Theory [9]. In situations of low involvement or limited information, these social signals act as peripheral cues, serving as “social trust proxies” that quickly build trust toward AI avatars. This finding aligns with Belanche, Casaló, Flavián, and Ibáñez-Sánchez [36], who emphasized the persuasive power of social endorsement in virtual influencer contexts. Our study further extends this logic to algorithm-driven social endorsement, highlighting how AI-mediated cues can generate similar social influence effects.

Second, the significant influence of anthropomorphism on AI Avatar trust reflects users’ tendency to attribute human-like traits to technological agents. According to anthropomorphism theory [38], when non-human entities display human-like appearances, emotional expressions, and language styles, users interpret interactions through interpersonal frameworks, fostering emotional trust and social presence. Consistent with Qiu and Benbasat [12], this study confirms such effects in dynamic AI avatars capable of real-time conversational generation, illustrating how anthropomorphism functions as a peripheral route that enhances emotional engagement and perceived authenticity.

Finally, interaction quality—including responsiveness, linguistic naturalness, and content accuracy—significantly affects AI Avatar trust. This result is consistent with the Trust in Automation Theory [44], suggesting that when human–AI interaction demonstrates fluency and reliability, users infer higher competence and integrity, which promotes trust. Unlike social endorsement and anthropomorphism, interaction quality requires active cognitive evaluation of message content and system performance, thus representing a central route cue within the ELM framework. This finding supports Xu, Liu, Guo, Sinha, and Akkiraju [48], who found that linguistic coherence and responsiveness enhance perceived trust and social presence in chatbot interactions. Extending this to AI avatars, the current study highlights interaction quality as a trigger for central processing, facilitating a deeper, reasoned trust formation mechanism.

In summary, social endorsement and anthropomorphism operate as peripheral cues that evoke intuitive and affective trust responses, while interaction quality serves as a central cue that drives analytical trust formation. Together, these findings clarify the dual-route persuasion process in AI-avatar contexts and reinforce the theoretical distinction between heuristic and elaborative trust-building pathways.

5.1.3. Relationship Between AI Avatar Trust and Product Trust

The empirical results demonstrate that AI Avatar trust has a significant positive effect on product trust, supporting Hypothesis H6. This finding suggests that in digital interaction contexts, consumers’ trust in an AI agent can cross the human–machine boundary and transfer to the product it recommends, forming a trust transfer mechanism. This not only extends the classical Trust Theory [50] but also supports McKnight et al.’s [4] cross-level trust propagation model, which posits that consumers’ trust in one entity (e.g., a website, platform, or avatar) can be transferred to another (e.g., a product or brand).

From a theoretical standpoint, this finding confirms the applicability of Trust Transfer Theory [51] in the era of artificial intelligence. Traditionally, trust transfer was observed mainly between human and organizational levels—for instance, customer trust in a parent brand extending to sub-brands or subsidiaries. However, the current study finds that this mechanism also applies to human–AI interaction contexts. When consumers perceive that an AI Avatar exhibits competence, integrity, and benevolence during interaction [50], they are likely to infer that the recommended products possess similar reliability and value, thereby enhancing product trust.

Furthermore, the results highlight the theoretical notion of the AI agent as a trust intermediary. Unlike traditional online recommendation systems that primarily deliver information, the AI Avatar actively constructs and transmits trust through its communicative characteristics. During interaction, consumers experience human-like sincerity and transparency due to the Avatar’s natural language dialogue, real-time responsiveness, and anthropomorphic cues [54]. This interaction-driven trust encourages consumers to accept its recommendations and transfer that trust to the product level.

From the perspective of the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM), AI Avatar trust functions as a mediating cognitive node in the belief formation process. Along the central route, when the Avatar presents information with precision and expertise, consumers’ rational evaluations translate into cognitive trust toward the product. Meanwhile, under the peripheral route, the Avatar’s credibility and social endorsement cues trigger heuristic trust, enhancing the persuasiveness of its recommendations. Together, these dual mechanisms form an “AI persuasion–trust–behavioral intention” chain, explaining how trust serves as a psychological bridge connecting AI agents with consumer decision-making behavior.

5.1.4. Relationship Among AI Avatar Trust, Product Trust, and Purchase Intention

The empirical results of this study show that AI Avatar trust not only has a direct positive effect on purchase intention (supporting H8), but also exerts an indirect effect through product trust (supporting the sequential relationship between H6 and H7), revealing a clear partial mediation effect. This indicates that in AI-driven consumption contexts, AI Avatar trust serves as a core psychological mechanism that promotes purchase intention, while product trust functions as the mediating bridge connecting agent-level trust with behavioral intention.

From the perspective of Trust Theory and Trust Transfer Theory [51], consumer trust established during interaction with an AI Avatar exhibits a cross-level transfer characteristic. In other words, when consumers believe in the competence, integrity, and benevolence of an AI Avatar [50], they tend to infer that the recommended products also possess similar reliability and value, thereby enhancing both product trust and purchase intention. This process supports McKnight et al.’s [4] concept of trust propagation and reveals a “cognitive–affective–behavioral” chain mechanism in AI-driven consumer decision-making.

From the standpoint of the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM), the influence of AI Avatar trust on purchase intention operates through two distinct routes.

- Direct route: Under low-involvement or heuristic processing conditions, consumers may rely on the Avatar’s credibility, social endorsements, and interaction performance to form peripheral trust, which directly increases their purchase tendency [36,60].

- Indirect route: Under high-involvement or rational processing conditions, the Avatar’s professionalism and information quality foster cognitive trust in the recommended product, which subsequently strengthens purchase intention.

This “trust-chain mechanism” illustrates that consumers’ persuasion processes in AI interactions involve not only attitude formation but also multi-layered trust judgments toward both the source (AI Avatar) and the content (product).

Empirically, these findings are consistent with Kim, Ferrin, and Rao [56], who found that trust promotes purchase intention by reducing perceived risk and enhancing value evaluation. Similarly, Gursoy, Chi, Lu, and Nunkoo [54] demonstrated that trust is a critical antecedent of user adoption and decision-making in AI service applications. Extending these insights, the present study highlights that the combined effect of AI Avatar trust and product trust elucidates how decision-making unfolds in human–AI interactions and marks a shift from “interpersonal trust transmission” to “algorithm-mediated trust.”

In conclusion, this study proposes that in the age of AI marketing, trust is no longer a single-layered cognitive evaluation but a multi-level transmission process that flows across agents and products. As a digital persona, the AI Avatar’s credibility not only determines whether consumers accept its recommendations but also shapes their emotional security and behavioral intention toward the products it suggests. This finding underscores the theoretical significance of AI-mediated trust formation, identifying trust as a central psychological node within AI persuasion processes and providing a critical foundation for future research on human–AI relationships and consumer psychology.

5.1.5. The Mediating Role of Trust

This study further validates the theoretical assumption that trust serves as a psychological bridge between central and peripheral cues in AI-driven recommendation contexts, corresponding to hypotheses H9a–H9e. The empirical results reveal significant mediation effects of trust at both the product level and the agent (AI Avatar) level, indicating that consumers do not form purchase intentions directly from external cues. Instead, they engage in a multistage evaluative process in which trust acts as a proximal cognitive mechanism linking cues to behavioral outcomes. These findings not only echo the dual-route persuasion framework of the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) [60] but also extend the applicability of the Trust Transfer Theory [51] to human–AI interaction environments.

First, within the product-level mediation (H9a and H9b), both brand awareness and perceived quality influence purchase intention indirectly through product trust. As a marketplace signal, brand awareness enhances familiarity and predictability [17], thereby reducing the perceived risk associated with information asymmetry. Perceived quality, serving as a central-route cue, drives cognitive trust formation through rational evaluation of product attributes and performance [25,29]. The empirical evidence supports H9a and H9b, showing that these cues affect intention primarily through the mediating role of product trust. This implies that, although consumers may encounter various AI-delivered cues, their final decision relies on a rational assessment of whether the product itself is trustworthy. Hence, product trust functions as a stable mediator within the central-route persuasion process, bridging informational cues and behavioral outcomes.

Second, regarding the agent-level mediation (H9c, H9d, H9e), social endorsement cues, anthropomorphism, and interaction quality all exert indirect effects on purchase intention through AI Avatar trust. Specifically, social endorsement cues—such as likes, comments, and follower counts—create social proof and collective credibility that foster affective trust toward the AI Avatar [6,33], supporting H9c. Anthropomorphism enhances perceptions of social presence and psychological closeness [12,38], prompting users to apply interpersonal trust frameworks in evaluating the Avatar’s integrity and benevolence, thereby increasing acceptance of its recommendations (supporting H9d). Meanwhile, interaction quality demonstrates a combined rational–affective mediation effect (H9e): high responsiveness, natural language fluency, and accurate communication elevate perceptions of competence and sincerity [44,48], strengthening trust and ultimately leading to greater behavioral intention. These findings confirm that AI Avatar trust mediates the effects of all three cues on purchase intention, illustrating that trust formation in human–AI interaction is not purely heuristic but involves both social and cognitive processing.

More importantly, the study identifies a chain mediation effect, in which AI Avatar trust further enhances product trust, which then promotes purchase intention. In other words, trust generated at the agent level is subsequently transferred to the product level, driving behavioral intention. This multi-level trust transfer validates the cross-object trust propagation proposed by McKnight, Choudhury, and Kacmar [4] and uncovers a psychological pathway of “source credibility → content trust → behavioral intention” in AI-driven persuasion. The results highlight the pivotal role of AI Avatar trust as a mediating cognitive node, influencing not only product evaluations but also the overall decision-making logic of consumers.

In summary, the mediating effects of trust indicate that persuasion in AI Avatar contexts has evolved from a simple “cue → intention” process into a multi-layered mechanism of “cue → trust → intention.” Product trust provides rational assurance through cognitive evaluation, while AI Avatar trust delivers emotional and social security through affective attachment. Together, they form a comprehensive persuasion mechanism. These findings enrich the theoretical understanding of the ELM by revealing how trust operates as a dynamic mediator across routes, and they extend the Trust Transfer Theory to digital marketing contexts. Ultimately, this study confirms that trust is the most critical psychological mediator in AI-driven consumer decision-making, linking diverse cue types to multi-level behavioral responses and establishing AI-mediated trust formation as a foundational construct for future research on human–AI relations and consumer psychology.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This study centers on AI Avatars and integrates the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) with Trust Theory to construct and validate a cross-level trust transference chain—from AI Avatar trust to product trust and ultimately to purchase intention. The findings respond to the growing scholarly interest in AI persuasion mechanisms and trust formation processes, offering important contributions across three theoretical dimensions: theoretical integration, model innovation, and conceptual expansion.

- Theoretical Integration: Bridging ELM and Trust Theory

This study addresses the critique that prior research on AI persuasion has lacked a clear psychological mediator [77]. By integrating ELM and Trust Theory, it proposes a dual-route model explaining how AI Avatars influence consumer decision-making. Traditional ELM emphasizes the effects of message quality (central route) and source characteristics (peripheral route) on attitude formation. This study further demonstrates that, in AI marketing contexts, both routes operate through trust as a mediating mechanism leading to behavioral intention.

Specifically, perceived quality and brand awareness foster product trust via rational processing (central route), whereas social endorsement cues, anthropomorphism, and interaction quality shape AI Avatar trust through heuristic processing (peripheral route). These findings deepen the psychological logic of ELM in digital interaction contexts, identifying trust as a mediating cognitive node in persuasion processes. Moreover, this study enriches Trust Theory by illustrating that trust is not a static relational construct but a dynamic attitudinal process embedded in human–AI communication.

- 2.

- Model Innovation: Extending Cross-Level Trust Transference Theory

The study reveals a cross-level trust transference mechanism in AI marketing environments. Traditional trust models [50,65] typically emphasize single-level interactions—such as trust between consumers and brands or organizations. However, the current findings confirm that trust can transfer dynamically across levels, from agent-level (AI Avatar) to product-level, ultimately shaping behavioral intention.

This supports and extends Trust Transfer Theory [51] by expanding its scope from static brand–sub-brand relationships to AI agent–product interactions. The study introduces the concept of AI-mediated trust formation, positing that AI Avatars function not merely as information transmitters but as trust generators and translators. Consumers’ trust in the AI Avatar—rooted in perceptions of competence, integrity, and benevolence—translates into favorable expectations of the recommended product. Thus, the research establishes a theoretical framework describing how AI agents participate in co-constructing a multi-layered trust system, capable of guiding, transferring, and amplifying consumer trust.

- 3.

- Conceptual Expansion: Integrating AI Persuasion, Social Presence, and Human–AI Relations

Finally, this study contributes to the theoretical development of both AI Persuasion Theory and the Human–AI Trust Relationship by providing an integrative perspective. Traditional persuasion theories generally assume human persuaders; however, this research demonstrates that nonhuman agents (AI Avatars) can evoke interpersonal-like trust through social cues (e.g., social endorsements), emotional cues (e.g., anthropomorphism), and interaction cues (e.g., communication quality).

These findings support the Computers Are Social Actors (CASA) model and extend its implications to the AI era, where parasocial interactions with algorithmic agents increasingly shape consumer perceptions. Building on this, the study proposes the concept of Trust-Mediated AI Persuasion Theory, which posits that consumers first develop affective and cognitive trust toward AI Avatars, and subsequently transform this trust into attitudinal and behavioral change toward the recommended products.

This conceptual advancement deepens our understanding of algorithmic persuasion, addressing ongoing debates in Human–AI Interaction research regarding whether AI systems can truly establish trust [78]. Ultimately, the study positions trust as the central psychological mechanism bridging AI persuasion, social cognition, and consumer behavior—offering a unified theoretical foundation for future explorations of AI-mediated communication and decision-making.

5.3. Managerial Implications

This study reveals that the influence of AI Avatars in digital marketing extends far beyond simple information delivery—they can fundamentally reshape consumer decision-making through trust-building and transference mechanisms. The findings demonstrate that AI Avatar trust and product trust jointly drive purchase intention, while factors such as brand awareness, perceived quality, social endorsement, anthropomorphism, and interaction quality serve as key antecedents. Based on these insights, this section provides practical recommendations from three managerial perspectives—AI Avatar design, brand integration, and trust management—to help organizations build a sustainable trust foundation in AI-driven marketing contexts.

- AI Avatar Design and Trust-Oriented Interaction Strategies

The design of AI Avatars should center on perceived trustworthiness as a core principle. The results show that anthropomorphism and interaction quality are two critical determinants of trust. Companies developing or deploying AI Avatars should focus on the following directions:

- Optimization of Human-like Attributes:Enhance social presence and emotional connection through natural language, emotional expression, and conversational tone, allowing consumers to interpret the Avatar’s behavior through an interpersonal trust framework that reinforces perceptions of integrity and competence.

- Enhancement of Interaction Quality:Ensure fast response times, natural language fluency, and informational accuracy to improve the communication experience and trust perception. Firms may adopt LLM-based systems to achieve consistent, seamless interaction quality.

- Transparency and Consistency in Behavior Design:Trust stems from predictability. Businesses should clearly disclose the AI’s identity (e.g., “Powered by AI”) and operating principles to maintain consistent behavior, reducing confusion and privacy concerns.

- 2.

- Brand and AI Marketing Integration Strategies

The findings indicate that brand awareness and perceived quality significantly enhance product trust, underscoring the importance of synergy between brand and AI Avatars. Companies should adopt an “algorithmic embodiment of brand trust” approach, focusing on the following practices:

- Avatarization of Brand Personality:The AI Avatar should embody the brand’s image and values. For example, luxury brands may adopt a professional and composed persona, while lifestyle brands can employ a friendly and conversational tone—turning the Avatar into an extension of brand personality.

- Quality-Centric Messaging:During product recommendations, emphasize tangible quality signals—such as functionality, durability, and sustainability—rather than relying solely on promotional language. This maintains rational trust and supports long-term brand credibility.

- Leveraging Social Endorsement:Integrate user reviews, interaction data, and authentic feedback directly into the AI interface so that consumers encounter social proof (“others have adopted”) during interactions, thereby enhancing persuasiveness and trust transfer.

- 3.

- Trust Management and Customer Relationship Strategies

From a Customer Relationship Management (CRM) perspective, trust should be treated as the core asset of the AI marketing ecosystem. Since trust formation is a cumulative psychological process, companies should continuously monitor and strengthen trust maintenance mechanisms:

- Develop an AI Trust Analytics System:Use data analytics to track user trust dynamics toward AI Avatars by examining correlations among tone, accuracy, and satisfaction, thereby identifying early signs of trust erosion.

- Enhance Customer Education and Empowerment:Increase consumer understanding of AI systems’ logic and data sources to reduce uncertainty and perceived risk. Research shows that information transparency significantly enhances technological trust and adoption intention [53].

- Integrate the Brand–Product–AI Avatar Trust Loop:The study’s proposed “AI Avatar → Product → Purchase Intention” chain demonstrates that trust can evolve into a self-reinforcing cycle through ongoing interaction. Companies can thus position AI Avatars as trust maintainers rather than mere sales tools.

In summary, this study asserts that in the era of AI marketing, trust is competitive capital. The AI Avatar is not merely a technological innovation but an embodied extension of brand trust. Only by adopting an integrated perspective across design, interaction, branding, and trust can companies stand out in today’s information-saturated market and build a sustainable human–AI trust relationship.

5.4. Research Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study integrates the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) and Trust Theory to construct and validate a model of AI Avatar–driven consumer trust and purchase intention, several limitations remain, suggesting directions for future research. First, theoretical level: This study focused on how the central and peripheral routes influence trust formation through ELM. However, trust is inherently dynamic and multi-layered [78]). Future studies could incorporate Dynamic Trust Theory or ethical trust perspectives to explore how trust evolves with long-term interaction and increasing AI autonomy. Additionally, researchers may extend the current unidirectional “AI Avatar → Product → Purchase Intention” model to examine feedback and diffusion effects of trust across agents and platforms. Second, methodological level: The present study employed a cross-sectional survey and PLS-SEM analysis, which ensures statistical robustness but limits the ability to capture the real-time process of trust formation. Future research could use experimental or longitudinal designs to observe how trust changes after repeated interactions, or combine eye-tracking and physiological measures to analyze cognitive processing along the central and peripheral routes. Expanding sample diversity—such as including participants from different age groups and cultural contexts—would also allow for an examination of moderating effects of technological trust tendency and cultural orientation. Third, contextual level: This study focused primarily on general retail and e-commerce contexts. Future research could extend the model to healthcare, education, and metaverse commerce, testing trust formation under varying levels of risk and involvement. With the rapid advancement of generative AI, issues such as AI autonomy and controllability will become increasingly salient. Future studies should investigate how these factors affect trust stability and consumer acceptance in evolving digital ecosystems.

Moreover, several empirical limitations warrant further attention. First, the study relied on self-reported data collected from a single source, which may introduce response bias and potential common method variance (CMV). Although procedural remedies were implemented, future studies may adopt multi-source or behavioral data (e.g., interaction logs, clickstream behavior) to reduce CMV concerns. Second, the sample largely consisted of younger and digitally active consumers, which aligns with typical AI-avatar users but still limits the generalizability of the findings to older or less digitally literate populations. Future research could employ stratified or quota sampling to capture a broader range of consumer groups. Third, while the study examined AI avatars in a general e-commerce setting, trust dynamics may vary significantly across high-risk contexts (e.g., healthcare, financial services) or highly immersive environments (e.g., virtual try-on, metaverse interactions). Extending the current model to these domains would strengthen external validity and allow comparison across different levels of technological complexity and risk.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-J.K., H.-P.B. and C.-H.L.; Data curation, H.-P.B. and C.-H.L.; Formal analysis, C.-J.K. and H.-P.B.; Methodology, C.-J.K., H.-P.B. and C.-H.L.; Supervision, C.-J.K., H.-P.B. and C.-H.L.; Writing—original draft, H.-P.B. and C.-H.L.; Writing—review and editing, C.-J.K. and H.-P.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study involves an anonymous online questionnaire focusing solely on participants’ perceptions and attitudes toward AI avatar–based marketing interactions. It does not involve any medical procedures, psychological interventions, identifiable personal data, or biological specimens. All responses are collected and analyzed anonymously, and participants voluntarily consent to participate. According to the “Scope of Human Research Exempt from Ethics Committee Review” (Document No. 1010265079) issued by the Ministry of Education, and the National Taipei University of Technology Guidelines for Human Research Ethics Review, research that does not involve human trials, invasive procedures, identifiable personal data, or biological samples, and that uses only surveys, interviews, or secondary data, is exempt from ethics committee review. This study fully meets the above exemption criteria and is therefore classified as a non-interventional, exempt study under the applicable ethical regulations.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to sincerely thank the editor and reviewers for their kind comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Grewal, D.; Hulland, J.; Kopalle, P.K.; Karahanna, E. The future of technology and marketing: A multidisciplinary perspective. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waytz, A.; Cacioppo, J.; Epley, N. Who sees human? The stability and importance of individual differences in anthropomorphism. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2010, 5, 219–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundar, S.S.; Kang, J.; Oprean, D. Being there in the midst of the story: How immersive journalism affects our perceptions and cognitions. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2017, 20, 672–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKnight, D.H.; Choudhury, V.; Kacmar, C. Developing and validating trust measures for e-commerce: An integrative typology. Inf. Syst. Res. 2002, 13, 334–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauer, T.W.; Deng, X. Building online trust through privacy practices. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2007, 6, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, M.; Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. Understanding influencer marketing: The role of congruence between influencers, products and consumers. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 132, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marbach, J.; Lages, C.R.; Nunan, D. Who are you and what do you value? Investigating the role of personality traits and customer-perceived value in online customer engagement. J. Mark. Manag. 2016, 32, 502–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]