Structured Care and Self-Management Education for Persons with Parkinson’s Disease: Why the First Does Not Go without the Second—Systematic Review, Experiences and Implementation Concepts from Sweden and Germany

Abstract

:1. Introduction

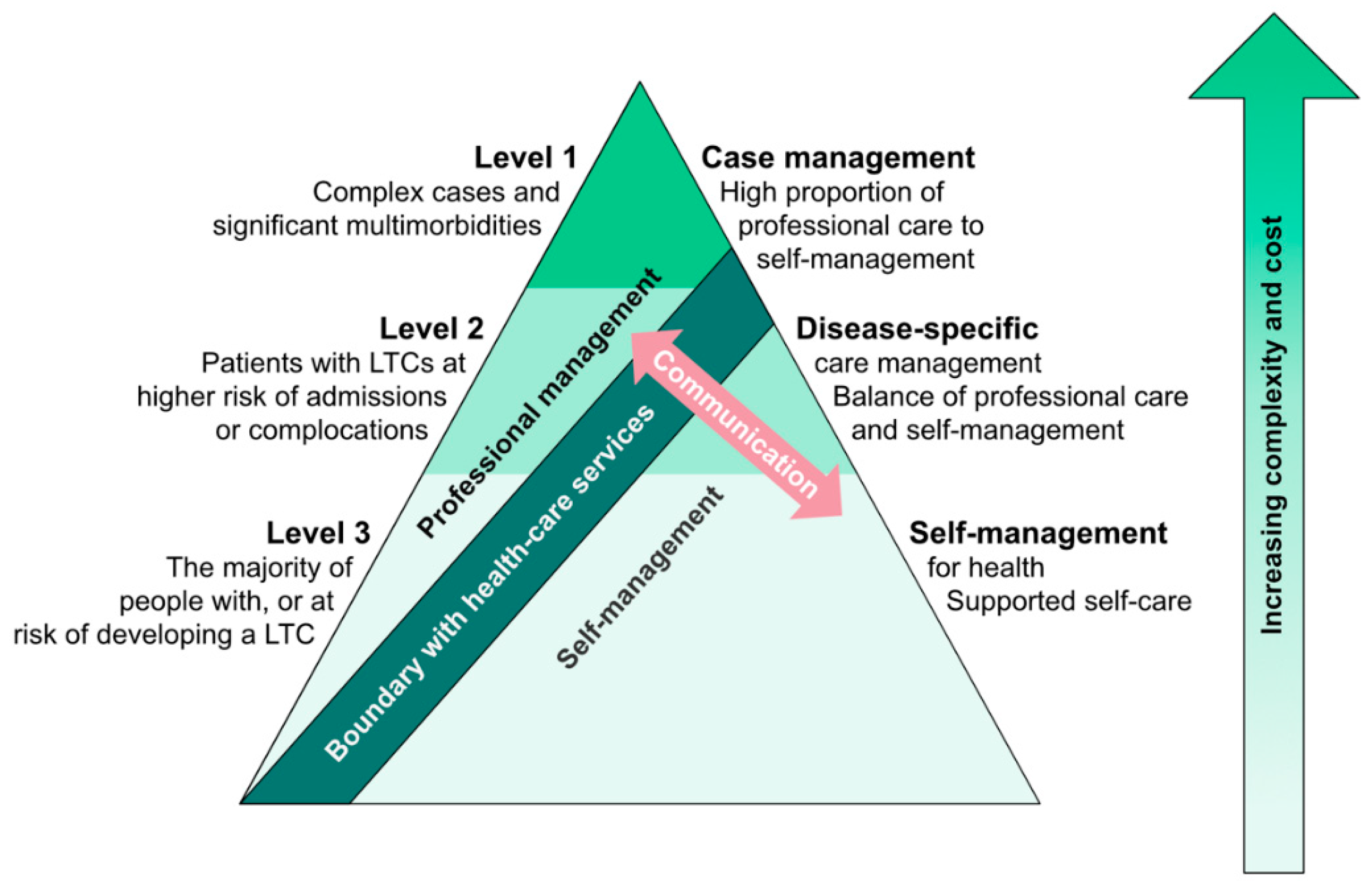

1.1. Integrated Care Concepts and Self-Management

1.2. Components of Self-Management and Conceptual Frameworks

1.3. Implementation of Self-Management Programs

2. Materials and Methods

Systematic Review

3. Results

3.1. General Program Description

3.2. Program Delivery Setting and Organization

3.3. Evaluation and Outcomes Measures

3.4. Efficacy and Effectiveness

3.5. Comparison to Other Systematic Reviews, Limitations

4. Swedish National Parkinson School (NPS)—Example of a Nationwide Implementation of a Self-Management Education Program for Persons with Parkinson’s Disease (PwPDs)

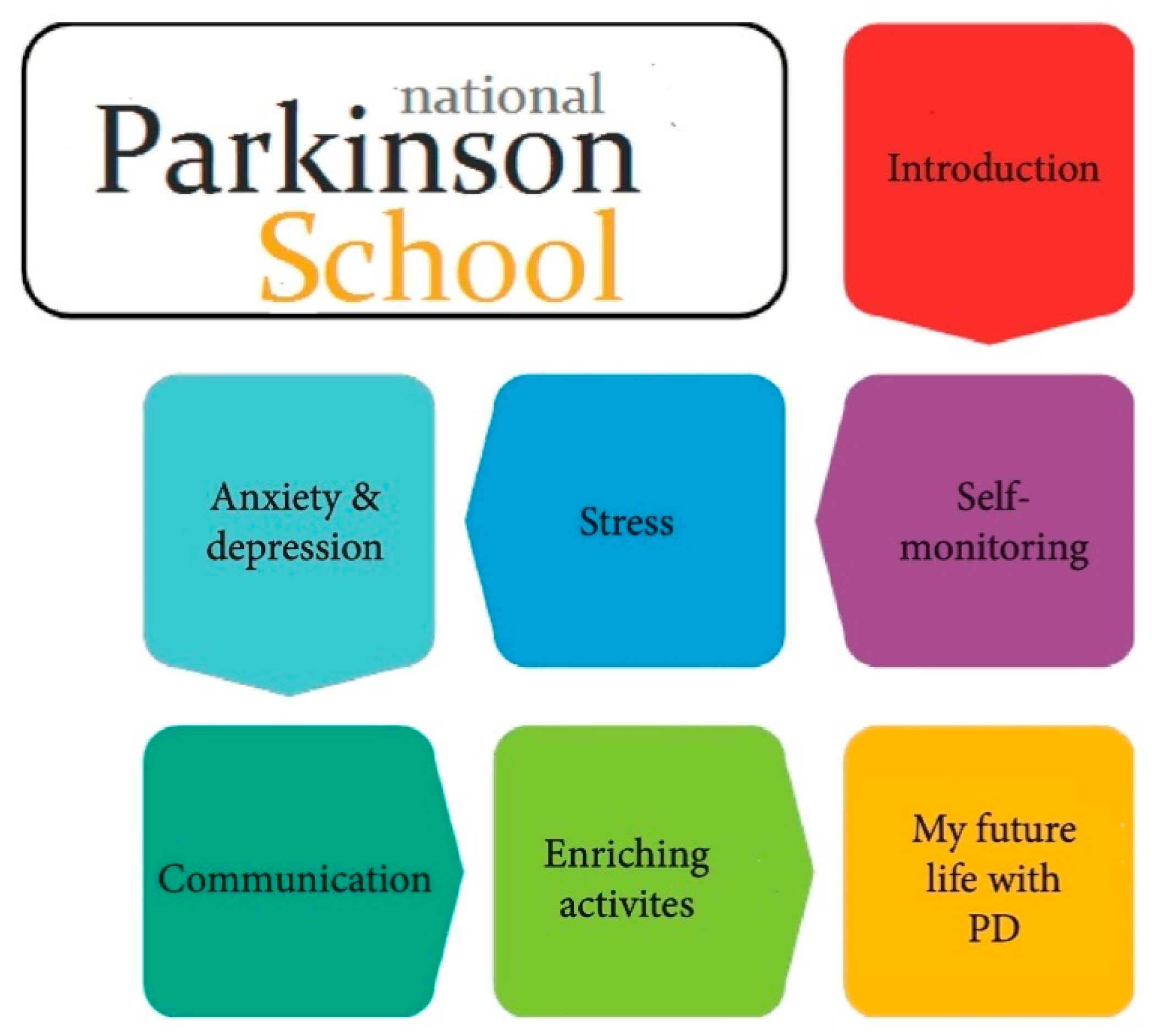

4.1. Program Description

4.2. Outlook and Evaluation

5. Concept for a Nationwide Structured Self-Management Education (SME) Program in Germany

5.1. Conceptual Considerations

5.1.1. Different Program Content and/or Delivery Concept Needed for Different Disease Stages?

5.1.2. Importance of Disease-Related Information and Knowledge Skills

5.1.3. Digitalization as a Promising Measure against Effect Attrition

5.1.4. Combination with Related Therapeutic Interventions

5.1.5. Evaluation Concepts for SME Programs

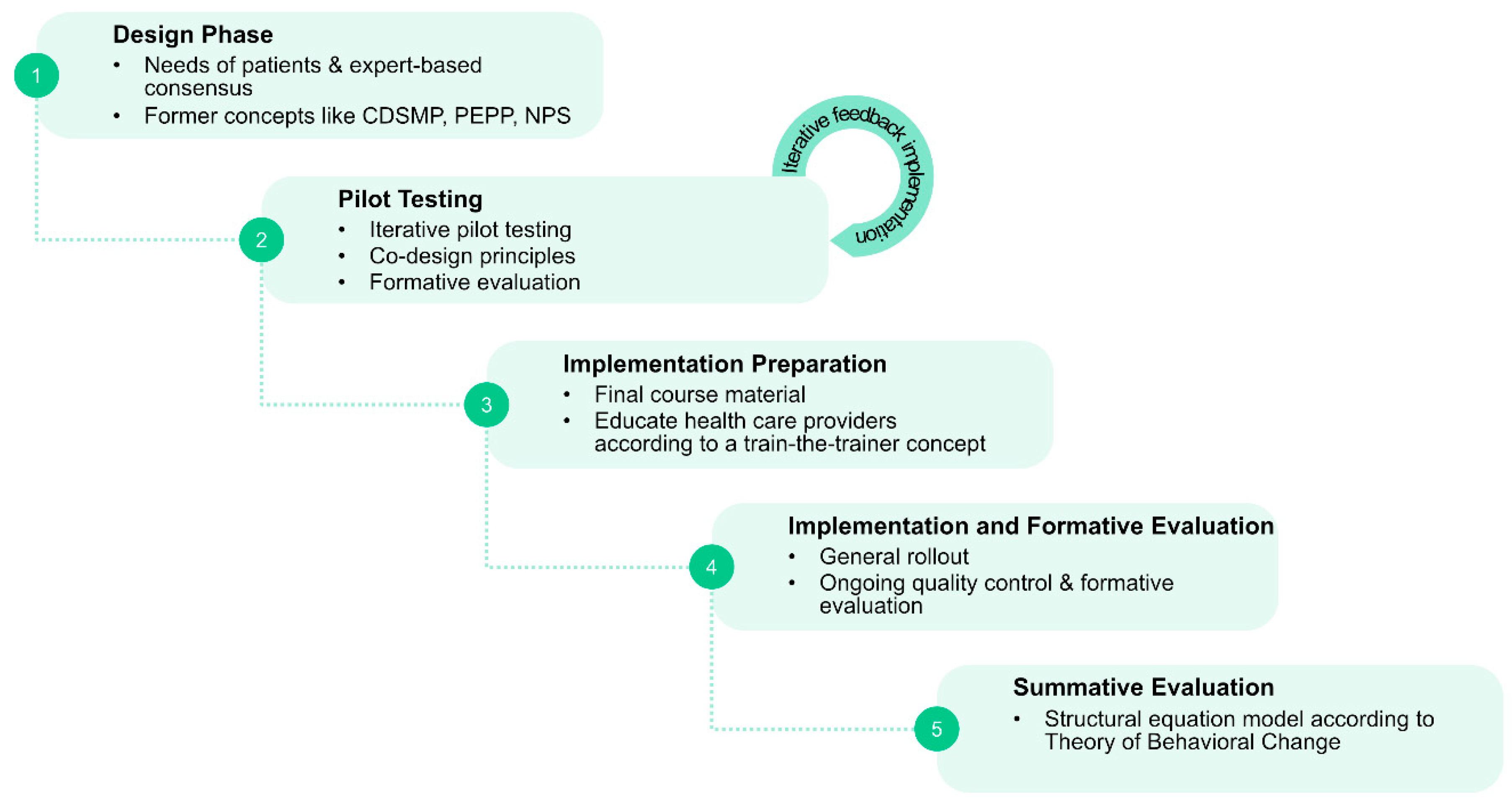

5.2. Sequential Design and Implementation Concept for a Certified Nationwide SME Program for PwPDs

- (1)

- Phase 1: Systematic needs assessment of PwPDs and caregivers in combination with an expert-based consensus about contents, delivery concepts and program objectives;

- (2)

- Phase 2: Development of an SME program in an dynamic co-design process, including formative evaluation;

- (3)

- Phase 3: Proof of efficacy and proof of effectiveness in a multicenter setting, representative of the later application context;

- (4)

- Phase 4: Obtain certification and agreement of funding with statutory health insurers.

5.2.1. Phase 1: Systematic Assessment of Needs of PwPDs and Caregivers and Expert-Based Consensus Process

5.2.2. Phase 2: Program Development and Formative Evaluation

5.2.3. Phase 3: Summative Evaluation of the New Concept for Efficacy and Effectiveness

5.2.4. Phase 4: Program Certification in Compliance with German Legislative and Institutional Regulations

5.2.5. Legal Foundations

6. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Minkman, M. The development model for integrated care: A validated tool for evaluation and development. J. Integr. Care 2016, 24, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouwens, M.; Wollersheim, H.; Hermens, R.; Hulscher, M.; Grol, R. Integrated care programmes for chronically ill patients: A review of systematic reviews. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2005, 17, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lorig, K.R.; Holman, H.R. Self-management education: History, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Ann. Behav. Med. 2003, 26, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medicine, I.O. The 1st Annual Crossing the Quality Chasm Summit: A Focus on Communities; Adams, K., Greiner, A.C., Corrigan, J.M., Eds.; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004; p. 176. [Google Scholar]

- Radder, D.L.; Nonnekes, J.; van Nimwegen, M.; Eggers, C.; Abbruzzese, G.; Alves, G.; Browner, N.; Chaudhuri, K.; Ebersbach, G.; Ferreira, J.J. Recommendations for the organization of multidisciplinary clinical care teams in parkinson’s disease. J. Parkinson’s Dis. 2020, 10, 1087–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, D.; Hauteclocque, J.; Grimes, D.; Mestre, T.; Côtéd, D.; Liddy, C. Development of the integrated Parkinson’s care network (IPCN): Using co-design to plan collaborative care for people with Parkinson’s disease. Qual. Life Res. 2019, 28, 1355–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaanderen, F.P.; Rompen, L.; Munneke, M.; Stoffer, M.; Bloem, B.R.; Faber, M.J. The voice of the Parkinson customer. J. Parkinson’s Dis. 2019, 9, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.J.; Pinnock, H.; Epiphaniou, E.; Pearce, G.; Parke, H.L.; Schwappach, A.; Purushotham, N.; Jacob, S.; Griffiths, C.J.; Greenhalgh, T. A rapid synthesis of the evidence on interventions supporting self-management for people with long-term conditions: PRISMS–Practical systematic review of self-management support for long-term conditions. Health Serv. Deliv. Res. 2014, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pachana, N.A.; Egan, S.J.; Laidlaw, K.; Dissanayaka, N.; Byrne, G.J.; Brockman, S.; Marsh, R.; Starkstein, S. Clinical issues in the treatment of anxiety and depression in older adults with Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2013, 28, 1930–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlenk, E.A.; Burke, L.E.; Rand, C. Behavioral Strategies to Improve Medication-Taking Compliance. Compliance in Healthcare and Research; Futura Publishing Co: Armonk, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 57–70. [Google Scholar]

- Center for the Advancement of Health. Essential Elements of Self-Management Interventions; Center for the Advancement of Health: Washington, DC, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lorig, K.R.; Ritter, P.; Stewart, A.L.; Sobel, D.S.; Brown, B.W., Jr.; Bandura, A.; Gonzalez, V.M.; Laurent, D.D.; Holman, H.R. Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Med. Care 2001, 39, 1217–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorig, K.R.; Sobel, D.S.; Ritter, P.L.; Laurent, D.; Hobbs, M. Effect of a self-management program on patients with chronic disease. Eff. Clin. Pract. 2001, 4, 256–262. [Google Scholar]

- Lorig, K.R.; Sobel, D.S.; Stewart, A.L.; Brown, B.W., Jr.; Bandura, A.; Ritter, P.; Gonzalez, V.M.; Laurent, D.D.; Holman, H.R. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: A randomized trial. Med. Care 1999, 37, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, R.; Allegrante, J.P. A review and synthesis of research evidence for self-efficacy-enhancing interventions for reducing chronic disability: Implications for health education practice (part II). Health Promot. Pract. 2005, 6, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marks, R.; Allegrante, J.; Lorig, K. A review and synthesis of research evidence for self-efficacy-enhancing interventions for reducing chronic disability: Implications for health education practice (part I). Health Promot. Pract. 2005, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Darrah, J.; Hickman, R.; O’Donnell, M.; Vogtle, L.; Wiart, L. AACPDM Methodology to Develop Systematic Reviews of Treatment Interventions (Revision 1.2); American Academy for Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2008; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch, M.A.; Iyer, S.S.; Englert, D.; Sanjak, M. Promoting exercise in Parkinson’s disease through community-based participatory research. Neurodegener. Dis. Manag. 2011, 1, 365–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lindskov, S.; Westergren, A.; Hagell, P. A controlled trial of an educational programme for people with Parkinson’s disease. J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 16, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, R.A.; Elman, J.G.; Huijbregts, M.P. Self-management programs for people with Parkinson’s disease: A program evaluation approach. Top. Geriatr. Rehabil. 2008, 24, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulligan, H.; Arps, G.; Bancroft, N.; Mountfort, R.; Polkinghorne, A. ‘Living Well with Parkinson’s’: Evaluation of a programme to promote self-management. J. Nurs. Healthc. Chronic Illn. 2011, 3, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, H.; Hazan, J.; Wilson, P. Self-management for people with long-term neurological conditions. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2012, 17, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Navarta-Sánchez, M.; Ursua, M.; Fernández, M.R.; Ambrosio, L.; Medina, M.; de Cerio, S.D.; Álvarez, M.; Senosiain, J.; Gorraiz, A.; Caparrós, N. Implementation of a multidisciplinary psychoeducational intervention for Parkinson’s disease patients and carers in the community: Study protocol. BMC Fam. Pract. 2018, 19, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lyons, K.S.; Zajack, A.; Greer, M.; Chaimov, H.; Dieckmann, N.F.; Carter, J.H. Benefits of a self-management program for the couple living with Parkinson’s disease: A pilot study. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2020, 0733464820918136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellqvist, C.; Berterö, C.; Hagell, P.; Dizdar, N.; Sund-Levander, M. Effects of self-management education for persons with Parkinson’s disease and their care partners: A qualitative observational study in clinical care. Nurs. Health Sci. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- A’campo, L.; Spliethoff-Kamminga, N.; Roos, R. An evaluation of the patient education programme for Parkinson’s disease in clinical practice. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2011, 65, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajatovic, M.; Ridgel, A.L.; Walter, E.M.; Tatsuoka, C.M.; Colón-Zimmermann, K.; Ramsey, R.K.; Welter, E.; Gunzler, S.A.; Whitney, C.M.; Walter, B.L. A randomized trial of individual versus group-format exercise and self-management in individuals with Parkinson’s disease and comorbid depression. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2017, 11, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sunvisson, H.; Ekman, S.L.; Hagberg, H.; Lökk, J. An education programme for individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2001, 15, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Jiang, Y.; Yatsuya, H.; Yoshida, Y.; Sakamoto, J. Group education with personal rehabilitation for idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2009, 36, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tickle-Degnen, L.; Ellis, T.; Saint-Hilaire, M.H.; Thomas, C.A.; Wagenaar, R.C. Self-management rehabilitation and health-related quality of life in Parkinson’s disease: A randomized controlled trial. Mov. Disord. 2010, 25, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Siegert, C.; Hauptmann, B.; Jochems, N.; Schrader, A.; Deck, R. ParkProTrain: An individualized, tablet-based physiotherapy training programme aimed at improving quality of life and participation restrictions in PD patients—A study protocol for a quasi-randomized, longitudinal and sequential multi-method study. BMC Neurol. 2019, 19, 143. [Google Scholar]

- Horne, J.T.; Soh, D.; Cordato, D.J.; Campbell, M.L.; Schwartz, R.S. Functional outcomes of an integrated Parkinson’s disease wellbeing program. Australas. J. Ageing 2020, 39, e94–e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, L.; Peterson, D.; Mancini, M.; Carlson-Kuhta, P.; Fling, B.; Smulders, K.; Nutt, J.; Dale, M.; Carter, J.; Winters-Stone, K. Do cognitive measures and brain circuitry predict outcomes of exercise in Parkinson Disease: A randomized clinical trial. BMC Neurol. 2015, 15, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hellqvist, C.; Berterö, C.; Dizdar, N.; Sund-Levander, M.; Hagell, P. Self-management education for persons with parkinson’s disease and their care partners: A quasi-experimental case-control study in clinical practice. Parkinson’s Dis. 2020, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellqvist, C.; Dizdar, N.; Hagell, P.; Berterö, C.; Sund-Levander, M. A national Swedish self-management program for people with Parkinson’s disease: Patients and relatives view. In Proceedings of the 21st International Congress of Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 4–8 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hellqvist, C.; Dizdar, N.; Hagell, P.; Berterö, C.; Sund-Levander, M. Improving self-management for persons with Parkinson’s disease through education focusing on management of daily life: Patients’ and relatives’ experience of the Swedish National Parkinson School. J. Clin. Nurs. 2018, 27, 3719–3728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A’Campo, L.E.I.; Wekking, E.; Spliethoff-Kamminga, N.; Stijnen, T.; Roos, R. Treatment effect modifiers for the patient education programme for Parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2012, 66, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chlond, M.; Bergmann, F.; Güthlin, C.; Schnoor, H.; Larisch, A.; Eggert, K. Patient education for patients with Parkinson’s disease: A randomised controlled trial. Basal Ganglia 2016, 6, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, G.; Thompson, S.B.; Pasqualini, M.C.S.; Members of the EduPark. An innovative education programme for people with Parkinson’s disease and their carers. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2006, 12, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macht, M.; Gerlich, C.; Ellgring, H.; Schradi, M.; Rusiñol, À.B.; Crespo, M.; Prats, A.; Viemerö, V.; Lankinen, A.; Bitti, P.E.R. Patient education in Parkinson’s disease: Formative evaluation of a standardized programme in seven European countries. Patient Educ. Couns. 2007, 65, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiihonen, S.; Lankinen, A.; Viemerö, V. An evaluation of a cognitive-behavioral patient education program for persons with Parkinson’s disease in Finland. Nord. Psychol. 2008, 60, 316–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A’campo, L.; Wekking, E.; Spliethoff-Kamminga, N.; le Cessie, S.; Roos, R. The benefits of a standardized patient education program for patients with Parkinson’s disease and their caregivers. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2010, 16, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, I.B.; Cleary, P.D. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life: A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA 1995, 273, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, D.; Liddy, C. Self-management support programs for persons with Parkinson’s disease: An integrative review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2017, 100, 1787–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandler, S.K.; Robins, J.L.; Kinser, P.A. Nonpharmacologic interventions for the self-management of anxiety in Parkinson’s disease: A comprehensive review. Behav. Neurol. 2019, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Owen, C.L.; Ibrahim, K.; Dennison, L.; Roberts, H.C. Falls self-management interventions for people with Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. J. Parkinson’s Dis. 2019, 9, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hulbert, S.M.; Goodwin, V.A. ‘Mind the gap’—A scoping review of long term, physical, self-management in Parkinson’s. Physiotherapy 2020, 107, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, E.R.; Bedekar, M.; Tickle-Degnen, L. Systematic review of the effectiveness of occupational therapy–related interventions for people with Parkinson’s disease. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2014, 68, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- A’campo, L.; Ibrahim, K.; Dennison, L.; Roberts, H.C. Caregiver education in Parkinson’s disease: Formative evaluation of a standardized program in seven European countries. Qual. Life Res. 2010, 19, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carlborg, C. Pilot testing of the Swedish national Parkinson school—“Meeting others equally important as the knowledge itself”. Parkinsonjournalen 2013, 4, 42–43. [Google Scholar]

- Carlborg, C. E new Swedish national Parkinson School can make life simpler and more enjoyable. Parkinsonjournalen 2013, 3, 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Kalia, L.V.; Lang, A.E. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 2015, 386, 896–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, R.; Klucken, J.; Weiss, D.; Tönges, L.; Kolber, P.; Unterecker, S.; Lorrain, M.; Baas, H.; Müller, T.; Riederer, P. Classification of advanced stages of Parkinson’s disease: Translation into stratified treatments. J. Neural Transm. 2017, 124, 1015–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodenheimer, T.; Wagner, E.H.; Grumbach, K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA 2002, 288, 1775–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodenheimer, T.; Wagner, E.H.; Grumbach, K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness: The chronic care model, Part 2. JAMA 2002, 288, 1909–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasano, A.; Fung, V.S.; Lopiano, L.; Elibol, B.; Smolentseva, I.G.; Seppi, K.; Takáts, A.; Onuk, K.; Parra, J.C.; Bergmann, L. Characterizing advanced Parkinson’s disease: OBSERVE-PD observational study results of 2615 patients. BMC Neurol. 2019, 19, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Knipe, M.D.W.; Wickremaratchi, M.M.; Wyatt-Haines, E.; Morris, H.R.; Ben-Shlomo, Y. Quality of life in young—Compared with late—Onset Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2011, 26, 2011–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lau, L.M.; Schipper, C.M.; Hofman, A.; Koudstaal, P.J.; Breteler, M.M. Prognosis of Parkinson disease: Risk of dementia and mortality: The Rotterdam study. Arch. Neurol. 2005, 62, 1265–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barak, A.; Hen, L.; Boniel-Nissim, M.; Shapira, N.A. A comprehensive review and a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of internet-based psychotherapeutic interventions. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2008, 26, 109–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Freeman, W.; Lightsey, R. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Häder, M. Delphi-Befragungen: Ein Arbeitsbuch; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, L.; Cummings, E.; Duff, J.; Walker, K. Partnering in digital health design: Engaging the multidisciplinary team in a needs analysis. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2018, 252, 176–181. [Google Scholar]

- Küffner, R.; Musekamp, G.; Reusch, A. Patientenschulung aus dem Blickwinkel der Entwickler. Arthritis Rheuma 2017, 37, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzenverband, G. Gemeinsame Empfehlungen zur Förderung und Durchführung von Patientenschulungen auf der Grundlage von § 43 Abs. 1 Nr. 2 SGB V vom 2. Dezember 2013 in der Fassung vom 08.02.2017; GKV Spitzenverband: Berlin, Germany, 2017; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Marburger, H. SGB V-Gesetzliche Krankenversicherung: Vorschriften und Verordnungen; Mit Praxisorientierter Einführung; Walhalla Fachverlag: Regensburg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Küffner, R.; Reusch, A. Schulungen Patientenorientiert Gestalten: Ein Handbuch des Zentrums Patientenschulung; Dgvt-Verlag: Tübingen, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mansoor, K.; Khuwaja, H.M.A. The Effectiveness of a chronic disease self-management program for elderly people: A systematic review. Elder. Health J. 2020, 6, 50–62. [Google Scholar]

- Buetow, S.A.; Martínez-Martín, P.; Hirsch, M.A.; Okun, M.S. Beyond patient-centered care: Person-centered care for Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinson’s Dis. 2016, 2, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

| Author, Date, Country | Program | Study Goals | Study Design/ Population | Intervention Content | Intervention Format | Measurement Instruments (BL/OTH (baseline, others (e.g., possible confounder)), PO (primary outcome), SO (secondary outcome), O (outcome not defined) Evaluation Timepoints | Outcome, Evidence Level (AACPDM) | ||

| Information Provision | Behavioral Modification | Physical Exercises | |||||||

| A’Campo et al., 2009, Netherlands | EduPark/PEEP Patient Education Program for Parkinson’s disease | (1) evaluation of effectiveness of PEPP | RCT, monocenter pre/post-test design additional formative evaluation intervention group PwPD (n = 35) CG (n = 26) control group PwPD (n = 29) CG (n = 20) comments: sample size based on feasibility | health promotion, stress management, management of anxiety/depression, role of unrealistic, unhelpful cognitions, ways of communication | based on behavioral cognitive therapy, importance of taking active/central role in health care system, self-monitoring techniques (using a diary for fluctuation of symptoms), social competence and support | body awareness (breathing, muscular tensions), relaxation exercises | intervention group 8 wk PEEP

control group

| quantitative

descriptive

evaluation timepoints t0 = baseline, 2 wk before PEEP, t1 = before and after each session, t2 = 9 wk after beginning of PEEP | baseline ↓↑ differences between groups ↓ MMSE score (intervention group) PT ↑ mood scale ↓↑ effects in patient scores (↓) PDQ-SI in intervention group CG ↓ BELA-A-k total ↓ BELA-A-k subscores: “achievement capability”, “emotional functioning”, “social functioning” descriptive

evidence level I |

| A’Campo et al., 2012, Netherlands | (1) secondary analysis of RCT for potential effect modifiers (A’Campo et al., 2009) | linear regression analyses

evidence level I | |||||||

| A’Campo et al., 2011 Netherlands | EduPark/PEEP Patient Education Program for Parkinson’s disease | (1) evaluation for effectiveness of PEEP in daily clinical practice without controlled academic conditions (2) comparison with previous RCT (A’Campo et al., 2009) (3) assessment of effectiveness at 6-mth-follow-up | non-randomized controlled design (historical control group), pre-test/post-test design, additional formative evaluation intervention group PwPD (n = 55) CG (n = 50) control group PwPD (n = 35) CG (n = 26) comments: clinical practice groups compared with RCT groups (A’Campo et al., 2009) | health promotion, stress management, management of anxiety/depression, role of unrealistic, unhelpful cognitions, ways of communication | based on behavioral cognitive therapy, importance of taking active/central role in health care system, self-monitoring techniques (using a diary for fluctuation of symptoms), social competence and support | body awareness (breathing, muscular tensions), relaxation exercises | intervention group 8 wk PEEP

historical control group

| quantitative

descriptive

evaluation timepoints t0 = baseline, t1 = before and after each session, t2 = 9 wks after beginning of PEEP, t3 = 6 mth follow-up | baseline ↑ PDQ-39-SI (intervention group) drop-outs ↑ PDQ-39-SI ↓ BELA-A-k (subscale: “bothered by”) short term effects (t2) ↑ mood scale (PT, CG) ↓↑ PT and CG ↓↑ intervention and control group ↓ BELA-A-k ↓ PDQ-39-SI descriptive

effects 6-mth-follow-up (t3) ↓↑ baseline and follow-up (PT, CG) descriptive

evidence level IV |

| Chlond et al., 2016 Germany | (1) re-evaluate the effectiveness of PEEP among German PwPD (2) assessment of sustainability of effect (3) define the time when a booster session is needed to maintain long-term efficacy | RCT, multicenter pre-test/post-test design intervention group PwPD (n = 39) control group PwPD (n = 34) no CG | intervention group 8 wk PEEP

control group

|

evaluation timepoints t0 = baseline, t1 = right after PEEP, t2 = 3 mth follow-up | baseline ↓↑ differences between groups after intervention and follow-up (t1,2) ↑ FKV-LIS-SE subscale (active problem-oriented coping) ↓↑ EQ-5D, BELA-P-k, SOC-29, GSE ↓ PDQ-39-SI ↓ PDQ-39 subscales (mobility, stigma, social support, bodily discomfort) after intervention (t1) (↑) EQ-5D VAS among intervention group, returned to baseline at follow-up evidence level II | ||||

| Macht et al., 2007 Germany, Estonia, Finland, Italy, Netherlands, Spain, UK | EduPark/PEEP Patient Education Program for Parkinson’s disease | (1) patient-related formative evaluation of usefulness, comprehensibility and feasibility (2) describing measures applicable for a formative evaluation with sample of 7 countries | single group design, multicenter, pre/post-test design, formative evaluation PwPD (n = 150) no CG | health promotion, stress management, management of anxiety/depression, role of unrealistic, unhelpful cognitions, ways of communication | based on behavioral cognitive therapy, importance of taking active/central role in health care system, self-monitoring techniques (using a diary for fluctuation of symptoms), social competence and support | body awareness (breathing, muscular tensions), relaxation exercises | 8 wk PEEP

| quantitative (PO not defined)

evaluation timepoints t0 = baseline, t1 = before/after each session, t2 = after 10 wk | baseline ↓↑ homogenous patient characteristics across countries post intervention effects (after each session) ↑ mood scale ↓↑ PDQ-39, SDS ↓ BELA-P-k dDescriptive *

evidence level IV |

| Simons et al., 2006 UK | (1) description program elements (2) formative evaluation with sample of British participants (3) suggestion of recommendations for future implementation | single group design, pre/post-test design, additional formative evaluation PwPD (n = 22) CG (n = 14) | quantitative (PO not defined)

descriptive

evaluation timepoints t0 = baseline, t1 = before/after each session, t2 = after 10 wk | post intervention effects (after each sessions) ↑ mood scale (except of 2 sessions) (PT, CG) ↓↑ PDQ-39, BELA-P (PT) ↓↑ EuroQol-5D, BELA-A (CG) (↓) subscales BELA-P (PT) dDescriptive *

evidence level IV | |||||

| Tiihonen et al., 2008 Finland | EduPark/PEEP Patient Education Program for Parkinson’s disease | (1) evaluation of effectiveness and applicability of PEEP in Finland | non-randomized controlled design pre/post-test design 2 centers intervention group PwPD (n = 29) HandY = 1–3 location: Turku control group PwPD (n = 23) HandY = 1–3 location: Helsinki no CG | health promotion, stress management, management of anxiety/depression, role of unrealistic, unhelpful cognitions, ways of communication | based on behavioral cognitive therapy, importance of taking active/central role in health care system, self-monitoring techniques (using a diary for fluctuation of symptoms), social competence and support | body awareness (breathing, muscular tensions), relaxation exercises | intervention group 8 wk PEEP

control group

| quantitative (PO not defined)

evaluation timepoints t0 = baseline, t1 = before and after each session, t2 = after 10 wks | baseline ↑ longer disease duration in control group post intervention effects (after each session) ↑ mood scale ↓↑ SDS without covariate adjustment: ↓↑ ADL scale ↓↑ BELA-P-k ↓↑ PDQ-39-SI (intervention group) ↑ PDQ-39-SI (control group) with covariate adjustment (years since diagnosis): ↓ PDQ-39 subscale (“Social support”) evidence level III |

| Tickle-Degnen et al., 2010 USA | self-management rehabilitation | (1) determine if self-management rehabilitation promoted HRQOL beyond best medical therapy (2) does more intense individualized rehabilitation increase effectiveness (3) persistence of outcomes at 2- and 6-months follow-up (4) Are rehabilitation-targeted domains (mobility, communication, activities of daily living) more responsive to intervention than non-targeted areas (emotions, stigma, social support, cognitive ability)? | RCT, monocenter intervention group 18 hrs rehabilitation PwPD (n = 37), HandY = 2–3 27 hrs rehabilitation PwPD (n = 39), HandY = 2–3 control group 0 hrs rehabilitation PwPD (n = 41), HandY = 2–3 no CG comments: power >0.80 (difference between rehabilitation and no rehabilitation) | no PD-specific content | assessing problems in personally valued domains of mobility, communication and daily life activities, observe behavior, identify strengths and problems in mobility, communication and activities of daily living, goal setting and implementation of action plans | physical and speech exercises, functional training | intervention group 6 wks of self-management rehabilitation

control group

|

evaluation timepoints t0 = baseline, t1 = post intervention, 6 wks, t2 = 2-month-follow-up, t3 = 6-month-follow-up | baseline ↓↑ differences between groups ↑ PDQ-39 social support (0 hrs rehabilitation) comparison rehabilitation vs. no rehabilitation ↓ PDQ-39-SI (reduction of problems) ↓ PDQ-39 subscales (communication, mobility, activities of daily living) ↓strongest effect PDQ-39 subscale communication (2-month follow-up) ↓ strongest effect PDQ-39 subscale mobility (6-month follow-up) ↓↑ no differences in PDQ-39 between 18 h and 27 h intensities evidence level I |

| Guo et al., 2009 China | personal rehabilitation program | (1) development of a program with group education and personal rehabilitation focusing on HR-QOL improvement (2) empower people with PD to deal with disease-related challenges | RCT, single-blind, pre/post-test design, quasi-experimental, monocenter intervention group PwPD (n = 23), HandY = 1–3 control group PwPD (n = 21), HandY = 1–3 no CG | specific nutrition, antidepressant and anxiolytic medications, psychotherapy | management of daily disease-impacted problems | physical and tailored occupational therapy (e.g., balance training, active music therapy), practical exercise at home | intervention group 8 wks personal rehabilitation program

control group standard care, one session after end of observation period |

evaluation timepoints t0 = baseline, t1 = after 4 wks, t2 = after intervention (8 wks) | baseline ↓↑ differences between groups after 4 wks ↓ PDQ-39 subscale bodily discomfort after 8 wks ↑ PMS ↓↑ SEADL ↓↑ SDS ↓ PDQ-39-SI ↓ UPDRS part II and III evidence level II |

| Sajatovic et al., 2017 USA | EXCEED (exercise therapy for PD + CDSM group program) | (1) compare an individual versus group exercise plus CDSM program (2) acceptance and adherence of these programs (3) alteration of depression and factors of neural health and inflammation after these interventions | prospective RCT, monocenter additional formative evaluation EXCEED intervention PwPD + comorbid depression (n = 15), HandY = 1–3 MADRS ≥ 14 SGE intervention PwPD + comorbid depression (n = 15), HandY = 1–3 MADRS ≥ 14 no CG comments: power >0.80 (MARDS) | CDSM information, PD-specific content (not further described) | based on self-management approach, problem identification and goal setting | fast-paced, low-resistance cycling (20 min), strength training (20 min), progressive sequence of resistance bands | 12 wks EXCEED

| quantitative (O defined as exploratory outcome))

descriptive

evaluation timepoints: t0 = baseline, t1 = after 12 wks, t2 = after 24 wks | baseline (↑) longer duration, higher doses, more extensive medical comorbidity (EXCEED) ↓↑ differences between the groups ↓ education, L-Dopa-dosage (SGE) combined group effects ↑ SCOPA-sleep (24 wks) ↑ MoCA (24 wks) ↑ BDNF (12 wks, 24 wks) ↓↑ Apathy scale, Covi Anxiety Scale, GSE, MDS-UPDRS-III ↓ MADRS (12 wks, 24 wks) descriptive *

evidence level II |

| SGE (self-guided CDSM program + exercise) | 12 wks SGE

| ||||||||

| Hellqvist et al., 2020 Sweden | NPS (National Parkinson School) | (1) outcomes of the NPS from the perspective of the participants using self- reported questionnaires | case-control study, quasi-experimental clinical practice, monocenter, additional formative evaluation intervention group PwPD (n = 70) CG (n = 41) control group PwPD (n = 62) CG (n = 34) comments: age and gender matched control group, power >0.80 (PDQ-8), twice sample size | need of disease related knowledge to understand how it affect the daily life, stress management, communication, anxiety and depression, self-monitoring, enriching activities, future life with PD | self-management and self-monitoring as central concepts, knowledge and tools to enhance ability to live and handle life with disease, awareness about thoughts and reactions, replace negative thoughts with constructive thoughts helps manage difficulties | relaxation exercises (15 min, end of a session) | intervention group 7 wk NPS

control group standard care |

evaluation timepoints: t0 = baseline, t1 = after 7 wk | baseline ↑ male participants (intervention group) ↓↑ difference between groups PT (intervention group) ↑ EuroQol-5D ↑ heiQ subscales (“constructive attitudes and approaches”, “skill and technique acquisition”) ↓ PDQ-8 PT (control group) ↓ LitSat-11 subscales (“satisfaction with life as a whole”, “leisure”, “contacts”) CG (↑) improvement of all scores after program ↓↑ difference between groups ↓ LiSat-11 subscale (“satisfaction with life as a whole”) heiQ ↑ relevant content, understanding of PD (↑) CG find NPS more helpful than PT in terms of goal setting self-reported confounding factors * (health problems, deaths in family, birth grandchildren) evidence level III |

| Lindskov et al., 2007 Sweden | multi-disciplinary group educational program with caregiver | (1) evaluate patient-reported health outcomes of a multi-disciplinary group educational program as part of routine clinical practice | naturalistic non-randomized controlled trial, monocenter waiting list intervention group PwPD (n = 49) control group PwPD (n = 48) with CG comments: power > 0.80 (standard error, SF-12) | general information (e.g., symptoms, disease progression), medical and surgical treatment, nutrition, oral hygiene, availability of funds, applying for funds, social support | managing day-to-day disease-related problems, focusing on possibilities rather than limitations, coping strategies | relaxation, speech and movement exercises | intervention group 6 wk multidisciplinary group educational program

control group delayed intervention after follow-up |

evaluation timepoints: t0 = baseline, t1 = after 10 wk | baseline ↓↑ difference between groups post intervention ↑ L-Dopa-dose (control group) ↓↑ SF-12 evidence level III |

| Lyons et al., 2020 USA | Strive to thrive: Self-Management for Parkinson’s Disease | (1) exploration of health benefits, self-management behaviors, illness communication for couples participating together in an existing community-based self-management workshop for PD | case-control study, quasi-experimental’, multicenter, waiting-list design intervention group PwPD + CG (couples, n = 19) control group PwPD + CG (couples, n = 20) | PD-specific content not further described, depression, sleep problems | self-management skills like monitoring, taking action, problem-solving, decision-making and evaluating results | exercises (not further described), relaxation techniques | intervention group 7 wk Strive to Thrive

control group wait list/delayed intervention |

evaluation timepoints: t0 = baseline, t1 = after 7 wk | baseline ↓↑ differences between groups ↓ aerobic activity, physical health (intervention group (PT)) PT (↑) aerobic activity (↑) mental relaxation (↑) self-management behaviors (↓) physical health (↓) engage in less protective buffering (↓) self-efficacy to manage PD CG ↑ improvement in engagement in mental relaxation techniques (↑) care strain (↑) engagement in strength-based activities (↑) self-efficacy to support partners in managing PD ↓↑ physical health ↓↑ aerobic activity (↑) self-management behaviors (↓) depressive symptoms (↓) engage in less protective buffering evidence level III |

| Gruber et al., 2008 Canada | EMP (The Early Management Program) | differences between 2 locations: (1) program evaluation (2) participants characteristics (3) attendance and non-completion rates (4) immediate benefits in terms of self-reported and physical outcomes | pre/post-test design, summative evaluation, 2 centers study Baycrest group PwPD (n = 40) HandY = 1–2 < 3 y disease duration location: Toronto CMID group PwPD (n = 52) HandY = 1–2 < 3 y disease duration location: Markham no CG | medication, pain, sleep, being an informed healthcare consumer, relationships (loving and caring), mind, emotions and behavior, participation in aerobic activities | programs based on self-management approach, aim to optimize ability to live well with PD, personal goal setting, coping with change and PD | Axial Mobility Program: exercises for flexibility, strength, posture, balance, relaxation techniques, walking, speech and swallowing | 8 wk EMP

| (PO not defined)

evaluation timepoints: t0 = 2 wks prior to beginning of EMP, t1 = after 8 wk (last session) | baseline ↑ age (CMID) ↑ month since diagnosis (CMID) ↑ UPDRS part I (CMID) post intervention ↑ CISM subscales (stretching, cognitive symptom management, mental stress management communication with physician) ↑ FAR (only Baycrest) ↑ FR ↑ timed functional movements, walking speed (↑) CISM aerobic subscale evidence level IV |

| Horne et al., 2019 Australia | Parkinson’s disease Wellbeing Program | (1) short-term improvements in psychosocial and physical parameters and sustainability at 12-mth follow-up (2) influence of older patient age, lower MMSE, higher HandY stage and disease duration on baseline parameters and physical improvement at 12 months (3) association of baseline patient characteristics and history of falls (4) relationship between baseline characteristics, exercises, 12-mth balance and psychosocial parameters | prospective observational study, single center PwPD (n = 135), HandY 1–3 no CG | importance of exercise, nutrition and medication, communication, speech and swallowing, sleep and fatigue, falls, freezing and posture, stress management and independent living | motivation to exercise daily, not explicit mentioned | dual tasking, extension, rotation, reaching, stepping, symmetrical gait, cardiovascular warm-up, stretching | 5 wk Wellbeing Program

| (PO not defined)

physical measures

evaluation timepoints: t0 = baseline, t1 = after intervention (6 wk), t2 = 12-month-follow-up (17 wk) | after 6 wks ↑ physical measures (2 MW, STS, TUG, gait velocity and BBS) ↑ DASS-21 ↓ PDQ-39 ↓ PFS-16 after 12 mths ↑ physical measures (2 MW, STS, TUG, gait velocity and BBS) ↓↑ DASS-21 ↓↑ PDQ-39 ↓↑ PFS-16 regression analysis

evidence level IV |

| Sunvisson et al., 2001 Sweden | Multi-disciplinary group educational program | (1) Evaluation of a training program for PwPD (2) influence on psychosocial situation, ability to handle daily life activities and mobility pattern | single group design, monocenter pre/post-test design PwPD (n = 45) HandY ≤ 4 no CG | physical/psychological symptoms, dialectical liaison between body and mind, medical treatments and side-effects, influences from physical surroundings and social networks | based on structure of connection model (interaction between person and environment), manage sickness-related difficulties in daily life by exploring limitations and possibilities, how to obtain and maintain good self-care | coordination, balance, body rhythm, stretching, relaxation and body language, practical advice: rise from chair, turn around in and get out of bed | 5 wk multidisciplinary group education program

|

evaluation timepoints: t0 = baseline, t1 = after intervention (5 wk), t2 = 3-month-follow-up (17 wks) | ↑ PLM subscales movement time, simultaneous index/level of integrated movements ↑ improvement SIP and SIP subscales psychosocial dysfunction, sleep and rest (baseline + 17 wk) ↓↑ UPDRS subscale motor examination ↓ UPDRS subscale ADL (baseline+ 5 wks, 5 wks + 17 wks) evidence level IV |

| Chaplin et al., 2012 UK | Hertfordshire Neurological Services Self-Management Program | (1) description of program development (2) discussion of implications for service providers and future research | program development and concept process evaluation persons with long-term neurological conditions (n = 60) CG na | symptoms, medication, psychological aspects, communication, nutrition, advice for speech and swallowing difficulties, strategies or enhancing function and mobility-circuits | based on main theoretical approaches to self-management (social cognitive theory and self-regulation model), personal health plans, self-management concept and support tools, strategies for daily life and coping | exercise examples and physiotherapy | condition-specific self-management groups at Hertfordshire neurological service

|

evaluation timepoint: t1 = after intervention |

evidence level V |

| van Nimwegen et al., 2010/2013 Netherlands # | ParkFit Program | (1) development of a multifaceted intervention to promote physical activity in sedentary PwPD (2) investigation whether this program affords increased physical activity levels that persist for two years (3) search for possible health benefits and risks of increased physical activity | RCT, multicentre intervention group PwPD (n = 299) HandY ≤ 3 control group PwPD (n = 287) HandY ≤ 3 no CG comments: 32 participating hospitals, Power 0.80 | general information about PD benefits of physical activity behavioural change strategies like identifying and overcoming any perceived barriers to engage in physical activity | combination of techniques based on models of behavioural change identify individual beliefs goal setting, recruiting social support | physical therapy | intervention group 2 y ParkFit

|

evaluation timepoints: t0 = baseline, t1 = per week, t2 = monthly, t3 = after 6 mths, t4 = after 12 mths, t5 = after 18 mths, t6 = after 24 mths | 6 to 24 mth (change) ↑ level of physical activity ↓↑ LAPAQ ↓↑ PDQ-39 ↓↑ number of falls (↓) 6 MWT evidence level I |

| ParkSafe Program | general information about PD aims and benefits of physical therapy importance of safety on daily activities | not included | interventions from physical therapy guidelines for PD to move more safely improving quality of transfers | control group 2 y ParkSafe

| |||||

| Author, Date, Country | Program | Study Goals | Study Design/ Population | Intervention Content | Intervention Format | Measurement Instruments, Evaluation Timepoints | Outcome | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information Provision | Behavioral Modification | Physical Exercises | |||||||

| Hellqvist et al., 2018 Sweden | NPS (National Parkinson School) | (1) identify experiences valuable for managing daily life after participation in the program (2) explore applicability of self- and family-management framework by Grey | qualitative explorative design with two-step-analyses, multicenter PwPD (n = 25) CG (n = 17) | need of disease related knowledge to understand how it affect the daily life, stress management, communication, anxiety and depression, self-monitoring, enriching activities, future life with PD | self-management and self-monitoring as central concepts, knowledge and tools to enhance ability to live and handle life with disease, awareness about thoughts and reactions, replace negative thoughts with constructive thoughts helps manage difficulties | relaxation exercises (15 min, end of a session) | 7 wk NPS

|

evaluation timepoints: t0 = onset of NPS t1 = wk 7, last intervention session | major themes of being an NPS participant

|

| Hellqvist et al., 2020 Sweden | (1) whether PwPD and CG implemented the strategies of self-monitoring included in the NPS and use them in clinical encounters with health care professionals | qualitative inductive study with two-part method: observation and follow-up interviews, monocenter PwPD (n = 10) CG (n = 3) |

evaluation timepoints: t1 = 3 to 5 mth after participation on NPS intervention |

| |||||

| Mulligan et al., 2011 New Zealand | Living Well with Parkinson’s Disease | (1) evaluate an innovative self-management program from the users’ perspectives | qualitative evaluation study, individual interviews with participants, monocenter PwPD (n = 8) CG (n = 3) | knowledge about PD current research, medication, nutrition, emotional and psychological aspects | enable participants to effectively self-manage life, identify level of self-efficacy | physical exercises (not further described) | 6 wk Living Well with PD

|

evaluation timepoint: t1 = 2 to 7 wk. after participation on intervention |

core categories

|

| Author, Date, Country | Program | Study Goals | Study Design Population | Intervention Content | Intervention Format | Measurement Instruments (BL/OTH (baseline, others (e.g., confounder)), PO (primary outcome), SO (secondary outcome), O (outcome not defined as PO or SO))) Evaluation Timepoints | Intended Outcome | ||

| Information Provision | Behavioral Modification | Physical Exercises | |||||||

| Siegert et al., 2019 Germany | ParkPro- Train | (1) user-centered development and implementation of an individualized tablet-based training program (2) transfer of the physically activating exercises learned in the MKP and other physical activities into everyday life (3) improvement in QOL, social participation and delayed progression of impairment through regular implementation of the program | mixed methods (1) monocenter, quasi-randomized longitudinal study, RCT (2) interviews and focus groups (3) formative evaluation (tablet-based program, administration panel) (4) evaluation of the training program implementation intervention group PwPD (n = 133) control group PwPD (n = 133) no CG comments: calculation based on PDQ-8 (power >0.80) | knowledge, preparing for everyday life at home | based on HAPA-model (intent formation and implementation of health behavior), based on 5-A-model (increase self-management skills and support behavioral change), adaption of physical exercises (learning method of behavior shaping), considering of personal barriers and strategies to overcome those | different exercises promoting endurance, strength, balance and activities like Nordic walking, Tai Chi or dancing | intervention group

control group

| quantitative

qualitative

evaluation timepoints: t0 = baseline/right before MKP, t1 = 3 wk. follow-up/right after MKP, t2 = 9 wk after MKP, t3 = 9 mth after t1 | ↑ physical activity ↑ improvement of motor and non-motor impairments ↑ QOL ↑ long time effects of MKP ↓ individualized, time-consuming care by a therapist ↓ costs for conventional occupational/physiotherapy prescriptions descriptive

|

| Navarta-Sánchez et al., 2008 Spain | ReNACE | (1) improvement of QOL of PwPD and their family carers by means of a multidisciplinary psychoeducational intervention focusing on fostering coping strategies and their psychosocial adjustment to PD (2) evaluate the perceptions, opinions and satisfaction of the patients and family carers and explore the reflections of the social and healthcare providers involved in this intervention | mixed methods part of ReNACE research program (1) quasi-experimental study with control group (2) focus groups PwPD (n = 104) CG (n = 106) comments: calculation based on PDQ-39 and SQLC | ReNACE getting to know PD, healthy life habits, resources, management of stress and complicated situations, look for information, normalize the situation and partake in activities, positive self-esteem, empathy and patience | ReNACE adapting and coping with PD and stressful situations, empowerment, awareness of participants cognitive and behavioral efforts | not contained in both interventions | intervention group 9 wk ReNACE

| quantitative

qualitative

evaluation timepoints: t0 = baseline, t1 = after intervention, t2 = 6 mth after t1 | ↑ psychosocial adjustment to PD ↑ QOL of PwPD and CG ↑ compliance with drug treatment and healthy lifestyles |

| GEP (general education program) | GEP general information on PD, healthy life habits, resources in the community | GEP not mentioned | control group 5 wk GEP

| ||||||

| King et al., 2015 USA | ABC-C (Agility Boot Camp-Cognition) | (1) improvement of mobility and/or cognition after partaking in the ABC-C program compared to a control intervention (2) prediction of cognition and postural, cognitive and brain posture/locomotor circuitry deficits for responsiveness to the cognitively challenging ABC-C program | cross-over RCT PwPD (n = 120) age 50–90 y no CG comments: power calculation based on Mini-BESTest | ABC-C not mentioned | ABC-C not included | ABC-C gait training, lunging, PWR! moves, agility, boxing, Thai Chi | intervention group 6 wk ABC-C

| quantitative:

evaluation timepoints: t0 = baseline, t1 = after 1st 6 wk intervention (before cross over), t2 = after 2nd 6 wk intervention | ↓ executive function deficits and reduced structural and/or functional connectivity of the locomotor circuitry predict poor responses to challenging balance rehabilitation |

| EPCD (education program for chronic disease) | EPCD finding information on PD, communicating effectively with health care providers, sleep, pain, fatigue, nutrition, medication, difficult emotions, stress, depression | EPCD not explicit mentioned, stress management and finding information | EPCD relaxation sessions, improving communication (verbal, voice tone, body language) | control group 6 wk EPCD

| |||||

| Gruber et al., 2008 Canada | SMandFPP (Safe Mobility and Falls Prevention Program) | (1) use feedback from participants to review and modify the program (2) assessment of adherence with HSEP (home support exercise program), fear of falling, improvement in fall risk factors, satisfaction with social participation | formative pilot evaluation (no results during publication), concept for outcome assessment PwPD (n not calculated) HandY = 3–4 no CG | prevention of falls, maximizing safe mobility through medications, exercise strategies, adaptive equipment | programs based on self-management approach, aim to optimize ability to live well with PD, goal setting and action plans | bed mobility transfers walking falls recovery transfers | 7 wk SMandFPP

| pilot evaluation

quantitative (PO not defined)

evaluation timepoints: t0 = baseline, 2 wk prior to beginning, t1 = at session 7, t2 = at session 8, after 6 wk | ↑ improvement falls risk factors (BBS, TUG, ABC) ↑ satisfaction RNLI ↓ fear of falling (ABC) ↓ number of self-reported falls |

| General Program Information | Formal Description | Proof of Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tennigkeit, J.; Feige, T.; Haak, M.; Hellqvist, C.; Seven, Ü.S.; Kalbe, E.; Schwarz, J.; Warnecke, T.; Tönges, L.; Eggers, C.; et al. Structured Care and Self-Management Education for Persons with Parkinson’s Disease: Why the First Does Not Go without the Second—Systematic Review, Experiences and Implementation Concepts from Sweden and Germany. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2787. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9092787

Tennigkeit J, Feige T, Haak M, Hellqvist C, Seven ÜS, Kalbe E, Schwarz J, Warnecke T, Tönges L, Eggers C, et al. Structured Care and Self-Management Education for Persons with Parkinson’s Disease: Why the First Does Not Go without the Second—Systematic Review, Experiences and Implementation Concepts from Sweden and Germany. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020; 9(9):2787. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9092787

Chicago/Turabian StyleTennigkeit, Jenny, Tim Feige, Maria Haak, Carina Hellqvist, Ümran S. Seven, Elke Kalbe, Jaqueline Schwarz, Tobias Warnecke, Lars Tönges, Carsten Eggers, and et al. 2020. "Structured Care and Self-Management Education for Persons with Parkinson’s Disease: Why the First Does Not Go without the Second—Systematic Review, Experiences and Implementation Concepts from Sweden and Germany" Journal of Clinical Medicine 9, no. 9: 2787. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9092787

APA StyleTennigkeit, J., Feige, T., Haak, M., Hellqvist, C., Seven, Ü. S., Kalbe, E., Schwarz, J., Warnecke, T., Tönges, L., Eggers, C., & Loewenbrück, K. F. (2020). Structured Care and Self-Management Education for Persons with Parkinson’s Disease: Why the First Does Not Go without the Second—Systematic Review, Experiences and Implementation Concepts from Sweden and Germany. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(9), 2787. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9092787