Abstract

The link between eating rate and energy intake has long been a matter of extensive research. A better understanding of the effect of food intake speed on body weight and glycemia in the long term could serve as a means to prevent weight gain and/or dysglycemia. Whether a fast eating rate plays an important role in increased energy intake and body weight depends on various factors related to the studied food such as texture, viscosity and taste, but seems to be also influenced by the habitual characteristics of the studied subjects as well. Hunger and satiety quantified via test meals in acute experiments with subsequent energy intake measurements and their association with anorexigenic and orexigenic regulating peptides provide further insight to the complicated pathogenesis of obesity. The present review examines data from the abundant literature on the subject of eating rate, and highlights the main findings in people with normal weight, obesity, and type 2 diabetes, with the aim of clarifying the association between rate of food intake and hunger, satiety, glycemia, and energy intake in the short and long term.

1. Introduction

Obesity is linked to several metabolic disturbances such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), atherosclerosis and heart disease [1]. Extensive research has been conducted in order to clarify if simple advice such as eating at a slower rate or eating foods of different texture could be effective in curtailing energy intake and weight gain in the long term as well as if such strategies could play a role in glycemia.

The association of obesity with a fast eating rate has been shown both in normoglycemic as well as in subjects with T2DM [2,3,4,5]. In addition, multiple studies have shown that engaging in a fast eating rate results in increased BMI [6]. A retrospective eight-year study compared three groups of male workers according to their speed of eating and found that the fast-eating group had a higher mean weight gain [7]. Accordingly, in a three years follow-up study of normal-weight individuals, the risk of gaining weight was increased in those that reported eating faster [8].

Eating rate can be measured in g or kcal of food consumed per min. Satiety, or intermeal satiety (i.e., the feeling of fullness throughout the intermeal interval) and hunger (i.e., the conscious sensation reflecting a mental urge to eat) are usually measured via visual analog scales (VAS) and are self-reported, and so remain subjective, although they are generally methodologically accepted [9,10]. It is unclear if the effect of test meals on hunger and satiety in acute experiments and subsequent energy intake apply in everyday life. Additionally, different study groups, i.e., healthy individuals vs. subjects with diabetes could respond differently, not to mention different BMI groups. Constant emerging data concerning anorexigenic and orexigenic peptides make their potential association to corresponding alterations in hunger and satiety a promising field.

Eating rate could be attributed to a person’s behavioral characteristics as well, as it seems that subjects who eat a certain product faster would also consume another product at a faster rate [11]. When monozygotic twin pairs were compared to dizygotic twins, a higher correlation of eating rate was shown, perhaps pointing to a genetic contribution to eating rate [12].

Most of the relevant literature converges to support the notion that eating at a faster rate leads to increased energy intake [13]. Less evidence points towards increased satiety after manipulated eating rate [13].

The present review aims to untangle the labyrinthine landscape in the field of eating speed manipulation, which is comprised of very heterogeneous interventions, by attempting to interpret the relevant literature towards potential unifying concepts. It also presents a collection of practical devices which are being tested towards the end of food intake manipulation as a means of controlling body weight.

Herein, we present the most representative studies examining eating rate, food texture/density and masticatory cycles and divide them depending on the subject groups (healthy, obese and individuals with diabetes). Two authors independently conducted an online PubMed search using relevant key words; eating rate, eating speed, fast eating, rapid eating, slow eating combined, with additional key words such as body mass index, body weight, and obesity, diabetes, glycemia, glucose. Studies in patients with eating disorders (binge eating, bulimia or anorexia) were excluded as well as studies with no clear manipulation of eating rate, those concerning children/adolescents and studies with language restrictions. Lastly, we included some novel studies concerning devices that manipulate eating rate.

2. Studies Concerning Healthy Individuals

i. Manipulating Eating Rate

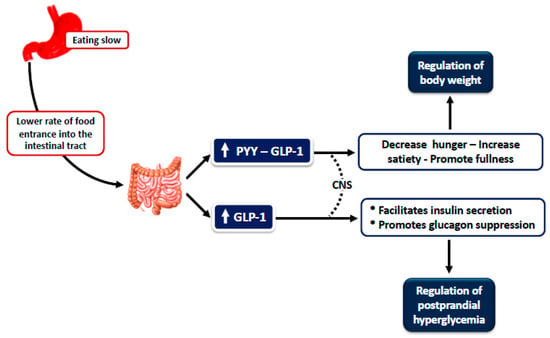

Andrade et al. examined healthy women (including normal weight, overweight and obese) and found that satiety, using VAS, was significantly higher and energy intake was lower when a slower eating rate was applied, whereas hunger and desire to eat did not differ at the end of the meal [14]. Our group examined the effect of eating rate on the postprandial levels of appetite-regulating hormones in healthy individuals (both normal weight and overweight) and produced a hypothesis that suggests that eating at a slower rate is associated with increased satiety, higher plasma levels of anorexigenic peptides PYY (peptide tyrosine tyrosine) and GLP-1 (glucagon like peptide 1) and lower plasma levels of the orexigenic peptide ghrelin [15]. Subjects consumed an identical meal at two separate sessions of different durations, namely, 5 min versus 30 min. We found that postprandial responses of plasma PYY and GLP-1 were higher after the 30- vs. the 5-min meal, but postprandial levels of ghrelin did not differ significantly (whilst there was a trend for lower ghrelin levels at the 120-min time point for the 30-min meal) (Figure 1). Thus, we speculated that eating quickly elicits weaker anorexigenic gut hormone responses. However, a potent effect on ghrelin was not shown. Consistent with other studies, glycemia and insulin levels were not different between the two meals. However, we did not measure energy intake at the subsequent meal, or the time elapsed until initiation of the next meal; therefore, whether the documented effects influence satiety remains unclear [15].

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of gut hormone responses and clinical outcomes in healthy individuals eating at a slow rate [15].

One would wonder if food intake and, subsequently, weight management could be manipulated via all aforementioned parameters or if behavioral patterns are equally or even more important in that aspect. A potential hereditary influence in monozygotic twins has already been mentioned [12]. The role of individual eating patterns on food intake and satiety, when the rate of eating diverts from the subject’s habituated rate, i.e., examining the effect of an increase or decrease in eating rate, as well as the effect of taking a break while eating in so-called linear and decelerated female eaters, was studied [16]. Interrupting the meal has been thought to reduce eating rate and food intake. Women eating at a decelerated rate presented with a difficulty increasing their rate of eating and under control conditions reported higher satiety compared to the linear eaters. They also ate significantly less when the meal was short and when eating rate was increased, while the opposite was found for linear eaters. No effect on food intake was found with a decreased eating rate or meal interruption on decelerated eaters, while linear eaters ate significantly more food when the meal was interrupted, but less food when eating rate was decreased [16].

The question of whether eating rate is also influenced by ongoing perceptual estimates of the volume of food remaining and by a corresponding adjustment of food intake during a meal, has also been examined [17]. Subjects were “tricked” into eating more or less than what appeared and were unaware that their portion size had been manipulated. Participants who saw 300 ML but actually consumed 500 ML ate at a faster rate than participants who saw 500 ML but consumed 300 ml. When food disappeared faster or slower than anticipated, subjects adjusted their rate of eating accordingly. Eating rate may also be controlled via visual feedback and is not considered a simple reflexive response to orosensory stimulation. Irrespective of food type, participants reported greater fullness at the end of the meal if they had consumed the 500 ML portion compared to participants who had eaten the 300 ML portion [17].

The association between eating rate and basal metabolic rate (BMR) and its association with energy intake requirements has revealed interesting results [18]. A possible driving force of energy intake could be an individual’s energy requirements, estimated via measurement of BMR. Basal metabolic rate was positively associated with eating rate, independently of BMI. Thus, one could possibly attribute faster eating rates with subsequent higher food intake to adaptive behaviors in order to meet higher energy requirements [18]. Furthermore, it seems that eating rate is relatively stable within an individual and is not dependent on meal palatability, sex, body composition and reported appetite. That is, the recorded fast eating rate at a meal predicts a similar rate along with increased energy intake at subsequent meals [19].

Normal-weight volunteers were examined while consuming a meal in either 6 min or 24 min [20]. Slower eating suppressed ghrelin to a greater extent, and there seemed to be a strong correlation between postmeal ghrelin and post-test ad libitum meal intake, i.e., individuals eating at a slower rate consumed a smaller quantity of the subsequent ad libitum meal, and reported feeling fuller from the 30-min time point and for the rest of the one-hour study. On the contrary, the normal eating rate group (6 min) showed a greater PYY response compared to the slow rate group and reported greater satisfaction from the meal. Patients underwent an functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) test 2-h postmeal while undergoing a memory task concerning the meal. The slower eating subgroup reported more accurate portion size memory with a linear relationship between time taken to make portion size decisions and the BOLD (blood-oxygen-level dependent) response in satiety and reward brain regions [20]. Detailed information regarding the aforementioned studies are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Studies examining the effect of manipulating eating rate, food texture, and mastication speed in healthy individuals.

ii. Manipulating Food Texture

Texture of food, on the other hand, seems to play a significant role in eating rate as well, which subsequently influences food intake (Τable 1). Forde et al. examined healthy, normal-weight individuals and concluded that food of softer texture and high savory taste intensity leads to increased energy intake, increasing the average eating rate in the softer texture food by approximately 20% [21]. In the same context, the difference in energy intake (in kcal and g) after eating different food textures showed that harder foods led to a 16% lower intake compared to softer foods [22]. The overall eating rate of hard texture food was 32% lower compared to that of softer food. However, this did not decrease energy intake when subjects were introduced to a meal five hours later, thereby questioning the effect of food texture on long-term weight management [22].

The combined impact of eating rate and meal density was studied in 20 healthy individuals eating at two different speeds (fast vs. slow; 15 min longer when slower rate was applied) as well as using two different energy density meals [23]. Energy density was defined as the metabolizable energy per gram of food (kcal/g). Energy intake was higher when participants ate at a faster rate, but this effect applied only to high density food, whereas the effect of energy density οn energy intake was observed at both eating rates, but was potentiated by 43% when faster eating rates were implemented on high density meals. The postprandial area under the curve (AUC) for insulin, PYY and GLP-1 were higher during the fast and high energy density trials, but appetite remained relatively unaffected, as did glucose and ghrelin levels. The authors concluded that a faster eating rate had a greater effect on energy intake when a high energy density compared to a low energy density was consumed and, thus, it seems that adopting an eating pattern that includes frequent consumption of high energy dense food at a fast rate may eventually promote overeating [23].

Foods differing in viscosity (liquid vs. semiliquid) lead to differences in ad libitum intake and meal termination, producing differences in eating rate [24]. Food intake seems to increase with decreasing viscosity and the mechanisms involved are, at least to a certain extent, the shorter sensory exposure time and transit time food spends in the oral cavity. This effect, tested both in the real world as well as in the laboratory setting, was not due to differences in energy, macronutrient content or energy density, as they were all identical (and thus potential confounders in liquid–solid differences in satiety were controlled) [24]. The eating rate of the liquid product was significantly higher than the eating rate of the semisolid product, suggesting that a liquid is, as expected, eaten at a much higher rate and does not stay long in the oral cavity compared to the solid product. The time a product actually stays in the oral cavity could be an important parameter explaining the differences in satiety responses between liquids and solids, since the exposure time to sensory receptors in the oral cavity is longer for taste, smell, etc. Furthermore, in this study there were no differences in satiety after ad libitum intake—despite the differences in food intake—supporting the fact that subjects did not feel less full after the larger consumption of the liquid product. Perhaps energy intake and satiety do not correlate well in both liquids and solids. Interestingly, when the same amounts of calories are consumed, the subjective feelings of satiety are different and when the subjective feelings of satiety are the same, the amount of calories consumed is different. Multiple studies have shown that hunger and satiety are not always correlated to energy intake and certainly, in that aspect, do not foresee weight gain [24]. The effect of lower viscosity (produced by the modification of b-glucan content) produced a greater decrease in postprandial ghrelin and a greater postprandial increase in satiety, plasma glucose, insulin, cholecystokinin, PYY, and GLP-1, accentuating the importance of rheological properties of food in normal-weight subjects [25]. The high-viscosity vs. the low-viscosity oat bran beverage induced smaller postprandial glucose and insulin responses, consistent with delayed gastric emptying [25].

Different macronutrient consumption tendencies and their particular association with food intake and ingestion time have been measured in normal-weight participants [26]. Marked differences were observed in eating rate between foods, i.e., even within a food category such as solid foods, eating rate differed up to 30 times. Eating rate was positively associated with energy intake and inversely associated with energy density. For every 10 g/min increase in eating rate, energy intake increased by 1%. Carbohydrate, protein, and fiber content were inversely associated with eating rate in contrast to fat, which showed no association [26]. This could relate to the low water content or the increased density that would necessitate increased mastication. Given that fat is a fundamental determinant of energy density, its nonassociation with eating rate may imply that fat has minimal inhibitory effect on eating rate, as seen in its effect to elicit satiation [27].

iii. Manipulating Masticatory Cycles

Another intriguing aspect of food intake regulation is the masticatory cycles a person undergoes before swallowing a certain food (Τable 1). Energy intake was assessed using an ad libitum specific test meal high in carbohydrates, after instructing the subjects to eat it in two separate sessions, where the number of masticatory cycles as well as the duration of the meal were different [28]. Increasing masticatory cycles before swallowing increases satiety, as measured by subjective appetite questionnaires, but does not lead to a difference in food intake. There was a trend towards an effect of masticatory cycles on ghrelin, with lower ghrelin following the higher number of cycles, as well as higher plasma glucose, insulin, GIP and CCK concentrations. Ghrelin and CCK did not seem to correlate with increased satiety. The authors attributed the findings, among others, to the property of decreasing the particles’ size, subsequently increasing the bioavailability of nutrients [28].

In lieu of commonly used methods to quantify hunger and energy intake, Mattes et al. showed that in normal-weight participants, hunger ratings are not a valid index of energy intake computed from food records or number of eating occurrences, since participants often ate when hunger ratings were low. Nevertheless, eating when not hungry occurred less often than not eating when hungry [29].

3. Studies Concerning Patients with Overweight/Obesity

Numerous studies have shown that among the multifactorial nature of obesity, the detrimental effect of genes prevails among all [30]. Nevertheless, several papers have dealt with the impact of manipulating environmental factors and still the question of whether all findings could apply in the long term remains. By the term satiation, we describe the process taking place during a meal that leads to the termination of eating, consequently affecting and controlling energy intake (intrameal satiety). Satiety, on the other hand, describes the inhibition of further eating, decline of feelings of hunger, increase in fullness after a meal has finished (postingestive satiety or intermeal satiety). It could, therefore, be determined by the ad libitum energy intake during the next meal [10]. Eating pattern differences between subjects include bite size, eating rate, masticatory cycles, speed, etc. [31]. A number of studies (presented in Table 2) have sought these differences between obese and normal-weight individuals, but the literature has not yet yielded conclusive results. It would be very significant if people with obesity could benefit from small everyday interventions, once proven that they might confer positive results in weight management.

Table 2.

Studies examining the effect of manipulating eating rate and mastication speed in patients with overweight/obesity.

i. Manipulating Eating Rate

Rapid eating does seem to be more frequent among overweight/obese patients. When given the same advice regarding eating rate, overweight/obese individuals ate at a faster rate compared to a normal-weight group [32]. Normal-weight and obese volunteers were studied after consumption of a meal at three different eating rates (7-, 14- and 28-min duration) evaluating the effect of eating rate on postprandial fullness and associated postprandial hormonal responses (PP, GLP-1, PYY, cholecystokinin, leptin and neuropeptide Y) and energy intake during the subsequent ad libitum meal [9]. Postprandial glucose and insulin responses were not affected by eating rate, and although eating at a faster rate altered peak PP concentrations and periprandial CCK response when compared to the moderate and slow eating rate, they were not different between meals, indicating no persisting effect. No effect was shown on the energy intake of the subsequent ad libitum meal at any eating rate. These findings imply that eating rate does not influence satiety or fullness despite a weak effect on the periprandial hormonal response [9]. This is in contrast to the findings of our study, in which postprandial PYY and GLP-1 were decreased when increasing the eating rate of a test meal [15]. Comparing the effect of eating rate on energy intake between normal-weight and overweight/obese subjects during an ad libitum meal, energy intake differed in the normal-weight but not in the overweight/obese subjects [33]. Martin et al. examined overweight and obese men and women and showed that a slow eating rate also decreased food intake [34]. However, this was shown only in men. Among other explanations for this discrepancy, authors hypothesized that men eat faster than women, and so it would be possible that subgroups of women who do eat at a faster rate could be more sensitive to different eating rates. Nevertheless, appetite was affected by the decelerated eating pattern during the combined-rate meal (a meal starting at baseline speed followed by a 50% slower eating rate) [34]. When a bite-counter device was used to manipulate eating rate, a decrease in energy intake accompanied slow bite rate, but only in those who habitually ate larger quantities of food during a meal (more than 400 kcal) [35].

ii. Manipulating Masticatory Cycles

Smit et al. showed that subjects reduced their energy intake by 12% when chewing a standard meal 35 vs. 10 times per mouthful [36]. Although instructing participants to chew more ultimately led to faster chewing, it still resulted in a longer meal duration (a near 100% increase). Postprandial fullness ratings, however, did not differ. When habitual chewing pattern was assessed and compared between normal-weight and obese participants, no difference was found [36].

In an older publication, the hypothesis that decreasing ingestion rate would lead to smaller energy consumption was not confirmed and there were no significant differences between normal- weight and overweight/obese subjects [37]. Apparently, there are consistent individual differences in eating behavior that characterize faster compared to slower eaters, i.e., faster eaters were more sensitive to variations in bite size and to the texture of the food but, as aforementioned, these were not related to the amount of energy intake [37].

A study in severely/morbidly obese patients assessed the relationship between eating rate and parameters of eating behavior [38]. Among others, rapid eating was considered a significant risk factor for complications after bariatric surgery [38]. Female patients suffering from severe or morbid obesity, most of which were awaiting bariatric surgery, took a self-administered questionnaire that explored eating rate, degree of chewing, signs of prandial overeating and scores of emotionality, externality and restrained eating [39]. Fifty percent of the examined patients reported rapid eating, which was also associated with the feeling of having eaten too much. Additionally, there was an inverse relationship between eating rate and degree of chewing [39].

4. Studies Concerning Subjects with Diabetes Mellitus

In a multicenter center study examining subjects with T2DM using a self-reported questionnaire, BMI seemed to increase with increases in the rate of eating [40]. A high prevalence of rapid eaters was noted (61.5%), compared with studies in healthy controls, i.e., 36.5–50.8% [3,4,40]. To our knowledge, comparison studies have not been conducted between subjects with and without diabetes regarding their eating rate.

Type 2 diabetic individuals seem to be more resistant to weight loss in comparison to nondiabetic groups, an observation which is not fully understood [41]. Based on the studies supporting that the incretin effect is blunted in obese subjects with T2DM, our group opted to study the effect of eating rate on hunger, satiety, and on the enteroendocrine hormone axis in overweight/obese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus using a standard test meal of 300 ML of ice-cream consumed at two different rates [42,43]. Postprandial levels of insulin and glucose were not affected by eating rate, nor were ghrelin, PYY, and GLP-1, but slow spaced eating did result in a decrease in hunger and an increase in fullness [42].

Subjects with T2DM or hyperlipidemia were examined using a questionnaire assessing their eating rate [5]. Fast eating male patients displayed a higher BMI, but that did not apply to females, perhaps due to their smaller number. However, subjects were not analyzed separately, providing confounding factors in the interpretation of the results [5]. Details with reference to the aforementioned studies are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Studies concerning patients with diabetes mellitus and the effect of eating rate and mastication on satiety, gut hormones, and glycemic response.

5. Devices Manipulating Eating Rate

i. Noninvasive Oral Devices

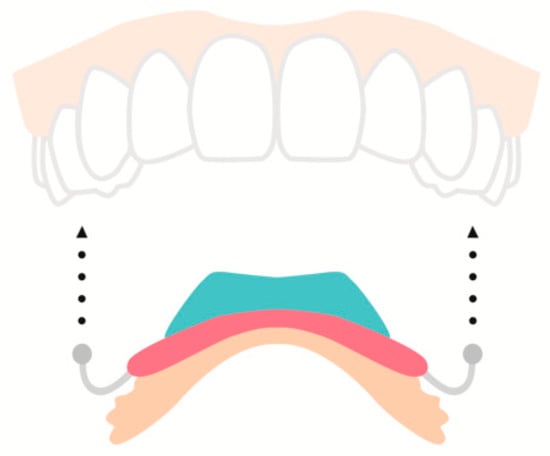

An oral device, custom-made for each individual, designed to decelerate eating rate by decreasing oral volume and bite size was studied in obese/overweight individuals in a 4-month open label trial (Figure 2) [47]. The device is placed in the upper palatal space and secured by metal clasps around the teeth before initiation of the meal and is removed after termination. Participants exhibited a 5.2% weight loss while using the aforementioned device accompanied by a hypocaloric diet. Participants reported eating slower even when the device was not used [47].

Figure 2.

This oral device is placed in the upper palatal space and is secured by metal clasps right before initiation of eating. A microchip (shown in blue) records the device’s temperature in order to monitor the user’s compliance. It is designed to decelerate eating rate by decreasing oral volume and the size of each bite [47].

Intraoral splints for both the upper and lower jaw, extending about 3 mm over the premolars and molars, reduce oral capacity by 25% and alter eating behavior without preventing users from eating [48]. At a 12-month follow-up in a study where the device was used for a total of 4 to 8 weeks, all participants exhibited weight loss of up to 5% and an impressive 67% experienced 10% weight loss [48].

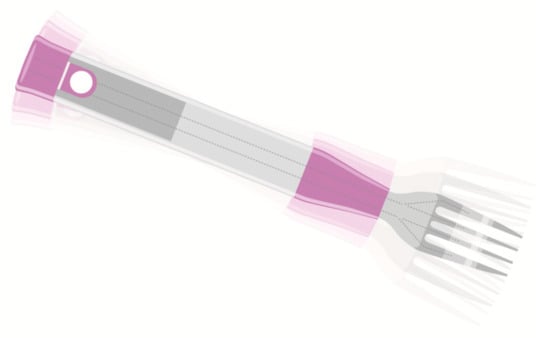

Furthermore, objects of everyday use, like cutlery, could be potentially modified in order to decrease eating rate, i.e., smaller spoons resulted in a decrease in ad libitum food intake by 8%, decreasing both mean bite size and eating rate [49]. A smart fork has been designed in order to assist the user to maintain a slow eating rate by determining meal duration and calculating total number of bites (Figure 3) [50]. The device vibrates and a red-light indication appears every time eating rate is accelerated (more than one bite per 10 s) [50]. A three-armed parallel randomized controlled trial consisting of a group using the fork with vibrating feedback, a second group using the fork with access to online data (for eating rate and success ratio feedback), and a third group using the fork with no feedback resulted in weight loss in the intervention groups [51]. At a follow-up, participants maintained a decreased eating rate by longer spacing between bites and a lower bite rate [51].

Figure 3.

A smart fork that helps the user to decrease eating rate by calculating eating speed and meal duration. A red-light indication and a vibration appear when eating rate is accelerated [50].

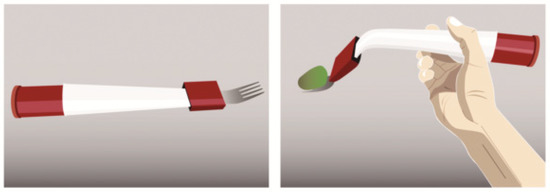

A pneumatic fork that changes its body shape by inflating and deflating through a small pump and valve has also been used for the detection of accelerated eating rate (Figure 4) [52]. It bends when deflated, making it unable to eat with [52].

Figure 4.

A pneumatic fork that changes its body shape by inflating and deflating through a small pump and valve depending on the detected eating rate [52].

ii. Wearable Devices

The detection and monitoring of eating habits can also be conducted using smart eyeglasses with integrated electromyography electrodes on each side that provide skin contact with the ears [53]. Via high detection of chewing and eating events (ca 80%), the device could possibly contribute to dietary monitoring [53]. A device providing visual feedback via an application on a smartphone attempts to manage body weight by manipulation of eating rate [54]. An electronic scale is connected via Bluetooth with the smartphone and measures the gradual reduction in food on the plate. Self-recording of hunger and fullness is also available on the screen (Figure 5) [54].

Figure 5.

A custom-made electronic scale that is connected via bluetooth with a smartphone application measuring the reduction of the food placed on the scale along with self-recording of hunger and fullness [54].

6. Effect of Eating Rate on Glycemic Response

Studies manipulating eating rate conducted directly to evaluate its effect on glycemia are scarce. Different eating methods can affect eating rate which may in turn influence postprandial glucose responses. Eating methods (spoon, chopsticks and fingers), and a mastication manipulation method as potential means of lowering glycemic response, taking into consideration that the amount of food provided per mouthful and chewing time differs between eating methods, have been studied [44]. Eating with chopsticks resulted in decreased postprandial glucose response, higher chewing rate (chews per mouthful divided by chewing time), smaller bite size, smaller number of chews per mouthful and a decreased eating rate [44]. Healthy participants’ glycemic response (via finger-prick) was studied while consuming large vs. small rice particles [45]. Gastric emptying (using the sodium [13C] acetate breath test) was also assessed. Small particles elicited a significantly greater glycemic and insulin response compared to large particles and induced faster gastric emptying [45]. Modifying the mastication rate could alter the glycemic index of rice, i.e., less mastication cycles induced significantly lower glycemic response and lower glycemic index [46].

Glycemia (assessed with HbA1c) showed no association with increased eating rate reported via a self-reported questionnaire in subjects with type 2 diabetes, [40]. However, this would be expected, presumably via an increase in postprandial hyperglycemia [55]. Increased eating rates may induce a faster entrance of glucose into the circulation, requiring an immediate response from β-cells. In type 2 diabetes, the delay of insulin secretion after a meal is a major pathophysiological feature of postprandial hyperglycemia: restoration of early insulin secretion in subjects with type 2 diabetes after a mixed meal resulted in adequate suppression of endogenous lipolysis and lower plasma glucose levels in the postprandial period [56]. Moreover, in subjects with diabetes, the delay in gastric emptying and intestinal glucose absorption after a meal by α-glucosidase inhibitors or somatostatin, improved time differences between postprandial plasma glucose and insulin increases, thus leading to lower postprandial hyperglycemia [57,58,59].

Regarding the effect of eating rate on insulin resistance, a significant progressive increase in homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was found with increases in relative eating rate in healthy middle-aged normal-weight individuals, suggesting that eating rate is independently associated with insulin resistance [60]. These observations could be explained by the rapid entrance of glucose into the circulation in the beginning of the meal, which may aggravate postprandial hyperinsulinemia, leading in turn to increased fluctuations of circulating blood glucose levels [56,61].

7. Conclusions

Hitherto, a substantial amount of studies has pointed to the direction that eating rate is an important factor influencing energy intake in acute settings, such that those who eat quickly seem to eat more compared to those who eat at a slower pace, all within a meal. This tendency increases satiation, but in most circumstances, it does not alter satiety responses and energy intake in subsequent meals, nor does it increase the intermeal interval. Thus, it would not translate into measurable behavioral changes affecting weight gain. Relevant studies show dissimilar results. The question of whether eating quickly could be used as a predictor of the risk of gaining weight in the long term remains. In addition, whether eating rate acutely or chronically affects glycemia remains a largely unanswered question. Food texture and hereditary/habitual characteristics along with eating rate are important features that affect food intake, eliciting a different response depending on the setting and the population studied. Neuroendocrine gut hormone response studies, assessing ad libitum energy intake at different eating rates could be useful in order to quantify the basis of both satiation and satiety produced by different patterns of eating.

Author Contributions

G.A. and S.S. Research, writing, proof reading. A.K. Conceptualization, proof read. G.D. Provided input on text, provided Figure 1, proof read. All contributed to writing and revisions. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Koliaki, C.; Liatis, S.; Kokkinos, A. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: Revisiting an old relationship. Metabolism 2019, 92, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruyama, K.; Sato, S.; Ohira, T.; Maeda, K.; Noda, H.; Kubota, Y.; Nishimura, S.; Kitamura, A.; Kiyama, M.; Okada, T.; et al. The joint impact on being overweight of self reported behaviours of eating quickly and eating until full: Cross sectional survey. BMJ 2008, 337, a2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otsuka, R.; Tamakoshi, K.; Yatsuya, H.; Murata, C.; Sekiya, A.; Wada, K.; Zhang, H.M.; Matsushita, K.; Sugiura, K.; Takefuji, S.; et al. Eating fast leads to obesity: Findings based on self-administered questionnaires among middle-aged japanese men and women. J. Epidemiol. 2006, 16, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, S.; Katagiri, A.; Tsuji, T.; Shimoda, T.; Amano, K. Self-Reported rate of eating correlates with body mass index in 18-y-old Japanese women. Int. J. Obes. 2003, 27, 1405–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, S.; Akamine, Y.; Okabe, T.; Koya, Y.; Haraguchi, M.; Miyata, Y.; Sakai, T.; Sakura, H.; Sasaki, T. Rate of eating and body weight in patients with type 2 diabetes or hyperlipidaemia. J. Int. Med. Res. 2002, 30, 442–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohkuma, T.; Hirakawa, Y.; Nakamura, U.; Kiyohara, Y.; Kitazono, T.; Ninomiya, T. Association between eating rate and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Obes. 2015, 39, 1589–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanihara, S.; Imatoh, T.; Miyazaki, M.; Babazono, A.; Momose, Y.; Baba, M.; Uryu, Y.; Une, H. Retrospective longitudinal study on the relationship between 8-year weight change and current eating speed. Appetite 2011, 57, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamane, M.; Ekuni, D.; Mizutani, S.; Kataoka, K.; Sakumoto-Kataoka, M.; Kawabata, Y.; Omori, C.; Azuma, T.; Tomofuji, T.; Iwasaki, Y.; et al. Relationships between eating quickly and weight gain in japanese university students: A longitudinal study: Eating quickly and overweight. Obesity 2014, 22, 2262–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karl, J.P.; Young, A.J.; Montain, S.J. Eating rate during a fixed-portion meal does not affect postprandial appetite and gut peptides or energy intake during a subsequent meal. Physiol. Behav. 2011, 102, 524–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blundell, J.; de Graaf, C.; Hulshof, T.; Jebb, S.; Livingstone, B.; Lluch, A.; Mela, D.; Salah, S.; Schuring, E.; van der Knaap, H.; et al. Appetite control: Methodological aspects of the evaluation of foods. Obes. Rev. 2010, 11, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zijlstra, N.; Mars, M.; Stafleu, A.; de Graaf, C. The effect of texture differences on satiation in 3 pairs of solid foods. Appetite 2010, 55, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, C.H.; van Jaarsveld, C.H.; Boniface, D.; Carnell, S.; Wardle, J. Eating rate is a heritable phenotype related to weight in children. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 1560–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E.; Almiron-Roig, E.; Rutters, F.; de Graaf, C.; Forde, C.G.; Tudur Smith, C.; Nolan, S.J.; Jebb, S.A. A systematic review and meta-analysis examining the effect of eating rate on energy intake and hunger. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 123–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, A.M.; Greene, G.W.; Melanson, K.J. Eating slowly led to decreases in energy intake within meals in healthy women. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2008, 108, 1186–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokkinos, A.; le Roux, C.W.; Alexiadou, K.; Tentolouris, N.; Vincent, R.P.; Kyriaki, D.; Perrea, D.; Ghatei, M.A.; Bloom, S.R.; Katsilambros, N. Eating slowly increases the postprandial response of the anorexigenic gut hormones, peptide YY and Glucagon-Like Peptide-1. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 95, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zandian, M.; Ioakimidis, I.; Bergh, C.; Brodin, U.; Södersten, P. Decelerated and linear eaters: Effect of eating rate on food intake and satiety. Physiol. Behav. 2009, 96, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, L.L.; Ferriday, D.; Bosworth, M.L.; Godinot, N.; Martin, N.; Rogers, P.J.; Brunstrom, J.M. Keeping pace with your eating: Visual feedback affects eating rate in humans. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, C.J.; Ponnalagu, S.; Bi, X.; Forde, C. Does basal metabolic rate drive eating rate? Physiol. Behav. 2018, 189, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrickerd, K.; Forde, C.G. Sensory influences on food intake control: Moving beyond palatability: Sensory influences on food intake. Obes. Rev. 2016, 17, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawton, K.; Ferriday, D.; Rogers, P.; Toner, P.; Brooks, J.; Holly, J.; Biernacka, K.; Hamilton-Shield, J.; Hinton, E. Slow down: Behavioural and physiological effects of reducing eating rate. Nutrients 2018, 11, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forde, C.G.; van Kuijk, N.; Thaler, T.; de Graaf, C.; Martin, N. Texture and savoury taste influences on food intake in a realistic hot lunch time meal. Appetite 2013, 60, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolhuis, D.P.; Forde, C.G.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, H.; Martin, N.; de Graaf, C. Slow food: Sustained impact of harder foods on the reduction in energy intake over the course of the day. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, J.P.; Young, A.J.; Rood, J.C.; Montain, S.J. Independent and combined effects of eating rate and energy density on energy intake, appetite, and gut hormones: Eating rate, energy density, and appetite. Obesity 2013, 21, E244–E252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zijlstra, N.; Mars, M.; de Wijk, R.A.; Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S.; de Graaf, C. The effect of viscosity on ad libitum food intake. Int. J. Obes. 2008, 32, 676–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juvonen, K.R.; Purhonen, A.-K.; Salmenkallio-Marttila, M.; Lähteenmäki, L.; Laaksonen, D.E.; Herzig, K.-H.; Uusitupa, M.I.J.; Poutanen, K.S.; Karhunen, L.J. Viscosity of oat bran-enriched beverages influences gastrointestinal hormonal responses in healthy humans. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viskaal-van Dongen, M.; Kok, F.J.; de Graaf, C. Eating rate of commonly consumed foods promotes food and energy intake. Appetite 2011, 56, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blundell, J.E.; MacDiarmid, J.I. Fat as a risk factor for overconsumption: Satiation, satiety and patterns of eating. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1997, 97, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Hsu, W.H.; Hollis, J.H. Increasing the number of masticatory cycles is associated with reduced appetite and altered postprandial plasma concentrations of gut hormones, insulin and glucose. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 110, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattes, R. Hunger ratings are not a valid proxy measure of reported food intake in humans. Appetite 1990, 15, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The LifeLines Cohort Study; The ADIPOGen Consortium; The AGEN-BMI Working Group; The CARDIOGRAMplusC4D Consortium; The CKDGen Consortium; The GLGC; The ICBP; The MAGIC Investigators; The MuTHER Consortium; The MIGen Consortium; et al. Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature 2015, 518, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferster, C.B.; Nurnberger, J.I.; Levtit, E.B. The control of eating. Obes. Res. 1996, 4, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koidis, F.; Brunger, L.; Gibbs, M.; Hampton, S. The effect of eating rate on satiety in healthy and overweight people—A pilot study. e-SPEN J. 2014, 9, e54–e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Copeland, J.; Dart, L.; Adams-Huet, B.; James, A.; Rhea, D. Slower eating speed lowers energy intake in normal-weight but not overweight/obese subjects. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 114, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.K.; Anton, S.D.; Walden, H.; Arnett, C.; Greenway, F.L.; Williamson, D.A. Slower eating rate reduces the food intake of men, but not women: Implications for behavioral weight control. Behav. Res. Ther. 2007, 45, 2349–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scisco, J.L.; Muth, E.R.; Dong, Y.; Hoover, A.W. Slowing bite-rate reduces energy intake: An application of the bite counter device. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2011, 111, 1231–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, H.J.; Kemsley, E.K.; Tapp, H.S.; Henry, C.J.K. Does prolonged chewing reduce food intake? Fletcherism Revisited. Appetite 2011, 57, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiegel, T.A.; Kaplan, J.M.; Tomassini, A.; Stellar, E. Bite size, ingestion rate, and meal size in lean and obese women. Appetite 1993, 21, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkes, E. Nutritional management of patients after bariatric surgery. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2006, 331, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canterini, C.-C.; Gaubil-Kaladjian, I.; Vatin, S.; Viard, A.; Wolak-Thierry, A.; Bertin, E. Rapid eating is linked to emotional eating in obese women relieving from bariatric surgery. Obes. Surg. 2018, 28, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, A.; Kawai, K.; Yanagisawa, M.; Yokoyama, H.; Kuribayashi, N.; Sugimoto, H.; Oishi, M.; Wada, T.; Iwasaki, K.; Kanatsuka, A.; et al. Self-Reported rate of eating is significantly associated with body mass index in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Japan Diabetes Clinical Data Management Study Group (JDDM26). Appetite 2012, 59, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, M.J.; Boucher, J.L.; Rutten-Ramos, S.; VanWormer, J.J. Lifestyle weight-loss intervention outcomes in overweight and obese adults with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 1447–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelopoulos, T.; Kokkinos, A.; Liaskos, C.; Tentolouris, N.; Alexiadou, K.; Miras, A.D.; Mourouzis, I.; Perrea, D.; Pantos, C.; Katsilambros, N.; et al. The effect of slow spaced eating on hunger and satiety in overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMJ Open Diab. Res. Care 2014, 2, e000013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toft-Nielsen, M.-B.; Madsbad, S.; Holst, J.J. Determinants of the effectiveness of glucagon-like peptide-1 in type 2 diabetes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 86, 3853–3860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Ranawana, D.V.; Tan, W.J.K.; Quek, Y.C.R.; Henry, C.J. The impact of eating methods on eating rate and glycemic response in healthy adults. Physiol. Behav. 2015, 139, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranawana, V.; Clegg, M.E.; Shafat, A.; Henry, C.J. Postmastication digestion factors influence glycemic variability in humans. Nutr. Res. 2011, 31, 452–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranawana, V.; Leow, M.K.-S.; Henry, C.J.K. Mastication effects on the glycaemic index: Impact on variability and practical implications. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 68, 137–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGee, T.L.; Grima, M.T.; Hewson, I.D.; Jones, K.M.; Duke, E.B.; Dixon, J.B. First australian experiences with an oral volume restriction device to change eating behaviors and assist with weight loss. Obesity 2012, 20, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Seck, P.; Sander, F.M.; Lanzendorf, L.; von Seck, S.; Schmidt-Lucke, A.; Zielonka, M.; Schmidt-Lucke, C. Persistent weight loss with a non-invasive novel medical device to change eating behaviour in obese individuals with high-risk cardiovascular risk profile. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James, L.J.; Maher, T.; Biddle, J.; Broom, D.R. Eating with a smaller spoon decreases bite size, eating rate and Ad Libitum food intake in healthy young males. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 120, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermsen, S.; Frost, J.H.; Robinson, E.; Higgs, S.; Mars, M.; Hermans, R.C.J. Evaluation of a smart fork to decelerate eating rate. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 1066–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermsen, S.; Mars, M.; Higgs, S.; Frost, J.H.; Hermans, R.C.J. Effects of eating with an augmented fork with vibrotactile feedback on eating rate and body weight: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuoyi, Z.; Junhyeok, K.; Yumiko, S.; Teng, H.; Pourang, I. Applying a pneumatic interface to intervene with rapid eating behaviour. Stud. Health Technol. Inf. 2019, 257, 513–519. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Amft, O. Monitoring chewing and eating in free-living using smart eyeglasses. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2018, 22, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esfandiari, M.; Papapanagiotou, V.; Diou, C.; Zandian, M.; Nolstam, J.; Södersten, P.; Bergh, C. Control of eating behavior using a novel feedback system. JoVE 2018, 57432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceriello, A. The glucose triad and its role in comprehensive glycaemic control: Current status, future management: Comprehensive glycaemic control in T2D management. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2010, 64, 1705–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriadis, G.; Boutati, E.; Lambadiari, V.; Mitrou, P.; Maratou, E.; Brunel, P.; Raptis, S.A. Restoration of early insulin secretion after a meal in type 2 diabetes: Effects on lipid and glucose metabolism. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 34, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriadis, G.D.; Tessari, P.; Go, V.L.W.; Gerich, J.E. A-Glucosidase inhibition improves postprandial hyperglycemia and decreases insulin requirements in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 1985, 34, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriadis, G.; Hatziagellaki, E.; Alexopoulos, E.; Kordonouri, O.; Komesidou, V.; Ganotakis, M.; Raptis, S. Effects of A-Glucosidase inhibition on meal glucose tolerance and timing of insulin administration in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 1991, 14, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriadis, G.; Tessari, P.; Gerich, J. Effects of a long-acting somatostatin analogue on postprandial hyperglycemia in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 1983, 32, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, R.; Tamakoshi, K.; Yatsuya, H.; Wada, K.; Matsushita, K.; OuYang, P.; Hotta, Y.; Takefuji, S.; Mitsuhashi, H.; Sugiura, K.; et al. Eating fast leads to insulin resistance: Findings in middle-aged Japanese men and women. Prev. Med. 2008, 46, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dandona, P. Minimizing glycemic fluctuations in patients with type 2 diabetes: Approaches and importance. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2017, 19, 498–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).