Abstract

Integrated care is regarded as a key for care delivery to persons with chronic long-term conditions such as Parkinson’s disease. For persons with Parkinson’s disease, obtaining self-management support is a top priority in the context of integrated care. Self-management is regarded as a crucial competence in chronic diseases since the affected persons and their caregivers inevitably take up the main responsibility when it comes to day-to-day management. Formal self-management education programs with the focus on behavioral skills relevant to the induction and maintenance of behavioral change have been implemented as a standard in many chronic long-term conditions. However, besides the example of the Swedish National Parkinson School, the offers for persons with Parkinson’s disease remain fragmented and limited in availability. Today, no such program is implemented as a nationwide standard in Germany. This paper provides (1) a systematic review on structured self-management education programs specifically designed or adopted for persons with Parkinson’s disease, (2) presents the Swedish National Parkinson School as an example for a successfully implemented nationwide program and (3) presents a concept for the design, evaluation and long-term implementation of a future-orientated self-management education program for persons with Parkinson’s disease in Germany.

1. Introduction

1.1. Integrated Care Concepts and Self-Management

Integrated care concepts (ICCs) are a core strategy to meet the health care challenge of age-related chronic degenerative diseases like Parkinson’s disease (PD) []. Common definitions describe integrated care as a person-centered approach delivering comprehensive coordinated care involving a multi- or interdisciplinary team across settings and levels of care []. Persons with chronic conditions (PwCD) are inevitably involved in their own care: They “cannot not manage” their diseases []. No matter how comprehensive an ICC might be, health care professionals are only intermittently involved and cannot alleviate the majority of disease sequelae. PwCDs and their social surroundings are inevitably most important when it comes to day-to-day management []. Thus, PwCDs should be considered as members of their own interdisciplinary team of healthcare providers.

PD is a prime example of a disease that confronts affected persons with high and evolving challenges in taking up this decade-long task: persons with Parkinson’s disease (PwPDs) experience an increasingly complex disease burden with an array of motor and non-motor symptoms, require a multidimensional pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical treatment regimen and experience a varying therapeutic effectiveness along the disease course.

Self-management is defined as “tasks that individuals must undertake to live with one or more chronic conditions. These tasks include having the confidence to deal with (1) medical management, (2) role management and (3) emotional management of their conditions” []. A recent expert panel on ICCs for PwPDs recommended self-management support as one of 30 components []. In contrast, PwPDs even give self-management support a top priority when asked about their requirements for ICCs: in two independent studies on the needs of PwPDs in ICCs, self-management support evolved as the top requirement [,]. Since ICCs rely to a varying extent on a person’s capacity in self-management, measures to promote self-management should be an inherent part of ICCs []. Self-management support measures do not only respect the needs of PwPDs, but also professional health care providers—their capacities to the best care possible rely on a productive participation of PwPDs themselves.

1.2. Components of Self-Management and Conceptual Frameworks

Self-management stretches beyond medical management such as taking the prescribed medication and requires the ability to adopt one’s behavior to symptoms or disability and to cope productively with emotions like fear or anxiety. This means that self-management represents a complex cognitive-behavioral challenge, involving the constant adjustment of role-related behaviors and processing of disease-related emotions. Negative emotions such as anxiety are related to lower quality of life (QoL) and higher mortality in PD []; this underpins the importance emotional self-management for health-related outcomes in PD.

This explains why unidimensional education initiatives, e.g., solely promoting disease-related knowledge or focusing on isolated behaviors like compliance often failed to be effective []. Rather, education programs that incorporate the training of skills required to induce and maintain behavioral changes are required. Only then sustainable improvements in function, emotional state or health-related outcomes can be achieved []. A seminal program that puts the training of skills into focus needed for behavioral change is the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP). Skills trained through the program are: (1) problem solving, (2) decision making, (3) resource utilization, (4) forming of a patient/health care provider relationship and (5) taking action []. The effectiveness of this program has been illustrated in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) both when implemented as a generic program for persons with various diseases and in disease-specific adaptations [,,]. Improvements in a variety of outcomes could be achieved, such as health-promoting behaviors, function, cognitive symptom management or overall health status.

The program is based on a person-centered conceptual framework related to social cognitive theory []. The theory has been extensively validated and claims that for the induction and maintenance of behavioral change both the mastery of the named core skills is necessary, as well as the belief in one’s self-efficacy to perform a certain behavior successfully []. An important aspect of self-efficacy is that it can be task-specific and does not necessarily extend to other behaviors []. Besides promoting skills mastery in action planning, the following strategies promote behavioral skills and self-efficacy beliefs: symptom reinterpretation—forming of alternative explanations for symptoms to allow for new self-management behaviors; modeling—teaching material reflects the target population and their situation adequately; social persuasion—use of the social context to support health-promoting behaviors, e.g., by group interventions with peers [,]. Related to the skill of action planning is self-tailoring. Self-tailoring means the competence to adjust actions or recommended health-promoting behaviors to personal capacities, preferences and living conditions []. Self-efficacy-promoting interventions have been found to improve outcomes in several domains, such as HbA1c in diabetes mellitus, various self-management behaviors (e.g., stress coping, pain management, medication adherence), general health status or quality of life [,].

1.3. Implementation of Self-Management Programs

Even though self-management interventions have been shown to be effective in a variety of settings (e.g., rehabilitation, outpatient or community-based settings) and with varying delivery strategies (e.g., combination with other therapeutic interventions, such as physiotherapy) [], there is a strong rationale to devote a distinct structured program to self-management education (SME).

The CDSMP is a prime example of such a program, delivered to small groups of PwCDs and care givers in several modules over several weeks. The program can be provided by trained health care providers (train-the-trainer principle) and has been shown to be generalizable to different diseases and cultural settings [,]. Such structured group programs do not only reflect the importance of self-management but also facilitate the delivery of self-management support with a standard quality. Moreover, the modular group-based approach facilitates core objectives such as practical training in action planning, modeling or social persuasion due to the regular contact with other PwCDs.

In spite of PD being a prime example of a progressive long-term condition with high demands in self-management competence, access to structured SME programs for PwPDs has lacked behind other comparable diseases. The current work will provide (1) a systematic literature review about structured self-management programs for PwPDs, (2) report the successful nationwide implementation of the National Parkinson School (NPS) in Sweden and (3) present a concept for the design, evaluation and sustainable implementation of a possible future-orientated SME program for PwPDs in Germany.

2. Materials and Methods

Systematic Review

A systematic review was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) criteria with the objective to report content, format and outcome of different SME programs specifically designed or adopted for PwPDs []. Level of evidence of quantitative studies retrieved was assessed by American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine (AACPDM) criteria [].

Literature research was conducted between May-June 2020 using the databases PubMed and EBSCO (consisting of Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), American Psychological Association (APA) PsycArticles, APA PsycInfo, Table of Contents (TOC) Premier). No publication date restriction was applied. Search term was: (parkinson*) AND ((“patient education”) OR (“patient school”) OR (“self-management”) OR (“self management”) OR (“selfmanagement”)).

Eligibility criteria for the studies retrieved by the search terms were: (1) inclusion of elements/components specifically dedicated to training of principles/skills/beliefs needed for induction or maintenance of behavioral change (self-management approach); (2) Program either adopted of specifically designed for PwPDs. Exclusion criteria were: (1) posters, books; (2) unidimensional programs: no program elements identifiable specifically dedicated to principles/skills/beliefs needed for behavioral change next to other training elements (e.g., physiotherapy); (3) full text not accessible.

Included studies are presented in separate tables for quantitative and qualitative evaluation studies. Protocols for future planned studies to evaluate SME programs are given in another separate table. For the PRISMA flow diagram checklist, please refer to Figure S1 and Table S1 (Supplementary Materials).

3. Results

After removal of duplicates, 631 records were retrieved, of which 551 were excluded after screening of title and abstracts for in-/exclusion criteria. After full-text assessment of the remaining 62 articles, 23 fully met inclusion criteria and were integrated into this systematic review; 20 described the evaluation of self-management interventions at different stages of implementation, and 3 described evaluation protocols of planned studies on future programs. One additional study was included that was not retrieved by the search terms but that otherwise met all inclusion criteria [].

3.1. General Program Description

A total of 18 different programs were described in the 23 publications. All programs were organized in modular small group sessions (2–18 sessions) with peer PwPDs, 8 programs (35%) including caregivers [,,,,,,,]. An exception to modular small group sessions was a study that compared 12 weeks of small group sessions (EXCEED) with the same program studied independently at home after one introductory group session []. Sessions were scheduled once or twice a week, ranging from 45 to 150 min in duration. Two (11%) programs were restricted to the training of self-management behaviors and associated cognitive behavioral skills [], 9 programs (50%) combined self-management support with other therapeutic measures, such as physiotherapy (7, 39%) [,,,,,,], occupational therapy (4, 22%) [,,,], relaxation and body awareness techniques (7, 39%) [,,,,,,] or speech therapy (4, 22%) [,,,]. All programs were carried out by healthcare professionals, several (9, 50%) by a multiprofessional team of up to 8 different healthcare professions [,,,,,,,,]. Whether the executing staff received training in teaching self-management behaviors, related skills and beliefs, was indicated for 5 programs (28%) [,,,,]. 2 programs (11%) mentioned the inclusion of trained peer PwPDs into the program delivery teams [,]. Most programs did not target specific PD subpopulations, with the exception of the EXCEED program for PwPDs with unipolar major depression [], and with the exception of the Early Management Program (EMP), the Safe Mobility (SMP) and Falls Prevention Program (FPP), designed to address PwPDs in early, intermediate and advanced diseases stages with shifting focus on different self-management behaviors []. For two programs (11%) it was explicitly reported that they were adaptations of generic programs such as the most widely implemented CDSMP [,]. Other programs such as the Patient Education Program for PD (PEEP) do not explicitly refer to generic programs like the CDSMP, but still have substantial similarities in objectives, modular organization and program content and thus appear to be inspired by such disease-generic predecessors.

3.2. Program Delivery Setting and Organization

With the exception of two programs [,], all others were delivered in an ambulatory outpatient setting, owing to their modular organization and duration over several weeks. One of the exceptions was a protocol for a future program (ParkProTrain) on physical activities: The program is to start during an intensive multimodal inpatient therapeutic program, but then to be continued independently at home for nine months with online sessions provided via an app []. One other study compared program delivery in small groups with home-based self-study []. For 5 programs (28%), a professional teaching manual was reported [,,,,], for 4 (22%) teaching manuals and handouts to participants [,,,], and for 6 (33%) homework/home exercise programs in between single modules [,,,,,]. Only 2 programs (11%) explicitly report the integration of digital components [,]. As mentioned, one future program includes an app-based intervention at home []. Another program reports the provision of program-supporting information on a patient-orientated webpage [].

3.3. Evaluation and Outcomes Measures

Both qualitative (3, 13%) [,,] and (9, 39%) quantitative studies have been performed for evaluation of PD-related self-management programs [,,,,,,,,]. Additionally, 8 (35%) studies combined quantitative data collection with qualitative descriptive aspects for program evaluation [,,,,,,,].

Of the quantitative studies, 3 reached level I according to AACPDM study quality scoring [,,], 3 level II [,,], 4 level III [,,,], 6 level IV [,,,,,], and 1 level V []. Controlled trials (10, 43%) compared to standard care [,,,,,,,,,], or compared two defined interventions (1, 4%) []. One additional study (1, 4%) compared two intensity levels of a multimodal intervention (SME plus physical/speech training) with usual care []. Selection criteria mostly were liberal, including PwPDs in different disease stages and with varying disease-related complications. Due to the nature of the interventions, none of the studies was blinded. 6 studies (26%) employed a delayed-start design, meaning that persons randomized to the control group received the intervention with a time delay [,,,,,]. Some programs restricted inclusion to certain disease stages (e.g., Hoehn and Yahr 2–3, or <4, for details see Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3). As mentioned, one study evaluated disease-stage specific programs and another program targeted PwPDs with major depression, both accompanied by corresponding study inclusion criteria [,].

Table 1.

Quantitative evaluation studies.

Table 2.

Qualitative evaluation studies.

Table 3.

Evaluation concepts for future studies.

Evaluation timepoints were at baseline and immediately or with little delay after the last element of respective intervention, and in 6 (26%) at varying intervals (2–12 months) after the intervention ended to assess for sustained effects [,,,,,].

Reported primary or secondary outcomes and employed measurement instruments fell into all domains of health-related outcomes [], ranging from physiological/biological variables (e.g., neuroprotective markers, brain-derived growth factor (BDNF) [] or multimodal brain imaging [], over symptom status (e.g., Apathy Scale) [], functional status (e.g., Berg Balance Score (BBS) [], general health behaviors (e.g., Brief Cope Scale) [] to overall (e.g., Short Form 36 (SF-36)) [] or health-related quality of life (e.g., Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire-39 (PDQ-39)) [].

The 5 most often reported outcomes were: Health related and general quality of life (12 studies, 52%) [,,,,,,,,,,], followed by depression [,,,,,,,,,], and aspects of self-management or self-efficacy [,,,], diverse functional mobility measures [,,] and Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) [,,] (for all other outcomes, see Table 1 and Table 3).

Although all studies reported various baseline characteristics and other contextual variables (e.g., highest level of formal education or cognitive state), statements about possible predictors, mediators or confounders were reported in 4 studies only [,,,].

There was only one program (PEPP, “Person Education for PwPDs and their carers”) evaluated in transcultural multicenter studies in seven European countries []. One additional study in Canada compared two centers in their program performance [].

There were 3 qualitative studies, all with the purpose of formative evaluation [,,]. 8 of the quantitative summative evaluation studies included additional formative elements [,,,,,,,], in addition to one quantitative study with a formative focus []. Examples of reported formative outcomes are: group experience, comprehensiveness, perceived usefulness, satisfaction, content relevance; 2/3 future protocols plan to report formative outcomes [,], 2/3 in a mixed methods design with a combination of qualitative and quantitative study methods.

3.4. Efficacy and Effectiveness

Although only some of studies stated the primary outcome clearly or the study power (primary outcome: [,]; power: [,]; primary outcome and power: [,]), 11/15 (73%) reported an intended effect in any of the reported outcome variables [,,,,,,,,,,]. Beneficial effects on (health-related) quality of life were reported in 6/11 (55%) studies that included any measurement instrument for quality of life. In addition, beneficial effects on the following outcomes were reported (for PwPDs): Any part of the UPDRS (2 studies) [,], depression (2) [,], self-management scales (1) [], active problem-orientated coping (1) [], fatigue (1) [], diverse functional mobility measures (1) [], general psychosocial burden (1) []; (for caregivers): mood (3) [,,], burden (2) [,], relaxation techniques (1) []. 2/15 studies failed to report any effect on the respective outcome measures [,]. One had a small study group of 36 only [], one used a measurement instrument (SF-12) for quality of life [] that was not used in any other of the reported studies.

Although positive effects on any outcome measure could be found for up to 12 months post-intervention [], most studies report an effect attrition in the post-intervention observation period ranging from 3 to 12 months. One study with a combined exercise/self-management support intervention reported effects on physical outcomes to be more stable than on psychosocial outcomes [].

Given the fact that most studies were mono-central, small in study size and mostly carried out by the intervention teams themselves, they are not suited to assess effectiveness. However, the PEPP and its successors are those programmes in which the most independent evaluation studies were carried out, some of them by totally independent research teams in different countries [,], and one study explicitly targeted at assessing the reproducibility of effects after program transferal to clinical practice []. All these studies including the latter were able to reproduce some effect on the measured outcomes, so that this could be considered as evidence for general effectiveness of the PEPP and its off-springs.

3.5. Comparison to Other Systematic Reviews, Limitations

The search identified 5 other former systematic reviews on self-management interventions in PD (Table S2). One review was on general and disease-specific SME programs [], while others focused on specific self-management programs for anxiety [], falls [], physical exercises [] or occupational therapy-related interventions []. All reviews utilized the search terms “Parkinson’s” and “self-management” among others. From the 23 articles included in the current review, between 1 [,] and 6 [] were also included in one of the five other identified systematic reviews. The relatively small overlap can mostly be explained by different eligibility/exclusion criteria.

One study met all inclusion criteria, but was not identified by the initial search terms [] (Table 1). This study compared physiotherapy in a community-based setting with and without additional components for SME, whereas the absolute program intensity was kept stable in both arms. The study found an increased level of physical activity in the arm with SME, stable over two years. The study included several additional measures to increase adherence, such as a treatment contract, a personal logbook, feedback via sensors and a personalized webpage.

The finding of this additional study points to a potential limitation of the current systematic review. Due to the selected search terms sources could have been missed that use alternative terms for interventions targeting health-promoting behavioral modifications.

4. Swedish National Parkinson School (NPS)—Example of a Nationwide Implementation of a Self-Management Education Program for Persons with Parkinson’s Disease (PwPDs)

The Swedish National Parkinson School (NPS) has its origin in the “Person Education for PwPDs and their carers” (PEPP), developed by the European EduPark consortium in 2002 []. The Swedish NPS has been available and offered in clinical practice since 2014. In 2013 the PEPP was translated into Swedish and adapted to suit the Swedish healthcare services. The PEPP was chosen as a model for the NPS because it incorporated the ideas of a standardized and systematic self-management education that could be offered nationwide but still recognizing the major importance of an education that was person-centered and viewed patients and care partners as vital members active participants in their own care [,]. The PEPP had also been evaluated and found feasible and valuable for the participants and showed improvements in several outcomes for both PwPD and care partners []. Much of the content in the Swedish NPS s still similar to the original PEPP program but in the NPS there is an even greater emphasis on the importance of shared resources to handle life, and the Swedish NPS is provided entirely as a dyadic intervention. Development of the NPS was made in collaboration with representatives of healthcare professionals, PwPDs and their care partners and the pharmaceutical industry. The development of the NPS was undertaken as a project in clinical care and a detailed description of the translation and adaptation process is provided by Carlborg [,].

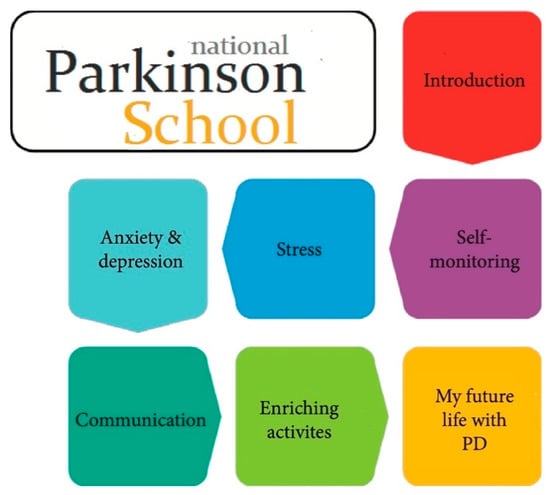

4.1. Program Description

The PEPP is focusing on strategies to manage the psychological and social impact of the disease and the main goal is to empower participants to better deal with the challenges brought on by PD, primarily focusing on the psychological and social impact of the disease []. This is also kept as the main goal of the Swedish NPS as it aims to provide PwPDs and their care partners with the knowledge and cognitive strategies needed to improve their ability to manage the impact of PD in everyday life. The focus of the NPS is on the importance of a constructive and positive mindset and the skills needed to continue a fulfilling and satisfying life even in the presence of PD. This is done by enhancing awareness of own thoughts, feelings and actions in relation to the impact of PD on their everyday lives. How PwPDs and their care partners choose to relate to disease and their changing life situation greatly affects their ability to maintain good satisfaction with life, despite the difficulties. The introduction of techniques for self-monitoring and self-awareness included in the NPS gives participants the tools needed to initiate adaptation and the changes needed to reduce the impact of disease. The Swedish NPS program includes seven topics inspired by the structure of the PEPP []. These are: introduction with a focus to learn more about PD, self-monitoring, stress, anxiety and depression, communication, enriching activities, and my life with PD (Figure 1). One topic is in focus each time the group meets and each session is two hours long. During each session, the PwPDs and care partners meet in a small group of 12–14 participants. A certified educator, a health care professional with extensive experience of supporting PwPDs and their care partners, as well as with medical knowledge of PD, guides the group through the sessions. The educator has been trained to deliver the contents of the NPS and has been educated about the underlying concepts and aims of the program. Each session of the NPS program has a certain standardized structure, which begins with an introduction involving facts and information on a topic related to everyday life with PD. This is followed by group discussions relating to the information which has been presented. Group discussions focus on participants’ own experiences and thoughts, and provide an opportunity for peer learning and support found to be valuable and important by participants []. The new knowledge presented during the session is afterwards applied to the participants’ own life situation through practical exercises and home assignments, which are discussed and followed up during the next session. Each session of the NPS ends with a 15-min relaxation exercise.

Figure 1.

Modular elements of the Swedish National Parkinson School.

4.2. Outlook and Evaluation

Approximately 20–30 groups undergo the NPS in clinical care in Sweden each year. The program has until now mainly been provided at neurological and geriatric clinics connected to the larger hospitals, which is due to the allocation of resources in the Swedish health care system. With improved and widespread technology like easy and available apps for video conferences, new ways of providing the NPS also to persons living in more remote areas are under development. Recent research shows that the NPS is considered valuable for the participants and contributes to enhanced adaptation and acceptance of life with PD as well as techniques for self-knowledge to manage symptoms of disease in everyday life. The dyadic approach was viewed as a shared platform of knowledge and understanding and the small group format exchanging experiences and feeling support from others in the same situation was highly appreciated []. After attending the NPS, PwPDs’ own perception of their health status was improved as well as their shift in approach to not letting the disease control life and their knowledge of strategies to handle symptoms []. The techniques of self-monitoring introduced in the NPS remained a strategy for PwPDs and care partners to explain and communicate health status in clinical encounters with the physician [].

5. Concept for a Nationwide Structured Self-Management Education (SME) Program in Germany

Given the high importance of self-management for PwPDs and given the sometimes decade-long nationwide availability of certified SME programs for persons with similar diseases in Germany, PwPDs should have the same opportunity to benefit from the general availability of such a structured, evidence-based and quality-controlled program. In order for this to become reality, the same level of professional effort is needed that enabled the nationwide availability of programs for other comparable diseases.

In spite of the evidence for efficacy/effectiveness for a variety of existing programs for PwPDs worldwide, the effects were comparably small, not always reproducible and exposed to an important attrition effect often already 6-months post intervention (Table 1, and Section 3.4 above). Although most programs make some reference to the self-management concept, content and implementation strategies vary largely. The Swedish National Parkinson School is to our knowledge the only example of sustainable nationwide establishment of such a program, and for its basis (PEPP) there is arguably the most evidence for effectiveness.

However, existing programs should rather be understood as a valuable source of inspiration then as a ready-made solution that simply needs to be implemented broadly. Most concepts have never achieved the stage of broad sustainable implementation, or in the case of the PEPP were developed 18 years ago. It is very unlikely that a program developed in 2002 still provides the optimal answer to needs, expectations and best implementation strategies in the context of rapidly evolving living conditions and a disruptive digital transformation process taking place.

Any novel and future-orientated program can profit from the knowledge and experience generated through the various existing programs, but equally requires innovations concerning content, delivery concept including possible digital components, concerning a meaningful evaluation concept and to meet the regulatory requirements for a nationwide certification.

In the following sections, conceptual considerations about possible areas of improvement for a future-orientated and sustainable SME program are given. In addition, a sequential implementation concept is presented, consisting of 4 phases from a structured needs assessment of both PwPDs and experts to the final step of obtaining certification as the basis for nationwide implementation in Germany.

5.1. Conceptual Considerations

5.1.1. Different Program Content and/or Delivery Concept Needed for Different Disease Stages?

One potential shortcoming is that there is no concept for a disease-stage adopted program. It is unclear when PwPDs are to be educated, whether this education should be repeated over the decade-long disease course, and if so, how much of the program needs to be adopted to possibly target several subpopulations. As described, in Canada such disease-stage-specific SME programs have been implemented, consisting of three subprograms: an early program for general disease management (EMP), an intermediate program for safe mobility (SMP), and a late-stage program for fall prevention (FPP) []. So far, only immediate post-intervention effects have been reported for the first of the three programs, targeting the early disease stage.

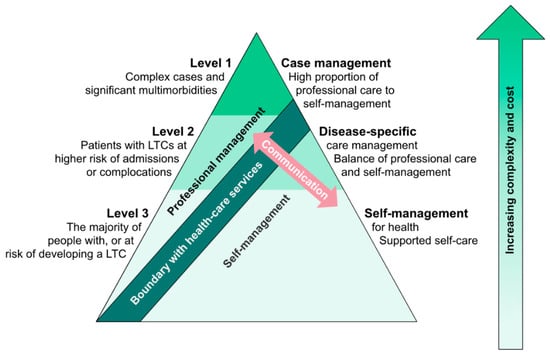

However, theoretical considerations about the varying requirements in self-management over the course of chronic diseases argue for this approach. In diseases like PD, both symptom load and treatment responsiveness vary strongly with time [,]. A conceptual pyramidal model developed by the managed care consortium Kaiser Permanente illustrates that the relative importance of self-management on the one side and professional disease management on the other is a function of the complexity of the therapeutic needs for a specific chronic disease: The less complex the needs are, the more affected persons can achieve through self-management independently, whereas with increasing complexity the relevance of professional medical disease management increases [,] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

“Kaiser pyramid” about the interaction between patient disease-related self-management and professional management. In chronic diseases with little complexity in disease burden and/or therapeutic needs (level 3), self-management by persons with chronic conditions (PwCDs) is the major contributor to overall management, relative to the minor contribution of professional disease management. The more complex the disease and related therapeutic needs become (levels 2 and 1), the smaller becomes the relative contribution of self-management in comparison to professional management. The higher the relevance of professional management becomes, the more important becomes professional management support, e.g., by structured case management. Adopted from [].

PwPDs can be expected to wander along this “pyramid” during their disease course: In the honeymoon phase therapeutic needs are of lower complexity and the relative contribution of person self-management to overall disease management can be expected to be high [,]. In intermediate and early advanced diseases stages the therapeutic complexity increases sharply and with this the relative importance of professional disease management. In late disease stages, one could argue that the possible professional therapeutic contribution diminishes again, accompanied by an increase in the relative contribution of person self-management. Thus, even if it is arguable how well the “Kaiser pyramid” is applicable to PwPDs, it illustrates that the need in SME will vary importantly during the course of a sometimes decade-long chronic disease, both in content and possibly also in the delivery concept.

Another argument for a stage-specific program design is the importance of modeling and social persuasion for successful self-management interventions []. The better participants can relate to each other and the better the program is related to the participant’s contextual living situation, the easier it will be to achieve the intended behavioral changes. Regarding this, it is questionable how well PwPDs in early disease stages are to be expected to relate to PwPDs in advanced disease stages and with a much heavier affected living reality [].

A third argument for stage-specific program is that cognitive capacities are inflicted along the disease course, with nearly all PwPDs to be expected to become demented in advanced disease stages []. Since all self-management programs follow the principles of cognitive behavioral therapy, not only the content, but also the content delivery should be adopted to varying cognitive capacities.

5.1.2. Importance of Disease-Related Information and Knowledge Skills

The PEPP has a strong strategic focus on the CBT-based self-management intervention and dedicates the majority of the program to teaching behavioral skills such as action planning, self-reflection, reframing, self-efficacy beliefs or relaxation techniques []. Relatively little of the time is reserved for disease-related information. The focus is rather on the skill of self-dependent retrieval of high-quality information from public information resources than on actual information provision. However, given the complexity of the disease, of medication-induced complications and of the high importance of informed self-monitoring, it is questionable whether teaching relevant knowledge should not be strengthened without weakening the efforts in SME. The importance of actual knowledge transfer is also fueled by the limited availability of cost-free high-quality person-orientated information offers.

5.1.3. Digitalization as a Promising Measure against Effect Attrition

The effects of all SME programs are exposed to attrition []. Even if this lies in the nature of all behavioral interventions, the ambition to achieve measurable effects for time periods longer than 6 months appears reasonable. Therefore, it is important to consider strategies to consolidate the newly acquainted behavioral competences. Previous studies have already postulated the need of a “booster effect” [].

In addition, any future program needs to be cost-effective to achieve financing agreements with statutory health insurers as the only realistic long-term financer in Germany. Continuous disease-accompanying SME will most likely neither be feasible nor financeable. Therefore, complementing SME with a digital and possibly long-term follow-up intervention appears as the only realistic option to promote more sustainable effects than with the current and mostly purely analogue programs.

The potential of a possible digital extension is illustrated by the growing body of evidence for the effectiveness of online behavioral cognitive therapy, including for elderly PwCDs []. In addition, results from a preliminary focus group on PwPDs’ needs revealed an acceptance of online supplementary elements.

If the goal of any future SME program is to assure equal access, than a digitalized automated program element is likely the most effective measure to achieve this.

5.1.4. Combination with Related Therapeutic Interventions

Many of the preceding programs combined SME with other therapeutic interventions, such as physiotherapy or occupational therapy. It is unclear whether SME programs are more or less effective when combined with other interventions, in spite of single studies addressing this question [].

However, such a combination appears as a promising concept: If self-management relies on the mastery of skills needed for induction and maintenance of health-promoting behavioral change and if domain-specific training (modeling) of these skills is an important strategy [,], then the combination with therapeutic interventions in domains such as physical activity appears as a synergic approach.

5.1.5. Evaluation Concepts for SME Programs

As mentioned, in a majority of studies distal complex outcomes such as QoL have been reported as primary outcome, although only an indirect effect through mediators and/or more proximal outcomes can be postulated. This provides one possible explanation for the often small effects in combination with relatively rapid effects attrition.

The importance of a careful study design has been recently illustrated by a recent Swedish quasi-experimental case-control study on the NPS []. Although some beneficial effects on QoL could be detected immediately after the intervention by within-group comparisons, effects on other outcome variables only became apparent by longitudinal between-group comparisons: Whereas satisfaction with life as a whole decreased in the control group, it remained stable in the intervention group, an effect that would have been missed without a longitudinal between group comparisons. Several studies have considered the importance of possible confounders, effect moderators or mediators, but have failed to illustrate an impact of any of the studied constructs [,]. Mostly no rationale is given for the relative importance of the constructs considered as possible confounders and/or mediators, and the respective studies do not report on their power to illustrate the postulated effects and, therefore, have to be considered exploratory.

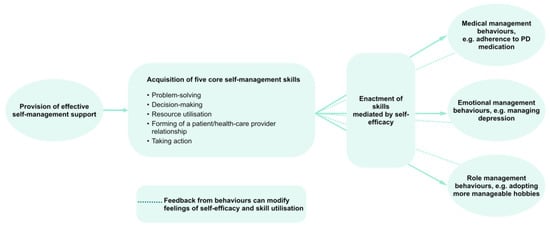

In order to avoid the sole reliance on distal complex outcomes such as QoL, exposed to a multitude of effects besides the SME program to be evaluated, evaluation concepts should consider the theoretical basis of SME programs. As mentioned, the starting point of numerous SME programs is the Chronic Disease Self-Management Program (CDSMP) that is based on Bandura’s theory of behavioral change, validated in numerous studies not only on health-related, but also on general behaviors [,]. Only if the underlying cascade of Bandura’s theory, ranging from skills over self-efficacy beliefs to self-management behaviors, is functional, can an effect on distal outcomes such as QoL be expected. To understand how effects are transmitted through this cascade, evaluation concepts should measure not only distal outcomes, but all intermediate constructs and their dependencies as established by the theory of behavioral change (Figure 3). Considering that self-management behaviors are the primary target of SME programs, there is a strong rationale for not defining QoL as the primary outcome, but self-management behaviors and their (sustained) improvement.

Figure 3.

Structural effects model for SME interventions according to the theory of behavioral change. Adopted from [].

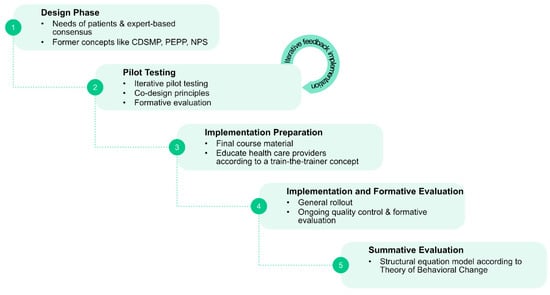

5.2. Sequential Design and Implementation Concept for a Certified Nationwide SME Program for PwPDs

To address the above mentioned issues and to achieve the goal of a nationwide certified PwPD SME program, the following sequential phases are suggested (Figure 4):

Figure 4.

Sequential phases suggested for needs assessment (phase 1), design (phase 2), evaluation for effectiveness (phase 3), and for certification and nationwide implementation of a structured SME program for PwPDs (phase 4).

- (1)

- Phase 1: Systematic needs assessment of PwPDs and caregivers in combination with an expert-based consensus about contents, delivery concepts and program objectives;

- (2)

- Phase 2: Development of an SME program in an dynamic co-design process, including formative evaluation;

- (3)

- Phase 3: Proof of efficacy and proof of effectiveness in a multicenter setting, representative of the later application context;

- (4)

- Phase 4: Obtain certification and agreement of funding with statutory health insurers.

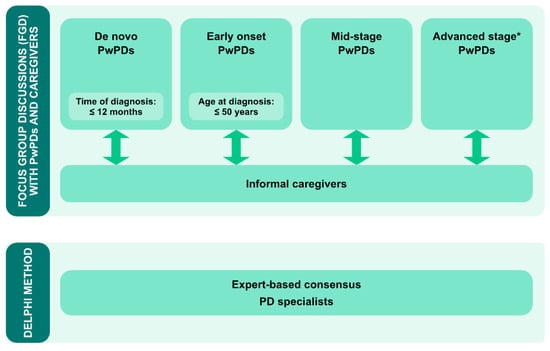

5.2.1. Phase 1: Systematic Assessment of Needs of PwPDs and Caregivers and Expert-Based Consensus Process

As a first step, the needs of both PwPDs and their caregivers are to be systematically analyzed (Figure 5). Both groups should be iteratively involved along the entire development and evaluation phase to assure patient and caregiver engagement due to constant interaction with the program design team.

Figure 5.

Concept for phase 1: structured assessment of needs of PwPDs and their caregivers by disease-stage specific focus groups (upper panel). Structured expert-based Delphi consensus process on expert recommendations on content, format and objectives of a PD-specific PME program. * Advanced disease stage will be defined according to [].

To understand expected disease-stage specific needs from the beginning of the process, four different person subgroups are to be assessed separately for their specific needs in a structured format, e.g., focus groups: (1) de-novo PwPDs (defined by time since diagnosis ≤12 months); (2) early onset PwPDs (≤50 years); (3) general early to mid-stage PwPDs (defined as PwPDs not fulfilling the criteria for the subgroups 1,2 and 4), and (4) PwPDs with advanced disease stages (defined by consented criteria for advanced PD []. This differential approach is deemed necessary to understand disease-stage specific needs in enough detail for the design of disease-stage specific components. This holds especially true for young PwPDs and their caregivers, as this group typically faces very distinct self-management challenges (e.g., underaged children, professions) compared to older PwPDs [].

Focus groups will be distributed in a geographically representative manner over Germany to consider a potential impact of regional region cultural contexts. Simultaneous, but separate, focus groups for caregivers will be organized to assess their specific needs, potentially distinct from the needs of PwPDs. Two focus groups with PwPDs and caregivers each were already administered as a pilot.

This person-centered needs assessment will be complemented by an expert-based Delphi consensus process to obtain recommendations and expectations of PD specialists both about content and delivery format [] (Figure 5). Experts from several PD-related sub-specializations will be approached, such as specialists for deep brain stimulation (DBS), continuous treatment options or non-pharmacologic treatment options. Besides gathering expert advice, the structured assessment of the experts’ perspective should help to assure professional acceptance, which is an important success criterion for the later program.

Overall, the results from the focus group discussions and the Delphi consensus will constitute the knowledge base for a person-centered concept and design phase to follow.

5.2.2. Phase 2: Program Development and Formative Evaluation

Based on the comprehensive needs assessment and on the experiences with the existing programs, a new SME program needs to be developed (Figure 6). How much of the former programs can be overtaken will depend on the directions given in the needs assessments concerning the core questions as formulated above: e.g., whether and if how many disease-stage specific components are needed; what importance should be given to disease-related knowledge transfer; or what degree and what strategy is most promising to integrate digital components to a future program. The design process should follow iterative co-design principles to assure that new developments are constantly evaluated for their appropriateness from the target group’s perspective []. Adherence to concepts for agile product development is to assure that several iterative rounds of developing, testing and evaluation can be carried out. Both qualitative and quantitative formative evaluation methods will be applied.

Figure 6.

Sequential steps in phase 2.

5.2.3. Phase 3: Summative Evaluation of the New Concept for Efficacy and Effectiveness

As soon as the new program has achieved a sufficient maturity according to the repetitive formative testing, it will be assessed for efficacy in an adequately sized randomized controlled pilot trial. The evaluation concept should be in compliance with the effects model behind the theory of behavioral change and will comprise measurement instruments for all relevant constructs, as described.

After efficacy has successfully been established, a multicenter trial is to follow to illustrate effectiveness in a real-world scenario. For this to be achieved, not only the quality and maturity of the new SME program itself will be relevant, but also the design of adequate related management and quality control mechanisms, e.g., the schooling concept for the effectuating healthcare providers and a concept to assure sufficient procedural program adherence in diverse implementation settings.

5.2.4. Phase 4: Program Certification in Compliance with German Legislative and Institutional Regulations

To implement an SME program into the regular care process in Germany, developers have to address several requirements in a standardized process on quality, structure, outcome and content of the program [].

The association of statutory health insurers in Germany developed “joined recommendations for the promotion and implementation of patient education programs” as early as 2001 (recently updated) to assist more than 100 statutory health insurances in Germany in the evaluation of SME programs []. The main criteria is the overall effectiveness [].

5.2.5. Legal Foundations

The German Social Insurance Code (SGB V) regulates the legal basis for the promotion and implementation of SME programs for persons with chronic long-term conditions.

Before approving a specific SME program, an insurer has to inspect the evidence for effectiveness. Expert opinion can be requested from the “Medizinischer Dienst der Krankenkassen (MDK)”, a service unit developed jointly by the statutory health insurances to control medical care processes. To be formally assessed, information has to be submitted on the structure and content of the program together with information about its effectiveness, local facilities and proof of qualification of the interdisciplinary educational team [] (Table 4). This inspection process has to be completed before program inscription starts.

Table 4.

Required documentation and information about the program to be certified [,].

Applicants receive a non-negotiable approval or refusal note. Approval comes with a valid certificate, but the specific reimbursement still has to be negotiated with each of the statutory health insurers separately. Even though this process is heavily regulated, strengths are the standardized and transparent requirements, offering equal chances to all applicants.

Reimbursement can be granted if the insured person recently received medical treatment for a specific disease or is currently proceeding such a treatment and if the participation rate was >80% []. Caregivers are to be involved if indicated by medical reasons.

6. Discussion

Despite the numerous arguments for a structured SME program for PwPDs and despite the fact that persons with similar chronic diseases (e.g., diabetes, asthma) have access to such programs as part of the regular catalogue of benefits of statutory health insurers, so far this could not be achieved for PwPDs in Germany. To our knowledge, The NPS in Sweden is the only example of nationwide coverage with an SME program for PwPDs.

However, there are many arguments why this should not be the exception but the norm. It is widely accepted that integrated care concepts should be person-centered [,]. Therefore, probably the most important argument is that PwPDs repetitively state that self-management support is their top priority in the context of integrated care approaches [,]. In addition, PwPDs can be expected to face comparatively high challenges in self-management, given the multidimensionality of symptoms and the high complexity of the therapeutic measurements. If self-management behaviors substantially contribute to health-related outcomes according to theoretical considerations (e.g., “Kaiser pyramid” []), both PwPDs’ and experts’ assumptions [,] and clinical evidence from various programs, then one could conclude that self-management education should be one of the core elements of any integrated care concept for PwPDs.

Person-centered care considers the needs of all persons involved in a care relationship—be it the patient, informal or formal healthcare providers—to be of equal importance []. SME is in this context an effective measurement to promote person-centered care because it does not only address the needs of patients but also the needs of healthcare providers to profit from self-management-competent patients in their efforts to provide optimal care.

As mentioned, there are only few reported studies on temporary regional efforts in structured SME for PwPDs in Germany [,,,]. However, this does not mean that there currently is no self-management support—only that it is mostly provided in an informal manner and without standardized professional education on how to deliver it. Most likely, many healthcare professionals are not aware that they have integrated self-management support into their personal strategy of caring for PwPDs. Such informal self-management support does not facilitate the assurance of equal access independent of socioeconomic patient background or the implementation of measurements for ongoing quality monitoring and improvement.

Leaving self-management support to the discretion and personal capacities of individual healthcare providers is not compatible with the ambition to offer more equal, timely and better quality care through structured integrated care concepts. Whereas some components of integrated care concepts need to be tailored to the specific regional implementation context, SME programs do not belong to these. Rather, basic principles and assumptions have been repetitively shown to be valid across different diseases and implementation settings, including transcultural implementation [].

Taking into consideration the diverse measurements to be undertaken to arrive at a truly future-orientated sustainable SME concept, it appears reasonable to not develop such a program for each integrated care concept separately, but jointly in a collaborative effort. Not only will such an approach be more economic, but several reasons regarding both content and delivery concept speak in favor for a collaborative effort: a person-centered self-management program should profit from a broad spectrum of expert experiences and knowledge, which in turn represents the basis for reaching a sustainable professional consensus and acceptance on content and structure of a future program; both an agile person-centered iterative design process and the development of supporting innovative digital components for such a future-orientated program require significant resources that can better be assured in a joint effort than in several smaller initiatives; ongoing formative and summative evaluation, especially for general program effectiveness, will be facilitated by a mutually agreed evaluation concept and set of measurement instruments.

Last but not least, such a collaborative effort will be the best argument to convince statutory health insurers that PwPDs not only have the same rights as persons with other chronic diseases to benefit from the offer of a structured SME program, but that there also is a high-quality concept available worth being funded, supported both by a strong professional commitment and by a substantial body of evidence for program effectiveness.

The outlined steps to achieve this goal can only be addressed with sufficient resources. For this, public funding needs to be assured through a grant proposal, currently under preparation. Professionals or institutions interested in contributing to this effort, e.g., as a clinical partner, as an expert in person-centered co-design processes, in the evaluation of complex healthcare interventions, or in the design of digitally supported cognitive behavioral therapy and/or SME programs are invited to contact the authors.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/9/9/2787/s1, Figure S1: Study flow diagram, Table S1: PRISMA Checklist, Table S2: Other systematic reviews on different aspects of self-management in Parkinson’s disease.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.T., T.F., C.H., M.H., C.E., K.F.L. Writing—Original Draft Preparation: T.F., C.H., M.H., Ü.S.S., E.K., J.S., T.W., T.L., C.E., K.F.L. Writing—Review and Editing: J.T., T.F., C.H., M.H., Ü.S.S., J.S., T.W., L.T., C.E., K.F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Federal Ministry of Health of the German Federal Government and by the Saxon State Ministry for Social Affairs and Solidarity (grant number: 100386587).

Conflicts of Interest

J.S. is the CEO of the Tumaini Institut für Präventionsmanagement GmbH, a SME working in the field of prevention of lifestyle-associated diseases and developing and implementing patient education programs for chronic diseases. Lars Tönges has received travel funding and/or speaker honoraria from Abbvie, Bayer, Bial, Desitin, G.E., U.C.B., and Zambon, and consulted for Abbvie, Bayer, Bial, Desitin, U.C.B., and Zambon, in the last 3 years. C.E. received in the last 12 months payments as a consultant for Abbvie Inc. C.E. received honoraria as a speaker from Abbvie Inc. He received payments as a consultant for Abbvie Inc. and Philyra Inc. K.F.L. has received travel funding and/or speaker honoraria from Abbvie and Licher M.T. and consulted for Abbvie and Stadapharm, in the last 3 years. The other authors do not report any conflict of interest.

References

- Minkman, M. The development model for integrated care: A validated tool for evaluation and development. J. Integr. Care 2016, 24, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouwens, M.; Wollersheim, H.; Hermens, R.; Hulscher, M.; Grol, R. Integrated care programmes for chronically ill patients: A review of systematic reviews. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2005, 17, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorig, K.R.; Holman, H.R. Self-management education: History, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 2003, 26, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medicine, I.O. The 1st Annual Crossing the Quality Chasm Summit: A Focus on Communities; Adams, K., Greiner, A.C., Corrigan, J.M., Eds.; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; p. 176. [Google Scholar]

- Radder, D.L.; Nonnekes, J.; van Nimwegen, M.; Eggers, C.; Abbruzzese, G.; Alves, G.; Browner, N.; Chaudhuri, K.; Ebersbach, G.; Ferreira, J.J. Recommendations for the organization of multidisciplinary clinical care teams in parkinson’s disease. J. Parkinson’s Dis. 2020, 10, 1087–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, D.; Hauteclocque, J.; Grimes, D.; Mestre, T.; Côtéd, D.; Liddy, C. Development of the integrated Parkinson’s care network (IPCN): Using co-design to plan collaborative care for people with Parkinson’s disease. Qual. Life Res. 2019, 28, 1355–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaanderen, F.P.; Rompen, L.; Munneke, M.; Stoffer, M.; Bloem, B.R.; Faber, M.J. The voice of the Parkinson customer. J. Parkinson’s Dis. 2019, 9, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.J.; Pinnock, H.; Epiphaniou, E.; Pearce, G.; Parke, H.L.; Schwappach, A.; Purushotham, N.; Jacob, S.; Griffiths, C.J.; Greenhalgh, T. A rapid synthesis of the evidence on interventions supporting self-management for people with long-term conditions: PRISMS–Practical systematic review of self-management support for long-term conditions. Health Serv. Deliv. Res. 2014, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachana, N.A.; Egan, S.J.; Laidlaw, K.; Dissanayaka, N.; Byrne, G.J.; Brockman, S.; Marsh, R.; Starkstein, S. Clinical issues in the treatment of anxiety and depression in older adults with Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2013, 28, 1930–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlenk, E.A.; Burke, L.E.; Rand, C. Behavioral Strategies to Improve Medication-Taking Compliance. Compliance in Healthcare and Research; Futura Publishing Co: Armonk, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Center for the Advancement of Health. Essential Elements of Self-Management Interventions; Center for the Advancement of Health: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lorig, K.R.; Ritter, P.; Stewart, A.L.; Sobel, D.S.; Brown, B.W., Jr.; Bandura, A.; Gonzalez, V.M.; Laurent, D.D.; Holman, H.R. Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Med. Care 2001, 39, 1217–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.R.; Sobel, D.S.; Ritter, P.L.; Laurent, D.; Hobbs, M. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Eff. Clin. Pract. 2001, 4, 256–262. [Google Scholar]

- Lorig, K.R.; Sobel, D.S.; Stewart, A.L.; Brown, B.W., Jr.; Bandura, A.; Ritter, P.; Gonzalez, V.M.; Laurent, D.D.; Holman, H.R. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: A randomized trial. Med. Care 1999, 37, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, R.; Allegrante, J.P. A review and synthesis of research evidence for self-efficacy-enhancing interventions for reducing chronic disability: Implications for health education practice (part II). Health Promot. Pract. 2005, 6, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, R.; Allegrante, J.; Lorig, K. A review and synthesis of research evidence for self-efficacy-enhancing interventions for reducing chronic disability: Implications for health education practice (part I). Health Promot. Pract. 2005, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darrah, J.; Hickman, R.; O’Donnell, M.; Vogtle, L.; Wiart, L. AACPDM Methodology to Develop Systematic Reviews of Treatment Interventions (Revision 1.2); American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2008; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, M.A.; Iyer, S.S.; Englert, D.; Sanjak, M. Promoting exercise in Parkinson’s disease through community-based participatory research. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2011, 1, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindskov, S.; Westergren, A.; Hagell, P. A controlled trial of an educational programme for people with Parkinson’s disease. J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 16, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, R.A.; Elman, J.G.; Huijbregts, M.P. Self-management programs for people with Parkinson’s disease: A program evaluation approach. Top. Geriatr. Rehabil. 2008, 24, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, H.; Arps, G.; Bancroft, N.; Mountfort, R.; Polkinghorne, A. ‘Living Well with Parkinson’s’: Evaluation of a programme to promote self-management. J. Nurs. Healthc. Chronic Illn. 2011, 3, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, H.; Hazan, J.; Wilson, P. Self-management for people with long-term neurological conditions. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2012, 17, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarta-Sánchez, M.; Ursua, M.; Fernández, M.R.; Ambrosio, L.; Medina, M.; de Cerio, S.D.; Álvarez, M.; Senosiain, J.; Gorraiz, A.; Caparrós, N. Implementation of a multidisciplinary psychoeducational intervention for Parkinson’s disease patients and carers in the community: Study protocol. BMC Fam. Pract. 2018, 19, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyons, K.S.; Zajack, A.; Greer, M.; Chaimov, H.; Dieckmann, N.F.; Carter, J.H. Benefits of a self-management program for the couple living with Parkinson’s disease: A pilot study. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2020, 0733464820918136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellqvist, C.; Berterö, C.; Hagell, P.; Dizdar, N.; Sund-Levander, M. Effects of self-management education for persons with Parkinson’s disease and their care partners: A qualitative observational study in clinical care. Nurs. Health Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A’campo, L.; Spliethoff-Kamminga, N.; Roos, R. An evaluation of the patient education programme for Parkinson’s disease in clinical practice. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2011, 65, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajatovic, M.; Ridgel, A.L.; Walter, E.M.; Tatsuoka, C.M.; Colón-Zimmermann, K.; Ramsey, R.K.; Welter, E.; Gunzler, S.A.; Whitney, C.M.; Walter, B.L. A randomized trial of individual versus group-format exercise and self-management in individuals with Parkinson’s disease and comorbid depression. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2017, 11, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunvisson, H.; Ekman, S.L.; Hagberg, H.; Lökk, J. An education programme for individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2001, 15, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Jiang, Y.; Yatsuya, H.; Yoshida, Y.; Sakamoto, J. Group education with personal rehabilitation for idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2009, 36, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tickle-Degnen, L.; Ellis, T.; Saint-Hilaire, M.H.; Thomas, C.A.; Wagenaar, R.C. Self-management rehabilitation and health-related quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: A randomized controlled trial. Mov. Disord. 2010, 25, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegert, C.; Hauptmann, B.; Jochems, N.; Schrader, A.; Deck, R. ParkProTrain: An individualized, tablet-based physiotherapy training programme aimed at improving quality of life and participation restrictions in PD patients—A study protocol for a quasi-randomized, longitudinal and sequential multi-method study. BMC Neurol. 2019, 19, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Horne, J.T.; Soh, D.; Cordato, D.J.; Campbell, M.L.; Schwartz, R.S. Functional outcomes of an integrated Parkinson’s disease wellbeing program. Australas. J. Ageing 2020, 39, e94–e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L.; Peterson, D.; Mancini, M.; Carlson-Kuhta, P.; Fling, B.; Smulders, K.; Nutt, J.; Dale, M.; Carter, J.; Winters-Stone, K. Do cognitive measures and brain circuitry predict outcomes of exercise in Parkinson Disease: A randomized clinical trial. BMC Neurol. 2015, 15, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellqvist, C.; Berterö, C.; Dizdar, N.; Sund-Levander, M.; Hagell, P. Self-management education for persons with parkinson’s disease and their care partners: A quasi-experimental case-control study in clinical practice. Parkinson’s Dis. 2020, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellqvist, C.; Dizdar, N.; Hagell, P.; Berterö, C.; Sund-Levander, M. A national Swedish self-management program for people with Parkinson’s disease: Patients and relatives view. In Proceedings of the 21st International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 4–8 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hellqvist, C.; Dizdar, N.; Hagell, P.; Berterö, C.; Sund-Levander, M. Improving self-management for persons with Parkinson’s disease through education focusing on management of daily life: Patients’ and relatives’ experience of the Swedish National Parkinson School. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 3719–3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A’Campo, L.E.I.; Wekking, E.; Spliethoff-Kamminga, N.; Stijnen, T.; Roos, R. Treatment effect modifiers for the patient education programme for Parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2012, 66, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chlond, M.; Bergmann, F.; Güthlin, C.; Schnoor, H.; Larisch, A.; Eggert, K. Patient education for patients with Parkinson’s disease: A randomised controlled trial. Basal Ganglia 2016, 6, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, G.; Thompson, S.B.; Pasqualini, M.C.S.; Members of the EduPark. An innovative education programme for people with Parkinson’s disease and their carers. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2006, 12, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macht, M.; Gerlich, C.; Ellgring, H.; Schradi, M.; Rusiñol, À.B.; Crespo, M.; Prats, A.; Viemerö, V.; Lankinen, A.; Bitti, P.E.R. Patient education in Parkinson’s disease: Formative evaluation of a standardized programme in seven European countries. Patient Educ. Couns. 2007, 65, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiihonen, S.; Lankinen, A.; Viemerö, V. An evaluation of a cognitive-behavioral patient education program for persons with Parkinson’s disease in Finland. Nord. Psychol. 2008, 60, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A’campo, L.; Wekking, E.; Spliethoff-Kamminga, N.; le Cessie, S.; Roos, R. The benefits of a standardized patient education program for patients with Parkinson’s disease and their caregivers. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2010, 16, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, I.B.; Cleary, P.D. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life: A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA 1995, 273, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, D.; Liddy, C. Self-management support programs for persons with Parkinson’s disease: An integrative review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 1787–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandler, S.K.; Robins, J.L.; Kinser, P.A. Nonpharmacologic interventions for the self-management of anxiety in Parkinson’s disease: A comprehensive review. Behav. Neurol. 2019, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, C.L.; Ibrahim, K.; Dennison, L.; Roberts, H.C. Falls self-management interventions for people with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. J. Parkinson’s Dis. 2019, 9, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hulbert, S.M.; Goodwin, V.A. ‘Mind the gap’—A scoping review of long term, physical, self-management in Parkinson’s. Physiotherapy 2020, 107, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, E.R.; Bedekar, M.; Tickle-Degnen, L. Systematic review of the effectiveness of occupational therapy–related interventions for people with Parkinson’s disease. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2014, 68, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A’campo, L.; Ibrahim, K.; Dennison, L.; Roberts, H.C. Caregiver education in Parkinson’s disease: Formative evaluation of a standardized program in seven European countries. Qual. Life Res. 2010, 19, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlborg, C. Pilot testing of the Swedish national Parkinson school—“Meeting others equally important as the knowledge itself”. Parkinsonjournalen 2013, 4, 42–43. [Google Scholar]

- Carlborg, C. E new Swedish national Parkinson School can make life simpler and more enjoyable. Parkinsonjournalen 2013, 3, 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kalia, L.V.; Lang, A.E. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 2015, 386, 896–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, R.; Klucken, J.; Weiss, D.; Tönges, L.; Kolber, P.; Unterecker, S.; Lorrain, M.; Baas, H.; Müller, T.; Riederer, P. Classification of advanced stages of Parkinson’s disease: Translation into stratified treatments. J. Neural Transm. 2017, 124, 1015–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenheimer, T.; Wagner, E.H.; Grumbach, K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA 2002, 288, 1775–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodenheimer, T.; Wagner, E.H.; Grumbach, K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: The chronic care model, Part 2. JAMA 2002, 288, 1909–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasano, A.; Fung, V.S.; Lopiano, L.; Elibol, B.; Smolentseva, I.G.; Seppi, K.; Takáts, A.; Onuk, K.; Parra, J.C.; Bergmann, L. Characterizing advanced Parkinson’s disease: OBSERVE-PD observational study results of 2615 patients. BMC Neurol. 2019, 19, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knipe, M.D.W.; Wickremaratchi, M.M.; Wyatt-Haines, E.; Morris, H.R.; Ben-Shlomo, Y. Quality of life in young—Compared with late—Onset Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2011, 26, 2011–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lau, L.M.; Schipper, C.M.; Hofman, A.; Koudstaal, P.J.; Breteler, M.M. Prognosis of Parkinson disease: Risk of dementia and mortality: The Rotterdam study. Arch. Neurol. 2005, 62, 1265–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barak, A.; Hen, L.; Boniel-Nissim, M.; Shapira, N.A. A comprehensive review and a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of internet-based psychotherapeutic interventions. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2008, 26, 109–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Freeman, W.; Lightsey, R. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Häder, M. Delphi-Befragungen: Ein Arbeitsbuch; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, L.; Cummings, E.; Duff, J.; Walker, K. Partnering in digital health design: Engaging the multidisciplinary team in a needs analysis. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2018, 252, 176–181. [Google Scholar]

- Küffner, R.; Musekamp, G.; Reusch, A. Patientenschulung aus dem Blickwinkel der Entwickler. Arthritis Rheuma 2017, 37, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzenverband, G. Gemeinsame Empfehlungen zur Förderung und Durchführung von Patientenschulungen auf der Grundlage von § 43 Abs. 1 Nr. 2 SGB V vom 2. Dezember 2013 in der Fassung vom 08.02.2017; GKV Spitzenverband: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Marburger, H. SGB V-Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung: Vorschriften und Verordnungen; Mit Praxisorientierter Einführung; Walhalla Fachverlag: Regensburg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Küffner, R.; Reusch, A. Schulungen Patientenorientiert Gestalten: Ein Handbuch des Zentrums Patientenschulung; Dgvt-Verlag: Tübingen, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mansoor, K.; Khuwaja, H.M.A. The Effectiveness of a chronic disease self-management program for elderly people: A systematic review. Elder. Health J. 2020, 6, 50–62. [Google Scholar]

- Buetow, S.A.; Martínez-Martín, P.; Hirsch, M.A.; Okun, M.S. Beyond patient-centered care: Person-centered care for Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinson’s Dis. 2016, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).