A Scoping Review of Food Literacy Interventions

Abstract

1. Introduction

- What is currently known in the literature about conducting food literacy interventions?

- What are the key characteristics of these interventions, including target population, setting and structure?

- Which components of food literacy are being targeted in these interventions and how do these align with the definition of food literacy described by Vidgen and Gallegos [4]?

- What are the current gaps in the literature relating to food literacy interventions?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol Registration

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy and Database Selection

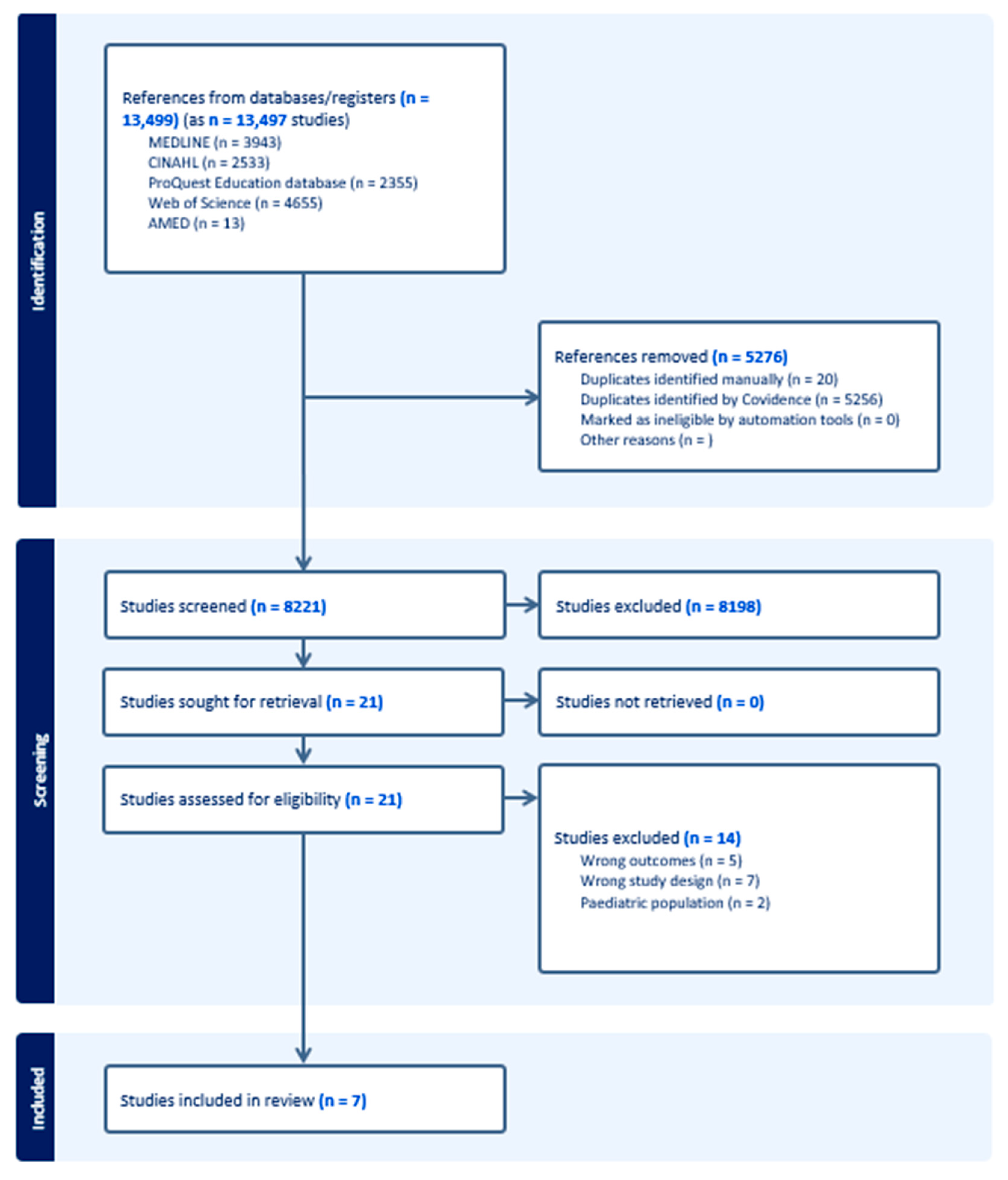

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Data Charting

3. Results

3.1. Setting and Structure

3.2. Participants

3.3. Theoretical Foundation

3.4. Food Literacy Measurement Tools and Outcomes

3.5. Secondary Outcomes

3.6. Food Literacy Domains and Components

3.7. Plan and Manage

3.8. Select

3.9. Prepare

3.10. Eat

3.11. Interventions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FL | food literacy |

| NL | nutrition literacy |

References

- Afshin, A.; Sur, P.J.; Fay, K.A.; Cornaby, L.; Ferrara, G.; Salama, J.S.; Mullany, E.C.; Abate, K.H.; Abbafati, C.; Abebe, Z.; et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2019, 393, 1958–1972. [Google Scholar]

- Abbate, M.; Gallardo-Alfaro, L.; Bibiloni, M.D.M.; Tur, J.A. Efficacy of dietary intervention or in combination with exercise on primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 30, 1080–1093. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Hur, M.H. The Effects of Dietary Education Interventions on Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidgen, H.A.; Gallegos, D. Defining food literacy and its components. Appetite 2014, 76, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velardo, S. The Nuances of Health Literacy, Nutrition Literacy, and Food Literacy. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2015, 47, 385–389 e1. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, T.; Hatch, J.; Martin, W.; Higgins, J.W.; Sheppard, R. Food Literacy: Definition and Framework for Action. Can. J. Diet. Pract. Res. 2015, 76, 140–145. [Google Scholar]

- Kolasa, K.M.; Peery, A.; Harris, N.G.; Shovelin, K. Food Literacy Partners Program: A Strategy To Increase Community Food Literacy. Top. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, C.; Sommerhalder, K.; Beer-Borst, S.; Abel, T. Just a subtle difference? Findings from a systematic review on definitions of nutrition literacy and food literacy. Health Promot. Int. 2018, 33, 378–389. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, C.; Adams, J.; Vidgen, H.A. Are We Closer to International Consensus on the Term ‘Food Literacy’? A Systematic Scoping Review of Its Use in the Academic Literature (1998–2019). Nutrients 2021, 13, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezas, M.-F.; Nazar, G. A scoping review of food and nutrition literacy programs. Health Promot. Int. 2023, 38, daad090. [Google Scholar]

- Truman, E.; Lane, D.; Elliott, C. Defining food literacy: A scoping review. Appetite 2017, 116, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickham, C.A.; Carbone, E.T. What’s technology cooking up? A systematic review of the use of technology in adolescent food literacy programs. Appetite 2018, 125, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, C.J.; Drummond, M.J.; Ward, P.R. Food literacy programmes in secondary schools: A systematic literature review and narrative synthesis of quantitative and qualitative evidence. Public Health Nutr. 2019, 22, 2891–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, R.K.; Nash, R. Food Literacy Interventions in Elementary Schools: A Systematic Scoping Review. J. Sch. Health 2021, 91, 660–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begley, A.; Paynter, E.; Butcher, L.M.; Dhaliwal, S.S. Effectiveness of an Adult Food Literacy Program. Nutrients 2019, 11, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomfim, M.C.C.; Kirkpatrick, S.I.; Nacke, L.E.; Wallace, J.R. Food Literacy while Shopping: Motivating Informed Food Purchasing Behaviour with a Situated Gameful App. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Honolulu, HI, USA, 25–30 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Meyn, S.; Blaschke, S.; Mess, F. Food Literacy and Dietary Intake in German Office Workers: A Longitudinal Intervention Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2022, 19, 16534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.; Arrowood, J.; Farris, A.; Griffin, J. Assessing food security through cooking and food literacy among students enrolled in a basic food science lab at Appalachian State University. J. Am. Coll. Health 2023, 71, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, A.H.; ElGhattis, Y.; Biesiekierski, J.R.; Moschonis, G. Assessing the effectiveness of a 4-week online intervention on food literacy and fruit and vegetable consumption in Australian adults: The online MedDiet challenge. Health Soc. Care Community 2022, 30, e4975–e4981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartaglia, J.; Jancey, J.; Scott, J.A.; Dhaliwal, S.S.; Begley, A. Effectiveness of a food literacy and positive feeding practices program for parents of 0 to 5 years olds in Western Australia. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2023, 35, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsis, K.; Zarkogianni, K.; Dalakleidi, K.V.; Mourkousis, G.; Nikita, K.S. Evaluation of a Serious Game Promoting Nutrition and Food Literacy: Experiment Design and Preliminary Results. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 19th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Bioengineering (BIBE) 2019, Athens, Greece, 28–30 October 2019; pp. 497–502. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O′Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The EndNote Team. Endnote [Software], EndNote 20 ed.; Clarivate: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence Systematic Review [Software]; Veritas Health Innovation: Melbourne, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Begley, A.; Paynter, E.; Butcher, L.; Bobongie, V.; Dhaliwal, S.S. Identifying Who Improves or Maintains Their Food Literacy Behaviours after Completing an Adult Program. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 4462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumont, C.; Butcher, L.M.; Foulkes-Taylor, F.; Bird, A.; Begley, A. Effectiveness of Foodbank Western Australia’s Food Sensations(®) for Adults Food Literacy Program in Regional Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sizer, F.W.E. Nutrition: Concepts and Controversies, 4th ed.; Nelson College Indigenous: Nelson, New Zealand, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gréa Krause, C.; Beer-Borst, S.; Sommerhalder, K.; Hayoz, S.; Abel, T. A short food literacy questionnaire (SFLQ) for adults: Findings from a Swiss validation study. Appetite 2018, 120, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begley, A.; Paynter, E.; Dhaliwal, S.S. Evaluation Tool Development for Food Literacy Programs. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kliemann, N.; Wardle, J.; Johnson, F.; Croker, H. Reliability and validity of a revised version of the General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, R. The health belief model and preventive health behavior. Health Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 354–386. [Google Scholar]

- Butcher, L.M.; Platts, J.R.; Le, N.; McIntosh, M.M.; Celenza, C.A.; Foulkes-Taylor, F. Can addressing food literacy across the life cycle improve the health of vulnerable populations? A case study approach. Health Promot. J. Aust. 2021, 32, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, E.G.; Lindberg, R.; Ball, K.; McNaughton, S.A. The Role of a Food Literacy Intervention in Promoting Food Security and Food Literacy-OzHarvest’s NEST Program. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, R.L.; Maulding, M.K.; Abbott, A.R.; Craig, B.A.; Eicher-Miller, H.A. SNAP-Ed (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program-Education) Increases Long-Term Food Security among Indiana Households with Children in a Randomized Controlled Study. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 2375–2382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, T.P.; Jayasinghe, S.; Dalton, L.; Kilpatrick, M.L.; Hughes, R.; Patterson, K.A.E.; Soward, R.; Burgess, K.; Byrne, N.M.; Hills, A.P.; et al. Enhancing Food Literacy and Food Security through School Gardening in Rural and Regional Communities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruening, M.; Argo, K.; Payne-Sturges, D.; Laska, M.N. The Struggle Is Real: A Systematic Review of Food Insecurity on Postsecondary Education Campuses. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 1767–1791. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Grech, A.; Allman-Farinelli, M. Diet Quality among Students Attending an Australian University Is Compromised by Food Insecurity and Less Frequent Intake of Home Cooked Meals. A Cross-Sectional Survey Using the Validated Healthy Eating Index for Australian Adults (HEIFA-2013). Nutrients 2022, 14, 4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramón-Arbués, E.; Granada-López, J.M.; Martínez-Abadía, B.; Echániz-Serrano, E.; Antón-Solanas, I.; Jerue, B.A. Factors Related to Diet Quality: A Cross-Sectional Study of 1055 University Students. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosier, K. Food Insecurity in Australia: What Is It, Who Experiences It and How Can Child and Family Services Support Families Experiencing It? Australian Institute of Family Studies: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- French, S.A.; Tangney, C.C.; Crane, M.M.; Wang, Y.; Appelhans, B.M. Nutrition quality of food purchases varies by household income: The SHoPPER study. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchese, L.; Livingstone, K.M.; Woods, J.L.; Wingrove, K.; Machado, P. Ultra-processed food consumption, socio-demographics and diet quality in Australian adults. Public Health Nutr. 2022, 25, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancino, L.; Guthrie, J.; Ver Ploeg, M.; Lin, B.H. Nutritional Quality of Foods Acquired by Americans: Findings from USDA’s National Household Food Acquisition and Purchase Survey; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, E.R.; Dombrowski, S.U.; McCleary, N.; Johnston, M. Are interventions for low-income groups effective in changing healthy eating, physical activity and smoking behaviours? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e006046. [Google Scholar]

- McGill, R.; Anwar, E.; Orton, L.; Bromley, H.; Lloyd-Williams, F.; O’flaherty, M.; Taylor-Robinson, D.; Guzman-Castillo, M.; Gillespie, D.; Moreira, P.; et al. Are interventions to promote healthy eating equally effective for all? Systematic review of socioeconomic inequalities in impact. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 457. [Google Scholar]

- Deliens, T.; Van Crombruggen, R.; Verbruggen, S.; De Bourdeaudhuij, I.; Deforche, B.; Clarys, P. Dietary interventions among university students: A systematic review. Appetite 2016, 105, 14–26. [Google Scholar]

| 1. Plan and Manage | 2. Select | 3. Prepare | 4. Eat |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Prioritise money and time for food. 1.2 Plan food intake (formally and informally) so that food can be regularly accessed through some source, irrespective of changes in circumstance or environment. 1.3 Make feasible food decisions which balance food needs (e.g., nutrition, taste, hunger) with available resources (e.g., time, money, skills, equipment). | 2.1 Access food through multiple sources and know the advantages and disadvantages of these. 2.2 Determine what is in a food product, where it came from, how to store it and how to use it. 2.3 Judge the quality of food. | 3.1 Make a good-tasting meal from whatever food is available. This includes being able to prepare commonly available foods, efficiently using common pieces of kitchen equipment and having a sufficient repertoire of skills to adapts recipes (written or unwritten) to experiment with food and ingredients. 3.2 Apply basic principles of safe food hygiene and handling. | 4.1 Understand that food has an impact on personal wellbeing. 4.2 Demonstrate self-awareness of the need to personally balance food intake. This includes knowing foods to include for good health, foods to restrict for good health, and appropriate portion size frequency. 4.3 Join in and eat in a social way. |

| Lead Author and Year Title Country | Study Design Aim | Participants Sample Size Setting | Theoretical Basis | Structure Duration | Food Literacy Outcome Measure | Secondary Outcome Measures | Results: Primary Outcome | Results: Secondary Outcome | Study Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Begley 2019 Effectiveness of an Adult Food Literacy Program [15] Australia | Pre-post study Assess how effective the Food Sensation for Adults programme is in changing FL and selected dietary behaviours. | Adults from low–middle-income households who would like to increase their FL skills n = 1092 Community-based groups and virtual sessions for regional areas | Vidgen and Gallegos FL model (Vidgen and Gallegos, 2014), Best Practice Criteria for Food Literacy Programs (WA Department of Health), Health Belief Model, Social Learning Theory | I = 2.5 hr sessions. Four core modules (healthy eating, food safety, cooking, label reading, food selection, budgeting, and meal planning) taught over 3 sessions. Recipe book provided to all participants. Four sessions | Validated pre/post-programme questionnaires: 14-item FL behaviour checklist. | Four close-ended questions on dietary behaviours: average consumption of fruit and vegetable servings, frequency of fast food meals and sugar-sweetened drink consumption (self-reported) | Significant ↑ in all three assessed FL behaviour factors (all p ≤ 0.0001) from pre- to post-programme. | Significant ↑ in servings of fruits (p ≤ 0.0001) and vegetables (p ≤ 0.0001), comparing pre- to post-programme. Significant decreases in fast food meal consumption pre- to post-programme. | Self-selection bias, number of questions assessing domains of FL were limited, potential that culturally and linguistically diverse populations not represented in evaluations, self-reported data, no control |

| Begley 2020 Identifying who improves or maintains their food literacy behaviours after completing an adult program [26] | Cross-sectional Compare demographic characteristics of participants who completed the programme’s follow-up questionnaire three months after programme completion and assess whether FL and dietary behaviour changes were improved or maintained | n = 621 | Mean scores for 2 of the 3 domains significantly ↑ (Plan and Manage, p < 0.0001. Selection, <0.0001) from end-of-programme to follow-up. Preparation scores decreased but remained significantly ↑ from baseline. | Servings of fruit and veg decreased but remained significantly ↑ from baseline. Intake of fast food meals significantly ↑ between end-of-programme and follow-up (p < 0.0001), consumption frequency decreased from beginning of programme (p < 0.0001). No change in frequency of sugar-sweetened drinks. | Unknown what the ideal time for follow-up is; the demographic characteristics of those completing the follow-up questionnaires are different. | ||||

| Dumont, C 2021 Effectiveness of Foodbank Western Australia’s Food Sensations ® for Adults food literacy program in regional Australia [27] | Cross-sectional Determine if there are differences in the effectiveness of FSA in regional and metropolitan (metro) participants | n = 1849 | Significant ↑ in post-programme scores for all three FL domains for metro and regional (p < 0.0001). Regional significantly ↑ in selection behaviours compared to metro (p < 0.01). No significant difference between metro and regional in other 2 domains | Significant ↑ (p < 0.0001) in fruit and vegetable serving intake for metro and regional. Fast food meal and sweetened beverage intake significantly decreased pre- and post-programme for metro (p < 0.0001), but not for regional. | May not have captured the full range of disadvantage in regional areas in Western Australia | ||||

| Bomfim 2020 Food Literacy while Shopping: Motivating Informed Food Purchasing Behaviour with a Situated Gameful App [16] Canada | Other: Exploratory Field Study To investigate the effectiveness of a gameful-situated app ‘Pirate Bri’s Grocery Adventure’ (PBGA) to promote FL in young adults | University students 18–31 Y n = 24: 2x cohorts of 12 Use of app during shopping trips for groceries | Nutrition: concepts and controversies (4th ed) (Sizer et al.), Meaningful gamification, slow technology, Health Belief Model | I = PBGA app C = My Food Guide app Both groups used app to plan and select foods for 3 weeks on minimum 3 different days 3 weeks | General Nutrition Knowledge Questionnaire (GNKQ) and Health Belief Model Survey (HBMS) | Food Purchases | GNKQ: Average scores ↑ 55.17/88 to 59.38/88 from pre- to post-intervention, p = 0.001. No differences in post-intervention scores between I and C (p> 0.005). HBMS: ↑ from pre- to post-intervention scores for self-efficacy (p = 0.004) and perceived susceptibility (p = 0.015). No significant difference between scores for I and C for all sections of HBMS. | ↑ in fruit and veg (p = 0.004) purchased compared to what was planned, no difference between I and C. ↑ in ultra-processed foods bought compared to planned for C (p = 0.13), but not for I. | Does not provide insight into clinical effectiveness to promote FL; budgeting not addressed |

| Tartaglia 2023 Effectiveness of a food literacy and positive feeding practices program for parents of 0 to 5 years olds in Western Australia [20] Australia | Pre-post study To describe the development and evaluation of an innovative programme that combines FL with positive parent feeding practises, targeting parents indisadvantaged areas of Western Australia | Parents of children 0–5 years in Western Australia, particularly those in socially disadvantaged areas >18 Y n = 224 Community and online group sessions | Vidgen and Gallegos FL model (Vidgen and Gallegos, 2014), Satter eating competence model, division of responsibility framework, self-determination theory framework, social cognitive theory (SCT) | I = Weekly education and cooking sessions on basic nutrition principles for the whole family, child-feeding development stages, strategies to overcome fussy eating, food safety, label reading, meal planning, food shopping and budgeting. Includes 60 min hands-on learning, 60 min cooking and 30 min eating. Face-to-face: 5 weeks Online: 4 weeks | Pre- and post-questionnaire comprised 13 items from a 15-item validated FL tool | Positive parent feeding practises: 10 questions from validated child-feeding questionnaires, including the Feeding Practices and Structure Questionnaire. Typical vegetable intake over previous month | Statistically significant ↑ in all FL behaviours (p ≤ 0.001) | Significant ↑ in all positive parent feeding practises (p ≤ 0.001–0.003). Significant mean ↑ in vegetable intake (p = 0.001) | Higher rate of females (98%); change to online delivery may have resulted in people from higher socioeconomic areas being recruited. |

| Morgan 2023 Assessing food security through cooking and food literacy among students enrolled in a basic food science lab at Appalachian State University [18] United States | Pre-post study Implement a FL-based curriculum to increase FL-based skills and self-efficacy and combat food insecurity among undergraduate students enrolled in an already-established Basic Food Science Laboratory course at a rural university located in the Appalachian region | University students n = 39 University course | SCT, experiential learning theory | I = University food science course including labs involving observation and hands-on food preparation, food safety, budgeting education and eating 11 weeks | Purpose-developed questionnaire based on a variety of validated instruments | Food security: modified version of the USDA Six Item Food Security Short Form | Significant ↑ from pre- to post-assessment for FL-based behaviours (p < 0.05): preparing and cooking a meal with raw ingredients (p = 0.039), proper food storage (p = 0.046) and FL-based self-efficacy: Using different cooking methods, (p = 0.037), cooking with raw or basic ingredients (p = 0.003), preparing a well-balanced meal (p = 0.018), using substitutions in recipes (p = 0.000) and meal planning (p = 0.009). Two FL skills and three self-efficacy factors did not see a significant improvement. | No significant improvement in food security indicators | Short study length, small sample size, generalizability not tested, low number of behaviour-focused questions, self-report measures, significant proportion of included participants were dietitian (DT) and fermentation students |

| Mitsis 2019 Evaluation of a Serious Game promoting Nutrition and Food Literacy: Experiment Design and Preliminary Results [21] Greece | Quasi-experimental trial Present the experiment design and the obtained preliminary results from the evaluation of Express Cooking Train, a serious game that focuses on promoting nutrition literacy (NL) and FL | University students n = 29: Group A 9, Group B 10, Control 10 Trial of computer game | World Health Organisation and the American Heart Association fact sheets | I = FL game with two stages. User experiments with ingredients and progresses in the game when preparing healthy meals. C = Reading nutrition fact sheets 20 min | Knowledge questionnaire based on the (GNKQ) and a validated food safety knowledge questionnaire. | NA | Significant ↑ in pre- to post-intervention knowledge questionnaire scores (p = 0.002). No significant difference between C and I group post-intervention scores. | NA | Small sample size, control game was a different format |

| Ng 2022 Assessing the effectiveness of a 4-week online intervention on food literacy and fruit and vegetable consumption in Australian adults: The online MedDiet challenge [19] Australia | Pre-post study Develop and trial an online intervention programme to improve FL and fruit and vegetable intake through the use of MedDiet principles | Members of the GMHBA private health insurance provider from Victoria >18 Y n = 29 Facebook group | NA | I = Moderators shared nutrition education and encouraged Mediterranean-style eating via infographics 3x per week, how-to-videos 1x per week and recipes 1x per week. Fortnightly Q&A with nutrition experts on a Facebook group. Participants received a box of MedDiet staple ingredients, recipes and cooking ideas. 28 days | Modified version of validated 11-item FL questionnaire from the EFNEP | Average daily fruit and veg consumption: two questions from the National Nutrition Survey | Percentage of participants ↑ in all 11 FL components ranging from 20.7 to 44.8%: comparing prices (20.7%), changing recipes (24.1%), trying a new recipe (24.1%), confidence with cooking variety (31%), food labels (27.6%), nutrition information panel (34.5%), managing money to buy healthy food (31%), consideration of healthy choices (27.6%), including food groups (44.8%), making shopping lists (27.6%), planning meals (20.7%) | Statistically significant ↑ in mean fruit (p = 0.021) and veg intake (p = 0.007). | Small sample size compared to power calculation, majority tertiary-educated population, sample recruited from staff/members of private health insurer, self-report bias |

| Meyn 2022 Food Literacy and Dietary Intake in German Office Workers: A Longitudinal Intervention Study [17] Germany | Longitudinal Intervention Study Investigate the 1.5-year long-term effectiveness of a 3-week full-time workplace health-promotion programme (WHPP) regarding FL and dietary intake (DI), as well as therelation between FL and DI of German office workers using four measurement time points. | Adult office workers n = 144 WHPP based at a hotel | FL definition by Krause et al. 2018, Information–motivation–behaviour skills model | I = Groups provided initial and long-term goal-setting with a DT, provided meals with nutrition information and portion sizing guide with DT present, 4 hr nutrition education workshop and individual sessions by DT, behaviour change and health risk presentations, nutrient tables and recipes to take home 3 weeks | Short Food Literacy Questionnaire (SFLQ) adapted to German. Measured pre- (T0) and post (T1)-intervention, 6 (T2) and 18 months (T3) post-intervention | DI: German Food Frequency Questionnaire (GFFQ) | Strong ↑ in FL at T1 (β = 0.52, p < 0.0001), T2 (β = 0.60, p < 0.0001) and T3 (β = 0.55, p < 0.0001). | DI scores ↑ from 13.7 at T0 to 19.3 at T1, then decreased to 15.4 at T2 and 15.3 at T3. Significant ↑ at T1 (β = 0.63, p < 0.0001) and weak ↑ at T2 (β = 0.10, p < 0.05) and T3 (β = 0.10, p < 0.05) | No control/comparison, self-reported measures, T3 and T4 recorded during COVID-19, primarily highly educated population, narrow focus on FL for their specific study aim |

| First Author, Year | Begley, A, 2019 [14] | Bomfim, M, 2020 [15,16] | Meyn, S, 2022 [16] | Mitsis, K, 2019 [20] | Morgan, M, 2023 [17] | Ng, Ashley, 2022 [18] | Tartaglia, J, 2023 [20] | Total Components Included across all Interventions for Each Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Plan and Manage | ||||||||

| 1.1 Prioritise money and time for food |  | 0 | 0 | 0 |  | 0 |  | |

| 1.2 Plan food intake |  |  |  | 0 |  | 0 |  | |

| 1.3 Make feasible food decisions which balance food needs with available resources |  |  |  |  |  |  |  | |

| Total included for Plan and Manage domain | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 15/21 |

| 2. Select | ||||||||

| 2.1 Access food through multiple sources and know the advantages and disadvantages of these |  | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |  | 0 | |

| 2.2 Determine what is in a food product, where it came from, how to store it and how to use it |  | 0 |  | 0 |  |  |  | |

| 2.3 Judge the quality of food |  |  | 0 |  |  |  |  | |

| Total included for Select domain | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 13/21 |

| 3. Prepare | ||||||||

| 3.1 Make a good-tasting meal from whatever food is available. |  | 0 |  |  |  |  |  | |

| 3.2 Apply basic principles of safe food hygiene and handling |  | 0 | 0 | 0 |  | 0 |  | |

| Total included for Prepare domain | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 9/14 |

| 4. Eat | ||||||||

| 4.1 Understand food has an impact on personal wellbeing |  |  |  | 0 | 0 |  |  | |

| 4.2 Demonstrate self-awareness of the need to personally balance food intake. |  | 0 |  |  | 0 |  |  | |

| 4.3 Join in and eat in a social way |  | 0 |  | 0 |  |  | 0 | |

| Total included for Eat domain | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 14/21 |

| TOTAL COMPONENTS | 11 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 9 | |

= Theory and education were included for that component, e.g., informative presentations, written educations materials provided.

= Theory and education were included for that component, e.g., informative presentations, written educations materials provided.  = Skill development and practical activities for that component were included, e.g., cooking classes, label-reading activities. 0 = Component was not covered as part of the intervention. Numerals refer to the number of components covered by an intervention for each domain and the total number of components covered out of 11. A tally is also provided for the total number of components covered in each domain across all interventions. The tally provides a score out of 21 for the Plan and Manage, Select and Eat domains, and out 14 for the Prepare domain.

= Skill development and practical activities for that component were included, e.g., cooking classes, label-reading activities. 0 = Component was not covered as part of the intervention. Numerals refer to the number of components covered by an intervention for each domain and the total number of components covered out of 11. A tally is also provided for the total number of components covered in each domain across all interventions. The tally provides a score out of 21 for the Plan and Manage, Select and Eat domains, and out 14 for the Prepare domain.Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

O’Brien, K.; MacDonald-Wicks, L.; Heaney, S.E. A Scoping Review of Food Literacy Interventions. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3171. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16183171

O’Brien K, MacDonald-Wicks L, Heaney SE. A Scoping Review of Food Literacy Interventions. Nutrients. 2024; 16(18):3171. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16183171

Chicago/Turabian StyleO’Brien, Keely, Lesley MacDonald-Wicks, and Susan E. Heaney. 2024. "A Scoping Review of Food Literacy Interventions" Nutrients 16, no. 18: 3171. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16183171

APA StyleO’Brien, K., MacDonald-Wicks, L., & Heaney, S. E. (2024). A Scoping Review of Food Literacy Interventions. Nutrients, 16(18), 3171. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu16183171