Abstract

Disordered eating, or abnormal eating behaviours that do not meet the criteria for an independent eating disorder, have been reported among people with schizophrenia. We aimed to systemati-cally review literature on disordered eating among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorder (SSD). Seven databases were systematically searched for studies that described the prevalence and correlates of disordered eating among patients with SSD from January 1984 to 15 February 2021. Qualitative analysis was performed using the National Institutes of Health scales. Of 5504 records identified, 31 studies involving 471,159 subjects were included in the systematic review. The ma-jority of studies (17) rated fair on qualitative analysis and included more men, and participants in their 30s and 40s, on antipsychotics. The commonest limitations include lack of sample size or power calculations, poor sample description, not using valid tools, or not adjusting for con-founders. The reported rates were 4.4% to 45% for binge eating, 16.1% to 64%, for food craving, 27% to 60.6% for food addiction, and 4% to 30% for night eating. Positive associations were re-ported for binge eating with antipsychotic use and female gender, between food craving and weight gain, between food addiction and increased dietary intake, and between disordered eating and female gender, mood and psychotic symptoms. Reported rates for disordered eating among people with SSD are higher than those in the general population. We will discuss the clinical, treatment and research implications of our findings.

1. Introduction

People with schizophrenia have a two to five-fold increased risk for diabetes, metabolic syndrome, obesity, and cardiovascular diseases compared to the general population [1,2]. Up to 25% of people with schizophrenia have diabetes mellitus, 35% have metabolic syndrome, and up to 50% of those on antipsychotics gain weight [3,4]. These adverse physical health outcomes contribute to a 20% (20–30 year) reduction in lifespan [5] mainly through cardiovascular sequelae [6,7]. These physical health issues are also associated with other negative outcomes such as poor adherence to treatment [8,9], poor quality of life [10,11], greater risk of relapse [12,13], and low self-esteem [11].

Extant research has shown consistent associations between diabetes, obesity, and metabolic syndrome, on the one hand, and behaviors such as smoking, substance use, unhealthy dietary choices, and a sedentary lifestyle, on the other [7,14]. People with schizophrenia are more likely to have a diet rich in saturated fats and calories and poor in fibre and fruit [1]. It is also well established that rates of cigarette smoking (60–90%) and substance use [15] are much higher amongst people with schizophrenia, than the general population. Impaired executive functioning [16] has also been found to be associated with higher rates of metabolic adversities.

A relevant and common problem is disordered eating, which is a term used to describe unhealthy eating patterns that may not meet the diagnostic threshold for an eating disorder, but which have a negative impact on functioning [17]. Studies in non-psychotic and general populations provide evidence for associations between disordered eating and childhood adversities [18], substance use disorders [19], type 2 diabetes mellitus [20], obesity [21], executive function deficits [22] and frontal lobe functional impairment [23].

As all these adversities are far more common among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, in conjunction with the greater likelihood of people with schizophrenia to have a poor diet as outlined above, it is conceivable that rates of disordered eating behaviors are higher in this population. Interestingly, over 100 years ago, Kraepelin and Bleuler described disorganized and uncontrolled food intake as one of the clinical characteristics of schizophrenia [24,25]. Bleuler associated this with delusions of poisoning, agitation, autism, and catatonic negativism [26]. The topic has found a renewed interest recently, and several studies have now examined the prevalence and correlates of disordered eating in schizophrenia. Studies have described associations between eating behaviors and medications such as clozapine and olanzapine [27], as well as with executive dysfunction [28], positive symptoms [29], and anxiety, depression, and sleep disturbances in people with schizophrenia [17]. Other contributors to disordered eating in schizophrenia include abnormalities of the HPA axis [26] and shared genetic vulnerability for eating disorders and schizophrenia [30]. Some authors have posited disordered eating as being an independent and distinct entity amongst people with schizophrenia [29].

Published studies of eating behaviors in schizophrenia differ widely in terms of their methodology and aims, the type of disordered eating studied, the instruments used, and the sample selected. It is therefore important to review these studies systematically to understand the association and mechanisms, with a view of guiding clinical practice and future research. In regard to previous reviews related to this topic, Dipasquale et al. [1] systematically reviewed the literature on dietary patterns in schizophrenia, rather than disordered eating per se. Their review of 31 studies found that schizophrenia patients’ diet was high in saturated fat, and low in fibre, factors that contribute to a higher risk of metabolic abnormalities. Kouidrat et al. [31] reviewed the literature on eating disorders (rather than disordered eating) in schizophrenia in 2014. They concluded that binge eating disorders and night eating syndromes are frequently found in people with schizophrenia and recommended regular screening for eating disorders in schizophrenia patients, but that review is now dated. Finally, and more recently, Stogios et al. [32] performed a scoping review of disturbed eating in psychosis. While this is current, the study had a broad scope of including all psychotic disorders (including bipolar disorders) and all eating behaviors (including food preferences and dietary compositions) without assessing the strengths or weaknesses of individual studies, or providing a qualitative analysis of the reviewed studies. The authors focused on the psychopathological and neurobiological mechanisms as opposed to uncovering the phenomenology of eating disturbances in psychotic disorders.

Hence, there is a need for an updated, systematic review of disordered eating among people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders (SSD). We present such a review and report specifically on the prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder (diagnosed, sub-threshold, and spectrum disorders), food craving and food addiction, night eating, and other disordered eating behaviors including loss of control over eating, as well as cognitive restraint. In particular, we determine the prevalence of aberrant eating behaviors and assess whether they are related to the specific symptoms/domains of schizophrenia symptomatology (e.g. positive, negative, or cognitive or affective) or stage of illness (acute versus chronic). We also assess associations with specific antipsychotic treatments. This information we anticipated will help clinicians identify and manage disordered eating in people with SSD.

2. Materials and Methods

Our systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) [33] guidelines. Publications were identified through a systematic search of seven bibliographic databases: Ovid MEDLINE(R) ALL 1946 to 15 February 2021; Embase 1974 to 2021 February 15 (Ovid); APA PsycInfo 1806 to February Week 2 2021 (Ovid); Ovid Emcare 1995 to 2021 Week 05; CINAHL (EBSCOhost); Cochrane Library (Wiley) and the Informit Health Collection and Humanities and Social Sciences Collection (RMIT).

Search strategies were developed by a medical librarian (HW) in consultation with AS, DC, DM and PH. Strategies combined the concepts of Schizophrenia AND Disordered Eating using a combination of subject headings and text words. Searches were limited to English language publications dated 1 January 1980 onwards: we chose this cut-off to coincide with the publication of DSM III, as there were changes to the nosology of the eating disorders, notably bulimia nervosa being added as a discrete disorder. An initial search was developed for Ovid Medline (Table 1) and then adapted for other databases, adjusting subject headings and syntax as appropriate. All bibliographic database searches were updated on 17 February 2021 except for Informit Health, which ceased to exist in the same format and was last searched on 27 August 2020. Reference lists of included studies were screened for additional publications.

Table 1.

Search strategy for Ovid MEDLINE ® ALL 1946 to 15 February 2021.

2.1. Study Selection

Search results were exported to Endnote bibliographic management software and duplicates removed. In accordance with pre-determined inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2), records were screened on publication type. Conference abstracts, conference papers, dissertations, irrelevant letters, notes, comments, and book reviews were excluded. All remaining records were uploaded into Covidence systematic review software for further screening. Two reviewers (AS and DV) independently screened the remaining records on title and abstract, then full text based on the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2). Conflicts were resolved through discussion between both reviewers and, where necessary, a third reviewer.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.2. Quality Appraisal

AS and SM undertook the quality appraisal, using items from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Study Quality Assessment Tools for Case-Control studies, and NIH Study Quality Assessment Tools for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional studies [34]. The following items were focused on: (1) type of study design; (2) clear research question with clear aims, objectives, or hypothesis; (3) sample size justification or power calculation; (4) clearly defined study population (inclusion and exclusion criteria and details of the study subjects and setting were discussed); (5) clearly defined and valid outcome measures (objective measures and instruments that are reliable and valid); (6) analyses use appropriate statistical techniques and account for all participants; (7) key confounders measured and adjusted for. Some of the items on NIH scales (e.g., exposure measured prior to the outcome; whether the timeframe was sufficient to expect an association between exposure and outcome; were different levels of exposure measured; and blinding) were less relevant to this systematic review and were therefore dropped. The chosen items allowed for a maximum of 9 points and studies were ranked as poor (1–3 points), moderate or fair (4–6 points), or good in quality (7–9 points) depending on the total points scored.

2.3. Data Extraction

A data-extraction checklist was created and AS, KJ, and VM extracted data on: study details (first author’s name, year of publication, country studied in), study design, sample characteristics (age and gender distribution, sample diagnosis and diagnostic criteria studied, selection criteria, study setting; and, for case-control studies, the description of controls), outcome variables studied (definition, instruments used, diagnostic criteria if relevant), any confounders adjusted for, and information on missing variables. All papers were reviewed by at least two investigators.

2.4. Data Synthesis

Data were synthesized descriptively.

3. Results

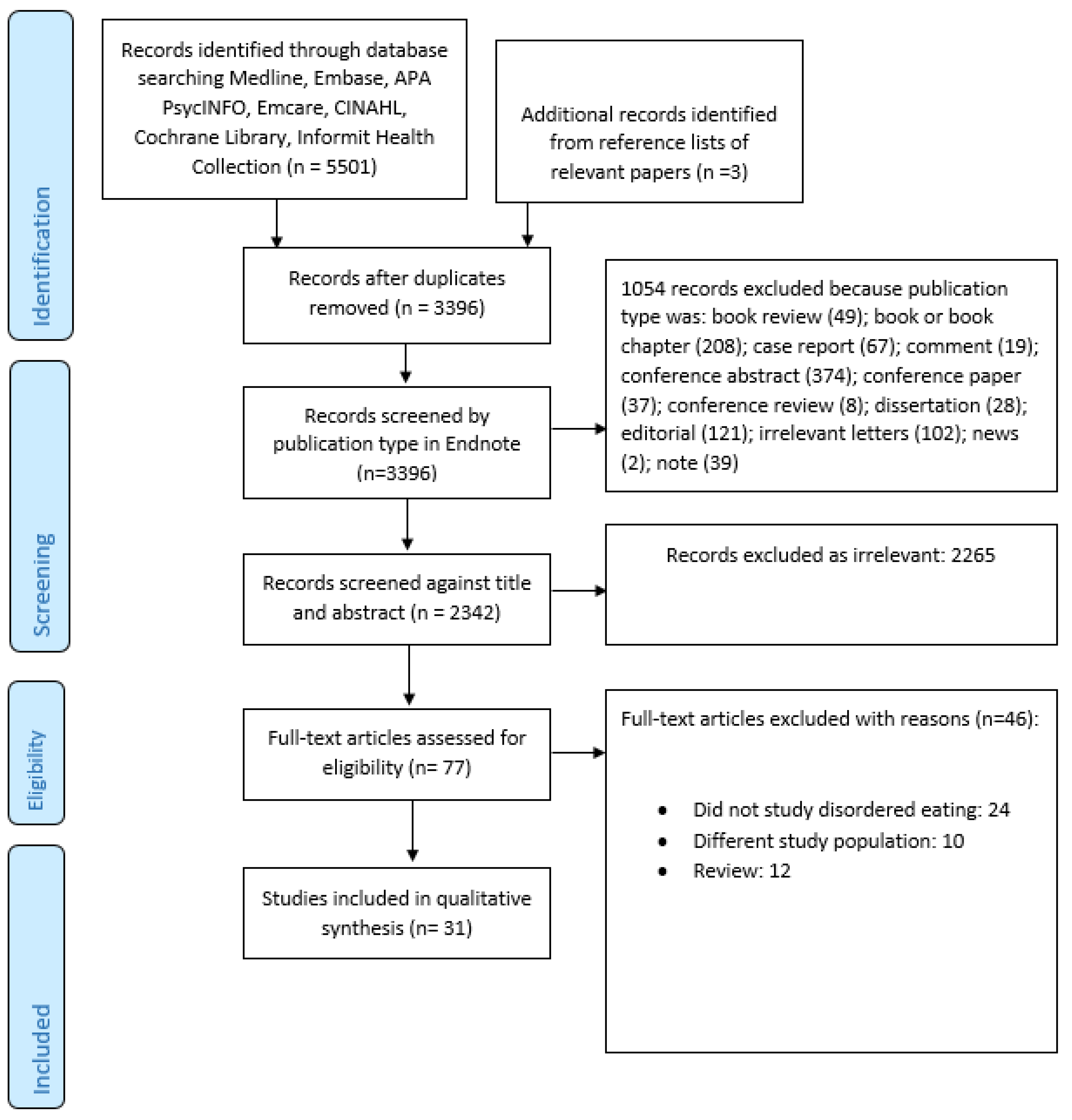

Figure 1 summarized the search and selection process. Our final selection included 31 studies [17,26,28,29,30,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60] (Table 3). Taken together, these studies included 471,158 individuals (including a single study by Striegel-Moore et al. [58] that encompassed 466,590 men), of whom 2651 had a diagnosis of SSD. A number of studies included patients with SSD as well as other psychiatric disorders but did not describe the exact break-up of the included diagnostic categories [26,28,43,57,58], making it impossible to determine the exact numbers of patients with SSD.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 3.

Summary of included studies.

The majority of the studies were cross-sectional observational studies (n = 15) [30,36,37,38,42,43,45,49,50,52,53,55,56,58,59] followed by case-control studies (n = 9) [17,26,29,35,39,44,47,48,51]. The case-control studies recruited healthy controls without history of mental illness. There were four cohort studies [40,41,54,60], with follow-up periods ranging from 10 weeks to 6 months. Three studies [28,46,57] reported results from clinical trials. Most of the studies were from Europe (47%), followed by North America (23%), although there were studies from most regions. Two studies were performed across multiple sites [28,60].

3.1. Sample Characteristics

Twenty-seven studies [17,26,28,29,30,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,44,55,57,60] were performed in patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or SSD, and four studies included patients with multiple diagnoses [43,56,58,59]. The majority of the studies used DSM-IV criteria (n = 20), followed by ICD-10 (n = 3); one multisite study [60] used both DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria. Five studies did not describe the diagnostic criteria used [28,38,42,43,56]. In around half of the studies (n = 13), participants were recruited from community or outpatient settings [29,36,38,42,44,45,48,50,51,52,53,56,60], while eight studies employed hospital or inpatient settings [17,26,30,40,43,49,58,59], and three studies recruited from multiple locations [35,41,55]. Seven studies [28,37,39,46,47,54,57] either were unclear or did not specify where participants were recruited from.

The majority of the studies (n = 15) included more men [28,29,30,35,37,38,39,41,42,47,48,50,53,55,59]. All studies were of adults, apart from the study of Bachman et al. [37], which was of a child and adolescent population with a mean (SD) age of 19.2 (2.3) years for males and 19.7 (2.6) years for females. The majority of the other studies included participants who were in their 30s [30,35,39,40,41,44,45,46,47,49,53,54,55,60] and 40s [26,36,38,48,51,52,56,57]. Case et al. [28] described data from four trials and participant age varied across sites. Goluza et al. [42] and Kurpad et al. [50] did not provide the mean age for their sample and two studies [43,58] included a mix-sample with no specific age descriptions for participants with SSD.

The majority of the participants in the included studies were receiving antipsychotics, mostly second-generation antipsychotics and specifically, olanzapine and clozapine. Only two studies recruited antipsychotic-naïve patients [29,55]. Participants in most studies were overweight or obese [28,29,36,39,41,49,50,51,52,53,57]. Sixteen studies described limited or no selection criteria [26,28,30,37,38,40,42,43,44,46,49,51,53,56,57,58]. The commonly described exclusion criteria included those with substance use [36,45,48,49,50,51,55], diabetes mellitus [29,36,47,48,55], intellectual disability [17,29,47,48,59], and pregnancy [29,36,49,55].

3.2. Quality Appraisal

The results of the quality appraisal are summarized in Table 4. The majority (n = 17) of the articles were rated fair or moderate in quality [26,30,37,38,39,42,44,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,55,56,57]. Eight rated good [17,29,35,41,45,54,59,60] and six were poor [28,36,40,43,53,58]. There appeared to be a “period effect” with all of the studies rated “good” having been published after 2009, when we arbitrarily used three publication periods:1980–1999, 2000–2009, and 2010 and after. The type of reporting (e.g., short report by Striegel-Moore et al. [58]) and the study design (e.g., Kluge et al. [46] or Beaurepaire [38]) had an impact on the study ratings. Treuer et al. [60] was the best reported and Case et al. [28] rated poor. Although this study had a sample size of 805 subjects across the four trials, there were differences in design, duration of trial, sample characteristics, the dose of olanzapine used, and the tools used across the four trials that affected the quality of the study.

Table 4.

Summary of Quality Assessment.

The majority of the studies present neither sample size nor power calculations. Other limitations include inadequate sample description [26,28,30,37,38,40,42,43,44,46,49,51,52,53,56,57,58], not defining outcome variables or not using valid tools [28,36,38,40,46,50,57,60]. Only 15 studies adjusted for confounders [17,29,30,35,39,41,47,48,52,54,55,56,57,59,60], most commonly obesity/BMI [39,41,48,52,55,56,57,59,60], age [41,48,52,54,56,57,59] and gender [41,48,52,54,56,57,59].

3.3. Disordered Eating

Most studies that reported or described disordered eating used validated and standardized instruments such as the Eating Inventory or Three Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ) [37,39,45,47,48,55], Eating Attitudes Test (EAT) [17,26,29,56,59], Food Craving Inventory (FCI) [28,35,41], Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) [55]. Others used diagnostic criteria for eating disorders from the DSM [26,38,43,44,45,53] or ICD [58]. Some studies reported using specially developed questionnaires [36,38,46,47], or tools that have not been validated, such as the Eating Behavior Assessment and Eating Attitude Scale [28,57].

3.3.1. Binge Eating

Eleven studies [26,28,36,38,40,44,45,46,50,53,60] reported on binge eating. All of these studies reported patients who were on antipsychotics. Eight of these were cross-sectional, one case-control, and the other two reported secondary results from multi-site clinical trials. In summary, these studies indicate that people with SSDs on antipsychotic treatment had elevated rates of binge eating, with rates ranging from 4.4% [38] to 16% [40,53] for binge eating disorder (BED) and 8.9% [46] to 45% [50] for binge eating symptoms (not meeting the diagnostic threshold for BED). In general, cross-sectional [45,50,53], case-control studies [26,44] and studies with small sample size [40] reported higher prevalence rates. Aguiar-Bloemer et al. [36] and Bromel et al. [40] describe an increase in binge eating after the commencement of clozapine (through qualitative survey or prospective measures). One patient in the study of Bromel et al. described that their binge eating symptoms completely reverted after temporarily stopping clozapine but recommenced with re-initiation. In these studies, binge eating overall was associated with female gender [26,38,45] or weight gain [28,60].

3.3.2. Food Cravings and FOOD Addiction

Eleven studies [28,35,36,40,41,42,46,49,50,54,57] provided information on food crav-ings and/or food addiction. All these studies were in people prescribed antipsychotic medication; four [36,42,49,50] were cross-sectional and one case-control [35]. The re-maining six used prospective data or were post hoc analyses of patients recruited to clinical trials. Prevalence rates for food cravings varied from 16.1% [36] to 64% [46] and was highest for sweets (chocolates, candies). Food addiction was reported in 27% [42] to 60.6% of samples [49]; Goluza et al. [47] noted that 77.4% of their patients’ reported symptoms of food addiction but did not experience associated distress or impairment. Study design could not account for the variation in rates seen. One study [35] found that patients on typical antipsychotics had higher craving scores than those on olanzapine (although not statistically significant). Craving for fast-food was associated with weight gain [28,41], and food addiction was associated with increased dietary in-take [49]. Stauffer et al. [57] demonstrated that reduction in carbohydrate craving was predictive of weight loss in treatment trials. Food craving inventory (28, 35, 41) and Yale food addiction scale (42, 49) were the most commonly used tools while some studies (36, 40, 50, 57) did not use validated tools.

3.3.3. Night Eating

Night eating in SSD was assessed in four studies [38,50,51,52] two of which [51,52] were of overweight or obese individuals. The prevalence of night eating ranged from 4% [50] to 30% [38]. It is possible that the high rate reported in the study of de Beaurepaire [38] reflects their employing only a single screening question for night eating. However, Lundgren et al. [51] reported a rate of 27.2% for evening hyperphagia and 50% of their sample reported snacking on waking up in the middle of the night. Palmese et al. [52] reported that their patients were not aware of night eating but many endorsed symptoms of insomnia and depression. The four studies used different tools to study night eating.

3.3.4. Other Disordered Eating Behaviors

A total of 18 reviewed studies [17,26,29,30,36,37,39,43,47,48,50,51,55,56,57,58,59,60] described various aspects of disordered eating behaviors (including snacking, impaired cognitive restraint, disinhibition, and susceptibility to hunger, scoring positive on scales for disordered eating such as Eating Attitudes Test (EAT) or Three Factor Eating Questionnaire (TFEQ), EDNOS, etc.) in people with SSDs. The reported prevalence ranged from 10% [30] to 41.5% [17] and was 2.4–4 times higher than in healthy controls [17,29] in case-control studies. There were methodological differences across studies; for example, while Fawzi and Fawzi [29] looked at current symptoms of DEBs, Malaspina et al. [30] assessed DEBs with onset prior to the SSD.

In general, people with SSD were more likely to score high on cognitive restraint, disinhibition, and hunger [37,39,47,48,55], to describe emotional eating [48,55], loss of control over eating [39,47], eating in response to internal and external stimuli, including sight, smell, or taste of food rather than hunger [39,51], and were likely to snack when unwell [36,50]. Many reported these issues were exacerbated by antipsychotics [17,37,55]. Other factors associated with disordered eating among people with SSD include female sex [26,29,30,55,56], anxiety and depression [17], prominent positive psychotic symptoms [17,30], negative symptoms [29], impaired executive function [47], and type 2 diabetes mellitus [17]. Elevated BMI was positively associated with disordered eating [29,37,55,56], albeit results were not uniform; for example, Fawzi and Fawzi [29] did not find any association between disordered eating and positive or negative symptoms, Kouidrat et al. [48] reported an association between higher cognitive restraint and BMI lower than 25, and Malaspina et al. [30] reported an association between DEBs and higher cognitive functioning, especially in men.

4. Discussion

We undertook a systematic review of disordered eating among people with SSDs. We found 31 studies encompassing 471,158 individuals, of whom 2651 had a reported diagnosis of an SSD. Two of these studies [43,58] included mixed diagnosis (including schizophrenia patients) among those with disordered eating.

Our review of studies, most of which were done in people receiving antipsychotics, found elevated rates of binge eating, night eating, food addiction, food craving, and disordered eating behaviors among people with SSD. Taken together, these studies report a prevalence of 4.4% to 16% for binge eating disorder (BED) and 8.9% to 45% for binge eating symptoms, 16.1% to 64% for food craving, 27% to 77.4% for symptoms of food addiction, 4% to 30% for night eating, and 10% to 41.5% for disordered eating behaviors. The rates for other DEBs were 2.5 to 4 times higher than that in healthy controls. Recent reviews [61,62] suggest lifetime prevalence rate for BED of 1.53% (95% CI 1–2.17) in the general population, and a point prevalence of 1.2–8% for BED and 3.8% to 8.4% for NES in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Pursey et al. [63] reported a weighted prevalence of nearly 20% for food addiction in obese adults. A simple comparison shows that the rates for disordered eating are higher in people with SSD; thus, there is a 2 times higher rate for BED, and up to threefold higher for night eating syndrome and food addiction among people with SSD. We also found that patients with SSD often do not fulfil the full diagnostic criteria for these conditions and in particular, do not report distress; hence they may have symptoms without the full diagnosis, and the rates for these are even higher. This lack of distress has been attributed to apathy and negative symptoms of schizophrenia, or the general lack of insight in this population [42], or because specific items such as “eating alone because of feeling embarrassed” did not apply to this population as they tended to live alone [38]. Previous studies in general population have shown that the incidence of DEBs is higher than diagnosable eating disorders, but despite their adverse impact on the individual’s functioning [64], are often untreated or missed by healthcare professionals [65]. There is also evidence for an association between disordered eating behaviors and excess eating, weight gain, and association with gender, and symptoms or chronicity.

It is unclear whether disordered eating in SSD is a part of the psychopathology, or whether it is secondary to medications, or an independent comorbid entity. We examine evidence for all three possibilities, below.

4.1. Role of Medications

Antipsychotic use, especially second-generation antipsychotics (SGA), is associated with higher risk of weight gain, obesity and metabolic complications [66]. A number of factors including neurotransmitter mechanisms, affect the brain’s satiety center, whilst an impact on insulin and gastrointestinal hormones and lifestyle issues have been put forth to explain this association [17]. In addition, disordered eating, such as binge eating and sweet food craving, have been reported in association with SGAs [27,46,67]. Studies that used a prospective design [40,46] demonstrated an increase in food cravings or binge eating over time for people on SGAs. Bromel et al. [40] reported a temporary cessation of binge eating in one patient when the antipsychotic was temporarily ceased. Using a case-control design, Blouin et al. [39], demonstrated a higher tendency for hunger and disinhibition scores for those on SGAs than healthy controls, and Sentissi et al. [55] reported increased reactivity to external food cues for people on SGAs compared to those on typical antipsychotics. These above factors increase the risk of excessive eating and loss of control over eating [44]. It is likely that antipsychotic-induced reduced serotonergic neurotransmission might also play a role in binge eating and food craving [46]; this includes evidence for reduced serotonin transporter binding among obese binge eating women in a SPECT study [68], a role of SSRIs in BED [69,70], and an association of serotonin transport gene polymorphism with BED [71]. Further, the effect of SGAs on the satiety center could account for why patients taking these agents continue to eat and do not feel full after a meal [51]. Schizophrenia patients with simultaneous high restriction and high disinhibition scores are more likely to be overweight and to be treated with atypical antipsychotics [44,55].

4.2. Illness Related

The fact that disordered eating behaviors were reported prior to the advent of antipsychotics [24,25,53] and in antipsychotic-naïve individuals [29] lends weight to the corollary that core psychopathology could play a role. This is further strengthened by findings that antipsychotic use did not impact binge eating patterns [50]. Historically, restrictive eating behaviors in schizophrenia were considered to be consequent upon delusions and hallucinations [26,51], whereas BED and BN were thought to be associated with negative, cognitive, and mood symptoms [50,53]. Indeed, disturbances in appetite, eating and weight are not confined to diagnoses classified under “eating and feeding disorders” in schemes such as the DSM (e.g., hyperphagia and deficient appetite noted in mood disorders). In their sample, Malaspina et al. [30] showed that patients who had a history of an ED had more severe psychotic and disorganization symptoms, whereas Treuer et al. [72] suggested that clinical improvement of psychotic symptoms seemed to coincide with increased food intake, while De Beaurepaire [38] reflect an association with improvement in psychotic symptoms. Indirect evidence suggests that perturbations in brain regions that moderate reward mechanisms and dopamine dysfunction in schizophrenia could play a role in food addiction [42,49]. This could also explain the sweet and fast-food craving seen in schizophrenia [73,74]. Alternate explanations for food cravings impairments in schizophrenia include dysregulation of serotonin neurotransmission [75] or altered dopamine/acetylcholine ratio in certain brain areas such as the nucleus accumbens [76].

Finally, the role of comorbid diabetes and disordered eating behaviors in schizophrenia needs to be considered and further studied. It is well accepted that rates of type 2 diabetes mellitus is 2–5 times higher in people with schizophrenia than in general population [77]. Although often linked to second generation antipsychotics, the first documented evidence for this association dates back to the late nineteenth century, long before antipsychotics and modern obesogenic diets [78].In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis exploring prevalence of diabetes in first episode psychosis population, Pillinger et al. [79] provide evidence for impaired glucose homeostasis from illness onset in schizophrenia. It is possible that diabetes and schizophrenia share common early developmental risk factors (e.g., preterm birth, gestational diabetes, maternal malnutrition, etc.) suggesting that stress and hypercortisolemia may contribute to the association between the two conditions.

Diabetes mellitus is associated with increased appetite and disordered eating (especially bulimia and binge eating disorder) and this, in turn, is associated with elevated HbA1C and other diabetic complications including retinopathy, neuropathy, lipid abnormalities, ketoacidosis and poor metabolic control [80]. Diabetes is also associated with impairment in satiety and hunger signals. Insulin crosses the blood-brain barrier and acts on hypothalamus to regulate appetite and food intake [81]. Further, anti-diabetic medications have been found to be effective in reducing binge-eating in non-diabetic population [82]. It is therefore possible that, at least in some individuals, antipsychotics (particularly second generation) triggers, increases, or unmasks the vulnerability for diabetes mellitus in people with schizophrenia and leads to changes in the appetite and weight control centers, predisposing the individual to disordered eating behaviors. The inherent symptoms of schizophrenia could further reinforce disordered eating. For example, negative symptoms and hypodopaminergia can induce food addiction, or binge eating, mood symptoms could be associated with comfort eating, and cognitive rigidity could be associated with reduced cognitive restraint.

4.3. Other Explanations

A third explanation for the association of schizophrenia with disordered eating, they are distinct entities that coexist and overlap by chance [29]. Disordered eating problems are often missed because clinicians focus on psychotic symptoms, and/or because the disordered eating is not severe or typical enough to meet the diagnostic threshold for an independent eating disorder label. Some commentators have conceptualized DEBs as a physiological compensatory mechanism in reducing psychotic symptoms; this is based on the premise that starvation induces psychosis [83]. DEBs often predate psychosis and share common risk factors including developmental trauma [38]. A shared genetic susceptibility for schizophrenia and anorexia nervosa has also been described [84].

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this review include the comprehensive search strategy and use of multiple authors for quality appraisal and data extraction. Limitations included limiting to only published literature (no grey literature) and papers in English. Whilst the impact of the latter may have been mitigated by the inclusion of multiple studies from non-English speaking backgrounds, adding grey literature can lower the impact of publication bias [85]. Our review also captured a different literature to the scoping review by Stogios et al. [32] and there were only ten studies in common [35,39,40,41,44,46,47,54,55,60]. We believe therefore, that our findings complement and lend additional weight to their findings.

We did not undertake a meta-analysis as the studies were highly heterogeneous, differing in the types of disordered eating studied, with differing methodologies, definitions, and thresholds. The quality of included studies was largely fair to good and we tried to link the information from individual data to the methodology, outcome measures, and qualitative analysis to give weight to the conclusions drawn. We had amended the NIH scale as some of the items were less relevant to our review and were therefore dropped. We do not believe this could have affected our quality rating.

While we did not exclude studies that focused on anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, this review focused on disordered eating behaviors. There are overlaps between the different eating disorders and there is a possibility of diagnostic crossover or migration between the different disorders [86,87]. However, we are not aware of any studies that have necessarily studied the stability of eating disorder or disordered eating in SSD. Our review included studies from 1985 to 2021; our knowledge and understanding of eating disorders have evolved over this time and this is reflected in how the classificatory systems have changed. For example, the criteria for binge eating in Hay and Hall’s [43] study using DSM III R criteria was “at least two days a week for three months”, which changed to “at least two days a week for 6 months” in the DSM-IV, and now is at least one day a week for three months” in the DSM-5. Similarly, night eating syndrome, although initially described by Stunkard in 1955 [88], only found a place under OSFED criteria in the DSM-5. These changes have an impact on what is considered and accepted as disordered eating behaviors.

4.5. Clinical Implications

It is likely that multiple factors play a role in the association between schizophrenia with disordered eating. Antipsychotics influence the appetite and satiety centers of the brain and lead to hyperphagia [39,89]. There could be a simultaneous preference for sweet and hyperpalatable foods, which contain high dietary levels of sugar and fat. This can, in turn, have “high addictive potential” and reinforce further disordered eating behaviors [90]. Intrinsic illness factors in schizophrenia such as abnormalities in the mesolimbic reward circuit, or impaired cognitive restraint and executive functioning could mediate further disordered eating patterns in response to increased appetite and cravings.

It is possible that the actual prevalence of disordered eating in people with SSDs is substantially higher than reported in the studies reviewed here. Several factors could account for lower reported rates, including absence of distress or impairment [42], confusing criteria in people with schizophrenia (e.g., teasing out the differences between loss of control and intense desire, or between food craving and increased hunger), as well as lack of clear definitions (e.g., for food addiction). Further, de Beaurepaire [38] reported patients who experienced binge eating as pleasurable, in contrast with others who eat excessively but eat slowly. Hence it is likely that different thresholds or criteria are needed when assessing disordered eating behaviors in people with SSD. Similarly, future studies exploring night eating in schizophrenia should differentiate between nocturnal eating and evening hyperphagia.

Future studies need to examine the role of smoking in obesity-related behaviors [91,92]. SSDs are associated with high rates of cigarette smoking and substance use [15]. This has been partly explained by a putative self-medication hypothesis as a mechanism to offset the “negative” symptoms or hypodopaminergia. It is plausible that DEBs such as food addiction is a behavioral variant of this “impulse-control” issue and reflective of underlying impairments in the reward system. The possible role of smoking on cognition in schizophrenia and the impact on disordered eating needs to be studied further. Similarly, there is a need to study the role of smoking cessation or reduction on eating behaviors in people with SSDs. Studies have shown an association with all phases (acute and chronic) and all symptom domains of schizophrenia (positive, negative, cognitive, and affective). There is therefore a need for further research into disordered eating and in particular whether this forms an integral part of the symptoms of schizophrenia as discussed by Bleuler and Kraeplin more than a hundred years ago [24,25] and if disordered eating should be included among diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia. It is particularly important to look for “disordered eating” rather than an “eating disorder” as patients with SSD may not fulfil all the criteria for eating disorders, while they could still experience symptoms or manifest features of an eating disorder. An association between choking risk in schizophrenia (and in particular with antipsychotic use) [93] and choking risk with eating rapidly [94] have been described. The role of disordered eating behaviors in choking risk in SSD needs to be studied further.

As the rates for disordered eating are higher among people with SSD, it is important to train clinicians to look for, assess and manage eating disorders at various stages of the illness, particularly modelled along the lines of those for substance-use disorders [56]. Patients with SSD should be offered healthy lifestyle and dietary advice to develop skills to respond to physiological urges to eat, encouraged to eat on a regular schedule, eating on a budget, focus on reducing sugary food, and improve exercise and physical activity [51,56]. Cognitive behavioral therapy has shown to be effective for binge eating in a randomized controlled study of patients with antipsychotic-induced weight gain [95].

Pharmacological strategies have a role in mitigating antipsychotic induced weight gain. For example, preliminary research shows that naltrexone can be useful in antipsychotic induced weight gain [96] and targets both the endorphin and dopamine systems and could play a role in food cravings [97]. Naltrexone can reduce the rewarding aspects of food and reduce food consumption and reduce appetite [98]. It is important to consider that at least some studies have described that people with SSD did not report “distress” or “lack of impairment”; the role, place, and type of intervention needs to be studied further to elucidate whether intervention is warranted and what the best form of intervention is.

Studies have shown an association between SSD and higher scores on cognitive restraint, disinhibition, and hunger [37,39,47,48,55]; higher cognitive restraint is associated with lower BMI [48] and with weight loss [99] and better weight loss maintenance in treatment programs [100]. Studies of eating disorders have shown an association between cognitive flexibility and eating disorders, particularly anorexia nervosa [101,102] and a role for cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) for these disorders [103,104]. Although CRT has been studied in schizophrenia [105], its role in addressing disordered eating in schizophrenia has not, to our knowledge, been examined. Future research should explore the role for CRT in the different disordered eating in SSD.

5. Conclusions

Our systematic review provides evidence for an increased rate of binge eating, night eating, food cravings and addiction, and disordered eating behaviors among SSD patients. While this could be related to the illness itself, most of the included studies were performed in patients receiving antipsychotic treatment; hence, it would be difficult to establish whether this is a primary issue or secondary to medications or symptoms. There is a need for studies that assess disordered eating at baseline in early psychosis and prospectively with the commencement of antipsychotics. Studies need to be powered to be able to study the role of medications and other illness characteristics and should be able to inform the role of disordered eating in people developing metabolic complications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.S., methodology: design and search: A.S., H.E.W., D.M., D.J.C. and P.H., culling: A.S. and D.V., data extraction: K.J., V.M., A.S., quality appraisal: S.J.M., A.S., software: H.E.W., writing—original draft preparation: A.S., writing—review and editing: S.J.M., K.J., H.E.W., D.M., D.J.C., P.H., supervision: P.H., funding acquisition: A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The publication costs were covered by the NSW Health Training, Education, and Study Leave (TESL) entitlements for Anoop Sankaranarayanan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Dipasquale, S.; Pariante, C.M.; Dazzan, P.; Aguglia, E.; McGuire, P.; Mondelli, V. The Dietary Pattern of Patients with Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancampfort, D.; Correll, C.U.; Galling, B.; Probst, M.; De Hert, M.; Ward, P.B.; Rosenbaum, S.; Gaughran, F.; Lally, J.; Stubbs, B. Diabetes Mellitus in People with Schizophrenia, Bipolar Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder: A Systematic Review and Large Scale Meta-Analysis. World Psychiatry 2016, 15, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayano, G. Co-Occurring Medical and Substance Use Disorders in Patients with Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Ment. Health 2019, 48, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, S.L.; Taylor, M.; Lawrie, S.M. “First Do No Harm.” A Systematic Review of the Prevalence and Management of Antipsychotic Adverse Effects. J. Psychopharmacol. 2015, 29, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, S.C.; Bland, R.C. Mortality in a Cohort of Patients with Schizophrenia: A Record Linkage Study. Can. J. Psychiatry 1991, 36, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laursen, T.M. Life Expectancy among Persons with Schizophrenia or Bipolar Affective Disorder. Schizophr. Res. 2011, 131, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobes, J.; Arango, C.; Garcia-Garcia, M.; Rejas, J. Healthy Lifestyle Habits and 10-Year Cardiovascular Risk in Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders: An Analysis of the Impact of Smoking Tobacco in the CLAMORS Schizophrenia Cohort. Schizophr. Res. 2010, 119, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiden, P.J.; Mackell, J.A.; McDonnell, D.D. Obesity as a Risk Factor for Antipsychotic Noncompliance. Schizophr. Res. 2004, 66, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirshing, D.A. Schizophrenia and Obesity: Impact of Antipsychotic Medications. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2004, 65 (Suppl. 18), 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kruger, J.; Bowles, H.; Jones, D.; Ainsworth, B.; Kohl, H.K., III. Health-Related Quality of Life, BMI and Physical Activity among US Adults (X18 Years): National Physical Activity and Weight Loss Survey. Int. J. Obes. 2002, 31, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritsner, M.; Ponizovsky, A.; Endicott, J.; Nechamkin, Y.; Rauchverger, B.; Silver, H.; Modai, I. The Impact of Side-Effects of Antipsychotic Agents on Life Satisfaction of Schizophrenia Patients: A Naturalistic Study. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002, 12, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olfson, M.; Mechanic, D.; Hansell, S.; Boyer, C.A.; Walkup, J.; Weiden, P.J. Predicting Medication Noncompliance After Hospital Discharge Among Patients with Schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Serv. 2000, 51, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archie, S.M.; Goldberg, J.O.; Akhtar-Danesh, N.; Landeen, J.; McColl, L.; McNiven, J. Psychotic Disorders, Eating Habits, and Physical Activity: Who Is Ready for Lifestyle Changes? Psychiatr. Serv. 2007, 58, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, J.; Stedman, T.; Byrne, N.; Wishart, C.; Hills, A. Energy Expenditure and Physical Activity In Clozapine Use: Implications For Weight Management. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2006, 40, 810–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Leon, J.; Diaz, F.J. A Meta-Analysis of Worldwide Studies Demonstrates an Association between Schizophrenia and Tobacco Smoking Behaviors. Schizophr. Res. 2005, 76, 135–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grover, S.; Padmavati, R.; Sahoo, S.; Gopal, S.; Nehra, R.; Ganesh, A.; Raghavan, V.; Sankaranarayan, A. Relationship of Metabolic Syndrome and Neurocognitive Deficits in Patients with Schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 278, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, M. Biopsychosocial Factors Associated with Disordered Eating Behaviors in Schizophrenia. Ann. Gen. Psychiatry 2020, 19, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pignatelli, A.M.; Wampers, M.; Loriedo, C.; Biondi, M.; Vanderlinden, J. Childhood Neglect in Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Trauma Dissociation 2017, 18, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food for Thought; National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University: New York, NY, USA, 2003.

- Kenardy, J.; Mensch, M.; Bowen, K.; Green, B.; Walton, J.; Dalton, M. Disordered Eating Behaviours in Women with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Eat. Behav. 2001, 2, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto-Bastos, A.; Ramalho, S.M.; Conceição, E.; Mitchell, J. Disordered Eating and Obesity. In Obesity; Ahmad, S.I., Imam, S.K., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2016; pp. 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinella, M.; Lyke, J. Executive Personality Traits and Eating Behavior. Int. J. Neurosci. 2004, 114, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uher, R. Brain Lesions and Eating Disorders. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2005, 76, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraepelin, E. Dementia Praecox and Paraphrenia; Thoemmes: Bristol, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bleuler, E. Textbook of Psychiatry; Macmillan Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1924. [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos, G.; Paterakis, P.; Beis, A.; Lyketsos, C. Eating Disorders in Schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry 1985, 146, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebhardt, S.; Haberhausen, M.; Krieg, J.-C.; Remschmidt, H.; Heinzel-Gutenbrunner, M.; Hebebrand, J.; Theisen, F.M. Clozapine/Olanzapine-Induced Recurrence or Deterioration of Binge Eating-Related Eating Disorders. J. Neural. Transm. 2007, 114, 1091–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, M.; Treuer, T.; Karagianis, J.; Hoffmann, V.P. The Potential Role of Appetite in Predicting Weight Changes during Treatment with Olanzapine. BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawzi, M.H.; Fawzi, M.M. Disordered Eating Attitudes in Egyptian Antipsychotic Naive Patients with Schizophrenia. Compr. Psychiatry 2012, 53, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malaspina, D.; Walsh-Messinger, J.; Brunner, A.; Rahman, N.; Corcoran, C.; Kimhy, D.; Goetz, R.R.; Goldman, S.B. Features of Schizophrenia Following Premorbid Eating Disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 278, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouidrat, Y.; Amad, A.; Lalau, J.-D.; Loas, G. Eating Disorders in Schizophrenia: Implications for Research and Management. Schizophr. Res. Treat. 2014, 2014, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stogios, N.; Smith, E.; Asgariroozbehani, R.; Hamel, L.; Gdanski, A.; Selby, P.; Sockalingam, S.; Graff-Guerrero, A.; Taylor, V.; Agarwal, S.; et al. Exploring Patterns of Disturbed Eating in Psychosis: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Study Quality Assessment Tools | NHLBI, NIH. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- Abbas, M.J.; Liddle, P.F. Olanzapine and Food Craving: A Case Control Study: Olanzapine and Food Craving. Hum. Psychopharmacol. Clin. Exp. 2013, 28, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar-Bloemer, A.C.; Agliussi, R.G.; Pinho, T.M.P.; Furtado, E.F.; Diez-Garcia, R.W. Eating Behavior of Schizophrenic Patients. Rev. Nutr. 2018, 31, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, C.J.; Gebhardt, S.; Lehr, D.; Haberhausen, M.; Kaiser, C.; Otto, B.; Theisen, F.M. Subjective and Biological Weight-Related Parameters: In Adolescents and Young Adults with Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorder under Clozapine or Olanzapine Treatment. Z. Kinder-Jugendpsychiatrie Psychother. 2012, 40, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Beaurepaire, R. Binge Eating Disorders in Antipsychotic-Treated Patients With Schizophrenia. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 41, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blouin, M.; Tremblay, A.; Jalbert, M.-E.; Venables, H.; Bouchard, R.-H.; Roy, M.-A.; Alméras, N. Adiposity and Eating Behaviors in Patients Under Second Generation Antipsychotics. Obesity 2008, 16, 1780–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brömel, T.; Blum, W.F.; Ziegler, A.; Schulz, E.; Bender, M.; Fleischhaker, C.; Remschmidt, H.; Krieg, J.-C.; Hebebrand, J. Serum Leptin Levels Increase Rapidly after Initiation of Clozapine Therapy. Mol. Psychiatry 1998, 3, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garriga, M.; Mallorquí, A.; Serrano, L.; Ríos, J.; Salamero, M.; Parellada, E.; Gómez-Ramiro, M.; Oliveira, C.; Amoretti, S.; Vieta, E.; et al. Food Craving and Consumption Evolution in Patients Starting Treatment with Clozapine. Psychopharmacology 2019, 236, 3317–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goluza, I.; Borchard, J.; Kiarie, E.; Mullan, J.; Pai, N. Exploration of Food Addiction in People Living with Schizophrenia. Asian J. Psychiatry 2017, 27, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, P.J.; Hall, A. The Prevalence of Eating Disorders in Recently Admitted Psychiatric in-Patients. Br. J. Psychiatry 1991, 159, 562–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaal, Y.; Frésard, E.; Zimmermann, G.; Trombert, N.; Pomini, V.; Grasset, F.; Borgeat, F.; Zullino, D. Eating and weight related cognitions in people with Schizophrenia: A case control study. Clin. Pract. Epidemiol. Ment. Health 2006, 2, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Khazaal, Y.; Billieux, J.; Fresard, E.; Huguelet, P.; Van der Linden, M.; Zullino, D. A Measure of Dysfunctional Eating-Related Cognitions In People With Psychotic Disorders. Psychiatr. Q. 2009, 81, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kluge, M.; Schuld, A.; Himmerich, H.; Dalal, M.; Schacht, A.; Wehmeier, P.M.; Hinze-Selch, D.; Kraus, T.; Dittmann, R.W.; Pollmächer, T. Clozapine and Olanzapine Are Associated with Food Craving and Binge Eating: Results From A Randomized Double-Blind Study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2007, 27, 662–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knolle-Veentjer, S.; Huth, V.; Ferstl, R.; Aldenhoff, J.B.; Hinze-Selch, D. Delay of Gratification and Executive Performance in Individuals with Schizophrenia: Putative Role for Eating Behavior and Body Weight Regulation. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2008, 42, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouidrat, Y.; Amad, A.; Stubbs, B.; Louhou, R.; Renard, N.; Diouf, M.; Lalau, J.-D.; Loas, G. Disordered Eating Behaviors as a Potential Obesogenic Factor in Schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 269, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçükerdönmez, Ö.; Urhan, M.; Altın, M.; Hacıraifoğlu, Ö.; Yıldız, B. Assessment of the Relationship between Food Addiction and Nutritional Status in Schizophrenic Patients. Nutr. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon Kurpad, S.; George, S.; Srinivasan, K. Binge Eating and Other Eating Behaviors Among Patients On Treatment For Psychoses In India. Eat. Weight Disord.-Stud. Anorex. Bulim. Obes. 2010, 15, e136–e143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lundgren, J.D.; Rempfer, M.V.; Lent, M.R.; Foster, G.D. Perceptions of Factors Associated with Weight Management in Obese Adults with Schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2014, 37, 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmese, L.B.; Ratliff, J.C.; Reutenauer, E.L.; Tonizzo, K.M.; Grilo, C.M.; Tek, C. Prevalence of Night Eating in Obese Individuals with Schizophrenia and Schizoaffective Disorder. Compr. Psychiatry 2013, 54, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramacciotti, C.E.; Paoli, R.A.; Catena, M.; Ciapparelli, A.; Dell’Osso, L.; Schulte, F.; Garfinkel, P.E. Schizophrenia and Binge-Eating Disorders. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2004, 65, 1016–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, S.; Nam, H.; Oh, S.; Park, T.; Lim, M.; Choi, J.; Baek, J.; Jang, J.; Park, H.; Kim, S.; et al. Eating-Behavior Changes Associated with Antipsychotic Medications In Patients With Schizophrenia As Measured By The Drug-Related Eating Behavior Questionnaire. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2013, 33, 120–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sentissi, O.; Viala, A.; Bourdel, M.C.; Kaminski, F.; Bellisle, F.; Olié, J.P.; Poirier, M.F. Impact of Antipsychotic Treatments on the Motivation to Eat: Preliminary Results in 153 Schizophrenic Patients. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2009, 24, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srebnik, D.; Comtois, K.; Stevenson, J.; Hoff, H.; Snowden, M.; Russo, J.; Ries, R. Eating Disorder Symptoms Among Adults with Severe and Persistent Mental Illness. Eat. Disord. 2003, 11, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stauffer, V.L.; Lipkovich, I.; Hoffmann, V.P.; Heinloth, A.N.; McGregor, H.S.; Kinon, B.J. Predictors and Correlates for Weight Changes in Patients Co-Treated with Olanzapine and Weight Mitigating Agents; a Post-Hoc Analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2009, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Striegel-Moore, R.; Garvin, V.; Dohm, F.; Rosenheck, R. Psychiatric Comorbidity of Eating Disorders In Men: A National Study Of Hospitalized Veterans. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1999, 25, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, W.; Mahesh, M.; Abdin, E.; Tan, J.; Rahman, R.; Satghare, P.; Sim, K.; Basu, S.; Kandasami, G.; Gupta, B.; et al. Negative Affect Moderates the Link between Body Image Dissatisfaction and Disordered Eating among Psychiatric Outpatients in a Multiethnic Asian Setting. Singap. Med. J. 2020, 1, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treuer, T.; Hoffmann, V.P.; Chen, A.K.-P.; Irimia, V.; Ocampo, M.; Wang, G.; Singh, P.; Holt, S. Factors Associated with Weight Gain during Olanzapine Treatment in Patients with Schizophrenia or Bipolar Disorder: Results from a Six-Month Prospective, Multinational, Observational Study. World J. Biol. Psychiatry 2009, 10, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, S.; Dindol, N.; Tahrani, A.A.; Piya, M.K. Binge Eating Disorder and Night Eating Syndrome in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review. J. Eat. Disord. 2018, 6, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, J.; Wu, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhu, Y.; Jin, H.; Zhang, H.; Wan, Y.; Li, C.; Yu, D. An Update on the Prevalence of Eating Disorders in the General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eat. Weight Disord. 2021, 8, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pursey, K.; Stanwell, P.; Gearhardt, A.; Collins, C.; Burrows, T. The Prevalence of Food Addiction as Assessed by the Yale Food Addiction Scale: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2014, 6, 4552–4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touchette, E.; Henegar, A.; Godart, N.T.; Pryor, L.; Falissard, B.; Tremblay, R.E.; Côté, S.M. Subclinical Eating Disorders and Their Comorbidity with Mood and Anxiety Disorders in Adolescent Girls. Psychiatry Res. 2011, 185, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatt, S.J.; Mond, J.; Bussey, K.; Griffiths, S.; Murray, S.B.; Lonergan, A.; Hay, P.; Trompeter, N.; Mitchison, D. Help-Seeking for Body Image Problems among Adolescents with Eating Disorders: Findings from the EveryBODY Study. Eat. Weight Disord. 2020, 25, 1267–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rummel-Kluge, C.; Komossa, K.; Schwarz, S.; Hunger, H.; Schmid, F.; Lobos, C.A.; Kissling, W.; Davis, J.M.; Leucht, S. Head-to-Head Comparisons of Metabolic Side Effects of Second Generation Antipsychotics in the Treatment of Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2010, 123, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theisen, F.M.; Linden, A.; König, I.R.; Martin, M.; Remschmidt, H.; Hebebrand, J. Spectrum of Binge Eating Symptomatology in Patients Treated with Clozapine and Olanzapine. J. Neural. Transm. 2003, 110, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuikka, J.; Tammela, L.; Karhunen, L.; Rissanen, A.; Bergström, K.; Naukkarinen, H.; Vanninen, E.; Karhu, J.; Lappalainen, R.; Repo-Tiihonen, E.; et al. Reduced Serotonin Transporter Binding in Binge Eating Women. Psychopharmacology 2001, 155, 310–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tammela, L.I.; Rissanen, A.; Kuikka, J.T.; Karhunen, L.J.; Bergström, K.A.; Repo-Tiihonen, E.; Naukkarinen, H.; Vanninen, E.; Tiihonen, J.; Uusitupa, M. Treatment Improves Serotonin Transporter Binding and Reduces Binge Eating. Psychopharmacology 2003, 170, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElroy, S.; Hudson, J.; Malhotra, S.; Welge, J.; Nelson, E.; Keck, P. Citalopram in The Treatment Of Binge-Eating Disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2003, 64, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteleone, P.; Tortorella, A.; Castaldo, E.; Maj, M. Association of a Functional Serotonin Transporter Gene Polymorphism with Binge Eating Disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2006, 141B, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treuer, T.; Karagianis, J.; Hoffmann, V. Can Increased Food Intake Improve Psychosis? A Brief Review and Hypothesis. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008, 1, 270–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amani, R. Is Dietary Pattern of Schizophrenia Patients Different from Healthy Subjects? BMC Psychiatry 2007, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokes, C.; Peet, M. Short Communication. Nutr. Neurosci. 2004, 7, 247–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, J.M.; Pazos, A.; Hoyer, D. A Short History of the 5-HT2C Receptor: From the Choroid Plexus to Depression, Obesity and Addiction Treatment. Psychopharmacology 2017, 234, 1395–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gendall, K.A.; Joyce, P.R.; Sullivan, P.F. Impact of Definition on Prevalence of Food Cravings in a Random Sample of Young Women. Appetite 1997, 28, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamakou, V.; Thanopoulou, A.; Gonidakis, F.; Tentolouris, N.; Kontaxakis, V. Schizophrenia and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Psychiatriki 2018, 29, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maudsley, H. The Pathology of Mind, 3rd ed.; Macmillan and Co.: London, UK, 1879; p. 113. [Google Scholar]

- Pillinger, T.; Beck, K.; Gobjila, C.; Donocik, J.G.; Jauhar, S.; Howes, O.D. Impaired Glucose Homeostasis in First-Episode Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2017, 74, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young-Hyman, D.L.; Davis, C.L. Disordered Eating Behavior in Individuals with Diabetes: Importance of Context, Evaluation, and Classification. Diabetes Care 2010, 33, 683–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippi, B.M.; Mighiu, P.I.; Lam, T.K.T. Is Insulin Action in the Brain Clinically Relevant? Diabetes 2012, 61, 773–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, S.A.; Rohana, A.G.; Shah, S.A.; Chinna, K.; Wan Mohamud, W.N.; Kamaruddin, N.A. Improvement in Binge Eating in Non-Diabetic Obese Individuals after 3 Months of Treatment with Liraglutide—A Pilot Study. Obes. Res. Clin. Pract. 2015, 9, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yum, S. The Starved Brain: Eating Behaviors in Schizophrenia. Psychiatr. Ann. 2005, 35, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandys, M.K.; de Kovel, C.G.F.; Kas, M.J.; van Elburg, A.A.; Adan, R.A.H. Overview of Genetic Research in Anorexia Nervosa: The Past, the Present and the Future: Genetic Research in Anorexia Nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2015, 48, 814–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams, J.; Hillier-Brown, F.C.; Moore, H.J.; Lake, A.A.; Araujo-Soares, V.; White, M.; Summerbell, C. Searching and Synthesising ‘Grey Literature’ and ‘Grey Information’ in Public Health: Critical Reflections on Three Case Studies. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milos, G.; Spindler, A.; Schnyder, U.; Fairburn, C.G. Instability of Eating Disorder Diagnoses: Prospective Study. Br. J. Psychiatry 2005, 187, 573–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eddy, K.T.; Dorer, D.J.; Franko, D.L.; Tahilani, K.; Thompson-Brenner, H.; Herzog, D.B. Diagnostic Crossover in Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia Nervosa: Implications for DSM-V. AJP 2008, 165, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stunkard, A.; Grace, W.; Wolff, H. The Night-Eating Syndrome. Am. J. Med. 1955, 19, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernø, J.; Varela, L.; Skrede, S.; Vázquez, M.J.; Nogueiras, R.; Diéguez, C.; Vidal-Puig, A.; Steen, V.M.; López, M. Olanzapine-Induced Hyperphagia and Weight Gain Associate with Orexigenic Hypothalamic Neuropeptide Signaling without Concomitant AMPK Phosphorylation. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrea, K.G.; Robert, H.L. Is Fast Food Addictive? CDAR 2011, 4, 146–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiolero, A.; Wietlisbach, V.; Ruffieux, C.; Paccaud, F.; Cornuz, J. Clustering of Risk Behaviors with Cigarette Consumption: A Population-Based Survey. Prev. Med. 2006, 42, 348–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzengruber, D.; Klump, K.L.; Thornton, L.; Brandt, H.; Crawford, S.; Fichter, M.M.; Halmi, K.A.; Johnson, C.; Kaplan, A.S.; LaVia, M.; et al. Smoking in Eating Disorders. Eat. Behav. 2006, 7, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruschena, D.; Mullen, P.E.; Palmer, S.; Burgess, P.; Cordner, S.M.; Drummer, O.H.; Wallace, C.; Barry-Walsh, J. Choking Deaths: The Role of Antipsychotic Medication. Br. J. Psychiatry 2003, 183, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuels, R.; Chadwick, D.D. Predictors of Asphyxiation Risk in Adults with Intellectual Disabilities and Dysphagia. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2006, 50, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaal, Y.; Fresard, E.; Rabia, S.; Chatton, A.; Rothen, S.; Pomini, V.; Grasset, F.; Borgeat, F.; Zullino, D. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Weight Gain Associated with Antipsychotic Drugs. Schizophr. Res. 2007, 91, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tek, C.; Ratliff, J.; Reutenauer, E.; Ganguli, R.; O’Malley, S.S. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Pilot Study of Naltrexone to Counteract Antipsychotic-Associated Weight Gain: Proof of Concept. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2014, 34, 608–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, A.E.; Laraia, B.; Daubenmier, J.; Hecht, F.M.; Lustig, R.H.; Puterman, E.; Adler, N.; Dallman, M.; Kiernan, M.; Gearhardt, A.N.; et al. Putting the Brakes on the “Drive to Eat”: Pilot Effects of Naltrexone and Reward-Based Eating on Food Cravings among Obese Women. Eat. Behav. 2015, 19, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Du, J.; Zhan, G.; Wu, Y.; Su, H.; Zhu, Y.; Jarskog, F.; Zhao, M.; Fan, X. Naltrexone and Bupropion Combination Treatment for Smoking Cessation and Weight Loss in Patients with Schizophrenia. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanek, J.K.; Metzgar, C.J.; Hsiao, P.Y.; Piehowski, K.E.; Nickols-Richardson, S.M. Increase in Cognitive Eating Restraint Predicts Weight Loss and Change in Other Anthropometric Measurements in Overweight/Obese Premenopausal Women. Appetite 2015, 87, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westenhoefer, J.; Engel, D.; Holst, C.; Lorenz, J.; Peacock, M.; Stubbs, J.; Whybrow, S.; Raats, M. Cognitive and Weight-Related Correlates of Flexible and Rigid Restrained Eating Behaviour. Eat. Behav. 2013, 14, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchanturia, K.; Davies, H.; Roberts, M.; Harrison, A.; Nakazato, M.; Schmidt, U.; Treasure, J.; Morris, R. Poor Cognitive Flexibility in Eating Disorders: Examining the Evidence Using the Wisconsin Card Sorting Task. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e28331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, S.; Gnatt, I.; Phillipou, A.; Nedeljkovic, M. Cognitive Flexibility in Acute Anorexia Nervosa and after Recovery: A Systematic Review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 81, 101905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindvall Dahlgren, C.; Rø, Ø. A Systematic Review of Cognitive Remediation Therapy For Anorexia Nervosa—Development, Current State and Implications for Future Research and Clinical Practice. J. Eat. Disord. 2014, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leppanen, J.; Adamson, J.; Tchanturia, K. Impact of Cognitive Remediation Therapy on Neurocognitive Processing in Anorexia Nervosa. Front. Psychiatry 2018, 9, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowie, C.R. Cognitive Remediation for Severe Mental Illness: State of the Field and Future Directions. World Psychiatry 2019, 18, 274–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).