Abstract

Introduction: Food literacy (FL) is a rapidly emerging area of research that provides a framework to explain the interplay of food-related skills, beliefs, knowledge and practises that contribute to nutritional health and wellbeing. This review is the first to scope the current literature for FL interventions, assess their characteristics against the components provided in the most widely cited definition of FL. and describe their characteristics to identify gaps in the literature. Methods: This review scopes original articles describing FL interventions in the Medline, CINAHL, ProQuest Education, Web of Science and AMED databases up to August 2023. Results: Despite the heterogeneity between all seven included studies, they all demonstrated some improvements in their FL outcome measures alongside dietary intake (DI), with the greatest improvements seen in studies that employed a FL theoretical framework in intervention design. Populations at high risk of food insecurity, such as university students and people living in disadvantaged areas, were the main targets of FL interventions. Conclusion: The minimal inclusion of FL theory amongst interventions led to an overall poor coverage of essential FL components, indicating researchers should aim to design future FL interventions with a FL theoretical framework.

1. Introduction

Poor-quality dietary patterns and the rising number of diet-related diseases are prominent issues facing the health sector, with an estimated eleven million deaths worldwide attributable to dietary risk factors [1]. Interventions centred around optimising food and nutrition habits are a crucial strategy in addressing the increased burden of non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes [2,3]. However, the creation of effective dietary interventions is challenging for researchers, as there is a multitude of complex factors that influence an individual’s dietary habits.

Food literacy (FL) is one approach that provides a comprehensive framework to explain the complex interplay of food-related skills, beliefs, knowledge and practises that contribute to achieving health and wellbeing [4,5,6,7,8]. FL is a burgeoning area of research that currently lacks a universally accepted definition [9]; however, numerous definitions and frameworks have been proposed by various research teams [4,5,6,7,8]. The most popular of these definitions, as identified in a recent scoping review, were those published by Velardo, Cullen et al., Kolasa et al., and Vidgen and Gallegos, who employed various methodologies and perspectives to describe FL [4,5,6,7]. Kolasa et al. contributed one of the earliest conceptualisations of FL by adapting an established definition of health literacy which, in comparison to more modern FL frameworks, provides a one-dimensional explanation of FL that lacks a robust description of FL skills or competencies [7]. More recently, Cullen et al. applied an ecological approach to their results from a scoping review to construct their definition from a community food security and health promotion perspective [6]. Alternatively, Velardo applied Nutbeam’s tripartite model to describe the knowledge and skills encompassed in FL using three levels of literacy: functional, interactive and critical literacy [5]. While these definitions provide valuable perspectives on FL, the most popular amongst these definitions, as identified in several scoping reviews [9,10], is the one crafted by Vidgen and Gallegos, who describe FL as follows [4]:

“The scaffolding that empowers individuals, households, communities or nations to protect diet quality through change and strengthen dietary resilience over time. It is composed of a collection of inter-related knowledge, skills and behaviours required to plan, manage, select, prepare and eat food to meet needs and determine intake” [4] (p. 54).

This definition and associated framework as seen in Table 1, was developed using an iterative process involving a literature review, three-phase Delphi process and semi-structured interviews with disadvantaged young adults to describe four interconnected domains of FL: Plan and Manage, Select, Prepare and Eat [4]. These are further broken down into eleven components that describe the main elements and skills that contribute to these specific domains of FL [4].

Table 1.

The four domains and eleven components of food literacy (FL), defined by Vidgen and Gallegos [4] (p. 55).

This framework is not only the most widely cited [9,10] but is also one of the few definitions that accounts for the broadest range of food and nutrition factors influencing FL as identified in a thematic analysis of FL definitions from a scoping review [11]. A systematic review of FL definitions also highlighted the robustness of Vidgen and Gallegos’s framework by demonstrating its inclusion of all three levels of literacy, as discussed in Velardo’s definition of FL [8]. Therefore, this definition is a clear and comprehensive framework to describe FL and is a suitable benchmark in which to measure the application of the FL construct [4].

While FL is still considered an emerging area of research, it has already provided the foundation for many school-based interventions [12,13,14]. The available literature in this area has been summarised in both systematic and scoping reviews, which have identified FL programmes that create positive outcomes, such as improved food safety knowledge, cooking skills, nutrition knowledge and short-term eating behaviours [12,13,14]. Given the positive effects seen in younger populations, FL interventions have now extended to a wider range of groups, including adults, vulnerable groups and families [15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. A recent scoping review investigated both FL and nutrition literacy (NL) programmes across all age groups to describe their different theoretical frameworks, measures, results and limitations [10]. However, this review excluded people with conditions that affect their eating behaviours, such as type II diabetes, and did not differentiate between FL and NL interventions [10]. Several researchers have proposed that while NL and FL are often used interchangeably, FL encompasses a much broader set of practical and critical skills, whereas NL describes the nutritional knowledge that sits within the components of FL [5,8]. Therefore, exclusively investigating the characteristics of FL interventions and how these relate to the definition provided by Vidgen and Gallegos can provide new insights into the application of FL in a wide range of populations and help guide the future direction of this research [4].

The aim of this review is to map the current evidence relating to FL interventions, assess their characteristics against the components provided in the definition of FL provided by Vidgen and Gallegos and describe their characteristics to identify gaps in the literature [4].

- What is currently known in the literature about conducting food literacy interventions?

- What are the key characteristics of these interventions, including target population, setting and structure?

- Which components of food literacy are being targeted in these interventions and how do these align with the definition of food literacy described by Vidgen and Gallegos [4]?

- What are the current gaps in the literature relating to food literacy interventions?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol Registration

This scoping review follows the guidelines published by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) and the framework developed by Arksey and O’Malley [22,23]. The protocol for this review was published on the Open Sciences Framework https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/GY4TB (accessed on 8 August 2024).

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for this review were shaped using the Population Exposure Comparison Outcome (PECO) framework.

Studies including participants of all ages and demographics were considered, including studies targeting individuals or groups; however, studies where the population was >50% children (below 18 years of age) were excluded, as these have been the focus of previous reviews. School-based studies and animal studies were also excluded.

Interventions of interest were those that targeted FL or one of the eleven components defined in the definition of FL described by Vidgen and Gallegos [4]. Studies targeting a component of FL as part of a larger intervention were also included if the data for the FL aspect of the intervention could be isolated.

To be included, studies had to have reported a measure of FL, such as a survey or tool. Food, health and nutrition-related outcomes were also included as secondary outcome measures.

Studies published in English and from any date in peer-reviewed journals were eligible for inclusion. Interventional designs such as randomised and non-randomised control trials and pre-post studies were the focus of this review, and observational studies, study protocols and case studies where n = 1 were excluded.

2.3. Search Strategy and Database Selection

The initial search strategy was developed in consultation with a research librarian by identifying and extracting key words from the research question, objectives, aims and subsequent PECO framework. This initial search strategy was then tested in the Medline database, where it was further refined based on the results of the search. The full search strategy can be found in the Supplementary Materials (S1).

The selection of an appropriate databases and application of the final search strategy for each database was guided by the research librarian to maximise the number of relevant articles located by the search. The search was undertaken in the Medline, CINAHL, ProQuest Education, Web of Science and AMED databases, ending on 29 August 2023.

2.4. Study Selection

All results were exported to the EndNote 20 reference management software, where duplicates were removed [24]. The remaining articles were then exported to Covidence screening software [25], where two reviewers (KO, RN) independently screened all article titles and abstracts against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Conflicts between reviewers were resolved by a third reviewer (SH). The remaining articles underwent full-text screening by two reviewers (KO, SH or RN), with conflicts resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (SH). The reference lists of the included articles were also hand-searched for the identification of relevant articles.

2.5. Data Charting

Data were extracted into the data extraction table that was constructed collaboratively with all researchers. Two reviewers (KO, SH) independently extracted and charted the data using a purpose-developed extraction template in Covidence. Data extracted included the following metrics: Authors; Year of Publication; Country; Study Aim/s; Population and sample size; Setting/Context; Methods; Use of theory or framework; Structure of Intervention; Key findings; Limitations; Conclusions. The completed data extraction table can be seen in Table 2. Each included study was also mapped against the four domains and eleven components of FL described by Vidgen and Gallegos based on the content reported in their interventions (see Table 3) [4].

Table 2.

Summary and key characteristics of each included study.

Table 3.

Mapping of each FL intervention against the four domains and their respective components described in the FL framework by Vidgen and Gallegos [4].

3. Results

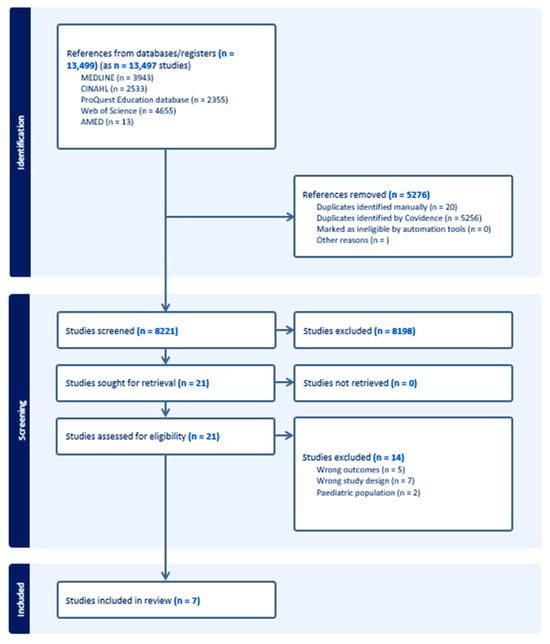

The five databases yielded 13,499 articles from the search. After 5276 duplicates were removed, 8221 articles remained for title and abstract screening. Once initial screening was completed, 21 studies underwent full-text screening, where 7 articles were included in the final data analysis. This screening process is summarised in Figure 1. During this process, two additional articles that detailed further data analysis of the results from the study by Begley et al. were identified [15,26,27]. For the purpose of this review, results from all three of these studies will be grouped together and reported as one study [15,26,27]. All included studies have been summarised in Table 2. And mapped against Vidgen and Gallegos’s FL framework in Table 3 [4].

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of search.

3.1. Setting and Structure

All studies were published on or after the year of 2020. The most common country in which these studies took place was Australia (n = 3); other countries included Germany (n = 1), Canada (n = 1), Greece (n = 1) and the United States of America (n = 1) [15,19,20]. The structure of the interventions varied widely, with three interventions consisting of weekly, face-to-face groups providing food education and practical activities [15,18,20]. Two interventions involved the use of a FL game; however, one involved a brief, one-off trial of the game and the other asked participants to use the game to plan and select their food-shopping over a three-week period [16,21]. One intervention involved a live-in wellness programme with daily education, meals, dietitian (DT) consults and practical activities [17]. Another intervention involved providing regular education materials and interactive sessions on a social media platform [19].

Most interventions took place over a 3–5-week period (n = 4) [16,17,19,20]. The intervention with the shortest duration time ran for 20 min and the longest took place over 11 weeks [18,21].

3.2. Participants

The most common target population for FL interventions was university students (n = 3) [16,18,21], followed by adults, with a specific focus on those living in middle–low-income households and socially disadvantaged areas (n = 2) [15,20]. Cohort sizes varied, with the largest study involving 1092 participants; however, these participants were combined from several intervention cohorts [15]. A majority of the studies (n = 5) featured smaller cohorts ranging from 10 to 39 participants [16,17,18,19,21].

3.3. Theoretical Foundation

Three studies used a specific FL model, theory or framework to develop the contents of their intervention [15,17,20], most commonly, the framework and definition published by Vidgen and Gallegos (n = 2) followed by the definition from Krause et al. (n = 1) [4,8,15,17,20]. One study was guided by a nutrition textbook by Sizer et al., but did not explicitly mention a FL theory or framework [16,28].

Other common theoretical frameworks that were used to develop interventions included Social Cognitive Theory (n = 3) [18,20,21], the Health Belief Model (n = 2) [15,16] and Self Determination Theory (n = 2) [20,21].

3.4. Food Literacy Measurement Tools and Outcomes

Two studies used validated FL questionnaires to assess the FL of their participants, which included a FL behaviour checklist and the Short Food Literacy Questionnaire (SFLQ) [15,17,29,30]. One study used a shortened version of the FL behaviour checklist [20]. All other studies used a combination of validated tools to create their own FL outcome measure, including two studies that used the General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire (GNKQ) combined with either the Health Belief Model Survey (HBMS) or a food safety questionnaire [16,18,19,21,31,32].

Overall, all interventions reported improvements in at least one aspect of their FL scores. Two studies using the FL behaviour checklist and one study using the SFLQ reported significant improvements comparing pre- to post-intervention mean scores for all FL domains (p ≤ 0.0001, p ≤ 0.001) and a significant improvement in overall mean scores, respectively (p < 0.0001) [15,17,20]. Another study noted improvements in 21–45% of participants on all domains of FL; however, significance was not reported [19]. One study reported improvements in two FL-based behaviours (p < 0.05) and four FL-based self-efficacy scores (p < 0.05); however, two other FL skills and three self-efficacy factors did not demonstrate improvements [18]. One study reported significant increases in their FL knowledge questionnaire (p = 0.002) and another reported significant improvements in their GNKQ scores and two domains of the HBMS (p = 0.001, p = 0.004, p = 0.015); however, when compared to the control, no significant difference was detected for either study [16,21].

Two studies assessed the long-term effects of their interventions on FL scores, with one study applying the FL behaviour checklist three months post-intervention reporting a statistically significant increase in scores for two FL domains (Plan and Manage p < 0.0001, Selection p < 0.0001) [26]. Another study demonstrated strong, significant improvements in SFLQ scores 18 months post-intervention (β = 0.55, p < 0.0001) [17].

3.5. Secondary Outcomes

DI was measured in four studies, three of which used self-reported average intakes of fruits and vegetables and the other using the German food frequency questionnaire (GFFQ) [15,17,19,20]. Overall, these measures demonstrated significant improvements, with three studies reporting significant increases in mean vegetable consumption (p ≤ 0.0001, p ≤ 0.001, p = 0.007) [15,19,20]. However, only two of these three studies identified significant improvements in fruit consumption (p ≤ 0.0001, p = 0.007) [15,19]. The study using the GFFQ reported significant improvements in overall DI [17]. Additionally, one study that tracked the food purchases of participants using their app reported significant improvements in the reduced purchasing of ultra-processed foods when compared to the control group [16]. One study also reported significant improvements in all positive parent feeding practises (p ≤ 0.001–0.003) using a bespoke questionnaire based on a validated child-feeding questionnaire [20].

3.6. Food Literacy Domains and Components

The highest-scoring domain among the interventions was Plan and Manage, which includes the component “Make feasible food decisions which balance food needs with available resources” as the only one reported by all seven interventions [15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. The Eat domain was the second highest-scoring, closely followed by Prepare. The lowest-scoring domain was Select, which also included the lowest-scoring component “Access food through multiple sources and know the advantages and disadvantages of these”.

3.7. Plan and Manage

Out of the seven studies, three included all components of this domain [15,18,20]. The component most commonly included as part of an intervention was “Make feasible food decisions which balance food needs with available resources”, which was covered by all studies [15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. “Prioritise money and time for food” was covered by the least number of studies (n = 3) [15,18,20].

3.8. Select

Out of the seven studies, only two included all components of this domain [15,19]. The component covered by the most studies (n = 6) was “Judge the quality of food” [15,16,18,19,20,21], with “Access food through multiple sources and know the advantages and disadvantages of these” included in the least number of interventions (n = 2) [15,19].

3.9. Prepare

Out of the seven studies, three included both components of this domain [14,17,19], and one study included no components of this domain [15]. The component covered by the most studies (n = 6) was “Make a good-tasting meal from whatever food is available” [14,16,17,18,19,20], followed by “Apply basic principles of safe food hygiene and handling” (n = 3) [14,17,19].

3.10. Eat

Out of the seven studies, three included all components of this domain [15,17,19]. Both “Understand food has an impact on personal wellbeing” and “Demonstrate self-awareness of the need to personally balance food intake” were the most commonly included components (n = 5) [15,16,17,19,20,21].

3.11. Interventions

The study that included the most FL domains and components was by Begley et al., which covered all four domains and eleven components in their intervention [15]. Most studies included between seven and nine components across three to four domains [17,18,19,20]. The studies with the lowest number of FL components covered in their intervention were Mitsis et al., with four components covered across four domains, and Bomfim et al., with four components across three domains [16,21].

4. Discussion

The purpose of this review is to map the current FL evidence and compare the interventions to the FL framework described by Vidgen and Gallegos [4]. This review has identified that both the characteristics and overall inclusion of the different FL domains in these studies are widely varied. The study by Begley et al. was the only one to incorporate all four FL domains and eleven components [15], followed by Tartaglia et al., who included nine components from all four domains [20]. The studies by both Morgan et al. and Ng et al. covered eight different components, closely followed by Meyn et al., who included seven components across all four domains [17,18,19]. Finally, Bomfim et al. and Mitsis et al. scored the lowest with four components; however, Bomfim et al. was the only intervention to not cover an entire domain, Prepare, in their intervention [16,21].

Firstly, this scoping review contributes to the rapidly emerging area of FL. All included studies were published within the 4 years before the search was conducted [15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. This aligns with previous research mapping the use of the term ‘food literacy’ in the academic literature, which identified 83% of all included articles published within the five years preceding their search in 2019 [9].

The lack of fidelity to Vidgen and Gallegos’s framework revealed in the mapping analysis of this review indicates that many FL interventions are likely failing to address essential FL skills, most notably, critical analysis skills [4]. The most common domain addressed in the included interventions was Plan and Manage, which included the most common component “Make feasible food decisions which balance food needs with available resources” [4]. This domain describes a person’s knowledge and skills required to plan and prioritise regular, appropriate food intake within the parameters of their individual needs and resources [4]. This requires the use of fundamental, declarative food and nutrition knowledge and then the procedural application of that knowledge [5]. Conversely, the least common domain featured in the FL interventions was Select, which included the least common component “Access food through multiple sources and know the advantages and disadvantages of these” [4]. This describes a person’s ability to access, use and critically evaluate both their food and food sources [4]. The components in this domain require further, higher-level critical analysis skills, which include the ability to critically appraise food and nutrition information, as well as awareness of the wider sociocultural and environmental impacts of food choices [4,5]. Therefore, interventions that fail to address components within the Select domain are reducing their opportunities to target these crucial, critical analysis skills. Interventions favouring simple nutrition education and skill development are also a trend that has been identified in a recent scoping review of FL and NL programmes, where the most common approaches in their included studies were nutrition education and skill-building activities [10]. This review also revealed very few included studies addressing critical components of NL and FL [10]. This further demonstrates the lack of focus on critical skill building in the current approach of FL interventions. While it is important to foster fundamental food knowledge and skills, future interventions should aim to use FL frameworks such as the one by Vidgen and Gallegos to ensure they are addressing all levels of FL, and its associated skills, comprehensively [4].

This review highlights the limited but growing body of evidence demonstrating how FL interventions produce positive food and nutrition outcomes in populations who are at high risk of food insecurity [33,34,35,36]. The populations most commonly featured in the FL interventions were university students and adults from middle–low-income households and socially disadvantaged areas [15,16,18,20,21]. These populations commonly face food insecurity and other adverse food and nutrition outcomes, with several studies linking university students to poor diet quality and low compliance with dietary guidelines [37,38,39,40]. Similar trends such as high intakes of ultra-processed foods and overall low diet quality are observed among low-income earners and people living in areas with the greatest levels of socioeconomic disadvantage [41,42,43]. Dietary interventions amongst these populations have so far achieved mixed results; one systematic review and meta-analysis examined 35 studies targeting behavioural interventions for low-income earners and found that overall effects on diet were small but positive [44]. However, when examining the relationship between socioeconomic position and healthy eating interventions, a recent review found that downstream approaches such as dietary counselling increased socioeconomic inequalities [45]. Amongst university populations, a systematic review of dietary interventions found that 13 of the successful studies focused on either self-regulation skills and nutrition education or environmental modification, such as point-of-sale messaging; however, data on the long-term outcomes of these interventions were limited [46]. This evidence indicates there is currently no optimal approach when creating well-rounded food and nutrition interventions for populations who are at high risk of food insecurity. However, this review has provided evidence that FL is one holistic approach that considers both food and wider social inequities to achieve positive outcomes in these populations [15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Given this evidence, further investigation of the benefits of taking a FL approach with other vulnerable groups experiencing complex food-related barriers, such as culturally and linguistically diverse groups or low-income earners, is warranted.

Unsurprisingly, the results of this review suggest that interventions where a FL framework was used as the theoretical foundation for study design produced stronger improvements in their FL outcomes when compared to those that did not use FL theory [15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. The studies by Begley et al. and Tartaglia et al. used the Vidgen and Gallegos FL framework and therefore score highest in the intervention mapping analysis in Table 3 [4,15,20]. The other study that utilised FL theory in their intervention was by Meyn et al., who used the definition by Krause et al., which describes an extensive list of FL components based on a systematic review of other FL definitions [8,17]. These three interventions all reported strong, significant improvements across all FL outcomes [15,17,20]. Furthermore, the studies by Begley et al. and Meyn et al. demonstrated the sustainability of these improvements at follow-ups 3–18 months post-intervention [15,17,20]. It should be noted, however, that none of these three studies included a control group [15,17,20]. Other interventions that lacked the inclusion of FL theory, such as the studies published by Mitsis et al. and Bomfim et al., scored the lowest on the mapping analysis and reported mixed results [16,21]. Both of these studies did report some improvement in their FL measures; however, they were deemed non-significant when compared to the control [16,21]. The study by Ng et al. also lacked a FL theoretical foundation but reported improvements across all FL domains; however, they failed to report the statistical significance of their outcomes [19]. The intervention by Morgan et al., who again did not include a FL framework in the development of their intervention, achieved significant improvements across some, but not all, of their FL outcome measures [18]. Overall, these results demonstrate a clear advantage in using a FL theoretical framework to construct FL interventions to produce superior outcomes; however, further interventions including control groups are also needed.

This review has many strengths, including it being the first to comprehensively scope the literature for interventions targeting FL using specific FL outcomes in a non-school-aged population. The authors complied to both the scoping review guidelines by Arksey and O’Malley and the PRISMA extension for scoping review guidelines, which supports the validity of the search and reporting of the results [22,23]. However, despite following rigorous methodology, the following limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this review. As FL is an emerging area of research, this review only included a small number of studies. Furthermore, many of the key characteristics such as the setting, structure, theoretical basis and measurement tools used to assess FL varied between interventions. These differences, particularly differences in the theoretical basis of FL used to score participants, limits the comparability of outcomes across studies. Additionally, some studies also lacked detailed reporting of their interventions, which led to difficulties when interpreting and mapping the intervention components.

5. Conclusions

This review identified some common trends within FL interventions such as small cohort sizes, three- to five-week durations and a focus on populations who are at high risk of food insecurity; however, the study characteristics were largely heterogenous, which limited the comparability of outcome measures between studies. Despite this, all studies achieved some improvement in their FL outcome measures with DI, particularly vegetable intake, also seeing significant improvements across most studies [15,16,17,18,19,20,21]. Furthermore, the few studies that reported follow-up measures demonstrated long-term improvements for most FL and some dietary outcome measures [17,26]. The mapping analysis revealed that most interventions failed to comprehensively cover all FL domains and components included in the Vidgen and Gallegos framework, meaning crucial FL skills, such as critical analysis skills, were not being adequately addressed [4]. Interventions that were designed using a FL theoretical framework or definition were in the minority; however, those that did appeared to yield stronger FL outcomes [15,17,20]. This demonstrates the need for future FL interventions to be designed using a robust FL framework, such as the Vidgen and Gallegos framework, to ensure they encompass the wide range of knowledge and practical skills needed to comprehensively promote FL. These interventions should include validated FL measurement tools to ensure that all aspects of FL are being captured and assessed. Further studies should also aim to work with disadvantaged populations at high risk of food insecurity, have larger cohort sizes, include long-term follow-up measures and include control groups to confirm and further explore the benefits of this area of research.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nu16183171/s1, Table S1: Full search strategy for all databases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, K.O., S.E.H. and L.M.-W.; methodology, K.O., S.E.H. and L.M.-W.; formal analysis, K.O. and S.E.H.; investigation, K.O. and S.E.H.; resources, S.E.H. and L.M.-W.; data curation, K.O. and S.E.H.; writing—original draft preparation, K.O.; writing—review and editing, K.O., S.E.H. and L.M.-W.; visualisation, K.O., S.E.H. and L.M.-W.; supervision, S.E.H. and L.M.-W.; project administration, K.O.; funding acquisition, K.O. and L.M.-W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. KO is undertaking her PhD (Nutrition and Dietetics) at the University of Newcastle and is supported by a University of Newcastle research training scholarship.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article and Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rachel Naylor for assistance with article-screening and full-text review. We also thank Nicole Faull-Brown (research liaison librarian) for her assistance with developing and conducting the database searches.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| FL | food literacy |

| NL | nutrition literacy |

References

- Afshin, A.; Sur, P.J.; Fay, K.A.; Cornaby, L.; Ferrara, G.; Salama, J.S.; Mullany, E.C.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abebe, Z.; et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar]

- Abbate, M.; Gallardo-Alfaro, L.; Bibiloni, M.D.M.; Tur, J.A. Efficacy of dietary intervention or in combination with exercise on primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 30, 1080–1093. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Hur, M.H. The Effects of Dietary Education Interventions on Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidgen, H.A.; Gallegos, D. Defining food literacy and its components. Appetite 2014, 76, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velardo, S. The Nuances of Health Literacy, Nutrition Literacy, and Food Literacy. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2015, 47, 385–389 e1. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, T.; Hatch, J.; Martin, W.; Higgins, J.W.; Sheppard, R. Food Literacy: Definition and Framework for Action. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2015, 76, 140–145. [Google Scholar]

- Kolasa, K.M.; Peery, A.; Harris, N.G.; Shovelin, K. Food Literacy Partners Program: A Strategy To Increase Community Food Literacy. Top. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, C.; Sommerhalder, K.; Beer-Borst, S.; Abel, T. Just a subtle difference? Findings from a systematic review on definitions of nutrition literacy and food literacy. Health Promot. Int. 2018, 33, 378–389. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, C.; Adams, J.; Vidgen, H.A. Are We Closer to International Consensus on the Term ‘Food Literacy’? A Systematic Scoping Review of Its Use in the Academic Literature (1998–2019). Nutrients 2021, 13, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezas, M.-F.; Nazar, G. A scoping review of food and nutrition literacy programs. Health Promot. Int. 2023, 38, daad090. [Google Scholar]

- Truman, E.; Lane, D.; Elliott, C. Defining food literacy: A scoping review. Appetite 2017, 116, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickham, C.A.; Carbone, E.T. What’s technology cooking up? A systematic review of the use of technology in adolescent food literacy programs. Appetite 2018, 125, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, C.J.; Drummond, M.J.; Ward, P.R. Food literacy programmes in secondary schools: A systematic literature review and narrative synthesis of quantitative and qualitative evidence. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 2891–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, R.K.; Nash, R. Food Literacy Interventions in Elementary Schools: A Systematic Scoping Review. J. Sch. Health 2021, 91, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begley, A.; Paynter, E.; Butcher, L.M.; Dhaliwal, S.S. Effectiveness of an Adult Food Literacy Program. Nutrients 2019, 11, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomfim, M.C.C.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Nacke, L.E.; Wallace, J.R. Food Literacy while Shopping: Motivating Informed Food Purchasing Behaviour with a Situated Gameful App. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Meyn, S.; Blaschke, S.; Mess, F. Food Literacy and Dietary Intake in German Office Workers: A Longitudinal Intervention Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 16534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.; Arrowood, J.; Farris, A.; Griffin, J. Assessing food security through cooking and food literacy among students enrolled in a basic food science lab at Appalachian State University. J. Am. Coll. Health 2023, 71, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.H.; ElGhattis, Y.; Biesiekierski, J.R.; Moschonis, G. Assessing the effectiveness of a 4-week online intervention on food literacy and fruit and vegetable consumption in Australian adults: The online MedDiet challenge. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e4975–e4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartaglia, J.; Jancey, J.; Scott, J.A.; Dhaliwal, S.S.; Begley, A. Effectiveness of a food literacy and positive feeding practices program for parents of 0 to 5 years olds in Western Australia. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2023, 35, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsis, K.; Zarkogianni, K.; Dalakleidi, K.V.; Mourkousis, G.; Nikita, K.S. Evaluation of a Serious Game Promoting Nutrition and Food Literacy: Experiment Design and Preliminary Results. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 19th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Bioengineering (BIBE) 2019, Athens, Greece, 28–30 October 2019; pp. 497–502. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O′Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The EndNote Team. Endnote [Software], EndNote 20 ed.; Clarivate: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence Systematic Review [Software]; Veritas Health Innovation: Melbourne, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Begley, A.; Paynter, E.; Butcher, L.; Bobongie, V.; Dhaliwal, S.S. Identifying Who Improves or Maintains Their Food Literacy Behaviours after Completing an Adult Program. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 4462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumont, C.; Butcher, L.M.; Foulkes-Taylor, F.; Bird, A.; Begley, A. Effectiveness of Foodbank Western Australia’s Food Sensations(®) for Adults Food Literacy Program in Regional Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sizer, F.W.E. Nutrition: Concepts and Controversies, 4th ed.; Nelson College Indigenous: Nelson, New Zealand, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gréa Krause, C.; Beer-Borst, S.; Sommerhalder, K.; Hayoz, S.; Abel, T. A short food literacy questionnaire (SFLQ) for adults: Findings from a Swiss validation study. Appetite 2018, 120, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begley, A.; Paynter, E.; Dhaliwal, S.S. Evaluation Tool Development for Food Literacy Programs. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliemann, N.; Wardle, J.; Johnson, F.; Croker, H. Reliability and validity of a revised version of the General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, R. The health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 354–386. [Google Scholar]

- Butcher, L.M.; Platts, J.R.; Le, N.; McIntosh, M.M.; Celenza, C.A.; Foulkes-Taylor, F. Can addressing food literacy across the life cycle improve the health of vulnerable populations? A case study approach. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2021, 32, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, E.G.; Lindberg, R.; Ball, K.; McNaughton, S.A. The Role of a Food Literacy Intervention in Promoting Food Security and Food Literacy-OzHarvest’s NEST Program. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, R.L.; Maulding, M.K.; Abbott, A.R.; Craig, B.A.; Eicher-Miller, H.A. SNAP-Ed (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program-Education) Increases Long-Term Food Security among Indiana Households with Children in a Randomized Controlled Study. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 2375–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, T.P.; Jayasinghe, S.; Dalton, L.; Kilpatrick, M.L.; Hughes, R.; Patterson, K.A.E.; Soward, R.; Burgess, K.; Byrne, N.M.; Hills, A.P.; et al. Enhancing Food Literacy and Food Security through School Gardening in Rural and Regional Communities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruening, M.; Argo, K.; Payne-Sturges, D.; Laska, M.N. The Struggle Is Real: A Systematic Review of Food Insecurity on Postsecondary Education Campuses. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 1767–1791. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Grech, A.; Allman-Farinelli, M. Diet Quality among Students Attending an Australian University Is Compromised by Food Insecurity and Less Frequent Intake of Home Cooked Meals. A Cross-Sectional Survey Using the Validated Healthy Eating Index for Australian Adults (HEIFA-2013). Nutrients 2022, 14, 4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramón-Arbués, E.; Granada-López, J.M.; Martínez-Abadía, B.; Echániz-Serrano, E.; Antón-Solanas, I.; Jerue, B.A. Factors Related to Diet Quality: A Cross-Sectional Study of 1055 University Students. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosier, K. Food Insecurity in Australia: What Is It, Who Experiences It and How Can Child and Family Services Support Families Experiencing It? Australian Institute of Family Studies: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- French, S.A.; Tangney, C.C.; Crane, M.M.; Wang, Y.; Appelhans, B.M. Nutrition quality of food purchases varies by household income: The SHoPPER study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, L.; Livingstone, K.M.; Woods, J.L.; Wingrove, K.; Machado, P. Ultra-processed food consumption, socio-demographics and diet quality in Australian adults. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancino, L.; Guthrie, J.; Ver Ploeg, M.; Lin, B.H. Nutritional Quality of Foods Acquired by Americans: Findings from USDA’s National Household Food Acquisition and Purchase Survey; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, E.R.; Dombrowski, S.U.; McCleary, N.; Johnston, M. Are interventions for low-income groups effective in changing healthy eating, physical activity and smoking behaviours? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e006046. [Google Scholar]

- McGill, R.; Anwar, E.; Orton, L.; Bromley, H.; Lloyd-Williams, F.; O’flaherty, M.; Taylor-Robinson, D.; Guzman-Castillo, M.; Gillespie, D.; Moreira, P.; et al. Are interventions to promote healthy eating equally effective for all? Systematic review of socioeconomic inequalities in impact. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 457. [Google Scholar]

- Deliens, T.; Van Crombruggen, R.; Verbruggen, S.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Deforche, B.; Clarys, P. Dietary interventions among university students: A systematic review. Appetite 2016, 105, 14–26. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).