Abstract

Although adequate hydration is essential for health, little attention has been paid to the effects of hydration among the generally healthy population. This narrative review presents the state of the science on the role of hydration in health in the general population, specifically in skin health, neurological function (i.e., cognition, mood, and headache), gastrointestinal and renal functions, and body weight and composition. There is a growing body of evidence that supports the importance of adequate hydration in maintaining proper health, especially with regard to cognition, kidney stone risk, and weight management. However, the evidence is largely associative and lacks consistency, and the number of randomized trials is limited. Additionally, there are major gaps in knowledge related to health outcomes due to small variations in hydration status, the influence of sex and sex hormones, and age, especially in older adults and children.

Keywords:

fluid; water; dehydration; skin; constipation; kidney; cognition; mood; headache; body weight; systematic review 1. Introduction

Water is essential for life and is involved in virtually all functions of the human body [1]. It is important in thermoregulation, as a solvent for biochemical reactions, for maintenance of vascular volume, and as the transport medium for providing nutrients within and removal of waste from the body [2]. Deficits in body water can compromise our health if they lead to substantial perturbations in body water balance [2]. As with other essential substances, intake recommendations for water are available from various authoritative bodies [e.g., Institute of Medicine (IOM) and European Food Safety Authority (EFSA)], and generally range from 2–2.7 L/day for adult females and 2.5–3.7 L/day for adult males [1,2].

Body water balance depends on the net difference between water gain and water loss. The process of maintaining water balance is described as “hydration”. “Euhydration” defines a normal and narrow fluctuation in body water content, while “hypohydration” and “hyperhydration” refer to a generalized body water deficit or excess, respectively, beyond the normal range. Finally, “dehydration” describes the process of losing body water while “rehydration” describes the process of gaining body water. Dehydration can be further classified based on the route of water loss and the amount of osmolytes (electrolytes) lost in association with the water. Iso-osmotic hypovolemia is the loss of water and osmolytes in equal proportions, which is typically caused by fluid losses induced by cold, altitude, diuretics, and secretory diarrhea. Hyperosmotic hypovolemia occurs when the loss of water is greater than that of osmolytes, and primarily results from insufficient fluid intake to offset normal daily fluid losses (e.g., loss of pure water by respiration and transcutaneous evaporation). Hyperosmotic hypovolemia is exacerbated with high sweat loss (warm weather or exercise) or osmotic diarrhea [3,4].

The normal daily variation of body water is <2% body mass loss (~3% of total body water); thus, hypohydration is clinically defined as ≥2% body mass deficit [5]. The kidneys can regulate plasma osmolality within a narrow limit (±2% or 280 to 290 mOsm/kg) and plasma osmolality between 295 and 300 mOsm/kg is considered mild or impending hyperosmotic hypovolemia, while values greater than 300 mOsm/kg are considered frank hyperosmotic hypovolemia [6,7]. For urine osmolality, values above 1000 mOsm/L are considered elevated and may be a sign of hyperosmotic hypovolemia [6,7]. Finally, it has generally been accepted that a first-morning void urine specific gravity (USG) of less than or equal to 1.020 represents euhydration [7,8].

Hydration status is assessed in a variety of ways in human studies, the most common of which are body weight changes, plasma and/or urine osmolality, and USG. The choice of hydration assessment method and its interpretation is dependent on the type of dehydration; for example, iso-osmotic hypovolemia does not increase plasma or serum osmolality and USG due to the concurrent loss of salt and water. Further complicating the assessment of hydration status are confounding factors such as age and differences in renal function, and these limitations among others have been covered in detail elsewhere [6,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. In addition to assessing hydration status, studies investigating the effects of hydration on health often include measurements of fluid intake, which is usually conducted with dietary assessment methods such as dietary record, diet recall, or food frequency questionnaires. A full assessment of the advantages and limitations of these methods (e.g., difficulties with method validation, challenges in usage among children and the elderly with cognitive issues) are outside the scope of the current review, but have been discussed in detail by others [17,18].

Several reviews on the role of hydration in disease development and progression, as well as the role of hydration in exercise and physical performance have been published [19,20,21,22,23]. However, few reviews are available on the role of hydration in general health, with the exception of a few outcome areas (e.g., weight loss, cognition). An assessment of the role of hydration in general health that thoroughly evaluates the evidence related to the commonly believed benefits of hydration is not available. Thus, the objective of this review was to provide an assessment of the current state of science on hydration and health relevant to the general population. This review includes skin health, neurological, gastrointestinal and renal functions, and body weight and composition in relation to hydration in generally healthy individuals. Publications reviewed include the most current systematic reviews and meta-analyses as well as primary intervention studies published since these reviews.

2. Materials and Methods

The PubMed database was initially searched for reviews on hydration that were published in English. All searches and screening were performed independently by two authors. Reviews were identified using the search terms “hydration” and “dehydration” and selection included those that were conducted using a systematic search process and related to a health area applicable to the general population. In the absence of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, comprehensive narrative reviews that included details on the studies reviewed were included, while opinion pieces were excluded. In addition, hand-searching of references in selected reviews were performed. Key systematic and comprehensive reviews and meta-analyses are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of key hydration reviews.

In order to represent the current state of the literature, primary studies that were not included in the reviews were also identified. Individual searches for clinical intervention trials in generally healthy populations (ages >2 years) and excluding those conducted in diseases populations were conducted in PubMed using the All Fields (ALL) function for terms for hydration and the specific health outcome area. When a systematic review had been identified, the updated search for primary literature overlapped the search in the published systematic review by a year. When a systematic review of a specific topic was not found, the search for primary literature was performed in PubMed starting from its inception. Search terms were compared with the systematic reviews on each topic, when available.

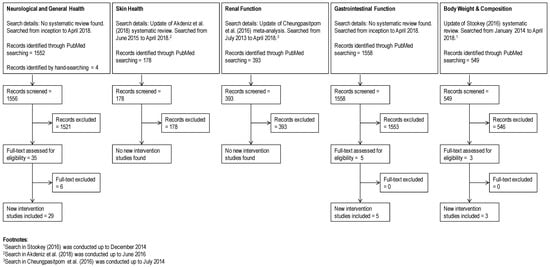

A flowchart documenting the updated search strategy and results is shown in Figure 1. The updated search for weight management used the terms “(fluid OR water OR hydration OR dehydration) AND (weight OR BMI (body mass index) OR circumference)”. For hydration and skin, the terms included “(fluid OR water OR hydration OR dehydration) AND (skin OR epidermal OR transepidermal) NOT (topical OR injection OR injector)”. Search terms for studies on hydration and neurological function were “(water OR hydration OR dehydration) AND (mental OR mood OR cognition OR fatigue OR sleep OR headache)” and studies in diseased population such as dementia were excluded. For gastrointestinal function, the search terms included “(fluid OR water OR hydration OR dehydration) AND (intestinal OR gastric OR constipation) NOT (infant OR cancer)”. Finally, for hydration and renal function, “(fluid OR water OR hydration OR dehydration) AND (kidney OR renal) NOT (infant OR cancer)” was used and studies involving diseased populations such as chronic kidney disease were excluded. Only clinical trials that were not included in systematic reviews are reported in detail in each health outcome section. Information from each primary study was extracted using a pre-determined PICOS (population, intervention, comparison, outcome, study design) table, making sure that any reports of hydration status (e.g., body weight change, plasma osmolality) or fluid intake were recorded.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

Finally, the reporting and methodological qualities of each systematic review and meta-analysis was assessed using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist (http://www.prisma-statement.org/) and A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) 2 (https://amstar.ca/index.php). For meta-analyses, the PRISMA checklist contained 24 required reporting items and three optional items [item 16 (description of additional analyses, if performed), item 19 (reporting of data on risk of bias for each study, if performed), and item 23 (reporting of results of additional analysis, if performed)]. Only the required items were used for scoring. For systematic reviews, 19 items remained after exclusion of optional items and items specific to meta-analyses (i.e., items 13, 14, 15, 21, and 22, which are related to data analysis and risk bias assessment). AMSTAR 2 has 16 items in total, whereby three of these are specific for meta-analysis.

3. Hydration and Health Outcomes

3.1. Skin Health

The skin’s primary functions are to protect the body from external challenges (e.g., chemicals, microbiological materials, and physical stressors), regulate water loss and body temperature, and sense the external environment [30,31,32]. The skin also serves as a reservoir for nutrients and water and contributes to important metabolic activities [30]. The external layer of the skin provides an epidermal barrier, which is composed of 15–20 layers of cornified keratinocytes (corneocytes). The stratum corneum (SC) layer of the epidermis is the primary location of the barrier function; however, both the dermis and the multilayered epidermis are important for maintenance of barrier integrity [32]. Measurements for skin barrier function and hydration include transepidermal water loss (TEWL), SC hydration, “deep” skin hydration, clinical evaluation of dryness, roughness and elasticity, skin relief parameter, the average roughness, evaluation of skin surface morphology, skin smoothness and roughness, extensibility, sebum content, and skin surface pH [24].

For hydration and skin health, a 2018 systematic review was identified [24], which included five intervention studies. Of these studies, four measured surface hydration and reported increased SC hydration following additional intake of 2 L daily of water over a period of 30 days [33,34,35] or additional intake of 1 L per day for a period of 42 days [36]. Of note, only one of these studies [34] compared the effect of additional water consumption in those who habitually consumed below or above the EFSA water requirement (2 L/day). Other studies either assessed participants who were habitually meeting or exceeding the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) requirements [33,35] or failed to report baseline fluid intake [36,37]. In studies that stratified based on baseline water intake [33,34,35], positive impact on skin hydration was evident in participants whose baseline total water intake was less than 3.2 L per day. Measurements of dryness and roughness were reported in one study [36] and these decreased with additional water intake. Measurements of skin elasticity [36], extensibility [33], and the ability of the skin to return to its original state [35] were greater with additional water intake. However, the review authors concluded that the evidence is weak in terms of quantity and methodological quality, and risk of bias in the interventional studies is extremely high [24]. With the exception of providing an explicit statement of questions being addressed and clarifying if a review protocol existed, the 2018 systematic review fulfilled all required PRISMA reporting items (Table 1). The systematic review fulfilled only four out of the 13 required AMSTAR 2 items and lacked clarity on inclusion criteria and study selection, robustness of study selection, and completeness in description and assessment of included studies.

Our updated search resulted in 178 titles (Figure 1), but the vast majority assessed topical applications (e.g., moisturizers), oral ingestion of supplements or herbals, or skin conditions in disease states. No new intervention studies were found when compared with the 2018 systematic review [24].

3.2. Neurological Function

Studies on hydration and neurological function focused on cognition, mood, fatigue, sleep, and headache. In general, the areas of cognition, mood, and fatigue overlap in studies, with some also including sleep and headache outcomes. No single systematic review covered these various topics; however, comprehensive narrative reviews that included discussions on cognition [26] and headache [19] were identified. Thus, our search for primary literature on this topic was not limited to recent literature (Figure 1). After screening, 29 studies were selected and these are summarized in Table 2. Of the cognition studies, eight investigated children and adolescents, 18 adults, and one both children and adults, while two other studies looked at headaches in adults. None of the intervention studies were specific to fatigue or sleep.

Table 2.

Intervention Studies on Hydration and Neurological Function 1.

3.2.1. Cognition, Mood, and Fatigue in Adults

Cognition is a complex function that is composed of several subdomains including different types of memory, attentiveness, reaction time, and executive function. Studies often differ in the specific subdomains assessed as well as the tool used for these measurements. Assessments of mood are also varied across studies, with a number of different types of questionnaires; although a consensus approach does not exist, some validated questionnaires are available [e.g., Bond-Lader, Profile of Moods States (POMS)] and these are the most commonly used.

Several recent reviews of the data in adults have been published (Table 1). Benton and Young [25] concluded that reductions in body mass by >2% due to dehydration are consistently associated with greater fatigue and lower alertness; however, the effects on cognition is less consistent. Masento et al. [26] summarized that severe hypohydration was shown to have detrimental effects on short-term memory and visual perceptual abilities, whereas water consumption can improve cognitive performance, particularly visual attention and mood. These authors also note some of the challenges with studying hydration effects on mood and cognition include variations among subjects (e.g., differing levels of thirst at baseline, habitual intake, and individual adaptation), mediating factors (e.g., water temperature, time of cognition testing, testing environment), variation in types of cognition tests, and distinguishing effects due to thirst and hydration status.

As noted by previous review authors, the studies we identified on attention are heterogeneous in methodology and outcomes. Studies included acute and chronic water consumption, with or without initial dehydration, and measured various types of attention including visual, sustained, and focused (Table 2). Following an overnight fast, acute intake of 25, 200, or 300 mL water improved visual attention [50,38]. Acute intake of water (120 or 330 mL) immediately before testing improved sustained attention in one study [62], but not in another that required overnight fasting prior to consumption of 300 mL water [61]. Both studies assessed sustained attention using the Rapid Visual Information Processing task although the former allowed habitual fluid intake prior to cognition assessments (performed at 11 am or 3 pm), and the latter restricted fluid and food intake for 9 h prior to testing. When dehydration was induced by exercise with or without diuretic (body mass loss of ≥1%), sustained attention decreased compared to exercise with fluid replacement in men [56]. However, a similar dehydration and euhydration protocol did not affect sustained attention in women [55]. Dehydration induced by water deprivation (average body mass loss of 1%) also did not affect visual attention [47]. Under hot conditions (30 °C), dehydration (mean body mass loss of 0.7%) followed by water consumption improved focused attention compared to dehydration without water consumption [48]. Fluid restriction for 28 h (mean body mass loss of 2.5%) did not affect visual, sustained, and divided attention, although subjects reported needing a greater amount of effort and concentration necessary for successful task performance when dehydrated compared to euhydration [59]. Finally, in dose–response studies, attention deteriorated starting at 2% body mass loss [63,64].

Studies on memory are equally heterogeneous in methodology and results. Working memory has been shown to improve following acute intake of water by some [38], but not others [50,61]. When dehydration was induced by exercise with or without diuretic (body mass loss of ≥1%), working memory decreased compared to exercise with fluid replacement in men [56]. However, a similar dehydration and euhydration protocol did not affect working and short-term memory in women [55]. Dehydration following water deprivation (average body mass loss of 1%) increased errors for tests for visual/working memory [47]. Working memory was also unaffected by dehydration (body mass loss of 1 to 3%) induced by two weeks of low-fluid diet (≤40 oz fluid/day or ≤1.2 L/day) [51]. Additionally, more extreme hypohydration (mean body mass loss of 4%) did not affect short-term spatial memory in men [53]. Under hot conditions (30 °C), dehydration (mean body mass loss of 0.7%) followed by water consumption improved episodic memory compared to dehydration without water consumption [48]. Finally, in dose–response studies, short-term memory started deteriorating after 2% body mass loss [63,64].

Compared with attention and memory, fewer studies assessed reaction time. Simple reaction time was unaffected by acute consumption of 200 mL water prior to testing [50]. In another study that evaluated thirst sensation, subjects who were thirsty and provided 0.5–1 L of water had better simple reaction time compared to thirsty subjects who did not consume water [52]. Choice reaction time was unaffected by hypohydration in women (≥1% body mass loss) [55] or in men (mean body mass loss of 4%) [53]. Both simple and choice reaction time were unaffected by hypohydration in women (average body mass loss of 1%) [47].

Other lesser studied cognitive subdomains include grammatical reasoning, spatial cognition, verbal response time, and executive function. Grammatical reasoning was unaffected by hypohydration in women (≥1% body mass loss) [55] or in men (mean body mass loss of 4%) [53]. Flight performance and spatial cognition of healthy pilots were compromised by dehydration (body mass loss of 1 to 3%) induced by 2 weeks of low-fluid diet (≤40 oz fluid/day or ≤1.2 L/day) [51]. Hypohydration following 28 h of fluid restriction (mean body mass loss of 2.5%) decreased verbal response time in women, but increased verbal response time in men and did not affect cognitive-motor speed in either women or men [59]. Smaller degree of dehydration by fluid restriction (mean body mass loss of 1.08%) also did not affect motor speed and visual motor function, visual learning, and cognitive flexibility, but decreased executive function and spatial problem solving [47]. Speed, accuracy, and mental endurance were decreased after 3 h of fluid deprivation (500 g fluid/day), and decreased stability occurred after 35 h [58]. Finally, in dose–response studies, arithmetic efficiency, motor speed, and perceptual motor coordination deteriorated starting at 2% body mass loss [63,64].

Overall, negative emotions such as anger, hostility, confusion, depression, and tension as well as fatigue and tiredness increase with dehydration of ≥1% [53,55,56,59,60] and fluid deprivation (24 h [54]). In men, fluid deprivation (500 g (or ~500 mL) fluid for 24 h) decreased energy ratings after 15 h but did not affect depression, anxiety, and self-confidence [58]. Only one study assessed water consumption following dehydration and demonstrated decreased anxiety, but not depression, when mildly dehydrated subjects (mean body mass loss of 0.2%) were provided with water [48]. Acute water intake by subjects after an overnight fast did not affect various mood ratings [50,61]. Additionally, although thirsty subjects were more tired and tense, provision of 0.5–1 L water did not affect tired and tense ratings [52]. It is possible that mood effects of acute water consumption in these studies were not observed due to the timing of testing relative to water consumption (often >20 min). Indeed, acute water intake (120 and 220 mL) increased alertness assessed after 2 min, but not when assessed after 25 or 50 min of water consumption [62]. Increasing water intake of low-consumers (<1.2 L/day) decreased confusion/bewilderment scores and fatigue/inertia scores while decreasing water intake of high-consumers (>2 L/day) decreased contentedness, calmness, positive emotions, and vigor/activity scores without affecting sleepiness [49]. Finally, fluid deprivation for 24 h did not affect sleepiness [54].

In general, our assessment is consistent with the conclusions from the aforementioned reviews, whereby hypohydration and/or thirst is consistently associated with increased negative emotions. The effect of hypohydration on attention and memory seem to suggest that >1% body mass loss is associated with deterioration in attention and memory, although this may be subdomain- and/or sex-dependent. Fatigue/tiredness appears to be rated higher with dehydration and is unlikely to be affected by acute water consumption. Data on other domains of cognition and sleepiness are sparse and require further research.

3.2.2. Cognition and Mood in Children

Our search identified nine studies, which are summarized in Table 2. Similar to data for adults, results from studies on hydration and cognition and mood in children are mixed. Studies in children have reported improvements in visual attention [38,41,44,45,54], but not sustained attention [46] following acute water consumption. The effect of acute effects of hydration on memory is dependent on the type of memory assessed, whereby some studies reported improvements in immediate memory [46] and others reporting no effects on verbal memory [38], visual memory [44], and story memory [45]. For the aforementioned acute studies, although a majority of studies did not assess baseline hydration status, it is likely that the children were mildly hypohydrated prior to acute water intake. In adolescents (mean age of 16.8 y), dehydration induced by thermal exercise (mean body mass loss of 1.7%) did not affect executive function, although brain imaging demonstrated increased fronto-parietal brain activation during the cognition task, suggesting a need for greater mental effort when dehydrated [43].

For longer-term water consumption (i.e., one whole day), results were mixed. Short-term memory assessed by auditory number span improved with additional water consumption (average 624 mL over a school day) in one study [42], but was not replicated in another study using digit recall [39], although exact amount of water consumed was not reported in the latter study. Other cognition domains including visual attention, selective attention, visual memory, visuomotor skills, perceptual speed, and verbal reasoning were unaffected by additional water consumption throughout the day [42,39].

Data on mood in relation to hydration status is also limited in children. Mood assessed using the POMS questionnaire did not change following additional water consumption for one day [42] while subjective ratings on happiness were not significantly affected by acute water consumption [45].

Overall, acute consumption of fluid by children appears to improve visual attention, with data on sustained attention being mixed. The effect of acute and chronic fluid consumption on memory is sparse and inconsistent. Finally, the limited data available on hydration and children suggest that hydration does not affect mood.

3.2.3. Headache

Hypohydration is thought to be a cause of headache, and increased fluid consumption has been suggested to relieve some forms of headache. However, evidence on hydration and headache is limited. The two intervention trials that were conducted by the same group were identified, with the earlier report describing a pilot assessment for the latter report, which was a larger trial [65,66]. Results from the two-week pilot study on migraines in adults were promising, with observed reductions in total hours of headache and mean headache intensity in the subjects who drank additional 1.5 L/day water compared to a control group who were given a placebo tablet [66]. In the follow-up study, a larger intervention trial, drinking more water (additional 1.5 L/day) resulted in a statistically significant improvement of 4.5 points on the Migraine-Specific Quality of Life scale [65]. Almost half (47%) of the subjects in the intervention (water) group self-reported improvement against 25% of the subjects in the control group [65]. However, objective measures such as headache days, hours of headache, and medication use were not different between subjects who consumed additional water and controls [65]. The authors noted several limitations in the larger intervention study, including partial unblinding of subjects, small sample size, and a large attrition rate [65].

3.3. Renal Function

A common disorder discussed in reviews found on hydration and kidney/renal function is kidney stones, which affects up to 12% of the world population [67]. Observational studies report an association between low total fluid intake and high risk for kidney stones, leading to guidelines recommending increasing fluid intake as a preventative strategy against kidney stones [68,69]. Although our search strategy was not designed to target any specific renal condition, only studies on kidney stones remained after filtering out diseases/disorders that are not relevant to the general population (e.g., chronic kidney disease). We identified one meta-analysis on high fluid intake and kidney stones which reported a significant association between high fluid intake and a lower risk of incident kidney stones, with 0.40-fold (RCTs) and 0.59-fold (observational studies) decreased risk [27]. In addition, high fluid intake reduced the risk of recurrent kidney stones (RR 0.40) [27]. With the exception of providing an explicit statement of questions being addressed and clarifying if a review protocol existed, the meta-analysis fulfilled all required PRISMA reporting items (Table 1). The meta-analysis fulfilled 10 out of the 16 required AMSTAR 2 items, but lacked clarity on study selection and completeness in assessment of included studies.

There have been very few intervention studies measuring the effect of hydration on kidney stones. We identified two relevant studies and these were already included in the aforementioned 2016 meta-analysis. In a 5-year randomized study, patients with idiopathic calcium stone disease had a 12% recurrence rate when encouraged to increase their fluid intake to achieve a urine output of 2 L/day, and a 27% recurrence rate if they were not given specific advice on urine output [70]. Another study investigated the effects of increased fluid intake (to achieve urine output of at least 2.5 L/day) following shock wave lithotripsy (SWL) treatment in stone patients. Among those who were stone free following SWL treatment, rate of recurrence was 8.3% for those with increased fluid intake, compared to 40% for those who were taking Verapamil, a calcium entry blocking agent, and 55% for those who were not provided any specific medication or dietary instructions [71]. Although not statistically significant, the rate of stone regrowth among those with residual fragments following SWL was lowest in subjects with increased fluid intake compared to those who received Verapamil (15.3% vs. 20%, respectively) [71]. Subjects who did not receive any intervention had a regrowth rate of 64% [71].

3.4. Gastrointestinal Function

Our search on hydration and gastrointestinal function resulted in one review that addressed the role of fluid intake in the prevention and treatment of functional intestinal constipation in children and adolescents [28] (Table 1). One review was found on the effect of beverage types on gastric emptying and subsequent nutrient absorption [72]; however, this is outside the scope of our review as it did not address hydration alone. Following screening, we found four intervention studies on constipation and one study that assessed the effect of dehydration on gastrointestinal function at rest in humans (Table 3). Our search strategy also resulted in a number of intervention studies that compared different types of beverages on exercise-induced gastrointestinal dysfunction and dehydration, and as noted in the methods, these were not considered within scope of the present review.

Table 3.

Intervention Studies on Hydration and Gastrointestinal Function 1.

The review on functional intestinal constipation in children and adolescents included 11 studies that either evaluated fluid intake as a risk factor for constipation or evaluated the role of fluid intake in the treatment of intestinal constipation in children or adolescents [28]. Authors reported the possibility of a causal association between lower fluid intake and constipation but noted that study outcomes were heterogeneous and thus, difficult to compare [28]. For the most part, studies that assessed fluid intake as a treatment of constipation showed no effects, although authors again noted the heterogeneity in methodologies of the studies [28]. Of the four intervention studies on constipation, two reported beneficial effects of increased fluid intake on stool measurements and the other two reported no effects (Table 3). The largest trial involved 117 adults with chronic functional constipation randomized to receive 25 g/day fiber alone (with ad libitum fluid intake) or 25 g/day fiber alone with 2 L/day water for 2 months [73]. The water supplemented group consumed more fluid (mean of 2.1 L/day vs. mean of 1.1 L/day) and had greater stool frequency and fewer use of laxatives compared to the ad libitum group [73]. In another study, healthy men were prescribed standardized nutritional and physical activity regimens and randomized to 0.5 L or 2.5 L of fluid per day for one week followed by a crossover after a two-week washout period [74]. During periods of fluid restriction, authors observed reduction in stool weight and frequency and increased tendency towards constipation [74]. When regular fluid consumption was resumed, bowel function returned to normal [74]. In contrast, the two other intervention studies in adults did not report changes in stool measurements following additional fluid intake. Consumption of additional 1 L/day for the first two days followed by 2 L/day for the next two days of either near isotonic fluid or hypotonic fluid (i.e., water) increased urinary output but did not affect stool weight in healthy adults [75]. Addition of 15 g/day wheat bran for 14 days slowed gastric emptying, shortened oroanal transit, and increased stool frequency and stool weight; however, the consumption of 600 mL fluid with the wheat bran did not affect these measurements when compared to consumption of wheat bran alone [76].

Finally, heat-induced dehydration of 3% body mass loss decreased gastric emptying compared to euhydration conditions, but did not affect orocecal transit time, intestinal permeability, and intestinal glucose absorption in healthy men (n = 10) [77].

3.5. Body Weight and Body Composition

Studies on beverage consumption and weight management have mainly focused on the replacement of caloric beverages with non-caloric or lower calorie beverages. A 2016 systematic review on water intake and body weight/weight management was identified [29], which provides a comprehensive listing of the human intervention studies published through 2014 that assessed water intake on energy intake, energy expenditure, body mass index (BMI), and weight change. The review included 134 total RCTs representing 440 different test conditions. Only a handful of these studies investigated the effects of water intake on body weight and body composition independent of changes in caloric intake and physical activity. Two were studies in adults [78,79] and two were in children [80,81]. Akers et al. [78] reported reductions in body fat, but not body weight or BMI, in overweight and obese adults who consumed ~3 times more water compared to a control group (average 1241 g/day vs. 451 g/day, respectively). In this study, energy intake of the water group was slightly greater than that of the control group, although these were not significantly different (average 1726 kcal/day vs. 1654 kcal/day).In another study, adults who were assigned a hypocaloric diet and 500 mL water prior to each daily meal lost more body weight and total fat mass compared to those on a hypocaloric diet alone [79]. Energy intake significantly decreased by the end of the 12-week intervention but was not different between water and control groups (average intake at 12 weeks: 1454 kcal/day vs. 1511 kcal/day, respectively) [79]. Additionally, ad libitum meal intake assessed at the end of the intervention was not different between groups, with or without 500 mL water pre-load [79]. In an 8-week intervention study, children (BMI percentile of ≥ 85%) who replaced caloric beverages with water and increased water consumption lost more body weight compared to children who only replaced caloric beverages with water [81]. Of note, at the end of the study, urine osmolality was below 500 mmol/kg in the group that increased water consumption, while urine osmolality stayed above 500 mmol/kg in the group that only replaced caloric beverages with water [81]. Increased water consumption (+1 glass/day) following a water intake promotion program for 1 year did not result in changes in BMI-z scores in students, although the percentage of students who were overweight was lower in the intervention group compared to the control group [80].

Our updated search resulted in 549 titles (Figure 1), and the majority of these were excluded because they investigated the effect of replacement of caloric beverages with non-caloric beverages, replacement of non-caloric beverages with water, or methodological considerations of hydration on BMI assessments. When compared with the 2016 systematic review [29], our search found four new publications; of which one [82] was a duplicate publication of a study that was already included in a previous systematic review [83]. The three new studies (Table 4) varied in design, with one being a study on hydration status and energy intake [84], one on water preloading and weight loss [85], and the other on increased water consumption and weight loss [86]. Of the new studies, one investigated the very short-term effect (i.e., 24 h) of euhydration vs. hypohydration on ad libitum breakfast energy intake in healthy men and observed no difference in energy intake between groups [84]. Another reported greater weight loss following water pre-loading (500 mL) before main meals for 12 weeks in obese adults (n = 84, [85]). Finally, increasing water consumption (mean increase of ~310 mL/day) did not affect BMI and other anthropometric measures in overweight and obese adolescents (n = 38) who were enrolled in a weight-loss program for 6 months [86]. The results of these new studies were mostly consistent with the general observations presented by the 2016 systematic review. The long-term study that reported weight loss instructed obese subjects to follow an energy-restricted diet and consume >1 L water/day, although the change in glucose and insulin is unknown [85]. In contrast, the authors of the long-term study that did not observe changes in body weight commented that subjects failed to increase water consumption, such that there were no differences in urine specific gravity between the water and control groups [86].

Table 4.

Intervention Studies on Hydration and Weight Management 1.

4. Discussion

Water is involved in virtually all bodily function. Thus, ensuring that the body has enough water to maintain proper function is important for health. According to the analysis of combined urine osmolality data from the NHANES 2009–2010 and 2011–2012 surveys, about 1/3 (32.6%) of adults (ages 18–64 years old) [87] and more than half (54.5%) of children and adolescents (ages 6–19 years old) [88] in the US are inadequately hydrated. Therefore, it is important to understand the effect of hydration on health in the general population. This review is a compilation of evidence on hydration and various health outcomes thought to have a beneficial effect among the general population, including skin health, gastrointestinal and renal function, cognition, mood, headache, and body weight and composition, with cognition being the most researched. Overall, there is a growing body of evidence supporting the importance of maintaining a normal state of hydration on various health aspects, although the strength and quality of the evidence vary within each health area (Table 5).

Table 5.

Summary of Literature Findings.

Evidence on hydration status and skin health is limited and no new studies published after a 2018 systematic review of the topic [24] were identified. Results from the handful of studies included in the review suggest that increasing water consumption may improve SC hydration. One of the most important functions of the skin is its ability to serve as an efficient barrier to molecular diffusion and the SC layer of the epidermis is the primary location of this barrier function. SC hydration is intimately related to the structure and function of the SC [89], thus, it is often an outcome in studies on skin health. The improvements in SC hydration following increased water consumption reported by existing intervention studies suggest better skin barrier function with increased oral hydration; however, these studies reported no changes in TEWL, which is another measure of skin barrier integrity. Therefore, the effectiveness of additional water consumption on skin barrier function is unclear. Furthermore, these studies failed to consistently assess other skin parameters such as those related to elasticity, firmness, roughness, surface texture, and pigmentation. Also, the applicability of the results of these studies is unclear; in most cases, subjects were already meeting the water intake recommendations and/or were required to consume water above the recommended intakes. Available studies were assessed to have low methodological quality and extremely high risk of bias by the authors of the systematic review [24].

Studies on hydration and neurological function focused on cognition, mood, and headache, with some also assessing sleep and fatigue. Studies on cognition investigated a variety of subdomains using different assessment tools, which makes comparisons across studies challenging. Evidence within each subdomain is sparse; thus, the specific influence of hydration on cognition is unclear. Reviewing the evidence in adults and children together, however, suggests that hypohydration negatively influences attention and results in the need for greater effort when performing attention-oriented tasks, which is ameliorated by rehydration. The effects of hypohydration and rehydration are less pronounced for memory and reaction time. Our observations are consistent with results from a recent meta-analysis published after our search date of April 2018 [90]. The meta-analysis authors reported that high-order cognitive processing (involving attention and executive function) and motor coordination appear more susceptible to impairment following dehydration compared to other domains involving lower order mental processing (e.g., simple reaction time) [90]. Additionally, across all cognitive domains and outcomes, studies eliciting a >2% body mass loss resulted in significantly greater cognitive impairments than studies eliciting ≤ 2% body mass loss [90]. The relationship between hydration and mood appears to be more consistent in adults, with hypohydration associated with increased negative emotions such as anger, hostility, confusion, depression, and tension as well as fatigue and tiredness. In children, however, data on hydration and mood is very limited and unclear. Overall, hydration does affect cognition and mood, although the specifics of the relationships are unclear. Finally, the evidence is too limited to determine if hydration affects headache. Two studies reported that increases in water consumption did not improve objective measures of headache, including number of days with headaches, hours of headache, and medication use, although subjective measures, such as headache intensity rating and quality of life questionnaire scores, were improved.

The renal system plays an important role in maintaining water and salt homeostasis; thus hydration is often associated with renal function and health, particularly the risk of kidney stones. The pathophysiology of kidney stone development is not yet fully understood, although a likely cause is an acquired or congenital anatomical structural abnormality [91]. Kidney stones form when the concentration of stone-forming salts exceeds their saturation point in the urine [91]. Thus, it is commonly suggested that dehydration may lead to the development of kidney stones, and that consumption of fluid may decrease the risk of kidney stones. Findings consistently suggest that increased fluid intake resulting in increased urine output is related to reduced risk of kidney stone development or recurrence rate, although data are limited. For example, a recent meta-analysis that included two intervention and seven observational studies reported a significant association between high fluid intake and a lower risk of incident kidney stones [27]. The observational studies were of moderately high quality, however, the two intervention studies were of low quality [27]. Further, limitations in the current literature include differences in diagnostic methodology of kidney stones, as well as inconsistent definitions of stone occurrence and recurrence. Overall, kidney stone occurrence is likely dependent on hydration and additional intervention studies are needed to confirm this relationship.

Another important kidney function is the removal of a wide variety of potentially toxic xenobiotics, xenobiotic metabolites, as well as metabolic wastes from the body. Elimination of unwanted substances via the urine depends on several variables that are, in turn, highly dependent on hydration status. These include renal blood flow, the glomerular filtration rate, the capacity of the kidney to reabsorb or to secrete drug molecules across the tubular epithelium, urine flow, and urine pH [92]. Because of this, detoxification is commonly associated with fluid intake or hydration. In conventional medicine, toxins generally refer to drugs and alcohol, and ‘detox’ is the process of weaning patients off these addictive substances. Commercially (and among laypersons), “detox” often refers to the removal of substances that may include, but are not limited to pollutants, synthetic chemicals, heavy metals, and other potentially harmful products of modern life. Little, if any, evidence exists to support the use of commercial detox diets for toxin elimination [93].

Increased fiber and fluid consumption are typical dietary-based therapeutic approaches to functional constipation [94,95]. Results from epidemiological studies suggest a possible relationship between low fluid intake and intestinal constipation occurrence. However, clinical trials currently do not support the use of increased fluid intake in the treatment of functional constipation. A comprehensive review of hydration and constipation in children and adolescents reported that fluid intake was ineffective in treating constipation [28]. Of the intervention studies we identified, one was in adults with chronic constipation and the rest were in healthy adults. Increased water intake by adults with chronic constipation increased stool frequency and decreased laxative use, while additional water consumption by healthy adults did not affect stool outcomes, suggesting a possible effect of increased hydration and improvements in stool output only in those with existing constipation. Further studies are necessary to better understand the role of water and fluids in the etiology and treatment of intestinal constipation, and study designs should include standardized evaluation tools for constipation outcomes (e.g., stool consistency, frequency of bowel movement), control for confounding dietary and lifestyle factors (e.g., fiber intake, physical activity), and measurements of hydration status and fluid intake. Additionally, published studies investigating the effect of hydration on normal functions of the gastrointestinal tract in healthy humans are lacking. Studies on dehydration and gastrointestinal function have mainly focused on exercise or gastrointestinal disorders [77].

A majority of the studies on fluid intake and weight management focused on the replacement of caloric beverages with non-caloric beverages and this has consistently resulted in lower overall energy intake [29]. However, consumption of hypoosmotic solutions such as water may contribute to weight loss by increasing lipolysis, fat oxidation, and thermogenesis, independent of changes in caloric intake as suggested by animal studies [96]. Only a handful of studies have investigated the influence of fluid intake (specifically water intake) on changes in body weight and/or body composition, independent of changes in energy intake. Existing data in adults suggest that increased water intake contributes to reductions in body fat and/or weight loss in obese adults, with or without a hypocaloric diet. Data in children/adolescents are less clear, possibly due to the smaller difference in water consumption between control and intervention groups in these studies (~350 mL/day) compared to the studies in adults (>800 mL/day). Adherence to the hydration regimen is a common problem reported by intervention studies in children/adolescents. Additionally, background diets were not collected in these studies, with the authors citing limitations in collecting dietary records in children/adolescent as the reason. While existing evidence show promising results for hydration and weight management, more studies are needed to confirm and clarify the effect of water intake on body weight and composition in adults and children.

Overall, assessing the totality of the hydration evidence is challenging due to the diversity in population, interventions, and trial designs across the studies. While many studies were conducted using a dehydration-rehydration design, variations in dehydration protocols (e.g., passive or active dehydration, type of exercise and environment, length of passive dehydration, extent of dehydration) and rehydration strategies (e.g., amount and timing of fluid intake) were observed. Outcome assessment tools, particularly for cognition, varied greatly, making it difficult to obtain enough evidence to clearly determine the impact of hydration on specific cognition subdomains. One of the biggest challenges with hydration studies is achieving consistency in the way hydration, dehydration, and overhydration is defined and measured. This is further complicated by the current lack of widely accepted screening tools or gold standard tests that allow for easily performable and replicable measurements of fluid balance and fluid intake. Another challenge for hydration studies is the difficulty in blinding subjects to the intervention. Possible solutions include providing intravenous fluid instead of oral hydration, although this bypasses the body’s normal indicators of hydration status such as thirst and oropharyngeal reflexes, which may play a role in the effect of hydration on various outcomes. Therefore, it is even more important that future studies ensure blinded assessment of study outcomes.

An important gap in knowledge is the effect of small variations in hydration on health in the general population. The point at which dehydration (or rehydration) affects health indicators is not easily determined from the current body of literature. Understanding the effect of different levels of mild dehydration on health is important as a substantial number of the general US population, especially older adults, drink less than the Adequate Intake for water that was established by the IOM [87,88,97]. Another gap in knowledge is the influence of sex on the effects of hydration on health as only a minority of the studies found considered both males and females. Additionally, there is also a need to consider the stage of the menstrual cycle as female sex hormones (estrogen and progesterone) are known to influence body fluid regulation [98,99]. These are particularly important considerations for studies in which outcomes are also known to be influenced by hormones, such as cognition and mood. Finally, understanding how hydration affects health in older adults and children is also important. Many of the health outcomes discussed in this review such as weight loss, cognition, kidney stones, and constipation are highly relevant to older adults and children. Older adults are susceptible to dehydration [100] due to various physiological (blunted thirst response, decline in kidney function) and environmental (limited mobility, inadequate assistance in nursing homes or hospital stays) factors [14], which can then lead to increased morbidity [101,102]. Meanwhile, as reviewed here, dehydration in children may have a negative impact on cognitive development and school performance in addition to physical health.

The goal of this narrative review was to present the state of the science on hydration that is relevant to the general population. Although a systematic approach was used to identify the literature and the search was broad, the publications included may not represent all available studies and reviews on the effects of hydration and specific health areas, given only one database was used, non-English publications were excluded, and the possibility that the search terms did not reflect all relevant conditions. Finally, the studies were quite heterogeneous, making broad conclusions difficult.

5. Conclusions

Water is the largest single constituent of the human body, making up approximately 60% and 75% of the adult and child human bodies, respectively. Body water deficits challenge the ability to maintain homeostasis during perturbations (e.g., sickness, physical exercise, and environmental exposure) and can affect function and health. As shown in this review, hydration status is an important aspect for health maintenance; however, evidence on the specific effects of hydration relevant to the generally healthy population is scarce and mostly inconsistent. The relationships between hydration and cognition, kidney stone risk, and weight management in generally healthy individuals are perhaps the most promising, although additional research is needed to confirm and clarify existing findings. Additional high-quality studies are needed to fill current gaps in knowledge and enable us to understand the specifics on the role of hydration in promoting health, as well as to help inform public health recommendations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.L., T.B.; systematic search, screening, and data extraction, D.L., E.M.; original draft preparation, D.L., E.M.; review and editing, D.L., E.M., L.B.B., P.L.B., T.B., L.L.S.; approval of final version, D.L., E.M., L.B.B., P.L.B., T.B., L.L.S.

Funding

Eunice Mah and DeAnn Liska received funding from PepsiCo to conduct the literature review.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Deena Wang for assistance with the literature search and screening.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Tristin Brisbois, Pamela L. Barrios, and Lindsay B. Baker are employed by PepsiCo, Inc. The views expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of PepsiCo, Inc.

References

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) Panel on Dietetic Products Nutrition and Allergies (NDA). Scientific Opinion on Dietary Reference Values for water. EFSA J. 2010, 8, 1459–1507. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine (IOM) Panel on Dietary Reference Intakes for Electrolytes and Water. Dietary Reference Intakes for Water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate; National Academy of Sciences Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005.

- Cheuvront, S.N.; Kenefick, R.W. Dehydration: Physiology, assessment, and performance effects. Compr. Physiol. 2014, 4, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thomas, D.R.; Cote, T.R.; Lawhorne, L.; Levenson, S.A.; Rubenstein, L.Z.; Smith, D.A.; Stefanacci, R.G.; Tangalos, E.G.; Morley, J.E.; Dehydration Council. Understanding clinical dehydration and its treatment. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2008, 9, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawka, M.N.; Cheuvront, S.N.; Kenefick, R.W. Hypohydration and Human Performance: Impact of Environment and Physiological Mechanisms. Sports Med. 2015, 45 (Suppl. 1), S51–S60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bak, A.; Tsiami, A.; Greene, C. Methods of Assessment of Hydration Status and their Usefulness in Detecting Dehydration in the Elderly. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. 2017, 5, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheuvront, S.N.; Ely, B.R.; Kenefick, R.W.; Sawka, M.N. Biological variation and diagnostic accuracy of dehydration assessment markers. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheuvront, S.N.; Kenefick, R.W.; Zambraski, E.J. Spot Urine Concentrations Should Not be Used for Hydration Assessment: A Methodology Review. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2015, 25, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, L.E. Hydration assessment techniques. Nutr. Rev. 2005, 63, S40–S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, L.E. Assessing hydration status: The elusive gold standard. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2007, 26, 575S–584S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheuvront, S.N. Urinalysis for hydration assessment: An age-old problem. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortes, M.B.; Owen, J.A.; Raymond-Barker, P.; Bishop, C.; Elghenzai, S.; Oliver, S.J.; Walsh, N.P. Is this elderly patient dehydrated? Diagnostic accuracy of hydration assessment using physical signs, urine, and saliva markers. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2015, 16, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heavens, K.R.; Charkoudian, N.; O’Brien, C.; Kenefick, R.W.; Cheuvront, S.N. Noninvasive assessment of extracellular and intracellular dehydration in healthy humans using the resistance-reactance-score graph method. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 724–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, L.; Bunn, D.; Jimoh, F.O.; Fairweather-Tait, S.J. Water-loss dehydration and aging. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2014, 136–137, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, L.; Bunn, D.K.; Abdelhamid, A.; Gillings, R.; Jennings, A.; Maas, K.; Millar, S.; Twomlow, E.; Hunter, P.R.; Shepstone, L.; et al. Water-loss (intracellular) dehydration assessed using urinary tests: How well do they work? Diagnostic accuracy in older people. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volkert, D.; Beck, A.M.; Cederholm, T.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.; Goisser, S.; Hooper, L.; Kiesswetter, E.; Maggio, M.; Raynaud-Simon, A.; Sieber, C.C.; et al. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition and hydration in geriatrics. Clin. Nutr. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, J.; Guelinckx, I.; Livingstone, B.; Potischman, N.; Nelson, M.; Foster, E.; Holmes, B. Challenges in the assessment of total fluid intake in children and adolescents: A discussion paper. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandy, J. Water intake: Validity of population assessment and recommendations. Eur. J. Nutr. 2015, 54 (Suppl. 2), 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sharkawy, A.M.; Sahota, O.; Lobo, D.N. Acute and chronic effects of hydration status on health. Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73 (Suppl. 2), 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenefick, R.W.; Cheuvront, S.N. Hydration for recreational sport and physical activity. Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70 (Suppl. 2), S137–S142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manz, F. Hydration and disease. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2013, 26, 535S–541S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maughan, R.J.; Shirreffs, S.M. Dehydration and rehydration in competitive sport. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2010, 20 (Suppl. 3), 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maughan, R.J.; Shirreffs, S.M. Development of hydration strategies to optimize performance for athletes in high-intensity sports and in sports with repeated intense efforts. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2010, 20 (Suppl. 2), 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akdeniz, M.; Tomova-Simitchieva, T.; Dobos, G.; Blume-Peytavi, U.; Kottner, J. Does dietary fluid intake affect skin hydration in healthy humans? A systematic literature review. Skin Res. Technol. 2018, 24, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benton, D.; Young, H.A. Do small differences in hydration status affect mood and mental performance? Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73 (Suppl. 2), 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masento, N.A.; Golightly, M.; Field, D.T.; Butler, L.T.; van Reekum, C.M. Effects of hydration status on cognitive performance and mood. Br. J. Nutr. 2014, 111, 1841–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheungpasitporn, W.; Rossetti, S.; Friend, K.; Erickson, S.B.; Lieske, J.C. Treatment effect, adherence, and safety of high fluid intake for the prevention of incident and recurrent kidney stones: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Nephrol. 2016, 29, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boilesen, S.N.; Tahan, S.; Dias, F.C.; Melli, L.; de Morais, M.B. Water and fluid intake in the prevention and treatment of functional constipation in children and adolescents: Is there evidence? J. Pediatr. 2017, 93, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stookey, J.J. Negative, Null and Beneficial Effects of Drinking Water on Energy Intake, Energy Expenditure, Fat Oxidation and Weight Change in Randomized Trials: A Qualitative Review. Nutrients 2016, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabrowska, A.K.; Spano, F.; Derler, S.; Adlhart, C.; Spencer, N.D.; Rossi, R.M. The relationship between skin function, barrier properties, and body-dependent factors. Skin Res. Technol. 2018, 24, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolarsick, P.A.J.; Kolarsick, M.A.; Goodwin, C. Anatomy and Physiology of the Skin. J. Dermatol. Nurse Assoc. 2011, 3, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittie, L.; Fisher, G.J. Natural and sun-induced aging of human skin. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2015, 5, a015370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palma, L.; Marques, L.T.; Bujan, J.; Rodrigues, L.M. Dietary water affects human skin hydration and biomechanics. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 8, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Palma, M.L.; Monteiro, C.; Bujan, L.T.M.J.; Rodrigues, L.M. Relationship between the dietary intake of water and skin hydration. Biomed. Biopharm. Res. 2012, 9, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, M.L.; Tavares, L.; Fluhr, J.W.; Bujan, M.J.; Rodrigues, L.M. Positive impact of dietary water on in vivo epidermal water physiology. Skin Res. Technol. 2015, 21, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mac-Mary, S.; Creidi, P.; Marsaut, D.; Courderot-Masuyer, C.; Cochet, V.; Gharbi, T.; Guidicelli-Arranz, D.; Tondu, F.; Humbert, P. Assessment of effects of an additional dietary natural mineral water uptake on skin hydration in healthy subjects by dynamic barrier function measurements and clinic scoring. Skin Res. Technol. 2006, 12, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.; Krueger, N.; Davids, M.; Kraus, D.; Kerscher, M. Effect of fluid intake on skin physiology: Distinct differences between drinking mineral water and tap water. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2007, 29, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmonds, C.J.; Crosbie, L.; Fatima, F.; Hussain, M.; Jacob, N.; Gardner, M. Dose-response effects of water supplementation on cognitive performance and mood in children and adults. Appetite 2017, 108, 464–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trinies, V.; Chard, A.N.; Mateo, T.; Freeman, M.C. Effects of Water Provision and Hydration on Cognitive Function among Primary-School Pupils in Zambia: A Randomized Trial. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perry, C.S., 3rd; Rapinett, G.; Glaser, N.S.; Ghetti, S. Hydration status moderates the effects of drinking water on children’s cognitive performance. Appetite 2015, 95, 520–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, P.; Edmonds, C.J. Water supplementation improves visual attention and fine motor skills in schoolchildren. Educ. Health 2012, 30, 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Fadda, R.; Rapinett, G.; Grathwohl, D.; Parisi, M.; Fanari, R.; Calo, C.M.; Schmitt, J. Effects of drinking supplementary water at school on cognitive performance in children. Appetite 2012, 59, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempton, M.J.; Ettinger, U.; Foster, R.; Williams, S.C.; Calvert, G.A.; Hampshire, A.; Zelaya, F.O.; O’Gorman, R.L.; McMorris, T.; Owen, A.M.; et al. Dehydration affects brain structure and function in healthy adolescents. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2011, 32, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmonds, C.J.; Jeffes, B. Does having a drink help you think? 6–7-Year-old children show improvements in cognitive performance from baseline to test after having a drink of water. Appetite 2009, 53, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmonds, C.J.; Burford, D. Should children drink more water?: The effects of drinking water on cognition in children. Appetite 2009, 52, 776–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benton, D.; Burgess, N. The effect of the consumption of water on the memory and attention of children. Appetite 2009, 53, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stachenfeld, N.S.; Leone, C.A.; Mitchell, E.S.; Freese, E.; Harkness, L. Water intake reverses dehydration associated impaired executive function in healthy young women. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 185, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benton, D.; Jenkins, K.T.; Watkins, H.T.; Young, H.A. Minor degree of hypohydration adversely influences cognition: A mediator analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pross, N.; Demazieres, A.; Girard, N.; Barnouin, R.; Metzger, D.; Klein, A.; Perrier, E.; Guelinckx, I. Effects of changes in water intake on mood of high and low drinkers. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, C.J.; Crombie, R.; Ballieux, H.; Gardner, M.R.; Dawkins, L. Water consumption, not expectancies about water consumption, affects cognitive performance in adults. Appetite 2013, 60, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindseth, P.D.; Lindseth, G.N.; Petros, T.V.; Jensen, W.C.; Caspers, J. Effects of hydration on cognitive function of pilots. Mil. Med. 2013, 178, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edmonds, C.J.; Crombie, R.; Gardner, M.R. Subjective thirst moderates changes in speed of responding associated with water consumption. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ely, B.R.; Sollanek, K.J.; Cheuvront, S.N.; Lieberman, H.R.; Kenefick, R.W. Hypohydration and acute thermal stress affect mood state but not cognition or dynamic postural balance. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2013, 113, 1027–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pross, N.; Demazieres, A.; Girard, N.; Barnouin, R.; Santoro, F.; Chevillotte, E.; Klein, A.; Le Bellego, L. Influence of progressive fluid restriction on mood and physiological markers of dehydration in women. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 109, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, L.E.; Ganio, M.S.; Casa, D.J.; Lee, E.C.; McDermott, B.P.; Klau, J.F.; Jimenez, L.; Le Bellego, L.; Chevillotte, E.; Lieberman, H.R. Mild dehydration affects mood in healthy young women. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganio, M.S.; Armstrong, L.E.; Casa, D.J.; McDermott, B.P.; Lee, E.C.; Yamamoto, L.M.; Marzano, S.; Lopez, R.M.; Jimenez, L.; Le Bellego, L.; et al. Mild dehydration impairs cognitive performance and mood of men. Br. J. Nutr. 2011, 106, 1535–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kempton, M.J.; Ettinger, U.; Schmechtig, A.; Winter, E.M.; Smith, L.; McMorris, T.; Wilkinson, I.D.; Williams, S.C.; Smith, M.S. Effects of acute dehydration on brain morphology in healthy humans. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2009, 30, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petri, N.M.; Dropulic, N.; Kardum, G. Effects of voluntary fluid intake deprivation on mental and psychomotor performance. Croat. Med. J. 2006, 47, 855–861. [Google Scholar]

- Szinnai, G.; Schachinger, H.; Arnaud, M.J.; Linder, L.; Keller, U. Effect of water deprivation on cognitive-motor performance in healthy men and women. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2005, 289, R275–R280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirreffs, S.M.; Merson, S.J.; Fraser, S.M.; Archer, D.T. The effects of fluid restriction on hydration status and subjective feelings in man. Br. J. Nutr. 2004, 91, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neave, N.; Scholey, A.B.; Emmett, J.R.; Moss, M.; Kennedy, D.O.; Wesnes, K.A. Water ingestion improves subjective alertness, but has no effect on cognitive performance in dehydrated healthy young volunteers. Appetite 2001, 37, 255–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, P.J.; Kainth, A.; Smit, H.J. A drink of water can improve or impair mental performance depending on small differences in thirst. Appetite 2001, 36, 57–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopinathan, P.M.; Pichan, G.; Sharma, V.M. Role of dehydration in heat stress-induced variations in mental performance. Arch. Environ. Health 1988, 43, 15–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, V.M.; Sridharan, K.; Pichan, G.; Panwar, M.R. Influence of heat-stress induced dehydration on mental functions. Ergonomics 1986, 29, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spigt, M.; Weerkamp, N.; Troost, J.; van Schayck, C.P.; Knottnerus, J.A. A randomized trial on the effects of regular water intake in patients with recurrent headaches. Fam. Pract. 2012, 29, 370–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spigt, M.G.; Kuijper, E.C.; Schayck, C.P.; Troost, J.; Knipschild, P.G.; Linssen, V.M.; Knottnerus, J.A. Increasing the daily water intake for the prophylactic treatment of headache: A pilot trial. Eur. J. Neurol. 2005, 12, 715–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alelign, T.; Petros, B. Kidney Stone Disease: An Update on Current Concepts. Adv. Urol. 2018, 2018, 3068365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion, M.; Ankawi, G.; Chew, B.; Paterson, R.; Sultan, N.; Hoddinott, P.; Razvi, H. CUA guideline on the evaluation and medical management of the kidney stone patient—2016 update. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2016, 10, E347–E358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearle, M.S.; Goldfarb, D.S.; Assimos, D.G.; Curhan, G.; Denu-Ciocca, C.J.; Matlaga, B.R.; Monga, M.; Penniston, K.L.; Preminger, G.M.; Turk, T.M.; et al. Medical management of kidney stones: AUA guideline. J. Urol. 2014, 192, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghi, L.; Meschi, T.; Amato, F.; Briganti, A.; Novarini, A.; Giannini, A. Urinary volume, water and recurrences in idiopathic calcium nephrolithiasis: A 5-year randomized prospective study. J. Urol. 1996, 155, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarica, K.; Inal, Y.; Erturhan, S.; Yagci, F. The effect of calcium channel blockers on stone regrowth and recurrence after shock wave lithotripsy. Urol. Res. 2006, 34, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiper, J.B. Fate of ingested fluids: Factors affecting gastric emptying and intestinal absorption of beverages in humans. Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73 (Suppl. 2), 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anti, M.; Pignataro, G.; Armuzzi, A.; Valenti, A.; Iascone, E.; Marmo, R.; Lamazza, A.; Pretaroli, A.R.; Pace, V.; Leo, P.; et al. Water supplementation enhances the effect of high-fiber diet on stool frequency and laxative consumption in adult patients with functional constipation. Hepatogastroenterology 1998, 45, 727–732. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Klauser, A.G.; Beck, A.; Schindlbeck, N.E.; Muller-Lissner, S.A. Low fluid intake lowers stool output in healthy male volunteers. Z. Gastroenterol. 1990, 28, 606–609. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chung, B.D.; Parekh, U.; Sellin, J.H. Effect of increased fluid intake on stool output in normal healthy volunteers. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 1999, 28, 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ziegenhagen, D.J.; Tewinkel, G.; Kruis, W.; Herrmann, F. Adding more fluid to wheat bran has no significant effects on intestinal functions of healthy subjects. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 1991, 13, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Nieuwenhoven, M.A.; Vriens, B.E.; Brummer, R.J.; Brouns, F. Effect of dehydration on gastrointestinal function at rest and during exercise in humans. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000, 83, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akers, J.D.; Cornett, R.A.; Savla, J.S.; Davy, K.P.; Davy, B.M. Daily self-monitoring of body weight, step count, fruit/vegetable intake, and water consumption: A feasible and effective long-term weight loss maintenance approach. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 685–692.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, E.A.; Dengo, A.L.; Comber, D.L.; Flack, K.D.; Savla, J.; Davy, K.P.; Davy, B.M. Water consumption increases weight loss during a hypocaloric diet intervention in middle-aged and older adults. Obesity 2010, 18, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muckelbauer, R.; Libuda, L.; Clausen, K.; Toschke, A.M.; Reinehr, T.; Kersting, M. Promotion and provision of drinking water in schools for overweight prevention: Randomized, controlled cluster trial. Pediatrics 2009, 123, e661–e667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stookey, J.D.; Del Toro, R.; Hamer, J.; Medina, A.; Higa, A.; Ng, V.; TinajeroDeck, L.; Juarez, L. Qualitative and/or quantitative drinking water recommendations for pediatric obesity treatment. J. Obes. Weight Loss Ther. 2014, 4, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Cordero, S.; Popkin, B.M. Impact of a Water Intervention on Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Intake Substitution by Water: A Clinical Trial in Overweight and Obese Mexican Women. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2015, 66 (Suppl. 3), 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Cordero, S.; Barquera, S.; Rodriguez-Ramirez, S.; Villanueva-Borbolla, M.A.; Gonzalez de Cossio, T.; Dommarco, J.R.; Popkin, B. Substituting water for sugar-sweetened beverages reduces circulating triglycerides and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in obese but not in overweight Mexican women in a randomized controlled trial. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 1742–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corney, R.A.; Horina, A.; Sunderland, C.; James, L.J. Effect of hydration status and fluid availability on ad-libitum energy intake of a semi-solid breakfast. Appetite 2015, 91, 399–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parretti, H.M.; Aveyard, P.; Blannin, A.; Clifford, S.J.; Coleman, S.J.; Roalfe, A.; Daley, A.J. Efficacy of water preloading before main meals as a strategy for weight loss in primary care patients with obesity: RCT. Obesity 2015, 23, 1785–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, J.M.W.; Ebbeling, C.B.; Robinson, L.; Feldman, H.A.; Ludwig, D.S. Effects of Advice to Drink 8 Cups of Water per Day in Adolescents With Overweight or Obesity: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, e170012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, T.; Ravi, N.; Plegue, M.A.; Sonneville, K.R.; Davis, M.M. Inadequate Hydration, BMI, and Obesity Among US Adults: NHANES 2009–2012. Ann. Fam. Med. 2016, 14, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenney, E.L.; Long, M.W.; Cradock, A.L.; Gortmaker, S.L. Prevalence of Inadequate Hydration among US Children and Disparities by Gender and Race/Ethnicity: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2009–2012. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, e113–e118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, C.L.; Topgaard, D.; Kocherbitov, V.; Sousa, J.J.; Pais, A.A.; Sparr, E. Stratum corneum hydration: Phase transformations and mobility in stratum corneum, extracted lipids and isolated corneocytes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1768, 2647–2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittbrodt, M.T.; Millard-Stafford, M. Dehydration Impairs Cognitive Performance: A Meta-analysis. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2018, 50, 2360–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, P.; Noble, H.; Al-Modhefer, A.K.; Walsh, I. Kidney stones: Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Br. J. Nurs. 2016, 25, 1112–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masereeuw, R.; Russel, F.G. Mechanisms and clinical implications of renal drug excretion. Drug Metab. Rev. 2001, 33, 299–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.V.; Kiat, H. Detox diets for toxin elimination and weight management: A critical review of the evidence. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 28, 675–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, L. Constipation Management in Pediatric Primary Care. Pediatr. Ann. 2018, 47, e180–e184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Rao, S. Constipation: Pathophysiology and Current Therapeutic Approaches. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2017, 239, 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, S.N. Increased Hydration Can Be Associated with Weight Loss. Front. Nutr. 2016, 3, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drewnowski, A.; Rehm, C.D.; Constant, F. Water and beverage consumption among adults in the United States: Cross-sectional study using data from NHANES 2005-2010. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stachenfeld, N.S. Sex hormone effects on body fluid regulation. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2008, 36, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stachenfeld, N.S. Hormonal changes during menopause and the impact on fluid regulation. Reprod. Sci. 2014, 21, 555–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stookey, J.D. High prevalence of plasma hypertonicity among community-dwelling older adults: Results from NHANES III. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2005, 105, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maughan, R.J. Hydration, morbidity, and mortality in vulnerable populations. Nutr. Rev. 2012, 70 (Suppl. 2), S152–S155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stotts, N.A.; Hopf, H.W. The link between tissue oxygen and hydration in nursing home residents with pressure ulcers: Preliminary data. J. Wound Ostomy Cont. Nurs. 2003, 30, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).